Religion in Pakistan

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Traditions |

| folklore |

| Sport |

The official religion of Pakistan is Islam, as enshrined by Article 2 of the Constitution, and is practised by approximately 96.47% of the country's population.[1][7] The remaining less than 4% practice Hinduism, Christianity, Ahmadiyya, Sikhism and other religions.[8][9] A few aspects of Secularism have also been adopted by Pakistani constitution from British colonial concept.[10][11][12][13][8] However, religious minorities in Pakistan often face significant discrimination, subject to issues such as violence and the blasphemy laws.[14][15]

Muslims comprise a number of sects: the majority practice Sunni Islam (estimated at 85–90%), while a minority practice Shia Islam (estimated at 10–15%).[16][17][18] Most Pakistani Sunni Muslims belong to the Hanafi school of jurisprudence, which is represented by the Barelvi and Deobandi traditions.[8] However, the Hanbali school is gaining popularity recently due to Wahhabi influence from the Middle East.[19] The majority of Pakistani Shia Muslims belong to the Twelver Islamic law school, with significant minority groups who practice Ismailism, which is composed of Nizari (Aga Khanis), Mustaali, Dawoodi Bohra, Sulaymani, and others.

Before the arrival of Islam beginning in the 8th century, the region compromising Pakistan was home to a diverse plethora of faiths, including Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Zoroastrianism.[20][21]

Constitutional provisions

The Constitution of Pakistan establishes Islam as the state religion,[22] and provides that all citizens have the right to profess, practice and propagate their religion subject to law, public order, and morality.[23] The Constitution also states that all laws are to conform with the injunctions of Islam as laid down in the Quran and Sunnah.[24]

The Constitution limits the political rights of Pakistan's non-Muslims. Only Muslims are allowed to become the President[25] or the Prime Minister.[26] Only Muslims are allowed to serve as judges in the Federal Shariat Court, which has the power to strike down any law deemed un-Islamic, though its judgments can be overruled by the Supreme Court of Pakistan.[27] However, non-Muslims have served as judges in the High Courts and Supreme Court.[28] In 2019, Naveed Amir, a Christian member of National assembly moved a bill to amend the article 41 and 91 of the Constitution which would allow non-Muslims to become Prime Minister and President of Pakistan. However, Pakistan's parliament blocked the bill.[29]

Secularism

Aspects & Practices of secularism

There was a petition in Supreme Court of Pakistan in the year of 2015 by 17 judges to declare the nation as a "Secular state" officially.[30] Muhammad Ali Jinnah (the founder of Pakistan) wanted Pakistan to be a secular, democratic, and a liberal republic.[31] Pakistan was secular from 1947 to 1955 and after that, Pakistan adopted a constitution in 1956, becoming an Islamic republic with Islam as its state religion.[32]

The main principles of Secularism in the Pakistani constitution were incorporated in its fundamental rights which were granted under various articles of 20, 21, 22 & 25 of the constitution[33] -

(a) Article 20 : Freedom to profess religion and to manage religious institutions.[34]

(b) Article 21 : Safeguard against taxation for purposes of any particular religion.[35]

(c) Article 22 : Safeguards as to educational institutions in respect of religion, etc.[36]

(d) Article 25 : Equality of citizens.[37]

Demographics of religion in Pakistan

Pre-partition era

Pakistan had an estimated population of 33 million during (1947) just before partition, of which nearly 22.77 million were Muslims constituting (69%) of the Pakistan's population, about 7.92 million Hindus were living in this region just constituting 24% of the population as a second largest community and were mainly concentrated in Sindh and Punjab. Sikhs are third largest community with a population of about 2 million comprising 6% of the region's population and were mainly concentrated in Punjab.[40]

1951 census

Religion in Pakistan (1951 Official census)[41]

After partition, when first census of Pakistan was conducted in the year 1951, It was found that the Muslim percentage as a total population have increased from 69% in 1947 to 97.1% in 1951, within four years leading to overwhelming Muslim majority to the nation,[42] as because the 1947 Partition of India gave rise to bloody rioting and indiscriminate inter-communal killing of Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs across the Indian subcontinent. As a result, around 7.2 million Hindus and Sikhs moved to India and 7.5 million Muslims moved to Pakistan permanently, leading to demographic change of both the nations to a certain extent.[43]

2017 census

| Religion | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| Muslims ( |

200,352,754 | 96.47% |

| Hindus ( |

4,444,437 | 2.14% |

| Christians ( |

2,637,586 | 1.27% |

| Ahmadiyyas | 207,688 | 0.09% |

| Sikhs ( |

20,768 | 0.01% |

| Others (inc. Zoroastrians, Baháʼís, Buddhists, Irreligious) | 20,767 | 0.01% |

| Total | 207,684,000 | 100% |

As per 2017 Census of Pakistan, the country has a population of 207,684,000.The CCI approved the release of provisional population figures of 207.754 million people. The final results showed the total population of Pakistan to be 207.684 million, a reduction of 68,738 people or 0.033% against provisional results,[44] Pakistan has a population of 224,418,238 as of 2021.[45]

