Iranian peoples

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Iran and Iranian Plateau, Anatolia, north-western South Asia, Mesopotamia, Central Asia, the Caucasus and as immigrant communities in North America and Western Europe. | |

| Languages | |

| Iranian languages, a branch of the Indo-European family | |

| Religion | |

| Majority Sunni Islam (including Sufis), Shia Islam, Irreligion, Agnosticism, Christianity (Orthodox Christianity,[1] Protestantism, Catholicism and Georgian Orthodox), Atheism, Zoroastrianism, Nestorians, Judaism, Bahá'í, Paganism, Yazidi |

The Iranian peoples[5] or Iranic peoples[6][7][8] are a diverse Indo-European ethno-linguistic group that comprise the speakers of Iranian languages.[9][10]

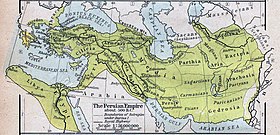

Proto-Iranians are believed to have emerged as a separate branch of the Indo-Iranians in Central Asia in the mid 2nd millennium BC.[11][12] At their peak of expansion in the mid 1st millennium BC, the territory of the Iranian peoples stretched across the Iranian Plateau and the entire Eurasian Steppe from the Great Hungarian Plain in the west to the Ordos Plateau in the east.[13] The Western Iranian Persian Empires came to dominate much of the ancient world at this time, leaving an important cultural legacy, while the Eastern Iranian nomads of the steppe played a decisive role in the development of Eurasian nomadism and the Silk Route.[11] Ancient Iranian peoples include the Alans, Bactrians, Dahae, Massagetae, Medes, Khwarezmians, Parthians, Saka, Sarmatians, Scythians, Sogdians and other peoples of Central Asia, the Caucasus, Eastern Europe, and the Iranian Plateau.

In the 1st millennium AD their area of settlement was reduced as a result of Slavic, Germanic, Turkic and Mongol expansions and many being subjected to Slavicisation.[14][15][16][17] The Iranian peoples include Balochs, Kurds, Gilaks, Lurs, Mazanderanis, Ossetians, Pashtuns, Pamiris, Persians, Tajiks, Talysh people, Wakhis and Yaghnobis. Their current distribution spreads across the Iranian plateau, and stretches from the Caucasus in the north to the Persian Gulf in the south, and from Xinjiang in the east to eastern Turkey in the west[18] – a region that is sometimes called the "Iranian cultural continent", and represents the extent of the Iranian languages and significant influence of the Iranian peoples, through the geopolitical reach of the "Greater Iran".[19]

Name

The term Iranian is derived from the Old Iranian ethnical adjective Aryana which is itself a cognate of the Sanskrit word Arya.[20][21] The name Iran is from Aryānām; lit: "(Land) of the Aryans".[22][23] The old Proto-Indo-Iranian term Arya, per Thieme meaning "hospitable", is believed to have been one of the self-referential terms used by the Aryans, at least in the areas populated by Aryans who migrated south from Central Asia. Another meaning for Aryan is "noble". In the late part of the Avesta (Vendidad 1), one of their homelands was referred to as Airyanem Vaejah. The homeland varied in its geographic range, the area around Herat (Pliny's view) and even the entire expanse of the Iranian plateau (Strabo's designation).[23]

The academic usage of the term Iranian is distinct from the state of Iran and its various citizens (who are all Iranian by nationality and thus popularly referred to as Iranians) in the same way that Germanic peoples is distinct from Germans. Many citizens of Iran are not necessarily "Iranian peoples" by virtue of not being speakers of Iranian languages. Unlike the various terms connected with the Aryan arya- in Old Indian, the Old Iranian term has solely an ethnic meaning[24] and there can be no doubt about the ethnic value of Old Iran. arya (Benveniste, 1969, I, pp. 369 f.; Szemerényi; Kellens).[25]

The name Arya lives in the ethnic names like Alan, New Persian: Iran, Ossetian: Ir and Iron.[25][26][27][28][28][29][30][31] The name Iran has been in usage since Sassanid times.[29][30]

The Avesta clearly uses "airya" as an ethnic name (Vd. 1; Yt. 13.143-44, etc.), where it appears in expressions such as airyāfi; daiŋˊhāvō "Iranian lands, peoples," airyō.šayanəm "land inhabited by Iranians," and airyanəm vaējō vaŋhuyāfi; dāityayāfi; "Iranian stretch of the good Dāityā," the river Oxus, the modern Āmū Daryā.[25]

The term "Ariya" appears in the royal Old Persian inscriptions in three different contexts: 1) As the name of the language of the Old Persian version of the inscription of Darius the Great in Behistun; 2) as the ethnic background of Darius in inscriptions at Naqsh-e-Rostam and Susa (Dna, Dse) and Xerxes in the inscription from Persepolis (Xph) and 3) as the definition of the God of Iranian peoples, Ahuramazda, in the Elamite version of the Behistun inscription.[25][26][28] For example, in the Dna and Dse Darius and Xerxes describe themselves as "An Achaemenian, A Persian son of a Persian and an Aryan, of Aryan stock".[32] Although Darius the Great called his language the Iranian language,[32] modern scholars refer to it as Old Persian[32] because it is the ancestor of modern Persian language.[33]

The Old Persian and Avestan evidence is confirmed by the Greek sources".[25] Herodotus in his Histories remarks about the Iranian Medes that: "These Medes were called anciently by all people Arians; " (7.62).[25][26][28] In Armenian sources, the Parthians, Medes and Persians are collectively referred to as Iranians.[34] Eudemus of Rhodes apud Damascius (Dubitationes et solutiones in Platonis Parmenidem 125 bis) refers to "the Magi and all those of Iranian (áreion) lineage"; Diodorus Siculus (1.94.2) considers Zoroaster (Zathraustēs) as one of the Arianoi.[25]

Strabo, in his "Geography", mentions the unity of Medes, Persians, Bactrians and Sogdians:[27]

The name of Ariana is further extended to a part of Persia and of Media, as also to the Bactrians and Sogdians on the north; for these speak approximately the same language, with but slight variations.

— Geography, 15.8

The trilingual inscription erected by Shapur's command gives a more clear description. The languages used are Parthian, Middle Persian and Greek. In Greek, the inscription says: "ego ... tou Arianon ethnous despotes eimi"("I am lord of the kingdom (Gk. nation) of the Aryans") which translates to "I am the king of the Iranian people". In the Middle Persian, Shapour states: "ērānšahr xwadāy hēm" and in Parthian he states: "aryānšahr xwadāy ahēm".[29][35]

The Bactrian language (a Middle Iranian language) inscription of Kanishka the founder of the Kushan empire at Rabatak, which was discovered in 1993 in an unexcavated site in the Afghanistan province of Baghlan, clearly refers to this Eastern Iranian language as Arya.[36][37] In the post-Islamic era, one can still see a clear usage of the term Iran in the work of the 10th-century historian Hamzeh Isfahani. In his book the history of Prophets and Kings writes: "Aryan which is also called Pars (Persia) is in the middle of these countries and these six countries surround it because the South East is in the hands China, the North of the Turks, the middle South is India, the middle North is Rome, and the South West and the North West is the Sudan and Berber lands".[38] All this evidence shows that the name arya "Iranian" was a collective definition, denoting peoples (Geiger, pp. 167 f.; Schmitt, 1978, p. 31) who were aware of belonging to the one ethnic stock, speaking a common language, and having a religious tradition that centered on the cult of Ahura Mazdā.[39]

History and settlement

Roots

The language referred to as Proto-Indo-European (PIE): is ancestral to the Celtic, Italic (including Romance), Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, Indo-Iranian, Albanian, Armenian, Greek, and Tocharian languages.

