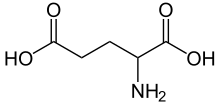

Glutamic acid

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Glutamic acid

| |

| Other names

2-Aminopentanedioic acid

2-Aminoglutaric acid | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.009.567 |

| E number | E620 (flavour enhancer) |

| KEGG | |

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C5H9NO4 | |

| Molar mass | 147.130 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Density | 1.4601 (20 °C) |

| Melting point | 199 °C decomp. |

| 8.64 g/l (25 °C) [1] | |

| Solubility | 0.00035g/100g ethanol 25 degC [2] |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Glutamic acid (data page) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Glutamic acid (abbreviated as Glu or E) is one of the 20-22 proteinogenic amino acids, and its codons are GAA and GAG. It is a non-essential amino acid. The carboxylate anions and salts of glutamic acid are known as glutamates. In neuroscience, glutamate is an important neurotransmitter that plays a key role in long-term potentiation and is important for learning and memory.[3]

Chemistry

The side chain carboxylic acid functional group has pKa of 4.1 and exists in its negatively charged deprotonated carboxylate form at pHs greater than 4.1 therefore it is also negatively charged at physiological pH ranging from 7.35 to 7.45.

History

Although they occur naturally in many foods, the flavor contributions made by glutamic acid and other amino acids were only scientifically identified early in the twentieth century. The substance was discovered and identified in the year 1866, by the German chemist Karl Heinrich Leopold Ritthausen. In 1907 Japanese researcher Kikunae Ikeda of the Tokyo Imperial University identified brown crystals left behind after the evaporation of a large amount of kombu broth as glutamic acid. These crystals, when tasted, reproduced the ineffable but undeniable flavor he detected in many foods, most especially in seaweed. Professor Ikeda termed this flavor umami. He then patented a method of mass-producing a crystalline salt of glutamic acid, monosodium glutamate.[4][5]

Biosynthesis

| Reactants | Products | Enzymes |

|---|---|---|

| Glutamine + H2O | → Glu + NH3 | GLS, GLS2 |

| NAcGlu + H2O | → Glu + Acetate | (unknown) |

| α-ketoglutarate + NADPH + NH4+ | → Glu + NADP+ + H2O | GLUD1, GLUD2[6] |

| α-ketoglutarate + α-amino acid | → Glu + α-keto acid | transaminase |

| 1-Pyrroline-5-carboxylate + NAD+ + H2O | → Glu + NADH | ALDH4A1 |

| N-formimino-L-glutamate + FH4 | → Glu + 5-formimino-FH4 | FTCD |

Function and uses

Metabolism

Glutamate is a key compound in cellular metabolism. In humans, dietary proteins are broken down by digestion into amino acids, which serve as metabolic fuel for other functional roles in the body. A key process in amino acid degradation is transamination, in which the amino group of an amino acid is transferred to an α-ketoacid, typically catalysed by a transaminase. The reaction can be generalised as such:

- R1-amino acid + R2-α-ketoacid ⇌ R1-α-ketoacid + R2-amino acid

A very common α-keto acid is α-ketoglutarate, an intermediate in the citric acid cycle. Transamination of α-ketoglutarate gives glutamate. The resulting α-ketoacid product is often a useful one as well, which can contribute as fuel or as a substrate for further metabolism processes. Examples are as follows:

- Aspartate + α-ketoglutarate ⇌ oxaloacetate + glutamate

Both pyruvate and oxaloacetate are key components of cellular metabolism, contributing as substrates or intermediates in fundamental processes such as glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and the citric acid cycle.

Glutamate also plays an important role in the body's disposal of excess or waste nitrogen. Glutamate undergoes deamination, an oxidative reaction catalysed by glutamate dehydrogenase,[6] as follows:

Ammonia (as ammonium) is then excreted predominantly as urea, synthesised in the liver. Transamination can, thus, be linked to deamination, effectively allowing nitrogen from the amine groups of amino acids to be removed, via glutamate as an intermediate, and finally excreted from the body in the form of urea.

