Amphetamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | α-methylphenethylamine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | amphetamine |

| License data | |

| Dependence liability | Moderate |

| Routes of administration | Medical: oral, nasal inhalation Recreational: oral, nasal inhalation, insufflation, rectal, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Rectal 95–100%; Oral 75–100%[2] |

| Protein binding | 15–40%[3] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic: CYP2D6,[4] DBH,[5] and FMO[6] |

| Elimination half-life | D-amph:9–11h;[4] L-amph:11–14h[4] |

| Excretion | Renal; pH-dependent range: 1–75%[4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.543 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H13N |

| Molar mass | 135.2084 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 0.9±0.1 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 11.3 °C (52.3 °F) [7] |

| Boiling point | 203 °C (397 °F) [8] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Amphetamine[note 1] ( /æmˈfɛtəmin/ ; contracted from alpha‑methylphenethylamine) is a potent central nervous system (CNS) stimulant of the phenethylamine class that is used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy. Amphetamine was discovered in 1887 and exists as two enantiomers: levoamphetamine and dextroamphetamine.[note 2] Amphetamine properly refers to the racemic free base, or equal parts of the enantiomers levoamphetamine and dextroamphetamine in their pure amine forms. Nonetheless, the term is frequently used informally to refer to any combination of the enantiomers, or to either of them alone. Historically, it has been used to treat nasal congestion, depression, and obesity. Amphetamine is also used as a performance and cognitive enhancer, and recreationally as an aphrodisiac and euphoriant. It is a prescription medication in many countries, and unauthorized possession and distribution of amphetamine is often tightly controlled due to the significant health risks associated with uncontrolled or heavy use. Amphetamine is illegally synthesized by clandestine chemists, trafficked, and sold. Based upon the quantity of seized and confiscated drugs and drug precursors worldwide, illicit amphetamine production and trafficking is much less prevalent than that of methamphetamine; in parts of Europe, amphetamine is more prevalent than methamphetamine.[ref-note 1]

The first pharmaceutical amphetamine was Benzedrine, a brand of inhalers used to treat a variety of conditions. Presently, it is typically prescribed as Adderall,[note 3] dextroamphetamine, or the inactive prodrug lisdexamfetamine. Amphetamine, through activation of a trace amine receptor, increases biogenic amine and excitatory neurotransmitter activity in the brain, with its most pronounced effects targeting the catecholamine neurotransmitters norepinephrine and dopamine. At therapeutic doses, this causes emotional and cognitive effects such as euphoria, change in libido, increased arousal, and improved cognitive control. It induces physical effects such as decreased reaction time, fatigue resistance, and increased muscle strength.[ref-note 2]

Much larger doses of amphetamine are likely to impair cognitive function and induce rapid muscle breakdown. Substance dependence (i.e., addiction) is a serious risk of amphetamine abuse, but only rarely arises from medical use. Very high doses can result in a psychosis (e.g., delusions and paranoia) which rarely occurs at therapeutic doses even during long-term use. Recreational doses are generally much larger than prescribed therapeutic doses, and carry a far greater risk of serious side effects.[ref-note 3]

Amphetamine is the parent compound of its own structural class, the substituted amphetamines,[note 4] which includes prominent substances such as bupropion, cathinone, ecstasy, and methamphetamine. Unlike methamphetamine, amphetamine's salts lack sufficient volatility to be smoked. Amphetamine is also chemically related to the naturally occurring trace amine neurotransmitters, specifically phenethylamine and N-methylphenethylamine, both of which are produced within the human body.[ref-note 4]

Uses

Medical

Amphetamine is used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy, and is sometimes prescribed off-label for its past indications, including depression, obesity, and nasal congestion.[20][24] Long-term amphetamine exposure in some species is known to produce abnormal dopamine system development or nerve damage,[33][34] but humans experience normal development and nerve growth.[35][36][37] Magnetic resonance imaging studies suggest that long-term treatment with amphetamine decrease the abnormalities of brain structure and function found in subjects with ADHD, and improve the function of the right caudate nucleus.[35][36][37]

Reviews of clinical stimulant research have established the safety and effectiveness of long-term amphetamine use for ADHD.[38][39] An evidence review noted the findings of a randomized controlled trial of amphetamine treatment for ADHD in Swedish children following 9 months of amphetamine use.[40] During treatment, the children experienced improvements in attention, disruptive behaviors, and hyperactivity, and an average change of +4.5 in IQ.[40] It noted that the population in the study had a high rate of comorbid disorders associated with ADHD and suggested that other long-term amphetamine trials in people with less associated disorders could find greater functional improvements.[40]

Current models of ADHD suggest that it is associated with functional impairments in some of the brain's neurotransmitter systems,[note 5] particularly those involving dopamine and norepinephrine.[41] Psychostimulants like methylphenidate and amphetamine may be effective in treating ADHD because they increase neurotransmitter activity in these systems.[41] Approximately 70% of those who use these stimulants see improvements in ADHD symptoms.[42][43] Children with ADHD who use stimulant medications generally have better relationships with peers and family members,[38][42] generally perform better in school, are less distractible and impulsive, and have longer attention spans.[38][42] The Cochrane Collaboration's review[note 6] on the treatment of adult ADHD with amphetamines stated that amphetamines improve short-term symptoms, but have higher discontinuation rates than non-stimulant medications due to their adverse effects.[45]

A Cochrane Collaboration review on the treatment of ADHD in children with tic disorders indicated that stimulants in general do not make tics worse, but high doses of dextroamphetamine in such people should be avoided.[46] Other Cochrane reviews on the use of amphetamine for improving recovery following stroke or acute brain injury indicated that it may improve recovery, but further research is needed to confirm this.[47][48][49]

Enhancing performance

Therapeutic doses of amphetamine improve cortical network efficiency, resulting in higher performance on working memory tests in all individuals.[17][50] Amphetamine and other ADHD stimulants also improve task saliency and increase arousal.[17][51] Stimulants such as amphetamine can improve performance on difficult and boring tasks,[17][51] and are used by some students as a study and test-taking aid.[52] Based upon studies of self-reported illicit stimulant use, performance-enhancing use, rather than abuse as a recreational drug, is the primary reason that students use stimulants.[53] High amphetamine doses, above the therapeutic range, can interfere with working memory and cognitive control.[17][51]

Amphetamine is used by some athletes for its psychological and performance-enhancing effects, such as increased stamina and alertness, but this is prohibited at events regulated by the World Anti-Doping Agency.[30][54][16] In healthy people at oral therapeutic doses, amphetamine has been shown to increase physical strength,[16][55] acceleration,[16][55] stamina,[16][56] endurance,[16][56] and alertness,[30] while reducing reaction time.[16] Like the psychostimulants methylphenidate and bupropion, amphetamine increases stamina and endurance in humans primarily through reuptake inhibition and effluxion of dopamine in the central nervous system.[55][56] At much higher doses, amphetamine can induce side effects that impair performance, such as rhabdomyolysis and hyperthermia.[15][26][55]

Contraindications

The United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA)[note 7] states that amphetamine is contraindicated in people with a history of drug abuse, heart disease, or severe agitation or anxiety, or in those currently experiencing arteriosclerosis, glaucoma, hyperthyroidism, or severe hypertension.[57] People who have experienced hypersensitivity reactions to other stimulants in the past or are taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are advised not to take amphetamine.[57] The USFDA advises anyone with bipolar disorder, depression, elevated blood pressure, liver or kidney problems, mania, psychosis, Raynaud's phenomenon, seizures, thyroid problems, tics, or Tourette syndrome to monitor their symptoms while taking amphetamine.[57] Amphetamine is classified in US pregnancy category C.[57] This means that detriments to the fetus have been observed in animal studies and adequate human studies have not been conducted; amphetamine may still be prescribed to pregnant women if the potential benefits outweigh the risks.[58] Amphetamine has also been shown to pass into breast milk, so the USFDA advises mothers to avoid breastfeeding when using it.[57] Due to the potential for stunted growth, the USFDA advises monitoring the height and weight of children and adolescents prescribed amphetamines.[57] The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration further contraindicates anorexia.[59]

