Bazaar

This is Wikipedia's current article for improvement – and you can help edit it! You can discuss how to improve it on its talk page and ask questions at the help desk or Teahouse. See the cheatsheet, tutorial, editing help and FAQ for additional information. Editors are encouraged to create a Wikipedia account and place this article on their watchlist.

Find sources: "Bazaar" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR |

A bazaar is a permanently enclosed marketplace or street where goods and services are exchanged or sold. The term originates from the Persian word bāzār. The term bazaar is sometimes also used to refer to the "network of merchants, bankers and craftsmen" who work in that area. Although the current meaning of the word is believed to have originated in native Zoroastrian Persia, its use has spread and now has been accepted into the vernacular in countries around the world. In Balinese, the word pasar, means "market." The capital of Bali province, in Indonesia, is Denpasar, which means "north market." Souq is another word used in the Middle East for an open-air marketplace or commercial quarter.

Evidence for the existence of bazaars dates to around 3,000 BCE. Although the lack of archaeological evidence has limited detailed studies of the evolution of bazaars, indications suggest that they initially developed outside city walls where they were often associated with servicing the needs of caravanserai. As towns and cities became more populous, these bazaars moved into the city center and developed in a linear pattern along streets stretching from one city gate to another gate on the opposite side of the city. Over time, these bazaars formed a network of trading centres which allowed for the exchange of produce and information. The rise of large bazaars and stock trading centres in the Muslim world allowed the creation of new capitals and eventually new empires. New and wealthy cities such as Isfahan, Golconda, Samarkand, Cairo, Baghdad and Timbuktu were founded along trade routes and bazaars. Street markets are the European and North American equivalents.

Shopping at a bazaar or market-place remains a central feature of daily life in many Middle-Eastern and South Asian cities and towns and the bazaar remains the "beating heart" of Middle-Eastern city and South Asian life. A number of bazaar districts have been listed as World Heritage sites due to their historical and/or architectural significance. Visiting a bazaar or souq has also become a popular tourist pastime.

Etymology and usage

The origin of the word bazaar comes from Persian bāzār.[1][2] from Middle Persian wāzār,[3] from Old Persian vāčar,[4] from Proto-Indo-Iranian *wahā-čarana.[5] The term, bazaar, spread from Persia into Arabia and ultimately throughout the Middle East.[6] Many languages have names to describe the concept of a bazaar, including Arabic and Template:Lang-ur, Kurdish language has the same word bazaar meaning a marketplace. Albanian, Bosnian and Template:Lang-tr, Template:Lang-as (bôzar), Template:Lang-bn (ba-zar or bazzar), Template:Lang-or, Bulgarian and Template:Lang-mk, Cypriot Greek: pantopoula,[7] Template:Lang-el (pazari), Template:Lang-hi, Template:Lang-hu (term originates from Persian influence around the 7th–8th century and means a regular market, but special occasion markets also exist, such as Karácsonyi Vásár or "Christmas Market", and bazár or Oriental-style market or shop, the term stemming from Turkish influence around the 16th–17th century), Indonesian and Template:Lang-ms, Template:Lang-hy, Georgian: ბაზარი, Template:Lang-pl, Template:Lang-ru, Template:Lang-uk and Template:Lang-uz, Template:Lang-ug, ULY: bazar, USY: базар.

In North America, the United Kingdom and some other European countries, the term can be used as a synonym for a "rummage sale", to describe charity fundraising events held by churches or other community organisations in which either donated used goods (such as books, clothes and household items) or new and handcrafted (or home-baked) goods are sold for low prices, as at a church or other organisation's Christmas bazaar, for example. In South Korea, the word '바자회',[8] composed of '바자' (transliteration of 'bazaar') + 회 (會, meaning 'gathering') is used to describe the sort of rummage sale described above.

Although Turkey offers many famous markets known as "bazaars" in English, the Turkish word "pazar" refers to an outdoor market held at regular intervals, not a permanent structure containing shops. English place names usually translate "çarşı" (shopping district) as "bazaar" when they refer to an area with covered streets or passages. For example, the Turkish name for the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul is "Kapalıçarşı" (gated shopping area), while the Spice Bazaar is the "Mısır Çarşısı" (Egyptian shopping area). The Arabic term, souk (souq or suk) is a synonym for bazaar.