Neurotransmitter

Glutamate is the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter in the vertebrate nervous system.[7] At chemical synapses, glutamate is stored in vesicles. Nerve impulses trigger release of glutamate from the pre-synaptic cell. In the opposing post-synaptic cell, glutamate receptors, such as the NMDA receptor, bind glutamate and are activated. Because of its role in synaptic plasticity, glutamate is involved in cognitive functions like learning and memory in the brain.[8] The form of plasticity known as long-term potentiation takes place at glutamatergic synapses in the hippocampus, neocortex, and other parts of the brain. Glutamate works not only as a point-to-point transmitter but also through spill-over synaptic crosstalk between synapses in which summation of glutamate released from a neighboring synapse creates extrasynaptic signaling/volume transmission.[9]

Glutamate transporters[10] are found in neuronal and glial membranes. They rapidly remove glutamate from the extracellular space. In brain injury or disease, they can work in reverse, and excess glutamate can accumulate outside cells. This process causes calcium ions to enter cells via NMDA receptor channels, leading to neuronal damage and eventual cell death, and is called excitotoxicity. The mechanisms of cell death include

- Damage to mitochondria from excessively high intracellular Ca2+[11]

- Glu/Ca2+-mediated promotion of transcription factors for pro-apoptotic genes, or downregulation of transcription factors for anti-apoptotic genes

Excitotoxicity due to glutamate occurs as part of the ischemic cascade and is associated with stroke[3] and diseases like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, lathyrism, autism, some forms of mental retardation, and Alzheimer's disease.[3][12]

Glutamic acid has been implicated in epileptic seizures. Microinjection of glutamic acid into neurons produces spontaneous depolarisations around one second apart, and this firing pattern is similar to what is known as paroxysmal depolarizing shift in epileptic attacks. This change in the resting membrane potential at seizure foci could cause spontaneous opening of voltage-activated calcium channels, leading to glutamic acid release and further depolarization.

Experimental techniques to detect glutamate in intact cells include using a genetically-engineered nanosensor.[13] The sensor is a fusion of a glutamate-binding protein and two fluorescent proteins. When glutamate binds, the fluorescence of the sensor under ultraviolet light changes by resonance between the two fluorophores. Introduction of the nanosensor into cells enables optical detection of the glutamate concentration. Synthetic analogs of glutamic acid that can be activated by ultraviolet light and two-photon excitation microscopy have also been described.[14] This method of rapidly uncaging by photostimulation is useful for mapping the connections between neurons, and understanding synapse function.

Evolution of glutamate receptors is entirely the opposite in invertebrates, in particular, arthropods and nematodes, where glutamate stimulates glutamate-gated chloride channels.[citation needed] The beta subunits of the receptor respond with very high affinity to glutamate and glycine.[15] Targeting these receptors has been the therapeutic goal of anthelmintic therapy using avermectins. Avermectins target the alpha-subunit of glutamate-gated chloride channels with high affinity.[16] These receptors have also been described in arthropods, such as Drosophila melanogaster[17] and Lepeophtheirus salmonis.[18] Irreversible activation of these receptors with avermectins results in hyperpolarization at synapses and neuromuscular junctions resulting in flaccid paralysis and death of nematodes and arthropods.

Brain nonsynaptic glutamatergic signaling circuits

Extracellular glutamate in Drosophila brains has been found to regulate postsynaptic glutamate receptor clustering, via a process involving receptor desensitization.[19] A gene expressed in glial cells actively transports glutamate into the extracellular space,[19] while, in the nucleus accumbens-stimulating group II metabotropic glutamate receptors, this gene was found to reduce extracellular glutamate levels.[20] This raises the possibility that this extracellular glutamate plays an "endocrine-like" role as part of a larger homeostatic system.

GABA precursor

Glutamate also serves as the precursor for the synthesis of the inhibitory GABA in GABA-ergic neurons. This reaction is catalyzed by glutamate decarboxylase (GAD), which is most abundant in the cerebellum and pancreas.

Stiff-man syndrome is a neurologic disorder caused by anti-GAD antibodies, leading to a decrease in GABA synthesis and, therefore, impaired motor function such as muscle stiffness and spasm. Since the pancreas is also abundant for the enzyme GAD, a direct immunological destruction occurs in the pancreas and the patients will have diabetes mellitus.

Flavor enhancer

Glutamic acid, being a constituent of protein, is present in every food that contains protein, but it can only be tasted when it is present in an unbound form. Significant amounts of free glutamic acid are present in a wide variety of foods, including cheese and soy sauce, and is responsible for umami, one of the five basic tastes of the human sense of taste. Glutamic acid is often used as a food additive and flavour enhancer in the form of its sodium salt monosodium glutamate (MSG).

