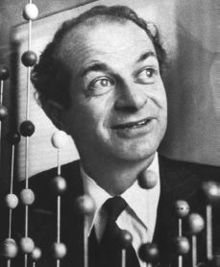

Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (February 28, 1901 – August 19, 1994)[4] was an American chemist, biochemist, peace activist, author, and educator. He was one of the most influential chemists in history and ranks among the most important scientists of the 20th century.[5][6] Pauling was one of the founders of the fields of quantum chemistry and molecular biology.[7]

For his scientific work, Pauling was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1954. In 1962, for his peace activism, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. This makes him the only person to be awarded two unshared Nobel Prizes. He is one of only four individuals to have won more than one Nobel Prize (the others being Marie Curie, John Bardeen, and Frederick Sanger). Pauling is also one of only two people to be awarded Nobel Prizes in different fields, the other being Marie Curie.[8]

He promoted orthomolecular medicine, megavitamin therapy, dietary supplements, and taking large doses of vitamin C.

Early life and education

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as Excessive extraneous genealogical data not directly relevant to Linus' life. (March 2014) |

Pauling was born in Portland, Oregon,[9][10] as the first-born child of Herman Henry William Pauling (1876–1910) and Lucy Isabelle "Belle" Darling (1881–1926).[11] He was named "Linus Carl," in honor of Lucy's father, Linus, and Herman's father, Carl.[12] Lucy's great grandfather William Darling, Sr., has a documented lineage to Elder William Brewster, who arrived in America on the Mayflower, and it is used as a sample lineage.[13]

Linus Pauling spent his first year living in a one-room apartment with his parents in Portland. In 1902, after his sister Pauline was born, Pauling's parents decided to move out of the city.[14] They were crowded in their apartment, but could not afford more spacious living quarters in Portland. Lucy stayed with her husband's parents in Lake Oswego, while Herman searched for new housing. Herman brought the family to Salem, where he took up a job as a traveling salesman for the Skidmore Drug Company. Within a year of Lucile's birth in 1904, Herman Pauling moved his family to Oswego, where he opened his own drugstore.[14] The business climate in Oswego was poor, so he moved his family to Condon in 1905.[15] By 1909, Herman Pauling was suffering from poor health and had regular sharp pains in his abdomen. His health worsened in the coming months and he finally died of a perforated ulcer on June 11, 1910, leaving Lucy to care for Linus, Lucile and Pauline.[16]

At age nine, Linus was a voracious reader. On May 12, 1910 his father wrote a letter to The Oregonian inviting suggestions of additional books to occupy his time.[4] Pauling first planned to become a chemist after being amazed by experiments conducted with a small chemistry lab kit by his friend, Lloyd A. Jeffress.[17] At high school, Pauling continued to conduct chemistry experiments, scavenging much of the equipment and material from an abandoned steel plant. With an older friend, Lloyd Simon, Pauling set up Palmon Laboratories. Operating from Simon's basement, the two approached local dairies to offer their services in performing butterfat samplings at cheap prices. Dairymen were wary of trusting two boys with the task, and as such, the business ended in failure.[18]

By the fall of 1916, Pauling was a 15-year-old high school senior with enough credits to enter Oregon State University (OSU), known then as Oregon Agricultural College.[19] He did not have enough credits for two required American history courses that would satisfy the requirements for earning a high school diploma. He asked the school principal if he could take these courses concurrently during the spring semester, but the principal denied his request, and Pauling decided to leave the school in June without a diploma.[20] His high school, Washington High School in Portland, awarded him the diploma 45 years later, after he had won two Nobel Prizes.[21][22] During the summer, Pauling worked part-time at a grocery store, earning eight US dollars a week. His mother set him up with an interview with a Mr. Schwietzerhoff, the owner of a number of manufacturing plants in Portland. Pauling was hired as an apprentice machinist with a salary of 40 dollars per month. Pauling excelled at his job, and saw his salary soon raised to 50 dollars per month.[23] In his spare time, he set up a photography laboratory with two friends and found business from a local photography company. He hoped that the business would earn him enough money to pay for his future college expenses.[24] Pauling received a letter of admission from Oregon State University in September 1917 and immediately gave notice to his boss and told his mother of his plans.[25]

Higher education

In his first semester, Pauling registered for two courses in chemistry, two in mathematics, mechanical drawing, introduction to mining and use of explosives, modern English prose, gymnastics and military drill.[26] He was active in campus life and founded the school's chapter of the Delta Upsilon fraternity.[27] After his second year, he planned to take a job in Portland to help support his mother, but the college offered him a position teaching quantitative analysis, a course he had just finished taking himself. He worked forty hours a week in the laboratory and classroom and earned $100 a month.[28] This allowed him to continue his studies at the college.

In his last two years at school, Pauling became aware of the work of Gilbert N. Lewis and Irving Langmuir on the electronic structure of atoms and their bonding to form molecules.[28] He decided to focus his research on how the physical and chemical properties of substances are related to the structure of the atoms of which they are composed, becoming one of the founders of the new science of quantum chemistry. Pauling began to neglect his studies in humanities and social sciences. He had also exhausted the course offerings in the physics and mathematics departments. Professor Samuel Graf selected Pauling to be his teaching assistant in a high-level mathematics course.[29] During the winter of his senior year, Pauling was approached by the college to teach a chemistry course for home economics majors. It was in one of these classes that Pauling met his future wife, Ava Helen Miller.[30]

In 1922, Pauling graduated from Oregon State University[4] (known then as Oregon Agricultural College) with a degree in chemical engineering and went on to graduate school at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, California, under the guidance of Roscoe Dickinson and Richard Tolman.[1] His graduate research involved the use of X-ray diffraction to determine the structure of crystals. He published seven papers on the crystal structure of minerals while he was at Caltech. He received his PhD in physical chemistry and mathematical physics,[3] summa cum laude, in 1925.[31]

Personal life

While teaching a class called "Chemistry for Home Economic Majors" at college,[32] Pauling met his future wife, Ava Helen Miller and they married June 17, 1923. The marriage lasted until Ava Pauling's death in 1981 and produced three sons (Linus Jr., Peter and Edward Crellin) and a daughter (Linda).[33] Pauling's sons went on to become scientists and researchers (Linus, a psychiatrist; Peter, who died in 2003, a crystallographer; and Edward Crellin, who died in 1997, a biologist; daughter Linda married the noted Caltech geologist and glaciologist Barclay Kamb).[34]

Pauling was raised as a member of the Lutheran Church, but later joined the Unitarian Universalist Church. Two years before his death, in a published dialogue with Buddhist philosopher Daisaku Ikeda, Pauling publicly declared his atheism.[35]

Career

Pauling was first exposed to the concepts of quantum mechanics while studying at Oregon State University. He later traveled to Europe on a Guggenheim Fellowship, which was awarded to him in 1926, to study under German physicist Arnold Sommerfeld in Munich, Danish physicist Niels Bohr in Copenhagen and Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger in Zürich. All three were experts in the new field of quantum mechanics and other branches of physics. Pauling became interested in how quantum mechanics might be applied in his chosen field of interest, the electronic structure of atoms and molecules. In Zürich, Pauling was also exposed to one of the first quantum mechanical analyses of bonding in the hydrogen molecule, done by Walter Heitler and Fritz London. Pauling devoted the two years of his European trip to this work and decided to make it the focus of his future research. He became one of the first scientists in the field of quantum chemistry and a pioneer in the application of quantum theory to the structure of molecules. He also joined Alpha Chi Sigma, the professional chemistry fraternity.

