King's College London

| File:King's College London crest.png Arms of King's College London | ||||||||||||

| Motto | Sancte et Sapienter (Latin) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Motto in English | With Holiness and Wisdom | |||||||||||

| Type | Public | |||||||||||

| Established | 1829 | |||||||||||

| Endowment | £130.76 million[1] | |||||||||||

| Chancellor | HRH The Princess Royal (University of London) | |||||||||||

| Principal | Sir Rick Trainor | |||||||||||

| Visitor | The Archbishop of Canterbury ex officio | |||||||||||

| Students | 25,187 (2012-13)[2] | |||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 14,997[2] | |||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 10,190[2] | |||||||||||

| Location | London , United Kingdom 51°30′43.00″N 0°06′58.00″W / 51.5119444°N 0.1161111°W | |||||||||||

| Campus | Urban | |||||||||||

| Chairman of the Council | The Marquess of Douro | |||||||||||

| Colours | ||||||||||||

| Affiliations | ACU EUA Golden triangle King's Health Partners Russell Group Universities UK University of London | |||||||||||

| Mascot | Reggie the Lion | |||||||||||

| Website | kcl.ac.uk | |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, United Kingdom, and a constituent college of the federal University of London. King's has a claim to being the third-oldest university in England, having been founded by King George IV and the Duke of Wellington in 1829, receiving its royal charter in the same year.[4][5] In 1836 King's became one of the two founding colleges of the University of London.[6][7][8]

King's is organised into nine academic schools, spread across four Thames-side campuses in central London and another in Denmark Hill in south London.[9] It is one of the largest centres for graduate and post-graduate medical teaching and biomedical research in Europe; it is home to six Medical Research Council centres, the most of any British university,[10] and is a founding member of the King's Health Partners academic health sciences centre. King's has around 25,000 students and 6,113 staff and had a total income of £554.2 million in 2011/12, of which £154.7 million was from research grants and contracts.[1]

King's is ranked 68th in the world (and 19th in Europe) in the 2012 Academic Ranking of World Universities,[11] 26th in the world (and 7th in Europe) in the 2012 QS World University Rankings,[12] and 56th in the world (and 12th in Europe) in the 2012 Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[13] There are currently 10 Nobel Prize laureates amongst King's alumni and current and former faculty.[14] In September 2010, The Sunday Times selected King's as its "University of the Year".[15] King's is a member of the Association of Commonwealth Universities, the European University Association, the Russell Group and Universities UK. It forms part of the 'golden triangle' of British universities.[16]

History

Foundation

King's College, so named to indicate the patronage of King George IV, was founded in 1829 in response to the theological controversy surrounding the founding of "London University" (which later became University College London) in 1827.[17][18] London University was founded, with the backing of Jews, Utilitarians and non-Anglican Christians, as a secular institution, intended to educate "the youth of our middling rich people between the ages of 15 or 16 and 20 or later"[19] giving its nickname, "the godless college in Gower Street".[20]

The need for such an institution was a result of the religious nature of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, which then educated solely the sons of wealthy Anglicans.[21] The secular nature of the institution was met with the disapproval of The Establishment, indeed, "the storms of opposition which raged around it threatened to crush every spark of vital energy which remained".[22] Thus, the creation of a rival institution represented a Tory response to reassert the educational values of The Establishment.[23] More widely, King's was one of the first of a series of institutions which came about in the early nineteenth century as a result of the Industrial Revolution and great social changes in England following the Napoleonic Wars.[24] By virtue of its foundation King's has enjoyed the patronage of the monarch, the Archbishop of Canterbury as its Visitor and during the nineteenth century counted among its official governors the Lord Chancellor, Speaker of the House of Commons and the Lord Mayor of London.[24]

Rumours in the press of a competing institution in the tradition of the established church appeared in 1827, but the idea was first openly defined early in 1828 by Reverend Dr George D'Oyly, Rector of Lambeth, in an open letter to Sir Robert Peel, the then Home Secretary and Leader of the House of Commons.[17][25][26] A scheme emerged during the summer of 1828 and a public meeting to launch King's, chaired by the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, and attended by the Archbishops of York, Canterbury and Armagh and two members of the Cabinet (Peel and the Earl of Aberdeen) was held on 21 June 1828.[17][18] A committee of twenty-seven was appointed to raise funds and to frame regulations and building plans, but the sum raised by subscription was inadequate.[17] However, a site lying between the Strand and the Thames was granted to the College by the Crown and building began in 1829.[17] A royal charter to incorporate King's College was granted by George IV on 14 August 1829, stating the intention of the new College:[17]

...for the general education of youth in which the various branches of Literature and Science are intended to be taught, and also the doctrines and duties of Christianity... inculcated by the United Church of England and Ireland.

— Royal charter incorporating King's College, 14 August 1829.

The government of the College was vested in a council consisting of nine official governors, five of whom were clergymen, eight life governors, a treasurer, and 24 other members of the Corporation.[17] Several potential sites for the College were discussed including Buckingham Palace and Regent's Park,[23] however eventually the Treasury provided a site between the Strand and the Thames, running parallel to the yet unfinished Somerset House at a peppercorn rent in perpetuity.[27][28]

Duel in Battersea Fields, 21 March 1829

The Duke of Wellington's simultaneous support for an Anglican King's College and the Roman Catholic Relief Act, which was to lead to the granting of almost full civil rights to Catholics, was challenged by George Finch-Hatton, 10th Earl of Winchilsea, in early 1829. Winchilsea, and his supporters, wished for King’s to be subject to the Test Acts like the universities of Oxford and Cambridge where only members of the Church of England could matriculate,[29] but this was not Wellington’s intent.[30]

Winchilsea and about 150 other contributors withdrew their support of the new College in response to Wellington's support of Catholic emancipation. Accusations against Wellington were published in a letter to the Standard on 14 March where Winchilsea charged the Prime Minister with insincerity in his support for the new College.[31][32] In a letter to Wellington he wrote, "I have come to view the College as an instrument in a wider programme designed to promote the Roman Catholic faith and undermine the established church." Winchilsea also accused the Duke to have in mind "insidious designs for the infringement of our liberty and the introduction of Popery into every department of the State".[33]

The letter provoked a furious exchange of correspondence and Wellington accused Winchilsea of imputing him with "disgraceful and criminal motives" in setting up King's College and when Winchilsea refused to retract the remarks, Wellington - by his own admission, "no advocate of duelling" and a virgin duellist - demanded satisfaction in a contest of arms: "I now call upon your lordship to give me that satisfaction for your conduct which a gentleman has a right to require, and which a gentleman never refuses to give."[32]

The result was a duel in Battersea Fields on 21 March 1829.[18][34] Winchilsea did not fire, a plan he and his second almost certainly decided upon before the duel; Wellington took aim and fired wide to the right. Accounts differ as to whether Wellington missed on purpose. Wellington, noted for his poor aim, claimed he did, other reports more sympathetic to Winchilsea claimed he had aimed to kill.[35] Honour was saved and Winchilsea wrote Wellington an apology.[33] "Duel Day" is still celebrated on the first Thursday after 21 March every year, marked by various events throughout the College, including reenactments.[34][36]

19th century

King's opened in October 1831 with William Otter, a clergyman, appointed as first Principal and lecturer in divinity.[17] Despite the intentions of its founders and the chapel at the heart of its buildings, the initial prospectus permitted, "nonconformists of all sorts to enter the college freely".[37] William Howley, the Archbishop of Canterbury presided over the opening ceremony in which a sermon was given in the chapel by Charles Blomfield, the Bishop of London on the subject of combining religious instruction with intellectual culture. The governors and the professors, except the linguists, had to be members of the Church of England but the students did not,[38] though attendance at Chapel was compulsory.[39]

The College was divided into a Senior department and a Junior department, also known as King's College School, which was originally situated in the basement of the Strand Campus.[17] The Junior department started with 85 pupils and only three teachers, but quickly grew to 500 by 1841, outgrowing its facilities and leading it to relocate to Wimbledon in 1897 where it remains today, though it is no longer associated with the College.[38] Within the Senior department teaching was divided into three courses. A general course comprised divinity, classical languages, mathematics, English literature and history. Secondly, there was the medical course. Thirdly, miscellaneous subjects, such as law, political economy and modern languages, which were not related to any systematic course of study at the time and depended for their continuance on the supply of occasional students.[17] In 1833 the general course was reorganised leading to the award of the Associate of King's College (A.K.C.), the first qualification issued by King's.[17] The course, which concerns questions of ethics and theology, is still awarded today to students and staff who take an optional three year course alongside their studies.

