Globalization

Globalization is the process of international integration arising from the interchange of world views, products, ideas, and other aspects of culture.[1][2] Put in simple terms, globalization refers to processes that promote world-wide exchanges of national and cultural resources. Advances in transportation and telecommunications infrastructure, including the rise of the Internet, are major factors in globalization, generating further interdependence of economic and cultural activities.[3]

Though several scholars place the origins of globalization in modern times, others trace its history long before the European age of discovery and voyages to the New World. Some even trace the origins to the third millennium BCE.[4][5] Since the beginning of the 20th century, the pace of globalization has proceeded at an exponential rate.[6]

In 2000, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) identified four basic aspects of globalization: trade and transactions, capital and investment movements, migration and movement of people and the dissemination of knowledge.[7] Further, environmental challenges such as climate change, cross-boundary water and air pollution, and over-fishing of the ocean are linked with globalization.[8] Globalizing processes affect and are affected by business and work organization, economics, socio-cultural resources, and the natural environment.

Overview

Humans have interacted over long distances for thousands of years. The overland Silk Road that connected Asia, Africa and Europe is a good example of the transformative power of international exchange that existed in the "Old World". Philosophy, religion, language, the arts, and other aspects of culture spread and mixed as nations exchanged products and ideas. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Europeans made important discoveries in their exploration of the oceans, including the start of transatlantic travel to the "New World" of the Americas. Global movement of people, goods, and ideas expanded significantly in the following centuries. Early in the 19th century, the development of new forms of transportation (such as the steamship and railroads) and telecommunications that "compressed" time and space allowed for increasingly rapid rates of global interchange.[9] In the 20th century, road vehicles and airlines made transportation even faster, and the advent of electronic communications, most notably mobile phones and the Internet, connected billions of people in new ways leading into the 21st century.

Etymology and usage

The term globalization is derived from the word globalize, which refers to the emergence of an international network of social and economic systems.[10] One of the earliest known usages of the term as the noun was in 1930 in a publication entitled Towards New Education where it denoted a holistic view of human experience in education.[11] A related term, corporate giants, was coined by Charles Taze Russell in 1897[12] to refer to the largely national trusts and other large enterprises of the time. By the 1960s, both terms began to be used as synonyms by economists and other social scientists. It then reached the mainstream press in the later half of the 1980s. Since its inception, the concept of globalization has inspired competing definitions and interpretations, with antecedents dating back to the great movements of trade and empire across Asia and the Indian Ocean from the 15th century onwards.[13] Due to the complexity of the concept, research projects, articles, and discussions often remain focused on a single aspect of globalization.[1]

Roland Robertson, professor of sociology at University of Aberdeen, was the first person to define globalization as "the compression of the world and the intensification of the consciousness of the world as a whole."[14]

Sociologists Martin Albrow and Elizabeth King define globalization as:

…all those processes by which the peoples of the world are incorporated into a single world society.[2]

In The Consequences of Modernity, Anthony Giddens uses the following definition:

Globalization can thus be defined as the intensification of worldwide social relations which link distant localities in such a way that local happenings are shaped by events occurring many miles away and vice versa.[15]

In Global Transformations David Held, et al., study the definition of globalization:

Although in its simplistic sense globalization refers to the widening, deepening and speeding up of global interconnection, such a definition begs further elaboration. … Globalization can be located on a continuum with the local, national and regional. At one end of the continuum lie social and economic relations and networks which are organized on a local and/or national basis; at the other end lie social and economic relations and networks which crystallize on the wider scale of regional and global interactions. Globalization can be taken to refer to those spatial-temporal processes of change which underpin a transformation in the organization of human affairs by linking together and expanding human activity across regions and continents. Without reference to such expansive spatial connections, there can be no clear or coherent formulation of this term. … A satisfactory definition of globalization must capture each of these elements: extensity (stretching), intensity, velocity and impact.[16]

Swedish journalist Thomas Larsson, in his book The Race to the Top: The Real Story of Globalization, states that globalization:

is the process of world shrinkage, of distances getting shorter, things moving closer. It pertains to the increasing ease with which somebody on one side of the world can interact, to mutual benefit, with somebody on the other side of the world.[17]

The journalist Thomas L. Friedman popularized the term "flat world", arguing that globalized trade, outsourcing, supply-chaining, and political forces had permanently changed the world, for better and worse. He asserted that the pace of globalization was quickening and that its impact on business organization and practice would continue to grow.[18]

Economist Takis Fotopoulos defined "economic globalization" as the opening and deregulation of commodity, capital and labor markets that led toward present neoliberal globalization. He used "political globalization" to refer to the emergence of a transnational elite and a phasing out of the nation-state. "Cultural globalization", he used to reference the worldwide homogenization of culture. Other of his usages included "ideological globalization", "technological globalization" and "social globalization".[19]

In 2000, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) identified four basic aspects of globalization: trade and transactions, capital and investment movements, migration and movement of people and the dissemination of knowledge.[20] With regards to trade and transactions, developing countries increased their share of world trade, from 19 percent in 1971 to 29 percent in 1999. However, there is great variation among the major regions. For instance, the newly industrialized economies (NIEs) of Asia prospered, while African countries as a whole performed poorly. The makeup of a country's exports is an important indicator for success. Manufactured goods exports soared, dominated by developed countries and NIEs. Commodity exports, such as food and raw materials were often produced by developing countries: commodities' share of total exports declined over the period. Following from this, capital and investment movements can be highlighted as another basic aspect of globalization. Private capital flows to developing countries soared during the 1990s, replacing "aid" or development assistance which fell significantly after the early 1980s. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) became the most important category. Both portfolio investment and bank credit rose but they have been more volatile, falling sharply in the wake of the financial crisis of the late 1990s. The migration and movement of people can also be highlighted as a prominent feature of the globalization process. In the period between 1965–90, the proportion of the labor forces migrating approximately doubled. Most migration occurred between developing countries and Least Developed Countries (LDCs). The flow of migrants to advanced economic countries was claimed to provide a means through which global wages converge. The IMF study noted the potential for skills to be transferred back to developing countries as wages in those a countries rise. Lastly, the dissemination of knowledge has been an integral aspect of globalization. Technological innovations (or technological transfer) benefit most the developing and Least Developing countries (LDCs), as for example in the adoption of mobile phones. [21]

History

There are both distal and proximate causes that can be traced in the historical factors affecting globalization. Large-scale globalization began in the 19th century.[9]

Archaic

The German historical economist and sociologist Andre Gunder Frank argues that a form of globalization began with the rise of trade links between Sumer and the Indus Valley Civilization in the third millennium B.C.E.[4] This archaic globalization existed during the Hellenistic Age, when commercialized urban centers enveloped the axis of Greek culture that reached from India to Spain, including Alexandria and the other Alexandrine cities. Early on, the geographic position of Greece and the necessity of importing wheat forced the Greeks to engage in maritime trade. Trade in ancient Greece was largely unrestricted: the state controlled only the supply of grain.

