American imperialism

| History of the United States expansion and influence |

|---|

| Colonialism |

|

|

| Militarism |

|

|

| Foreign policy |

|

| Concepts |

American imperialism consists of policies aimed at extending the political, economic, and cultural influence of the United States over areas beyond its boundaries. Depending on the commentator, it may include military conquest, gunboat diplomacy, unequal treaties, subsidization of preferred factions, economic penetration through private companies followed by intervention when those interests are threatened, or regime change.[4][page needed]

The policy of imperialism is usually considered to have begun in the late 19th century.[5] The federal government of the United States has never referred to its territories as an empire, but some commentators refer to it as such, including Max Boot, Arthur Schlesinger, and Niall Ferguson.[6] The United States has also been accused of neocolonialism, sometimes defined as a modern form of hegemony, which uses economic rather than military power, and sometimes used as a synonym for contemporary imperialism.

History

Overview

Despite periods of peaceful co-existence, wars with Native Americans resulted in substantial territorial gains for American colonists who were expanding into native land. Wars with the Native Americans continued intermittently after independence, and an ethnic cleansing campaign known as Indian removal gained for European-American settlers more valuable territory on the eastern side of the continent.

George Washington began a policy of United States non-interventionism which lasted into the 1800s. The United States promulgated the Monroe Doctrine in 1821, in order to stop further European colonialism and to allow the American colonies to grow further, but desire for territorial expansion to the Pacific Ocean was explicit in the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. The giant Louisiana Purchase was peaceful, but the Mexican–American War of 1846 resulted in the annexation of 525,000 square miles of Mexican territory.[7][8] Elements attempted to expand pro-U.S. republics or U.S. states in Mexico and Central America, the most notable being fillibuster William Walker's Republic of Baja California in 1853 and his intervention in Nicaragua in 1855. Senator Sam Houston of Texas even proposed a resolution in the Senate for the "United States to declare and maintain an efficient protectorate over the States of Mexico, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, and San Salvador." The idea of U.S. expansion into Mexico and the Caribbean was popular among politicians of the slave states, and also among some business tycoons in the Nicarauguan Transit (the semi-overland and main trade route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans before the Panama Canal). President Ulysses S. Grant attempted to Annex the Dominican Republic in 1870, but failed to get the support of the Senate.

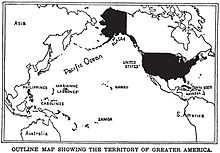

Non-interventionism was wholly abandoned with the Spanish–American War. The United States acquired the remaining island colonies of Spain, with President Theodore Roosevelt defending the acquisition of the Philippines. The U.S. policed Latin America under Roosevelt Corollary, and sometimes using the military to favor American commercial interests (such as intervention in the banana republics and the annexation of Hawaii). Imperialist foreign policy was controversial with the American public, and domestic opposition allowed Cuban independence, though in the early 20th century the U.S. obtained the Panama Canal Zone and occupied Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The United States returned to strong non-interventionist policy after World War I, including with the Good Neighbor policy for Latin America. After fighting World War II, it administered many Pacific islands captured during the fight against Japan. Partly to prevent the militaries of those countries from growing threateningly large, and partly to contain the Soviet Union, the United States promised to defend Germany (which is also part of NATO) and Japan (through the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between the United States and Japan) which it had formerly defeated in war and which are now independent democracies. It maintains substantial military bases in both.

The Cold War reoriented American foreign policy towards opposing communism, and prevailing U.S. foreign policy embraced its role as a nuclear-armed global superpower. Though the Truman Doctrine and Reagan Doctrine the United States framed the mission as protecting free peoples against an undemocratic system, anti-Soviet foreign policy became coercive and occasionally covert. United States involvement in regime change included overthrowing the democratically elected government of Iran, the Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba, occupation of Grenada, and interference in various foreign elections. The long and bloody Vietnam War led to widespread criticism of an "arrogance of power" and violations of international law emerging from an "imperial presidency," with Martin Luther King, among others, accusing the US of a new form of colonialism.[9]

Many saw the post-Cold War 1990–91 Gulf War as motivated by U.S. oil interests, though it reversed the hostile invasion of Kuwait. After the September 11 attacks in 2001, questions of imperialism were raised again as the United States invaded Afghanistan (which harbored the attackers) and Iraq (which the U.S. incorrectly claimed had weapons of mass destruction). The invasion led to the collapse of the Ba'athist government and its replacement with the Coalition Provisional Authority. The Iraq War opened the country's oil industry to US firms for the first time in decades[10] and arguably violated international law. Both wars caused immense civilian casualties.[11]

In terms of territorial acquisition, the United States has integrated (with voting rights) all of its acquisitions on the North American continent, including the non-contiguous Alaska. Hawaii has also become a state with equal representation to the mainland, but other island jurisdictions acquired during wartime remain territories, namely Guam, Puerto Rico, the United States Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands. The remainder of acquired territories have become independent with varying degrees of cooperation, ranging from three freely associated states which participate in federal government programs in exchange for military basing rights, to Cuba which severed diplomatic relations during the Cold War. The United States was a public advocate for European decolonization after World War II (having started a ten-year independence transition for the Philippines in 1934 with the Tydings–McDuffie Act). Even so, the US desire for an informal system of global primacy in an "American Century" often brought them into conflict with national liberation movements.[12] The United States has now granted citizenship to Native Americans and recognizes some degree of tribal sovereignty.

1700s–1800s: Indian Wars and Manifest Destiny

Yale historian Paul Kennedy has asserted, "From the time the first settlers arrived in Virginia from England and started moving westward, this was an imperial nation, a conquering nation."[13] Expanding on George Washington's description of the early United States as an "infant empire",[14] Benjamin Franklin wrote: "Hence the Prince that acquires new Territory, if he finds it vacant, or removes the Natives to give his own People Room; the Legislator that makes effectual Laws for promoting of Trade, increasing Employment, improving Land by more or better Tillage; providing more Food by Fisheries; securing Property, etc. and the Man that invents new Trades, Arts or Manufactures, or new Improvements in Husbandry, may be properly called Fathers of their Nation, as they are the Cause of the Generation of Multitudes, by the Encouragement they afford to Marriage."[15] Thomas Jefferson asserted in 1786 that the United States "must be viewed as the nest from which all America, North & South is to be peopled. [...] The navigation of the Mississippi we must have. This is all we are as yet ready to receive.".[16] From the left Noam Chomsky writes that "the United States is the one country that exists, as far as I know, and ever has, that was founded as an empire explicitly".[17][18]

A national drive for territorial acquisition across the continent was popularized in the 19th century as the ideology of Manifest Destiny.[19] It came to be realized with the Mexican–American War of 1846, which resulted in the cession of 525,000 square miles of Mexican territory to the United States, stretching up to the Pacific coast.[7][8] The Whig Party strongly opposed this war and expansionism generally.[20]

President James Monroe presented his famous doctrine for the western hemisphere in 1823. Historians have observed that while the Monroe Doctrine contained a commitment to resist colonialism from Europe, it had some aggressive implications for American policy, since there were no limitations on the US's actions mentioned within it. Scholar Jay Sexton notes that the tactics used to implement the doctrine were "modeled after those employed by British imperialists" in their territorial competition with Spain and France.[21] From the left historian William Appleman Williams described it as "imperial anti-colonialism."[22]

The Indian Wars against the indigenous population began in the British era. Their escalation under the federal republic allowed the US to dominate North America and carve out the 48 contiguous states. This can be considered to be an explicitly colonial process in light of arguments that Native American nations were sovereign entities prior to annexation.[23] Their sovereignty was systematically undermined by US state policy (usually involving unequal or broken treaties) and white settler-colonialism.[24] The climax of this process was the California genocide.[25][26]

1800s: Filibustering in Central America

In the older historiography William Walker's filibustering represented the high tide of antebellum American imperialism. His brief seizure of Nicaragua in 1855 is typically called a representative expression of Manifest destiny with the added factor of trying to expand slavery into Central America. Walker failed in all his escapades and never had official U.S. backing. Historian Michel Gobat, however, presents a strongly revisionist interpretation. He argues that Walker was invited in by Nicaraguan liberals who were trying to force economic modernization and political liberalism. Walker's government comprised those liberals, as well as Yankee colonizers, and European radicals. Walker even included some local Catholics as well as indigenous peoples, Cuban revolutionaries, and local peasants. His coalition was much too complex and diverse to survive long, but it was not the attempted projection of American power, concludes Gobat.[27]

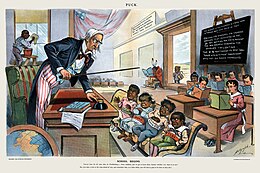

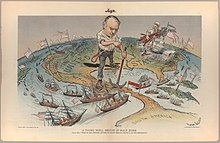

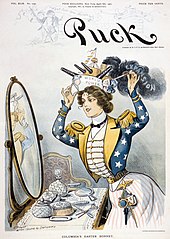

1800s–1900s: New Imperialism and "The White Man's Burden"

A variety of factors converged during the "New Imperialism" of the late 19th century, when the United States and the other great powers rapidly expanded their overseas territorial possessions. Some of these are used as examples of the various forms of New Imperialism.

