Brussels

Brussels (Dutch: Brussel, pronounced [ˈbrʏsəl] ,French: Bruxelles, pronounced [bʁysɛl] ; German: Brüssel, pronounced [ˈbʀʏsəl]), officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region[1][2] (French: , Dutch: ), is the capital of Belgium and hosts the headquarters of the European Union (EU). It is also the largest urban area in Belgium,[7][8] comprising 19 municipalities, including the municipality of the City of Brussels, which is the de jure capital of Belgium, in addition to the seat of the French Community of Belgium and of the Flemish Community.[9]

Brussels has grown from a 10th-century fortress town founded by a descendant of Charlemagne into a metropolis of more than one million inhabitants.[10] The metropolitan area has a population of over 1.8 million, making it the largest in Belgium.[11][12]

Since the end of the Second World War, Brussels has been a main center for international politics. Hosting principal EU institutions[13] as well as the headquarters of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the city has become the polyglot home of numerous international organisations, politicians, diplomats and civil servants.[14]

Although historically Dutch-speaking, Brussels became increasingly French-speaking over the 19th and 20th centuries. Today a majority of inhabitants are native French-speakers, and both languages have official status.[15] Linguistic tensions remain, and the language laws of the municipalities surrounding Brussels are an issue of considerable controversy in Belgium.

History

The most common theory for the toponymy of Brussels is that it derives from the Old Dutch Broeksel or other spelling variants, which means marsh (broek) and home (sel) or "home in the marsh".[16] The origin of the settlement that was to become Brussels lies in Saint Gaugericus' construction of a chapel on an island in the river Senne around 580.[17] Saint Vindicianus, the bishop of Cambrai made the first recorded reference to the place "Brosella" in 695[18] when it was still a hamlet. The official founding of Brussels is usually situated around 979, when Duke Charles of Lower Lotharingia transferred the relics of Saint Gudula from Moorsel to the Saint Gaugericus chapel. Charles would construct the first permanent fortification in the city, doing so on that same island.

Lambert I of Leuven, Count of Leuven gained the County of Brussels around 1000 by marrying Charles' daughter. Because of its location on the shores of the Senne on an important trade route between Bruges and Ghent, and Cologne, Brussels grew quite quickly; it became a commercial centre that rapidly extended towards the upper town (St. Michael and Gudula Cathedral, Coudenberg, Sablon/Zavel area...), where there was a smaller risk of floods. As it grew to a population of around 30,000, the surrounding marshes were drained to allow for further expansion. The Counts of Leuven became Dukes of Brabant at about this time (1183/1184). In the 13th century, the city got its first walls.[19]

After the construction of the first walls of Brussels, in the early 13th century, Brussels grew significantly. To let the city expand, a second set of walls was erected between 1356 and 1383. Today, traces of it can still be seen, mostly because the "small ring", a series of roadways in downtown Brussels bounding the historic city centre, follows its former course.

In the 15th century, by means of the wedding of heiress Margaret III of Flanders with Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, a new Duke of Brabant emerged from the House of Valois (namely Antoine, their son), with another line of descent from the Habsburgs (Maximilian of Austria, later Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, married Mary of Burgundy, who was born in Brussels). Brabant had lost its independence, but Brussels became the Princely Capital of the prosperous Low Countries, and flourished.

Charles V, heir of the Low Countries since 1506, though (as he was only 6 years old) governed by his aunt Margaret of Austria until 1515, was declared King of Spain, in 1516, in the Cathedral of Saint Gudule in Brussels. Upon the death of his grandfather, Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor in 1519, Charles became the new archduke of the Habsburg Empire and thus the Holy Roman Emperor of the Empire "on which the sun does not set". It was in the Palace complex at Coudenberg that Charles V abdicated in 1555. This impressive palace, famous all over Europe, had greatly expanded since it had first become the seat of the Dukes of Brabant, but it was destroyed by fire in 1731.

In 1695, King Louis XIV of France sent troops to bombard Brussels with artillery. Together with the resulting fire, it was the most destructive event in the entire history of Brussels. The Grand Place was destroyed, along with 4000 buildings, a third of those in the city. The reconstruction of the city centre, effected during subsequent years, profoundly changed the appearance of the city and left numerous traces still visible today. The city was captured by France in 1746 during the War of the Austrian Succession but was handed back to Austria three years later.

In 1830, the Belgian revolution took place in Brussels after a performance of Auber's opera La Muette de Portici at the La Monnaie theatre. On 21 July 1831, Leopold I, the first King of the Belgians, ascended the throne, undertaking the destruction of the city walls and the construction of many buildings. Following independence, the city underwent many more changes. The Senne had become a serious health hazard, and from 1867 to 1871 its entire course through the urban area was completely covered over. This allowed urban renewal and the construction of modern buildings and boulevards characteristic of downtown Brussels today.

During the 20th century the city has hosted various fairs and conferences, including the fifth Solvay Conference in 1927 and two world fairs: the Brussels International Exposition of 1935 and the Expo '58. Brussels suffered damage from World War II, though it was minor compared to cities in Germany and the United Kingdom.

After the war, Brussels was modernized for better and for worse. The construction of the North–South connection linking the main railway stations in the city was completed in 1952, while the first Brussels premetro was finished in 1969, and the first line of the Brussels Metro was opened in 1976. Starting from the early 1960s, Brussels became the de facto capital of what would become the European Union, and many modern buildings were built. Unfortunately, development was allowed to proceed with little regard to the aesthetics of newer buildings, and many architectural gems were demolished to make way for newer buildings that often clashed with their surroundings, a process known as Brusselization.

