Muammar Gaddafi: Difference between revisions

←Replaced content with 'Muammar Gaddafi is a DEVIL who thinks that he is the most powerful king in the world ! but he is not ! he is just an Idiot who has to retard like before 10 ...' Tag: blanking |

m Reverted edits by 85.5.137.223 (talk) to last revision by Mezigue (HG) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Redirect|Gaddafi}} |

|||

Muammar Gaddafi is a DEVIL who thinks that he is the most powerful king in the world ! |

|||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=October 2012}} |

|||

{{Infobox officeholder |

|||

|name = Muammar Gaddafi |

|||

|image = Muammar al-Gaddafi at the AU summit.jpg |

|||

|caption = Gaddafi in 2009 |

|||

|office = [[Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution|Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution of Libya]] |

|||

|president = {{List collapsed|title=''See list''|1={{plain list| |

|||

* [[Abdul Ati al-Obeidi]] |

|||

* [[Muhammad az-Zaruq Rajab]] |

|||

* [[Mifta al-Usta Umar]] |

|||

* [[Abdul Razzaq as-Sawsa]] |

|||

* [[Muhammad az-Zanati]] |

|||

* [[Miftah Muhammed K'eba]] |

|||

* [[Imbarek Shamekh]] |

|||

* [[Mohamed Abu Al-Quasim al-Zwai]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|primeminister = {{List collapsed|title=''See list''|1={{plain list| |

|||

* [[Jadallah Azzuz at-Talhi]] |

|||

* [[Muhammad az-Zaruq Rajab]] |

|||

* [[Jadallah Azzuz at-Talhi]] |

|||

* [[Umar Mustafa al-Muntasir]] |

|||

* [[Abuzed Omar Dorda]] |

|||

* [[Abdul Majid al-Qa′ud]] |

|||

* [[Muhammad Ahmad al-Mangoush]] |

|||

* [[Imbarek Shamekh]] |

|||

* [[Shukri Ghanem]] |

|||

* [[Baghdadi Mahmudi]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|term_start = 1 September 1969 |

|||

|term_end = 20 October 2011{{#Tag:ref|For purposes of this article, 23 August 2011 is considered to be the date that Gaddafi left office. Other dates might have been chosen. |

|||

*On 15 July 2011, at a meeting in Istanbul, more than 30 governments, including the United States, withdrew recognition from Gaddafi's government and recognised the National Transitional Council (NTC) as the legitimate government of Libya.<ref name="INDtncofficialgov">{{cite news | url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/west-prepares-to-hand-rebels-gaddafis-billions-2314576.html | title=West prepares to hand rebels Gaddafi's billions |work=The Independent|location=London | date=16 July 2011| accessdate=16 July 2011 | first=Justin | last=Vela}}</ref> |

|||

*On 23 August 2011, during the [[Battle of Tripoli (2011)|Battle of Tripoli]], Gaddafi lost effective political and military control of Tripoli after his compound was captured by rebel forces.<ref name=liveblog23811>Staff (23 August 2011). [http://blogs.aljazeera.net/liveblog/libya-aug-23-2011-1819 "''Libya Live Blog'': Tuesday, August 23, 2011 – 16:19"]. [[Al Jazeera]]. Retrieved 23 August 2011.</ref> |

|||

*On 25 August 2011, the [[Arab League]] proclaimed the anti-Gaddafi National Transitional Council to be "the legitimate representative of the Libyan state".<ref name=taipeitimmes20110826 /> |

|||

*On 20 October 2011, Gaddafi was captured and killed near his hometown of Sirte.<ref name=bbc20111021>{{cite news|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-15390980 |title=Muammar Gaddafi: How he died |publisher=BBC|accessdate=21 October 2011}}</ref> |

|||

* In a ceremony on 23 October 2011, officials of the interim National Transitional Council declared, "We declare to the whole world that we have liberated our beloved country, with its cities, villages, hill-tops, mountains, deserts and skies."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://uk.reuters.com/article/2011/10/23/libya-declaration-liberation-idUKL5E7LN0P620111023|title=UPDATE 4-Libya declares nation liberated after Gaddafi death|date=23 October 2011|work=Reuters|first=Yasmine|last=Saleh}}</ref>|group=nb}} |

|||

|predecessor = ''Position established'' |

|||

|successor = ''Position abolished'' |

|||

|office1 = [[List of heads of state of Libya|Secretary General of the General People's Congress of Libya]] |

|||

|primeminister1 = [[Abdul Ati al-Obeidi]] |

|||

|term_start1 = 2 March 1977 |

|||

|term_end1 = 2 March 1979 |

|||

|predecessor1 = Himself <small>(Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council)</small> |

|||

|successor1 = [[Abdul Ati al-Obeidi]] |

|||

|office2 = [[List of heads of government of Libya|Prime Minister of Libya]] |

|||

|term_start2 = 16 January 1970 |

|||

|term_end2 = 16 July 1972 |

|||

|predecessor2 = [[Mahmud Sulayman al-Maghribi]] |

|||

|successor2 = [[Abdessalam Jalloud]] |

|||

|office3 = [[List of heads of state of Libya|Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council of Libya]] |

|||

|primeminister3 = {{plain list| |

|||

* [[Mahmud Sulayman al-Maghribi]] |

|||

* [[Abdessalam Jalloud]] |

|||

* [[Abdul Ati al-Obeidi]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|term_start3 = 1 September 1969 |

|||

|term_end3 = 2 March 1977 |

|||

|predecessor3 = [[Idris of Libya|Idris]] <small>(King)</small> |

|||

|successor3 = Himself <small>(Secretary General of the General People's Congress)</small> |

|||

|office4 = [[Chairperson of the African Union]] |

|||

|term_start4 = 2 February 2009 |

|||

|term_end4 = 31 January 2010 |

|||

|predecessor4 = [[Jakaya Kikwete]] |

|||

|successor4 = [[Bingu wa Mutharika]] |

|||

|birth_date = <!--DO NOT ADD 7, sources contradict one another regarding this, see talk page-->7 June 1942<ref group=nb name="dob">Some sources, such as a [http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-12537524 BBC Obituary Muammar al-Gaddafi], give the date as 7 June. Other sources say 7 June 1942; others say "Spring of 1942" (''Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East, 2004'') or "September 1942" (''Encyclopedia of World Biography, 1998'')</ref> |

|||

|birth_place = [[Qasr Abu Hadi]], [[Italian Libya|Libya]] |

|||

|death_date = {{death date and age|2011|10|20|1942|6|7|df=yes}} |

|||

|death_place = [[Sirte]], Libya |

|||

|resting_place = Undisclosed |

|||

|party = [[Arab Socialist Union (Libya)|Arab Socialist Union]] <small>(1971–1977)</small> |

|||

[[Independent (politician)|Independent]] <small>(1977–2011)</small> |

|||

|spouse = {{plain list| |

|||

* Fatiha al-Nuri <small>(1969–1970)</small> |

|||

* [[Safia Farkash|Safia el-Brasai]] <small>(1970–2011)</small> |

|||

}} |

|||

|children = {{List collapsed|title=''Sons''|1={{plain list| |

|||

* [[Muhammad Gaddafi|Muhammad]] <small>(born 1970)</small> |

|||

* [[Saif al-Islam Gaddafi|Saif al-Islam]] <small>(born 1972)</small> |

|||

* [[Al-Saadi Gaddafi|Al-Saadi]] <small>(born 1973)</small> |

|||

* [[Mutassim Gaddafi|Mutassim]] <small>(1974–2011)</small> |

|||

* [[Hannibal Muammar Gaddafi|Hannibal]] <small>(born 1975)</small> |

|||

* [[Saif al-Arab Gaddafi|Saif al-Arab]] <small>(1982–2011)</small> |

|||

* [[Khamis Gaddafi|Khamis]] <small>(1983–2012)</small> |

|||

* Milad <small>(adopted)</small> |

|||

}} |

|||

}}{{List collapsed|title=''Daughters''|1={{plain list| |

|||

* [[Ayesha Gaddafi|Ayesha]] <small>(born 1976)</small> |

|||

* Hanna <small>(adopted)</small> |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|alma_mater = [[Benghazi Military University Academy]] |

|||

|religion = [[Sunni Islam]] |

|||

|signature = Muammar al-Gaddafi Signature.svg |

|||

|allegiance = [[File:Flag of Libya (1977-2011).svg|30px]] |

|||

{{plain list| |

|||

* {{flagicon|Libya|1951}} [[Kingdom of Libya]]<div style="font-size:85%;">(1961–1969)</div> |

|||

* {{flagicon|Libya|1972}} [[Libyan Arab Republic]]<div style="font-size:85%;">(1969–1977)</div> |

