Boeing 737 MAX groundings

A parking lot at Boeing Field in Seattle, Washington, filled with undelivered Boeing 737 MAX aircraft | |

| Date |

|

|---|---|

| Duration | Ongoing. 5 years, 5 months and 11 days (since March 10, 2019) |

| Cause | Precautionary measure following two similar crashes less than five months apart |

| Deaths | 346:

|

In March 2019, aviation authorities and airlines around the world grounded the Boeing 737 MAX passenger airliner after two MAX 8 aircraft crashed, killing all 346 people aboard. The accidents befell Lion Air Flight 610 on October 29, 2018 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 on March 10, 2019. Ethiopian Airlines was first to ground its MAX fleet, effective the day of its accident, and one day later, March 11, China's Civil Aviation Administration ordered the first regulatory grounding. Most other agencies and airlines followed suit over the next two days. The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) initially reaffirmed airworthiness of the MAX on March 11, but grounded it on March 13. The groundings affected 387 MAX aircraft serving 8,600 weekly flights for 59 airlines.

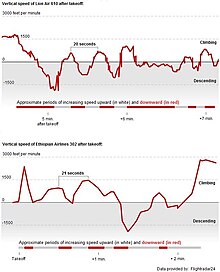

In each accident, the aircraft experienced repeated nose dives and crashed soon after takeoff. Unofficially, the cause is attributed to the airplane's new automated flight control, the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), acting on erroneous angle of attack (AoA) data to force the aircraft down. Pilots were unaware of MCAS, which Boeing did not describe in the airplane manuals. In November 2018, in response to the first accident, Boeing issued a service bulletin referring pilots to an existing recovery procedure, and the FAA issued an emergency airworthiness directive mandating revisions to the crew manual. Boeing began changes to the MCAS software, flight control computer system and cockpit displays. In April 2019 the company admitted that MCAS was activated in both accidents.

After the second accident, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) and Congress launched investigations into FAA type certification of the MAX, particularly the FAA's delegation of authority to Boeing, allowing it to self-certify a significant amount of its own work. A U.S.-international group formed by the FAA, the Joint Authorities Technical Review (JATR), investigated FAA approval of MCAS and found inadequate safety assessments. The JATR criticized the FAA's incomplete understanding of MCAS and how human factors interacted with automation. In September 2019, the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) faulted Boeing's assumptions that any pilot could quickly counter MCAS by using existing flight control procedures.

Boeing suspended deliveries and reduced production of the MAX, and airlines canceled thousands of flights that used the aircraft. After repeated delays in recertification, several airlines, including in the U.S. and Canada, announced MAX flights would not resume until early 2020. As of September 2019, the grounding cost Boeing up to $8 billion in revenue and compensation to airlines and bereaved families. Boeing also faced lawsuits from airline pilots and families of victims.

Accidents

Lion Air Flight 610

On October 29, 2018, Indonesian Lion Air Flight 610 from Soekarno–Hatta International Airport in Jakarta to Depati Amir Airport in Pangkal Pinang crashed into the Java Sea 12 minutes after takeoff. All 189 passengers and crew were killed in the accident.[1][2][3] The preliminary report tentatively attributed the accident to the erroneous angle-of-attack data and automatic nose-down trim commanded by MCAS.[4][5] The defective angle-of-attack vane was a "dubious" used part that had been replaced on the captain's side.[6] The 737 MAX aircraft was delivered 2 months and 16 days prior, on August 13, 2018. This is the deadliest crash involving the Boeing 737 regardless of variant.[7]

Boeing published a supplementary service bulletin addressing the AoA warning and the pitch system's potential for repeated activation, all without referring to MCAS by name. The bulletin describes warnings triggered by erroneous AoA data, and referred pilots to a "non-normal runaway trim" procedure as resolution, specifying a narrow window of a few seconds before the system's next application.[8] The FAA issued an Emergency airworthiness directive 2018-23-51, requiring the bulletin's inclusion in the flight manuals, and that pilots immediately review the new information provided.[9][10]

Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302

On March 10, 2019, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 from Addis Ababa in Ethiopia to Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi, Kenya, crashed six minutes after takeoff near Bishoftu, killing all 157 passengers and crew aboard the aircraft.[11][12][12][13][14] The 737 MAX was delivered 3 months and 23 days prior, on November 15, 2018, two weeks after the Lion Air accident.[15]

Initial reports indicated that the Flight 302 pilot struggled to control the airplane, in a manner similar to the circumstances of the Lion Air crash.[16] A stabilizer trim jackscrew found in the wreckage was set to put the aircraft into a dive.[17] Experts suggested this evidence further pointed to MCAS as at fault in the crash.[18][19] After the crash of flight ET302, Ethiopian Airlines spokesman Biniyam Demssie said in an interview that the procedures for disabling the MCAS were just previously incorporated into pilot training. "All the pilots flying the MAX received the training after the Indonesia crash," he said. "There was a directive by Boeing, so they took that training."[20] Despite following the procedure, the pilots could not recover.[21]

Ethiopia's transportation minister, Dagmawit Moges, said that initial data from the recovered flight data recorder of Ethiopian Flight 302 shows "clear similarities" with the crash of Lion Air Flight 610.[22][23] However, the main cause of the accidents is still[when?] under investigation and not yet fully determined.

Groundings

Voluntarily grounded by all operating airlines

Ethiopian Airlines grounded its fleet on March 10.[24] The Civil Aviation Administration of China ordered all MAX aircraft grounded in the country on March 11, stating its zero tolerance policy and the similarities of the crashes. Most other regulators and airlines individually grounded their fleets in the next two days.[24][25][26][27]

On March 11, the FAA issued a Continued Airworthiness Notification to the International Community (CANIC) for operators. The CANIC set out the activities the FAA had completed after the Lion Air accident in support of continued operations of the MAX and listed the 59 affected operators of 387 MAX aircraft around the world.[28][29][30]

On March 13, Canada received new information suggesting similarity between the crashes in Ethiopia and Indonesia. Canadian Transport Minister Marc Garneau informed U.S. Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao of his decision to ground the aircraft. Hours later, President Trump announced U.S. groundings, following consultation among Chao, acting FAA administrator Daniel Elwell and Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg. The FAA issued an official grounding order, citing the new evidence and acknowledging the "possibility of a shared cause for the two incidents".[31][32] The U.S., Canadian, and Chinese regulators oversee a combined fleet of 196 aircraft, more than half of all 387 airplanes delivered.[33]

Impact on airborne flights

Upon groundings

About 30 Boeing 737 MAX aircraft were flying in U.S. airspace when the FAA grounding order was announced. The airplanes were allowed to continue to their destinations and were then grounded.[34] In Europe, several flights were diverted when grounding orders were issued.[35][36] For example, an Israel-bound Norwegian 737 MAX aircraft returned to Stockholm, and two Turkish Airlines MAX aircraft flying to Britain, one to Gatwick Airport south of London and the other to Birmingham, turned around and flew back to Turkey.[37][38]

Upon groundings, the MAX was operated on 8,600 weekly flights.[39]

During groundings

On June 11, Norwegian Flight DY8922 attempted a ferry flight from Málaga, Spain to Stockholm, Sweden. Such flights can only be flown by pilots meeting a certain European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) qualification, and with no other cabin crew or passengers. The flight plan contained specific parameters to avoid MCAS intervention, flying at lower altitude than normal with flaps extended, and autopilot on.[40] However, the aircraft was refused entry into German airspace, and diverted to Châlons Vatry, France.[41][42]

In a rare exemption, Transport Canada approved 11 flights in August and September, partly to maintain the qualifications of senior Air Canada training pilots, because the airline has no earlier-generation 737s within its fleet. The airline used the MAX during planned maintenance movements, and ultimately flew it to Pinal Airpark in Arizona for storage.[43]

To prepare for ferry flights of its five MAX 8s for winter storage in the milder climate of Toulouse, France, Icelandair pilots trained in a flight simulator. Scheduled for early October, the aircraft will have the wing flaps out as little as possible and will fly at a lower than usual speed and at an altitude not exceeding 20,000 feet, resulting in the flights taking two hours longer than normal.[44] The Directorate General for Civil Aviation demanded that the flights avoid urban areas.[45]

