Pandemic: Difference between revisions

Marchino61 (talk | contribs) m →Definition: transmissible is usually used in a medical context, not transmittable |

Robertpedley (talk | contribs) /* Diseases / alphabetical order |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 171: | Line 171: | ||

HIV originated in Africa, and spread to the United States via Haiti between 1966 and 1972.<ref>{{cite web |date=30 October 2007 |title=Analysis clarifies route of AIDS |url=http://articles.latimes.com/2007/oct/30/science/sci-aids30 |access-date=6 July 2014 |work=Los Angeles Times |vauthors=Chong JR}}</ref> [[AIDS]] is currently a pandemic in Africa, with infection rates as high as 25% in some regions of southern and eastern Africa. In 2006, the HIV prevalence among pregnant women in [[South Africa]] was 29%.<ref>{{cite web |date=2006 |title=The South African Department of Health Study |url=http://www.avert.org/safricastats.htm |access-date=26 August 2010 |publisher=Avert.org}}</ref> Effective education about safer sexual practices and [[bloodborne infection]] precautions training have helped to slow down infection rates in several African countries sponsoring national education programs.{{citation needed|date=March 2020}} There were an estimated 1.5 million new infections of [[HIV/AIDS]] in 2020. {{As of|2021}} there have been about a total of 40.1 million deaths related to HIV/AIDS since the epidemic started.<ref>{{cite web |title=Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2021 fact sheet |url=https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet |access-date=2021-07-01 |website=www.unaids.org |publisher=UNAIDS |language=en}}</ref> |

HIV originated in Africa, and spread to the United States via Haiti between 1966 and 1972.<ref>{{cite web |date=30 October 2007 |title=Analysis clarifies route of AIDS |url=http://articles.latimes.com/2007/oct/30/science/sci-aids30 |access-date=6 July 2014 |work=Los Angeles Times |vauthors=Chong JR}}</ref> [[AIDS]] is currently a pandemic in Africa, with infection rates as high as 25% in some regions of southern and eastern Africa. In 2006, the HIV prevalence among pregnant women in [[South Africa]] was 29%.<ref>{{cite web |date=2006 |title=The South African Department of Health Study |url=http://www.avert.org/safricastats.htm |access-date=26 August 2010 |publisher=Avert.org}}</ref> Effective education about safer sexual practices and [[bloodborne infection]] precautions training have helped to slow down infection rates in several African countries sponsoring national education programs.{{citation needed|date=March 2020}} There were an estimated 1.5 million new infections of [[HIV/AIDS]] in 2020. {{As of|2021}} there have been about a total of 40.1 million deaths related to HIV/AIDS since the epidemic started.<ref>{{cite web |title=Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2021 fact sheet |url=https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet |access-date=2021-07-01 |website=www.unaids.org |publisher=UNAIDS |language=en}}</ref> |

||

=== |

=== Pandemics in history === |

||

{{See also|List of epidemics and pandemics}} |

|||

{{Expand section|[[Dengue fever]] and [[Chikungunya]]|date=June 2020}} |

|||

[[File:FlorentineCodex BK12 F54 smallpox.jpg|thumb|Aztecs dying of smallpox, ''[[Florentine Codex]]'' (compiled 1540–1585)]] |

[[File:FlorentineCodex BK12 F54 smallpox.jpg|thumb|Aztecs dying of smallpox, ''[[Florentine Codex]]'' (compiled 1540–1585)]] |

||

[[File:The Triumph of Death P001393.jpg|thumb|upright=1.3|[[Pieter Brueghel the Elder|Pieter Bruegel]]'s ''[[The Triumph of Death]]'' (c. 1562) reflects the social upheaval and terror that followed the plague, which devastated medieval Europe.]] |

[[File:The Triumph of Death P001393.jpg|thumb|upright=1.3|[[Pieter Brueghel the Elder|Pieter Bruegel]]'s ''[[The Triumph of Death]]'' (c. 1562) reflects the social upheaval and terror that followed the plague, which devastated medieval Europe.]] |

||

| Line 182: | Line 182: | ||

* [[Antonine Plague]] (165 to 180 AD): Possibly measles or smallpox brought to the Italian peninsula by soldiers returning from the Near East, it killed a quarter of those infected, up to five million in total.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/4381924.stm Past pandemics that ravaged Europe]. ''BBC News'', 7{{nbsp}}November. 2005</ref> |

* [[Antonine Plague]] (165 to 180 AD): Possibly measles or smallpox brought to the Italian peninsula by soldiers returning from the Near East, it killed a quarter of those infected, up to five million in total.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/4381924.stm Past pandemics that ravaged Europe]. ''BBC News'', 7{{nbsp}}November. 2005</ref> |

||

* [[Plague of Cyprian]] (251–266 AD): A second outbreak of what may have been the same disease as the Antonine Plague killed (it was said) 5,000 people a day in [[Rome]].{{Citation needed|date=November 2021}} |

* [[Plague of Cyprian]] (251–266 AD): A second outbreak of what may have been the same disease as the Antonine Plague killed (it was said) 5,000 people a day in [[Rome]].{{Citation needed|date=November 2021}} |

||

* [[Plague of Justinian]] (541 to 549 AD): |

* [[Plague of Justinian]] (541 to 549 AD): Also known as the ''FIrst Plague Pandemic''. This epidemic started in [[Egypt]] and reached [[Constantinople]] the following spring, killing (according to the Byzantine chronicler [[Procopius]]) 10,000 a day at its height, and perhaps 40% of the city's inhabitants. The plague went on to eliminate a quarter to half the [[human population]] of the known world and was identified in 2013 as being caused by [[bubonic plague]].<ref>{{cite web |date=May 20, 2013 |title=Modern lab reaches across the ages to resolve plague DNA debate |url=http://phys.org/news/2013-05-modern-lab-ages-plague-dna.html |website=phys.org}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cambridge.org/us/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=0521846390&ss=fro |title=Cambridge Catalogue page 'Plague and the End of Antiquity' |publisher=Cambridge.org |access-date=26 August 2010}}</ref><ref>[http://www.speakeasy-forum.com/lofiversion/index.php/t18579.html Quotes from book "Plague and the End of Antiquity"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110716114235/http://www.speakeasy-forum.com/lofiversion/index.php/t18579.html |date=16 July 2011}} Lester K. Little, ed., ''Plague and the End of Antiquity: The Pandemic of 541–750'', Cambridge, 2006. {{ISBN|0-521-84639-0}}</ref> |

||

* [[Black Death]] (1331 to 1353): The total number of deaths worldwide is estimated at 75 to 200 million |

* [[Black Death]] (1331 to 1353): Also known as the ''Second Plague Pandemic.'' The total number of deaths worldwide is estimated at 75 to 200 million. Starting in Asia, the disease reached the Mediterranean and western Europe in 1348 (possibly from Italian merchants fleeing fighting in [[Crimea]]) and killed an estimated 20 to 30 million Europeans in six years;<ref>[http://www.medhunters.com/articles/deathOnAGrandScale.html Death on a Grand Scale]. ''MedHunters.''</ref> a third of the total population,<ref>Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, in ''[[L'Histoire]]'' No. 310, June 2006, pp. 45–46, say "between one-third and two-thirds"; Robert Gottfried (1983). "Black Death" in ''[[Dictionary of the Middle Ages]]'', volume 2, pp. 257–267, says "between 25 and 45 percent".</ref> and up to a half in the worst-affected urban areas.<ref>{{cite EB1911 |wstitle=Plague |volume=21 |pages=693–705}}</ref> It was the first of a cycle of European [[Second plague pandemic|plague epidemics]] that continued until the 18th century;<ref>{{cite web |url=http://urbanrim.org.uk/plague%20list.htm |title=A List of National Epidemics of Plague in England 1348–1665 |publisher=Urbanrim.org.uk |date=4 August 2010 |access-date=26 August 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090508010316/http://urbanrim.org.uk/plague%20list.htm |archive-date=8 May 2009 |url-status=dead }}</ref> there were more than 100 plague epidemics in Europe during this period, <ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/may/16/health.books |title=Black Death blamed on man, not rats |newspaper=The Observer | vauthors = Revill J |date= 16 May 2004|access-date=3 November 2008 | location=London}}</ref> including the [[Great Plague of London]] of 1665–66 which killed approximately 100,000 people, 20% of London's population.<ref>[http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/contagion/plague.html The Great Plague of London, 1665]. ''The Harvard University Library, Open Collections Program: Contagion.''</ref> |

||

* [[1817–1824 cholera pandemic]]. Previously restricted to the [[Indian subcontinent]], the pandemic began in [[Bengal]], then spread across India by 1820. 10,000 British troops and thousands of Indians died during this pandemic.{{cn|date=February 2023}} It extended as far as China, [[Indonesia]] (where more than 100,000 people succumbed on the island of [[Java]] alone) and the [[Caspian Sea]] before receding. Deaths in the Indian subcontinent between 1817 and 1860 are estimated to have exceeded 15 million. Another 23 million died between 1865 and 1917. [[Russian Empire|Russian]] deaths during a similar period exceeded 2{{nbsp}}million.<ref>{{cite web |author=G. William Beardslee |title=The 1832 Cholera Epidemic in New York State |url=http://www.earlyamerica.com/review/2000_fall/1832_cholera_part1.html |access-date=26 August 2010 |publisher=Earlyamerica.com}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Third plague pandemic]] (1855): Starting in China, it spread into India, where 10 million people died.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/zoonotic/en/index4.html |title=Zoonotic Infections: Plague |publisher=World Health Organization |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090420003315/http://www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/zoonotic/en/index4.html |archive-date=20 April 2009 |access-date=5 July 2014}}</ref> During this pandemic, the United States saw its first outbreak: the [[San Francisco plague of 1900–1904]].<ref>[https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/dm00bu.html Bubonic plague hits San Francisco 1900–1909]. ''A Science Odyssey. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS).''</ref> Today, sporadic cases of [[sylvatic plague|plague]] still occur in the western United States.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00026077.htm|title=Human Plague—United States, 1993–1994|website=[[cdc.gov]]}}</ref> |