There were trade links between the Roman Empire, the Parthian Empire, and the Han Dynasty. The increasing commercial links between these powers took form in the Silk Road, which began in western China, reached the boundaries of the Parthian empire, and continued to Rome.[22] As many as three hundred Greek ships sailed each year between the Greco-Roman world and India. Annual trade volume may have reached 300,000 tons.[23]

By traveling past the Tarim Basin region, the Chinese of the Han Dynasty learned of powerful kingdoms in Central Asia, Persia, India, and the Middle East with the travels of the Han Dynasty envoy Zhang Qian in the 2nd century BC. From 104 BC to 102 BC Emperor Wu of Han waged war against the Yuezhi who controlled Dayuan, a Hellenized kingdom of Fergana established by Alexander the Great in 329 BC. Gan Ying, the emissary of General Ban Chao, perhaps traveled as far as Roman-era Syria in the late 1st century AD. After these initial discoveries the focus of Chinese exploration shifted to the maritime sphere, although the Silk Road leading all the way to Europe continued to be China's most lucrative source of trade.

From about the 1st century, India started to strongly influence Southeast Asian countries. Trade routes linked India with southern Burma, central and southern Siam, lower Cambodia and southern Vietnam and numerous urbanized coastal settlements were established there.

The Islamic Golden Age added another stage of globalization, when Radhanite (Jewish) and Muslim traders and explorers established trade routes, resulting in a globalization of agriculture, trade, knowledge and technology. Crops such as sugar and cotton became widely cultivated across the Muslim world in this period, while widespread knowledge of Arabic and the Hajj created a cosmopolitan culture.[24]

The advent of the Mongol Empire, though destabilizing to the commercial centers of the Middle East and China, greatly facilitated travel along the Silk Road. The Pax Mongolica of the thirteenth century included the first international postal service, as well as the rapid transmission of epidemic diseases such as bubonic plague across Central Asia.[25] Up to the sixteenth century, however, the largest systems of international exchange were limited to southern Eurasia (an area where the Balkans and Greece interact with Turkey, Egypt, the Levant, Persia and the Arabian Peninsula, continuing over the Arabian Sea to India).

Many Chinese merchants chose to settle down in the Southeast Asian ports such as Champa, Cambodia, Sumatra, Java, and married the native women. Their children carried on trade.[26][27]

Italian city states embraced free trade and merchants established trade links with faraway places, giving birth to the Renaissance. Marco Polo was a merchant traveler[28] from the Venetian Republic in modern-day Italy whose travels are recorded in Il Milione, a book that played a significant role in introducing Europeans to Central Asia and China. The pioneering journey of Marco Polo inspired Christopher Columbus[29] and other European explorers of the following centuries.

Proto-globalization

The next phase, known as proto-globalization, was characterized by the rise of maritime European empires, in the 16th and 17th centuries, first the Portuguese and Spanish Empires, and later the Dutch and British Empires. In the 17th century, world trade developed further when chartered companies like the British East India Company (founded in 1600) and the Dutch East India Company (founded in 1602, often described as the first multinational corporation in which stock was offered) were established.[30]

The Age of Discovery added the New World to the equation,[31] beginning in the late 15th century. Portugal and Castile sent the first exploratory voyages[32] around the Horn of Africa and to the Americas, reached in 1492 by the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus. Global trade growth continued with the European colonization of the Americas initiating the Columbian Exchange,[33] the exchange of plants, animals, foods, human populations (including slaves), communicable diseases, and culture between the Eastern and Western hemispheres. New crops that had come from the Americas via the European seafarers in the 16th century significantly contributed to world population growth.[34]

Modern

In the 19th century, steamships reduced the cost of international transport significantly and railroads made inland transport cheaper. The transport revolution occurred some time between 1820 and 1850.[9] More nations embraced international trade.[9] Globalization in this period was decisively shaped by nineteenth-century imperialism such as in Africa and Asia.

Globalization took a big step backwards during the First World War, the Great Depression, and the Second World War. Integration of rich countries didn't recover to previous levels before the 1980s.[citation needed]

After the Second World War, work by politicians led to the Bretton Woods conference, an agreement by major governments to lay down the framework for international monetary policy, commerce and finance, and the founding of several international institutions intended to facilitate economic growth multiple rounds of trade opening simplified and lowered trade barriers. Initially, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), led to a series of agreements to remove trade restrictions. GATT's successor was the World Trade Organization (WTO), which created an institution to manage the trading system. Exports nearly doubled from 8.5% of total gross world product in 1970 to 16.2% in 2001.[35] The approach of using global agreements to advance trade stumbled with the failure of the Doha round of trade-negotiation. Many countries then shifted to bilateral or smaller multilateral agreements, such as the 2011 South Korea–United States Free Trade Agreement.

Since the 1970s, aviation has become increasingly affordable to middle classes in developed countries. Open skies policies and low-cost carriers have helped to bring competition to the market.

In the 1990s, the growth of low cost communication networks cut the cost of communicating between different countries. More work can be performed using a computer without regard to location. This included accounting, software development, and engineering design. In late 2000s, much of the industrialized world entered into the Great Recession,[36] which may have slowed the process, at least temporarily.[37][38][39]

Aspects

Global business organization

With improvements in transportation and communication, international business grew rapidly after the beginning of the 20th century. International business includes all commercial transactions (private sales, investments, logistics,and transportation) that take place between two or more regions, countries and nations beyond their political boundary. Usually, private companies undertake such transactions for profit.[40] Such business transactions involve economic resources such as capital, natural and human resources used for international production of physical goods and services such as finance, banking, insurance, construction and other productive activities.[41]

International business arrangements have led to the formation of multinational enterprises (MNE), companies that have a worldwide approach to markets and production or one with operations in more than one country. An MNE is often called multinational corporation (MNC) or transnational company (TNC). Well known MNCs include fast food companies such as McDonald's and Yum Brands, vehicle manufacturers such as General Motors, Ford Motor Company and Toyota, consumer electronics companies like Samsung, LG and Sony, and energy companies such as ExxonMobil, Shell and BP. Most of the largest corporations operate in multiple national markets.

Businesses argue that survival in the new global marketplace requires companies to source goods, services, labor and materials overseas to continuously upgrade their products and technology in order to survive increased competition.

International trade

An absolute trade advantage exists when countries can produce a commodity with less costs per unit produced than could its trading partner. By the same reasoning, it should import commodities in which it has an absolute disadvantage.[42] While there are possible gains from trade with absolute advantage, comparative advantage—that is, the ability to offer goods and services at a lower marginal and opportunity cost—extends the range of possible mutually beneficial exchanges. In a globalized business environment, companies argue that the comparative advantages offered by international trade have become essential to remaining competitive.

Trade agreements, economic blocks and special trade zones

A Special Economic Zone (SEZ) is a geographical region that has economic and other laws that are more free-market-oriented than a country's typical or national laws. "Nationwide" laws may be suspended inside these special zones. The category 'SEZ' covers many areas, including Free Trade Zones (FTZ), Export Processing Zones (EPZ), Free Zones (FZ), Industrial parks or Industrial Estates (IE), Free Ports, Urban Enterprise Zones and others. Usually the goal of a structure is to increase foreign direct investment by foreign investors, typically an international business or a multinational corporation (MNC). These are designated areas in which companies are taxed very lightly or not at all in order to encourage economic activity. Free ports have historically been endowed with favorable customs regulations, e.g., the free port of Trieste. Very often free ports constitute a part of free economic zones.