As of 2018, there are 3.63 million non-Muslim voters in Pakistan- 1.77 million were Hindus, 1.64 million Christians, 167,505 were Ahmadi Muslims, 31,543 were Baháʼís, 8,852 were Sikhs, 4,020 were Parsis, 1,884 were Buddhist and others such as Kalashas.[46] The NADRA makes it nearly impossible to declare and change the religion to anything from Islam making the statistics somewhat misleading.[47]

Details

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics released religious data of Pakistan Census 2017 on 19 May 2021.[48] 96.47% are Muslims, followed by 2.14% Hindus, 1.27% Christians, 0.09% Ahmadis and 0.02% others.

These are some maps of religious minority groups. The 2017 census showed an increasing share in Hinduism, mainly caused by a higher birth rate among the impoverished Hindus of Sindh province. This census also recorded Pakistan's first Hindu-majority district, called Umerkot District, where Muslims were previously the majority.

On the other hand, Christianity in Pakistan, while increasing in raw numbers, has fallen significantly in percentage terms since the last census. This is due to Pakistani Christians having a significantly lower fertility rate than Pakistani Muslims and Pakistani Hindus as well as them being concentrated in the most developed parts of Pakistan, Lahore District (over 5% Christian), Islamabad Capital Territory (over 4% Christian), and Northern Punjab.

The Ahmadiyya movement shrunk in size (both raw numbers and percentage) between 1998 and 2017, while remaining concentrated in Lalian Tehsil, Chiniot District, where approximately 13% of the population is Ahmadiyya.

Here are some maps of Pakistan's religious minority groups as of the 2017 census by district:

Virtually all people not belonging to one of these minority groups were Sunni or Shia Muslim, with the most religiously homogeneous areas found in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Demographics of religion by province/territory

Punjab

| Religion | Population (1941)[49]: 42 |

% (1941) |

Population (2017)[4] |

% (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam |

12,983,076 | 75% | 107,559,164 | 97.77% |

| Hinduism |

2,376,309 | 13.73% | 220,024 | 0.2% |

| Sikhism |

1,527,345 | 8.82% | N/A | N/A |

| Christianity |

382,669 | 2.21% | 2,068,233 | 1.88% |

| Others[c] | 40,458 | 0.23% | 3,455 | 0% |

| Total Population | 17,309,857 | 100% | 110,012,442 | 100% |

Sindh

| Religion | Population (1941)[50]: 28 |

% (1941) |

Population (2017)[4] |

% (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam |

3,208,325 | 70.75% | 43,255,768 | 90.39% |

| Hinduism |

1,229,926 | 27.12% | 4,176,986 | 8.73% |

| Tribal | 36,819 | 0.81% | N/A | N/A |

| Sikhism |

31,011 | 0.68% | 10,000[51] | 0.02% |

| Christianity |

20,209 | 0.45% | 408,301 | 0.85% |

| Zoroastrianism | 3,838 | 0.08% | N/A | N/A |

| Jainism | 3,687 | 0.08% | N/A | N/A |

| Judaism | 1,082 | 0.02% | N/A | N/A |

| Buddhism | 111 | 0% | N/A | N/A |

| Others | 0 | 0% | 3,455 | 0.01% |

| Total Population | 4,535,008 | 100% | 47,854,510 | 100% |

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

| Religion | Population (1881)[52]: 95 |

% (1881) |

Population (1891)[52]: 95 |

% (1891) |

Population (1901)[52]: 95 |

% (1901) |

Population (1911)[52]: 95 |

% (1911) |

Population (1941)[53]: 22 |

% (1941) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam |

1,451,444 | 92.1% | 1,714,490 | 92.3% | 1,882,294 | 92.2% | 2,039,894 | 92.86% | 2,788,797 | 92.52% |

| Hinduism |

111,892 | 7.1% | 118,881 | 6.4% | 128,617 | 6.3% | 119,942 | 5.46% | 180,321 | 5.94% |

| Sikhism |

7,880 | 0.5% | 18,575 | 1% | 26,540 | 1.3% | 30,345 | 1.38% | 57,939 | 1.91% |

| Christianity |

4,728 | 0.3% | 5,573 | 0.3% | 6,125 | 0.3% | 6,585 | 0.3% | 10,889 | 0.36% |

| Others | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 121[e] | 0% |

| Total Responses[d] | 1,575,943 | 100% | 1,857,519 | 100% | 2,041,534 | 96.05% | 2,196,766 | 57.52% | 3,038,087 | 56.1% |

| Total Population[d] | 1,575,943 | 100% | 1,857,519 | 100% | 2,125,496 | 100% | 3,819,027 | 100% | 5,415,666 | 100% |

