Madison Square Garden

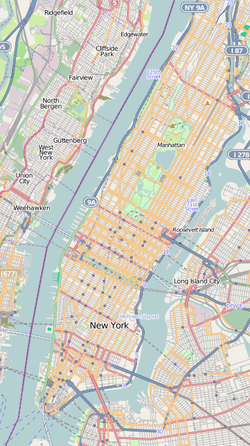

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as the Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd streets above Pennsylvania Station. It is the fourth venue to bear the name "Madison Square Garden"; the first two, opened in 1879 and 1890 respectively, were located on Madison Square, on East 26th Street and Madison Avenue, with the third Madison Square Garden (1925) farther uptown at Eighth Avenue and 50th Street.

The Garden hosts professional ice hockey, professional basketball, boxing, mixed martial arts, concerts, ice shows, circuses, professional wrestling, and other forms of sports and entertainment. It is close to other midtown Manhattan landmarks, including the Empire State Building, Koreatown, and Macy's at Herald Square. It is home to the New York Rangers of the National Hockey League (NHL), the New York Knicks of the National Basketball Association (NBA), and was home to the New York Liberty of the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA) from 1997 to 2017.

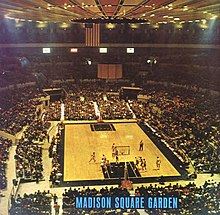

Originally called Madison Square Garden Center, the Garden opened on February 11, 1968, and is the oldest major sporting facility in the New York metropolitan area. It is the oldest arena in the NBA and the second-oldest in the NHL, after Seattle's Climate Pledge Arena. As of 2016, MSG is also the second-busiest music arena in the world in terms of ticket sales.[8] Including its two major renovations in 1991 and 2013, the Garden's total construction cost was approximately $1.1 billion, and it has been ranked as one of the 10 most expensive arena venues ever built.[9] It is part of the Pennsylvania Plaza office and retail complex, named for the railway station. Several other operating entities related to the Garden share its name.

History

[edit]Previous Gardens

[edit]Madison Square is formed by the intersection of 5th Avenue and Broadway at 23rd Street in Manhattan. It was named after James Madison, fourth President of the United States.[10]

Two venues called Madison Square Garden were located just northeast of the square, the original Garden from 1879 to 1890, and the second Garden from 1890 to 1925. The first, leased to P. T. Barnum,[11] was demolished in 1890 because of a leaky roof and dangerous balconies that had collapsed, resulting in deaths. The second was designed by noted architect Stanford White. The new building was built by a syndicate that included J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, P. T. Barnum,[12] Darius Mills, James Stillman and W. W. Astor. White gave them a Beaux-Arts structure with a Moorish feel, including a minaret-like tower modeled after Giralda, the bell tower of the Cathedral of Seville,[12] soaring 32 stories, the city's second-tallest building at the time[citation needed] and dominating Madison Square Park. It was 200 feet (61 m) by 485 feet (148 m), and the main hall, which was the largest in the world, measured 200 feet (61 m) by 350 feet (110 m) with permanent seating for 8,000 people and floor space for thousands more. It had a 1,200-seat theater, a concert hall with a capacity of 1,500, the largest restaurant in the city, and a roof garden cabaret.[11] The building cost $3 million.[11] Madison Square Garden II was unsuccessful like the first Garden,[13] and the New York Life Insurance Company, which held the mortgage on it, decided to tear it down in 1925 to make way for a new headquarters building, which would become the landmark Cass Gilbert-designed New York Life Building.

A third Madison Square Garden opened in a new location, on Eighth Avenue between 49th and 50th streets, from 1925 to 1968. Groundbreaking on the third Madison Square Garden took place on January 9, 1925.[14] Designed by the noted theater architect Thomas W. Lamb, it was built at the cost of $4.75 million in 249 days by boxing promoter Tex Rickard;[11] the arena was dubbed "The House That Tex Built".[15] The arena was 200 feet (61 m) by 375 feet (114 m), with seating on three levels, and a maximum capacity of 18,496 spectators for boxing.[11]

Demolition commenced in 1968 after the opening of the current Garden,[16] and was completed in early 1969. The site is now the location of One Worldwide Plaza.

Current Garden

[edit]In February 1959, former automobile manufacturer Graham-Paige purchased a 40% interest in the Madison Square Garden for $4 million[17] and later gained control.[18] In November 1960, Graham-Paige president Irving Mitchell Felt purchased from the Pennsylvania Railroad the rights to build at Penn Station.[19] To build the new facility, the above-ground portions of the original Pennsylvania Station were torn down.[20]

The new structure was one of the first of its kind to be built above the platforms of an active railroad station. It was an engineering feat constructed by Robert E. McKee of El Paso, Texas. Public outcry over the demolition of the Pennsylvania Station structure—an outstanding example of Beaux-Arts architecture—led to the creation of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. The venue opened on February 11, 1968. Comparing the new and the old Penn Station, Yale architectural historian Vincent Scully wrote, "One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat."[21]