'There is an agreement that the PIE community split into two major groups from wherever its homeland was situated (its location is unknown), and whenever the timing of its dispersal (also unknown). One headed west for Europe and became speakers of Indo-European (all the languages of modern Europe save for Basque, Hungarian, Estonian, and Finnish) while others headed east for Eurasia to become Indo-Iranians. The Indo-Iranians were a community that spoke a common language prior to their branching off into the Iranian and Indo-Aryan languages. Iranian refers to the languages of Iran (Iranian), parts of Pakistan (Balochi and Pashto), Afghanistan (Pashto and Dari), and Tadjikistan (Tajiki) and Indo-Aryan, Sanskrit, Urdu and its many related languages.' – (Carl C. Lamberg-Karlovsky: Case of the Bronze Age)

The division into an "Eastern" and a "Western" group by the early 1st millennium is visible in Avestan vs. Old Persian, the two oldest known Iranian languages. The Old Avestan texts known as the Gathas are believed to have been composed by Zoroaster, the founder of Zoroastrianism, with the Yaz culture (c. 1500 BCE – 1100 BCE) as a candidate for the development of Eastern Iranian culture.

The Iranians had domesticated horses, had traveled far and wide, and from the late 2nd millennium BCE to early 1st millennium BCE they had expanded from the Eurasian Steppe and settled on the Iranian Plateau.[40][41]

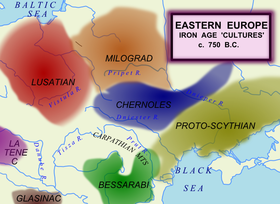

By the early 1st millennium, Ancient Iranian peoples such as Medes, Persians, Bactrians, and Parthians populated the Iranian plateau, and other Scythian tribes, along with Cimmerians, Sarmatians and Alans populated the steppes north of the Black Sea. The Scythian and Sarmatian tribes would quickly spread as far west as the Great Hungarian Plain, while mainly settling in Ukraine, Southern European Russia, and the Balkans,[42][43][44] while other Scythian tribes, such as the Saka, spread as far east as Xinjiang, China. Scythians as well formed the Indo-Scythian Empire, and Bactrians formed a Greco-Bactrian Kingdom founded by Diodotus I, the satrap of Bactria. The Kushan Empire, with Bactrian roots/connections, once controlled much of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. The Kushan elite (who the Chinese called the Yuezhi) were either a Tocharian-speaking (another Indo-European branch) people or an Eastern Iranian language-speaking people.

With numerous artistic, scientific, architectural and philosophical achievements and numerous kingdoms and empires that bridged much of the civilized world in antiquity, the Iranian peoples were often in close contact with the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, Indians, Armenians, Peoples of the Caucasus, Chinese, Turks and Arabs. The various religions of the Iranian people, including Zoroastrianism, Mithraism and Manichaeism, are believed by some scholars to have been significant early philosophical influences on Christianity and Judaism.[45]

Western Iranian peoples

During the 1st centuries of the 1st millennium BCE, the ancient Persians established themselves in the western portion of the Iranian plateau and appear to have interacted considerably with the Elamites and Babylonians, while the Medes also entered in contact with the Assyrians.[46] Remnants of the Median language and Old Persian show their common Proto-Iranian roots, emphasized in Strabo and Herodotus' description of their languages as very similar to the languages spoken by the Bactrians and Soghdians in the east.[23][47] Following the establishment of the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian language (referred to as "Farsi" in Persian) spread from Pars or Fars Province to various regions of the Empire, with the modern dialects of Iran, Afghanistan (also known as Dari) and Central-Asia (known as Tajiki) descending from Old Persian.

At first, the Western Iranian peoples in the Near East were absolutely dominated by the various Assyrian empires. An alliance with the Medes, Persians, and rebelling Babylonians, Scythians, Chaldeans, and Cimmerians, helped the Medes to capture Nineveh in 612 BCE, which resulted in the eventual collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire by 605 BC.[48] The Medes were subsequently able to establish their Median kingdom (with Ecbatana as their royal centre) beyond their original homeland and had eventually a territory stretching roughly from northeastern Iran to the Halys River in Anatolia. After the fall of the Assyrian Empire, between 616 BCE and 605 BCE, a unified Median state was formed, which, together with Babylonia, Lydia, and Egypt, became one of the four major powers of the ancient Near East

Later on, in 550 BC, Cyrus the Great, would overthrow the leading Median rule, and conquer Kingdom of Lydia and the Babylonian Empire after which he established the Achaemenid Empire (or the First Persian Empire), while his successors would dramatically extent its borders. At its greatest extent, the Achaemenid Empire would encompass swaths of territory across three continents, namely Europe, Africa and Asia, stretching from the Balkans and Eastern Europe proper in the west, to the Indus Valley in the east. The largest empire of ancient history, with their base in Persis (although the main capital was located in Babylon) the Achaemenids would rule much of the known ancient world for centuries. This First Persian Empire was equally notable for its successful model of a centralised, bureaucratic administration (through satraps under a king) and a government working to the profit of its subjects, for building infrastructure such as a postal system and road systems and the use of an official language across its territories and a large professional army and civil services (inspiring similar systems in later empires),[49] and for emancipation of slaves including the Jewish exiles in Babylon, and is noted in Western history as the antagonist of the Greek city states during the Greco-Persian Wars. The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was built in the empire as well.

The Greco-Persian Wars resulted in the Persians being forced to withdraw from their European territories, setting the direct further course of history of Greece and the rest of Europe. More than a century later, a prince of Macedon (which itself was a subject to Persia from the late 6th century BC up to the First Persian invasion of Greece) later known by the name of Alexander the Great, overthrew the incumbent Persian king, by which the Achaemenid Empire was ended.

