Darwin D. Martin House

Darwin D. Martin House Complex | |

| |

Interactive map showing the Martin House | |

| Location | 125 Jewett Parkway, Buffalo, New York |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°56′10.18″N 78°50′53.27″W / 42.9361611°N 78.8481306°W |

| Built | 1903–1905 |

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Architectural style | Prairie School |

| NRHP reference No. | 86000160 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | 1975[1] |

| Designated NHL | 1986[1] |

The Darwin D. Martin House Complex is a historic house museum in Buffalo, New York. The property's buildings were designed by renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright and built between 1903 and 1905. The house is considered to be one of the most important projects from Wright's Prairie School era.[2]

History

The Martin House Complex was built for businessman Darwin D. Martin, his wife, and their family; and his sister Delta and her husband George F. Barton.[3][4]

Martin and his brother, William E. Martin, were co-owners of the E-Z Stove Polish Company based in Chicago.[5] In 1902 William commissioned Wright to build him a home in Oak Park, Illinois, the resultant William E. Martin House built in 1903.[5] Upon viewing his brother's home, Darwin Martin was significantly impressed to visit Wright's Studio, and persuaded Wright to view his property in Buffalo, where he planned to build two houses.[5]

In 1904, Martin was instrumental in selecting Wright as the architect for the Larkin Administration Building,[5] in downtown Buffalo, which was Wright's first major commercial project. Martin was the secretary of the Larkin Soap Company and consequently Wright designed houses for other Larkin employees William R. Heath and Walter V. Davidson. Wright also designed the E-Z Stove Polish Company's Factory built in 1905.[5]

Wright designed the complex as an integrated composition of connecting buildings, consisting of the primary building, the Martin House, a long pergola connecting with a conservatory, a carriage house-stable, and a smaller residence, the George Barton House, built for George F. Barton and his wife Delta, Martin's sister. The complex also includes a gardener's cottage, the last building completed.

Martin, disappointed with the small size of the conservatory, had a 60 ft (18m) long greenhouse constructed between the gardener's cottage and the carriage house, to supply flowers and plants for the buildings and grounds. This greenhouse was not designed by Wright, and Martin ignored Wright's offer "to put a little architecture on it".[6]

Over the next twenty years a long-term friendship grew between Wright and Martin, to the extent that the Martins provided financial assistance[7] and other support[8][9] to Wright as his career unfolded.

About twenty years later, in 1926, Wright designed the second major complex for the Martin family, Graycliff, a summer estate overlooking Lake Erie in nearby Derby, New York.[10] The Blue-Sky Mausoleum Wright designed for the Martins in 1928, but never built, was finally installed at Buffalo's Forest Lawn Cemetery in 2004.[11]

Design

The complex exemplifies Wright's Prairie School ideal and is comparable with other notable works from this period in his career, such as the Robie House in Chicago and the Dana-Thomas House in Springfield, Illinois. Wright was especially fond of the Martin House design, referring to it for some 50 years as his "opus", and calling the complex "A well-nigh perfect composition". Wright kept the Martin site plan tacked to the wall near his drawing board for the next half century.[12][13]

The main motives and indications were:

First – To reduce the number of necessary parts of the house and the separate rooms to a minimum, and make all come together as an enclosed space—so divided that light, air and vista permeated the whole with a sense of unity.

— Frank Lloyd Wright, "On architecture".[14]

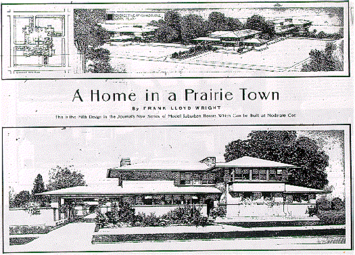

In 1900 Edward Bok of the Curtis Publishing Company, bent on improving American homes, invited architects to publish designs in the Ladies' Home Journal, the plans of which readers could purchase for five dollars.[15] Subsequently, the Wright design "A Home in a Prairie Town" was published in February 1901 and first introduced the term "Prairie Home".[15] The Martin House, designed in 1903, bears a striking resemblance to that design.[15] The facades are almost identical, except for the front entrance, and the Martin House repeats most of the Journal House ground floor.[15] An awkward failure was no direct connection from the kitchen to the dining room.[15] The Journal House had a serving pantry, but Wright was forced to give this up to accommodate the pergola.[15]

Of particular significance are the fifteen distinctive patterns of 394 stained glass windows that Wright designed for the entire complex, some of which contain over 750 individual pieces of jewel-like iridescent glass, that act as "light screens" to visually connect exterior views with the spaces within. More patterns of art glass were designed for the Martin House than for any other of Wright's Prairie Houses.

