Luton

Luton | |

|---|---|

| |

|

Official logo of Luton Coat of arms of Luton Borough Council | |

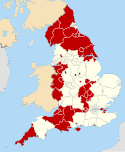

Luton shown within Bedfordshire | |

| Coordinates: 51°52′47″N 0°25′03″W / 51.87972°N 0.41750°W | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Constituent area | England |

| Region | East of England |

| Ceremonial county | Bedfordshire |

| Borough | Luton |

| Government | |

| • Type | Borough |

| • Governing body | Luton Borough Council |

| • Executive: | Labour |

| • Mayor | Tahir Khan |

| • MPs | Kelvin Hopkins (L) Gavin Shuker (L) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 16.74 sq mi (43.35 km2) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 226,973 |

| • Density | 13,560/sq mi (5,236/km2) |

| • Ethnicity | 54.6% White 29.9% Asian 9.8% Black 4.2% Mixed Race 1.5% Other[2] |

| Time zone | GMT |

| • Summer (DST) | British Summer Time |

| Postcode Area | |

| Area code | (01582) |

| ONS code | 00KA |

| Demonym | Lutonians |

| Airport code | LTN |

| Website | www.luton.gov.uk |

Luton (/ˈluːtən/ LOOT-ən)[4] is a large town in Bedfordshire, England,[5][6] 20 miles (30 km) east of Aylesbury, 14 miles (20 km) west of Stevenage, 30 miles (50 km) northwest of London, and 22 miles (40 km) southeast of Milton Keynes.

London Luton Airport, opened in 1938, is one of Britain's major airports. The University of Bedfordshire is also based in the town.

Luton is home to League One team Luton Town Football Club, whose history includes several spells in the top flight of the English league as well as a Football League Cup triumph in 1988. They play at Kenilworth Road, their home since 1905.

The town was for many years famous for hat-making, and also had a large Vauxhall Motors factory. Car production at the plant began in 1905 and continued until 2002. Production of commercial vehicles continues, and the head office of Vauxhall Motors is still in the town.

Luton Carnival, traditionally held on the Whitsun May bank holiday, is the largest one-day carnival in Europe.[7]

History

Early history

The earliest settlements in the Luton area were at Round Green and Mixes Hill, where Paleolithic encampments (about 250,000 years old) have been found.[8] Settlements re-appeared after the ice had retreated in the Mesolithic period around 8000 BC. Traces of these settlements have been found[by whom?] in the Leagrave area of the modern town. Remains from the Neolithic period (4500–2500 BC in this area) are much more common. A particular concentration of Neolithic burials occurs at Galley Hill.[9] The most prominent Neolithic structure is Waulud's Bank – a henge dating from around 3000 BC. From the Neolithic onwards, the area seems to have been populated, but without any single large settlement. Luton itself is believed to have been founded by the Anglo-Saxons sometime in the 6th century,[10] and named for its situation on the River Lea.[11]

After the establishment of the Danelaw in the east of England and the unification of the remaining English kingdoms in the west, Luton stood on the border between Christendom and Heathenism which ran up the River Lea from London through to Bedford.[12]

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle for the year 913 mentions Luton because locals fought off a Viking raiding band: "In this year the [Danish] army from Northampton and Leicester rode out after Easter [28th March] and broke the peace, and killed many men at Hook Norton [Oxfordshire] and round about there. And then very soon after that, as the one force came home, they met another raiding band which rode out against Luton. And then the people of the district became aware of it and fought against them and reduced them to full flight and rescued all that they had captured and also a great part of their horses and their weapons".[12]

Archaeological finds for this genesis of Lutonian history include 50 burials, 8 cremations, 16 spears, 22 knives (seax), a sword, 8 shield bosses, a pair of iron shears, a single bone comb, countless examples of brooches, pendants and other jewellery of bronze and amber and shards of pottery.[13]

The Domesday Book records Luton as Loitone and also as Lintone.[14] Agriculture dominated the local economy at that time, and the town's population was around 700 to 800.[15] But this number could[original research?] represent a recently reduced population as a direct result of the Norman Invasion and the English resistance that followed. The Domesday Book records the value of King William's English possessions 20 years after his victory at Hastings, during which period, as the book would suggest, much destruction and death took place. Besides Luton, Biscot and Caddington also have entries in the Domesday Book for the surrounding area and in both these cases the value of the lands are much lower than their pre-invasion state, indicating a loss of households, livestock and crops.[16][17]

In 1121 Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester started work on St Mary's Church in the centre of the town. The work was completed by 1137.[18] A motte-and-bailey castle which gives its name to the modern Castle Street was built in 1139. The castle was demolished in 1154[19] and the site is now occupied by a Matalan store. During the Middle Ages Luton is recorded[by whom?] as having six watermills. Mill Street, in the town centre, takes its name from one of them.

King John (1166–1216) had hired a mercenary soldier, Falkes de Breauté, to act on his behalf. (Breauté is a small town near Le Havre in France.) When he married, Falkes de Breauté acquired his wife's house which came to be known as "Fawkes Hall", subsequently corrupted over the years to "Foxhall", then to "Vauxhall". In return for his services, King John granted Falkes the manor of Luton, where he built a castle alongside St Mary's Church. He was also granted the right to bear his own coat of arms and chose the mythical griffin as his heraldic emblem. The griffin thus became associated with both Vauxhall and Luton in the early 13th century.[20]

By 1240 the town is recorded as "Leueton". One "Simon of Luton" was Abbot of Bury St Edmunds from 1257 to 1279. The town had a market for surrounding villages in August each year, and with the growth of the town a second fair was granted each October from 1338.

In 1336 a large fire destroyed much of Luton; however, the town was soon rebuilt.

The agriculture base of the town changed in the 16th century with a brick-making industry developing around Luton; many of the older wooden houses were rebuilt in brick.

17th century

During the English Civil War of the 17th century, in 1645, royalists entered the town and demanded money and goods. Parliamentary forces arrived and during the fighting four royalist soldiers were killed and a further twenty-two were captured. A second skirmish occurred three years later in 1648 when a royalist army passed through Luton. A number of royalists were attacked by parliamentary soldiers at an inn on the corner of the current Bridge Street. Most of the royalists escaped but nine were killed.

18th century

The hat making industry began in the 17th century and became synonymous with the town.[21][failed verification] By the 18th century the industry dominated the town.[citation needed] Hats are still produced in the town but on a much smaller scale.

