History of South India

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

The history of southern India covers a span of over four thousand years during which the region saw the rise and fall of a number of dynasties and empires. The period of known history of the region begins with the Iron Age (1200 BCE to 24 BCE) period until the 15th century CE. Dynasties of Chera, Chola, Pandyan, Chalukya, Pallava, Satavahana Rashtrakuta, Kakatiya, Reddy dynasty, Seuna (Yadava) dynasty and Hoysala were at their peak during various periods of history. These Dynasties constantly fought amongst each other and against external forces when northern armies invaded southern India. Vijayanagara empire rose in response to the Muslim intervention and covered the most of southern India and acted as a bulwark against Mughal expansion into the south. When the European powers arrived during the 16th and 18th century CE, the southern kingdoms, most notably Tipu Sultan's Kingdom of Mysore, resisted the new threats, and many parts eventually succumbed to British occupation. The British created the Madras Presidency which acted as an administrative centre for the rest of South India, with them being princely states. After Indian independence South India was linguistically divided into the states of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana and Kerala.

Prehistory

South India remained in the Mesolithic until 2500 BCE. Microlith production is attested for the period 6000 to 3000 BCE. The Neolithic period lasted from 2500 BCE to 1000 BCE, followed by the Iron Age, characterized by megalithic burials.[1] Comparative excavations carried out in Adichanallur in Thirunelveli district and in Northern India have provided evidence of a southward migration of the Megalithic culture.[2] The Krishna Tungabhadra Valley[3] was also a place for Megalithic culture in South India.

Iron Age

The earliest Iron Age sites in South India are Hallur, Karnataka and Adichanallur, Tamil Nadu[4] at around 1200 BCE.

Early epigraphic evidence begins to appear from about the 5th century BCE, in the form of Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions, reflecting the southward spread of Buddhism.

Ancient history

Evidence in the forms of documents and inscriptions do not appear often in the history of ancient South India. Although there are signs that the history dates back to several centuries BCE, we only have an authentic archaeological evidence from the early centuries of the common era.

During the reign of Ashoka (304–232 BCE) the three Tamil dynasties of Chola, Chera and Pandya were ruling the south.

Pandyan Dynasty

The Pandyas were one of the three ancient Tamil dynasties (Chola and Chera being the other two) who ruled the Tamil country from pre-historic times until the end of the 15th century. They ruled initially from Korkai, a seaport on the southernmost tip of the Indian peninsula, and in later times moved to Madurai. Pandyas are mentioned in Sangam Literature (c. 400 BCE – 300 CE) as well as by Greek and Roman sources during this period.

The early Pandya dynasty of the Sangam literature went into obscurity during the invasion of the Kalabhras. The dynasty revived under Kadungon in the early 6th century CE, pushed the Kalabhras out of the Tamil country and ruled from Madurai. They again went into decline with the rise of the Cholas in the 9th century CE and were in constant conflict with them. Pandyas allied themselves with the Sinhalese and the Cheras in harassing the Chola empire until they found an opportunity for reviving their fortunes during the late 13th century. Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan (c. 1251) expanded their empire into the Telugu country and invaded Sri Lanka to conquer the northern half of the island. They also had extensive trade links with the Southeast Asian maritime empires of Srivijaya and their successors. During their history Pandyas were repeatedly in conflict with the Pallavas, Cholas, Hoysalas and finally the Muslim invaders from the Delhi Sultanate. The Pandyan Kingdom finally became extinct after the establishment of the Madurai Sultanate in the 14th century CE. The Pandyas excelled in both trade and literature. They controlled the pearl fisheries along the south Indian coast, between Sri Lanka and India, which produced one of the finest pearls known in the ancient world.

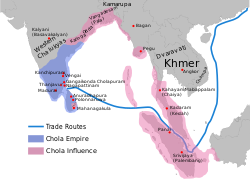

Chola Dynasty – Empire

The Cholas were one of the three main dynasties to rule south India from ancient times. Karikala Chola (late 1st century CE) was the most famous king during the early years of the dynasty and managed to gain ascendency over the Pandyas and Cheras. The Chola dynasty, however, went into a period of decline from 4th century CE. This period coincided with the ascendency of the Kalabhras who moved down from the northern Tamil country displacing the established kingdoms and ruled over most of south India for almost 300 years.

