Trumpism: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

J JMesserly (talk | contribs) Sections and subsection moved so that they are grouped with similar content. All text ought to be present, though in a new location. Some rewording of section titles. Adjustments to Karen Jones Trust paragraph. |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

{{nationalism sidebar<!--|related concepts-->}} |

{{nationalism sidebar<!--|related concepts-->}} |

||

{{populism sidebar<!--|related topics-->}} |

{{populism sidebar<!--|related topics-->}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

'''Trumpism''' is a term for the [[political ideology]], style of [[governance]],{{sfn|Katzenstein|2019}} [[political movement]] and set of mechanisms for acquiring and keeping power that are associated with [[Donald Trump]], and his [[political base]].{{sfn|Reicher|Haslam|2016}}{{sfn|Dean|Altemeyer|2020|p=11}} Though trumpism is sufficiently complex to overwhelm any single framework of analysis,{{sfn|Gordon|2018|p=68}} it has been called an [[American politics|American political]] variant of the [[Far-right politics|far-right]]{{sfn|Lowndes|2019}}{{sfn|Bennhold|2020}} and of the [[Right-wing populism|national-populist]] and [[Neo-nationalism|neo-nationalist]] sentiment seen in multiple nations worldwide{{sfn|Isaac|2017}} from the late 2010s to the early 2020s. Some have deemed Trumpism as [[Fascism in North America#United_States|akin to fascism]].{{sfn|Kagan|2016}}{{sfn|McGaughey|2018}} Most historians argue that this is an inaccurate use of the term, pointing out that while there are parallels there are also important dissimilarities.{{sfn|Evans|2021}}{{sfn|Weber|2021}} The label "Trumpism" has been applied to conservative-nationalist and national-populist movements in other Western democracies. |

'''Trumpism''' is a term for the [[political ideology]], style of [[governance]],{{sfn|Katzenstein|2019}} [[political movement]] and set of mechanisms for acquiring and keeping power that are associated with [[Donald Trump]], and his [[political base]].{{sfn|Reicher|Haslam|2016}}{{sfn|Dean|Altemeyer|2020|p=11}} Though trumpism is sufficiently complex to overwhelm any single framework of analysis,{{sfn|Gordon|2018|p=68}} it has been called an [[American politics|American political]] variant of the [[Far-right politics|far-right]]{{sfn|Lowndes|2019}}{{sfn|Bennhold|2020}} and of the [[Right-wing populism|national-populist]] and [[Neo-nationalism|neo-nationalist]] sentiment seen in multiple nations worldwide{{sfn|Isaac|2017}} from the late 2010s to the early 2020s. Some have deemed Trumpism as [[Fascism in North America#United_States|akin to fascism]].{{sfn|Kagan|2016}}{{sfn|McGaughey|2018}} Most historians argue that this is an inaccurate use of the term, pointing out that while there are parallels there are also important dissimilarities.{{sfn|Evans|2021}}{{sfn|Weber|2021}} The label "Trumpism" has been applied to conservative-nationalist and national-populist movements in other Western democracies. |

||

== |

== Populist themes, sentiments and methods == |

||

Trumpism started its development predominantly during his [[Donald Trump 2016 presidential campaign|2016 presidential campaign]]. It denotes a [[populist]] political method that suggests [[nationalistic]] answers to political, economic, and social problems. These inclinations are refracted into such policy preferences as [[immigration restrictionism]], [[trade protectionism]], [[isolationism]], and opposition to [[entitlement reform]].{{sfn|Continetti|2020}} As a political method, populism is not driven by any particular ideology.{{sfn|de la Torre|Barr|Arato|Cohen|2019|p=6}} Former [[National Security Advisor (United States)|National Security Advisor]] and former close Trump advisor [[John Bolton]] |

Trumpism started its development predominantly during his [[Donald Trump 2016 presidential campaign|2016 presidential campaign]]. It denotes a [[populist]] political method that suggests [[nationalistic]] answers to political, economic, and social problems. These inclinations are refracted into such policy preferences as [[immigration restrictionism]], [[trade protectionism]], [[isolationism]], and opposition to [[entitlement reform]].{{sfn|Continetti|2020}} As a political method, populism is not driven by any particular ideology.{{sfn|de la Torre|Barr|Arato|Cohen|2019|p=6}} Former [[National Security Advisor (United States)|National Security Advisor]] and former close Trump advisor [[John Bolton]] states this is true of Trump, disputing that "Trumpism" even exists in any meaningful philosophical sense, emphasizing that "[t]he man does not have a philosophy. And people can try and draw lines between the dots of his decisions. They will fail."{{sfn|Brewster|2020}} |

||

Writing for the ''Routledge Handbook of Global Populism'' (2019) Olivier Jutel claims, "What Donald Trump reveals is that the various iterations of right-wing American populism have less to do with a programmatic social conservatism or libertarian economics than with enjoyment."{{sfn|Jutel|2019}} Referring to the populism of Trump, sociologist [[Michael Kimmel]] states that it "is not a theory [or] an ideology, it’s an emotion. And the emotion is righteous indignation that the government is screwing 'us'"{{sfn|Kimmel|2017|p=xi}} Kimmel notes that "Trump is an interesting character because he channels all that sense of what I called 'aggrieved entitlement,'"{{sfn|Kimmel|Wade|2018|p=243}} a term Kimmel defines as "that sense that those benefits to which you believed yourself entitled have been snatched away from you by unseen forces larger and more powerful. You feel yourself to be the heir to a great promise, the American Dream, which has turned into an impossible fantasy for the very people who were supposed to inherit it."{{sfn|Kimmel|2017|p=18}} |

Writing for the ''Routledge Handbook of Global Populism'' (2019) Olivier Jutel claims, "What Donald Trump reveals is that the various iterations of right-wing American populism have less to do with a programmatic social conservatism or libertarian economics than with enjoyment."{{sfn|Jutel|2019}} Referring to the populism of Trump, sociologist [[Michael Kimmel]] states that it "is not a theory [or] an ideology, it’s an emotion. And the emotion is righteous indignation that the government is screwing 'us'"{{sfn|Kimmel|2017|p=xi}} Kimmel notes that "Trump is an interesting character because he channels all that sense of what I called 'aggrieved entitlement,'"{{sfn|Kimmel|Wade|2018|p=243}} a term Kimmel defines as "that sense that those benefits to which you believed yourself entitled have been snatched away from you by unseen forces larger and more powerful. You feel yourself to be the heir to a great promise, the American Dream, which has turned into an impossible fantasy for the very people who were supposed to inherit it."{{sfn|Kimmel|2017|p=18}} |

||

| Line 31: | Line 32: | ||

Other contributors to the Routledge Handbook of Populism note that populist leaders rather than being ideology driven are instead pragmatic and opportunistic regarding themes, ideas and beliefs that strongly resonate with their followers.{{sfn|de la Torre|Barr|Arato|Cohen|2019|pp=6, 37, 50, 102, 206}} Exit polling data suggests the campaign was successful at mobilizing the "[[White backlash|white disenfranchised]]",{{sfn|Fuchs|2018|pp=83–84}} the [[American lower class|lower-]] to [[Working class in the United States|working-class]] European-Americans who are experiencing growing [[social inequality]] and who often have stated opposition to the American [[political establishment]]. Ideologically, Trumpism has a [[right-wing populist]] accent.{{sfn|Kuhn|2017}}{{sfn|Serwer|2017}} |

Other contributors to the Routledge Handbook of Populism note that populist leaders rather than being ideology driven are instead pragmatic and opportunistic regarding themes, ideas and beliefs that strongly resonate with their followers.{{sfn|de la Torre|Barr|Arato|Cohen|2019|pp=6, 37, 50, 102, 206}} Exit polling data suggests the campaign was successful at mobilizing the "[[White backlash|white disenfranchised]]",{{sfn|Fuchs|2018|pp=83–84}} the [[American lower class|lower-]] to [[Working class in the United States|working-class]] European-Americans who are experiencing growing [[social inequality]] and who often have stated opposition to the American [[political establishment]]. Ideologically, Trumpism has a [[right-wing populist]] accent.{{sfn|Kuhn|2017}}{{sfn|Serwer|2017}} |

||

===Focus on sentiments=== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

In accounting for Trump's election and ability sustain stable approval ratings among a significant segment of voters, Erika Tucker argues in the book ''Trump and Political Philosophy'' that though all presidential campaigns have strong emotions associated with them, Trump was able to recognize, and then to gain the trust and loyalty of those who, like him felt a particular set of strong emotions about perceived changes in the United States. She notes, "Political psychologist Drew Westen has argued that Democrats are less successful at gauging and responding to affective politics—issues that arouse strong emotional states in citizens."{{sfn|Tucker|2018|p=134}} Scholars from a wide number of fields have argued that particular affective themes and the dynamics of their impact on social media connected followers characterize Trump and his supporters. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Trumpism differs from classical [[Abraham Lincoln]] [[History of the Republican Party (United States)|Republicanism]] in many ways regarding free trade, immigration, equality, checks and balances in federal government, and the separation of church and state.{{sfn|Brazile|2020}} [[Peter J. Katzenstein]] of the [[WZB Berlin Social Science Center]] believes that Trumpism rests on three pillars, namely nationalism, religion and race.{{sfn|Katzenstein|2019}} |