The first Luton Workhouse was constructed in the town in 1722.[22]

Luton Hoo, a nearby large country house, was built in 1767 and substantially rebuilt after a fire in 1843. It is now a luxury hotel.[23]

19th century

The town grew strongly in the 19th century. In 1801 the population was 3,095.[24] By 1850 it was over 10,000 and by 1901 it was almost 39,000. Such rapid growth demanded a railway connection but the town had to wait a long time for one. The London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR) had been built through Tring in 1838, and the Great Northern Railway was built through Hitchin in 1852, both bypassing Luton, the largest town in the area. A branch line connecting with the L&BR at Leighton Buzzard was proposed, but because of objections to release of land, construction terminated at Dunstable in 1848. It was another ten years before the branch was extended to Bute Street Station, and the first train to Dunstable ran on 3 May 1858.[25] The line was later extended to Welwyn and from 1860 direct trains to King's Cross ran. The Midland Railway was extended from Bedford to St Pancras through Leagrave and Midland Road station and opened on 9 September 1867.[26]

Luton received a gas supply in 1834. Gas street lights were erected and the first town hall was opened in 1847.[27]

Following a cholera epidemic in 1848 Luton established a water company and had a complete water and sewerage system by the late 1860s. Newspaper printing arrived in the town in 1854. The first public cemetery was opened in the same year. The first covered market was built (the Plait Halls – now demolished) in 1869. Luton was made a borough in 1876.[28] A professional football club – the first in the South of England – was founded in 1885 following a resolution at the town hall that a 'Luton Town Club be formed'.[29]

The crest also includes a hand holding a bunch of wheat, either taken as a symbol of the straw-plaiting industry, or from the arms of John Whethamsteade, Abbott of St Albans, who rebuilt the chancel of St Mary's Church in the 15th century.

20th century

Luton's hat trade reached its peak in the 1930s,[30] but severely declined after the Second World War and was replaced by other industries.

In 1907, Vauxhall Motors opened the largest car plant in the United Kingdom in Luton.

In 1914 Hewlett & Blondeau aviation entrepreneurs built a factory in Leagrave which began aircraft production built under licence for the war effort; the site was purchased in 1920 by new proprietors Electrolux domestic appliances, and this was followed by other light engineering businesses.

In 1901 the Bailey Water Tower was built[31] on the edge of what was to become Luton Hoo memorial park. It is now a private residence.

In 1904 councillors Asher Hucklesby and Edwin Oakley purchased the estate at Wardown Park and donated it to the people of Luton. Hucklesby went on to become Mayor of Luton. The main house in the park became Wardown Park Museum.

The town had a tram system from 1908 until 1932, and the first cinema was opened in 1909. By 1914 the population had reached 50,000.

The original town hall was destroyed in 1919 during Peace Day celebrations at the end of the First World War. Local people, including many ex-servicemen, were unhappy with unemployment and had been refused the use of a local park to hold celebratory events. They stormed the town hall, setting it alight (see Luton Town Hall). A replacement building was completed in 1936. Luton Airport opened in 1938, owned and operated by the council.

The pre-war years, even at the turn of the 1930s when a Great Depression saw unemployment reach record levels nationally, were something of an economic boom for Luton, as new industries grew and prospered. New private and council housing was built in the 1920s and 1930s, with Luton growing as a town to incorporate nearby villages Leagrave, Limbury and Stopsley between 1928 and 1933.[32]

In the Second World War, the Vauxhall Factory built Churchill tanks[33] as part of the war effort. Despite heavy camouflage, the factory made Luton a target for the Luftwaffe and the town suffered a number of air raids. 107 died[34] and there was extensive damage to the town (over 1,500 homes were damaged or destroyed). Other industry in the town, such as SKF, which produced ball bearings, made a vital contribution to the war effort. Although a bomb landed at the SKF Factory,[35] no major damage was caused. Post-war, the slum clearance continued, and a number of substantial estates of council housing were built, notably at Farley Hill, Stopsley, Limbury, Marsh Farm and Leagrave (Hockwell Ring). The M1 motorway passed just to the west of the town, opening in 1959 and giving it a direct motorway link with London and – eventually – the Midlands and the North. In 1962 a new library (to replace the cramped Carnegie Library) was opened by the Queen in the corner of St George's Square.

In the late 1960s a large part of the town centre was cleared to build a large covered shopping centre, the Arndale Centre, which was opened in 1972.[36] It was refurbished and given a glass roof in the 1990s.

In 2000, Vauxhall announced the end of car production in Luton; the plant closed in March 2002.[37] At its peak it had employed in excess of 30,000 people. Vauxhall's headquarters remain in the town, as does its van and light commercial vehicle factory.

21st century

A major regeneration programme for the town centre is under way, which will include upgrades to the town's bus and railway stations as well as improvements to the town's urban environment. St George's Square has been rebuilt[38] and reopened in 2007. The new design won a Gold Standard Award for the Town Centre Environment from the annual British Council of Shopping Centres awards.[39]

Work was completed on an extension to the Mall Shopping Centre facing St George's Square, the largest of the new units to was taken by TK Maxx. Planning applications for a much larger extension to the Mall Arndale Shopping Centre (In the Northern Gateway area – Bute Street, Silver Street and Guildford Street) and also for a new centre in Power Court[40] (close to St Mary's Church) have been submitted. On the edge of Luton at Putteridge Bury a high-technology office park, Butterfield Green, is under construction. The former Vauxhall site is also to be re-developed as a mixed use site called Napier Park.[41] It will feature housing, retail and entertainment use, including a new casino.

Governance

The town is situated within the historic county of Bedfordshire, but since 1997 Luton has been an administratively independent unitary authority. The town remains part of Bedfordshire for ceremonial purposes.

Luton Borough Council applied for city status at the Millennium in 2000, Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II in 2002 and Diamond Jubilee in 2012.[42] The latest bid was rejected in March 2012.[43]

Parliamentary representation

Luton is represented by two Members of Parliament. The constituency of Luton North has been held by Kelvin Hopkins (Labour) since 1997. Luton South has been held by Gavin Shuker (Labour) since 2010. Luton is within the East of England European Parliament constituency.

Wards

The electoral wards in Luton are:

|

Police and crime commissioner

Luton is served by the Bedfordshire police. The Bedfordshire Police and Crime Commissioner is Kathryn Holloway.