Balochistan

| Religion | Population (1941)[54]: 18 |

% (1941) |

Population (2017)[4] |

% (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam |

785,181 | 91.53% | 12,255,528 | 99.28% |

| Hinduism |

54,394 | 6.34% | 49,378 | 0.4% |

| Sikhism |

12,044 | 1.4% | N/A | N/A |

| Christianity |

6,056 | 0.71% | 33,330 | 0.27% |

| Ahmadi | N/A | N/A | 2,469 | 0.02% |

| Others | 160 | 0.02% | 3,703 | 0.03% |

| Total Population | 857,835 | 100% | 12,344,408 | 100% |

Islam

Islam is the state religion of Pakistan, and about 95-98% of Pakistanis are Muslim.[55] Pakistan has the second largest number of Muslims in the world after Indonesia.[56] The majority are Sunni (estimated at 85-90%),[16][17] with an estimated 10-15% Shia.[16][17][18][57] A PEW survey in 2012 found that 6% of Pakistani Muslims were Shia.[58] There are a number of Islamic law schools called Madhab (schools of jurisprudence), which are called fiqh or 'Maktab-e-Fikr' in Urdu. Nearly all Pakistani Sunni Muslims belong to the Hanafi Islamic school of thought, while a small number belong to the Hanbali school. The majority of Pakistani Shia Muslims belong to the Twelver (Ithna Asharia) branch, with significant minority who adhere to Ismailism branch that is composed of Nizari (Aga Khanis), Mustaali, Dawoodi Bohra, Sulaymani, and others.[59] Sufis and above mentioned Sunni and Shia sects are considered to be Muslims according to the Constitution of Pakistan.

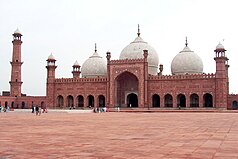

The mosque is an important religious as well as social institution in Pakistan.[60][61] Many rituals and ceremonies are celebrated according to Islamic calendar.

Sufi

Islam to some extent syncretized with pre-Islamic influences, resulting in a religion with some traditions distinct from those of the Arab world. Two Sufis whose shrines receive much national attention are Ali Hajweri in Lahore (ca. 11th century) and Shahbaz Qalander in Sehwan, Sindh (ca. 12th century).[citation needed] Sufism, a mystical Islamic tradition, promoted by Fariduddin Ganjshakar in Pakpatan, has a long history and a large popular following in Pakistan. Popular Sufi culture is centered on Thursday night gatherings at shrines and annual festivals which feature Sufi music and dance. Contemporary Islamic fundamentalists criticize its popular character, which in their view, does not accurately reflect the teachings and practice of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his companions. There have been terrorist attacks directed at Sufi shrines and festivals, 5 in 2010 that killed 64 people.[62][63]

Ahmadiyya

According to the last Census in Pakistan, Ahmadi made up 0.22% of the population; however, the Ahmadiyya community boycotted the census. Independent groups generally estimate the population to be somewhere between two and five million Ahmadis. In media reports, four million is the most commonly cited figure.[64]

In 1974, the government of Pakistan amended the Constitution of Pakistan to define a Muslim according to Qu'ran 33:40,[65] as a person who believes in finality of Muhammad under the Ordinance XX. According to Ordinance XX, Ahmadis cannot call themselves Muslim or "pose as Muslims" which is punishable by three years in prison.[66] Ahmadis believe in Muhammad as the final law-bearing prophet, but also believe Mirza Ghulam Ahmad to be a prophet, the prophecised Mehdi and second coming of Jesus. Consequently, Ahmadis were declared non-Muslims by a parliamentary tribunal and are subject to persecution under Pakistani blasphemy laws.

Hinduism

Hinduism is the second largest religion affiliation in Pakistan after Islam.[68] As of 2020, Pakistan has the fourth largest Hindu population in the world after India, Nepal and Bangladesh.[69] According to the 1998 Census, the Hindu population was found to be 2,111,271 (including 332,343 scheduled castes Hindus). While according to latest census of 2017, There are 4.4 million Hindus in Pakistan out of 207.68 million total population comprising 2.14% of the country's population of both General and Schedule caste.[44] Hindus are found in all provinces of Pakistan but are mostly concentrated in Sindh. About 93% of Hindus live in Sindh, 5% in Punjab and nearly 2% in Balochistan.[70] They speak a variety of languages such as Sindhi, Seraiki, Aer, Dhatki, Gera, Goaria, Gurgula, Jandavra, Kabutra, Koli, Loarki, Marwari, Sansi, Vaghri[71] and Gujarati.[72]

The Rig Veda, the oldest Hindu text, was believed to have been composed in the Punjab province of India along the Indus River around 1500 BCE[73] and spread from there across South and South East Asia slowly developing and evolving into the various forms of the faith we see today.[74]

Many ancient Hindu temples are located throughout Pakistan. A significant Hindu pilgrimage site known as Hinglaj Mata takes place in southern Balochistan, where over 250,000 people visit during spring as a pilgrimage.