Old Persian is attested in the Behistun Inscription (c. 519 BCE), recording a proclamation by Darius the Great.[50] In southwestern Iran, the Achaemenid kings usually wrote their inscriptions in trilingual form (Elamite, Babylonian and Old Persian)[51] while elsewhere other languages were used. The administrative languages were Elamite in the early period, and later Imperial Aramaic,[52] as well as Greek, making it a widely used bureaucratic language.[53] Even though the Achaemenids had extensive contacts with the Greeks and vice versa, and had conquered many of the Greek-speaking area's both in Europe and Asia Minor during different periods of the empire, the native Old Iranian sources provide no indication of Greek linguistic evidence.[53] However, there is plenty of evidence (in addition to the accounts of Herodotus) that Greeks, apart from being deployed and employed in the core regions of the empire, also evidently lived and worked in the heartland of the Achaemenid Empire, namely Iran.[53] For example, Greeks were part of the various ethnicities that constructed Darius' palace in Susa, apart from the Greek inscriptions found nearby there, and one short Persepolis tablet written in Greek.[53]

The early inhabitants of the Achaemenid Empire appear to have adopted the religion of Zoroastrianism.[54] The Baloch who speak a west Iranian language relate an oral tradition regarding their migration from Aleppo, Syria around the year 1000 CE, whereas linguistic evidence links Balochi to Kurmanji, Soranî, Gorani and Zazaki language.[55]

Eastern Iranian peoples

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

While the Iranian tribes of the south are better known through their texts and modern counterparts, the tribes which remained largely in the vast Eurasian expanse are known through the references made to them by the ancient Greeks, Persians, Chinese, and Indo-Aryans as well as by archaeological finds. The Greek chronicler, Herodotus (5th century BCE) makes references to a nomadic people, the Scythians; he describes them as having dwelt in what is today southern European Russia and Ukraine. He was the first to make a reference to them. Many ancient Sanskrit texts from a later period make references to such tribes they were witness of pointing them towards the southeastern-most edges of Central Asia, around the Hindukush range in northern Pakistan.

It is believed that these Scythians were conquered by their eastern cousins, the Sarmatians, who are mentioned by Strabo as the dominant tribe which controlled the southern Russian steppe in the 1st millennium CE. These Sarmatians were also known to the Romans, who conquered the western tribes in the Balkans and sent Sarmatian conscripts, as part of Roman legions, as far west as Roman Britain. These Iranian-speaking Scythians and Sarmatians dominated large parts of Eastern Europe for a millennium, and were eventually absorbed and assimilated (e.g. Slavicisation) by the Proto-Slavic population of the region.[14][15][17]

The Sarmatians differed from the Scythians in their veneration of the god of fire rather than god of nature, and women's prominent role in warfare, which possibly served as the inspiration for the Amazons.[56] At their greatest reported extent, around 1st century AD, these tribes ranged from the Vistula River to the mouth of the Danube and eastward to the Volga, bordering the shores of the Black and Caspian Seas as well as the Caucasus to the south.[57] Their territory, which was known as Sarmatia to Greco-Roman ethnographers, corresponded to the western part of greater Scythia (mostly modern Ukraine and Southern Russia, also to a smaller extent north eastern Balkans around Moldova). According to authors Arrowsmith, Fellowes and Graves Hansard in their book A Grammar of Ancient Geography published in 1832, Sarmatia had two parts, Sarmatia Europea [58] and Sarmatia Asiatica [59] covering a combined area of 503,000 sq mi or 1,302,764 km2.

Throughout the first millennium AD, the large presence of the Sarmatians who once dominated Ukraine, Southern European Russia, and swaths of the Balkans, gradually started to diminish mainly due to assimilation and absorption by the Germanic Goths, especially from the areas near the Roman frontier, but only completely and climactically by the (Proto-Slavic peoples. The abundant East Iranian-derived toponyms in Eastern Europe proper (e.g. some of the largest rivers; the Dniestr and Dniepr) and the Balkans, as well as loanwords adopted predominantly through the Eastern Slavic languages and adopted aspects of Iranian culture amongst the early Slavs, are all a remnant of this. A connection between Proto-Slavonic and Iranian languages is also furthermore proven by the earliest layer of loanwords in the former.[60] For instance, the Proto-Slavonic words for god (*bogъ), demon (*divъ), house (*xata), axe (*toporъ) and dog (*sobaka) are of Scythian origin.[61]

A further point on behalf of the extensive contact between these Scytho-Sarmatian Iranian tribes in Eastern Europe and the (Early) Slavs is to be shown in matters regarding religion. After Slavic and Baltic languages diverged –- also evidenced by etymology –- the Early Slavs interacted with Iranian peoples and merged elements of Iranian spirituality into their beliefs. For example, both Early Iranian and Slavic supreme gods were considered givers of wealth, unlike the supreme thunder gods in many other European religions. Also, both Slavs and Iranians had demons –- given names from similar linguistic roots, Daêva (Iranian) and Divŭ (Slavic) –- and a concept of dualism, of good and evil.[62]

The Sarmatians of the east, based in the North Caucasus, became the Alans, who also ventured far and wide, with a branch ending up in Western Europe and North Africa, as they accompanied the Germanic Vandals during their migrations. The modern Ossetians are believed to be the sole direct descendants of the Alans, as other remnants of the Alans disappeared following Germanic, Hunnic and ultimately Slavic migrations and invasions.[63] Another group of Alans allied with Goths to defeat the Romans and ultimately settled in what is now called Catalonia (Goth-Alania).[64]

Some of the Saka-Scythian tribes in Central Asia would later move further southeast and invade the Iranian plateau, large sections of present-day Afghanistan and finally deep into present day Pakistan (see Indo-Scythians). Another Iranian tribe related to the Saka-Scythians were the Parni in Central Asia, and who later become indistinguishable from the Parthians, speakers of a northwest-Iranian language. Many Iranian tribes, including the Khwarazmians, Massagetae and Sogdians, were assimilated and/or displaced in Central Asia by the migrations of Turkic tribes emanating out of Xinjiang and Siberia.[65]

The most dominant surviving Eastern Iranian peoples are represented by the Pashtuns, whose origins are generally believed to be from the province of Ghor,[citation needed] from which they began to spread until they reached as far west as Herat, north to areas of southern and eastern Afghanistan;[citation needed] and as eastward towards the Indus. The Pashto language shows affinities to the Avestan and Bactrian[citation needed].

The modern Sarikoli in southern Xinjiang and the Ossetians of the Caucasus (mainly South Ossetia and North Ossetia) are remnants of the various Scythian-derived tribes from the vast far and wide territory they once dwelled in. The modern Ossetians are the descendants of the Alano-Sarmatians,[66][67] and their claims are supported by their Northeast Iranian language, while culturally the Ossetians resemble their North Caucasian neighbors, the Kabardians and Circassians.[63][68] Various extinct Iranian peoples existed in the eastern Caucasus, including the Azaris, while some Iranian peoples remain in the region, including the Talysh[69] and the Tats[70] (including the Judeo-Tats,[71] who have relocated to Israel), found in Azerbaijan and as far north as the Russian republic of Dagestan. A remnant of the Sogdians is found in the Yaghnobi-speaking population in parts of the Zeravshan valley in Tajikistan.