Local council

Lutonians are governed by Luton Borough Council. The town is split into 19 wards, represented by 48 councillors. Elections are held for all seats every four years, with the most recent local elections held in May 2011 and the next due in May 2015. The Council is controlled by the Labour group, who have 36 Local Councillors (a majority of 24). The next largest party is the Liberal Democrats with 8 seats, followed by the Conservative Party with 4 seats.[44]

| Position | Current representatives |

|---|---|

| Members of Parliament |

Luton Council coat of arms

In 1876 the town council was granted its own coat of arms. The wheatsheaf was used on the crest to represent agriculture and the supply of straw used in the local hatting industry (the straw-plaiting industry was brought to Luton by a group of Scots under the protection of Sir John Napier of Luton Hoo). The bee is traditionally the emblem of industry and the hive represents the straw-plaiting industry for which Luton was famous. The rose is from the arms of the Napier family, whereas the thistle is a symbol for Scotland. An alternative suggestion is that the rose was a national emblem, and the thistle represents the Marquess of Bute, who formerly owned the Manor of Luton Hoo.[45][46]

Geography

Luton is located in a break in the eastern part of the Chiltern Hills. The Chilterns are a mixture of chalk from the Cretaceous period[47] (about 66 – 145 million years ago) and deposits laid at the southernmost points of the ice sheet during the last ice age (the Warden Hill area can be seen from much of the town).

Bedfordshire had a reputation for brick making but the industry is now significantly reduced. The brickworks[48] at Stopsley took advantage of the clay deposits in the east of the town.

The source of the River Lea, part of the Thames Valley drainage basin, is in the Leagrave area of the town. The Great Bramingham Wood surrounds this area. It is classified as ancient woodland; records mention the wood at least 400 years ago.

There are few routes through the hilly area for some miles, this has led to several major roads (including the M1 and the A6) and a major rail-link being constructed through the town.

Areas

The Victorian expansion of Luton focused on areas close to the existing town centre and railways. In the 1920s and 1930s growth typically was through absorbing neighbouring villages and hamlets (an example being Leagrave) and infill construction between them and Luton. After the Second World War there were several estates and developments constructed both by the local council such as Farley Hill or Marsh Farm, or privately such as Bushmead.

Climate

Luton has a temperate marine climate, like much of the British Isles, with generally light precipitation throughout the year. The weather is very changeable from day to day and the warming influence of the Gulf Stream makes the region mild for its latitude. The average total annual rainfall is 698 mm (27.5 in) with rain falling on 117 days of the year.

The local climate around Luton is differentiated somewhat from much of South East England due to its position in the Chiltern Hills, meaning it tends to be 1–2 degrees Celsius cooler than the surrounding towns – often flights at Luton airport, lying 160 m (525 ft) above sea level, will be suspended when marginal snow events occur, while airports at lower elevations, such as Heathrow, at 25 m (82 ft) above sea level, continue to function. An example of this is shown in the photograph to the right, the snowline being about 100 m (328 ft) above sea level. Absolute temperature extremes recorded at Rothamsted Research Station, 5 miles (8 km) south south east of Luton town centre and at a similar elevation range from −17.0 °C (1.4 °F)[49] in December 1981 and −16.7 °C (1.9 °F) in January 1963[50] to 36.0 °C (96.8 °F) in August 2003[51] and 33.8 °C (92.8 °F) in August 1990[52] and July 2006.[53] Records for Rothamsted date back to 1901.

| Climate data for Rothamsted 1971–2000 (Weather station 5 miles (8 km) to the south of Luton) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.3 (43.3) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.0 (64.4) |

13.8 (56.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

7.2 (45.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

0.7 (33.3) |

2.3 (36.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

6.3 (43.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.4 (52.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

6.7 (44.1) |

3.3 (37.9) |

1.9 (35.4) |

5.6 (42.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 69.5 (2.74) |

47.3 (1.86) |

54.0 (2.13) |

53.1 (2.09) |

49.8 (1.96) |

60.4 (2.38) |

41.2 (1.62) |

53.6 (2.11) |

60.9 (2.40) |

74.4 (2.93) |

66.0 (2.60) |

67.6 (2.66) |

697.8 (27.47) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 55.2 | 70.6 | 107.3 | 146.7 | 194.7 | 190.2 | 203.4 | 196.5 | 142.2 | 112.2 | 70.2 | 48.1 | 1,537.2 |

| Source: Met Office[54] | |||||||||||||

Demography

The United Kingdom Census 2011 showed that the borough had a population of 203,201,[55] a 10.2% increase from the previous census in 2001, when Luton was the 27th[56] largest settlement in the United Kingdom. In 2011, 46,756 were aged under 16, 145,208 were 16 to 74, and 11,237 were 75 or over.[57] The latest population figure for the borough is 226,973 (2022).[5]

| Population since 1801 – Source: A Vision of Britain through Time[58] | ||||||||||||||

| Year | 1801 | 1851 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population Luton | 2,985 | 11,067 | 31,981 | 49,315 | 57,378 | 66,762 | 84,516 | 106,999 | 132,017 | 162,928 | 163,208 | 174,567 | 184,390 | 203,201 |

Local inhabitants are known as Lutonians.

Ethnicity

Religion in Luton (2011 census)

Luton has seen several waves of immigration. In the early part of the 20th century, there was internal migration of Irish and Scottish people to the town. These were followed by Afro-Caribbean and Asian immigrants. More recently immigrants from other European Union countries have made Luton their home. As a result of this Luton has a diverse ethnic mix, with a significant population of Asian descent, mainly Pakistani 29,353 (14.4%) and Bangladeshi 13,606 (6.7%).[59]

Since the 2011 census, Luton has become one of three white British-minority towns in the United Kingdom. It was announced in a report based on the census figures that along with Leicester and Slough, Luton was one of three towns outside London where the indigenous population was now a minority, making up only 45% of Luton's population. However, the town still has a white majority when non-British whites such as the Irish and Eastern Europeans are included[59]. Of note, 81% of the population of Luton still define themselves as British, despite the majority of its residents being from a foreign ethnic background.[60]

| Luton: Ethnicity: 2011 Census[59] | |||||||||||||

| Ethnic group | Population | % | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 111,079 | 54.6 | |||||||||||

| Mixed | 8,281 | 4.1 | |||||||||||

| Asian or Asian British | 60,952 | 30.0 | |||||||||||

| Black or Black British | 19,909 | 9.8 | |||||||||||

| Other Ethnic Group | 2.980 | 1.5 | |||||||||||

| Total | 203,201 | 100 | |||||||||||

Religion

In the ten-year period since the United Kingdom Census 2001, the percentage of inhabitants in Luton reporting being Christian fell from 60 to 47%. Meanwhile, those reporting being Muslim increased from 15 to 25%.[61][62]

| Religion | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| Christian | 96,271 | 46.4 |

| Muslim | 51,992 | 25.6 |

| Hindu | 6,749 | 1.0 |

| Sikh | 2,347 | 1.0 |

| Buddhist | 652 | 0.3 |

| Jewish | 326 | 0.2 |

| Other | 898 | 0.4 |

| No religion | 33,594 | 16.5 |

| Religion not stated | 12,373 | 6.1 |

Luton has been identified as a "centre of extremism",[63] "hotbed of terror",[64][65] "epicentre of the global clash of civilisations",[66] and "remarkable breeding ground for both Islamist and far-right extremism".[67][68][69][70] Banned Islamic extremist groups such as Al-Muhajiroun, Al Ghurabaa, The Saviour Sect and Islam4UK led by Anjem Choudary[71] were based there before being proscribed for glorifying terrorism.[72][73][74] The founder of the English Defence League is from Luton, and the EDL itself originated from a group known as the "United Peoples of Luton".[75] A terrorist group known as the "Luton cell" is believed to have masterminded the 2010 Stockholm bombings[76] and had plans to blow up Heathrow Airport, the London Underground and other high profile targets.[77] A number of Lutonians, including entire families have left for the caliphate of Isis – most notoriously the Mannan family of 12 including a one-year-old baby.[78][79]