A FTZ is an area within which goods may be landed, handled, manufactured or reconfigured, and reexported without the intervention of the customs authorities. Only when the goods are moved to consumers within the country in which the zone is located do they become subject to the prevailing customs duties. Free trade zones are organized around major seaports, international airports, and national frontiers—areas with many geographic advantages for trade.[43] It is a region where a group of countries has agreed to reduce or eliminate trade barriers.[44]

A free trade area is a trade bloc whose member countries have signed a free-trade agreement, which eliminates tariffs, import quotas, and preferences on most (if not all) goods and services traded between them. If people are also free to move between the countries, in addition to free-trade area, it would also be considered an open border. The European Union, for example, a confederation of 27 member states, provides both a free trade area and an open border.

Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZ) are industrial parks that house manufacturing operations in Jordan and Egypt. They are a special free trade zones established in collaboration with neighboring Israel to take advantage of the free trade agreements between the United States and Israel. Under the trade agreements with Jordan as laid down by the United States, goods produced in QIZ-notified areas can directly access US markets without tariff or quota restrictions, subject to certain conditions. To qualify, goods produced in these zones must contain a small portion of Israeli input. In addition, a minimum 35% value to the goods must be added to the finished product. The brainchild of Jordanian businessman Omar Salah, the first QIZ was authorized by the United States Congress in 1997.

The Asia-Pacific has been described as "the most integrated trading region on the planet" because its intra-regional trade accounts probably for as much as 50-60% of the region's total imports and exports.[45] It has also extra-regional trade: consumer goods exports such as televisions, radios, bicycles, and textiles into the United States, Europe, and Japan fueled the economic expansion.[46]

The ASEAN Free Trade Area[47] is a trade bloc agreement by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations supporting local manufacturing in all ASEAN countries. The AFTA agreement was signed on 28 January 1992 in Singapore. When the AFTA agreement was originally signed, ASEAN had six members, namely, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. Vietnam joined in 1995, Laos and Myanmar in 1997 and Cambodia in 1999.

Drug trade

In 2010 the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reported that the global drug trade generated more than $320 billion a year in revenues.[48] Worldwide, the UN estimates there are more than 50 million regular users of heroin, cocaine and synthetic drugs.[49] The international trade of endangered species was second only to drug trafficking among smuggling "industries".[50] Traditional Chinese medicine often incorporates ingredients from all parts of plants, the leaf, stem, flower, root, and also ingredients from animals and minerals. The use of parts of endangered species (such as seahorses, rhinoceros horns, saiga antelope horns, and tiger bones and claws) resulted in a black market of poachers who hunt restricted animals.[51][52]

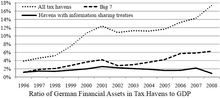

Tax havens

A tax haven is a state, country or territory where certain taxes are levied at a low rate or not at all, which are used by businesses for tax avoidance and tax evasion.[54] Individuals and/or corporate entities can find it attractive to establish shell subsidiaries or move themselves to areas with reduced or nil taxation levels. This creates a situation of tax competition among governments. Different jurisdictions tend to be havens for different types of taxes, and for different categories of people and/or companies.[55] States that are sovereign or self-governing under international law have theoretically unlimited powers to enact tax laws affecting their territories, unless limited by previous international treaties. The central feature of a tax haven is that its laws and other measures can be used to evade or avoid the tax laws or regulations of other jurisdictions.[56] In its December 2008 report on the use of tax havens by American corporations,[57] the U.S. Government Accountability Office was unable to find a satisfactory definition of a tax haven but regarded the following characteristics as indicative of it:

- nil or nominal taxes;

- lack of effective exchange of tax information with foreign tax authorities;

- lack of transparency in the operation of legislative, legal or administrative provisions;

- no requirement for a substantive local presence; and

- self-promotion as an offshore financial center.

A 2012 report from the Tax Justice Network estimated that between USD $21 trillion and $32 trillion is sheltered from taxes in unreported tax havens worldwide. If such wealth earns 3% annually and such capital gains were taxed at 30%, it would generate between $190 billion and $280 billion in tax revenues, more than any other tax shelters.[58] If such hidden offshore assets are considered, many countries with governments nominally in debt are shown to be net creditor nations.[59] However, the tax policy director of the Chartered Institute of Taxation expressed skepticism over the accuracy of the figures.[60] Daniel J. Mitchell of the Cato Institute says that the report also assumes, when considering notional lost tax revenue, that 100% money deposited offshore is evading payment of tax.[61]

Information systems

Multinational corporations face the challenge of developing global information systems for global data processing and decision-making. The Internet provides a broad area of services to business and individual users. Because the World Wide Web (WWW) can reach any Internet-connected computer in the world, the Internet is closely related to global information systems. A global information system is a data communication network that crosses national boundaries to access and process data in order to achieve corporate goals and strategic objectives.[62]

Across companies and continents, information standards ensure desirable characteristics of products and services such as quality, environmental friendliness, safety, reliability, efficiency and interchangeability at an economical cost. For businesses, widespread adoption of international standards means that suppliers can develop and offer products and services meeting specifications that have wide international acceptance in their sectors. According to the ISO, businesses using their International Standards are competitive in more markets around the world. The ISO develops standards by organizing technical committees of experts from the industrial, technical and business sectors who have asked for the standards and which subsequently put them to use. These experts may be joined by representatives of government agencies, testing laboratories, consumer associations, non-governmental organizations and academic circles.[63]

International tourism

Tourism is travel for recreational, leisure or business purposes. The World Tourism Organization defines tourists as people "traveling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes".[64] There are many forms of tourism such as agritourism, birth tourism, culinary tourism, cultural tourism, eco-tourism,extreme tourism, geotourism, heritage tourism, LGBT tourism, medical tourism, nautical tourism, pop-culture tourism, religious tourism, slum tourism, war tourism, and wildlife tourism

Globalization has made tourism a popular global leisure activity. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that up to 500,000 people are in flight at any one time.[65] In 2010, international tourism reached $919B, growing 6.5% over 2009.[66] In 2010, there were over 940 million international tourist arrivals worldwide, representing a growth of 6.6% when compared to 2009.[67] International tourism receipts grew to US$919 billion (€693 billion) in 2010, corresponding to an increase in real terms of 4.7%.[67]

As a result of the late-2000s recession, international travel demand suffered a strong slowdown from the second half of 2008 through the end of 2009. After a 5% increase in the first half of 2008, growth in international tourist arrivals moved into negative territory in the second half of 2008, and ended up only 2% for the year, compared to a 7% increase in 2007.[68] This negative trend intensified during 2009, exacerbated in some countries due to the outbreak of the H1N1 influenza virus, resulting in a worldwide decline of 4.2% in 2009 to 880 million international tourists arrivals, and a 5.7% decline in international tourism receipts.[69]

Economic globalization

Economic globalization is the increasing economic interdependence of national economies across the world through a rapid increase in cross-border movement of goods, service, technology and capital.[71] Whereas the globalization of business is centered around the diminution of international trade regulations as well as tariffs, taxes, and other impediments that suppresses global trade, economic globalization is the process of increasing economic integration between countries, leading to the emergence of a global marketplace or a single world market.[72] Depending on the paradigm, economic globalization can be viewed as either a positive or a negative phenomenon.

Economic globalization comprises the globalization of production, markets, competition, technology, and corporations and industries.[71] Current globalization trends can be largely accounted for by developed economies integrating with less developed economies, by means of foreign direct investment, the reduction of trade barriers as well as other economic reforms and, in many cases, immigration.

