Schindler's List

| Schindler's List | |

|---|---|

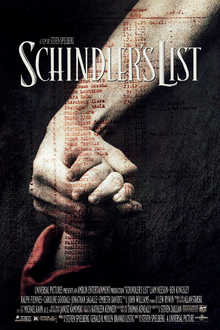

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Screenplay by | Steven Zaillian |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński |

| Edited by | Michael Kahn |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 197 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $22 million[2] |

| Box office | $321.2 million[3] |

Schindler's List is a 1993 American epic historical period drama film, directed and co-produced by Steven Spielberg and scripted by Steven Zaillian. It is based on the novel Schindler's Ark by Australian novelist, Thomas Keneally. The film relates a period in the life of Oskar Schindler, an ethnic German businessman, during which he saved the lives of more than a thousand mostly Polish-Jewish refugees from the Holocaust by employing them in his factories. It stars Liam Neeson as Schindler, Ralph Fiennes as Schutzstaffel (SS) officer Amon Göth, and Ben Kingsley as Schindler's Jewish accountant Itzhak Stern.

Ideas for a film about the Schindlerjuden (Schindler Jews) were proposed as early as 1963. Poldek Pfefferberg, one of the Schindlerjuden, made it his life's mission to tell the story of Schindler. Spielberg became interested in the story when executive Sid Sheinberg sent him a book review of Schindler's Ark. Universal Studios bought the rights to the novel, but Spielberg, unsure if he was ready to make a film about the Holocaust, tried to pass the project to several other directors before finally deciding to direct the film himself.

Principal photography took place in Kraków, Poland, over the course of 72 days in 1993. Spielberg shot the film in black and white and approached it as a documentary. Cinematographer Janusz Kamiński wanted to give the film a sense of timelessness. John Williams composed the score, and violinist Itzhak Perlman performs the film's main theme.

Schindler's List premiered on November 30, 1993, in Washington, D.C. and it was released on December 15, 1993, in the United States. Often listed among the greatest films ever made,[4][5][6] it was also a box office success, earning $321.2 million worldwide on a $22 million budget. It was the recipient of seven Academy Awards (out of twelve nominations), including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Original Score, as well as numerous other awards (including seven BAFTAs and three Golden Globes). In 2007, the American Film Institute ranked the film 8th on its list of the 100 best American films of all time. The Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2004.

Plot

In Kraków during World War II, the Germans had forced local Polish Jews into the overcrowded Kraków Ghetto. Oskar Schindler, an ethnic German, arrives in the city hoping to make his fortune. A member of the Nazi Party, Schindler lavishes bribes on Wehrmacht (German armed forces) and SS officials and acquires a factory to produce enamelware. To help him run the business, Schindler enlists the aid of Itzhak Stern, a local Jewish official who has contacts with black marketeers and the Jewish business community. Stern helps Schindler arrange financing for the factory. Schindler maintains friendly relations with the Nazis and enjoys wealth and status as "Herr Direktor", and Stern handles administration. Schindler hires Jewish workers because they cost less, while Stern ensures that as many people as possible are deemed essential to the German war effort, which saves them from being transported to concentration camps or killed.

SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) Amon Göth arrives in Kraków to oversee construction of Płaszów concentration camp. When the camp is completed, he orders the ghetto liquidated. Many people are shot and killed in the process of emptying the ghetto. Schindler witnesses the massacre and is profoundly affected. He particularly notices a tiny girl in a red coat – one of the few splashes of color in the black-and-white film – as she hides from the Nazis, and later sees her body (identifiable by the red coat) among those on a wagon load of corpses. Schindler is careful to maintain his friendship with Göth and, through bribery and lavish gifts, continues to enjoy SS support. Göth brutally mistreats his Jewish maid Helen Hirsch and randomly shoots people from the balcony of his villa, and the prisoners are in constant fear for their lives. As time passes, Schindler's focus shifts from making money to trying to save as many lives as possible. To better protect his workers, Schindler bribes Göth into allowing him to build a sub-camp.

As the Germans begin to lose the war, Göth is ordered to ship the remaining Jews at Płaszów to Auschwitz concentration camp. Schindler asks Göth to allow him to move his workers to a new munitions factory he plans to build in his home town of Zwittau-Brinnlitz. Göth agrees, but charges a huge bribe. Schindler and Stern create "Schindler's List" – a list of people to be transferred to Brinnlitz and thus saved from transport to Auschwitz.

The train carrying the women and children is accidentally redirected to Auschwitz-Birkenau; Schindler bribes Rudolf Höss, the commandant of Auschwitz, with a bag of diamonds to win their release. At the new factory, Schindler forbids the SS guards to enter the production rooms and encourages the Jews to observe the Jewish Sabbath. He spends much of his fortune bribing Nazi officials and buying shell casings from other companies; his factory does not produce any usable armaments during its seven months of operation. Schindler runs out of money in 1945, just as Germany surrenders, ending the war in Europe.

As a Nazi Party member and war profiteer, Schindler must flee the advancing Red Army to avoid capture. The SS guards in Schindler's factory have been ordered to kill the Jews, but Schindler persuades them not to, so that they can "return to [their] families as men, instead of murderers." He bids farewell to his workers and prepares to head west, hoping to surrender to the Americans. The workers give Schindler a signed statement attesting to his role saving Jewish lives, together with a ring engraved with a Talmudic quotation: "Whoever saves one life saves the world entire." Schindler is touched but is also deeply ashamed, as he feels he should have done even more. As the Schindlerjuden (Schindler Jews) wake up the next morning, a Soviet soldier announces that they have been liberated. The Jews leave the factory and walk to a nearby town.

Following scenes depicting Göth's execution after the war and a summary of Schindler's later life, the black-and-white frame changes to a color shot of actual Schindlerjuden at Schindler's grave in Jerusalem. Accompanied by the actors who portrayed them, the Schindlerjuden place stones on the grave. In the final shot, Neeson places a pair of roses on the grave.