In 1972, Felt proposed moving the Knicks and Rangers to a then incomplete venue in the New Jersey Meadowlands, the Meadowlands Sports Complex. The Garden was also the home arena for the NY Raiders/NY Golden Blades of the World Hockey Association. The Meadowlands would eventually host its own NBA and NHL teams, the New Jersey Nets and the New Jersey Devils, respectively. The New York Giants and Jets of the National Football League (NFL) also relocated there. In 1977, the arena was sold to Gulf and Western Industries. Felt's efforts fueled controversy between the Garden and New York City over real estate taxes. The disagreement again flared in 1980 when the Garden again challenged its tax bill. The arena has enjoyed tax-free status since the 1980s, under the condition that all Knicks and Rangers home games must be hosted at MSG, lest it lose this exemption. As such, when the Rangers have played neutral-site games—even those in New York City, such as the 2018 NHL Winter Classic, they have always been designated as the visiting team.[22] The tax agreement includes an act of God clause, which allowed Knicks and Rangers home games to be played elsewhere during the 2020 NBA Bubble and 2020 Stanley Cup playoffs, respectively, because of the COVID-19 pandemic.[23]

In 1984, the four streets immediately surrounding the Garden were designated as Joe Louis Plaza, in honor of boxer Joe Louis, who had made eight successful title defenses in the previous Madison Square Garden.[24][25]

1991 renovation

[edit]In April 1986, Gulf and Western announced that they would build a new Madison Square Garden a few blocks away on the site of present-day Hudson Yards. The plan would cost an estimated $150 million and included the demolition of the 1964 building to replace it with a new office tower development.[26] After years of planning, Gulf and Western decided against building a new arena in favor of a renovation after estimated costs doubled during the process.[27][28]

Garden owners spent $200 million in 1991 to renovate facilities and add 89 suites in place of hundreds of upper-tier seats. The project was designed by Ellerbe Becket. The renovation was criticized for perceived corporatization. Additionally, the renovation made bathrooms larger, expanded menus, added a new ventilation system, replaced all of the seats with new cushioned teal and violet seats, and refurbished both home teams' locker rooms.[29]

In 2000, current MSG owner James Dolan was quoted as saying that a new arena was being considered as the current building was starting to show its age.[30]

In 2004–2005, Cablevision battled with the City of New York over the proposed West Side arena, which was canceled. Cablevision then announced plans to raze the Garden, replace it with high-rise commercial buildings, and build a new Garden one block away at the site of the James Farley Post Office. Meanwhile, a new project to renovate and modernize the Garden completed phase one in time for the Rangers and Knicks' 2011–12 seasons,[31] though the vice president of the Garden says he remains committed to the installation of an extension of Penn Station at the Farley Post Office site. While the Knicks and Rangers were not displaced, the New York Liberty played at the Prudential Center in Newark, New Jersey during the renovation.

Madison Square Garden is the last of the NBA and NHL arenas not to be named after a corporate sponsor.[32]

2011–2013 renovation

[edit]Madison Square Garden's $1 billion second renovation took place mainly over three off-seasons. It was set to begin after the 2009–10 hockey/basketball seasons, but was delayed until after the 2010–11 seasons. Renovation was done in phases, with the majority of the work done in the summer months to minimize disruptions to the NHL and NBA seasons. While the Rangers and Knicks were not displaced,[33][34] the Liberty played their home games through the 2013 season at Prudential Center in Newark, New Jersey, during the renovation.[35][36]

New features include a larger entrance with interactive kiosks, retail, climate-controlled space, and broadcast studio; larger concourses; new lighting and LED video systems with HDTV; new seating; two new pedestrian walkways suspended from the ceiling to allow fans to look directly down onto the games being played below; more dining options; and improved dressing rooms, locker rooms, green rooms, upgraded roof, and production offices. The lower bowl concourse, called the Madison Concourse, remains on the sixth floor. The upper bowl concourse was relocated to the eighth floor and it is known as the Garden Concourse. The seventh floor houses the new Madison Suites and the Madison Club. The upper bowl was built on top of these suites. The rebuilt concourses are wider than their predecessors, and include large windows that offer views of the city streets around the Garden.[37]

Construction of the lower bowl (Phase 1) was completed in 2011.[38] An extended off-season for the Garden permitted some advance work to begin on the new upper bowl, which was completed in 2012. This advance work included the West Balcony on the tenth floor, taking the place of sky-boxes, and new end-ice 300 level seating. The construction of the upper bowl along with the Madison Suites and the Madison Club (Phase 2) were completed for the 2012–13 NHL and NBA seasons.[39][40] Phase 3, which involved the construction of the new lobby known as Chase Square, the Chase Bridges on the 10th floor, and the new scoreboard, was completed for the 2013–14 NHL and NBA seasons.[41][42]

Penn Station renovation controversy

[edit]Madison Square Garden is seen as an obstacle in the renovation and future expansion of Penn Station,[43] which expanded in 2021 with the opening of Moynihan Train Hall at the James Farley Post Office,[44] and some have proposed moving MSG to other sites in western Manhattan. On February 15, 2013, Manhattan Community Board 5 voted 36–0 against granting a renewal to MSG's operating permit in perpetuity and proposed a 10-year limit instead in order to build a new Penn Station where the arena is currently standing. Manhattan borough president Scott Stringer said, "Moving the arena is an important first step to improving Penn Station." The Madison Square Garden Company responded by saying that "[i]t is incongruous to think that M.S.G. would be considering moving."[45]