Vijayalaya Chola revived the Chola dynasty in 850 CE by conquering Thanjavur by defeating Ilango Mutharaiyar and making it his capital. His son Aditya defeated the Pallava king Aparajita and extended the Chola territories to Tondaimandalam. The centres of the Chola Kingdom were at Kanchi (Kanchipuram) and Thanjavur. One of the most powerful rulers of the Chola kingdom was Raja Raja Chola, who ruled from 985 to 1014 CE. His army conquered the Navy of the Cheras at Thiruvananthapuram, and annexed Anuradhapura and the northern province of Ceylon. Rajendra Chola I completed the conquest of Sri Lanka, invaded Bengal, and undertook a great naval campaign that occupied parts of Malaya, Burma, and Sumatra. The Chola dynasty began declining by the 13th century and ended in 1279. Cholas were great builders and have left some of the most beautiful examples of early Tamil temple architecture. Brihadisvara Temple in Thanjavur is a fine example and has been listed as one of the United Nations sites.

Chera Dynasty

The Chera kingdom was one of the Tamil dynasties who ruled southern India from ancient times until around the 12th century CE. The Early Cheras ruled over the Malabar Coast, Coimbatore, Erode, Namakkal, Karur and Salem Districts in South India, which now forms part of the modern day Indian states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Throughout the reign of the Early Cheras, trade continued to bring prosperity to their territories, with spices, ivory, timber, pearls and gems being exported to the Middle East and to southern Europe. Evidence of extensive foreign trade from ancient times can be seen throughout the Malabar coast (Muziris), Karur and Coimbatore districts.

Satavahana Dynasty

The Śātavāhana Empire[5] was a royal Indian dynasty based from Amaravati in Andhra Pradesh as well as Junnar (Pune) and Prathisthan (Paithan) in Maharashtra. The territory of the empire covered much of India from 300 BCE onward. Although there is some controversy about when the dynasty came to an end, the most liberal estimates suggest that it lasted about 450 years, until around 220 CE. The Satavahanas are credited for establishing peace in the country, resisting the onslaught of foreigners after the decline of Mauryan Empire.

Sātavāhanas started out as feudatories to the Mauryan dynasty, but declared independence with its decline. They are known for their patronage of Hinduism. The Sātavāhanas were one of the first Indian states to issue coins struck with their rulers embossed. They formed a cultural bridge and played a vital role in trade as well as the transfer of ideas and culture to and from the Indo-Gangetic Plain to the southern tip of India.

They had to compete with the Shungas and then the Kanvas of Magadha to establish their rule. Later, they played a crucial role to protect a huge part of India against foreign invaders like the Sakas, Yavanas and Pahlavas. In particular their struggles with the Western Kshatrapas went on for a long time. The great rulers of the Satavahana Dynasty Gautamiputra Satakarni and Sri Yajna Sātakarni were able to defeat the foreign invaders like the Western Kshatrapas and stop their expansion. In the 3rd century CE the empire was split into smaller states.

Pallava Dynasty

The Pallavas were a great south Indian dynasty who ruled between the 3rd century CE until their final decline in the 9th century CE. Their capital was Kanchipuram in Tamil Nadu. Their origins are not clearly known. However, it is surmised that they were Yadavas and they probably were feudatories of Satavahanas. Pallavas started their rule from Krishna river valley, known today as Palnadu, and subsequently spread to southern Andhra Pradesh and north Tamil Nadu. Mahendravarman I was a prominent Pallava king who began work on the rock-cut temples of Mahabalipuram. His son Narasimhavarman I came to throne in 630 CE. He defeated the Chalukya king Pulakeshin II in 632 CE and burned the Chalukyan capital Vatapi. Pallavas and Pandyas dominated the southern regions of South India between the 6th and the 9th centuries CE.

Kadambas of Banavasi

Kadambas were one of the greatest kingdoms which ruled south India. Kadambas ruled during 345–525 CE. Their kingdom spanned the present day Karnataka state. Banavasi was their capital. They expanded their territories to cover Goa, Hanagal. The dynasty was founded by Mayura Sharma c. 345 CE. They built fine temples in Banavasi, Belgavi, Halsi and Goa. Kadambas were the first rulers to use Kannada as an administrative language as proven by the Halmidi inscription (450 CE) and Banavasi copper coin. With the rise of the Chalukya dynasty of Badami, the Kadambas ruled as their feudatory from 525 CE for another five hundred years.

Gangas of Talkad

The Western Ganga Dynasty ruled southern Karnataka region during 350–550 CE. They continued to rule until the 10th century as feudatories of Rashtrakutas and Chalukyas. They rose from the region after the fall of the Satavahana empire and created a kingdom for themselves in Gangavadi (south Karnataka) while the Kadambas, their contemporaries, did the same in north Karnataka. The area they controlled was called Gangavadi which included the present-day districts of Mysore, Chamrajanagar, Tumkur, Kolar, Mandya and Bangalore. They continued to rule until the 10th century as feudatories of Rashtrakutas and Chalukyas. Gangas initially had their capital at Kolar, before moving it to Talakad near Mysore. They made a significant contribution to Kannada literature with such noted writers as King Durvinita, King Shivamara II and Chavundaraya. The famous Jain monuments at Shravanabelagola were built by them.