- The prevalence of overt racism, notably John Fiske's conception of Anglo-Saxon racial superiority and Josiah Strong's call to "civilize and Christianize,"—were manifestations of a growing Social Darwinism and racism in some schools of American political thought.[29][30][31]

- Early in his career, as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt was instrumental in preparing the Navy for the Spanish–American War[32] and was an enthusiastic proponent of testing the U.S. military in battle, at one point stating "I should welcome almost any war, for I think this country needs one."[33][34][35]

Roosevelt claimed that he rejected imperialism, but he embraced the near-identical doctrine of expansionism.[citation needed] When Rudyard Kipling wrote the imperialist poem "The White Man's Burden" for Roosevelt, the politician told colleagues that it was "rather poor poetry, but good sense from the expansion point of view."[36] Roosevelt was so committed to dominating Spain's former colonies that he proclaimed his own corollary to the Monroe Doctrine as justification,[37] although his ambitions extended even further, into the Far East. Scholars have documented the resemblance and collaboration between US and British military activities in the Pacific at this time.[38]

Industry and trade are two of the most prevalent motivations of imperialism. American intervention in both Latin America and Hawaii resulted in multiple industrial investments, including the popular industry of Dole bananas. If the United States was able to annex a territory, in turn they were granted access to the trade and capital of those territories. In 1898, Senator Albert Beveridge proclaimed that an expansion of markets was absolutely necessary, "American factories are making more than the American people can use; American soil is producing more than they can consume. Fate has written our policy for us; the trade of the world must and shall be ours."[39][40]

American rule of ceded Spanish territory was not uncontested. The Philippine Revolution had begun in August 1896 against Spain, and after the defeat of Spain in the Battle of Manila Bay, began again in earnest, culminating in the Philippine Declaration of Independence and the establishment of the First Philippine Republic. The Philippine–American War ensued, with extensive damage and death, ultimately resulting in the defeat of the Philippine Republic.[41][42][43] According to scholars such as Gavan McCormack and E. San Juan, the American counterinsurgency resulted in genocide.[44][45]

The maximum geographical extension of American direct political and military control happened in the aftermath of World War II, in the period after the surrender and occupations of Germany and Austria in May and later Japan and Korea in September 1945 and before the independence of the Philippines in July 1946.[46]

Stuart Creighton Miller says that the public's sense of innocence about Realpolitik impairs popular recognition of U.S. imperial conduct.[47] The resistance to actively occupying foreign territory has led to policies of exerting influence via other means, including governing other countries via surrogates or puppet regimes, where domestically unpopular governments survive only through U.S. support.[48]

The Philippines is sometimes cited as an example. After Philippine independence, the US continued to direct the country through Central Intelligence Agency operatives like Edward Lansdale. As Raymond Bonner and other historians note, Lansdale controlled the career of President Ramon Magsaysay, going so far as to physically beat him when the Philippine leader attempted to reject a speech the CIA had written for him. American agents also drugged sitting President Elpidio Quirino and prepared to assassinate Senator Claro Recto.[49][50] Prominent Filipino historian Roland G. Simbulan has called the CIA "US imperialism's clandestine apparatus in the Philippines".[51]

The U.S. retained dozens of military bases, including a few major ones. In addition, Philippine independence was qualified by legislation passed by the U.S. Congress. For example, the Bell Trade Act provided a mechanism whereby U.S. import quotas might be established on Philippine articles which "are coming, or are likely to come, into substantial competition with like articles the product of the United States". It further required U.S. citizens and corporations be granted equal access to Philippine minerals, forests, and other natural resources.[52] In hearings before the Senate Committee on Finance, Assistant Secretary of State for Economic Affairs William L. Clayton described the law as "clearly inconsistent with the basic foreign economic policy of this country" and "clearly inconsistent with our promise to grant the Philippines genuine independence."[53]

1918: Wilsonian intervention

When World War I broke out in Europe, President Woodrow Wilson promised American neutrality throughout the war. This promise was broken when the United States entered the war after the Zimmermann Telegram. This was "a war for empire" to control vast raw materials in Africa and other colonized areas, according to the contemporary historian and civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois.[54] More recently historian Howard Zinn argues that Wilson entered the war in order to open international markets to surplus US production. He quotes Wilson's own declaration that

Concessions obtained by financiers must be safeguarded by ministers of state, even if the sovereignty of unwilling nations be outraged in the process... the doors of the nations which are closed must be battered down.

In a memo to Secretary of State Bryan, the president described his aim as "an open door to the world".[55] Lloyd Gardner notes that Wilson's original avoidance of world war was not motivated by anti-imperialism; his fear was that "white civilization and its domination in the world" were threatened by "the great white nations" destroying each other in endless battle.[56]

Despite President Wilson's official doctrine of moral diplomacy seeking to "make the world safe for democracy," some of his activities at the time can be viewed as imperialism to stop the advance of democracy in countries such as Haiti.[57] The United States invaded Haiti in July 1915 after having made landfall eight times previously. American rule in Haiti continued through 1942, but was initiated during World War I. The historian Mary Renda in her book, Taking Haiti, talks about the American invasion of Haiti to bring about political stability through U.S. control. The American government did not believe Haiti was ready for self-government or democracy, according to Renda. In order to bring about political stability in Haiti, the United States secured control and integrated the country into the international capitalist economy, while preventing Haiti from practicing self-governance or democracy. While Haiti had been running their own government for many years before American intervention, the U.S. government regarded Haiti as unfit for self-rule. In order to convince the American public of the justice in intervening, the United States government used paternalist propaganda, depicting the Haitian political process as uncivilized. The Haitian government would come to agree to U.S. terms, including American overseeing of the Haitian economy. This direct supervision of the Haitian economy would reinforce U.S. propaganda and further entrench the perception of Haitians' being incompetent of self-governance.[58]

In World War I, the US, Britain, and Russia had been allies for seven months, from April 1917 until the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in November. Active distrust surfaced immediately, as even before the October Revolution British officers had been involved in the Kornilov Affair, which sought to crush the Russian anti-war movement and the independent soviets.[59] Nonetheless, once the Bolsheviks took Moscow, the British began talks to try and keep them in the war effort. British diplomat Bruce Lockhart cultivated a relationship with several Soviet officials, including Leon Trotsky, and the latter approved the initial Allied military mission to secure the Eastern Front, which was collapsing in the revolutionary upheaval. Ultimately, Soviet head of state V.I. Lenin decided the Bolsheviks would settle peacefully with the Central Powers at the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. This separate peace led to Allied disdain for the Soviets, since it left the Western Allies to fight Germany without a strong Eastern partner. The British SIS, supported by US diplomat Dewitt C. Poole, sponsored an attempted coup in Moscow involving Bruce Lockhart and Sidney Reilly, which involved an attempted assassination of Lenin. The Bolsheviks proceeded to shut down the British and U.S. embassies.[60][61]