As an example, Chinese economic reform began to open China to the globalization in the 1980s. Scholars find that China has attained a degree of openness that is unprecedented among large and populous nations", with competition from foreign goods in almost every sector of the economy. Foreign investment helped to greatly increase quality, knowledge and standards, especially in heavy industry. China's experience supports the assertion that globalization greatly increases wealth for poor countries.[73] As of 2005–2007, the Port of Shanghai holds the title as the World's busiest port.[74][75][76]

Economic liberalization in India is the ongoing economic reforms in India that started in 1991. As of 2009, about 300 million people—equivalent to the entire population of the United States—have escaped extreme poverty.[77] In India, business process outsourcing has been described as the "primary engine of the country's development over the next few decades, contributing broadly to GDP growth, employment growth, and poverty alleviation".[78][79]

Measures

Indices

Measurement of economic globalization focuses on variables such as trade, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), portfolio investment, and income. However, newer indices attempt to measure globalization in more general terms, including variables related to political, social, cultural, and even environmental aspects of globalization.[80]

One index of globalization is the KOF Index, which measures the three main dimensions of globalization: economic, social, and political.[81]

| 2010 List by the KOF Index of Globalization | 2006 List by the A.T. Kearney/Foreign Policy Magazine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Measuring free trade policies

The Enabling Trade Index measures the factors, policies and services that facilitate the trade in goods across borders and to destination. It is made up of four sub-indexes: market access; border administration; transport and communications infrastructure; and business environment. The top 20 countries are:[82]

|

|

Sociocultural globalization

Culture

Cultural globalization has increased cross-cultural contacts but may be accompanied by a decrease in the uniqueness of once-isolated communities: sushi is available in Germany as well as Japan, but Euro-Disney outdraws the city of Paris, potentially reducing demand for "authentic" French pastry.[83][84][85] Globalisation's contribution to the alienation of individuals from their traditions may be modest compared to the impact of modernity itself, as alleged by existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. Globalization has expanded recreational opportunities by spreading pop culture, particularly via the Internet and satellite television.

Religious movements were among the earliest cultural forces to globalize, spread by force, migration, evangelists, imperialists and traders. Christianity, Islam, Buddhism and more recently sects such as Mormonism have taken root and influenced endemic cultures in places far from their origins.[86]

Conversi claimed in 2010 that globalization was predominantly driven by the outward flow of culture and economic activity from the United States and was better understood as Americanization,[87][88] or Westernization. For example, the two most successful global food/beverage outlets are American companies, McDonald's and Starbucks, are often cited as examples of globalization, with over 32,000[89] and 18,000 locations operating worldwide, respectively as of 2008.[90]

The term globalization implies transformation. Cultural practices including traditional music can be lost and/or turned into a fusion of traditions. Globalization can trigger a state of emergency for the preservation of musical heritage. Archivists must attempt to collect, record or transcribe repertoire before melodies are assimilated or modified. Local musicians struggle for authenticity and to preserve local musical traditions. Globalization can lead performers to discard traditional instruments. Fusion genres can become interesting fields of analysis.[91]

Globalization gave support to the World Music phenomenon by allowing locally-recorded to reach western audiences searching for new ideas and sounds. For example, Western musicians have adopted many innovations that originated in other cultures.[92]

The term was originally intended for ethnic-specific music, though globalization is expanding its scope; it now often includes hybrid sub-genres such as World fusion, Global fusion, Ethnic fusion[93] and Worldbeat[94][95]

Music flowed outward from the west as well. Anglo-American pop music spread across the world through MTV. Dependency Theory explained that the world was an integrated, international system. Musically, this translated into the loss of local musical identity.[96]

Bourdieu claimed that the perception of consumption can be seen as self-identification and the formation of identity. Musically, this translates into each being having his own musical identity based on likes and tastes. These likes and tastes are greatly influenced by culture as this is the most basic cause for a person's wants and behavior. The concept of one's own culture is now in a period of change due to globalization. Also, globalization has increased the interdependency of political, personal, cultural and economic factors.[97]

A 2005 UNESCO report[98] showed that cultural exchange is becoming more frequent from Eastern Asia but Western countries are still the main exporters of cultural goods. In 2002, China was the third largest exporter of cultural goods, after the UK and US. Between 1994 and 2002, both North America's and the European Union's shares of cultural exports declined, while Asia's cultural exports grew to surpass North America. Related factors are the fact that Asia's population and area are several times that of North America. Americanization related to a period of high political American clout and of significant growth of America's shops, markets and object being brought into other countries. So globalization, a much more diversified phenomenon, relates to a multilateral political world and to the increase of objects, markets and so on into each other's countries. The Indian experience particularly reveals the plurality of the impact of cultural globalization (Biswajit Ghosh 2011 'Cultural Changes in the Era of Globalisation’, Journal of Developing Societies, 27 (2): 153-175).

Multilingualism and the emergence of lingua francas

Multilingual speakers outnumber monolingual speakers in the world's population.[99] Multilingualism is becoming a social phenomenon governed by the needs of globalization and cultural openness.[100] Thanks to the ease of access to information facilitated by the Internet, individuals' exposure to multiple languages is getting more and more frequent, and triggering therefore the need to acquire more and more languages.

A lingua franca is a language systematically used to make communication possible between people not sharing a mother tongue, in particular when it is a third language, distinct from both mother tongues.[101]

Today, the most popular second language is English. Some 3.5 billion people have some acquaintance of the language.[102] English is the dominant language on the Internet.[103] About 35% of the world's mail, telexes, and cables are in English. Approximately 40% of the world's radio programs are in English.

Language contact occurs when two or more languages or varieties interact. Multilingualism has likely been common throughout much of human history, and today most people in the world are multilingual.[104] Language contact occurs in a variety of phenomena, including language convergence, borrowing, and relexification. The most common products are pidgins, creoles, code-switching, and mixed languages.

Politics

In general, globalization may ultimately reduce the importance of nation states. Sub-state and supra-state institutions such as the European Union, the WTO, the G8 or the International Criminal Court, replace national functions with international agreement.[105] Some observers attribute the relative decline in US power to globalization, particularly due to the country's high trade deficit. This led to a global power shift towards Asian states, particularly China, which unleashed market forces and achieved tremendous growth rates. As of 2011, China was on track to overtake the United States by 2025.[106]

Increasingly, non-governmental organizations influence public policy across national boundaries, including humanitarian aid and developmental efforts.[107]

As a response to globalization, some countries have embraced isolationist policies. For example, the North Korean government makes it very difficult for foreigners to enter the country and strictly monitors their activities when they do. Aid workers are subject to considerable scrutiny and excluded from places and regions the government does not wish them to enter. Citizens cannot freely leave the country.[108][109]

Media and public opinion

A 2005 study by Peer Fiss and Paul Hirsch found large increase in articles negative towards globalization in the years prior. By 1998, negative articles outpaced positive articles by two to one.[110] In 2008 Greg Ip claimed this rise in opposition to globalization can be explained, at least in part, by economic self-interest.[111] The number of newspaper articles showing negative framing rose from about 10% of the total in 1991 to 55% of the total in 1999. This increase occurred during a period when the total number of articles concerning globalization nearly doubled.[110]

A number of international polls have shown that residents of developing countries tend to view globalization more favorably.[112] The BBC found a growing feeling in developing countries that globalization was proceeding too rapidly. Only a few countries, including Mexico, the countries of Central America, Indonesia, Brazil and Kenya, where a majority felt that globalization is growing too slowly.[113]

Philip Gordon stated that "(as of 2004) a clear majority of Europeans believe that globalization can enrich their lives, while believing the European Union can help them take advantage of globalization's benefits while shielding them from its negative effects."[114] The main opposition consisted of socialists, environmental groups, and nationalists.

