Varagavank

| Varagavank | |

|---|---|

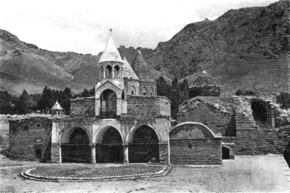

The monastery c. 1913[1] | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Armenian Apostolic Church |

| Status | several buildings destroyed, continuous deterioration of others |

| Location | |

| Location | Yukarı Bakraçlı,[2][3] Van Province, Turkey |

| Geographic coordinates | 38°26′59″N 43°27′39″E / 38.449636°N 43.460825°E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Armenian |

| Founder | Senekerim-Hovhannes Artsruni |

| Groundbreaking | early 11th century |

Varagavank (Armenian: Վարագավանք, 'Monastery of Varag';[A] Turkish: Yedi Kilise, 'Seven Churches') was an Armenian monastery on the slopes of Mount Erek, 9 km (5.6 mi) southeast of the city of Van, in eastern Turkey.

The monastery was founded in the early 11th century by Senekerim-Hovhannes Artsruni, the Armenian King of Vaspurakan, on a preexisting religious site. Initially serving as the necropolis of the Artsruni kings, it eventually became the seat of the archbishop of the Armenian Church in Van.[5] The monastery has been described as one of the great monastic centers of the Armenian church by Ara Sarafian and the richest and most celebrated monastery of the Lake Van area by Robert H. Hewsen.

During the Armenian genocide, in April–May 1915, the Turkish army attacked, burned, and destroyed much of the monastery. More of it was destroyed in the 1960s, although some sections are still extant.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

According to tradition, in the late third century, Saint Hripsime hid the remnant of the True Cross she wore on her neck at the site of the monastery. In 653, when the location was discovered, Catholicos Nerses III the Builder built the Church of Surb Nshan (Holy Sign),[6] described by Robert H. Hewsen as "a simple hermitage".[7] Catholicos Nerses also established the Feast of the Holy Cross of Varag (Varaga surb khachi ton), celebrated by the Armenian Apostolic Church on the Sunday nearest to 28 September, always two weeks after the Feast of the Cross.[8]

Queen Khushush, the daughter of King Gagik I of Armenia and spouse of Senekerim-Hovhannes Artsruni, the future Artsruni King of Vaspurakan, built a church at the site in 981 dedicated to the Holy Wisdom (Surb Sopi).[7] In the late medieval period, it was converted into a castle and was known as Berdavor (berd means 'fortress' in Armenian). The Church of Surb Hovhannes (Saint John) was built to the north in the 10th century.[6]

Foundation and medieval period

[edit]The monastery itself was founded by Senekerim-Hovhannes early in his reign (1003–24) to house a relic of the True Cross that had been kept on the site since Hripsime.[7][10] In 1021, when Vaspurakan fell to Byzantine rule, Senekerim-Hovhannes took the relic to Sebastia, where the following year his son Atom founded the Surb Nshan Monastery. In 1025, following his death, Senekerim-Hovhannes was buried at Varagavank and the True Cross was returned to the monastery.[6] Fearing an attack by Muslims, Father Ghukas of Varagavank took the True Cross in 1237 to the Tavush region of northeastern Armenia. There he settled in the Anapat monastery, which was renamed Nor Varagavank. In 1318, the Mongols invaded the region and ransacked the monastery. All the churches were destroyed except St. Hovhannes, which had an iron door and was where the monks hid. Between 1320 and the 1350s, the monastery was completely restored.[6]

Modern period

[edit]The Safavid emperor Tahmasp I ransacked the monastery in 1534. In 1648, along with other buildings in the region, Varagavank was destroyed by an earthquake. Its restoration was begun immediately thereafter by monastery father Kirakos who found financial support among the wealthy merchants in Van. According to the 17th-century historian Arakel of Tabriz, four churches were restored and renovated.[6]

The architect Tiratur built a square-planned gavit (narthex) west of Church of Surb Astvatsatsin (Holy Mother of God) in 1648. It functioned as a church during the 19th century, called Surb Gevorg. To the west of the narthex was a 17th-century three-arched open-air porch; to the north was Church of Surb Khach (Holy Cross); while to the south was the 17th-century Church of Surb Sion. Urartian cuneiform inscriptions were used as lintels on their western entrances.[6]

Suleyman, the prince of Hoşap Castle, invaded the monastery in 1651, looting its Holy Cross, manuscripts, and treasures. The cross was later repurchased, and it was taken to the Tiramayr Church of Van in 1655. The monastery declined in the late 17th century and, in 1679, many of its treasures were sold due to economic difficulties. Archbishop Bardughimeos Shushanetsi renovated the monastery in 1724.[6]

