Middlesbrough

| Middlesbrough | |

|---|---|

| |

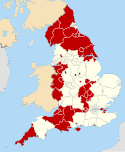

Location within North Yorkshire | |

| Population | 174,700 (2011 Census) |

| Demonym | Teessider |

| OS grid reference | NZ495204 |

| • London | 217 mi (349 km) S |

| Unitary authority |

|

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MIDDLESBROUGH |

| Postcode district | TS1 – TS9 |

| Dialling code | 01642 |

| Police | Cleveland |

| Fire | Cleveland |

| Ambulance | North East |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | middlesbrough.gov.uk |

Middlesbrough (/ˈmɪdəlzbrə/ MID-əlz-brə) is a large post-industrial town[1][2] on the south bank of the River Tees in North Yorkshire, northeast England, founded in 1830.[3] The local council, a unitary authority, is Middlesbrough Borough Council. The 2011 Census recorded the borough's total resident population as 138,400 and the wider urban settlement with a population of 174,700, technically making Middlesbrough the largest urban subdivision in the ceremonial county of North Yorkshire.[4] Middlesbrough is part of the larger built-up area of Teesside which had an overall population of 376,333 at the 2011 Census.[5]

Middlesbrough became a county borough within the North Riding of Yorkshire in 1889. In 1968, the borough was merged with a number of others to form the County Borough of Teesside, which was absorbed in 1974 by the county of Cleveland. In 1996, Cleveland was abolished, and Middlesbrough Borough Council became a unitary authority within North Yorkshire. RGs Erimus ("We shall be" in Latin) was chosen as Middlesbrough's motto in 1830. It recalls Fuimus ("We have been") the motto of the Norman/Scottish Bruce family, who were lords of Cleveland in the Middle Ages. The town's coat of arms is an azure lion, from the arms of the Bruce family, a star, from the arms of Captain James Cook, and two ships, representing shipbuilding and maritime trade.[6]

History

Early history

In 686, a monastic cell was consecrated by St. Cuthbert at the request of St. Hilda, Abbess of Whitby and in 1119 Robert Bruce, Lord of Cleveland and Annandale, granted and confirmed the church of St. Hilda of Middleburg to Whitby.[7] Up until its closure on the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII in 1537,[8] the church was maintained by 12 Benedictine monks, many of whom became vicars, or rectors, of various places in Cleveland. The importance of the early church at "Middleburg", later known as Middlesbrough Priory, is indicated by the fact that, in 1452, it possessed four altars.[citation needed]

After the Angles, the area became home to Viking settlers. Names of Viking origin (with the suffix by) are abundant in the area – for example, Ormesby, Stainsby, Maltby and Tollesby were once separate villages that belonged to Vikings called Orm, Steinn, Malti and Toll, but now form suburbs of Middlesbrough. The name Mydilsburgh is the earliest recorded form of Middlesbrough's name and dates from the Anglo-Saxon era (AD 410–1066), while many of the aforementioned villages are recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086.

Other links persist in the area, often through school or road names, to now-outgrown or abandoned local settlements, such as the medieval settlement of Stainsby, deserted by 1757, which amounts to little more today than a series of grassy mounds near the A19 road.[9]

Development

In 1801, Middlesbrough was a small farm with a population of just 25. During the latter half of the 19th century, however, it experienced rapid growth.

The Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR) had been developed to transport coal from Witton Park Colliery and Shildon in County Durham, to the River Tees in the east. It had always been assumed by the investors that Stockton as the then lowest bridging point on the River Tees would be suitable to take the largest ships at the required volume. However, as the trade developed, and with competition from the Clarence Railway which had established a new port on the north side of the river at Port Clarence, a better solution was required on the south side of the river.

In 1828 the influential Quaker banker, coal mine owner and S&DR shareholder Joseph Pease sailed up the River Tees to find a suitable new site down river of Stockton on which to place new coal staithes. As a result, in 1829 he and a group of Quaker businessmen bought the Middlesbrough farmstead and associated estate, some 527 acres (213 ha) of land, and established the Middlesbrough Estate Company. Through the company, the investors set about the development of a new coal port on the banks of the Tees nearby, and a suitable town on the site of the farm (the new town of Middlesbrough) to supply the port with labour. By 1830 the S&DR had been extended to Middlesbrough and expansion of the town was assured. The small farmstead became the site of such streets as North Street, South Street, West Street, East Street, Commercial Street, Stockton Street and Cleveland Street, laid out in a grid-iron pattern around a market square, with the first house being built in West Street in April 1830.[10] The town of Middlesbrough was born.[11] New businesses quickly bought up premises and plots of land in the new town and soon shippers, merchants, butchers, innkeepers, joiners, blacksmiths, tailors, builders and painters were moving in. By 1851 Middlesbrough's population had grown from 40 people in 1829 to 7,600.[12]

The first coal shipping staithes at the port (known as "Port Darlington") were constructed just to the west of the site earmarked for the location of Middlesbrough.[13][14] The port was linked to the S&DR on 27 December 1830 via a branch that extended to an area just north of the current Middlesbrough railway station.[15] The success of the port meant it soon became overwhelmed by the volume of imports and exports, and in 1839 work started on Middlesbrough Dock. Laid out by Sir William Cubitt, the whole infrastructure was built by resident civil engineer George Turnbull.[13] After three years and an expenditure of £122,000 (equivalent to £9.65 million at 2011 prices),[13] first water was let in on 19 March 1842, and the formal opening took place on 12 May 1842. On completion, the docks were bought by the S&DR.[13]

Industrialisation

Ironstone was discovered in the Eston Hills in 1850. In 1841, Henry Bolckow, who had come to England in 1827, formed a partnership with John Vaughan, originally of Worcester, and started an iron foundry and rolling mill at Vulcan Street in the town. It was Vaughan who realised the economic potential of local ironstone deposits. Pig iron production rose tenfold between 1851 and 1856. The importance of the area to the developing iron and steel trade gave it the nickname "Ironopolis".[16][17]

On 21 January 1853, Middlesbrough received its Royal Charter of Incorporation,[18] giving the town the right to have a mayor, aldermen and councillors. Henry Bolckow became mayor, in 1853.

