Vinpocetine

This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (January 2014) |  |

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 56.6 +/- 8.9% |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 2.54 +/- 0.48 hours |

| Excretion | renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.050.917 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

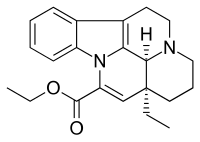

| Formula | C22H26N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 350.454 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Vinpocetine (brand names: Cavinton, Intelectol; chemical name: ethyl apovincaminate) is a synthetic derivative of the vinca alkaloid vincamine (sometimes described as "a synthetic ethyl ester of apovincamine"),[1] an extract from the lesser periwinkle plant. Vinpocetine was first isolated from the plant in 1975 by the Hungarian chemist Csaba Szántay. The mass production of the synthetic compound was started in 1978 by the Hungarian pharmaceutical company Richter Gedeon.

Vinpocetine is not FDA approved in the United States for therapeutic use. The U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) has ruled that vinpocetine, due to its synthetic nature and proposed therapeutic uses, was ineligible to be marketed as dietary supplement under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA).[2][3][4]

Vinpocetine has been reported to have cerebral blood-flow enhancing[5] and neuroprotective effects,[6] and has been used as a drug in Eastern Europe for the treatment of cerebrovascular disorders and age-related memory impairment.[7][unreliable medical source?]

Controlled clinical trials

As of 2003 only three controlled clinical trials had tested "older adults with memory problems".[8] However, a 2003 Cochrane review determined that the results were inconclusive.[9]

In vitro and animal studies

Kindling models in rats has shown vinpocetine to exhibit anticonvulsant properties. The most pronounced anticonvulsant effects were observed in Pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-kindled rats although there was also an effect on amygdala-kindled and neocortically-kindled rats.[10] Vinpocetine has also been shown to abolish [3H]Glu release after in vivo exposure to 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) which suggests an important mechanism for vinpocetine anticonvulsant activity.[11]

Vinpocetine has been investigated in animal models as a potential anti-inflammatory agent.[12] [13] Vinpocetine inhibits the up-regulation of NF-κB by TNFα in various cell tests. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction also shows that it reduced the TNFα-induced expression of the mRNA of proinflammatory molecules such as interleukin-1 beta, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1). In mice, vinpocetine reduced lipopolysaccharide inoculation induced polymorphonuclear neutrophil infiltration into the lung.[12][13]

Mechanism of action

Vinpocetine acts as a phosphodiesterase (PDE) type-1 inhibitor in isolated rabbit aorta,[14] Independent of vinpocetine's action on PDE, vinpocetine inhibits IKK preventing IκB degradation and the following translocation of NF-κB to the cell nucleus.[12][13]

Increases in neuronal levels of DOPAC, a metabolic breakdown product of dopamine, have been shown to occur in striatal isolated nerve endings as a result of exposure to vinpocetine.[15] Such an effect is consistent with the biogenic pharmacology of reserpine, a structural relative of vinpocetine.[15] However, this effect tends to be reversible upon cessation of vinpocetine administration, with full remission typically occurring within 3–4 weeks.

Side effects

Vinpocetine is generally well-tolerated in humans.[16][unreliable medical source?] No serious side effects have thus far been noted in clinical trials,[17][unreliable medical source?] although none of these trials were long-term.[9] Some users have reported headaches, especially at doses above 15 milligrams per day, as well as occasional upset stomach. The safety of vinpocetine in pregnant women has not been evaluated. Vinpocetine has been implicated in one case to induce agranulocytosis,[18][unreliable medical source?] a serious condition in which granulocytes are markedly decreased. Some people have anecdotally noted that their continued use of vinpocetine reduces immune function. Commission E warned that vinpocetine reduced immune function could cause apoptosis (cellular death) in the long term.[19]

References

- ^ Lörincz C, Szász K, Kisfaludy L (1976). "The synthesis of ethyl apovincaminate". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 26 (10a): 1907. PMID 1037211.