|||

* {{flagicon|Libya|1977}} [[Libyan Arab Jamahiriya]]<div style="font-size:85%;">(1977–2011)</div> |

|||

}} |

|||

|branch = [[Libyan Army (1951–2011)|Libyan Army]] |

|||

|serviceyears = 1961–2011 |

|||

|rank = [[Colonel]] |

|||

|commands = [[Libyan Army (1951–2011)|Libyan Armed Forces]] |

|||

|battles = {{plain list| |

|||

* [[Libyan coup d'etat (1969)]] |

|||

* [[Libyan–Egyptian War]] |

|||

* [[Chadian–Libyan conflict]] |

|||

* [[Uganda–Tanzania war]] |

|||

* [[Bombing of Libya (1986)]] |

|||

* [[Libyan civil war]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|awards = {{plain list| |

|||

* [[Order of the Yugoslav Star]] |

|||

* [[South African civil honours#Republic of South Africa|Order of Good Hope]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi'''<ref name="iccwarrant">{{cite web|title=The Prosecutor v. Muammar Mohammed Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi and Abdullah al-Senussi|url=http://www.icc-cpi.int/Menus/ICC/Situations+and+Cases/Situations/ICC0111/Related+Cases/ICC01110111/Court+Records/ |work=ICC-01/11-01/11|publisher=[[International Criminal Court]]|accessdate=3 September 2011|date=4 July 2011}}</ref> ({{lang-ar|معمر محمد أبو منيار القذافي}} {{IPAc-en|icon|ˈ|m|oʊ|.|ə|m|ɑr|_|ɡ|ə|ˈ|d|ɑː|f|i}} {{Audio|Ar-Muammar al-Qaddafi.ogg|audio}}) (''c''.1942–43{{spaced ndash}}20 October 2011), commonly known as '''Colonel Gaddafi''',{{#tag:ref|Due to the lack of standardization of [[Romanization of Arabic|transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic]], Gaddafi's name has been [[romanization|romanized]] in various different ways. A 1986 column by ''[[The Straight Dope]]'' lists 32 spellings known from the U.S. [[Library of Congress]],<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.straightdope.com/classics/a2_264b.html |title=How are you supposed to spell Muammar Gaddafi/Khadafy/Qadhafi? |publisher=The Straight Dope |year=1986 |accessdate=5 March 2006}}</ref> while [[American Broadcasting Company|ABC]] and MSNBC identified 112 possible spellings.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://blogs.abcnews.com/theworldnewser/2009/09/how-many-different-ways-can-you-spell-gaddafi.html |title=How many different ways can you spell 'Gaddafi' |publisher=ABC News |date=September 2009 |accessdate=22 February 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite video|person=Chris Matthews|title=Hardball With Chris Matthews|url=http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/3036697/#44994620|date=21 October 2011|publisher=MSNBC|accessdate=22 October 2011}}</ref> A 2007 interview with Gaddafi's son [[Saif al-Islam Gaddafi]] confirms that he uses the spelling "Qadhafi",<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thedailybeast.com/videos/2011/03/01/saif-gaddafi-on-how-to-spell-his-last-name.html |title=Saif Gaddafi on How to Spell His Last Name |publisher=The Daily Beast |date=1 March 2011 |accessdate=1 September 2011}}</ref> and Muammar's official passport uses the spelling "Al-Gathafi".<ref>{{cite news|newspaper=The Atlantic|title=Rebel Discovers Qaddafi Passport, Real Spelling of Leader's Name|url=http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/08/rebel-discovers-qaddafi-passport-real-spelling-of-leaders-name/244077/}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A4g_8zBdwzk |title=Mohamed Al-Gaddafi's Passport August 24, 2011 |publisher=YouTube |date=24 August 2011 |accessdate=1 September 2011}}</ref>|group=nb}} was a [[Libyan people|Libyan]] revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He served as the ruler of the [[Libyan Arab Republic]] from 1969 to 1977 and then the "Brother Leader" of the [[Libyan Arab Jamahiriya]] from 1977 to 2011, during which industry and business was nationalized. Politically an [[Arab nationalism|Arab nationalist]], he formulated his own ideology, [[Third International Theory]], later embracing [[Pan-Africanism]] and serving as [[Chairperson of the African Union|Chairperson]] of the [[African Union]] from 2009 to 2010. |

|||

<!--Early life and the republic:--> |

|||

but he is not ! he is just an Idiot who has to retard like before 10 years now ! |

|||

The son of an impoverished [[Bedouin]] goatherd, Gaddafi became involved in Arab nationalist politics while at school in [[Sabha, Libya|Sabha]], subsequently enrolling in the [[Benghazi Military University Academy|Royal Military Academy, Benghazi]]. Founding a revolutionary group within the ranks of the Libyan military, in 1969 he seized power from [[Idris of Libya|King Idris]] in a [[Nonviolent revolution|bloodless]] [[Libyan coup d'etat (1969)|coup]]. Becoming leader of the governing [[Libyan Revolutionary Command Council|Revolutionary Command Council]] (RCC), he dissolved the monarchy and proclaimed the Libyan Arab Republic. Ruling by decree, he implemented measures to remove foreign [[imperialism|imperialist]] influence from Libya, and strengthened ties to other Arab nationalist governments. Intent on pushing Libya toward [[socialism]], he nationalized the country's oil industry and used the increased revenues to bolster the military, implement social programs and fund revolutionary groups across the world. In 1973 he announced the start of a "Popular Revolution" with the formation of [[General People's Committee]]s (GPCs), a system of [[direct democracy]], but retained personal control over major decisions. He outlined his Third International Theory that year, publishing these ideas in ''[[The Green Book (Libya)|The Green Book]]''. |

|||

<!--Jamahiriya and downfall:--> |

|||

he killed all the Libyans in Libya . |

|||

In 1977, he dissolved the Republic and created the ''[[Wikt:Jamahiriya|Jamahiriya]]'', officially adopting a symbolic role within the country's governance structure. He retained power as the leader of the Revolutionary Committees; founded to accompany the GPCs, they implemented revolutionary justice and suppressed opponents. Overseeing unsuccessful border conflicts with Egypt and Chad, Gaddafi's support for foreign militants led to Libya being labelled an "international pariah", with a particularly hostile relationship developing with the United States and United Kingdom. From 1999, Gaddafi encouraged the privatization of the economy, moving to integrate with the rest of Africa and seeking better relations with the West. In 2011, an anti-Gaddafist uprising led by the [[National Transitional Council]] (NTC) broke out, resulting in the [[Libyan civil war]]. [[NATO]] [[2011 military intervention in Libya|intervened militarily]] on the side of the NTC, resulting in the government's downfall. Retreating to [[Sirte]], Gaddafi was captured and killed by NTC fighters. |

|||

<!--Legacy and assessment:--> |

|||

he just made Libya the worst country you can imagine ! . |

|||

Gaddafi is a controversial and highly divisive world figure, being lauded as a champion of anti-imperialism and both Arab and African nationalism, but critics have accused him of being a dictator and autocrat whose authoritarian administration oversaw [[Human rights in Libya|multiple human rights abuses]] and supported international [[terrorism]]. |

|||

{{TOC limit|3}} |

|||

------------- |

|||

==Early life== |

|||

And even the worst thing he killed me ! After I wrote this ! |

|||

===Childhood: 1942/43–1950=== |

|||

------------- |

|||

Muammar Gaddafi was born in his family tent near to [[Qasr Abu Hadi]], a rural area outside the town of [[Sirte]] in the deserts of western Libya.<ref name="Bruce St John 135">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 135.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 9">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 9.</ref> Ethnically an [[Arab]], he came from a small, relatively unimportant tribal group called the [[Qadhadhfa]].<ref name="Kawczynski 9"/> His father, Mohammad Abdul Salam bin Hamed bin Mohammad, was known as Abu Meniar, while his mother was named Aisha; they lived off of Abu Meniar's subsistence as a goat and camel herder.<ref name="Kawczynski 9"/> Nomadic [[Bedouin]], they were illiterate and kept no birth records; as such, Gaddafi's date of birth is not known with any certainty, and sources have positioned his birth in either 1942 or in the spring of 1943.<ref name="Bruce St John 135"/><ref name="Kawczynski 9"/> His parents' only surviving son, he had three older sisters.<ref name="Bruce St John 135"/><ref name="Kawczynski 9"/> Raised in Bedouin culture, Gaddafi's upbringing influenced his personal tastes for the rest of the life; he repeatedly expressed his preference for the desert to the city, retreating there to meditate.<ref name="Bruce St John 135"/><ref name="Kawczynski 9"/> |