The Brussels-Capital Region was formed on 18 June 1989 after a constitutional reform in 1970. The Brussels-Capital Region was made bilingual, and it is one of the three federal regions of Belgium, along with Flanders and Wallonia.[1][2]

Municipalities

The 19 municipalities (communes) of the Brussels-Capital Region are political subdivisions with individual responsibilities for the handling of local level duties, such as law enforcement and the upkeep of schools and roads within its borders.[20][21] Municipal administration is also conducted by a mayor, a council, and an executive.[21]

In 1831, Belgium was divided into 2,739 municipalities, including the 19 in the Brussels-Capital Region.[22] Unlike most of the municipalities in Belgium, the ones located in the Brussels-Capital Region were not merged with others during mergers occurring in 1964, 1970, and 1975.[22] However, several municipalities outside of the Brussels-Capital Region have been merged with the City of Brussels throughout its history including Laeken, Haren, and Neder-Over-Heembeek, which were merged into the City of Brussels in 1921.[23]

The largest and most populous of the municipalities is the City of Brussels, covering 32.6 square kilometres (12.6 sq mi) with 145,917 inhabitants. The least populous is Koekelberg with 18,541 inhabitants, while the smallest in area is Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, which is only 1.1 square kilometres (0.4 sq mi). Despite being the smallest municipality, Saint-Josse-ten-Noode has the highest population density of the 19 with 20,822 inhabitants per km2.

BPihIdE

Government

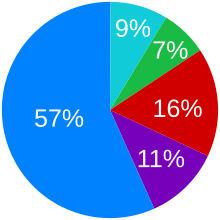

The Brussels-Capital Region is one of the three Regions of Belgium, while the French Community of Belgium and the Flemish Community do exercise, each for their part, their cultural competencies on the territory of the Region. French and Dutch are the official languages; most public services are bilingual (exceptions being education and a couple of others). The Capital Region is predominantly French-speaking—about 85–90%[24][25][26] of the population are French-speakers (including migrants and second language speakers), and about 10–15%[26][27] are native Dutch-speakers. In January 2006, of its registered inhabitants, 73.1% are Belgian nationals, 4.1% French nationals, 12.0% other EU nationals (usually expressing themselves in either French or English), 4.0% Moroccan nationals, and 6.8% other non-EU nationals.[28]

Institutions

Because of how the federalisation was handled in Belgium, but also because the municipalities in the region did not take part in the merger that affected municipalities in the rest of Belgium in the seventies, the public institutions in Brussels offer a bewildering complexity. The complexity is more apparent in the lawbooks than in the facts, since the members of the Brussels Parliament and Government also act in other capacities, for example, as members of the council of the Brussels agglomeration or the community commissions. One distinguishes:

Parliament

The region, with a regional parliament of 89 members (72 French-speaking, 17 Dutch-speaking, parties are organised on a linguistic basis), plus a regional government, consisting of an officially linguistically neutral, but in practice French-speaking minister-president, two French-speaking and two Dutch-speaking ministers, one Dutch-speaking secretary of state and two French-speaking secretaries of state. This parliament can enact ordinances (French: ordonnances, Dutch: ordonnanties), which have equal status as a national legislative act.

- The agglomeration, with a council and a board, with the same membership as the organs of the Brussels Region. This is a decentralised administrative public body, assuming competences that elsewhere in Belgium are exercised by municipalities or provinces (fire brigade, waste disposal). The by-laws enacted by it do not have the status of a legislative act.

- A bi-communitarian public authority, Common Community Commission (French: Commission communautaire commune, COCOM, Dutch: Gemeenschappelijke Gemeenschapscommissie, GGC), with a United Assembly (i.e. the members of the regional parliament) and a United Board (the ministers—not the secretaries of state—of the region, with the minister-president not having the right to vote). This Commission has two capacities: it is a decentralised administrative public body, responsible for implementing cultural policies of common interest. It can give subsidies and enact by-laws. In another capacity it can also enact ordinances, which have equal status as a national legislative act, in the field of the welfare competencies of the communities: in the Brussels-Capital Region, both the French Community and the Flemish Community can exercise competencies in the field of welfare, but only in regard to institutions that are unilingual (for example, a private French-speaking retirement home or the Dutch-speaking hospital of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel). The Common Community Commission is competent for policies aiming directly at private persons or at bilingual institutions (for example, the centra for social welfare of the 19 municipalities). Its ordinances have to be enacted with a majority in both linguistic groups. Failing such a majority, a new vote can be held, where a majority of at least one third in each linguistic group is sufficient.

- The Brussels Region is not a province, nor does it belong to one. Within the Region, 99% of the provincial competencies are assumed by the Brussels regional institutions. Remaining is only the governor of Brussels-Capital and some aides.

- 6 inter-municipal policing zones

- intercommunal societies created freely by the municipalities

Also the federal state, the French Community and the Flemish Community exercise competencies on the territory of the region. 19 of the 72 French-speaking members of the Brussels Parliament are also members of the Parliament of the French Community of Belgium, and until 2004 this was also the case for six Dutch-speaking members, who were at the same time members of the Flemish Parliament. Now, people voting for a Flemish party have to vote separately for 6 directly elected members of the Flemish Parliament.