Walter Burley Griffin landscaped the grounds, which were created as integral to the architectural design.[16] A semi-circular garden which contained a wide variety of plant species, chosen for their blossoming cycles to ensure blooms throughout the growing season, surrounded the Martin House veranda.[16] The garden included two sculptures by Wright collaborator Richard Bock.[17]

Complex

The complex is located within the Parkside East Historic District of Buffalo, which was laid out by the American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted in 1876.[16] Darwin Martin purchased the land in 1902.[16] Construction began in 1903, and completed with Wright signing off on the project in 1907.[16] The original complete Martin House Complex was 29,080 square feet (2,702 m2).[16]

The Martin House

Built between 1902 and 1905,[16] the Martin House is distinguished from Wright's other prairie style houses by its unusually large size and open plan.[18][19] On the ground floor an entry hall bisects the house. To the right, behind a large double sided hearth, is a central living room. The room is flanked by a dining room and library which together create a long continuous space. The other axis, centered on the hearth, continues the living room out to a large covered veranda.[15] To the left of the entry hall, is a reception room similar in size to the living room, the kitchen, and several smaller rooms. A separate mass provides for a reception room hearth, and one to the level above. The wing completes with a porte-cochère balancing the veranda.[15] Above the entry hall, stairs wrap a small covered light well opening to the second floor. This floor provides eight bedrooms, four bathrooms, and a sewing room.[19] The entry hall continues on axis to the pergola and conservatory beyond.

Martin had imposed no budget and Wright is believed to have spent close to $300,000.[5][20] By comparison Martin's brother's house cost about $5000,[21] and the Ladies' Home Journal house design an estimated price of $7000.[15]

The Martin House is located at the south end of the complex,[22] at 125 Jewett Parkway in Buffalo.[16]

The Barton House

Construction on the Barton House began first in 1903[16] and not only was it the first building of the complex to be completed but also the first of Wright's in Buffalo.[18] The principal living spaces are concentrated in the central two-story portion of the house where the reception, living and dining areas open into each other.[18] The two main bedrooms are on the second story, at either end of a narrow hall.[18] On the ground floor the kitchen is at the north end, while a scaled veranda extends from the reception hall to the south.[18]

The Barton House is on the east side of the complex,[22] at 118 Summit Avenue, Buffalo.[16]

The carriage house

Originally the carriage house served as a stable with horse stalls, a hay loft, and storage for a carriage, but soon became a garage with a service area for a car, and an upstairs apartment for a chauffeur.[23] The carriage house also contained the boilers for the complex's heating system.[23] Built between 1903 and 1905,[23] the original structure was demolished in 1962, and rebuilt during the restoration between 2004 and 2007.[16] The carriage house is at the north end of the complex,[22] directly north of the Martin House porte-cochere, to the west of the conservatory.

The gardener's cottage

Built in 1909[16] of wood and stucco,[24] the gardener's cottage is so modest in size that a boxy configuration appears to have been inevitable, contrary to Wright's ideal of opening up the confining "box" of traditional American houses.[24] Nevertheless, Wright managed to create an illusion of the pier and cantilever principle that characterized the Martin House by placing tall rectangular panels at each corner of the building.[24] The gardener was Reuben Polder, who had to provide fresh flowers daily for every room in the Martin House, a task which he completed until Darwin Martin died in 1935.[24]

The gardener's cottage is on the west side of the complex,[22] at 285 Woodward Avenue, Buffalo.[24]