||

| ⚫ | Communications scholar Michael Carpini states that "Trumpism is a culmination of trends that have been occurring for several decades. What we are witnessing is nothing short of a fundamental shift in the relationships between journalism, politics, and democracy." Among the shifts, Carpini identifies "the collapsing of the prior [media] regime’s presumed and enforced distinctions between news and entertainment." {{sfn|Carpini|2018|pp=18-19}} Examining Trump's use of media for the book ''Language in the Trump Era'', communications professor Marco Jacquemet writes that "It’s an approach that, like much of the rest of Trump’s ideology and policy agenda, assumes (correctly, it appears) that his audiences care more about shock and entertainment value in their media consumption than almost anything else."{{sfn|Jacquemet|2020|p=187}} The perspective is shared among other communication academics, with Plasser & Ulram (2003) describing a media logic which emphasizes “personalization . . . a political star system . . . [and] sports based dramatization”{{sfn|Plasser|Ulram|2003}} and Olivier Jutel noting that "Donald Trump’s celebrity status and reality-TV rhetoric of “winning” and “losing” corresponds perfectly to these values," asserting that "Fox News and conservative personalities from [[Rush Limbaugh]], [[Glenn Beck]] and [[Alex Jones]] do not simply represent a new political and media voice but embody the convergence of politics and media in which affect and enjoyment are the central values of media production."{{sfn|Jutel|2019|pp=249,255}} |

||

| ⚫ | Studying Trump's use of social media, anthropologist Jessica Johnson finds that social emotional pleasure plays a central role writing, "Rather than finding accurate news meaningful, Facebook users find the affective pleasure of connectivity addictive, whether or not the information they share is factual, and that is how communicative capitalism captivates subjects as it holds them captive."{{sfn|Johnson|2018}} Looking back at the world prior to social media, communications researcher [[Brian L. Ott]] writes, |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | {{blockquote|I’m nostalgic for the world of television that Postman (1985) argued, produced the “least well-informed people in the Western world” by packaging news as entertainment (pp. 106–107).{{sfn|Postman|2005|p=106}} Twitter is producing the most self-involved people in history by treating everything one does or thinks as newsworthy. Television may have assaulted journalism, but Twitter killed it.{{sfn|Ott|2017|p=66}}}} |

||

| ⚫ | Commenting on Trump's support among Fox News viewers, Hofstra communications college dean Mark Lukasiewicz has a similar perspective writing, "[[Tristan Harris]] famously said that social networks are about '[[Self-affirmation|affirmation]], not information' — and the same can be said about cable news, especially in prime time."{{sfn|Beer|2021}} |

||

| ⚫ | At the 2021 [[Conservative Political Action Conference|CPAC]] conference, Trump gave his own definition of what defines Trumpism: {{Blockquote|"What it means is great deals.. Like the [[USMCA]] replacement of the horrible [[North American Free Trade Agreement|NAFTA]]{{nbs}}... It means low taxes and eliminated job killing regulations{{nbs}}... It means strong borders, but people coming into our country based on a system of merit{{nbs}}... it means no riots in the streets{{nbs}}... It means law enforcement{{nbs}}... It means very strong protection for the second amendment and the right to keep and bear arms{{nbs}}... it means a strong military and taking care of our vets."{{sfn|Vallejo|2021}}{{sfn|Henninger|2021}}}} |

||

| ⚫ | Hochschild's perspective on the relationship between Trump supporters and their preferred sources of information- whether social media friends or news and commentary stars, is that they are trusted due to the affective bond they have with them. As media scholar Daniel Kreiss summarizes Hochschild, "Trump, along with Fox News, gave these strangers in their own land the hope that they would be restored to their rightful place at the center of the nation, and provided a very real emotional release from the fetters of political correctness that dictated they respect people of color, lesbians and gays, and those of other faiths{{nbs}}… that the network’s personalities share the same 'deep story' of political and social life, and therefore they learn from them 'what to feel afraid, angry, and anxious about.'" From Kreiss's account of conservative personalities and media, information became less important than providing a sense of familial bonding, where "family provides a sense of identity, place, and belonging; emotional, social, and cultural support and security; and gives rise to political and social affiliations and beliefs."{{sfn|Kreiss|2018|pp=93,94}} Hochschild gives the example of one woman who explains the familial bond of trust with the star personalities. "[[Bill O'Reilly (political commentator)|Bill O’Reilly]] is like a steady, reliable dad. [[Sean Hannity]] is like a difficult uncle who rises to anger too quickly. [[Megyn Kelly]] is like a smart sister. Then there’s [[Greta Van Susteren]]. And [[Juan Williams]], who came over from NPR, which was too left for him, the adoptee. They’re all different, just like in a family."{{sfn|Hochschild|2016|p=126}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The roots of Trumpism in the United States can be traced to the [[Jacksonian era]] according to scholars [[Walter Russell Mead]],{{sfn|Glasser|2018}} Peter Katzenstein{{sfn|Katzenstein|2019}} and Edwin Kent Morris.{{sfn|Morris|2019|p=20}} [[Eric Rauchway]] says: "Trumpism—[[Nativism (politics)|nativism]] and [[white supremacy]]—has deep roots in American history. But Trump himself put it to new and malignant purpose."{{sfn|Lyall|2021}} |

||

| ⚫ | Media scholar Olivier Jutel focuses on the neoliberal privatization and market segmentation of the public square, noting that, "Affect is central to the brand strategy of Fox which imagined its journalism not in terms of servicing the rational citizen in the public sphere but in 'craft[ing] intensive relationships with their viewers' (Jones, 2012: 180) in order to sustain audience share across platforms." In this segmented market, Trump "offers himself as an ego-ideal to an individuated public of enjoyment that coalesce around his media brand as part of their own performance of identity." Jutel cautions that it is not just conservative media companies that benefit from the transformation of news media to conform to values of spectacle and reality-TV drama. "Trump is a definitive product of [[Mediatization (media)|mediatized]] politics providing the spectacle that drives ratings and affective media consumption, either as part of his populist movement or as the liberal resistance." {{sfn|Jutel|2019|pp=250,256}} |

||

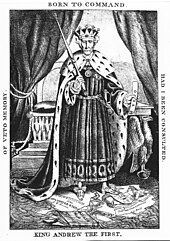

| ⚫ | [[Andrew Jackson]]'s followers felt he was one of them, enthusiastically supporting his defiance of [[politically correct]] norms of the nineteenth century and even constitutional law when they stood in the way of public policy popular among his followers. Jackson ignored the [[U.S. Supreme Court]] ruling in ''[[Worcester v. Georgia#Enforcement|Worcester v. Georgia]]'' and initiated the forced [[Cherokee removal]] from their treaty protected lands to benefit white locals at the cost of between 2,000 and 6,000 dead Cherokee men, women, and children. Notwithstanding such cases of Jacksonian inhumanity, Mead's view is that Jacksonianism provides the historical precedent explaining the movement of followers of Trump, marrying grass-roots disdain for elites, deep suspicion of overseas entanglements, and obsession with American power and sovereignty, acknowledging that it has often been a [[xenophobic]], "whites only" political movement. Mead thinks this "hunger in America for a Jacksonian figure" drives followers towards Trump but cautions that historically "he is not the second coming of Andrew Jackson," observing that "his proposals tended to be pretty vague and often contradictory," exhibiting the common weakness of newly elected populist leaders, commenting early in his presidency that "now he has the difficulty of, you know, 'How do you govern?'"{{sfn|Glasser|2018}} |

||

| ⚫ | Researchers give differing emphasis to which emotions are important to followers. Michael Richardson argues in the Journal of Media and Cultural Studies that "affirmation, amplification and circulation of disgust is one of the primary affective drivers of Trump’s political success." Richardson agrees with Ott about the "entanglement of Trumpian affect and social media crowds" who seek "affective affirmation, confirmation and amplification. Social media postings of crowd experiences accumulate as ‘archives of feelings’ that are both dynamic in nature and affirmative of social values (Pybus 2015, 239)."{{sfn|Richardson|2017}}{{sfn|Pybus|2015|p=239}} |

||

| ⚫ | Morris agrees with Mead, locating Trumpism's roots in the Jacksonian era from 1828 to 1848 under the presidencies of Jackson, [[Martin Van Buren]] and [[James K. Polk]]. On Morris's view, Trumpism also shares similarities with the post-World War I faction of the [[Progressivism in the United States|progressive movement]] which catered to a conservative populist recoil from the looser morality of the cosmopolitan cites and America's changing racial complexion.{{sfn|Morris|2019|p=20}} In his book ''[[The Age of Reform]]'' (1955), historian [[Richard Hofstadter]] identified this faction's emergence when "a large part of the Progressive-Populist tradition had turned sour, became illiberal and ill-tempered."{{sfn|Greenberg|2016}} |

