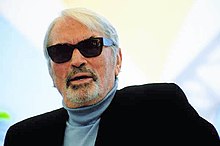

Gregory Peck

Gregory Peck | |

|---|---|

Gregory Peck in 1944 | |

| Born | Eldred Gregory Peck April 5, 1916 San Diego, California, U.S. |

| Died | June 12, 2003 (aged 87) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | San Diego State University University of California, Berkeley |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1941–2000 |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | Greta Kukkonen

(m. 1942; div. 1955) |

| Children | 5, including Cecilia Peck |

| Family | Ethan Peck (grandson) |

| Website | gregorypeck |

Eldred Gregory Peck (April 5, 1916 – June 12, 2003) was an American actor. He was one of the most popular film stars from the 1940s to the 1960s. Peck received five nominations for Academy Award for Best Actor and won once – for his performance as Atticus Finch in the 1962 drama film To Kill a Mockingbird.

Peck's other Oscar-nominated roles are in the following films: The Keys of the Kingdom (1944), The Yearling (1946), Gentleman's Agreement (1947), and Twelve O'Clock High (1949). Other notable films in which he appeared include Spellbound (1945), The Gunfighter (1950), Roman Holiday (1953), Moby Dick (1956, and its 1998 mini-series), The Big Country (1958), The Guns of Navarone (1961), Cape Fear (1962, and its 1991 remake), How the West Was Won (1962), The Omen (1976), and The Boys from Brazil (1978).

U.S. President Lyndon Johnson honored Peck with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969 for his lifetime humanitarian efforts. In 1999, the American Film Institute named Peck among Greatest Male Stars of Classic Hollywood cinema, ranking him at No. 12.

Early life

Eldred Gregory Peck was born on April 5, 1916, in San Diego, California to Bernice Mae "Bunny" (née Ayres; 1894–1992), and Gregory Pearl Peck (1886–1962), a Rochester, New York-born chemist and pharmacist. His father was of English (paternal) and Irish (maternal) heritage,[1][2] and his mother was of English and Scots ancestry.[3] She converted to her husband's religion, Roman Catholicism, when she married Gregory Pearl, and Peck was raised as a Catholic. Through his Irish-born paternal grandmother Catherine Ashe (1864–1926), Peck was related to Thomas Ashe (1885–1917), who participated in the Easter Rising less than three weeks after Peck's birth and died while being force-fed during his hunger strike in 1917.

Peck's parents divorced when he was five, and he was brought up by his maternal grandmother, who took him to the movies every week.[4] At the age of 10, he was sent to a Catholic military school, St. John's Military Academy in Los Angeles. While he was a student there, his grandmother died. At 14, he moved back to San Diego to live with his father. He attended San Diego High School,[5] and after graduating, he enrolled for one year at San Diego State Teacher's College (now known as San Diego State University). While there, he joined the track team, took his first theatre and public-speaking courses, and pledged the Epsilon Eta fraternity.[6] Peck, however, had ambitions to be a doctor, and the following year, he gained admission to the University of California, Berkeley,[7] as an English major and pre-medical student. Standing 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m), he rowed on the university crew. Although his tuition fee was only $26 per year, Peck still struggled to pay, and took a job as a "hasher" (kitchen helper) for the Gamma Phi Beta sorority in exchange for meals.

At Berkeley, his deep, well-modulated voice got him attention, and after participating in a public speaking course, he decided to try acting.[8] He was encouraged by an acting coach, who saw in him perfect material for university theatre, and he became more and more interested in acting. He was recruited by Edwin Duerr, director of the university's Little Theater, and appeared in five plays during his senior year, including as Starbuck in Moby Dick.[8] Peck would later say about Berkeley that "it was a very special experience for me, and three of the greatest years of my life. It woke me up and made me a human being."[9] In 1997, Peck donated $25,000 to the Berkeley rowing crew in honor of his coach, the renowned Ky Ebright.

Stage career

Peck was not able to graduate along with his friends because he lacked one course. His college friends were concerned for him, and wondered how he'd get along without his degree. "I have all I need from the University", he told them, re-assuringly. Peck dropped the name "Eldred", and headed to New York City to study at the Neighborhood Playhouse[8] with the legendary acting teacher Sanford Meisner. He was often broke, and sometimes slept in Central Park.[10] He worked at the 1939 World's Fair as a barker, and Rockefeller Center as a tour guide for NBC television, and at Radio City Music Hall.[8] He dabbled in modelling before, in 1940, working in exchange for food, at the Barter Theatre in Abingdon, Virginia,[8][11] where he appeared in five plays, including Family Portrait and On Earth As It Is.[11]

His stage career began in 1941, when he played the secretary in a Katharine Cornell production of George Bernard Shaw's play The Doctor's Dilemma. Unfortunately, the play opened in San Francisco just one week before the attack on Pearl Harbor.[12] He made his Broadway debut as the lead in Emlyn Williams' The Morning Star in 1942.[8] His second Broadway performance that year was in The Willow and I with Edward Pawley. Peck's acting abilities were in high demand during World War II because he was exempted from military service, owing to a back injury suffered while receiving dance and movement lessons from Martha Graham as part of his acting training. Twentieth Century Fox later claimed he had injured his back while rowing at university, but in Peck's words, "In Hollywood, they didn't think a dance class was macho enough, I guess. I've been trying to straighten out that story for years."[13]

In 1947, Peck co-founded The La Jolla Playhouse, at his birthplace, with Mel Ferrer and Dorothy McGuire.[14] This summer stock company presented productions in the La Jolla High School Auditorium from 1947 until 1964. In 1983, the La Jolla Playhouse re-opened in a new home at the University of California, San Diego, where it still thrives today. It has attracted Hollywood film stars on hiatus, both as performers and enthusiastic supporters, since its inception.

Film career

Rapid critical and commercial success (1944-1946)

After about 50 plays in total, including three short-lived Broadway plays, four or five on road tours, and the rest during summer theater,[15] Peck was offered his first film role, the male lead in the war-romance Days of Glory (1944), directed by Jacques Tourneur, alongside top-billed ballerina Tamara Toumanova.[8] Peck portrayed the leader of Russian guerrillas resisting the Germans in 1941 who stumble across a beautiful Russian dancer (Toumanova), who had been sent to entertain Russian troops, and protect her by letting her join their group.[8][16] The film lost money disappearing from theatres quickly[17][18] and is described by one critic as "sincere, but plodding,"[19] and by two others as having too many long speeches.[20][21] Despite this, Peck's star power was evident,[8][22] even if one critic considered his acting in Days of Glory a little stiff.[23] Hollywood movie producers became very interested in him, but rather than signing an exclusive long-term contract with one studio, he decided to free-lance, signing non-exclusive contracts with four studios,[24] including an unusual dual contract with 20th Century Fox and Gone With the Wind producer David O. Selznick.[25] This enabled him to choose only roles that interested him and resulted in him landing roles in several big budget films over the next few years.[8]

These films were 20th Century Fox's lavish The Keys of the Kingdom (1944) and, rapidly, three movies co-starring significant female stars: The Valley of Decision (1945) with Greer Garson at the height of her career having received four straight Academy Award nominations for Best Actress, winning in 1942 for Mrs. Miniver; Spellbound (1945) starring Ingrid Bergman who had just won the Academy Award for Best Actress for Gaslight (1944);[8] and The Yearling (1946) with the up-and-coming Jane Wyman who had just appeared in movies with Cary Grant and with Ray Milland in The Lost Weekend for which Milland won the Academy Award for Best Actor.

