Seljuk dynasty

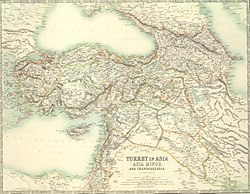

Template:Turkish History Brief Template:Iran The Seljuqs (also Seldjuk, Seldjuq, Seljuk, sometimes also Seljuq Turks; in modern Turkish Selçuklular; in Persian سلجوقيان Saljūqiyān; in Arabic سلجوق Saljūq, or السلاجقة al-Salājiqa) were a Muslim dynasty of originally Oghuz Turkic descent[1][2][3][4] that ruled parts of Central Asia and the Middle East from the 11th to 14th centuries. Today, they are remembered as great patrons of Persian culture, art, literature, and language and for setting up an empire known as "Great Seljuk Empire" that stretched from Anatolia to Pakistan and was the target of the First Crusade. They are also regarded as the cultural ancestors of the Western Turks, the present-day inhabitants of Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Turkmenistan.

Early History

Origins

Originally, the House of Seljuq was a branch of the Kinik Oghuz Turks who in the 9th century lived on the periphery of the Muslim world, north of the Caspian and Aral sea in their Yabghu Khaganate of the Oghuz confederacy.[5] In the 10th century the Seljuqs migrated from their ancestral homelands into mainland Persia, where they adopted the Persian culture and language in the following decades[6][7][8]. Later the Seljuk of the Rum led a renaissance in the Turkish language and culture in their new capital in Konya and Alanya (Turkey).

Seljuk

- Main article: Seljuk

The apical ancestor of the Seljuqs was their bey Seljuq who was reputed to have served in the Khazar army, under whom, circa 950 CE they migrated to Khwarezm, near the city of Jend also called Khujand, where they converted to Islam.[9]

Great Seljuk

The Seljuqs were allied with the Persian Samanid Shahs against the Qarakhanids. The Samanids however fell to the Qarakhanids and the emergence of the Ghaznavids and were involved in the power struggle in the region before establishing their own independent base.

Toğrül and Çağrı Bey

Toğrül Bey was the grandson of Seljuk and Çağrı (Chagri) was his brother, under whom the Seljuks wrested an empire from the Ghaznavids. Initially the Seljuks were repulsed by Mahmud and retired to Khwarezm but Toğrül and Çağrı led them to capture Merv and Nishapur (1028-1029). Later they repeatedly raided and traded territory with his successors across Khorasan and Balkh and even sacked Ghazni in 1037. In 1039 at Battle of Dandanaqan they decisively defeated Mas'ud I of the Ghaznavids resulting in him abandoning most of his western territories to the Seljuks. In 1055 Toğrül captured Baghdad from the Shi'a Buyids under a commission from the Abbassids.

Alp Arslan

Alp Arslan was the son of Çağrı Bey and expanded significantly upon Toğrül's holdings by adding Armenia and Georgia in 1064 and invading the Byzantine Empire in 1068 from whom he annexxed Anatolia after defeating them at the Battle of Manzikert. He ordered his Turcoman generals to conquer the Byzantine lands and allowed them to carve principalities of their own as atabegs that were loyal to him. Within two years the Turcomans captured Asia Minor and went as far as the Aegean Sea establishing numerous "beghliks" such as the: Saltuqis in Northeastern Anatolia, Mengujeqs in Eastern Anatolia, Artuqids in Southeastern Anatolia, Danishmendis in Central Anatolia, Rum Seljuks (Beghlik of Süleyman, which later moved to Central Anatolia) in Western Anatolia and the Beghlik of Çaka Bey in İzmir (Smyrna).