In 1927, Pauling took a new position as an assistant professor at Caltech in theoretical chemistry. He launched his faculty career with a very productive five years, continuing with his X-ray crystal studies and also performing quantum mechanical calculations on atoms and molecules. He published approximately fifty papers in those five years, and created the five rules now known as Pauling's rules. By 1929, he was promoted to associate professor, and by 1930, to full professor. In 1931, the American Chemical Society awarded Pauling the Langmuir Prize for the most significant work in pure science by a person 30 years of age or younger.[36] The following year, Pauling published what he regarded as his most important paper, in which he first laid out the concept of hybridization of atomic orbitals and analyzed the tetravalency of the carbon atom.[37]

At Caltech, Pauling struck up a close friendship with theoretical physicist Robert Oppenheimer, who was spending part of his research and teaching schedule away from U.C. Berkeley at Caltech every year. The two men planned to mount a joint attack on the nature of the chemical bond: apparently Oppenheimer would supply the mathematics and Pauling would interpret the results. Their relationship soured when Oppenheimer tried to pursue Pauling's wife, Ava Helen. Once, when Pauling was at work, Oppenheimer had come to their place and blurted out an invitation to Ava Helen to join him on a tryst in Mexico.[38] She flatly refused, and reported the incident to Pauling. Disquieted by this strange chemistry, and her apparent nonchalance about the incident, he immediately cut off his relationship with Oppenheimer.

In the summer of 1930, Pauling made another European trip, during which he learned about the use of electrons in diffraction studies similar to the ones he had performed with X-rays. After returning, he built an electron diffraction instrument at Caltech with a student of his, L. O. Brockway, and used it to study the molecular structure of a large number of chemical substances.

Pauling introduced the concept of electronegativity in 1932. Using the various properties of molecules, such as the energy required to break bonds and the dipole moments of molecules, he established a scale and an associated numerical value for most of the elements – the Pauling Electronegativity Scale – which is useful in predicting the nature of bonds between atoms in molecules.

Nature of the chemical bond

In the late 1920s, Pauling began publishing papers on the nature of the chemical bond, leading to his famous textbook on the subject published in 1939. It is based primarily on his work in this area that he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1954 "for his research into the nature of the chemical bond and its application to the elucidation of the structure of complex substances". Pauling summarized his work on the chemical bond in The Nature of the Chemical Bond, one of the most influential chemistry books ever published.[39] In the 30 years after its first edition was published in 1939, the book was cited more than 16,000 times. Even today, many modern scientific papers and articles in important journals cite this work, more than seventy years after the first publication.

Part of Pauling's work on the nature of the chemical bond led to his introduction of the concept of orbital hybridization.[40] While it is normal to think of the electrons in an atom as being described by orbitals of types such as s and p, it turns out that in describing the bonding in molecules, it is better to construct functions that partake of some of the properties of each. Thus the one 2s and three 2p orbitals in a carbon atom can be combined to make four equivalent orbitals (called sp3 hybrid orbitals), which would be the appropriate orbitals to describe carbon compounds such as methane, or the 2s orbital may be combined with two of the 2p orbitals to make three equivalent orbitals (called sp2 hybrid orbitals), with the remaining 2p orbital unhybridized, which would be the appropriate orbitals to describe certain unsaturated carbon compounds such as ethylene. Other hybridization schemes are also found in other types of molecules.

Another area which he explored was the relationship between ionic bonding, where electrons are transferred between atoms, and covalent bonding, where electrons are shared between atoms on an equal basis. Pauling showed that these were merely extremes, between which most actual cases of bonding fall. It was here especially that Pauling's electronegativity concept was particularly useful; the electronegativity difference between a pair of atoms will be the surest predictor of the degree of ionicity of the bond.[41]

The third of the topics that Pauling attacked under the overall heading of "the nature of the chemical bond" was the accounting of the structure of aromatic hydrocarbons, particularly the prototype, benzene.[42] The best description of benzene had been made by the German chemist Friedrich Kekulé. He had treated it as a rapid interconversion between two structures, each with alternating single and double bonds, but with the double bonds of one structure in the locations where the single bonds were in the other. Pauling showed that a proper description based on quantum mechanics was an intermediate structure which was a blend of each. The structure was a superposition of structures rather than a rapid interconversion between them. The name "resonance" was later applied to this phenomenon.[43] In a sense, this phenomenon resembles that of hybridization, described earlier, because it involves combining more than one electronic structure to achieve an intermediate result.

Biological molecules

In the mid-1930s, Pauling, strongly influenced by the biologically oriented funding priorities of the Rockefeller Foundation's Warren Weaver, decided to strike out into new areas of interest. Although Pauling's early interest had focused almost exclusively on inorganic molecular structures, he had occasionally thought about molecules of biological importance, in part because of Caltech's growing strength in biology. Pauling interacted with such great biologists as Thomas Hunt Morgan, Theodosius Dobzhanski, Calvin Bridges and Alfred Sturtevant. His early work in this area included studies of the structure of hemoglobin. He demonstrated that the hemoglobin molecule changes structure when it gains or loses an oxygen atom. As a result of this observation, he decided to conduct a more thorough study of protein structure in general. He returned to his earlier use of X-ray diffraction analysis. But protein structures were far less amenable to this technique than the crystalline minerals of his former work. The best X-ray pictures of proteins in the 1930s had been made by the British crystallographer William Astbury, but when Pauling tried, in 1937, to account for Astbury's observations quantum mechanically, he could not.

It took eleven years for Pauling to explain the problem: his mathematical analysis was correct, but Astbury's pictures were taken in such a way that the protein molecules were tilted from their expected positions. Pauling had formulated a model for the structure of hemoglobin in which atoms were arranged in a helical pattern, and applied this idea to proteins in general.

In 1951, based on the structures of amino acids and peptides and the planar nature of the peptide bond, Pauling, Robert Corey and Herman Branson correctly proposed the alpha helix and beta sheet as the primary structural motifs in protein secondary structure.[44] This work exemplified Pauling's ability to think unconventionally; central to the structure was the unorthodox assumption that one turn of the helix may well contain a non-integer number of amino acid residues; for the alpha helix it is 3.7 amino acid residues per turn.