The river frontage was completed in April 1835 at a cost of £7,100,[40] its completion a condition of the College securing the site from the Crown.[17] Unlike those in the school, student numbers in the Senior department remained almost stationary during the first five years of the College's existence. During this time the medical school was blighted by inefficiency and the divided loyalties of the staff leading to a steady decline in attendance. One of the most important appointments was that of Charles Wheatstone as professor of Experimental Philosophy.[17]

At this time, neither King's, nor "London University" had the ability to confer degrees, a particular problem for medical students who wished to practise. Amending this situation was aided by the appointment of Henry Brougham, as Lord Chancellor, who was chairman of the governors of "London University". In this position he automatically became a governor of King's. In the understanding that the government was unlikely to grant degree-awarding powers on two institutions in London, negotiations led to the colleges federating as the "University of London" in 1836, "London University" thus becoming University College.[21] The governors at King's were offended at the exclusion of divinity from the syllabus by the federal university which was founded as an examining body and advised students to take the Oxford or Cambridge examinations, however, the power of the university to confer degrees marked a period of limited expansion at the College.[17][38]

In 1840 the College opened King's College Hospital on Portugal Street near Lincoln's Inn Fields, an area composed of overcrowded rookeries characterised by poverty and disease. The governance of the hospital was later transferred to the corporation of the hospital established by the King's College Hospital Act 1851, and eventually moved to new premises in Denmark Hill, Camberwell in 1913. The appointment in 1877 of Joseph Lister as professor of clinical surgery greatly benefited the medical school, and the introduction of Lister's antiseptic surgical methods gained the hospital an international reputation.[17] In 1855 the College pioneered evening classes in London.[38] In 1882 the King's College London Act amended the constitution, the objects of the College extended to include the education of women.[17]

20th century

See also Contribution of King's College London to the discovery of the structure of DNA and Photo 51

The King's College London Act 1903, abolished all remaining religious tests for staff, except within the Theological department. The end of the First World War saw an influx of students, which strained existing facilities to the point where some classes were held in the Principal's house.[17] A government proposal to relocate the College premises to Bloomsbury was considered, but finally rejected in 1925.[41] During the Second World War most students and staff were evacuated out of London to Bristol and Glasgow.[17][42] The College buildings were used by the Auxiliary Fire Service with a number of College staff, mainly those then known as College servants, serving as firewatchers. Parts of the Strand building, the quadrangle, and the roof of apse and stained glass windows of the chapel suffered bomb damage in the Blitz.[43][44] During reconstruction, the vaults beneath the quadrangle were replaced by a two-storey laboratory, which opened in 1952, for the departments of Physics and Civil and Electrical Engineering.[17]

One of the most famous pieces of scientific research performed at King's were the crucial contributions to the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA in 1953 by Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin, together with Raymond Gosling, Alex Stokes, Herbert Wilson and other colleagues at the Randall Division of Cell and Molecular Biophysics at King's.[45][46][47]

Major reconstruction of the College began in 1966 following the publication of the Robbins Report on Higher Education. A new block facing the Strand designed by E. D. Jefferiss Mathews was opened in 1972.[38] The College underwent several mergers with other institutions, including Queen Elizabeth College and Chelsea College of Science and Technology in 1985, the Institute of Psychiatry in 1997, and the United Medical and Dental Schools of Guy's and St Thomas' Hospitals were reincorporated in 1998 after becoming independent of the College at the foundation of the National Health Service in 1948.[38][48] In 1998 Florence Nightingale's original training school for nurses merged with the King's Department of Nursing Studies as the Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery. The same year the College acquired the former Public Records Office building on Chancery Lane and converted it at a cost of £35 million into the Maughan Library, which opened in 2002.[38]

2001 to present

In 2003, the College was granted degree-awarding powers in its own right, as opposed to through the University of London, by the Privy Council. This power remained unexercised until 2007, when the College announced that all students starting courses from September 2007 onwards would be awarded degrees conferred by King's itself, rather than by the University of London. The new certificates however still make reference to the fact that King's is a constituent college of the University of London.[49] All current students with at least one year of study remaining were in August 2007 offered the option of choosing to be awarded a University of London degree or a King's degree. In 2007, for the second consecutive year, students from the School of Law won the national round of the Philip C. Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition. The Jessup moot is the largest international mooting competition in the world. The King's team went on to represent the UK as national champions.[50]

In 2010 the College announced that 205 jobs were put at risk in response to government funding cuts.[51][52] Among the proposed cuts was the UK's only chair of palaeography, two leading computational linguists, and the department of Engineering, believed to be the oldest in the UK (established in 1838), sparking an international campaign from academics.[51][53]

In November, 2010, King's launched a fundraising campaign to raise £500 million by 2015 for research into five areas: cancer, global power, neuroscience and mental health, leadership and society and children's health.[54] Over £400 million has been raised as of March 2013.[55] In 2011 the Chemistry department was reopened following its closure in 2003.[56]

In April 2011 King’s became a partner in the UK Centre for Medical Research and Innovation, subsequently renamed the Francis Crick Institute, committing £40 million to the project.[57]

In March 2013, Rick Trainor announced that he would step down as Principal of King’s in October 2014, after serving for ten years.[55]

Campus

Strand Campus

The Strand Campus is the founding campus of King's. It is located on the Strand in the City of Westminster, sharing its frontage along the River Thames. Most of the Schools of Arts & Humanities, Law, Social Science & Public Policy and Natural & Mathematical Sciences (formerly Physical Sciences & Engineering) are housed here. The campus combines the Grade I listed King's Building of 1831 designed by Sir Robert Smirke, and the Byzantine Gothic College Chapel, redesigned in 1864 by Sir George Gilbert Scott with the more modern Strand Building, completed in 1972. The Chesham Building in Surrey Street was purchased after the Second World War. The Macadam Building of 1975 houses the Strand Campus Students' Union centre and is named after King's alumnus Sir Ivison Macadam, first President of the National Union of Students.