Cast

- Liam Neeson as Oskar Schindler

- Ben Kingsley as Itzhak Stern

- Ralph Fiennes as Amon Göth

- Caroline Goodall as Emilie Schindler

- Jonathan Sagall as Poldek Pfefferberg

- Embeth Davidtz as Helen Hirsch

- Małgorzata Gebel as Wiktoria Klonowska

- Mark Ivanir as Marcel Goldberg

- Beatrice Macola as Ingrid

- Andrzej Seweryn as Julian Scherner

- Friedrich von Thun as Rolf Czurda

- Jerzy Nowak as Investor

- Norbert Weisser as Albert Hujar

- Anna Mucha as Danka Dresner

- Adi Nitzan as Mila Pfefferberg

- Piotr Polk as Leo Rosner

- Rami Heuberger as Joseph Bau

- Ezra Dagan as Rabbi Menasha Lewartow

- Elina Löwensohn as Diana Reiter

- Hans-Jörg Assmann as Julius Madritsch

- Hans-Michael Rehberg as Rudolf Höß

- Daniel Del Ponte as Josef Mengele

- Oliwia Dąbrowska as the Girl in Red

Production

Development

Pfefferberg, one of the Schindlerjuden, made it his life's mission to tell the story of his savior. Pfefferberg attempted to produce a biopic of Oskar Schindler with MGM in 1963, with Howard Koch writing, but the deal fell through.[7][8] In 1982, Thomas Keneally published his historical novel Schindler's Ark, which he wrote after a chance meeting with Pfefferberg in Los Angeles in 1980.[9] MCA president Sid Sheinberg sent director Steven Spielberg a New York Times review of the book. Spielberg, astounded by Schindler's story, jokingly asked if it was true. "I was drawn to it because of the paradoxical nature of the character," he said. "What would drive a man like this to suddenly take everything he had earned and put it all in the service of saving these lives?"[10] Spielberg expressed enough interest for Universal Pictures to buy the rights to the novel.[10] At their first meeting in spring 1983, he told Pfefferberg he would start filming in ten years.[11] In the end credits of the film, Pfefferberg is credited as a consultant under the name Leopold Page.[1]

Spielberg was unsure if he was mature enough to make a film about the Holocaust, and the project remained "on [his] guilty conscience".[11] Spielberg tried to pass the project to director Roman Polanski, who turned it down. Polanski's mother was killed at Auschwitz, and he had lived in and survived the Kraków Ghetto.[11] Polanski eventually directed his own Holocaust drama The Pianist (2002). Spielberg also offered the film to Sydney Pollack and Martin Scorsese, who was attached to direct Schindler's List in 1988. However, Spielberg was unsure of letting Scorsese direct the film, as "I'd given away a chance to do something for my children and family about the Holocaust."[12] Spielberg offered him the chance to direct the 1991 remake of Cape Fear instead.[13] Billy Wilder expressed an interest in directing the film as a memorial to his family, most of whom died in the Holocaust.[14]

Spielberg finally decided to take on the project when he noticed that Holocaust deniers were being given serious consideration by the media. With the rise of neo-Nazism after the fall of the Berlin Wall, he worried that people were too accepting of intolerance, as they were in the 1930s.[14] Sid Sheinberg greenlit the film on condition that Spielberg made Jurassic Park first. Spielberg later said, "He knew that once I had directed Schindler I wouldn't be able to do Jurassic Park."[2] The picture was assigned a small budget of $22 million, as Holocaust films are not usually profitable.[15][2] Spielberg forewent a salary for the film, calling it "blood money",[2] and believed the film would flop.[2]

In 1983, Keneally was hired to adapt his book, and he turned in a 220-page script. His adaptation focused on Schindler's numerous relationships, and Keneally admitted he did not compress the story enough. Spielberg hired Kurt Luedtke, who had adapted the screenplay of Out of Africa, to write the next draft. Luedtke gave up almost four years later, as he found Schindler's change of heart too unbelievable.[12] During his time as director, Scorsese hired Steven Zaillian to write a script. When he was handed back the project, Spielberg found Zaillian's 115-page draft too short, and asked him to extend it to 195 pages. Spielberg wanted more focus on the Jews in the story, and he wanted Schindler's transition to be gradual and ambiguous, not a sudden breakthrough or epiphany. He extended the ghetto liquidation sequence, as he "felt very strongly that the sequence had to be almost unwatchable."[12]

Casting

Neeson auditioned as Schindler early on, and was cast in December 1992, after Spielberg saw him perform in Anna Christie on Broadway.[16] Warren Beatty participated in a script reading, but Spielberg was concerned that he could not disguise his accent and that he would bring "movie star baggage".[17] Kevin Costner and Mel Gibson expressed interest in portraying Schindler, but Spielberg preferred to cast the relatively unknown Neeson, so the actor's star quality would not overpower the character.[18] Neeson felt Schindler enjoyed outsmarting the Nazis, who regarded him as a bit of a buffoon. "They don't quite take him seriously, and he used that to full effect."[19] To help him prepare for the role, Spielberg showed Neeson film clips of Time Warner CEO Steve Ross, who had a charisma that Spielberg compared to Schindler's.[20] He also located a tape of Schindler speaking, which Neeson studied to learn the correct intonations and pitch.[21]

Fiennes was cast as Amon Göth after Spielberg viewed his performances in A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia and Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights. Spielberg said of Fiennes' audition that "I saw sexual evil. It is all about subtlety: there were moments of kindness that would move across his eyes and then instantly run cold."[22] Fiennes put on 28 pounds (13 kg) to play the role. He watched historic newsreels and talked to Holocaust survivors who knew Göth. In portraying him, Fiennes said "I got close to his pain. Inside him is a fractured, miserable human being. I feel split about him, sorry for him. He's like some dirty, battered doll I was given and that I came to feel peculiarly attached to."[22] Doctors Samuel J. Leistedt and Paul Linkowski of the Université libre de Bruxelles describe Göth's character in the film as a classic psychopath.[23] Fiennes looked so much like Göth in costume that when Mila Pfefferberg (a survivor of the events) met him, she trembled with fear.[22]

The character of Itzhak Stern (played by Ben Kingsley) is a composite of accountant Stern, factory manager Abraham Bankier, and Göth's personal secretary, Mietek Pemper.[24] The character serves as Schindler's alter ego and conscience.[25] Kingsley is best known for his Academy Award winning performance as Gandhi in the 1982 biographical film.[26]

Overall, there are 126 speaking parts in the film. Thousands of extras were hired during filming.[12] Spielberg cast Israeli and Polish actors specially chosen for their Eastern European appearance.[27] Many of the German actors were reluctant to don the SS uniform, but some of them later thanked Spielberg for the cathartic experience of performing in the movie.[17] Halfway through the shoot, Spielberg conceived the epilogue, where 128 survivors pay their respects at Schindler's grave in Jerusalem. The producers scrambled to find the Schindlerjuden and fly them in to film the scene.[12]