* [[Third plague pandemic]] (1855): Starting in China, it spread into India, where 10 million people died.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/zoonotic/en/index4.html |title=Zoonotic Infections: Plague |publisher=World Health Organization |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090420003315/http://www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/zoonotic/en/index4.html |archive-date=20 April 2009 |access-date=5 July 2014}}</ref> During this pandemic, the United States saw its first outbreak: the [[San Francisco plague of 1900–1904]].<ref>[https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/dm00bu.html Bubonic plague hits San Francisco 1900–1909]. ''A Science Odyssey. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS).''</ref> Today, sporadic cases of [[sylvatic plague|plague]] still occur in the western United States.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00026077.htm|title=Human Plague—United States, 1993–1994|website=[[cdc.gov]]}}</ref> |

||

* The 1918–1920 [[Spanish flu]] infected half a billion people<ref name="Taubenberger" /> around the world, including on remote [[Pacific islands]] and in the [[Arctic]]—killing 20 to 100 million.<ref name="Taubenberger" /><ref>{{cite web| title=Historical Estimates of World Population| url=https://www.census.gov/population/international/data/worldpop/table_history.php| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120709092946/https://www.census.gov/population/international/data/worldpop/table_history.php| url-status=dead| archive-date=9 July 2012| access-date=29 March 2013}}</ref> Most influenza outbreaks disproportionately kill the very young and the very old, but the 1918 pandemic had an unusually high mortality rate for young adults.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gagnon A, Miller MS, Hallman SA, Bourbeau R, Herring DA, Earn DJ, Madrenas J | title = Age-specific mortality during the 1918 influenza pandemic: unravelling the mystery of high young adult mortality | journal = PLOS ONE | volume = 8 | issue = 8 | pages = e69586 | year = 2013 | pmid = 23940526 | pmc = 3734171 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0069586 | bibcode = 2013PLoSO...869586G | doi-access = free }}</ref> It killed more people in 25 weeks than AIDS did in its first 25 years.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://virus.stanford.edu/uda/|title=The 1918 Influenza Pandemic|website=virus.stanford.edu}}</ref><ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20100127100727/http://www.channel4.com/news/articles/world/spanish%20flu%20facts/111285 Spanish flu facts by Channel{{nbsp}}4 News].</ref> Mass troop movements and close quarters during World War{{nbsp}}I caused it to spread and [[mutation|mutate]] faster, and the susceptibility of soldiers to the flu may have been increased by stress, [[malnourishment]] and [[chemical attack]]s.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Qureshi AI | title=Ebola Virus Disease: From Origin to Outbreak| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7zyXCgAAQBAJ&q=Ebola+Virus+Disease:+From+Origin+to+Outbreak+Adnan+1918+pandemic&pg=PA42| page=42| publisher=Academic Press| date=2016| isbn=978-0128042427}}</ref> Improved transportation systems made it easier for soldiers, sailors and civilian travelers to spread the disease.<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20131211093810/http://www.xtimeline.com/evt/view.aspx?id=65022 Spanish flu strikes during World War I], 14 January 2010</ref> |

* The 1918–1920 [[Spanish flu]] infected half a billion people<ref name="Taubenberger">{{cite journal |vauthors=Taubenberger JK, Morens DM |date=January 2006 |title=1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics |url=https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol12no01/05-0979.htm |url-status=dead |journal=Emerging Infectious Diseases |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=15–22 |doi=10.3201/eid1201.050979 |pmc=3291398 |pmid=16494711 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091006002531/http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol12no01/05-0979.htm |archive-date=6 October 2009 |access-date=7 September 2017}}</ref> around the world, including on remote [[Pacific islands]] and in the [[Arctic]]—killing 20 to 100 million.<ref name="Taubenberger" /><ref>{{cite web| title=Historical Estimates of World Population| url=https://www.census.gov/population/international/data/worldpop/table_history.php| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120709092946/https://www.census.gov/population/international/data/worldpop/table_history.php| url-status=dead| archive-date=9 July 2012| access-date=29 March 2013}}</ref> Most influenza outbreaks disproportionately kill the very young and the very old, but the 1918 pandemic had an unusually high mortality rate for young adults.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gagnon A, Miller MS, Hallman SA, Bourbeau R, Herring DA, Earn DJ, Madrenas J | title = Age-specific mortality during the 1918 influenza pandemic: unravelling the mystery of high young adult mortality | journal = PLOS ONE | volume = 8 | issue = 8 | pages = e69586 | year = 2013 | pmid = 23940526 | pmc = 3734171 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0069586 | bibcode = 2013PLoSO...869586G | doi-access = free }}</ref> It killed more people in 25 weeks than AIDS did in its first 25 years.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://virus.stanford.edu/uda/|title=The 1918 Influenza Pandemic|website=virus.stanford.edu}}</ref><ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20100127100727/http://www.channel4.com/news/articles/world/spanish%20flu%20facts/111285 Spanish flu facts by Channel{{nbsp}}4 News].</ref> Mass troop movements and close quarters during World War{{nbsp}}I caused it to spread and [[mutation|mutate]] faster, and the susceptibility of soldiers to the flu may have been increased by stress, [[malnourishment]] and [[chemical attack]]s.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Qureshi AI | title=Ebola Virus Disease: From Origin to Outbreak| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7zyXCgAAQBAJ&q=Ebola+Virus+Disease:+From+Origin+to+Outbreak+Adnan+1918+pandemic&pg=PA42| page=42| publisher=Academic Press| date=2016| isbn=978-0128042427}}</ref> Improved transportation systems made it easier for soldiers, sailors and civilian travelers to spread the disease.<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20131211093810/http://www.xtimeline.com/evt/view.aspx?id=65022 Spanish flu strikes during World War I], 14 January 2010</ref> |

||

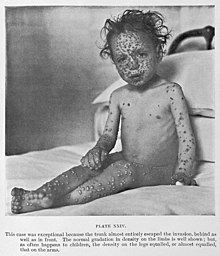

Encounters between European explorers and populations in the rest of the world often introduced epidemics of extraordinary virulence. Disease killed part of the native population of the [[Canary Islands]] in the 16th century ([[Guanches]]). Half the native population of [[Hispaniola]] in 1518 was killed by smallpox. [[Smallpox]] also ravaged Mexico in the 1520s, killing 150,000 in [[Tenochtitlán]] alone, including the emperor, and in [[Peru]] in the 1530s, aiding the European conquerors.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/smallpox_01.shtml |title=Smallpox: Eradicating the Scourge |publisher=Bbc.co.uk |date=5 November 2009 |access-date=26 August 2010}}</ref> [[Measles]] killed a further two million native Mexicans in the 17th century. In 1618–1619, smallpox wiped out 90% of the [[Massachusetts Bay]] Native Americans.<ref>[http://www.ucpress.edu/books/pages/9968/9968.ch01.html Smallpox The Fight to Eradicate a Global Scourge] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080907093641/http://www.ucpress.edu/books/pages/9968/9968.ch01.html |date=7 September 2008 }}, David A. Koplow</ref> During the 1770s, smallpox killed at least 30% of the [[Pacific Northwest]] Native Americans.<ref>Greg Lange,[http://www.historylink.org/essays/output.cfm?file_id=5100 "Smallpox epidemic ravages Native Americans on the northwest coast of North America in the 1770s"], 23 January 2003, HistoryLink.org, ''Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History'', accessed 2 June 2008</ref> Smallpox epidemics in [[North American smallpox epidemic|1780–1782]] and [[1837-38 smallpox epidemic|1837–1838]] brought devastation and drastic depopulation among the [[Plains Indians]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Houston CS, Houston S | title = The first smallpox epidemic on the Canadian Plains: In the fur-traders' words | journal = The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases | volume = 11 | issue = 2 | pages = 112–115 | date = March 2000 | pmid = 18159275 | pmc = 2094753 | doi = 10.1155/2000/782978 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Some believe the death of up to 95% of the [[Population history of indigenous peoples of the Americas|Native American population]] of the [[New World]] was caused by Europeans introducing [[Old World]] diseases such as smallpox, measles and influenza.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.pbs.org/gunsgermssteel/variables/smallpox.html |title=The Story Of ... Smallpox—and other Deadly Eurasian Germs |publisher=Pbs.org |access-date=26 August 2010}}</ref> Over the centuries, Europeans had developed high degrees of [[herd immunity]] to these diseases, while the [[indigenous peoples]] had no such immunity.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.millersville.edu/~columbus/papers/goodling.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080510163413/http://www.millersville.edu/~columbus/papers/goodling.html|url-status=dead|title=Stacy Goodling, "Effects of European Diseases on the Inhabitants of the New World"|archive-date=10 May 2008}}</ref> |