Film historian David Thompson wrote that right from his debut on screen Peck was always a star and almost always a box office success.[26] From 1945 to 1951, Peck was among the most successful Hollywood Stars as The Valley of Decision was the highest grossing movie of 1945; Spellbound was the third highest grossing movie of 1946; Duel in the Sun and The Yearling were second and ninth, respectively, for 1947; and, Gentlemen's Agreement was eighth for 1948. Then he was back in the top ten in 1950 with Twelve O'Clock High placing tenth that year and, in 1951, David and Bathsheba was the top grossing film of the year.[27][28]

His rapid success was further shown by him being nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor four times in the first six years of film career, those being for: The Keys of the Kingdom (1944), The Yearling (1946), Gentleman's Agreement (1947), and Twelve O'Clock High (1949).ref name="autogenerated589">Monush, Barry (New York, 2003), "The Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors", Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, pg.589.</ref>

The Keys of the Kingdom (1944) features Peck as a 80-year-old Roman Catholic priest looking back at his epic undertakings during over half a century spent as a determined, self-sacrificing missionary in China.[29][30] The film shows him aging from his 20s to 80 and he is in almost every scene.[8][31] At the time of release, one reviewer said the movie successfully conveyed the impact of "tolerance, service, faith and godliness" and that Peck's performance was excellent.[29] Another evaluated the script as tedious but said Peck was forceful.[32] Peck received his first nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor and the movie had three other nominations, including for cinematography.[33]

In the twenty-first century, some critics describe The Keys of the Kingdom as overlong,[8] as having stilted dialogue and dull patches,[34] or as long but generally good.[35] One critic asserts the movie is simply different from what most of today's viewers are accustomed - it is "slow-moving, patient, expository, with long scenes of dialogue and character building," - and that it is inspiring with many moving scenes featuring a "sincere, believable, dynamic performance" from Peck "ranging from soft-spoken compassion to almost retaliatory loathing."[36] Some other critics others agree Peck's performance is excellent.[37][38] While Keys of the Kingdom is not viewed by many movie watchers today,[39] in the mid-1940s it catapulted him to stardom.[8][40]

In The Valley of Decision (1944), an extravagant, sprawling romantic drama about intermingling social classes, Peck plays the eldest son of a wealthy steel mill owner in 1870s Pittsburgh who has a romance with one of his family's maids, who is played by Greer Garson.[28][8] Garson plays the protagonist who tries to smooth relations between her friends and family and Peck's, which get especially tense when the mill workers strike,[41] and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress.[42] A contemporary review described the first half of the movie as formulaic and somewhat contrived, but the final section as having authority and depth, while describing Peck's performance as "quietly commanding."[41] Another review states the tale "is movingly dealt with" and that "Peck has the personality and ability to command attention in any scene."[43] In recent years, the The Valley of Decision film has been evaluated as polished[19] and above-average.[44] Some summaries of Peck's career and comprehensive movie review books or websites do not review the movie[45][46][47] and the movie is not viewed much today,[48] despite the fact it was North America's biggest grossing movie of 1945.[27]

Peck's next film was the suspense-romance Spellbound (1945), the first of two movies he would do with Alfred Hitchcock. Peck starred opposite the beautiful Ingrid Bergman as a man who has amnesia and is mistaken as being the new director of the psychiatric facility where the elegant Bergman works as a psycho-analyst, but who also has disturbing visions that suggest he committed a murder.[49] Released at the tail end of 1945, and starring two of the biggest, most attractive new stars in Hollywood, Spellbound was a huge hit that ranked as the third most successful film of 1946.[27][28] It continued the rise of Peck into a Hollywood star and even a major sex symbol.[50] Producer David O. Selznick noted that during preview tests of the movie, the women in the audiences had big reactions to the appearance of Peck’s name on the screen and that during the first few scenes he appeared in they had to be shushed to quiet down.[51] It was nominated for six Academy Awards including Best Picture,[52] although it was not in the National Board of Review's top ten films of the year.[53]

Peck and Hitchcock were described as having a cordial but cool relationship.[54] The Master of Suspense had hoped that Cary Grant would accept the male lead role and was disappointed when he did not. He accepted Peck in the role, but perceived him as a bit of a country boy, even though Peck had lived in urban California since his preteen years; Hitchcock tried to socialize with him by offering him friendly advice on things, such as on what color suites to wear and about fine wines and spirits.[55] Hitchcock was not as forthcoming on advice for Peck's acting, saying "I couldn't care less what your character is thinking. Just let your face drain of all expression" even though Peck was a relatively inexperienced romantic leading man hungering for direction.[56] Peck later said he thought he was too young when he first worked with Hitchcock and that Hitchcock's indifference to a character's motivation, which Peck was big on, shook his confidence.[57] Peck clicked romantically with his screen and overnight partner Bergman, so their screen romance was convincing.[58]

Spellbound was well-received at the time, with one reviewer evaluating it as "a superior and suspenseful melodrama,"[59] and another as a “masterful psychiatric thriller....with compelling performances from Bergman and Peck."[60] Another critic described it as a "moving love story" and that "the quality of story-telling is extraordinarily fine” complimenting Peck's performance as "restrained and refined" which is "precisely the proper counter" to Bergman's performance.[61] Critical opinion of Spellbound has been mixed in recent decades with different critics assessing it as: absorbing and unique;[19] intriguing but verbose;[49] decent;[62] and, very good due to its suspense and visuals, and Peck is strong, but the psychoanalytic ideas are obsolete.[63] By contrast, other critics argue many aspects of the narrative are unrealistic, including the quickness of Peck’s recovery and of Bergman’s falling in love with Peck;[64][65] and one says that Peck "fails to elicit sympathy in the way he does so often in other films."[66] Another film scribe describes the film as "a fascinating psychological thriller which suffers from the wooden Peck in the lead role."[67]

In Peck's next film he played a pristine,[26] kind-hearted father, opposite wife Jane Wyman, whose son finds and insists on raising a three-day-old fawn in 1870s Florida, in The Yearling (1946).[49] Upon release, one critic evaluated it as a film which "provides a wealth of satisfaction that few films ever attain" as it realizes on the screen the true emotions between a father and a son and of the son for a pet fawn.[68] Other reviewers said it provides "an emotional experience seldom equaled"[69] and is heart-warming with impressive underlying power.[70] Peck's good-humoured and affectionate performance was praised with one critic writing "the film is acted with rare perfection."[71] The Yearling was a box office success and landed six Academy Award nominations, including for Best Picture, Best Actor and Best Actress, and Peck won the Golden Globe for Best Actor.[72] In recent decades, it has been described as: remarkable;[73] "one of the best-made and most-loved family films of its day";[8] and, as exquisitely filmed with memorable performances.[19][74]

Then Peck took a somewhat smaller role, his first "against type", as a cruel, amoral cowboy in the extravagant western soap opera Duel in the Sun (1946) with top-billed Jennifer Jones as the provocative, temptress object of Peck's love, anger and uncontrollable sexual desire.[75][76] Their interactions are described by film historian David Thomson as "a constant knife fight of sensuality."[77] Also starring Joseph Cotton as Peck's righteous half brother and competitor for the affections of the Jones, the movie was resoundingly criticized, and even banned in some cities, due to its lurid, sexual nature,[78][79] even after some of the most sizzling scenes between Peck and Jones had been cut.[80] The publicity around the eroticism of Duel in the Sun and the sexy new image of Jones,[81] one of the biggest advertising campaigns in history,[78] and a new tactic of opening the movie in numerous theaters in each city across the entire U.S. at once,[82] resulted in the movie being the second highest grossing movie of both 1947 and the 1940s overall.[83] Jones landed a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actress and some audiences are amazed at the passion in her performance,[84] even though one critic says the movie did not establish her as either a sex goddess or a top female movie star which had been producer David O. Selznick's aims.[85]

The film, nicknamed "Lust in the Dust, was "universally drubbed" by the critics,[81][86] with one saying it "fluctuates between the repellent and the ridiculous,"[87] and a second saying it is "spectacularly disappointing" with a banal story and "juvenile slobbering over sex."[88] In recent decades Duel in the Sun has been described as: overblown and vulgar;[78] mostly poorly acted;[89] having a dubious script and being "undeniable hooey but also candybox entertainment";[81] an "often stupid sex-western" but also engrossing with some memorable scenes;[19] "demented, delirious" and "visually resplendent;"[79], and, "wacky and grandiose" with "performers mostly relegated to the background."[90] Peck, it is said, "credibly holds his own against the scene-stealing veterans" in the movie,[91] and makes the bad brother credibly vicious,[92] although another critic said he could have been livelier.[78]

Critical successes and commercial lows (1947-1949)

Peck's next release was the modest-budget, serious adult drama, The Macomber Affair (1947), about a couple who go on an African hunting trip guided by Peck that is interrupted by the husband getting shot.[93][94] Although the performers never left the United States, film footage of lions and water buffalo and landscape from Africa, specifically shot for the movie, was inserted into the movie, in what one reviewer evaluated as very effective at showing realistic, exciting action and background.[94] Peck was very active in the development of the film, including recommending the director, Zoltan Korda, and in later years would say he was disappointed the film was overlooked by the public upon its release and in later decades.[93] This was the case despite the movie receiving reviews that, while citing some poor dialogue and a poor ending, evaluated the movie as exciting and suspenseful,[94] absorbing with excellent hunting scenes,[95] and even a "brilliantly good job" of bringing an Ernest Hemingway book to the screen.[96]