Brief history

Bazaars originated in the Middle East, probably in Persia. Pourjafara et al., point to historical records documenting the concept of a bazaar as early as 3000 BC.[9] By the 4th century (CE), a network of bazaars had sprung up alongside ancient caravan trade routes. Bazaars were typically situated in close proximity to ruling palaces, citadels or mosques, not only because the city afforded traders some protection, but also because palaces and cities generated subtantial demand for goods and services.[10] Bazaars located along these trade routes, formed networks, linking major cities with each other and in which goods, culture, people and information could be exchanged.[11]

The Greek historian, Herodotus, noted that in Egypt, roles were reversed compared with other cultures and Egyptian women frequented the market and carried on trade, while the men remain at home weaving cloth.[12] He also described a The Babylonian Marriage Market.[13]

Prior to the 10th century, bazaars were situated on the perimeter of the city or just outside the city walls. Along the major trade routes, bazaars were associated with the caravanserai. From around the 10th century, bazaars and market places were gradually integrated within the city limits. The typical bazaar was a covered area where traders could buy and sell with some protection from the elements.[14] Over the centuries, the buildings that housed bazaars became larger and more elaborate. The Grand Bazaar in Istanbul is often cited as the world's oldest continuously-operating, purpose-built market; its construction began in 1455.

City bazaars occupied a series of alleys along the length of the city, typically stretching from one city gate to a different gate on the other side of the city. The bazaar at Tabriz, for example, stretches along 1.5 kilometres of street and is the longest vaulted bazaar in the world.[15] Moosavi argues that the Middle-Eastern bazaar evolved in a linear pattern, whereas the market places of the West were more centralised.[16]

In pre-Islamic Arabia, two types of bazaar existed: permanent urban markets and temporary seasonal markets. The temporary seasonal markets were held at specific times of the year and became associated with particular types of produce. Suq Hijr in Bahrain was noted for its dates while Suq 'Adan was known for its spices and perfumes. In spite of the centrality of the Middle East in the history of bazaars, relatively little is known due to the lack of archaeological evidence. However, documentary sources point to permanent marketplaces in cities from as early as 550 BCE.[17]

Nejad has made a detailed study of early bazaars in Iran and identifies two distinct types, based on their place within the economy, namely:[18]

- * Commercial bazaars (or retail bazaars): emerged as part of an urban economy not based on a merchant system

- * Socio-commercial bazaars: formed in economies based on a merchant system, socio-economic bazaars are situated on major trade routes and are well integrated into the city's structural and spatial systems

In the 1840s, Charles White described the Yessir Bazary of Constantinople in the following terms: [19]

- "The interior consists of an irregular quadrangle. In the center is a detached building, the upper portion serving as a lodging for slavedealers, and underneath are cells for newly imported slaves. To this is attached a coffee-house, and near to it a half-ruined mosque. Around the three habitable sides of the court runs an open colonnade, supported by wooden columns, and approached by steps at an angle. Under the colonnade are platforms, separated from each other by low railings and benches. Upon these, dealers and customers may be seen during business hours smoking and discussing prices.

- Behind these platforms are ranges of small chambers, divided into two compartments by a trellice-work. The habitable part is raised about three feet from the ground; the remainder serves as passage and cooking place. The front portion is generally tenanted by black, and the rear by white slaves. These chambers are exclusively devoted to females. Those to the north and west are destined for second hand negresses or white women – that is, for slaves who have been previously purchased and instructed, and are sent to be resold. The hovels to the east are reserved for newly imported negresses, or black and white women of low price.

- The platforms are divided from the chambers by a narrow alley, on the wall side of which are benches, where women are exposed for sale. This alley serves as a passage of communication and walk for the brokers, who sell slaves by auction and on commission. In this case, the brokers walk around, followed by the slaves, and announce the price offered. Purchasers, seated on the platforms, then examine, question and bid, as suits their fancy, until at length the woman is sold or withdrawn."

In the Middle East, the bazaar is considered to be "the beating heart of the city and a symbol of Islamic architecture and culture of high significance."[20] Today, bazaars are popular sites for tourists and some of these ancient bazaars have been listed on world heritage sites on the basis of their historical, cultural or architectural value. The Bazaar complex at Tabriz, Iran was listed as a World Heritage site with UNESCO in 2010.[21] The Medina at Fez, Morocco, with its labyrinthine covered market streets was also listed in 1981.[22] Al-Madina Souq is part of the ancient city of Aleppo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1986.[23]