On 15 August 1867, a Reform Bill was passed, making Middlesbrough a new parliamentary borough, Bolckow was elected member for Middlesbrough the following year.

For many years in the 19th century, Teesside set the world price for iron and steel.[citation needed] The steel components of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (1932) were engineered and fabricated by Dorman Long of Middlesbrough. The company was also responsible for the New Tyne Bridge in Newcastle.[19]

Several large shipyards also lined the Tees, including the Sir Raylton Dixon & Company, which produced hundreds of steam freighters including the infamous SS Mont-Blanc, the steamship which caused the 1917 Halifax Explosion in Canada.

Middlesbrough's rapid expansion continued throughout the second half of the 19th century (fuelled by the iron and steel industry), the population reaching 90,000 by the turn of the century.[12] The population of Middlesbrough as a county borough peaked at almost 165,000 in the late 1960s, but has declined since the early 1980s. The 2011 Census recorded the borough's total resident population as 138,400.

Irish migration to Middlesbrough

The 1871 census of England & Wales showed that Middlesbrough had the second highest percentage of Irish born people in England after Liverpool.[20][21] This equated to 9.2% of the overall population of the district at the time.[22] Due to the rapid development of the town and its industrialisation there was much need for people to work in the many blast furnaces and steel works along the banks of the Tees. This attracted many people from Ireland, who were in much need of work. As well as people from Ireland, the Scottish, Welsh and overseas inhabitants made up 16% of Middlesbrough's population in 1871.[21]

Economy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

Business in Middlesbrough is still dominated by the nearby chemical industry which until 1995 in this locality was largely owned by Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI). The fragmentation of that company led to many smaller manufacturing units being owned and operated by a number of multinational organisations. The last part of ICI itself completely left the area in 2006 and the remaining companies are now members of the Northeast of England Process Industry Cluster (NEPIC).

The port of Teesport, owned by PD Ports, is also vital to the economy of Middlesbrough and the port owners have their offices in the town. Teesport is 5.5 miles (9 km) from the North Sea and 3 miles (5 km) east of Middlesbrough, on the River Tees. Teesport is currently the third largest port in the United Kingdom, and amongst the tenth biggest in Western Europe, handling about 50 million tonnes of domestic and international cargo per year.[23] The vast majority of these products are still related to the steel and chemical industries made by companies that are members of NEPIC. NEPIC is an industry led economic cluster body that promotes the development and growth of the chemistry based process industries around the Tees Valley and the wider region of Northeast England.

Middlesbrough also remains a stronghold for engineering based manufacturing and engineering contract service businesses. It also has a growing reputation for developing digital businesses particularly in the field of digital animation as a result of spin-out activity in this new industry from the Middlesbrough-based Teesside University.

Middlesbrough is served by its town centre which consists of four shopping centres, the largest of which is the Cleveland Centre. The pedestrianised section of Linthorpe Road includes House of Fraser and Debenhams. The town centre has a variety of stores from high street chains to aspirational and lifestyle brands.

Second World War

Middlesbrough was the first major British town and industrial target to be bombed during the Second World War. The steel making capacity and railways for carrying steel products were obvious targets. The Luftwaffe first bombed the town on 25 May 1940, when a lone bomber dropped 13 bombs between South Bank Road and the South Steel plant.[24] More bombing occurred throughout the course of the war, with the railway station put out of action for two weeks in 1942.[25]

By the end of the war over 200 buildings had been destroyed within the Middlesbrough area. Areas of early and mid-Victorian housing were demolished and much of central Middlesbrough was redeveloped. Heavy industry was relocated to areas of land better suited to the needs of modern technology. Middlesbrough itself began to take on a completely different look.[26]

Green Howards

The Green Howards was a British Army infantry regiment very strongly associated with Middlesbrough and the area south of the River Tees. Originally formed at Dunster Castle, Somerset in 1688 to serve King William of Orange, later King William III, this famous regiment became affiliated to the North Riding of Yorkshire in 1782. As Middlesbrough grew, its population of men came to be a group most targeted by the recruiters. The Green Howards were part of the King's Division. On 6 June 2006, this famous regiment was merged into the new Yorkshire Regiment and are now known as 2 Yorks – The 2nd Battalion The Yorkshire Regiment (Green Howards). There is also a Territorial Army (TA) company at Stockton Road in Middlesbrough, part of 4 Yorks which is wholly reserve.

Governance

| Year | Name of Mayor |

|---|---|

| 1853 | Henry William Ferdinand Bolckow |

| 1854 | Isaac Wilson |

| 1855 | John Vaughan |

| 1856 | Henry Thompson |

| 1858 | John Richardson |

| 1859 | William Fallows |

| 1860 | George Bottomley |

| 1861 | James Harris |

| 1862 | Thomas Brentnall |

| 1863 | Edgar Gilkes |

Middlesbrough was incorporated as a municipal borough in 1853. It extended its boundaries in 1866 and 1887, and became a county borough under the Local Government Act 1888. A Middlesbrough Rural District was formed in 1894, covering a rural area to the south of the town. It was abolished in 1932, partly going to the county borough; but mostly going to the Stokesley Rural District.[28]

In 1968 Middlesbrough became part of the County Borough of Teesside, and in 1974 it became part of the non-metropolitan county of Cleveland until the county's abolition in 1996, when Middlesbrough became a unitary authority. The town now forms part of North Yorkshire for ceremonial purposes only.

Politics

Currently the Middlesbrough constituency is represented by Andy McDonald for Labour in the House of Commons. He was elected in a by-election held on 29 November 2012 following the death of previous Member of Parliament Sir Stuart Bell, who was the MP since 1983.