Residents of the EU did not appear to feel threatened by globalization in 2004. The EU job market was more stable and workers were less likely to accept wage/benefit cuts. Social spending was much higher than in the US.[115]

In a Danish poll in 2007, 76% responded that globalisation is a good thing.[116]

Fiss, et al., surveyed U.S. opinion in 1993. Their survey showed that in 1993 more than 40% of respondents were unfamiliar with the concept of globalization. When the survey was repeated in 1998, 89% of the respondents had a polarized view of globalization as being either good or bad. At the same time, discourse on globalization, which began in the financial community before shifting to a heated debate between proponents and disenchanted students and workers. Polarization increased dramatically after the establishment of the WTO in 1995; this event and subsequent protests led to a large-scale anti-globalization movement.[110] Initially, college educated workers were likely to support globalization. Less educated workers, who were more likely to compete with immigrants and workers in developing countries, tended to be opponents. The situation changed after the financial crisis of 2007. According to a 1997 poll 58% of college graduates said globalization had been good for the U.S. By 2008 only 33% thought it was good. Respondents with high school education also became more opposed.[111]

According to Takenaka Heizo and Chida Ryokichi, as of 1998 there was a perception in Japan that the economy was "Small and Frail". However Japan was resource poor and used exports to pay for its raw materials. Anxiety over their position caused terms such as internationalization and globalization to enter everyday language. However, Japanese tradition was to be as self-sufficient as possible, particularly in agriculture.[117]

The situation may have changed after the 2007 financial crisis. A 2008 BBC World Public Poll as the crisis began suggested that opposition to globalization in developed countries was increasing. The BBC poll asked whether globalization was growing too rapidly. Agreement was strongest in France, Spain, Japan, South Korea, and Germany. The trend in these countries appears to be stronger than in the United States. The poll also correlated the tendency to view globalization as proceeding too rapidly with a perception of growing economic insecurity and social inequality.[113]

Many in the Third World see globalization as a positive force that lifts countries out of poverty.[118] The opposition typically combined environmental concerns with nationalism. Opponents consider governments as agents of neo-colonialism that are subservient to multinational corporations.[119] Much of this criticism comes from the middle class; the Brookings Institute suggested this was because the middle class perceived upwardly mobile low-income groups to threaten their economic security.[120]

Although many critics blame globalization for a decline of the middle class in industrialized countries, the middle class is growing rapidly in the Third World.[121] Coupled with growing urbanization, this led to increasing disparities in wealth between urban and rural areas.[122] In 2002, in India 70% of the population lived in rural areas and depended directly on natural resources for their livelihood.[119] As a result, mass movements in the countryside at times objected to the process.[123]

Internet

Both a product of globalization as well as a catalyst, the Internet connects computer users around the world. From 2000 to 2009, the number of Internet users globally rose from 394 million to 1.858 billion.[124] By 2010, 22 percent of the world's population had access to computers with 1 billion Google searches every day, 300 million Internet users reading blogs, and 2 billion videos viewed daily on YouTube.[125]

An online community is a virtual community that exists online and whose members enable its existence through taking part in membership ritual. Significant socio-technical change may have resulted from the proliferation of such Internet-based social networks.[126]

Population growth

The world population has experienced continuous growth since the end of the Great Famine and the Black Death in 1350, when it stood at around 370 million.[127] The highest rates of growth – global population increases above 1.8% per year – were seen briefly during the 1950s, and for a longer period during the 1960s and 1970s. The growth rate peaked at 2.2% in 1963, and had declined to 1.1% by 2011. Total annual births were highest in the late 1980s at about 138 million,[128] and are now expected to remain essentially constant at their 2011 level of 134 million, while deaths number 56 million per year, and are expected to increase to 80 million per year by 2040.[129] Current projections show a continued increase in population (but a steady decline in the population growth rate), with the global population expected to reach between 7.5 and 10.5 billion by 2050.[130][131]

With human consumption of seafood having doubled in the last 30 years, seriously depleting multiple seafood fisheries and destroying the marine ecosystem as a result, awareness is prompting steps to be taken to create a more sustainable seafood supply.[132]

The head of the International Food Policy Research Institute, stated in 2008 that the gradual change in diet among newly prosperous populations is the most important factor underpinning the rise in global food prices.[133] From 1950 to 1984, as the Green Revolution transformed agriculture around the world, grain production increased by over 250%.[134] World population has grown by about 4 billion since the beginning of the Green Revolution and without it, there would be greater famine and malnutrition than the UN presently documents (approximately 850 million people suffering from chronic malnutrition in 2005).[135][136]

It is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain food security in a world beset by a confluence of "peak" phenomena, namely peak oil, peak water, peak phosphorus, peak grain and peak fish. Growing populations, falling energy sources and food shortages will create the "perfect storm" by 2030, according to UK chief government scientist John Beddington. He noted that food reserves were at a 50-year low and the world would require 50% more energy, food and water by 2030.[137][138] The world will have to produce 70% more food by 2050 to feed a projected extra 2.3 billion people and as incomes rise according to the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).[139] Social scientists have warned of the possibility that global civilization is due for a period of contraction and economic re-localization, due to the decline in fossil fuels and resulting crisis in transportation and food production.[140][141][142] Helga Vierich predicted that a restoration of sustainable local economic activities based on hunting and gathering, shifting horticulture, and pastoralism.[143]

Health

Global health is the health of populations in a global context and transcends the perspectives and concerns of individual nations.[144] Health problems that transcend national borders or have a global political and economic impact, are often emphasized.[145] It has been defined as 'the area of study, research and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide'.[146] Thus, global health is about worldwide improvement of health, reduction of disparities, and protection against global threats that disregard national borders.[147] The application of these principles to the domain of mental health is called Global Mental Health.[148]

The major international agency for health is the World Health Organization (WHO). Other important agencies with impact on global health activities include UNICEF, World Food Programme (WFP), United Nations University International Institute for Global Health and the World Bank. A major initiative for improved global health is the United Nations Millennium Declaration and the globally endorsed Millennium Development Goals.[149]

International travel has helped to spread some of the deadliest infectious diseases.[150] Modern modes of transportation allow more people and products to travel around the world at a faster pace, but they also open the airways to the transcontinental movement of infectious disease vectors.[151] One example of this occurring is AIDS/HIV.[152] Due to immigration, approximately 500,000 people in the United States are believed to be infected with Chagas disease.[153] In 2006, the tuberculosis (TB) rate among foreign-born persons in the United States was 9.5 times that of U.S.-born persons.[154] Starting in Asia, the Black Death killed at least one-third of Europe's population in the 14th century.[155] Even worse devastation was inflicted on the American supercontinent by European arrivals. 90% of the populations of the civilizations of the "New World" such as the Aztec, Maya, and Inca were killed by small pox brought by European colonization.