In 1779, father Baghdasar vardapet decorated the narthex walls with frescoes of King Abgar V, Theodosius I, Saint Gayane, Hripsime, Khosrovidukht, and Gabriel. According to Murad Hasratyan, the unknown painter had fused together the styles of Armenian, Persian, and Western European art.[6]

19th century

[edit]A wall was built around the monastery in 1803 and, fourteen years later, the Church of Surb Khach (Holy Cross) was completely renovated and converted into a depository of manuscripts by archbishop Galust. In 1832, Tamur Pasha of Van robbed the monastery's treasures and strangled the father Mktrich vardapet Gaghatatsi to death. In 1849, Gabriel vardapet Shiroyan restored the Church of Sion, which had been destroyed by an earthquake, and converted it into a wheat warehouse.[6]

Mkrtich Khrimian, the future head of the Armenian Church, became father of Varagavank in 1857 and made the monastery effectively independent and subordinate only to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople.[6] He founded a printing house and began publishing Artsvi Vaspurakan (Eagle of Vaspurakan), the first newspaper in historical Armenia,[7] which was published between 1858 and 1864.[6] He also established a modern school. The school taught subjects such as theology, music, grammar, geography, Armenian studies and history; the prominent novelist Raffi was briefly one of the teachers. The school produced its first graduates in 1862.[6]

During the Hamidian massacres of 1896, the monastery was sacked[11] and robbed. Some teachers and students were killed.[6] According to a contemporary report by an American at Van, "Varak, the most famous and historic monastery in all this [Van] region, which has weathered the storms of centuries is almost certain to go [on fire]."[12]

Sacking and abandonment

[edit]On 20 April 1915, some 30 gendarmes arrived at Varagavank and murdered the monastery's two monks together with four of their servants. The monastery remained under their occupation until 30 April, when, for unknown reasons, the gendarmes withdrew and returned to Van city. This withdrawal coincided with the arrival on Varag mountain of some 3000 Armenian refugees from the Hayatzor valley who had escaped the massacres that had taken place there several days earlier. They were soon joined by some 3000 survivors of massacres elsewhere, and together they found a temporary refuge in the Armenian villages and monasteries on the mountain, including Varagavank. Self-defense units were also set up in an attempt to protect the villages; about 250 men, almost half the force, was stationed at Varag, with most of the remainder based at nearby Shushants monastery. On the order of Van's governor, Djevdet Bey, Turkish forces returned in strength, with 300 calvarymen, 1000 militia, and three batteries of artillery. According to historian Raymond Kévorkian, this was on 8 May. Shushants quickly fell after putting up a feeble defense and was burnt down. Varagavank fell shortly afterwards and was also burnt. The majority of the villagers and the refugees managed to escape to Van at night. The Turkish forces made no attempt to stop them entering the Armenian-controlled sectors of the city; it is speculated that they were deliberately allowed in so that they would use up the limited food supplies of the defenders.[13][14][15]

The exact date of the burning of the monastery is not known for certain. On 27 April 1915, a message sent "To Americans, or any Foreign Consul" by Clarence Ussher and Ernest Yarrow, American missionaries in Van, said that "From our window we could plainly see Shushantz afire on its mountain-side and Varak Monastery, with its priceless store of ancient manuscripts, going up in smoke."[16] However, a fellow missionary, Elizabeth Barrows Ussher, Clarence Ussher's wife, wrote in her diary that the monastery was attacked by 200 cavalry and foot soldiers on 30 April, but they were repulsed. She gave 4 May as the day the monastery was burned.[17] Another missionary teacher, Grace H. Knapp, recounted, however, that "On the 8th May we saw the place in flames, and Varak Monastery near by, with its priceless ancient manuscripts, also went up in smoke."[18][19]

Current state

[edit]

A significant number of the structures surviving the 1915 destruction were destroyed in the 1960s.[20] As of 2006, the monastery's remains were used as a barn.[21] According to historian Ara Sarafian, as of 2012, "good sections have just barely survived until our days."[20] Dr. Jenny B. White, a scholar on Turkey, wrote in 2013 that, on her visit, the remains of the monastery "consisted of nothing more than a few brick vaults used to house goats amid a clutch of tumbledown Kurdish homes."[22] The best-preserved section of the monastery is the church of Surb Gevorg (St. George),[23] which is now looked after by a caretaker.[24] The dome is partly collapsed and contains some traces of surviving frescoes.[24] The dome of the church of Surb Nshan is entirely gone.[25]