Tensions between Russia (including its allies) and the West turned intensely ideological. Horrified by mass executions of White forces, land expropriations, and widespread repression, the Allied military expedition now assisted the anti-Bolshevik Whites in the Russian Civil War, with the US covertly giving support[62] to the autocratic and antisemitic General Alexander Kolchak.[63] Over 30,000 Western troops were deployed in Russia overall.[64] This was the first event that made Russian–American relations a matter of major, long-term concern to the leaders in each country. Some historians, including William Appleman Williams and Ronald Powaski, trace the origins of the Cold War to this conflict.[65]

Wilson launched seven armed interventions, more than any other president.[66] Looking back on the Wilson era, General Smedley Butler, a leader of the Haiti expedition and the highest-decorated Marine of that time, considered virtually all of the operations to have been economically motivated.[67] In a 1933 speech he said:

I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. I suspected I was just part of a racket at the time. Now I am sure of it...I helped make Mexico, especially Tampico, safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefits of Wall Street ... Looking back on it, I feel that I could have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three districts. I operated on three continents.[68]

1941–1945: World War II

This section is missing information about information about American imperialism in the WW-II period. (January 2019) |

The Grand Area

In an October 1940 report to Franklin Roosevelt, Bowman wrote that “the US government is interested in any solution anywhere in the world that affects American trade. In a wide sense, commerce is the mother of all wars.” In 1942 this economic globalism was articulated as the “Grand Area” concept in secret documents. The US would have to have control over the “Western Hemisphere, Continental Europe and Mediterranean Basin (excluding Russia), the Pacific Area and the Far East, and the British Empire (excluding Canada).” The Grand Area encompassed all known major oil-bearing areas outside the Soviet Union, largely at the behest of corporate partners like the Foreign Oil Committee and the Petroleum Industry War Council.[69] The US thus avoided overt territorial acquisition, like that of the British and French empires, as being too costly, choosing the cheaper option of forcing countries to open their door to American capitalism.[70]

Although the United States was the last major belligerent to join World War II, it began planning for the post-war world from the conflict's outset. This postwar vision originated in the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), an economic elite-led organization that became integrated into the government leadership. CFR's War and Peace Studies group offered its services to the State Department in 1939 and a secret partnership for post-war planning developed. CFR leaders Hamilton Fish Armstrong and Walter H. Mallory saw World War II as a “grand opportunity” for the U.S. to emerge as "the premier power in the world."[71]

This vision of empire assumed the necessity of the U.S. to “police the world” in the aftermath of the war. This was not done primarily out of altruism, but out of economic interest. Isaiah Bowman, a key liaison between the CFR and the State Department, proposed an “American economic Lebensraum.” This built upon the ideas of Time-Life publisher Henry Luce, who (in his “American Century” essay) wrote, “Tyrannies may require a large amount of living space [but] freedom requires and will require far greater living space than Tyranny.” According to Bowman's biographer, Neil Smith:

Better than the American Century or the Pax Americana, the notion of an American Lebensraum captures the specific and global historical geography of U.S. ascension to power. After World War II, global power would no longer be measured in terms of colonized land or power over territory. Rather, global power was measured in directly economic terms. Trade and markets now figured as the economic nexuses of global power, a shift confirmed in the 1944 Bretton Woods agreement, which not only inaugurated an international currency system but also established two central banking institutions—the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank—to oversee the global economy. These represented the first planks of the economic infrastructure of the postwar American Lebensraum.[72]

1947–1952 Cold War in Western Europe: "Empire by invitation"

Prior to his death in 1945, President Roosevelt was planning to withdraw all U.S. forces from Europe as soon as possible. Soviet actions in Poland and Czechoslovakia led his successor Harry Truman to reconsider. Heavily influenced by George Kennan, Washington policymakers believed that the Soviet Union was an expansionary dictatorship that threatened American interests. In their theory, Moscow's weakness was that it had to keep expanding to survive; and that, by containing or stopping its growth, stability could be achieved in Europe. The result was the Truman Doctrine (1947) regarding Greece and Turkey. A second equally important consideration was the need to restore the world economy, which required the rebuilding and reorganizing of Europe for growth. This matter, more than the Soviet threat, was the main impetus behind the Marshall Plan of 1948. A third factor was the realization, especially by Britain and the three Benelux nations, that American military involvement was needed [clarification needed]. Geir Lundestad has commented on the importance of "the eagerness with which America's friendship was sought and its leadership welcomed.... In Western Europe, America built an empire 'by invitation'" [73] At the same time, the U.S. interfered in Italian and French politics in order to purge elected communist officials who might oppose such invitations.[74]

Post-1954: Korea, Vietnam and "imperial internationalism"

Outside of Europe, American imperialism was more distinctly hierarchical “with much fainter liberal characteristics.” Cold War policy often found itself opposed to full decolonization, especially in Asia. The United States decision to colonize some of the Pacific islands (which had formerly been held by the Japanese) in the 1940s ran directly counter to America's rhetoric against imperialism. The functioning of the Grand Area and the Open Door in Asia meant a new “imperial internationalism” wherein wars were fought to ensure a steady supply of raw materials from the global periphery to the core society in the United States and Western Europe. In this spirit, General Douglas MacArthur described the Pacific as an “Anglo-Saxon lake.” At the same time, the U.S. did not claim state control over much mainland territory but cultivated friendly members of the elites of decolonized countries—elites which were usually dictatorial, as in South Korea, Indonesia, and South Vietnam.

In South Korea, the U.S. quickly allied with Syngman Rhee, leader of the fight against the popularly established committees that proclaimed a provisional government. The mass call for an independent and unified Korean government was bloodily repressed by Rhee's forces, which were overseen by the U.S. Army. This pre-Korean War violence saw the deaths of 100,000 people, the majority of them civilians.[75] With National Security Council document 68 and the subsequent Korean War, the U.S. adopted a policy of “rollback” against communism in Asia. John Tirman, an American political theorist has asserted that this policy was heavily influenced by America's imperialistic policy in Asia in the 19th century, with its goals to Christianize and Americanize the peasant masses.[76]

In Vietnam, the U.S. again eschewed its anti-imperialist rhetoric by materially supporting the French Empire in a colonial counterinsurgency. Influenced by the Grand Area policy, the U.S. eventually assumed total responsibility for war against the Vietnamese communists, including suppressing nationwide elections when it appeared that Ho Chi Minh would win.[77] The ensuing battles led to large-scale antipersonnel operations in South Vietnam, North Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, leading Martin Luther King to call the American government “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.” [78]

American exceptionalism

American exceptionalism is the notion that the United States occupies a special niche among the nations of the world[79] in terms of its national credo, historical evolution, and political and religious institutions and origins.

Philosopher Douglas Kellner traces the identification of American exceptionalism as a distinct phenomenon back to 19th-century French observer Alexis de Tocqueville, who concluded by agreeing that the U.S., uniquely, was "proceeding along a path to which no limit can be perceived".[80]

President Donald Trump has said that he does not "like the term" American exceptionalism because he thinks it is "insulting the world." He told tea party activists in Texas, "If you're German, or you're from Japan, or you're from China, you don't want to have people saying that."[81]

As a Monthly Review editorial opines on the phenomenon, "In Britain, empire was justified as a benevolent 'white man's burden.' And in the United States, empire does not even exist; 'we' are merely protecting the causes of freedom, democracy and justice worldwide."[82]

Views of American imperialism

Journalist Ashley Smith divides theories of the U.S. imperialism into 5 broad categories: (1) "liberal" theories, (2) "social-democratic" theories, (3) "Leninist" theories, (4) theories of "super-imperialism", and (5) "Hardt-and-Negri" theories.[83][clarification needed]

There is also a conservative, anti-interventionist view as expressed by American journalist John T. Flynn:

The enemy aggressor is always pursuing a course of larceny, murder, rapine and barbarism. We are always moving forward with high mission, a destiny imposed by the Deity to regenerate our victims, while incidentally capturing their markets; to civilise savage and senile and paranoid peoples, while blundering accidentally into their oil wells.[84]

A "social-democratic" theory says that imperialistic U.S. policies are the products of the excessive influence of certain sectors of U.S. business and government—the arms industry in alliance with military and political bureaucracies and sometimes other industries such as oil and finance, a combination often referred to as the "military–industrial complex." The complex is said to benefit from war profiteering and looting natural resources, often at the expense of the public interest.[85] The proposed solution is typically unceasing popular vigilance in order to apply counter-pressure.[86] Chalmers Johnson holds a version of this view.[87]

Alfred Thayer Mahan, who served as an officer in the U.S. Navy during the late 19th century, supported the notion of American imperialism in his 1890 book titled The Influence of Sea Power upon History. Mahan argued that modern industrial nations must secure foreign markets for the purpose of exchanging goods and, consequently, they must maintain a maritime force that is capable of protecting these trade routes.[88][89]

A theory of "super-imperialism" argues that imperialistic U.S. policies are not driven solely by the interests of American businesses, but also by the interests of a larger apparatus of a global alliance among the economic elite in developed countries. The argument asserts that capitalism in the Global North (Europe, the U.S., Japan, and others) has become too entangled to permit military or geopolitical conflict between these countries, and the central conflict in modern imperialism is between the Global North (also referred to as the global core) and the Global South (also referred to as the global periphery), rather than between the imperialist powers.