Marble statues of Sappho and Sophocles were bequeathed by Frida Mond in 1923, a friend of Israel Gollancz, Professor of English Language and Literature at King's. They were placed in the lobby of the King's Building, where they have remained ever since.[58]

Chapel

The original college chapel was designed by Sir Robert Smirke and was completed in 1831 as part of the College building (later known as the King's building).[59] Given the foundation of the university in the tradition of the Church of England the chapel was intended to be an integral part of the campus.[60] This is reflected in its central location within the King's Building on the first floor above the Great Hall, accessible via a grand double staircase from the foyer. The original chapel was described as a low and broad room "fitted to the ecclesiological notions of George IV’s reign."[60] However, by the mid nineteenth century its style had fallen out of fashion and in 1859 a proposal by the College Chaplain Reverend E. H. Plumptre that the original chapel should be reconstructed was approved by the College Council, who agreed that its "meagreness and poverty" made it unworthy of King’s.[59]

The College approached Sir George Gilbert Scott to make proposals. In his proposal of 22 December 1859 he suggested that, "There can be no doubt that, in a classic building, the best mode of giving ecclesiastical character is the adoption of the form and, in some degree, the character of an ancient basilica."[59] His proposals for a chapel modelled on the lines of an classical basilica were accepted and the reconstruction was completed in 1864 at a cost of just over £7,000.[59]

Somerset House East Wing

In December 2009, the College signed a 78 year lease to the East Wing of Somerset House.[61] It has been described as one of the longest-ever property negotiations, taking over 180 years to complete.[62] Since the College was built it has been in various discussions to expand into one of the wings of Somerset House itself, however, the relationship between the College and HM Revenue and Customs that occupied the East Wing were sometimes difficult.[63][64][65] Sir Robert Smirke's design of King's was sympathetic to that of Somerset House which is situated adjacent to the Strand Campus.[66] Indeed, a condition of the College acquiring the site in the 1820s was that it should be erected "on a plan which would complete the river front of Somerset House at its eastern extremity in accordance with the original design of Sir William Chambers" which had for so long offended "every eye of taste for its incomplete appearance".[64][65]

In 1875, a dispute arose when new windows were added to the façade overlooking the College. Following a complaint by the College Council at the loss of privacy, the response of the Metropolitan Board of Works was that "the terms under which the college is held are not such as to enable the Council to restrict Her Majesty from opening windows in Somerset House whenever she may think proper".[63] By the end of World War I the College began to outgrow its premises which led to rekindled efforts to acquire the East Wing. There was even a suggestion that the College should be relocated to new premises in Bloomsbury to alleviate space concerns, however, these plans never came to fruition. Instead, a new top floor was added to the King's Building to house the Anatomy Department and other buildings along Surrey Street were purchased.[63]

Following the publication of the Robbins Report on Higher Education in 1963 a further attempt was made to acquire the East Wing. The Report recommended a large expansion in student numbers accommodated by a new building programme. The "quadrilateral plan" was to create a campus stretching from Norfolk Street in the east to Waterloo Bridge Road in the west. Plans were also drawn up for modern high-rise buildings along the Strand and Surrey Street to house a new library and laboratories. A contemporary report stated that the redevelopment would provide "London with a university precinct on the Strand of which the capital could be proud".[63] The plans were revisited in the early 1970s by the then Principal, Sir John Hackett, however, progress was prevented by funding problems and the unwillingness of the Government to re-house its civil servants.[63] In 1971 the Evening Standard led a public campaign for Somerset House to be transformed into a new public arts venue for London. Proposals were also aired for the relocation of the Tate Gallery to the site.[63] In the 1990s the eventual vacation by government departments and a comprehensive restoration programme saw the opening of the Courtauld Gallery, the Gilbert and Hermitage collections and the Edmond J. Safra Fountain Court.[63][65]

In early 2010 a £25 million renovation of the East Wing was undertaken and took 18 months to complete. On 29 February 2012, Queen Elizabeth II officially opened the building.[62] It is home to the School of Law, a public exhibition space called the Inigo Rooms curated by the King's Cultural Institute as well as adding a further entrance to the Strand Campus.[67]

Strand Lane 'Roman bath'

There was an old Roman bath in those days at the bottom of one of the streets out of the Strand—it may be there still—in which I have had many a cold plunge. Dressing myself as quietly as I could, and leaving Peggotty to look after my aunt, I tumbled head foremost into it, and then went for a walk to Hampstead.

— Extract from Chapter 35, David Copperfield by Charles Dickens[68]

A Stuart cistern and later eighteenth century public bath protected by the National Trust[69] and popularly known as the 'Roman bath' is situated on the site of the Strand Campus beneath the Norfolk Building and can be accessed via the Surrey Street entrance.[70] Hidden by surrounding College buildings, the bath was widely thought to be of Roman origin giving its popular name, however it is more likely that it was originally a cistern for a fountain built in the gardens of Somerset House for Queen Anne of Denmark in 1612.[71] Evidence of its first use as a public bath was in the late eighteenth century.[71] The 'Roman bath' is mentioned by Charles Dickens in chapters thirty-five and thirty-six of the novel David Copperfield.[72]

Moreover Aldwych tube station, a well-preserved but disused London Underground station, is integrated as part of the campus. A rifle range used by the College is located on the site of one of the platforms since the closure of the station in 1994.[73][74]

The nearest Underground stations are Temple, Charing Cross and Covent Garden.

Guy's Campus

Guy's Campus is situated close to London Bridge and the Shard on the South Bank of the Thames and is home to the School of Biomedical Sciences (also at the Waterloo Campus), the Dental Institute, and the School of Medicine.[75]

Thomas Guy, the founder and benefactor of Guy's Hospital established in 1726 in the London Borough of Southwark, was a wealthy bookseller and also a governor of the nearby St Thomas' Hospital. He lies buried in the vault beneath the eighteenth century chapel at Guy's. Silk-merchant William Hunt was a later benefactor who gave money in the early nineteenth century to build Hunt's House. Today this is the site of New Hunt's House. The Henriette Raphael building, constructed in 1903, and the Gordon Museum are also located here. In addition, the Hodgkin building, Shepherd's House and Guy's chapel are prominent buildings within the campus. The Students' Union centre at Guy's is situated in Boland House.

The nearest Underground stations are London Bridge and Borough.

Waterloo Campus

The Waterloo Campus is located across Waterloo Bridge from the Strand Campus, near the South Bank Centre in the London Borough of Lambeth and consists of the James Clerk Maxwell Building and the Franklin-Wilkins Building.

Cornwall House, now the Franklin-Wilkins Building, constructed between 1912 and 1915 was originally the His Majesty's Stationery Office (responsible for Crown copyright and National Archives), but was requisitioned for use as a military hospital in 1915 during World War I. It became the King George Military Hospital, and accommodated about 1,800 patients on 63 wards.[76] The College acquired the building in the 1980s and today it is home to the School of Biomedical Sciences (also at the Guy's Campus), parts of the School of Social Science & Public Policy (also at the Strand Campus) and LonDEC (London Dental Education Centre), part of the Dental Institute (also at Guy's and Denmark Hill). The building, one of London's largest university buildings, underwent refurbishment and was reopened in 2000. The building is named after Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins for their major contributions to the discovery of the structure of DNA.[77]

The James Clerk Maxwell Building houses the Principal's Office, most of the central administrative offices of the College and part of the Florence Nightingale School of Nursing & Midwifery.

The nearest Underground station is Waterloo.

St Thomas' Campus

The St Thomas' Campus in the London Borough of Lambeth, facing the Houses of Parliament across the Thames, houses parts of the School of Medicine and the Dental Institute. The Florence Nightingale Museum is also located here.[78] St Thomas' Hospital became part of King's College London School of Medicine in 1998. The Department of Twin Research (TwinsUk), King's College London is located in St. Thomas' Hospital.

The nearest Underground station is Westminster.

Denmark Hill Campus

Denmark Hill Campus is situated in south London near the borders of the London Borough of Lambeth and the London Borough of Southwark in Camberwell and is the only campus not situated on the River Thames. The campus consists of King's College Hospital, the Maudsley Hospital and the Institute of Psychiatry (IoP). In addition to the Institute of Psychiatry, parts of the Dental Institute and School of Medicine, and a large hall of residence, King's College Hall, are situated here. Other buildings include the campus library known as the Weston Education Centre (WEC), the James Black Centre, the Rayne Institute (haemato-oncology) and the Cicely Saunders Institute (palliative care).[79]

The nearest Overground station is Denmark Hill.