In November 1947, Peck's next film, the landmark Gentleman's Agreement (1947), directed by Elia Kazan, was released and was immediately proclaimed as Hollywood's first attack on anti-Semitism.[97][98] Peck portrays a New York magazine writer who pretends to be Jewish so he can experience personally the hostility of bigots.[99] It was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including Peck for Best Actor, and won Best Film and Best Director, picks which the New York Film Critics Circle and the Golden Globes affirmed.[100] It was also a hit, challenging for the position of top grossing film of 1948 with $3.9 million, $600,000 behind the top film.[100] Peck would indicate in his later years that this was one of his movies of which he was most proud.[101]

Upon release, Gentleman's Agreement was widely praised for both its courageousness and its quality.[102][103][104] It was described as: a “brilliant blow against racial and religious intolerance";[105] explosive, exciting and punch-laden;[106] and, as a stirring, “overwhelming emotional experience” “with great dramatic depth and force”, strong direction, and a masterful screenplay.[107] Peck’s performance has been described as very convincing by many critics, both upon release and in recent years.[108][109][110][111][112] In the last three decades, one critic has written that Gentleman's Agreement "may have been an important film....but was never a good film,[113] and some other critics concur with this assessment, citing it as preachy and slow moving,[114][115] and, in some cases, also assessing Peck’s performance as unconvincing.[116][117] On the other hand, some current critics argue it only seems tame and slow-moving today because expectations for films are different today,[118][8][119] with one adding that our knowledge of society is also much greater which lessens the film's impact on viewers.[120] Some other critics have said that it is engrossing and solidly made, period.[121][122][123]

Peck's next three releases were each commercial disappointments. The first of these, the Paradine Case (1947), was his second and last film collaborating with Alfred Hitchcock. When producer David O. Selznick insisted on casting Peck for the movie, Hitchcock was apprehensive, questioning whether Peck could properly portray an English lawyer, something he would say again years later.[124] As well, The Paradine Case ended up being an unhappy production for both of them, not apparently through any actions of each other; Selznick desperately wanted a hit and ended up rewriting parts of the script after watching each days' film footage[125] and in some cases directed Hitchcock to re-shoot scenes in a less Hitchcockian manner.[126] In later years, Peck did not speak fondly of the making of the movie[125] and when he was once asked which of his films he would burn if he could, he immediately named The Paradine Case.[127]

Released at the tail end of 1947,The Paradine Case was a British-set courtroom drama about a defense lawyer fatally in love with his client.[125][77] It had an international cast including Charles Laughton, Ethel Barrymore (who received a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination), and Italian beauty Alida Valli, as the accused, in her American film debut.[128] Upon release the movie had good reviews strongly complimenting Peck's performance,[128][129] but the public was not impressed, and The Paradine Case ended up only re-cooping half of its lavish $4.2 million cost.[125] In recent decades, the film has been described as stagy,[19] dreary,[8] verbose,[19][125][130] slow-moving,[131] and never building dramatically despite strong performances and "some instances of Hitchcock's visual flair."[125] Another critic assesses the plot as predictable, but praises Peck as being "vulnerable yet believable in a role that requires significant delicacy of touch" as some of his character's actions are hard to fathom.[65]

Peck was next cast sharing top billing with Anne Baxter in the western Yellow Sky (1948), that being the name of the ghost town that Peck’s group of bank robbers seek refuge in, and then encounter the independent tomboy, Baxter, and her grandfather.[132] Reviews then and since, rate the film highly based on its: brilliant, atmospheric direction; rousing action; impressive but sparse dialogue; and, shining performances, including from Peck and Baxter.[133][134][135][136][137] The magnificent, stark cinematography of the landscape is also cited.[138][139] Some critics do cite Peck’s character’s conversion ("one of those agreeable bandits who need only a shave and the influence of a good woman to turn them into thoroughly decent citizens")[140] as being slightly unbelievable,[141][142] or the romance as partly contrived,[143] but still rate the film as superior. The public wasn’t as receptive as the movie was only moderately commercial successful.[144]

The year after, Peck was paired with Ava Gardner for their first of three movies together in The Great Sinner (1949), an opulent period drama-romance where a Russian writer, Peck, becomes addicted to the vice (gambling) he is researching.[145][146] The film was not well-received by reviewers; one called it “pompous and dull entertainment”,[147] while another noted it was slow moving with uninteresting dialogue,[148] and a third labelled it dreary with a weak script.[149] A recent reviewer has labelled it "murky and talky,"[150] although another one assesses Peck as powerful and Gardner as ravishing.[151] The public was not interested and stayed away.[152][153]

Later in 1949, Twelve O'Clock High (1949), the first of many successful war films in which Peck embodied the brave, effective, yet human, fighting man, was released. Based on real characters and events, Peck portrays the newly appointed commander of a U.S. World War II bomber squadron who is tasked with whipping the squadron into shape, but then breaks down emotionally because of the stress of the job[154] The National Board of Review ranked it in their top ten films of the year[155] and it received four Academy Award nominations, including for Best Picture.[156] Peck was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor and won that title from the New York Film Critics Circle.[72] and film historian Peter von Bagh considers Peck's peformance as Brigadier General Frank Savage to be the most enduring of his life.[157] Twelve O'Clock High was also a commercial success finishing tenth in the 1950 box office rankings.[72][158]

Upon release, Twelve O'Clock High was lauded by critics upon its release for its "rugged realism and punch" and was described as a "top-flight drama".[159] Another reviewer said the plot was expertly presented and that the film had a sharp emotional pull.[160] Film critics of the 1990s and since still hold a high opinion of Twelve O'Clock High[161][19] with one critic writing it is "probably the best picture about the pressures which war imposes on those at the top"[162] and another declaring it the best film of 1949.[155] Another critic says it is a very fair account of leadership and looks very realistic.[163] Peck's performance is described as flawless,[164] excellent[19] and riveting.[77]

Worldwide fame (1950-1953)

As the decade turned, Peck was back in a couple of westerns, the first being The Gunfighter (1950), directed by Henry King, who had directed Twelve O'Clock High. Peck is the aging "Top Gun of the West" who is now weary of killing and wishes to retire with his wife and child that he has not seen for many years.[165][166] Peck and King did a lot of photographical research about the Wild West Era and had discovered that most cowboys had mustaches, or even beards, and wore relatively beat-up clothing, so Peck decided to wear a mustache in a film role for the first time to give his character greater authenticity.[167][168][169] The Gunfighter did only fair but disappointing business at the box office,[170][171] and the studio chief blamed Peck's mustache for turning potential female film-goers off, because most women wanted to see usual handsome, clean-shaven Peck, not the authentic-cowboy Peck.[168] Peck later said when the studio chief saw the mustache two weeks into the shoot, he wanted to re-shoot everything, but balked when he was told the cost, which was actually double the real cost as the production manager had been persuaded by Peck and King to inflate the amount.[168][172] A second reason for the disappointing box office is probably that audiences did not expect to see, and did not want to see, the handsome, big star Peck in such a grim, sparse, understated film.[168]

The Gunfighter, which is a pyschological western, a character study with little action,[169][173] received solid reviews upon release, as did Peck's performance, with one critic describing his character as fascinating.[174][175] The movie has gained in critical appreciation over the years being admired for its superb production, gritty suspense and melancholy realism,[169][176][177] plus its compelling story (which was Oscar nominated).[178] It is often rated as a seminal movie in the western's move towards more psychological depth,[177][179][19] with Peck's performance being evaluated as impressive, dazzling and deeply felt.[177][8][169][180][19]