Encounters between European explorers and populations in the rest of the world often introduced epidemics of extraordinary virulence. Disease killed part of the native population of the [[Canary Islands]] in the 16th century ([[Guanches]]). Half the native population of [[Hispaniola]] in 1518 was killed by smallpox. [[Smallpox]] also ravaged Mexico in the 1520s, killing 150,000 in [[Tenochtitlán]] alone, including the emperor, and in [[Peru]] in the 1530s, aiding the European conquerors.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/smallpox_01.shtml |title=Smallpox: Eradicating the Scourge |publisher=Bbc.co.uk |date=5 November 2009 |access-date=26 August 2010}}</ref> [[Measles]] killed a further two million native Mexicans in the 17th century. In 1618–1619, smallpox wiped out 90% of the [[Massachusetts Bay]] Native Americans.<ref>[http://www.ucpress.edu/books/pages/9968/9968.ch01.html Smallpox The Fight to Eradicate a Global Scourge] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080907093641/http://www.ucpress.edu/books/pages/9968/9968.ch01.html |date=7 September 2008 }}, David A. Koplow</ref> During the 1770s, smallpox killed at least 30% of the [[Pacific Northwest]] Native Americans.<ref>Greg Lange,[http://www.historylink.org/essays/output.cfm?file_id=5100 "Smallpox epidemic ravages Native Americans on the northwest coast of North America in the 1770s"], 23 January 2003, HistoryLink.org, ''Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History'', accessed 2 June 2008</ref> Smallpox epidemics in [[North American smallpox epidemic|1780–1782]] and [[1837-38 smallpox epidemic|1837–1838]] brought devastation and drastic depopulation among the [[Plains Indians]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Houston CS, Houston S | title = The first smallpox epidemic on the Canadian Plains: In the fur-traders' words | journal = The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases | volume = 11 | issue = 2 | pages = 112–115 | date = March 2000 | pmid = 18159275 | pmc = 2094753 | doi = 10.1155/2000/782978 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Some believe the death of up to 95% of the [[Population history of indigenous peoples of the Americas|Native American population]] of the [[New World]] was caused by Europeans introducing [[Old World]] diseases such as smallpox, measles and influenza.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.pbs.org/gunsgermssteel/variables/smallpox.html |title=The Story Of ... Smallpox—and other Deadly Eurasian Germs |publisher=Pbs.org |access-date=26 August 2010}}</ref> Over the centuries, Europeans had developed high degrees of [[herd immunity]] to these diseases, while the [[indigenous peoples]] had no such immunity.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.millersville.edu/~columbus/papers/goodling.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080510163413/http://www.millersville.edu/~columbus/papers/goodling.html|url-status=dead|title=Stacy Goodling, "Effects of European Diseases on the Inhabitants of the New World"|archive-date=10 May 2008}}</ref> |

||

| Line 199: | Line 200: | ||

}}</ref> In the 20th century, the world saw the biggest increase in its [[World population|population]] in human history due to a drop in the [[mortality rate]] in many countries as a result of [[History of medicine#Modern medicine|medical advances]].<ref>{{Cite journal |jstor = 182701|title = The Origins of African Population Growth|journal = The Journal of African History|volume = 30|issue = 1|pages = 165–169| vauthors = Iliffe J |year = 1989|doi = 10.1017/S0021853700030942|s2cid = 59931797}}</ref> The [[world population]] has grown from 1.6 billion in 1900 to an estimated 6.8 billion in 2011.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/population/popclockworld.html |title=World Population Clock—U.S. Census Bureau |publisher=U.S. Census Bureau |access-date=18 November 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111118011415/http://www.census.gov/population/popclockworld.html |archive-date=18 November 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

}}</ref> In the 20th century, the world saw the biggest increase in its [[World population|population]] in human history due to a drop in the [[mortality rate]] in many countries as a result of [[History of medicine#Modern medicine|medical advances]].<ref>{{Cite journal |jstor = 182701|title = The Origins of African Population Growth|journal = The Journal of African History|volume = 30|issue = 1|pages = 165–169| vauthors = Iliffe J |year = 1989|doi = 10.1017/S0021853700030942|s2cid = 59931797}}</ref> The [[world population]] has grown from 1.6 billion in 1900 to an estimated 6.8 billion in 2011.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/population/popclockworld.html |title=World Population Clock—U.S. Census Bureau |publisher=U.S. Census Bureau |access-date=18 November 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111118011415/http://www.census.gov/population/popclockworld.html |archive-date=18 November 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

||

=== Diseases with pandemic potential === |

|||

==== Cholera ==== |

|||

{{Further|Emerging infectious disease}}In order to encourage research, a number of organisations which monitor global health have drawn up lists of diseases which may have pandemic potential; see table below.{{Efn|As of June 2023, the WHO is reviewing its list}} |

|||

{{Main|Cholera outbreaks and pandemics}} |

|||

[[File:Il cholera di Palermo del 1835.jpg|thumb|Disposal of dead bodies during the cholera epidemic in [[Palermo]] in 1835]] |

|||

Since it became widespread in the 19th century, cholera has killed tens of millions of people.<ref>[[Kelley Lee]] (2003) ''Health impacts of globalization: towards global governance''. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 131. {{ISBN|0-333-80254-3}}</ref> |

|||

* [[1817–1824 cholera pandemic]]. Previously restricted to the [[Indian subcontinent]], the pandemic began in [[Bengal]], then spread across India by 1820. 10,000 British troops and thousands of Indians died during this pandemic.{{cn|date=February 2023}} It extended as far as China, [[Indonesia]] (where more than 100,000 people succumbed on the island of [[Java]] alone) and the [[Caspian Sea]] before receding. Deaths in the Indian subcontinent between 1817 and 1860 are estimated to have exceeded 15 million. Another 23 million died between 1865 and 1917. [[Russian Empire|Russian]] deaths during a similar period exceeded 2{{nbsp}}million.<ref>{{cite web|author=G. William Beardslee |url=http://www.earlyamerica.com/review/2000_fall/1832_cholera_part1.html |title=The 1832 Cholera Epidemic in New York State |publisher=Earlyamerica.com |access-date=26 August 2010}}</ref> |

|||

* [[1826–1837 cholera pandemic]]. Reached Russia (see [[Cholera Riots]]), Hungary (about 100,000 deaths) and Germany in 1831, London in 1832 (more than 55,000 persons died in the United Kingdom),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ph.ucla.edu/EPI/snow/pandemic1826-37.html |title=Asiatic Cholera Pandemic of 1826–37 |publisher=Ph.ucla.edu |access-date=26 August 2010}}</ref> France, Canada ([[Ontario]]), and United States (New York City) in the same year,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tngenweb.org/darkside/cholera.html |title=The Cholera Epidemic Years in the United States |publisher=Tngenweb.org |access-date=26 August 2010}}</ref> and the Pacific coast of [[North America]] by 1834. It is believed that more than 150,000 Americans died of cholera between 1832 and 1849.<ref name=Cholera>[http://www.earlyamerica.com/review/2000_fall/1832_cholera_part2.html The 1832 Cholera Epidemic in New York State. p. 2]. By G. William Beardslee</ref> |

|||

* [[1846–1860 cholera pandemic]]. Deeply affected Russia, with more than a million deaths. A two-year outbreak began in England and Wales in 1848 and claimed 52,000 lives.<ref>[http://www.cbc.ca/health/story/2008/05/09/f-cholera-outbreaks.html Cholera's seven pandemics], cbc.ca, 2 December 2008</ref> Throughout Spain, cholera caused more than 236,000 deaths in 1854–55.<ref>{{Cite book | vauthors = Kohn GC | title = Encyclopedia of plague and pestilence: from ancient times to the present | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=tzRwRmb09rgC&pg=PA369 | publisher = Infobase Publishing | year = 2008 | page = 369 | isbn = 978-0-8160-6935-4 }} |

|||

</ref> It claimed 200,000 lives in Mexico.<ref>{{Cite book | vauthors = Byrne JP | title = Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A–M | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=5Pvi-ksuKFIC&pg=PA101 | publisher = ABC-CLIO | year = 2008 | page = 101 | isbn = 978-0-313-34102-1 }} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