Middlesbrough has been a traditionally safe Labour seat. The first Conservative MP for Middlesbrough was Sir Samuel Alexander Sadler, elected in 1900.

Local Government

- Mayor

In 2002, Middlesbrough voted to have a directly elected mayor as head of the council. Ray Mallon (independent), formerly a senior officer in Cleveland Police was the first elected mayor, serving three terms of office beginning in 2002, 2007 and 2011. In May 2015, after Mallon stated he would not contest a fourth term, Dave Budd (Labour) was voted in, narrowly defeating Andy Preston (independent).[29]

Before having an elected mayor, the council had a ceremonial mayor. The functions of this office have been transferred to the office of "Chair of Middlesbrough Council".

The first Mayor of Middlesbrough was the German-born Henry Bolckow in 1853.[30][31] In the 20th century, encompassing introduction of universal suffrage in 1918 and changes in local government in the United Kingdom, the role of mayor changed. Unlike some other places with a "City Mayor" and "Ceremonial Mayor", the traditional civic and ceremonial functions of the Mayor, including mayoral chains and robes, are now vested with the role now called 'Chair of Middlesbrough Council'. The Chair is still chosen by the Council from among the elected Councillors.

Geography

The following list are the different wards, districts and suburbs that make up the Middlesbrough built-up area. (* areas that form part of built-up area under Redcar & Cleveland Council)

- Acklam

- Ayresome

- Beckfield

- Beechwood

- Berwick Hills

- Brambles Farm

- Brookfield

- Central Middlesbrough

- Clairville

- Coulby Newham

- Easterside

- Eston*

- Grangetown*

- Gresham

- Grove Hill

- Hemlington

- Kader

- Ladgate

- Linthorpe

- Marton-in-Cleveland

- Marton Grove

- Marton West

- Middlehaven

- Normanby*

- North Ormesby

- Nunthorpe

- Ormesby

- Pallister

- Park End

- Priestfields

- Saltersgill

- South Bank*

- St. Hilda's

- Stainton-in-Cleveland

- Teesville*

- Thorntree

- Netherfields

- Tollesby

- Town Centre

- Town Farm

- West Lane

- Whinney Banks

Climate

Middlesbrough has an oceanic climate typical for the United Kingdom. Being sheltered from prevailing south-westerly winds by both the Lake District and Pennines to the west and the Cleveland Hills to the south, Middlesbrough is in one of the relatively drier parts of the country, receiving on average 574 millimetres (22.6 inches) of rain a year. Temperatures range from mild summer highs in July and August typically around 20 °C (68 °F) to winter lows in December and January falling to around 0 °C (32 °F).[32]

| Climate data for Middlesbrough, England | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.8 (44.2) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.1 (68.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.8 (42.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.7 (51.3) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

3.2 (37.8) |

0.7 (33.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41.1 (1.62) |

32.9 (1.30) |

36.3 (1.43) |

41.5 (1.63) |

40.8 (1.61) |

52.4 (2.06) |

52.9 (2.08) |

60.6 (2.39) |

49.7 (1.96) |

57.5 (2.26) |

60.2 (2.37) |

48.2 (1.90) |

574.2 (22.61) |

| Average precipitation days | 9.9 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 9.0 | 8.7 | 9.1 | 9.8 | 8.0 | 9.8 | 11.8 | 10.6 | 111.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 54.8 | 71.3 | 102.7 | 132.4 | 174.6 | 168.3 | 170.6 | 160.7 | 125.9 | 93.3 | 59.8 | 45.5 | 1,360 |

| Source: UK Met Office[33] | |||||||||||||

Transport

Middlesbrough is served well by public transport. Locally, Arriva North East and Stagecoach provide the majority of bus services, with National Express and Megabus operating long distance coach travel from Middlesbrough bus station.

Train services are operated by Northern and TransPennine Express. Departing from Middlesbrough railway station, Northern operates rail services throughout the north-east region including to Newcastle, Sunderland, Darlington, Redcar and Whitby, whilst TransPennine Express provides direct rail services to cities such as Leeds, York, Liverpool and Manchester.

Middlesbrough is served by a number of major roads including the A19 (north/south), A66 (east/west), A171, A172 and A174.

In the past Middlesbrough has been served by the Middlesbrough, Stockton and Thornaby Electric Tramways Company, Imperial Tramways Company, Middlesbrough Corporation Tramways, Tees-side Railless Traction Board and Teesside Municipal Transport.

Landmarks

In the suburb and former village of Acklam, Middlesbrough's oldest domestic building is Acklam Hall of 1678. Built by Sir William Hustler, it is also Middlesbrough's sole Grade I listed building.[34][35] The Restoration mansion, accessible through an avenue of trees off Acklam Road, has seen progressive updates through the centuries, making a captivating document of varying trends in English architecture.

Via a 1907 Act of Parliament, Sir William Arrol & Co. of Glasgow built the Transporter Bridge (1911) which spans the River Tees between Middlesbrough and Port Clarence. At 850 feet (260 m) long and 225 feet (69 m) high, is one of the largest of its type in the world, and one of only two left in working order in Britain (the other being in Newport). The bridge remains in daily use. It is, a Grade II* listed building.

Another landmark, the Tees Newport Bridge, a vertical lift bridge, opened further along the river in 1934. Newport bridge still stands and is passable by traffic, but it can no longer lift the centre section.

The urban centre of Middlesbrough remains home to a variety of architecture ranging from the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, opened in January 2007 to replace a number of former outlying galleries; and Centre North East, formerly Corporation House, which opened in 1971. Many believe that there is a beauty to be found in the surrounding landscape of industry along the River Tees from Billingham to Wilton. The terraced Victorian streets surrounding the town centre are characterful elements of Middlesbrough's social and historical identity, and the vast streets surrounding Parliament Road and Abingdon Road a reminder of the area's wealth and rapid growth during industrialisation.