Side effects

Side effects of amphetamine are varied, and the amount of amphetamine consumed is the primary factor in determining the likelihood and severity of side effects.[15][26][30] Amphetamine products such as Adderall, Dexedrine, and their generic equivalents are currently approved by the USFDA for long-term therapeutic use.[23][26] Recreational use of amphetamine generally involves doses much larger, and therefore has a greater risk of serious side effects than dosages used for therapeutic reasons.[30]

Physical

At normal therapeutic doses, the physical side effects of amphetamine vary widely by age and among individual people.[26] Cardiovascular side effects can include irregular heartbeat (usually increased heart rate), hypertension (high blood pressure) or hypotension (low blood pressure) from a vasovagal response, and Raynaud's phenomenon.[26][30][60] Sexual side effects in males may include erectile dysfunction, frequent erections, or prolonged erections. Other potential side effects include abdominal pain, acne, blurred vision, excessive grinding of the teeth, profuse sweating, dry mouth, loss of appetite, nausea, reduced seizure threshold, tics, and weight loss.[26][30][60] Dangerous physical side effects are rare in typical pharmaceutical doses.[30]

Amphetamine stimulates the medullary respiratory centers, producing faster and deeper breaths.[30] In a normal person at therapeutic doses, amphetamine does not noticeably stimulate breathing, but when respiration is already compromised, it may stimulate it.[30] Amphetamine also induces contraction in the urinary bladder sphincter, which can result in difficulty urinating; this effect can be useful in treating enuresis and incontinence.[30] The effects of amphetamine on the gastrointestinal tract are unpredictable.[30] Amphetamine may reduce gastrointestinal motility if intestinal activity is high, or increase motility if the smooth muscle of the tract is relaxed.[30] Amphetamine also has a slight analgesic effect and can enhance the analgesia of opiates.[30]

USFDA commissioned studies from 2011 indicate that, in children, young adults, and adults, there is no association between serious adverse cardiovascular events (sudden death, myocardial infarction, and stroke) and the medical use of amphetamine or other ADHD stimulants.[ref-note 5]

Psychological

Common psychological effects of therapeutic doses can include alertness, apprehension, concentration, decreased sense of fatigue, mood swings (elevated mood or elation and euphoria followed by mild dysphoria), increased initiative, insomnia or wakefulness, self-confidence, and sociability.[26][30] Less commonly, depending on the user's personality and current mental state, anxiety, change in libido, grandiosity, irritability, repetitive or obsessive behaviors, and restlessness can occur.[ref-note 6] Amphetamine psychosis can occur in heavy users.[15][26][27] Although very rare, this psychosis can also occur at therapeutic doses during long-term therapy.[15][26][28] According to the USFDA, "there is no systematic evidence that stimulants cause aggressive behavior or hostility."[26]

Overdose

An amphetamine overdose is rarely fatal with appropriate care.[66] It can lead to different symptoms.[15][26] A moderate overdose may induce symptoms including irregular heartbeat, confusion, painful urination, high or low blood pressure, hyperthermia, hyperreflexia, muscle pain, severe agitation, rapid breathing, tremor, urinary hesitancy, and urinary retention.[15][26][30] An extremely large overdose may produce symptoms such as adrenergic storm, amphetamine psychosis, anuria, cardiogenic shock, cerebral hemorrhage, circulatory collapse, edema (peripheral or pulmonary), extreme fever, pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, rapid muscle breakdown, serotonin toxicity, and stereotypy.[ref-note 7] Fatal amphetamine poisoning usually involves convulsions and coma.[15][30]

Dependence, addiction, and withdrawal

Addiction is a serious risk with heavy recreational amphetamine use; it is unlikely to arise from typical medical use.[15][29][30] Tolerance develops rapidly in amphetamine abuse, so periods of extended use require increasing doses of the drug in order to achieve the same effect.[69][70]

A Cochrane Collaboration review on amphetamine and methamphetamine dependence and abuse indicates that the current evidence on effective treatments is extremely limited.[71] The review indicated that fluoxetine[note 8] and imipramine[note 9] have some limited benefits in treating abuse and addiction, but concluded, "no treatment has been demonstrated to be effective for the treatment of amphetamine dependence and abuse."[71] A corroborating review indicated that amphetamine dependence is mediated through increased activation of dopamine receptors and co-localized NMDA receptors in the mesolimbic pathway.[72] This review also noted that magnesium ions, which inhibit NMDA receptor calcium channels, and serotonin have inhibitory effects on NMDA receptors.[72] It also suggested that, based upon animal testing, pathological amphetamine use significantly reduces the level of intracellular magnesium throughout the brain.[72] Supplemental magnesium,[note 10] like fluoxetine treatment, has been shown to reduce self-administration in both humans and lab animals.[71][72]

According to another Cochrane Collaboration review on withdrawal in highly dependent amphetamine and methamphetamine abusers, "when chronic heavy users abruptly discontinue amphetamine use, many report a time-limited withdrawal syndrome that occurs within 24 hours of their last dose."[73] This review noted that withdrawal symptoms in chronic, high-dose users are frequent, occurring in up to 87.6% of cases, and persist for three to four weeks with a marked "crash" phase occurring during the first week.[73] Amphetamine withdrawal symptoms can include anxiety, drug craving, dysphoric mood, fatigue, increased appetite, increased movement or decreased movement, lack of motivation, sleeplessness or sleepiness, and vivid or lucid dreams.[73] The review suggested that withdrawal symptoms are associated with the degree of dependence, suggesting that therapeutic use would result in far milder discontinuation symptoms.[73] The USFDA does not indicate the presence of withdrawal symptoms following discontinuation of amphetamine use after an extended period at therapeutic doses.[74][75][76]

Current models of addiction from chronic drug use involve alterations in gene expression in certain parts of the brain.[77][78][79] The most important transcription factors that produce these alterations are ΔFosB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein (CREB), and nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB).[78] ΔFosB is the most significant, since its overexpression in the nucleus accumbens is necessary and sufficient for many of the neural adaptations seen in drug addiction;[78] it has been implicated in addictions to alcohol, cannabinoids, cocaine, nicotine, phenylcyclidine, and substituted amphetamines.[77][78][80] ΔJunD is the transcription factor which directly opposes ΔFosB.[78] Increases in nucleus accumbens ΔJunD expression can reduce or, with a large increase, even block most of the neural alterations seen in chronic drug abuse (i.e., the alterations mediated by ΔFosB).[78] ΔFosB also plays an important role in regulating behavioral responses to natural rewards, such as palatable food, sex, and exercise.[77][78] Since natural rewards, like drugs of abuse, induce ΔFosB, chronic acquisition of these rewards can result in a similar pathological addictive state.[77][78] Consequently, ΔFosB is the key transcription factor involved in amphetamine addiction, especially amphetamine-induced sex addictions.[77][78][81] ΔFosB inhibitors (drugs that oppose its action) may be an effective treatment for addiction and addictive disorders.[82]

The effects of amphetamine on gene regulation are both dose- and route-dependent.[79] Most of the research on gene regulation and addiction is based upon animal studies with intravenous amphetamine administration at very high doses.[79] The few studies that have used equivalent (weight-adjusted) human therapeutic doses and oral administration show that these changes, if they occur, are relatively minor.[79]

Psychosis

Abuse of amphetamine can result in a stimulant psychosis that may present with a variety of symptoms (e.g., paranoia, hallucinations, delusions).[27] A Cochrane Collaboration review on treatment for amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methamphetamine abuse-induced psychosis states that about 5–15% of users fail to recover completely.[27][83] The same review asserts that, based upon at least one trial, antipsychotic medications effectively resolve the symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis.[27] Psychosis very rarely arises from therapeutic use.[28][57]

Toxicity

In rodents and primates, sufficiently high doses of amphetamine cause dopaminergic neurotoxicity, or damage to dopamine neurons, which is characterized as reduced transporter and receptor function.[84] There is no evidence that amphetamine is directly neurotoxic in humans.[85][86] High-dose amphetamine can cause indirect neurotoxicity as a result of increased oxidative stress from reactive oxygen species and autoxidation of dopamine.[33][87][88]