Refurbishment

King's is currently undergoing a £1 billion redevelopment programme of its estates.[80] Since 1999 over half of the College's activities have been relocated in new and refurbished buildings.[81] Major completed projects include a £35 million renovation of the Maughan Library in 2002, a £40 million renovation of buildings at the Strand Campus, a £25 million renovation of Somerset House East Wing, a £30 million renovation of the Denmark Hill Campus in 2007, the renovation of the Franklin-Wilkins Library at the Waterloo Campus and the completion of the £9 million Cicely Saunders Institute of Palliative Care in 2010.[82] The College chapel at the Strand Campus was also restored in 2001.[59]

The Strand Campus redevelopment won the Green Gown Award in 2007 for sustainable construction. The award recognised the "reduced energy and carbon emissions from a sustainable refurbishment of the historic South Range of the King's Building".[83] King's was also the recipient of the 2003 City Heritage Award for the conversion of the Grade II* listed Maughan Library.[84]

Current projects include a £45 million development for the Maurice Wohl Clinical Neuroscience Institute, £18 million on modernising the College's learning and teaching environments, a sports pavilion at Honor Oak Park.[85] In April 2012 a £20 million redevelopment of the Strand Campus Quad was announced and will provide an additional 3,700 square metres of teaching space and student facilities.[86]

Organisation and administration

Governance

The College's formal head is the Principal, currently held by Sir Rick Trainor.[87] The office is established by the Charter of the College as "the chief academic and administrative officer of the College" and the College Statutes require the Principal to have the general responsibility to the Council for "ensuring that the objects of the College are fulfilled and for maintaining and promoting the efficiency, discipline and good order of the College".[88] The current Chairman of the Council is Lord Duoro.[89]

Senior officers are called the Principal's Central Team. Six Vice-Principals have specific responsibilities for Education; Research and Innovation; Strategy and Development; Arts and Sciences; International (developing the College’s global research networks); and Health (where there is also a Deputy Vice-Principal).

The Council is the supreme governing body of the College established under the Charter and Statutes, comprising 21 members. Its membership include the President of KCLSU (as the student member), the Principal and President, up to seven other staff members, and up to 12 lay members who must not be employees of the College.[90] It is supported by a number of standing committees.[91]

The Dean of King's College is an ordained person, which is unusual among British universities.[92] The Dean is "responsible for overseeing the spiritual development and welfare of all students and staff". The Office of the Dean coordinate the Associateship of King's College programme, the Chaplaincy and the Chapel Choir, which includes 25 Choir scholarships.[92] One of the Dean's roles is to encourage and foster vocations to the Church of England priesthood.[93]

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the College Visitor by right of office owing to the role of the Church of England in the College's foundation.[94]

Schools and departments

King's is made up of nine academic schools, which are subdivided into departments, centres and research divisions:

-

- Arts & Humanities Research Institute

- Centre for Hellenic Studies

- Classics

- Comparative Literature

- Culture, Media & Creative Industries

- Digital Humanities

- English

- European & International Studies

- Film Studies

- French

- German

- History

- Institute of Contemporary British History

- Liberal Arts

- Modern Language Centre

- Music

- Philosophy

- Spanish, Portuguese & Latin American Studies

- Theology & Religious Studies

-

- Analytical & Environmental Sciences Division

- Centre for Human & Aerospace Physiological Sciences (CHAPS)

- Department of Chemistry

- Institute of Pharmaceutical Science

- MRC Centre for Developmental Neurobiology

- MRC-HPA Centre for Environment & Health

- Randall Division of Cell and Molecular Biophysics

- Wolfson Centre for Age-Related Diseases

-

- Asthma, Allergy & Lung Biology

- Cancer Studies

- Cardiovascular Division

- Cicely Saunders Institute of Palliative Care and Rehabilitation

- Diabetes & Nutritional Sciences

- Genetics & Molecular Medicine

- Health & Social Care Research

- Imaging Sciences & Biomedical Engineering

- Immunology, Infection & Inflammatory Disease

- Medical Education

- Transplantation Immunology & Mucosal Biology

- Women's Health

-

- Chemistry

- Engineering

- Informatics

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Institute of Telecommunications

-

- Defence Studies Department

- Education & Professional Studies

- Geography

- Gerontology

- King's Policy Institute

- Management

- Political Economy

- Social Science, Health & Medicine

- War Studies

-

- Centre of British Constitutional Law and History

- Centre of Construction Law

- Centre of European Law

- Centre of Medical Law and Ethics

- Centre for Technology, Ethics and Law in Society

- International State Crime Initiative

- KJuris: Jurisprudence at King's

- Trust Law Committee

Additionally, there are several global institutes with country-specific and regional focuses which offer postgraduate teaching, organise topical events, and make links between the university and cultural and political organisations:

-

- African Leadership Centre

- Brazil Institute

- Centre for Middle East & Mediterranean Studies

- India Institute

- Institute of North American Studies

- International Development Institute

- King's Centre for Global Health

- King's Cultural Institute

- Lau China Institute

- Russia Institute

The Department of War Studies is unique in the UK, and is supported by facilities such as the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives, the Centre for Defence Studies,[95] and the King's Centre for Military Health Research (KCMHR).[96]

The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) is administered through King's, and its students graduate alongside members of the departments which form the School of Arts & Humanities. As RADA does not have degree awarding powers, its courses are validated by King's.[97]

Academic year

King's academic year runs from the last Monday in September to the first Friday in June.[98]

Graduation ceremonies are held in June or July, with ceremonies held in Southwark Cathedral for the School of Medicine and the Dental Institute and in the Barbican Centre for all other Schools.[99] Since 2008 King's graduates have worn gowns designed by Vivienne Westwood.[100]

Finances

In the financial year ended 31 July 2012 King's had a total income of £554.22 million (2010/11 – £524.11 million) and total expenditure of £522.71 million (2010/11 – £496.61 million).[1] Key sources of income included £154.75 million from research grants and contracts (2010/11 – £147.1 million), £146.54 million from tuition fees and education contracts (2010/11 – £130.75 million), £140.91 million from Funding Council grants (2010/11 – £147.21 million) and £8.19 million from endowment and investment income (2010/11 – £5.49 million).[1] During the 2011/12 financial year King's had a capital expenditure of £61.39 million (2010/11 – £49.15 million).[1]

At 31 July 2012 King's had total endowments of £130.76 million (31 July 2011 – £124.67 million) and total net assets of £776.31 million (31 July 2011 – £726.87 million).[1] King's has a credit rating of AA from Standard & Poor's.[1]

In October 2010 King's launched a major fundraising campaign fronted by former British Prime Minister John Major, with a goal to raise £500 million by 2015.[101]

Coat of arms

The coat of arms displayed on the College Charter is that of George IV. The shield depicts the royal coat of arms together with an inescutcheon of the House of Hanover, while the supporters embody the College motto of sancte et sapienter. No correspondence is believed to have survived regarding the choice of this coat of arms, either in the College Archives or at the College of Arms, and a wide variety of unofficial adaptations have been used during the history of the College. The current coat of arms was developed following the mergers with Queen Elizabeth College and Chelsea College in 1985, and incorporates aspects of their heraldry. The College's coat of arms, in heraldic terminology, is:[102]

The arms:

Or on a Pale Azure between two Lions rampant respectant Gules an Anchor Gold ensigned by a Royal Crown proper on a Chief Argent an Ancient Lamp proper inflamed Gold between two Blazing Hearths also proper.

The crest and supporters:

On a Helm with a Wreath Or and Azure Upon a Book proper rising from a Coronet Or the rim set with jewels two Azure (one manifest) four Vert (two manifest) and two Gules a demi Lion Gules holding a Rod of Dexter a female figure habited Azure the cloak lined coif and sleeves Argent holding in the exterior hand a Lond Cross botony Gold and sinister a male figure the Long Coat Azure trimmed with Sable proper shirt Argent holding in the interior hand a Book proper.