In May 2013, four architecture firms – SHoP Architects, SOM, H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture, and Diller Scofidio + Renfro – submitted proposals for a new Penn Station. SHoP Architects recommended moving Madison Square Garden to the Morgan Postal Facility a few blocks southwest, as well as removing 2 Penn Plaza and redeveloping other towers, and an extension of the High Line to Penn Station.[43] Meanwhile, SOM proposed moving Madison Square Garden to the area just south of the James Farley Post Office, and redeveloping the area above Penn Station as a mixed-use development with commercial, residential, and recreational space.[43] H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture wanted to move the arena to a new pier west of Jacob K. Javits Convention Center, four blocks west of the current station and arena. Then, according to H3's plan, four skyscrapers would be built, one at each of the four corners of the new Penn Station superblock, with a roof garden on top of the station; the Farley Post Office would become an education center.[43] Finally, Diller Scofidio + Renfro proposed a mixed-use development on the site, with spas, theaters, a cascading park, a pool, and restaurants; Madison Square Garden would be moved two blocks west, next to the post office. DS+F also proposed high-tech features in the station, such as train arrival and departure boards on the floor, and apps that would inform waiting passengers of ways to occupy their time until they board their trains.[43] Madison Square Garden rejected the notion that it would be relocated, and called the plans "pie-in-the-sky".[43]

In June 2013, the New York City Council Committee on Land Use voted unanimously to give the Garden a ten-year permit, at the end of which period the owners would either have to relocate or go back through the permission process.[46] On July 24, the City Council voted to give the Garden a 10-year operating permit by a vote of 47–1. "This is the first step in finding a new home for Madison Square Garden and building a new Penn Station that is as great as New York and suitable for the 21st century," said City Council speaker Christine Quinn. "This is an opportunity to reimagine and redevelop Penn Station as a world-class transportation destination."[47]

In October 2014, the Morgan facility was selected as the ideal area for Madison Square Garden to be moved, following the 2014 MAS Summit in New York City. More plans for the station were discussed.[48][49] Then, in January 2016, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a redevelopment plan for Penn Station that would involve the removal of The Theater at Madison Square Garden, but would otherwise leave the arena intact.[50][51]

In June 2023, nearing the end of the Garden's ten-year permit granted by the city, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, along with Amtrak and NJ Transit, filed a report stating that MSG is no longer compatible with Penn Station, with the report saying, "MSG's existing configuration and property boundaries impose severe constraints on the station that impede the safe and efficient movement of passengers and restrict efforts to implement improvements, particularly at the street and platform levels."[52] On September 14, 2023, the New York City Council voted 48–0 to renew the operating permit for Madison Square Garden for five years, the shortest ever granted by the city to the Garden.[53]

Events

[edit]Regular events

[edit]Sports

[edit]Madison Square Garden hosts approximately 320 events a year. It is the home to the New York Rangers of the National Hockey League, and the New York Knicks of the National Basketball Association. Before 2020, the New York Rangers, New York Knicks, and the Madison Square Garden arena itself were all owned by the Madison Square Garden Company. The MSG Company split into two entities in 2020, with the Garden arena and other non-sports assets spun off into Madison Square Garden Entertainment and the Rangers and Knicks remaining with the original company, renamed Madison Square Garden Sports. Both entities remain under the voting control of James Dolan and his family. The arena is also host to the Big East men's basketball tournament and was home to the finals of the National Invitation Tournament from the beginning of its existence up until 2022.[54] It also hosts select home games for the St. John's Red Storm, representing St. John's University in men's college basketball, and almost any other kind of indoor activity that draws large audiences, such as the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show and the 2004 Republican National Convention.

The Garden was home of the NBA draft and NIT Season Tip-Off,[55] as well as the former New York City home of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus and Disney on Ice; all four events are now held at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. It served the New York Cosmos for half of their home games during the 1983–84 NASL Indoor season.[56]

Many of boxing's biggest fights were held at Madison Square Garden, including the Roberto Durán–Ken Buchanan affair, the first Muhammad Ali – Joe Frazier bout and the US debut of Anthony Joshua that ended in a huge upset when he was beaten by Andy Ruiz. Before promoters such as Don King and Bob Arum moved boxing to Las Vegas, Nevada, Madison Square Garden was a popular location for boxing. The original 18+1⁄2 ft × 18+1⁄2 ft (5.6 m × 5.6 m) ring, which was brought from the second and third generation of the Garden, was officially retired on September 19, 2007, and donated to the International Boxing Hall of Fame after 82 years of service.[57] A 20 ft × 20 ft (6.1 m × 6.1 m) ring replaced it beginning on October 6 of that same year.[58] The UFC has hosted many events at Madison Square Garden in recent years and has put on some of the highest grossing PPV events in history.

Pro wrestling

[edit]Madison Square Garden has hosted many notable WWE (formerly WWF and WWWF) events.[59] The Garden has hosted three WrestleMania events, including the first edition of the annual marquee event for WWE, as well as the 10th and 20th editions. Madison Square Garden is also one of two venues (the other being Allstate Arena) to host WrestleMania three times.

It also hosted the Royal Rumble in 2000 and 2008; SummerSlam in 1988, 1991 and 1998; as well as Survivor Series in 1996, 2002 and 2011. Multiple episodes of WWE's weekly shows, Raw and SmackDown have been broadcast from the Arena as well.