Filming

Principal photography began on March 1, 1993 in Kraków, Poland, with a planned schedule of 75 days.[28] The crew shot at or near the actual locations, though the Płaszów camp had to be reconstructed in a nearby abandoned quarry, as modern high rise apartments were visible from the site of the original camp.[29][30] Interior shots of the enamelware factory in Kraków were filmed at a similar facility in Olkusz, while exterior shots and the scenes on the factory stairs were filmed at the actual factory.[31] The crew was forbidden to do extensive shooting or construct sets on the grounds at Auschwitz, so they shot at a replica constructed just outside the entrance.[32] There were some antisemitic incidents. A woman who encountered Fiennes in his Nazi uniform told him that "the Germans were charming people. They didn't kill anybody who didn't deserve it".[22] Antisemitic symbols were scrawled on billboards near shooting locations,[12] while Kingsley nearly entered a brawl with an elderly German-speaking businessman who insulted Israeli actor Michael Schneider.[33] Nonetheless, Spielberg stated that at Passover, "all the German actors showed up. They put on yarmulkes and opened up Haggadas, and the Israeli actors moved right next to them and began explaining it to them. And this family of actors sat around and race and culture were just left behind."[33]

"I was hit in the face with my personal life. My upbringing. My Jewishness. The stories my grandparents told me about the Shoah. And Jewish life came pouring back into my heart. I cried all the time."

—Steven Spielberg on his emotional state during the shoot[34]

Shooting Schindler's List was deeply emotional for Spielberg, the subject matter forcing him to confront elements of his childhood, such as the antisemitism he faced. He was surprised that he did not cry while visiting Auschwitz; instead he found himself filled with outrage. He was one of many crew members who could not force themselves to watch during shooting of the scene where aging Jews are forced to run naked while being selected by Nazi doctors to go to Auschwitz.[35] Spielberg commented that he felt more like a reporter than a film maker – he would set up scenes and then watch events unfold, almost as though he were witnessing them rather than creating a movie.[29] Several actresses broke down when filming the shower scene, including one who was born in a concentration camp.[17] Spielberg, his wife Kate Capshaw, and their five children rented a house in suburban Kraków for the duration of filming.[36] He later thanked his wife "for rescuing me ninety-two days in a row ... when things just got too unbearable".[37] Robin Williams called Spielberg to cheer him up, given the profound lack of humor on the set.[37] Spielberg spent several hours each evening editing Jurassic Park, which was scheduled to premiere in June 1993.[38]

Spielberg occasionally used German and Polish language in scenes to recreate the feeling of being present in the past. He initially considered making the film entirely in those languages, but decided "there's too much safety in reading. It would have been an excuse to take their eyes off the screen and watch something else."[17]

Cinematography

Influenced by the 1985 documentary film Shoah, Spielberg decided not to plan the film with storyboards, and to shoot it like a documentary. Forty percent of the film was shot with handheld cameras, and the modest budget meant the film was shot quickly over seventy-two days.[39] Spielberg felt that this gave the film "a spontaneity, an edge, and it also serves the subject."[40] He filmed without using Steadicams, elevated shots, or zoom lenses, "everything that for me might be considered a safety net."[40] This matured Spielberg, who felt that in the past he had always been paying tribute to directors such as Cecil B. DeMille or David Lean.[33]

The decision to shoot the film mainly in black and white contributed to the documentary style of cinematography, which cinematographer Janusz Kamiński compared to German Expressionism and Italian neorealism.[40] Kamiński said that he wanted to give the impression of timelessness to the film, so the audience would "not have a sense of when it was made."[29] Spielberg decided to use black and white to match the feel of actual documentary footage of the era.[40] Universal chairman Tom Pollock asked him to shoot the film on a color negative, to allow color VHS copies of the film to later be sold, but Spielberg did not want to accidentally "beautify events."[40]

Music

John Williams, who frequently collaborates with Spielberg, composed the score for Schindler's List. The composer was amazed by the film, and felt it would be too challenging. He said to Spielberg, "You need a better composer than I am for this film." Spielberg responded, "I know. But they're all dead!"[41] Itzhak Perlman performs the theme on the violin.[1]

Regarding Schindler's List, Perlman said:

Perlman: "I couldn't believe how authentic he [John Williams] got everything to sound, and I said, 'John, where did it come from?' and he said, 'Well I had some practice with Fiddler on the Roof and so on, and everything just came very naturally' and that's the way it sounds."

Interviewer: "When you were first approached to play for Schindler's List, did you give it a second thought, did you agree at once, or did you say 'I'm not sure I want to play for movie music'?

Perlman: "No, that never occurred to me, because in that particular case the subject of the movie was so important to me, and I felt that I could contribute simply by just knowing the history, and feeling the history, and indirectly actually being a victim of that history."[42]

In the scene where the ghetto is being liquidated by the Nazis, the folk song "Oyfn Pripetshik" ("On the Cooking Stove") (Yiddish: אויפֿן פּריפּעטשיק) is sung by a children's choir. The song was often sung by Spielberg's grandmother, Becky, to her grandchildren.[43] The clarinet solos heard in the film were recorded by Klezmer virtuoso Giora Feidman.[44] Williams won an Academy Award for Best Original Score for Schindler's List, his fifth win.[45] Selections from the score were released on a soundtrack album.[46]

Themes and symbolism

The film explores the theme of good versus evil, using as its main protagonist a "good German", a popular characterization in American cinema.[47][14] While Göth is characterized as an almost completely dark and evil person, Schindler gradually evolves from Nazi supporter to rescuer and hero.[48] Thus a second theme of redemption is introduced as Schindler, a disreputable schemer on the edges of respectability, becomes a father figure responsible for saving the lives of more than a thousand people.[49][50]

The girl in red

While the film is shot primarily in black and white, a red coat is used to distinguish a little girl in the scene depicting the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto. Later in the film, Schindler sees her dead body, recognizable only by the red coat she is still wearing. Spielberg said the scene was intended to symbolise how members of the highest levels of government in the United States knew the Holocaust was occurring, yet did nothing to stop it. "It was as obvious as a little girl wearing a red coat, walking down the street, and yet nothing was done to bomb the German rail lines. Nothing was being done to slow down ... the annihilation of European Jewry," he said. "So that was my message in letting that scene be in color."[51] Andy Patrizio of IGN notes that the point at which Schindler sees the girl's dead body is the point at which he changes, no longer seeing "the ash and soot of burning corpses piling up on his car as just an annoyance."[52] Professor André H. Caron of the Université de Montréal wonders if the red symbolises "innocence, hope or the red blood of the Jewish people being sacrificed in the horror of the Holocaust."[53]