Academics

Admissions

The Sunday Times has ranked King's as the 6th most difficult UK university to gain admission to.[103] According to the 2008 Times Good University Guide approximately 30% of King's undergraduates come from independent schools.[104]

At the undergraduate level admission to King's is extremely competitive. In 2011 some courses, such as English, Law and Business Management, had 15 or more applicants per place or an acceptance rate of less than 7.5 percent.[105]

Medicine

King's is the largest centre for healthcare education in Europe.[106] King's College London School of Medicine has over 2,000 undergraduate students, over 1,400 teachers, four main teaching hospitals – Guy's Hospital, King's College Hospital, St Thomas' Hospital and University Hospital Lewisham – and 17 associated district general hospitals.[107] King’s College London Dental Institute is the largest dental school in Europe.[108] The Florence Nightingale School of Nursing & Midwifery is the oldest professional school of nursing in the world.[109]

King's is a major centre for biomedical research. It is a founding member of King's Health Partners, one of the largest academic health sciences centres in Europe with a turnover of over £2 billion and approximately 25,000 employees.[106] It also is home to six Medical Research Council centres, the most of any British university,[110] and is part of two of the twelve biomedical research centres established by the NHS in England – the Guy's & St Thomas'/King's College London Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre and the South London and Maudsley/KCL Institute of Psychiatry Biomedical Research Centre.[111]

The Drug Control Centre at King's was established in 1978 and is the only WADA accredited anti-doping laboratory in the UK and holds the official UK contract for running doping tests on UK athletes.[112] In 1997, it became the first International Olympic Committee accredited laboratory to meet the ISO/IEC 17025 quality standard.[113] The Centre was the anti-doping facility for the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games.[114]

Libraries

King's library facilities are spread across its five campuses. The College's estate also includes the library at Bethlem Royal Hospital in the London Borough of Bromley.[115] The collections encompass over one million printed books, as well as thousands of journals and electronic resources.

Maughan Library

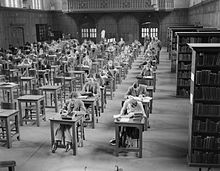

The Maughan Library is King's largest library and is housed in the Grade II* listed 19th century gothic former Public Record Office building situated on Chancery Lane near the Strand Campus. The building was designed by Sir James Pennethorne and is home to the books and journals of the Schools of Arts & Humanities, Law, Natural & Mathematical Sciences, and Social Science & Public Policy. It also houses the Special Collections and rare books. Inside the Library is the octagonal Round Reading Room, inspired by the reading room of the British Museum, and the former Rolls Chapel (renamed the Weston Room following a donation from the Garfield Weston Foundation) with its stained glass windows, mosaic floor and monuments, including an important Renaissance terracotta figure by Pietro Torrigiano of Dr Yonge, Master of the Rolls, who died in 1516.

Other libraries

- The Foyle Special Collections Library at Chancery Lane houses a collection of over 150,000 printed works as well as thousands of maps, slides, sound recordings and some manuscript material.[116]

- The Tony Arnold Library at Chancery Lane houses a collection of over 3000 law books and 140 law journals. It was named after Tony Arnold, the longest serving Secretary of the Institute of Taxation. In September 2001 the library became part of the law collection of King's College London.[117]

- The Franklin-Wilkins Library at the Waterloo Campus is home to extensive management and education holdings, as well as wide-ranging biomedical, health and life sciences coverage includes nursing, midwifery, public health, pharmacy, biological and environmental sciences, biochemistry and forensic science.[118]

- The New Hunt's House Library at Guy's Campus covers all aspects of biomedical science. There are also extensive resources for medicine, dentistry, physiotherapy and health services.[119]

- The Weston Education Centre Library at the Denmark Hill Campus has particular strengths in the areas of gastroenterology, liver disease, diabetes, obstetrics, gynaecology, paediatrics and the history of medicine.[120]

- The St Thomas' House Library holdings cover all aspects of basic medical sciences, clinical medicine and health services research.[121]

- The Institute of Psychiatry (IoP) Library is the largest psychiatric library in Western Europe, holding 3,000 print journal titles, 550 of which are current subscriptions, as well as access to over 3,500 electronic journals, 38,000 books, and training materials.[122]

- The Bethlem Royal Hospital Library contains a smaller collection to support students and staff working at the hospital.[123]

Rankings

| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2025)[124] | 19 |

| Guardian (2025)[125] | 32 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2024)[126] | 68 |

| QS (2025)[127] | 26 |

| THE (2025)[128] | 56 |

Internationally, King's is consistently ranked among the top 100 universities in the world by all major global university rankings compilers, having been placed between 27th by the 2011 QS World University Rankings[129] and 56th worldwide by the Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[130]

According to the 2009 Times Good University Guide, several subjects taught at King’s including Law, History, European Studies and War Studies (both categorised under politics), Classics, Spanish, Portuguese, Music, Dentistry, Medicine, Nursing and Food Science are among the top five in the country.[131]

According to the 2010 Complete University guide, many subjects at King's including Classics, English, French, Geography, German, History, Music, Philosophy and Theology, rank within the top 10 nationally. The College has had 24 of its subject-areas awarded the highest rating of 5 or 5* for research quality,[132] and in 2007 it received a good result in its audit by the Quality Assurance Agency.[132] It is in the top tier for research earnings. In September 2010, the Sunday Times selected King's as the "University of the Year 2010-11".[133]

Fellows

See Category:Fellows of King's College London

The Fellowship of King's College London (FKC) is the most prestigious award the College can bestow. The award of the Fellowship is governed by a statute of the College and reflects distinguished service to the College by a member of staff, conspicuous service to the College, or the achievement of distinction by those who were at one time closely associated with the College.[134]

Student life

King's College London Students' Union

Founded in 1873, King's College London Union Society which later developed into King's College London Students' Union, better known by its acronym KCLSU, is the oldest Students' Union in London (University College London Union being founded in 1893)[135] and has a claim to being the oldest Students' Union in England.[136][137] The Students' Union provides a wide range of activities and services, including over 50 sports clubs (which includes the Boat Club which rows on the River Thames and the Rifle Club which uses the College's shooting range located at the disused Aldwych tube station beneath the Strand Campus),[138] over 200 activity groups,[139] a wide range of volunteering opportunities, two bars/eateries (The Waterfront and Guy's Bar), one nightclub (Tutu's, named after alumnus Desmond Tutu), a shop (King's Shop) and a gym (Kinetic Fitness Club).

The former President of KCLSU Sir Ivison Macadam, after whom the Students' Union building on the Strand Campus has since been named, went on to be elected as the first President of the National Union of Students, and KCLSU has played an active role there and in the University of London Union ever since.

KCLSU publishes a monthly newspaper called Roar! which carries news stories, reviews and features on a range of topics and reporting on Students' Union events, campaigns, clubs and societies, as well as coverage of the arts, books and fashion.

Reggie the Lion (informally Reggie) is the official mascot of the Students' Union. In total there are three Reggies in existence. The original can be found on display in the Macadam Building in the Students' Union student centre at the Strand Campus. A papier-mâché Reggie lives outside the Great Hall at the Strand Campus and a small sterling silver incarnation is displayed during graduation ceremonies.

Sports

There are over 50 sports clubs, many of which compete in the University of London and British Universities & Colleges (BUCS) leagues across the South East.[138] The annual Macadam Cup is a varsity match played between the sports teams of King's College London proper (KCL) and King's College London Medical School (KCLMS).