New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW) and Ring of Honor (ROH) hosted their G1 Supercard supershow at the venue on April 6, 2019. A year later it was announced that New Japan Pro-Wrestling would return to Madison Square Garden alone on August 22, 2020, for NJPW Wrestle Dynasty.[60] In May 2020, NJPW announced that the Wrestle Dynasty show would be postponed to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[61][62]

Concerts

[edit]

Madison Square Garden hosts more high-profile concert events than any other venue in New York City. It has been the venue for Michael Jackson's Bad World Tour in 1988, George Harrison's The Concert for Bangladesh, The Concert for New York City following the September 11 attacks, John Lennon's final concert appearance during an Elton John concert on Thanksgiving Night in 1974 before his murder in 1980, and Elvis Presley, who gave four sold-out performances in 1972, his first and last ever in New York City. Parliament-Funkadelic headlined numerous sold-out shows in 1977 and 1978. Kiss, who were formed in the arena's city and three of whose members were city-born, did six shows during their second half of the 1970s main attraction peak or "heyday": four sold out winter shows at the arena in 1977 (February 18 and December 14–16), and another two shows only this time in summer for a decade-ender in 1979 (July 24–25). They played their final two shows at the venue on the December 1 and 2, 2023, the 50th anniversary year of their formation. Billy Joel, another city-born and fellow 1970's pop star, played his first Garden show on December 14, 1978, with that month's follow ups on the 15th, 16th and 18th. Led Zeppelin's three-night stand in July 1973 was recorded and released as both a film and album titled The Song Remains The Same. The Police played their final show of their reunion tour at the Garden in 2008.

In the summer of 2017, Phish held a 13 night series of concerts called "The Bakers' Dozen". During which the band played 237 unique songs, repeating none during the entire run. The Garden commemorated "The Bakers' Dozen" by adding a Phish themed banner to the rafters.[63] With their first MSG show taking place on December 30, 1994, Phish has regularly played annual multi night runs, typically around New Year's Eve.[64] As of January 2024, Phish has performed 83 times at MSG.[65][66]

Elton John once held the all-time record for the greatest number of appearances at the Garden with 64 shows. In a 2009 press release, John was quoted as saying "Madison Square Garden is my favorite venue in the whole world. I chose to have my 60th birthday concert there, because of all the incredible memories I've had playing the venue."[68] A DVD recording was released as Elton 60—Live at Madison Square Garden.[69]

Billy Joel, who holds the record for the greatest number of appearances at the Garden with 134 shows as of February 2023,[70] stated that the site "has the best acoustics, the best audiences, the best reputation, and the best history of great artists who have played there. It is the iconic, holy temple of rock and roll for most touring acts."[68]

The Grateful Dead performed in the venue 53 times from 1979 to 1994, with the first show being held on January 7, 1979, and the last being on October 19, 1994. Their longest run being done in September 1991.[71]

The Who have headlined at the venue 32 times, including a four-night stand in 1974, a five-night stand in 1979, a six-night stand in 1996, and four-night stands in 2000 and 2002. They also performed at The Concert for New York City in 2001.[72]

On March 10, 2020, a 50th-anniversary celebration of The Allman Brothers Band titled 'The Brothers' took place, featuring the five surviving members of the final Allman Brothers lineup and Chuck Leavell. Dickey Betts was invited to participate but his health precluded him from traveling.[73] This was the final concert at the venue before the COVID-19 pandemic forced its closure. Live shows returned to The Garden when the Foo Fighters headlined a show there on June 20, 2021. The show was for a vaccinated audience only and was the first 100 percent capacity concert in a New York arena since the start of the pandemic.[74]

Other events

[edit]

It hosted Roosevelt's [[2]]'s last 1936 campaign speech, the famous Democratic fundraising gala on Kennedy's birthday in 1962, the 1976 Democratic National Convention,[75] and 1980 Democratic National Convention [75] with Carter, the 1992 Democratic National Convention,[76] with Clinton and the 2004 [77], the 2004 Republican National Convention with Bush, and hosted the NFL draft for many years (later held at Garden-leased Radio City Music Hall, now shared between cities of NFL franchises).[78][79] The Jeopardy! Teen Tournament and several installments of Celebrity Jeopardy! were filmed at MSG in 1999,[80] as well as several episodes of Wheel of Fortune in 1999 and 2013.[81][82]

The New York City Police Academy,[83] Baruch College/CUNY and Yeshiva University also hold their annual graduation ceremonies at Madison Square Garden. It hosted the Grammy Awards in 1972, 1997, 2003, and 2018 (which are normally held in Los Angeles) as well as the Latin Grammy Awards of 2006.

The group and Best in Show competitions of the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show have been held at MSG every February from 1877 to 2020, which was MSG's longest continuous tenant although this was broken in 2021 as the Westminster Kennel Club announced that the event would be held outdoors for the first time due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[84][85]

Notable firsts and significant events

[edit]The Garden hosted the Stanley Cup Finals and NBA Finals simultaneously on two occasions: in 1972 and 1994. MSG has hosted the following All-Star Games:

- NHL All-Star Game: 1973, 1994

- NBA All-Star Game: 1998, 2015

- WNBA All-Star Game: 1999, 2003, 2006

- All American Karate Championships held in 1968 and 1969, both won by Chuck Norris. The 1970 edition was won by Mitchell Bobrow.