In February 2010, following the renovation of the Holy Cross Cathedral at Akdamar Island in Lake Van, Halil Berk, the Deputy Governor of Van Province, announced that the Governor's Office sought to restore Varagavank and the Ktuts monastery at Çarpanak Island.[2] In June of that year, the governor also stated that the monastery at Çarpanak Island and Varagavank would be renovated "in the near future."[26] In October 2010, Radikal reported that a nearby mosque, built in 1997, would be demolished to make room for the restoration of Varagavank.[3]

The monastery was damaged as a result of the 2011 Van earthquake.[27][28] According to Ara Sarafian, "parts of the main church collapsed, while other parts were significantly weakened. Old cracks got bigger, new ones appeared." Turkish engineers reportedly inspected it and announced that they would commence restoration work in the spring of 2012. Sarafian wrote that "such promises have been made in the past and one needs to be a little skeptical. The current state of the church makes such work much harder than at any time in the past." He noted in a 2012 article that the local and provincial governments supported the preservation and restoration of the monastery.[20] In October 2012, the artist Raffi Bedrosyan, who contributed to the restoration of the St. Giragos Church in Diyarbakır, stated that he had hoped to restore Varagavank and added that "Both Ankara and Van agreed to launch the restoration project, but social and natural obstacles delayed the process.".[29] In 2017 it was documented that the remaining stones of the monastery are regularly taken off by the local authorities to build a local mosque and other developments with them.[30]

Ownership

[edit]Taraf reported in September 2012 that the monastery is owned by the Turkish journalist and media executive Fatih Altaylı. In an interview, Altaylı told the newspaper that the monastery belonged to his grandfather and he inherited it from his father.[31][32] The monastery was confiscated during the Armenian genocide.[33] A group of Armenians in Turkey, led by the activist Nadya Uygun, started a petition asking him to "Apply to the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey and transfer the title deed of the church to the concerned [Armenian community] foundation."[34] Altayli told Agos that he is ready to give it to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople,[35] but no government authority has approached him to respond to his offer to give back the church to its owners, and that they displayed no interest in cooperating.[34] Revolutionary Socialist Workers' Party (DSİP) activists demonstrated in early October 2012 before the Habertürk headquarters in Beyoğlu, Istanbul demanding the return of the monastery land to the Armenians.[36][37] As of September 2014, there was no progress.[34]

Architecture

[edit]

The monastery was composed of six churches, a gavit (narthex) and other structures.[39] The main church of Varagavank was called Surb Astvatsatsin (Holy Mother of God). It dated to the 11th century and was similar in plan to the prominent Saint Hripsime Church in Vagharshapat.[6] The earliest structure was on the southern part of the ensemble and was known as Surb Sopia (10th century). Queen Khushush left an inscription (dated 981) on its western wall.[39]

Manuscripts

[edit]In the 10th century, Queen Mlke, the wife of Gagik I, presented the monastery with the "Gospel of Queen Mlke", one of the best known Armenian illuminated manuscripts. In the 14th–16th centuries the monastery became a major center of manuscript production. A number of Varagavank manuscripts are now kept at the Matenadaran repository in Yerevan.[6]

Cultural references

[edit]Raffi mentions the monastery in volume two of the novel Sparks (Kaytser, 1883–87).[40] The prominent poet Hovhannes Tumanyan wrote an article about the monastery in 1910, belatedly celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of Mkrtich Khrimian becoming father of Varag and the monastery's subsequent revival as a great center of education and culture.[41]

European visitors

[edit]- Austen Henry Layard (1853): "...the large Armenian convent of Yedi Klissia, or the seven churches, built of substantial stone masonry, and inclosing a spacious courtyard planted with trees. [...] The church, a substantial modern edifice, stand within the courtyard. Its walls are covered with pictyres as primitive in design as in execution."[42]

- Henry Fanshawe Tozer (1881): "...the broken Varak Dagh formed a noble object on the further side of the plain. In one of the upper valleys of the last-named mountain lies an important monastery, which is the residence of the archbishop, and has a good school."[43]

- H. F. B. Lynch (1893): "The monastery of Yed Kilisa, situated on the slopes of that mountain, is the most frequented of the numerous cloisters in the neighbourhood..."[9]

Gallery

[edit]-

Entrance in 2013

-

Gavit in 2013

-

Main church in 2013

-

Apse from church 1, 2009

-

Varagavank, ornament, 2011

-

Varagavank, fresco, 2011

-

Varagavank, fresco, 2011

-

Varagavank, ornament, 2011

-

Varagavank, ornament, 2011

-

Taken from the roof of Varagavank, 2013

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

-

Van Yedi Kilise aka Varagavank

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Sometimes spelled separately as two words: Varaga vank, Վարագայ վանք in classical spelling[4] and Վարագա վանք in reformed spelling. Pronounced Varakavank' in Western Armenian.