Pauling then proposed that deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was a triple helix;[45][46] his model contained several basic mistakes, including a proposal of neutral phosphate groups, an idea that conflicted with the acidity of DNA. Sir Lawrence Bragg had been disappointed that Pauling had won the race to find the alpha helix structure of proteins. Bragg's team had made a fundamental error in making their models of protein by not recognizing the planar nature of the peptide bond. When it was learned at the Cavendish Laboratory that Pauling was working on molecular models of the structure of DNA, James Watson and Francis Crick were allowed to make a molecular model of DNA. They later benefited from unpublished data from Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin at King's College which showed evidence for a helix and planar base stacking along the helix axis. Early in 1953 Watson and Crick proposed a correct structure for the DNA double helix. Pauling later cited several reasons to explain how he had been misled about the structure of DNA, among them misleading density data and the lack of high quality X-ray diffraction photographs. During the time Pauling was researching the problem, Rosalind Franklin in England was creating the world's best images. They were key to Watson's and Crick's success. Pauling did not see them before devising his mistaken DNA structure, although his assistant Robert Corey did see at least some of them, while taking Pauling's place at a summer 1952 protein conference in England. Pauling had been prevented from attending because his passport was withheld by the State Department on suspicion that he had Communist sympathies. This led to the legend that Pauling missed the structure of DNA because of the politics of the day (this was at the start of the McCarthy period in the United States).[47] Politics did not play a critical role. Not only did Corey see the images at the time, but Pauling himself regained his passport within a few weeks and toured English laboratories well before writing his DNA paper. He had ample opportunity to visit Franklin's lab and see her work, but chose not to.[48]

Pauling also studied enzyme reactions and was among the first to point out that enzymes bring about reactions by stabilizing the transition state of the reaction, a view which is central to understanding their mechanism of action. He was also among the first scientists to postulate that the binding of antibodies to antigens would be due to a complementarity between their structures. Along the same lines, with the physicist turned biologist Max Delbrück, he wrote an early paper arguing that DNA replication was likely to be due to complementarity, rather than similarity, as suggested by a few researchers. This was made clear in the model of the structure of DNA that Watson and Crick discovered.

Molecular genetics

In November 1949, Linus Pauling, Harvey Itano, S. J. Singer and Ibert Wells published "Sickle Cell Anemia, a Molecular Disease"[49] in the journal Science. It was the first proof of a human disease caused by an abnormal protein, and sickle cell anemia became the first disease understood at the molecular level. Using electrophoresis, they demonstrated that individuals with sickle cell disease had a modified form of hemoglobin in their red blood cells, and that individuals with sickle cell trait had both the normal and abnormal forms of hemoglobin. This was also the first demonstration that Mendelian inheritance determined the specific physical properties of proteins, not simply their presence or absence – the dawn of molecular genetics.

Activism

Pauling had been practically apolitical until World War II, but the aftermath of the war and his wife's pacifism changed his life profoundly, and he became a peace activist. During the beginning of the Manhattan Project, Robert Oppenheimer invited him to be in charge of the Chemistry division of the project, but he declined, not wanting to uproot his family. He did work on other projects that had military applications, such as explosives, rocket propellants, an oxygen meter for submarines and the patent of an armor-piercing shell; he was awarded a Presidential Medal of Merit.[50][51] In 1946, he joined the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, chaired by Albert Einstein.[52] Its mission was to warn the public of the dangers associated with the development of nuclear weapons. His political activism prompted the U.S. State Department to deny him a passport in 1952, when he was invited to speak at a scientific conference in London.[53][54] In a speech before the US Senate on June 6 of the same year, Senator Wayne Morse publicly denounced the action of the State Department, and urged the Passport Division to reverse its decision. Pauling and his wife Ava were issued a “limited passport” to attend the aforementioned conference in England.[55][56] His passport was restored in 1954, shortly before the ceremony in Stockholm where he received his first Nobel Prize. Joining Einstein, Bertrand Russell and eight other leading scientists and intellectuals, he signed the Russell-Einstein Manifesto in 1955.[57]

In 1958, Pauling joined a petition drive in cooperation with the founders of the St. Louis Citizen's Committee for Nuclear Information (CNI). This group, headed by Washington University in St. Louis professors Barry Commoner, Eric Reiss, M. W. Friedlander and John Fowler, set up a study of radioactive strontium-90 in the baby teeth of children across North America. The "Baby Tooth Survey," headed by Dr Louise Reiss, demonstrated conclusively in 1961 that above-ground nuclear testing posed significant public health risks in the form of radioactive fallout spread primarily via milk from cows that had ingested contaminated grass.[58][59][60] Pauling also participated in a public debate with the atomic physicist Edward Teller about the actual probability of fallout causing mutations.[61] In 1958, Pauling and his wife presented the United Nations with the petition signed by more than 11,000 scientists calling for an end to the testing of nuclear weapons. Public pressure and the frightening results of the CNI research subsequently led to a moratorium on above-ground nuclear weapons testing, followed by the Partial Test Ban Treaty, signed in 1963 by John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev. On the day that the treaty went into force, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Pauling the Nobel Peace Prize, describing him as "Linus Carl Pauling, who ever since 1946 has campaigned ceaselessly, not only against nuclear weapons tests, not only against the spread of these armaments, not only against their very use, but against all warfare as a means of solving international conflicts."[62] The Committee for Nuclear Information was never credited for its significant contribution to the test ban, nor was the ground-breaking research conducted by Dr Reiss and the "Baby Tooth Survey". The Caltech Chemistry Department, wary of his political views, did not even formally congratulate him. They did throw him a small party, showing they were more appreciative and sympathetic toward his work on radiation mutation. At Caltech he founded Sigma Xi's (The Scientific Research Society) chapter at the school, as he had previously been a member of that organization. He continued his peace activism in the following years co-founding the International League of Humanists in 1974. He was president of the scientific advisory board of the World Union for Protection of Life and also one of the signatories of the Dubrovnik-Philadelphia Statement.

During the 1960s, President Lyndon Johnson’s policy of increasing America’s involvement in the Vietnam War caused an antiwar movement that the Paulings joined with enthusiasm. Pauling denounced the war as unnecessary and unconstitutional. He made speeches, signed protest letters and communicated personally with the North Vietnamese leader, Ho Chi Minh, and gave the lengthy written response to President Johnson. His efforts were ignored by the government.[63] By the time Pauling turned 65 in 1966, he was without a research group or a big scientific issue to focus on. A new generation of more radical, younger activists would march, petition, and lead the movement against the Vietnam War.