Middlesbrough Town Hall, designed by George Gordon Hoskins and built between 1883 and 1889 is a Grade II listed building, and a very imposing structure. Of comparable grandeur, is the Empire Palace of Varieties, of 1897, the finest surviving theatre edifice designed by Ernest Runtz in the UK. The first artist to star there in its guise as a music hall was Lillie Langtry. Later it became an early nightclub (1950s), then a bingo hall and is now once again a nightclub. Further afield, in Linthorpe, is the Middlesbrough Theatre opened by Sir John Gielgud in 1957; it was one of the first new theatres built in England after the Second World War.

The town includes England's only public sculpture by Claes Oldenburg,[citation needed] the "Bottle O' Notes" of 1993, which relates to Captain James Cook. Based alongside it today in the town's Central Gardens is the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (MIMA). Refurbished in 2006, is the Carnegie library, dating from 1912. The Dorman Long office on Zetland Road, constructed between 1881 and 1891, is the only commercial building ever designed by Philip Webb, the architect who worked for Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell.

Away from the town centre, at Middlehaven stands the Temenos sculpture, designed by sculptor Anish Kapoor and designer Cecil Balmond. The steel structure, consisting of a pole, a circular ring and an oval ring, stands approximately 110 m long and 50 m high and is held together by steel wire. It was unveiled in 2010 at a cost of £2.7 million.

Culture and leisure

The Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art opened its doors in January 2007. It holds works by Frank Auerbach, Tracey Emin and Paula Rego among others. Its considerable arts and crafts collections span from 1900 to the present day.

Middlesbrough also has a healthy musical heritage. A number of bands and musicians hail from the area, including Paul Rodgers, Chris Rea, and Micky Moody.

Middlesbrough has two major recreational park spaces in Albert Park and Stewart Park, Marton. Albert Park was donated to the town by Henry Bolckow in 1866. It was formally opened by Prince Arthur on 11 August 1868, and comprises a 30 hectares (74 acres) site. The park underwent a considerable period of restoration from 2001 to 2004, during which a number of the park's landmarks, saw either restoration or revival. Stewart Park was donated to the people of Middlesbrough in 1928 by Councillor Thomas Dormand Stewart and encompasses Victorian stable buildings, lakes and animal pens. During 2011 and 2012, the park underwent major refurbishment. Alongside these two parks are two of the town's cultural attractions, the century-old Dorman Memorial Museum and the Captain Cook Birthplace Museum.

Newham Grange Leisure farm in Coulby Newham, one of the most southerly districts of the town, has operated continuously in this spot since the 17th century, becoming a leisure farm with the first residential development of the suburb in the 1970s. It is now a burgeoning tourist attraction: the chance to view its cattle, pigs, sheep and other farm animals is complemented by exhibitions of the farming history of the area.

Middlesbrough is famous for the Parmo, a version of scallopini Parmigiana or schnitzel consisting of deep-fried breaded chicken or pork cutlet, topped with thick béchamel sauce and grilled cheese. It is usually served with chips, salad & garlic sauce, with variations such as hotshot and fungi. Although it can be seen primarily as a takeaway dish, popular with Teessiders after a night out, it is also a popular restaurant dish with many establishments in around Teesside serving restaurant quality versions.

In the Middlehaven ward, is the Transporter Bridge Visitor Centre, opened in 2000 and offering its own exhibitions charting the stirring past of the surrounding industrial powerhouse, as well as that of the singular structure it commemorates.

Sport

Middlesbrough is home to the Championship football team, Middlesbrough F.C., owned by local haulage entrepreneur Steve Gibson. The club is based at the Riverside Stadium on the banks of the River Tees, where they have played since moving from Ayresome Park, their home for 92 years until 1995. Founder members of the Premier League in 1992, Middlesbrough won the Football League Cup in 2004,[36] and were beaten finalists in the 2005-06 UEFA Cup.[37] In 1905 they made history with Britain's first £1,000 transfer when they signed Alf Common from local rivals Sunderland.[38] Another league club, Middlesbrough Ironopolis F.C., was briefly based in the town in the late 19th century, but folded within a few years.

Speedway racing was staged at Cleveland Park Stadium from the pioneer days of 1928 until the 1990s. The post-war team, known as The Middlesbrough Bears, and for a time, The Teessiders, the Teesside Tigers and the Middlesbrough Tigers operated at all levels. The track operated for amateur speedway in the 1950s before re-opening in the Provincial League of 1961. The track closed for a spell later in the 1960s but returned in as members of the Second Division as The Teessiders.

Middlesbrough is also represented nationally in Futsal. Middlesbrough Futsal Club play in the FA Futsal League North, the national championship and their home games are played in Thornaby at Thornaby Pavilion.

Athletics is a major sport in Middlesbrough with two local clubs serving Middlesbrough and the surrounding Teesside area, Middlesbrough and Cleveland Harriers and Middlesbrough AC (Mandale). Athletes used to regularly train at Clairville Stadium (1963-2014) until it was closed and subsequently demolished to make way for a housing development. Athletes now train at the recently opened (May 2015)[39] Middlesbrough Sports Village, on Marton Road (A172). Notable athletes to train at both facilities are World & European Indoor Sprint Champion Richard Kilty, British Indoor Long Jump record holder Chris Tomlinson and current British Internationals Matthew Hynes, Jonathon Taylor, Rabah Yousif and Amy Carr. The sports village includes a running track with grandstand, an indoor gym and cafe, football pitches, cycle circuit and a velodrome. Adjacent to the sports village is a skateboard plaza and also Middlesbrough Tennis World.

Middlesbrough hosts several road races through the year. In September, the annual Middlesbrough Tees Pride 10k road race[40] is held on a one lap circuit round the southern part of the town. First held in 2005, the race now attracts several thousand competitors, from the serious club athlete to those in fancy dress raising money for local charities. Road races and training are also held regularly at Middlesbrough Cycle Circuit which is at the Middlesbrough Sports Village.