The girl was portrayed by Oliwia Dąbrowska, three years old at the time of filming. Spielberg asked Dąbrowska not to watch the film until she was eighteen, but she watched it when she was eleven, and was "horrified."[54] Upon seeing the film again as an adult, she was proud of the role she played.[54] Although it was unintentional, the character is similar to Roma Ligocka, who was known in the Kraków Ghetto for her red coat. Ligocka, unlike her fictional counterpart, survived the Holocaust. After the film was released, she wrote and published her own story, The Girl in the Red Coat: A Memoir (2002, in translation).[55] According to a 2014 interview of family members, the girl in red was inspired by Kraków resident Genya Gitel Chil.[56]

Candles

The opening scene features a family observing Shabbat. Spielberg said that "to start the film with the candles being lit ... would be a rich bookend, to start the film with a normal Shabbat service before the juggernaut against the Jews begins."[12] When the color fades out in the film's opening moments, it gives way to a world in which smoke comes to symbolize bodies being burnt at Auschwitz. Only at the end, when Schindler allows his workers to hold Shabbat services, do the images of candle fire regain their warmth. For Spielberg, they represent "just a glint of color, and a glimmer of hope."[12] Sara Horowitz, director of the Koschitzky Centre for Jewish Studies at York University, sees the candles as a symbol for the Jews of Europe, killed and then burned in the crematoria. The two scenes bracket the Nazi era, marking its beginning and end.[57] She points out that normally the woman of the house lights the Sabbath candles. In the film it is men who perform this ritual, demonstrating not only the subservient role of women, but also the subservient position of Jewish men in relation to Aryan men, especially Göth and Schindler.[58]

Other symbolism

To Spielberg, the black and white presentation of the film came to represent the Holocaust itself: "The Holocaust was life without light. For me the symbol of life is color. That's why a film about the Holocaust has to be in black-and-white."[59] Robert Gellately notes the film in its entirety can be seen as a metaphor for the Holocaust, with early sporadic violence increasing into a crescendo of death and destruction. He also notes a parallel between the situation of the Jews in the film and the debate in Nazi Germany between making use of the Jews for slave labor or exterminating them outright.[60] Water is seen as giving deliverance by Alan Mintz, Holocaust Studies professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York. He notes its presence in the scene where Schindler arranges for a Holocaust train loaded with victims awaiting transport to be hosed down, and the scene in Auschwitz, where the women are given an actual shower instead of receiving the expected gassing.[61]

Release

The film opened on December 15, 1993. By the time it closed in theaters on September 29, 1994, it had grossed $96.1 million ($203 million in 2024 dollars)[62] in the United States and over $321.2 million worldwide.[63] In Germany, where it was shown in 500 theaters, the film was viewed by over 100,000 people in its first week alone[64] and was eventually seen by six million people.[65] The film was popular in Germany and a success worldwide.[66]

Schindler's List made its U.S. network television premiere on NBC on February 23, 1997. Shown without commercials, it ranked #3 for the week with a 20.9/31 rating/share,[67] highest Nielsen rating for any film since NBC's broadcast of Jurassic Park in May 1995. The film aired on public television in Israel on Holocaust Memorial Day in 1998.[68]

The DVD was released on March 9, 2004 in widescreen and fullscreen editions, on a double-sided disc with the feature film beginning on side A and continuing on side B. Special features include a documentary introduced by Spielberg.[69] Also released for both formats was a limited edition gift set, which included the widescreen version of the film, Keneally's novel, the film's soundtrack on CD, a senitype, and a photo booklet titled Schindler's List: Images of the Steven Spielberg Film, all housed in a plexiglass case.[70] The laserdisc gift set was a limited edition that included the soundtrack, the original novel, and an exclusive photo booklet.[71] As part of its 20th anniversary, the movie was released on Blu-ray Disc on March 5, 2013.[72]

Following the success of the film, Spielberg founded the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, a nonprofit organization with the goal of providing an archive for the filmed testimony of as many survivors of the Holocaust as possible, to save their stories. He continues to finance that work.[73] Spielberg used proceeds from the film to finance several related documentaries, including Anne Frank Remembered (1995), The Lost Children of Berlin (1996), and The Last Days (1998).[74]

Reception

Critical response

Schindler's List received acclaim from both film critics and audiences.[75] On Rotten Tomatoes, the film received an approval rating of 96%, based on 81 reviews. The site's consensus reads "Schindler's List blends the abject horror of the Holocaust with Steven Spielberg's signature tender humanism to create the director's dramatic masterpiece."[76] Americans such as talk show host Oprah Winfrey and President Bill Clinton urged their countrymen to see it.[3][77] World leaders in many countries saw the film, and some met personally with Spielberg.[3] CinemaScore reported that audiences gave the film a rare "A+" grade.[78]

Stephen Schiff of The New Yorker called it the best historical drama about the Holocaust, a movie that "will take its place in cultural history and remain there."[79] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times described it as Spielberg's best, "brilliantly acted, written, directed, and seen."[80] Ebert named it one of his ten favorite films of 1993.[81] Terrence Rafferty, also with The New Yorker, admired the film's "narrative boldness, visual audacity, and emotional directness." He noted the performances of Neeson, Fiennes, Kingsley, and Davidtz as warranting special praise,[82] and calls the scene in the shower at Auschwitz "the most terrifying sequence ever filmed."[83] In his 2013 movie guide, Leonard Maltin awarded the film a four-star rating, calling it a "staggering adaptation of Thomas Keneally's best-seller," saying "this looks and feels like nothing Hollywood has ever made before". He also described it as "Spielberg's most intense and personal film to date".[84] James Verniere of the Boston Herald noted the film's restraint and lack of sensationalism, and called it a "major addition to the body of work about the Holocaust."[85] In his review for the New York Review of Books, British critic John Gross said his misgivings that the story would be overly sentimentalized "were altogether misplaced. Spielberg shows a firm moral and emotional grasp of his material. The film is an outstanding achievement."[86] Mintz notes that even the film's harshest critics admire the "visual brilliance" of the fifteen-minute segment depicting the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto. He describes the sequence as "realistic" and "stunning".[87] He points out that the film has done much to increase Holocaust remembrance and awareness as the remaining survivors pass away, severing the last living links with the catastrophe.[88] The film's release in Germany led to widespread discussion about why most Germans did not do more to help.[89]

Criticism of the film also appeared, mostly from academia rather than the popular press.[90] Horowitz points out that much of the Jewish activity seen in the ghetto consists of financial transactions such as lending money, trading on the black market, or hiding wealth, thus perpetuating a stereotypical view of Jewish life.[91] Horowitz notes that while the depiction of women in the film accurately reflects Nazi ideology, the low status of women and the link between violence and sexuality is not explored further.[92] History professor Omer Bartov of Brown University notes that the physically large and strongly drawn characters of Schindler and Göth overshadow the Jewish victims, who are depicted as small, scurrying, and frightened – a mere backdrop to the struggle of good versus evil.[93]