Chalukya Dynasty

One of the first kings of the Chalukyan dynasty was Pulakeshin I. He ruled from Badami in Karnataka. His son Pulakeshin II became the king of the Chalukyan empire in 610 CE and ruled until 642 CE. Pulakeshin II is most remembered for the battle he fought and won against Emperor Harshavardhana in 637 CE. He also defeated the Pallava king Mahendravarman I. The Chalukya empire existed from 543–757 CE and an area stretching from Kaveri to Narmada rivers. The Chalukyas created the Chalukyan style of architecture. Great monuments were built in Pattadakal, Aihole and Badami. These temples exhibit the evolution of the Vesara style of architecture.

The Chalukyas of Vengi, also known as the Eastern Chalukyas, who were related to the Badami Chalukyas ruled along the east coast of South India around the present-day Vijayawada. The Eastern Chalukya dynasty was created by Kubja Vishnuvardhana, a brother of Pulakeshin II. The Eastern Chalukyas continued to rule for over five hundred years and were in close alliance with the Cholas.

Rashtrakuta Empire

The Rashtrakuta Empire ruled from Manyaketha in Gulbarga from 735 CE until 982 CE and reached its peak under Amoghavarsha I (814–878 CE), considered Ashoka of South India. The Rashtrakutas came to power at the decline of the Badami Chalukyas and were involved in a three-way power struggle for control of the Gangetic plains with the Prathihara of Gujarat and Palas of Bengal. The Rashtrakutas were responsible for building some of the beautiful rock-cut temples of Ellora including the Kailasa temple. Kannada language literature flourished during this period of Adikavi Pampa, Sri Ponna and Shivakotiacharya. King Amoghavarsha I wrote the earliest extant Kannada classic Kavirajamarga.

Western Chalukya Empire

The Western Chalukya Empire was created by the descendants of the Badami Chalukya clan and ruled from 973–1195 CE. Their capital was Kalyani, present day Basava Kalyana in Karnataka. They came to power at the decline of the Rashtrakutas. They ruled from the Kaveri in the South to Gujarat in the north. The empire reached its peak under Vikramaditya VI. The Kalyani Chalukyas promoted the Gadag style of architecture, excellent examples of which are present in Gadag, Dharwad, Koppal and Haveri districts of Karnataka. They patronised great Kannada poets such as Ranna and Nagavarma II and is considered as a golden age of Kannada literature. The Vachana Sahitya style of native Kannada poetry flourished during these times.

Hoysala Dynasty

Hoysalas began their rule as subordinates of the Chalukyas of Kalyani and gradually established their own empire. Nripa Kama Hoysala who ruled in the western region of Gangavadi, founded the Hoysala dynasty. His later successor Ballala I reigned from his capital at Belur. Vishnuvardhana Hoysala (1106–1152 CE) conquered the Nolamba region earning the title Nolambavadi Gonda. Some of the most magnificent specimens of South Indian temples are those attributed to the Hoysala dynasty of Karnataka. Vesara style reached its peak in their period. Hoysalas period is remembered today as one of the brightest periods in the history of Karnataka. They ruled Karnataka for over three centuries from c. 1000 to 1342 CE. The most famous kings among the Hoysalas were Vishnuvardhana, Veera Ballala II and Veera Ballala III. Jainism flourished during the Hoysala period. Ramanuja the founder of Shri Vaishnavism, came to Hoysala kingdom to spread his religion. Hoysalas encouraged both Kannada and Sanskrit literature and earned a great name as builders of temples at Belur, Halebidu, Somanathapura, Belavadi and Amrithapura. Such famous poets as Rudrabhatta, Janna, Raghavanka and Harihara wrote many classics in Kannada during this time.