- ^ Bachmann 1913, p. 133.

- ^ a b "More Armenian churches to be renovated in eastern Turkey". Hürriyet Daily News. via Anatolia News Agency. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 5 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Ermeni kilisesi için geri sayım". Radikal (in Turkish). 27 October 2010. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- ^ "Թուրքերը Կ՛առաջարկեն Քանդել Վարագայ Վանքի Կողքի Մզկիթը". Asbarez (in Armenian). 30 November 2009. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014.

- ^ Minasian, T. H. "Գրիգոր Սկևռացու գրական ժառանգության հարցի շուրջ [To the Question of Grigor Skevratsi's Literary Heritage]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian) (2). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences: 98. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014.

Վարագա վանքը Վասպուրականի նշանավոր հոգևոր կենտրոններից էր: Այն եղել է եպիսկոպոսանիստ, վանքի վանահայրերը եղել են Վան քաղաքի և շրջակա միջավայրի առաջնորդներ:

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hasratyan, Murad (2002). "Վարագավանք [Varagavank]". Yerevan State University Institute for Armenian Studies (in Armenian). "Christian Armenia" Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d Hewsen, Robert H. (2000). "Van in This World; Paradise in the Next: The Historical Geography of Van/Vaspurakan". In Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.). Armenian Van/Vaspurakan. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 1-56859-130-6.

- ^ Divan of the Diocese (23 September 2011). "Feast of the Holy Cross of Varak". Burbank, California: Western Diocese of the Armenian Church. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014.

- ^ a b Lynch, H. F. B. (1901). "Van". Armenia, travels and studies. Vol. 2: The Turkish Provinces. Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. 113–115.

- ^ Sinclair, T. A. (1989). "Yedi Kilise (Armn. "Varagavank")". Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume I. London: Pindar Press. pp. 190–192. ISBN 978-1-904597-70-4.

- ^ Guréghian, Jean V. (2008). Les monuments de la région Mouch-Sassoun-Van en Arménie historique [The monuments of the regions of Mush-Sasun-Van in historical Armenia] (in French). Alfortville: Sigest. p. 16. ISBN 978-2-917329-06-1.

- ^ "Weekly--Continuing Christian at Work". Christian Work: Illustrated Family Newspaper. 61 (1, 537). New York: 166. 30 July 1896.

- ^ Kévorkian, Raymond H. (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 325–326. ISBN 978-1-84885-561-8.

- ^ Walker, Christopher J. (1990). Armenia: The Survival of a Nation (revised second ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-312-04230-1.

Their five-week battle with the Turks was not a rebellion, but legitimate self-defence, a reaction to the terrorism of the government's representative, Djevdet, which he had directed against the entire Armenian community.

- ^ Mayersen, Deborah (2014). On the Path to Genocide: Armenia and Rwanda Reexamined. New York: Berghahn Books. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-78238-285-0.

The events at Van described earlier constitute the most notable case of Armenian resistance.

- ^ Ussher, Clarence (1917). An American Physician in Turkey: A Narrative of Adventures in Peace and War. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 275.

- ^ Barrows, John Otis (1916). In the Land of Ararat. Fleming H. Revell Company. p. 133 "April 30th. A party of 200 cavalry and foot soldiers attacked Varak and Shushantz villages, but were repulsed."; p. 136 "[May 5th.] The older, a girl about five or six, had carried her two-year-old brother on her back from the Varak monastery, which had been a refuge for 2000 villagers before the Turks burnt it up yesterday morning. [i.e. May 4th]"

- ^ Knapp, Grace Higley (1916). The Mission at Van: In Turkey in War Time. Privately Printed. p. 22.

- ^ Toynbee, Arnold, ed. (1916). "The American Mission at Van: Narrative printed privately in the United States by Grace Higley Knapp (1915).". The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915–1916: Documents Presented to Viscount Grey of Fallodon by Viscount Bryce, with a Preface by Viscount Bryce. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 38.

- ^ a b c Sarafian, Ara (22 January 2012). "A Time to Act: What will become of Varak Monastery after the recent earthquake in Van?". The Armenian Reporter. Archived from the original on 5 October 2014.