||

| ⚫ | Using Trump as an example, [[Trust (social science) |social trust]] expert Karen Jones follows philosopher [[Annette Baier]] in claiming that masters of the art of creating trust and distrust are criminals and populist politicians. On this view, it is not moral philosphers who are the experts at discerning different forms of trust, but members of this class of practitioners who "show a masterful appreciation of the ways in which certain emotional states drive out trust and replace it with distrust."{{sfn|Jones|2019}} Jones sees Trump as an exemplar of this class who recognize that fear and contempt are powerful tools that can reorient networks of trust and distrust in social networks in order to alter how a potential supporter "interprets the words, deeds, and motives of the other."{{notetag|Jones elaborates on her view that trust is central to epistemology in a chapter entitled "Trusting Interpretations" which appeared in the book "Trust- Analytic and Applied Perspectives."{{sfn| Jones|2013}}}} She points out that the tactic is used globally writing, "A core strategy of Donald Trump, both as candidate and president, has been to manufacture fear and contempt towards some undocumented migrants (among other groups). This strategy of manipulating fear and contempt has gone global, being replicated with minor local adjustment in Australia, Austria, Hungary, Poland, Italy and the United Kingdom. "{{sfn|Jones|2019}} |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:"America First" ad from Chicago mayoral election, 1927.jpg|thumb|upright=0.75|1927 "[[America First (policy)|America First]]" political advertisement advocating isolationism and establishing emotional ties of [[1927 Chicago mayoral election|1927 Chicago mayoral]] candidate [[William Hale Thompson]] with his Irish supporters by vilifying the United Kingdom, a close ally]] |

||

| ⚫ | Prior to World War II, conservative themes of Trumpism were expressed in the [[America First Committee|America First]] movement in the early 20th century, and after World War II were attributed to a [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican Party]] faction known as the [[Old Right (United States)|Old Right]]. By the 1990s, it became referred to as the [[paleoconservative]] movement, which according to Morris has now been re-branded as Trumpism.{{sfn|Morris|2019|p=21}} [[Leo Löwenthal]]'s book ''[[Prophets of Deceit]]'' (1949) summarized common narratives expressed in the post-World War II period of this populist fringe, specifically examining American [[demagogues]] of the period when modern mass media was married with the same destructive style of politics that historian Charles Clavey thinks Trumpism represents. According to Clavey, Löwenthal's book best explains the enduring appeal of Trumpism and offers the most striking historical insights into the movement.{{sfn|Clavey|2020}} |

||

| ⚫ | Writing in ''[[The New Yorker]]'', journalist [[Nicholas Lemann]] states the post-war Republican Party ideology of [[fusionism]], a fusion of pro-business party establishment with [[Nativism in the United States|nativist]], [[United States non-interventionism|isolationist]] elements who gravitated towards the Republican and not the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]], later joined by Christian evangelicals "alarmed by the rise of secularism", was made possible by the [[Cold War]] and the "mutual fear and hatred of the spread of Communism". An article in Politco has referred to Trumpism as "[[McCarthyism]] on steroids".{{sfn|MacWilliams|2020}}{{sfn|Lemann|2020}} |

||

| ⚫ | Championed by [[William F. Buckley Jr.]] and brought to fruition by [[Ronald Reagan]] in 1980, the fusion lost its glue with the [[collapse of the Soviet Union]], which was followed by a growth of [[Income inequality in the United States|inequality]] and [[globalization]] that "created major discontent among middle and low income whites" within and without the Republican Party. After the [[2012 United States presidential election]] saw the defeat of [[Mitt Romney]] by [[Barack Obama]], the party establishment embraced an "autopsy" report, titled the Growth and Opportunity Project, which "called on the Party to reaffirm its identity as pro-market, government-skeptical, and ethnically and culturally inclusive." Ignoring the findings of the report and the party establishment in his campaign, Trump was "opposed by more officials in his own Party [...] than any Presidential nominee in recent American history," but at the same time he won "more votes" in the Republican primaries than any previous presidential candidate. By 2016, "people wanted somebody to throw a brick through a plate-glass window", in the words of political analyst [[Karl Rove]].{{sfn|Lemann|2020}} His success in the party was such that an October 2020 poll found 58% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents surveyed considered themselves supporters of Trump rather than the Republican Party.{{sfn|Peters|2020}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

=== Right-wing authoritarian populism === |

=== Right-wing authoritarian populism === |

||

| Line 84: | Line 80: | ||

Some, such as conservative [[Orthodoxy#Christianity|Orthodox Christian]] writer [[Rod Dreher]], and theologian [[Michael Horton (theologian) | Michael Horton]] have argued that participants in the march were engaging in "Trump worship", akin to [[idolatry]].{{sfn|Dreher|2020}}{{sfn|Lewis|2020}} In the ''[[National Review]]'', Cameron Hilditch described the movement as such:{{cquote|A toxic ideological cocktail of grievance, paranoia, and self-exculpatory rage was on display at the "Jericho March"{{nbs}}... Their aim was to "[[stop the steal]]" of the presidential election, to prepare patriots for battle against a "[[World government|One-World Government]]", and [[My Pillow|to sell pillows at a 25 percent discount]].{{nbs}}... In fact, there was a strange impression given throughout the event that attendees believe Christianity is, in some sense, [[consubstantial]] with American nationalism. It was as if a new and improved Holy Trinity of "Father, Son, and [[Uncle Sam]]" had taken the place of the old and outmoded [[Nicene Creed|Nicene version]]. When [[Eric Metaxas]], the partisan radio host and emcee for the event, first stepped on stage, he wasn't greeted with psalm-singing or with hymns of praise to the Holy Redeemer, but with chants of "USA! USA!" In short, the Jericho rally was a worrying example of how Christianity can be twisted and drafted into the service of a political ideology.{{sfn|Hilditch|2020}} |

Some, such as conservative [[Orthodoxy#Christianity|Orthodox Christian]] writer [[Rod Dreher]], and theologian [[Michael Horton (theologian) | Michael Horton]] have argued that participants in the march were engaging in "Trump worship", akin to [[idolatry]].{{sfn|Dreher|2020}}{{sfn|Lewis|2020}} In the ''[[National Review]]'', Cameron Hilditch described the movement as such:{{cquote|A toxic ideological cocktail of grievance, paranoia, and self-exculpatory rage was on display at the "Jericho March"{{nbs}}... Their aim was to "[[stop the steal]]" of the presidential election, to prepare patriots for battle against a "[[World government|One-World Government]]", and [[My Pillow|to sell pillows at a 25 percent discount]].{{nbs}}... In fact, there was a strange impression given throughout the event that attendees believe Christianity is, in some sense, [[consubstantial]] with American nationalism. It was as if a new and improved Holy Trinity of "Father, Son, and [[Uncle Sam]]" had taken the place of the old and outmoded [[Nicene Creed|Nicene version]]. When [[Eric Metaxas]], the partisan radio host and emcee for the event, first stepped on stage, he wasn't greeted with psalm-singing or with hymns of praise to the Holy Redeemer, but with chants of "USA! USA!" In short, the Jericho rally was a worrying example of how Christianity can be twisted and drafted into the service of a political ideology.{{sfn|Hilditch|2020}} |

||

=== |

=== Methods of persuasion === |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In terms of foreign policy in the sense of Trump's "[[America First (policy)|America First]]", [[unilateralism]] is preferred to a multilateral policy and national interests are particularly emphasized, especially in the context of economic treaties and alliance obligations.{{sfn|Rudolf|2017}}{{sfn|Assheuer|2018}} Trump has shown a disdain for traditional American allies such as Canada as well as transatlantic partners [[NATO]] and the [[European Union]].{{sfn|Smith|Townsend|2018}}{{sfn|Tharoor|2018}} Conversely, Trump has shown sympathy for [[autocratic]] rulers, especially for the Russian president [[Vladimir Putin]], whom Trump often praised even before taking office,{{sfn|Diamond|2016}} and during the [[2018 Russia–United States summit]].{{sfn|Kuhn|2018}} The "America First" foreign policy includes promises by Trump to end American involvement in foreign wars, notably in the [[United States foreign policy in the Middle East|Middle East]], while also issuing tighter foreign policy through [[United States sanctions against Iran|sanctions against Iran]], among other countries.{{sfn|Zengerle|2019}}{{sfn|Wintour|2020}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In terms of economic policy, Trumpism "promises new jobs and more domestic investment".{{sfn|Harwood|2017}} Trump's hard line against export surpluses of American trading partners has led to a tense situation in 2018 with mutually imposed punitive tariffs between the United States on the one hand and the European Union and China on the other.{{sfn|Partington|2018}} Trump secures the support of his political base with a policy that strongly emphasizes [[Neo-nationalism|nationalism]] and [[criticism of globalization]].{{sfn|Thompson|2017}} While the book ''Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America'' suggested that Trump [[Radicalization|"Radicalized]] economics" to his base of white working to middle class voters by the promoting the idea that "undeserving [minority] groups are getting ahead while their group is being left behind."{{sfn|O'Connor|2020}} |