Kakatiyas

The Kakatiya dynasty rose to prominence in the 11th century with the decline of the Chalukyas. By the early 12th century, the Kakatiya Durjaya clan declared independence and began expanding their kingdom.[6] By the end of the century, their kingdom had reached the Bay of Bengal and it stretched between the Godavari and the Krishna rivers. The empire reached its zenith under Ganapatideva who was its greatest ruler. At its largest, the empire included most of modern-day Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and parts of Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Chhattisgarh and Karnataka. Ganapatideva was succeeded by his daughter Rudramamba. The Kakatiya dynasty lasted for three centuries. Warangal was their capital. By the early 14th century, the Kakatiya dynasty attracted the attention of the Delhi Sultanate under Allauddin Khalji. It paid tribute to Delhi for a few years, but was eventually conquered by the forces of Muhammad bin Tughluq in 1323.[7][8][9][10]

Musunuri

After the downfall of Kakatiya empire, two cousins known as Musunuri Nayaks rebelled against Delhi Sultanate and recaptured Warangal and brought the whole of Telugu-speaking areas under their control. Although short lived (50 years), the Nayak rule is considered a watershed in the history of South India. Their rule inspired the establishment of Vijayanagar empire to defend Hindu dharma for the next five centuries.

Reddy Dynasty

The Reddy Dynasty was established by Prolaya Vema Reddy. The region that was ruled by the Reddy dynasty is now in Andhra Pradesh except some areas of Chitoor, Anantapur and Kurnool districts. Prolaya Vema Reddy was part of the confederation that started a movement against the invading Turkic Muslim armies of the Delhi Sultanate in 1323 CE and succeeded in repulsing them from Warangal. Reddys ruled coastal and central Andhra for over a hundred years from 1325 to 1448 CE. At its maximum extent, the Reddy kingdom stretched from Cuttak, Odisha to the north, Kanchi to the south and Srisailam to the west. The initial capital of the kingdom was Addanki. Later, it was moved to Kondavidu and subsequently to Rajahmundry. The Reddis were known for their fortifications. Two major hill forts, one at Kondapalli, 20 km north west of Vijayawada and another at Kondaveedu about 30 km west of Guntur stand testimony to the fort building skill of the Reddi kings. The forts of Bellamkonda, Vinukonda and Nagarjunakonda in the Palnadu region were also part of the Reddi kingdom.

The dynasty remained in power until the middle of the 15th century and was supplanted by the Gajapatis of Odisha, who gained control of coastal Andhra. The Gajapatis eventually lost control of coastal Andhra after Gajapati Prataprudra Deva was defeated by Krishna Deva Raya of Vijaynagar. The territories of the Reddi kingdom eventually came under the control of the Vijayanagara Empire.

Medieval history of South India

Rise of Islam

The early medieval period saw the rise of Islam in South India. The defeat of the Kakatiya dynasty of Warangal by the forces of the Delhi Sultanate in 1323 CE. and the defeat of the Hoysalas in 1333 CE. heralded a new chapter in South Indian history. The grand struggle of the period was between the Bahmani Sultanate based in Gulbarga and the Vijayanagara Empire with its capital in Vijayanagara in Karnataka. By the early 16th century, the Bahmani empire fragmented into five different kingdoms based in Ahmednagar, Berar, Bidar, Bijapur and Golconda, together called the Deccan Sultanates.

On the southwestern Coast of South India, a new local economical and political power arose into the vacuum created by the disintegration of Chera power. The Zamorins of Calicut, with the help of the Muslim-Arab merchants, dominated the maritime trade on Malabar Coast for the next few centuries.

Vijayanagara Empire

Differing theories have been proposed regarding the Vijayanagara empire's origins. Many historians propose Harihara I and Bukka Raya I, the founders of the empire, were Kannadigas and commanders in the army of the Hoysala Empire stationed in the Tungabhadra region to ward off Muslim invasions from the Northern India.[11][12][13][14] Others claim that they were Telugu people first associated with the Kakatiya kingdom who took control of the northern parts of the Hoysala Empire during its decline.[15] Irrespective of their origin, historians agree the founders were supported and inspired by Vidyaranya, a saint at the Sringeri monastery to fight the Muslim invasion of South India.[16][17] Writings by foreign travelers during the late medieval era combined with recent excavations in the Vijayanagara principality have uncovered much-needed information about the empire's history, fortifications, scientific developments and architectural innovations.[18][19]

Before the early 14th-century rise of the Vijayanagara Empire, the Hindu states of the Deccan, the Yadava Empire of Devagiri, the Kakatiya Kingdom of Warangal, the Pandyan Empire of Madurai, and the tiny kingdom of Kampili had been repeatedly invaded by Muslims from the north, and by 1336 they had all been defeated by Alauddin Khalji and Muhammad bin Tughluq, the Sultans of Delhi. The Hoysala Empire was the sole remaining Hindu state in the path of the Muslim invasion.[20] After the death of Hoysala king Veera Ballala III during a battle against the Sultan of Madurai in 1343, the Hoysala Empire merged with the growing Vijayanagara empire.

