Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania | |

|---|---|

| Commonwealth of Pennsylvania | |

| Nickname(s): Keystone State;[1] Quaker State | |

| Motto(s): Virtue, Liberty and Independence | |

| Anthem: "Pennsylvania" | |

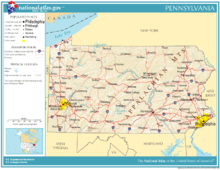

Map of the United States with Pennsylvania highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Province of Pennsylvania |

| Admitted to the Union | December 12, 1787 (2nd) |

| Capital | Harrisburg |

| Largest city | Philadelphia |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Delaware Valley |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Tom Wolf (D) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | John Fetterman (D) |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| • Upper house | State Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| U.S. senators | Bob Casey Jr. (D) Pat Toomey (R) |

| U.S. House delegation | 9 Democrats 9 Republicans (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 46,055 sq mi (119,283 km2) |

| • Land | 44,816.61 sq mi (116,074 km2) |

| • Water | 1,239 sq mi (3,208 km2) 2.7% |

| • Rank | 33rd |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 170 mi (273 km) |

| • Width | 283 mi (455 km) |

| Elevation | 1,100 ft (340 m) |

| Highest elevation | 3,213 ft (979 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • Total | 12,801,989 |

| • Rank | 5th |

| • Density | 284/sq mi (110/km2) |

| • Rank | 9th |

| • Median household income | $59,195[4] |

| • Income rank | 25th |

| Demonym | Pennsylvanian |

| Language | |

| • Official language | None |

| • Spoken language | English 90.15% Spanish 4.09% German (Including Pennsylvania German) 0.87% Chinese 0.47% Italian 0.43%[5] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | PA |

| ISO 3166 code | US-PA |

| Traditional abbreviation | Pa., Penn., Penna. |

| Latitude | 39°43′ to 42°16′ N |

| Longitude | 74°41′ to 80°31′ W |

| Website | www |

Pennsylvania (/ˌpɛnsəlˈveɪniə/ PEN-səl-VAY-nee-ə), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state located in the Northeastern, Great Lakes, Appalachian, and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The Appalachian Mountains run through its middle. The Commonwealth is bordered by Delaware to the southeast, Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, Lake Erie and the Canadian province of Ontario to the northwest, New York to the north, and New Jersey to the east.

Pennsylvania is the 33rd-largest state by area, and the 5th-most populous state according to the most recent official U.S. Census count in 2010. It is the 9th-most densely populated of the 50 states. Pennsylvania's two most populous cities are Philadelphia (1,580,863), and Pittsburgh (302,407). The state capital and its 10th-largest city is Harrisburg. Pennsylvania has 140 miles (225 km) of waterfront along Lake Erie and the Delaware River.[7]

The state is one of the 13 original founding states of the United States; it came into being in 1681 as a result of a royal land grant to William Penn, the son of the state's namesake. Part of Pennsylvania (along the Delaware River), together with the present State of Delaware, had earlier been organized as the Colony of New Sweden. It was the second state to ratify the United States Constitution, on December 12, 1787. Independence Hall, where the United States Declaration of Independence and United States Constitution were drafted, is located in the state's largest city of Philadelphia. During the American Civil War, the Battle of Gettysburg was fought in the south central region of the state. Valley Forge near Philadelphia was General Washington's headquarters during the bitter winter of 1777–78.

Geography

Pennsylvania is 170 miles (274 km) north to south and 283 miles (455 km) east to west.[8] Of a total 46,055 square miles (119,282 km2), 44,817 square miles (116,075 km2) are land, 490 square miles (1,269 km2) are inland waters, and 749 square miles (1,940 km2) are waters in Lake Erie.[9] It is the 33rd-largest state in the United States.[10] Pennsylvania has 51 miles (82 km)[11] of coastline along Lake Erie and 57 miles (92 km)[7] of shoreline along the Delaware Estuary. Of the original Thirteen Colonies, Pennsylvania is the only state that does not border the Atlantic Ocean.

The boundaries of the state are the Mason–Dixon line (39°43' N) to the south, the Twelve-Mile Circle on the Pennsylvania-Delaware border, the Delaware River to the east, 80°31' W to the west and the 42° N to the north, except for a short segment on the western end, where a triangle extends north to Lake Erie.

Cities include Philadelphia, Reading, Lebanon and Lancaster in the southeast, Pittsburgh in the southwest, the tri-cities of Allentown, Bethlehem, and Easton in the central east (known as the Lehigh Valley). The northeast includes the former anthracite coal mining cities of Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, Pittston, and Hazleton. Erie is located in the northwest. State College serves the central region while Williamsport serves the commonwealth's north-central region as does Chambersburg the south-central region, with York, Carlisle, and the state capital Harrisburg on the Susquehanna River in the east-central region of the Commonwealth and Altoona and Johnstown in the west-central region.