Regulators

Although regulators typically follow guidance from the plane maker and its national certifying authority, in this case they cited safety precautions as reason to ground the aircraft, and revoked clearance of MAX aircraft from foreign airlines despite the lack of guidance from Boeing and the Continued Airworthiness Notification from the FAA.[46]

- March 11

- China: The Civil Aviation Administration of China orders all domestic airlines to suspend operations of all 737 MAX 8 aircraft by 18:00 local time (10:00 GMT), pending the results of the investigation, thus grounding all 96 Boeing 737 MAX planes (c. 25% of all delivered) in China.[47][48]

- United States: The FAA issued an affirmation of the continued airworthiness of the 737 MAX.[136] As many airlines and regulators began grounding the MAX, the FAA issued a "continued airworthiness notification", stating that it had no evidence from the crashes to justify regulatory action against the aircraft.[137]

- Indonesia: Nine hours after China's grounding,[138] the Indonesian Ministry of Transportation issued a temporary suspension on the operation of all eleven 737 MAX 8 aircraft in Indonesia. A nationwide inspection on the type was expected to take place on March 12[139] to "ensure that aircraft operating in Indonesia are in an airworthy condition".[140]

- Mongolia: Civil Aviation Authority of Mongolia (MCAA) said in a statement "MCAA has temporarily stopped the 737 MAX flight operated by MIAT Mongolian Airlines from March 11, 2019."[141]

- March 12

- Singapore: the Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore, "temporarily suspends" operation of all variants of the 737 MAX aircraft into and out of Singapore.[73]

- India: Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) released a statement "DGCA has taken the decision to ground the 737 MAX aircraft immediately, pursuant to new inspections.[142]

- Turkey: Turkish Civil Aviation Authority suspended flights of 737 MAX 8 and 9 type aircraft being operated by Turkish companies in Turkey, and stated that they are also reviewing the possibility of closing the country's airspace for the same.[143]

- South Korea: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT) advised Eastar Jet, the only airline of South Korea to possess Boeing 737 MAX aircraft to ground their models,[144] and three days later issued a NOTAM (Notice to Airmen) message to block all Boeing 737 MAX models from landing and departing from all domestic airports.[145]

- Europe: The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) suspended all flight operations of all 737-8 MAX and 737-9 MAX in Europe. In addition, EASA published a Safety Directive, published at 18:23,[146] effective as of 19:00 UTC, suspending all commercial flights performed by third-country operators into, within or out of the EU of the above mentioned models[57] The reasons invoked include:[146]

Technical decision, data driven, precautionary measure: Similarities with the Lion Air accident data; Application of EASA guidance material for taking corrective actions in case of potential unsafe conditions; Additional considerations: no direct access to the investigation, unusual scenario of a "young" aircraft experiencing 2 fatal accidents in less than 6 months.

— Paytrick Ky, director - Canada: Minister of Transport Marc Garneau said it was premature to consider groundings and that, "If I had to fly somewhere on that type of aircraft today, I would."[147]

- Australia: The Civil Aviation Safety Authority banned Boeing 737 MAX from Australian airspace.[148]

- Malaysia: The Civil Aviation Authority of Malaysia suspended the operations of the Boeing 737 Max 8 aircraft flying to or from Malaysia and transiting in Malaysia.[149]

- March 13

- Canada: Minister of Transport Marc Garneau, prompted by receipt of new information,[150] said "There can't be any MAX 8 or MAX 9 flying into, out of or across Canada", effectively grounding all 737 MAX aircraft in Canadian airspace.[151][152]

- United States: President Donald Trump announced on March 13, that United States authorities would ground all 737 MAX 8 and MAX 9 aircraft in the United States.[153][154] After the President's announcement, the FAA officially ordered the grounding of all 737 MAX 8 and 9 operated by U.S. airlines or in the United States airspace.[113] The FAA did allow airlines to make ferry flights without passengers or flight attendants in order to reposition the aircraft in central locations.[155][156]

- Hong Kong: The Civil Aviation Department banned the operation of all 737 Max aircraft into, out of and over Hong Kong.[157]

- Panama: The Civil Aviation Authority grounded its aircraft.[158][159]

- Vietnam: The Civil Aviation Authority of Vietnam banned Boeing 737 MAX aircraft from flying over Vietnam.[160]

- New Zealand: The Civil Aviation Authority of New Zealand suspended Boeing 737 MAX aircraft from its airspace.[161]

- Mexico: Mexico's civil aviation authority suspended flights by Boeing 737 MAX 8 and MAX 9 aircraft in and out of the country.[162]

- Brazil: The National Civil Aviation Agency (ANAC) suspended the 737 MAX 8 aircraft from flying.[163]

- Colombia: Colombia's civil aviation authority banned Boeing 737 MAX 8 planes from flying over its airspace.[164]

- Chile: The Directorate General of Civil Aviation banned Boeing 737 MAX 8 flights in the country's airspace.[165]

- Trinidad and Tobago: The Director General of Civil Aviation banned Boeing 737 Max 8 and 9 planes from use in civil aviation operations within and over Trinidad and Tobago.[166]

- March 14

- Taiwan: The Civil Aeronautics Administration banned Boeing 737 Max from entering, leaving or flying over Taiwan.[128]

- Japan: Japan's transport ministry banned flights by Boeing 737 MAX 8 and 9 aircraft from its airspace.[167]

- March 16

- Argentina: The National Civil Aviation Administration (ANAC) closed airspace to Boeing 737 MAX flights.[168]

- June 27

Airlines

After the Ethiopian Airlines crash, some airlines proactively grounded their fleets and regulatory bodies grounded the others. (This list includes MAX aircraft that have powered on their transponders, but may not yet have been delivered to an airline. Some pre-delivered aircraft are located at Boeing Field, Renton Municipal Airport and Paine Field airports).[127]

Accident investigations

Per the Convention on International Civil Aviation, if an aircraft of a contracting State has an accident or incident in another contracting State, the State where the accident occurs will institute an inquiry. The Convention defines the rights and responsibilities of the states.

ICAO Annex 13—Aircraft Accident and Incident Investigation—defines which States may participate in an investigation, for example: the States of Occurrence, Registry, Operator, Design and Manufacture.[191]

The investigating countries or participating ones mentioned below are member of the Joint Authorities Technical Review (JATR) with exception of Ethiopia, which delegates the main investigation to France, a member of EASA. Particularly Australia and Singapore expressed interest shortly after the first 737 MAX accident by offering support to Indonesia.

Indonesia

In August 2019, leaked copies of the unreleased[192] National Transportation Safety Committee (NTSC) report in circulation listed design and oversight lapses playing a key role in the Lion Air Flight 610 crash. The draft conclusions also identify pilot and maintenance errors as causal factors among a hundred elements of the crash chronology, without ranking them.[193][194]

Lion Air expressed objections because NTSC's latest draft, according to a source, attributes 25 lapses to Lion Air out of 41 lapses found.[195] There are also doubts about the acceptability of some photographs used in the investigation, as they could be fabricated evidence of repair to the doomed Lion Air MAX. The company opposes raising an issue about the photographs in the final accident report.[196]

The final report of NTSC has been disclosed first to the families of the crash victims of the Lion Air Flight 610 on Wednesday, October 23, 2019, which stated that mechanical issues and design flaws with the flight control system of MAX contributed to the aircraft's accident in October 2018.[197][198]

Ethiopia

The Ethiopian Civil Aviation Authority (ECAA)'s Accident Prevention and Investigation Bureau, which cited similarities between both accidents in its preliminary report for Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, collaborated investigation efforts with Indonesian NTSC and Transportation Ministry representatives.[199][200]

United States

On October 31, 2018, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) and an engineering team from Boeing arrived in Indonesia to assist with the Lion Air accident investigation led by the NTSC.[201]