Due to the multiple capacities of single members of parliament, there are parliamentarians who are at the same time members of the Brussels Parliament, members of the Assembly of the Common Community Commission, members of the Assembly of the French Community Commission, members of the Parliament of the French Community of Belgium and "community senators" in the Belgian Senate. At the moment, this is the case for Mr. François Roelants du Vivier (for the Mouvement Réformateur), Mrs. Amina Derbaki Sbaï (since June 2004 for the Parti Socialiste, but beforehand, since 2003, for the Mouvement Réformateur) and Mrs Sfia Bouarfa (since 2001 for the Parti Socialiste).

In Belgian politics

Despite what its name suggests, the Brussels-Capital Region is not the capital of Belgium in itself. Article 194 of the Belgian Constitution establishes that the capital of Belgium is the City of Brussels, a smaller municipality within the capital region that once was the city's core.[29]

However, although the City of Brussels is the official capital, the funds allotted by the federation and region for the representative role of the capital are divided among the 19 municipalities, and some national institutions are sited in the other 18 municipalities. Thus, while only the City of Brussels itself officially carries the title of capital of Belgium, in practice the entire capital region plays this role, and the national institutions of the Belgian state are spread loosely around the region.[citation needed]

Seat of the French Community and Flemish Community

The Brussels-Capital Region is one of the three federated regions of Belgium, alongside Wallonia and the Flemish Region. Geographically and linguistically, it is a bilingual enclave in the unilingual Flemish Region. Regions are one component of Belgium's institutions, the three communities being the other component: Brussels' inhabitants deal with either the French (speaking) Community or the Flemish Community for matters such as culture and education.[30]

Brussels is also the capital of both the French Community of Belgium (Communauté française de Belgique in French) and of Flanders (Vlaanderen); all Flemish capital institutions are established here: Flemish Parliament, Flemish Government and its administration.[31]

- 2 community-specific public authorities, French Community Commission (French: Commission communautaire française or COCOF) and the Flemish Community Commission (Dutch: Vlaamse Gemeenschapscommissie, VGC) for the Flemings in Brussels, with an assembly (i.e. the members of parliament of the linguistic group) and a board (the ministers and secretaries of state of the linguistic group). These commissions implement policies of the French Community and the Flemish Community in the Brussels-Capital Region.[30]

- The French Community Commission has also another capacity: some legislative competencies of the French Community have been devolved to the Walloon Region (for the French language area of Belgium) and to the French Community Commission (for the bilingual language area).[32] The Flemish Community, however, did the opposite; it merged the Flemish Region into the Flemish Community.[33] This is related to different conceptions in the two communities, one focusing more on the Communities and the other more on the Regions, causing an asymmetrical federalism. Because of this devolution, the French Community Commission can enact decrees, which are legislative acts.

In international politics

Brussels has since World War II become the administrative centre of many international organizations. Notably the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) have their main institutions in the city, along with many other international organisations such as the Western European Union, World Customs Organization and EUROCONTROL as well as international corporations. Brussels is third in the number of international conferences it hosts[34] also becoming one of the largest convention centres in the world.[35] The presence of the EU and the other international bodies has for example led to there being more ambassadors and journalists in Brussels than in Washington D.C.[36] International schools have also been established to serve this presence.[35] The "international community" in Brussels numbers at least 70,000 people.[37] In 2009, there were an estimated 286 lobbying consultancies known to work in Brussels.[38]

European Union

Brussels serves as capital of the European Union, hosting the major political institutions of the Union.[8] The EU has not declared a capital formally, though the Treaty of Amsterdam formally gives Brussels the seat of the European Commission (the executive/government branch) and the Council of the European Union (a legislative institution made up from leaders of member states).[39][40] It locates the formal seat of European Parliament in the French city of Strasbourg, where votes take place with the Council on the proposals made by the Commission. However meetings of political groups and committee groups are formally given to Brussels along with a set number of plenary sessions. Three quarters of Parliament now takes place at its Brussels hemicycle.[41] Between 2002 and 2004, the European Council also fixed its seat in the city.[42]

Brussels, along with Luxembourg and Strasbourg, began to host institutions in 1957, soon becoming the centre of activities as the Commission and Council based their activities in what has become the "European Quarter".[39] Early building in Brussels was sporadic and uncontrolled with little planning, the current major buildings are the Berlaymont building of the Commission, symbolic of the quarter as a whole, the Justus Lipsius building of the Council and the Espace Léopold of Parliament.[40] Today the presence has increased considerably with the Commission alone occupying 865,000 m2 within the "European Quarter" in the east of the city (a quarter of the total office space in Brussels[8]). The concentration and density has caused concern that the presence of the institutions has caused a "ghetto effect" in that part of the city.[43] However the presence has contributed significantly to the importance of Brussels as an international centre.[36]

Demographics

On 1 May 2008, the region had a population of 1,070,841 and an area of 161,382 km2 which gives the region a population density of 6,635 inhabitants per km2. People of Muslim background account for 25.5% of Brussels.[44]

| Regions of Belgium[44] (01/01/2005) | Total population | People of Muslim origin | % of Muslims |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 10,445,852 | 628,751 | 6.0% |

| Brussels-Capital Region | 1,006,749 | 256,220 | 25.5% |

| Wallonia | 3,395,942 | 136,596 | 4.0% |

| Flanders | 6,043,161 | 235,935 | 3.9% |

| Population by national origin, 1 March 1991[45] (last census ever organised in Belgium) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Belgians born in Belgium (to Belgian parents) | 607,446 | 63.7% |

| Belgians born abroad (to Belgian parents) including: Congo, Rwanda and Burundi (former Belgian overseas territories) |