In art and literature

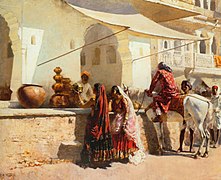

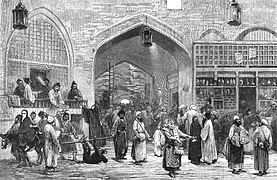

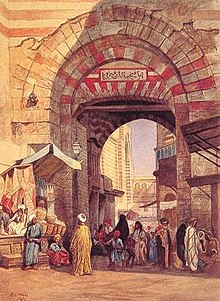

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Europeans conquered and excavated parts of North Africa and the Levant. These regions now make up what is called the Middle East, but in the past were known as the Orient. Europeans sharply divided peoples into two broad groups – the European West and the East or Orient; us and the other. Europeans often saw Orientals as the opposite of Western civilisation; the peoples could be threatening- they were "despotic, static and irrational whereas Europe was viewed as democratic, dynamic and rational."[24] At the same time, the Orient was seen as exotic, mysterious, a place of fables and beauty. This fascination with the other gave rise to a genre of painting known as Orientalism. Artists focussed on the exotic beauty of the land – the markets, caravans and snake charmers. Islamic architecture also became favourite subject matter. European society generally frowned on nude painting – but harems, concubines and slave markets, presented as quasi-documentary works, satisfied European desires for pornographic art. The Oriental female wearing a veil was a particularly tempting subject because she was hidden from view, adding to her mysterious allure.[25]

French painter Jean-Étienne Liotard visited Istanbul in the 17th century and painted pastels of Turkish domestic scenes. British painter John Frederick Lewis who lived for several years in a traditional mansion in Cairo, painted highly detailed works showing realistic genre scenes of Middle Eastern life. Edwin Lord Weeks was a notable American example of a 19th-century artist and author in the Orientalism genre. His parents were wealthy tea and spice merchants who were able to fund his travels and interest in painting. In 1895 Weeks wrote and illustrated a book of travels titled From the Black Sea through Persia and India. Other notable painters in the Orientalist genre who included scenes of street life and market-based trade in their work are Jean-Léon Gérôme Delacroix (1824–1904), Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps (1803–1860), Frederic Leighton (1830–1896), Eugène Alexis Girardet 1853–1907 and William Holman Hunt (1827–1910), who all found inspiration in Oriental street scenes, trading and commerce.[26]

A proliferation of both Oriental fiction and travel writing occurred during the early modern period.[27] British Romantic literature in the Orientalism tradition has its origins in the early eighteenth century, with the first translations of The Arabian Nights (translated into English from the French in 1705–08). The popularity of this work inspired authors to develop a new genre, the Oriental tale. Samuel Johnson's History of Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia, (1759) is mid-century example of the genre.[28] Byron's Oriental Tales, is another example of the Romantic Orientalism genre.[29]

Many English visitors to the Orient wrote narratives around their travels. Although these works were purportedly non-fiction, they were notoriously unreliable. Many of these accounts provided detailed descriptions of market places, trading and commerce.[30] Examples of travel writing include: Les Mysteres de L'Egypte Devoiles by Olympe Audouard published in 1865[31] and Jacques Majorelle's Road Trip Diary of a Painter in the Atlas and the Anti-Atlas published in 1922[32]

- Selected paintings & watercolours with bazaar scenes as subject matter

-

Marriage Procession in a Bazaar, unknown, 1645

-

Silk Mercers' Bazaar, Cairo by David Roberts, Cairo, 1838

-

Bazaar El Moo Ristan, by David Roberts, 1838

-

Bazaar of the Coppersmiths by David Roberts, 1838

-

The Bazaar, by Alexandre Defaux, 1856

-

Dans le Souk aux Cuivres by Nicola Forcella, before 1868

-

Bazaar by Vasily Vereshchagin, c. 1870

-

Copper Market, Cairo by Edward Angelo Goodall, 1871

-

A Market in Isphahan by Edwin Lord Weeks, 1887

-

The Metalsmiths Shop, Edwin Lord Weeks, late 19th century

-

Moroccan Market, Rabat, by Edwin Lord Weeks, 1880

-

Cashmere Travellers in a Street of Delhi by Edwin Lord Weeks 1880

-

Grain Market in Fez by Jules Pierre van Biesbroeck, undated

-

Moroccan Market Scene by Louis Comfort Tiffany, undated

-

A Bazaar, Oil painting, Wellcome

-

Vendors in the Covered Bazaar Istanbul by Vittorio Amadeo Preziosi,1851

-

A Turkish Bazaar by Amadeo Preziosi, 1854

-

The Spice Sellers by Vittorio Amadeo Preziosi, 19th century

-

Figures in the Bazaar Constantinople, by Amedeo Preziosi, 19th century

-

The Silk Bazaar by Amedeo Preziosi, late 19th century

-

Bazaar by Otto Heyden, 1869

-

Nizhny Novgorod, Lower Bazaar by Alexey Bogolyubov, 1878

-

Souk at Konstantynopolu by Stanisław Chlebowski, 19th century

-

Inside the Souk, Cairo by Charles Wilda, 1892

-

Bazaar in Samarkand, by Gigo Gabashvili, 1896

-

The Barber at the Souk by Enrique Simonet, 1897

-

The Tentmakers' Bazaar, Cairo, 1907

-

Souk Silah, the Armourers' Bazaar, Cairo, from D.S. Margoliouth, Cairo, Jerusalem, & Damascus: three chief cities of the Egyptian Sultans, 1907