The other western which Peck was cast in, against his will, was Only the Valiant (1951), a low-budget movie with obvious artificial production design.[181] Peck disliked the script and later labeled the movie as the low point of his career.[181][8] Peck had eventually signed a contract with producer David O. Selznick, and Selznick sold his services to Warner Bros for this movie after he ran into financial difficulties.[181] The plot of the movie is a very common one: "an unpopular, strict leader gathers together a rag-tag group of men and leads them on an extremely dangerous mission, turning them into a well-oiled fighting machine by the end and earning respect along the way."[182] In this case, Peck is a U.S. army captain and the mission is to protect an undermanned army fort against the warring Apache.[183][181] The romantic interest of Peck in the movie, and after hours as well, was less-known, troubled Barbara Payton.[184][185] While reviews were moderate at the time,[186] this little remembered picture,[187] that is not included in most film guides,[46][188] is assessed today as disappointing with a routine plot[181] or having a poor sceenplay made watchable by good performances, especially Peck's.[182][189]

Also released in spring 1951 in the United Kingdom (fall in North America), was Peck’s first movie of four in eight years portraying a commander at sea. Based on a popular British novel, Captain Horatio Hornblower features Peck as the commander of a war ship in the British fleet during naval battles against the French and Spanish in the Napoleonic Wars, a commander who also finds romance in-between the swashbuckling.[190] Peck was attracted to the character, saying “I thought Hornblower was an interesting character. I never believe in heroes who are unmitigated and unadulterated heroes, who never know the meaning of fear.”[191] The role had been originally intended for Errol Flynn, but he was felt to be too old by the time the project came to fruition.[192] Captain Horation Hornblower was a box office success finishing ninth for the year in the U.K.[193] and seventh in the North America.[194]

Some reviews of Captain Horatio Hornblowerin 1951 lauded Peck’s performance as providing “the proper dash and authenticity to the role”[195] and as accurately conveying both a ruthless captain at war and a tender man nursing a woman through yellow fever.[196] In the twenty-first century, reviews of Peck with one critic asserting that Peck would be nobody’s first choice for the role, but conceded he was able to “deliver a combination of warmth and solemn earnestness.”[197] Another critic assesses Peck as "a little restrained for the character,"[198] while another argues Peck is excellent, bringing his “customary aura of intelligence and moral authority to the role.”[199] The same reviewers (then and recent) all rate the action scenes in the film as strong, realistic and well-filmed, although one cites the dialogue as being "stilted at times”.[200]

An even bigger budget movie featuring Peck, his third directed by Henry King, was released in North America a month before Captain Horatio Hornblower. David and Bathsheba, a lavish Biblical epic, was top grossing movie of 1951.[201] The two-hit-movie punch elevated Peck to the status of Hollywood mega-star.[202] David and Bathsheba tells the story of David (Peck), who slayed Goliath as a teenager, and, later, as beloved King, becomes infatuated with the luscious Bathsheba, played by Susan Hayward, and then, after much soul-searching, sends her soldier husband into a certain-death battle. This enables David to romance Bathsheda, after which God devastates the kingdom.[203][204]

Peck’s performance in David and Bathsheba was evaluated upon release as authoritative,[205] commanding and expertly shaded,[206] and credible.[207] In recent years critics have described it as "a trifle stilted", but supplying the "requisite power and charisma",[208] forceful,[209] or fair.[19] In 1951, the movie was described by one reviewer as providing “a reverential and sometimes majestic treatment” of the story, that "avoids pageantry and overwhelming concocted spectacle”, and makes it points with “feeling and respect”, despite being verbose.[210] Another critic said the story was a satisfying work “performed with dignity and restraint” with some dull spots while lacking excitement,[211] while another said it was a big picture in every respect with excellent casting.[212] By contrast, in recent decades one critic has described the movie as “filled with the kind of bombast and stilted melodrama that is to be expected” by Biblical epics and as “ultimately sterile”,[213] whereas another critic describes it as a “character-driven” film.[214] Other critics have praised the strong production values,[19] such as excellent cinematography, sets and costumes[215] (the film received Academy Award nominations for all three),[42] but question the direction,[77] and assess the screenplay as slightly long-winded,[216] boring,[19] or overblown,[217][218][77] even though it was also Oscar-nominated. Another assessment is that it “paled in comparison to other large-scale melodramas," [219] which could be the reasons for its low level of viewing in recent decades.[220]

Peck was back in a seafaring adventure-romance in his next movie, The World in His Arms (1952). He portrays a seal-hunting ship captain in 1850 San Francisco who romances a Russian countess played by Ann Blyth and ends up engaging a rival sealer played by Anthony Quinn in a sailing race to Alaska.[221][222] In 1952, critics called it lively and engrossing,[223] exciting and colourful,[224] and as having hearty, salty action with a good cast.[225] In the twenty-first century, two reviewers trumpet its thrilling, realistic, sailing race centerpiece[226] with one adding “superb sea footage, lots of action and a robust relationship between Peck and Quinn combine to make (it) highly enjoyable,”[227] while another critic describes it as entertaining.[19] One twenty-first century critic also commented that Peck is "a superb actor, who brings enormous skill to the part but who simply lacks the overt derring-do and danger that is part of the role."[228] The film was moderately successful.[229][230]

About a year after David and Bathsheba was released, Peck was on theater screens with Susan Hayward again, with Henry King as the director, again, in an adventure-romance, again, in a top grossing movie, again (ranking fourth for 1952).[27] The Snows of Kilimanjaro , based on an Ernest Hemingway short story, stars Peck as a self-concerned writer looking back on his life, particularly his romance with his first wife played by Ava Gardner, while he slowly dies from an accidental wound while on a African hunting expedition and his current wife, Hayward, nurses him.[231] While reviews at the time were mixed,[232][233] they said the techni-colour cinematography and art direction/sets (which were both Oscar-nominated) that enabled the characters to have convincing scenes in several European and African locales, including with wild animals, were stunning, exquisite and magnificent, a view with which most modern critics agree.[234][235][236][237] The same reviewers often cite the dialogue as unnatural or rambling while some cite the story as unconvincing, but most praise Peck’s performance, although one writer feels Peck was mis-cast and his facial expressions were too bland to portray the writer, therefore, overall, not recommending the movie.[238] One writer says The Snows of Kilimanjaro “is less a compelling film than a piece of film history”.[239]

Peck’s next movie was his “first real foray into comedy”[8] and he was working with director William Wyler, who had not made a comedy since 1935,[240] and co-starring with Audrey Hepburn, a twenty-four year-old newcomer in her first significant film role;[241] yet it turned out as a “genuinely magical romance that worked beyond all expectations.”[8] Roman Holiday (1953) has Peck playing a reporter who ends up escorting a young princess on a whirlwind 24-hour tour of Rome after she sneaks out of her high-security hotel while on a tour of European capitals.[242][243] Roman Holiday was a commercial success finishing 22nd in the box office in 1953, its first calendar year of release,[244] but continuing to earn money into 1955 with “modern sources noting it earned $10 million total at the box office”.[245] It was nominated for 8 Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Director and Screenplay, with Hepburn winning for Best Actress, a pick which the Golden Globes, New York Film Critics Circle and the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTAs) echoed, a rare occurrence; Peck was nominated for a BAFTA for Foreign Actor.[246] At the Golden Globe awards held in early 1955, Peck and Hepburn were named the World Film Favorite Award winners for their respective genders; Peck had also won the award in 1950.[27]

As had been the case with several movies before, Peck’s role in Roman Holiday had originally been offered to Cary Grant, who turned it down because the part appeared to be more of a supporting role to the princess.[247] Peck had the same concern, but was persuaded by Wyler that the on-site filming in Rome would be an exceptional experience, and accepted the part, even eventually insisting that Hepburn's name be above the title of the film (just beneath his) in the opening credits.[248] Peck later said he wasn't just being nice when he insisted on that saying he had told his agent "I’m smart enough to know this girl’s going to win the Oscar in her first picture, and I’m going to look like a damned fool if her name is not up there on top with mine.”[249]

Upon release of Roman Holiday, film critics said “Peck makes a stalwart and manly escort...whose eyes belie his restrained exterior”[250] and that Peck was excellent as he played the role with “intelligence and good-humored conviction.”[251] One critic assessed the movie as a “charming, laugh-provoking affair that often explodes into hilarity” and as having a “delightful screenplay that sparkles with wit and outrageous humour.”[252] Other critics said it contained “laughs that leaves the spirits soaring”[253] with a smart script and poignant scenes so it “zips along engrossingly” with “chuckles timed with a never-flagging pace”.[254] In recent decades, one writer has written that Roman Holiday looks old-fashioned, ponderous and too much like a travelogue, but in the 1950s it seemed fresh and enchanting”, stating that today it is modestly entertaining, but concedes that Peck "is less tree-like than usual” putting in a charming performance.[255] Other critics have praised the movie, making comments such as: "utterly charming”,[19][256] a “charming love story” with “marvelous performances”;[257] magical with both stars giving excellent performance;[258] and, “an enormously enjoyable romp” that is one of films’ “most enduring romances” with "Peck at his most charismatic".[259]

Overseas and New York (1954-1957)

Peck based himself out of the U.K. for about eighteen months between 1953 and 1955. This was because new US tax laws had drastically raised the tax rate on high income earners, but the tax amount due would be reduced if you worked outside the country for extended periods.[260] As a result, in addition to Roman Holiday filmed in Rome, his three following films were shot and set in London, Germany and Southeast Asia.