Student-led think tank

In November 2011, KCL students founded London's first student-led think tank, the KCL Think Tank. With a membership of around 2000, it is the largest organisation of its kind in Europe.[140] This student initiative organises lectures and discussions in seven different policy areas, and assists students in lobbying politicians, NGOs and other policymakers with their ideas. Every September, it produces a peer-reviewed journal of policy recommendations called The Spectrum.[141][142]

Rivalry with University College London

Competition within the University of London is most intense between King's and University College London, the two oldest institutions. Indeed, the University of London when it was established has been described as "an umbrella organisation designed to disguise the rivalry between UCL and KCL."[143] In the early twentieth century, King's College London and UCL rivalry was centred on their respective mascots.[144] University College's was Phineas Maclino, a wooden tobacconist's sign of a kilted Jacobite Highlander purloined from outside a shop in Tottenham Court Road during the celebrations of the relief of Ladysmith in 1900. King's later addition was a giant beer bottle representing "bottled youth". In 1923 it was replaced by a new mascot to rival Phineas – Reggie the Lion, who made his debut at a King's-UCL sporting rag in December 1923, protected by a lifeguard of engineering students armed with T-squares. Thereafter, Reggie formed the centrepiece of annual freshers' processions by King's students around Aldwych in which new students were typically flour bombed.

Although riots between respective College students occurred in central London well into the 1950s, rivalry is now limited to the rugby union pitch and skulduggery over mascots, with an annual Varsity match taking place between King's College London RFC and University College London RFC.[144][145]

Rivalry with the London School of Economics

On 2 December 2005, tensions between King's and the London School of Economics (LSE) were ignited when at least 200 students from LSE (located in Aldwych near the Strand Campus) diverted off from the annual "barrel run" and caused an estimated £32,000 (The Beaver, LSESU student newspaper, 26 September 2006) of damage to the English department at King's.[146] Principal Sir Rick Trainor called for no retaliation and LSE Students' Union were forced to issue an apology as well as foot the bill for the damage repair. While LSE officially condemned the action, a photograph was published in The Beaver which was later picked up by The Times that showed LSE Director Sir Howard Davies drinking with members of the LSE Students' Union shortly before the barrel run and subsequent "rampage" began. King's appears to have been targeted, however, principally owing to its close proximity to LSE rather than by any ill-feeling. There is also somewhat of a sporting rivalry between the two institutions, albeit to a lesser extent than with UCL.

College prayer

A College prayer is said in morning prayer each weekday in Chapel to pray for the life of the College.[147]

The College Prayer

- ALMIGHTY God, the Fountain of Wisdom

- and the Giver of every perfect gift;

- without whom nothing is strong, nothing is holy;

- Send down, we beseech you, your blessing upon this College,

- and prosper the designs of its founders and benefactors.

- Enable us, by your grace,

- faithfully to discharge the duties of our several stations,

- remembering the strict and solemn account

- which we must one day give

- before the judgement-seat of Christ.

- More particularly we pray, that the seeds of Learning, Virtue and Religion, here sown, may bring forth fruit abundantly to your glory and the benefit of our fellow creatures.

- These and all other blessings, for them and for us, we humbly ask in the name and through the mediation

- of Jesus Christ your Son our Lord. Amen.

Student residences

Halls of residence

King's has a total of eight halls of residence located throughout London. Priority is given to students whose home address is outside the M25 motorway.[148]

Self-catered:

- Brian Creamer House at St Thomas' Campus

- Great Dover Street Apartments at Guy's Campus

- Hampstead Residence in Hampstead

- Moonraker Point in Southwark (nominated residence run by Unite Group)

- Stamford Street Apartments at the Waterloo Campus

- The Rectory at St Thomas' Campus

- Wolfson House at Guy's Campus

Catered:

- King's College Hall at the Denmark Hill Campus (currently closed for refurbishment)

Intercollegiate halls of residence

In addition to halls of residence run by King's, full-time students are eligible to stay at one of the Intercollegiate Halls of Residence offered by the University of London. King's has the largest number of bedspaces in the University of London Intercollegiate Halls.[149] The halls are:

- Canterbury Hall,[150] College Hall,[151] Commonwealth Hall,[150] Connaught Hall,[152] Hughes Parry Hall[150] and International Hall[153] near Russell Square in Bloomsbury

- Lillian Penson Hall (postgraduates only) in Paddington[154]

- Nutford House in Marble Arch[155]

Additionally, students can apply to live in International Students House.

Notable people

Notable alumni

King's has educated numerous foreign Heads of State and Government including Tassos Papadopoulos, president of Cyprus from 2003 to 2008 who graduated from King's with a degree in Law in 1955,[156] and his predecessor Glafkos Klerides who served as president of Cyprus from 1993 to 2003 and graduated with a Law degree in 1948.[157] Former Prime Minister of Jordan, Marouf al-Bakhit, graduated from King's with a PhD in War Studies in 1990,[158] France-Albert René president of the Seychelles from 1977 to 2004 studied Law at King's,[159] Sir Lynden Pindling prime minister of the Bahamas from 1967 to 1992 graduated with a Law degree in 1952,[160] Godfrey Binaisa president of Uganda from 1979 to 1980 graduated with a Law degree in 1955,[161] Abd ar-Rahman al-Bazzaz prime minister of Iraq from 1965 to 1966 graduated from King's,[162] Sir Lee Moore, prime minister of Saint Kitts and Nevis from 1979 to 1980, graduated with a degree in Law and Theology,[163] Martin Bourke Governor of the Turks and Caicos Islands from 1993 to 1996 graduated with an MA from King's,[164] and Sir Shridath Ramphal, former Secretary General of the Commonwealth, graduated with a Law degree in 1952.[165] Sarojini Naidu, the first woman President of the Indian National Congress and an architect of the Indian freedom movement, also studied at King's, while Prince Eugene Louis Napoléon, the ill-fated scion of the Bonaparte Dynasty, studied physics and mathematics from 1871 to 1872.[166][167][168] There are currently two King's alumni serving as Permanent Representatives to the United Nations, Lois Young of Belize, and Shekou Touray of Sierra Leone.

Notable King's alumni to have held senior positions in British and Irish politics include the British Foreign Secretary David Owen, Baron Owen, two Speakers of the House of Commons in Horace King, Baron Maybray-King (English) and James Lowther, 1st Viscount Ullswater, Leader of the House of Commons John MacGregor, Baron MacGregor of Pulham Market (Law, 1962), and Irish Republican & revolutionary leader Michael Collins. As of the current Parliament there are 17 King's graduates in the House of Commons, and 15 King's graduates in the House of Lords.

In Law, King's alumni include the Senior President of Tribunals Sir Jeremy Sullivan (Law, 1967);[169] High Court judge Sir David Foskett (Law, 1970);[170] former Judge of the International Court of Justice, Abdul Koroma (International Law, 1976);[171]; the current Chief Justice of Western Australia Wayne Martin (Law, 1975) and Fielding Clarke, Chief Justice of Fiji, Hong Kong and Jamaica in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

King's alumni in religion include the Nobel Peace Prize laureate and Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town Desmond Tutu (Theology, 1966),[172] former Archbishop of Canterbury George Carey, Baron Carey of Clifton (Theology, 1962),[173] Head of the Church of Ireland Richard Clarke, and the current Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth Jonathan Sacks, Baron Sacks (Theology & Religious Studies, 1981).[174]

Notable King's alumni in poetry and literature include the poet John Keats (Medicine), and the writers Thomas Hardy (French), Sir Arthur C. Clarke (Mathematics & Physics), W. Somerset Maugham, Alain de Botton (Philosophy), C.S. Forester, B. S. Johnson (English), Charles Kingsley, Virginia Woolf, John Ruskin, Radclyffe Hall, Susan Hill, Hanif Kureishi (Philosophy), Anita Brookner (History), Michael Morpurgo (French & English), Sir Leslie Stephen, Maureen Duffy and Helen Cresswell. In addition, the dramatist Sir W. S. Gilbert of Gilbert and Sullivan graduated from King's.