21,028 8,116 |

2,2% (100%) 38.6% |

| Naturalised migrants (not born in Belgium, not to Belgian parents) including: France Morocco |

36,938 6,348 3,022 |

3.9% (100%) 17.2% 8.2% |

| Naturalised 1st and 2nd generations (born in Belgium, not to Belgian parents) including: France Morocco |

17,045 2,757 2,522 |

1.8% (100%) 16.2% 14.8% |

| Non-naturalised 1st and 2nd generations including: Morocco |

87,987 37,300 |

9.2% (100%) 42.4% |

| Old migrants (born abroad, foreign nationals, living in Belgium in 1986) including: Morocco Italy |

123,411 35,138 16,027 |

12.9% (100%) 28.5% 13% |

| Recent migrants (born abroad, foreign nationals, arrived in Belgium after 1986) including: France Morocco |

60,185 8,513 4,970 |

6.3% (100%) 14.1% 8.3% |

| Total Brussels-Capital Region | 954,040 | 100% |

At the last Belgian census in 1991, there were 63.7% inhabitants in Brussels-Capital Region who answered they were Belgian citizens, born as such in Belgium. However, there have been numerous individual or familial migrations towards Brussels since the end of the 18th century, including political refugees (Karl Marx, Victor Hugo, Pierre Joseph Proudhon, Léon Daudet for example,) from neighbouring or more distanced countries as well as labour migrants, former foreign students or expatriates, and many Belgian families in Brussels can claim at least one foreign grandparent. And even among the Belgians, many became Belgian only recently.

The original Dutch dialect of Brussels (Brussels) is a form of Brabantic (the variant of Dutch spoken in the ancient Duchy of Brabant) with a significant number of loanwords from French, and still survives among a minority of inhabitants called Brusseleers, many of them quite bi- and multilingual, or educated in French and not writing the Dutch language. Brussels and its suburbs evolved from a Dutch-dialect–speaking town to a mainly French-speaking town. The ethnic and national self-identification of the inhabitants is quite different along ethnic lines. For their French-speaking Bruxellois, it can vary from Belgian, Francophone Belgian, Bruxellois (like the Memelländer in interwar ethnic censuses in Memel), Walloon (for people who migrated from the Wallonia Region at an adult age); for Flemings living in Brussels it is mainly either Flemish or Brusselaar (Dutch for an inhabitant) and often both. For the Brusseleers, many simply consider themselves as belonging to Brussels. For the many rather recent immigrants from other countries, the identification also includes all the national origins: people tend to call themselves Moroccans or Turks rather than an American-style hyphenated version.

The two largest foreign groups come from two francophone countries: France and Morocco.[28] The first language of roughly half of the inhabitants is not an official one of the Capital Region.[46] Nevertheless, about three out of four residents are Belgian nationals.[47][48][49] In general the population of Brussels is younger and the gap between rich and poor is wider. Brussels also has a large concentration of Muslims, mostly of Turkish and Moroccan ancestry, and mainly French-speaking black Africans. Belgium does not collect statistics by ethnic background, so exact figures are unknown, but one estimate puts the number of Muslims in Brussels at 15%.[50]

Both immigration and Brussels' status as the capital of the EU made it a cosmopolitan world city. The migrant communities, as well as rapidly growing communities of EU-nationals from other EU-member states, speak many languages like French, Turkish, Arabic, Berber, Spanish, Catalan, Basque, Italian, Portuguese, Polish, German, and (increasingly) English. The degree of linguistic integration varies widely within each migrant group.

Among all major migrants groups from outside the EU, a majority of the permanent residents have acquired Belgian nationality.

Although historically (since the Counter-Reformation persecution and expulsion of Protestants by the Spanish in the 16th century) Roman Catholic, most people in Brussels are non-practising. About 10% of the population regularly attends church services. Among the religions, historically dominant Roman Catholicism prevailing mostly in a relaxed way, one finds large minorities of Muslims, atheists, agnosticists, and of the philosophical school of humanism, the latter mainly as laïcité-vrijzinnig (an approximate translation would be secularists or free thinkers) or practicing Humanism as a life stance—Brussels houses several key organisations for both kinds. Other (recognised) religions (Protestantism, Anglicanism, Orthodoxy and Judaism) are practised by much smaller groups in Brussels. Recognised religions and Laïcité enjoy public funding and school courses: every pupil in an official school from 6 years old to 18 must choose 2 hours per week of compulsory religion—or Laïcité—inspired morals.

Languages

Since the founding of the Kingdom of Belgium in 1830, Brussels has transformed from being almost entirely Dutch-speaking (Brabantian to be exact), to being a multilingual city with French (specifically Belgian French) as the majority language and lingua franca. This language shift, the Frenchification of Brussels, is rooted in the 18th century and accelerated after Belgium became independent and Brussels expanded past its original boundaries.[52][53]

Not only French-speaking immigration contributed to the Frenchification of Brussels; a more important cause was the language change over several generations from Dutch to French that was performed in Brussels by the Flemish people themselves. The main reason for this was the political, administrative and social pressure, partly based on the low social prestige of the Dutch language in Belgium at the time.[55] From 1880 on, more and more Dutch-speaking people became bilingual, resulting in a rise of monolingual French-speakers after 1910. Halfway through the 20th century the number of monolingual French-speakers carried the day over the mostly bilingual Flemish inhabitants.[56]