Middlesbrough RUFC opened services in 1872, and are currently members of the Yorkshire Division One. They have played their home games at Acklam Park since 1929, and have a ground-share with Middlesbrough Cricket Club, which commenced in 1930.

Education

Middlesbrough became a university town in 1992, after a campaign[by whom?] for a distinct "Teesside University" since the 1960s. Before its establishment, extramural classes had been provided by the University of Leeds Adult Education Centre on Harrow Road, from 1958 to 2001.[41] Teesside University has more than 20,000 students. It dates back to 1930 as Constantine Technical College. Current departments of the university include Teesside University Business School and Schools of Arts and Media, Computing, Health and Social Care, Science & Engineering and Social Sciences & Law. The university teaches computer animation and games design and co-hosts the annual Animex International Festival of Animation and Computer Games. The university also has links with the James Cook University Hospital south of the town centre.

There are also modern schools, colleges and sixth forms colleges, the largest of which is Middlesbrough College, in Middlehaven, with 16,000 students. Others include Trinity Catholic College in Saltersgill[42] and Macmillan Academy on Stockton Road. The Northern School of Art, which opened in 1960, is also based in Middlesbrough and Hartlepool. It is one of only four specialist art and design further education colleges in the United Kingdom.

Secondary schools

Secondary schools in Middlesbrough include:

- Acklam Grange School, also home to the Acorn Sports Centre ISHA

- Outwood Academy Acklam

- Trinity Catholic College

- The King's Academy

- Unity City Academy

- Macmillan Academy[43]

- Hillsview Academy

- Beverley School

- Nunthorpe Academy

- Outwood Academy Ormesby

- St Peter's Catholic Voluntary Academy

Demography

In 2011, Middlesbrough had a population of 174,700,[4] which makes it the largest town in North East England and largest urban settlement within the non-administrative ceremonial county of North Yorkshire. The borough had a population of 138,412 at the same census. For comparison, the Built-up area sub-division (BUASD) is about the same size as Bournemouth, the largest town in South West England. Middlesbrough town is larger than the borough. The town is made up of the borough, as well as the suburbs which make up the area known as Greater Eston, which is to the east of the borough in Redcar and Cleveland. Greater Eston does not have a very high ethnic minority population, which makes the town less ethnically diverse than the smaller borough.

| Middlesbrough compared 2011 | Middlesbrough BUASD | Middlesbrough (borough) |

|---|---|---|

| White British | 88.4% | 86.0% |

| Asian | 6.4% | 7.8% |

| Black | 1.0% | 1.3% |

In the borough of Middlesbrough, 14.0% of the population were non-white British, compared with only 11.6% for the town. This makes the town about as ethnically diverse as Exeter. Additionally, it has a lower white British population than Gateshead and South Shields which are further north on the other side of County Durham. It is also the second most ethnically diverse settlement in the North East (after Newcastle). The town of Middlesbrough is recognised as a Built-up area sub-division (BUASD) of Teesside by the Office for National Statistics.[5]

Accent

Middlesbrough English[46] is often grouped with the accents of North East England such as Geordie (spoken in Tyneside) and Mackem (spoken on Wearside) and occasionally with the accents of Yorkshire as it shares characteristics of both. Furthermore, the accent reflects the town's history. This accent is also known as a Smoggie accent or a Teesside accent.

Distinct vowels

Nurse/Square

A recognisable feature of Middlesbrough English is the fronted form of NURSE,[47] reflecting its similarity with Liverpool English, having the characteristic NURSE/SQUARE merger at [ɛ:]. Additionally, the form is found to be the preferred variant of female speakers.[48] This can be heard in words like work, purple, dirt and shirt which are pronounced more like "werk/wairk", "perple/pairple", "dert/dairt" and "shert/shairt".

Another feature of the Middlesbrough accent is the presence of a harsh "CK" sound. This indicates a possible influence from the many Welsh speakers that inhabited Middlesbrough at the same time as the Irish. Words such as black,track and crack often have an emphasis on the ck which give it a sound of clearing the throat. Not only is this feature prominent in Welsh speakers but it is also present in speakers from Liverpool. This further suggests the similarities between speakers from Middlesbrough and the Liverpool area.

Religion

Christianity

Middlesbrough is a deanery of the Archdeaconry of Cleveland, a subdivision of the Church of England Diocese of York in the Province of York. It stretches west from Thirsk, north to Middlesbrough, east to Whitby and south to Pickering.

Middlesbrough is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Middlesbrough, which was created on 20 December 1878 from the Diocese of Beverley. Middlesbrough is home to the Mother-Church of the diocese, St. Mary's Cathedral, which is in the suburb of Coulby Newham and Sacred Heart Church in the centre of the town. The present bishop is the Right Reverend Terence Patrick Drainey, 7th Bishop of Middlesbrough, who was ordained on Friday 25 January 2008.

St Stephen's church, Middlesbrough, near the university campus, is a Church of England parish church, but is also in the Evangelical Connexion.[49]

Judaism

Ashkenazi Jews started to settle in Middlesbrough from 1862 and formed Middlesbrough Hebrew Congregation in 1870 with a synagogue in Hill Street. The synagogue moved to Brentnall Street in 1874 and then to a new building in Park Road South in 1938.[50]

Editions of the Jewish Year Book record the growth and decline of Middlesbrough's Jewish population. It was about 100 in 1896–97 and peaked at 750 in 1935. It then declined to 30 in 1998, in which year the synagogue in Park Road South was ceremonially closed.[50]

Islam

The Islamic community is represented in several mosques in Middlesbrough. Muslim sailors visited Middlesbrough from about 1890.[51] and, in 1961, Azzam and Younis Din opened the first Halal butcher shop.[51] The first mosque was a house in Grange Road in 1962.[51] The Al-Madina Jamia Mosque, on Waterloo Road, the Dar ul Islam Central Mosque, on Southfield Road, and the Abu Bakr Mosque & Community Centre,[52] which is on Park Road North, are among the best known mosques in Middlesbrough today.