Sports

Globalization has continually increased international competition in sports.

The FIFA World Cup is the world's most widely viewed sporting event; an estimated 715.1 million people watched the final match of the 2006 FIFA World Cup held in Germany.[156]

The Ancient Olympic Games were a series of competitions held between representatives of several city-states and kingdoms from Ancient Greece, which featured mainly athletic but also combat and chariot racing events. During the Olympic games all struggles against the participating city-states were postponed until the games were finished.[157] The origin of these Olympics is shrouded in mystery and legend.[158] During the 19th century Olympic Games became a popular event.

Global natural environment

Environmental challenges such as climate change, cross-boundary water and air pollution and over-fishing of the ocean, require trans-national/global solutions. Since factories in developing countries increased global output and experienced less environmental regulation, globalism substantially increased pollution and impact on water resources.[159]

State of the World 2006 report said India and China's high economic growth was not sustainable. The report stated:

- The world's ecological capacity is simply insufficient to satisfy the ambitions of China, India, Japan, Europe and the United States as well as the aspirations of the rest of the world in a sustainable way[160] In a 2006 news story, BBC reported, "...if China and India were to consume as much resources per capita as United States or Japan in 2030 together they would require a full planet Earth to meet their needs.[160] In the longterm these effects can lead to increased conflict over dwindling resources[161] and in the worst case a Malthusian catastrophe.

The advent of global environmental challenges that might be solved with international cooperation include climate change, cross-boundary water and air pollution, over-fishing of the ocean, and the spread of invasive species. Since many factories are built in developing countries with less environmental regulation, globalism and free trade may increase pollution and impact on precious fresh water resources.[159][163]

International foreign investment in developing countries could lead to a "race to the bottom" as countries lower their environmental and resource protection laws to attract foreign capital.[8][164] The reverse of this theory is true, however, when developed countries maintain positive environmental practices, imparting them to countries they are investing in and creating a "race to the top" phenomenon.[8]

The distances are shrinking between continents and countries due to globalization, causing developing and developed countries to find ways to solve problems on a global rather than regional scale. Agencies like the United Nations now must be the global regulators of pollution, whereas before, regional governance was enough.[165] Action has been taken by the United Nations to monitor and reduce atmospheric pollutants through the Kyoto Protocol, the Clean Air Initiative, and studies of air pollution and public policy.[166]

Global traffic, production, and consumption are causing increased global levels of air pollutants. The northern hemisphere is the leading producer of carbon monoxide and sulfur oxides.[167]

Changes in natural capital are beginning to erode the economic logic of one major aspect of economic globalization: an international division of labor and production based on global supply chains.[168] Over time, peak oil and climate change will result in “peak globalization,” measured in terms of decreasing ton-miles of freight transported, particularly across oceans and continents. The economic logic of the comparative advantage of global supply chains will be overcome by both increasing transportation costs and interruptions and delays in the transit of freight.[169]

China and India substantially increased their fossil fuel consumption as their economies switched from subsistence farming to industry and urbanization.[170][171] Chinese oil consumption grew by 8% yearly between 2002 and 2006, doubling from 1996–2006.[172] In 2007, China surpassed the United States as the top emitter of CO

2.[173]

Only 1 percent of the country's 560 million city inhabitants (2007) breathe air deemed safe by the European Union. In effect, this means that developed countries may "outsource" some of the pollution associated with consumption in countries where pollution-intensive industries have been moved.

A major source of deforestation is the logging industry, driven by China and Japan.[175]

Societies utilize forest resources in order to reach a sustainable level of economic development. Historically, forests in earlier developing nations experience "forest transitions", a period of deforestation and reforestation as a surrounding society becomes more developed, industrialized and shift their primary resource extraction to other nations via imports. For nations at the periphery of the globalized system however, there are no others to shift their extraction onto, and forest degradation continues unabated. Forest transitions can have an effect on the hydrology, climate change, and biodiversity of an area by impacting water quality and the accumulation of greenhouse gases through the re-growth of new forest into second and third growth forests.[176][177]

Without more recycling, zinc could be used up by 2037, both indium and hafnium could run out by 2017, and terbium could be gone before 2012.[178]

In 2003, 29% of open sea fisheries were in a state of collapse.[179] The journal Science published a four-year study in November 2006, which predicted that, at prevailing trends, the world would run out of wild-caught seafood in 2048.[180] Conversely, globalisation created a global market for farm-raised fish and seafood, which as of 2009 was providing 38% of global output, potentially reducing fishing pressure.[181]

The global trade in goods depends upon reliable, inexpensive transportation of freight along complex and long-distance supply chains. [182] Global warming and peak oil undermine globalization by their effects on both transportation costs and the reliable movement of freight. Countering the current geographic pattern of comparative advantage with higher transportation costs, climate change and peak oil will thus result in peak globalization, after which the volume of exports will decline as measured by ton-miles of freight.[183]

Global workforce

The global workforce is the international labor pool of immigrant workers or those employed by multinational companies and connected through a global system of networking and production. As of 2005, the global labor pool of those employed by multinational companies consisted of approximately 3 billion workers.[184]

The current global workforce is competitive as ever. Some go as far as to describe it as "A war for talent."[185] This competitiveness is due to specialized jobs becoming available world wide due to communications technology. As workers get more adept at using technology to communicate, they give themselves the options to be employed in an office half way around the world. These newer technologies not only benefit the workers, but companies may now find highly specialized workers that are very skilled with greater ease, as opposed to limiting their search locally.

However, production workers and service workers have been unable to compete directly with much lower-cost workers in developing countries.[186] Low-wage countries gained the low-value-added element of work formerly done in rich countries, while higher-value work remained; for instance, the total number of people employed in manufacturing in the US declined, but value added per worker increased.[187]

In 2011, the United States imported $332 billion worth of crude oil, up 32% from 2010.[188] Chinese success cost jobs in developing countries as well as in the West.[189] From 2000 to 2007, the U.S. lost a total of 3.2 million manufacturing jobs.[190] As of 26 April 2005 "In regional giant South Africa, some 300,000 textile workers have lost their jobs in the past two years due to the influx of Chinese goods".[191]

International migration

Many countries have some form of guest worker program with policies similar to those found in the U.S. that permit U.S. employers to sponsor non-U.S. citizens as laborers for approximately three years, to be deported afterwards if they have not yet obtained a green card.

As of 2009, over 1,000,000 guest workers reside in the U.S.; the largest program, the H-1B visa, has 650,000 workers in the U.S.[193] and the second-largest, the L-1 visa, has 350,000.[194] Many other United States visas exist for guest workers as well, including the H-2A visa, which allows farmers to bring in an unlimited number of agricultural guest workers.

The United States ran a Mexican guest-worker program in the period 1942–1964, known as the Bracero Program.