Mālik Shāh I

Under Alp Arslan's successor Mālik Shāh and his two Persian viziers[10] Nizām al-Mulk and Tāj al-Mulk, the Seljuk state expanded in various directions to former Iranian border before Arab invasion, so that it bordered China in the East and the Byzantines in the West. He moved the capital from Rayy to Isfahan. The Iqta mililtary system and the Nizāmīyyah University at Baghdad were established by Nizām al-Mulk, and the reign of Mālik Shāh was reckoned the golden age of "Great Seljuk". The Abassid Caliph titled him "The Sultan of the East and West" in 1087. The Assassins of Hassan-e Sabāh however started to become a force during his era and assassinated many leading figures in his administration.

Governance

The Seljuk power was at it's zenith under Malik Shah, and both the Qarakhanids and Ghaznavids had to acknowledge the overlordship of the Seljuks.[11]. The Seljuk dominion was established over with the Sassanid domains, in Iran and Iraq, and included Anatolia as well as parts of Central Asia and Afghanistan.[11] The Seljuks kept their distance from the the Iranian tradition and by the 11th century, the term had lost the political connotations it held under the Sassanids.[11] The Seljuk rule was modelled after the tribal organization brought in by the nomadic conquerors and resembled a 'family federation' or 'appanage state'.[11] Under this organization the leading member of the paramount family assigned family members portions of his domains as autonomous appanages.[11]

Division of Empire

- See also: Sultanate of Rum, Atabegs

When Malik Shah I died in 1092 the empire split, as his brother and four sons quarrelled over the apportioning of the empire among themselves. In Anatolia, Malik Shah I was succeeded by Kilij Arslan I who founded the Sultanate of Rum and in Syria by his brother Tutush I. In Persia he was succeeded by his son Mahmud I whose reign was contested by his other three brothers Barkiyaruq in Iraq, Mehmed I in Baghdad and Ahmed Sanjar in Khorasan.

When Tutush I died his sons Radwan and Duqaq inherited Aleppo and Damascus respectively and contested with each other as well further dividing Syria amongst emirs antagonistic towards each other.

In 1118, the third son Ahmed Sanjar took over the empire. His nephew, the son of Mehmed I did not recognize his claim to the throne and Mahmud II proclaimed himself Sultan and established a capital in Baghdad, until 1131 when he was finally officially deposed by Ahmed Sanjar.

Elsewhere in nominal Seljuk territory were the Artuqids in northeastern Syria and northern Mesopotamia. They controlled Jerusalem until 1098. In eastern Anatolia and northern Syria a state was founded by Danishmend, and contested land with the Sultanate of Rum and Kerbogha excercised greeted independence as the atabeg of Mosul.

The First Crusade

- Main article: First Crusade

The fractured states of the Seljuks were on the whole more concerned with consolidating their own territories and gaining control of their neighbours, than with cooperating against the crusaders when the First Crusade arrived in 1095 and successfully captured the Holy land to set up the Crusader States. The Seljuks had already lost Palestine to the Fatimid before their capture by the crusaders.

The Second Crusade

- See also: Second Crusade, Zengi, Nur ad-Din

Ahmed Sanjar had to contend the revolts of Qarakhanids in Transoxiana, Ghorids in Afghanistan and Qarluks in modern Kyrghyzstan, even as the nomadic Kara-Khitais invaded the East destroying the Seljuk vassal state of the Eastern Qarakhanids. At the Battle of Qatwan Sanjar 1141 and lost all his eastern provinces up to the Syr Darya.

During this time conflict with the Crusader States was also intermittent and after the First Crusade and increasingly independent atabegs would frequently ally with the crusader states against other atabegs as they vied with each other for territory. At Mosul Zengi succeeded Kerbogha as atabeg and successfully began the process of consolidating the atabegs of Syria. In 1144 Zengi captured Edessa, as the County of Edessa had allied itself with the Ortoqids against him. This event triggered the launch of the second crusade. Nur ad-Din, one of Zengi's sons who succeeded him as atabeg of Aleppo and created an alliance in the region to oppose the second crusade which landed in 1147.