Interactions

Many types of substances are known to interact with amphetamine, resulting in altered drug action or metabolism of amphetamine, the interacting substance, or both.[4][89] Since amphetamine is metabolized by the liver enzyme CYP2D6, inhibitors of this enzyme, such as fluoxetine (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI]) and bupropion, will prolong the elimination half-life of amphetamine.[89] Amphetamine also interacts with MAOIs, particularly monoamine oxidase A inhibitors, since both MAOIs and amphetamine increase plasma catecholamines; therefore, concurrent use of both is dangerous.[89] Amphetamine will modulate the activity of most psychoactive drugs. In particular, amphetamine may decrease the effects of sedatives and depressants and increase the effects of stimulants and antidepressants.[89] Amphetamine may also decrease the effects of antihypertensives and antipsychotics due to its effects on blood pressure and dopamine respectively.[89] There is no significant effect on consuming amphetamine with food in general, but the pH of gastrointestinal content and urine affects the absorption and excretion of amphetamine, respectively.[89] Acidic substances reduce the absorption of amphetamine and increase urinary excretion, and alkaline substances do the opposite.[89] Due to the effect pH has on absorption, amphetamine also interacts with gastric acid reducers such as proton pump inhibitors and H2 antihistamines, which decrease gastrointestinal pH.[89]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

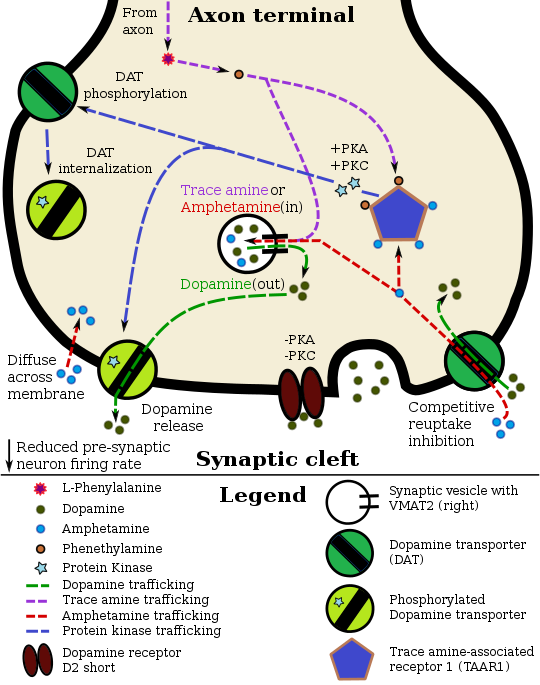

Pharmacodynamics of amphetamine in a dopamine neuron

|

Amphetamine has been identified as a potent full agonist of trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1), a Gs-coupled and Gq-coupled G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) discovered in 2001, which is important for regulation of brain monoamines.[25][96][97] Activation of TAAR1 increases cAMP production via adenylyl cyclase activation and inhibits monoamine transporter function.[25][98] Monoamine autoreceptors (e.g., D2 short, presynaptic α2, and presynaptic 5-HT1A) have the opposite effect of TAAR1, and together these receptors provide a regulatory system for monoamines.[25] Notably, amphetamine and trace amines activate TAAR1, but not monoamine autoreceptors.[25]

In addition to the neuronal monoamine transporters, amphetamine also inhibits vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), SLC22A3, and SLC22A5.[99][100] SLC22A3 is an extraneuronal monoamine transporter that is present in astrocytes and SLC22A5 is a high-affinity carnitine transporter.[99][101] Amphetamine also mildly inhibits both the CYP2A6 and CYP2D6 liver enzymes.[96] Amphetamine is known to strongly induce cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript (CART) gene expression,[96][99] a neuropeptide involved in feeding behavior, stress, and reward, which induces observable increases in neuronal development and survival in vitro.[99][102] The CART receptor has yet to be identified, but there is significant evidence that CART binds to a unique Gi/Go-coupled GPCR.[102][103] Amphetamine also inhibits monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) at high doses, resulting in less dopamine and phenethylamine metabolism and consequently higher concentrations of synaptic monoamines.[4][9]

Amphetamine exerts its behavioral effects by modulating monoamine neurotransmission in the brain, primarily in catecholamine neurons.[25][96] The full profile of amphetamine drug effects is derived almost entirely from increasing the neurotransmission of dopamine,[25] serotonin,[25] norepinephrine,[25] epinephrine,[90] histamine,[90] CART peptides,[96] acetylcholine,[104][105] and glutamate,[106][107] which it effects through interactions with CART, TAAR1, and VMAT2.[25][96][90]

The effect of amphetamine on monoamine transporters in the brain appears to be site-specific.[25] Imaging studies indicate that monoamine reuptake inhibition by amphetamine and trace amines is dependent upon the presence of TAAR1 co-localization in the associated monoamine neurons.[25] As of 2010, co-localization of TAAR1 and the dopamine transporter (DAT) has been visualized in rhesus monkeys, but co-localization of TAAR1 with the norepinephrine transporter (NET) and the serotonin transporter (SERT) has only been evidenced by messenger RNA (mRNA) expression.[25]

The major neural systems affected by amphetamine are largely implicated in the reward and executive function pathways of the brain, collectively known as the mesocorticolimbic projection.[108] The concentrations of the primary neurotransmitters involved in reward circuitry and executive functioning, dopamine and norepinephrine, are markedly increased in a dose-dependent manner by amphetamine due to its effects on monoamine transporters.[25][90][108] The reinforcing and task saliency effects of amphetamine are mostly due to enhanced dopaminergic activity in the mesolimbic pathway.[17]

Dextroamphetamine is a more potent agonist of TAAR1 than levoamphetamine.[109] Consequently, dextroamphetamine produces greater CNS stimulation than levoamphetamine, roughly three to four times more, but levoamphetamine has slightly stronger cardiovascular and peripheral effects.[30][109]

Dopamine

In certain brain regions, amphetamine increases the concentrations of dopamine in the synaptic cleft, heightening the response of the post-synaptic neuron.[25] Through a TAAR1-mediated mechanism, the firing rate of dopamine receptors decreases, preventing a hyper-dopaminergic state.[25][110] Amphetamine can can enter the presynaptic neuron either through DAT or by diffusing across the neuronal membrane directly.[25] As a consequence of DAT uptake, amphetamine produces competitive reuptake inhibition at the transporter.[25] Upon entering the presynaptic neuron, amphetamine activates TAAR1 which, through protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) signaling, causes DAT phosphorylation.[25] Phosphorylation by either protein kinase can result in DAT internalization (non-competitive reuptake inhibition), but PKC-mediated phosphorylation alone induces reverse transporter function (dopamine efflux).[25][111]

Amphetamine is also a substrate for the presynaptic vesicular transporter, VMAT2.[90] Following amphetamine uptake at VMAT2, the synaptic vesicle releases dopamine molecules into the cytosol in exchange.[90] Subsequently, the cytosolic dopamine molecules exit the presynaptic neuron via reverse transport at DAT.[25][90]

Norepinephrine

Similar to dopamine, amphetamine dose-dependently increases the level of synaptic norepinephrine, the direct precursor of epinephrine.[32][108] Based upon neuronal TAAR1 mRNA expression, amphetamine is thought to affect norepinephrine analogously to dopamine.[25][90][111] In other words, amphetamine induces TAAR1-mediated efflux and non-competitive reuptake inhibition at phosphorylated NET, competitive NET reuptake inhibition, and norepinephrine release from VMAT2.[25][90]

Serotonin

Amphetamine exerts analogous, yet less pronounced, effects on serotonin as on dopamine and norepinephrine.[25][108] Amphetamine affects serotonin via VMAT2 and, like norepinephrine, is thought to phosphorylate SERT via TAAR1.[25][90]