|||

At the time of his birth, Libya was [[Italian Libya|occupied by Italy]], witnessing the conflict between Italian and British troops as a part of the [[North African Campaign]] of [[World War II]]; as a result, Gaddafi was aware of the involvement of European colonialists in his country from childhood.<ref name="Bruce St John 135"/> According to later claims, Gaddafi's paternal grandfather, Abdessalam Bouminyar, had died fighting the Italian Army in [[Khoms, Libya|Khoms]] during the first battle of the [[Italo-Turkish War|Italian invasion of 1911]].<ref name="Kawczynski 4">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 4.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.newsy.com/videos/amid-unrest-gaddafi-vows-death-before-resignation/ |title=Global Video News: Gaddafi Regime Still Twitching in Libya |publisher=Newsy.com |date=22 February 2011 |accessdate=1 September 2011}}</ref> At World War II's end in 1945, British and French forces had taken control of Libya, and although intending on dividing the nation between themselves, the [[General Assembly of the United Nations]] declared that the country be granted political independence. In 1951, the UN created the [[United Kingdom of Libya]], a federal state under the leadership of a pro-western monarch, [[Idris of Libya|Idris]], who banned political parties and established an [[absolute monarchy]].<ref name="Bruce St John 108">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 108.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 7-9,14">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 7–9, 14.</ref> |

|||

p.s ( he didn't Really killed me ! , it's he's supporters who attacked me ) |

|||

===Education and political activism: 1950–1963=== |

|||

-------------- |

|||

[[File:Nasser.jpg|thumb|upright|left|Egyptian President Nasser became Gaddafi's ideological hero early in life.]] |

|||

by :- A Libyan rebal :) |

|||

Gaddafi's earliest education was provided by a local tribal teacher, comprising largely of the traditional Islamic teachings which influenced him throughout his life.<ref name="Bruce St John 135-36">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 135–136.</ref> Subsequently moving to nearby Sirte to attend elementary school, he progressed through six grades in four years. Education in Libya was not free, and paying for it strained his impoverished family's resources. During the week he slept in the local [[mosque]], and at weekends walked 20 miles to visit his parents.<ref name="Bruce St John 136">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 136.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 10">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 10.</ref> From Sirte, he and his family moved to the market town of [[Sabha, Libya|Sabha]] in [[Fezzan]], south-central Libya. Here, his father worked as the caretaker for a local tribal leader while Muammar attended secondary school, something neither parent had done.<ref name="Bruce St John 136"/><ref name="Kawczynski 10-11">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 10–11.</ref> Gaddafi was popular at the school; some friends made there would receive significant jobs in his later administration, most notably his best friend, AbdulSalam Jalloud.<ref name="Kawczynski 11">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 11.</ref> |

|||

Many teachers at Sabha were Egyptian, and for the first time Gaddafi had access to pan-Arab newspapers and radio broadcasts, most notably the [[Cairo]]-based ''[[Voice of the Arabs]]''.<ref name="Bruce St John 136"/><ref name="Kawczynski 11-12">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 11–12.</ref> Growing up, Gaddafi witnessed significant events rock the [[Arab world]], including the [[1948 Arab-Israeli War]], the [[Egyptian Revolution of 1952]], the [[Suez Crisis]] of 1956, and the short-lived existence of the [[United Arab Republic]] between 1958 and 1961.<ref name="Bruce St John 136"/> Gaddafi took an active interest in the political changes being implemented in the [[Egypt|Arab Republic of Egypt]] under the presidency of [[Gamal Abdel Nasser]] of the [[Arab Socialist Union (Egypt)|Arab Socialist Union]], who had ascended to power in 1956. An advocate of [[Arab nationalism]], Nasser argued for greater unity within the Arab world, the rejection of Western [[colonialism]], [[neo-colonialism]], and [[zionism]], and a transition from [[capitalism]] to [[socialism]]. Such ideas inspired Gaddafi, who viewed Nasser as a hero.<ref name="Bruce St John 136"/><ref name="Kawczynski 11-12"/><ref name="Vandewalle 10">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 10.</ref> Becoming actively involved in politics, Gaddafi helped organize demonstrations and distribute posters criticizing the monarchy.<ref name="Bruce St John 136"/><ref name="Kawczynski 11-12"/> |

|||

Such activity caught the authorities' attention, who expelled him from the school and ordered his family to leave Sabha.<ref name="Bruce St John 136"/><ref name="Kawczynski 11"/> Intent on finishing his secondary education, Gaddafi moved to [[Misrata]], where he attended Misrata Secondary School.<ref name="Kawczynski 11"/><ref name="Bruce St John 137">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 137.</ref> Maintaining his interest in Arab nationalist activism, he refused to join any of the banned political parties then active in the city – including the [[Arab Nationalist Movement]], the [[Ba'ath Party#Branches by reason#Libya|Arab Socialist Resurrection (Baath) Party]], and the [[Muslim Brotherhood]] – claiming he rejected factionalism.<ref name="Bruce St John 137"/> He read voraciously, including everything that he could find on the subjects of Nasser and the [[French Revolution of 1789]], as well as the works of Syrian political theorist [[Michel Aflaq]] and biographies of [[Abraham Lincoln]], [[Sun Yat-Sen]], and [[Mustafa Kemal Atatürk]].<ref name="Bruce St John 137"/> |

|||

===Military training: 1963–1966=== |

|||

[[File:Gaddafi in London.jpg|thumb|right|Gaddafi in London, 1966.]] |

|||

Deciding to study History at the [[University of Libya]] in [[Benghazi]], Gaddafi soon dropped out to join the military.<ref name="Bruce St John 138">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 138.</ref> In 1963 he began training at the [[Benghazi Military University Academy|Royal Military Academy]], Benghazi, alongside several friends from Misrata who shared his political views. The armed forces offered the only good opportunity for upward social mobility for Libyans from underprivileged backgrounds such as himself, and was an obvious instrument of political change, having the potential for ousting Idris' absolute monarchy.<ref name="Bruce St John 138"/><ref name="Kawczynski 12">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 12.</ref> With a group of loyal cadres, in 1964 Gaddafi founded the Central Committee of the Free Officers Movement, named after [[Free Officers Movement (Egypt)|the Egyptian group]] founded in 1949 by Nasser, devoting themselves to the revolutionary cause. Led by Gaddafi, they met clandestinely, offering their salaries into a single fund.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 12–13.</ref> Gaddafi traveled around Libya when he could, gathering intelligence and developing connections with those sympathetic to his cause; the government's intelligence services failed to pay much attention, considering him of little threat due to his poor background.<ref name="Kawczynski 13"/> Gaddafi graduated in August 1965,<ref name="Bruce St John 138"/> becoming commissioned as a communications officer in the Libyan Army's signal corps.<ref name="Bruce St John 138"/> |

|||

In April 1966, he was assigned to the [[United Kingdom]] for further training; over nine months he underwent an English-language course at [[Beaconsfield]], [[Buckinghamshire]], a [[Army Air Corps (United Kingdom)|Royal Air Corps]] signal instructors course in [[Bovington Camp]], [[Dorset]], and an infantry signal instructors course at [[Hythe, Kent]].<ref name="Bruce St John 138"/><ref name="Kawczynski 13">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 13.</ref> Despite later rumours to the contrary, he did not attend the [[Royal Military Academy Sandhurst]].<ref name="Kawczynski 13"/><ref>{{cite web| url= http://www.army.mod.uk/documents/general/rmasarchives.pdf| title= The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst's Archives| author=Ministry of Defence, United Kingdom| year= 2009| publisher=Ministry of Defence| page= 1}}</ref> The director of the Bovington signal course put together a report noting that Gaddafi successfully overcame early problems with learning English, displaying a firm command of voice procedure. Noting that Gaddafi's favourite hobbies were reading and playing [[Association football|football]], he thought him an "amusing officer, always cheerful, hard-working, and conscientious."<ref name="Bruce St John 138-39">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 138–139.</ref> Gaddafi disliked his time in England, claiming British Army officers racially insulted him and finding it difficult adjusting to the country's culture; asserting his Arab identity in [[London]], he walked around [[Piccadilly]] wearing traditional Libyan robes. He later related that while he traveled to England believing it more advanced than Libya, he returned home "more confident and proud of our values, ideals and social character."<ref name="Kawczynski 13"/><ref name="Bruce St John 139">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 139.</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1375227/Libya-Portrait-young-Gaddafi-shows-nutcase-loathed-ugly-British.html|title=Portrait of the young Gaddafi: A nutcase who loathed the 'ugly British' and was so unworldly he drank water from a finger bowl|work=Daily Mail|location=London |date=13 April 2011|accessdate=6 September 2011|first1=Sharon|last1=Churcher|first2=Robert|last2=Verkaik}}</ref> |