The film shot in London was another comedy, The Million Pound Note (1954), one where Peck plays the clear central character. It was based on a Mark Twain satirical short story.[261] Peck later said he have loved making the film because “no expense was spared on the best and sometimes ornate interior sets” and “he was given probably the most elegant wardrobe he had ever worn in film.”[262] Peck plays a penniless American seaman in 1903 London who is given a $1 million pound bank note by two rich, eccentric brothers who wish to ascertain if he can survive for one month without spending any of it.[263] Two reviewers said the production is delicious, but one of them said the dialogue and performance lacks a certain bounce to make it “spark with humor or glow with warmth and charm”,[264] while the other wrote the movie is unsure if it is "breezy satire" or a "fancy period romance" and that “Peck’s touch with comedy is light, but guarded, almost suspicious.”[265] Another reviewer wrote the movie “suffers from the protracted exploitation” of the basic premise which is only amusing for so long.[266] Overall, reviews were mixed and the film performed only modestly at the box office.[267]

Berlin and Munich were the filming locations for Night People (1954), which had Peck portraying a US army military police colonel investigating the kidnapping of a young American soldier.[268] Peck later stated that the role of was one of his favorites, because his lines were "tough and crisp and full of wisecracks, and more aggressive than other roles" he'd had.[269] Two critics described it as a first-rate drama with exciting, well-filmed action, although one assessed the screenplay as strong (it was Oscar-nominated),[270] while the other felt the screenplay had no complexity and had one-dimensional characters.[271] Despite decent reviews overall, the film did poorly at the box office.[272]

Next, Peck was in Sri Lanka and then back in the UK for the shooting of his second movie as a North American bomber commander who has strong emotional problems during WWII, The Purple Plain (1954).[273] Peck's role is as a Canadian squadron leader whose wife had been killed in a Luftwaffe bombing raid on London in 1941 and four years later in Burma he has become a killing machine with no regard for his own life, although a love affair with an alluring, young Burmese beauty was helping him regain the will to live.[274][275] When his bomber is shot down by the Japanese and crash lands in a desert with purple-hued soils (the "Purple Plain"), he and his crew have an long, arduous journey back to British territory.[276][277] The Purple Plain was hit in the U.K. where it was tenth in box office grosses for the year[278] and was nominated for a BAFTA for Best British Film;[27] however, it was a box office flop in the U.S.[279][280]

The Purple Plain opened to solid reviews with one reviewer evaluating it as a “fine dramatic vehicle”,[281] while another wrote “the extent of Peck’s agony is impressively transmitted....in vivid and unrelenting scenes.”[282] In recent years, the movie "has become one of Peck’s most respected works,”[283] with writers assessing it as absorbing[19] and impressively shot,[284] with another rating Peck’s performance as excellent.[26] Another reviewer describes The Purple Plain as a “feature-length character study revealing character subtly” through “evocative and stirring visuals” that advance “both the story and our understanding of the lead character,” adding that “Peck is astonishing, giving the layered, intense yet nuanced performance that deserves major awards."[285]

Peck’s popularity seemed to be on the wane in the U.S.[8] That was not the case in the U.K. though, where a poll named him the third most popular non-British movie star. [286] Peck did not have a film released in 1955.

Peck bounced back in the U.S. with a movie set in Downtown New York, The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit (1956),[8] in which he portrays a married, ex-soldier father of three who mulls over how to proceed with his life after he starts a lucrative speech-writing job, has some other complications arise in his life, and is increasingly haunted by his deeds in Italy during WWII.[287][288] Peck’s wife was played by Jennifer Jones, a reunion from Duel in the Sun, and during the filming of a scene where the spouses argue Jones clawed his face with her fingernails, prompting Peck to say to the director “I don’t call that acting. I call it personal.”[289] The movie was successful finishing eighth in box office gross for the year[290] despite contemporary reviews being mixed. [291]

Some reviewers described The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit as extremely well-acted and very absorbing despite its 2½ hour length,[292] one saying “every minute is profitably used”, and in particular citing scenes between Peck and his boss, played by Fredric March, as very "eloquent and touching".[293] Other reviewers said it is simply too long,[294] and also impersonal, to be enjoyable.[295] Another review said it is overlong and that Peck is not always convincing, but that the Peck-March scenes are so powerful it makes the film better than average.[296] In recent years, critics have had similar, but somewhat more moderated comments about The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit,[297] although Peck’s performance is usually rated as excellent with some saying the part was tailor-made for him.[298][299] One reviewer said the spousal relationship between Peck and Jones' characters seemed fake,[300] while another observed that Jones' character seemed hysteria-prone.[301]

Peck next starred in a role that he was unsure he was right for, but was persuaded by director John Huston to take on,[302] that of Captain Ahab in Moby Dick (1956), a film adaptation of “Herman Melville’s famous story of a man’s dark obsession to kill a whale" off the northeastern U.S. Coast.[303] The movie had the ninth highest box office of the year in North America,[27] but cost $4.5 million to make (more than double the original budget) so it lost money, and was considered a commercial disappointment.[304] Peck also almost drowned twice during filming in stormy weather off the sea coasts of Ireland and the Canary Islands.[305]

"There was, and continues to be, controversy over his casting as Ahab in Moby Dick."[8] Upon opening, one review said “Peck often seems understated and much too gentlemanly for a man supposedly consumed by insane fury.”[306] Another review said Peck “holds the character’s burning passions behind a usually mask-like face. We could do with a little more tempest, a little more Joshua in the role. Mr. Peck spouts fire from his nostrils only when he has at the whale.”[307] However, another argued “Peck plays it....in a brooding, smoldering vein, but none the less intensely and dynamically.”[308] In modern times, critics have said Peck is: “often mesmerizing";[8] “more than adequate;”[309] good and “lending a deranged dignity” to the part;[19] “not half as bad as some alledged, and actually suggesting the ingrained, heroic misanthropy”;[26] a “lightweight Ahab”;[310] "neither pitiable or indomitable"; and never "vengeance incarnate" which are the things Ahab is in the novel;[311] “mis-cast” and “lacking the required demonic presence;”[312] and, mis-cast.[313] Huston always said he thought “Peck conveyed the exact quality he had wanted for the obsessed seaman.”[314] Peck himself later said "I wasn't mad enough, not crazy enough, not obsessive enough - I should have done more. At the time, I didn't have more in me."[315] He also noted he thought he "played it too much for the richness of Melville's prose, too vocal a performance" and should have played it with a cracked voice as if his vocal cords were gone.[316]

Assessments of Moby Dick have been similarly polarized with one critic in 1956 saying it is a “rolling and thundering film” with numerous things brilliantly done and is one of the great movies of the 1950s.[317] Another said the movie is "more interesting than exciting" and "does not escape the repetitiousness that often dulls chase movies."[318] In recent years, it has been assessed as: “one of most historically authentic, visually stunning and powerful adventures ever made;"[319] having some marvelous scenes and often being “staggeringly good”;[320] an “under-rated attempt to film the un-filmable;”[8] having good direction and a good screenplay;[321] having fine scenes throughout;[19] and, as having “some wonderful scenes" despite which it must be "counted as a noble failure” as the whale looks unrealistic.[322]