Political debate after September 11, 2001

Following the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, the idea of American imperialism was re-examined. In November 2001, jubilant marines hoisted an American flag over Kandahar and in a stage display referred to the moment as the third after those on San Juan Hill and Iwo Jima. All moments, writes Neil Smith, express U.S. global ambition. "Labelled a war on terrorism, the new war represents an unprecedented quickening of the American Empire, a third chance at global power."[90]

On October 15, 2001, the cover of Bill Kristol's Weekly Standard carried the headline, "The Case for American Empire".[91] Rich Lowry, editor in chief of the National Review, called for "a kind of low-grade colonialism" to topple dangerous regimes beyond Afghanistan.[92] The columnist Charles Krauthammer declared that, given complete U.S. domination "culturally, economically, technologically and militarily", people were "now coming out of the closet on the word 'empire'".[13] The New York Times Sunday magazine cover for January 5, 2003, read "American Empire: Get Used To It". The phrase "American empire" appeared more than 1000 times in news stories during November 2002 – April 2003.[93]

Academic debates after September 11, 2001

In 2001-2010 numerous scholars debated the "America as Empire" issue.[94] Harvard historian Charles S. Maier states:

Since September 11, 2001 ... if not earlier, the idea of American empire is back ... Now ... for the first time since the early Twentieth century, it has become acceptable to ask whether the United States has become or is becoming an empire in some classic sense."[95]

Harvard professor Niall Ferguson states:

It used to be that only the critics of American foreign policy referred to the American empire ... In the past three or four years [2001–2004], however, a growing number of commentators have begun to use the term American empire less pejoratively, if still ambivalently, and in some cases with genuine enthusiasm.[96]

French Political scientist Philip Golub argues:

U.S. historians have generally considered the late 19th century imperialist urge as an aberration in an otherwise smooth democratic trajectory ... Yet a century later, as the U.S. empire engages in a new period of global expansion, Rome is once more a distant but essential mirror for American elites ... Now, with military mobilisation on an exceptional scale after September 2001, the United States is openly affirming and parading its imperial power. For the first time since the 1890s, the naked display of force is backed by explicitly imperialist discourse.[97]

A leading spokesman for America-as-Empire is British historian A. G. Hopkins.[98] He argues that by the 21st century traditional economic imperialism was no longer in play, noting that the oil companies opposed the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. Instead, anxieties about The negative impact of globalization on rural and rust-belt America were at work, says Hopkins:

- These anxieties prepared the way for a conservative revival based on family, faith and flag that enabled the neo-conservatives to transform conservative patriotism into assertive nationalism after 9/11. In the short term, the invasion of Iraq was a manifestation of national unity. Placed in a longer perspective, it reveals a growing divergence between new globalised interests, which rely on cross-border negotiation, and insular nationalist interests, which seek to rebuild fortress America.[99]

Conservative Harvard professor Niall Ferguson concludes that worldwide military and economic power have combined to make the U.S. the most powerful empire in history. It is a good idea he thinks, because like the successful British Empire in the 19th century it works to globalize free markets, enhanced the rule of law and promote representative government. He fears, however, that Americans lack the long-term commitment in manpower and money to keep the Empire operating.[101]

The U.S. dollar is the de facto world currency.[102] The term petrodollar warfare refers to the alleged motivation of U.S. foreign policy as preserving by force the status of the United States dollar as the world's dominant reserve currency and as the currency in which oil is priced. The term was coined by William R. Clark, who has written a book with the same title. The phrase oil currency war is sometimes used with the same meaning.[103]

Many – perhaps most—scholars have decided that the United States lacks the key essentials of an empire. For example, while there are American military bases all over, the American soldiers do not rule over the local people, and the United States government does not send out governors or permanent settlers like all the historic empires did.[104] Harvard historian Charles S. Maier has examined the America-as-Empire issue at length. He says the traditional understanding of the word "empire" does not apply, because the United States does not exert formal control over other nations or engage in systematic conquest. The best term is that the United States is a "hegemon." Its enormous influence through high technology, economic power, and impact on popular culture gives it an international outreach that stands in sharp contrast to the inward direction of historic empires.[105][106]

World historian Anthony Pagden asks, Is the United States really an empire?

- I think if we look at the history of the European empires, the answer must be no. It is often assumed that because America possesses the military capability to become an empire, any overseas interest it does have must necessarily be imperial....In a number of crucial respects, the United States is, indeed, very un-imperial.... America bears not the slightest resemblance to ancient Rome. Unlike all previous European empires, it has no significant overseas settler populations in any of its formal dependencies and no obvious desire to acquire any....It exercises no direct rule anywhere outside these areas, and it has always attempted to extricate itself as swiftly as possible from anything that looks as if it were about to develop into even indirect rule.[107]

In the book "Empire", Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri argue that "the decline of Empire has begun".[108] Hardt says the Iraq War is a classically imperialist war and is the last gasp of a doomed strategy.[109] They expand on this, claiming that in the new era of imperialism, the classical imperialists retain a colonizing power of sorts, but the strategy shifts from military occupation of economies based on physical goods to a networked biopower based on an informational and affective economies. They go on to say that the U.S. is central to the development of this new regime of international power and sovereignty, termed "Empire", but that it is decentralized and global, and not ruled by one sovereign state: "The United States does indeed occupy a privileged position in Empire, but this privilege derives not from its similarities to the old European imperialist powers, but from its differences."[110] Hardt and Negri draw on the theories of Spinoza, Foucault, Deleuze and Italian autonomist Marxists.[111][112]

Geographer David Harvey says there has emerged a new type of imperialism due to geographical distinctions as well as unequal rates of development.[113] He says there have emerged three new global economic and political blocs: the United States, the European Union, and Asia centered on China and Russia.[114][verification needed] He says there are tensions between the three major blocs over resources and economic power, citing the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the motive of which, he argues, was to prevent rival blocs from controlling oil.[115] Furthermore, Harvey argues that there can arise conflict within the major blocs between business interests and the politicians due to their sometimes incongruent economic interests.[116] Politicians live in geographically fixed locations and are, in the U.S. and Europe,[verification needed] accountable to an electorate. The 'new' imperialism, then, has led to an alignment of the interests of capitalists and politicians in order to prevent the rise and expansion of possible economic and political rivals from challenging America's dominance.[117]

Classics professor and war historian Victor Davis Hanson dismisses the notion of an American Empire altogether, with a mocking comparison to historical empires: "We do not send out proconsuls to reside over client states, which in turn impose taxes on coerced subjects to pay for the legions. Instead, American bases are predicated on contractual obligations — costly to us and profitable to their hosts. We do not see any profits in Korea, but instead accept the risk of losing almost 40,000 of our youth to ensure that Kias can flood our shores and that shaggy students can protest outside our embassy in Seoul."[118]