|||

==Libyan Arab Republic== |

|||

===Coup d'etat: 1969=== |

|||

[[File:Flag_of_Libya_(1969–1972).svg|thumb|right|180px|[[Flag of Libya|Flag]] of the Libyan Arab Republic (1969–1977).]] |

|||

The government of King Idris had become increasingly unpopular by the latter part of the 1960s. After the discovery of oil in Libya in 1959, the government had begun to take advantage of this, beginning the commodity's export in 1963, providing a huge boost to the country's economy. In an attempt to make the oil industry as profitable as possible, the government replaced the federal system with a centralized one, causing problems in a country that was deeply divided along regional, ethnic and tribal lines.<ref name="Kawczynski 15-16">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 15–16.</ref> Within the oil industry, corruption was widespread, with entrenched systems of patronage.<ref name="Kawczynski 16">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 16.</ref> Arab nationalism was becoming increasingly popular across Libya, and protests flared up in 1967, following Egypt's defeat in the [[Six Day War]] with Israel; being allies with the U.S. and European powers, the Idris administration was seen as favorable to Israel, and therefore anti-Arab. Anti-western riots broke out in Tripoli and Benghazi, while Libyan workers shut down the oil terminals in solidarity with Egypt.<ref name="Kawczynski 16-17">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 16–17.</ref> By 1969, the U.S. [[Central Intelligence Agency]] were expecting segments of the Libyan armed forces to institute a ''coup d'etat'', but had no knowledge of Gaddafi's Free Officers Movement, instead monitoring a separate revolutionary group known as the Black Boots, led by Abdul Aziz Shalhi.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 139–140.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 19"/> |

|||

In mid-1969, King Idris traveled abroad to spend the summer in Turkey and Greece. Gaddafi's Free Officers recognized this as their chance to overthrow the monarchy, initiating a plan that they called "Operation Jerusalem".<ref name="Kawczynski 18">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 18.</ref> On 1 September, they occupied airports, police depots, radio stations and government offices in Tripoli and Benghazi.<ref name="Kawczynski 18"/> Gaddafi addressed the populace by radio, proclaiming an end to the old regime, "the stench of which has sickened and horrified us all."<ref name="Kawczynski 18"/> Idris' nephew, Crown Prince [[Hasan as-Senussi|Sayyid Hasan ar-Rida al-Mahdi as-Sanussi]], was formally deposed by the revolutionary officers and put under [[house arrest]]; having overthrown and abolished the monarchy, Gaddafi proclaimed the foundation of the [[History of Libya under Muammar Gaddafi|Libyan Arab Republic]].<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/september/1/newsid_3911000/3911587.stm|title=Bloodless coup in Libya|publisher=BBC News |date=20 December 2003|accessdate=14 February 2010|location=London}}</ref> They did not meet any serious resistance, and they wielded little violence against the monarchists.<ref name="Kawczynski 18"/> Due to the bloodless nature of the ''coup'', it was initially labelled the "White Revolution", although later became known as the "One September Revolution" after the date on which it occurred.<ref name="Bruce St John 134">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 134.</ref> Gaddafi was insistent that the Free Officers' ascent to power represented not just a ''coup'' but a revolution, representing the start of a widespread change in the socioeconomic and political nature of Libyan society.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 159.</ref> He would proclaim that the revolution meant "freedom, [[socialism]], and unity" for Libya, and over the coming years would implement measures to achieve this.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 148.</ref> |

|||

===Consolidating leadership: 1969–1973=== |

|||

Setting up a new government, the 12 member central committee of the Free Unionist Officers converted themselves into a [[Libyan Revolutionary Command Council|Revolutionary Command Council]] (RCC), who wielded control over the newly proclaimed Libyan Arab Republic.<ref name="Bruce St John 134"/><ref name="Vandewalle 9"/> Captain Gaddafi promoted himself to the rank of Colonel, and was recognized as both leader of the RCC as well as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, becoming the ''de facto'' head of state.<ref name="Bruce St John 134"/> Although the RCC was theoretically a collegial body that operated through discussion and consensus building, from the start it was dominated by the opinions and decisions of Gaddafi,<ref name="Bruce St John 134"/> although some of the others attempted to constrain what they saw as his excesses.<ref name="Kawczynski 20">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 20.</ref> Gaddafi remained the public face of the government, with the identities of the other RCC members only being publicly revealed in the ''Official Gazette'' on 10 January 1970.<ref name="Bruce St John 134"/><ref name="Vandewalle 9"/> All of them were young men, from (typically rural) working and middle-class backgrounds, and none had university degrees; in this way they were all distinct from the wealthy, highly educated conservatives who had previously governed the country.<ref name="Vandewalle 10">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 10.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 20"/> The coup completed, the RCC then proceeded with their intentions of consolidating the revolutionary government and modernizing the country.<ref name="Bruce St John 134"/> As a result, they began to purge monarchists and members of Idris' [[Senussi]] clan from Libya's political world and armed forces; Gaddafi believed that this elite were opposed to the will of the Libyan people and had to be expunged.<ref name="Vandewalle 11">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 11.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 21"/><ref name="Kawczynski 23"/> They maintained the previous administration's ban on political parties, and [[rule by decree|ruled by decree]].<ref name="Vandewalle 11"/><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 153.</ref> |

|||

====Economic and social reform==== |

|||

With [[crude oil]] being the country's primary export, Gaddafi sought to improve the position of the Libyan oil sector. In October 1969, he proclaimed that the current trade terms were unfair, benefiting foreign oil corporations more than the Libyan state, and in December the RCC began successful talks to increase the price at which they sold their country's oil by threatening to reduce production. In 1970, other [[OPEC]] states followed suit, leading to a global increase in the price of crude oil.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 145–146.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=yXBRAAAAIBAJ&sjid=Aw8EAAAAIBAJ&pg=7216,2358896 |title='Shotgun Wedding' For the Companies |work=Lakeland Ledger|date=8 October 1972 |accessdate=14 August 2012}}</ref> The RCC followed this with further talks with the oil companies operating in Libya, known as the Tripoli Agreement, in which they secured income tax, back-payments and better pricing; these measures would bring Libya an estimated $1 billion in additional revenues in its first year.<ref name="Bruce St John 147">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 147.</ref><ref name="Vandewalle 15">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 15.</ref> Further increasing state control over the oil sector, the RCC began a program of [[nationalization]], starting with the expropriation of [[British Petroleum]]'s share of the British Petroleum-N.B. Hunt Sahir Field in December 1971. In September 1973, this was followed by the announcement that all foreign oil producers active in the country were to be nationalized under state control. For Gaddafi, this was an important step towards establishing socialism.<ref name="Bruce St John 147">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 147.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Sadat Qaddafi Assad 1971.jpg|thumb|left|250px|[[Anwar Sadat]], Muammar Gaddafi and [[Hafez al-Assad]] signing in 1971 the federation agreement of the three countries within the Union of Arab Republics.]] |

|||

The RCC also attempted to suppress regional and tribal affiliation in the country, instead replacing it with a unified pan-Libyan identity. In doing so, they tried to discredit tribal leaders, tying them to the old colonial regime, and in August 1971 a military court was assembled in Sebha to put many of them on trial for counter-revolutionary activity.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 154.</ref> Long-standing administrative boundaries were re-drawn, crossing tribal boundaries, while pro-revolutionary modernizers were brought in to replace traditional leaders, but the communities that they served often rejected them for more established figures.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 154–155.</ref> Realizing the failures of the modernizers, on 11 June 1971, Gaddafi proclaimed the creation of the [[Libyan Arab Socialist Union|Arab Socialist Union]] (ASU), a mass mobilization [[vanguard party]] of which he would be president. The ASU recognized the RCC as its "Supreme Leading Authority", and was designed to further revolutionary enthusiasm throughout the country.<ref name="Vandewalle 11">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 11.</ref><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 155.</ref> |

|||

The RCC also implemented measures for social reform, adopting Gaddafi's Islamic moral beliefs as a basis. [[Sharia]] law was implemented, the consumption of alcohol was banned, night clubs and Christian churches were shut down, traditional Libyan dress was encouraged, Arabic was decreed as the only language permitted in official communications and road signs, and the months of the [[Gregorian calendar]] were renamed.<ref name="Bruce St John 134"/><ref name="Kawczynski 21">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 21.</ref><ref name="Vandewalle 31">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 31.</ref> From 1969 to 1973, the government introduced social welfare programs, funded with oil money, which led to house-building projects and improved healthcare; education remained a lesser priority. In doing so, they greatly expanded the [[public sector]], providing employment for thousands.<ref name="Kawczynski 23"/><ref name="Bruce St John 149">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 149.</ref> These early social programs proved popular within Libya.<ref name="Bruce St John 149"/><ref name="Kawczynski 22">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 22.</ref> This popularity was in part due to Gaddafi's personal charisma, virility, youth and underdog status, as well as his rhetoric emphasizing his role as the successor to the anti-Italian fighter and national hero [[Omar Mukhtar]].<ref name="Kawczynski 22"/><ref name="Vandewalle 31-32">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. pp. 31–32.</ref> |