Peck turned to a romantic comedy next, and being allowed to choose his leading lady, chose Lauren Bacall.[323] Designing Woman (1957) is about a fashion designer and a sports writer, who meet in California on vacation, and, although each already has a romantic partner back home in New York, have a brief torrid affair and hastily get married, only to find out when they are back home that they have wildly different lifestyles, outlooks, interests and friends.[324] While the movie was mildly successful in North America and elsewhere, it did not cover its cost.[325][326][327] Upon release, one reviewer asserted that Designing Woman's good dialogue enables the comedy to succeed in stretches, but that the ending is poor,[328] while another argued the movie was clever with all eight key actors/actresses giving top-notch performances.[329] In recent years, reviewers generally say it is very funny,[330][19] (it won a Best Screenplay Oscar) with one exclaiming the director and supporting cast “have done the impossible; they’ve made....the famous stoneface....Peck, somewhat funny,” calling the film "pure entertainment" with no underlying message.[331] By contrast, another critic writes that the movie is “amazingly obscure” considering its two big stars, and feels the comedy is really just subtext for discussing issues about masculinity.[332]

Reflections on violence (1958-1959)

Peck’s next movie, the western The Bravados (1958), reunited him with 72-year-old director Henry King after a six-year gap.[333] In their six films together, King was able to draw out some of Peck's best performances,[334][335] most often in characters who appeared strong and authoritative, but in reality had inner demons and character flaws that could destroy them; only one character Peck played under for King's direction could be considered, on balance, a good person, that of Bomber Commander Frank Savage in Twelve O'Clock High.[336] Some frequent collaborations yield routine results, but Finnish film writer Peter von Bagh asserts that with Peck and King the collaboration "was primed to an ever greater creative pitch and turned out to be mutually rewarding."[337] Only their last film together, the succeeding years’ Beloved Infidel (1959), was not either a critical or commercial success. Peck once said “King was like an older brother, even a father figure. We communicated without talking anything to death. It was direction by osmosis.”[338] Peck also said "he provided me with a one-man audience, in whom I had complete trust....If I played to him and he liked it, then I was fairly confident I was on the right track."[339]

The Bravados had Peck’s character relentlessly pursuing for weeks four outlaws who he believes raped and then murdered his wife.[340] He succeeds in tracking them down and kills three of them in vengence, but a climatic twist leaves his character agonizing over whether he is any better a person than the fugitives.[341] A contemporary review rated the movie highly saying the story moves at an “unflagging pace....giving the chase colorful treatment....against eye-filling, authentic backgrounds" of beautiful natural scenery with a strong sense of suspense.[342] The film was a moderate success finishing in the top 20 of the box office for 1959.[343][27]

In recent years, The Bravados has received very mixed comments, one source labeling it as acclaimed,[344] another labeling it compelling,[19] and a third saying it has excellent cinematography, good action, and good performances, but that Peck’s “crisis of conscience....is worked out in perfunctory religious terms.”[345] One source asserts Peck's performance conveys an "ethical and charismatic radiance",[346] but two reviews argue that Peck’s performance lacks emotional conviction,[347] although one of these concedes the background scenery is gorgeous and that the climatic twist is very powerful.[348] This film is not included in some comprehensive movie guides.[49][46]

Peck decided to follow some other actors into the movie-production business, organizing Melville Productions in 1956, and later, Brentwood Productions.[349] These companies would produce five movies over the following seven years, all starring Peck,[350] including Pork Chop Hill, for which Peck served as the executive producer.[351] These and other films Peck starred in were observed by some as becoming more political, sometimes containing a pacifist message, with some people calling them preachy,[352] although Peck said he tried to avoid any overt preachiness.[353]

In 1958, Peck and his good friend William Wyler, co-produced the 2¾-hour western epic, The Big Country (1958), although it was not under Peck's production company.[354] The project had numerous problems, starting with the script, as even after seven writers had worked on it, Wyler and Peck were still dissatisfied.[355] This necessitated Peck and the screenwriters to re-write the script after each days' shooting, causing stress for the performers, who would arrive the next day and find their lines and even entire scenes different than what they had prepared for.[356] There were strong disagreements between Wyler as the director, and many of the performers, including with Peck, as Peck and Wyler had different views about the need for 10,000 cattle for a certain scene and re-shooting one of Peck's close-ups; when Wyler refused to do another take of the close-up, Peck left the set for a time.[357] Peck and Wyler did not speak again for the rest of the shoot and for almost three years afterward, but then patched things up.[358][359] Peck would say in 1974 that he had tried outright producing and acting at the same time and felt "either it can't be done or it's just that I don't do it well" adding he didn't have the desire to direct.[360]

The story for The Big Country involves Peck, a peaceful city slicker, coming west to live with his fiancée and getting in the middle of a violent feud between two cattle-ranching families over access to water on a third party’s property, with Peck eventually being forced to physically fight back.[8][361] Peck has two romantic interests in the movie, one being Jean Simmons, and Charlton Heston is one opponent he must deal with.[362] The movie was big hit finishing fourth at the box office in North America for 1958[363] and second in the U.K.[364]

Reviews for The Big Country upon release ranged from negative to somewhat positive to very positive. One critic said it had stock western characters and a very superficial, conventional story that “ends on a platitude,”[365] with which another critic agreed, adding that Peck did not get his character to come alive.[366] Another review assessed the story as serviceable, the acting as very good, the music excellent, and the cinematography of the broad landscapes as excellent, "almost appearing three-dimensional."[367] Another review said it was "a first-rate super western" and perhaps too long, but never dull.[368] In recent decades, critical opinion of The Big Country has generally risen although there is still disagreement, as one critic writes “staggering vistas and grandiose story make this an emblematic Western,”[369] while another calls it overblown.[19] Two other reviews call the script intelligent and the cinematography excellent, with one particularly citing some excellent action scenes,[169] although the other said sharper editing was necessary.[370] Another writer assesses Peck as excellent and the movie as fine.[8] Some comprehensive movie review books don’t rate the movie as warranting inclusion,[46][371] but another scribe asserts the movie is "unfairly neglected today" and "never tiresome despite its length" and says Peck was ideal for the role as "he was one of the few actors whose innate pacificism rang true."[372]

Peck next played a lieutenant during the Korean war in Pork Chop Hill (1959), which was based on a factual book about a real battle.[373] Peck‘s lieutenant was ordered to use his 135-man infantry company to take from the Chinese the strategically insignificant Pork Chop Hill because its capture would strengthen the U.S.’s position in the almost-complete armistice negotiations.[374] As executive producer, Peck recruited Lewis Milestone of All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) to direct, and although many critics label it as an anti-war film,[8][375] it has also been stated that “as shooting progressed it became clear Peck and Milestone had very different artistic visions.”[376] ”Peck wanted a realistic but relatively conventional war movie, whereas Milestone envisioned a more thoughtful reflection on the futility of war.”[377] Peck later said the movie showed “the futility of settling political arguments by killing young men. We tried not to preach; we let it speak for itself.”[378] Despite solid reviews, the film did only fair business at the box office.[379]

Most critics, both upon Pork Chop Hill's opening and in recent years, agree that it is a powerful, gritty, grim and utterly realistic rendering of battle action.[380][381][382][383][384][385] One modern review says the cinematography “depicts the heroic battle in such stark detail that the viewer can almost smell the acrd fumes of cordite and taste the dust blown from the dead ridge” labeling it as “an authentic and memorable cinematic experience.”[386] All three critics which comment on Peck’s performance laud it as excellent,[387][388] with one writing Peck's character “comes through as a born leader, and yet it is quite clear that he has moments of doubt and of uncertainty.”[389]

Peck’s second release of 1959 had him opposite Deborah Kerr in Beloved Infidel which, based on the memoirs of film columnist Sheilah Graham, portrays the romance between Graham (Kerr) and author F. Scott Fitzgerald (Peck), towards the end of which Fitzgerald was often drunk and became verbally and physically abusive.[390] It was not well received by audiences or critics, being assessed by one critic as “flat and uninteresting” with a grim-faced, monotonous performance from Peck,"[391] and by another as superficial, lacking character development, and having inconsistent acting.[392] Reviews in recent decades are similar and many scribes feel Peck was “blatantly miscast”[8][393][394][395][396] leaving him “hopelessly adrift”,[26] although one said his effort was noble.[397] The movie is little known today.[398]