* [[1863–1875 cholera pandemic]]. Spread mostly in Europe and Africa. At least 30,000 of the 90,000 [[Mecca]] pilgrims were affected by the disease. Cholera killed 90,000 people in Russia in 1866.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/Myadel/pandemics.htm |title=Eastern European Plagues and Epidemics 1300–1918 |publisher=kehilalinks.jewishgen.org |access-date=26 August 2010}}</ref> |

|||

* In 1866, there was an outbreak in North America. It killed some 50,000 Americans.<ref name=Cholera/> |

|||

* [[1881–1896 cholera pandemic]]. The 1883–1887 epidemic cost 250,000 lives in Europe and at least 50,000 in the Americas.<ref>{{Cite journal | vauthors = Küskü F |date= January 2021 |title=Mekteplerde Hijyen, Dezenfeksiyon ve Karantina (1876-1909) / Hygiene, Disinfection and Quarantine in the Schools (1876-1909) |url=https://www.academia.edu/79059563 |journal=Osmanlı Mektepleri (Bir Modernleşme Çabası Olarak Osmanlı Eğitiminde Yeni Arayışlar)}}</ref> Cholera claimed 267,890 lives in [[Russian Empire|Russia]] (1892);<ref>{{cite EB1911 |wstitle=Cholera |volume=6 |pages=262–267}}</ref> 120,000 in Spain;<ref>{{cite news |url=https://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9E05EED7123BE533A25753C2A9609C94619ED7CF |title=The cholera in Spain | work=New York Times |date=20 June 1890 |access-date=8 December 2008}}</ref> 90,000 in Japan and 60,000 in [[Iran|Persia]]. |

|||

* In 1892, cholera contaminated the water supply of [[Hamburg]] and caused 8,606 deaths.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Barry JM |author-link = John M. Barry|title=The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Greatest Plague in History|publisher=Viking Penguin|year=2004|isbn=978-0-670-89473-4|url=https://archive.org/details/greatinfluenzaep00john}}</ref> |

|||

* [[1899–1923 cholera pandemic]]. Had little effect in Europe because of advances in [[public health]], but Russia was badly affected again (more than 500,000 people dying of cholera during the first quarter of the 20th century).<ref>[https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/114078/cholera/253250/Seven-pandemics cholera :: Seven pandemics], Britannica Online Encyclopedia</ref> The sixth pandemic killed more than 800,000 in India. The 1902–1904 cholera epidemic claimed more than 200,000 lives in the [[Philippines]].<ref>[http://www3.wooster.edu/History/jgates/book-ch3.html John M. Gates, Ch. 3, "The U.S. Army and Irregular Warfare"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140629045949/http://www3.wooster.edu/History/jgates/book-ch3.html |date=29 June 2014 }}</ref> |

|||

* [[1961–1975 cholera pandemic|Seventh cholera pandemic (1961–present)]]. Began in [[Indonesia]], called [[El Tor]] after the new biotype responsible for the pandemic, and reached [[Bangladesh]] in 1963, India in 1964, and the [[Soviet Union]] in 1966. The pandemic thereafter reached Africa in 1971 and the Americas in 1991. As of March 2022, the World Health Organization continues to define this outbreak as a current pandemic, noting that cholera has become [[endemic]] in many countries. In 2017, WHO announced a global strategy aimed at this pandemic with the goal of reducing cholera deaths by 90% by 2030.<ref name="WHO">{{cite press release |author=<!--Not stated--> |title=Cholera factsheet |url=https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera |location=Geneva, Switzerland |publisher=[[World Health Organization]] |

|||

|date=March 30, 2022|access-date=May 4, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

==== Dengue fever ==== |

|||

Dengue is spread by several species of female mosquitoes of the Aedes type, principally ''A. aegypti''. The virus has five types; infection with one type usually gives lifelong immunity to that type, but only short-term immunity to the others. Subsequent infection with a different type increases the risk of severe complications. Several tests are available to confirm the diagnosis including detecting antibodies to the virus or its RNA. |

|||

==== Influenza ==== |

|||

{{Main|Influenza pandemic}} |

|||

[[File:Pandemie.jpg|thumb|upright]]The Greek physician [[Hippocrates]], the "Father of Medicine", first described influenza in 412{{nbsp}}BC.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://who.int/inf-pr-1999/en/pr99-11.html | title = 50 Years of Influenza Surveillance | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090501165850/http://www.who.int/inf-pr-1999/en/pr99-11.html | archive-date=1 May 2009 | work = World Health Organization }}</ref> |

|||

* The first influenza pandemic to be pathologically described [[1510 influenza pandemic|occurred in 1510]]. Since the pandemic of 1580, influenza pandemics have occurred every 10 to 30 years.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.gov.im/dhss/about/Public_Health/hp/pandemicflu/ | title = Pandemic Flu | work = Department of Health and Social Security. | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120107000431/http://www.gov.im/dhss/about/Public_Health/hp/pandemicflu/ | archive-date=7 January 2012 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Beveridge WI | date = 1977 | title = Influenza: The Last Great Plague: An Unfinished Story of Discovery | location = New York: Prodist | quote = Return of the Germs: For more than a century drugs and vaccines made astounding progress against infectious diseases. Now our best defenses may be social changes| isbn = 0-88202-118-4}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Potter CW | title = A history of influenza | journal = Journal of Applied Microbiology | volume = 91 | issue = 4 | pages = 572–579 | date = October 2001 | pmid = 11576290 | doi = 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x | s2cid = 26392163 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

* The [[1889–1890 pandemic]] was attributed to influenza at the time but more recent research suggests it may have been caused by [[human coronavirus OC43]]. Also known as Russian Flu or Asiatic Flu, it was first reported in May 1889 in [[Bukhara]], [[Uzbekistan]]. By October, it had reached [[Tomsk]] and the [[Caucasus]]. It rapidly spread west and hit North America in December 1889, South America in February–April 1890, India in February–March 1890, and Australia in March–April 1890. The [[H3N8]] and [[H2N2]] subtypes of the [[influenza A virus]] have each been identified as possible causes. It had a very high attack and [[mortality rate]], causing around a million fatalities.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/cidrap/content/influenza/panflu/biofacts/index.html | work = CIDRAP | title = Pandemic Influenza | date = 16 June 2011 }}</ref> |

|||

* The "[[Spanish flu]]", 1918–1920. First identified early in March 1918 in U.S. troops training at [[Fort Riley|Camp Funston]], [[Kansas]]. By October 1918, it had spread to become a worldwide pandemic on all continents, and eventually infected about one-third of the [[world's population]] (or ≈500 million persons).<ref name="Taubenberger" /> Unusually deadly and virulent, it persisted in pandemic form for at least two years before settling into more endemic patterns.<ref>{{Cite journal | vauthors = Chandra S, Christensen J, Likhtman S |date=November 2020 |title=Connectivity and seasonality: the 1918 influenza and COVID-19 pandemics in global perspective |journal=Journal of Global History |volume=15 |issue=3 |pages=413–414 |doi=10.1017/S1740022820000261|s2cid=228988279 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Within six months, some 50{{nbsp}}million people were dead;<ref name="Taubenberger">{{cite journal | vauthors = Taubenberger JK, Morens DM | title = 1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics | journal = Emerging Infectious Diseases | volume = 12 | issue = 1 | pages = 15–22 | date = January 2006 | pmid = 16494711 | pmc = 3291398 | doi = 10.3201/eid1201.050979 | url = https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol12no01/05-0979.htm | access-date = 7 September 2017 | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20091006002531/http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol12no01/05-0979.htm | archive-date = 6 October 2009 }}</ref> some estimates put the total number of fatalities worldwide at over twice that number.<ref>{{cite web | url = https://www.sciencedaily.com/articles/s/spanish_flu.htm | title = Spanish flu | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150325113108/http://www.sciencedaily.com/articles/s/spanish_flu.htm | archive-date=25 March 2015 | work = ScienceDaily }}</ref> About 17{{nbsp}}million died in India, 675,000 in the United States,<ref>{{cite web | url = http://1918.pandemicflu.gov/the_pandemic/index.htm | title = The Great Pandemic: The United States in 1918–1919 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20111126082941/http://1918.pandemicflu.gov/the_pandemic/index.htm | archive-date=26 November 2011 | work = U.S. Department of Health & Human Services }}</ref> and 200,000 in the United Kingdom. The virus that caused Spanish flu was also implicated as a cause of [[encephalitis lethargica]] in children.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Vilensky JA, Foley P, Gilman S | title = Children and encephalitis lethargica: a historical review | journal = Pediatric Neurology | volume = 37 | issue = 2 | pages = 79–84 | date = August 2007 | pmid = 17675021 | doi = 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.04.012 }}</ref> The virus was recently reconstructed by scientists at the [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|CDC]] studying remains preserved by the Alaskan [[permafrost]]. The [[Pandemic H1N1/09 virus|2009 pandemic H1N1 virus]] has a small but crucial structure that is similar to the Spanish flu.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/h1n1-shares-key-similar-structures-to-1918-flu-providing-research-avenues-for-better-vaccines/|title=H1N1 shares key similar structures to 1918 flu, providing research avenues for better vaccines| vauthors= Harmon K |website=Scientific American Blog Network}}</ref> |

|||

* The "[[1957–1958 influenza pandemic|Asian flu]]", 1957–58. An [[Influenza A virus subtype H2N2|H2N2]] virus was first identified in China in late February 1957 but not recognized globally until after an outbreak in [[Hong Kong]] in April.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |date=1958-12-01 |title=Symposium on the Asian Influenza Epidemic, 1957 |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine |language=en |volume=51 |issue=12 |pages=1009–1018 |doi=10.1177/003591575805101205 |issn=0035-9157 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name=":16">{{cite journal | vauthors = Murray R | title = Production and testing in the USA of influenza virus vaccine made from the Hong Kong variant in 1968-69 | journal = Bulletin of the World Health Organization | volume = 41 | issue = 3 | pages = 495–496 | date = 1969 | pmid = 5309463 | pmc = 2427701 | hdl = 10665/262478 }}</ref> From there, it spread throughout [[Southeast Asia]] and the greater continent during the spring and throughout the [[Southern Hemisphere]] during the middle months of the year, causing extensive outbreaks. By the end of September, nearly the entire inhabited world had been infected or at least seeded with the virus. The [[Northern Hemisphere]] experienced widespread outbreaks during the fall and winter, and some parts of the world saw a second wave during this time or in early 1958.<ref name=":1" /> The pandemic caused about two million deaths globally.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/8017585.stm | title = Q&A: Swine flu | work = BBC News | date = 27 April 2009 }}</ref> |