King's alumni in the sciences include Nobel laureates Max Theiler and Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins;[14][175] polymath Sir Francis Galton; pathologist Thomas Hodgkin; pioneer of in vitro fertilization Patrick Steptoe; botanist David Bellamy;[176] and the noted theoretical physicist Peter Higgs.[177]

King's is also the alma mater of the founder of Bentley Motors, Walter Bentley; satirist Rory Bremner (Modern Languages, 1984);,[178] Hollywood actress Greer Garson (BA in French, 1923),[179] journalist Martin Bashir (Religious History, 1985);[180] Queen bassist John Deacon;[178] current head of the Royal Marines Ed Davis, and the former head of the British Army Lord Harding.

Heads of state and government

| State | Leader | Office | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sir Lynden Pindling | Premier 1967–1969; Prime Minister 1969–1992 | ||

| Tassos Papadopoulos | President 2003–2008 | ||

| Glafcos Clerides | Acting President 1974; President 1993–2003 | ||

| Lord Harding | Governor 1955–1957 | ||

| Napoléon, Prince Imperial | Emperor of the French (titular) 1873-1879 | ||

| Abd ar-Rahman al-Bazzaz | Temporary President 1966; Prime Minister 1965–1966 | ||

| Michael Collins | Chairman of the Provisional Government 1922 | ||

| Marouf al-Bakhit | Prime Minister 2005–2007; 2011 | ||

| Sir Lee Moore | Premier 1979–1980 | ||

| Sir Sydney Gun-Munro | Governor 1976–1979; Governor-General 1979–1985 | ||

| France-Albert René | Prime Minister 1976–1977; President 1977–2004 | ||

| Lord Milner | Governor of Cape Colony 1897–1901 | ||

| Martin Bourke | Governor 1993–1996 | ||

| Godfrey Binaisa | President 1979–1981 |

Notable faculty and staff

See also Category:Academics of King's College London

King's has benefited from the services of academics at the top of their fields, including:

Nobel laureates

There are 10 Nobel laureates who were either students or academics at King's.[14]

| Name | Prize | Year Awarded | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charles Barkla | Physics | For the discovery of X-ray fluorescence | |

| Sir Owen Richardson | Physics | For pioneering the study of thermionics | |

| Sir Frederick Hopkins | Physiology or Medicine | For research on vitamins and beriberi | |

| Sir Charles Sherrington | Physiology or Medicine | For research on the nervous system | |

| Sir Edward Appleton | Physics | For exploration of the ionosophere | |

| Max Theiler | Physiology or Medicine | For developing a vaccine for yellow fever | |

| Maurice Wilkins | Physiology or Medicine | For the discovery of the structure of DNA | |

| Desmond Tutu | Peace | For his unifying role in the campaign against apartheid | |

| Sir James Black | Physiology or Medicine | For the development of beta-blocker and anti-ulcer drugs | |

| Mario Vargas Llosa | Literature | For his trenchant images of resistance, revolt, and defeat |

In popular culture

In the Sherlock Holmes story The Adventure of the Resident Patient, Dr Percy Trevelyan describes himself as a "London University man" who joined King's College Hospital after graduating.

In the Sherlock episode "The Blind Banker", King's College London can be seen listed in Watson's curriculum vitae.

King's Department of Theology's library plays a widely fictionalized part in Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code.

In Philip Roth's novel The Professor of Desire, the main character David Kepesh spent a certain period of time studying comparative literature at the College on a Fulbright Scholarship.

The Neo-Classical facade of the College, with the passage which connects the Strand to Somerset House terrace has been utilized to reproduce the late Victorian Strand in the opening scenes of Oliver Parker's 2002 film The Importance of Being Earnest. The East Wing of the College appears, as a part of Somerset House, in a number of other productions, such as Wilde, Flyboys and The Duchess.

References

- Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g "Financial Statements for the year to 31 July 2012" (PDF). King's College London. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ a b c "1st December Enrolled Student Headcount 2012/13" (PDF). King's College London. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ^ "Profile" (PDF). King's College London. 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ Byers, David (12 September 2010). "Profile: Durham University". London: The Sunday Times. Retrieved 15 September 2010.(subscription required)

- ^ "About King's - Dates". King's College London. Retrieved 15 June 2012. "1829 - The Duke of Wellington fights a duel with the Earl of Winchilsea in defence of his simultaneous role in the foundation of King's College and his support of the Roman Catholic Relief Act. King George IV signs the royal charter of King's College London."

- ^ "A brief history". University of London. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Foundation of the College". King's College London. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Royal Charter of King's College London" (PDF). King's College London. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ^ "Campuses & Residences Overview". King's College London. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "King's top for MRC Funding". King's College London. 26 June 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities - 2012". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings Results 2012". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2011-2012". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ a b c "King's Nobel laureates". King's College London. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ "University Guide". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 15 September 2010.(subscription required)

- ^ Smaglik, Paul (6 July 2005). "Golden opportunities". 436 (7047). Nature: 144–147. doi:10.1038/nj7047-144a. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Cockburn, King, McDonnell (1969), pp. 345-359

- ^ a b c "Foundation". King's College London. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Hearnshaw (1929), p. 38

- ^ Hibbert, Weinreb, Keay, Keay (2008), p. 958

- ^ a b Banerjee, Jacqueline. "The University of London: The Founding Colleges". Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- ^ MacIlwraith (1884), p. 32

- ^ a b Thompson (1990), p. 5

- ^ a b King's College London and Somerset House, King's College London, c. 1963, p. 2, retrieved 12 February 2013

- ^ "D'OYLY, Reverend Dr George (1778-1846)". King's College London College Archives. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "Sir Robert Peel 2nd Baronet". HM Government. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Thompson (1990), p. 6

- ^ House of Lords Sessional Papers 1801-1833 - Appendix to seventh Report of Commissioners of Woods, Forests & Land Revenue. Vol. 270. Her Majesty's Stationary Office. 1830. p. 48. Retrieved 3 March 2013. Schedule of Grants in Perpetuity of Parts of the Land Revenue of the Crown: "A piece of Ground in the parish of St. Mary-le-Strand, on the East side of Somerset house bounded on the West side by the area next the Building on the East side of Somerset house occupied by the Audit, Tax, and other Offices, on the North side by houses in the Strand on the East side by Strand Lane, and on the South side by the River Thames, except such right of Carriageway and Footway as therein mentioned as a Site for a College to be erected thereon, and called 'King's College, London'".

- ^ "Beginnings: The History of Higher Education in Bloomsbury and Westminster - King's College London". Institute of Education. Retrieved 13 February 2013. "Londoners who did study, for example in Oxford or Cambridge, had to be quite rich and also members of the Anglican Church."

- ^ "The famous Duel". King's College London. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ Harte (1986), p. 73

- ^ a b "Winchilsea insults Wellington". King's College London College Archives. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ a b Holmes (2002), p. 275

- ^ a b "Duel Day - Questions and Answers". King's College London. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "Open Fire!". King's College London College Archives. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ "Alumni celebrate Duel Day". King's College London. 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ Hearnshaw (1929), p. 80

- ^ a b c d e f g Hibbert, Weinreb, Keay, Keay (2008), p. 462

- ^ Prospectus of King's College, London: academical year 1854-5, p. 7

- ^ Thompson (1986), p. 6

- ^ Harte (1986), p. 203

- ^ "King's and the Blitz, September 1940". King's College London. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ Heulin (1979), p. 2

- ^ "The Strand Quadrangle Architectural Competition Preliminary briefing paper" (PDF). King's College London. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ Maddox (2002), p. 124

- ^ "Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin". King's College London. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "King's, DNA & the continuing story". King's College London. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "Dates: 1900-1949". King's College London. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "Certificate FAQs" (PDF). Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ "Law students repeat mooting success". King's College London. 12 March 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- ^ a b Morgan, John (4 February 2013). "'Draconian' measure: King's to cut 205 jobs". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Tickle, Louise; Bowcott, Owen (23 March 2010). "University cuts start to bite". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crace, John (9 February 2010). "Writing off the UK's last palaeographer". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Attwood, Rebecca (28 October 2010). "Major campaign aims to put King's among the fundraising elite". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ a b Grove, Jack (11 March 2013). "Rick Trainor to step down as King's principal". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Jump, Paul (2 September 2011). "King's chemistry department rises again". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ "Three's company: Imperial, King's join UCL in £700m medical project". Times Higher Education. 14 April 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ "The Mond Bequest at King's College London: A Celebration". King's College London. March 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "A brief history of the Chapel" (PDF). King's College London. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ a b Heulin (1979), p. 1