Acetylcholine

Amphetamine has no direct effect on acetylcholine, but several studies have noted that acetylcholine release increases after its use.[104][105] In lab animals, high doses of amphetamine greatly increase acetylcholine levels in certain brain regions, including the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and nucleus accumbens.[104] In humans, a similar phenomenon occurs via the cholinergic–dopaminergic link, mediated by the neuropeptide ghrelin, in the ventral tegmentum.[105] This heightened cholinergic activity leads to increased nicotinic receptor activation in the CNS, a factor which likely contributes to the nootropic effects of amphetamine.[112]

Other relevant activity

Extracellular levels of glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, have been shown to increase upon exposure to amphetamine.[106][107] This cotransmission effect was found in the mesolimbic pathway, an area of the brain implicated in reward, where amphetamine is known to affect dopamine neurotransmission.[106][107] Amphetamine also induces effluxion of histamine from synaptic vesicles in CNS mast cells and histaminergic neurons through VMAT2.[90]

Pharmacokinetics

The oral bioavailability of amphetamine varies with gastrointestinal pH;[89] it is well absorbed from the gut, and bioavailability is typically over 75% for dextroamphetamine.[2] Amphetamine is a weak base with a pKa of 9–10;[4] consequently, when the pH is basic, more of the drug is in its lipid soluble free base form, and more is absorbed through the lipid-rich cell membranes of the gut epithelium.[4][89] Conversely, an acidic pH means the drug is predominantly in a water soluble cationic (salt) form, and less is absorbed.[4] Approximately 15–40% of amphetamine circulating in the bloodstream is bound to plasma proteins.[3]

The half-life of amphetamine enantiomers differ and vary with urine pH.[4] At normal urine pH, the half-lives of dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine are 9–11 hours and 11–14 hours, respectively.[4] An acidic diet will reduce the enantiomer half-lives to 8–11 hours; an alkaline diet will increase the range to 16–31 hours.[113][114] The immediate-release and extended release variants of salts of both isomers reach peak plasma concentrations at 3 hours and 7 hours post-dose respectively.[4] Amphetamine is eliminated via the kidneys, with 30–40% of the drug being excreted unchanged at normal urinary pH.[4] When the urinary pH is basic, amphetamine is in its free base form, so less is excreted.[4] When urine pH is abnormal, the urinary recovery of amphetamine may range from a low of 1% to a high of 75%, depending mostly upon whether urine is too basic or acidic, respectively.[4] Amphetamine is usually eliminated within two days of the last oral dose.[113] Apparent half-life and duration of effect increase with repeated use and accumulation of the drug.[115]

The prodrug lisdexamfetamine is not as sensitive to pH as amphetamine when being absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract;[116] following absorption into the blood stream, it is converted by red blood cell-associated enzymes to dextroamphetamine via hydrolysis.[116] The elimination half-life of lisdexamfetamine is generally less than one hour.[116]

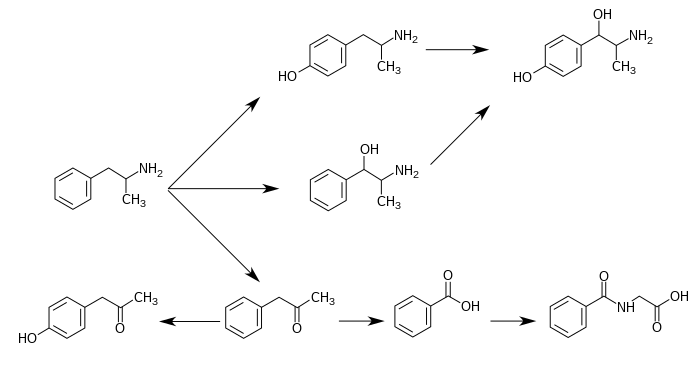

CYP2D6, dopamine β-hydroxylase, and flavin-containing monooxygenase are the only enzymes currently known to metabolize amphetamine in humans.[5][6][117] Amphetamine has a variety of excreted metabolic products, including 4-hydroxyamfetamine, 4-hydroxynorephedrine, 4-hydroxyphenylacetone, benzoic acid, hippuric acid, norephedrine, and phenylacetone.[4][113][118] Among these metabolites, the active sympathomimetics are 4‑hydroxyamphetamine,[119] 4‑hydroxynorephedrine,[120] and norephedrine.[121] The main metabolic pathways involve aromatic para-hydroxylation, aliphatic alpha- and beta-hydroxylation, N-oxidation, N-dealkylation, and deamination.[4][113] The known pathways and detectable metabolites include:[4][6][118]

Metabolic pathways of amphetamine in humans[sources 1]

|

Related endogenous compounds

Amphetamine has a very similar structure and function to the endogenous trace amines, which are naturally occurring neurotransmitter molecules produced in the human body and brain.[25][32] Among this group, the most closely related compounds are phenethylamine, the parent compound of amphetamine, and N-methylphenethylamine, an isomer of amphetamine (i.e., it has an identical molecular formula).[25][32][130] In humans, phenethylamine is produced directly from L-phenylalanine by the aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) enzyme, which converts L-DOPA into dopamine as well.[32][130] In turn, N‑methylphenethylamine is metabolized from phenethylamine by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase, the same enzyme that metabolizes norepinephrine into epinephrine.[32][130] Like amphetamine, both phenethylamine and N‑methylphenethylamine regulate monoamine neurotransmission via TAAR1;[25][130] unlike amphetamine, both of these substances are broken down by MAO-B, and therefore have a shorter half-life than amphetamine.[32][130]

Physical and chemical properties

Phenyl-2-nitropropene (right cups)

Amphetamine is a methyl homolog of the mammalian neurotransmitter phenethylamine with the chemical formula Template:Chemical formula. The carbon atom adjacent to the primary amine is a stereogenic center, and amphetamine is composed of a racemic 1:1 mixture of two enantiomeric mirror images.[10] This racemic mixture can be separated into its optical isomers:[note 12] levoamphetamine and dextroamphetamine.[10] Physically, at room temperature, the pure free base of amphetamine is a mobile, colorless, and volatile liquid with a characteristically strong amine odor, and acrid, burning taste.[131] Frequently prepared solid salts of amphetamine include amphetamine aspartate,[15] hydrochloride,[132] phosphate,[133] saccharate,[15] and sulfate,[15] the last of which is the most common amphetamine salt.[31] Amphetamine is also the parent compound of its own structural class, which includes a number of psychoactive derivatives.[10] In organic chemistry, amphetamine is an excellent chiral ligand for the stereoselective synthesis of 1,1'-bi-2-naphthol.[134]

Derivatives

Amphetamine derivatives, often referred to as "amphetamines" or "substituted amphetamines", are a broad range of chemicals that contain amphetamine as a "backbone".[135][136] The class includes stimulants like methamphetamine, serotonergic empathogens like MDMA (ecstasy), and decongestants like ephedrine, among other subgroups.[135][136] This class of chemicals is sometimes referred to collectively as the "amphetamine family."[137]

Synthesis

Template:Details3 Since the first preparation was reported in 1887,[138] many synthetic routes to amphetamine have been developed.[139][140] Many are based on classic organic reactions. One such example is the Friedel–Crafts alkylation of chlorobenzene by allyl chloride to yield beta chloropropylbenzene which is then reacted with ammonia to produce racemic amphetamine (method 1).[141] Another example employs the Ritter reaction (method 2). In this route, allylbenzene is reacted acetonitrile in sulfuric acid to yield an organosulfate which in turn is treated with sodium hydroxide to give amphetamine via an acetamide intermediate.[142][143] A third route starts with ethyl 3-oxobutanoate which through a double alkylation with methyl iodide followed by benzyl chloride can be converted into 2-methyl-3-phenyl-propanoic acid. This synthetic intermediate can be transformed into amphetamine using either a Hofmann or Curtius rearrangement (method 3).[144]