Sikhism

The Sikh community established its first gurdwara (temple) in Milton Street in 1967.[51] After a time in Southfield Road, the centre is now in Lorne Street and was opened in 1990.[51]

Hinduism

There is a Hindu Cultural Centre in Westbourne Grove, North Ormesby, which was opened in 1990.[51]

Television and filmography

Middlesbrough has featured in many television programmes, including The Fast Show, Inspector George Gently, Steel River Blues, Spender, Play for Today (The Black Stuff; latterly the drama Boys from the Blackstuff) and Auf Wiedersehen, Pet.[53]

Film director Ridley Scott is from the North East and based the opening shot of Blade Runner on the view of the old ICI plant at Wilton. He said: “There’s a walk from Redcar … I’d cross a bridge at night, and walk above the steel works. So that’s probably where the opening of Blade Runner comes from. It always seemed to be rather gloomy and raining, and I’d just think “God, this is beautiful.” You can find beauty in everything, and so I think I found the beauty in that darkness.” Apparently the site was also considered as a shooting location for one of the sequels to Scott's Alien film.[54]

Some of the film Billy Elliot was filmed on the Middlesbrough Transporter Bridge.[53]

In May 2008, Middlesbrough was chosen as one of the sites in the BBC's Public Space Broadcasting Project. Like other towns participating in the project, Middlesbrough was offered a large 27 m2 (290 sq ft) television screen by the BBC and the London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games. The screen was installed on 11 July 2008 and is at the western end of Centre Square.

In the 2009 action thriller The Tournament Middlesbrough is that year's location where the assassins' competition is being held.

In November 2009, the MiMA art gallery was used by the presenters of Top Gear as part of a challenge. The challenge was to see if car exhibits would be more popular than normal art.[55]

In March 2013, Middlesbrough was used as a stand in for Newcastle 1969 in BBC's Inspector George Gently starring Martin Shaw and Lee Ingleby; the footage appeared in the episode "Gently Between The Lines" (episode 1 of series 6).

Reference is also made to Middlesbrough in works by London author Paul Breen including a work of fiction entitled "The Bones of a Season".[citation needed]

In 2010, filmmaker John Walsh made the satirical documentary ToryBoy The Movie about the 2010 general election in the Middlesbrough constituency and sitting MP Stuart Bell's alleged laziness as an MP.[56][57][58]

Notable people

Captain James Cook (1728–79) the world-famous explorer, navigator, and cartographer was born in Marton, now a suburb in the south of Middlesbrough.

Tom Dresser (1892-1992), Middlesbrough's first Victoria Cross recipient during the First World War.

Stanley Hollis (1912–72), recipient of the only Victoria Cross awarded on D-Day (6 June 1944).[59]

Ellen Wilkinson was a famous MP for Middlesbrough East, and was the first female Minister of Education. She also wrote a novel Clash (1929) which paints a very positive picture of "Shireport" (Middlesbrough).

Steph McGovern, a business journalist for the BBC, grew up in Middlesbrough.

Marion Coates Hansen was an active member of the local Independent Labour Party (ILP). She was a feminist and women's suffrage campaigner, an early member of the militant Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and a founder member of the Women's Freedom League (WFL) in 1907.

Maud Chadburn was one of the earliest women in the United Kingdom to pursue a career as a surgeon. She also co-founded the South London Hospital for Women and Children in 1912 with fellow surgeon Eleanor Davies-Colley.

Other famous people from Middlesbrough include:

Sports

- Footballers Brian Clough, Wilf Mannion, Jacky Carr, Don Revie, Alan Peacock, Peter Beagrie, Chris Kamara, Mark Proctor, Stuart Ripley, Stephen Bell, Gary Gill, Phil Stamp, Tommy Mooney, Keith Houchen, Graeme Lee, Jonathan Woodgate, Stewart Downing, Matt Jarvis, Dael Fry , Jordan Hugill and Ben Gibson

- Middlesbrough Football Club Chairman Steve Gibson

- Head of Vehicle Performance WilliamsF1[60] Rob Smedley

- Rugby union players Rory Underwood and Alan Old

- Cricketers Liam Plunkett, Geoff Cook, Bill Athey, Matt Renshaw and Chris Old

- Boxers Paul Truscott and Commonwealth gold medal champion Simon Vallily

- Table tennis player Paul Drinkhall

- Darts players Glenn Moody, Colin Osborne and Glen Durrant

- Billiards player Mike Russell

- Olympic swimmers Jack Hatfield and Aimee Willmott

- Commonwealth Games swimmer Alyson Jones

- Olympic cyclist Chris Newton

- Three times Olympian and former British long jump record holding athlete Chris Tomlinson

- Former Premiership referee Jeff Winter

- Former Junior World and European Track Cycling Champion David Daniell

- The Football Association's former Director of Communications Adrian Bevington

- Paralympic Athlete Jade Jones

- Olympic Bobsledder John Baines

- Olympic table tennis player Paul Drinkhall

- WPC World Powerlifting Champion Dave Pennington

The arts

- Models Jade McSorley and Preeti Desai, who was Miss Great Britain 2006

- Comedians Dave Morris, Bob Mortimer,[61] Roy Chubby Brown and Kevin Connelly

- Musicians Ron Aspery, Cyril Smith, Chris Rea,[62] Paul Rodgers, Micky Moody, Alistair Griffin, Vin Garbutt, Chris Corner, Bruce Thomas, James Arthur and Pete Trewavas

- Actors Thelma Barlow, Marcus Bentley, Mark Benton, Sean Blowers, Elizabeth Carling, Alethea Charlton, Preeti Desai, Jerry Desmonde, Monica Dolan, Neil Grainger, Lila Kaye, Faye Marsay, Christopher Quinten, Wendy Richard, John Telfer and Jamie Parker.