On September 26, 2019, the NTSB released the results of its review of potential lapses in the design and approval of the 737 MAX.[202][203]: 1 [204] The NTSB concluded that the assumptions that Boeing used in its functional hazard assessment of uncommanded MCAS function for the 737 MAX did not adequately consider and account for the impact that multiple flight deck alerts and indications could have on pilots' responses to the hazard.[203][205]

The flight deck interface for alerts could be improved so as to minimize crew errors, according to the report.[206] "For example, the erroneous AOA output experienced during the two accident flights resulted in multiple alerts and indications to the flight crews, yet the crews lacked tools to identify the most effective response. Thus, it is important that system interactions and the flight deck interface be designed to help direct pilots to the highest priority action(s)."[203]

The NTSB also questions the long-held industry and FAA practice of assuming the nearly instantaneous responses of highly trained test pilots as opposed to pilots of all levels of experience to verify human factors in aircraft safety.[207]

The NTSB urges the FAA to take action on the safety recommendations in its report. It is concerned that the process used to evaluate the original design needs improvement because that process is still in use to certify current and future aircraft and system designs. The FAA could for example randomly sample pools from the worldwide pilot community to get a more representative assessment of cockpit situations.[208]

The NTSB report highlights the incomplete validation of the functional hazard assessment, with potentially confusing indications in the cockpit: "Thus, the specific failure modes that could lead to unintended MCAS activation (such as an erroneous high AOA input to the MCAS) were not simulated as part of these functional hazard assessment validation tests. As a result, additional flight deck effects (such as IAS DISAGREE and ALT DISAGREE alerts and stick shaker activation) resulting from the same underlying failure (for example, erroneous AOA) were not simulated and were not in the stabilizer trim safety assessment report reviewed by the NTSB."[203]

Singapore

Singapore's Transport Safety Investigation Bureau (TSIB) sent a team to assist in the search for Lion Air Flight 610's flight recorders, after NTSC of Indonesia accepted their offer. The TSIB support consisted of a team of three specialists and an underwater locator beacon detector to assist with the search. The team arrived in Jakarta on the evening of October 29, 2018.[209]

Australia

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau sent two of its personnel to assist the Indonesian NTSC with the downloading process of the FDR.

France

The French Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety (BEA), which handled the investigation of Air France Flight 447 announced they would analyze the flight recorders from Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. The German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident Investigation, being unable to decode the flight recorders on the 737 MAX, declined a prior request.[210] BEA received the flight recorders on March 14, 2019.[211]

Avionics analysis

Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System

The Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) flight control law was introduced on the 737 MAX to mitigate the aircraft's tendency to pitch up because of the aerodynamic effect of its larger, and heavier, and more powerful CFM LEAP-1B engines and nacelles. The stated goal of MCAS, according to Boeing, was to make the 737 MAX perform similarly to its immediate predecessor, the 737 Next Generation. The FAA and Boeing both refuted media reports describing MCAS as an anti-stall system, which Boeing asserted it is distinctly not.[212][213][214] The aircraft had to perform well in a low-speed stall test.[215]

Investigators suspect that MCAS was triggered by falsely high angle of attack (AoA) inputs, as if the plane had pitched up excessively. On both flights, shortly after takeoff, MCAS repeatedly actuated the horizontal stabilizer trim motor to push down the airplane nose.[216][217][218][219] Satellite data for the flights, ET 302 and JT 610, showed that the planes struggled to gain altitude.[220] Pilots reported difficulty controlling the airplane and asked to return to the airport.[154][221] On April 4, 2019 Boeing publicly acknowledged that MCAS played a role in both accidents.[222]

After the Lion Air crash, Boeing told airlines that MCAS could not be overcome by pulling back on the control column to stop a runaway trim as on previous generation 737s.[223] Nevertheless, confusion continued: the safety committee of a major U.S. airline misled its pilots by telling that the MCAS could be overcome by "applying opposite control-column input to activate the column cutout switches".[224] Former pilot and CBS aviation & safety expert "Sully" Sullenberger testified, "The logic was that when MCAS was activated, it had to be, and must not be prevented."[225]

On March 11, 2019, after China had grounded the aircraft,[226] Boeing published some details of new system requirements for the MCAS software and for the cockpit displays, which it began implementing in the wake of the prior accident five months earlier:[216]

- If the two AOA sensors disagree with the flaps retracted, MCAS will not activate and an indicator will alert the pilots.

- If MCAS is activated in non-normal conditions, it will only "provide one input for each elevated AOA event."

- Flight crew will be able to counteract MCAS by pulling back on the column.

On March 27, Daniel Elwell, the acting administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), testified before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, saying that on January 21, "Boeing submitted a proposed MCAS software enhancement to the FAA for certification. ... the FAA has tested this enhancement to the 737 MAX flight control system in both the simulator and the aircraft. The testing, which was conducted by FAA flight test engineers and flight test pilots, included aerodynamic stall situations and recovery procedures."[227] After a series of delays, the updated MCAS software was released to the FAA in May 2019.[228][229] On May 16, Boeing announced that the completed software update was awaiting approval from the FAA.[230][231] The flight software underwent 360 hours of testing on 207 flights.[232] Boeing also updated existing crew procedures.[216] The implementation of MCAS has been found to disrupt autopilot operations.[233]

Runaway stabilizer trim procedure

In November 2018, Boeing's CEO Muilenburg, when asked about the non-disclosure of MCAS, cited the "runaway stabilizer trim" procedure as part of the training manual. He added that Boeing's bulletin pointed to that existing flight procedure. Boeing views the "runaway stabilizer trim" checklist as a memory item for pilots. Mike Sinnett, vice president and general manager for the Boeing New Mid-Market Airplane (NMA) since July 2019, repeatedly described the procedure as a "memory item".[21] However, some airlines view it as an item for the quick reference card.[234] The FAA issued a recommendation about memory items in an Advisory Circular, Standard Operating Procedures and Pilot Monitoring Duties for Flight Deck Crewmembers: "Memory items should be avoided whenever possible. If the procedure must include memory items, they should be clearly identified, emphasized in training, less than three items, and should not contain conditional decision steps."[235]

In a legal complaint against Boeing, the Southwest Airlines Pilot Association states:[236]

An MCAS failure is not like a runaway stabilizer. A runaway stabilizer has continuous un-commanded movement of the tail, whereas MCAS is not continuous and pilots (theoretically) can counter the nose-down movement, after which MCAS would move the aircraft tail down again. Moreover, unlike runaway stabilizer, MCAS disables the control column response that 737 pilots have grown accustomed to and relied upon in earlier generations of 737 aircraft.

In May, The Seattle Times reported that the two stabilizer cutoff switches on the MAX operate differently than on the earlier 737 NG. On previous aircraft, one cutoff switch deactivates the thumb buttons on the control yoke that pilots use to move the horizontal stabilizer; the other cutoff switch disables automatic control (as from autopilot) to move the stabilizer in the tail. On the MAX, both switches do the same thing: they cut off all electric power to the stabilizer, both from the yoke buttons and from an automatic system, like MCAS. With all power to the stabilizer cut, pilots have no choice but to use the mechanical trim wheel in the center console.[237]

Angle of attack sensor system architecture

The Angle of Attack sensors measure an aircraft's pitch relative to oncoming winds. Though there are two sensors, only one of them is used at a time to trigger MCAS activation on the 737 MAX. The angle of attack system is not robust to the failure of a single AoA sensor, thus activating MCAS under a single point of failure.[225] Redundancy is a technique that may be used to achieve the quantitative safety requirements per recognized development practices of aircraft systems, such as ARP4754.[238] The sensors themselves are under scrutiny. Sensors on the Lion air aircraft were supplied by United Technologies' Rosemount Aerospace.[239] A company based in Florida, XTRA Aerospace Inc., had worked on the 737 MAX AoA sensor of the Lion Air accident.[240][196]

The U.S. Air Force (USAF) has KC-46 Pegasus aerial refueling tankers on order, which is based on a Boeing 767. MCAS, as designed on the KC-46, compares both sensors, and allows pilots to retake control of the airplane.[241][242]

In September 2019, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) said it prefers triple-redundant Angle of Attack sensors rather than the dual redundancy in Boeing's proposed upgrade to the MAX.[243] Installation of a third sensor could be expensive and take a long time. The change, if mandated, could be extended to thousands of older model 737s in service around the world.[243]

Angle of attack display

In 1996, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) issued Safety Recommendation A-96-094.