||

== Non-ideological aspects == |

|||

| ⚫ | Journalist Elaina Plott suggests ideology is not as important as other characteristics of Trumpism.{{notetag|name=Plott1}} Plott cites political analyst [[Jeff Roe]], who observed Trump "understood" and acted on the trend among Republican voters to be "less ideological" but "more polarized". Republicans are now more willing to accept policies like government mandated health care coverage for pre-existing conditions or trade tariffs, formerly disdained by conservatives as burdensome government regulations. At the same time, strong avowals of support for Trump and aggressive partisanship have become part of Republican election campaigning—in at least some parts of America—reaching down even to non-partisan campaigns for local government which formerly were collegial and issue-driven.{{sfn|Plott|2020}} Research by political scientist [[Marc Hetherington]] and others has found Trump supporters tend to share a "worldview" transcending political ideology, agreeing with statements like "the best strategy is to play hardball, even if it means being unfair." In contrast, those who agree with statements like "cooperation is the key to success" tend to prefer Trump's adversary former Republican presidential candidate [[Mitt Romney]].{{sfn|Plott|2020}} |

||

| ⚫ | Journalist [[Nicholas Lemann]] notes the disconnect between some of Trump's campaign rhetoric and promises, and what he accomplished once in office—and the fact that the difference seemed to bother very few supporters. The campaign themes being anti-[[free-trade]] nationalism, defense of Social Security, attacks on big business, "building that big, beautiful wall and making Mexico pay for it", repealing Obama's [[Affordable Care Act]], a trillion dollar infrastructure-building program. The accomplishments being "conventional" Republican policies and legislation—substantial tax cuts, rollbacks of federal regulations, and increases in military spending.{{sfn|Lemann|2020}} Many have noted that instead of the [[Republican National Convention]] issuing the customary "platform" of policies and promises for the 2020 campaign, it offered a "one-page resolution" stating that the party was not "going to have a new platform, but instead [...] 'has and will continue to enthusiastically support the president's America-first agenda.'"{{notetag|name=Zurcher1}}{{sfn|Zurcher|2020}} |

||

== Methods of persuasion == |

|||

{{further|Truthiness|Personal branding|Big lie}} |

{{further|Truthiness|Personal branding|Big lie}} |

||

| Line 122: | Line 105: | ||

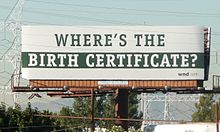

The absolutist rhetoric employed heavily favors crowd reaction over veracity, with a large number of lies which Trump presents as facts.{{sfn|Kessler|Kelly|2018}} Drawing on [[Harry G. Frankfurt]]'s book ''[[On Bullshit]]'', political science professor Matthew McManus points out that it is more precise to identify Trump as a bullshitter whose sole interest is to persuade, and not a liar, (e.g. [[Richard Nixon]]) who takes the power of truth seriously and so deceitfully attempts to conceal it. Trump by contrast is indifferent to the truth or unaware of it.{{sfn|McManus|2020|p=178}} Unlike conventional lies of politicians exaggerating their accomplishments, Trump's lies are egregious, making lies about easily verifiable facts. At one rally Trump stated his father "came from Germany", even though [[Fred Trump]] was born in New York City. His lying is not new, as Trump told ''[[The New York Times]]'' to be Swedish in 1976. At a Michigan rally in December 1990, Trump presented 179 statements as fact, more than one a minute and 67 percent of them were false or misleading. Trump is not shy about lying to more sophisticated audiences, but he is surprised when crowd reaction is not what he expected, as was the case when leaders at the 2018 [[United Nations General Assembly]] burst into laughter at his boast that he had accomplished more in his first two years than any other United States president. Visibly startled, Trump responded to the audience: "I didn't expect that reaction."{{sfn|Kessler|Rizzo|Kelly|2020|pp=16, 24, 46, 47|loc=(ebook edition)}} Trump lies about the trivial, claiming that there was no rain on the day of his inauguration when in fact it did rain, making the grandiose Big Lies such as claiming that Obama founded [[ISIS]], or promoting the [[birther movement]], a conspiracy theory believing Obama was born in Kenya, not Hawaii.{{sfn|Pfiffner|2020|pp=17–40}} Connolly points to the similarities of such reality-bending statements with fascist and post Soviet techniques of propaganda including [[Kompromat]] (scandalous material), stating that "Trumpian persuasion draws significantly upon the repetition of Big Lies."{{sfn|Connolly|2017|pp=18–19}} |

The absolutist rhetoric employed heavily favors crowd reaction over veracity, with a large number of lies which Trump presents as facts.{{sfn|Kessler|Kelly|2018}} Drawing on [[Harry G. Frankfurt]]'s book ''[[On Bullshit]]'', political science professor Matthew McManus points out that it is more precise to identify Trump as a bullshitter whose sole interest is to persuade, and not a liar, (e.g. [[Richard Nixon]]) who takes the power of truth seriously and so deceitfully attempts to conceal it. Trump by contrast is indifferent to the truth or unaware of it.{{sfn|McManus|2020|p=178}} Unlike conventional lies of politicians exaggerating their accomplishments, Trump's lies are egregious, making lies about easily verifiable facts. At one rally Trump stated his father "came from Germany", even though [[Fred Trump]] was born in New York City. His lying is not new, as Trump told ''[[The New York Times]]'' to be Swedish in 1976. At a Michigan rally in December 1990, Trump presented 179 statements as fact, more than one a minute and 67 percent of them were false or misleading. Trump is not shy about lying to more sophisticated audiences, but he is surprised when crowd reaction is not what he expected, as was the case when leaders at the 2018 [[United Nations General Assembly]] burst into laughter at his boast that he had accomplished more in his first two years than any other United States president. Visibly startled, Trump responded to the audience: "I didn't expect that reaction."{{sfn|Kessler|Rizzo|Kelly|2020|pp=16, 24, 46, 47|loc=(ebook edition)}} Trump lies about the trivial, claiming that there was no rain on the day of his inauguration when in fact it did rain, making the grandiose Big Lies such as claiming that Obama founded [[ISIS]], or promoting the [[birther movement]], a conspiracy theory believing Obama was born in Kenya, not Hawaii.{{sfn|Pfiffner|2020|pp=17–40}} Connolly points to the similarities of such reality-bending statements with fascist and post Soviet techniques of propaganda including [[Kompromat]] (scandalous material), stating that "Trumpian persuasion draws significantly upon the repetition of Big Lies."{{sfn|Connolly|2017|pp=18–19}} |

||

=== More combative, less ideological base === |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Journalist Elaina Plott suggests ideology is not as important as other characteristics of Trumpism.{{notetag|name=Plott1}} Plott cites political analyst [[Jeff Roe]], who observed Trump "understood" and acted on the trend among Republican voters to be "less ideological" but "more polarized". Republicans are now more willing to accept policies like government mandated health care coverage for pre-existing conditions or trade tariffs, formerly disdained by conservatives as burdensome government regulations. At the same time, strong avowals of support for Trump and aggressive partisanship have become part of Republican election campaigning—in at least some parts of America—reaching down even to non-partisan campaigns for local government which formerly were collegial and issue-driven.{{sfn|Plott|2020}} Research by political scientist [[Marc Hetherington]] and others has found Trump supporters tend to share a "worldview" transcending political ideology, agreeing with statements like "the best strategy is to play hardball, even if it means being unfair." In contrast, those who agree with statements like "cooperation is the key to success" tend to prefer Trump's adversary former Republican presidential candidate [[Mitt Romney]].{{sfn|Plott|2020}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Journalist [[Nicholas Lemann]] notes the disconnect between some of Trump's campaign rhetoric and promises, and what he accomplished once in office—and the fact that the difference seemed to bother very few supporters. The campaign themes being anti-[[free-trade]] nationalism, defense of Social Security, attacks on big business, "building that big, beautiful wall and making Mexico pay for it", repealing Obama's [[Affordable Care Act]], a trillion dollar infrastructure-building program. The accomplishments being "conventional" Republican policies and legislation—substantial tax cuts, rollbacks of federal regulations, and increases in military spending.{{sfn|Lemann|2020}} Many have noted that instead of the [[Republican National Convention]] issuing the customary "platform" of policies and promises for the 2020 campaign, it offered a "one-page resolution" stating that the party was not "going to have a new platform, but instead [...] 'has and will continue to enthusiastically support the president's America-first agenda.'"{{notetag|name=Zurcher1}}{{sfn|Zurcher|2020}} |

||

| ⚫ | An alternate non ideological circular definition of Trumpism widely held among Trump activists was reported by Saagar Enjeti, chief Washington correspondent for [[The Hill (newspaper)|The Hill]] who stated, "I was frequently told by people wholly within the [[Make America Great Again|MAGA]] camp that trumpism meant anything Trump does, ergo nothing that he did is a departure from trumpism."{{sfn|Enjeti|2021}} |