- ^ Bevan, Robert (2006). "Cultural Cleansing: Who Remembers the Armenians ?". The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. London: Reaktion Books. p. 57. ISBN 1-86189-205-5.

Elsewhere some remains cling on, including the tenth-century chapel frescos at Varak Vank, now a barn.

- ^ White, Jenny (2014). Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-4008-5125-6.

- ^ "Yedi Kilise". The Rough Guide to Turkey. Rough Guides. 2003. p. 941.

- ^ a b "The Armenian Churches of Lake Van". Today's Zaman. 14 July 2009. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- ^ Ekmanian, Harout (30 September 2010). "Detailed Report: The Mass in Akhtamar, and What's Next". Armenian Weekly. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020.

- ^ Ziflioğlu, Vercihan (19 June 2010). "Akdamar Surp Haç Church in Turkey to host service, but remain museum". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014.

- ^ "Turkey Earthquake Delivers Further Blow to Varakavank Armenian Monastery in Van". epress.am. 31 October 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- ^ "Տխուր պատմություն Վարագավանքից". nt.am (in Armenian). Noyan Tapan. 2 June 2012. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019.

Այս անգամ այցելությունը Վարագա վանք շատ տխուր էր, որովհետեւ Վանի երկրաշարժից փլվել էր վանքի մի մասը եւ փակել մուտքը:

- ^ Ziflioğlu, Vercihan (18 October 2012). "Bell to toll once more at Diyarbakır church". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014.

- ^ "Stones of Armenian church used in mosque construction". Public Radio of Armenia. 8 August 2017. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019.

- ^ Tansel, Sümeyra (22 September 2012). "Ne olacak Fatih'in kilisesinin bu hali". Taraf (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- ^ Güsten, Susanne (20 April 2015). "Restitution of Armenian property remains unresolved". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Որտեղի՞ց հայկական եկեղեցի Haberturk-ի գլխավոր խմբագրին". CivilNet (in Armenian). 26 September 2012. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Gunaysu, Ayse; Uygun, Nadya (24 September 2014). "Fatih Altayli: Male Chauvinist, Owner of Usurped Armenian Property". Armenian Weekly. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020.

- ^ Koptaş, Rober. "Manastırı seve seve veririm". Agos (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Tansel, Sümeyra (3 October 2012). "Altaylı kiliseyi geri verecek". Taraf (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- ^ "DSİP, Fatih Altaylı'dan Ermeni kilisesini geri istedi". Agos (in Turkish). 2 October 2012. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021.

- ^ Bachmann 1913, p. 131.

- ^ a b Hasratyan, Murad (1985). "Վարագավանք [Varagavank]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia. pp. 304–305.

- ^ Raffi (1887). Կայծեր [Sparks] (PDF). p. 46.

...երևում էին և Վարագա կանաչազարդ լեռները, որոնց կուրծքի վրա, խորին ջերմեռանդությամբ գրկված, բազմել էր Վարագա գեղեցիկ վանքը:

- ^ Tumanyan, Hovhannes (11 June 1910). "Վարագա հոբելյանը (Anniversary of Varag)". Horizon (in Armenian). No. 126. Tiflis: Armenian Revolutionary Federation. Reproduced in Հովհաննես Թումանյան Երկերի Լիակատար Ժողովածու. Հատոր Վեցերորդ. Քննադատություն և Հրապարակախոսություն 1887-1912 [Anthology of Hovhannes Tumanyan Volume 6: Criticism and Oration 1887-1912] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian National Academy of Sciences. 1994. pp. 219–220.

- ^ Layard, Austen Henry (1853). Discoveries in the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon; with travels in Armenia, Kurdistan and the desert: being the result of a second expedition undertaken for the Trustees of the British museum. London: John Murray. p. 409.

- ^ Tozer, Henry Fanshawe (1881). Turkish Armenia and Eastern Asia Minor. London: Longmans, Green & Co. pp. 349–350.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bachmann, Walter [in German] (1913). Kirchen und moscheen in Armenien und Kurdistan [Churches and mosques in Armenia and Kurdistan]. 25. Wissenschaftliche veröffenlichung der Deutschen Orient-gesellschaft. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

External links

[edit]- Gallery at PanARMENIAN.Net by Sedrak Mkrtchyan

- "Varagavank' Monastery". Rensselaer Digital Collections. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

- The Monastery of Varagavank at Virtual Ani

- Gagik Arzumanyan's photo gallery

- Armenian Monastery of Varagavank at The Land of Crying Stones (Recent pictures of the ruins)

- Varak by Raffi