Horowitz points out that the film's dichotomy of absolute good versus absolute evil glosses over the fact that the vast majority of Holocaust perpetrators were ordinary people; the movie does not explore how the average German rationalized their knowledge of or participation in the Holocaust.[94] Author Jason Epstein commented that the movie gives the impression that if people were smart enough or lucky enough, they could survive the Holocaust; this was not actually the case.[95] Spielberg responded to criticism that Schindler's breakdown as he says farewell is too maudlin and even out of character by pointing out that the scene is needed to drive home the sense of loss and to allow the viewer an opportunity to mourn alongside the characters on the screen.[96]

Assessment by other filmmakers

Schindler's List was very well received by many of Spielberg's peers. Filmmaker Billy Wilder wrote to Spielberg saying, "They couldn't have gotten a better man. This movie is absolutely perfection."[14] Polanski, who turned down the chance to direct the film, later commented, "I certainly wouldn't have done as good a job as Spielberg because I couldn't have been as objective as he was."[97] He cited Schindler's List as an influence on his 1995 film Death and the Maiden.[98] The success of Schindler's List led filmmaker Stanley Kubrick to abandon his own Holocaust project, Aryan Papers, which would have been about a Jewish boy and his aunt who survive the war by sneaking through Poland while pretending to be Catholic.[99] When scriptwriter Frederic Raphael suggested that Schindler's List was a good representation of the Holocaust, Kubrick commented, "Think that's about the Holocaust? That was about success, wasn't it? The Holocaust is about 6 million people who get killed. Schindler's List is about 600 who don't."[99][a]

Filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard accused Spielberg of using the film to make a profit out of a tragedy while Schindler's wife, Emilie Schindler, lived in poverty in Argentina.[101] Keneally disputed claims that she was never paid for her contributions, "not least because I had recently sent Emilie a check myself."[102] He also confirmed with Spielberg's office that payment had been sent from there.[102] Filmmaker Michael Haneke criticized the sequence in which Schindler's women are accidentally sent off to Auschwitz and herded into showers: "There's a scene in that film when we don't know if there's gas or water coming out in the showers in the camp. You can only do something like that with a naive audience like in the United States. It's not an appropriate use of the form. Spielberg meant well – but it was dumb."[103]

The film was criticized by filmmaker and lecturer Claude Lanzmann, director of the nine-hour Holocaust film Shoah, who called Schindler's List a "kitschy melodrama" and a "deformation" of historical truth. "Fiction is a transgression, I am deeply convinced that there is a ban on depiction [of the Holocaust]", he said. Lanzmann also criticized Spielberg for viewing the Holocaust through the eyes of a German, saying "it is the world in reverse." He complained, "I sincerely thought that there was a time before Shoah, and a time after Shoah, and that after Shoah certain things could no longer be done. Spielberg did them anyway."[104]

Reaction of the Jewish community

At a 1994 Village Voice symposium about the film, historian Annette Insdorf described how her mother, a survivor of three concentration camps, felt gratitude that the Holocaust story was finally being told in a major film that would be widely viewed.[105] Hungarian Jewish author Imre Kertész, a Holocaust survivor, feels it is impossible for life in a Nazi concentration camp to be accurately portrayed by anyone who did not experience it first-hand. While commending Spielberg for bringing the story to a wide audience, he found the film's final scene at the graveyard neglected the terrible after-effects of the experience on the survivors and implied that they came through emotionally unscathed.[106] Rabbi Uri D. Herscher found the film an "appealing" and "uplifting" demonstration of humanitarianism.[107] Norbert Friedman noted that, like many Holocaust survivors, he reacted with a feeling of solidarity towards Spielberg of a sort normally reserved for other survivors.[108] Albert L. Lewis, Spielberg's childhood rabbi and teacher, described the movie as "Steven's gift to his mother, to his people, and in a sense to himself. Now he is a full human being."[107]

Accolades

Schindler's List featured on a number of "best of" lists, including the TIME magazine's Top Hundred as selected by critics Richard Corliss and Richard Schickel,[4] Time Out magazine's 100 Greatest Films Centenary Poll conducted in 1995,[109] and Leonard Maltin's "100 Must See Movies of the Century".[5] The Vatican named Schindler's List among the most important 45 films ever made.[110] A Channel 4 poll named Schindler's List the ninth greatest film of all time,[6] and it ranked fourth in their 2005 war films poll.[111] The film was named the best of 1993 by critics such as James Berardinelli,[112] Roger Ebert,[81] and Gene Siskel.[113] Deeming the film "culturally significant", the Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2004.[114] Spielberg won the Directors Guild of America Award for Outstanding Directing – Feature Film for his work,[115] and shared the Producers Guild of America Award for Best Theatrical Motion Picture with co-producers Branko Lustig and Gerald R. Molen.[116] Steven Zaillian won the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.[117]

The film also won the National Board of Review for Best Film, along with the National Society of Film Critics for Best Film, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor, and Best Cinematography.[118] Awards from the New York Film Critics Circle were also won for Best Film, Best Supporting Actor, and Best Cinematographer.[119] The Los Angeles Film Critics Association awarded the film for Best Film, Best Cinematography (tied with The Piano), and Best Production Design.[120] The film also won numerous other awards and nominations worldwide.[121]

| Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[45] | ||

| Best Picture | Won | |

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Won |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Steven Zaillian | Won |

| Best Original Score | John Williams | Won[b] |

| Best Film Editing | Michael Kahn | Won |

| Best Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński | Won |

| Best Art Direction | Won | |

| Best Actor | Liam Neeson | Nominated |

| Best Supporting Actor | Ralph Fiennes | Nominated |

| Best Sound | Nominated | |

| Best Makeup | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Anna B. Sheppard | Nominated |

| ACE Eddie Award[122] | ||

| Best Editing | Michael Kahn | Won |

| British Academy Film Awards[123] | ||

| Best Film |

|

Won |

| Best Direction | Steven Spielberg | Won |

| Best Supporting Actor | Ralph Fiennes | Won |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Steven Zaillian | Won |