Conquest by Khwarezm and the Ayyubids

- See also:Saladin, Ayyubid, Khwarezmid Empire

In 1153 the Oghuz Turks rebelled and captured Sanjar. He managed to escaped three years later but died a year later. Despite several attempts to reunite the Seljuks by his successors, the Crusades prevented them from regaining their former empire. While the Atabegs such as the Zengids and Artuqids were only nominally under the Seljuk Sultan, and generally controlled Syria independently. When Ahmed Sanjar died in 1156 it fractured the empire even further rendering the atabegs effectively independent.

- Khorasani Seljuks in Khorasan and Transoxiana. Capital: Merv

- Kermani Seljuks

- Sultanate of Rum. Capital: Iznik (Nicaea), later Konya (Iconium)

- Atabeghlik of Salgur in Iran

- Atabeghlik of Ildeniz in Iraq and Azerbaijan. Capital Hamadan

- Atabeghlik of Bori in Syria. Capital: Damascus

- Atabeghlik of Zangi in Al Jazira (Northern Mesopotamia). Capital: Mosul

- Turcoman Beghliks: Danishmendis, Artuqids, Saltuqis and Mengujegs in Asia Minor

- Khwarezmshahs in Transoxiana, Khwarezm. Capital: Urganch

After the Second Crusade Nur ad-Din's general Shirkuh, who had established himself in Egypt on Fatimid land, was succeeded by Saladin who rebelled against Nur ad-Din. Upon Nur ad-Dins death, Saladin married his widow and captured most of Syria creating the Ayyubid dynasty.

On other fronts the the Kingdom of Georgia began to become a regional power and extended its borders at the expense of Great Seljuk as did the revival of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia under Leo II of Armenia in Anatolia. The Abbassid caliph An-Nasir also began to reassert the authority of the caliph and allied himself with the Khwarezmshah Ala ad-Din Tekish.

For a brief period Toğrül III was the Sultan of all Seljuk except for Anatolia.[citation needed] In 1194 Toğrül was defeated by Ala ad-Din Tekish, the Shah of Khwarezmid Empire, and the Seljuk finally collapsed. Of the former Seljuk Empire, only the Sultanate of Rüm in Anatolia remained. As the dynasty declined in the middle of the 13th century, the Mongols invaded Anatolia in the 1260s and divided it into small emirates called the Anatolian beyliks, one of which, the Ottoman, would rise to power and conquer the rest.

- Tugrul I (Tugrul Beg) 1037-1063

- Alp Arslan bin Chaghri 1063-1072

- Jalal ad-Dawlah Malik Shah I 1072-1092

- Nasir ad-Din Mahmud I 1092-1093

- Rukn ad-Din Barkiyaruq 1093-1104

- Mu'izz ad-Din Malik Shah II 1105

- Ghiyath ad-Din Muhammad/Mehmed I Tapar 1105-1118

- Mahmud II 1118-1131

- Mu'izz ad-Din Ahmed Sanjar 1131-1157

Kerman was a nation in southern Persia. It fell in 1187, probably conquered by Toğrül III of Great Seljuk.