However, many residents say that the numbers of extremists, both Muslims and far-right, are small.[80] Inayat Bunglawala of the Muslim Council of Britain lives in Luton, and a local representative of Churches Together described "the reality of life in the town" as "a healthy interaction between people of different faiths".[80]

According to a leaked secret intelligence report, of the "some thousands" of militants in Britain "the main extremist concentrations are in London, Birmingham, with significant extremist networks in the South East, notably Luton,"[81] planning mass-casualty attacks in Britain.[82]

In October 2001, 3 men from Luton who joined mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan were among the first UK casualties of war on terrorism.[83][84] One of the four terrorists convicted for the 2004 foiled fertilizer bomb plot as well as the suspected mastermind were from Luton.[85][86][87] One month latter a group of men from Luton were jailed over plans to bomb the Luton Army Reserve Centre.[88]

The 7/7 bombers, who killed 52 people on London’s transport routes in 2005, convened in Luton before taking the trains from there to London.[89]

In June 2007, Abdul Aziz Jalil of Luton was one of a group of seven jailed for involvement in plotting terrorist atrocities such as a radioactive "dirty bomb", hijacking a train and blowing up a petrol tanker in a series of co-ordinated attacks, attacking Tube trains under the Thames, to flood the tunnel, and the Heathrow Express.[90][91] In April 2007 Salahuddin Amin of Luton, was jailed for conspiring to unleash a fertiliser bomb.[92][93]

A Muslim protest in March 2009 against soldiers returning from the Iraq War was followed by a counter-demonstration opposing sharia law in the United Kingdom. In January 2010, Five Luton men were convicted of using threatening, abusive or insulting words or behaviour likely to cause harassment, alarm or distress for abusive chants while protesting soldiers.[94] In 2010, Swedish student Taimour Abdulwahab blew himself up in central Stockholm after attending university in the town.[95]

According to a May 2014 Ofsted report, Olive Tree Primary School in Luton provided books that promoted fundamentalist views, such as stoning and lashing being appropriate punishments, and did not ensure that it promoted respect for the British values of democracy, the rule of law, including tolerance of people with different faiths, beliefs, cultural.[96] In July 2015, the 12 members of the Mannan family left Luton to join ISIS,[97][98] and Junead Khan of Luton was arrested for conspiring to murder a US soldier and trying to join IS.[99][100] In September 2015, Abu Rahin Aziz of Luton was killed in a US attack near Raqqa in Syria, after skipping bail for an assault on a football fan.[101] In Dec. 2015, police uncovered an Luton Islamist cell encouraging people to support Islamic State terrorists and urging young men and children to fight the West.[102]

In Jan 2016, two men were convicted for supporting ISIS, one of whom was also convicted for possessing information “likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism.”[103] It was also uncovered that he'd been grooming his young children for jihad as well.[104] Around the same time, Britain First carried out a "Christian patrol" in Luton,[105] and the patrols leaders were arrested by police on suspicion of wearing a political uniform and banned from entering Luton under bail conditions.[106] In may 2016, Junead Khan of Luton was jailed for life, for plotting to kill US personnel outside an air base and preparing to go to Syria to join so-called Islamic State (IS).[107][108] In August 2016, 3 Luton men who praised the Charlie Hebdo attack were found guilty of "infecting the young minds of children" encouraging children to join Isis.[109][110]

In February 2017, Five men were convicted of organizing and delivering terrorist speeches in Luton in 2015.[111][112][113] Khalid Masood (born Adrian Ajao), who carried out the 2017 Westminster attack lived in Luton from 2009 to 2013.[114] Following the 2017 Buckingham Palace incident, Mohiussunnath Chowdhury of Luton was charged with preparing an act of terrorism.[115] According to a November 2017 Ofsted report, Olive Tree Primary School in Luton provided inappropriate books were found in the school’s library that did not promote British values, written by an author who is banned from entering, or has been expelled from, several countries, including Britain; despite the school having claimed that they were removed following an inspection in May.[116][117]

Economic activity

Of the town's working population (classified 16–74 years of age by the Office for National Statistics), 63% are employed. This figure includes students, the self-employed and those who are in part-time employment. 11% are retired, 8% look after the family or take care of the home and 5% are unemployed.[118]

Economy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2009) |

Luton's economy has, traditionally been focused on several different areas of industry including Car Manufacture, engineering and millinery. However, today, Luton is moving towards a service based economy mainly in the retail and the airport sectors, although there is still a focus on light industry in the town.

Notable firms with headquarters in Luton include:

- EasyJet – head office (originally EasyLand, later moved into Hangar 89[119]) and main base at London Luton Airport

- Impellam Group – headquarters at Capability Green[120]

- Monarch Airlines – headquarters at Luton Airport (Prospect House)[121]

- TUI UK (Thomson Holidays and Thomson Airways) – travel (Wigmore House)[122][123]

- Vauxhall Motors – headquarters (Griffin House)[124]

Notable firms with offices in Luton include:

- Anritsu – electronics[125]

- AstraZeneca – pharmaceuticals[126]

- Selex ES – aerospace[127]

- Ernst & Young – accountants[128]

- Whitbread – hospitality[129]

Shopping

The main shopping area in Luton is centred on the Mall Luton. Built in the 1960s/1970s and opened as an Arndale Centre, construction of the shopping centre led to the demolition of a number of the older buildings in the town centre including the Plait Halls (a Victorian covered market building with an iron and glass roof). Shops and businesses in the remaining streets, particularly in the roads around Cheapside and in High Town, have been in decline ever since. George Street, on the south side of the Arndale, was pedestrianised in the 1990s.

The shopping centre had some construction and re-design work done to it over the 2011/12 period and now has a new square used for leisure events, as well as numerous new food restaurants such as Toby's Carvery and Costa Coffee.