|||

* The "[[Hong Kong flu]]", 1968–70. An [[Influenza A virus subtype H3N2|H3N2]] virus was first detected in Hong Kong in July 1968 and spread across the world, lasting until 1970. This pandemic exhibited a more "smoldering" pattern as compared with other influenza pandemics, with uneven impact in different places over time.<ref name="Viboud">{{cite journal | vauthors = Viboud C, Grais RF, Lafont BA, Miller MA, Simonsen L | title = Multinational impact of the 1968 Hong Kong influenza pandemic: evidence for a smoldering pandemic | journal = The Journal of Infectious Diseases | volume = 192 | issue = 2 | pages = 233–248 | date = July 2005 | pmid = 15962218 | doi = 10.1086/431150 }}</ref> Its course at first resembled that of the 1957 pandemic, but after a couple of months its spread faltered; the virus did not immediately result in extensive outbreaks in some places, despite repeated introductions.<ref name=":12">{{cite journal | vauthors = Cockburn WC, Delon PJ, Ferreira W | title = Origin and progress of the 1968-69 Hong Kong influenza epidemic | journal = Bulletin of the World Health Organization | volume = 41 | issue = 3 | pages = 345–348 | year = 1969 | pmid = 5309437 | pmc = 2427756 }}</ref> The United States notably experienced an intense epidemic during the 1968–1969 flu season, the first with the pandemic virus, while European and Asian countries were relatively less affected.<ref name=":12" /><ref name="Viboud" /> During the 1969–1970 season, however, the United States was much less affected, while Europe and Asia experienced extensive outbreaks of the pandemic virus. In the Southern Hemisphere, Australia experienced a pattern more akin to Europe and Asia, with a more severe second wave.<ref name="Viboud" /> This pandemic killed approximately one million people worldwide.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Dumar AM |title=Swine Flu: What You Need to Know|date=2009|publisher=Wildside Press LLC|isbn=978-1434458322|page=20}}</ref> |

|||

* The "[[1977 Russian flu]]", 1977–79. An H1N1 virus was first reported by the Soviet Union in 1977. The pandemic caused an estimated 700,000 deaths worldwide<ref name=":6">{{cite journal | vauthors = Michaelis M, Doerr HW, Cinatl J | title = Novel swine-origin influenza A virus in humans: another pandemic knocking at the door | journal = Medical Microbiology and Immunology | volume = 198 | issue = 3 | pages = 175–183 | date = August 2009 | pmid = 19543913 | doi = 10.1007/s00430-009-0118-5 | s2cid = 20496301 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="1977flu">{{cite journal | vauthors = Petrovski BÉ, Lumi X, Znaor L, Ivastinović D, Confalonieri F, Petrovič MG, Petrovski G | title = Reorganize and survive-a recommendation for healthcare services affected by COVID-19-the ophthalmology experience | journal = Eye | volume = 34 | issue = 7 | pages = 1177–1179 | date = July 2020 | pmid = 32313170 | pmc = 7169374 | doi = 10.1038/s41433-020-0871-7 }}</ref> and mostly affected the younger population.<ref name="1977flu2">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rozo M, Gronvall GK | title = The Reemergent 1977 H1N1 Strain and the Gain-of-Function Debate | journal = mBio | volume = 6 | issue = 4 | date = August 2015 | pmid = 26286690 | pmc = 4542197 | doi = 10.1128/mBio.01013-15 }}</ref> |

|||

* The "[[2009 swine flu pandemic|Swine flu]]", 2009–10. An H1N1 virus first detected in Mexico in early 2009. Estimates for the mortality of this pandemic range from 150 to 500 thousand.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Trifonov V, Khiabanian H, Rabadan R | title = Geographic dependence, surveillance, and origins of the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 361 | issue = 2 | pages = 115–119 | date = July 2009 | pmid = 19474418 | doi = 10.1056/NEJMp0904572 | df = dmy-all | s2cid = 205105276 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/2009-h1n1-pandemic.html|title=2009 H1N1 Pandemic|date=11 June 2019|website=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention}}</ref> |

|||

==== Typhus ==== |

|||

[[Typhus]] is sometimes called "camp fever" because of its pattern of flaring up in times of strife. (It is also known as "gaol fever", "Aryotitus fever" and "ship fever", for its habits of spreading wildly in cramped quarters, such as jails and ships.) Emerging during the [[Crusades]], it had its first impact in Europe in 1489, in Spain. During fighting between the Christian Spaniards and the Muslims in [[Granada]], the Spanish lost 3,000 to war casualties, and 20,000 to typhus. In 1528, the French lost 18,000 troops in Italy, and lost supremacy in Italy to the Spanish. In 1542, 30,000 soldiers died of typhus while fighting the [[Ottoman Empire|Ottomans]] in the Balkans. |

|||

During the [[Thirty Years' War]] (1618–1648), about eight million Germans were killed by bubonic plague and typhus.<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20090921004137/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,794989,00.html War and Pestilence]. ''Time.'' 29 April 1940</ref> The disease also played a major role in the destruction of [[Napoleon]]'s ''[[La Grande Armée|Grande Armée]]'' in Russia in 1812. During the retreat from Moscow, more French military personnel died of [[typhus]] than were killed by the Russians.<ref>[http://entomology.montana.edu/historybug/TYPHUS-Conlon.pdf The Historical Impact of Epidemic Typhus] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100611213940/http://entomology.montana.edu/historybug/TYPHUS-Conlon.pdf |date=11 June 2010}}. Joseph M. Conlon.</ref> Of the 450,000 soldiers who crossed the [[Neman River|Neman]] on 25 June 1812, fewer than 40,000 returned. More military personnel were killed from 1500 to 1914 by typhus than from military action.<ref name="TIME Magazine 1940">[https://web.archive.org/web/20090921004137/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,794989,00.html War and Pestilence]. ''Time''.</ref> In early 1813, Napoleon raised a new army of 500,000 to replace his Russian losses. In the campaign of that year, more than 219,000 of Napoleon's soldiers died of typhus.<ref name=Typhus/> Typhus played a major factor in the [[Great Famine (Ireland)|Great Famine of Ireland]]. During [[World War I]], typhus epidemics killed more than 150,000 in [[Serbia]]. There were about 25 million infections and 3{{nbsp}}million deaths from [[epidemic typhus]] in Russia from 1918 to 1922.<ref name=Typhus>{{cite web |url=http://entomology.montana.edu/historybug/TYPHUS-Conlon.pdf |title=The historical impact of epidemic typhus | vauthors = Conlon JM |access-date=21 April 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100611213940/http://entomology.montana.edu/historybug/TYPHUS-Conlon.pdf |archive-date=11 June 2010 }}</ref> Typhus also killed numerous prisoners in the [[Nazi concentration camps]] and Soviet prisoner of war camps during World War{{nbsp}}II. More than 3.5 million [[Nazi crimes against Soviet POWs|Soviet POWs]] died out of the 5.7 million in Nazi custody.<ref>[http://www.historynet.com/soviet-prisoners-of-war-forgotten-nazi-victims-of-world-war-ii.htm Soviet Prisoners of War: Forgotten Nazi Victims of World War II] By Jonathan Nor, TheHistoryNet</ref> |

|||

==== Smallpox ==== |

|||

[[File:Child with Smallpox Wellcome L0032953.jpg|thumb|Child with smallpox, {{circa|1908}}]] |

|||

[[Smallpox]] was a contagious disease caused by the [[variola virus]]. The disease killed an estimated 400,000 Europeans per year during the closing years of the 18th century.<ref>[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=vacc.chapter.3 Smallpox and Vaccinia] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090601172056/http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=vacc.chapter.3 |date=1 June 2009}}. ''National Center for Biotechnology Information.''</ref> During the 20th century, it is estimated that smallpox was responsible for 300–500 million deaths.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ucdavismagazine.ucdavis.edu/issues/su06/feature_1b.html |title=UC Davis Magazine, Summer 2006: Epidemics on the Horizon |access-date=3 January 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081211181455/http://ucdavismagazine.ucdavis.edu/issues/su06/feature_1b.html |archive-date=11 December 2008 }}</ref><ref>[https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/01/080131122956.htm How Poxviruses Such As Smallpox Evade The Immune System], ScienceDaily, 1{{nbsp}}February 2008</ref> As recently as the early 1950s, an estimated 50 million cases of smallpox occurred in the world each year.<ref>[https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/smallpox/en/ "Smallpox"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070921235036/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/smallpox/en/ |date=21 September 2007 }}. ''WHO Factsheet.'' Retrieved on 22 September 2007.</ref> After successful [[vaccination]] campaigns throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the WHO certified the eradication of smallpox in December 1979. To this day, smallpox is the only human infectious disease to have been completely eradicated,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = De Cock KM | title = (Book Review) The Eradication of Smallpox: Edward Jenner and The First and Only Eradication of a Human Infectious Disease| journal = Nature Medicine | year = 2001 | volume = 7 | pages = 15–16 | doi = 10.1038/83283 |doi-access=free| issue=1 }}</ref> and one of two infectious viruses ever to be eradicated, along with [[rinderpest]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.oie.int/en/for-the-media/rinderpest/|title=Rinderpest: OIE—World Organisation for Animal Health|website=oie.int}}</ref> |