Later developments

Starting with the reign of Omar in 634 CE, Muslim Arabs began a conquest of the Iranian plateau. The Arabs conquered the Sassanid Empire of the Persians and seized much of the Byzantine Empire populated by the Kurds and others. Ultimately, the various Iranian peoples, including the Persians, Pashtuns, Kurds and Balochis, converted to Islam, while the Alans converted to Christianity, thus laying the foundation for the fact that the modern-day Ossetians are Christian. The Iranian peoples would later split along sectarian lines as the Persians (and later the Hazara) adopted the Shi'a sect. As ancient tribes and identities changed, so did the Iranian peoples, many of whom assimilated foreign cultures and peoples.[72]

Later, during the 2nd millennium CE, the Iranian peoples would play a prominent role during the age of Islamic expansion and empire. Saladin, a noted adversary of the Crusaders, was an ethnic Kurd, while various empires centered in Iran (including the Safavids) re-established a modern dialect of Persian as the official language spoken throughout much of what is today Iran and the Caucasus. Iranian influence spread to the neighbouring Ottoman Empire, where Persian was often spoken at court (though a heavy Turko-Persian basis there was set already by the predecessors of the Ottomans in Anatolia, namely the Seljuks and the Sultanate of Rum amongst others) as well to the court of the Mughal Empire. All of the major Iranian peoples reasserted their use of Iranian languages following the decline of Arab rule, but would not begin to form modern national identities until the 19th and early 20th centuries (just as Germans and Italians were beginning to formulate national identities of their own).

Demographics

There are an estimated 150 to 200 million native speakers of Iranian languages, the five major groups of Persians, Lurs, Kurds, Baloch, and Pashtuns accounting for about 90% of this number.[73] Currently, most of these Iranian peoples live in Iran, Afghanistan, the Caucasus (mainly Ossetia, other parts of Georgia, Dagestan, and Azerbaijan), Iraqi Kurdistan and Kurdish majority populated areas of Turkey, Iran and Syria, Tajikistan, Pakistan and Uzbekistan. There are also Iranian peoples living in Eastern Arabia such as northern Oman and Bahrain.

Due to recent migrations, there are also large communities of speakers of Iranian languages in Europe, the Americas, and Israel.

The following is a list of peoples that speak Iranian languages with the respective groups's core areas of settlements and their estimated sizes (in millions):

| People | region | population |

|---|---|---|

| Persian-speaking peoples | Iran, the Caucasus, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, Pakistan | 72–85 |

| Pashtuns | Afghanistan, Pakistan | 35–50 |

| Kurds | Turkey, Iran, Iraqi Kurdistan, Syria, Armenia, İsrael, Lebanon | 40–45 |

| Baluchis | Pakistan, Iran, Oman,[3] Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, UAE | 20–30 |

| Gilakis and Mazanderanis | Iran | 5–10 |

| Lurs and Bakhtiaris | Iran, Kuwait, and Oman[77] | 6 |

| Laks[74] | Iran | |

| Pamiri people | Tajikistan, Afghanistan, China (Xinjiang), Pakistan | 0.9 |

| Talysh | Azerbaijan, Iran | 1.5 |

| Ossetians | South Ossetia, Georgia, Russia (North Ossetia), Hungary |

0.7 |

| Yaghnobi | Uzbekistan and Tajikistan (Zerafshan region) | 0.025 |

| Kumzari | Oman (Musandam) | 0.021 |

| Zoroastrian

|

India |

Culture

Like other Indo-Europeans, the early Iranians practiced ritual sacrifice, had a social hierarchy consisting of warriors, clerics and farmers and poetic hymns and sagas to recount their deeds.[78]

Following the Iranian split from the Indo-Iranians, the Iranians developed an increasingly distinct culture. Various common traits can be discerned among the Iranian peoples. For example, the social event Norouz is an Iranian festival that is practiced by nearly all of the Iranian peoples as well as others in the region. Its origins are traced to Zoroastrianism and pre-historic times.

Some Iranian cultures exhibit traits that are unique unto themselves. The Pashtuns adhere to a code of honor and culture known as Pashtunwali, which has a similar counterpart among the Baloch, called Mayar, that is more hierarchical.[79]

Religion

The early Iranian peoples worshipped various deities of found throughout Proto-Indo-Iranian religion where Indo-European immigrants established themselves.[80] The earliest major religion of the Iranian peoples was Zoroastrianism, which spread to nearly all of the Iranian peoples living in the Iranian plateau. Other religions that had their origins in the Iranian world were Mithraism, Manichaeism, and Mazdakism, among others.

Modern speakers of Iranian languages mainly follow Islam. Some follow Judaism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and the Bahá'í Faith, with an unknown number showing no religious affiliation. Overall the numbers of Sunni and Shia among the Iranian peoples are equally distributed. Most Kurds, Tajiks, Pashtuns, and Baloch are Sunni Muslims, while the remainder are mainly Twelver Shi'a, comprising mostly Persians in Iran, and Hazaras in Afghanistan. Zazas in Turkey are largely Alevi, while the Pamiri peoples in Tajikistan and China are nearly all Ismaili. The Christian community is mainly represented by the Armenian Apostolic Church, followed by the Russian Orthodox and Georgian Orthodox Ossetians followed by Nestorians. Judaism is followed mainly by Persian Jews, Kurdish Jews, Bukharian Jews (of Central Asia) and the Mountain Jews (of the Caucasus), most of whom are now found in Israel. The historical religion of the Persian Empire was Zoroastrianism and it still has a few thousand followers, mostly in Yazd and Kerman. They are known as the Parsis in the Indian subcontinent, where many of them fled in historic times following the Arab conquest of Persia, or Zoroastrians in Iran. Another ancient religion is the Yazidi faith, followed by some Kurds in northern Iraq, as well as the majority of the Kurds in Armenia.

Elements of pre-Islamic Zoroastrian and Paganistic beliefs persist among some Islamized groups today, such as the Tajiks, Pashtuns, Pamiri peoples and Ossetians.

Cultural assimilation

In matters relating to culture, the various Turkic-speaking ethnic groups of Iran (notably the Azerbaijani people) and Afghanistan (Uzbeks and Turkmen) are often conversant in Iranian languages, in addition to their own Turkic languages and also have Iranian culture to the extent that the term Turko-Iranian can be applied.[81] The usage applies to various circumstances that involve historic interaction, intermarriage, cultural assimilation, bilingualism and cultural overlap or commonalities.

Notable among this synthesis of Turko-Iranian culture are the Azeris, whose culture, religion and significant periods of history are linked to the Persians.[82] Certain theories and genetic tests[83] suggest that the Azeris are genetically more Iranian than Turkic.