| Best Music | John Williams | Won |

| Best Editing | Michael Kahn | Won |

| Best Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński | Won |

| Best Supporting Actor | Ben Kingsley | Nominated |

| Best Actor | Liam Neeson | Nominated |

| Best Makeup and Hair |

|

Nominated |

| Best Production Design | Allan Starski | Nominated |

| Best Costume Design | Anna B. Sheppard | Nominated |

| Best Sound |

|

Nominated |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Awards[124] | ||

| Best Film |

|

Won |

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Won |

| Best Screenplay | Steven Zaillian | Won |

| Best Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński | Won |

| Best Actor | Liam Neeson | Won |

| Best Supporting Actor | Ralph Fiennes | Won |

| Golden Globe Awards[125] | ||

| Best Motion Picture – Drama |

|

Won |

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Won |

| Best Screenplay | Steven Zaillian | Won |

| Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama | Liam Neeson | Nominated |

| Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Ralph Fiennes | Nominated |

| Best Original Score | John Williams | Nominated |

| Year | List | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1998 | AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies | #9[126] |

| 2003 | AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains | Oskar Schindler – #13 hero; Amon Göth – #15 villain[127] |

| 2005 | AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes | "The list is an absolute good. The list is life." – nominated[128] |

| 2006 | AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers | #3[129] |

| 2007 | AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) | #8[130] |

| 2008 | AFI's 10 Top 10 | #3 epic film[131] |

Controversies

For the 1997 American television showing, the film was broadcast virtually unedited. The telecast was the first to receive a TV-M (now TV-MA) rating under the TV Parental Guidelines that had been established earlier that year.[132] Senator Tom Coburn, then an Oklahoma congressman, said that in airing the film, NBC had brought television "to an all-time low, with full-frontal nudity, violence and profanity", adding that it was an insult to "decent-minded individuals everywhere".[133] Under fire from both Republicans and Democrats, Coburn apologized, saying: "My intentions were good, but I've obviously made an error in judgment in how I've gone about saying what I wanted to say." He clarified his opinion, stating that the film ought to have been aired later at night when there would not be "large numbers of children watching without parental supervision".[134]

Controversy arose in Germany for the film's television premiere on ProSieben. Heavy protests ensued when the station intended to televise it with two commercial breaks. As a compromise, the broadcast included one break, consisting of a short news update and several commercials.[65]

In the Philippines, chief censor Henrietta Mendez ordered cuts of three scenes depicting sexual intercourse and female nudity before the movie could be shown in theaters. Spielberg refused, and pulled the film from screening in Philippine cinemas, which prompted the Senate to demand the abolition of the censorship board. President Fidel V. Ramos himself intervened, ruling that the movie could be shown uncut to anyone over the age of 15.[135]

According to Slovak filmmaker Juraj Herz, the scene in which a group of women confuse an actual shower with a gas chamber is taken directly, shot by shot, from his film Zastihla mě noc (Night Caught Up with Me, 1986). Herz wanted to sue, but was unable to fund the case.[136]

The song Yerushalayim Shel Zahav ("Jerusalem of Gold") is featured in the film's soundtrack and plays near the end of the film. This caused some controversy in Israel, as the song (which was written in 1967 by Naomi Shemer) is widely considered an informal anthem of the Israeli victory in the Six-Day War. In Israeli prints of the film the song was replaced with Halikha LeKesariya ("A Walk to Caesarea") by Hannah Szenes, a World War II resistance fighter.[137]

Impact on Krakow

Due to the increased interest in Kraków created by the film, the city bought Oskar Schindler's Enamel Factory in 2007 to create a permanent exhibition about the German occupation of the city from 1939 to 1945. The museum opened in June 2010.[138]

See also

Notes

- ^ Schindler is actually credited with saving more than 1,200 Jews.[100]

- ^ Williams also won a Grammy for the film's musical score. Freer 2001, p. 234.

Citations

- ^ a b c Freer 2001, p. 220.

- ^ a b c d e McBride 1997, p. 416.

- ^ a b c McBride 1997, p. 435.

- ^ a b Corliss & Schickel 2005.

- ^ a b Maltin 1999.

- ^ a b Channel 4 2008.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 425.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 557.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 6.

- ^ a b McBride 1997, p. 424.

- ^ a b c McBride 1997, p. 426.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Thompson 1994.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 603.

- ^ a b c d McBride 1997, p. 427.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 27.

- ^ Palowski 1998, pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b c d Susan Royal interview.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 86.

- ^ Entertainment Weekly, January 21, 1994.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 429.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 87.

- ^ a b c d Corliss 1994.

- ^ Leistedt & Linkowski 2014.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 102.

- ^ Freer 2001, p. 225.

- ^ Palowski 1998, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 128.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 48.

- ^ a b c McBride 1997, p. 431.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 14.

- ^ Palowski 1998, pp. 109, 111.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Ansen & Kuflik 1993.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 414.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 433.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 44.

- ^ a b McBride 1997, p. 415.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 45.

- ^ McBride 1997, pp. 431–432, 434.

- ^ a b c d e McBride 1997, p. 432.

- ^ Gangel 2005.

- ^ Perlman video interview.

- ^ Rubin 2001, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Medien 2011.

- ^ a b 66th Academy Awards 1994.

- ^ AllMusic listing.

- ^ Loshitsky 1997, p. 5.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 428.

- ^ Loshitsky 1997, p. 43.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 436.

- ^ Schickel 2012, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Patrizio 2004.

- ^ Caron 2003.

- ^ a b Gilman 2013.

- ^ Logocka 2002.

- ^ Rosner 2014.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, p. 124.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 112.

- ^ Gellately 1993.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 154.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Freer 2001, p. 233.

- ^ Loshitsky 1997, pp. 9, 14.

- ^ a b Berliner Zeitung 1997.

- ^ Loshitsky 1997, pp. 11, 14.

- ^ Broadcasting & Cable 1997.

- ^ Meyers, Zandberg & Neiger 2009, p. 456.

- ^ Amazon, DVD.

- ^ Amazon, Gift set.

- ^ Amazon, Laserdisc.

- ^ Amazon, Blu-ray.

- ^ Freer 2001, p. 235.

- ^ Freer 2001, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 126.

- ^ "Schindler's List". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, p. 119.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (August 19, 2011). "Why CinemaScore Matters for Box Office". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ Schiff 1994, p. 98.

- ^ Ebert 1993a.

- ^ a b Ebert 1993b.

- ^ Rafferty 1993.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 132.

- ^ Maltin 2013, p. 1216.

- ^ Verniere 1993.

- ^ Gross 1994.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 147.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 131.

- ^ Houston Post 1994.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 134.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, p. 130.

- ^ Bartov 1997, p. 49.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, p. 137.

- ^ Epstein 1994.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 439.

- ^ Cronin 2005, p. 168.