In the first two decades after the founding of the empire, Harihara I gained control over most of the area south of the Tungabhadra river and earned the title of Purvapaschima Samudradhishavara ("master of the eastern and western seas"). By 1374 Bukka Raya I, successor to Harihara I, had defeated the chiefdom of Arcot, the Reddys of Kondavidu, the Sultan of Madurai and gained control over Goa in the west and the Tungabhadra-Krishna River doab in the north.[21][22] The original capital was in the principality of Anegondi on the northern banks of the Tungabhadra River in today's Karnataka. It was later moved to nearby Vijayanagara on the river's southern banks during the reign of Bukka Raya I.

With the Vijayanagara Kingdom now imperial in stature, Harihara II, the second son of Bukka Raya I, further consolidated the kingdom beyond the Krishna River and brought the whole of South India under the Vijayanagara umbrella.[23] The next ruler, Deva Raya I, emerged successful against the Gajapatis of Odisha and undertook important works of fortification and irrigation.[24] Deva Raya II (called Gajabetekara)[25] succeeded to the throne in 1424 and was possibly the most capable of the Sangama dynasty rulers.[26] He quelled rebelling feudal lords as well as the Zamorin of Calicut and Quilon in the south. He invaded the island of Lanka and became overlord of the kings of Burma at Pegu and Tanasserim.[27][28][29] The empire declined in the late 15th century until the serious attempts by commander Saluva Narasimha Deva Raya in 1485 and by general Tuluva Narasa Nayaka in 1491 to reconsolidate the empire.

After nearly two decades of conflict with rebellious chieftains, the empire eventually came under the rule of Krishna Deva Raya, the son of Tuluva Narasa Nayaka.[30] In the following decades the Vijayanagara empire dominated all of Southern India and fought off invasions from the five established Deccan Sultanates.[31][32] The empire reached its peak during the rule of Krishna Deva Raya when Vijayanagara armies were consistently victorious.[33] The empire annexed areas formerly under the Sultanates in the northern Deccan and the territories in the eastern Deccan, including Kalinga, while simultaneously maintaining control over all its subordinates in the south.[34] Many important monuments were either completed or commissioned during the time of Krishna Deva Raya.[35]

Krishna Deva Raya was followed by his younger brother Achyuta Deva Raya in 1529 and in 1542 by Sadashiva Raya while the real power lay with Aliya Rama Raya, the son-in-law of Krishna Deva Raya, whose relationship with the Deccan Sultans who allied against him has been debated.[36]

The sudden capture and killing of Aliya Rama Raya in 1565 at the Battle of Talikota, against an alliance of the Deccan sultanates, after a seemingly easy victory for the Vijayanagara armies, created havoc and confusion in the Vijayanagara ranks, which were then completely routed. The Sultanates' army later plundered Hampi and reduced it to the ruinous state in which it remains; it was never re-occupied. Tirumala Deva Raya, Rama Raya's younger brother who was the sole surviving commander, left Vijayanagara for Penukonda with vast amounts of treasure on the back of 1500 elephants.[37]

The empire went into a slow decline regionally, although trade with the Portuguese continued, and the British were given a land grant for the establishment of Madras.[38][39] Tirumala Deva Raya was succeeded by his son Sriranga I later followed by Venkata II who was the last great king of Vijayanagara empire, made his capital Chandragiri and Vellore, repulsed the invasion of the Deccan Sultanates and saved Penukonda from being captured.[40]

His successor Rama Deva Raya took power and ruled until 1632, after whose death Venkata III became king and ruled for about ten years. The empire was finally conquered by the Sultanates of Bijapur and Golkonda.[40] The largest feudatories of the Vijayanagar empire – the Nayaks of Gandikota, the Mysore Kingdom, Keladi Nayaka, Nayaks of Madurai, Nayaks of Tanjore, Nayakas of Chitradurga and Nayak Kingdom of Gingee palegars of gummanayakanapalya – declared independence and went on to have a significant impact on the history of South India in the coming centuries. These Nayaka kingdoms lasted into the 18th century while the Mysore Kingdom remained a princely state until Indian Independence in 1947 although they came under the British Raj in 1799 after the death of Tipu Sultan.[41]