The existence of "proconsuls", however, has been recognized by many since the early Cold War. In 1957, French Historian Amaury de Riencourt associated the American "proconsul" with "the Roman of our time."[119] Expert on recent American history, Arthur M. Schlesinger, detected several contemporary imperial features, including "proconsuls." Washington does not directly run many parts of the world. Rather, its "informal empire" was one "richly equipped with imperial paraphernalia: troops, ships, planes, bases, proconsuls, local collaborators, all spread wide around the luckless planet."[120] "The Supreme Allied Commander, always an American, was an appropriate title for the American proconsul whose reputation and influence outweighed those of European premiers, presidents, and chancellors."[121] U.S. "combatant commanders ... have served as its proconsuls. Their standing in their regions has usually dwarfed that of ambassadors and assistant secretaries of state."[122]

Harvard Historian Niall Ferguson calls the regional combatant commanders, among whom the whole globe is divided, the "pro-consuls" of this "imperium."[123] Günter Bischof calls them "the all powerful proconsuls of the new American empire. Like the proconsuls of Rome they were supposed to bring order and law to the unruly and anarchical world."[124] In September 2000, Washington Post reporter Dana Priest published a series of articles whose central premise was Combatant Commanders' inordinate amount of political influence within the countries in their areas of responsibility. They "had evolved into the modern-day equivalent of the Roman Empire's proconsuls—well-funded, semi-autonomous, unconventional centers of U.S. foreign policy."[125] The Romans often preferred to exercise power through friendly client regimes, rather than direct rule: "Until Jay Garner and L. Paul Bremer became U.S. proconsuls in Baghdad, that was the American method, too".[126]

Another distinction of Victor Davis Hanson—that US bases, contrary to the legions, are costly to America and profitable for their hosts—expresses the American view. The hosts express a diametrically opposite view. Japan pays for 25,000 Japanese working on US bases. 20% of those workers provide entertainment: a list drawn up by the Japanese Ministry of Defense included 76 bartenders, 48 vending machine personnel, 47 golf course maintenance personnel, 25 club managers, 20 commercial artists, 9 leisure-boat operators, 6 theater directors, 5 cake decorators, 4 bowling alley clerks, 3 tour guides and 1 animal caretaker. Shu Watanabe of the Democratic Party of Japan asks: "Why does Japan need to pay the costs for US service members' entertainment on their holidays?"[127] One research on host nations support concludes:

At an alliance-level analysis, case studies of South Korea and Japan show that the necessity of the alliance relationship with the U.S. and their relative capabilities to achieve security purposes lead them to increase the size of direct economic investment to support the U.S. forces stationed in their territories, as well as to facilitate the US global defense posture. In addition, these two countries have increased their political and economic contribution to the U.S.-led military operations beyond the geographic scope of the alliance in the post-Cold War period ... Behavioral changes among the U.S. allies in response to demands for sharing alliance burdens directly indicate the changed nature of unipolar alliances. In order to maintain its power preponderance and primacy, the unipole has imposed greater pressure on its allies to devote much of their resources and energy to contributing to its global defense posture ... [It] is expected that the systemic properties of unipolarity–non-structural threat and a power preponderance of the unipole–gradually increase the political and economic burdens of the allies in need of maintaining alliance relationships with the unipole.[128]

In fact, increasing the "economic burdens of the allies" is one of the major priorities of President Donald Trump.[129][130][131][132] Classicist Eric Adler notes that Hanson earlier had written about the decline of the classical studies in the United States and insufficient attention devoted to the classical experience. "When writing about American foreign policy for a lay audience, however, Hanson himself chose to castigate Roman imperialism in order to portray the modern United States as different from—and superior to—the Roman state."[133] As a supporter of a hawkish unilateral American foreign policy, Hanson's "distinctly negative view of Roman imperialism is particularly noteworthy, since it demonstrates the importance a contemporary supporter of a hawkish American foreign policy places on criticizing Rome."[133]

U.S. foreign policy debate

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (January 2014) |

Annexation is a crucial instrument in the expansion of a nation, due to the fact that once a territory is annexed it must act within the confines of its superior counterpart. The United States Congress' ability to annex a foreign territory is explained in a report from the Congressional Committee on Foreign Relations, "If, in the judgment of Congress, such a measure is supported by a safe and wise policy, or is based upon a natural duty that we owe to the people of Hawaii, or is necessary for our national development and security, that is enough to justify annexation, with the consent of the recognized government of the country to be annexed."[134]

Prior to annexing a territory, the American government still held immense power through the various legislations passed in the late 1800s. The Platt Amendment was utilized to prevent Cuba from entering into any agreement with foreign nations and also granted the Americans the right to build naval stations on their soil.[135] Executive officials in the American government began to determine themselves the supreme authority in matters regarding the recognition or restriction of independence.[135]

When asked on April 28, 2003, on Al Jazeera whether the United States was "empire building," Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld replied, "We don't seek empires. We're not imperialistic. We never have been."[136]

However, historian Donald W. Meinig says imperial behavior by the United States dates at least to the Louisiana Purchase, which he describes as an "imperial acquisition—imperial in the sense of the aggressive encroachment of one people upon the territory of another, resulting in the subjugation of that people to alien rule." The U.S. policies towards the Native Americans, he said, were "designed to remold them into a people more appropriately conformed to imperial desires."[137]

Writers and academics of the early 20th century, like Charles A. Beard, in support of non-interventionism (sometimes referred to as "isolationism"), discussed American policy as being driven by self-interested expansionism going back as far as the writing of the Constitution. Some politicians today do not agree. Pat Buchanan claims that the modern United States' drive to empire is "far removed from what the Founding Fathers had intended the young Republic to become."[138]

Andrew Bacevich argues that the U.S. did not fundamentally change its foreign policy after the Cold War, and remains focused on an effort to expand its control across the world.[139] As the surviving superpower at the end of the Cold War, the U.S. could focus its assets in new directions, the future being "up for grabs," according to former Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Paul Wolfowitz in 1991.[140] Head of the Olin Institute for Strategic Studies at Harvard University, Stephen Peter Rosen, maintains:

A political unit that has overwhelming superiority in military power, and uses that power to influence the internal behavior of other states, is called an empire. Because the United States does not seek to control territory or govern the overseas citizens of the empire, we are an indirect empire, to be sure, but an empire nonetheless. If this is correct, our goal is not combating a rival, but maintaining our imperial position and maintaining imperial order.[141]

In Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, the political activist Noam Chomsky argues that exceptionalism and the denials of imperialism are the result of a systematic strategy of propaganda, to "manufacture opinion" as the process has long been described in other countries.[142]

Thorton wrote that "[...]imperialism is more often the name of the emotion that reacts to a series of events than a definition of the events themselves. Where colonization finds analysts and analogies, imperialism must contend with crusaders for and against."[143] Political theorist Michael Walzer argues that the term hegemony is better than empire to describe the U.S.'s role in the world.[144] Political scientist Robert Keohane agrees saying, a "balanced and nuanced analysis is not aided ... by the use of the word 'empire' to describe United States hegemony, since 'empire' obscures rather than illuminates the differences in form of rule between the United States and other Great Powers, such as Great Britain in the 19th century or the Soviet Union in the twentieth".[145]

Since 2001,[146] Emmanuel Todd assumes the U.S.A. cannot hold for long the status of mondial hegemonic power, due to limited resources. Instead, the U.S.A. is going to become just one of the major regional powers along with European Union, China, Russia, etc. Reviewing Todd's After the Empire, G. John Ikenberry found that it had been written in "a fit of French wishful thinking."[147] The thinking proved to be "wishful" indeed, as the book became a bestseller in France for most of 2003.[148]

Other political scientists, such as Daniel Nexon and Thomas Wright, argue that neither term exclusively describes foreign relations of the United States. The U.S. can be, and has been, simultaneously an empire and a hegemonic power. They claim that the general trend in U.S. foreign relations has been away from imperial modes of control.[149]

Cultural imperialism

Some critics of imperialism argue that military and cultural imperialism are interdependent. American Edward Said, one of the founders of post-colonial theory, said,

... so influential has been the discourse insisting on American specialness, altruism and opportunity, that imperialism in the United States as a word or ideology has turned up only rarely and recently in accounts of the United States culture, politics and history. But the connection between imperial politics and culture in North America, and in particular in the United States, is astonishingly direct.[150]