TO THE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION (FAA): Require that all transport-category aircraft present pilots with angle-of-attack info in a visual format, and that all air carriers train their pilots to use the info to obtain maximum possible airplane climb performance.

The NTSB also stated about another accident in 1997, that "a display of angle of attack on the flight deck would have maintained the flightcrew's awareness of the stall condition and it would have provided direct indication of the pitch attitudes required for recovery throughout the attempted stall recovery sequence." The NTSB also believed that the accident may have been prevented if a direct indication of AoA was presented to the flightcrew (NTSB, 1997)."[244]: 29

Boeing published an article in Aero magazine about AoA systems, "Operational use of Angle of Attack on modern commercial jet planes":

Angle of attack (AOA) is an aerodynamic parameter that is key to understanding the limits of airplane performance. Recent accidents and incidents have resulted in new flight crew training programs, which in turn have raised interest in AOA in commercial aviation. Awareness of AOA is vitally important as the airplane nears stall. [...] The AOA indicator can be used to assist with unreliable airspeed indications as a result of blocked pitot or static ports and may provide additional situation and configuration awareness to the flight crew.[245]

Boeing announced a change in policy in the Frequently Asked Questions in a (FAQ) about the MAX corrective work, "With the software update, customers are not charged for the AOA disagree feature or their selection of the AOA indicator option."[246]

Angle-of-Attack Disagree alert

The Angle-of-Attack Disagree alert, via an annunciator on the primary flight display, tells the pilot that the pair of AoA sensors, which should provide similar readings, have deviated significantly.[247] Thus, pilots get insight into disagreements and the feature prompts for a maintenance logbook entry.[216]

In November 2017, after several months of MAX deliveries, Boeing discovered that the alert was inoperable on most aircraft. The alert function depended on the presence of an optional indicator, which was not selected by most airlines. Boeing had determined that the defect was not critical to aircraft safety or operation, and an internal safety review board (SRB) corroborated Boeing's prior assessment and its initial plan to update the aircraft in 2020. Boeing did not disclose the defect to the FAA until November 2018, in the wake of the Lion Air crash.[248] [249][250][251]

At Boeing, the SRB is responsible for deciding only if an issue is or is not a safety issue; a SRB brings together multiple company subject matter experts (SMEs) in many disciplines. The most knowledgeable SME presents the issue, assisted and guided by the Aviation Safety organization. The safety decision is taken as a vote. Any vote for "safety" results in a board decision of "safety".[252]

In March 2019, a Boeing representative told Inc. magazine, "Customers have been informed that AOA [angle of attack] disagree alert will become a standard feature on the 737 Max. It can be retrofitted on previously delivered airplanes."[253]

In May 2019, Boeing defended that "Neither the angle of attack indicator nor the AoA Disagree alert are necessary for the safe operation of the airplane." Boeing recognized that the defective software was not implemented to their specifications as a "standard, standalone feature." Boeing stated, "...MAX production aircraft will have an activated and operable AOA Disagree alert and an optional angle of attack indicator. All customers with previously delivered MAX airplanes will have the ability to activate the AOA Disagree alert."[249] Boeing CEO Muilenburg said the company's communication about the alert "was not consistent. And that's unacceptable."[254][249]

On June 7, the delayed escalation on the defective Angle-of-Attack Disagree alert on 737 MAX was investigated. The Chair of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure and the Chair of the Aviation Subcommittee sent letters to Boeing, United Technologies Corp., and the FAA, requesting a timeline and supporting documents related to awareness of the defect, and when airlines were notified.[255]

Flight computer architecture

In early April 2019, Boeing reported a problem with software affecting flaps and other flight-control hardware, unrelated to MCAS; classified as critical to flight safety, the FAA has ordered Boeing to fix the problem correspondingly.[256] In October 2019, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has suggested to conduct more testing on proposed revisions to flight-control computers due to its concerns about portions of proposed fixes to MCAS.[257]

Microprocessor

In June 2019, "in a special Boeing simulator that is designed for engineering reviews,"[258] FAA pilots performed a stress testing scenario – an abnormal condition identified through FMEA after the MCAS update was implemented[259] – for evaluating the effect of a fault in a microprocessor: as expected from the scenario, the horizontal stabilizer pointed the nose downward. Although the test pilot ultimately recovered control, the system was slow to respond to the proper runaway stabilizer checklist steps. Boeing initially classified this as a "major" hazard, and the FAA upgraded it to a more severe "catastrophic" rating. Boeing stated that the issue can be fixed in software.[260] The software change will not be ready for evaluation until at least September 2019.[261] EASA director Patrick Ky said that retrofitting additional hardware is an option to be considered.[233]

Early news reports were inaccurate in attributing the problem to an 80286[262] microprocessor overwhelmed with data. The test scenario simulated an event toggling five bits in the flight control computer. The bits represent status flags such as whether MCAS is active, or whether the tail trim motor is energized. Engineers were able to simulate single event upsets and artificially induce MCAS activation by manipulating these signals. Such a fault occurs when memory bits change from 0 to 1 or vice versa, which is something that can be caused by cosmic rays striking the microprocessor.[263]

The failure scenario was known before the MAX entered service in 2017: it had been assessed in a safety analysis when the plane was certified. Boeing had concluded that pilots could perform a procedure to shut off the motor driving the stabilizer to overcome the nose-down movement.[264] The scenario also affects 737NG aircraft, though it presents less risk than on the MAX. On the NG, moving the yoke counters any uncommanded stabilizer input, but this function is bypassed on the MAX to avoid negating the purpose of MCAS.[265] Boeing also said that it agreed with additional requirements that the FAA required it to fulfill, and added that it was working toward resolving the safety risk. It will not offer the MAX for certification until all requirements have been satisfied.[260]

Redundancy

As of 2019[update], the two flight control computers of Boeing 737 never cross-checked each others' operations, i.e. single non-redundant channel. This lack of robustness existed since the early implementation and persisted for decades.[263] The updated flight control system will use both flight control computers and compare their outputs. This switch to a fail-safe two-channel redundant system, with each computer using an independent set of sensors, is a radical change from the architecture used on 737s since the introduction on the older model 737-300 in the 1980s. Up to the MAX in its prior to groundings version, the system alternates between computers after each flight.[263]

Type rating and training needs

In the U.S., the MAX shares a common type rating with all the other Boeing 737 families.[266] The impetus for Boeing to build the 737 MAX was serious competition from the Airbus A320neo, which was a threat to win a major order for aircraft from American Airlines, a traditional customer for Boeing airplanes.[226] Boeing decided to update its venerable 737, first designed in the 1960s, rather than creating a brand-new airplane, which would have cost much more and taken years longer. Boeing's goal was to ensure the 737 MAX would not need a new type rating, which would require significant additional pilot training, adding unacceptably to the overall cost of the airplane for customers.