Nayak kingdoms

Vijayangara empire had established military and administrative governors called Nayakas to rule in the various territories of the empire. After the demise of the Vijayanagara empire, the local governors declared their independence and started their rule. The Nayak of Madurai, Nayaks of Tanjore, Keladi Nayakas of Shimoga, Nayakas of Chitradurga and Kingdom of Mysore were the most prominent of them. Raghunatha Nayak (1600–1645) was the greatest of the Tanjavur Nayaks. Raghunatha Nayak encouraged trade and permitted a Danish settlement in 1620 at Danesborg at Tarangambadi. This laid the foundation of future European involvement in the affairs of the country. The success of the Dutch inspired the English to seek trade with Thanjavur, which was to lead to far-reaching repercussions. Vijaya Raghava (1631–1675 CE) was the last of the Thanjavur Nayaks. Nayaks reconstructed some of the oldest temples in the country and their contributions can be seen even today. Nayaks expanded the existing temples with large pillared halls, and tall gateway towers was a striking feature in the religious architecture of this period. Kantheerava Narasaraja Wodeyar and Tipu Sultan from the Kingdom of Mysore, Madhakari Nayaka of Chitradurga Nayaka clan and Venkatappa Nayaka of Keladi dynasty are the most famous among the post Vijayanagar rulers from Kannada country.

In Madurai, Thirumalai Nayak was the most famous Nayak ruler. He patronised art and architecture creating new structures and expanding the existing landmarks in and around Madurai. His landmark buildings are the Meenakshi Temple Gopurams and Thirumalai Nayak Palace in Madurai. On Thirumalai Nayak's death in 1659 CE, other notable ruler was Rani Mangammal. Shivaji Bhonsle, the great Maratha Ruler, invaded the south, as did Chikka Deva Raya of Mysore and other Muslim Rulers, resulting in chaos and instability and the Madurai Nayak Kingdom collapsed in 1736 following internal strife.

The Tanjavur Nayaks ruled till late 17th century until their dynasty was put to an end by Madurai Rulers, and the Marathas grabbing the opportunity to install their ruler. The Tanjavur Nayak kings were notable for their contribution to Arts and Telugu literature.

Maratha Empire

The Maratha Empire or the Maratha Confederacy was an Indian imperial power that existed from 1674 to 1818. At its peak, the empire covered much of the subcontinent, encompassing a territory of over 2.8 million km². The Marathas are credited with ending the Mughal rule in India.[42]

The Marathas were a yeoman Hindu warrior group from the western Deccan (present day Maharashtra) that rose to prominence by establishing 'Hindawi Swarajya'. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica: The Maratha group of castes is a largely rural class of peasant cultivators, landowners, and soldiers. The Marathas became prominent in the 17th century under the leadership of Chhatrapathi Shivaji Raje Bhosale who revolted against the Bijapur Sultanate and the Mughal Empire, and carved out a rebel territory with Raigad as his stronghold.[43] Known for their mobility, the Marathas were able to consolidate their territory during the Deccan Wars against the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb and, later in time, controlled a large part of India.[44]

Shahu, a grandson of Chhatrapathi Shivaji, was released by the Mughals after the death of Aurangzeb. Following a brief struggle with his aunt Tarabai, Shahu became ruler. During this period, he appointed Balaji Vishwanath Bhat and later his descendants as the Deshasth Peshwas (Warriors) or the prime ministers of the Maratha Empire. After the death of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, the empire expanded greatly under the rule of the Peshwas. The empire at its peak stretched from Tamil Nadu[45][46] in the south Tanjavur of Tamil nadu, to Peshawar(modern-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) in the north, and Bengal and Andaman Islands in east.[47][48] The rise of Maratha military power under Chatrapathi Shivaji and his heirs in the immediate north of what is today considered South India had a profound influence on the political situation of South India, with Maratha control quickly extending as far east as Ganjam and as far south as Thanjavur. Following the death of Aurangzeb, Mughal power withered, and South Indian rulers gained autonomy from Delhi. The Wodeyar kingdom of Mysore, which was originally in tribute to Vijayanagara and gained in strength over the next few decades, subsequently emerging as the dominant power in the southern part of South India. The Asaf Jahis of Hyderabad controlled the territory north and east of Mysore, while the Marathas controlled portions of Karnataka. By the close of the "medieval" period, most of South India was either autonomy under Maratha ruled directly from, or under tribute to Nayak dynasty or Wodeyars.

Modern history

Colonial period

In the middle of the 18th century, the French and the British East India company initiated a protracted struggle for military control of South India. The period was marked by shifting alliances between the two East India companies and the local powers, mercenary armies employed by all sides, and general anarchy in South India. Cities and forts changed hands many times, and soldiers were primarily remunerated through loot. The four Anglo-Mysore Wars and the three Anglo-Maratha Wars saw Mysore, the Marathas and Hyderabad aligning themselves in turns with either the British or the French. Eventually, British power in alliance with Hyderabad prevailed and Mysore was absorbed as a princely state within British India. The Nizam of Hyderabad sought to retain his autonomy through diplomacy rather than open war with the British. The Maratha Empire that stretched across large swathes of central and northern India was broken up, with most of it annexed by the British.