Nutrient

All meats, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy products, and kombu are excellent sources of glutamic acid. Some protein-rich plant foods also serve as sources. Thirty to 35% of the protein in wheat is glutamic acid. Ninety-five percent of the dietary glutamate is metabolized by intestinal cells in a first pass.[21]

Plant growth

Auxigro is a plant growth preparation that contains 30% glutamic acid.

NMR Spectroscopy

In recent years, there has been much research into the use of RDCs in NMR spectroscopy. A glutamic acid derivative, poly-γ-benzyl-L-glutamate (PBLG), is often used as an alignment medium to control the scale of the dipolar interactions observed.[22]

Production

China-based Fufeng Group Limited is the largest producer of glutamic acid in the world, with capacity increasing to 300,000 tons at the end of 2006 from 180,000 tons during 2006, putting them at 25%–30% of the Chinese market. Meihua is the second-largest Chinese producer. Together, the top-five producers have roughly 50% share in China. Chinese demand is roughly 1.1 million tons per year, while global demand, including China, is 1.7 million tons per year.

Pharmacology

The drug phencyclidine (more commonly known as PCP) antagonizes glutamic acid non-competitively at the NMDA receptor. For the same reasons, sub-anaesthetic doses of ketamine have strong dissociative and hallucinogenic effects. Glutamate does not easily pass the blood brain barrier, but, instead, is transported by a high-affinity transport system.[23] It can also be converted into glutamine.

See also

References

- ^ http://hazard.com/msds/mf/baker/baker/files/g3970.htm

- ^ http://books.google.ch/books?id=xteiARU46SQC&pg=PA15&lpg=PA15&dq=methionine+solubility+in+ethanol&source=bl&ots=HzHueOPPoB&sig=KjMXxDNgjSvG1CddED9lfaYEhKQ&hl=en&sa=X&ei=2-26T-bZK-mX0QWt3I2ACA&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=methionine%20solubility%20in%20ethanol&f=false

- ^ a b c Robert Sapolsky (2005). "Biology and Human Behavior: The Neurological Origins of Individuality, 2nd edition". The Teaching Company.

see pages 19 and 20 of Guide Book

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Renton, Alex (2005-07-10). "If MSG is so bad for you, why doesn't everyone in Asia have a headache?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Kikunae Ikeda Sodium Glutamate". Japan Patent Office. 2002-10-07. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/s11738-011-0801-1, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/s11738-011-0801-1instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10736372, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10736372instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/BF02253527, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/BF02253527instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1073/pnas.0913154107, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1073/pnas.0913154107instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.04.004, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.04.004instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2568579, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=2568579instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2004.03.007, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.neuint.2004.03.007instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1073/pnas.0503274102, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1073/pnas.0503274102instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1519-07.2007, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1523/jneurosci.1519-07.2007instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64052354.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64052354.xinstead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/371707a0, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/371707a0instead. - ^ Cully, D.F., Paress, P.S., Liu, K.K., Schaeffer, J.M. and Arena, J.P. 1996. "Identification of a Drosophila melanogaster glutamate-gated chloride channel sensitive to the antiparasitic agent avermectin". J. Biol. Chem. '271, 20187-20191'

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1365-2885.2007.00823.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2885.2007.00823.xinstead. - ^ a b Augustin H, Grosjean Y, Chen K, Sheng Q, Featherstone DE (2007). "Nonvesicular Release of Glutamate by Glial xCT Transporters Suppresses Glutamate Receptor Clustering In Vivo". Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (1): 111–123. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4770-06.2007. PMC 2193629. PMID 17202478.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zheng Xi, Baker DA, Shen H, Carson DS, Kalivas PW (2002). "Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate extracellular glutamate in the nucleus accumbens". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 300 (1): 162–171. doi:10.1124/jpet.300.1.162. PMID 11752112.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reeds, P.J.; et al. (1 April 2000). "Intestinal glutamate metabolism". Journal of Nutrition. 130 (4s): 978S–982S. PMID 10736365.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ C. M. Thiele, Concepts Magn. Reson. A, 2007, 30A, 65-80

- ^ Smith QR (2000). "Transport of glutamate and other amino acids at the blood–brain barrier". J. Nutr. 130 (4S Suppl): 1016S–22S. PMID 10736373.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Nelson, David L.; Cox, Michael M. (2005). Principles of Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.