-

People on the Street of a Bazaar at Midan El-Adaoui from D.S. Margoliouth, Cairo, Jerusalem, & Damascus: three chief cities of the Egyptian Sultans, 1907

-

Bazaar at the Souk Hamareh, Damascus by from D.S. Margoliouth, Cairo, Jerusalem, & Damascus: three chief cities of the Egyptian Sultans, 1907

-

Bazaar with Bagels by Ivan Koulikov, 1910

-

The Silk Bazaar, Damascus – Australians buying goods, 1918

-

Scenery at a North African Bazaar, by John Gleich, 20th century

-

The Bazaar at Constantinople, watercolour by J. F. Lewis, Wellcome

-

The Char-Chatta Bazaar of Kabul by A. Gh. Brechna, 1932

-

Bazaar in the Old City, by Ludwig Blum, 1944

Examples

Albania

In Albania, two distinct types of bazaar can be found; Bedesten (also known as bezistan, bezisten, bedesten) which refers to a covered bazaar and an open bazaar.

- Bazaar of Pristina, Kosovo

- Bazaar of Peć, Kosovo

- Pazari i Ri, Tirana

- The Old Bazaar, Gjakova

- The Old Bazaar of Korçë

- Kruje Bazaar

Australia

- Ingleburn Bazaar (held annually during the Ingleburn Festival)

Afghanistan

- Shah Bazaar, Kandahar

- Shor Bazaar, Kabul

- Grand Bazaar, Herat

- Mazari Bazaar, Mazari Sharif

- Olander Bazaar, Yllib, Kandahar

-

City of Kandahar, its principal bazaar and citadel, taken from the Nakkara Khauna from Lieutenant James Rattray, Afghanistan

-

An Afghan elder sits outside his store at the Anaba bazaar in Panjshir, Afghanistan

-

Ka Foroshi, the bird market in Kabul

- Khan Bazar, Khankendi

- Kolkhoz (or Merkezi) Bazaar (Kolkhoz (Central) Bazaar), Sumgait

- Kohna Bazaar (Old Bazaar), Ganja

- Ortulu Bazar, Shamakhi

- Sharq Bazaar (East Bazaar), Baku

- Sharq Bazaar (East Bazaar), Sumgait

- Pasaj Bazary, Aghdam

- Teze Bazar (New Bazaar), Baku

- 8 Kilometre Bazaar, Baku

- Yashil Bazar (Green Bazaar), Baku

- Yeni Bazar, Shaki, Azerbaijan

- Zanbil Bazar (Basket Bazaar), Nakhchivan

-

Big Bazaar, Lankaran, Azerbaijan

Bangladesh

In Nepal, India and Bangladesh, a Haat bazaar (also known as hat or haat or hatt) refers to a regular produce market, typically held once or twice per week.[33]

- Amin Bazaar, Dhaka

- Bhairab Bazaar, Kishoreganj District

- Badshahi Chawk Bazaar (also known as Chowk Bazaar), Dhaka

- Dasherjangal Bazaar, Shariatpur District

- Jalchatra Bazaar, Bangladesh

- Kachukhet Bazaar, Dhaka

- Karwan Bazaar, Dhaka

- Kazir Dewri, Chittagong

- New Market Kacha Bazaar, Dhaka

- Malibagh Bazaar, Dhaka

- Banani Bazaar, Dhaka

- Khilkhet Kacha Bazaar, Dhaka

- Mohakhali Bazaar, Dhaka

- Moulvibazar, Moulvibazar Sadar Upazila, Moulvibazar District

- Shanti Nagar Bazaar, Dhaka

-

Dhaka Town Chowk, 1904

-

Basantapur Bazaar Chowk at Madhi, Chitwan

Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Baščaršija, Sarajevo

- Kujundžiluk, Mostar

China

- Grand Bazaar, Urumuqi, Xinjiang

- Monday Bazaar, Upal, Xinjiang

- Sunday Bazaar, Kashgar, Xinjiang

Egypt

-

Two Egyptian women shopping at a market next to the Al-Ghouri Complex in Cairo, Egypt.

-

Khan el khalili, Cairo (interior)

-

Khan al-khalili, bab al-qutn (gate)

-

Shop of a Turkish Merchant in Kha'n El-Khalee'lee, 1836

-

Arabic Window and Native Bazaar, Cairo

Hong Kong

Israel

- Old City of Jerusalem – there are many Bazaars in the Christian, Muslim and Jewish Quarters. the Armenian one does not include Bazaar of its own.

- Mahane Yehuda, Central Jerusalem

- Old Acre, Israel City of Acre

- Old City of Nazareth Bazaar

India

In India, and also Pakistan, a town or city's main market is known as a Saddar Bazaar.