- Writers Ann Jellicoe, Richard Milward and Wally K Daly

- Visual artists Fred Appleyard, Robert Nixon, Mackenzie Thorpe, Chris Dooks, William Tillyer and Richard Piers Rayner

- Author, educator, historian and lecturer Paul C. Doherty

- Roman Catholic and Dominican priest, theologian and philosopher Herbert McCabe[63]

- Antiques expert David Harper

- Wagnerian soprano at the New York Met Florence Easton

- Theatre actor Dean John-Wilson

Other entertainers

- Magicians Martin Daniels, Paul Daniels and Pete Firman

- TV presenter Kirsten O'Brien,[64] Kay Murray

- Radio presenter Ali Brownlee

- Magician/comedian John Archer

- Singer Marion Ryan

Other eminent sons and daughters of Middlesbrough and its environs include Sir Martin Narey (1955–present), former Director General of the Prison Service and chief executive of Barnardo's, Professor Sir Liam Donaldson,[65] Chief Medical Officer for England, E. W. Hornung, the creator of the gentleman-crook Raffles (who was fluent in three Yorkshire dialects), and Naomi Jacob novelist. Cyril Smith (1909–74), the concert pianist. Two immigrant sons – Frank and Edgar Watts – opened the English Hotel in the Cumberland Gap which gave their hometown's name to Middlesboro, Kentucky, in the United States.[68] The classic study, At The Works (1907), by Florence Bell (1851–1930), gives a picture of the area at the turn of the 20th century. She also edited the letters of her stepdaughter Gertrude Bell (1868–1926), which has been continuously in print since 1927. Pat Barker's debut novel Union Street was set on the thoroughfare of the same name in the town. The Jonny Briggs series of books, written by Joan Eadington and later to become a BBC Children's TV series of the same name, was also based in the town. David Shayler, the ex-spy, journalist and conspiracy theorist, was born in Middlesbrough.[69]

Ford Madox Ford (1873–1939) was billeted in Eston during the Great War (1914–18), and his great novel sequence Parade's End is partly set in Busby Hall, Little Busby, near Carlton-in-Cleveland.

Adrian "Six Medals" Warburton, air photographer, was played by Alec Guinness in Malta Story.

The great model maker Richard Old (1856–1932) resided for most of his life at 6 Ruby Street.

Image gallery

-

Teesside Crown Court

-

The CIAC Building at RiversideOne, Middlehaven

-

40,000 Years of Modern Art, at Middlehaven by Benedict Carpenter

-

The Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, circa 2007

-

Panoramic view of Middlesbrough

Twin towns

Middlesbrough is twinned with:

Middlesboro, Kentucky, USA[citation needed]

Middlesboro, Kentucky, USA[citation needed] Masvingo, Zimbabwe, since 1990[citation needed]

Masvingo, Zimbabwe, since 1990[citation needed] Oberhausen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, since 1974[70]

Oberhausen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, since 1974[70] Dunkirk, Nord, Hauts-de-France, France[71]

Dunkirk, Nord, Hauts-de-France, France[71]

See also

- A66 road

- Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI)

- Middlesbrough Music Live

- Northeast of England Process Industry Cluster (NEPIC)

- Parmo

- River Tees

- Teesport

- Teesside University

References

- ^ "Exhibition charts post-industrial areas". The Northern Echo. Newsquest (North East) Ltd. 15 May 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ "Postindustrial society: Written By: Robert C. Robinson". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ "Central Middlesbrough". The Gazette. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Area: Middlesbrough settlement (Built-up area subdivision) 2011 Census: Usual Resident Population". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Area: Teesside (Built-up Area) Official Labour Market Statistics 2011 Census: Usual Resident Population". United Kingdom Census 2011. Nomis Official Labour Market Statistics. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Middlesbrough Borough Council". Civic Heraldry of England and Wales.

- ^ "Welcome to Middlesbrough". Archived from the original on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Moorsom, Norman (1983). Middlesbrough as it was. Hendon Publishing Co Ltd.

- ^ "Stainsby Medieval Village". Tees Archaeology. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Middlesbrough". Billy Scarrow. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "Middlesbrough and surrounds: The Birth of Middlesbrough". England's North East. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Middlesbrough and surrounds: The Birth of Middlesbrough". englandsnortheast. David Simpson. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d Delplanque, Paul (17 November 2011). "Middlesbrough Dock 1839–1980". Evening Gazette. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "The Archives: History of Middlehaven". Middlesbrough College. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ "December 1861 map of Middlesbrough North Riding: A Vision of Britain Through Time". University of Portsmouth and others. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ "Middlesbrough has sometimes been designated the Ironopolis of the North". The Northern Echo. 23 February 1870.

- ^ "Middlesbrough never ceased to be Ironopolis". Journal of Social History. 37 (3): 746. Spring 2004.

- ^ "History of Cleveland Police". Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "Dorman Long Historical Information". dormanlongtechnology.com. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ Fennell, Barbara; Jones, Mark J; Llamas, Carmen. "Middlesbrough - A study into Irish immigration and influence on the Middlesbrough dialect".

- ^ a b Yasumoto, Minoru (2011). The Rise of a Victorian Ironopolis: Middlesbrough and Regional Industrialization.

- ^ Swift, Roger; Gilley, Sheridan (1989). The Irish in Britain, 1815–1939.

- ^ "Teesport". ports.org.uk.

- ^ "Remembering the Blitz". Evening Gazette. Trinity Mirror. September 2010.

- ^ "Middlesbrough Railway Station bombed 1942". Evening Gazette. Trinity Mirror. April 2010.

- ^ "Middlesbrough 1940's". Billmilner.250x.com. 4 August 1942. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Middlesbrough Parish information from Bulmers' 1890". GENUKI. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ Youngs, Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England, Volume 2

- ^ "Dave Budd replaces Ray Mallon as Middlesbrough mayor". BBC News. 8 May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ "Bolckow, Henry". Appletons' Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events. Vol. 18. 1886. p. 650.