A significant number of amphetamine syntheses feature a reduction of a nitro, imine, oxime or other nitrogen-containing functional group.[139] In one such example, a Knoevenagel condensation of benzaldehyde with nitroethane yields phenyl-2-nitropropene. The double bond and nitro group of this intermediate is reduced using either catalytic hydrogenation or by treatment with lithium aluminium hydride (method 4).[145][146] Another method is the reaction of phenylacetone with ammonia, producing an imine intermediate that is reduced to the primary amine using hydrogen over a palladium catalyst or lithium aluminum hydride (method 5).[146]

The most common route of both legal and illicit amphetamine synthesis employs a non-metal reduction known as the Leuckart reaction (method 6).[31][146] In the first step, a reaction between phenylacetone and formamide, either using additional formic acid or formamide itself as a reducing agent, yields N-formylamphetamine.[146][147] This intermediate is then hydrolyzed using hydrochloric acid, and subsequently basified, extracted with organic solvent, concentrated, and distilled to yield the free base.[146] The free base is then dissolved in an organic solvent, sulfuric acid added, and amphetamine precipitates out as the sulfate salt.[146]

A number of chiral resolutions have been developed to separate the two enantiomers of amphetamine.[140] For example, racemic amphetamine can be treated with d-tartaric acid to form a diastereoisomeric salt which is fractionally crystallized to yield dextroamphetamine.[148] Chiral resolution remains the most economical method for obtaining optically pure amphetamine on a large scale.[149] In addition, several enantioselective syntheses of amphetamine have been developed. In one example, optically pure (R)-1-phenyl-ethanamine is condensed with phenylacetone to yield a chiral schiff base. In the key step, this intermediate is reduced by catalytic hydrogenation with a transfer of chirality to the carbon atom alpha to the amino group. Cleavage of the benzylic amine bond by hydrogenation yields optically pure dextroamphetamine.[149]

|

|

|

Detection in body fluids

Amphetamine is frequently measured in urine or blood as part of a drug test for sports, employment, poisoning diagnostics, and forensics.[ref-note 8] Techniques such as immunoassay, which is the most common form of amphetamine test, may cross-react with a number of sympathomimetic drugs.[153] Chromatographic methods specific for amphetamine are employed to prevent false positive results.[154] Chiral separation techniques may be employed to help distinguish the source of the drug, whether prescription amphetamine, prescription amphetamine prodrugs, (e.g., selegiline), over-the-counter drug products (e.g., Vicks Vapoinhaler) or illicitly obtained substituted amphetamines.[154][155][156] Several prescription drugs produce amphetamine as a metabolite, including benzphetamine, clobenzorex, famprofazone, fenproporex, lisdexamfetamine, mesocarb, methamphetamine, prenylamine, and selegiline, among others.[20][157][158] These compounds may produce positive results for amphetamine on drug tests.[157][158] Amphetamine is generally only detectable by a standard drug test for approximately 24 hours, although a high dose may be detectable for two to four days.[153]

For the assays, a study noted that an enzyme multiplied immunoassay technique (EMIT) assay for amphetamine and methamphetamine may produce more false positives than liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry.[155] Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) of amphetamine and methamphetamine with the derivatizing agent (S)-(−)-trifluoroacetylprolyl chloride allows for the detection of methamphetamine in urine.[154] GC–MS of amphetamine and methamphetamine with the chiral derivatizing agent Mosher's acid chloride allows for the detection of both dextroamphetamine and dextromethamphetamine in urine.[154] Hence, the latter method may be used on samples that test positive using other methods to help distinguish between the various sources of the drug.[154]

History, society, and culture

Amphetamine was first synthesized in 1887 in Germany by Romanian chemist Lazăr Edeleanu who named it phenylisopropylamine;[138][159][160] its stimulant effects remained unknown until 1927, when it was independently resynthesized by Gordon Alles and reported to have sympathomimetic properties.[160] Amphetamine had no pharmacological use until 1934, when Smith, Kline and French began selling it as an inhaler under the trade name Benzedrine as a decongestant.[21] During World War II, amphetamines and methamphetamine were used extensively by both the Allied and Axis forces for their stimulant and performance-enhancing effects.[138][161][162] As the addictive properties of the drug became known, governments began to place strict controls on the sale of amphetamine.[138] For example, during the early 1970s in the United States, amphetamine became a schedule II controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act.[163] In spite of strict government controls, amphetamine has been used legally or illicitly by people from a variety of backgrounds, including authors,[164] musicians,[165] mathematicians,[166] and athletes.[16]

Legal status

As a result of the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances, amphetamine became a schedule II controlled substance, as defined in the treaty, in all (183) state parties.[14] Consequently, it is heavily regulated in most countries.[167][168] Some countries, such as South Korea and Japan, have banned substituted amphetamines even for medical use.[169][170] In other nations, such as Canada (schedule I drug),[171] the United States (schedule II drug),[15] Thailand (category 1 narcotic),[172] and United Kingdom (class B drug),[173] amphetamine is in a restrictive national drug schedule that allows for its use as a medical treatment.[19][22]

Pharmaceutical products

The only currently prescribed amphetamine formulation that contains both enantiomers is Adderall.[note 3][10][20] Amphetamine is also prescribed in enantiopure and prodrug form as dextroamphetamine and lisdexamfetamine respectively.[23][174] Lisdexamfetamine is structurally different from amphetamine, and is inactive until it metabolizes into dextroamphetamine.[174] The free base of racemic amphetamine was previously available as Benzedrine, Psychedrine, and Sympatedrine.[10][20] Levoamphetamine was previously available as Cydril.[20] All current amphetamine pharmaceuticals are salts due to the comparatively high volatility of the free base.[20][23][31] Some of the current brands and their generic equivalents are listed below.

|

|

Notes

- ^ Synonyms and alternate spellings include: α-methylphenethylamine, amfetamine (International Nonproprietary Name [INN], British Approved Name [BAN]), β-phenylisopropylamine, speed, 1-phenylpropan-2-amine, α-methylbenzeneethanamine, and desoxynorephedrine.[9][10][11]

- ^ Enantiomers are molecules that are mirror images of one another; they are structurally identical, but of the opposite orientation.[12]

Levoamphetamine and dextroamphetamine are also known as L-amph or levamfetamine (INN) and D-amph or dexamfetamine (INN) respectively.[9] - ^ a b "Adderall" is a brand name as opposed to a nonproprietary name; because the latter ("dextroamphetamine sulfate, dextroamphetamine saccharate, amphetamine sulfate, and amphetamine aspartate"[23]) is excessively long, this article exclusively refers to this amphetamine mixture by the brand name.

- ^ Due to confusion that may arise from use of the plural form, this article will only use the terms "amphetamine" and "amphetamines" to refer to racemic amphetamine, levoamphetamine, and dextroamphetamine and reserve the term "substituted amphetamines" for the class.

- ^ This involves impaired dopamine neurotransmission in the mesocortical and mesolimbic pathways and norepinephrine neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex and locus coeruleus.[41]

- ^ Cochrane Collaboration reviews are high quality meta-analytic systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials.[44]

- ^ The prescribing information in a package insert is the copyrighted intellectual property of the manufacturer and approved by the USFDA. For simplicity, this section will refer to the USFDA instead of the manufacturer.

- ^ During short-term treatment, fluoxetine may decrease drug craving.[71]

- ^ During "medium-term treatment," imipramine may extend the duration of adherence to addiction treatment.[71]

- ^ The review indicated that magnesium L-aspartate and magnesium chloride produce significant changes in addictive behavior;[72] other forms of magnesium were not mentioned.

- ^ 4-Hydroxyamphetamine has been shown to be metabolized into 4-hydroxynorephedrine by dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) in vitro and it is presumed to be metabolized similarly in vivo.[122][125] Evidence from studies that measured the effect of serum DBH concentrations on 4-hydroxyamphetamine metabolism in humans suggests that a different enzyme may mediate the conversion of 4-hydroxyamphetamine to 4-hydroxynorephedrine;[125][127] however, other evidence from animal studies suggests that this reaction is catalyzed by DBH in synaptic vesicles within noradrenergic neurons in the brain.[128][129]

- ^ Enantiomers are molecules that are mirror images of one another; they are structurally identical, but of the opposite orientation.[12]

Reference notes

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Dextroamphetamine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Amphetamine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. December 2013. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 30 December 2013. Cite error: The named reference "FDA Pharmacokinetics" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito W (2013). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry (7th ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 648. ISBN 1609133455.