- ^ "The historic announcement". King's College London. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ a b "The Queen opens Somerset House East Wing". King's College London. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Browell, Geoff (2011). "Report (2010)" (PDF). King's College London: 51. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Background". King's College London. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ a b c "Since the 18th century". Somerset House Trust. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ Harte (1986), p. 72

- ^ "Inigo Rooms". King's College London. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ Dickens, Charles (1850). "Chapter 35 - Depression". David Copperfield (2004 ed.). Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "'Roman' Bath". National Trust. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Openhouse 'Roman' Bath". Open House London. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Strand Lane 'Roman Bath' Factsheet". Open House London. June 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Roman(s) bathing - the Strand Lane bath". Strandlines Project. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Abandoned London Tube Stations". BBC. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Aldwych tube station". Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Guy's Campus". King's College London. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "Franklin Wilkins Building, Kings College- 150 Stamford Street, London, UK". Manchesterhistory.net. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Waterloo Campus". King's College London. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "St Thomas' Campus". King's College London. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "Denmark Hill Campus". King's College London. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "About King's". King's College London. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "King's By Numbers". King's College London. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Projects". King's College London. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "King's wins top Green Award". King's College London. Archived from the original on 11 June 2007. Retrieved 25 April 2007.

- ^ "King's library wins prestigious heritage award". King's College London. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 25 April 2007.

- ^ "Current Projects". King's College London. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Strand Quad redevelopment". King's College London. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Professor Sir Richard Trainor KBE - Principal and President". Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "Office of the Principal". King's College London. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ "Chairman of the College Council". King's College London. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "College Council". King's College London. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "The Council and its standing committees" (PDF). King's College London. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ a b King's College London. "The Dean". Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ King's College London. "Vocations group". Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ "Archbishop of Canterbury visits King's". King's College London. 8 May 2006. Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- ^ "Centre for Defence Studies". Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- ^ "King's Centre for Military Health Research". Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ "About RADA". Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ^ "Term dates". King's College London. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Locations". Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ Hume, Marion (2 January 2008). "The Daily Telegraph: A to Z of what's hot for 2008". London. Retrieved 3 January 2008.

- ^ "Major campaign aims to put King's among the fundraising elite". Times Higher Education. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ King's College London (2008), King's College London Corporate identity guidelines, p. 4

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Coates, Sam; Elliott, Francis; Watson, Roland. "The UCAS points system". The Sunday Times University Guide 2005. London. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- ^ "The Times Good University Guide 2008 – King's College London". Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ "King's College London Undergraduate Prospectus 2011". KCL Prospectus 2011. King's College London. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Key Facts". King’s Health Partners. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Division of Medical Education". King’s College London. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Put a smile back on your face". The Independent. London. 29 July 2004. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ "Nursing & Midwifery – About us". King’s College London. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Medical Research Council centres". King’s College London. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Biomedical Research Centres". National Institute for Health Research. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Drug Control Centre". King’s College London. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "The Drug Control Centre at King's College". King's College London. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ "London Olympics 2012". King’s College London. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Official Site: Library Services". King's College London. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Special Collections". Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ^ "CIOT – Using the Library". Chartered Institute of Taxation. 18 December 1997. Archived from the original on 30 September 2006. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ "Franklin Wilkins Library". King's College London. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "New Hunt's House Library". King's College London. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Weston Education Centre". King's College London. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "St Thomas' House Library". King's College London. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "IoP: Library". King's College London. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ "Bethlem Library". King's College London. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Complete University Guide 2025". The Complete University Guide. 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Guardian University Guide 2025". The Guardian. 7 September 2024.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2024". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. 15 August 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2025". Quacquarelli Symonds Ltd. 4 June 2024.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings 2025". Times Higher Education. 9 October 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2011". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Top 200 - The Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2010-2011". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ Coates, Sam; Elliott, Francis; Watson, Roland. "The Times Good University Guide 2009". The Times. London. Retrieved 2 March 2009. [dead link]

- ^ a b "Profile". King's College London. 2006.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "King's wins 'University of the Year'". King's College London. 12 September 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "C3 Honorary Degrees, Fellowships and Honorary Fellowships of King's College London" (PDF). King's College London Ordinances. King's College London. November 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "UCLU". University College London Union. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "Dates: 1850-1899". King's College London. Retrieved 21 January 2013. "1873 - The first students' Union Society is instituted at King's."

- ^ "KING'S COLLEGE LONDON: Union of Students". King's College London Archives. March 2001. Retrieved 21 January 2013. "Records, 1874-1994, of King's College London Union Society, Students' Union, and other student societies".

- ^ a b "Clubs". KCLSU. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "Activities". KCLSU. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ Corcoran, Kieran (30 October 2012). "Opening up the think tank". The Gateway. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ KCL Think Tank Society. "About Us". Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ "King's College London - Student Think Tank re-launched for new academic year". King's College London. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ Thompson (1990), p. 7

- ^ a b "History - The London Varsity". The London Varsity. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ "The London Varsity Live". UniSportOnline. 29 February 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ "Students in university rampage". BBC News. 7 December 2005. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- ^ King's College London. "The College prayer". Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ "Accommodation Services: Frequently Asked Questions & Answers New Applicants" (PDF). King's College London. 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "University of London – Intercollegiate Halls". University of London. 3 March 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ a b c "University of London Accommodation - Garden Halls". University of London. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "University of London Accommodation - College Hall". University of London. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "University of London Accommodation - Connaught Hall". University of London. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "University of London Accommodation - International Hall". University of London. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "University of London Accommodation - Lillian Penson Hall". University of London. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "University of London Accommodation - Nutford House". University of London. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ a b Smith, Helena (8 January 2009). "Obituary: Tassos Papadopoulos". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Glafkos Ioannou Clerides". Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ^ a b "Biography of Marouf al-Bakhit". Retrieved 22 December 2008.(subscription required)

- ^ a b Editors of the American Heritage Dictionaries (2005). The Riverside dictionary of biography. Houghton Mifflin. p. 670. ISBN 978-0618493371. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b O'Neill, Terry (2006). The Bahamas Speed Weeks. Veloce Publishing Ltd. p. 353. ISBN 978-1845840181. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ a b Wolfgang, M. E. & Lambert, R. D. (1977). Africa in Transition. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 204.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Esposito, John L (2004). The Oxford Dictionary of Islam – Abdul-Rahman al-Bazzaz. ISBN 978-0-19-512559-7. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Court Building to be named in honour of Sir Lee Llewellyn Moore on National Heroes Day". Office Of The Prime Minister Of The Government Of St. Kitts & Nevis. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Martin Bourke". Who's Who.(subscription required)

- ^ "Sir Shridath Ramphal". The Commonwealth. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ "Sarojini Naidu (Indian writer and political leader) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Comment (PDF), King's College London, October 2006, p. 11

- ^ Legge, Edward (2005). The Empress Eugenie 1870 to 1910. Kessinger Publishing Co. p. 11. ISBN 978-1417933204.

- ^ "Profile: Sir Jeremy Sullivan". BBC News. 15 February 2007. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ "The Hon Sir David Foskett FKC". King's College London. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ "Judge Abdul G. Koroma". International Court of Justice. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ "Desmond Tutu". King's College London. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ "George Carey – 103rd Archbishop of Canterbury". The Archbishop of Canterbury. Retrieved 31 March 2013.