Only since the 1960s, after the fixation of the Belgian language border and the socio-economic development of Flanders was in full effect, could Dutch stem the tide of increasing French use.[57] Through immigration, a further number of formerly Dutch-speaking municipalities in surrounding Flanders became majority French-speaking in the second half of the 20th century.[58][59][60] This phenomenon is, together with the future of Brussels, one of the most controversial topics in all of Belgian politics.[61][62]

Given its Dutch-speaking origins and the role that Brussels plays as the capital city in a bilingual country, Flemish political parties demand that the entire Brussels-Capital Region be fully bilingual, including its subdivisions and public services. They also demand that the contested Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde arrondissement will be separated from the Brussels region. However, the French-speaking population regards the language border as artificial[63] and demands the extension of the bilingual region to at least all six municipalities with language facilities in the surroundings of Brussels.[64] Flemish politicians have strongly rejected these proposals.[65][66][67]

Culture

Architecture

The architecture in Brussels is diverse, and spans from the medieval constructions on the Grand Place to the postmodern buildings of the EU institutions.

Main attractions include the Grand Place, since 1988 a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with the Gothic town hall in the old centre, the St. Michael and Gudula Cathedral and the Laken Castle with its large greenhouses. Another famous landmark is the Royal Palace.

The Atomium is a symbolic 103-metre (338 ft) tall structure that was built for the 1958 World’s Fair. It consists of nine steel spheres connected by tubes, and forms a model of an iron crystal (specifically, a unit cell). The architect A. Waterkeyn devoted the building to science. Next to the Atomium is the Mini-Europe park with 1:25 scale maquettes of famous buildings from across Europe.

The Manneken Pis, a bronze fountain of a small peeing boy is a famous tourist attraction and symbol of the city.

Other landmarks include the Cinquantenaire park with its triumphal arch and nearby museums, the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Brussels Stock Exchange, the Palace of Justice and the buildings of EU institutions in the European Quarter.

Cultural facilities include the Brussels Theatre and the La Monnaie Theatre and opera house. There is a wide array of museums, from the Royal Museum of Fine Art to the Museum of the Army and the Comic Museum. Brussels also has a lively music scene, with everything from opera houses and concert halls to music bars and techno clubs.

The city centre is notable for its Flemish town houses. Also particularly striking are the buildings in the Art Nouveau style by the Brussels architect Victor Horta. Some of Brussels' districts were developed during the heyday of Art Nouveau, and many buildings are in this style. Good examples include Schaerbeek, Etterbeek, Ixelles, and Saint-Gilles. Another example of Brussels Art Nouveau is the Stoclet Palace, by the Viennese architect Josef Hoffmann. The modern buildings of Espace Leopold complete the picture.

Arts

The city has had a renowned artist scene for many years. The famous Belgian surrealist René Magritte, for instance, studied in Brussels. The city was also home of Impressionist painters like Anna Boch from the Artist Group Les XX. The city is also a capital of the comic strip;[4] some treasured Belgian characters are Lucky Luke, Tintin, Cubitus, Gaston Lagaffe and Marsupilami. Throughout the city, walls are painted with large motifs of comic book characters. The totality of all these mural paintings is known as the Brussels' Comic Book Route. Also, the interiors of some Metro stations are designed by artists. The Belgian Comics Museum combines two artistic leitmotifs of Brussels, being a museum devoted to Belgian comic strips, housed in the former Waucquez department store, designed by Victor Horta in the Art Nouveau style.

Brussels contains over 80 museums,[68] including the Museum of Modern Art,[69] and the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. The museum has an extensive collection of various painters, such as the Flemish painters like Bruegel, Rogier van der Weyden, Robert Campin, Anthony van Dyck, and Jacob Jordaens. The recently opened Magritte Museum houses the world's largest collection of the works of the surrealist René Magritte.

The King Baudouin Stadium is a concert and competition facility with a 50,000 seat capacity, the largest in Belgium. The site was formerly occupied by the Heysel Stadium.

Gastronomy

Brussels is known for its local waffle, its chocolate, its French fries and its numerous types of beers. The Brussels sprout was first cultivated in Brussels, hence its name.

The gastronomic offer includes approximately 1,800 restaurants, and a number of high quality bars. Belgian cuisine is known among connoisseurs [who?] as one of the best in Europe.[weasel words] In addition to the traditional restaurants, there is a large number of cafés, bistros, and the usual range of international fast food chains. The cafés are similar to bars, and offer beer and light dishes; coffee houses are called the Salons de Thé. Also widespread are brasseries, which usually offer a large number of beers and typical national dishes.

Belgian cuisine is characterised by the combination of French cuisine with the more hearty Flemish fare. Notable specialities include Brussels waffles (gaufres) and mussels (usually as "moules frites", served with fries). The city is a stronghold of chocolate and pralines manufacturers with renowned companies like Neuhaus, Leonidas and Godiva. Numerous friteries are spread throughout the city, and in tourist areas, fresh, hot, waffles are also sold on the street.

In addition to the regular selection of Belgian beer, the famous lambic style of beer is only brewed in and around Brussels, and the yeasts have their origin in the Senne valley. In mild contrast to the other versions, Kriek (cherry beer) enjoys outstanding popularity, as it does in the rest of Belgium. Kriek is available in almost every bar or restaurant.

Economy

Serving as the centre of administration for Europe, Brussels' economy is largely service-oriented. It is dominated by regional and world headquarters of multinationals, by European institutions, by various administrations, and by related services, though it does have a number of notable craft industries, such as the Cantillon Brewery, a lambic brewery founded in 1900.