Cases collected by Global Human Rights Defence show that underage Hindu (and Christian) girls are often targeted by Muslims for forced conversion to Islam.[14] According to the National Commission of Justice and Peace and the Pakistan Hindu Council (PHC) around 1,000 non-Muslim minority women are converted to Islam and then forcibly married off to their abductors or rapists.[75][15]

Christianity

Christians (Urdu: مسيحى، عیسائی) make up 1.6% of Pakistan's population.[76] The majority of the Pakistani Christian community consists of Punjabis who converted during the British colonial era and their descendants. Pakistani Christians mainly live in Punjab and in urban centres. There is also a Roman Catholic community in Karachi which was established by Goan and Tamil migrants when Karachi's infrastructure was being developed between the two World Wars. A few Protestant groups conduct missions in Pakistan. The present Christian population in Pakistan is ranged between 2-3 million as per as recent (2020–21) year estimation by various institution and NGOs of Pakistan.[3] There is a small myth that Christianity has been existent in Pakistan ever since a few decades after the crucifixion of Jesus. This myth became more popular after the finding of a structure looking like a giant cross in Northern Pakistan, but there is almost no evidence that this cross is related to Christianity.

There are a number of church-run schools in Pakistan that admit students of all religions, including Forman Christian College,[77][78] St. Patrick's Institute of Science & Technology and Saint Joseph's College for Women, Karachi.

Pakistan is number eight on Open Doors’ 2022 World Watch List, an annual ranking of the 50 countries where Christians face the most extreme persecution. [79] Cases collected by Global Human Rights Defence show that young underage Christian (and Hindu) girls are sometimes targeted by Muslims for forced conversion to Islam.[14][15] Christians also often face abuses of Pakistani blasphemy laws, notably in the case of Asia Bibi.

Other religions

Baháʼí

The Baháʼí Faith in Pakistan begins previous to its independence when it was still under British colonial rule. The roots of the religion in the region go back to the first days of the Bábí religion in 1844,[80] with Shaykh Sa'id Hindi who was from Multan.[81] During Bahá'u'lláh's lifetime, as founder of the religion, he encouraged some of his followers to move to the area that is present day Pakistan.[82]

The Baháʼís in Pakistan have the right to hold public meetings, establish academic centers, teach their faith, and elect their administrative councils.[83] Bahá'í sources claim their population to be around 30,000.[84] Shoba Das of Minority Rights Group International reported around 200 Baháʼís in Islamabad and between 2,000 and 3,000 Baháʼís in Pakistan, in 2013.[85] One more PhD thesis says that "It is an assumption that the Bahá’ís do not want to declare their exact population, which is supposed to be more or less 3,000 in total." Most of these Bahá’ís have their roots in Iran.[86]

Sikhism

In the 15th century, the reformist Sikh movement originated in Punjab region in undivided India where Sikhism's founder, as well as most of the faiths disciples, originated from. There are a number of Sikhs living throughout Pakistan today; estimates vary, but the number is thought to be on the order of 20,000. In recent years, their numbers have increased with many Sikhs migrating from neighboring Afghanistan who have joined their co-religionists in Pakistan.[87] The shrine of Guru Nanak Dev is located in Nankana Sahib near the city of Lahore where many Sikhs from all over the world make pilgrimage to this and other shrines.

Zoroastrianism

There are at least 4,000 Pakistani citizen practicing the Zoroastrian religion.[88] With the flight of Zoroastrians from Greater Iran into India, the Parsi communities were established. More recently, from the 15th century onwards, Zorastrians came to settle the coast of Sindh and have established thriving communities and commercial enterprises. These newer migrants were to be called Parsi. At the time of independence of Pakistan in 1947, Karachi and Lahore were home to a thriving Parsi business community. Karachi had the most prominent population of Parsis in Pakistan. After independence, many migrated abroad but a number remained. Parsis have entered Pakistani public life as social workers, business folk, journalists and diplomats. The most prominent Parsis of Pakistan today include Ardeshir Cowasjee, Byram Dinshawji Avari, Jamsheed Marker, as well as Minocher Bhandara. The founding father of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, married Ratti Bai who belonged to a Parsi family before her conversion to Islam.[89] It is also believed that parts of Balochistan and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa were Zoroastrian majority at one point. There is little evidence of this, but due to the same ethnic groups such as Pashtuns and the Baloch people likely practising Zoroastrianism in some parts of modern day Afghanistan and Iran before Islamic conquest, it is believed that Zoroastrianism may have been a majority religion in a few areas of Pakistan at one point during history.