These are mutually agreed border bazaars and haats of India on borders of India with its neighbours.

- Paltan Bazaar Assam

- Pan Bazaar Guwahati, Assam

- Uzan Bazaar Guwahati, Assam

- Gandhi Bazaar, Bangalore

Chennai, Tamil Nadu

- Burma Bazaar, Chennai

- Pondy Bazaar, Chennai

- In Delhi

- Arul Bazar, Delhi

- Chandni Chowk, Delhi

- Chawri Bazaar, Delhi (wholesale market)

- Chhota Bazaar Shahdara, Dehli

- Dilli Haat, Dehli – A Haat is a regular open-air produce market

- Khan Market, Delhi

- Meena Bazaar, Delhi

- Palika Bazaar, Delhi

- Sadar Bazaar, Delhi

- Urdu Bazaar (Delhi)

- In National Capital Region (NCR)

- Begum Bazar, Hyderabad

- Chatta Bazaar, Hyderabad, India

- Laad Bazaar, Hyderabad, India

- Shahran Bazaar, Hyderabad

- Sultan Bazar, Hyderabad

- Rythu bazaar, Telangana

- Sarafa Bazaar, Indore, India

Kashmir

- Boi Bazar-Kashmir-Point Kashmir(Pakistan Administered Kashmir)/Pakistan border

Kerala, Keralam

- Chala Bazaar, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala

- Rice Bazaar Thrissur, Kerala

- Burra Bazar, Kolkata

- Bowbazar, Kolkata

- Tiretta Bazaar, Kolkata

- Bhendi Bazaar Mumbai

- Bhindi Bazaar, South Mumbai

- Chor Bazaar, Mumbai

- Zaveri Bazaar, Mumbai

- Bari Bazaar, Munger

- Bhubaneswar Bazaar, Unit-1 BadaMarket, Bhubaneswar

- Gole Bazaar, Sambalpur

- Choudhury Bazaar, Cuttack

- Nua Bazaar, Cuttack

- Chaura Bazaar Ludhiana, Punjab

- Chess Bazaar, Mohali, Punjab

- Aminabad Bazaar Luknow, Uttar Pradesh

- Bada Bazaar, Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh

- Hooseinabad Bazaar, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh

- Lalganja Bazaar, Uttar Pradesh

- Meena Bazaar Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh

- Purani Najhai, Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh

- Sabzi Bazaar, Shihura Khurd Kalan, Uttar Pradesh

- Sadar Bazaar, Agra, Uttar Pradesh

- Sarafa Bazaar, Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh

-

Women purchasing copper utensils in a bazaar by Edwin Lord Weeks, late 19th century

-

Almora Bazaar, Uttarakhand, c1860

-

Laad Bazaar near Charminar, Hyderabad, India

-

Paltan Bazaar, Assam, India

-

Cheh Tuti Chowk or Six Tuti Chowk, Main Bazaar, Paharganj

-

Gateway to Hooseinabad Bazaar, Lucknow, c. 1863

-

Bazaar along Kalbadevie Road, Bombay (now Mumbai), 1890

-

Antiques and old posters at Chor Market in Mumbai

Indonesia

Iran

- Ardabil Bazaar

- Bazaar of Borujerd

- Bazaar of Tabriz in Tabriz – an historic site that originally developed along the ancient silk routes; listed as a World Heritage Site[34]

- Isfahan Bazaar in Isfahan – historic site which dates to Safavid era.[35]

- Behjat Abad Market, Tehran

- Caravanserai of Sa'd al-Saltaneh Qazvin, Iran

- Ganjali Khan Complex, Kerman, Iran

- Kashan Bazaar in Kashan

- Khan Bazaar, Yazd

- Kerman Bazaar, Kerman

- Kermanshah Bazaar, Kermanshah

- Kohneh Bazaar, Abadeh

- Qeysarie Bazaar Bazaar, Isfahan

- Tajrish, Shemiranat County, Tehran Province, Iran

- Tehran Bazaar, Tehran

- Sanandaj Bazaar, Sanandaj

- Saraye Moshir, Shiraz, Southern Iran

- Vakil Bazaar, Shiraz

- Amol Bazaar in Amol

-

Mozaffarieh: An alley in Tabriz Bazaar devoted to carpet selling

-

Bazaar in old Tehran, 1873

-

Vakil Bazaar from Jane Dieulafoy, Perzië, Chaldea en Susiane, 1881

-

Vakil Bazaar

-

Bazar of Kashan by Pascal Coste, 1840

-

Bazaar ofe Kashan, Kashan, Irán

-

Caravanserai of Sa'd al-Saltaneh

-

Bazaar de Teherán, Teherán, Irán

Kazakhstan

Kuwait

- Souq Almubarikiyya * Souq Avenues

Kurdistan

A Qaysari Bazaar is a type of covered bazaar typical of Kurdistan and Iraq.