Contained within the main shopping centre is the market, which contains butchers, fishmongers, fruit and veg, hairdressers, tattoo parlours, ice cream, flower stall, T-shirt printing and the markets original sewing shop for clothes alterations and repairs as well as eating places.

Another major shopping area is Bury Park where there are shops catering to Luton's ethnic minorities.

Food and drink

Luton has a diverse selection of restaurants – English, Italian, Chinese, Indian, Caribbean, Thai and Malaysian to name a few. No area of the town is specifically restaurant-orientated, but in some areas (such as Bury Park) there is a concentration of Asian restaurants.

There are pubs and clubs in the town centre, a number of which cater for the student population; however, a number of traditional pubs remain.

Principal employers

According to the Luton Borough Council,[130] the principal employers in the town are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Luton Borough Council | 8,000+ |

| 2 | Luton and Dunstable University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 4,000+ |

| 3 | Aircraft Service International Group | 1,000–1,999 |

| 3 | Carlisle Security Services | 1,000–1,999 |

| 5 | EasyJet | 1,000–1,999 |

| 6 | Menzies Aviation | 1,000–1,999 |

| 7 | Randstad | 1,000–1,999 |

| 8 | TUI | 1,000–1,999 |

| 9 | University of Bedfordshire | 1,000–1,999 |

Transport

Luton is situated less than 30 miles north of the centre of London, giving it good links with the City and other parts of the country via the motorway network Luton has two railway stations, Luton and Luton Airport Parkway that are served by East Midlands Trains and Thameslink services. Luton is also home to London Luton Airport, one of the major feeder airports for London and the southeast. A network of bus services run by Arriva Shires & Essex and Centrebus serves the urban area of Luton and Dunstable, and in 2013 a bus rapid transit route opened, the Luton to Dunstable Busway, connecting the town with the Airport.

Luton is also served by a large taxi network. As a Unitary Authority, Luton Borough Council is responsible for the local highways and public transport in the Borough and licensing of Taxis.

Education

Luton is one of the main locations of the University of Bedfordshire. A large campus of the university is in Luton town centre, with a smaller campus based on the edge of town in Putteridge Bury, an old Victorian manor house. The other main campus of the university is located in Bedford.

The town is home to Luton Sixth Form College and Barnfield College. Both have been awarded Learning & Skills Beacon Status by the Department for Children, Schools and Families.[131][132]

Luton's schools and colleges had also been earmarked for major investment in the government scheme Building Schools for the Future programme, which intends to renew and refit buildings in institutes across the country. Luton is in the 3rd wave of this long term programme with work intending to start in 2009.[133] Some schools were rebuilt before the programme was scrapped by the coalition government.

There are 98 educational institutes in Luton – seven nurseries, 56 primary schools (9 voluntary-aided, 2 Special Requirements), 13 secondary schools (1 voluntary-aided, 1 Special Requirements), four further educational institutes and four other educational institutes.[134]

Culture and leisure

Sport

Luton is the home town of Luton Town Football Club who currently play in the Football League 2,[135] Their nickname, "The Hatters", dates back to when Luton had a substantial millinery industry. The club began the 2008/09 season with a thirty-point deficit, and were consequently relegated from the Football League to the Conference Premier on 13 April 2009.[4] However, Luton did win the Football League Trophy that year in front of 42,000 Luton fans at Wembley, despite being the lowest placed team in the competition for the whole season, Conference Premier after failing to win automatic promotion to Football League Two during the 2009–10, 2010–11 and 2011–12 seasons. Luton were beaten 2–0 on aggregate by York City in the semi finals of the playoffs, and therefore failed to progress to the final at Wembley Stadium. The following season Luton progressed to the final of the playoffs, losing to Wimbledon on penalties. In 2011–12 once again the team reached the final of the play-offs, only to lose 2–1 to York. Luton were promoted back to the football league as champions of the Conference in 2014.

Bedfordshire County Cricket Club is based at Wardown Park and is one of the county clubs which make up the Minor Counties in the English domestic cricket structure, representing the historic county of Bedfordshire and competing in the Minor Counties Championship and the MCCA Knockout Trophy.

Speedway racing was staged in Luton in the mid-1930s.

The town has three rugby union clubs – Stockwood Park Rugby Club who play in Midlands 3 SE, Luton Rugby Club who play in London 1 North, and Vauxhall Motors RFC who do not currently play in the RFU league structure.

Wardown Park

Wardown Park is situated on the River Lea in Luton. The park has sporting facilities, is home to the Wardown Park Museum and contains formal gardens. The park is located between Old Bedford Road and the A6, New Bedford Road and is within walking distance of the town centre.[136]

Stockwood Park

Stockwood Park is a large municipal park near Junction 10 of the M1. Located in the park is Stockwood Discovery Centre a free museum that houses the Mossman Collection and Luton local social history, archaeology and geology. There is an athletics track, an 18-hole golf course, several rugby pitches and areas of open space.

The park was originally the estate and grounds to Stockwood house, which was demolished in 1964.

Carnival

Luton International Carnival is the largest one-day carnival in Europe. It usually takes place on the late May Bank Holiday. Crowds can reach 150,000[137] on each occasion.

The procession starts at Wardown Park and makes its way down New Bedford Road, around the town centre via St George's Square, back down New Bedford Road and finishes back at Wardown Park. There are music stages and stalls around the town centre and at Wardown Park.

Luton is home to the UK Centre for Carnival Arts (UKCCA), the country's first purpose-built facility of its kind.[138]

Due to budget cuts, the most recent carnival was run on a significantly smaller scale, with approximately one third of the typical attendance – most of the attendees were residents of the Luton area.[139]

Luton St. Patrick's Festival

The festival celebrating the patron saint of Ireland and organised by Luton Irish Forum, St Patrick, is held on the weekend nearest to 17 March.[140] In its 15th year in 2014,[141] the festival includes a parade, market stalls and music stands as well as Irish themed events.[142]

Imagine Luton Festival

Imagine Luton is a new celebratory outdoor arts festival taking place throughout Luton Town Centre, bringing the streets to life with amazing interactive theatre, circus, dance and music performances, free for all the family. Taking place on the last weekend of June each year, the festival showcases worldclass outdoor acts alongside homegrown talent, supporting local artists through commissions each year.

Theatre

Luton is home to the Library Theatre, a 238-seat theatre located on the 3rd floor of the town's Central Library. The theatre's programme consists of local amateur dramatic societies, pantomime, children's theatre (on Saturday mornings) and one night shows of touring theatre companies.[143]

Luton is also home to the Hat Factory, originally as its name suggests, this arts centre was in fact a real hat factory. The Hat Factory is a combined arts venue in the centre of Luton. It opened in 2003 and since then has been the area’s main provider of contemporary theatre, dance and music. The venue provides live music, club nights, theatre, dance, films, children's activities, workshops, classes and gallery exhibitions.