The conservatory

Built for plant growing the conservatory features a glass-and-metal roof supported by brick piers.[25] A plaster cast of the Winged Victory of Samothrace stands at the entrance and creates a vista through the pergola.[15] The original conservatory was demolished in 1962, and rebuilt between 2004 and 2007 as part of the restoration.[16] The conservatory is at the north end of the complex between the carriage house and the Barton House.[22]

The pergola

The pergola runs from the entrance hall of the Martin House to the entrance of the conservatory,[15] and is about 100 ft (30m) long.[26] The original pergola was demolished in 1962, and was rebuilt between 2004 and 2007.[16] The Pergola is at the center of the complex, running north–south between the Martin House and the conservatory.[22]

Gallery of drawings

-

Landscape plan

-

1916 map of the Martin House complex

-

1901 illustration

-

First floor

-

Second floor

Decline

Following the loss of the family fortune, due to the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the Great Depression,[8] and subsequently Darwin Martin's death in 1935,[16] the family abandoned the house in 1937.[16] Martin's son, D.R. Martin, had attempted to donate the house to the city of Buffalo or the state university to be used as a library but his offer was rejected.[27] By 1937 the complex had already begun to deteriorate, the walls at the front of the house were crumbling, and the conservatory hadn't been used for several years due to a leak in the heating system.[28] Over the next two decades, the vacant house was considerably vandalized and deteriorated further. In 1946 the city took control over the property in a tax foreclosure sale.[27] Purchased in 1951 by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Buffalo, with plans to turn the complex into a summer retreat for their priests, it remained empty.[27] 1951 was also the year Graycliff was sold to the Piarists, a Catholic teaching order.[29] The complex was purchased privately in 1955 by architect Sebastian Tauriello, thus saving the house from demolition.[16] It was converted into three apartments,[27] the grounds sub-divided, with the carriage house, conservatory, and pergola in ruins at the time of the private purchase, demolished, and a pair of apartment buildings constructed in the 1960s.[27] In 1967 the complex was purchased by the University at Buffalo, for use as the university president's residence.[16] The university continued the sub-division with the sale of The Barton House in 1967[16] and the gardener's cottage soon after. The university attempted restoration of the Martin House, although this consisted mainly of slight modernizations and the location of several pieces of original furniture.[27] The complex was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975,[16] and became a National Historic Landmark in 1986.[30][31]

Restoration

The Martin House Restoration Corporation (MHRC), founded in 1992,[32] is a non-profit organization with a mandate to restore the complex to its 1907 condition and to open it as a public historic house museum.[32] The Barton House was purchased on behalf of the MHRC in 1994 and the title to the Martin House was transferred from the University at Buffalo to the MHRC in 2002.[16] The restoration began with the Buffalo firm Hamilton Houston Lownie Architects (HHL) being commissioned to restore the roof of the Martin House. The Gardener's Cottage was purchased in 2006, and the demolished carriage house, conservatory, and pergola were reconstructed and completed in 2007.[16] The $50 million restoration project was completed in June 2017. It was the first time that a demolished Wright structure had been rebuilt in the United States.[citation needed]

One of Richard Bock's sculptures, Spring, now located in the Bock Museum at Greenville College, was copied in 2008.[33]

Currently the MHRC operates guided public tours and present educational programs for volunteers and the general public. In 2008, the Gardener's Cottage was finally included on the tours of the complex.

The Eleanor & Wilson Greatbatch Pavilion Visitor Center, designed by Toshiko Mori, opened March 12, 2009.[34]

In June 2017, the unveiling of the Wisteria Mosaic Fireplace, a 360-degree work of art consisting of tens of thousands of individual glass tiles, marks the completion of the $50 million project.

See also

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York

- List of New York State Historic Sites

- Other buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright in the Buffalo area:

References

- ^ a b Martin 02/02/2015 (PDF)

- ^ "An American Legacy: Architecture, Craft, and Design in Upstate New York". wrightwaytravel.org. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- ^ "Learn: The Story". Frank Lloyd Wright's Martin House Complex. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ^ "George and Delta Barton House". Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Edgar Tafel, Years with Frank Lloyd Wright: Apprentice to Genius, p.83, Courier Dover Publications; 1985

- ^ Buckham, Tom (June 21, 2006). "Darwin Martin complex to include working greenhouse". The Buffalo News. p. B1.