British South India

South India during the British colonial rule was divided into the Madras Presidency and Hyderabad, Mysore, Thiruvithamcoore (also known as Travancore), Cochin, Vizianagaram and a number of other minor princely states. The Madras Presidency was ruled directly by the British, while the rulers of the princely states enjoyed considerable internal autonomy. British Residents were stationed in the capitals of the important states to supervise and report on the activities of the rulers. British troops were stationed in cantonments near the capitals to curb the potential of rebellion. The rulers of these states accepted the principle of paramountcy of the British Crown. The larger princely states issued their own currency and built their own railroads—with non-standard gauges which would be incompatible with their neighbors. The cultivation of coffee and tea was introduced to the mountainous regions of South India during the British period, and both remain important cash crops.

After independence

On 15 August 1947, the former British India achieved independence as the new dominions of India and Pakistan. The rulers of India's princely states acceded to the government of India between 1947 and 1950, and South India was organized into a number of new states. Most of South India was included in Madras state, which included the territory of the former Madras Presidency together with the princely states of Banganapalle, Pudukkottai, and Sandur. The other states in South India were Coorg (the erstwhile Coorg province of British India), Mysore State (the former princely state of Mysore) and Travancore-Cochin, formed from the merger of the princely states of Travancore and Cochin. The former princely state of Hyderabad became Hyderabad State, and erstwhile Bombay Presidency became Bombay State.

In 1953, the Jawaharlal Nehru government yielded to intense pressure from the northern Telugu-speaking districts of Madras State, and allowed them to vote to create India's first linguistic state. Andhra State was created on 1 November 1953 from the northern districts of Madras State, with its capital in Kurnool. Increasing demands for reorganisation of the patchwork of India's states resulted in the formation of a national States Reorganisation Commission. Based on the commission's recommendations, the Parliament of India enacted the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, which reorganized the boundaries of India's states along linguistic lines. Andhra State was renamed Andhra Pradesh, and enlarged by the addition of Telugu-speaking region of Telangana, formerly part of Hyderabad State. Mysore State was enlarged by the addition of Coorg and the Kannada-speaking districts of southwestern Hyderabad State and southern Bombay State. The new Malayalam-speaking state of Kerala was created by the merger of Travancore-Cochin with Malabar and Kasargod districts of Madras State. Madras State, which after 1956 included the Tamil-majority regions of South India, changed its name to Tamil Nadu in 1968, and Mysore State was renamed Karnataka in 1972. Portuguese India, which included Goa, was annexed by India in 1961, and Goa became a state in 1987. The enclaves of French India were ceded to India in the 1950s, and the southern four were organised into the union territory of Puducherry.

See also

- Ancient India

- History of Tamil Nadu

- Ancient Tamil country

- History of Karnataka

- Political history of medieval Karnataka

- History of Andhra Pradesh

- History of Kerala

References

- ^ One such site was found at Krishnagiri in Tamil Nadu—"Steps to preserve megalithic burial site". The Hindu, Oct 6, 2006. Chennai, India: The Hindu Group. 6 October 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ^ K. A. N. Sastri, A History of South India, pp. 49–51

- ^ Murty, M. L. K. (2003). Pre- and Protohistoric Andhra Pradesh up to 500 B.C. ISBN 9788125024750.

- ^ Front Page : Some pottery parallels. The Hindu (2007-05-25). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ^ Woolner, Alfred C. (1928). Introduction to Prakrit. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 235 pages(see page:15). ISBN 9788120801899.

- ^ The History of Andhras, Durga Prasad Archived 2007-03-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sinopoli, Carla M. (2003). The Political Economy of Craft Production: Crafting Empire in South India, c.1350–1650. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 9781139440745. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ Gade, Dr Jayaprakashnarayana. Water Resources and Tourism Promotion in Telangana State. ISBN 9789385886041.

- ^ Hari Saravanan, V. (2014). Gods, Heroes and their Story Tellers: Intangible cultural heritage of South India. ISBN 9789384391492.

- ^ Raman, K. V. (June 2003). Sri Varadarajaswami Temple, Kanchi: A Study of Its History, Art and Architecture. ISBN 9788170170266.