The 737 original and main certification was issued by the FAA in 1967. Like every new 737 model since then, the MAX has been approved partially with the original requirements and partially with more current regulations, enabling certain rules and requirements to be grandfathered in.[267] Chief executive Dai Whittingham of the independent trade group UK Flight Safety Committee disputed the idea that the MAX was just another 737, saying, "It is a different body and aircraft but certifiers gave it the same type rating."[268]

According to The Seattle Times, Boeing convinced the FAA, during MAX certification in 2014, to grant exceptions to federal crew alerting regulations.[269]

Boeing also played down the scope of MCAS to regulators. The company "never disclosed the revamp of MCAS to FAA officials involved in determining pilot training needs".[270] On March 30, 2016, the Max's chief technical pilot requested senior FAA officials to remove MCAS from the pilot's manual. The officials had been briefed on the original version of MCAS but not that MCAS was being significantly overhauled.[270] On October 20, in response to harsh reactions to the publication of controversial messages from its former chief technical test pilot Mark Forkner, the company issued a statement about misinterpretations and how it informed the FAA of the expansion of MCAS to low speeds.[271]

Crew manuals, pilot training and simulators

Boeing considered MCAS part of the flight control system, and elected to not describe it in the flight manual or in training materials, based on the fundamental design philosophy of retaining commonality with the 737NG.[226] The 1,600-page flight crew manual mentions the term MCAS once, in the glossary.[272] Top Boeing officials believed MCAS operated way beyond normal flight envelope that it was unlikely to activate in normal flight.[273]

Boeing published a service bulletin on November 6, 2018, in which MCAS was anonymously referred to as a "pitch trim system." In reference to the Lion Air accident, Boeing said the system could be triggered by erroneous Angle of Attack information when the aircraft is under manual control, and reminded pilots of various indications and effects that can result from this erroneous information.[274][8][8] Only four days later, Boeing acknowledged the existence of MCAS in a message to operators on November 10, 2018.[6][275]

In the months between the accidents, the FAA Aviation Safety Reporting System received numerous U.S. pilot complaints of the aircraft's unexpected behaviors, and how the crew manual lacked any description of the system.[276] Most air regulatory agencies, including the FAA, Transport Canada and EASA, didn't require specific training on MCAS. Brazil's national civil aviation agency "was one of the only civil aviation authorities to require specific training for the operation of the 737-8 Max".[277]

In February 2016, the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) certified the MAX with the expectation that pilot procedures and training would clearly explain unusual situations in which the seldom used manual trim wheel would be required to trim the plane, i.e. adjust the angle of the nose; however, the original flight manual did not mention those situations.[278] The EASA certification document referred to simulations whereby the electric thumb switches were ineffective to properly trim the MAX under certain conditions. The EASA document said that after flight testing, because the thumb switches could not always control trim on their own, the FAA was concerned by whether the 737 MAX system complied with regulations.[279] The American Airlines flight manual contains a similar notice regarding the thumb switches but does not specify conditions where the manual wheel may be needed.[279]

On May 15, during a senate hearing, FAA acting administrator Daniel Elwell defended their certification process of Boeing aircraft. However the FAA criticized Boeing for not mentioning the MCAS in the 737 MAX's manuals. Representative Rick Larsen responded saying that "the FAA needs to fix its credibility problem" and that the committee would assist them in doing so.[280][281]

On May 17, after discovering 737 MAX flight simulators could not adequately replicate MCAS activation,[282] Boeing corrected the software to improve the force feedback of the manual trim wheel and to ensure realism.[283] This led to a debate on whether simulator training is a prerequisite prior to the aircraft's eventual return to service. On May 31, Boeing proposed that simulator training for pilots flying on the 737 MAX would not be mandatory.[284] Computer training is deemed sufficient by the FAA Flight Standardization Board, the US Airline Pilots Association and Southwest Airlines pilots, but Transport Canada and American Airlines urged use of simulators.[285][286] On June 19, in a testimony before the U.S. House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, Chesley Sullenberger advocated for simulator training. "Pilots need to have first-hand experience with the crash scenarios and its conflicting indications before flying with passengers and crew."[287][225] The "differences training" is the subject of worry by senior industry training experts.[288]

Textron-owned simulator maker TRU Simulation + Training anticipates a transition course but not mandatory simulator sessions in minimum standards being developed by Boeing and the FAA.[289]

On July 24, Boeing indicated that some regulatory agencies may mandate simulator training before return to service, and also expected some airlines to require simulator sessions even if these are not mandated.[290]

Certification inquiries

This section may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines. (August 2019) |

The U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) Inspector General opened an investigation into FAA approval of the Boeing 737 MAX aircraft series, focusing on potential failures in the safety-review and certification process. The day after the Ethiopian Airlines crash, a U.S. federal grand jury issued a subpoena on behalf of the U.S. Justice Department for documents related to development of the 737 MAX.[291][292][293][294] On March 19, 2019, the U.S. Department of Transportation requested the Office of Inspector General to conduct an audit on the 737 MAX certification process.[295] The FBI has joined the criminal investigation into the certification as well.[296][297] FBI agents reportedly visited the homes of Boeing employees in "knock-and-talks".[298]

On July 17, representatives of crash victims' families, in testimony to the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee Aviation Subcommittee, called on regulators to re-certificate the MAX as a completely new aircraft. They also called for wider reforms to the certification process, and asked the committee to grant protective subpoenas so that whistle-blowers could testify even if they had agreed to a gag order as a condition of a settlement with Boeing.[299]

In a July 31 senate hearing, the FAA defended its administrative actions following the Lion Air accident, noting that standard protocol in ongoing crash investigations limited the information that could be provided in the airworthiness directive. The agency had recognized that pilot actions played a significant role in the Lion Air accident, and did not dispute that FAA officials believed a recurrence of MCAS malfunction was likely, as reported by The Wall Street Journal.[300][301][302]

Boeing's former Chief Technical pilot Mark Forkner has invoked the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination, to avoid submitting documents to federal prosecutors investigating the crashes.[303] He was managing pilots in the Flight Technical and Safety group within Boeing’s customer services division.[304] A Boeing technical test pilot flies a simulator, not the actual aircraft, such as the "e-cab" test flight deck built for developing the MAX[305][306]. On October 17, Boeing turned over some 10 pages of Forkner's correspondence showing concern with MCAS operation in 2016. The next day, FAA Administrator Dickson, in a strongly worded letter, ordered Muilenburg to give an "immediate" explanation for delaying disclosure of these documents for months.[307][308][309][310][311] DeFazio, chair of the U.S. House Transportation Committee, said on October 18, "The outrageous instant message chain between two Boeing employees suggests Boeing withheld damning information from the FAA". Boeing expressed regret over its ex-pilot's messages after their publication in media.[312] Boeing's media room released a statement about Forkner's meaning of the instant messages, obtained through his attorney because the company has not been able to talk to him directly. The transcript of the messages indicates, according to experts, a problem with the simulator rather than an MCAS erratic activation.[271][313][304]

Congress

In March 2019, Congress announced an investigation into the FAA approval process.[314] Members of Congress and government investigators expressed concern about FAA rules that allowed Boeing to extensively "self-certify" aircraft.[315][316] FAA acting Administrator Daniel Elwell said "We do not allow self-certification of any kind".[317]

In September, a U.S. Congress panel asked Boeing's CEO to make several employees available for interviews, to complement the documents and the senior management perspective already provided.[318]

In September 2019, frustration with Boeing is mounting in Washington, and in the FAA and in international regulators.[319] Representative Peter DeFazio, Chair of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, said Boeing declined his invitation to testify at a House hearing. "Next time, it won't just be an invitation, if necessary," he said. Hearings on October 29 and 30 will be the first time that Boeing executives address Congress about the MAX accidents. In September, U.S. House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee announced that Boeing CEO Muilenburg will testify before Congress accompanied by John Hamilton, chief engineer of Boeing's Commercial Airplanes division and Jennifer Henderson, 737 chief pilot.[320] Hamilton may also appear at the Senate hearing.[321] The hearings come on the heels of the removal of Mr. Muilenburg's title as chairman of the Boeing board last week. They are expected to cover everything from the design, certification and marketing of the 737 Max to what happened on the flights that crashed.[321]

In October, the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee asked Boeing to allow a flight deck systems engineer who filed an internal ethics complaint to be interviewed.[322]

Office of Special Counsel investigation

On April 2, 2019, after receiving reports from whistle-blowers regarding the training of FAA inspectors who reviewed the 737 MAX type certificate, the Senate Commerce Committee launched a second Congressional investigation; it focuses on FAA training of the inspectors.[323][324][325]

The FAA provided misleading statements to Congress about the training of its inspectors, most possibly those inspectors that oversaw the Max certification, according to the findings of an Office of Special Counsel investigation released in September. The Office of Special Counsel is an organization investigating whistleblower reports. Its report infers that safety inspectors "assigned to the 737 Max had not met qualification standards".[326]