- Qawurd 1041-1073

- Kerman Shah 1073-1074

- Sultan Shah 1074-1075

- Hussain Omar 1075-1084

- Turan Shah I 1084-1096

- Iran Shah 1096-1101

- Arslan Shah I 1101-1142

- Mehmed I (Muhammad) 1142-1156

- Toğrül Shah 1156-1169

- Bahram Shah 1169-1174

- Arslan Shah II 1174-1176

- Turan Shah II 1176-1183

- Mehmed II (Muhammad) 1183-1187

- Abu Sa'id Taj ad-Dawla Tutush I 1085-1086

- Jalal ad-Dawlah Malik Shah I of Great Seljuk 1086-1087

- Qasim ad-Dawla Abu Said Aq Sunqur al-Hajib 1087-1094

- Abu Sa'id Taj ad-Dawla Tutush I (second time) 1094-1095

- Fakhr al-Mulk Radwan 1095-1113

- Tadj ad-Dawla Alp Arslan al-Akhras 1113-1114

- Sultan Shah 1114-1123

- Aziz ibn Abaaq al-Khwarazmi 1076-1079

- Abu Sa'id Taj ad-Dawla Tutush I 1079-1095

- Abu Nasr Shams al-Muluk Duqaq 1095-1104

- Tutush II 1104

- Muhi ad-Din Baqtash 1104

- Kutalmish 1060-1077

- Süleyman Ibn Kutalmish (Suleiman) 1077-1086

- Dawud Kilij Arslan I 1092-1107

- Malik Shah 1107-1116

- Rukn ad-Din Mas'ud 1116-1156

- Izz ad-Din Kilij Arslan II 1156-1192

- Ghiyath ad-Din Kay Khusrau I 1192-1196

- Süleyman II (Suleiman) 1196-1204

- Kilij Arslan III 1204-1205

- Ghiyath ad-Din Kay Khusrau I (second time) 1205-1211

- Izz ad-Din Kay Ka'us I 1211-1220

- Ala ad-Din Kay Qubadh I 1220-1237

- Ghiyath ad-Din Kay Khusrau II 1237-1246

- Izz ad-Din Kay Ka'us II 1246-1260

- Rukn ad-Din Kilij Arslan IV 1248-1265

- Ala ad-Din Kay Qubadh II 1249-1257

- Ghiyath ad-Din Kay Khusrau II (second time) 1257-1259

- Ghiyath ad-Din Kay Khusrau III 1265-1282

- Ghiyath ad-Din Mas'ud II 1282-1284

- Ala ad-Din Kay Qubadh III 1284

- Ghiyath ad-Din Mas'ud II (second time) 1284-1293

- Ala ad-Din Kay Qubadh III (second time) 1293-1294

- Ghiyath ad-Din Mas'ud II (third time) 1294-1301

- Ala ad-Din Kay Qubadh III (third time) 1301-1303

- Ghiyath ad-Din Mas'ud II (fourth time) 1303-1307

- Ghiyath ad-Din Mas'ud III 1307

See also

- Turkic peoples

- Zengid dynasty

- Atabeg

- Artuqid

- Danishmend

- Ghaznavid Empire

- Sultanate of Rüm

- Ottoman Empire

- Seljuk

- Seldschuken-Fürsten, list of Seljuk rulers in the German Wikipedia

References

- ^ Concise Britannica Online Seljuq Dynasty article

- ^ Merriam-Webster Online - Definiton of Seljuk

- ^ The History of the Seljuq Turks: From the Jami Al-Tawarikh (LINK)

- ^ History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey - Stanford Shaw (LINK)

- ^ Wink, Andre, Al Hind the Making of the Indo Islamic World, Brill Academic Publishers, Jan 1, 1996, ISBN 9-004-09249-8 pg.9

- ^ M.A. Amir-Moezzi, "Shahrbanu", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, (LINK): "... here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkish heroes or Muslim saints ..."

- ^ O.Özgündenli, "Persian Manuscripts in Ottoman and Modern Turkish Libraries", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, (LINK)

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, "Seljuq", Online Edition, (LINK): "... Because the Turkish Seljuqs had no Islamic tradition or strong literary heritage of their own, they adopted the cultural language of their Persian instructors in Islam. Literary Persian thus spread to the whole of Iran, and the Arabic language disappeared in that country except in works of religious scholarship ..."

- ^ Wink, Andre, Al Hind the Making of the Indo Islamic World, Brill Academic Publishers, Jan 1, 1996, ISBN 9-004-09249-8 pg.9

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, "Nizam al-Mulk", Online Edition, (LINK)

- ^ a b c d e Wink, Andre, Al Hind the Making of the Indo Islamic World, Brill Academic Publishers, Jan 1, 1996, ISBN 9-004-09249-8 pg 9-10

External links

| History of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|