The following either partially descend from Iranian peoples or are sometimes regarded as possible descendants of ancient Iranian peoples:

- Turkic-speakers:

- Azeris: Although Azeris speak a Turkic language (modern Azerbaijani language), they are believed to be primarily descendants of ancient Iranians.[84][85][86][87][88] Thus, due to their historical ties with various ancient Iranians, as well as their cultural ties to Persians,[89] the Azeris are often associated with the Iranian peoples (see Origin of Azerbaijani people and the Iranian theory regarding the origin of the Azerbaijanis for more details).[90]

- Turkmens: The Turkmen people are believed to be a mix of Iranian and Turkic ancestry. Genetic studies on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) restriction polymorphism confirmed that Turkmen were characterized by the presence of local Iranian mtDNA lineages, similar to the Eastern Iranian populations, but high male Mongoloid genetic component observed in Turkmens and Hazara in east Iran and Afghanistan with the frequencies of about 20%. This most likely indicates an ancestral combination of Iranian groups and Mongol that the modern Turkmen have inherited and which appears to correspond to the historical record which indicates that various Iranian tribes existed in the region prior to the migration of Turkic tribes who are believed to have merged with the local population and imparted their language and created something of a hybrid Turko-Iranian culture.[91]

- Uzbeks: The modern Uzbek people are believed to have both Iranian and Turkic ancestry. "Uzbek" and "Tajik" are modern designations given to the culturally homogeneous, sedentary population of Central Asia. The local ancestors of both groups – the Turkic-speaking Uzbeks and the Iranian-speaking Tajiks – were known as "Sarts" ("sedentary merchants") prior to the Russian conquest of Central Asia, while "Uzbek" or "Turk" were the names given to the nomadic and semi-nomadic populations of the area. Still today, modern Uzbeks and Tajiks are known as "Sarts" to their Turkic neighbours, the Kazakhs and the Kyrgyz. The ancient Soghdians and Bactrians are among their ancestors. Culturally, the Uzbeks are closer to their sedentary Iranian-speaking neighbours rather than to their nomadic and semi-nomadic Turkic neighbours. Some Uzbek scholars, i.e. Ahmadov and Askarov, favour the Iranian origin theory.[92]

- Uyghurs: Some Uyghurs are descendants of the Saka people in Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan.

- Slavic-speakers:

- Linguists suggest that the names of the South Slavic peoples, the Serbs and Croats, are of Iranian origin. Those who entertain such a connection propose that the Sarmatian Serboi and alleged Horoathos tribes might have migrated from the Eurasian steppe lands to Eastern and Central Europe, and assimilated with the numerically superior Slavs, passing on their name. Iranian-speaking peoples did inhabit parts of the Balkans in late classical times, and would have been encountered by the Slavs. However, direct linguistic, historical or archaeological proof for such a theory is lacking. (See also: Origin hypotheses of the Serbs and Origin hypotheses of the Croats)

- Indo-Aryan speakers

- Speakers of Indo-Aryan languages share linguistic affinities with speakers of Iranian languages, which suggests a degree of historical interaction between these two groups.

- Swahili-speakers:

- Shirazis: The Shirazi are a sub-group of the Swahili people living on the Swahili Coast of East Africa, especially on the islands of Zanzibar, Pemba and Comoros.[93] Local traditions about their origin claim they are descended from merchant princes from Shiraz in Persia who settled along the Swahili Coast.

Genetics

Regueiro et al (2006)[94] and Grugni et al (2012)[95] have performed large-scale sampling of different ethnic groups within Iran. They found that the most common Haplogroups were:

- J1-M267; typical of Arabian populations, was rarely over 10% in Iranian groups, but as high as 30% in Assyrian minorities of Iran.

- J2-M172: is the most common Hg in Iran (~23%); almost exclusively represented by J2a-M410 subclade (93%), the other major sub-clade being J2b-M12. Apart from Iranians, J2 is common in Mediterranean and Balkan peoples (Serbs, Greeks, Albanians, Italians, Turks), in the Caucasus (Armenians, Georgia, northeastern Turkey, Kurds, Persians); whilst its frequency drops suddenly beyond Afghanistan, Pakistan and northern India.[96] In Europe, J2a is more common in the southern Greece and southern Italy; whilst J2b (J2-M12) is more common in Thessaly, Macedonia and central – northern Italy. Thus J2a and its subgroups within it have a wide distribution from Italy to India, whilst J2b is mostly confined to the Balkans and Italy,[97] being rare even in Turkey. Whilst closely linked with Anatolia and the Levant; and putative agricultural expansions, the distribution of the various sub-clades of J2 likely represents a number of migrational histories which require further elucidation.[96][98]

- R1a-M198: is common in Iran, more so in the east and south rather than the west and north; suggesting a migration toward the south to India then a secondary westward spread across Iran.[99] Whilst the Grongi and Regueiro studies did not define exactly which sub-clades Iranian R1a haplogrouops belong to, private genealogy tests suggest that they virtually all belong to "Eurasian" R1a-Z93.[1] Indeed, population studies of neighbouring Indian groups found that they all were in R1a-Z93.[100] This implies that R1a in Iran did not descend from "European" R1a, or vice versa. Rather, both groups are collateral, sister branches which descend from a parental group hypothesized to have initially lived somewhere between central Asia and Eastern Europe.[101]

- R1b – M269: is widespread from Ireland to Iran, and is common in highland West Asian populations such as Armenians,Turks and Iranians – with an average frequency of 8.5%. Iranian R1b belongs to the L-23 subclade,[102] which is an older than the derivative subclade (R1b-M412) which is most common in western Europe.[103]

- Haplogroup G and subclades: most concentrated in the southern Caucasus,[104] it is present in 10% of Iranians.[105]

- Haplogroup E and various subclades are markers of various northern and eastern African populations. They are present in less than 10% of Iranians (see Afro-Iranians).

Two large – scale papers by Haber (2012)[106] and Di Cristofaro (2013)[107] analyzed populations from Afghanistan, where several Iranian-speaking groups are native. They found that different groups (e.g. Baluch, Hazara, Pashtun) were quite diverse, yet overall:

- R1a (subclade not further analyzed) was the predominant haplogroup, especially amongst Pashtuns and Tajiks.

- The presence of "east Eurasian" haplogroup C3, especially in Hazaras (33-40%), in part linked to Mongol expansions into the region..

- The presence of haplogroup J2, like in Iran, of 5–20%.

- A relative paucity of "Indian" haplgroup H (< 10%).

Internal diversity and distant affinities

Overall, Iranian-speaking populations are characterized by high internal diversity. For Afghanistan, "It is possibly due to the strategic location of this region and its unique harsh geography of mountains, deserts and steppes, which could have facilitated the establishment of social organizations within expanding populations, and helped maintaining genetic boundaries among groups that have developed over time into distinct ethnicities" as well as the "high level of endogamy practiced by these groups".[108] The data ultimately suggests that Afghanistan, like other northern-central Asian regions, has continually been the recipient rather than a source of gene flow. Although, populations from Iran proper are also diverse, J2a-M530 likely spread out of Iran, and constitutes a common genetic substratum for all Iranian populations, which was then modified by further differential gene flows.[105] In Iran, language was a greater determinant of genetic similarity between different groups,[109] whereas in Afghanistan and other areas of northern central Asia, this was not the case.[110]

Overall in Iran, native population groups do not form tight clusters either according to language or region. Rather, they occupy intermediate positions among Near Eastern and Caucasus clusters.[111][112] Some of the Iranian groups lie within the Near Eastern group (often with such as the Turks and Georgians), but none fell into the Arab or Asian groups. Some Iranian groups in Iran, such as the Gilaki's and Mazandarani's, are genetically virtually identical to South Caucasus ethnic groups,[113] while the small Iranian Baloch ethnic group, being the only outliers who have heavy pulls towards South Asia.