- UFC held its first event in New York City, UFC 205: Alvarez vs. McGregor, at Madison Square Garden on November 12, 2016. This was the first event the organization held after New York State lifted the ban on mixed martial arts.

Mike Krzyzewski recorded two notable milestones at the arena. In 2011, he surpassed Bob Knight as the coach with the most wins NCAA Division I men's basketball history when Duke defeated Michigan State. Four years later, a Duke victory over St. John's gave Coach K his 1,000th career win.[86]

Stephen Curry broke the NBA's all-time three-point scoring record at Madison Square Garden, on December 14, 2021. The Warriors defeated the Knicks 105–96 with Curry recording his 2,977th career three-pointer by the end of the game, eclipsing Ray Allen's 2,973 career total.

Recognition given by Madison Square Garden

[edit]Madison Square Garden Gold Ticket Award

[edit]In 1977, Madison Square Garden announced Gold Ticket Awards would be given to performers who had brought in more than 100,000 unit ticket sales to the venue. Since the arena's seating capacity is about 20,000, this would require a minimum of five sold-out shows. Performers who were eligible for the award at the time of its inauguration included Chicago, John Denver, Peter Frampton, the Rolling Stones, the Jackson 5, Elton John, Led Zeppelin, Sly Stone, Jethro Tull, The Who, and Yes.[87][88] Graeme Edge, who received his award in 1981 as a member of The Moody Blues, said he found his gold ticket to be an interesting piece of memorabilia because he could use it to attend any event at the Garden.[89] Many other performers received Gold Ticket Awards between 1977 and 1994.

Madison Square Garden Platinum Ticket Award

[edit]Madison Square Garden also gave Platinum Ticket Awards to performers who sold over 250,000 tickets to their shows throughout the years. Winners of the Platinum Ticket Awards include: the Rolling Stones (1981),[90] Elton John (1982),[91] Yes (1984),[92] Billy Joel (1984),[93] the Grateful Dead (1987),[94] and Madonna (2004).[citation needed]

Madison Square Garden Hall of Fame

[edit]The Madison Square Garden Hall of Fame honors those who have demonstrated excellence in their fields at the Garden. Most of the inductees have been sports figures, however, some performers have been inducted as well. Elton John was reported to be the first non-sports figure inducted into the MSG Hall of Fame in 1977 for "record attendance of 140,000" in June of that year.[95] For their accomplishment of "13 sell-out concerts" at the venue, the Rolling Stones were inducted into the MSG Hall of Fame in 1984, along with nine sports figures icons, bringing the hall's membership to 107.[96]

Madison Square Garden Walk of Fame

[edit]The walkway leading to the arena of Madison Square Garden was designated as the "Walk of Fame" in 1992.[97] It was established "to recognize athletes, artists, announcers and coaches for their extraordinary achievements and memorable performances at the venue."[98] Each inductee is commemorated with a plaque that lists the performance category in which his or her contributions have been made.[97] Twenty-five athletes were inducted into the MSG Walk of Fame at its inaugural ceremony in 1992, a black-tie dinner to raise money to fight multiple sclerosis.[99] Elton John was the first entertainer to be inducted into the MSG Walk of Fame in 1992.[100][101] Billy Joel was inducted at a date after Elton John,[102] and the Rolling Stones were inducted in 1998.[103] In 2015, the Grateful Dead were inducted into the MSG Walk of Fame along with at least three sports-related figures.[102][98]

Capacity

[edit]

|

|

The Theater at Madison Square Garden

[edit]The Theater at Madison Square Garden seats between 2,000 and 5,600 for concerts and can also be used for meetings, stage shows, and graduation ceremonies. It was the home of the NFL draft until 2005, when it moved to the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center after MSG management opposed a new arena for the New York Jets. It also hosted the NBA draft from 2001 to 2010. The theater also occasionally hosts boxing matches.

The fall 1999 Jeopardy! Teen Tournament as well as Celebrity Jeopardy! competitions were held at the theater. Wheel of Fortune taped at the theater twice in 1999 and 2013. In 2004, it was the venue of the Survivor: All-Stars finale. No seat is more than 177 feet (54 m) from the 30' × 64' stage. The theater has a relatively low 20-foot (6.1 m) ceiling at stage level[106] and all of its seating except for boxes on the two side walls is on one level slanted back from the stage. There is an 8,000-square-foot (740 m2) lobby at the theater.