|||

====Foreign relations==== |

|||

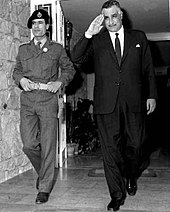

[[File:Nasser Gaddafi 1969.jpg|thumb|upright|Gaddafi (left) with Egyptian President Nasser in 1969.]] |

|||

On its ascendancy to power, the influence of Nasser's Arab nationalism over the RCC was clearly apparent.<ref name="Bruce St John 137"/><ref name="Vandewalle 9">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 9.</ref> The new administration was immediately recognized by four neighboring states with Arab nationalist governments: Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Sudan,<ref name="Kawczynski 18"/> while Egypt sent experts in various fields to aid the RCC, who were unanimously inexperienced in governance.<ref name="Kawczynski 18"/> Gaddafi propounded Pan-Arab ideas, proclaiming the need for a single Arab state stretching across North Africa and the Middle East; in December 1969, Libya founded the [[Arab Revolutionary Front]] with Egypt and Sudan as a step towards political unification, and the following year, Syria stated its intention to join.<ref name="Bruce St John 186">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 186.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 65">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 65.</ref> After Nasser died in November 1970, his successor, [[Anwar Sadat]], suggested that rather than a unified state, they create [[Federation of Arab Republics|a political federation]], implemented in April 1971; in doing so, Egypt, Syria and Sudan got large grants of Libyan oil money.<ref name="Kawczynski 65"/><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 151–152.</ref> In February 1972, Gaddafi and Sadat signed an unofficial charter of merger between Libya and Egypt, but it was never implemented as relations broke down the following year. Sadat became increasingly wary of Libya's radical direction, and the September 1973 deadline for implementing the Federation passed by with no action taken, leaving it defunct.<ref name="Kawczynski 66">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 66.</ref><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 182.</ref><ref name="bangor_201108">{{cite web | url=http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=QRtbAAAAIBAJ&sjid=qk4NAAAAIBAJ&pg=1923,335727| title=Libyan Leader Impatient Over Union With Egypt | publisher=UPI | work=Bangor Daily News | date=3 July 1973 | accessdate=23 August 2011 | page=3}}</ref> |

|||

Straight after the 1969 coup, representatives of the [[Allied Control Council|Four Powers]] – France, the United Kingdom, the United States and the Soviet Union – were called to meet with members of the RCC.<ref name="Bruce St John 140">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 140.</ref> The U.K. and U.S. quickly extended diplomatic recognition to the RCC, hoping to secure the position of their military bases in the country and fearing further instability. Hoping to ingratiate themselves with Gaddafi's administration, in early 1970 the U.S. informed the Libyan regime of at least one planned counter-''coup''.<ref name="Kawczynski 18"/><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 140–141.</ref> Such attempts to form a working relationship with the RCC failed; Gaddafi was determined to reassert Libyan national sovereignty and expunge foreign colonial and imperialist influences. The new administration insisted that the U.S. and U.K. remove their military bases from Libya, with Gaddafi proclaiming that "the armed forces which rose to express the people's revolution [will not] tolerate living in their shacks while the bases of imperialism exist in Libyan territory." The Western powers complied, with the British leaving in March and the Americans in June 1970.<ref name="Kawczynski 19">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 19.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 141143">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 141–143.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Oil Rich Libya.ogv|thumb|left|1972 anti-Gaddafist British [[newsreel]] including interview with Gaddafi about his support for foreign militants.]] |

|||

Moving to reduce Italian influence, in October 1970, all Italian-owned assets were expropriated and the 12,000-strong [[Italian settlers in Libya|Italian community]] expelled from Libyay; the day became a [[Public holiday|national holiday]].<ref name="Bruce St John 142">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 142.</ref><ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 21–22.</ref><ref name="BBC NEWS 271005">[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/4380360.stm Libya cuts ties to mark Italy era.]. BBC News. 27 October 2005.</ref> Aiming to reduce the power of the [[NATO|North Atlantic Treaty Organization]] (NATO) in the Mediterranean, in 1971 Libya requested that [[Malta]] cease to allow NATO to use its land for a military base, in turn offering to provide them with large amounts of foreign aid. Ultimately, the Maltese government continued to allow NATO to use the island for their activity, but only on the condition that they would not use it for launching an attack on any Arab country.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 150–151.</ref> Orchestrating a military build-up, Gaddafi's RCC began purchasing weapons from France and the Soviet Union; the commercial relationship with the latter led to an increasingly strained relationship with the U.S., who were then engaged in the [[Cold War]] with the Soviets.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 144–145.</ref> |

|||

Gaddafi was especially critical of the U.S. due to their support for Israel; Gaddafi supported the [[Palestinians]] in the [[Israeli-Palestinian conflict]], viewing the 1948 creation of Israel as an oppressive indignity forced on the Arab world by Western colonialists.<ref name="Vandewalle 34">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 34.</ref><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 150–152.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 64">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 64.</ref> In 1970, he initiated a Jihad Fund to finance those battling Israel,<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 185.</ref> and in a 11 June 1972 speech, announced the creation of the First Nasserite Volunteers Centre to train guerrillas in tactics against the [[Zionism|Zionist]] state.<ref name="Bruce St John 151">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 151.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 37">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 37.</ref> His relationship with Palestinian leader [[Yasser Arafat]] of [[Fatah]] was strained, with Gaddafi considering him too moderate and calling for more violent action.<ref name="Kawczynski 37">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 37.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 178"/> He funded the [[Black September (group)|Black September]] group who perpetrated the 1972 [[Munich massacre]] of Israeli athletes in [[West Germany]]; Gaddafi had the militants' bodies flown to Libya for a hero's funeral.<ref name="Bruce St John 178">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 178.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 38">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 38.</ref> Using Libya's oil wealth, Gaddafi financially supported other militant groups across the world, including the [[Black Panther Party]] and [[Nation of Islam]] in the U.S., the [[Provisional Irish Republican Army]] in the U.K., [[ETA]] in Spain, the [[Red Brigades]] in Italy, the [[Red Army Faction]] in West Germany, the [[Sandinista National Liberation Front]] in Nicaragua, the [[Japanese Red Army|Red Army]] in Japan, the [[Free Aceh Movement]] in Indonesia and the [[Moro National Liberation Front]] in the Philippines. Gaddafi remained indiscriminate in the causes he funded, sometimes switching from supporting one side in a conflict to the other, as in the [[Eritrean War of Independence]]. Throughout the rest of the 1970s, these groups received financial support from Libya, which came to be seen as a leader in the [[Third World]]'s struggle against colonialism and neocolonialism.<ref name="Bruce St John 151">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 151.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 34-35">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 34–35, 40–53.</ref> |

|||

===The "Popular Revolution": 1973–1977=== |

|||

[[File:Green book.jpg|thumb|right|Gaddafi's ''Green Book''.]] |

|||

On 16 April 1973, Gaddafi gave a speech in [[Zuwara]] proclaiming the start of a "Popular Revolution" in Libya.<ref name="Kawczynski 22"/><ref name="Vandewalle 12">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 12.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 156">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 156.</ref> He initiated this new beginning with a five-point plan, the first point of which dissolved all existing laws, which were to be replaced by revolutionary enactments. The second point proclaimed that all opponents of the revolution had to be removed, while the third initiated an administrative revolution that Gaddafi proclaimed would remove all traces of [[bureaucracy]] and the [[bourgeoisie]] from Libya. The fourth point announced that the population must be armed to defend the revolution, while the fifth proclaimed the beginning of a cultural revolution that would expunge Libya of foreign influences.<ref name="Kawczynski 22"/><ref name="Bruce St John 156">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 156.</ref> |