Kalash

The Kalash people practise a form of ancient Hinduism[90] mixed with animism.[91] Adherents of the Kalash religion number around 3,000 and inhabit three remote valleys in Chitral; Bumboret, Rumbur and Birir. Their religion is probably related to Hinduism, but may be related to the Greek and Macedonian Pagan religion.[90] It is more similar to very early (Rigvedic) Hinduism, than later forms of Hinduism.[92]

Jainism

Jainism existed in Sindh, Punjab, Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, before the partition in 1947, and even for several years after the partition. There is no evidence of any Jains living in Pakistan today, although it is claimed that a few still live in Sindh and Punjab provinces. They are number of disused Jain Temples found in different parts of Pakistan. Gulu Lalvani, a famous Jain, was originally from Pakistan but he, like other Jains, emigrated from Pakistan. Baba Dharam Das Tomb is also found in Pakistan. The Jain temple at Gori in Tharparkar was a major Jain pilgrimage center. The Jain Mandir Chowk at Lahore was the site of a Digambar Jain Temple. The memorial of Jain seer Vijayanandsuri at Gujranwala is now a police station.[93]

Buddhism

Buddhism has an ancient history in Pakistan; currently there is a small community of at least 1500 Pakistani Buddhist in the country.[88] The country is dotted with numerous ancient and disused Buddhist stupas along the entire breadth of the Indus River that courses through the heart of the country. Many Buddhist empires and city states existed, notably in Gandhara but also elsewhere in Taxila, Punjab and Sindh.[94]

The number of Buddhist voters was 1,884 in 2017 and are mostly concentrated in Sindh and Punjab.[95]

Judaism

Various estimates suggest that there were about 1,500 Jews living in Pakistan at the time of its independence on 14 August 1947, with the majority living in Karachi and a few living in Peshawar. However, almost all emigrated to Israel after 1948. There are a few disused synagogues in both cities; while one Karachi synagogue was torn down for the construction of a shopping mall. The one in Peshawar still exists, although the building is not being used for any religious purpose. There is a small Jewish community of Pakistani origin settled in Ramla, Israel.

One Pakistani, Faisal Khalid (a.k.a. Fishel Benkhald) of Karachi claims to be Pakistan's only Jew.[96][97] He claimed that his mother is Jewish (making him Jewish by Jewish custom) but, his father is a Muslim. Pakistani authorities have issued him a passport which stated Judaism as his religion and have allowed him to travel to Israel.[98][99][100]

Irreligion

Irreligion is present among a minority of mainly young people in Pakistan. There are people who do not profess any faith (such as atheists and agnostics) in Pakistan, but their numbers are not known.[101] They are particularly in the affluent areas of the larger cities. Some were born in secular families while others in religious ones. According to the 1998 census, people who did not state their religion accounted for 0.5% of the population, but social pressure against claiming no religion was strong.[87] A 2012 study by Gallup Pakistan found that people not affiliated to any religion account for 1% of the population.[102] Many atheists in Pakistan have been lynched and imprisoned over unsubstantiated allegations of blasphemy. When the state initiated a full-fledged crackdown on atheism since 2017, it has become worse with secular bloggers being kidnapped and the government running advertisements urging people to identify blasphemers among them and the highest judges declaring such people to be terrorists.[103]

See also

- Blasphemy law in Pakistan

- Demographics of Pakistan

- Religious Minorities in Pakistan

- Pakistan National Commission for Minorities

- Shamanism in Pakistan

- Major religious groups

- List of religious populations

References

- ^ a b "SALIENT FEATURES OF FINAL RESULTS CENSUS-2017" (PDF). Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Religions in Pakistan | PEW-GRF". www.globalreligiousfutures.org.

- ^ a b c "Refworld | World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Pakistan : Christians".

- ^ a b c d e Riazul Haq and Shahbaz Rana (27 May 2018). "Headcount finalised sans third-party audit". Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "Population By Religion" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Government of Pakistan: 1.

"Population Distribution by Religion, 1998 Census" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 12 July 2020. - ^ West, Barbara A. (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 357. ISBN 9781438119137.

- ^ "Part I: "Introductory"". www.pakistani.org.

- ^ a b c "Pakistan, Islam in". Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

Approximately 97 percent of Pakistanis are Muslims. The majority are Sunnis following the Hanafi school of Islamic law. Between 10–15 percent are Shiis, mostly Twelvers.