Accessibility and transportation

[edit]

Madison Square Garden sits directly atop a major transportation hub, New York Penn Station, which is served by Long Island Rail Road and NJ Transit commuter rail, as well as Amtrak. The Garden is also accessible via the New York City Subway at the 34th Street–Penn Station (A, C, and E trains) and the 34th Street–Penn Station (1, 2, and 3 trains) stations.[107]

See also

[edit]- List of indoor arenas by capacity

- List of NCAA Division I basketball arenas

- Madison Square Garden Bowl, a former outdoor boxing venue in Queens operated by the Garden company

- Royal Albert Hall

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Wright, Jarah (April 3, 2023). "Madison Square Garden Entertainment splitting into two companies". KTNV-TV. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "Madison Square Garden Entertainment Corp. Completes Spin-Off From Sphere Entertainment Co" (Press release). Madison Square Garden Entertainemnt. April 21, 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d DeLessio, Joe (October 24, 2013). "Here's What the Renovated Madison Square Garden Looks Like". New York Magazine. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ Seeger, Murray (October 30, 1964). "Construction Begins on New Madison Sq. Garden; Grillage Put in Place a Year After Demolition at Penn Station Was Started". The New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Fred Severud; Designed Madison Square Garden, Gateway Arch". Los Angeles Times. June 15, 1990. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ a b "New York Architecture Images- Madison Square Garden Center".

- ^ "Pollstar Pro's busiest arena pdf" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2017.

- ^ Esteban (October 27, 2011). "11 Most Expensive Stadiums in the World". Total Pro Sports. Archived from the original on August 27, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ Mendelsohn, Joyce. "Madison Square" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300055366., p. 711–712

- ^ a b c d e "Madison Square Garden/The Paramount".

- ^ a b Federal Writers' Project (1939). New York City Guide. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.), pp. 330–333

- ^ Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike, Gotham: A History of New York to 1989. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-511634-8

- ^ "Madison Square Garden III" Archived July 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine on Ballparks.com

- ^ Schumach, Murray (February 14, 1948).Next and Last Attraction at Old Madison Square Garden to Be Wreckers' Ball Archived May 11, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times

- ^ Eisenband, Jeffrey. "Remembering The 1948 Madison Square Garden All-Star Game With Marv Albert". ThePostGame. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ^ "Investors Get Madison Sq. Garden". Variety. February 4, 1959. p. 20. Retrieved July 5, 2019 – via Archive.org.

- ^ New York Times: "Irving M. Felt, 84, Sports Impresario, Is Dead" By AGIS SALPUKAS Archived October 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine September 24, 1994

- ^ Massachusetts Institute of Technology: "The Fall and Rise of Pennsylvania Station -Changing Attitudes Toward Historic Preservation in New York City" by Eric J. Plosky Archived January 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine 1999

- ^ Tolchin, Martin (October 29, 1963). "Demolition Starts At Penn Station; Architects Picket; Penn Station Demolition Begun; 6 Architects Call Act a 'Shame'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Muschamp, Herbert (June 20, 1993). "Architecture View; In This Dream Station Future and Past Collide". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ "Rangers on Road in the Bronx? Money May Be Why". New York Times. January 25, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ Brooks, Larry (July 15, 2020). "Igor Shesterkin 'outstanding' in first bid to keep Rangers' starting job". New York Post. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ John Eligon (February 22, 2008). "Joe Louis and Harlem, Connecting Again in a Police Athletic League Gym". The New York Times. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

- ^ Feirstein, Sanna (2001). Naming New York: Manhattan Places & how They Got Their Names. New York University Press. p. 110. ISBN 9780814727126. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

- ^ Phifer, Thomas (January 1, 1989). "Madison Square Garden Site Redevelopment". Oz. 11 (1). doi:10.4148/2378-5853.1181. ISSN 2378-5853.

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (January 24, 1989). "New Project Will Renovate The Garden". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ^ "Gulf & Western has scrapped plans to demolish Madison..." UPI. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ^ Williams, Lena (July 29, 1991). "Big Madison Sq. Garden Facelift: 'Tasteful' With Teal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ^ "ESPN.com - GEN - New Garden in New York considered". www.espn.com. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ^ Staple, Arthur (April 3, 2008). "MSG Executives Unveil Plan for Renovation". Newsday. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ David Mayo (April 9, 2017). "With two arena closings in two days, Detroit stands unique in U.S. history". MLive. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ the Rangers started the 2011–12 NHL season with seven games on the road before playing their first hom game on October 27.Rosen, Dan (September 26, 2010). "Rangers Embrace Daunting Season-Opening Trip". National Hockey League. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ The Knicks played the entire 2012 NBA preseason on the road.Swerling, Jared (August 2012). "Knicks preseason schedule announced". ESPN. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ^ "Madison Square Garden – Official Web Site". Archived from the original on December 1, 2010.

- ^ Bultman, Matthew; McShane, Larry (November 26, 2010). "Madison Square Garden to Add Pedestrian Walkways in Rafters as Part of $775 Million Makeover". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 30, 2010. Retrieved July 3, 2011.

- ^ Scott Cacciola (June 17, 2010). "Cultivating a New Garden". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "First Phase Of Madison Square Garden Renovations Complete". CBS New York. October 19, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ DeLessio, Joe (August 9, 2012). "Hey, So, How's That Madison Square Garden Renovation Going?". New York Magazine. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ "An Inside Look At Madison Square Garden's Latest Renovations". CBS New York. August 12, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (October 25, 2013). "Garden Renovations Come With a Tug of War". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ "Madison Square Garden Unveils New 'Sky Bridge' Seats". CBS New York. October 15, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Hana R. Alberts (May 29, 2013). "Four Plans for a New Penn Station Without MSG, Revealed!". Curbed. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Moynihan Train Hall Finally Opens in Manhattan". NBC New York. December 31, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Dunlap, David (April 9, 2013). "Madison Square Garden Says It Will Not Be Uprooted From Penn Station". The New York Times. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ^ Randolph, Eleanor (June 27, 2013). "Bit by Bit, Evicting Madison Square Garden". The New York Times. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (July 24, 2013). "Madison Square Garden Is Told to Move". The New York Times. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- ^ Hana R. Alberts (October 23, 2014). "Moving the Garden Would Pave the Way for a New Penn Station". Curbed. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "MSG & the Future of West Midtown". Scribd.