The OSC sided with the whistleblower, pointing out that internal FAA reviews had reached the same conclusion. In a letter to President Trump, the OSC found that 16 of 22 FAA pilots conducting safety reviews, some of them assigned to the MAX two years ago, "lacked proper training and accreditation."[327]

Safety inspectors participate in Flight Standardization Boards, that ensure pilot competency by developing training and experience requirements. FAA policy requires both formal classroom training and on-the-job training for safety inspectors.[328]

Special Counsel Henry J. Kerner wrote in the letter to the President, "This information specifically concerns the 737 Max and casts serious doubt on the FAA's public statements regarding the competency of agency inspectors who approved pilot qualifications for this aircraft".[329]

In September, Daniel Elwell disputed the conclusions of the OSC, which found that aviation safety inspectors (ASIs) assigned to the 737 MAX certifications did not meet training requirements.[330][331] To clarify the facts, lawmakers asked the FAA to provide additional information :

We are particularly concerned about the Special Counsel's findings that inconsistencies in training requirements have resulted in the FAA relaxing safety inspector training requirements and thereby adopting "a position that encourages less qualified, accredited, and trained safety inspectors." We request that the FAA provide documents confirming that all FAA employees serving on the FSB for the Boeing 737-MAX and the Gulfstream VII had the required foundational training in addition to any other specific training requirements.[332]

Joint Authorities Technical Review

On April 19, a "Boeing 737 MAX Flight Control System Joint Authorities Technical Review" (JATR) team was commissioned by the FAA to investigate how it approved MCAS, whether changes need to be made in the FAA's regulatory process and whether the design of MCAS complies with regulations.[333] On June 1, Ali Bahrami, FAA Associate Administrator for Aviation Safety, chartered the JATR to include representatives from FAA, NASA and the nine civil aviation authorities of Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Europe (EASA), Indonesia, Japan, Singapore and UAE.

On September 27, the JATR chair Christopher A. Hart said that FAA's process for certifying new airplanes is not broken, but needs improvements rather than a complete overhaul of the entire system. He added "This will be the safest airplane out there by the time it has to go through all the hoops and hurdles".[334]

According to the final report, FAA failed to properly review MCAS. About the nature of MCAS, "the JATR team considers that the STS/MCAS and EFS functions could be considered as stall identification systems or stall protection systems, depending on the natural (unaugmented) stall characteristics of the aircraft".[335] The report recommends that FAA reviews the jet's stalling characteristics without MCAS and associated system to determine the plane's safety and consequently if a broader design review was needed.[336]

"The JATR team identified specific areas related to the evolution of the design of the MCAS where the certification deliverables were not updated during the certification program to reflect the changes to this function within the flight control system. In addition, the design assumptions were not adequately reviewed, updated, or validated; possible flight deck effects were not evaluated; the SSA and functional hazard assessment (FHA) were not consistently updated; and potential crew workload effects resulting from MCAS design changes were not identified."[335] Nor has Boeing carried out a thorough verification by stress-testing of the MCAS.[337]

Boeing exerted "undue pressures" on Boeing ODA engineering unit members (who had FAA authority to approve design changes).[335][338]

Reactions

Aircraft manufacturers

Boeing

Accidents and grounding

Boeing issued a brief statement after each crash, saying it was "deeply saddened" by the loss of life and offered its "heartfelt sympathies to the families and loved ones" of the passengers and crews. It said it was helping with the Lion Air investigation and sending a technical team to assist in the Ethiopia investigation.[339][340][341]

As non-U.S. countries and airlines began grounding the 737 MAX, Boeing stated: "at this point, based on the information available, we do not have any basis to issue new guidance to operators."[342] Boeing said "in light of" the Ethiopian Airlines crash, the company would postpone the scheduled March 13 public roll-out ceremony for the first completed Boeing 777X.[343]

When the FAA grounded the MAX aircraft on March 13, Boeing stated it "continues to have full confidence in the safety of the 737 MAX. However, after consultation with the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), and aviation authorities and its customers around the world, Boeing has determined – out of an abundance of caution and in order to reassure the flying public of the aircraft's safety – to recommend to the FAA the temporary suspension of operations of the entire global fleet of 737 MAX aircraft."[344]

After the grounding, Boeing suspended 737 MAX deliveries to customers, but continued production at a rate of 52 aircraft per month.[345] In mid-April, the production rate was reduced to 42 aircraft per month.[346] In May 2019, Boeing reported a 56% drop in plane deliveries year on year.[347] In July 2019, after reporting its financial results, Boeing stated that it would consider further reducing or even shutting down production if the grounding lasts longer than expected.[348][290] On August 23, Boeing announced that if the FAA clears the aircraft to return to service by October 2019, production would return from 42 aircraft per month to 52 by the end of February, and then climb to 57 per month by summer 2020.[349]

On October 11, 2019, Boeing's board removed Dennis Muilenburg as chairman and replaced him with Dennis Calhoun. Muilenburg himself will continue to run the company as CEO with the goal of getting the Boeing 737 MAX back in service. The decision was taken after the JATR released a report in the same day saying that FAA's "limited involvement" and "inadequate awareness" of the automated MCAS safety system "resulted in an inability of the FAA to provide an independent assessment".[350] The panel report added that Boeing staff performing the certification were also subject to "undue pressures... which further erodes the level of assurance in this system of delegation".[351]On September 12, Boeing started an advertisement campaign, in which employees praise its planes' safety.[352]

Investigation feedback

Between the Ethiopian accident and US groundings, Boeing stated that upgrades to the MCAS flight control software, cockpit displays, operation manuals and crew training were underway due to findings from the Lion Air crash. Boeing anticipated software deployment in the coming weeks and said the upgrade would be made mandatory by an FAA Airworthiness Directive.[353] The FAA stated it anticipated clearing the software update by March 25, 2019, allowing Boeing to distribute it to the grounded fleets.[354] On April 1, the FAA announced the software upgrade was delayed because more work was necessary.[355]

On March 14, Boeing reiterated that pilots can always use manual trim control to override software commands, and that both its Flight Crew Operations Manual and November 6 bulletin offer detailed procedures for handling incorrect angle-of-attack readings.[356][357]

On April 4, 2019, Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg acknowledged that MCAS played a role in both crashes. His comments came in response to public release of preliminary results of the Ethiopian Airlines accident investigation, which suggested pilots performed the recovery procedure. Muilenburg stated it was "apparent that in both flights" MCAS activated due to "erroneous angle of attack information". He said the MCAS software update and additional training and information for pilots would "eliminate the possibility of unintended MCAS activation and prevent an MCAS-related accident from ever happening again".[222] Boeing reported that 96 test flights were flown with the updated software.[358][359]

In an earnings call that took place on April 24, 2019, Muilenburg said the aircraft was properly designed and certificated, and denied that any "technical slip or gap" existed. He said there were "actions or actions not taken that contributed to the final outcome".[360] On April 29, he claimed that the pilots did not "completely" follow the procedures that Boeing had outlined. He said Boeing was working to make the airplane even safer.[361][276]

On May 5, Boeing asserted that "Neither the angle of attack indicator nor the AOA Disagree alert are necessary for the safe operation of the airplane. They provide supplemental information only, and have never been considered safety features on commercial jet transport airplanes."[249] On May 29, Muilenburg acknowledged that the crashes had damaged the public's trust.[362] Before the June Paris Air Show, Muilenburg said, regarding the AoA disagree indicator, that Boeing made "a mistake in the implementation of the alert" and the company's communication "was not consistent. And that's unacceptable."[254]

On August 4, 2019, Boeing stated they conducted around 500 test flights with updated software,[363] and Wired reported that one test flight involved multiple altitude changes.[364]

Corporate structure and new safety practices

Following panel review recommendations, Boeing has strengthened its engineering oversight. As of August 2019, Muilenburg receives weekly reports of potential safety issues from rank-and-file engineers – thousands will report to chief engineers rather than to separate programs, helping them reach senior management more effectively.[365]