Alternatively, direct oxidation of amphetamine by DA β-hydroxylase can afford norephedrine.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Krueger SK, Williams DE (June 2005). "Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism". Pharmacol. Ther. 106 (3): 357–387. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001. PMC 1828602. PMID 15922018. Cite error: The named reference "FMO" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Amphetamine". Chemspider. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ "Amphetamine". PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Amphetamine". PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f "Amphetamine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ "Amphetamines (speed): what are the effects?". Monthly Index of Medical Specialities. 27 January 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Enantiomer". IUPAC Goldbook. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. doi:10.1351/goldbook.E02069. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

One of a pair of molecular entities which are mirror images of each other and non-superposable.

- ^ "Amphetamine". National Library of Medicine – Medical Subject Headings. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Convention on psychotropic substances". United Nations Treaty Collection. United Nations. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. December 2013. p. 11. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Liddle DG, Connor DJ (June 2013). "Nutritional supplements and ergogenic AIDS". Prim. Care. 40 (2): 487–505. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.02.009. PMID 23668655.

Amphetamines and caffeine are stimulants that increase alertness, improve focus, decrease reaction time, and delay fatigue, allowing for an increased intensity and duration of training ...

Physiologic and performance effects

• Amphetamines increase dopamine/norepinephrine release and inhibit their reuptake, leading to central nervous system (CNS) stimulation

• Amphetamines seem to enhance athletic performance in anaerobic conditions 39 40

• Improved reaction time

• Increased muscle strength and delayed muscle fatigue

• Increased acceleration

• Increased alertness and attention to task - ^ a b c d e f g h Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 13: Higher Cognitive Function and Behavioral Control". In Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 318. ISBN 9780071481274.

Therapeutic (relatively low) doses of psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and amphetamine, improve performance on working memory tasks both in in normal subjects and those with ADHD. Positron emission tomography (PET) demonstrates that methylphenidate decreases regional cerebral blood flow in the doroslateral prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex while improving performance of a spacial working memory task. This suggests that cortical networks that normally process spatial working memory become more efficient in response to the drug. ... [It] is now believed that dopamine and norepinephrine, but not serotonin, produce the beneficial effects of stimulants on working memory. At abused (relatively high) doses, stimulants can interfere with working memory and cognitive control ... stimulants act not only on working memory function, but also on general levels of arousal and, within the nucleus accumbens, improve the saliency of tasks. Thus, stimulants improve performance on effortful but tedious tasks ... through indirect stimulation of dopamine and norepinephrine receptors.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Montgomery KA (June 2008). "Sexual desire disorders". Psychiatry (Edgmont). 5 (6): 50–55. PMC 2695750. PMID 19727285.

- ^ a b Wilens TE, Adler LA, Adams J, Sgambati S, Rotrosen J, Sawtelle R, Utzinger L, Fusillo S (January 2008). "Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: a systematic review of the literature". J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 47 (1): 21–31. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a56f1. PMID 18174822.

Stimulant misuse appears to occur both for performance enhancement and their euphorogenic effects, the latter being related to the intrinsic properties of the stimulants (e.g., IR versus ER profile) ...

Although useful in the treatment of ADHD, stimulants are controlled II substances with a history of preclinical and human studies showing potential abuse liability.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Heal DJ, Smith SL, Gosden J, Nutt DJ (June 2013). "Amphetamine, past and present – a pharmacological and clinical perspective". J. Psychopharmacol. 27 (6): 479–496. doi:10.1177/0269881113482532. PMC 3666194. PMID 23539642.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Rasmussen N (July 2006). "Making the first anti-depressant: amphetamine in American medicine, 1929–1950". J . Hist. Med. Allied Sci. 61 (3): 288–323. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrj039. PMID 16492800.

- ^ a b Chawla S, Le Pichon T (2006). "World Drug Report 2006" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. pp. 128–135. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "National Drug Code Amphetamine Search Results". National Drug Code Directory. United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 16 December 2013 suggested (help) - ^ a b "Adderall IR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. March 2007. p. 5. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. December 2013. pp. 4–8. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Shoptaw SJ, Kao U, Ling W (2009). Shoptaw SJ, Ali R (ed.). "Treatment for amphetamine psychosis". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (1): CD003026. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003026.pub3. PMID 19160215.

A minority of individuals who use amphetamines develop full-blown psychosis requiring care at emergency departments or psychiatric hospitals. In such cases, symptoms of amphetamine psychosis commonly include paranoid and persecutory delusions as well as auditory and visual hallucinations in the presence of extreme agitation. More common (about 18%) is for frequent amphetamine users to report psychotic symptoms that are sub-clinical and that do not require high-intensity intervention ...

About 5–15% of the users who develop an amphetamine psychosis fail to recover completely (Hofmann 1983) ...

Findings from one trial indicate use of antipsychotic medications effectively resolves symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Greydanus D. "Stimulant Misuse: Strategies to Manage a Growing Problem" (PDF). American College Health Association (Review Article). ACHA Professional Development Program. p. 20. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ a b Stolerman IP (2010). Stolerman IP (ed.). Encyclopedia of Psychopharmacology. Berlin; London: Springer. p. 78. ISBN 9783540686989.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Westfall DP, Westfall TC (2010). "Miscellaneous Sympathomimetic Agonists". In Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC (ed.). Goodman & Gilman's Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071624428.

{{cite book}}: External link in|sectionurl=|sectionurl=ignored (|section-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Amphetamine". European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacol. Ther. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

Fig. 2. Synthetic and metabolic pathways for endogenous and exogenously administered trace amines and sympathomimetic amines ...

Trace amines are metabolized in the mammalian body via monoamine oxidase (MAO; EC 1.4.3.4) (Berry, 2004) (Fig. 2) ... It deaminates primary and secondary amines that are free in the neuronal cytoplasm but not those bound in storage vesicles of the sympathetic neurone ...

Thus, MAO inhibitors potentiate the peripheral effects of indirectly acting sympathomimetic amines ... this potentiation occurs irrespective of whether the amine is a substrate for MAO. An α-methyl group on the side chain, as in amphetamine and ephedrine, renders the amine immune to deamination so that they are not metabolized in the gut. Similarly, β-PEA would not be deaminated in the gut as it is a selective substrate for MAO-B which is not found in the gut ...

Brain levels of endogenous trace amines are several hundred-fold below those for the classical neurotransmitters noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin but their rates of synthesis are equivalent to those of noradrenaline and dopamine and they have a very rapid turnover rate (Berry, 2004). Endogenous extracellular tissue levels of trace amines measured in the brain are in the low nanomolar range. These low concentrations arise because of their very short half-life ... - ^ a b Carvalho M, Carmo H, Costa VM, Capela JP, Pontes H, Remião F, Carvalho F, Bastos Mde L (August 2012). "Toxicity of amphetamines: an update". Arch. Toxicol. 86 (8): 1167–1231. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0815-5. PMID 22392347.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Berman S, O'Neill J, Fears S, Bartzokis G, London ED (2008). "Abuse of amphetamines and structural abnormalities in the brain". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1141: 195–220. doi:10.1196/annals.1441.031. PMC 2769923. PMID 18991959.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hart H, Radua J, Nakao T, Mataix-Cols D, Rubia K (February 2013). "Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects". JAMA Psychiatry. 70 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.277. PMID 23247506.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Spencer TJ, Brown A, Seidman LJ, Valera EM, Makris N, Lomedico A, Faraone SV, Biederman J (September 2013). "Effect of psychostimulants on brain structure and function in ADHD: a qualitative literature review of magnetic resonance imaging-based neuroimaging studies". J. Clin. Psychiatry. 74 (9): 902–917. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08287. PMC 3801446. PMID 24107764.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Frodl T, Skokauskas N (February 2012). "Meta-analysis of structural MRI studies in children and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder indicates treatment effects". Acta psychiatrica Scand. 125 (2): 114–126. PMID 22118249.