||

===Ideological Themes === |

|||

| ⚫ | Trumpism differs from classical [[Abraham Lincoln]] [[History of the Republican Party (United States)|Republicanism]] in many ways regarding free trade, immigration, equality, checks and balances in federal government, and the separation of church and state.{{sfn|Brazile|2020}} [[Peter J. Katzenstein]] of the [[WZB Berlin Social Science Center]] believes that Trumpism rests on three pillars, namely nationalism, religion and race.{{sfn|Katzenstein|2019}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | At the 2021 [[Conservative Political Action Conference|CPAC]] conference, Trump gave his own definition of what defines Trumpism: {{Blockquote|"What it means is great deals.. Like the [[USMCA]] replacement of the horrible [[North American Free Trade Agreement|NAFTA]]{{nbs}}... It means low taxes and eliminated job killing regulations{{nbs}}... It means strong borders, but people coming into our country based on a system of merit{{nbs}}... it means no riots in the streets{{nbs}}... It means law enforcement{{nbs}}... It means very strong protection for the second amendment and the right to keep and bear arms{{nbs}}... it means a strong military and taking care of our vets."{{sfn|Vallejo|2021}}{{sfn|Henninger|2021}}}} |

||

== Social psychology == |

== Social psychology == |

||

| Line 161: | Line 158: | ||

== Media and pillarization == |

== Media and pillarization == |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Communications scholar Michael Carpini states that "Trumpism is a culmination of trends that have been occurring for several decades. What we are witnessing is nothing short of a fundamental shift in the relationships between journalism, politics, and democracy." Among the shifts, Carpini identifies "the collapsing of the prior [media] regime’s presumed and enforced distinctions between news and entertainment." {{sfn|Carpini|2018|pp=18-19}} Examining Trump's use of media for the book ''Language in the Trump Era'', communications professor Marco Jacquemet writes that "It’s an approach that, like much of the rest of Trump’s ideology and policy agenda, assumes (correctly, it appears) that his audiences care more about shock and entertainment value in their media consumption than almost anything else."{{sfn|Jacquemet|2020|p=187}} The perspective is shared among other communication academics, with Plasser & Ulram (2003) describing a media logic which emphasizes “personalization . . . a political star system . . . [and] sports based dramatization”{{sfn|Plasser|Ulram|2003}} and Olivier Jutel noting that "Donald Trump’s celebrity status and reality-TV rhetoric of “winning” and “losing” corresponds perfectly to these values," asserting that "Fox News and conservative personalities from [[Rush Limbaugh]], [[Glenn Beck]] and [[Alex Jones]] do not simply represent a new political and media voice but embody the convergence of politics and media in which affect and enjoyment are the central values of media production."{{sfn|Jutel|2019|pp=249,255}} |

||

| ⚫ | Studying Trump's use of social media, anthropologist Jessica Johnson finds that social emotional pleasure plays a central role writing, "Rather than finding accurate news meaningful, Facebook users find the affective pleasure of connectivity addictive, whether or not the information they share is factual, and that is how communicative capitalism captivates subjects as it holds them captive."{{sfn|Johnson|2018}} Looking back at the world prior to social media, communications researcher [[Brian L. Ott]] writes, |

||

| ⚫ | {{blockquote|I’m nostalgic for the world of television that Postman (1985) argued, produced the “least well-informed people in the Western world” by packaging news as entertainment (pp. 106–107).{{sfn|Postman|2005|p=106}} Twitter is producing the most self-involved people in history by treating everything one does or thinks as newsworthy. Television may have assaulted journalism, but Twitter killed it.{{sfn|Ott|2017|p=66}}}} |

||

| ⚫ | Commenting on Trump's support among Fox News viewers, Hofstra communications college dean Mark Lukasiewicz has a similar perspective writing, "[[Tristan Harris]] famously said that social networks are about '[[Self-affirmation|affirmation]], not information' — and the same can be said about cable news, especially in prime time."{{sfn|Beer|2021}} |

||

| ⚫ | Hochschild's perspective on the relationship between Trump supporters and their preferred sources of information- whether social media friends or news and commentary stars, is that they are trusted due to the affective bond they have with them. As media scholar Daniel Kreiss summarizes Hochschild, "Trump, along with Fox News, gave these strangers in their own land the hope that they would be restored to their rightful place at the center of the nation, and provided a very real emotional release from the fetters of political correctness that dictated they respect people of color, lesbians and gays, and those of other faiths{{nbs}}… that the network’s personalities share the same 'deep story' of political and social life, and therefore they learn from them 'what to feel afraid, angry, and anxious about.'" From Kreiss's account of conservative personalities and media, information became less important than providing a sense of familial bonding, where "family provides a sense of identity, place, and belonging; emotional, social, and cultural support and security; and gives rise to political and social affiliations and beliefs."{{sfn|Kreiss|2018|pp=93,94}} Hochschild gives the example of one woman who explains the familial bond of trust with the star personalities. "[[Bill O'Reilly (political commentator)|Bill O’Reilly]] is like a steady, reliable dad. [[Sean Hannity]] is like a difficult uncle who rises to anger too quickly. [[Megyn Kelly]] is like a smart sister. Then there’s [[Greta Van Susteren]]. And [[Juan Williams]], who came over from NPR, which was too left for him, the adoptee. They’re all different, just like in a family."{{sfn|Hochschild|2016|p=126}} |

||

| ⚫ | Media scholar Olivier Jutel focuses on the neoliberal privatization and market segmentation of the public square, noting that, "Affect is central to the brand strategy of Fox which imagined its journalism not in terms of servicing the rational citizen in the public sphere but in 'craft[ing] intensive relationships with their viewers' (Jones, 2012: 180) in order to sustain audience share across platforms." In this segmented market, Trump "offers himself as an ego-ideal to an individuated public of enjoyment that coalesce around his media brand as part of their own performance of identity." Jutel cautions that it is not just conservative media companies that benefit from the transformation of news media to conform to values of spectacle and reality-TV drama. "Trump is a definitive product of [[Mediatization (media)|mediatized]] politics providing the spectacle that drives ratings and affective media consumption, either as part of his populist movement or as the liberal resistance." {{sfn|Jutel|2019|pp=250,256}} |

||

| ⚫ | Researchers give differing emphasis to which emotions are important to followers. Michael Richardson argues in the Journal of Media and Cultural Studies that "affirmation, amplification and circulation of disgust is one of the primary affective drivers of Trump’s political success." Richardson agrees with Ott about the "entanglement of Trumpian affect and social media crowds" who seek "affective affirmation, confirmation and amplification. Social media postings of crowd experiences accumulate as ‘archives of feelings’ that are both dynamic in nature and affirmative of social values (Pybus 2015, 239)."{{sfn|Richardson|2017}}{{sfn|Pybus|2015|p=239}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

=== Culture industry === |

=== Culture industry === |

||

{{further|Culture industry}} |

{{further|Culture industry}} |

||

| Line 192: | Line 174: | ||

=== Social media === |

=== Social media === |

||

{{further|Social media use by Donald Trump|Group polarization|Collective narcissism}} |

{{further|Social media use by Donald Trump|Group polarization|Collective narcissism}} |

||

Surveying research of how Trumpist communication is well suited to social media, Brian Ott writes that, "commentators who have studied Trump's public discourse have observed speech patterns that correspond closely to what I identified as Twitter's three defining features [Simplicity, impulsivity, and incivility]."{{sfn|Ott|2017|p=63}} Media critic [[Neal Gabler]] has a similar viewpoint writing that "What FDR was to radio and JFK to television, Trump is to Twitter."{{sfn|Gabler| 2016}} Outrage discourse expert Patrick O'Callaghan argues that social media is most effective when it utilizes the particular type of communication which Trump relies on. O'Callaghan notes that sociologist Sarah Sobieraj and political scientist Jeffrey M. Berry almost perfectly described in 2011 the social media communication style used by Trump long before his presidential campaign.{{sfn|O'Callaghan|2020|p=115}} They explained that such discourse {{blockquote|" |