Many of Pauling's critics, including scientists who appreciated the contributions that he had made in chemistry, disagreed with his political positions and saw him as a naive spokesman for Soviet communism. He was ordered to appear before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, which termed him "the number one scientific name in virtually every major activity of the Communist peace offensive in this country." A headline in Life magazine characterized his 1962 Nobel Prize as "A Weird Insult from Norway". Pauling was awarded the International Lenin Peace Prize by the USSR in 1970.[64]

Contretemps with William F. Buckley, National Review.

After Pauling had won the Nobel Peace Prize and the Lenin Peace Prize, he became a frequent target of The National Review magazine; particularly, in an article entitled "The Collaborators" in the magazine's July 17, 1962 issue. Pauling was not only referred to as a collaborator, but a "fellow traveler" with proponents of Soviet style communism. These National Review articles set off a three-year legal battle in the form of federal libel case. In 1965, Pauling sued the magazine, its publisher William Rusher, and its editor William F. Buckley, Jr for $1 million. Subsequently, he lost both his suit and the 1968 appeal. The loss of both suits and continued attacks by the National Review did nothing to enhance Pauling's reputation.[65][66][67][68]

Molecular medicine, medical research, and vitamin C advocacy

In 1941, at age 40, Pauling was diagnosed with Bright's disease, a renal disease. Following the recommendations of Thomas Addis, Pauling was able to control the disease with Addis' then-unusual low-protein salt-free diet and vitamin supplements.[69]

In 1951, Pauling gave a lecture entitled "Molecular Medicine".[70] In the late 1950s, Pauling worked on the role of enzymes in brain function, believing that mental illness may be partly caused by enzyme dysfunction. In 1965 Pauling read Niacin Therapy in Psychiatry by Abram Hoffer and theorized vitamins might have important biochemical effects unrelated to their prevention of associated deficiency diseases.[71] In 1968 Pauling published a brief paper in Science entitled "Orthomolecular psychiatry"[72] that gave name and principle to the popular but controversial megavitamin therapy movement of the 1970s. Pauling coined the term "orthomolecular" to refer to the practice of varying the concentration of substances normally present in the body to prevent and treat disease. His ideas formed the basis of orthomolecular medicine, which is not generally practiced by conventional medical professionals and has been strongly criticized.[73][74] His promotion of dietary supplements has also been criticized. In a 2013 article in The Atlantic, pediatrician Paul Offit wrote that although Pauling was "so spectacularly right" that he won two Nobel Prizes, Pauling's late-career assertions about the benefits of dietary supplements were "so spectacularly wrong that he was arguably the world's greatest quack."[75]

Pauling's work on vitamin C in his later years generated much controversy. He was first introduced to the concept of high-dose vitamin C by biochemist Irwin Stone in 1966. After becoming convinced of its worth, Pauling took 3 grams of vitamin C every day to prevent colds.[4] Excited by his own perceived results, he researched the clinical literature and published Vitamin C and the Common Cold in 1970. He began a long clinical collaboration with the British cancer surgeon Ewan Cameron in 1971 on the use of intravenous and oral vitamin C as cancer therapy for terminal patients.[76] Cameron and Pauling wrote many technical papers and a popular book, Cancer and Vitamin C, that discussed their observations. Pauling made vitamin C popular with the public and eventually published two studies of a group of 100 allegedly terminal patients that claimed vitamin C increased survival by as much as four times compared to untreated patients.[77][78] A re-evaluation of the claims in 1982 found that the patient groups were not actually comparable, with the vitamin C group being less sick on entry to the study, and judged to be "terminal" much earlier than the comparison group.[79] Later clinical trials conducted by the Mayo Clinic also concluded that high-dose (10,000 mg) vitamin C was no better than placebo at treating cancer and that there was no benefit to high-dose vitamin C.[80][81][82] The failure of the clinical trials to demonstrate any benefit resulted in the conclusion that vitamin C was not effective in treating cancer; the medical establishment concluding that his claims that vitamin C could prevent colds or treat cancer were quackery.[4][83] Pauling denounced the conclusions of these studies and handling of the final study as "fraud and deliberate misrepresentation",[84][85] and criticized the studies for using oral, rather than intravenous vitamin C[86] (which was the dosing method used for the first ten days of Pauling's original study[83]). Pauling also criticised the Mayo clinic studies because the controls were taking vitamin C during the trial, and because the duration of the treatment with vitamin C was short; Pauling advocated continued high dose vitamin C for the rest of the cancer patient's life whereas the Mayo clinic patients in the second trial were treated with vitamin C for a median of 2.5 months.[87] The results were publicly debated at length with considerable acrimony between Pauling and Cameron, and Moertel (the lead author of the Mayo Clinic studies), with accusations of misconduct and scientific incompetence on both sides. Ultimately the negative findings of the Mayo Clinic studies ended general interest in vitamin C as a treatment for cancer.[85] Despite this, Pauling continued to promote vitamin C for treating cancer and the common cold, working with The Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential to use vitamin C in the treatment of brain-injured children.[88] He later collaborated with the Canadian physician Abram Hoffer on a micronutrient regime, including high-dose vitamin C, as adjunctive cancer therapy.[89] A 2009 review also noted differences between the studies, such as the Mayo clinic not using intravenous Vitamin C, and suggested further studies into the role of vitamin C when given intravenously.[90] Currently, the available evidence does not support a role for high dose vitamin C in the treatment of cancer.[91]

With Arthur B. Robinson and another colleague, Pauling founded the Institute of Orthomolecular Medicine in Menlo Park, California, in 1973, which was soon renamed the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine. Pauling directed research on vitamin C, but also continued his theoretical work in chemistry and physics until his death. In his last years, he became especially interested in the possible role of vitamin C in preventing atherosclerosis and published three case reports on the use of lysine and vitamin C to relieve angina pectoris. In 1996, the Linus Pauling Institute moved from Palo Alto, California, to Corvallis, Oregon, to become part of Oregon State University, where it continues to conduct research on micronutrients, phytochemicals (chemicals from plants), and other constituents of the diet in preventing and treating disease. Several researchers that had previously worked at the Linus Pauling Institute in Palo Alto, including the assistant director of research, moved on to form the Genetic Information Research Institute.

Structure of the atomic nucleus

On September 16, 1952, Pauling opened a new research notebook with the words "I have decided to attack the problem of the structure of nuclei."[92] On October 15, 1965, Pauling published his Close-Packed Spheron Model of the atomic nucleus in two well respected journals, Science and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.[93] For nearly three decades, until his death in 1994, Pauling published numerous papers on his spheron cluster model.[94][95][96][97][98][99]

The basic idea behind Pauling's spheron model is that a nucleus can be viewed as a set of "clusters of nucleons". The basic nucleon clusters include the deuteron [np], helion [pnp], and triton [npn]. Even–even nuclei are described as being composed of clusters of alpha particles, as has often been done for light nuclei.[citation needed] Pauling attempted to derive the shell structure of nuclei from pure geometrical considerations related to Platonic solids rather than starting from an independent particle model as in the usual shell model. In an interview given in 1990 Pauling commented on his model:[100]

Now recently, I have been trying to determine detailed structures of atomic nuclei by analyzing the ground state and excited state vibrational bends, as observed experimentally. From reading the physics literature, Physical Review Letters and other journals, I know that many physicists are interested in atomic nuclei, but none of them, so far as I have been able to discover, has been attacking the problem in the same way that I attack it. So I just move along at my own speed, making calculations...