- ^ Higgs, Larry (January 6, 2016). "Gov. Cuomo unveils grand plan to rebuild N.Y. Penn Station". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- ^ "6th Proposal of Governor Cuomo's 2016 Agenda: Transform Penn Station and Farley Post Office Building Into a World-Class Transportation Hub". Governor Andrew M. Cuomo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ Kvetenadze, Téa (June 6, 2023). "MTA report says MSG and Penn Station are no longer compatible, fueling debate over the arena's future". New York Daily News. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ "NYC officials set to give James Dolan five-year permit for Madison Square Garden — but battle over site is brewing". New York Post. September 14, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ Hladik, Matt (March 23, 2022). "Report: A Major Change Is Coming To The NIT". The Spun. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ Willis, George (February 11, 2015). "MSG will always be the 'Mecca,' no matter how bad things get". New York Post. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ Yannis, Pat (March 8, 1984). "Hartford Shift Seen For Indoor Cosmos". The New York Times. Retrieved December 22, 2016 – via newyorktimes.com.

- ^ Baker, Mark A. (2019). Between the Ropes at Madison Square Garden, The History of an Iconic Boxing Ring, 1925–2007. ISBN 978-1476671833.

- ^ Fine, Larry (September 19, 2007). "Madison Square Garden ring out for count after 82 years". Reuters.

- ^ Sullivan, Kevin (July 12, 2014). "Madison Square Garden really is the mecca of wrestling arenas". yesnetwork.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ "NJPW Returns to MSG for Wrestle Dynasty August 22 【NJoA】". New Japan Pro-Wrestling. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ "NJPW Postpones Wrestle Dynasty At Madison Square Garden". Wrestling Inc. May 6, 2020.

- ^ "New Japan Pro Wrestling is not coming to the United States this year – Sports Illustrated". www.si.com. July 3, 2020.

- ^ Jarnow, Jesse (August 7, 2017). "Phish's 'Baker's Dozen' Residency: Breaking Down All 13 Blissful Nights". Digiday. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- ^ "Madison Square Garden- Phish.net".

- ^ "Phish Perform Longest "Mike's Song" Equipped with Second Jam for Penultimate Show of MSG Summer Run". Jambands. August 5, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- ^ Iuzzolino, Nicole (February 22, 2023). "Phish to play 7 shows at MSG during 2023 tour". NJ Advance Media. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- ^ "Eric Clapton to Celebrate 70th Birthday With Two Shows at Madison Square Garden". Billboard. April 23, 2016. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ^ a b "Top 10 Rock N' Roll Sites in NYC That You Can Visit Today". Untapped Cities. August 5, 2022. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ "NME article on 60th birthday concert at Madison Square Gardens". NME. UK. March 25, 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ^ "Billy Joel Announces Madison Square Garden Show February 14, 2023". billyjoel.com. October 6, 2022. Archived from the original on August 19, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ [1] Archived June 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, dead.net the official site of the grateful dead

- ^ "The Who Concert Guide – Madison Square Garden". Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ Browne, David (March 19, 2020). "Derek Trucks on Playing Live Before and After the Coronavirus Shutdown". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ "Foo Fighters To Perform At Madison Square Garden's First Full-Capacity Concert". NPR. June 20, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Barrow, Bill (August 5, 2020). "Biden Won't Travel to Milwaukee to Accept Party's Nomination for President, Source Says". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Cronin, Tom; Loevy, Bob (August 1, 2020). "Do national conventions even matter anymore?". Colorado Springs Gazette. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Chung, Jen (August 30, 2019). "15 Years Ago, Protesters Took Over NYC During 2004 Republican National Convention". Gothamist. Archived from the original on September 14, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Levy, Dan. "NFL Draft Is Moving in Wrong Direction". Bleacher Report. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ "Future NFL Draft locations: Host cities for 2020 NFL Draft and beyond". www.sportingnews.com. May 24, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Kaplan, Don (October 11, 1999). "'JEOPARDY!' HITS NYC; GAME SHOW CHALLENGES 'MILLIONAIRE' ON ITS OWN TURF". New York Post. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Weinstein, Farrah (September 26, 1999). "STYLE & SUBSTANCE V-NN- WH-T-". New York Post. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ "WHEEL OF FORTUNE to Tape at Madison Square Garden, 3/15-19; Shows Air May 2013". BroadwayWorld.com. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Formoso, Jessica (October 10, 2019). "NYPD welcomes new class of graduates". FOX 5 NY. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ "Siba the Standard Poodle Wins the 2020 Westminster Dog Show With a Regal Attitude". Time. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Croke, Karen. "Westminster Kennel Club moves its annual dog show to Tarrytown in 2021". The Journal News. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ Phillips, Scott (January 25, 2015). "Coach K earns career win No. 1,000 in No. 5 Duke's win over St. John's". NBC Sports. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ "WNEW Gets Madison Square Garden Award" (PDF). Cash Box. Vol. XXXIX, no. 25. George Albert. November 5, 1977. p. 16. Retrieved March 30, 2019 – via americanradiohistory.com.