|||

As a part of this Popular Revolution, Gaddafi invited the Libyan people to found [[General People's Committee]]s across the country, as conduits for raising political consciousness. Although he offered little guidance for how people should go about setting up these councils, Gaddafi exclaimed that they would offer a form of [[Direct democracy|direct]] [[Participatory democracy|political participation]] for all Libyans that was innately more democratic than a traditional party-based [[Representative democracy|representative system]]. In doing so, he hoped that the councils would mobilize the people behind the RCC, erode the power of the traditional leaders and the traditional bureaucracy, and allow for the formation of a new revolutionary legal system chosen by the people.<ref name="Bruce St John 156"/> The People's Committees led to a high percentage of public involvement in decision making, within the limits permitted by the RCC.<ref name="Bruce St John 157">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 157.</ref> They also served as a surveillance system, aiding the security services in locating individuals with views critical of the RCC, leading to the arrest of [[Ba'athism|Ba'athists]], [[Marxism|Marxists]] and [[Islamism|Islamists]].<ref name="Bruce St John 157"/><ref name="Mohamed Eljhami">{{cite web|url=http://www.meforum.org/878/libya-and-the-us-qadhafi-unrepentant|title=Libya and the U.S.: Qadhafi Unrepentant|publisher=The Middle East Quarterly|author=Mohamed Eljahmi|year=2006}}</ref> The base form of these Revolutionary Committees were the local working groups, who proceeded to send elected representatives to the district level, and from that to the national level – divided between the [[General People's Congress (Libya)|General People's Congress]] and the [[General People's Committee]] – in a pyramid structure.<ref name="Kawczynski 26">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 26.</ref> Above these Committees remained Gaddafi and the RCC, who ultimately remained responsible for all major decisions.<ref name="Bruce St John 163">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 163.</ref> |

|||

====Third Universal Theory and ''The Green Book''==== |

|||

In June 1973, Gaddafi announced the creation of a political ideology that would underpin the new Popular Revolution. Referred to as "[[Third Universal Theory]]", it rejected the [[capitalism]] of the western world and the [[atheism]] of the [[communism|communist]] powers, proclaiming that both the United States and the Soviet Union were imperialist.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 157–158.</ref> As a part of this theory, Gaddafi praised [[nationalism]] as a progressive force and continued to advocate the creation of a pan-Arab state which would lead both the Islamic and Third Worlds against the forces of imperialism.<ref name="Bruce St John 158">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 158.</ref> Gaddafi saw [[Islam]] as having a key role in this ideology, calling for an Islamic Revival that returned to the origins of the [[Qur'an]], rejecting scholarly interpretations and the [[Hadith]]; in doing so he angered many Libyan clerics.<ref name="Bruce St John 159">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 159.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Kadaffi lopez rega.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Gaddafi and the Argentine Commissioner General [[José López Rega]].]] |

|||

Gaddafi summarized his thought regarding Third Universal Theory in three short volumes published between 1975 and 1979, that were collectively known as ''[[The Green Book (Muammar Gaddafi)|The Green Book]]''. The first volume, ''The Solution of the Problem of Democracy: The Authority of the People'', was devoted to the issue of democracy, outlining the flaws of representative systems in favor of direct, participatory democracy in the form of his Revolutionary Committees. The second, ''The Solution of the Economic Problem'', dealt with Gaddafi's beliefs regarding socialism, while the third, ''The Social Basis of the Third International Theory'', explored social issues regarding the family and the tribe. While the first two volumes had expressed views advocating radical reform, the third adopted a socially conservative stance, proclaiming that while men and women were equal, they were biologically designed for different roles in life.<ref name="Vandewalle 19">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 19.</ref><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 161–165.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 24">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 24.</ref> In ensuing years, government supporters would adopt quotes from ''The Green Book'', such as "Representation is Fraud", as revolutionary slogans.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 162.</ref> |

|||

The swift implementation of these radical reforms led to discontent, furthered by widespread opposition to the RCC's decision to spend oil money on foreign causes, and in 1975, there were student demonstrations against Gaddafi's government. The RCC responded with mass arrests, and introduced compulsory [[national service]] for young people.<ref name="Kawczynski 23">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 23.</ref><ref name="Vandewalle 18">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 18.</ref> Dissent also arose from conservative clerics and the Muslim Brotherhood, many of whom began to preach against the government, subsequently being persecuted as anti-revolutionary elements.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 29–30.</ref> Two members of the RCC, Bashir Saghir al-Hawaadi and Omar Mehishi, had become particularly concerned with Gaddafi's social experiment, and decided to launch a ''coup d'etat'' to overthrow him that year. They failed, and in the aftermath only five of the original twelve RCC members remained in power.<ref name="Kawczynski 23"/><ref name="Vandewalle 18"/><ref name="Bruce St John 165">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 165.</ref> Ultimately, this led to collapse of the RCC, which would be officially abolished in March 1977.<ref name="Bruce St John 165"/> Meanwhile, in September 1975 Gaddafi implemented further measures to increase popular mobilization, introducing objectives to try and improve the relationship between the Revolutionary Committees and the ASU.<ref name="Bruce St John 165"/> He also began to appoint members of his family and tribe to high positions in the security and armed forces.<ref name="Vandewalle 19">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 19.</ref> |

|||

====Foreign relations==== |

|||

[[File:Gaddafi 1976.jpg|thumb|175px|Gaddafi in 1976 with a child on his lap.]] |

|||

Following Anwar Sadat's ascension to the Egyptian presidency, Libya's relations with Egypt deteriorated. Sadat was perturbed by Gaddafi's unpredictability and insistence that Egypt required a cultural revolution.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 66.</ref> In February 1973, Israeli forces shot down [[Libyan Arab Airlines Flight 114|Libyan Arab Airlines (LAA) Flight 114]], which had strayed from Egyptian airspace into Israeli-held territory during a sandstorm. Gaddafi was infuriated that Egypt had not done more to prevent the incident, and in retaliation planned to destroy the ''[[RMS Queen Elizabeth 2]]'', a British ship chartered by American Jews to sail to [[Haifa]] for Israel's 25th anniversary. Gaddafi ordered an Egyptian submarine to target the ship, but Sadat discovered and cancelled the order, fearing a military escalation.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 66–67.</ref> The [[Yom Kippur War]] between an Egyptian-Syrian alliance and Israel also led to the deterioration of relations between the two leaders; Gaddafi was infuriated that he had not been consulted on the war plans, and was angry that Egypt eventually conceded to peace talks with Israel, believing that they should have fought on till victory.<ref name="Bruce St John 182-3">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 182–183.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 2011. p. 67">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 67.</ref> Sadat and Gaddafi became openly hostile, the latter proclaiming that Sadat had betrayed Nasser's vision and should be overthrown.<ref name="Kawczynski 2011. p. 67"/> Relations also deteriorated with Sudan, where Islamist President [[Gaafar Nimeiry]] had developed closer links to Egypt and the West; by 1975, Gaddafi was sponsoring merceneries to overthrow Nimeiri, who proclaimed the former to have "a split personality – both parts evil".<ref name="Bruce St John 191">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 191.</ref><ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 79–80.</ref> |

|||

Gaddafi's break with Egypt and Sudan led him to focus his attention on the rest of Africa. Expanding Libyan influence southward, in late 1972 and early 1973, Libya invaded [[Chad]] in order to annex the [[Aouzou Strip]], a desert region suspected of containing underground uranium deposits.<ref name="Bruce St John 187">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 187.</ref> One of his primary ambitions was to reduce Israeli influence in the continent, successfully convincing eight states to break off diplomatic relations with Israel in 1973, offering financial incentives to do so.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 77.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 184">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 184.</ref> Intent on propagating Islam, in 1973 Gaddafi founded the Islamic Call Society, which had begun operations in 132 centers across Africa within a decade.<ref name="Bruce St John 186"/> He achieved early success, in 1973 converting Gabonese President [[Omar Bongo]] to the faith, which he repeated three years later with [[Jean-Bédel Bokassa]], president of the [[Central African Republic]].<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 77–78.</ref> Gaddafi sought to develop closer links in the [[Maghreb]] area of northwest Africa. In January 1974, Libya and Tunisia announced a political union, forming the [[Arab Islamic Republic]]; although advocated by Gaddafi and Tunisian President [[Habib Bourguiba]], the move was deeply unpopular within Tunisia, and soon abandoned.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 71–72.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 183">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 183.</ref> Retaliating, Gaddafi sponsored anti-government militants in Tunisia into the 1980s.<ref name="Bruce St John 183"/><ref name="Kawczynski 72">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 72.</ref> Turning his attention to Algeria, in 1975, Libya signed the Hassi Messaoud defence agreement to counter the threat of Moroccan expansionism, also funding the [[Polisario Front]] of [[Western Sahara]] in their liberation struggle against Morocco.<ref name="Bruce St John 183"/><ref name="Kawczynski 71">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 71.</ref> |

|||

==Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya== |

|||

===Foundation: 1977=== |

|||

[[File:Flag of Libya (1977-2011).svg|thumb|right|200px|[[Flag of Libya|Flag]] of the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya.]] |