Surveying research of how Trumpist communication is well suited to social media, Brian Ott writes that, "commentators who have studied Trump's public discourse have observed speech patterns that correspond closely to what I identified as Twitter's three defining features [Simplicity, impulsivity, and incivility]."{{sfn|Ott|2017|p=63}} Media critic [[Neal Gabler]] has a similar viewpoint writing that "What FDR was to radio and JFK to television, Trump is to Twitter."{{sfn|Gabler| 2016}} Outrage discourse expert Patrick O'Callaghan argues that social media is most effective when it utilizes the particular type of communication which Trump relies on. O'Callaghan notes that sociologist Sarah Sobieraj and political scientist Jeffrey M. Berry almost perfectly described in 2011 the social media communication style used by Trump long before his presidential campaign.{{sfn|O'Callaghan|2020|p=115}} They explained that such discourse {{blockquote|"[involves] efforts to provoke visceral responses (e.g., anger, righteousness, fear, moral indignation) from the audience through the use of overgeneralizations, sensationalism, misleading or patently inaccurate information, [[ad hominem]] attacks, and partial truths about opponents, who may be individuals, organizations, or entire communities of interest (e.g., progressives or conservatives) or circumstance (e.g., immigrants). Outrage sidesteps the messy nuances of complex political issues in favor of melodrama, misrepresentative exaggeration, mockery, and improbable forecasts of impending doom. Outrage talk is not so much discussion as it is verbal competition, political theater with a scorecard."{{sfn|Sobieraj|Berry|2011|p=20}}}} |

||

Due to Facebook's and Twitter's [[narrowcasting]] environment in which outrage discourse thrives,{{notetag|One of Sobieraj and Berry's key findings was that, "Outrage thrives in a narrowcasting environment."{{sfn|Sobieraj|Berry|2011|p=22}} }} Trump's employment of such messaging at almost every opportunity was from O'Callaghan's account extremely effective because tweets and posts were repeated in viral fashion among like minded supporters, thereby rapidly building a substantial information echo chamber,{{sfn|O'Callaghan|2020|p=116}} a phenomenon [[Cass Sunstein]] identifies as [[group polarization]],{{sfn|Sunstein|2007|p=60}} and other researchers refer to as a kind of self re-enforcing [[homophily]]{{sfn|Massachs|Monti|Morales|Bonchi|2020|p=2}}{{notetag|Homophily is the sociological term corresponding to the saying "Birds of a feather flock together." Pointing to a 2015 [[Pew Research Center]] study revealing that the average facebook user has five politically like-minded friends for every one from the opposing end of the spectrum,{{sfn|Bleiberg |West|2015}} like Massachs et al. (2020), [[Samantha Power]] takes note of the combination of social media and homophily's self-reinforcing impact on our perceived world writing, "The information that comes to us has increasingly been tailored to appeal to our prior prejudices, and it is unlikely to be challenged by the like-minded with whom we interact day-to-day."{{sfn|Power|2018|p=77}} }} |

Due to Facebook's and Twitter's [[narrowcasting]] environment in which outrage discourse thrives,{{notetag|One of Sobieraj and Berry's key findings was that, "Outrage thrives in a narrowcasting environment."{{sfn|Sobieraj|Berry|2011|p=22}} }} Trump's employment of such messaging at almost every opportunity was from O'Callaghan's account extremely effective because tweets and posts were repeated in viral fashion among like minded supporters, thereby rapidly building a substantial information echo chamber,{{sfn|O'Callaghan|2020|p=116}} a phenomenon [[Cass Sunstein]] identifies as [[group polarization]],{{sfn|Sunstein|2007|p=60}} and other researchers refer to as a kind of self re-enforcing [[homophily]]{{sfn|Massachs|Monti|Morales|Bonchi|2020|p=2}}{{notetag|Homophily is the sociological term corresponding to the saying "Birds of a feather flock together." Pointing to a 2015 [[Pew Research Center]] study revealing that the average facebook user has five politically like-minded friends for every one from the opposing end of the spectrum,{{sfn|Bleiberg |West|2015}} like Massachs et al. (2020), [[Samantha Power]] takes note of the combination of social media and homophily's self-reinforcing impact on our perceived world writing, "The information that comes to us has increasingly been tailored to appeal to our prior prejudices, and it is unlikely to be challenged by the like-minded with whom we interact day-to-day."{{sfn|Power|2018|p=77}} }} |

||

Within these information cocoons, it matters little to social media companies whether much of the information spread in such pillarized information silos is false, because as digital culture critic Olivia Solon points out, "the truth of a piece of content is less important than whether it is shared, liked, and monetized."{{sfn|Solon|2016}} |

Within these information cocoons, it matters little to social media companies whether much of the information spread in such pillarized information silos is false, because as digital culture critic Olivia Solon points out, "the truth of a piece of content is less important than whether it is shared, liked, and monetized."{{sfn|Solon|2016}} |

||

Citing Pew Research's survey that found 62% of US adults get their news from social media,{{sfn|Gottfried |Shearer| 2016}} Ott expresses alarm, "since the 'news' content on social media regularly features fake and misleading stories from sources devoid of editorial standards."{{sfn|Ott|2017|p=65}} Media critic [[Alex Ross (music critic)|Alex Ross]] is similarly alarmed, observing, "Silicon Valley monopolies have taken a hands-off, ideologically vacant attitude toward the upswelling of ugliness on the Internet," and that "the failure of Facebook to halt the proliferation of fake news during the |

Citing Pew Research's survey that found 62% of US adults get their news from social media,{{sfn|Gottfried |Shearer| 2016}} Ott expresses alarm, "since the 'news' content on social media regularly features fake and misleading stories from sources devoid of editorial standards."{{sfn|Ott|2017|p=65}} Media critic [[Alex Ross (music critic)|Alex Ross]] is similarly alarmed, observing, "Silicon Valley monopolies have taken a hands-off, ideologically vacant attitude toward the upswelling of ugliness on the Internet," and that "the failure of Facebook to halt the proliferation of fake news during the [Trump vs. Clinton] campaign season should have surprised no one{{nbs}}... Traffic trumps ethics."{{sfn|Ross|2016}} |

||

O'Callaghan's analysis of Trump's use of social media is that "outrage hits an emotional nerve and is therefore grist to the populist’s or the social antagonist’s mill. Secondly, the greater and the more widespread the outrage discourse, the more it has a detrimental effect on [[social capital]]. This is because it leads to mistrust and misunderstanding amongst individuals and groups, to entrenched positions, to a feeling of 'us versus them'. So understood, outrage discourse not only produces extreme and polarising views but also ensures that a cycle of such views continues. (Consider also in this context Wade Robison (2020) on the 'contagion of passion'{{sfn|Robison|2020|p=180}} and Cass Sunstein (2001, pp. 98–136){{notetag|The 2001 reference is to an earlier edition of Sunstein's Republic.com. An updated chapter on cybercascades may be found in his Republic.com 2.0 (2007).{{sfn|Sunstein|2007|pp=46-96}}}} on 'cybercascades'.)"{{sfn|O'Callaghan|2020|p=116}} |

O'Callaghan's analysis of Trump's use of social media is that "outrage hits an emotional nerve and is therefore grist to the populist’s or the social antagonist’s mill. Secondly, the greater and the more widespread the outrage discourse, the more it has a detrimental effect on [[social capital]]. This is because it leads to mistrust and misunderstanding amongst individuals and groups, to entrenched positions, to a feeling of 'us versus them'. So understood, outrage discourse not only produces extreme and polarising views but also ensures that a cycle of such views continues. (Consider also in this context Wade Robison (2020) on the 'contagion of passion'{{sfn|Robison|2020|p=180}} and Cass Sunstein (2001, pp. 98–136){{notetag|The 2001 reference is to an earlier edition of Sunstein's Republic.com. An updated chapter on cybercascades may be found in his Republic.com 2.0 (2007).{{sfn|Sunstein|2007|pp=46-96}}}} on 'cybercascades'.)"{{sfn|O'Callaghan|2020|p=116}} |

||

| Line 203: | Line 185: | ||

Ott agrees, saying contagion is the best word to describe the viral nature of outrage discourse on social media. "Trump's simple, impulsive, and uncivil Tweets do more than merely reflect sexism, racism, homophobia, and xenophobia; they spread those ideologies like a social cancer."{{sfn|Ott|2017|p=64}} Robison warns that [[emotional contagion]] should not be confused with the contagion of passions that [[James Madison]] and [[David Hume]] were concerned with.{{notetag|Hume argued that democracy in [[city-states]] of ancient Greece failed because in small cities, sentiments could rapidly spread in the population, meaning agitators were "more likely to succeed in sweeping aside the old order". Madison responded to this threat of tyrannical majority factions unified by a shared sentiment in [[Federalist No. 10|Federalist paper number 10]] with the argument (Robison's paraphrase): "In an extensive country, distance immunizes citizens from the contagion of passions and hinders their coordination even when passions are shared."{{sfn|Robison|2020|p=180}} Robison thinks this portion of Madison's argument is obsolete due to the near instantaneous social media sharing of sentiments wherever we are due to the commonplace use of wirelessly connected handheld devices.}} Yet Robison thinks they underestimated the contagion of passions mechanism at work in movements, whose modern expressions include the surprising phenomena of rapidly mobilized social media supporters behind both the [[Arab Spring]] and the Trump presidential campaign. "It is not that we experience something and then, assessing it, become passionate about it, or not," implying that "we have the possibility of a check on our passions." Robison's view is that the contagion affects the way reality itself is experienced by supporters because it leverages how subjective certainty is triggered, so that those experiencing the contagiously shared alternate reality are unaware they have taken on a belief they should assess.{{sfn|Robison|2020|p=182}} |