Kyrgyzstan

Lebanon

After sustaining irreparable damage during the country's civil war, Beirut's ancient souks have been completely modernised and rebuilt while maintaining the original ancient Greek street grid, major landmarks and street names.

- Bazaars and Souks of Old Cities of Tripoli – The ancient city of Tripoli has two separate old towns, both of which have large, well preserved souks, bazaars and khans of various specialties.

- Souk of Old Quarter of Byblos

- Souk of Old Quarter of Jounieh

- Souk of Old Quarter of Aley

- Bazaars and Souks of Old City of Sidon – The ancient, Southern city of Sidon has a large and well preserved old town that is divided into the Muslim, Christian and Jewish quarters, each of which contains souks, bazaars and khans of various specialties.

- Souk of Old City of Tyre

- Beirut Souks

Macedonia

In the Balkans, the term, 'Bedesten' is used to describe a covered market or bazaar.

- Old Bazaar, Bitola

- Old Bazaar, Prilep

- Old Bazaar, Skopje

- Old Bazaar, Tetovo

-

The Bazaar

-

Belgrade street

-

The Bazaar

-

Street stairs

-

A street

-

A street

-

The entrance to the Bezisten

-

The Bezisten

-

The Bazaar by night

Malaysia

- Bukit Beruang Bazaar, Malacca

- Bazar Bukakbonet Gelang Patah, Johor Bahru

Nepal

- Asan, Kathmandu ceremonial bazaar and square

- Bishal Bazaar, Pokhara

- Gaushala Bazar, Mahottari District

- Khaireni, Gulmi District

- Namche Bazaar, Namche

- Purano Bazaar, KTM

- Naya Bazaar, KTM

- Newari bazaar

- Shyauli Bazaar Gandaki, Nepal

Norway

- Oslo Bazaars – a protected site

Pakistan

Hyderabad, Pakistan

- Shahi Bazaar, Hyderabad

- Sarafa Bazaar, Hyderabad

- Saddar (Hyderabad) in Pakistan

- Resham Bazaar, Hyderabad

- Saddar (Hyderabad) in Pakistan

Karachi

- Bohri Bazaar, Karachi

- Jodia Bazaar, Karachi

- Saddar in Karachi

- Sarafa Bazaar, Karachi

- Meena Bazaar, Karachi

- Soldier Bazaar, Karachi

- Tariq Road Bazaar, Karachi

- Urdu Bazaar, Karachi

- Zainab Market, Karachi

Lahore

- Anarkali Bazaar, Lahore

- Mochi Gate Bazaars, Walled City of Lahore

- Naulakha Bazaar, Lahore

- Naranki Bazaar[36]

- Raja Bazaar

- Urdu Bazaar, Lahore

Peshawar

Punjab, Pakistan

- Chakdina Bazaar, Kharian Tehsil of Gujrat District, Punjab, Pakistan

- Chotaka Bazaar, Multan District

- Chowk Bazaar, Multan

- Moti Bazaar, Rawalpindi, Punjab

- Multani Bazaar, Multan District

- Rail Bazaar, Multan District

- Raja Bazaar, Rawalpindi

- Rasheed Shah Bazaar, Multan District

- Saddar in Karachi (Saddar bazaar refers to a main or central bazaar)

- Saddar, Rawalpindi

- Sarafa Bazaar, Rawalpindi

- Rawalpindi bazaars

- Urdu Bazaar, Rawalpindi, Punjab

- Urdu Bazaar, Multan

Rajdhani

Sargodha

-

Qissa Khwani Bazaar, Peshawar, Pakistan

-

Bazaar, Karachi, Pakistan

-

Rawalpindi Bazaar, Rawalpindi, Punjab

Serbia

- New Bazar, Novi Pazar

South Africa

- Marabastad, Pretoria also known as Asiatic Bazaar, Pretoria, South Africa

Sri Lanka

- Madawala Bazaar

Syria

- Al-Buzuriyah Souq in Damascus

- Al-Hamidiyah Souq in Damascus

- Souq Atwail in Damascus

- Souq Al Buzria in Damascus

- Mathaf Al Sulimani in Damascus

- Midhat Pasha Souq in Damascus

- Souq Al-Attareen (Perfumers' Souq) in Aleppo

- Souq Khan Al-Nahhaseen (Coopery Souq) in Aleppo

- Souq Al-Haddadeen (Blacksmiths' Souq) in Aleppo

- Suq Al-Saboun (Soap Souq) in Aleppo

- Suq Al-Atiq (the Old Souq) in Aleppo

- Al-Suweiqa (Suweiqa means "small souq" in Arabic) in Aleppo

- Suq Al-Hokedun (Hokedun means "spiritual house" in Armenian) in Aleppo

-

The Fruit Bazaar, Damascus, painting by Margaret Thomas and reproduced in John E. Kelman, From Damascus to Palmyra, 1908