|||

==== Measles ==== |

|||

Historically, [[measles]] was prevalent throughout the world, as it is highly contagious. According to the U.S. [[National Immunization Program]], by 1962 90% of people were infected with measles by age 15.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Orenstein WA, Papania MJ, Wharton ME | title = Measles elimination in the United States | journal = The Journal of Infectious Diseases | volume = 189 | issue = Supplement_1 | pages = S1–S3 | date = May 2004 | pmid = 15106120 | doi = 10.1086/377693 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Before the vaccine was introduced in 1963, there were an estimated three to four million cases in the U.S. each year.<ref name=autogenerated1>Center for Disease Control & National Immunization Program. Measles History, article online 2001. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/history.html</ref> Measles killed around 200 million people worldwide over the last 150 years.<ref name=Measles/> In 2000 alone, measles killed some 777,000 worldwide out of 40 million cases globally.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Stein CE, Birmingham M, Kurian M, Duclos P, Strebel P | title = The global burden of measles in the year 2000--a model that uses country-specific indicators | journal = The Journal of Infectious Diseases | volume = 187| issue = Suppl 1 | pages = S8-14 | date = May 2003 | pmid = 12721886 | doi = 10.1086/368114 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

Measles is an [[endemic disease]], meaning it has been continually present in a community, and many people develop resistance. In populations that have not been exposed to measles, exposure to a new disease can be devastating. In 1529, a measles outbreak in [[Cuba]] killed two-thirds of the natives who had previously survived smallpox.<ref>''Man and Microbes: Disease and Plagues in History and Modern Times''; by [[Arno Karlen]]</ref> The disease had ravaged Mexico, [[Central America]], and the [[Inca]] civilization.<ref>[http://www.millersville.edu/~columbus/data/art/RUVALCA1.ART "Measles and Small Pox as an Allied Army of the Conquistadors of America"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090502200745/http://www.millersville.edu/~columbus/data/art/RUVALCA1.ART |date=2 May 2009 }} by Carlos Ruvalcaba, translated by Theresa M. Betz in "Encounters" (Double Issue No. 5–6, pp. 44–45)</ref> |

|||

==== Tuberculosis ==== |

|||

{{see also|History of tuberculosis#Epidemic tuberculosis}} |

|||

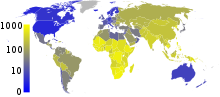

[[File:Tuberculosis-prevalence-WHO-2009.svg|thumb|In 2007, the prevalence of TB per 100,000 people was highest in [[Sub-Saharan Africa]], and was also relatively high in Asian countries, e.g. India.]] |

|||

One-quarter of the [[World population|world's current population]] has been infected with ''[[Mycobacterium tuberculosis]]'', and new infections occur at a rate of one per second.<ref name="WHO2004data">[[World Health Organization]] (WHO). [https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/index.html Tuberculosis Fact sheet No. 104—Global and regional incidence.] March 2006, Retrieved on 6 October 2006.</ref> About 5–10% of these latent infections will eventually progress to active disease, which, if left untreated, kills more than half its victims. Annually, eight million people become ill with tuberculosis, and two million die from the disease worldwide.<ref name=CDC>[[Centers for Disease Control]]. [https://www.cdc.gov/od/oc/Media/pressrel/fs050317.htm Fact Sheet: Tuberculosis in the United States.] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090423234343/http://www.cdc.gov/od/oc/media/pressrel/fs050317.htm |date=23 April 2009 }} 17 March 2005, Retrieved on 6 October 2006.</ref> In the 19th century, tuberculosis killed an estimated one-quarter of the adult population of Europe;<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.cdc.gov/TB/pubs/mdrtb/default.htm |title=Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis |access-date=7 September 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100309043219/http://www.cdc.gov/TB/pubs/mdrtb/default.htm |archive-date=9 March 2010 |url-status=dead }}</ref> by 1918, one in six deaths in France were still caused by tuberculosis. During the 20th century, tuberculosis killed approximately 100 million people.<ref name=Measles>{{cite web |url=http://birdflubook.com/a.php?id=40&t=p |author1=Torrey, EF |author2=Yolken, RH |title=Their bugs are worse than their bite |date=3 April 2005 |page=B01 |publisher=Birdflubook.com |access-date=26 August 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130626090223/http://birdflubook.com/a.php?id=40&t=p |archive-date=26 June 2013 |url-status=dead }}</ref> TB is still one of the most important health problems in the developing world.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Rook GA, Dheda K, Zumla A | title = Immune responses to tuberculosis in developing countries: implications for new vaccines | journal = Nature Reviews. Immunology | volume = 5 | issue = 8 | pages = 661–667 | date = August 2005 | pmid = 16056257 | doi = 10.1038/nri1666 | s2cid = 9004625 }}</ref> In 2021, Tuberculosis became the second leading cause of death from an infectious disease, with roughly 1.6 million deaths worldwide, below [[COVID-19]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Tuberculosis |url=https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis |website=WHO |date=24 March 2020 |access-date=31 May 2020 }}</ref> |

|||

==== Leprosy ==== |

|||

[[Leprosy]], also known as Hansen's disease, is caused by a [[Bacillus (shape)|bacillus]], ''[[Mycobacterium leprae]]''. It is a [[chronic disease]] with an incubation period of up to five years. Since 1985, 15 million people worldwide have been cured of leprosy.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/6522023.stm Leprosy 'could pose new threat']. BBC News. 3 April 2007.</ref> |

|||

Historically, leprosy has affected people since at least 600 BC.<ref name=WHO_Factsheet>{{cite web | title = Leprosy | work = WHO | url =https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs101/en/ | access-date = 22 August 2007}}</ref> Leprosy outbreaks began to occur in Western Europe around 1000 AD.<ref>{{Cite journal | jstor=41887256| title=Medieval Leprosy Reconsidered| journal=International Social Science Review| volume=81| issue=1/2| pages=16–28| vauthors = Miller TS, Smith-Savage R | year=2006}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Boldsen JL | title = Leprosy and mortality in the Medieval Danish village of Tirup | journal = American Journal of Physical Anthropology | volume = 126 | issue = 2 | pages = 159–168 | date = February 2005 | pmid = 15386293 | doi = 10.1002/ajpa.20085 }}</ref> Numerous ''leprosoria'', or [[Leper colony|leper hospitals]], sprang up in the [[Middle Ages]]; [[Matthew Paris]] estimated that in the early 13th century, there were 19,000 of them across Europe.<ref>{{CathEncy|wstitle=Leprosy}}</ref> |

|||

==== Malaria ==== |

|||

[[File:World-map-of-past-and-current-malaria-prevalence-world-development-report-2009.png|thumb|Past and current malaria prevalence in 2009]] |

|||

[[Malaria]] is widespread in [[Tropics|tropical]] and subtropical regions, including parts of the Americas, Asia, and Africa. Each year, there are approximately 350–500 million cases of malaria.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/facts.htm |title=Malaria Facts |access-date=7 September 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121229091605/http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/facts.htm |archive-date=29 December 2012 |url-status=dead }}</ref> [[Drug resistance]] poses a growing problem in the treatment of malaria in the 21st century, since resistance is now common against all classes of antimalarial drugs, except for the [[artemisinin]]s.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = White NJ | title = Antimalarial drug resistance | journal = The Journal of Clinical Investigation | volume = 113 | issue = 8 | pages = 1084–1092 | date = April 2004 | pmid = 15085184 | pmc = 385418 | doi = 10.1172/JCI21682 }}</ref> |

|||

Malaria was once common in most of Europe and North America, where it is now for all purposes non-existent.<ref>[http://www.cambridge.org/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780511254819&ss=exc Vector- and Rodent-Borne Diseases in Europe and North America]. Norman G. Gratz. ''World Health Organization, Geneva.''</ref> Malaria may have contributed to the decline of the [[Roman Empire]].<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/1180469.stm DNA clues to malaria in ancient Rome]. ''BBC News.'' 20 February 2001.</ref> The disease became known as "[[Roman Fever (disease)|Roman fever]]".<ref>[http://www.abc.net.au/rn/talks/perspective/stories/s776423.htm "Malaria and Rome"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110511184622/http://www.abc.net.au/rn/talks/perspective/stories/s776423.htm |date=11 May 2011}}. Robert Sallares. ''ABC.net.au.'' 29 January 2003.</ref> ''[[Plasmodium falciparum]]'' became a real threat to colonists and [[indigenous people]] alike when it was introduced into the Americas along with the [[slave trade]]. Malaria devastated the [[Jamestown, Virginia|Jamestown]] colony and regularly ravaged the South and Midwest of the United States. By 1830, it had reached the Pacific Northwest.<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20090619083534/http://www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/Website/Course%20Index/Lessons/7/7.html "The Changing World of Pacific Northwest Indians"]. ''Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington.''</ref> During the [[American Civil War]], there were more than 1.2 million cases of malaria among |