An article in The New Republic criticized a guest worker program by equating the visiting workers to second-class citizens, who would never be able to gain citizenship and would have less residential rights than Americans.[195]

Migration of educated and skilled workers is called brain drain. For example, the U.S.welcomes many nurses to come work in the country.[196] The brain drain from Europe to the United States means that some 400,000 European science and technology graduates now live in the U.S. and most have no intention to return to Europe.[197] Nearly 14 million immigrants came to the United States from 2000 to 2010.[198]

Immigrants to the United States and their children founded more than 40 percent of the 2010 Fortune 500 companies. They founded seven of the ten most valuable brands in the world.[199][200]

Reverse brain drain is the movement of human capital from a more developed country to a less developed country. It is considered a logical outcome of a calculated strategy where migrants accumulate savings, also known as remittances, and develop skills overseas that can be used in their home country.[201]

Reverse brain drain can occur when scientists, engineers, or other intellectual elites migrate to a less developed country to learn in its universities, perform research, or gain working experience in areas where education and employment opportunities are limited in their home country. These professionals then return to their home country after several years of experience to start a related business, teach in a university, or work for a multi-national in their home country.[202]

A remittance is a transfer of money by a foreign worker to his or her home country. Remittances are playing an increasingly large role in the economies of many countries, contributing to economic growth and to the livelihoods of less prosperous people (though generally not the poorest of the poor). According to World Bank estimates, remittances totaled US$414 billion in 2009, of which US$316 billion went to developing countries that involved 192 million migrant workers.[203] For some individual recipient countries, remittances can be as high as a third of their GDP.[203] As remittance receivers often have a higher propensity to own a bank account, remittances promote access to financial services for the sender and recipient, an essential aspect of leveraging remittances to promote economic development. The top recipients in terms of the share of remittances in GDP included many smaller economies such as Tajikistan (45%), Moldova (38%), and Honduras (25%).[204]

The IOM found more than 200 million migrants around the world in 2008,[205] including illegal immigration.[206][207] Remittance flows to developing countries reached $328 billion in 2008.[208]

A transnational marriage is a marriage between two people from different countries. A variety of special issues arise in marriages between people from different countries, including those related to citizenship and culture, which add complexity and challenges to these kinds of relationships. In an age of increasing globalization, where a growing number of people have ties to networks of people and places across the globe, rather than to a current geographic location, people are increasingly marrying across national boundaries. Transnational marriage is a by-product of the movement and migration of people.

Support and criticism

Reactions to processes contributing to globalization have varied widely with a history as long as extraterritorial contact and trade. Philosophical differences regarding the costs and benefits of such processes give rise to a broad-range of ideologies and social movements. Proponents of economic growth, expansion and development, in general, view globalizing processes as desirable or necessary to the well-being of human society[209] Antagonists view one or more globalizing processes as detrimental to social well-being on a global or local scale;[209] this includes those who question either the social or natural sustainability of long-term and continuous economic expansion, the social structural inequality caused by these processes, and the colonial, Imperialistic, or hegemonic ethnocentrism, cultural assimilation and cultural appropriation that underlie such processes.

As summarized by Noam Chomsky:

The dominant propaganda systems have appropriated the term "globalization" to refer to the specific version of international economic integration that they favor, which privileges the rights of investors and lenders, those of people being incidental. In accord with this usage, those who favor a different form of international integration, which privileges the rights of human beings, become "anti-globalist." This is simply vulgar propaganda, like the term "anti-Soviet" used by the most disgusting commissars to refer to dissidents. It is not only vulgar, but idiotic. Take the World Social Forum [(WSF)], called "anti-globalization" in the propaganda system – which happens to include the media, the educated classes, etc., with rare exceptions. The WSF is a paradigm example of globalization. It is a gathering of huge numbers of people from all over the world, from just about every corner of life one can think of, apart from the extremely narrow highly privileged elites who meet at the competing World Economic Forum, and are called "pro-globalization" by the propaganda system.[210]

Proponents

In general, corporate businesses, particularly in the area of finance, see globalization as a positive force in the world. Many economists cite statistics that seem to support such positive impact. For example, per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth among post-1980 globalizing countries accelerated from 1.4 percent a year in the 1960s and 2.9 percent a year in the 1970s to 3.5 percent in the 1980s and 5.0 percent in the 1990s. This acceleration in growth seems even more remarkable given that the rich countries saw steady declines in growth from a high of 4.7 percent in the 1960s to 2.2 percent in the 1990s. Also, the non-globalizing developing countries seem to fare worse than the globalizers, with the former's annual growth rates falling from highs of 3.3 percent during the 1970s to only 1.4 percent during the 1990s. This rapid growth among the globalizers is not simply due to the strong performances of China and India in the 1980s and 1990s—18 out of the 24 globalizers experienced increases in growth, many of them quite substantial.[211]

Economic liberalism and free trade

Economic liberals generally argue that higher degrees of political and economic freedom in the form of free trade in the developed world are ends in themselves, producing higher levels of overall material wealth. Globalization is seen as the beneficial spread of liberty and capitalism.[212] Jagdish Bhagwati, a former adviser to the U.N. on globalization, holds that, although there are obvious problems with overly rapid development, globalization is a very positive force that lifts countries out of poverty by causing a virtuous economic cycle associated with faster economic growth.[118] Economist Paul Krugman is another staunch supporter of globalization and free trade with a record of disagreeing with many critics of globalization. He argues that many of them lack a basic understanding of comparative advantage and its importance in today's world.[213]

Global democracy

Democratic globalization is a movement towards an institutional system of global democracy that would give world citizens a say in political organizations. This would, in their view, bypass nation-states, corporate oligopolies, ideological Non-governmental organizations (NGO), political cults and mafias. One of its most prolific proponents is the British political thinker David Held. Advocates of democratic globalization argue that economic expansion and development should be the first phase of democratic globalization, which is to be followed by a phase of building global political institutions. Dr. Francesco Stipo, Director of the United States Association of the Club of Rome, advocates unifying nations under a world government, suggesting that it "should reflect the political and economic balances of world nations. A world confederation would not supersede the authority of the State governments but rather complement it, as both the States and the world authority would have power within their sphere of competence".[214] Former Canadian Senator Douglas Roche, O.C., viewed globalization as inevitable and advocated creating institutions such as a directly elected United Nations Parliamentary Assembly to exercise oversight over unelected international bodies.[215]

Global civics

Global civics suggests that civics can be understood, in a global sense, as a social contract between world citizens in the age of interdependence and interaction. The disseminators of the concept define it as the notion that we have certain rights and responsibilities towards each other by the mere fact of being human on Earth.[216] World citizen has a variety of similar meanings, often referring to a person who disapproves of traditional geopolitical divisions derived from national citizenship. An early incarnation of this sentiment can be found in Socrates, who Plutarch quoted as saying: "I am not an Athenian, or a Greek, but a citizen of the world."[217] In an increasingly interdependent world, world citizens need a compass to frame their mindsets and create a shared consciousness and sense of global responsibility in world issues such as environmental problems and nuclear proliferation.[218]

Cosmopolitanism is the notion that all human ethnic groups belong to a single community based on a shared morality. A person who adheres to the idea of cosmopolitanism in any of its forms is called a cosmopolitan or cosmopolite.[219] A cosmopolitan community might be based on an inclusive morality, a shared economic relationship, or a political structure that encompasses different nations. The cosmopolitan community is one in which individuals from different places (e.g. nation-states) form relationships based on mutual respect. For instance, Kwame Anthony Appiah suggests the possibility of a cosmopolitan community in which individuals from varying locations (physical, economic, etc.) enter relationships of mutual respect despite their differing beliefs (religious, political, etc.).[220]

Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan popularized the term Global Village beginning in 1962.[221] His view suggested that globalization would lead to a world where people from all countries will become more integrated and aware of common interests and shared humanity.[222]

Critiques

Critiques of globalization generally stem from discussions surrounding the impact of such processes on the planet as well as the human costs. They challenge directly traditional metrics, such as GDP, and look to other measures, such as the Gini coefficient or the Happy Planet Index,[223][224] and point to a "multitude of interconnected fatal consequences–social disintegration, a breakdown of democracy, more rapid and extensive deterioration of the environment, the spread of new diseases, increasing poverty and alienation"[225] which they claim are the unintended consequences of globalization.