- ^ "Box Office Gold Ticket". Billboard. Vol. 89, no. 43. Lee Zhito. October 29, 1977. p. 42. Retrieved March 30, 2019 – via Google books.

- ^ "Graeme Edge Interview with Glide Magazine". The Moody Blues. February 10, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ "Rolling Stones inducted into Hall". The Central New Jersey Home News. New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA. June 14, 1984. p. 14, On the Go! section. Retrieved April 6, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Elton gets award". Tampa Bay Times. St. Petersburg, Florida, USA. August 7, 1982. p. 6A. Retrieved April 6, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Yes, that's quite a feat". Daily News. New York, New York, USA. May 16, 1984. p. 83. Retrieved April 6, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hot Ticket". The Desert Sun. Palm Springs, California, USA. July 7, 1984. p. D12. Retrieved April 6, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jaeger, Barbara (October 1, 1987). "Records, Etc.: The Grateful Dead". The Record. Hackensack, New Jersey, USA. p. E-10. Retrieved April 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Elton in Manhattan" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 89, no. 43. Lee Zhito. October 29, 1977. p. 3. Retrieved April 2, 2019 – via AmericanRadioHistory.com.

- ^ Thomas, Robert MCG. Jr. (May 7, 1984). "Sports World Specials". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ a b "Madison Square Garden Guide". CBS New York. October 19, 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Scott (May 11, 2015). "Grateful Dead Inducted into MSG Walk of Fame". JamBase. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ "Madison Square Garden Gets Walk of Fame". The Seattle Times. Seattle, Washington, USA. Associated Press. September 12, 1992. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ "This Day in History: October 9: Also on this date in: 1992". Cape Breton Post. Sydney, Nova Scotia, Canada. October 9, 2010. Retrieved April 16, 2019 – via PressReader.

- ^ Gregory, Andy, ed. (2002). International Who's Who in Popular Music 2002. London, England: Europa Publications. p. 260 See entry "John Elton (Sir)". ISBN 9781857431612.

- ^ a b Biese, Alex (May 15, 2015). "Long, strange trip to NYC". The Courier-News. Bridgewater, New Jersey, USA. p. 2, Kicks section. Retrieved April 16, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Artists & Music: Walk This Way" (PDF). Billboard. Howard Lander. February 14, 1998. p. 12. Retrieved April 16, 2019 – via AmericanRadioHistory.

- ^ "2011–2012 New York Knicks Media Guide" (Document). New York Knicks.

- ^ "2011–2012 New York Rangers Media Guide" (Document). New York Rangers.

- ^ "Wintuk created exclusively for Wamu Theater at Madison Square Garden" Archived March 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, cirquedusoleil.com, November 7, 2007

- ^ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

Sources

[edit]- McShane, Larry. "Looking Back at 125 Years of Madison Square Garden". New York City. Archived from the original on August 30, 2005. Retrieved August 7, 2005.

- "MSG: Corporate Information". Archived from the original on August 6, 2005. Retrieved August 7, 2005.

- "Rent The Garden". Archived from the original on March 5, 2005. Retrieved August 7, 2005.

- Bagli, Charles V. (September 12, 2005). "Madison Square Garden's Owners Are in Talks to Replace It, a Block West". The New York Times.

- Huff, Richard (August 8, 2006). "Arena's the Star of MSG Revamp". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on September 2, 2024. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- Anderson, Dave (February 19, 1981). "Sports of the Times; Dues for the City". The New York Times.

- "A Garden Built For Tomorrow," Sports Illustrated, January 2, 1967.

- Madison Square Garden under construction from the Hagley Digital Archives

External links

[edit]- Madison Square Garden Sports

- Madison Square Garden

- 1968 establishments in New York City

- 1998 Goodwill Games venues

- Athletics (track and field) venues in New York City

- Basketball venues in New York (state)

- Basketball venues in New York City

- Boxing venues in New York City

- College basketball venues in the United States

- College ice hockey venues in the United States

- College wrestling venues in the United States

- Convention centers in New York City

- Eighth Avenue (Manhattan)

- Esports venues in New York (state)

- Former Viacom subsidiaries

- Gulf and Western Industries

- Gymnastics venues in New York City

- Indoor arenas in New York City

- Ice hockey venues in New York City

- Indoor lacrosse venues in the United States

- Indoor soccer venues in New York (state)

- Indoor track and field venues in New York (state)

- Manhattan Jaspers men's basketball

- Mixed martial arts venues in New York (state)

- Music venues in Manhattan

- NBA venues

- National Hockey League venues

- New York Knicks

- New York Liberty

- New York Rangers

- North American Soccer League (1968–1984) indoor venues

- Pennsylvania Plaza

- Round buildings

- Sports venues completed in 1968

- Sports venues in Manhattan

- St. John's Red Storm basketball venues

- Tourist attractions in Manhattan

- Women's National Basketball Association venues

- World Hockey Association venues

- Wrestling venues in New York City

- WWE