William Ferdinand, a British manufacturer, born in Germany in 1806, died 18 June 1878. ... He was the first Mayor of Middlesbrough, a place which owes much of its prosperity to his energy and enterprise

- ^ Up The Boro!. 2011. p. 9.

This was followed in 1868 by Middlesbrough's first Parliamentary Elections, in which Henry Bolckow (1806–1878) of the firm Bolckow & Vaughan wanted to stand for election, however this was initially blocked by the fact that he was a foreigner ...

- ^ "Middlesbrough Climate Period: 1981–2010, Stockton-on-Tees Climate Station". Met Office. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "Middlesbrough Climate Period: 1981–2010, Stockton-on-Tees Climate Station". Met Office. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ "Middlesbrough Council:Listed Buildings Overview". Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Middlesbrough Council:PDF of Listed Buildings". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Boro lift Carling Cup". BBC Sport. 29 February 2004. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- ^ "Sevilla end 58-year wait". UEFA. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- ^ Proud, Keith (18 August 2008). "The player with the Common touch". The Northern Echo. Newsquest. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Middlesbrough Sports Village: Athletes hail £21m facility ahead of open weekend". The Gazette. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ Middlesbrough Council "runmiddlesbrough" website. "Middlesbrough 10k road race". Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ Chase, Malcolm (Spring 2007). "Leeds in Linthorpe". Cleveland History, Bulletin of the Cleveland and Teesside Local History Society (92): 5.

- ^ Emily Diamand Workshops. "Trinity Catholic College website". Trinitycatholiccollege.middlesbrough.sch.uk. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ "Ofsted Macmillan Academy". Ofsted. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Custom report - Nomis - Official Labour Market Statistics". www.nomisweb.co.uk.

- ^ "Custom report - Nomis - Official Labour Market Statistics". www.nomisweb.co.uk.

- ^ Hughes, A., Turdgill, P., Watt, D. English Accents & Dialects.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Beal, J., Carmen, L. Urban North-Eastern English: Tyneside to Teesside. Edinburgh University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Watt and Llamas 2004. British Isles Accents and Dialects.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Evangelical Connexion". Ec-fce.org.uk. 2 June 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ^ a b "Middlesbrough Hebrew Congregation & Jewish Community". Jewish Communities & Records. 2 January 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Visit Middlesbrough – The Middlesbrough Faith Trail: Muslims in Middlesbrough" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ^ "Abu Bakr Mosque, Middlesbrough". Abubakr.org.uk. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ^ a b "Tees Transporter Bridge And Visitor Centre". Love Middlesbrough.

- ^ "The Blade Runner Connection". BBC Online.

- ^ "Top Gear stars in Middlesbrough visit". Evening Gazette. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ^ "No surgeries for 14 years - is Sir Stuart Bell Britain's laziest MP?". The Independent. 8 September 2011.

- ^ Moss, Richard (9 September 2011). "Sir Stuart Bell - the laziest MP?". BBC News.

- ^ "Are Teessiders getting enough from Sir Stuart Bell?". gazettelive.co.uk. 6 September 2011.

- ^ "The full story of Teesside D-Day hero Stan Hollis". Evening Gazette. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ "Smedley finally makes Williams switch as Head of Vehicle Performance". James Allen on F1 – The official James Allen website on F1.

- ^ Pain, Andrew (13 May 2013). "Bob Mortimer on growing up on Teesside and North-east comedy". Evening Gazette. Trinity Mirror.

- ^ Smiles, Mieka (5 November 2014). "Chris Rea opens up about his cancer battle and growing up in his native Middlesbrough". gazettelive.co.uk.

- ^ "Herbert McCabe". The Daily Telegraph. London. 20 August 2001.

- ^ Ford, Coreena (8 October 2011). "Baby joy for Middlesbrough star Kirsten O'Brien". Evening Chronicle. Trinity Mirror.

- ^ "The Birmingham Magazine" (PDF). Edgbaston: University of Birmingham. September 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rennick, Robert (1987). Kentucky Place Names. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. p. 196. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ McNeil, JR (2000). The Ralston Family: Through Eight Generations, with Ratcliffe, Johnson, and Allied Families. p. 119.

- ^ Rennick details the importance of the hotel but mistakenly ascribes it to a "Mr. Watts"[66] when in fact it was two brothers involved with Alexander Arthur's development plans.[67]

- ^ "David Shayler". The Gazette. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Town Twinning". Middlesbrough Council. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- Bell, Lady Florence. At the Works, a Study of a Manufacturing Town (1907) online.

- Briggs, Asa. Victorian Cities (1965) pp 245–82.

- Doyle, Barry. "Labour and hospitals in urban Yorkshire: Middlesbrough, Leeds and Sheffield, 1919–1938." Social history of medicine (2010): hkq007.

- Glass, Ruth. The social background of a plan: a study of Middlesbrough (1948)

External links

Middlesbrough travel guide from Wikivoyage

Middlesbrough travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Template:Dmoz

- Sunrise and sunset times

- Tide times at BBC, Admiralty Easytide and Tidetimes

- "Pioneers of the Cleveland iron trade" by J. S. Jeans 1875

- "At the works, a study of a manufacturing town (Middlesbrough, Yorkshire)" by Florence Bell, 1907* BBC Tees – the latest local news, sport, entertainment, features, faith, travel and weather.

- Genuki – History of Eston parish & District Descriptions from Bulmer's History and Directory of North Yorkshire (1890)

- 1830 establishments in England

- Areas within Middlesbrough

- Articles including recorded pronunciations (UK English)

- Local government districts of North East England

- Middlesbrough

- People from Middlesbrough

- Places in the Tees Valley

- Populated places established in 1830

- Port cities and towns of the North Sea

- Ports and harbours of Yorkshire

- Towns in North Yorkshire

- Towns with cathedrals in the United Kingdom

- Unitary authority districts of England

- University towns in the United Kingdom