Museums

Wardown House

Wardown House Museum and Gallery, previously known as Luton Museum and Art Gallery, is housed in a large Victorian mansion in Wardown Park on the outskirts of the town centre. The museum collection focusses on the traditional crafts and industry of Luton and Bedfordshire, notably lace-making and hat-making. There are samples of local lace from as early as the 17th century.

Stockwood Discovery Centre

Based in Stockwood Park, Luton, the collection of rural crafts and trades held at Stockwood Discovery Centre was amassed by Thomas Wyatt Bagshawe, who was a notable local historian and a leading authority on folk life. Bagshawe was born in Dunstable in 1901 and became a director of the family engineering firm.

The collection only contains examples from Bedfordshire and the borders of neighbouring counties, giving the collection a very strong regional identity.

Mossman Collection

The Mossman Carriage collection is held at Stockwood Park, Luton and is the largest and most significant vehicle collection of its kind in the country, including originals from the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.

The Mossman collection of horse-drawn vehicles was given to Luton Museum Service in 1991. It illustrates the development of horse-drawn road transport in Britain from Roman times up until the 1930s.

Local attractions

| Key | |

| Abbey/Priory/Cathedral | |

| Accessible open space | |

| Amusement/Theme Park | |

| Castle | |

| Country Park | |

| English Heritage | |

| Forestry Commission | |

| Heritage railway | |

| Historic House | |

| Places of Worship | |

| Museum (free/not free) | |

| National Trust | |

| Theatre | |

| Zoo | |

Dunstable Downs

Dunstable Downs Chiltern Hills

Chiltern Hills Leagrave Park

Leagrave Park Leighton Buzzard Light Railway

Leighton Buzzard Light Railway Galley and Warden Hills Nature Reserve

Galley and Warden Hills Nature Reserve The Hat Factory

The Hat Factory Luton Hoo

Luton Hoo Someries Castle

Someries Castle Stockwood Discovery Centre

Stockwood Discovery Centre Stockwood Park

Stockwood Park Wardown Park

Wardown Park Wardown Park Museum

Wardown Park Museum Waulud's Bank

Waulud's Bank Whipsnade Tree Cathedral

Whipsnade Tree Cathedral Whipsnade Zoo

Whipsnade Zoo Woburn Safari Park

Woburn Safari Park Woodside Farm and Wildfowl Park

Woodside Farm and Wildfowl Park Wrest Park

Wrest Park

Twin towns

Luton participates in international town twinning; its partners[144][145] are:

| Country | Place | County / District / Region / State | Date | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Bergisch Gladbach | North Rhine-Westphalia | 1956 | ||

| France | Bourgoin-Jallieu[145] | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 1956 | ||

| Sweden | Eskilstuna | Södermanland | 1949 | ||

| Germany | Berlin-Spandau | Berlin | 1959 | ||

| Germany | Wolfsburg | Lower Saxony | 1950 | ||

Media

Newspapers

- Luton News, published every Wednesday

- Luton Herald & Post, a free weekly newspaper distributed every Thursday

Radio

- BBC Three Counties Radio, the local BBC station, broadcasts from its office in Dunstable to Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire.[146]

- Heart 97.6 a formally independent local station, broadcast from Milton Keynes.

- Diverse FM[147] began broadcasts in April 2007 having been awarded a community radio licence from Ofcom.

- Radio LaB (formerly Luton FM), the university's radio station, began broadcasting full-time in 2010 having been awarded a community radio licence from Ofcom.

- In addition, Radio Ramadhan used to broadcast during the month of Ramadan until Inspire FM, a full-time community radio station, broadcasting on 105.1 FM, became available in 2010.

Television

- Television Luton falls at the cross over point between the two regions of Carlton/LWT (ITV London) and Anglia Television (ITV Anglia) which transmits from Norwich. Coverage for most Luton Town FC games and highlights is usually shown on BBC London news and on BBC 1 London's Football League show

- Days Like These, the British re-make of the popular American sitcom That '70s Show, was set in Luton.

Media references

In the TV series One Foot in the Grave there are often references to places within Luton. The script-writer David Renwick was brought up in the town.

The town was mentioned several times in the seminal sketch show Monty Python's Flying Circus. In one sketch a rather half-hearted hijacker demands that a plane headed for Cuba be diverted to Luton. Luton is one of the constituencies returning a "Silly Party" victory in the famous sketch Election Night Special. In the Piranha Brothers sketch Spiny Norman lived in a hangar at Luton Airport, which the brothers destroy with an atomic bomb, causing the police to "finally sit up and take notice". A 1976 episode of the sci-fi series Space: 1999 was called "The Rules of Luton", inspired by the town name. The well known comedian Eric Morecambe frequently made references to Luton Town FC, due to him being a former chairman of the club, as well as living in close proximity to Luton in Harpenden.

Lutonians

People who were born in Luton or are associated with the town.

By birth

- Mick Abrahams, guitarist for Jethro Tull

- Jordan Thomas, World and European Karate Champion

- Tony Bignell, actor/singer

- David Arnold, composer

- Charles Bronson, prisoner

- Emily Atack, actress

- Keshi Anderson, footballer

- John Badham, film director

- Lewis Baker, footballer [citation needed]

- Clive Barker, sculptor and artist

- Jonathan Barnbrook, graphic designer, typographer

- Leon Barnett, footballer

- Kevin Blackwell, goalkeeper, football manager

- Dean Brill, footballer

- Clive Bunker, drummer for Jethro Tull

- Danny Cannon, screenwriter, director and producer

- Ian Cashmore, actor

- Gerald Anthony Coles, artist

- Natasha Collins, actress and TV presenter

- Steve Dillon, comic artist

- Kerry Dixon, footballer

- Stacey Dooley, journalist and television presenter

- Jonathan Edwards, footballer

- Simon Fenton, actor

- Kevin Foley, footballer

- Sean Gallagher, actor

- Liam George, footballer

- Tommy Robinson, Political Activist

- John Hagan, 8th master chief petty officer, US Navy

- Arthur Hailey, novelist

- Neil Halstead, musician

- Jaymi Hensley, singer of Union J

- Nadiya Hussain, winner of The Great British Bake Off

- Neil Jackson, actor

- Stephen Kelman, novelist

- Ronnie Lee, founder of the Animal Liberation Front

- Stuart Lewis-Evans, Formula One driver

- Sir Frederick Mander, General Secretary of the NUT

- Monty Panesar cricketer

- John Payne, musician

- Phil Read, motorcycle racer

- David Renwick, scriptwriter

- Stu Riddle, footballer

- Vaughan Savidge, announcer

- Billy Schwer, boxer

- Andy Selway, drummer

- Gavin Shuker, Labour party politician

- Junior Simpson, comedian

- Zena Skinner, TV chef and author

- Will Smith, cricketer

- Paul Sinha, one of the Chasers on The Chase

- David Stoten, artist

- Mark Titchner, artist

- UK Decay, band

- Jamie Woolford, musician for The Stereo, Animal Chin and Let Go, music producer

- Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, political activist

- Paul Young, singer

By association

- Ian Anderson, leader of British rock band Jethro Tull[148]

- Stefan Bailey, footballer

- Rodney Bewes, actor

- Mo Chaudry, entrepreneur

- Diana Dors, actress

- Ian Dury, singer

- Danny Dyer, actor

- John Hegley, poet

- Hilda Hewlett, UK's first female pilot

- Sir Alec Jeffreys, geneticist

- Sarfraz Manzoor, author and columnist, The Guardian

- Elizabeth Price, artist

- Eric Morecambe, entertainer

- Lee Ross, actor

- Colin Salmon, actor

- Edward Tudor-Pole, singer and actor

- Kenneth Williams, actor

- Richard Wiseman, psychologist

See also

References

- ^ Leadership=Mayor & Cabinet

Executive=Labour - ^ Office for National Statistics

- ^ ONS estimates for total population and density in 2011 and ethnicity in 2009. See the Demography section above for further information.

- ^ "Luton". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Mid-Year Population Estimates, UK, June 2022". Office for National Statistics. 26 March 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024. Luton 226,973

- ^ "Table PHP01 2011 Census: Usual residents ... wards in England and Wales;". 2011 Census: population and household estimates for Wards and Output Areas in England and Wales. Office for National Statistics. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2013.. Dunstable wards 36,253. Houghton Regis wards 17,283.

- ^ "Luton – the town: Cultural diversity". Our location. University of Bedfordshire. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ^ Dyer, Stygall & Dony (1964), p. 20

- ^ Dyer, Stygall & Dony (1964), p. 23

- ^ "Early history of Luton". Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ Hanks, Patrick; Hodges, Flavia; Mills, A. D.; Room, Adrian (2002). The Oxford Names Companion. Oxford: the University Press. ISBN 0198605617.

- ^ a b "Hosted By Bedford Borough Council: Luton in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Hosted By Bedford Borough Council: Luton in the Dark Ages". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Domesday book record". Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ "A History of Luton".

- ^ "Hosted By Bedford Borough Council: Biscot Manor". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Hosted By Bedford Borough Council: Caddington in 1086". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "History of St Mary's Church". Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Luton Castle only lasted 15 years". Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Vauxhall history". Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ "A history hat making in Luton". Plaiting and Straw Hat Making. Luton Libraries. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Website of Luton Hoo Hotel Golf and Spa". Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ^ "Population figures for 1801, 1901 and 1901". Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ Dyer, Stygall & Dony (1964), p. 141

- ^ Dyer, Stygall & Dony (1964), p. 142

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Luton was made a borough". Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ "Formation of Luton Town". Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Hat Industry of Luton and its Buildings". The Hat Industry of Luton and its Buildings. Historic England. 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database ({{{num}}})". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ "A History of Luton". Localhistories.org. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Churchill Tanks at Vauxhall". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Deaths during WWII". Localhistories.org. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ See book Luton at War volume II, compiled by The Luton News, 2001, ISBN 1-871199-49-2

- ^ tant-car-hire.co.uk/england/luton.html Arndale opened in 1972 Archived 19 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Vauxhall closure". BBC News. 21 March 2002. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ St Georges Square on Luton Council Site Archived 7 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Award won by St Georges Square [dead link]

- ^ "Website for the development of Power Court". Lutonpowercourt.com. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Napier Park website". Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Why do towns want to become cities?". BBC News. 22 June 2011.

- ^ "Three towns win city status for Diamond Jubilee". BBC News. 14 March 2012.

- ^ [2] Archived 9 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Luton Town Coat of Arms". Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ "Arms of Luton (England)". Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ^ Map of soil distribution in Beds Archived 29 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ISBN 1-871199-94-8

- ^ "Anomaly details for station Rothamsted, UK and index TXx: Maximum value of daily maximum temperature". Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute.

- ^ "Anomaly details for station Rothamsted, UK and index TXx: Maximum value of daily maximum temperature". Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute.

- ^ "Anomaly details for station Rothamsted, UK and index TXx: Maximum value of daily maximum temperature". Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute.

- ^ "Anomaly details for station Rothamsted, UK and index TXx: Maximum value of daily maximum temperature". Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute.

- ^ "Met Office: July 2006 – record temperatures and sunshine". Met Office.

- ^ "Rothamsted 1971–2000 averages". Met Office. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "2011 Census: Population and household estimates fact file, unrounded estimates, local authorities in England and Wales;". 2011 Census: population and household estimates for England and Wales – unrounded figures for the data published 16 July 2012. Office for National Statistics. 24 September 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ KS01 Usual resident population: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas Archived 6 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Table PP04 2011 Census: Usual resident population by single year of age, unrounded estimates, local authorities in England and Wales;". 2011 Census: population and household estimates for England and Wales – unrounded figures for the data published 16 July 2012. Office for National Statistics. 24 September 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Luton: Total Population". A Vision of Britain Through Time. Great Britain Historical GIS Project. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Local Authority by Ethnic Group". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ Philipson, Alice. "White Britons a minority in Leicester, Luton and Slough". Telegraph. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Religion breakdown". National Statistics Office. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ "Religion breakdown". National Statistics Office. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ Townsend, Mark. "After Paris, Luton wages its own battle for hearts and minds of homegrown radicals". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Swinford, Steven. "Britain's terror hotspots: raids focus on Birmingham, Luton and East London". The Telegraph. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ "Luton The HOTBED OF TERRORISM (New 2016) Documentary".

- ^ "How Luton became the epicentre of the global clash of civilisations". Independent.

- ^ Ebner, Julia. The Rage: The Vicious Circle of Islamist and Far-Right Extremism.

- ^ SMITH, SAPHORA; GARDHAM, DUNCAN. "Luton: U.K. Commuter Town With Reputation as a Jihadi Breeding Ground". NBC News. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ "This U.K. commuter town has a reputation as a jihadi breeding ground". AOL. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Dean, Lewis. "UK terror: Cardiff, Luton and Portsmouth emerge as breeding grounds for suspected extremists". International Business Times. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ SMITH, SAPHORA; GARDHAM, DUNCAN. "Luton: U.K. Commuter Town With Reputation as a Jihadi Breeding Ground". NBC News. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Lowles, Nick. "The EDL marches in Luton today. Hold your breath". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Jerome. "Luton fights back against right-wing extremists". Independent. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Travis, Alan. "Islam4UK to be banned, says Alan Johnson". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ "Is far-right extremism a threat?". BBC. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ "Hunt for mastermind behind the Sweden plot: Police believe Luton cell helped Stockholm bomber plan terror attack". The Daily mail.