Criticisms have arisen from church groups, national liberation factions, peasant unionists, intellectuals, artists, protectionists, anarchists, those in support of relocalization (e.g., consumption of nearby production) and others. Some have been reformist in nature, (arguing for a more moderate form of capitalism) while others are more revolutionary (power shift from private to public control) or reactionary (public to private).

Some opponents of globalization see the phenomenon as the promotion of corporatist interests.[226] They also claim that the increasing autonomy and strength of corporate entities shapes the political policy of countries.[227][228] They advocate global institutions and policies that they believe better address the moral claims of poor and working classes as well as environmental concerns.[229] Economic arguments by fair trade theorists claim that unrestricted free trade benefits those with more financial leverage (i.e. the rich) at the expense of the poor.[230]

Critics argue that globalization results in:

- Poorer countries suffering disadvantages: While it is true that free trade encourages globalization among countries, some countries try to protect their domestic suppliers. The main export of poorer countries is usually agricultural goods. Larger countries often subsidise their farmers (e.g., the EU's Common Agricultural Policy), which lowers the market price for foreign crops.[231]

- The shift to outsourcing: Globalization allowed corporations to move manufacturing and service jobs from high cost locations, creating economic opportunities with the most competitive wages and worker benefits.[78]

- Weak labor unions: The surplus in cheap labor coupled with an ever growing number of companies in transition weakened labor unions in high-cost areas. Unions lose their effectiveness and workers their enthusiasm for unions when membership begins to decline.[231]

- An increase in exploitation of child labor: Countries with weak protections for children are vulnerable to infestation by rogue companies and criminal gangs who exploit them. Examples include quarrying, salvage, and farm work as well as trafficking, bondage, forced labor, prostitution and pornography.[232]

Helena Norberg-Hodge, the director and founder of ISEC, criticizes globalization in many ways. In her book Ancient Futures, Norberg-Hodge claims that "centuries of ecological balance and social harmony are under threat from the pressures of development and globalization." She also criticizes the standardization and rationalization of globalization, as it does not always yield the expected growth outcomes. Although globalization takes similar steps in most countries, scholars such as Hodge claim that it might not be effective to certain countries, for globalization has actually moved some countries backward instead of developing them.[233]

Anti-globalization movement

Anti-globalization, or counter-globalisation,[234] consists of a number of criticisms of globalization but, in general, is critical of the globalization of corporate capitalism.[235] The movement is also commonly referred to as the alter-globalization movement, anti-globalist movement, anti-corporate globalization movement,[236] or movement against neoliberal globalization. Although British sociologist Paul Q. Hirst and political economist Grahame F. Thompson note the term is vague;[237] "anti-globalization movement" activities may include attempts to demonstrate sovereignty, practice local democratic decision-making, or restrict the international transfer of people, goods and capitalist ideologies, particularly free market deregulation. Canadian author and social activist Naomi Klein argues that the term could denote either a single social movement or encompass multiple social movements such as nationalism and socialism.[238] Bruce Podobnik, a sociologist at Lewis and Clark College, states that "the vast majority of groups that participate in these protests draw on international networks of support, and they generally call for forms of globalization that enhance democratic representation, human rights, and egalitarianism."[239] Economists Joseph Stiglitz and Andrew Charlton write:

The anti-globalization movement developed in opposition to the perceived negative aspects of globalization. The term 'anti-globalization' is in many ways a misnomer, since the group represents a wide range of interests and issues and many of the people involved in the anti-globalization movement do support closer ties between the various peoples and cultures of the world through, for example, aid, assistance for refugees, and global environmental issues.[240]

In general, opponents of globalization in developed countries are disproportionately middle-class and college-educated. This contrasts sharply with the situation in developing countries, where the anti-globalization movement has been more successful in enlisting a broader group, including millions of workers and farmers.[241]

Opposition to capital market integration

Capital markets have to do with raising and investing moneys in various human enterprises. Increasing integration of these financial markets between countries leads to the emergence of a global capital marketplace or a single world market. In the long run, increased movement of capital between countries tends to favor owners of capital more than any other group; in the short run, owners and workers in specific sectors in capital-exporting countries bear much of the burden of adjusting to increased movement of capital.[242] It is not surprising that these conditions lead to political divisions about whether or not to encourage or increase international capital market integration.

Those opposed to capital market integration on the basis of human rights issues are especially disturbed by the various abuses which they think are perpetuated by global and international institutions that, they say, promote neoliberalism without regard to ethical standards. Common targets include the World Bank (WB), International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) and free trade treaties like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), the Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI) and the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). In light of the economic gap between rich and poor countries, movement adherents claim "free trade" without measures in place to protect the under-capitalized will contribute only to the strengthening the power of industrialized nations (often termed the "North" in opposition to the developing world's "South").

Global justice and inequality

The global justice movement is the loose collection of individuals and groups—often referred to as a "movement of movements"—who advocate fair trade rules and perceive current institutions of global economic integration as problems.[243] The movement is often labeled an anti-globalization movement by the mainstream media. Those involved, however, frequently deny that they are anti-globalization, insisting that they support the globalization of communication and people and oppose only the global expansion of corporate power.[244] The movement is based in the idea of social justice, desiring the creation of a society or institution based on the principles of equality and solidarity, the values of human rights, and the dignity of every human being.[245][246][247] Social inequality within and between nations, including a growing global digital divide, is a focal point of the movement.

Anti-consumerism

Anti-consumerism is the socio-political movement against the equating of personal happiness with consumption and the purchase of material possessions. The term "consumerism" was first used in 1915 to refer to "advocacy of the rights and interests of consumers" (Oxford English Dictionary), but here the term "consumerism" refers to the sense first used in 1960, "emphasis on or preoccupation with the acquisition of consumer goods" (Oxford English Dictionary). Concern over the treatment of consumers has spawned substantial activism, and the incorporation of consumer education into school curricula. Anti-consumerist activism draws parallels with environmental activism, anti-globalization, and animal-rights activism in its condemnation of modern corporations, or organizations that pursue a solely economic interest. One variation on this topic is activism by postconsumers, with the strategic emphasis on moving beyond addictive consumerism.[5]

In recent years, there have been an increasing number of books (Naomi Klein's 2000 No Logo for example) and films (e.g. The Corporation & Surplus), popularizing an anti-corporate ideology to the public.

Opposition to economic materialism comes primarily from two sources: religion and social activism. Some religions assert materialism interferes with connection between the individual and the divine, or that it is inherently an immoral lifestyle. Social activists believe materialism is connected to global retail merchandizing and supplier convergence, war, greed, anomie, crime, environmental degradation, and general social malaise and discontent.

Anti-global governance