In Afghanistan, Iranian population groups such as the Pashtuns and Tajiks occupy intermediate positions amongst northwestern South Asian ethnic groups, such as along the Baloch, Brahui, Kashmiri's and Sindhi's, with a small minor pull towards West Asia.[114][115]

Iranians are only distantly related to Europeans as a whole, predominantly with southern Europeans like Greeks, Albanians, Serbs, Croatians, Italians, Bosniks, Spaniards, Macedonians, Portuguese, and Bulgarians, rather than northern Europeans like Norwegians, Danes, Swedes, Irish, Scottish, English, Fins, Estonians, Welsh, Latvians, and Lithuanians.[116][2] Nevertheless, Iranian-speaking Central Asians do show closer affinity to Europeans than do Turkic-speaking Central Asians.[117]

See also

|

References

Citations

- ^ The Ossetians of the Caucasus are Orthodox Christians

- ^

- Iran: Library of Congress, Library of Congress – Federal Research Division. "Ethnic Groups and Languages of Iran" (PDF). Retrieved 2 December 2009. (Persian and Caspian dialects-65% Kurdish 8%-Luri/Bakhtiari 5%- Baluchi 4%):80% of the population or approximately 63 million people.

- Afghanistan: CIA Factbook Afghanistan: unting Pashtuns, Tajiks, Baluchs, 21 million

- Tajiks of Central Asia counting Tajikistan and Uzbekistan 10–15 million

- Kurds Syria, Lebanon and Iraq based on CIA factbook estimate 18 million

- Zazas of Turkey, based on CIA factbook estimate 4 million

- Ossetians, Talysh, Tats, Kurds of the Caucasus and Central Asia: 1–2 million based on CIA factbook/ethnologue.

- Tajiks of China: 50,000 to 100,000

- Iranian speakers in Bahrain, the Persian Gulf , Western Europe and USA, 3 million.

- Pakistan counting Baluchis+Pashtus+Afghan refugees based on CIA factbook and other sources: 71 million.

- ^ a b J.E. Peterson. "Oman's Diverse Society" (PDF). p. 4.

- ^ "The Report: Kuwait 2008". Oxford Business Group. 2008. p. 25.

- ^ R.N Frye, "IRAN v. PEOPLE OF IRAN in Encycloapedia Iranica. "In the following discussion of "Iranian peoples," the term "Iranian" may be understood in two ways. It is, first of all, a linguistic classification, intended to designate any society which inherited or adopted, and transmitted, an Iranian language. The set of Iranian-speaking peoples is thus considered a kind of unity, in spite of their distinct lineage identities plus all the factors which may have further differentiated any one group’s sense of self."

- ^ The Kurds: A Concise Handbook by Mehrdad R. Izady

- ^ Historical Dictionary of the Kurds by Michael M. Gunter

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana: The International Reference Work, Volume 15

- ^ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 692

- ^ "IRAN vi. IRANIAN LANGUAGES AND SCRIPTS". Encyclopædia Iranica. Bibliotheca Persica Press. 15 December 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ a b Beckwith 2009, pp. 58–77

- ^ Mallory 1997, pp. 308–311

- ^ Harmatta 1992, p. 348: "From the first millennium b.c., we have abundant historical, archaeological and linguistic sources for the location of the territory inhabited by the Iranian peoples. In this period the territory of the northern Iranians, they being equestrian nomads, extended over the whole zone of the steppes and the wooded steppes and even the semi-deserts from the Great Hungarian Plain to the Ordos in northern China."

- ^ a b Brzezinski, Richard; Mielczarek, Mariusz (2002). The Sarmatians, 600 BC-AD 450. Osprey Publishing. p. 39.

(..) Indeed, it is now accepted that the Sarmatians merged in with pre-Slavic populations.

- ^ a b Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 523.

(..) In their Ukrainian and Polish homeland the Slavs were intermixed and at times overlain by Germanic speakers (the Goths) and by Iranian speakers (Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans) in a shifting array of tribal and national configurations.

- ^ Women in Russia. Stanford University Press. 1977. p. 3.

(..) Ancient accounts link the Amazons with the Scythians and the Sarmatians, who successively dominated the south of Russia for a millennium extending back to the seventh century B.C. The descendants of these peoples were absorbed by the Slavs who came to be known as Russians.

{{cite book}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help) - ^ a b Slovene Studies. Vol. 9–11. Society for Slovene Studies. 1987. p. 36.

(..) For example, the ancient Scythians, Sarmatians (amongst others), and many other attested but now extinct peoples were assimilated in the course of history by Proto-Slavs.

- ^ Emmerick, Ronald Eric. "Iranian languages". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Frye, Richard Nelson, Greater Iran, ISBN 1-56859-177-2 p.xi: "... Iran means all lands and people where Iranian languages were and are spoken, and where in the past, multi-faceted Iranian cultures existed. ..."

- ^ Oxford English Dictionnary: "Aryan from Sanskrit Arya 'Noble'"

- ^ Gershevitch, I. (1968). "Old Iranian Literature". Iranistik. Hanbuch Der Orientalistik – Abeteilung – Der Nahe Und Der Mittlere Osten. Vol. 1. Brill Publishers. p. 203. ISBN 90-04-00857-8.: page 1

- ^ "Farsi-Persian language" — Farsi.net . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ a b c "Article in 1911 Britannica". 58.1911encyclopedia.org. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ G. Gnoli, "Iranian Identity as a Historical Problem: the Beginnings of a National Awareness under the Achaemenians," in The East and the Meaning of History. International Conference (23–27 November 1992), Roma, 1994, pp. 147–67. "?".

- ^ a b c d e f g G. Gnoli, "Iranian Identity ii. Pre-Islamic Period" in Encyclopedia Iranica. Online accessed in 2010 at "?".

- ^ a b c R. Schmitt, "Aryans" in Encyclopedia Iranica:Excerpt:"The name "Aryan" (OInd. āˊrya-, Ir. *arya- [with short a-], in Old Pers. ariya-, Av. airiia-, etc.) is the self designation of the peoples of Ancient Iran (as well as India) who spoke Aryan languages, in contrast to the "non-Aryan" peoples of those "Aryan" countries (cf. OInd. an-āˊrya-, Av. an-airiia-, etc.), and lives on in ethnic names like Alan (Lat. Alani, NPers. Īrān, Oss. Ir and Iron.". Also accessed online: "?". in May, 2010

- ^ a b The "Aryan" Language, Gherardo Gnoli, Instituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente, Roma, 2002.

- ^ a b c d H. W. Bailey, "Arya" in Encyclopedia Iranica. Excerpt: "ARYA an ethnic epithet in the Achaemenid inscriptions and in the Zoroastrian Avestan tradition. "Arya an ethnic epithet in the Achaemenid inscriptions and in the Zoroastrian Avestan tradition".[dead link] Also accessed online in May, 2010.

- ^ a b c D. N. Mackenzie, "Ērān, Ērānšahr" in Encyclopedia Iranica. "?". Retrieved 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Dalby, Andrew (2004), Dictionary of Languages, Bloomsbury, ISBN 0-7475-7683-1

- ^ G. Gnoli. "ēr, ēr mazdēsn". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- ^ a b c R. G. Kent. Old Persian. Grammar, texts, lexicon. 2nd ed., New Haven, Conn.