- ^ McDevitt, Johnny. "Stockholm suicide bomber lived near terrorists". channel 4. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Townsend, Mark. "After Paris, Luton wages its own battle for hearts and minds of homegrown radicals".

- ^ SMITH, SAPHORA; GARDHAM, DUNCAN. "Luton: U.K. Commuter Town With Reputation as a Jihadi Breeding Ground". NBC News. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ a b Hughes, Mark (14 December 2010). "How Luton became the epicentre of the global clash of civilisations". The Independent. London. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ^ "Terrorism threat in UK 'growing'". BBC. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Rayment, Sean. "Report identifies UK terrorist enclaves". The Telegraph. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ "'Three Luton men killed in US attack'".

- ^ Harris, Paul; Bright, Martin; Wazir, Burhan. "Five Britons killed in 'jihad brigade'".

- ^ Gardham, Duncan; Malkin, Bonnie. "Fertiliser bombers jailed for at least 95 years". The Telegraph. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Cardwell, Niki. "Is Luton a breeding ground for terrorists?". BBC. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ McDevitt, Johnny. "Stockholm suicide bomber lived near terrorists". Channel 4. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ "Luton terror plot: four jailed over plan to bomb army centre". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ SMITH, SAPHORA; GARDHAM, DUNCAN. "Luton: U.K. Commuter Town With Reputation as a Jihadi Breeding Ground". NBC News. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Steele, John. "Al-Qa'eda bomb plot gang jailed for 136 years".

- ^ "UK al-Qaeda cell members jailed".

- ^ "Profile: Salahuddin Amin". BBC.

- ^ "Did you know terrorist Amin?".

- ^ "Five Luton men found guilty after abusive chants at soldiers".

- ^ SMITH, SAPHORA; GARDHAM, DUNCAN. "Luton: U.K. Commuter Town With Reputation as a Jihadi Breeding Ground". NBC News. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ "Books 'promoting stoning' found at Olive Tree Primary School".

- ^ Harley, Nicola. "Luton family of 12 say they were not "kidnapped"".

- ^ sylhet, mohammed. "12 of a Bangladesh origin".

- ^ "Man 'planned to kill US serviceman and tried to join IS'".

- ^ "Ofsted reports on Olive Tree Primary School".

- ^ Ross, Alice. "Death of British jihadi in July drone strike raises 'kill list' questions".

- ^ GREENWOOD, CHRIS. "'Cell called for jihad' in Luton church hall: Police believe they have smashed network that encouraged people to support ISIS". Daily Mail. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ PARRIS-LONG, ADAM. "Five years in jail for Luton men convicted of stirring up support for ISIS". Luton Today. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ GARDHAM, DUNCAN; WAHID, OMAR. "Age SIX and groomed for jihad in British suburbia: Shocking image of UK extremism, taken by little boy's Muslim convert father". Daily Mail. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ Piggott, Mark. "Luton: 'Britain First' video showing group walking through Muslim area with crosses goes viral".

- ^ Wright, Paul. "Britain First: Leaders Paul Golding and Jayda Fransen arrested for 'wearing political uniforms'".

- ^ "US air base attack plot: British man Junead Khan jailed". BBC.

- ^ "Delivery driver jailed for planning terror attack on US soldier in Britain". The Guardian.

- ^ "Three men 'infected young minds' with support for Islamic State".

- ^ Watkinson, William. "3 Luton men who praised Charlie Hebdo attack found guilty of encouraging children to join Isis".

- ^ "Luton terror gang jailed for more than 20 years". Tuton Today.

- ^ RICHARD, SPILLETT; GARDHAM, DUNCAN. "Five members of hate preacher Anjem Choudary's inner circle are jailed for drumming up support of ISIS after one ranted about '40 trucks of explosives in Oxford Street'".

- ^ Swann, Steve. "Islamic State supporters jailed after undercover police operation".

- ^ "Westminster attack: police scramble to piece together past of London killer". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Dearden, Lizzie. "Buckingham Palace attack: Uber driver Mohiussunnath Chowdhury appears in court charged with sword attack".

- ^ "Ofsted reports on Olive Tree Primary School".

- ^ Turner, Camilla. "Islamic primary school had books written by banned extremist, Ofsted report finds".

- ^ "Employment statistics". National Office of Statistics. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ "New headquarters for easyJet at London Luton Airport Archived 28 January 2010 at WebCite." Easyjet. Retrieved on 27 September 2009.

- ^ "Impellam Group - Company Contacts". Investors.impellam.com. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ "customer services & other faqs." Monarch Airlines. Retrieved on 27 September 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us." TUI UK & Ireland. Retrieved on 4 January 2011. "Wigmore House Wigmore Lane Luton Bedfordshire LU2 9TN"

- ^ "Luton." Thomson UK. Retrieved on 27 September 2009.

- ^ "Corporate contact information Archived 30 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine." Vauxhall Motors. Retrieved on 2 September 2009.

- ^ "Contact US (Test and Measurement)- Anritsu Europe". Anritsu.com. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ "Working with UK Healthcare Professionals". Astrazeneca.co.uk. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Ernst and Young Locations". Ey.com. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Contact Us". Whitbread.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Major Employers in Luton 2014

- ^ "Barnfield Newsletter". Communiqueonline.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Luton Sixth Form College". Archived from the original on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "L2G Building for the Future Programme details". Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- ^ "LEA School List". Luton Borough Council. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Luton Town homepage". Archived from the original on 4 December 2003. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Luton Council website". Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Luton Carnival Coverage on the BBC". Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Beds Herts and Bucks – Why Don't You – Luton's turning green!". BBC. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Luton Irish Forum – St patrick's festival" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ 4 March 2008 15:37. "St Patrick's Day party is coming to Luton". Luton Today. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Shout Luton Theatre Guide". Archived from the original on 24 June 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Town twinning". Luton Borough Council. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "BBC Three Counties Radio". Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "Diverse FM". Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ Wiser, Carl, "Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull" (interview), Songfacts, n.d. Anderson talked in the interview of having, in late 1967, a day job cleaning Luton's Ritz Cinema. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

Bibliography

External links

Luton travel guide from Wikivoyage

Luton travel guide from Wikivoyage- Luton Borough Council YouTube channel

- Luton On Sunday: News feed