Ott agrees, saying contagion is the best word to describe the viral nature of outrage discourse on social media. "Trump's simple, impulsive, and uncivil Tweets do more than merely reflect sexism, racism, homophobia, and xenophobia; they spread those ideologies like a social cancer."{{sfn|Ott|2017|p=64}} Robison warns that [[emotional contagion]] should not be confused with the contagion of passions that [[James Madison]] and [[David Hume]] were concerned with.{{notetag|Hume argued that democracy in [[city-states]] of ancient Greece failed because in small cities, sentiments could rapidly spread in the population, meaning agitators were "more likely to succeed in sweeping aside the old order". Madison responded to this threat of tyrannical majority factions unified by a shared sentiment in [[Federalist No. 10|Federalist paper number 10]] with the argument (Robison's paraphrase): "In an extensive country, distance immunizes citizens from the contagion of passions and hinders their coordination even when passions are shared."{{sfn|Robison|2020|p=180}} Robison thinks this portion of Madison's argument is obsolete due to the near instantaneous social media sharing of sentiments wherever we are due to the commonplace use of wirelessly connected handheld devices.}} Yet Robison thinks they underestimated the contagion of passions mechanism at work in movements, whose modern expressions include the surprising phenomena of rapidly mobilized social media supporters behind both the [[Arab Spring]] and the Trump presidential campaign. "It is not that we experience something and then, assessing it, become passionate about it, or not," implying that "we have the possibility of a check on our passions." Robison's view is that the contagion affects the way reality itself is experienced by supporters because it leverages how subjective certainty is triggered, so that those experiencing the contagiously shared alternate reality are unaware they have taken on a belief they should assess.{{sfn|Robison|2020|p=182}} |

||

== Similar movements, politicians and personalities == |

|||

== Similarities to other political leaders and activists == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The roots of Trumpism in the United States can be traced to the [[Jacksonian era]] according to scholars [[Walter Russell Mead]],{{sfn|Glasser|2018}} Peter Katzenstein{{sfn|Katzenstein|2019}} and Edwin Kent Morris.{{sfn|Morris|2019|p=20}} [[Eric Rauchway]] says: "Trumpism—[[Nativism (politics)|nativism]] and [[white supremacy]]—has deep roots in American history. But Trump himself put it to new and malignant purpose."{{sfn|Lyall|2021}} |

||

| ⚫ | [[Andrew Jackson]]'s followers felt he was one of them, enthusiastically supporting his defiance of [[politically correct]] norms of the nineteenth century and even constitutional law when they stood in the way of public policy popular among his followers. Jackson ignored the [[U.S. Supreme Court]] ruling in ''[[Worcester v. Georgia#Enforcement|Worcester v. Georgia]]'' and initiated the forced [[Cherokee removal]] from their treaty protected lands to benefit white locals at the cost of between 2,000 and 6,000 dead Cherokee men, women, and children. Notwithstanding such cases of Jacksonian inhumanity, Mead's view is that Jacksonianism provides the historical precedent explaining the movement of followers of Trump, marrying grass-roots disdain for elites, deep suspicion of overseas entanglements, and obsession with American power and sovereignty, acknowledging that it has often been a [[xenophobic]], "whites only" political movement. Mead thinks this "hunger in America for a Jacksonian figure" drives followers towards Trump but cautions that historically "he is not the second coming of Andrew Jackson," observing that "his proposals tended to be pretty vague and often contradictory," exhibiting the common weakness of newly elected populist leaders, commenting early in his presidency that "now he has the difficulty of, you know, 'How do you govern?'"{{sfn|Glasser|2018}} |

||

| ⚫ | Morris agrees with Mead, locating Trumpism's roots in the Jacksonian era from 1828 to 1848 under the presidencies of Jackson, [[Martin Van Buren]] and [[James K. Polk]]. On Morris's view, Trumpism also shares similarities with the post-World War I faction of the [[Progressivism in the United States|progressive movement]] which catered to a conservative populist recoil from the looser morality of the cosmopolitan cites and America's changing racial complexion.{{sfn|Morris|2019|p=20}} In his book ''[[The Age of Reform]]'' (1955), historian [[Richard Hofstadter]] identified this faction's emergence when "a large part of the Progressive-Populist tradition had turned sour, became illiberal and ill-tempered."{{sfn|Greenberg|2016}} |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:"America First" ad from Chicago mayoral election, 1927.jpg|thumb|upright=0.75|1927 "[[America First (policy)|America First]]" political advertisement advocating isolationism and establishing emotional ties of [[1927 Chicago mayoral election|1927 Chicago mayoral]] candidate [[William Hale Thompson]] with his Irish supporters by vilifying the United Kingdom, a close ally]] |

||

| ⚫ | Prior to World War II, conservative themes of Trumpism were expressed in the [[America First Committee|America First]] movement in the early 20th century, and after World War II were attributed to a [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican Party]] faction known as the [[Old Right (United States)|Old Right]]. By the 1990s, it became referred to as the [[paleoconservative]] movement, which according to Morris has now been re-branded as Trumpism.{{sfn|Morris|2019|p=21}} [[Leo Löwenthal]]'s book ''[[Prophets of Deceit]]'' (1949) summarized common narratives expressed in the post-World War II period of this populist fringe, specifically examining American [[demagogues]] of the period when modern mass media was married with the same destructive style of politics that historian Charles Clavey thinks Trumpism represents. According to Clavey, Löwenthal's book best explains the enduring appeal of Trumpism and offers the most striking historical insights into the movement.{{sfn|Clavey|2020}} |

||

| ⚫ | Writing in ''[[The New Yorker]]'', journalist [[Nicholas Lemann]] states the post-war Republican Party ideology of [[fusionism]], a fusion of pro-business party establishment with [[Nativism in the United States|nativist]], [[United States non-interventionism|isolationist]] elements who gravitated towards the Republican and not the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]], later joined by Christian evangelicals "alarmed by the rise of secularism", was made possible by the [[Cold War]] and the "mutual fear and hatred of the spread of Communism". An article in Politco has referred to Trumpism as "[[McCarthyism]] on steroids".{{sfn|MacWilliams|2020}}{{sfn|Lemann|2020}} |

||

| ⚫ | Championed by [[William F. Buckley Jr.]] and brought to fruition by [[Ronald Reagan]] in 1980, the fusion lost its glue with the [[collapse of the Soviet Union]], which was followed by a growth of [[Income inequality in the United States|inequality]] and [[globalization]] that "created major discontent among middle and low income whites" within and without the Republican Party. After the [[2012 United States presidential election]] saw the defeat of [[Mitt Romney]] by [[Barack Obama]], the party establishment embraced an "autopsy" report, titled the Growth and Opportunity Project, which "called on the Party to reaffirm its identity as pro-market, government-skeptical, and ethnically and culturally inclusive." Ignoring the findings of the report and the party establishment in his campaign, Trump was "opposed by more officials in his own Party [...] than any Presidential nominee in recent American history," but at the same time he won "more votes" in the Republican primaries than any previous presidential candidate. By 2016, "people wanted somebody to throw a brick through a plate-glass window", in the words of political analyst [[Karl Rove]].{{sfn|Lemann|2020}} His success in the party was such that an October 2020 poll found 58% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents surveyed considered themselves supporters of Trump rather than the Republican Party.{{sfn|Peters|2020}} |

||

=== Trend towards illiberal democracy === |

|||

[[File:Trumpism Projection SumOfUs Final 2 (43707702255).jpg|thumb|Activist group [[SumOfUs]]'s Projection of "Resist Trumpism Everywhere" on London's [[Marble Arch]] as part of protests during Trump's July 2018 visit]] |

[[File:Trumpism Projection SumOfUs Final 2 (43707702255).jpg|thumb|Activist group [[SumOfUs]]'s Projection of "Resist Trumpism Everywhere" on London's [[Marble Arch]] as part of protests during Trump's July 2018 visit]] |

||

Trumpism has been likened to [[Machiavellianism (politics)|Machiavellianism]] and to [[Italian Fascism|Mussolini's fascism]].{{sfn|Matthews|2021}}{{sfn|Boucheron|2020}}{{sfn|Robertson|2020}}{{sfn|Hasan|2020}}{{sfn|Urbinati|2020}}{{sfn|Shenk|2016}}{{sfn|Illing|2018}} |

Trumpism has been likened to [[Machiavellianism (politics)|Machiavellianism]] and to [[Italian Fascism|Mussolini's fascism]].{{sfn|Matthews|2021}}{{sfn|Boucheron|2020}}{{sfn|Robertson|2020}}{{sfn|Hasan|2020}}{{sfn|Urbinati|2020}}{{sfn|Shenk|2016}}{{sfn|Illing|2018}} |

||

| Line 215: | Line 213: | ||

Political scientist [[Mark Blyth]] and his colleague [[Jonathan Hopkin]] believe strong similarities exist between Trumpism and similar movements towards [[illiberal democracies]] worldwide, but they do not believe Trumpism is a movement which is merely being driven by revulsion, loss, and racism. Hopkin and Blyth argue that both on the right and on the left the global economy is driving the growth of [[neo-nationalist]] coalitions which find followers who want to be free of the constraints which are being placed on them by establishment elites whose members advocate [[neoliberal economics]] and [[globalism]].{{sfn|Hopkin|Blyth|2020}} Others emphasize the lack of interest in finding real solutions to the social malaise which have been identified, and they also believe those individuals and groups who are executing policy are actually following a pattern which has been identified by sociology researchers like [[Leo Löwenthal]] and [[Norbert Guterman]] as originating in the post-World War II work of the Frankfurt School of social theory. Based on this perspective, books such as Löwenthal and Guterman's ''Prophets of Deceit'' offer the best insights into how movements like Trumpism dupe their followers by perpetuating their misery and preparing them to move further towards an illiberal form of government.{{sfn|Clavey|2020}} |