Basal ganglia regions like the right globus pallidus, the right putamen, and the nucleus caudatus are structurally affected in children with ADHD. These changes and alterations in limbic regions like ACC and amygdala are more pronounced in non-treated populations and seem to diminish over time from child to adulthood. Treatment seems to have positive effects on brain structure.

- ^ a b c Millichap JG (2010). "Chapter 3: Medications for ADHD". In Millichap JG (ed.). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 111–113. ISBN 9781441913968.

- ^ Chavez B, Sopko MA, Ehret MJ, Paulino RE, Goldberg KR, Angstadt K, Bogart GT (June 2009). "An update on central nervous system stimulant formulations in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Ann. Pharmacother. 43 (6): 1084–1095. doi:10.1345/aph.1L523. PMID 19470858.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Millichap JG (2010). Millichap JG (ed.). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 122–123. ISBN 9781441913968.

- ^ a b c Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 154–157. ISBN 9780071481274.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Stimulants for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". WebMD. Healthwise. 12 April 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ Greenhill LL, Pliszka S, Dulcan MK, Bernet W, Arnold V, Beitchman J, Benson RS, Bukstein O, Kinlan J, McClellan J, Rue D, Shaw JA, Stock S (2002). "Practice parameter for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents, and adults". J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 41 (2 Suppl): 26S–49S. PMID 11833633.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scholten RJ, Clarke M, Hetherington J (August 2005). "The Cochrane Collaboration". Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 59 Suppl 1: S147–S149, discussion S195–S196. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602188. PMID 16052183.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Castells X, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Bosch R, Nogueira M, Casas M (2011). Castells X (ed.). "Amphetamines for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (6): CD007813. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007813.pub2. PMID 21678370.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pringsheim T, Steeves T (April 2011). Pringsheim T (ed.). "Pharmacological treatment for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children with comorbid tic disorders". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (4): CD007990. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007990.pub2. PMID 21491404.

- ^ Martinsson L, Hårdemark H, Eksborg S (January 2007). Martinsson L (ed.). "Amphetamines for improving recovery after stroke". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (1): CD002090. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002090.pub2. PMID 17253474.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Forsyth RJ, Jayamoni B, Paine TC (October 2006). Forsyth RJ (ed.). "Monoaminergic agonists for acute traumatic brain injury". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (4): CD003984. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003984.pub2. PMID 17054192.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harbeck-Seu A, Brunk I, Platz T, Vajkoczy P, Endres M, Spies C (April 2011). "A speedy recovery: amphetamines and other therapeutics that might impact the recovery from brain injury". Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 24 (2): 144–153. doi:10.1097/ACO.0b013e328344587f. PMID 21386667.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Devous MD, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ (2001). "Regional cerebral blood flow response to oral amphetamine challenge in healthy volunteers". J. Nucl. Med. 42 (4): 535–42. PMID 11337538.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Wood S, Sage JR, Shuman T, Anagnostaras SG (2014). "Psychostimulants and cognition: a continuum of behavioral and cognitive activation". Pharmacol. Rev. 66 (1): 193–221. doi:10.1124/pr.112.007054. PMID 24344115.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Twohey M (26 March 2006). "Pills become an addictive study aid". JS Online. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ Teter CJ, McCabe SE, LaGrange K, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ (October 2006). "Illicit use of specific prescription stimulants among college students: prevalence, motives, and routes of administration". Pharmacotherapy. 26 (10): 1501–1510. doi:10.1592/phco.26.10.1501. PMC 1794223. PMID 16999660.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bracken NM (January 2012). "National Study of Substance Use Trends Among NCAA College Student-Athletes" (PDF). NCAA Publications. National Collegiate Athletic Association. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d Parr JW (July 2011). "Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and the athlete: new advances and understanding". Clin Sports Med. 30 (3): 591–610. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2011.03.007. PMID 21658550.

- ^ a b c Roelands B, de Koning J, Foster C, Hettinga F, Meeusen R (May 2013). "Neurophysiological determinants of theoretical concepts and mechanisms involved in pacing". Sports Med. 43 (5): 301–311. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0030-4. PMID 23456493.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. December 2013. pp. 4–6. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "FDA Pregnancy Categories" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. 21 October 2004. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ "Dexamphetamine tablets". Therapeutic Goods Administration. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ a b Vitiello B (April 2008). "Understanding the risk of using medications for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with respect to physical growth and cardiovascular function". Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 17 (2): 459–474. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.010. PMC 2408826. PMID 18295156.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety Review Update of Medications used to treat Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children and young adults". United States Food and Drug Administration. 20 December 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ Cooper WO, Habel LA, Sox CM, Chan KA, Arbogast PG, Cheetham TC, Murray KT, Quinn VP, Stein CM, Callahan ST, Fireman BH, Fish FA, Kirshner HS, O'Duffy A, Connell FA, Ray WA (November 2011). "ADHD drugs and serious cardiovascular events in children and young adults". N. Engl. J. Med. 365 (20): 1896–1904. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110212. PMID 22043968.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety Review Update of Medications used to treat Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults". United States Food and Drug Administration. 15 December 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ Habel LA, Cooper WO, Sox CM, Chan KA, Fireman BH, Arbogast PG, Cheetham TC, Quinn VP, Dublin S, Boudreau DM, Andrade SE, Pawloski PA, Raebel MA, Smith DH, Achacoso N, Uratsu C, Go AS, Sidney S, Nguyen-Huynh MN, Ray WA, Selby JV (December 2011). "ADHD medications and risk of serious cardiovascular events in young and middle-aged adults". JAMA. 306 (24): 2673–2683. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1830. PMC 3350308. PMID 22161946.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b O'Connor PG (February 2012). "Amphetamines". Merck Manual for Health Care Professionals. Merck. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ a b Spiller HA, Hays HL, Aleguas A (June 2013). "Overdose of drugs for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: clinical presentation, mechanisms of toxicity, and management". CNS Drugs. 27 (7): 531–543. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0084-8. PMID 23757186.

Amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methylphenidate act as substrates for the cellular monoamine transporter, especially the dopamine transporter (DAT) and less so the norepinephrine (NET) and serotonin transporter. The mechanism of toxicity is primarily related to excessive extracellular dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Albertson TE (2011). "Amphetamines". In Olson KR, Anderson IB, Benowitz NL, Blanc PD, Kearney TE, Kim-Katz SY, Wu AHB (ed.). Poisoning & Drug Overdose (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 77–79. ISBN 9780071668330.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Oskie SM, Rhee JW (11 February 2011). "Amphetamine Poisoning". Emergency Central. Unbound Medicine. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ "Amphetamines: Drug Use and Abuse". Merck Manual Home Edition. Merck. February 2003. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- ^ Pérez-Mañá C, Castells X, Torrens M, Capellà D, Farre M (2013). Pérez-Mañá C (ed.). "Efficacy of psychostimulant drugs for amphetamine abuse or dependence". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9: CD009695. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009695.pub2. PMID 23996457.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N, Kittirattanapaiboon P (2001). Srisurapanont M (ed.). "Treatment for amphetamine dependence and abuse". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (4): CD003022. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003022. PMID 11687171.

Although there are a variety of amphetamines and amphetamine derivatives, the word "amphetamines" in this review stands for amphetamine, dextroamphetamine and methamphetamine only.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Nechifor M (March 2008). "Magnesium in drug dependences". Magnes. Res. 21 (1): 5–15. PMID 18557129.

- ^ a b c d Shoptaw SJ, Kao U, Heinzerling K, Ling W (2009). Shoptaw SJ (ed.). "Treatment for amphetamine withdrawal". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2): CD003021. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003021.pub2. PMID 19370579.