- ^ Cronin 2005, p. 167.

- ^ a b Goldman 2005.

- ^ "Mietek Pemper: Obituary". The Daily Telegraph. June 15, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ^ Ebert 2002.

- ^ a b Keneally 2007, p. 265.

- ^ Haneke 2009.

- ^ Lanzmann 2007.

- ^ Mintz 2001, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Kertész 2001.

- ^ a b McBride 1997, p. 440.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 136.

- ^ Time Out Film Guide 1995.

- ^ Greydanus 1995.

- ^ Channel 4 2005.

- ^ Berardinelli 1993.

- ^ Johnson 2011.

- ^ Library of Congress 2004.

- ^ CBC 2013.

- ^ Producers Guild Awards.

- ^ Pond 2011.

- ^ National Society of Film Critics.

- ^ Maslin 1993.

- ^ Los Angeles Film Critics Association.

- ^ Loshitsky 1997, pp. 2, 21.

- ^ Giardina 2011.

- ^ BAFTA Awards 1994.

- ^ Chicago Film Critics Awards 1993.

- ^ Golden Globe Awards 1993.

- ^ American Film Institute 1998.

- ^ American Film Institute 2003.

- ^ American Film Institute 2005.

- ^ American Film Institute 2006.

- ^ American Film Institute 2007.

- ^ American Film Institute 2008.

- ^ Chuang 1997.

- ^ Chicago Tribune 1997.

- ^ CNN 1997.

- ^ Branigin 1994.

- ^ Kosulicova 2002.

- ^ Bresheeth 1997, p. 205.

- ^ Pavo Travel 2014.

References

- "6th Annual Chicagos Film Critics Awards". Chicago Film Critics Association. 1993. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- "19th Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. 2007. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- "The 66th Academy Awards (1994) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. March 21, 1994. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- "100 Greatest Films". Channel 4. April 8, 2008. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- "100 Greatest War Films". Channel 4. Archived from the original on May 18, 2005. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies". American Film Institute. 1998. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Heroes and Villains" (PDF). American Film Institute. 2003. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Quotes" (PDF). American Film Institute. 2005. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Cheers". American Film Institute. May 31, 2006. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies – 10th Anniversary Edition". American Film Institute. June 20, 2007. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- "AFI's 10 Top 10: Top 10 Epic". American Film Institute. 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- Ansen, David; Kuflik, Abigail (December 19, 1993). "Spielberg's obsession". Newsweek. Vol. 122, no. 25. pp. 112–116.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Bafta Awards: Schindler's List". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- Bartov, Omer (1997). "Spielberg's Oskar: Hollywood Tries Evil". In Loshitzky, Yosefa (ed.). Spielberg's Holocaust: Critical Perspectives on Schindler's List. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 41–60. ISBN 0-253-21098-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Berardinelli, James (December 31, 1993). "Rewinding 1993 – The Best Films". reelviews.net. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Branigin, William (March 9, 1994). "'Schindler's List' Fuss In Philippines – Censors Object To Sex, Not The Nazi Horrors". The Seattle Times.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bresheeth, Haim (1997). "The Great Taboo Broken: Reflections on the Israeli Reception of Schindler's List". In Loshitzky, Yosefa (ed.). Spielberg's Holocaust: Critical Perspectives on Schindler's List. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 193–212. ISBN 0-253-21098-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Caron, André (July 25, 2003). "Spielberg's Fiery Lights". The Question Spielberg: A Symposium Part Two: Films and Moments. Senses of Cinema. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chuang, Angie (February 25, 1997). "Television: 'Schindler's' Showing". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Corliss, Richard (February 21, 1994). "The Man Behind the Monster". Time. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Corliss, Richard; Schickel, Richard (2005). "All-Time 100 Best Movies". Time. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cronin, Paul, ed. (2005). Roman Polanski: Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-799-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crowe, David M. (2004). Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account of His Life, Wartime Activities, and the True Story Behind the List. Cambridge, MA: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-465-00253-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ebert, Roger (December 15, 1993). "Schindler's List". Roger Ebert's Journal. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- Ebert, Roger (December 31, 1993). "The Best 10 Movies of 1993". Roger Ebert's Journal. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- Ebert, Roger (October 18, 2002). "In Praise Of Love". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Epstein, Jason (April 21, 1994). "A Dissent on 'Schindler's List'". The New York Review of Books. New York. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Freer, Ian (2001). The Complete Spielberg. Virgin Books. pp. 220–237. ISBN 0-7535-0556-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gangel, Jamie (May 6, 2005). "The man behind the music of 'Star Wars'". NBC. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gellately, Robert (1993). "Between Exploitation, Rescue, and Annihilation: Reviewing Schindler's List". Central European History. 26 (4). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 475–489. doi:10.1017/S0008938900009419. JSTOR 4546374.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Giardina, Carolyn (February 7, 2011). "Michael Kahn, Michael Brown to Receive ACE Lifetime Achievement Awards". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gilman, Greg (March 5, 2013). "Red coat girl traumatized by 'Schindler's List'". Sarnia Observer. Sarnia, Ontario. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goldman, A. J. (August 25, 2005). "Stanley Kubrick's Unrealized Vision". Jewish Journal. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Greydanus, Steven D. (March 17, 1995). "The Vatican Film List". Decent Films. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gross, John (February 3, 1994). "Hollywood and the Holocaust". New York Review of Books. Vol. 16, no. 3. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Haneke, Michael (November 14, 2009). "Michael Haneke discusses 'The White Ribbon'". Time Out London. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Horowitz, Sara (1997). "But Is It Good for the Jews? Spielberg's Schindler and the Aesthetics of Atrocity". In Loshitzky, Yosefa (ed.). Spielberg's Holocaust: Critical Perspectives on Schindler's List. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 119–139. ISBN 0-253-21098-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Johnson, Eric C. (February 28, 2011). "Gene Siskel's Top Ten Lists 1969–1998". Index of Critics. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keneally, Thomas (2007). Searching for Schindler: A Memoir. New York: Nan A. Talese. ISBN 978-0-385-52617-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kertész, Imre (Spring 2001). "Who Owns Auschwitz?". Yale Journal of Criticism. 14 (1). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press: 267–272. doi:10.1353/yale.2001.0010.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kosulicova, Ivana (January 7, 2002). "Drowning the bad times: Juraj Herz interviewed". Kinoeye. Vol. 2, no. 1. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lanzmann, Claude (2007). "Schindler's List is an impossible story". University College Utrecht. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Leistedt, Samuel J.; Linkowski, Paul (January 2014). "Psychopathy and the Cinema: Fact or Fiction?". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 59 (1): 167–174. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.12359. PMID 24329037. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Librarian of Congress Adds 25 Films to National Film Registry". Library of Congress. December 28, 2004. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- Ligocka, Roma. "The Girl in the Red Coat: A Memoir". MacMillan. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- Loshitsky, Yosefa (1997). "Introduction". In Loshitzky, Yosefa (ed.). Spielberg's Holocaust: Critical Perspectives on Schindler's List. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 1–17. ISBN 0-253-21098-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Maltin, Leonard (1999). "100 Must-See Films of the 20th Century". Movie and Video Guide 2000. American Movie Classics Company. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Maltin, Leonard (2013). Leonard Maltin's 2013 Movie Guide: The Modern Era. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-451-23774-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Maslin, Janet (December 16, 1993). "New York Critics Honor 'Schindler's List'". The New York Times. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McBride, Joseph (1997). Steven Spielberg: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81167-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Medien, Nasiri (2011). "A Life Like A Song With Ever Changing Verses". giorafeidman-online.com. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Meyers, Oren; Zandberg, Eyal; Neiger, Motti (September 2009). "Prime Time Commemoration: An Analysis of Television Broadcasts on Israel's Memorial Day for the Holocaust and the Heroism" (PDF). Journal of Communication. 59 (3): 456–480. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01424.x. ISSN 0021-9916. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mintz, Alan (2001). Popular Culture and the Shaping of Holocaust Memory in America. The Samuel and Althea Stroum Lectures in Jewish Studies. Seattle; London: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-98161-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Palowski, Franciszek (1998) [1993]. The Making of Schindler's List: Behind the Scenes of an Epic Film. Secaucus, NJ: Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 1-55972-445-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. 2013. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- Patrizio, Andy (March 10, 2004). "Schindler's List: The DVD is good, too". IGN Entertainment. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Perlman, Itzhak. John Williams, Itzhak Perlman – Schindler's List. YouTube. Event occurs at 00:00 to 00:51. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- "PGA Award Winners 1990–2010". Producers Guild of America. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- Pond, Steve (January 19, 2011). "Steven Zaillian to Receive WGA Laurel Award". The Wrap News. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rafferty, Terrence (1993). "The Film File: Schindler's List". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rosner, Orin (April 23, 2014). "לכל איש יש שם – גם לילדה עם המעיל האדום מ"רשימת שינדלר"". Ynet. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Royal, Susan. "An Interview with Steven Spielberg". Inside Film Magazine Online. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- Rubin, Susan Goldman (2001). Steven Spielberg: Crazy for Movies. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-4492-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schickel, Richard (2012). Steven Spielberg: A Retrospective. New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-9650-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schiff, Stephen (March 21, 1994). "Seriously Spielberg". The New Yorker. pp. 96–109.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Schindler's List". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- "Schindler's List: Box Set Laserdisc Edition". Amazon. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- "Schindler's List (Blu-ray + DVD + Digital Copy + UltraViolet) (1993)". Amazon. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- "Schindler's List (Widescreen Edition) (1993)". Amazon. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- "Schindler's List Collector's Gift Set (1993)". Amazon. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- Staff (February 26, 1997). "After rebuke, congressman apologizes for 'Schindler's List' remarks". CNN. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- Staff (February 28, 1994). "German "Schindler's List" Debut Launches Debate, Soul-Searching". Houston Post. Reuters.