Political scientist [[Mark Blyth]] and his colleague [[Jonathan Hopkin]] believe strong similarities exist between Trumpism and similar movements towards [[illiberal democracies]] worldwide, but they do not believe Trumpism is a movement which is merely being driven by revulsion, loss, and racism. Hopkin and Blyth argue that both on the right and on the left the global economy is driving the growth of [[neo-nationalist]] coalitions which find followers who want to be free of the constraints which are being placed on them by establishment elites whose members advocate [[neoliberal economics]] and [[globalism]].{{sfn|Hopkin|Blyth|2020}} Others emphasize the lack of interest in finding real solutions to the social malaise which have been identified, and they also believe those individuals and groups who are executing policy are actually following a pattern which has been identified by sociology researchers like [[Leo Löwenthal]] and [[Norbert Guterman]] as originating in the post-World War II work of the Frankfurt School of social theory. Based on this perspective, books such as Löwenthal and Guterman's ''Prophets of Deceit'' offer the best insights into how movements like Trumpism dupe their followers by perpetuating their misery and preparing them to move further towards an illiberal form of government.{{sfn|Clavey|2020}} |

||

=== Precursors === |

=== Recent Precursors === |

||

Trump is considered by some analysts to be following a blueprint leveraging outrage which was developed on partisan cable TV and talk radio shows{{sfn|O'Callaghan|2020|p=116}} such as the [[Rush Limbaugh]] radio show—a style that transformed [[talk radio]] and American conservative politics decades before Trump.{{sfn|McFadden|Grynbaum|2021}} Both shared "media fame", "over-the-top showmanship", and built an enormous fan base with politics-as-entertainment,{{sfn|McFadden|Grynbaum|2021}} attacking political and cultural targets in ways that would have been considered indefensible and beyond the pale in the years before him.{{sfn|Peters|2021}} |

Trump is considered by some analysts to be following a blueprint leveraging outrage which was developed on partisan cable TV and talk radio shows{{sfn|O'Callaghan|2020|p=116}} such as the [[Rush Limbaugh]] radio show—a style that transformed [[talk radio]] and American conservative politics decades before Trump.{{sfn|McFadden|Grynbaum|2021}} Both shared "media fame", "over-the-top showmanship", and built an enormous fan base with politics-as-entertainment,{{sfn|McFadden|Grynbaum|2021}} attacking political and cultural targets in ways that would have been considered indefensible and beyond the pale in the years before him.{{sfn|Peters|2021}} |

||

| Line 224: | Line 222: | ||

=== Future impact === |

=== Future impact === |

||

Writing in the Atlantic magazine, Yaseem Serhan, argues Trump's post-impeachment claim that "our historic, patriotic, and beautiful movement to Make America Great Again has only just begun," should be taken seriously as Trumpism is a "personality-driven" populist movement, and other such movements—such as [[Berlusconism]] in Italy, [[Peronism|Perónism]] in Argentina and [[Fujimorism|Fujimorismo]] in Peru, "rarely fade once their leaders have left office".{{sfn|Serhan|2021}} [[Bobby Jindal]] and [[Alex Castellanos]] wrote in Newsweek that separating Trumpism from Donald Trump himself was key to the Republican Party's future following his loss in the [[2020 United States presidential election]].{{sfn|Jindal|Castellanos|2021}} |

Writing in the Atlantic magazine, Yaseem Serhan, argues Trump's post-impeachment claim that "our historic, patriotic, and beautiful movement to Make America Great Again has only just begun," should be taken seriously as Trumpism is a "personality-driven" populist movement, and other such movements—such as [[Berlusconism]] in Italy, [[Peronism|Perónism]] in Argentina and [[Fujimorism|Fujimorismo]] in Peru, "rarely fade once their leaders have left office".{{sfn|Serhan|2021}} [[Bobby Jindal]] and [[Alex Castellanos]] wrote in Newsweek that separating Trumpism from Donald Trump himself was key to the Republican Party's future following his loss in the [[2020 United States presidential election]].{{sfn|Jindal|Castellanos|2021}} |

||

== Foreign policy == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In terms of foreign policy in the sense of Trump's "[[America First (policy)|America First]]", [[unilateralism]] is preferred to a multilateral policy and national interests are particularly emphasized, especially in the context of economic treaties and alliance obligations.{{sfn|Rudolf|2017}}{{sfn|Assheuer|2018}} Trump has shown a disdain for traditional American allies such as Canada as well as transatlantic partners [[NATO]] and the [[European Union]].{{sfn|Smith|Townsend|2018}}{{sfn|Tharoor|2018}} Conversely, Trump has shown sympathy for [[autocratic]] rulers, especially for the Russian president [[Vladimir Putin]], whom Trump often praised even before taking office,{{sfn|Diamond|2016}} and during the [[2018 Russia–United States summit]].{{sfn|Kuhn|2018}} The "America First" foreign policy includes promises by Trump to end American involvement in foreign wars, notably in the [[United States foreign policy in the Middle East|Middle East]], while also issuing tighter foreign policy through [[United States sanctions against Iran|sanctions against Iran]], among other countries.{{sfn|Zengerle|2019}}{{sfn|Wintour|2020}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In terms of economic policy, Trumpism "promises new jobs and more domestic investment".{{sfn|Harwood|2017}} Trump's hard line against export surpluses of American trading partners has led to a tense situation in 2018 with mutually imposed punitive tariffs between the United States on the one hand and the European Union and China on the other.{{sfn|Partington|2018}} Trump secures the support of his political base with a policy that strongly emphasizes [[Neo-nationalism|nationalism]] and [[criticism of globalization]].{{sfn|Thompson|2017}} While the book ''Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America'' suggested that Trump [[Radicalization|"Radicalized]] economics" to his base of white working to middle class voters by the promoting the idea that "undeserving [minority] groups are getting ahead while their group is being left behind."{{sfn|O'Connor|2020}} |

||

== Trumpism in other countries == |

== Trumpism in other countries == |

||

| Line 426: | Line 432: | ||

* {{cite news |last1=Johnston |first1=Rich |date=July 3, 2020 |title=Why Did Sean Hannity Lose His Punisher Skull Pin On Fox News? |work=[[Bleeding Cool]] |url=https://bleedingcool.com/comics/why-did-sean-hannity-lose-his-punisher-skull-pin-on-fox-news/ |access-date=February 8, 2021 |archive-date=February 15, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210215222915/https://bleedingcool.com/comics/why-did-sean-hannity-lose-his-punisher-skull-pin-on-fox-news/ |url-status=live }} |

* {{cite news |last1=Johnston |first1=Rich |date=July 3, 2020 |title=Why Did Sean Hannity Lose His Punisher Skull Pin On Fox News? |work=[[Bleeding Cool]] |url=https://bleedingcool.com/comics/why-did-sean-hannity-lose-his-punisher-skull-pin-on-fox-news/ |access-date=February 8, 2021 |archive-date=February 15, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210215222915/https://bleedingcool.com/comics/why-did-sean-hannity-lose-his-punisher-skull-pin-on-fox-news/ |url-status=live }} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Jones |first1=Karen |date=2019 |title=Trust, distrust, and affective looping |journal= Philosophical Studies| issue=176 |publisher=Springer Nature |doi=10.1007/s11098-018-1221-5 }} |

* {{cite journal |last1=Jones |first1=Karen |date=2019 |title=Trust, distrust, and affective looping |journal= Philosophical Studies| issue=176 |publisher=Springer Nature |doi=10.1007/s11098-018-1221-5 }} |

||

** Partial reprint: {{cite web |last=Jones |first=Karen |title= Understanding the emotions is key to breaking the cycle of distrust |date=November 14, 2019 |work= ABC’s Religion and Ethics |publisher=Australian Broadcasting Corporation |access-date= April 10, 2021 |url=https://www.abc.net.au/religion/understanding-emotions-and-breaking-the-cycle-of-distrust/11704032}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Jones|first1=Karen |chapter= Trusting Interpretations |title=Trust: Analytic and Applied Perspectives |editor1-last=Mäkelä |editor1-first=Pekka| editor2-last=Townley |editor2-first=Cynthia |isbn=9789401209410 |date=2013 |publisher=Rodopi|volume=263|series=Value Inquiry Book Series }} |