- ^ Professor Gilbert Lazard: The language known as New Persian, which usually is called at this period (early Islamic times) by the name of Dari or Parsi-Dari, can be classified linguistically as a continuation of Middle Persian, the official religious and literary language of Sassanian Iran, itself a continuation of Old Persian, the language of the Achaemenids. Unlike the other languages and dialects, ancient and modern, of the Iranian group such as Avestan, Parthian, Soghdian, Kurdish, Ossetian, Balochi, Pashto,Armenian etc., Old Middle and New Persian represent one and the same language at three states of its history. It had its origin in Fars (the true Persian country from the historical point of view) and is differentiated by dialectical features, still easily recognizable from the dialect prevailing in north-western and eastern Iran in Lazard, Gilbert 1975, "The Rise of the New Persian Language" in Frye, R. N., The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 4, pp. 595–632, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ R.W. Thomson. History of Armenians by Moses Khorenat’si. Harvard University Press, 1978. Pg 118, pg 166

- ^ MacKenzie D.N. Corpus inscriptionum Iranicarum Part. 2., inscription of the Seleucid and Parthian periods of Eastern Iran and Central Asia. Vol. 2. Parthian, London, P. Lund, Humphries 1976–2001

- ^ N. Sims-Williams, "Further notes on the Bactrian inscription of Rabatak, with the Appendix on the name of Kujula Kadphises and VimTatku in Chinese". Proceedings of the Third European Conference of Iranian Studies (Cambridge, September 1995). Part 1: Old and Middle Iranian<Studies, N. Sims-Williams, ed. Wiesbaden, pp 79-92

- ^ The "Aryan" Language, Gherardo Gnoli, Instituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente, Roma, 2002

- ^ Hamza Isfahani, Tarikh Payaambaraan o Shaahaan, translated by Jaf'ar Shu'ar,Tehran: Intishaaraat Amir Kabir, 1988.

- ^ G. Gnoli. "Iranian Identity ii. Pre-Islamic Period". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Amazons in the Scythia: new finds at the Middle Don, Southern Russia". Taylorandfrancis.metapress.com. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ "Secrets of the Dead, Casefile: Amazon Warrior Women". Pbs.org. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ Carl Waldman,Catherine Mason. "Encyclopedia of European Peoples" Infobase Publishing, 2006. ISBN 1438129181 p 692

- ^ Prudence Jones. Nigel Pennick. "A History of Pagan Europe" Routledge, 11 okt. 2. ISBN 1136141804 p 10

- ^ Ion Grumeza "Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe" University Press of America, 16 May 2009. ISBN 076184466X pp 19-21

- ^ Runciman, Steven (1982). The Medieval Manichee: A Study of the Christian Dualist Heresy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-28926-2.

- ^ Liverani, M. (1995). "The Medes at Esarhaddon's Court". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 47: 57–62. doi:10.2307/1359815.

- ^ "The Geography of Strabo" — University of Chicago. . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ A. Leo Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia, 1964[full citation needed]

- ^ Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty)

- ^ "Avestan xᵛarǝnah-, etymology and concept by Alexander Lubotsky" — Sprache und Kultur. Akten der X. Fachtagung der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft, 22.-28. September 1996, ed. W. Meid, Innsbruck (IBS) 1998, 479–488. . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ R. G. Kent, Old Persian: Grammar, texts and lexicon.

- ^ R. Hallock (1969), Persepolis Fortification Tablets; A. L. Driver (1954), Aramaic Documents of the V Century BC.

- ^ a b c d Greek and Iranian, E. Tucker, A History of Ancient Greek: From the Beginnings to Late Antiquity, ed. Anastasios-Phoivos Christidēs, Maria Arapopoulou, Maria Chritē, (Cambridge University Press, 2001), 780.

- ^ "Kurdish: An Indo-European Language By Siamak Rezaei Durroei" Archived 2006-06-17 at the Wayback Machine — University of Edinburgh, School of Informatics. . Retrieved 4 June 2006. Archived 2006-06-17 at the Wayback Machine[dead link]

- ^ "The Iranian Language Family, Khodadad Rezakhani" — Iranologie. . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ "Sarmatian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ Apollonius (Argonautica, iii) envisaged the Sauromatai as the bitter foe of King Aietes of Colchis (modern Georgia).

- ^ Arrowsmith, Fellowes, Hansard, A, B & G L (1832). A Grammar of Ancient Geography,: Compiled for the Use of King's College School (3 April 2006 ed.). Hansard London. p. 9. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arrowsmith, Fellowes, Hansard, A, B & G L (1832). A Grammar of Ancient Geography,: Compiled for the Use of King's College School (3 April 2006 ed.). Hansard London. p. 15. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schenker (2008, p. 109)

- ^ Sussex (2011, pp. 111–112)

- ^ Cross, 79.

- ^ a b A History of Russia by Nicholas Riasanovsky, pp. 11–18, Russia before the Russians, ISBN 0-19-515394-4 . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ The Sarmatians: 600 BC-AD 450 (Men-at-Arms) by Richard Brzezinski and Gerry Embleton, 19 Aug 2002

- ^ "Jeannine Davis-Kimball, Archaeologist" — Thirteen WNET New York. . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ James Minahan, "One Europe, Many Nations", Published by Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000. pg 518: "The Ossetians, calling themselves Iristi and their homeland Iryston are the most northerly Iranian people. ... They are descended from a division of Sarmatians, the Alans who were pushed out of the Terek River lowlands and in the Caucasus foothills by invading Huns in the 4th century AD.

- ^ "Ossetians". Encarta. Microsoft Corporation. 2008.

- ^ From Scythia to Camelot by Littleton and Malcor, pp. 40–43, ISBN 0-8153-3566-0 . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ "Report for Talysh" — Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ "Report for Tats" — Ethnologue. . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ "Report for Judeo-Tats" — Ethnologue. . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates by Hugh Kennedy, ISBN 0-582-40525-4 (retrieved 4 June 2006), p. 135

- ^ Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005). "Report for Iranian languages". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Fifteenth ed.). Dallas: SIL International.

{{cite journal}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hamzehʼee, M. Reza. The Yaresan: a sociological, historical and religio-historical study of a Kurdish community, 1990.

- ^ http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1529-8817.2005.00174.x/full

- ^ http://www.amazon.com/Zaza-Kurds-Turkey-Minority-Globalised/dp/1845118758/

- ^ Ethnologue report for Kumzari

- ^ In Search of the Indo-Europeans, by J.P. Mallory, p. 112–127, ISBN 0-500-27616-1 . Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ^ "Pakistan — Baloch" — Library of Congress Country Studies . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ "History of Iran-Chapter 2 Indo-Europeans and Indo-Iranians" — Iranologie . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective, edited by Robert Canfield, ISBN 0-521-52291-9 . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ "Azerbaijan-Iran Relations: Challenges and Prospects" — Harvard University, Belfer Center, Caspian Studies Program . Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ "Cambridge Genetic Study of Iran" — ISNA (Iranian Students News Agency), 06-12-2006, news-code: 8503-06068 . Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ^ Minorsky, V.; Minorsky, V. "(Azarbaijan). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W. P. Heinrichs. Brill

- ^ R. N. Frye. "People of Iran". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- ^ X.D. Planhol. "Lands of Iran". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- ^ Roy, Olivier (2007). The new Central Asia. I.B. Tauris. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-84511-552-4.