-

The Silk Bazaar, Damascus – Australians buying goods, 1918

-

Entrance to the Bazaar, Gaza

-

The Bazaar of El Harish, 1881

Tanzania

- Darajani Market also known as Darajani Bazaar

Tunisia

Turkmenistan

- Gulistan Bazaar, (also known as the Russian Bazaar) Ashgabat

- Altyn Asyr Bazaar, Ashgabat (formerly Tolkuchka bazaar)

-

Altyn Asyr Bazaar, Turkmenistan

Turkey

In Turkey, the term 'bazaars' is used in the English sense, to refer to a covered market place. In Turkish the term for bazaar is "çarşı."

- Arasta Bazaar, Istanbul

- Eminönü Istanbul

- Grand Bazaar, Istanbul

- Spice Bazaar, Istanbul

- Kemeraltı, İzmir

- Mahmutpaşa Bazaar, Istanbul

- Silk Bazaar, Bursa

- Uzun Carsi (The Long Bazaar), Bursa

- Acik Carsi (The Openair Bazaar), Bursa

-

Kemeraltı (bazaar district), İzmir, Turkey

-

Arasta Bazaar, Istanbul

-

Grand Bazaar, Istanbul

-

Spice Bazaar,Istanbul

Belarus

Uzbekistan

- Alay Bazaar, Tashkent

- Chorsu Bazaar, Tashkent[37]

- Chorsu (Samarkand)

- Siyob Bazaar, Samarkand

- Mirobod Bazaar, Tashkent

See also

- Arcade – a covered passageway with stores along one or both sides.

- Bazaari

- Bedesten (also known as bezistan, bezisten, bedesten) refers to a covered bazaar and an open bazaar in the Balkans.

- Covered Market, Oxford, England

- Gold Souq – a market trading in gold.

- Haat bazaar – (also known as a hat) an open air bazaar or market in South Asia

- Landa bazaar – a terminal market or market for second hand goods (South Asia)

- List of Orientalist artists

- Market

- Meena Bazaar – a bazaar that raises money for non-profit organisations

- Merchant

- Pasar malam – a night market in Indonesia, Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore that opens in the evening, typically held in the street in residential neighbourhoods.

- Pasar pagi – a morning market, typically a wet market that trades from dawn until midday, found in Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore

- Peddler

- Retail

- Shopping mall

- Souq – a term for bazaar or market place in Arabic speaking countries

- Tabriz Bazaar, Tabriz, Iran – the largest covered bazaar in the world

- Wet market – sells fresh meat, fish, and produce. See also Dry goods

References

- ^ "bazaar - Origin and meaning of bazaar by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ Ayto, John (1 January 2009). Word Origins. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-4081-0160-5.

- ^ Daryaee, Touraj (16 February 2012). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19-973215-9.

- ^ "Bazaar". Dictionary.com, LLC. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Benveniste, Émile; Lallot, Jean (1 January 1973). "Chapter Nine: Two Ways of Buying". Indo-European Language and Society. University of Miami Press. Section Three: Purchase. ISBN 978-0-87024-250-2.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/bazaar

- ^ Christou, Jean, "Linguist makes the island a little smaller for all", Cyprus Mail, May 27, 2006 Archived March 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "바자회 : 네이버 영어사전" (in Template:Ko icon). Endic.naver.com. Retrieved 2018-03-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Pourjafara, M., Aminib, M., Varzanehc, and Mahdavinejada, M., "Role of bazaars as a unifying factor in traditional cities of Iran: The Isfahan bazaar," Frontiers of Architectural Research, Vol. 3, No. 1, March 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2013.11.001, pp 10–19; Mehdipour, H.R.N, "Persian Bazaar and Its Impact on Evolution of Historic Urban Cores: The Case of Isfahan," The Macrotheme Review [A multidisciplinary Journal of Global Macro Trends], Vol. 2, no. 5, 2013, p.13

- ^ Harris, K., "The Bazaar" The United States Institute of Peace, <Online: http://iranprimer.usip.org/resource/bazaar>

- ^ Hanachi, P. and Yadollah, S., "Tabriz Historical Bazaar in the Context of Change," ICOMOS Conference Proceedings, Paris, 2011

- ^ Thamis, "Herodotus on the Egyptians." Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 18 Jan 2012. Web. 20 Aug 2017.