Peck next starred in Hollywood’s first major movie about the implications of nuclear warfare, On the Beach (1959), which was filmed in Australia and co-starred Ava Gardner in their third and final film together.[399] Directed by Stanley Kramer and based on a best-selling book, the movie shows the last weeks of several people as they await the onset of radio-active fallout from nuclear bombs.[400] Peck portrays a U.S. submarine commander stationed in Australia who has trouble accepting that his wife and children back in the U.S. are dead, but becomes close to Gardner and then travels in the submarine northward to see if any people have survived or if Alaska is uncontaminated.[401] The film was named to the top ten lists of the National Board of Review and the New York Film Critics Circle.[27] It was successful at the North American box office finishing eighth for the year,[27] but due to its high production cost it lost $700,000. [402]

Upon opening, many reviews of On the Beach were very positive describing it as extraordinary,[403] deeply moving with good direction and “some vivid and trenchant images,”[404] or as “solid film of considerable emotional, as well as cerebral, content” with strong acting, but with a " final impact (that) is as heavy as a leaden shroud.”[405] Another review assessed it as “brilliantly executed”,[406] but questioned its realism as the characters were sedate despite facing certain death,[407] a factor a number of other critics were reported as citing.[408] In recent decades, critical opinion of On the Beach is mixed with two critics giving negative reviews citing a numbing and cliché-ridden story,[46] with one adding that, aside from Peck, it is poor acted, but does have strong cinematography.[409] Another critic assesses it as thoughtful with good performances by all.[410] Two other critics agree on assessing it as intensely powerful but flawed with some sections being too melodramatic, but one adds it is well-acted and deftly cinematographed,[411] while the other says the Peck-Gardner romance is soap opera-ish even though "Peck has rarely been so stalwart" and that the film has an “overwhelming, desperate sense of bleakness that perfectly captures the sense of hopelessness that is central to the story.”[412]

Second commercial and critical peak (1960-1964)

After having no movies released in 1960, Peck's first release of 1961 was the WWII adventure The Guns of Navarone, in which his six-man British and Greek commando team, which also includes David Niven and Anthony Quinn, undertakes a multi-step mission to destroy two seemingly impregnable cliff-top German artillery guns on the Greek island of Navarone.[79] The team of specialists (Peck is the mountain climbing expert) need to destroy the guns so British ships can evacuate across the Aegean Sea two-thousand trapped British soldiers.[79] Derived from a fact-based novel, subplots during the mission include finding a traitor in their midst, personal differences and bad history between characters, and debates about the morality of warfare,[413] with the latter being added to the novel's original story by producer/screenwriter Carl Foreman.[414] The movie was a huge hit becoming the top grossing movie of 1961,[28] and became “one of the most popular adventure movies of its day.”[415] It landed seven Academy Award nominations, including for best picture, director, and screenplay, winning for best special effects, while at the Golden Globe Awards it won for Best Dramatic Movie.[416]

Most reviews of The Guns of Navarone in 1961 were positive as illustrated by it being named the best picture of the year in Film Daily’s annual poll of critics and industry reporters.[417] One review said the movie “should have patrons firmly riveted throughout its lengthy narrative” and that there are several nail-biting sequences plus “a boffo climax”.[418]Another reviewer said it was a "robust action drama" predicting it would entertain those who like action and melodrama more than character, complex human drama or credibility.[419] A third declared it was one of those movies "that are no less thrilling because they are so preposterous" adding he “was held more or less spellbound all the way through (the) many-colored rubbish.”[420] During filming, Peck had said the fact his team seems to defeat "the entire German army" approached parody concluding the only way to make it work was for all the performers to "play their roles with complete conviction."[421] In recent decades, critics have written the movie: “boasts strong human drama and emotional involvement,” with realistic tension;[422] is a classic which maintains tension despite its length;[423] is spectacularly filmed and one of the best of its type;[79] and, "is lavish, rich and often breathtaking” despite its “triumph-against-all-odds finale" and clichéd story. [424] Two critics have said some of the dialogue, such as that discussing morality of war, should had been cut,[425] although one of those critics stills says the movie is effective.[46] The Guns of Navarone is considered to be one of the great WWII epics.[426]

Peck won the Academy Award with his fifth nomination, playing Atticus Finch, a Depression-era lawyer and widowed father, in a film adaptation of the Harper Lee novel To Kill a Mockingbird. Released in 1962, during the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the Southern United States, this film and his role were Peck's favorites. In 2003, Peck's portrayal of Atticus Finch was named the greatest film hero of the past 100 years by the American Film Institute.[427]

Mature Years (1965-1979)

Peck served as the president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1967, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the American Film Institute from 1967 to 1969, Chairman of the Motion Picture and Television Relief Fund in 1971, and National Chairman of the American Cancer Society in 1966. He was a member of the National Council on the Arts from 1964 to 1966.[428]

A physically powerful man, he was known to do a majority of his own fight scenes, rarely using body or stunt doubles. In fact, Robert Mitchum, his on-screen opponent in Cape Fear, told about the time Peck once accidentally punched him for real during their final fight scene in the movie. He felt the impact for days afterward.[429] Peck's rare attempts at villainous roles were not acclaimed. Early on, he played the renegade son in the Western Duel in the Sun, and, later in his career, the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele in The Boys from Brazil co-starring Laurence Olivier.[430]

Later work (1980 - 2000)

In the 1980s, Peck moved to television, where he starred in the mini-series The Blue and the Gray, playing Abraham Lincoln. He also starred with Christopher Plummer, John Gielgud, and Barbara Bouchet in the television film The Scarlet and The Black, about Monsignor Hugh O'Flaherty, a real-life Catholic priest in the Vatican who smuggled Jews and other refugees away from the Nazis during World War II.

Peck, Mitchum, and Martin Balsam all had roles in the 1991 remake of Cape Fear, directed by Martin Scorsese. All three were in the original 1962 version. In the remake, Peck played Max Cady's lawyer.

His last prominent film role also came in 1991, in Other People's Money, directed by Norman Jewison and based on the stage play of that name. Peck played a business owner trying to save his company against a hostile takeover bid by a Wall Street liquidator played by Danny DeVito.

Peck retired from active film-making at that point. Peck spent the last few years of his life touring the world doing speaking engagements in which he would show clips from his movies, reminisce, and take questions from the audience. He did come out of retirement for a 1998 mini-series version of one of his most famous films, Moby Dick, portraying Father Mapple (played by Orson Welles in the 1956 version), with Patrick Stewart as Captain Ahab, the role Peck played in the earlier film. It was his final performance, and it won him the Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor in a Series, Miniseries, or Television Film.

Peck had been offered the role of Grandpa Joe in the 2005 film Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, but died before he could accept it. The Irish actor David Kelly was then given the part.[431]

Politics

In 1947, while many Hollywood figures were being blacklisted for similar activities, Peck signed a letter deploring a House Un-American Activities Committee investigation of alleged communists in the film industry.

A life-long Democrat, Peck was suggested in 1970 as a possible Democratic candidate to run against Ronald Reagan for the office of California Governor. Although he later admitted that he had no interest in being a candidate himself for public office, Peck encouraged one of his sons, Carey Peck, to run for political office. Carey was defeated both times by slim margins in races in 1978 and 1980 against Republican U.S. Representative Bob Dornan, another former actor.

Peck revealed that former President Lyndon Johnson had told him that, had he sought re-election in 1968, he intended to offer Peck the post of U.S. ambassador to Ireland – a post Peck, owing to his Irish ancestry, said he might well have taken, saying, "[It] would have been a great adventure".[432] The actor's biographer Michael Freedland substantiates the report, and says that Johnson indicated that his presentation of the Medal of Freedom to Peck would perhaps make up for his inability to confer the ambassadorship.[433] President Richard Nixon, though, placed Peck on his "enemies list", owing to Peck's liberal activism.[434]

Peck was outspoken against the Vietnam War, while remaining supportive of his son, Stephen, who fought there. In 1972, Peck produced the film version of Daniel Berrigan's play The Trial of the Catonsville Nine about the prosecution of a group of Vietnam protesters for civil disobedience. Despite his reservations about American general Douglas MacArthur as a man, Peck had long wanted to play him on film, and did so in MacArthur in 1976.[435]

In 1978, Peck traveled to Alabama, the setting of To Kill a Mockingbird, to campaign for Democratic U.S. Senate nominee Donald W. Stewart of Anniston, who defeated the Republican candidate, James D. Martin, a former U.S. representative from Gadsden.