|||

soldiers of both sides.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.infoplease.com/cig/dangerous-diseases-epidemics/malaria.html |title=A Brief History of Malaria |publisher=Infoplease.com |access-date=26 August 2010}}</ref> The [[Southern United States|southern U.S.]] continued to be affected by millions of cases of malaria into the 1930s.<ref>[http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0707/feature1/text3.html Malaria]. By [[Michael Finkel]]. ''National Geographic Magazine.''</ref> |

|||

==== Yellow fever ==== |

|||

[[Yellow fever]] has been a source of several devastating epidemics.<ref>{{cite EB1911 |wstitle=Yellow_Fever |volume=28 |pages=910–911}}.</ref> Cities as far north as New York, Philadelphia, and Boston were hit with epidemics. In 1793, one of the largest [[Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793|yellow fever epidemics]] in U.S. history killed as many as 5,000 people in Philadelphia—roughly 10% of the population. About half of the residents had fled the city, including President George Washington.<ref>{{cite web | vauthors = Arnebeck B | title=A Short History of Yellow Fever in the US | work=Benjamin Rush, Yellow Fever and the Birth of Modern Medicine | date=30 January 2008 | url=http://www.geocities.com/bobarnebeck/history.html | access-date=4 December 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071107163908/http://www.geocities.com/bobarnebeck/history.html|archive-date=7 November 2007}}</ref> |

|||

Another major outbreak of the disease struck the Mississippi River Valley in 1878, with deaths estimated at 20,000. Among the hardest-hit places was Memphis, Tennessee, where 5,000 people were killed and over 20,000 fled, then representing over half the city's population, many of whom never returned. In colonial times, West Africa became known as "the white man's grave" because of malaria and yellow fever.<ref>[https://www.nytimes.com/1995/10/15/weekinreview/the-world-africa-s-nations-start-to-be-theirbrothers-keepers.html Africa's Nations Start to Be Their Brothers' Keepers]. ''The New York Times'', 15 October 1995.</ref> |

|||

== Concerns about future pandemics == |

|||

{{See also|Pandemic prevention}} |

|||

In a press conference on 28 December 2020, Mike Ryan, head of the WHO Emergencies Program, and other officials said the current COVID-19 pandemic is "not necessarily the big one" and "the next pandemic may be more severe." They called for preparation.<ref>{{Cite web|date=29 December 2020|title=WHO official: 'Next pandemic may be more severe'|url=https://arab.news/yx8p9|access-date=30 December 2020|website=Arab News|language=en}}</ref> The WHO and the UN, have warned the world must tackle the cause of pandemics and not just the health and economic symptoms.<ref>{{Cite web| vauthors = Carrington D |date=2021-03-09|title=Inaction leaves world playing 'Russian roulette' with pandemics, say experts|url=http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/mar/09/inaction-leaves-world-playing-russian-roulette-pandemics-experts|access-date=2021-03-10|website=The Guardian|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

The October 2020 'era of pandemics' report by the [[United Nations]]' [[Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services]], written by 22 experts in a variety of fields, said the anthropogenic destruction of [[biodiversity]] is paving the way to the pandemic era and could result in as many as 850,000 viruses being transmitted from animals—in particular [[birds]] and [[mammals]]—to humans. The [[Overconsumption|"exponential rise" in consumption]] and trade of commodities such as [[meat]], [[palm oil]], and metals, largely facilitated by developed nations, and a [[Population growth|growing human population]], are the primary drivers of this destruction. According to [[Peter Daszak]], the chair of the group who produced the report, "there is no great mystery about the cause of the Covid-19 pandemic or any modern pandemic. The same human activities that drive [[climate change and biodiversity loss]] also drive pandemic risk through their impacts on our environment." Proposed policy options from the report include taxing meat production and consumption, cracking down on the illegal wildlife trade, removing high-risk species from the legal wildlife trade, eliminating subsidies to businesses that are harmful to the natural world, and establishing a global surveillance network.<ref>{{cite news | vauthors = Woolaston K, Fisher JL |date=29 October 2020 |title=UN report says up to 850,000 animal viruses could be caught by humans, unless we protect nature |url=https://theconversation.com/un-report-says-up-to-850-000-animal-viruses-could-be-caught-by-humans-unless-we-protect-nature-148911 |work= [[The Conversation (website)|The Conversation]]|access-date=1 December 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite news | vauthors = Carrington D |date=29 October 2020 |title=Protecting nature is vital to escape 'era of pandemics' – report |url=https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/oct/29/protecting-nature-vital-pandemics-report-outbreaks-wild |work=The Guardian |access-date=1 December 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |date=29 October 2020 |title=Escaping the 'Era of Pandemics': experts warn worse crises to come; offer options to reduce risk |url=https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2020-10/tca-et102820.php |work=EurekAlert! |access-date=1 December 2020}}</ref> |

|||

In June 2021, a team of scientists assembled by the [[Harvard Medical School Center for Health and the Global Environment]] warned that the primary cause of pandemics so far, the anthropogenic destruction of the natural world through such activities including [[deforestation]] and [[hunting]], is being ignored by world leaders.<ref>{{cite news | vauthors = Carrington D |date=June 4, 2021 |title=World leaders 'ignoring' role of the destruction of nature in causing pandemics |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/04/end-destruction-of-nature-to-stop-future-pandemics-say-scientists |work=The Guardian |location= |access-date=June 4, 2021}}</ref> |

|||

=== Pandemic prevention === |

|||

{{See also|Pandemic prevention}} |

|||

Prevention of future pandemics requires steps to identify future causes of pandemics and to take preventive measures before the disease moves uncontrollably into the human population. |

|||

For example, influenza is a rapidly evolving disease which has caused pandemics in the past and has potential to cause future pandemics. The World Health Organisation collates the findings of 144 national influenza centres worldwide which monitor emerging flu viruses. Virus variants which are assessed as likely to represent a significant risk are identified and can then be incorporated into the next seasonal influenza vaccine program.<ref>{{Cite web |date=3 November 2022 |title=Selecting Viruses for the Seasonal Flu Vaccine |url=https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/vaccine-selection.htm |access-date=30 June 2023 |website=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |language=en-us}}</ref> |

|||

In order to encourage research, a number of organisations which monitor global health have drawn up lists of diseases which may have pandemic potential; see table below.{{Efn|As of June 2023, the WHO is reviewing its list}} |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

|+List of potential pandemic diseases according to global health organisations |

|+List of potential pandemic diseases according to global health organisations |

||

| Line 357: | Line 275: | ||

|} |

|} |

||

=== |

==== Coronaviruses ==== |

||

{{Main| |

{{Main|Coronavirus|Coronavirus diseases}} |

||

{{Further|2002–2004 SARS outbreak|COVID-19 pandemic}} |

|||

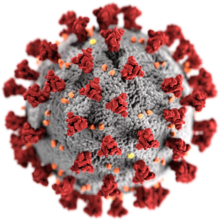

[[File:SARS-CoV-2 without background.png|thumb|right|Illustration created at the [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC), reveals ultrastructural morphology exhibited by coronaviruses; note the [[coronavirus spike protein|spikes]] that adorn the outer surface, which impart the look of a corona surrounding the [[virion]].<ref>{{cite journal |name-list-style=vanc |vauthors=Sonnevend J |date=December 2020 |title=A virus as an icon: the 2020 pandemic in images |journal=American Journal of Cultural Sociology |publisher=[[Palgrave Macmillan]] |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=451–461 |doi=10.1057/s41290-020-00118-7 |eissn=2049-7121 |pmc=7537773 |pmid=33042541 |doi-access=free |veditors=Alexander JC, Jacobs RN, Smith P}}</ref>]] |

|||

[[Coronavirus]]es (CoV) are a large family of viruses that cause illness ranging from the [[common cold]] to more severe diseases such as [[Middle East respiratory syndrome]] (MERS-CoV) and [[severe acute respiratory syndrome]] (SARS-CoV-1).<ref name="ACAIM-WACEM COVID-19 Consensus Paper" /> A new strain of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) causes [[Coronavirus disease 2019]], or COVID-19,<ref>{{cite news |title=When a danger is growing exponentially, everything looks fine until it doesn't |language=en |newspaper=Washington Post |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/03/10/coronavirus-what-matters-isnt-what-you-can-see-what-you-cant/ |access-date=15 March 2020 |vauthors=McArdle M}}</ref> which was declared as a [[COVID-19 pandemic|pandemic]] by the WHO on 11 March 2020.<ref name="ACAIM-WACEM COVID-19 Consensus Paper" /> |

|||

Antibiotic-resistant microorganisms, which sometimes are referred to as "[[Antibiotic resistance|superbug]]s", may contribute to the re-emergence of diseases with pandemic potential that are currently well controlled.<ref>[http://www.pasteur.fr/actu/presse/press/07pesteTIGR_E.htm Researchers sound the alarm: the multidrug resistance of the plague bacillus could spread] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071014012153/http://www.pasteur.fr/actu/presse/press/07pesteTIGR_E.htm|date=14 October 2007}}. Pasteur.fr</ref> |