- ^ "Religions: Muslim 97% (Sunni 75%, Shia 20%), other". Pakistan (includes Christian and Hindu) 4%. The World Factbook. CIA. 2010. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ 2014 World Population Data Sheet (PDF). Population Reference Bureau (Report). August 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ Information on other countries: http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR_20072008_EN_Complete.pdf [page needed]

- ^ "Country Profile: Pakistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies on Pakistan. Library of Congress. February 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

Religion: About 97 percent of Pakistanis are Muslim, 64 percent of whom are Sunni and 33 percent Shia; remaining 3 percent of population divided equally among Christian, Hindu, and other religions

- ^ "Population: 174,578,558 (July 2010 est.)". Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook on Pakistan. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ a b c GHRD Human Rights Report 2019 (PDF) (Report). Global Human Rights Defence. 7 March 2019. Archived from the original on 19 September 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c "Pakistan: Islamists angry at new law against forced conversions". FRANCE 24 English. 3 January 2017. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ a b c "Country Profile: Pakistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies on Pakistan. Library of Congress. February 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

About 97 percent of Pakistanis are Muslim, 85-90 percent of whom are Sunni and 10-15 percent Shia

- ^ a b c "Religions: Muslim (official) 96.4% (Sunni 85-90%, Shia 10-15%), other (includes Christian and Hindu) 3.6% (2020 est.)". The World Factbook. CIA. 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ a b "The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity". Pew Research Center. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

On the other hand, in Pakistan, where 6% of the survey respondents identify as Shia, Sunni attitudes are more mixed: 50% say Shias are Muslims, while 41% say they are not.

- ^ "Pakistan must confront Wahhabism | Adrian Pabst". TheGuardian.com. 20 August 2009.

- ^ Stubbs, John H.; Thomson, Robert G. (10 November 2016). Architectural Conservation in Asia: National Experiences and Practice. Taylor & Francis. p. 427. ISBN 978-1-317-40619-8.

Perhaps best known as home to Asia's earliest cities, the Harappan sites of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, Pakistan's rich history includes contributions from prominent Buddhist, Hindu, Hellenistic, Jain and Zoroastrian civilizations, as well as those connected to its Islamic heritage.

- ^ Malik, Iftikhar Haider (2006). Culture and Customs of Pakistan. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-313-33126-8.

- ^ "The Constitution of Pakistan, Part I: Introductory". Pakistani.org. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ "The Constitution of Pakistan, Part II: Chapter 1: Fundamental Rights". Pakistani.org. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ Iqbal, Khurshid (2009). The Right to Development in International Law: The Case of Pakistan. Routledge. p. 189. ISBN 9781134019991.

- ^ "The Constitution of Pakistan, Part III: Chapter 1: The President". Pakistani.org. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ "The Constitution of Pakistan, Notes for Part III, Chapter 3". Archived from the original on 10 November 2009.

- ^ "The Constitution of Pakistan, Part VII: Chapter 3A: Federal Shariat Court". Pakistani.org. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ Shah, Sabir. "Justice Bhagwandas and some other non-Muslim Pak luminaries". The News International. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Pakistan's parliament blocks bill allowing non-Muslims to become country's PM, President". City: Delhi. The Hindu. TNN. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ "Can Islamic Republic of Pakistan be a secular state?". The Hindu. PTI. 5 May 2015. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Jinnah's Pakistan: Islamic state or secular democracy?". The Nation. 25 December 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Nasir, Abbas (15 August 2017). "Opinion | How Pakistan Abandoned Jinnah's Ideals (Published 2017)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "Fundamental Rights in Pakistan – PHRO".

- ^ "Article 20 freedom to profess religion and to manage religious institutions – the Constitution of Pakistan, 1973 Developed by Zain Sheikh | Fake Rolex Replica Watches, Advocates & Corporate Consultants".

- ^ Pakistan Laws on Human Rights - Humanitarian Library |

- ^ "Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan 1973 - Part II". www.commonlii.org.

- ^ "Article: 25 Equality of citizens – the Constitution of Pakistan, 1973 Developed by Zain Sheikh | Fake Rolex Replica Watches, Advocates & Corporate Consultants".

- ^ "Truth, half-truth and statistics". The Times of India. 20 July 2017.

- ^ Service, Tribune News. "'Forced' conversions resulting in mass exodus of Hindus from Pakistan". Tribuneindia News Service.

- ^ "Sikhs in Pakistan on verge of becoming extinct minority group". www.daijiworld.com.

- ^ "Census of Pakistan" (PDF). 1951.

- ^ D'Costa, Bina (2011), Nationbuilding, Gender and War Crimes in South Asia, Routledge, pp. 100–, ISBN 978-0-415-56566-0

- ^ Talbot, Ian; Singh, Gurharpal (23 July 2009). The Partition of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-521-85661-4.

- ^ a b "Headcount finalised sans third-party audit". The Express Tribune. 26 May 2018.

- ^ "Pakistan Population (2021) - Worldometer".

- ^ Iftikhar A. Khan (28 May 2018). "Number of non-Muslim voters in Pakistan shows rise of over 30pc". Dawn. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ "Losing your religion?: 'NADRA should not be deciding people's faith'". The Express Tribune. 12 April 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Pakistan's population is 207.68m, shows 2017 census result". 19 May 2021.