Education

There are several universities in Brussels. The two main universities are the Université Libre de Bruxelles, a French-speaking university with about 20,000 students in three campuses in the city (and two others outside),[70] and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, a Dutch-speaking university with about 10,000 students.[71] Both universities originate from a single ancestor university founded in 1834, namely the Free University of Brussels, which was split in 1970 at about the same time the Flemish and French Communities gained legislative power over the organisation of higher education.

Other universities include the Facultés Universitaires Saint-Louis with 2,000 students,[72] the Hogeschool-Universiteit Brussel, the Royal Military Academy, a military college established in 1834 by a French colonel[73] and two drama schools founded in 1982: the French-speaking Conservatoire Royal and the Dutch-speaking Koninklijk Conservatorium.[74][75]

Still other universities have campuses in Brussels, such as the Université Catholique de Louvain that has had its medical faculty in the city since 1973.[76] In addition, the University of Kent's Brussels School of International Studies is a specialised postgraduate school offering advanced international studies and Boston University Brussels was established in 1972 and offers masters degrees in business administration and international relations. Due to the post-war international presence in the city, there are also a number of international schools, including the International School of Brussels with 1,450 pupils between 2½ and 18,[77] the British School of Brussels, and the four European Schools, which provide free education for the children of those working in the EU institutions. The combined student population of the four European Schools in Brussels is currently around 10 000.[78]

Transport

- main article: Transport in Brussels

Air

Brussels is served by Brussels Airport, located in the nearby Flemish municipality of Zaventem, and by the smaller Brussels South Charleroi Airport, located near Charleroi (Wallonia), some 50 km (30 mi) from Brussels. Brussels is also served by direct high-speed rail links: to London by the Eurostar train via the Channel Tunnel (1hr 51 min); to Amsterdam, Paris (1hr 25 min) and Cologne by the Thalys; and to Cologne and Frankfurt by the German ICE.

Water

Brussels also has its own port on the Brussels-Scheldt Maritime Canal located in the northwest of the city. The Brussels-Charleroi Canal connects Brussels with the industrial areas of Wallonia.

Public transport

The Brussels Metro dates back to 1976, but underground lines known as premetro have been serviced by tramways since 1968. A comprehensive bus and tram network also covers the city.

An interticketing system means that a STIB ticket holder can use the train or long-distance buses inside the city. The commuter services operated by De Lijn, TEC and SNCB/NMBS will in the next few years be augmented by the Brussels RER network around the city.

Since 2003 Brussels has had a car-sharing service operated by the Bremen company Cambio in partnership with the STIB and local ridesharing company taxi stop. In 2006 shared bicycles were also introduced.

Road network

In medieval times Brussels stood at the intersection of routes running north-south (the modern Rue Haute/Hoogstraat) and east-west (Chaussée de Gand/Gentsesteenweg-Rue du Marché aux Herbes/Grasmarkt-Rue de Namur/Naamsestraat). The ancient pattern of streets radiating from the Grand Place in large part remains, but has been overlaid by boulevards built over the River Senne, over the city walls and over the railway connection between the North and South Stations.

As one expects of a capital city, Brussels is the hub of the fan of old national roads, the principal ones being clockwise the N1 (N to Breda), N2 (E to Maastricht), N3 (E to Aachen), N4 (SE to Luxembourg) N5 (S to Rheims), N6 (SW to Maubeuge), N8 (W to Koksijde) and N9 (NW to Ostend).[79] Usually named chaussées/steenwegen, these highways normally run in a straight line, but on occasion lose themselves in a maze of narrow shopping streets.

The town is skirted by the European route E19 (N-S) and the E40 (E-W), while the E411 leads away to the SE. Brussels has an orbital motorway, numbered R0 (R-zero) and commonly referred to as the "ring" (French: ring Dutch: grote ring). It is pear-shaped as the southern side was never built as originally conceived, owing to residents' objections.

The city centre, sometimes known as "the pentagon", is surrounded by an inner ring road, the "small ring" (French: petite ceinture, Dutch: kleine ring ), a sequence of boulevards formally numbered R20. These were built upon the site of the second set of city walls following their demolition. Metro line 2 runs under much of these.

On the eastern side of the city, the R21 (French: grande ceinture, grote ring in Dutch) is formed by a string of boulevards that curves round from Laeken (Laken) to Uccle (Ukkel). Some premetro stations (see Brussels Metro) were built on that route. A little further out, a stretch numbered R22 leads from Zaventem to Saint-Job.

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Brussels is twinned with the following cities:

See also

References

- ^ a b c "The Belgian Constitution (English version)" (PDF). Belgian House of Representatives. January 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

Article 3: Belgium comprises three Regions: the Flemish Region, the Walloon Region and the Brussels Region. Article 4: Belgium comprises four linguistic regions: the Dutch-speaking region, the French speaking region, the bilingual region of Brussels-Capital and the German-speaking region.

- ^ a b c "Brussels-Capital Region: Creation". Centre d'Informatique pour la Région Bruxelloise (Brussels Regional Informatics Center). 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

Since 18 June 1989, the date of the first regional elections, the Brussels-Capital Region has been an autonomous region comparable to the Flemish and Walloon Regions.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) - ^ "Brussels". City-Data.com. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

- ^ a b Herbez, Ariel (30 May 2009). "Bruxelles, capitale de la BD". Le Temps (in French). Switzerland. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

Plus que jamais, Bruxelles mérite son statut de capitale de la bande dessinée.