- ^ Schmitt, Rick (January 12, 2017). "Marketers exploit the aged with unproven brain-health claims". Newsweek. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ Hank, Schulz. "eligible to be marketed as dietary supplement under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA)". NutraIngredients. William Reed Business Media, England. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ "FDA Concludes Vinpocetine Ineligible as a Dietary Ingredient". Nutraceuticals World. Rodman Media. September 20, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Szilágyi, G. Z.; Nagy, Z. N.; Balkay, L. S.; Boros, I. N.; Emri, M. S.; Lehel, S.; Márián, T. Z.; Molnár, T. S.; Szakáll, S.; Trón, L.; Bereczki, D. N.; Csiba, L. S.; Fekete, I. N.; Kerényi, L.; Galuska, L. S.; Varga, J. Z.; Bönöczk, P. T.; Vas, Á. M.; Gulyás, B. Z. (2005). "Effects of vinpocetine on the redistribution of cerebral blood flow and glucose metabolism in chronic ischemic stroke patients: A PET study". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 229–230: 275–284. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2004.11.053. PMID 15760651.

- ^ Dézsi, L.; Kis-Varga, I.; Nagy, J.; Komlódi, Z.; Kárpáti, E. (2002). "Neuroprotective effects of vinpocetine in vivo and in vitro. Apovincaminic acid derivatives as potential therapeutic tools in ischemic stroke". Acta pharmaceutica Hungarica. 72 (2): 84–91. PMID 12498034.

- ^ "Vinpocetine. Monograph" (PDF). Alternative Medicine Review. 7 (3): 240–3. 2002. PMID 12126465.

- ^ McDaniel MA, Maier SF, Einstein GO (2003). "'Brain-specific' nutrients: a memory cure?". Nutrition. 19 (11–12): 957–75. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(03)00024-8. PMID 14624946.

- ^ a b Szatmari SZ, Whitehouse PJ (2003). Szatmári, Szabolcs (ed.). "Vinpocetine for cognitive impairment and dementia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD003119. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003119. PMID 12535455.

- ^ Schmidt, J (1990). "Comparative studies on the anticonvulsant effectiveness of nootropic drugs in kindled rats". Biomedica biochimica acta. 49 (5): 413–9. PMID 2271012.

- ^ Sitges, M; Sanchez-Tafolla, BM; Chiu, LM; Aldana, BI; Guarneros, A (2011). "Vinpocetine inhibits glutamate release induced by the convulsive agent 4-aminopyridine more potently than several antiepileptic drugs". Epilepsy research. 96 (3): 257–66. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.06.006. PMID 21737246.

- ^ a b c Jeon, K. -I.; Xu, X.; Aizawa, T.; Lim, J. H.; Jono, H.; Kwon, D. -S.; Abe, J. -I.; Berk, B. C.; Li, J. -D.; Yan, C. (2010). "Vinpocetine inhibits NF- B-dependent inflammation via an IKK-dependent but PDE-independent mechanism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (21): 9795–9800. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.9795J. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914414107. PMC 2906898. PMID 20448200.

- ^ a b c Medina, A. E. (2010). "Vinpocetine as a potent antiinflammatory agent". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (22): 9921–9922. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.9921M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005138107. PMC 2890434. PMID 20495091.

- ^ Hagiwara M, Endo T, Hidaka H (1984). "Effects of vinpocetine on cyclic nucleotide metabolism in vascular smooth muscle". Biochemical Pharmacology. 33 (3): 453–7. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(84)90240-5. PMID 6322804.

- ^ a b Trejo F, Nekrassov V, Sitges M (2001). "Characterization of vinpocetine effects on DA and DOPAC release in striatal isolated nerve endings". Brain Research. 909 (1–2): 59–67. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02621-X. PMID 11478921.

- ^ "Is Vinpocetine the Answer to Brain Fog, Cognitive and Memory Problems?". about.com. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ^ "Vinpocetine Side Effects and Warnings". foundhealth. Retrieved 2011-07-02.

- ^ Shimizu Y, Saitoh K, Nakayama M, et al. Agranulocytosis induced by vinpocetine. Medicine Online, Retrieved March 08, 2008.

- ^ The Complete German Commission E Monographs, Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines, 1st ed. 1998, Integrative Medicine Communications, pub; Bk&CD-Rom edition, 1999.[page needed]