- ^ "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1941 VOLUME VI PUNJAB PROVINCE". Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1941 VOLUME XII SIND" (PDF). Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Tunio, Hafeez (31 May 2020). "Shikarpur's Sikhs serve humanity beyond religion". The Express Tribune. Pakistan. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1911 VOLUME XII NORTH-WEST FRONTIER PROVINCE" (PDF). Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1941 VOLUME X NORTH-WEST FRONTIER PROVINCE". Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1941 VOLUME XIV BALUCHISTAN".

- ^ "Pakistan, Islam in". Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

Approximately 97 percent of Pakistanis are Muslim. The majority are Sunnis following the Hanafi school of Islamic law. Between 10 to 15 percent are Shias, mostly Twelvers.

- ^ Singh, Dr. Y P (2016). Islam in India and Pakistan – A Religious History. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9789385505638.

Pakistan has the second largest Muslim population in the world after Indonesia.

- ^ "Country Profile: Pakistan" (PDF). Library of Congress. 2005. pp. 2, 3, 6, 8. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ "The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity". Pew Research Center. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

On the other hand, in Pakistan, where 6% of the survey respondents identify as Shia, Sunni attitudes are more mixed: 50% say Shias are Muslims, while 41% say they are not.

- ^ "Heart of darkness: Shia resistance and revival in Pakistan". Herald. 29 October 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Malik, Jamal. Islam in South Asia: A Short History. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2008.

- ^ Mughal, Muhammad Aurang Zeb (2015). "An anthropological perspective on the mosque in Pakistan" (PDF). Asian Anthropology. 14 (2): 166–181. doi:10.1080/1683478X.2015.1055543. S2CID 54051524.

- ^ Produced by Charlotte Buchen. "Sufism Under Attack in Pakistan" (video). The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ Huma Imtiaz; Charlotte Buchen (6 January 2011). "The Islam That Hard-Liners Hate" (blog). The New York Times. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ The 1998 Pakistani census states that there are 291,000 (0.22%) Ahmadis in Pakistan. However, the Ahmadiyya Muslim community has boycotted the census since 1974 which renders official Pakistani figures to be inaccurate. Independent groups have estimated the Pakistani Ahmadiyya population to be somewhere between 2 million and 5 million Ahmadis. However, the 4 million figure is the most quoted figure and is approximately 2.2% of the country. See:

- over 2 million: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (4 December 2008). "Pakistan: The situation of Ahmadis, including legal status and political, education and employment rights; societal attitudes toward Ahmadis (2006 - Nov. 2008)". Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- 3 million: International Federation for Human Rights: International Fact-Finding Mission. Freedoms of Expression, of Association and of Assembly in Pakistan. Ausgabe 408/2, Januar 2005, S. 61 (PDF)

- 3–4 million: Commission on International Religious Freedom: Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. 2005, S. 130

- 4.910.000: James Minahan: Encyclopedia of the stateless nations. Ethnic and national groups around the world. Greenwood Press . Westport 2002, page 52

- "Pakistan: Situation of members of the Lahori Ahmadiyya Movement in Pakistan". Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Surah Al-Ahzab - 40".

- ^ "ORDINANCE NO. XX OF 1984". The Persecution. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ Xafar, Ali (20 April 2016). "Mata Hinglaj Yatra: To Hingol, a pilgrimage to reincarnation". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "Population Distribution by Religion, 1998 Census" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ "Countries with the Largest Hindu Populations". 15 January 2019.

- ^ "Population by religion". Archived from the original on 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Pakistan". Ethnologue. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Rehman, Zia Ur (18 August 2015). "With a handful of subbers, two newspapers barely keeping Gujarati alive in Karachi". The News International. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

In Pakistan, the majority of Gujarati-speaking communities are in Karachi including Dawoodi Bohras, Ismaili Khojas, Memons, Kathiawaris, Katchhis, Parsis (Zoroastrians) and Hindus, said Gul Hasan Kalmati, a researcher who authored "Karachi, Sindh Jee Marvi", a book discussing the city and its indigenous communities. Although there are no official statistics available, community leaders claim that there are three million Gujarati-speakers in Karachi – roughly around 15 percent of the city's entire population.

- ^ "Rigveda | Hindu literature". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Bronkhorst, Johannes (2016). How the Brahmins Won: From Alexander to the Guptas. Brill. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-90-04-31519-8.

- ^ "Forced conversions of Pakistani Hindu girls". 19 September 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ "Country Profile: Pakistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies on Pakistan. Library of Congress. February 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ Najam, Adil (30 March 2008). "Forman Christian (F.C.) College's Political Clout". Pakistaniat. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Bangash, Yaqoob Khan. "FC College: an amazing transformation". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Pakistan is number 8 on the World Watch List".