|||

On 2 March 1977 the General People's Congress adopted the "Declaration of the Establishment of the People's Authority" at Gaddafi's behest. Dissolving the Libyan Arab Republic, it was replaced by the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya ({{lang-ar|الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الاشتراكية}}, ''{{transl|ar|al-Jamāhīrīyah al-‘Arabīyah al-Lībīyah ash-Sha‘bīyah al-Ishtirākīyah}})'', a "state of the masses" conceptualized by Gaddafi.<ref name="Bruce St John 166-168">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 166–168.</ref><ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 26–27.</ref> Officially, the ''Jamahiriya'' was a [[direct democracy]] in which the people ruled themselves through [[Basic People's Congress (political)|Basic People's Congress]]es, where all adult Libyans participated and voted on national decisions. In principle, the People's Congresses were Libya's highest authority, with major decisions proposed by government officials or Gaddafi himself requiring the consent of the People's Congresses.<ref name="Bruce St John 166-168"/><ref name="Vandewalle 19-20">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. pp. 19–20.</ref> Gaddafi proclaimed that the People's Congresses provided for Libya's every political need, rendering other political organizations unnecessary; all non-authorized groups, including political parties, professional associations, independent trade unions and women's groups, were banned.<ref name="Bruce St John 166-168"/><ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 27.</ref> |

|||

With preceding legal institutions abolished, Gaddafi envisioned the ''Jamahiriya'' as following the [[Qur'an]] for legal guidance, adopting Islamic [[sharia]] law; he proclaimed "man-made" laws unnatural and dictatorial, only permitting [[God in Islam|God]]'s law.<ref name="Bruce St John 167">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 167.</ref><ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 27–28.</ref> Within a year he was backtracking, announcing that sharia was innapropriate for the ''Jamahiriya'' because it guaranteed the protection of private property, contravening ''The Green Book'''s socialism.<ref name="Vandewalle 28">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 28.</ref> In July, a [[Libyan–Egyptian War|border war broke out]] with Egypt, in which the Egyptians defeated Libya despite their technological inferiority. The conflict lasted a week before both sides agreed to a peace treaty brokered by several Arab states.<ref name="Bruce St John 183">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 183.</ref><ref name="Vandewalle 35">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 35.</ref><ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 67–68.</ref> That year, Gaddafi was invited to [[Moscow]] by the Soviet government in recognition of their increasing commercial relationship.<ref name="Bruce St John 180">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 180.</ref> |

|||

===Revolutionary Committees and furthering socialism: 1978–1980=== |

|||

In December 1978, Gaddafi stepped down as Secretary-General of the General People's Congress (GPC), announcing his wish to focus on revolutionary rather than governmental activities; this was a part of his new emphasis on separating the apparatus of the revolution from the apparatus of government. Adopting the title of "Leader of the Revolution", he continued as commander-in-chief of the armed forces.<ref name="Vandewalle 26">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 26.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 31">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 3.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 169">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 169.</ref> Gaddafi continued exerting considerable influence over Libya, with many critics insisting that the structure of Libya's direct democracy gave him "the freedom to manipulate outcomes",<ref name="bbc_robbins">{{cite news|last=Robbins|first=James|title=Eyewitness: Dialogue in the desert|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/6425873.stm|accessdate=22 October 2011|date=7 March 2007|work=BBC News}}</ref> comparing him to a [[demagogue]].<ref name="nytimes_green">{{cite news|last=Bazzi|first=Mohamad|title=What Did Qaddafi’s Green Book Really Say?|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/29/books/review/what-did-qaddafis-green-book-really-say.html|accessdate=28 October 2011|newspaper=[[The New York Times]]|date=27 May 2011}}</ref> On 2 March 1979, the GPC announced the separation of government and revolution, the latter being represented by new Revolutionary Committees, who operated in tandem with the People's Committees in schools, universities, unions, the police force and the military. Dominated by revolutionary zealots, the Reolutionary Committees were accountable to the "Leader of the Revolution", whom they met annually, and were coordinated by a Central Coordinating Office for Revolutionary Committees. Publishing their own weekly magazine, ''The Green March'' (''al-Zahf al-Akhdar''), in October 1980 they took control of all press. Responsible for perpetuating revolutionary fervor, they performed ideological surveillance, later adopting a significant security role, making arrests and putting people on trial according to the "law of the revolution" (''qanun al-thawra'').<ref name="Kawczynski 31">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 31.</ref><ref>[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. pp. 25–26.</ref><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 169–171.</ref> With no legal code or safeguards, the administration of revolutionary justice was largely arbitrary and resulted in widespread abuses and the suppression of [[civil liberties]].<ref name="Vandewalle 28">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 28.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 174">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 174.</ref> |

|||

{{Quote box|width=246px|bgcolor=#ACE1AF|align=right|quote="If socialism is defined as a redistribution of wealth and resources, a socialist revolution clearly occurred in Libya after 1969 and most especially in the second half of the 1970s. The management of the economy was increasingly socialist in intent and effect with wealth in housing, capital and land significantly redistributed or in the process of redistribution. Private enterprise was virtually eliminated, largely replaced by a centrally controlled economy."|salign = right |source=— Libyan Studies scholar Ronald St Bruce.<ref name="Bruce St John 173">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 173.</ref>}} |

|||

1978 saw the Libyan government push towards socialism. In March, they published guidelines for housing redistribution, attempting to ensure that every adult Libyan owned their own home and was not "enslaved" to paying rent. Most families were banned from owning more than one house, and houses that had formerly been rented were expropriated by the government and sold to the tenants at a heavily subsidized price.<ref name="Bruce St John 171-72">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 171–172.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 221">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 221.</ref> In September, Gaddafi called for the People's Committees to eliminate the "bureaucracy of the public sector" and the "dictatorship of the private sector"; the People's Committees seized control of several hundred companies, converting them into workers' cooperatives run by elected representatives.<ref name="Bruce St John 168">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 168.</ref> In 1979, the committees began redistribution of land in the Jefara plain, continuing through to 1981.<ref name="Bruce St John 172">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 172.</ref> In May 1980, measures to redistribute and equalize wealth were implemented; anyone with over 1000 [[dinar]] in their bank account saw that extra money expropriated.<ref name="Kawczynski 221">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 221.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 172"/> The following year, the GPC announced that the government would take control of all import, export and distribution functions, with state supermarkets replacing privately owned businesses; this led to a decline in the availability of consumer goods and the development of a thriving [[black market]].<ref name="Bruce St John 172"/><ref>[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 21.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 220">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 220.</ref> |

|||

The ''Jamahiriya'''s radical socialist direction and revolutionary justice earned the government many enemies. Many who had seen their wealth and property confiscated turned against the administration, and a number of western-funded opposition groups were founded by exiles; most prominent was the [[National Front for the Salvation of Libya]] (NFSL), founded in 1981 by [[Mohammed Magariaf]], which orchestrated militant attacks against Libya's government.<ref name="Vandewalle 32">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 32.</ref><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 173–174.</ref> The Revolutionary Committees set up overseas branches to suppress such counter-revolutionary activity, assassinating various dissidents.<ref name="Vandewalle 27">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 27.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 171">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 171.</ref> In 1979, the U.S. government placed Libya on their list of [[state sponsors of terrorism]],<ref name="Bruce St John 179">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 179.</ref> while at the end of the year [[1979 U.S. embassy burning in Libya|a demonstration torched the U.S. embassy]] in Tripoli.<ref name="Bruce St John 179">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 179.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 115">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 115.</ref> The following year, Libyan fighters began intercepting U.S. flighter jets flying over the Mediterranean, signalling the collapse of relations between the two countries.<ref name="Bruce St John 179">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 179.</ref> Libyan relations with [[Lebanon]] also deteriorated over the 1978 disappearance of Shia imam [[Musa al-Sadr]] when on a visit to Libya; the Lebanese accused Gaddafi of having him killed or imprisoned, a charge he denied.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 70–71.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 239">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 239.</ref> Relations with Syria improved, as Gaddafi and Syrian President [[Hafez al-Assad]] shared an enmity with Israel and Egypt's Sadat. In 1980, they proposed a political union, with Libya paying off Syria's £1 billion debt to the Soviet Union; although pressures led Assad to pull out, they remained allies.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 68–69.</ref> Another key ally was Uganda, and in 1979, Gaddafi unsuccessfully sent troops into [[Uganda-Tanzania War|Uganda to defend the regime]] of his friend, President [[Idi Amin]], from Tanzanian invaders.<ref name="Bruce St John 189">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 189.</ref><ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 78–79.</ref> |

|||

==="International Pariah": 1981–1986=== |

|||

[[File:Leptis magna museum.jpg|thumb|left|Image of Gaddafi at the [[Leptis Magna Museum]] in [[Khoms, Libya]].]] |