International relations scholar David Rothkopf disagrees and argues that cultural imperialism is the innocent result of globalization, which allows access to numerous U.S. and Western ideas and products that many non-U.S. and non-Western consumers across the world voluntarily choose to consume.[151] Matthew Fraser has a similar analysis but argues further that the global cultural influence of the U.S. is a good thing.[152]

Nationalism is the main process through which the government is able to shape public opinion. Propaganda in the media is strategically placed in order to promote a common attitude among the people. Louis A. Perez Jr. provides an example of propaganda used during the war of 1898, "We are coming, Cuba, coming; we are bound to set you free! We are coming from the mountains, from the plains and inland sea! We are coming with the wrath of God to make the Spaniards flee! We are coming, Cuba, coming; coming now!"[135]

In contrast, many other countries with American brands have incorporated themselves into their own local culture. An example of this would be the self-styled "Maccas," an Australian derivation of "McDonald's" with a tinge of Australian culture.[153]

U.S. military bases

Chalmers Johnson argued in 2004 that America's version of the colony is the military base.[154] Chip Pitts argued similarly in 2006 that enduring U.S. bases in Iraq suggested a vision of "Iraq as a colony."[155]

While territories such as Guam, the United States Virgin Islands, the Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, and Puerto Rico remain under U.S. control, the U.S. allowed many of its overseas territories or occupations to gain independence after World War II. Examples include the Philippines (1946), the Panama Canal Zone (1979), Palau (1981), the Federated States of Micronesia (1986), and the Marshall Islands (1986). Most of them still have U.S. bases within their territories. In the case of Okinawa, which came under U.S. administration after the Battle of Okinawa during the Second World War, this happened despite local popular opinion.[156] In 2003, a Department of Defense distribution found the United States had bases in over 36 countries worldwide,[157] including the Camp Bondsteel base in the disputed territory of Kosovo.[158] Since 1959, Cuba has regarded the U.S. presence in Guantánamo Bay as illegal.[159]

By 1970,[needs update] the United States had more than one million soldiers in 30 countries,[citation needed] was a member of four regional defense alliances and an active participant in a fifth, had mutual defense treaties with 42 nations, was a member of 53 international organizations, and was furnishing military or economic aid to nearly 100 nations across the face of the globe.[160] In 2015 the Department of Defense reported the number of bases that had any military or civilians stationed or employed was 587. This includes land only (where no facilities are present), facility or facilities only (where there the underlying land is neither owned nor controlled by the government), and land with facilities (where both are present).[161]

Also in 2015, David Vine's book Base Nation, found 800 U.S. military bases located outside of the U.S., including 174 bases in Germany, 113 in Japan, and 83 in South Korea. The total cost: an estimated $100 billion a year.[162]

According to The Huffington Post, "The 45 nations and territories with little or no democratic rule represent more than half of the roughly 80 countries now hosting U.S. bases. ... Research by political scientist Kent Calder confirms what's come to be known as the "dictatorship hypothesis": The United States tends to support dictators [and other undemocratic regimes] in nations where it enjoys basing facilities."[163]

Benevolent imperialism

One of the earliest historians of American Empire, William Appleman Williams, wrote, "The routine lust for land, markets or security became justifications for noble rhetoric about prosperity, liberty and security."[164]

Max Boot defends U.S. imperialism, writing, "U.S. imperialism has been the greatest force for good in the world during the past century. It has defeated communism and Nazism and has intervened against the Taliban and Serbian ethnic cleansing."[165] Boot used "imperialism" to describe United States policy, not only in the early 20th century but "since at least 1803."[165][166] This embrace of empire is made by other neoconservatives, including British historian Paul Johnson, and writers Dinesh D'Souza and Mark Steyn. It is also made by some liberal hawks, such as political scientists Zbigniew Brzezinski and Michael Ignatieff.[167]

British historian Niall Ferguson argues that the United States is an empire and believes that this is a good thing: "What is not allowed is to say that the United States is an empire and that this might not be wholly bad."[168] Ferguson has drawn parallels between the British Empire and the imperial role of the United States in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, though he describes the United States' political and social structures as more like those of the Roman Empire than of the British. Ferguson argues that all of these empires have had both positive and negative aspects, but that the positive aspects of the U.S. empire will, if it learns from history and its mistakes, greatly outweigh its negative aspects.[169]

Another point of view implies that United States expansion overseas has indeed been imperialistic, but that this imperialism is only a temporary phenomenon, a corruption of American ideals, or the relic of a past era. Historian Samuel Flagg Bemis argues that Spanish–American War expansionism was a short-lived imperialistic impulse and "a great aberration in American history," a very different form of territorial growth than that of earlier American history.[170] Historian Walter LaFeber sees the Spanish–American War expansionism not as an aberration, but as a culmination of United States expansion westward.[171]

Historian Victor Davis Hanson argues that the U.S. does not pursue world domination, but maintains worldwide influence by a system of mutually beneficial exchanges.[118] On the other hand, Filipino revolutionary General Emilio Aguinaldo felt as though American involvement in the Philippines was destructive: "The Filipinos fighting for Liberty, the American people fighting them to give them liberty. The two peoples are fighting on parallel lines for the same object."[172] American influence worldwide and the effects it has on other nations have multiple interpretations.

Liberal internationalists argue that even though the present world order is dominated by the United States, the form taken by that dominance is not imperial. International relations scholar John Ikenberry argues that international institutions have taken the place of empire.[147]

International relations scholar Joseph Nye argues that U.S. power is more and more based on "soft power," which comes from cultural hegemony rather than raw military or economic force. This includes such factors as the widespread desire to emigrate to the United States, the prestige and corresponding high proportion of foreign students at U.S. universities, and the spread of U.S. styles of popular music and cinema. Mass immigration into America may justify this theory, but it is hard to know whether the United States would still maintain its prestige without its military and economic superiority.,[173] In terms of soft power, Giles Scott-Smith, argues that American universities:[174]

- acted as magnets for attracting up-and-coming elites, who were keen to acquire the skills, qualifications and prestige that came with the ‘Made in the USA’ trademark. This is a subtle, long-term form of ‘soft power’ that has required only limited intervention by the US government to function successfully. It conforms to Samuel Huntington’s view that American power rarely sought to acquire foreign territories, preferring instead to penetrate them — culturally, economically and politically — in such a way as to secure acquiescence for US interests.[175][176]

See also

- Americanization

- American Century

- United States Space Force

- Criticism of the United States government

- Foreign interventions by the United States

- Inverted totalitarianism

- Globalization

- Manifest destiny

- Petrodollar warfare

- A People's History of American Empire – 2008 book by Howard Zinn, et al.

- Territories of the United States

- Washington Consensus

- New World Order (conspiracy theory)

- Neocolonialism

- New Imperialism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-imperialism

- Soviet Empire

- Chinese imperialism

- United States involvement in regime change

- United States involvement in regime change in Latin America

- United States territorial acquisitions

- List of armed conflicts involving the United States

- United States war crimes

Notes and references

- ^ "Base Structure Report : FY 2013 Baseline" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-21. Retrieved 2017-04-09.

- ^ "Protesters Accuse US of 'Imperialism' as Obama Rekindles Military Deal With Philippines". VICE News. 2014-04-28.

- ^ "Anti-US Base Candidate Wins Okinawa Governor Race". PopularResistance.Org.

- ^ Bonk, Mary (1999). Gale encyclopedia of US economic history. Gale Group. ISBN 978-0-7876-3888-7.

- ^ Bryne, Alex. "Yes, the US had an empire – and in the Virgin Islands, it still does". The Conversation. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- ^ Lindsay, Ivo H. Daalder and James M. (2001-11-30). "American Empire, Not 'If' but 'What Kind'".

- ^ a b Lens, Sidney; Zinn, Howard (2003) [1971]. The Forging of the American Empire. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 0-7453-2100-3.