Legacy

Pauling died of prostate cancer on August 19, 1994, at 19:20 at home in Big Sur, California. He was 93 years old.[101][102] A grave marker for him is in Oswego Pioneer Cemetery in Lake Oswego, Oregon.[102][103] Pauling’s ashes, along with those of his wife, were moved from Big Sur to the Oswego Pioneer Cemetery in 2005.[104]

Pauling was included in a list of the 20 greatest scientists of all time by the magazine New Scientist, with Albert Einstein being the only other scientist from the 20th century on the list. Pauling is notable for the diversity of his interests: quantum mechanics, inorganic chemistry, organic chemistry, protein structure, molecular biology, and medicine. In all these fields, and especially on the boundaries between them, he made decisive contributions. His work on chemical bonding marks the beginning of modern quantum chemistry, and many of his contributions like hybridization and electronegativity have become part of standard chemistry textbooks. While his valence bond approach fell short of accounting quantitatively for some of the characteristics of molecules, such as the photoelectron spectra of many molecules, and would later be eclipsed by the molecular orbital theory of Robert Mulliken, Valence Bond Theory still competes, in its modern form, with both Molecular Orbital Theory and density functional theory (DFT) for describing the chemical phenomena.[105] Pauling's work on crystal structure contributed significantly to the prediction and elucidation of the structures of complex minerals and compounds.[citation needed] His discovery of the alpha helix and beta sheet is a fundamental foundation for the study of protein structure.[citation needed]

Francis Crick acknowledged Pauling as the "father of molecular biology"[106] His discovery of sickle cell anemia as a "molecular disease" opened the way toward examining genetically acquired mutations at a molecular level.[citation needed]

Pauling's work on the molecular basis of disease and its treatment is being carried on by a number of researchers, notably those at the Linus Pauling Institute, which lists a dozen principal investigators and faculty who study the role of micronutrients and phytochemicals in health and disease.

Items named after Pauling include Pauling Street in Foothill Ranch, California,[107] Linus Pauling Drive in Hercules, California, Linus and Ava Helen Pauling Hall at Soka University of America in Aliso Viejo, California, Linus Pauling Middle School in Corvallis, Oregon, and Pauling Field, a small airfield located in Condon, Oregon, where Pauling spent his youth. Additionally, the Linus Pauling Institute[108] and also a wing of The Valley Library at Oregon State University bear his name. There is a psychedelic rock band in Houston, Texas, named The Linus Pauling Quartet.

The Caltech Chemistry Department renamed room 22 of Gates Hall the Linus Pauling Lecture Hall, since Linus spent so much time there.

Linus Torvalds, developer of the Linux kernel, is named after Pauling.[109]

On March 6, 2008, the United States Postal Service released a 41 cent stamp honoring Pauling designed by artist Victor Stabin.[110] His description reads: "A remarkably versatile scientist, structural chemist Linus Pauling (1901–1994) won the 1954 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for determining the nature of the chemical bond linking atoms into molecules. His work in establishing the field of molecular biology; his studies of hemoglobin led to the classification of sickle cell anemia as a molecular disease." The other scientists on this sheet include Gerty Cori, biochemist, Edwin Hubble, astronomer, and John Bardeen, physicist.

California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver announced on May 28, 2008 that Pauling would be inducted into the California Hall of Fame, located at The California Museum for History, Women and the Arts. The induction ceremony took place December 15, 2008. Pauling's son was asked to accept the honor in his place.

Nobel laureate Peter Agre has said that Linus Pauling inspired him.[111]

Quasicrystals

Pauling was a stubborn opponent of the idea of quasicrystals, relentlessly attacking Shechtman; Pauling is quoted as saying "There is no such thing as quasicrystals, only quasi-scientists."[112] Shechtman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011 for his work on quasicrystals.

Honors and awards

Pauling received numerous awards and honors during his career, including the following:[113][114]

- 1931 ACS Award in Pure Chemistry [115]

- 1931 Irving Langmuir Award, American Chemical Society.[113][114]

- 1941 Nichols Medal, New York Section, American Chemical Society.[113]

- 1946 Willard Gibbs Award, Chicago section of the American Chemical Society.[114]

- 1947 Davy Medal, Royal Society.[113][114]

- 1947 T. W. Richards Medal, Northeastern Section of the American Chemical Society.[114]

- 1948 Presidential Medal for Merit by President Harry S. Truman of the United States.[113][114]

- 1948 Elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society of London (ForMemRS)[4]

- 1951 Gilbert N. Lewis medal, California section of the American Chemical Society.[114]

- 1952 Pasteur Medal, Biochemical Society of France.[113]

- 1954 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[113][114]

- 1955 Addis Medal, National Nephrosis Foundation.[113][114]

- 1955 John Phillips Memorial Award, American College of Physicians.[113][114]

- 1956 Avogadro Medal, Italian Academy of Science.[113][114]

- 1957 Paul Sabatier Medal.

- 1957 Pierre Fermat Medal in Mathematics (awarded for only the sixth time in three centuries).[113][114][116]

- 1957 International Grotius Medal.[113]

- 1961 Humanist of the Year, American Humanist Association.

- 1961 Gandhi Peace Award by Promoting Enduring Peace.[117]

- 1962 Nobel Peace Prize.[113][114]

- 1965 Medal, Academy of the Rumanian People's Republic.[113]

- 1966 Linus Pauling Award.[113]

- 1966 Silver Medal, Institute of France.[113]

- 1966 Supreme Peace Sponsor, World Fellowship of Religion.[113]

- 1967 Washington A. Roebling Medal, Mineralogical Society of America.[114]

- 1972 Lenin Peace Prize.[113]

- 1974 National Medal of Science by President Gerald R. Ford of the United States.[114]

- 1978 Lomonosov Gold Medal, Presidium of the Academy of the USSR.[113][114]

- 1979 NAS Award in Chemical Sciences, National Academy of Sciences.[113][118]

- 1981 John K. Lattimer Award, American Urological Association.[114]

- 1984 Priestley Medal, American Chemical Society.[113][114]

- 1984 Award for Chemistry, Arthur M. Sackler Foundation.[113]

- 1986 Lavoisier Medal by Fondation de la Maison de la Chimie.[114]

- 1987 Award in Chemical Education, American Chemical Society.[113]

- 1989 Vannevar Bush Award, National Science Board.[113][114]

- 1990 Richard C. Tolman Medal, American Chemical Society Southern California Section.[113]

- 1992 Daisaku Ikeda Medal, Soka Gakkai International[114]

- 2008 "American Scientists" U.S. postage stamp series, $0.41, for his sickle cell disease work.[119]

Publications

Books

- Pauling, Linus (1939). The Nature of the Chemical Bond and the Structure of Molecules and Crystals. Cornell University Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Pauling, Linus (1947). General Chemistry: An Introduction to Descriptive Chemistry and Modern Chemical Theory. W. H. Freeman.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help)- Greatly revised and expanded in 1947, 1953, and 1970. Reprinted by Dover Publications in 1988.