- ^ "The Bahá'í Faith -Brief History". Official Website of the National Spiritual Assembly of India. National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of India. 2003. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "History of the Bahá'í Faith in Pakistan". Official Webpage of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Pakistan. National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Pakistan. 2008. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Momen, Moojan; Smith, Peter. "Bahá'í History". Draft A Short Encyclopedia of the Baha'i Faith. Bahá'í Library Online. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Wardany, Youssef (2009). "The Right of Belief in Egypt: Case study of Baha'i minority". Al Waref Institute. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Wagner, Ralph D. "Pakistan". Synopsis of References to the Bahá'í Faith, in the US State Department's Reports on Human Rights 1991-2000. Bahá'í Academics Resource Library. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Das, Shobha (10 April 2013). "A Pakistani Baha'i's story". Minority Rights Group. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Fareed, Abdul (2015). RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL LIFE OF RELIGIOUS MINORITIES (Thesis thesis). INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD, PAKISTAN.

- ^ a b "Pakistan - International Religious Freedom Report 2008". United States Department of State. 19 September 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ a b Ghauri, Irfan (2 September 2012). "Over 35,000 Buddhists, Baha'is call Pakistan home". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Quaid i Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah: Early days". Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original on 24 October 2008.

- ^ a b West, Barbara A. (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 357. ISBN 9781438119137.

The Kalasha are a unique people living in just three valleys near Chitral, Pakistan, the capital of North-West Frontier Province, which borders Afghanistan. Unlike their neighbors in the Hindu Kush Mountains on both the Afghani and Pakistani sides of the border the Kalasha have not converted to Islam. During the mid-20th century a few Kalasha villages in Pakistan were forcibly converted to this dominant religion, but the people fought the conversion and once official pressure was removed the vast majority continued to practice their own religion. Their religion is a form of Hinduism that recognizes many gods and spirits and has been related to the religion of the Ancient Greeks, who mythology says are the ancestors of the contemporary Kalash… However, it is much more likely, given their Indo-Aryan language, that the religion of the Kalasha is much more closely aligned to the Hinduism of their Indian neighbors that to the religion of Alexander the Great and his armies.

- ^ Sean Sheehan (1 October 1993). Pakistan. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-1-85435-583-6.

The Kalash people are small in number, hardly exceeding 3,000, but they ... and as well as having their own language and costume, they practice animism (the worship of spirits in nature)...

- ^ Witzel, Michael (2004), "Kalash Religion (extract from 'The Ṛgvedic Religious System and its Central Asian and Hindukush Antecedents')" (PDF), in A. Griffiths; J. E. M. Houben (eds.), The Vedas: Texts, Language and Ritual, Groningen: Forsten, pp. 581–636

- ^ "Pakistan Jain Temple". Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Arthur Anthony Macdonell (31 December 1997). A History of Sanskrit Literature. ISBN 9788120800953.

- ^ Ahmad, Imtiaz (28 May 2018). "Pakistan elections: Non-Muslim voters up by 30%, Hindus biggest minority". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "Brothers of Pakistani man claiming to be Jewish call him insane". Israel National News. 9 April 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Karachi, Pakistan - Brothers Of Pakistani Man Claiming Jewish Roots Call Him 'Insane'". VosIzNeias. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Simon Caldwell (26 November 2015). "Pakistan's last Jew in battle to win 'empathy'". Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "'Last Jew in Pakistan' beaten by mob, arrested". Express Tribune. 6 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Brothers of Pakistani man claiming Jewish roots call him 'insane'". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 9 April 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Being Pakistani and atheist a dangerous combo, but some ready to brave it". Pakistan Today. 17 September 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Gallup Pakistan - Pakistan's Foremost Research Lab" (PDF).

- ^ Shahid, Kunwar Khuldune (11 June 2020). "Pakistan's forced conversions shame Imran Khan". The Spectator. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ 1941 figure reached by combining total population of all districts (Lahore, Sialkot, Gujranwala, Sheikhupura, Gujrat, Shahpur, Jhelum, Rawalpindi, Attock, Mianwali, Montgomery, Lyallpur, Jhang, Multan, Muzaffargargh, Dera Ghazi Khan), one tehsil (Shakargarh -- then part of Gurdaspur District), and one princely state (Bahawalpur) in British Punjab as per 1941 census data. These districts, tehsil, and princely state would ultimately make up the subdivision of West Punjab Province, Pakistan (contemporarily known as Punjab Province, Pakistan), following the partition of India in 1947. The districts and princely state in 1941 that made up Punjab Province, Pakistan have since undergone various bifurcations at several points throughout the post-independence era, due to the rapid population growth witnessed across the province.

- ^ 1941 census: Including Ad-Dharmis

- ^ 1941 census: Including Jainism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Tribals, others, or not stated

2017 census: Also includes Sikhs, Baháʼís, Ahmadyyas, others, and not stated - ^ a b c Pre-partition populations for religious data is for North-West Frontier Province only and excludes the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (both administrative divisions later merged to form Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2018), as religious data was not collected in the latter region at the time.

- ^ Included 71 Jews, 25 Buddhists, 24 Parsis (Zoroastrians), and 1 Jain.

External links

- Ministry of Religious Affairs – (Government of Pakistan) Official website