- ^ Robert M. Craig, Bernard Maybeck at Principia College, p.478, Gibbs Smith; 2004

- ^ a b Quinan, Jack (2004). Frank Lloyd Wright's Martin House. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 216.

- ^ Knight, Caroline (2004). Frank Lloyd Wright. Parragon. p. 124.

- ^ "Graycliff Official Site". Archived from the original on September 18, 2006.

- ^ "Blue-Sky Mausoleum Official Site". Archived from the original on July 20, 2009.

- ^ McCarter, Robert (2006). Frank Lloyd Wright. Reaktion Books. p. 58. ISBN 9781861895387 – via Google books.

- ^ "Visit the Martin House". www.darwinmartinhouse.org. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- ^ Wright, Frank Lloyd (1960). Frank Lloyd Wright: Writings and Buildings. New American Library. p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gill, Brendan (1998). Many Masks. Da Capo Press. pp. 147–149.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Martin House Reference Sheet, archived from the original on March 26, 2009, retrieved February 10, 2013

- ^ Lind, Carla. Frank Lloyd Wright's Furnishing.

- ^ a b c d e Banham, Reyner; Kowsky, Francis R. (1981). Buffalo Architecture. Buffalo Architectural Guidebook Corporation. pp. 195–197.

- ^ a b Storrer, William A. (2002). The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. University of Chicago Press. pp. 99–100.

- ^ Gill, Brendan (1998). Many Masks. Da Capo Press. p. 172.

- ^ Gill, Brendan (1998). Many Masks. Da Capo Press. p. 141.

- ^ a b c d e f "Complex Model". www.buffaloah.com.

- ^ a b c "The Carriage House". buffaloah.com.

- ^ a b c d e "The gardener's cottage". buffaloah.com.

- ^ Quinan, Jack (2004). Frank Lloyd Wright's Martin House. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 13.

- ^ "landmarksociety.org". Archived from the original on January 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Tafel, Edgar (1985). Years with Frank Lloyd Wright: Apprentice to Genius. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 92–93.

- ^ Tafel, Edgar (1985). Years with Frank Lloyd Wright: Apprentice to Genius. Courier Dover Publications. p. 88.

- ^ "Greycliff official Site timeline". Archived from the original on September 3, 2009.

- ^ "Darwin D. Martin House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- ^ Pitts, Carolyn (n.d.). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Darwin D. Martin House". National Park Service.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) and Accompanying Photos, exterior, from 1910 and 1975. (1.97 MB) - ^ a b "The Martin House Restoration Corporation". Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- ^ "Replica of Bock Sculpture, 'Spring,' Being Made from G.C.'s Original". The Greenville Advocate. November 4, 2008.

- ^ "$2.5 million gift for Martin House Visitor Center bestows it with its name: "The Eleanor and Wilson Greatbatch Pavilion"". Frank Lloyd Wright's Martin House Complex. Martin House Restoration Corporation. January 26, 2008. Archived from the original on May 16, 2009. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

External links

- Official website

- NYS Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation: Darwin Martin House State Historic Site

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. NY-5611, "Darwin D. Martin House, 125 Jewett Parkway, Buffalo, Erie County, NY", 15 photos, 27 measured drawings, 14 data pages

- Darwin D. Martin Photograph Collection Archived October 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine at University at Buffalo Libraries Digital Collections

- Darwin D. Martin Photograph Collection from New York Heritage

- 1905 establishments in New York (state)

- Architecture of Buffalo, New York

- Frank Lloyd Wright buildings

- Historic American Buildings Survey in New York (state)

- Historic house museums in New York (state)

- Houses completed in 1905

- Houses in Buffalo, New York

- Houses on the National Register of Historic Places in New York (state)

- National Historic Landmarks in New York (state)

- Museums in Buffalo, New York

- National Register of Historic Places in Buffalo, New York

- New York (state) historic sites