- Pauling, Linus; Hayward, Roger (1964). The Architecture of Molecules. San Francisco: Freeman. ISBN 978-0716701583.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - — (1958). No more war!. Dodd, Mead & Co. ISBN 978-1124119663.

- Pauling, Linus (1977). Vitamin C, the Common Cold and the Flu. W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0360-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Pauling, Linus (1987). How to Live Longer and Feel Better. Avon. ISBN 0-380-70289-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Pauling, Linus; Wilson, E. B. (1985). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics with Applications to Chemistry. Dover. ISBN 0-486-64871-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Cameron, E.; Pauling, Linus (1993). Cancer and Vitamin C: A Discussion of the Nature, Causes, Prevention, and Treatment of Cancer With Special Reference to the Value of Vitamin C. Camino. ISBN 0-940159-21-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask2=ignored (|author-mask2=suggested) (help) - Pauling, Linus (1998). Linus Pauling On Peace: A Scientist Speaks Out on Humanism and World Survival. Rising Star Press. ISBN 0-933670-03-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Hoffer, Abram; Pauling, Linus (2004). Healing Cancer: Complementary Vitamin & Drug Treatments. Toronto: CCNM Press. ISBN 978-1897025116.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask2=ignored (|author-mask2=suggested) (help) - Ikeda, Daisaku; Pauling, Linus (2008). A Lifelong Quest for Peace: A Dialogue. Richard L. Gage (ed., trans.). London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-889-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask2=ignored (|author-mask2=suggested) (help)

Journal articles

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1098/rspa.1927.0035, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1098/rspa.1927.0035instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/ja01379a006, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/ja01379a006instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/ja01355a027, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/ja01355a027instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/ja01360a004, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/ja01360a004instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/ja01342a022, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/ja01342a022instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/ja01348a011, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/ja01348a011instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1063/1.1749304 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1063/1.1749304instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/ja01315a102, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/ja01315a102instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/ja01867a018, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/ja01867a018instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/ja01195a024, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/ja01195a024instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.110.2865.543, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.110.2865.543instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1073/pnas.37.4.205, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1073/pnas.37.4.205instead.

See also

- List of peace activists

- 1920 US Census with Pauling in Portland, Oregon.

References

- ^ a b c Linus Pauling at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ a b "A Guggenheim Fellow in Europe during the Golden Years of Physics (1926-1927)". Special collections. Oregon State University Libraries. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Pauling, Linus (1925). The determination with x-rays of the structures of crystals (PhD thesis). California Institute of Technology.

- ^ a b c d e f Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1098/rsbm.1996.0020, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1098/rsbm.1996.0020instead. - ^ "The Scientific 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Scientists, Past and Present". Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- ^ Horgan, J (1993). "Profile: Linus C. Pauling – Stubbornly Ahead of His Time". Scientific American. 266 (3): 36–40. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0393-36.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 8090196, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=8090196instead. - ^ As Watson attests, Pauling also came close to being the discoverer of DNA's structure, for which Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins received the Nobel Prize.

- ^ "Linus Pauling's Childhood (1901-1910)". Special collections. Oregon State University Libraries. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "Linus Pauling". NNDB: Tracking the entire world. Soylent Communications. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ Hager, p. 22.

- ^ Mead and Hager, p. 8.

- ^ http://web.massar.org/genealogy/Application%20Preparation%20Manual-2013-10-02.pdf

- ^ a b Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 4.

- ^ Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 5.

- ^ Mead and Hager, p. 9.

- ^ Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 17.

- ^ Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 21.

- ^ Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 22.

- ^ Hager, p. 48.

- ^ "Linus Pauling – Biography". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ Bourgoin, Suzanne M.; Paula K. Byers (1998). Encyclopedia of World Biography. Thomson Gale. Vol. 12, p. 150. ISBN 0-7876-2221-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 23.

- ^ Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 24.

- ^ Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 25.

- ^ Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 26.

- ^ Swanson, Stephen (October 3, 2000). "OSU fraternity to donate Pauling treasures to campus library". Oregon State University. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ a b Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 29.

- ^ Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 30.

- ^ Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 31.

- ^ "Caltech Commencement Program" (PDF). Caltech Campus Publications. June 12, 1925. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ^ "Linus Pauling: A Biographical Timeline". Linus Pauling Institute. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ "The Linus Pauling Papers: Biographical Information". United States National Library of Medicine. n.d. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ "Linus Pauling Biography". Linus Pauling Institute. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ Linus Pauling & Daisaku Ikeda (1992). A Lifelong Quest for Peace: A Dialogue. Jones & Bartlett. p. 22. ISBN 0-86720-277-7.

...I [Pauling] am not, however, militant in my atheism. The great English theoretical physicist Paul Dirac is a militant atheist. I suppose he is interested in arguing about the existence of God. I am not. It was once quipped that there is no God and Dirac is his prophet.

- ^ Tom Hager (December 2004). "The Langmuir Prize". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- ^ Linus Pauling (March 1932). "The nature of the chemical bond. III. The transition from one extreme bond type to another". Journal of the American Chemical Society. Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- ^ Thomas Hager (1995). Force of Nature: The Life of Linus Pauling. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80909-5., pp. 152

- ^ Thomas Hager (December 2004). "The Nature of the Chemical Bond". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- ^ Linus Pauling (1928). "London's paper. General ideas on bonds". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- ^ Linus Pauling (1930s). "Notes and Calculations re: Electronegativity and the Electronegativity Scale". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- ^ Linus Pauling (January 6, 1934). "Benzene". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- ^ Linus Pauling (July 29, 1946). "Resonance". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- ^ Pauling, L; Corey, RB (1951). "Configurations of Polypeptide Chains With Favored Orientations Around Single Bonds: Two New Pleated Sheets". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 37 (11): 729–40. Bibcode:1951PNAS...37..729P. doi:10.1073/pnas.37.11.729. PMC 1063460. PMID 16578412.