The prevalence of this withdrawal syndrome is extremely common (Cantwell 1998; Gossop 1982) with 87.6% of 647 individuals with amphetamine dependence reporting six or more signs of amphetamine withdrawal listed in the DSM when the drug is not available (Schuckit 1999) ... Withdrawal symptoms typically present within 24 hours of the last use of amphetamine, with a withdrawal syndrome involving two general phases that can last 3 weeks or more. The first phase of this syndrome is the initial "crash" that resolves within about a week (Gossop 1982;McGregor 2005) ...{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Adderall IR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. March 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ "Dexedrine Medication Guide" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. May 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ (2006). "Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory". Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 29: 565–598. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. PMID 16776597.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Nestler EJ (December 2012). "Transcriptional mechanisms of drug addiction". Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 10 (3): 136–143. doi:10.9758/cpn.2012.10.3.136. PMC 3569166. PMID 23430970.

ΔFosB has been linked directly to several addiction-related behaviors ... Importantly, genetic or viral overexpression of ΔJunD, a dominant negative mutant of JunD which antagonizes ΔFosB- and other AP-1-mediated transcriptional activity, in the NAc or OFC blocks these key effects of drug exposure14,22–24. This indicates that ΔFosB is both necessary and sufficient for many of the changes wrought in the brain by chronic drug exposure. ΔFosB is also induced in D1-type NAc MSNs by chronic consumption of several natural rewards, including sucrose, high fat food, sex, wheel running, where it promotes that consumption14,26–30. This implicates ΔFosB in the regulation of natural rewards under normal conditions and perhaps during pathological addictive-like states.

- ^ a b c d Steiner H, Van Waes V (January 2013). "Addiction-related gene regulation: risks of exposure to cognitive enhancers vs. other psychostimulants". Prog. Neurobiol. 100: 60–80. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.10.001. PMC 3525776. PMID 23085425.

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories (2 August 2013). "Alcoholism – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG Pathway. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ Pitchers KK, Frohmader KS, Vialou V, Mouzon E, Nestler EJ, Lehman MN, Coolen LM (October 2010). "ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens is critical for reinforcing effects of sexual reward". Genes Brain Behav. 9 (7): 831–840. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00621.x. PMC 2970635. PMID 20618447.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and addictive disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 384–385. ISBN 9780071481274.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hofmann FG (1983). A Handbook on Drug and Alcohol Abuse: The Biomedical Aspects (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 329. ISBN 9780195030570.

- ^ Advokat C (2007). "Update on amphetamine neurotoxicity and its relevance to the treatment of ADHD". J. Atten. Disord. 11 (1): 8–16. doi:10.1177/1087054706295605. PMID 17606768.

- ^ "Amphetamine". Hazardous Substances Data Bank. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

Direct toxic damage to vessels seems unlikely because of the dilution that occurs before the drug reaches the cerebral circulation.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "15". In Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 370. ISBN 9780071481274.

Unlike cocaine and amphetamine, methamphetamine is directly toxic to midbrain dopamine neurons.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sulzer D, Zecca L (February 2000). "Intraneuronal dopamine-quinone synthesis: a review". Neurotox. Res. 1 (3): 181–195. doi:10.1007/BF03033289. PMID 12835101.

- ^ Miyazaki I, Asanuma M (June 2008). "Dopaminergic neuron-specific oxidative stress caused by dopamine itself". Acta Med. Okayama. 62 (3): 141–150. PMID 18596830.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. December 2013. pp. 8–10. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1216: 86–98. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMID 21272013.

VMAT2 is the CNS vesicular transporter for not only the biogenic amines DA, NE, EPI, 5-HT, and HIS, but likely also for the trace amines TYR, PEA, and thyronamine (THYR) ... [Trace aminergic] neurons in mammalian CNS would be identifiable as neurons expressing VMAT2 for storage, and the biosynthetic enzyme aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Amphetamine VMAT2 pH gradientwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

GIRKwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Genatlas TAAR1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

EAAT3was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

DAT regulation reviewwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f "Amphetamine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ Maguire JJ, Davenport AP (19 April 2013). "TA1 receptor". IUPHAR database. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ Borowsky B, Adham N, Jones KA, Raddatz R, Artymyshyn R, Ogozalek KL, Durkin MM, Lakhlani PP, Bonini JA, Pathirana S, Boyle N, Pu X, Kouranova E, Lichtblau H, Ochoa FY, Branchek TA, Gerald C (July 2001). "Trace amines: identification of a family of mammalian G protein-coupled receptors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (16): 8966–8971. doi:10.1073/pnas.151105198. PMC 55357. PMID 11459929.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Amphetamine". PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ "Amphetamine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ Inazu M, Takeda H, Matsumiya T (August 2003). "[The role of glial monoamine transporters in the central nervous system]". Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi (in Japanese). 23 (4): 171–178. PMID 13677912.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Vicentic A, Lakatos A, Jones D (August 2006). "The CART receptors: background and recent advances". Peptides. 27 (8): 1934–1937. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2006.03.031. PMID 16713658.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lin Y, Hall RA, Kuhar MJ (October 2011). "CART peptide stimulation of G protein-mediated signaling in differentiated PC12 cells: identification of PACAP 6–38 as a CART receptor antagonist". Neuropeptides. 45 (5): 351–358. doi:10.1016/j.npep.2011.07.006. PMC 3170513. PMID 21855138.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Imperato A, Obinu MC, Gessa GL (July 1993). "Effects of cocaine and amphetamine on acetylcholine release in the hippocampus and caudate nucleus". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 238 (2–3): 377–381. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(93)90869-J. PMID 8405105.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Dickson SL, Egecioglu E, Landgren S, Skibicka KP, Engel JA, Jerlhag E (June 2011). "The role of the central ghrelin system in reward from food and chemical drugs". Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 340 (1): 80–87. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2011.02.017. PMID 21354264.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Stuber GD, Hnasko TS, Britt JP, Edwards RH, Bonci A (June 2010). "Dopaminergic terminals in the nucleus accumbens but not the dorsal striatum corelease glutamate". J. Neurosci. 30 (24): 8229–8233. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1754-10.2010. PMC 2918390. PMID 20554874.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Gu XL (October 2010). "Deciphering the corelease of glutamate from dopaminergic terminals derived from the ventral tegmental area". J. Neurosci. 30 (41): 13549–13551. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3802-10.2010. PMC 2974325. PMID 20943895.

- ^ a b c d Bidwell LC, McClernon FJ, Kollins SH (August 2011). "Cognitive enhancers for the treatment of ADHD". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 99 (2): 262–274. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2011.05.002. PMC 3353150. PMID 21596055.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lewin AH, Miller GM, Gilmour B (December 2011). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1 is a stereoselective binding site for compounds in the amphetamine class". Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19 (23): 7044–7048. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2011.10.007. PMC 3236098. PMID 22037049.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Revel FG, Moreau JL, Gainetdinov RR; et al. (May 2011). "TAAR1 activation modulates monoaminergic neurotransmission, preventing hyperdopaminergic and hypoglutamatergic activity". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (20): 8485–8490. doi:10.1073/pnas.1103029108. PMC 3101002. PMID 21525407.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Maguire JJ, Parker WA, Foord SM, Bonner TI, Neubig RR, Davenport AP (March 2009). "International Union of Pharmacology. LXXII. Recommendations for trace amine receptor nomenclature". Pharmacol. Rev. 61 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1124/pr.109.001107. PMC 2830119. PMID 19325074.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Levin ED, Bushnell PJ, Rezvani AH (August 2011). "Attention-modulating effects of cognitive enhancers". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 99 (2): 146–154. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2011.02.008. PMC 3114188. PMID 21334367.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Amphetamine". Pubchem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ "AMPHETAMINE". United States National Library of Medicine – Toxnet. Hazardous Substances Data Bank. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

Concentrations of (14)C-amphetamine declined less rapidly in the plasma of human subjects maintained on an alkaline diet (urinary pH > 7.5) than those on an acid diet (urinary pH < 6). Plasma half-lives of amphetamine ranged between 16-31 hr & 8-11 hr, respectively, & the excretion of (14)C in 24 hr urine was 45 & 70%.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ Richard RA (1999). "Chapter 5—Medical Aspects of Stimulant Use Disorders". National Center for Biotechnology Information Bookshelf. Treatment Improvement Protocol 33. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.