- ^ "Cheap flights to Brussels". Easyjet. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ Population per municipality as of 1 January 2017 (XLS; 397 KB)

- ^ It is the de facto EU capital as it hosts all major political institutions—though Parliament formally votes in Strasbourg, most political work is carried out in Brussels—and as such is considered the capital by definition. However, it should be noted that it is not formally declared in that language, though its position is spelled out in the Treaty of Amsterdam. See the section dedicated to this issue.

- ^ a b c Demey, Thierry (2007). Brussels, capital of Europe. S. Strange (trans.). Brussels: Badeaux. ISBN 2-9600414-2-9.

- ^ "Welcome to Brussels". Brussels.org. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ "History of Brussels". Brussels.org. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ Statistics Belgium; Population de droit par commune au 1 janvier 2008 (excel-file) Population of all municipalities in Belgium, as of 1 January 2008. Retrieved on 18 October 2008. [dead link]

- ^ Statistics Belgium; De Belgische Stadsgewesten 2001 (pdf-file) Definitions of metropolitan areas in Belgium. The metropolitan area of Brussels is divided into three levels. First, the central agglomeration (geoperationaliseerde agglomeratie) with 1,451,047 inhabitants (2008-01-01, adjusted to municipal borders). Adding the closest surroundings (banlieue) gives a total of 1,831,496. And, including the outer commuter zone (forensenwoonzone) the population is 2,676,701. Retrieved on 18 October 2008. [dead link]

- ^ "Protocol (No 6) on the location of the seats of the institutions and of certain bodies, offices, agencies and departments of the European Union, Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, OJ C 83, 30.3.2010, p. 265–265". EUR-Lex. 30 March 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ "Europe | Country profiles | Country profile: Belgium". BBC News. 14 June 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ Hughes, Dominic (15 July 2008). "Europe | Analysis: Where now for Belgium?". BBC News. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ Geert van Istendael Arm Brussel, uitgeverij Atlas, ISBN 90-450-0853-X

- ^ "Brussels History". City-data.com. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ Template:Fr Jean Baptiste D'Hane, François Huet, P.A. Lenz, H.G. Moke (1837). Nouvelles archives historiques, philosophiques, et littéraires. Vol. 1. Gent: C. Annoot- Braeckman. p. 405. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Template:Nl Zo ontstond Brussel Vlaamse Gemeenschapscommissie – Commission of the Flemish Community in Brussels

- ^ "Communes". Centre d'Informatique pour la Région Bruxelloise. 2004. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

- ^ a b "Managing across levels of government" (PDF). OECD. 1997. pp. 107, 110. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ a b Picavet, Georges (29 April 2003). "Municipalities (1795-now)". Georges Picavet. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

- ^ "Brussels Capital-Region". Georges Picavet. 4 June 2005. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

- ^ Template:Fr icon Personal website Lexilogos located in the Provence, on European Languages (English, French, German, Dutch, and so on) – French-speakers in Brussels are estimated at about 90% (estimation, not an 'official' number because there are no linguistic census in Belgium)

- ^ Template:Fr icon Langues majoritaires, langues minoritaires, dialectes et NTIC by Simon Petermann, Professor at the University of Liège, Wallonia, Belgium

- ^ a b Flemish Academic E. Corijn, at a Colloquium regarding Brussels, on 5 December 2001, states that in Brussels there is 91% of the population speaking French at home, either alone or with another language, and there is about 20% speaking Dutch at home, either alone (9%) or with French (11%) – After ponderation, the repartition can be estimated at between 85 and 90% French-speaking, and the remaining are Dutch-speaking, corresponding to the estimations based on languages chosen in Brussels by citizens for their official documents (ID, driving licenses, weddings, birth, death, and so on) ; all these statistics on language are also available at Belgian Department of Justice (for weddings, birth, death), Department of Transport (for Driving licenses), Department of Interior (for IDs), because there are no means to know precisely the proportions since Belgium has abolished 'official' linguistic censuses, thus official documents on language choices can only be estimations.

- ^ Template:Fr icon Personal website Lexilogos located in the Provence, on European Languages (English, French, German, Dutch, and so on) – Dutch-speakers in Brussels are estimated at about 10% (estimation, not an 'official' number because there are no linguistic census in Belgium)

- ^ a b IS 2007 – Population (Tableaux)

- ^ "Title VII". Fed-parl.be. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ a b Template:Nl VGC Template:Fr COCOF

- ^ "Brussels, the capital of Flanders". Flemish Department of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 6 November 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Procedure contained in art. 138 of the Belgian Constitution

- ^ Procedure in art. 137 of the Belgian Constitution

- ^ Brussels, an international city and European capital Université Libre de Bruxelles

- ^ a b Brussels: home to international organisations diplomatie.be

- ^ a b E!Sharp magazine, January–February 2007 issue: Article "A tale of two cities".

- ^ Andrew Rettman. "Euobserver.com". Euobserver.com. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ Leigh Phillips. "Euobserver.com". Euobserver.com. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ a b European Navigator Seat of the European Commission

- ^ a b European Commission publication: Europe in Brussels 2007

- ^ Wheatley, Paul (2 October 2006). "The two-seat parliament farce must end". Café Babel. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ^ Stark, Christine. "Evolution of the European Council: The implications of a permanent seat" (PDF). Dragoman.org. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Vucheva, Elitsa (5 September 2007). "EU quarter in Brussels set to grow". EU Observer. Retrieved 27 September 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b "Non-Profit Data". Npdata.be. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ T. Eggerickx et al., De allochtone bevolking in België, Algemene Volks- en Woningtelling op 1 maart 1991, Monografie nr. 3, 1999, Nationaal Instituut voor de Statistiek

- ^

"Van autochtoon naar allochtoon". De Standaard (newspaper) online (in Dutch). Retrieved 5 May 2007.