- ^ Historians such as P. B. Desai (History of Vijayanagar Empire, 1936), Henry Heras (The Aravidu Dynasty of Vijayanagara, 1927), B.A. Saletore (Social and Political Life in the Vijayanagara Empire, 1930), G.S. Gai (Archaeological Survey of India), William Coelho (The Hoysala Vamsa, 1955) and Kamath (Kamath 2001, pp157–160)

- ^ Karmarkar (1947), p30

- ^ Kulke and Rothermund (2004), p188

- ^ Rice (1897), p345

- ^ Robert Sewell (A Forgotten Empire Vijayanagar: A Contribution to the History of India, 1901), Nilakanta Sastri (1955), N. Ventakaramanayya (The Early Muslim expansion in South India, 1942) and B. Surya Narayana Rao (History of Vijayanagar, 1993) in Kamath (2001) pp157–160.

- ^ Nilakanta Sastry (1955), p216

- ^ Kamath (2001), p160

- ^ Portuguese travellers Barbosa, Barradas and Italian Varthema and Caesar Fredericci in 1567, Persian Abdur Razzak in 1440, Barani, Isamy, Tabataba, Nizamuddin Bakshi, Ferishta and Shirazi and vernacular works from the 14th to 16th centuries. (Kamath 2001, pp157–158)

- ^ Fritz & Michell (2001) pp1–11

- ^ Nilakanta Sastri (1955), p216

- ^ Kamath (2001), p162

- ^ Nilakanta Sastri (1955), p317

- ^ The success was probably also due to the peaceful nature of Muhammad II Bahmani, according to Nilakanta Sastri (1955), p242

- ^ From the notes of Portuguese Nuniz. Robert Sewell notes that a big dam across was built the Tungabhadra and an aqueduct 15 miles (24 km) long was cut out of rock (Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p243).

- ^ Also deciphered as Gajaventekara, a metaphor for "great hunter of his enemies", or "hunter of elephants" (Kamath 2001, p163).

- ^ Nilakanta Sastri (1955), p244

- ^ From the notes of Persian Abdur Razzak. Writings of Nuniz confirms that the kings of Burma paid tributes to Vijayanagara empire (Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p245)

- ^ Kamath (2001), p164

- ^ From the notes of Abdur Razzak about Vijayanagara: a city like this had not been seen by the pupil of the eye nor had an ear heard of anything equal to it in the world (Hampi, A Travel Guide 2003, p11)

- ^ Nilakanta Sastri (1955), p250

- ^ Nilakanta Sastri (1955), p239

- ^ Kamath (2001), p159

- ^ From the notes of Portuguese traveler Domingo Paes about Krishna Deva Raya: A king who was perfect in all things (Hampi, A Travel Guide 2003, p31)

- ^ The notes of Portuguese Barbosa during the time of Krishna Deva Raya confirms a very rich and well provided Vijayanagara city (Kamath 2001, p186)

- ^ Most monuments including the royal platform (Mahanavami Dibba) were actually built over a period spanning several decades (Dallapiccola 2001, p66)

- ^ Dr. P. B. Desai asserts that Rama Raya's involvement often was at the insistence of one Sultan or the other (Kamath 2001, p172).

- ^ Some scholars say the war was actually fought between Rakkasagi and Tangadigi in modern Bijapur district, close to Talikota, and the battle is also called "Battle of Rakkasa-Tangadi". Shervani claimed that the actual venue of the battle was Bannihatti (Kamath 2001, p170)

- ^ The Telugu work Vasucharitamu refers to Aravidu King Tirumala Deva Raya (1570) as the reviver of the Karnata Empire.(Ramesh 2006)

- ^ Nilakanta Sastri (1955), p268

- ^ a b Kamath (2001), p174

- ^ Kamath (2001), p220, p226, p234

- ^ "The Marathas". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ^ Vartak, Malavika (8–14 May 1999). "Shivaji Maharaj: Growth of a Symbol". Economic and Political Weekly. 34 (19): 1126–1134. JSTOR 4407933. (subscription required)

- ^ Maratha (people) – Encyclopædia Britannica. Global.britannica.com. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Mehta, J. L. Advanced study in the history of modern India 1707–1813

- ^ Mackenna, P. J. et al. Ancient and modern India

- ^ Andaman & Nicobar Origin | Andaman & Nicobar Island History Archived 15 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Andamanonline.in. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Welcome to Alibag / Alibaug. Sarkhel Kanhoji Angre. Marathiecards.com. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

Further reading

- Rao, Velcheru Narayana, David Shulman, and Sanjay Subrahmanyam. Textures of Time: Writing History in South India 1600–1800 (2003)

- Nilakanta Sastri, K. A. (2000). A History of South India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Nilakanta Sastri, K. A.; Srinivasachari (2000). Advanced History of India. New Delhi: Allied Publishers Ltd.

- Chandra, Bipin (1999). The India after Independence. New Delhi: Penguin.