- ^ "Linus Pauling's DNA Model". Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ^ Pauling L, Corey RB (February 1953). "A Proposed Structure For The Nucleic Acids". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 39 (2): 84–97. Bibcode:1953PNAS...39...84P. doi:10.1073/pnas.39.2.84. PMC 1063734. PMID 16578429.

- ^ "Pauling biography citing State Department's revocation of Pauling's passport in 1952". Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ^ Hager, Thomas (1995). Force of Nature: The Life of Linus Pauling. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80909-5., pp. 414–415

- ^ Pauling, Linus; Harvey Itano; S. J. Singer; Ibert Wells (November 1949). "Sickle Cell Anemia, a Molecular Disease". Science. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ "The Linus Pauling Papers: Biographical Information". United States National Library of Medicine. Retrieved February 11, 2008.

- ^ Paulus, John Allen (November 5, 1995). "Pauling's Prizes". New York Times. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- ^ Thomas Hager (November 29, 2007). "Einstein". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ "Linus Pauling". Retrieved December 11, 2007.

[In] January of 1952, Pauling requested a passport to attend a meeting in England ... The passport was denied because granting it "would not be in the best interest of the United States." He applied again and wrote President Eisenhower, asking him to arrange the issuance of the passport since, "I am a loyal citizen of the United States. I have never been guilty of any unpatriotic or criminal act."

- ^ Linus Pauling (May 1952). "The Department of State and the Structure of Proteins". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ Robert Paradowski (2011), Oregon State University, Special Collections p.18, Proteins, Passports, and the Prize (1950-1954), retrieved February 1, 2013

- ^ Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Vol. VIII, Nr. 7 (Okt. 1952) p. 254, Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, Inc.

- ^ Thomas Hager (November 29, 2007). "Russell/Einstein". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ Louise Zibold Reiss (November 24, 1961). "Strontium-90 Absorption by Deciduous Teeth: Analysis of teeth provides a practicable method of monitoring strontium-90 uptake by human populations" (PDF). Science. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- ^ Thomas Hager (November 29, 2007). "Strontium-90". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ Thomas Hager (November 29, 2007). "The Right to Petition". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ Linus Pauling; Edward Teller (1958). "Teller vs. Pauling". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ Linus Pauling (October 10, 1963). "Notes by Linus Pauling. October 10, 1963". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ "Linus Pauling and the International Peace Movement: Vietnam". Oregon State University Libraries. 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Stephen F Mason (July 1999). "The Science and Humanism of Linus Pauling (1901–1994)". Ciencia Abierta. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- ^ "The National Review Lawsuit". Paulingblog. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ "A Tough Conclusion to the National Review Lawsuit". Paulingblog. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ "Pauling v. NAT'L REVIEW, INC". Justia.com. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ "http://www.nytimes.com/1998/08/30/nyregion/c-dickerman-williams-97-free-speech-lawyer-is-dead.html". The New York Times. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ Peitzman, Steven J. (2007). Dropsy, dialysis, transplant: a short history of failing kidneys. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 72–8, 190. ISBN 0-8018-8734-8.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (October 1951). "Molecular Medicine". Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Papers. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ Nicolle, Lorraine; Beirne, Ann Woodriff, eds. (2010). Biochemical imbalances in disease a practitioner's handbook. London: Singing Dragon. p. 27. ISBN 9780857010285.

- ^ Pauling L (April 1968). "Orthomolecular psychiatry. Varying the concentrations of substances normally present in the human body may control mental disease". Science. 160 (3825): 265–71. Bibcode:1968Sci...160..265P. doi:10.1126/science.160.3825.265. PMID 5641253.

- ^ Cassileth, BR (1998:67). Alternative Medicine Handbook: the Complete Reference Guide to Alternative and Complementary Therapies. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ "Vitamin Therapy, Megadose / Orthomolecular Therapy". BC Cancer Agency. February 2000. Archived from the original on February 2, 2007. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ Paul Offit (July 19, 2013). "The Vitamin Myth: Why We Think We Need Supplements". The Atlantic. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Ewan Cameron M.D. "Cancer bibliography". Doctoryourself.com. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ Cameron E, Pauling L (October 1976). "Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: Prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 73 (10): 3685–9. Bibcode:1976PNAS...73.3685C. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.10.3685. PMC 431183. PMID 1068480.

- ^ Cameron E, Pauling L (September 1978). "Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: Reevaluation of prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 75 (9): 4538–42. Bibcode:1978PNAS...75.4538C. doi:10.1073/pnas.75.9.4538. PMC 336151. PMID 279931.

- ^ DeWys, WD (1982). "How to evaluate a new treatment for cancer". Your Patient and Cancer. 2 (5): 31–36.

- ^ Creagan ET, Moertel CG, O'Fallon JR; et al. (September 1979). "Failure of high-dose vitamin C (ascorbic acid) therapy to benefit patients with advanced cancer. A controlled trial". The New England Journal of Medicine. 301 (13): 687–90. doi:10.1056/NEJM197909273011303. PMID 384241.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Creagan ET, Rubin J, O'Connell MJ, Ames MM (January 1985). "High-dose vitamin C versus placebo in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer who have had no prior chemotherapy. A randomized double-blind comparison". The New England Journal of Medicine. 312 (3): 137–41. doi:10.1056/NEJM198501173120301. PMID 3880867.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tschetter, L; et al. (1983). "A community-based study of vitamin C (ascorbic acid) in patients with advanced cancer". Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2: 92.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author2=(help) - ^ a b Chen, Q; et al. (2007). "Ascorbate in pharmacologic concentrations selectively generates ascorbate radical and hydrogen peroxide in extracellular fluid in vivo". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (21): 8749–54. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.8749C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702854104. PMC 1885574. PMID 17502596.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author2=(help) - ^ Ted Goertzel (1996). "Analyzing Pauling's Personality: A Three Generational, Three Decade Project". Special Collections, Oregon State University Libraries. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ a b Trevor Pinch; Collins, Harry M. (2005). "Alternative Medicine: The Cases of Vitamin C and Cancer". Dr. Golem: how to think about medicine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 89–111. ISBN 0-226-11366-3.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Levine M; et al. (2006). "Intravenously administered vitamin C as cancer therapy: three cases". CMAJ. 174 (7): 937–942. doi:10.1503/cmaj.050346. PMC 1405876. PMID 16567755. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Linus Pauling (1986). How to Live Longer and Feel Better. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 173–175. ISBN 0-7167-1781-6.

- ^ Pauling, L (November 1978). Ralph Pelligra, ed. (ed.). "Orthomolecular enhancement of human development" (PDF). Human Neurological Development: 47–51.

{{cite journal}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ Andrew W. Saul; Dr. Abram Hoffer. "Abram Hoffer, M.D., PhD 50 Years of Megavitamin Research, Practice and Publication". Doctoryourself.com. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ Template:Cite PMID

- ^ "Vitamin C". American Cancer Society.