Meer dan de helft van de Brusselse bevolking is van vreemde afkomst. In 1961 was dat slechts 7 procent. (More than half of the Brussels' population is of foreign origin. In 1961 this was only 7 percent.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^

Van Parijs, Philippe, Professor of economic and social ethics at the UCLouvain, Visiting Professor at Harvard University and the KULeuven. "Belgium's new linguistic challenges" (pdf 0.7 MB). KVS Express (supplement to newspaper De Morgen) March–April 2007: Article from original source (pdf 4.9 MB) pages 34–36 republished by the Belgian Federal Government Service (ministry) of Economy – Directorate–general Statistics Belgium. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) – The linguistic situation in Belgium (and in particular various estimations of the population speaking French and Dutch in Brussels) is discussed in detail. - ^ The Brussels region's 56% residents of foreign origin include several percents of either Dutch people or native speakers of French, thus roughly half of the inhabitants do not speak either French or Dutch as primary language.

- ^ "Population et ménages" (pdf 1.4 MB) (in French). IBSA Cellule statistique – Min. Région Bruxelles-Capitale (Statistical cell – Ministry of the Brussels-Capital Region). Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- ^ Michaels, Adrian (8 August 2009). "Muslim Europe: the demographic time bomb transforming our continent". Telegraph.

- ^ Template:Nl ”Taalgebruik in Brussel en de plaats van het Nederlands. Enkele recente bevindingen”, Rudi Janssens, Brussels Studies, Nummer 13, 7 January 2008 (see page 4).

- ^ "Wallonie – Bruxelles, Le Service de la langue française" (in French). 19 May 1997. Archived from the original on 5 January 2007.

- ^ "Villes, identités et médias francophones: regards croisés Belgique, Suisse, Canada" (in French). University of Laval, Quebec. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Manneken-Pis schrijft slecht Nederlands" (in Dutch). Het Nieuwsblad. 25 August 2007.

- ^ G. Geerts. "Nederlands in België, Het Nederlands bedreigd en overlevend". Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse taal (in Dutch). M.C. van den Toorn, W. Pijnenburg, J.A. van Leuvensteijn and J.M. van der Horst. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Template:Nl "Thuis in gescheiden werelden" – De migratoire en sociale aspecten van verfransing te Brussel in het midden van de 19e eeuw", BTNG-RBHC, XXI, 1990, 3–4, pp. 383–412, Machteld de Metsenaere, Eerst aanwezend assistent en docent Vrije Universiteit Brussel

- ^ J. Fleerackers, Chief of staff of the Belgian Minister for Dutch culture and Flemish affairs (1973). "De historische kracht van de Vlaamse beweging in België: de doelstellingen van gister, de verwezenlijkingen vandaag en de culturele aspiraties voor morgen". Digitale bibliotheek voor Nederlandse Letteren (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Kort historisch overzicht van het OVV" (in Dutch). Overlegcentrum van Vlaamse Verenigingen. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Bisbilles dans le Grand Bruxelles" (in French). Le Monde. 2 October 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Sint-Stevens-Woluwe: een unicum in de Belgische geschiedenis" (in Dutch). Overlegcentrum van Vlaamse Verenigingen. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Brussels". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Bruxelles dans l'oeil du cyclone" (in French). France 2. 14 November 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "La Flandre ne prendra pas Bruxelles..." (in French). La Libre Belgique. 28 May 2006.

- ^ The six municipalities with language facilities around Brussels are Wemmel, Kraainem, Wezembeek-Oppem, Sint-Genesius-Rode, Linkebeek and Drogenbos.

- ^ "Une question: partir ou rester?" (in French). La Libre Belgique. 24 January 2005.

- ^ "Position commune des partis démocratiques francophones" (in French). Union des Francophones (UF), Province of Flemish Brabant. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Bruxelles-capitale: une forte identité" (in French). France 2. 14 November 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Museums in Brussels". Bruxelles.irisnet.be. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Museum of Modern Art in Brussels. Museum Moderne Kunst Brussel. Musée d'art moderne Bruxelles". Trabel.com. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ "Presentation of the Université libre de Bruxelles". Université Libre de Bruxelles. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "About the University: Culture and History". Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Institution: Historique". Facultés Universitaires Saint Louis. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "What makes the RMA so special?". Belgian Royal Military Academy. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Petite histoire du Conservatoire royal de Bruxelles". Conservatoire Royal. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Koninklijk Conservatorium Brussel". Koninklijk Conservatorium. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "L'histoire de l'UCL à Bruxelles". Université Catholique de Louvain. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "ISB Profile". International School of Brussels. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Background". Schola Europaea. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Belgian N roads". Autosnelwegen.net. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Sister Cities". Beijing Municipal Government. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- ^ "Mapa Mundi de las ciudades hermanadas". Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Foreign relations of Moscow". Mos.ru. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Prague Partner Cities" (in Czech). 2009 Magistrát hl. m. Prahy. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Twinning Cities: International Relations" (PDF). Municipality of Tirana. www.tirana.gov.al. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ "Protocol and International Affairs". DC Office of the Secretary. Retrieved 12 July 2008.