- ^ a b Field, James A., Jr. (June 1978). "American Imperialism: The Worst Chapter i Almost Any Book". The American Historical Review. 83 (3): 644–668. doi:10.2307/1861842. JSTOR 1861842.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ University, © Stanford; Stanford; California 94305 (2017-04-25). "Beyond Vietnam". The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Why the war in Iraq was fought for Big Oil". CNN. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- ^ "US 'war on terror' has killed over half a million people: study". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- ^ "Decolonization and the Global Reach of the 'American Century' | US History II (American Yawp)". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ a b Emily Eakin "Ideas and Trends: All Roads Lead To DC" New York Times, March 31, 2002.

- ^ Contending with the American Empire : Introduction.

- ^ "Franklin's "Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind... "". www.columbia.edu.

- ^ "Envisaging the West: Thomas Jefferson and the Roots of Lewis and Clark". jeffersonswest.unl.edu.

- ^ "Modern-Day American Imperialism: Middle East and Beyond". chomsky.info.

- ^ Boston University (7 April 2010). "Noam Chomsky Lectures on Modern-Day American Imperialism: Middle East and Beyond". Retrieved 20 February 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Despite disagreements about Manifest Destiny’s validity at the time, O’Sullivan had stumbled on a broadly held national sentiment. Although it became a rallying cry as well as a rationale for the foreign policy that reached its culmination in 1845–46, the attitude behind Manifest Destiny had long been a part of the American experience.""Manifest Destiny | History, Examples, & Significance". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-09-17.

- ^ Spencer Tucker, ed. (2012). The Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 514. ISBN 9781851098538.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Preston, Andrew; Rossinow, Doug (2016-11-15). Outside In: The Transnational Circuitry of US History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190459871.

- ^ Sexton, Jay (2011-03-15). The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth-Century America. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 2–9. ISBN 9781429929288.

- ^ Wilkins, David E. (2010). American Indian Sovereignty and the U.S. Supreme Court: The Masking of Justice. University of Texas Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-292-77400-1.

- ^ Williams, Walter L. (1980). "United States Indian Policy and the Debate over Philippine Annexation: Implications for the Origins of American Imperialism". The Journal of American History. 66 (4): 810–831. doi:10.2307/1887638. JSTOR 1887638.

- ^ "American Genocide | Yale University Press". yalebooks.yale.edu. Retrieved 2018-01-26.

- ^ "California's state-sanctioned genocide of Native Americans". Newsweek. 2016-08-17. Retrieved 2018-01-26.

- ^ Michel Gobat, Empire by Invitation: William Walker and Manifest Destiny in Central America (Harvard UP, 2018). See this roundtable evaluation by scholars at H-Diplo.

- ^ "A Thing Well Begun Is Half Done". Persuasive Maps: PJ Mode Collection. Cornell University.

- ^ Thomas Friedman, "The Lexus and the Olive Tree", p. 381

- ^ Manfred Steger, "Globalism: The New Market Ideology"

- ^ Faux, Jeff (Fall 2005). "Flat Note from the Pied Piper of Globalization: Thomas L. Friedman's The World Is Flat". Dissent. pp. 64–67. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ Brands, Henry William. (1997). T.R.: The Last Romantic. New York: Basic Books. Reprinted 2001, full biography OCLC 36954615, ch 12

- ^ "April 16, 1897: T. Roosevelt Appointed Assistant Secretary of the Navy". Crucible of Empire—Timeline. PBS Online. Retrieved July 26, 2007.

- ^ "Transcript For "Crucible Of Empire"". Crucible of Empire—Timeline. PBS Online. Retrieved July 26, 2007.

- ^ Tilchin, William N. Theodore Roosevelt and the British Empire: A Study in Presidential Statecraft (1997)

- ^ ""The White Man's Burden": Kipling's Hymn to U.S. Imperialism". historymatters.gmu.edu. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- ^ "The roosevelt corollary - Imperialism". www.americanforeignrelations.com. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- ^ Kramer, Paul A. (2006-12-13). The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807877173.

- ^ Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States: 1492–2001. New York: HarperCollins, 2003. Print.

- ^ Jones, Gregg (2013). Honor in the Dust: Theodore Roosevelt, War in the Philippines, and the Rise and Fall of America's Imperial Dream. Penguin. pp. 169–170. ISBN 9780451239181.

- ^ Schirmer, Daniel B.; Shalom, Stephen Rosskamm (1987). The Philippines Reader: A History of Colonialism, Neocolonialism, Dictatorship, and Resistance. South End Press. pp. 18, 40–41. ISBN 978-0-89608-275-5.

- ^ Secretary Root's Record: "Marked Severities" in Philippine Warfare, Wikisource (multiple mentions)

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2014). A PEOPLE's HISTORY of the UNITED STATES 1492—PRESENT. Time Apt. Group. p. unnumbered. ISBN 978-615-5505-13-3.

- ^ San Juan, E. (November 28, 2005). "We Charge Genocide: A Brief History of US in the Philippines". Political Affairs. Retrieved 2020-01-22.

- ^ San Juan, E. (2007-09-03). U.S. Imperialism and Revolution in the Philippines. Springer. pp. Xii–xviii. doi:10.1057/9780230607033. ISBN 9780230607033.

- ^ "Philippine Republic Day". www.gov.ph.

- ^ Miller, Stuart Creighton (1982). Benevolent Assimilation: The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899-1903. Yale University Press. ISBN 030016193X.

- ^ Johnson, Chalmers, Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire (2000), pp. 72–79

- ^ Butterfield, Fox; Times, Special to the New York (1987-04-19). "New Book on Marcos Says U.S. Knew of His '72 Martial-Law Plans". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ^ Nashel, Jonathan (2005). Edward Lansdale's Cold War. Univ of Massachusetts Press. p. 32. ISBN 1558494642.

- ^ Simbulan, Roland G. (August 18, 2000). "Equipo Nizkor – Covert Operations and the CIA's Hidden History in the Philippines". www.derechos.org. Retrieved 2018-01-23. Lecture at the University of the Philippines-Manila, Rizal Hall, Padre Faura, Manila

- ^ "Commonwealth Act No. 733". Chan Robles Law Library. April 30, 1946.

- ^ Jenkins, Shirley (1954). American Economic Policy Toward the Philippines. Stanford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-8047-1139-9.

- ^ Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: HarperCollins, 2003. p. 363

- ^ Zinn, pp. 359–376

- ^ Zeiler, Thomas W.; Ekbladh, David K.; Garder, Lloyd C. (2017-03-27). Beyond 1917: The United States and the Global Legacies of the Great War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190604035.

- ^ Steigerwald, David (1994). Wilsonian Idealism in America. Cornell University Press. pp. 30–42. ISBN 0801429366.

- ^ Renda, "Introduction," in Taking Haiti: Military Occupation & the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915–1940, pp. 10–22, 29–34

- ^ Neilson, Keith (April 24, 2014). Strategy and Supply (RLE The First World War): The Anglo-Russian Alliance 1914-1917. Routledge. ISBN 9781317703457 – via Google Books.

- ^ Richelson, Jeffery T. (July 17, 1997). A Century of Spies: Intelligence in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199880584 – via Google Books.

- ^ Martin Sixsmith, "Fanny Kaplan's Attempt to Kill Lenin" in Was Revolution Inevitable?: Turning Points of the Russian Revolution, edited by Tony Brenton (Oxford University Press, 2017 ), pp. 185–192

- ^ Trickey, Erick. "The Forgotten Story of the American Troops Who Got Caught Up in the Russian Civil War". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- ^ Wood, Alan (2011-05-15). Russia's Frozen Frontier: A History of Siberia and the Russian Far East 1581 - 1991. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 187. ISBN 9781849664387.

- ^ "The National Archives | Exhibitions & Learning online | First World War | Spotlights on history". www.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

- ^ Powaski, "The United States and the Bolshevik Revolution, 1917–1933", in The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917–1991, pp. 5–34

- ^ Wertheim, Stephen (2011). "The Wilsonian Chimera: Why Debating Wilson's Vision Can't Save American Foreign Relations" (PDF). White House Studies. 10 (4): 343–359. ISSN 1535-4768.

- ^ Dubois, Laurent (2012-01-03). Haiti: The Aftershocks of History. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 240–249. ISBN 9780805095623.

- ^ "Excerpt from a speech delivered in 1933, by Major General Smedley Butler, USMC". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 1998-05-24.