- ^ "Oregon State Special Collections". Osulibrary.oregonstate.edu. February 28, 2002. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (October 1965). "The close-packed-spheron theory and nuclear fission". Science. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (October 1965). "The close-packed spheron model of atomic nuclei and its relation to the shell model". Science. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (July 1966). "The close-packed-spheron theory of nuclear structure and the neutron excess for stable nuclei (Dedicated to the seventieth anniversary of Professor Horia Hulubei)". Science. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (December 1967). "Magnetic-moment evidence for the polyspheron structure of the lighter atomic nuclei". Science. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (November 1969). "Orbiting clusters in atomic nuclei". Science. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ Pauling, Linus; Arthur B. Robinson (1975). "Rotating clusters in nuclei". Canadian Journal of Physics. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (February 1991). "Transition from one revolving cluster to two revolving clusters in the ground-state rotational bands of nuclei in the lanthanon region". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 88. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ "Linus Pauling Interview – page 9 / 9 – Academy of Achievement". Achievement.org. February 29, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- ^ Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 247.

- ^ a b Linus Pauling dies at 93. The Oregonian, August 20, 1994.

- ^ Linus Carl Pauling at Find a Grave

- ^ "The Centennial: Who's Buried in Linus Pauling's Grave?" (PDF). Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- ^ Hoffmann, Roald; Shaik, Sason; Hiberty, Philippe C. (2003). "A Conversation on VB vs MO Theory: A Never-Ending Rivalry?". ACS Publications. pp. 750–756. doi:10.1021/ar030162a.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "Pauling Honored by Scientists at Caltech Event". Los Angeles Times. United Press International. March 1, 1986. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ The street in Foothill Ranch was once home to vitamin C/Emergen-C maker Alacer Corp. Founder Jay Patrick was a friend of Linus Pauling.

- ^ "Linus Pauling Institute". Lpi.oregonstate.edu. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- ^ Moody, Glyn (2002). Rebel Code: Linux and the Open Source Revolution. Perseus Books Group. p. 336. ISBN 0-7382-0670-9.

- ^ Odegard, Kyle (March 7, 2008). "Linus Pauling stamp debuts at university". Gazette-Times.

- ^ Agre, Peter (December 10, 2013). "Fifty years ago: Linus Pauling and the belated Nobel Peace Prize". Science & Diplomacy. 2 (4).

- ^ Lannin, Patrick (October 5, 2011). "Ridiculed crystal work wins Nobel for Israeli". Reuters. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Pauling interview by Jeffrey L. Sturchio (1987) Chemical Heritage Foundation (click on Honors to see list)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Linus Pauling: Awards, Honors and Medals". Special Collections. Oregon State University Libraries. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "ACS Award in Pure Chemistry". American Chemical Society. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Pauling's awards and medals (includes image of Fermat medal).

- ^ "Gandhi Peace Award". Promoting Enduring Peace. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ^ "NAS Award in Chemical Sciences". National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ "OSU Celebrates Linus Pauling and Release of New U.S. Postal Service Stamp". Events. Oregon State University. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

Notes

- Goertzel, Ted; Goertzel, Ben (1995). Linus Pauling: A Life in Science and Politics. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-00672-8.

- Hager, Thomas (1995). Force of Nature: The Life of Linus Pauling. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80909-5.

- Hager, Thomas (1998). Linus Pauling and the Chemistry of Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513972-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Marinacci, Barbara; Krishnamurthy, Ramesh (1998). Linus Pauling on Peace. Rising Star Press. ISBN 0-933670-03-6.

- Mead, Clifford; Hager, Thomas, eds. (2001). Linus Pauling: Scientist and Peacemaker. Oregon State University Press. ISBN 0-87071-489-9.

- Serafini, Anthony (1989). Linus Pauling: A Man and His Science. Paragon House. ISBN 1-55778-440-X.

Further reading

- Coffey, Patrick (2008). Cathedrals of Science: The Personalities and Rivalries That Made Modern Chemistry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532134-0.

- Davenport, Derek A. (1996). "The Many Lives of Linus Pauling: A Review of Reviews". Journal of Chemical Education. 73 (9): A210. Bibcode:1996JChEd..73..210D. doi:10.1021/ed073pA210. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- Hargittai, István (2000). Hargittai, Magdolna (ed.). Candid science: conversations with famous chemists (Reprinted ed.). London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1860941511.

- Marinacci, Barbara, ed. (1995). Linus Pauling: In His Own Words; Selected Writings, Speeches, and Interviews. Introduction by Linus Pauling. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0684813875.

- Pauling, Linus (April 6, 1987). Written at Denver. "Linus Pauling" (Interview). Interviewed by Jeffrey L. Sturchio. Philadelphia: Chemical Heritage Foundation. Oral History Transcript # 0067.

{{cite interview}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|callsign=and|subjectlink=(help)

External links

- Linus Pauling Online a Pauling portal created by Oregon State University Libraries

- Francis Crick: The Impact of Linus Pauling on Molecular Biology (transcribed video from the 1995 Oregon State University symposium)

- The Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Papers at the Oregon State University Libraries

- The Pauling Catalogue

- The Pauling Blog

- Linus Pauling (1901–1994)

- Caltech oral history interview

- Berkeley Conversations With History interview

- Linus Pauling Centenary Exhibit

- Linus Pauling from The Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography

- Linus Pauling Investigates Vitamin C

- The Linus Pauling Institute at Oregon State University

- Pauling's CV

- Publications of Pauling

- Linus and Ava Helen Pauling Hall at Soka University of America, devoted to pacifism in global citizenship.

- The Linus Pauling Papers – Profiles in Science, National Library of Medicine

- Linus Pauling Documentary produced by Oregon Public Broadcasting

- Template:Worldcat id

- All articles with faulty authority control information

- 1901 births

- 1994 deaths

- 20th-century American chemists

- American anti-war activists

- American anti–nuclear weapons activists

- American atheists

- American biochemists

- American biophysicists

- American chemists

- American humanists

- American Nobel laureates

- American pacifists

- American people of Canadian descent

- American people of English descent

- American people of German descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American physical chemists

- California Institute of Technology alumni

- California Institute of Technology faculty

- Inorganic chemists

- Lenin Peace Prize recipients

- Medal for Merit recipients

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- National Academy of Sciences laureates

- National Medal of Science laureates

- Nobel laureates in Chemistry

- Nobel laureates with multiple Nobel awards

- Nobel Peace Prize laureates

- People from Portland, Oregon

- Recipients of the Lomonosov Gold Medal

- Theoretical chemists

- Vannevar Bush Award recipients

- Guggenheim Fellows

- People associated with the Human Potential Movement

- Washington High School (Portland, Oregon) alumni

- Deaths from prostate cancer