|||

The early and mid 1980s saw economic trouble for Libya; from 1982 to 1986, the country's annual oil revenues dropped from $21 billion to $5.4 billion.<ref name="Vandewalle 23">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 23.</ref><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 192.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 104">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 104.</ref> Focusing on irrigation projects, 1983 saw construction start on the [[Great Manmade River]]; although designed to be finished by the end of the decade, it would still be incomplete at the start of the 21st century.<ref name="Bruce St John 249">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 249.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 224">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 224.</ref> Military spending increased, while other administrative budgets were cut back.<ref name="Vandewalle 35">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 35.</ref> In December 1980, Libya re-invaded Chad at the request of the [[Transitional Government of National Unity|GUNT government]] to aid in the civil war; in January 1981, Gaddafi suggested a political merger. The [[Organisation of African Unity]] (OAU) rejected this, and called for a Libyan withdrawal, which came about in November 1981.<ref name="Vandewalle 35">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 35.</ref><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 189–190.</ref> Many African nations had tired of Libya's policies of interference in foreign affairs; by 1980, nine African states had cut off diplomatic relations with Libya,<ref name="Bruce St John 189">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 189.</ref> while in 1982 the OAU cancelled its scheduled conference in Tripoli in order to prevent Gaddafi gaining chairmanship.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 190–191.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 81">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 81.</ref> Proposing political unity with Morocco, in August 1984, Gaddafi and Moroccan monarch [[Hassan II of Morocco|Hassan II]] signed the Oujda Treaty, forming the Arab-African Union; such a union was considered surprising due to the strong political differences that existed between the two governments. Relations remained strained, particularly due to the Moroccan regime's friendly relations with the U.S. and Israel; in August 1986, Hassan abolished the union.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 72–75.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 216">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 216.</ref> |

|||

In 1980, [[Ronald Reagan]] was elected to the U.S. presidency, and famously declaring Gaddafi to be both an "international pariah" and the "mad dog of the middle east", he pursued a hard line approach to Libya, erroneously considering its government a [[puppet regime]] of the Soviet Union.<ref name="Bruce St John 179-180">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 179–180.</ref><ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 115–116, 120.</ref> In turn, Gaddafi played up his commercial relationship with the Soviets, visiting again in 1981 and threatening to join the [[Warsaw Pact]].<ref name="Kawczynski 115">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 115.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 210-11">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 210–211.</ref> Beginning U.S. military exercises in the Gulfe of Sirte – an area of sea that Libya claimed as a part of its territorial waters – [[Gulf of Sidra incident (1981)|in August 1981 the U.S. shot down]] two Libyan [[Sukhoi Su-17|Su-22]] planes that were monitoring them.<ref name="Vandewalle 36">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 36.</ref><ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 118–119.</ref> Closing down the Libyan embassy in Washington D.C., Raegan advised U.S. companies operating in the country to reduce the number of American personnel stationed there.<ref name="Bruce St John 180">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 180.</ref><ref name="Vandewalle 37">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 37.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 117-18">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 117–118.</ref> In March 1982, the U.S. implemented an embargo of Libyan oil,<ref name="Vandewalle 37">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 37.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 117-18">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 117–118.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 181">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 181.</ref> and in 1986 ordered all U.S. companies to cease operating in the country.<ref name="Kawczynski 117-18">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 117–118.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 176">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 176.</ref> Relations were also strained with the U.K., particularly after Libyan diplomats were accused of shooting dead [[Yvonne Fletcher]], a British policewoman stationed outside their London embassy, in April 1984.<ref name="Vandewalle 37">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 37.</ref><ref name="Bruce St John 209">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 209.</ref> In Spring 1986, [[Action in the Gulf of Sidra (1986)|the U.S. Navy again began performing exercises in the Gulf of Sirte]]; the Libyan military retaliated, but failed as the U.S. sank several Libyan ships.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 121–122.</ref> |

|||

After the U.S. accused Libya of orchestrating the [[1986 Berlin discotheque bombing]], in which two American soldiers died, Reagan decided to retaliate militarily.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 122.</ref> In doing so, he was supported by the U.K. but opposed by other European allies, who highlighted that it would contravene international law.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 123–125.</ref> In [[1986 United States bombing of Libya|Operation El Dorado Canyon]], orchestrated on 15 April 1986, U.S. military planes launched a series of air-strikes on Libya, bombing military installations in various parts of the country, killing around 100 Libyans, some of whom were civilians. One of the targets had been Gaddafi's home in the [[Bab al-Azizia]] barrack, in which his four-year-old adopted daughter Hanna was killed.<ref name="Vandewalle 37">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 37.</ref><ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 127–129.</ref> In the immediate aftermath, Gaddafi retreated to the desert to meditate.<ref name="Kawczynski 130">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 130.</ref> Although the U.S. was condemned internationally, Reagan received a popularity boost at home.<ref name="Kawczynski 130"/> The attack also strengthened Gaddafi domestically, who publicly attacked the imperialism of the U.S.<ref name="Bruce St John 196">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 196.</ref> |

|||

==="Revolution within a Revolution": 1987–1998=== |

|||

The late 1980s saw a series of liberalising economic reforms within Libya designed to cope with the decline in oil revenues. In May 1987, Gaddafi announced the start of the "Revolution within a Revolution", which began with reforms to industry and agriculture and saw the re-opening of small business.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 194.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 225">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 225.</ref> Restrictions were placed on the activities of the Revolutionary Committees; in March 1988, their role was narrowed by the newly created Ministry for Mass Mobilization and Revolutionary Leadership to restrict their violence and judicial role, while in August 1988 Gaddafi publicly criticised them,<ref name="Vandewalle 29">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 29.</ref><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 194–195, 199–200.</ref> asserting that "they deviated, harmed, tortured" and that "the true revolutionary does not practise repression."<ref name="ham_40_1">{{cite book|last=Ham|first=Anthony|title=Libya|year=2007|publisher=[[Lonely Planet]]|location=Footscray, Victoria|isbn=1-74059-493-2|url=http://books.google.com/?id=lPaNiy3YisIC|edition=2nd ed.|pages=40–1}}</ref> In March, hundreds of political prisoners were freed, with Gaddafi erroneously claiming that there were no further political prisoners in Libya.<ref name="Vandewalle 45">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 45.</ref><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 222.</ref> In June, the Libyan government issued the Great Green Charter on Human Rights in the Era of the Masses, in which 27 articles laid out goals, rights and guarantees to improve the situation of human rights in Libya, restricting the use of the [[death penalty]] and calling for its eventual abolition. Many of the measures suggested in the charter would be implemented the following year, although others remained inactive.<ref name="Vandewalle 45-46">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. pp. 45–46.</ref><ref name="ReferenceA">[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 197–198.</ref> Also in 1989, the Libyan government founded the [[Al-Gaddafi International Prize for Human Rights]], to be awarded to figures from the Third World who had struggled against colonialism and imperialism; the first year's winner was South African anti-apartheid activist [[Nelson Mandela]].<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 199.</ref> From 1994 through to 1997, the Libyan government initiated cleansing committees to root out corruption, particularly in the economic sector.<ref name="ReferenceA"/> |

|||

[[File:Muammar Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi in Dimashq, Syria.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Gaddafi with his [[Amazonian Guard]] in [[Damascus]], [[Syria]].]] |

|||

In the aftermath of the 1986 U.S. attack, the army was purged of perceived disloyal elements,<ref name="Kawczynski 130">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 130.</ref> and in 1988, Gaddafi announced the creation of a popular militia to replace the army and police.<ref name="Vandewalle 38">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 38.</ref><ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 200.</ref> In 1987, [[Libya and weapons of mass destruction|Libya began production]] of [[mustard gas]] at a facility in Rabta, although publicly denied it was stockpiling chemical weapons,<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 201–204.</ref> and unsuccessfully attempted to develop nuclear weapons.<ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 180–181.</ref> The period also saw a growth in domestic [[Islamism|Islamist]] opposition, formulated into groups like the [[Muslim Brotherhood]] and the [[Libyan Islamic Fighting Group]]. A number of assassination attempts against Gaddafi were foiled, and in turn, 1989 saw the security forces raid mosques believed to be centres of counter-revolutionary preaching.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. pp. 221–222.</ref><ref>[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. pp. 166–167, 236.</ref> In October 1993, elements of the army initiated a failed coup in [[Misrata]], while in September 1995, Islamists launched an insurgency in Benghazi, and in July 1996 an anti-Gaddafist football riot broke out in Tripoli.<ref>[[#Bru12|Bruce St John 2012]]. p. 223.</ref><ref name="Kawczynski 166">[[#Kaw11|Kawczynski 2011]]. p. 166.</ref> The Revolutionary Committees experienced a resurgence to combat these Islamists.<ref name="Vandewalle 29">[[#Van08|Vandewalle 2008]]. p. 29.</ref> |

|||