In 1987, Peck undertook the voice-overs for television commercials opposing President Reagan's Supreme Court nomination of conservative judge Robert Bork.[436] Bork's nomination was defeated. Peck was also a vocal supporter of a worldwide ban of nuclear weapons, and a life-long advocate of gun control.[437][438]

Personal life

In October 1942, Peck married Finnish-born Greta Kukkonen (1911–2008), with whom he had three sons: Jonathan (1944–1975), Stephen (b. 1946), and Carey Paul (b. 1949). They were divorced on December 31, 1955.

During his marriage with Greta, Peck had a brief affair with Spellbound co-star Ingrid Bergman.[184] He confessed the affair to Brad Darrach of People in a 1987 interview, saying: "All I can say is that I had a real love for her (Bergman), and I think that's where I ought to stop... I was young. She was young. We were involved for weeks in close and intense work."[439][440][441]

On New Year's Day in 1956, the day after his divorce was finalized, Peck married Véronique Passani (1932–2012),[442] a Paris news reporter who had interviewed him in 1952 before he went to Italy to film Roman Holiday. He asked her to lunch six months later, and they became inseparable. They had a son, Anthony Peck (b. 1956),[443] and a daughter, Cecilia Peck (b. 1958).[444] The couple remained married until Gregory Peck's death. His son Anthony is an ex-husband of supermodel Cheryl Tiegs. His daughter Cecilia lives in Los Angeles.

Peck's eldest son, Jonathan, was found dead in his home on June 26, 1975, in what authorities believed was a suicide.[445]

Peck had grandchildren from both marriages.[446] One of his grandsons from his first marriage is actor Ethan Peck.

Peck owned the thoroughbred steeplechase race horse Different Class, which raced in England.[447] The horse was favored for the 1968 Grand National, but finished third. Peck was close friends with French president Jacques Chirac.[448]

Peck was Roman Catholic, and once considered entering the priesthood. Later in his career, a journalist asked Peck if he was a practicing Catholic. Peck answered: "I am a Roman Catholic. Not a fanatic, but I practice enough to keep the franchise. I don't always agree with the Pope... There are issues that concern me, like abortion, contraception, the ordination of women ... and others."[449] His second marriage was performed by a justice of the peace, not by a priest, because the Church prohibits remarriage if a former spouse is still living, and the first marriage was not annulled. Peck was a significant fund-raiser for the missionary work of a priest friend of his (Father Albert O'Hara), and served as co-producer of a cassette recording of the "New Testament" with his son Stephen.[449]

Death

On June 12, 2003, Peck died in his sleep from bronchopneumonia at the age of 87 at his home in Los Angeles.[450] His wife, Veronique, was by his side.[451]

Gregory Peck is entombed in the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels mausoleum in Los Angeles. His eulogy was read by Brock Peters, whose character, Tom Robinson, was defended by Peck's Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird.[452][453] The celebrities who attended Peck's funeral included Lauren Bacall, Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Shari Belafonte, Harrison Ford, Calista Flockhart, Mike Farrell, Shelley Fabares, Jimmy Smits, Louis Jourdan, Dyan Cannon, Stephanie Zimbalist, Michael York, Angie Dickinson, Larry Gelbart, Michael Jackson, Anjelica Huston, Lionel Richie, Louise Fletcher, Tony Danza, and Piper Laurie.[452][454]

Legacy

The Gregory Peck Award for Cinematic Excellence was created by the Peck family in 2008 to commemorate their father by honoring a director, producer or actor's life's work. Originally presented at the Dingle International Film Festival in his ancestral home in Dingle, Ireland,[455] since 2014 it has been presented at the San Diego International Film Festival in the city where he was born and raised. Recipients include Gabriel Byrne, Jim Sheridan, Laura Dern, Alan Arkin, Annette Bening, and Patrick Stewart. On October 18, 2019, Laurence Fishburne will receive the award.

Awards and honors

Peck was nominated for five Academy Awards, winning once. He was nominated for The Keys of the Kingdom (1945), The Yearling (1946), Gentleman's Agreement (1947), and Twelve O'Clock High (1949). He won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his role as Atticus Finch in the 1962 film To Kill a Mockingbird. In 1967, he received the Academy's Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award.[456]

Peck also received many Golden Globe awards. He won in 1947 for The Yearling, in 1963 for To Kill a Mockingbird, and in 1999 for the TV mini-series Moby Dick. He was nominated in 1978 for The Boys from Brazil. He received the Cecil B. DeMille Award in 1969, and was given the Henrietta Award in 1951 and 1955 for World Film Favorite – Male.

In 1969, 36th U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson honored Peck with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor. In 1971, the Screen Actors Guild presented Peck with the SAG Life Achievement Award. In 1989, the American Film Institute gave Peck the AFI Life Achievement Award. He received the Crystal Globe award for outstanding artistic contribution to world cinema in 1996.

He received the Career Achievement Award from the U.S. National Board of Review of Motion Pictures in 1983.[457]

In 1986, Peck was honored alongside actress Gene Tierney with the first Donostia Lifetime Achievement Award at the San Sebastian Film Festival in Spain for their body of work.

In 1987, Peck was awarded the George Eastman Award, given by George Eastman House for distinguished contribution to the art of film.[458]

In 1993, Peck was awarded with an Honorary Golden Bear at the 43rd Berlin International Film Festival.[459]

In 1998, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts.[460]

In 2000, Peck was made a Doctor of Letters by the National University of Ireland. He was a founding patron of the University College Dublin School of Film, where he persuaded Martin Scorsese to become an honorary patron. Peck was also chairman of the American Cancer Society for a short time.

For his contribution to the motion picture industry, Gregory Peck has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6100 Hollywood Boulevard. In November 2005, the star was stolen, and has since been replaced.[461]

On April 28, 2011, a ceremony was held in Beverly Hills, California, celebrating the first day of issue of a U.S. postage stamp commemorating Peck. The stamp is the 17th commemorative stamp in the "Legends of Hollywood" series.[462][463]

On April 5, 2016, the 100th anniversary of Peck's birth, Turner Classic Movies, cable/satellite TV channel, honored the actor by showing several of his films.

Archives

Peck donated his personal collection of home movies and prints of his feature films to the Film Archive of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1999. The film material at the Academy Film Archive is complemented by printed materials in the Gregory Peck papers at the Academy's Margaret Herrick Library.[464]

Filmography

See also

References

- ^ Freedland, Michael. Gregory Peck: A Biography. New York: William Morrow and Company. 1980. ISBN 0-688-03619-8 p. 10

- ^ United States Census records for La Jolla, California 1910

- ^ United States Census records for St. Louis, Missouri – 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910

- ^ Ronald Bergan, "Gregory Peck obituary", The Guardian, June 13, 2003; see also Freedland, pp. 12–18

- ^ Freedland, pp. 16–19

- ^ Fishgall, Barry (2002). Gregory Peck: A Biography. New York City: Simon and Schuster. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-684-85290-X.

- ^ Thomas, Tony. Gregory Peck. Pyramid Publications, 1977, p. 16

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Monush, Barry (New York, 2003), "The Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors", Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, pg.589.

- ^ ""Gregory Peck comes home", ''Berkeley Magazine'', Summer 1996". Berkeley.edu. July 4, 2000.

- ^ Freedland, p. 35

- ^ a b "Gregory Peck Returns to Theatre Roots in Virginia Mountains", Playbill, June 29, 1998

- ^ Tad Mosel, Leading Lady: The World and Theatre of Katharine Cornell, Boston: Little, Brown & Co. 1978[page needed]

- ^ Welton Jones. "Gregory Peck," San Diego Union-Tribune, April 5, 1998

- ^ "Playhouse Highlights". La Jolla Playhouse. Archived from the original on November 15, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ "Circle of Concentration: Gregory Peck in an Interview with Gordon Gow" in Films and Filming, September 1974. https://www.theactorswork.com/2013/04/films-and-filming-gregory-peck.html

- ^ Thompson, David (London, 1994) "A Biographical Dictionary of Film", Martin Secker and Warburg Ltd., pg. 576.

- ^ https://www.tvguide.com/movies/days-of-glory/review/112333/

- ^ https://www.allmovie.com/movie/days-of-glory-v12658

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Maltin, Leonard. “Leonard Maltin’s Classic Movie Guide”, 2005.

- ^ https://www.allmovie.com/movie/days-of-glory-v12658