- ^ Herodotus: The History of Herodotus, Book I (The Babylonians), c. 440BC, translated by G.C. Macaulay, c. 1890

- ^ Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012 pp 14–15

- ^ Mehdipour, H.R.N, "Persian Bazaar and Its Impact on Evolution of Historic Urban Cores: The Case of Isfahan," The Macrotheme Review [A multidisciplinary Journal of Global Macro Trends], Vol. 2, no. 5, 2013, p.14

- ^ Moosavi, M. S. Bazaar and its Role in the Development of Iranian Traditional Cities [Working Paper], Tabriz Azad University, Iran, 2006

- ^ Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012, pp 4–5

- ^ Nejad, R. M., “Social bazaar and commercial bazaar: comparative study of spatial role of Iranian bazaar in the historical cities in different socio-economical context,” 5th International Space Syntax Symposium Proceedings, Netherlands: Techne Press, D., 2005,

- ^ Cited in: Stewart, F., Shackles of Iron: Slavery Beyond the Atlantic: Critical Themes in World History, 2016

- ^ Karimi, M., Moradi, E. and Mehr, R., "Bazaar, As a Symbol of Culture and the Architecture of Commercial Spaces in Iranian-Islamic Civilization,"

- ^ UNESCO, Tabriz Historic Bazaar Complex, http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1346

- ^ UNESCO, Medina of Fez, http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/170

- ^ "eAleppo:Aleppo city major plans throughout the history" (in Arabic).

- ^ Nanda, S. and Warms, E.L., Cultural Anthropology, Cengage Learning, 2010, p. 330

- ^ Nanda, S. and Warms, E.L., Cultural Anthropology, Cengage Learning, 2010, pp 330–331

- ^ Davies, K., Orientalists: Western Artists in Arabia, the Sahara, Persia, New York, Laynfaroh, 2005; Meagher, J., "Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art," [The Metropolitan Museum of Art Essay], Online: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/euor/hd_euor.htm

- ^ Houston, C., New Worlds Reflected: Travel and Utopia in the Early Modern Period, Routledge, 2016

- ^ The Norton Anthology of English Literature, https://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/romantic/topic_4/welcome.htm

- ^ Kidwai, A.R., Literary Orientalism: A Companion, New Delhi, Viva Books, 2009, ISBN 978-813091264-6

- ^ MacLean, G., The Rise of Oriental Travel: English Visitors to the Ottoman Empire, 1580–1720, Palgrave, 2004, p. 6

- ^ Audouard, O. (de Jouval), Les Mystères de l'Égypte Dévoilés, (French Edition) (originally published in 1865), Elibron Classics, 2006

- ^ Marcilhac, F., La Vie et l'Oeuvre de Jacques Majorelle: 1886–1962, [The Orientalists Volume 7], ARC Internationale edition, 1988.

- ^ Crow, B., Markets, Class and Social Change: Trading Networks and Poverty in Rural South Asia, Palgrave, 2001, [Glossary] p. xvii

- ^ Ahour, I., which dates to saljuqid era 11th century. its extension occurred in the safavid and kajar era. it is largest roofed bazar of the world. "The Qualities of Tabriz Historical Bazaar in Urban Planning and the Integration of its Potentials into Megamalls," Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 199–215, 2011, and for a contemporary account of the Bazaar see: Le Montagner, B., "Strolling through Iran's Tabriz Bazaar," The Guardian, 12 November 2014 <Online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/iran-blog/gallery/2014/nov/12/-sp-tabriz-historic-bazaar-iran-pictures>

- ^ Assari, A., Mahesh, T.M., Emtehani, M.E. and Assari, E., "Comparative Sustainability of Bazaar in Iranian Traditional Cities: Case Studies of Isfahan and Tabriz," International Journal on “Technical and Physical Problems of Engineering”, Vol. 3, no. 9, 2011, pp 18–24; Iran Chamber of Commerce, <Online: http://www.iranchamber.com/architecture/articles/bazaar_of_isfahan1.php#sthash.BB3fHqgx.dpuf>

- ^ Abbas, K., "Reacquainting with history: Narankari – a bazaar with a past, but no future," The Express Tribune, (Pakistan), 14 January, 2014, Online: https://tribune.com.pk/story/658731/reacquainting-with-history-narankari-a-bazaar-with-a-past-but-no-future/

- ^ "Bazaars of Uzbekistan". Goldensteppes.com. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

Further reading

- The Persian Bazaar: Veiled Space of Desire (Mage Publications) by Mehdi Khansari

- The Morphology of the Persian Bazaar (Agah Publications) by Azita Rajabi.

- Assari, Ali; T.M.Mahesh (December 2011). "Compararative Sustainability of Bazaar in Iranian Tradditional Cities: Case Studies in Isfahan and Tabriz" (PDF). International Journal on Technical and Physical Problems of Engineering. 3 (9): 18–24. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

External links

- Iran Chamber Society on Architecture of the Bazaar at Isfahan

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 559.