On September 2019, The New York Times reported that Boeing board will call for structural changes after the 737 MAX crashes: changing corporate reporting structures, a new safety group, future plane cockpits designed for new pilots with less training. The committee, established in April, did not investigate the Max crashes, but produced the first findings for a reform of Boeing's internal structures since then. It will recommend that engineers report to the chief engineer rather than business management, to avoid pressure from business leaders against engineers who identify safety issues. The committee found that inter-group communication was lacking within engineering and between the Seattle offices and corporate headquarters during the certification work. The safety group will ensure information is shared and the certification work is independent. The group will report to senior leadership and a new permanent committee on the board.[319][366]

The board said in September that Boeing should also work with airlines to "re-examine assumptions around flight deck design and operation" and recommend pilot training criteria beyond traditional training programs "where warranted".[367]

Key positions

In July 2019, Boeing announced the retirement of 737 program leader Eric Lindblad, the second person to depart that post in two years. He held the job less than a year, but was not involved in development of the MAX. His predecessor, Scott Campbell, retired in August 2018, amid late deliveries of 737 MAX engines and other components. Lindblad assumed the role shortly before the program became embattled in two accidents and ongoing groundings. He will be succeeded by Mark Jenks, vice president of the Boeing New Midsize Airplane program and previously in charge of the Boeing 787 Dreamliner.[368][369][relevant? – discuss]

In October 2019, on the day the JATR published its report, Boeing announced the separation of the CEO and chairman roles,[370] allowing Muilenburg to focus on getting the MAX back in the air. The board elected David L. Calhoun to serve as non-executive chairman; he is an independent lead director, and former boss of GE Aviation and potential Boeing CEO. Boeing had resisted earlier calls from shareholder activists to split the roles.[371][372][373][338]

On October 22, Boeing named Stan Deal to succeed Kevin McAllister, who has faced a number of problems beyond the MAX crisis during his three years as president and chief executive of Boeing Commercial Airplanes (BCA).[374][375]

Current and former employees

In May 2019, engineers said that Boeing pushed to limit safety testing to accelerate planes certification, including 737 MAX.[376] FAA said it has "received no whistleblower complaints or any other reports ... alleging pressure to speed up 737 MAX certification." Former engineers at Boeing blamed company executives of cost-cutting, over more than a decade, yielding to low morale and reduced engineering staffing, which "they argue contributed to two recent deadly crashes involving Boeing 737 Max jets."[377]

In June 2019, Boeing's software development practices came under criticism from current and former engineers. Software development work for the MAX was reportedly complicated by Boeing's decision to outsource work to lower-paid contractors, including Indian companies HCL Technologies and Cyient, though these contractors did not work on MCAS or the AoA disagree alert. Management pressure to limit changes that might introduce extra time or cost was also highlighted.[378][379][380]

On October 2, 2019, The Seattle Times and The New York Times reported that a Boeing engineer, Curtis Ewbank, filed an internal complaint alleging that company managers rejected a backup system for determining speed, which might have alerted pilots to problems linked to two deadly crashes of 737 Max. A similar backup system is installed on the larger Boeing 787 jet, but it was rejected for 737 Max because it could increase costs and training requirements for pilots. Ewbank said the backup system could have reduced risks that contributed to two fatal crashes, though he could not be sure that it would have prevented them. He also said in his complaint that Boeing management was more concerned with costs and keeping the Max on schedule than on safety.[381][322] An attorney representing families of the Ethiopian crash victims will seek sworn evidence from the whistleblower.[382]

On October 18, Boeing turned over a discussion from 2016 between two employees which revealed prior issues with the MCAS system.[273]

Airbus

In May 2019, executives of Boeing competitor Airbus told reporters they do not view the relationship between Boeing and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) as having been corrupted. They compared the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and the FAA, saying "EASA has a slightly different mandate than the FAA. EASA is a purely safety orientated agency."[383] Airbus Chief Commercial Officer Christian Scherer did not feel the 737 MAX is a variant that has stretched the original 737 too far: "The MAX is not one stretch too many, in my humble opinion". Airbus leader Remi Maillard stated: "We work hand in hand with the regulators, and with the OEMs to adopt the safety standards. But, to be clear, our internal safety standards are even more stringent than what is required by the regulators". Scherer remarked on the way manufacturers can learn from accidents: "Whenever there is an accident out there, the first question that gets asked in an Airbus management meeting is: can we learn from it?"

Airbus continued to earn customer orders in the wake of the 737 MAX grounding, booking over US$11 billion in orders,[384] with similar[clarification needed] additional orders from airlines that are either canceling their 737 MAX orders altogether, or reducing quantities.[385]

The Airbus A320neo and the 737 MAX both use engines from the CFM LEAP family, with different thrust requirements. After EASA issued an airworthiness directive regarding potential excess pitch during specific maneuvers, Airbus made a preemptive change to the A320neo flight manual to protect the aircraft in such situations.[386][387] In response to the EASA recommendations, Lufthansa temporarily blocked the rearmost row of seats until a flight computer update increases the effectiveness of the aircraft's angle of attack protection.[388][relevant?]

Operators and professionals

Airlines

Because the groundings made the aircraft unavailable for service, airlines were forced to cancel thousands of flights, hundreds every day.[389][390] American Airlines was the first U.S. airline to cancel a route when it stopped service from Dallas, Texas to Oakland, California.[391]

Southwest Airlines notified their pilots that an optional feature, AoA indication on the cockpit displays, will be enabled to all aircraft in its fleet on November 30, 2018, shortly after Boeing had disclosed to airlines the existence of MCAS and the defective AoA disagree alert.[392][393] On July 26, the airline announced it would stop operations out of Newark Liberty International Airport due to the groundings.[394]

In May 2019, United Airlines' CEO Oscar Muñoz said that passengers would still feel uncertain about flying on a Boeing 737 MAX even after the software update.[395] United announced the cancellation of a route between Chicago, Illinois and Leon, Mexico.[396] On October 16, 2019, Muñoz stated that "nobody knows" when the plane will fly again.[397]

Ethiopian Airlines said "These tragedies continue to weigh heavily on our hearts and minds, and we extend our sympathies to the loved ones of the passengers and crew on board Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302".[398] The CEO also pushed back and rejected the notion that his airlines pilots were not fully trained or experienced, a notion intimated in the US House of Representatives in a recent hearing by the FAA director. Ethiopian Airlines rejects the accusation of piloting error.[399] He said: "As far as the training is concerned ... we've gone according to the Boeing recommendation and FAA-approved one. We are not expected to speculate or to imagine something that doesn't exist at all".[400] In June, Ethiopian Airlines CEO Tewolde Gebremariam expressed his confidence in the process for bringing the MAX back into service, and expected Ethiopian to be the last carrier to resume flights.[401]

Ethiopian Airline's ex-chief engineer filed a whistleblower complaint to the regulators about alleged corruption in Ethiopian Airlines. He is also seeking asylum in the U.S. He said that, a day after the Flight 302 crash, the carrier altered maintenance records of a Boeing 737 MAX aircraft. He submits that the alteration was part of a generalized culture of corruption "that included fabricating documents, signing off on shoddy repairs and even beating those who got out of line".[402]

In March 2019, RT reported the indefinite suspension of contracts for the purchase by Russian airlines of dozens of aircraft, including Aeroflot's Pobeda subsidiary, S7 Airlines, Ural Airlines and UTair. Vitaly Savelyev, Aeroflot's CEO, said that "the company would refuse operating MAX planes ordered by Pobeda".[403]

On June 18, International Airlines Group (IAG) announced plans for a fleet comprising 200 Boeing 737 MAX jets. Boeing and IAG signed a letter of intent at the Paris Air Show valued at a list price of over US$24 billion.[404]

Bjorn Kjos, ex-CEO of Norwegian Air Shuttle who stepped down in July, stated in July that the company "has a huge appetite for 737 MAX jets", according to a report from American City Business Journals.[405] He had said : "It is quite obvious that we will not take the cost... We will send this bill to those who produced this aircraft."[406]