- ^ George A. Gonzalez, Urban Sprawl, Global Warming, and the Empire of Capital (SUNY Press, 2009), p. 69-110

- ^ Paul, Erik (October 23, 2012). Neoliberal Australia and US Imperialism in East Asia. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137272775 – via Google Books.

- ^ Smith, Neil (October 29, 2004). American Empire: Roosevelt's Geographer and the Prelude to Globalization. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520243385 – via Internet Archive.

grand opportunity.

- ^ Smith, Neil (October 29, 2004). American Empire: Roosevelt's Geographer and the Prelude to Globalization. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520243385 – via Internet Archive.

lebensraum.

- ^ John Darwin (2010). After Tamerlane: The Rise and Fall of Global Empires, 1400-2000. p. 470. ISBN 9781596917606.

- ^ "If this American expansion created what we could call an American empire, this was to a large extent an empire by invitation...In semi-occupied Italy the State Department and Ambassador James Dunn in particular actively encouraged the non-communists to break with the communists and undoubtedly contributed to the latter being thrown out of the government in May 1947. In more normal France the American role was more restrained when the Ramadier government threw out its communists at about the same time. After the communists were out, Washington worked actively, through overt as well as covert activities, to isolate them as well as leftist socialists...US economic assistance was normally given with several strings attached." Lundestad, Geir (1986). "Empire by Invitation? The United States and Western Europe, 1945-1952". Journal of Peace Research. 23 (3): 263–277. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.689.5556. doi:10.1177/002234338602300305. JSTOR 423824.

- ^ Inderjeet Parmar, "The U.S.-led Liberal Order: Imperialism By Another Name?", International Affairs 5 January 2018, Volume 94, Number 1

- ^ John Tirman, Deaths of Others: The Fate of Civilians in America's Wars (Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 78-82

- ^ Domhoff, G. William (2014). "The Council on Foreign Relations and the Grand Area: Case Studies on the Origins of the IMF and the Vietnam War". Class, Race and Corporate Power. 2 (1). doi:10.25148/CRCP.2.1.16092111. Archived from the original on 2019-06-14. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- ^ Chris J. Magoc, Imperialism and Expansionism in American History (ABC-CLIO, 2015), p. 1233, 1278-81

- ^ Frederick Jackson Turner, Significance of the Frontier at the Wayback Machine (archived May 21, 2008), sagehistory.net (archived from the original on May 21, 2008).

- ^ Kellner, Douglas (April 25, 2003). "American Exceptionalism". Archived from the original on February 17, 2006. Retrieved February 20, 2006.

- ^ McManus, Doyle (8 February 2017). "The Trumpist Future: A World Without Exceptional America". LA Times. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Magdoff, Harry; John Bellamy Foster (November 2001). "After the Attack ... The War on Terrorism". Monthly Review. 53 (6): 7. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Smith, Ashley (June 24, 2006). The Classical Marxist Theory of Imperialism. Socialism 2006. Columbia University.

- ^ "Books" (PDF). Mises Institute. 2014-08-18.

- ^ C. Wright Mills, The Causes of World War Three, Simon and Schuster, 1958, pp. 52, 111

- ^ Flynn, John T. (1944) As We Go Marching.

- ^ Johnson, Chalmers (2004). The sorrows of empire: Militarism, secrecy, and the end of the republic. New York: Metropolitan Books.

- ^

Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1890). . Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company. . OCLC 2553178..

Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1890). . Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company. . OCLC 2553178..

- ^ Sumida, Jon Tetsuro (2006). "Geography, technology, and British naval strategy in the dreadnought era" (PDF). Naval War College Review. 59 (3): 89–102. JSTOR 26396746.

- ^ Neil Smith, American Empire: Roosevelt's Geographer and the Prelude to Globalization, (Berkeley & Los Angeles & London: University of California Press, 2003), p XI-XII.

- ^ Max Boot, "The Case for American Empire," Weekly Standard 7/5, (October 15, 2001)

- ^ Nina J. Easton, "Thunder on the Right," American Journalism Review 23 (December 2001), 320.

- ^ Lake, David A. (2007). "Escape from the State of Nature: Authority and Hierarchy in World Politics". International Security. 32: 47–79. doi:10.1162/isec.2007.32.1.47. S2CID 57572519.

- ^ Hopkins, A. G. (2007). "Comparing British and American empires". Journal of Global History. 2 (3): 395–404. doi:10.1017/S1740022807002343.

- ^ Charles S. Maier, Among Empires: American Ascendancy and Its Predecessors, (Massachusetts & London: Harvard University Press, 2006), p 2-24.

- ^ Niall Ferguson, Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire, (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), pp. 3–4.

- ^ Philip S. Golub, "Westward the Course of Empire", Le Monde Diplomatique, (September 2002)

- ^ A. G. Hopkins, American Empire: a Global History (2019).

- ^ Hopkins, A. G. (2007). "Capitalism, Nationalism and the New American Empire". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 35 (1): 95–117. doi:10.1080/03086530601143412. S2CID 143521756. Quoting page 95.

- ^ "CIA Secret Detention and Torture". opensocietyfoundations.org. Archived from the original on February 20, 2013.

- ^ Niall Ferguson, Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire (2004), excerpt

- ^ Schulmeister, Stephan (March 2000). "Globalization without Global Money: The Double Role of the Dollar as National Currency and World Currency". Journal of Post Keynesian Economics. 22 (3): 365–395. doi:10.1080/01603477.2000.11490246. ISSN 0160-3477. S2CID 59022899.

- ^ Clark, William R. Petrodollar Warfare: Oil, Iraq and the Future of the Dollar, New Society Publishers, 2005, Canada, ISBN 0-86571-514-9

- ^ Nugent, Habits of Empire p 287.

- ^ Charles S. Maier, Among Empires: American Ascendancy and Its Predecessors (2006).

- ^ Vuoto, Grace (2007). "The Anglo-American Global Imperial Legacy: Is There a Better Way?". Canadian Journal of History. 42 (2): 259–270. doi:10.3138/cjh.42.2.259.

- ^ Pagden, Anthony (2005). "Imperialism, liberalism & the quest for perpetual peace". Daedalus. 134 (2): 46–57. doi:10.1162/0011526053887301. S2CID 57564158. Quoting pp 52-53.

- ^ "Empire hits back". The Observer, July 15, 2001.

- ^ Hardt, Michael (July 13, 2006). "From Imperialism to Empire". The Nation.

- ^ Negri, Antonio; Hardt, Michael (2000). Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00671-2. Retrieved October 8, 2009. p. xiii–xiv.

- ^ Michael Hardt, Gilles Deleuze: an Apprenticeship in Philosophy, ISBN 0-8166-2161-6

- ^ Autonomism#Italian autonomism

- ^ Harvey, David (2005). The new imperialism. Oxford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-19-927808-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Harvey 2005, p. 31.

- ^ Harvey 2005, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 187.

- ^ Harvey 2005, pp. 76–78

- ^ a b Hanson, Victor Davis (November 2002). "A Funny Sort of Empire". National Review. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Cited in Geir Lundestad, The United States and Western Europe since 1945: From 'Empire' by Invitation to Transatlantic Drift, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p 112.

- ^ Schlesinger, Arthur Meier. The Cycles of American History, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986), p 141. OCLC 13455179

- ^ Lawrence Kaplan, "Western Europe in 'The American Century'", Diplomatic History, 6/2, (1982): p 115.

- ^ Cohen, Eliot A. (2004). "History and the Hyperpower". Foreign Affairs. 83 (4): 49–63. doi:10.2307/20034046. JSTOR 20034046. pp. 60-61

- ^ Niall Ferguson, Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire, (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), p 17.

- ^ Günter Bischof, "Empire Discourses: The 'American Empire' in Decline?" Kurswechsel, 2, (2009): p 18

- ^ Cited in Andrew Feickert, "The Unified Command Plan and Combatant Commands: Background and Issues for Congress", (Congressional Research Service, Washington: White House, 2013), p 59

- ^ Freedland, Jonathan (June 14, 2007). "Bush's Amazing Achievement". The New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504. Archived from the original on 2015-12-10.