The mass of the Oghuz who crossed the Amu Darya towards the west left the Iranian plateaux, which remained Persian, and established themselves more to the west, in Anatolia. Here they divided into Ottomans, who were Sunni and settled, and Turkmens, who were nomads and in part Shiite (or, rather, Alevi). The latter were to keep the name 'Turkmen' for a long time: from the 13th century onwards they 'Turkised' the Iranian populations of Azerbaijan (who spoke west Iranian languages such as Tat, which is still found in residual forms), thus creating a new identity based on Shiism and the use of Turkish. These are the people today known as Azeris.

- ^ Yarshater, Ehsan (15 December 1988). "AZERBAIJAN vii. The Iranian Language of Azerbaijan". Encyclopædia Iranica. Bibliotheca Persica Press. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia: Azerbaijan Archived 2006-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Who are the Azeris? by Aylinah Jurabchi". The Iranian. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ ingentaconnect.com

- ^ Askarov, A. & B.Ahmadov, O'zbek Xalqning Kilib Chiqishi Torixi. O'zbekiston Ovozi, 20 January 1994.

- ^ Tanzania Ethnic Groups, East Africa Living Encyclopedia, accessed 28 June 2010

- ^ Regueiro; et al. (2006). "Iran: Tricontinental Nexus for Y-Chromosome Driven Migration". Hum Hered. 61: 132–143. doi:10.1159/000093774. PMID 16770078.

- ^ Grugni (2012). "Ancient Migratory Events in the Middle East: New Clues from the Y-Chromosome Variation of Modern Iranians". PLOS ONE. 7: e41252. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041252. PMC 3399854. PMID 22815981.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Sengupta et al. Polarity and Temporality of High-Resolution Y-Chromosome Distributions in India Identify Both Indigenous and Exogenous Expansions and Reveal Minor Genetic Influence of Central Asian Pastoralists. AJHG 78; 2. 2006

- ^ Cinnioglu et al. Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia" Hum Genet 2004 Jan;114(2):127-48. Epub 2003 Oct 29.

- ^ Semino, Ornella; et al. (May 2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area". American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1023–1034. doi:10.1086/386295. PMC 1181965. PMID 15069642.

- ^ Regueiro, 2006

- ^ New Y-chromosome binary markers improve phylogenetic resolution within haplogroup R1a1. Horolma Pamjav et al. AJPA DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.22167. 2012

- ^ Pamjav; 2012. "Inner and Central Asia is an overlap zone for the R1a1-Z280 and R1a1-Z93 lineages. This pattern implies that an early differentiation zone of R1a1-M198 conceivably occurred somewhere within the Eurasian Steppes or the Middle East and Caucasus region as they lie between South Asia and Eastern Europe"

- ^ Grugni, 2013.

- ^ Myres; et al. (2011). "A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 19: 95–101. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.146. PMC 3039512. PMID 20736979.

- ^ Rootsi; et al. (2012). "Distinguishing the co-ancestries of haplogroup G Y-chromosomes in the populations of Europe and the Caucasus". European Journal of Human Genetics. 20: 1275–1282. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.86. PMID 22588667.

- ^ a b Grugni, 2012

- ^ Afghanistan's Ethnic Groups Share a Y-Chromosomal Heritage Structured by Historical Events. PLOS One mach 2012. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034288

- ^ Afghan Hindu Kush: Where Eurasian Sub-Continent Gene Flows Converge. PLOS One, Oct 2013. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076748

- ^ Haber, 2012

- ^ Grugni 2012

- ^ Haber 2012

- ^ "West Asian clusters compared with Europe and Asia". Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "West Asian and European clusters, PCA plot". Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "Concomitant Replacement of Language and mtDNA in South Caspian Populations of Iran". Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "PCA plot West Asian_European_South Asian populations". Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "Major admixture in India took place ~4.2-1.9 thousand years ago (Moorjani et al. 2013)". Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ Grugni (2012)p="Iranian groups do not cluster all together, occupying intermediate positions among Arab, Near Eastern and Asian clusters"

- ^ Dr Cristofaro, 2013

Literature and further reading

- Banuazizi, Ali and Weiner, Myron (eds.). The State, Religion, and Ethnic Politics: Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan (Contemporary Issues in the Middle East), Syracuse University Press (August, 1988). ISBN 0-8156-2448-4.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691135894. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Canfield, Robert (ed.). Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2002). ISBN 0-521-52291-9

- Curzon, R. The Iranian People of the Caucasus. ISBN 0-7007-0649-6.

- Derakhshani, Jahanshah. Die Arier in den nahöstlichen Quellen des 3. und 2. Jahrtausends v. Chr., 2nd edition (1999). ISBN 964-90368-6-5.

- Frye, Richard, Greater Iran, Mazda Publishers (2005). ISBN 1-56859-177-2.

- Frye, Richard. Persia, Schocken Books, Zurich (1963). ASIN B0006BYXHY.

- Harmatta, János (1992). "The Emergence of the Indo-Iranians: The Indo-Iranian Languages". In Dani, A. H.; Masson, V. M. (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Dawn of Civilization: Earliest Times to 700 B. C. (PDF). UNESCO. pp. 346–370. ISBN 978-92-3-102719-2. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kennedy, Hugh. The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates, Longman, New York, NY (2004). ISBN 0-582-40525-4

- Khoury, Philip S. & Kostiner, Joseph. Tribes and State Formation in the Middle East, University of California Press (1991). ISBN 0-520-07080-1.

- Littleton, C. & Malcor, L. From Scythia to Camelot, Garland Publishing, New York, NY, (2000). ISBN 0-8153-3566-0.

- Mallory, J.P. In Search of the Indo-Europeans, Thames and Hudson, London (1991). ISBN 0-500-27616-1.

- Mallory, J. P. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1884964982. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McDowall, David. A Modern History of the Kurds, I.B. Tauris, 3rd Rev edition (2004). ISBN 1-85043-416-6.

- Nassim, J. Afghanistan: A Nation of Minorities, Minority Rights Group, London (1992). ISBN 0-946690-76-6.

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas. A History of Russia, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2004). ISBN 0-19-515394-4.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas. Indo-Iranian Languages and People, British Academy (2003). ISBN 0-19-726285-6.

- Iran Nama, (Iran Travelogue in Urdu) by Hakim Syed Zillur Rahman, Tibbi Academy, Aligarh, India (1998).

- Saga of the Aryans, Historical novel on ancient Iranian migrations by Porus Homi Havewala, Published Mumbai, India (2005, 2010).

- Chopra, R. M.,"Indo-Iranian Cultural Relations Through The Ages", Iran Society, Kolkata, 2005.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438129181. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)