- Staff (February 26, 1997). "GOP Lawmaker Blasts NBC For Airing 'Schindler's List'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- Staff (December 5, 2014). "How did "Schindler's List" change Krakow?". Pavo Travel. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- Staff (February 21, 1997). ""Mehr Wirkung ohne Werbung": Gemischte Reaktionen jüdischer Gemeinden auf geplante Unterbrechung von "Schindlers Liste"". Berliner Zeitung (in German). Berlin. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- Staff (January 21, 1994). "Oskar Winner: Liam Neeson joins the A-List after 'Schindler's List'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- Staff (March 3, 1997). "People's Choice: Ratings according to Nielsen Feb. 17–23" (PDF). Broadcasting & Cable. p. 31.

- Staff. "John Williams: Schindler's List". All Media Network. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- Staff (January 8, 2013). "Spielberg earns 11th Directors Guild nomination". CBC News. Associated Press. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- Thompson, Anne (January 21, 1994). "Spielberg and 'Schindler's List': How it came together". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Top 100 Films (Centenary) from Time Out". 1995. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- Verniere, James (December 15, 1993). "Holocaust Drama is a Spielberg Triumph". Boston Herald.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Schindler's List at IMDb

- Schindler's List at the American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures

- Schindler's List at the TCM Movie Database

- Schindler's List at Box Office Mojo

- Schindler's List at Rotten Tomatoes

- Schindler's List at Metacritic

- The Shoah Foundation, founded by Steven Spielberg, preserves the testimonies of Holocaust survivors and witnesses

- Through the Lens of History: Aerial Evidence for Schindler’s List at Yad Vashem

- Schindler's List bibliography at UC Berkeley

- Voices on Antisemitism Interview with Ralph Fiennes from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Voices on Antisemitism interview with Sir Ben Kingsley from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- "Schindler's List: Myth, movie, and memory" (PDF). The Village Voice: 24–31. March 29, 1994.

- 1993 films

- English-language films

- 1990s biographical films

- 1990s drama films

- 1990s war films

- Amblin Entertainment films

- American biographical films

- American drama films

- American epic films

- American films

- American war films

- Amon Göth

- Best Drama Picture Golden Globe winners

- Best Film BAFTA Award winners

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- American black-and-white films

- Drama films based on actual events

- Epic films based on actual events

- World War II films based on actual events

- Film scores by John Williams

- Films about Jews and Judaism

- Films based on Australian novels

- Films directed by Steven Spielberg

- Films produced by Steven Spielberg

- Films set in Germany

- Films set in Kraków

- Films set in Poland

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films set in the 1940s

- Films shot in Israel

- Films shot in Kraków

- Films shot in Poland

- Films shot partially in color

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- Films whose art director won the Best Art Direction Academy Award

- Films whose cinematographer won the Best Cinematography Academy Award

- Films whose director won the Best Direction BAFTA Award

- Films whose director won the Best Directing Academy Award

- Films whose director won the Best Director Golden Globe

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay BAFTA Award

- Holocaust films

- Oskar Schindler

- Rescue of Jews in the Holocaust

- Screenplays by Steven Zaillian

- United States National Film Registry films

- Universal Pictures films

- War epic films

- Films produced by Gerald R. Molen