In mid-July, Ryanair warned that some of its bases would be subject to short-term closures in 2020, due to the shortfall in MAX deliveries, and pointed out that the MAX 200 version it has ordered will require separate certification expected to take a further two months after the MAX returns to service.[407] By the end of July, Ryanair CEO Michael O'Leary expressed further concerns and frustration with the delays and revealed that, in parallel with discussions with Boeing regarding a potential order for new aircraft to be delivered from 2023, he was also talking to Airbus which was offering very aggressive pricing.[408]

Flight crew

In a private meeting on November 27, 2018, American Airlines pilots pressed Boeing managers to develop an urgent fix for MCAS and suggested that the FAA require a safety review which in turn could have grounded the airplanes.[409][410] A recording of the meeting revealed pilots' anger that they were not informed about MCAS. One pilot was heard saying, "We flat out deserve to know what is on our airplanes."[411] It is worth noting that a US pilot asked for more training prior to his first flight on the 737 MAX several months before the first crash of Lion Air Flight 610.[412] Afterwards, in June 2019, the American Airlines pilot union openly criticized Boeing for not fully explaining the existence or operation of MCAS: "However, at APA we remained concerned about whether the new training protocol, materials and method of instruction suggested by Boeing are adequate to ensure that pilots across the globe flying the MAX fleet can do so in absolute complete safety"[413] Boeing vice president Mike Sinnett explained that the company did not want to make changes in a rush, because of uncertainty whether the Lion Air accident was related to MCAS. Sinnett said Boeing expected pilots to be able to handle any control problems.[409]

In addition, the U.S. Aviation Safety Reporting System received messages about the 737 MAX from U.S. pilots in November 2018, including one from a captain who expressed concern that systems such as the MCAS are not fully described in the aircraft flight manual.[414][415] Captain Mike Michaelis, chairman of the safety committee of the Allied Pilots Association at American Airlines said "It's pretty asinine for them to put a system on an airplane and not tell the pilots … especially when it deals with flight controls".[416]

U.S. pilots also complained about the way the 737 MAX performed, including claims of problems similar to those reported about the Lion Air crash.[417] Pilots of at least two U.S. flights in 2018, reported the nose of the 737 MAX pitched down suddenly when they engaged the autopilot.[418] The FAA stated in response that "Some of the reports reference possible issues with the autopilot/autothrottle, which is a separate system from MCAS, and/or acknowledge the problems could have been due to pilot error."[419]

U.S. labor unions representing pilots and flight attendants had different opinions on whether or not to ground the aircraft. Two flight attendant unions, AFA and the APFA favored groundings,[420] while pilot unions such as the Southwest Airlines Pilots Association,[421] APA, and ALPA, expressed confidence in continued operation of the aircraft.[422]

On October 7, 2019, Southwest Airlines pilots sued Boeing declaring that Boeing misled the pilot union about the plane adding that the planes' grounding cost its pilots more than $100 million in lost income, which Southwest labor union wants Boeing to pay.[423]

Experts

On March 12, 2019, Jim Hall, a former chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board, the U.S. agency that investigates airplane crashes, said the FAA should ground the airplane.[424]

Retired airline captain Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger, who gained fame in the Miracle on the Hudson accident in 2009, said, "These crashes are demonstrable evidence that our current system of aircraft design and certification has failed us. These accidents should never have happened."[425] He sharply criticized Boeing and the FAA, saying they "have been found wanting in this ugly saga". He said the overly "cozy relationship" between the aviation industry and government was seen when the Boeing CEO "reached out to the U.S. President to try to keep the 737 MAX 8 from being grounded." He also lamented understaffing and underfunding of the FAA. "Good business means that it is always better and cheaper to do it right instead of doing it wrong and trying to repair the damage after the fact, and when lives are lost, there is no way to repair the damage."[426] He said AoA indicators might have helped in these two crashes. "It is ironic that most modern aircraft measure (angle of attack) and that information is often used in many aircraft systems, but it is not displayed to pilots. Instead, pilots must infer (angle of attack) from other parameters, deducing it indirectly."[427] In October, Sullenberger wrote, "These emergencies did not present as a classic runaway stabilizer problem, but initially as ambiguous unreliable airspeed and altitude situations, masking MCAS."[428]

Peter Goelz, a former managing director of the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), said: "One of the ways Boeing marketed the 737 Max was the modest amount of training up for current 737 pilots. You didn't have to go back to the Sim [the flight simulator] again and again."[429] James E. Hall, chairman of the NTSB from 1994 to 2001, blamed the FAA regulators for giving too much power to the airline industry.[291][430] In July, Hall and Goelz co-signed an opinion letter to The New York Times, in which they said: "Boeing has found a willing partner in the FAA, which allowed the company to circumvent standard certification processes so it could sell aircraft more quickly. Boeing's inadequate regard for safety and the FAA's complicity display an unconscionable lack of leadership at both organizations." The letter went on to compare the current crisis with Boeing's handling of Boeing 737 rudder issues in the 1990s.[430]

Andrew Skow, a former Northrop Grumman chief engineer, assessed Boeing as having good track record modernizing of the 737, but, "They may have pushed it too far."[431]

A former professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Andrew Kornecki, who is an expert in redundancy systems, said operating with one or two sensors "would be fine if all the pilots were sufficiently trained in how to assess and handle the plane in the event of a problem". But, he would much prefer building the plane with three sensors, as Airbus does.[432]

John Goglia, former member of the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), criticized Boeing and the FAA for not protecting FAA-designated oversight engineers from Boeing management pressure. Commenting on the 2016 removal of a senior engineer who had insisted on improved testing of a fire suppression system, he said that management action of this kind produces a chilling effect on others and "negates the whole system."[376] He also criticized Congress for pushing the FAA to delegate even more to the industry, as it passed the 2018 FAA Reauthorization Act, which mandated further expansion of the ODA program. "Apparently, Congress didn't think the FAA was delegating enough to ODA holders. [...] many of its members are also accepting campaign donations from aircraft manufacturers, such as Boeing, which clearly have an interest in pushing the FAA to delegate more and more authority to manufacturers with as little oversight as possible".[433]

Author, journalist, and pilot William Langewiesche wrote his first article in The New York Times Magazine, saying: "What we had in the two downed airplanes was a textbook failure of airmanship.".[6][434] To which, another aviation author, Christine Negroni wrote back "the argument that more competent pilots could have handled the problem is not knowable to Langewiesche and it misses the most basic tenet of air safety anyway."[435] She explains that an accident investigation is not about blame, is not only about what happened, but rather strives to identify the root causes. The counterpoint's essence is that Langewiesche downplays the "failure of systems and processes that put a deeply flawed airplane in the hands of pilots around the world". Captain "Sully" Sullenberger also replied to the paper by a letter to the editors, in which he says: "I have long stated, as he does note, that pilots must be capable of absolute mastery of the aircraft and the situation at all times, a concept pilots call airmanship. Inadequate pilot training and insufficient pilot experience are problems worldwide, but they do not excuse the fatally flawed design of the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) that was a death trap."[436][437]

In September, aerospace analyst Richard Aboulafia said about Boeing: "This is an engineering company, it needs an engineering culture and engineering management; It deviated pretty far from this at the time when the MAX was being developed."[438]

Lawyers, analysts and experts considered Boeing's public statements to be contradictory and unconvincing.[439] They said Boeing refused to answer tough questions and accept responsibility, defended the airplane design and certification while "promising to fix the plane's software", delayed to ground planes and issue an apology, and yet was quick to assign blame towards pilot error.[440][441]

Engineering experts have pointed out misconceptions of the general public and media concerning the 737 MAX characteristics and the crashes.[442]

Others

Consumer advocates

In May 2019, the consumer advocate organization Flyers Rights opposed the FAA's position of not requiring simulator training for 737 MAX pilots. It also asked to extend the comment period to allow independent experts to "share their expertise with the FAA and Boeing".[443]