|||

Some coronaviruses are [[zoonotic]], meaning they are transmitted between animals and people. Detailed investigations found that SARS-CoV-1 was transmitted from [[Masked palm civet|civet cats]] to humans and MERS-CoV from dromedary camels to humans. Several known coronaviruses are circulating in animals that have not yet infected humans. Common signs of infection include respiratory symptoms, [[fever]], [[cough]], shortness of breath, and breathing difficulties. In more severe cases, an infection can cause pneumonia, [[acute respiratory distress syndrome]], kidney failure, and even death. Standard recommendations to prevent the spread of infection include regular hand washing, wearing a face mask, going outdoors when meeting people, and avoiding close contact with people who have tested positive regardless of whether they have symptoms or not. It is recommended that people stay two meters or six feet away from others, commonly called social distancing. |

|||

For example, cases of tuberculosis that are resistant to traditionally effective treatments remain a cause of great concern to health professionals. Every year, nearly half a million new cases of [[multidrug-resistant tuberculosis]] (MDR-TB) are estimated to occur worldwide.<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20090406170131/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2009/tuberculosis_drug_resistant_20090402/en/index.html Health ministers to accelerate efforts against drug-resistant TB]. ''World Health Organization.''</ref> China and India have the highest rate of MDR-TB.<ref>[https://www.theguardian.com/society/2009/apr/01/bill-gates-tb-timebomb-china Bill Gates joins Chinese government in tackling TB 'timebomb']. ''Guardian.co.uk''. 1 April 2009</ref> The [[World Health Organization]] (WHO) reports that approximately 50 million people worldwide are infected with MDR-TB, with 79 percent of those cases resistant to three or more antibiotics. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis ([[XDR TB|XDR-TB]]) was first identified in Africa in 2006 and subsequently discovered to exist in 49 countries. During 2021 there were estimated to be around 25,000 cases XDR-TB worldwide.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Global Tuberculosis Report |url=https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports |access-date=2023-06-30 |website=World Health Organisation |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

==== Dengue fever ==== |

|||

In the past 20 years, other common bacteria including ''[[Staphylococcus aureus]]'', ''[[Serratia marcescens]]'' and ''[[Enterococcus]]'', have developed resistance to a wide range of [[antibiotics]]. Antibiotic-resistant organisms have become an important cause of healthcare-associated ([[Hospital-acquired infection|nosocomial]]) infections.<ref name=":8">{{cite journal |vauthors=Murray CJ, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, Swetschinski L, Aguilar GR, Gray A, etal |date=February 2022 |title=Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis |journal=Lancet |language=English |volume=399 |issue=10325 |pages=629–655 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0 |pmc=8841637 |pmid=35065702 |s2cid=246077406 |collaboration=Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators}}</ref> |

|||

Dengue is spread by several species of female mosquitoes of the Aedes type, principally ''A. aegypti''. The virus has five types; infection with one type usually gives lifelong immunity to that type, but only short-term immunity to the others. Subsequent infection with a different type increases the risk of severe complications. Several tests are available to confirm the diagnosis including detecting antibodies to the virus or its RNA. |

|||

=== |

==== Influenza ==== |

||

{{Main|Influenza pandemic}} |

|||

{{See|Effects of global warming on human health#Impact on infectious diseases}} |

|||

[[File:Pandemie.jpg|thumb|upright]]The Greek physician [[Hippocrates]], the "Father of Medicine", first described influenza in 412{{nbsp}}BC.<ref>{{cite web |title=50 Years of Influenza Surveillance |url=http://who.int/inf-pr-1999/en/pr99-11.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090501165850/http://www.who.int/inf-pr-1999/en/pr99-11.html |archive-date=1 May 2009 |work=World Health Organization}}</ref> |

|||

* The first influenza pandemic to be pathologically described [[1510 influenza pandemic|occurred in 1510]]. Since the pandemic of 1580, influenza pandemics have occurred every 10 to 30 years.<ref>{{cite web |title=Pandemic Flu |url=http://www.gov.im/dhss/about/Public_Health/hp/pandemicflu/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120107000431/http://www.gov.im/dhss/about/Public_Health/hp/pandemicflu/ |archive-date=7 January 2012 |work=Department of Health and Social Security.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Influenza: The Last Great Plague: An Unfinished Story of Discovery |vauthors=Beveridge WI |date=1977 |isbn=0-88202-118-4 |location=New York: Prodist |quote=Return of the Germs: For more than a century drugs and vaccines made astounding progress against infectious diseases. Now our best defenses may be social changes}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Potter CW |date=October 2001 |title=A history of influenza |journal=Journal of Applied Microbiology |volume=91 |issue=4 |pages=572–579 |doi=10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x |pmid=11576290 |s2cid=26392163 |doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

* The [[1889–1890 pandemic]] was attributed to influenza at the time but more recent research suggests it may have been caused by [[human coronavirus OC43]]. Also known as Russian Flu or Asiatic Flu, it was first reported in May 1889 in [[Bukhara]], [[Uzbekistan]]. By October, it had reached [[Tomsk]] and the [[Caucasus]]. It rapidly spread west and hit North America in December 1889, South America in February–April 1890, India in February–March 1890, and Australia in March–April 1890. The [[H3N8]] and [[H2N2]] subtypes of the [[influenza A virus]] have each been identified as possible causes. It had a very high attack and [[mortality rate]], causing around a million fatalities.<ref>{{cite web |date=16 June 2011 |title=Pandemic Influenza |url=http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/cidrap/content/influenza/panflu/biofacts/index.html |work=CIDRAP}}</ref> |

|||

* The "[[Spanish flu]]", 1918–1920. First identified early in March 1918 in U.S. troops training at [[Fort Riley|Camp Funston]], [[Kansas]]. By October 1918, it had spread to become a worldwide pandemic on all continents, and eventually infected about one-third of the [[world's population]] (or ≈500 million persons).<ref name="Taubenberger" /> Unusually deadly and virulent, it persisted in pandemic form for at least two years before settling into more endemic patterns.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Chandra S, Christensen J, Likhtman S |date=November 2020 |title=Connectivity and seasonality: the 1918 influenza and COVID-19 pandemics in global perspective |journal=Journal of Global History |volume=15 |issue=3 |pages=413–414 |doi=10.1017/S1740022820000261 |s2cid=228988279 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Within six months, some 50{{nbsp}}million people were dead;<ref name="Taubenberger" /> some estimates put the total number of fatalities worldwide at over twice that number.<ref>{{cite web |title=Spanish flu |url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/articles/s/spanish_flu.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150325113108/http://www.sciencedaily.com/articles/s/spanish_flu.htm |archive-date=25 March 2015 |work=ScienceDaily}}</ref> About 17{{nbsp}}million died in India, 675,000 in the United States,<ref>{{cite web |title=The Great Pandemic: The United States in 1918–1919 |url=http://1918.pandemicflu.gov/the_pandemic/index.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111126082941/http://1918.pandemicflu.gov/the_pandemic/index.htm |archive-date=26 November 2011 |work=U.S. Department of Health & Human Services}}</ref> and 200,000 in the United Kingdom. The virus that caused Spanish flu was also implicated as a cause of [[encephalitis lethargica]] in children.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Vilensky JA, Foley P, Gilman S |date=August 2007 |title=Children and encephalitis lethargica: a historical review |journal=Pediatric Neurology |volume=37 |issue=2 |pages=79–84 |doi=10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.04.012 |pmid=17675021}}</ref> The virus was recently reconstructed by scientists at the [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|CDC]] studying remains preserved by the Alaskan [[permafrost]]. The [[Pandemic H1N1/09 virus|2009 pandemic H1N1 virus]] has a small but crucial structure that is similar to the Spanish flu.<ref>{{Cite web |title=H1N1 shares key similar structures to 1918 flu, providing research avenues for better vaccines |url=https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/h1n1-shares-key-similar-structures-to-1918-flu-providing-research-avenues-for-better-vaccines/ |website=Scientific American Blog Network |vauthors=Harmon K}}</ref> |

|||

* The "[[1957–1958 influenza pandemic|Asian flu]]", 1957–58. An [[Influenza A virus subtype H2N2|H2N2]] virus was first identified in China in late February 1957 but not recognized globally until after an outbreak in [[Hong Kong]] in April.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |date=1958-12-01 |title=Symposium on the Asian Influenza Epidemic, 1957 |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine |language=en |volume=51 |issue=12 |pages=1009–1018 |doi=10.1177/003591575805101205 |issn=0035-9157 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name=":16">{{cite journal |vauthors=Murray R |date=1969 |title=Production and testing in the USA of influenza virus vaccine made from the Hong Kong variant in 1968-69 |journal=Bulletin of the World Health Organization |volume=41 |issue=3 |pages=495–496 |pmc=2427701 |pmid=5309463 |hdl=10665/262478}}</ref> From there, it spread throughout [[Southeast Asia]] and the greater continent during the spring and throughout the [[Southern Hemisphere]] during the middle months of the year, causing extensive outbreaks. By the end of September, nearly the entire inhabited world had been infected or at least seeded with the virus. The [[Northern Hemisphere]] experienced widespread outbreaks during the fall and winter, and some parts of the world saw a second wave during this time or in early 1958.<ref name=":1" /> The pandemic caused about two million deaths globally.<ref>{{cite web |date=27 April 2009 |title=Q&A: Swine flu |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/8017585.stm |work=BBC News}}</ref> |

|||