The state has five geographical regions, namely the Allegheny Plateau, Ridge and Valley, Atlantic Coastal Plain, Piedmont, and the Erie Plain.

Adjacent states and province

- Ontario (Province of Canada) (Northwest)

- New York (North and Northeast)

- New Jersey (East and Southeast)

- Delaware (Extreme Southeast)

- Maryland (South)

- West Virginia (Southwest)

- Ohio (West)

Climate

Pennsylvania's diverse topography also produces a variety of climates, though the entire state experiences cold winters and humid summers. Straddling two major zones, the majority of the state, except for the southeastern corner, has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa). The southern portion of the state has a humid subtropical climate. The largest city, Philadelphia, has some characteristics of the humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) that covers much of Delaware and Maryland to the south.

Summers are generally hot and humid. Moving toward the mountainous interior of the state, the winter climate becomes colder, the number of cloudy days increases, and snowfall amounts are greater. Western areas of the state, particularly locations near Lake Erie, can receive over 100 inches (250 cm) of snowfall annually, and the entire state receives plentiful precipitation throughout the year. The state may be subject to severe weather from spring through summer into autumn. Tornadoes occur annually in the state, sometimes in large numbers, such as 30 recorded tornadoes in 2011; generally speaking, these tornadoes do not cause significant damage.[12]

| Monthly Average High and Low Temperatures For Various Pennsylvania Cities (in °F) | ||||||||||||

| City | Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | May. | Jun. | Jul. | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scranton | 33/19 | 37/21 | 46/28 | 59/38 | 70/48 | 78/56 | 82/61 | 80/60 | 72/52 | 61/41 | 49/33 | 38/24 |

| Erie | 34/21 | 36/21 | 44/27 | 56/38 | 67/48 | 76/58 | 80/63 | 79/62 | 72/56 | 61/45 | 50/37 | 38/27 |

| Pittsburgh | 36/21 | 39/23 | 49/30 | 62/40 | 71/49 | 79/58 | 83/63 | 81/62 | 74/54 | 63/43 | 51/35 | 39/25 |

| Harrisburg | 37/23 | 41/25 | 50/33 | 62/42 | 72/52 | 81/62 | 85/66 | 83/64 | 76/56 | 64/45 | 53/35 | 41/27 |

| Philadelphia | 40/26 | 44/28 | 53/34 | 64/44 | 74/54 | 83/64 | 87/69 | 85/68 | 78/60 | 67/48 | 56/39 | 45/30 |

| Allentown | 36/20 | 40/22 | 49/29 | 61/39 | 72/48 | 80/58 | 84/63 | 82/61 | 75/53 | 64/41 | 52/33 | 40/24 |

| Sources:[13][14][15][16][17] | ||||||||||||

History

Historically, as of 1600, the tribes living in Pennsylvania were the Algonquian Lenape (also Delaware), the Iroquoian Susquehannock & Petun (also Tionontati, Kentatentonga, Tobacco, Wenro)[18] and the presumably Siouan Monongahela Culture, who may have been the same as a little known tribe called the Calicua, or Cali.[19] Other tribes who entered the region during the colonial era were the Trockwae,[20] Tutelo, Saponi, Shawnee, Nanticoke, Conoy Piscataway, Iroquois Confederacy—possibly among others.[21][22][23][24]

Other tribes, like the Erie, may have once held some land in Pennsylvania, but no longer did so by the year 1600.[25]

17th century

Both the Dutch and the English claimed both sides of the Delaware River as part of their colonial lands in America.[26][27][28] The Dutch were the first to take possession.[28]

By June 3, 1631, the Dutch had begun settling the Delmarva Peninsula by establishing the Zwaanendael Colony on the site of present-day Lewes, Delaware.[29] In 1638, Sweden established the New Sweden Colony, in the region of Fort Christina, on the site of present-day Wilmington, Delaware. New Sweden claimed and, for the most part, controlled the lower Delaware River region (parts of present-day Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania) but settled few colonists there.[30][31]

On March 12, 1664, King Charles II of England gave James, Duke of York a grant that incorporated all lands included in the original Virginia Company of Plymouth Grant plus other lands. This grant was in conflict with the Dutch claim for New Netherland, which included parts of today's Pennsylvania.[32]

On June 24, 1664, the Duke of York sold the portion of his large grant that included present-day New Jersey to John Berkeley and George Carteret for a proprietary colony. The land was not yet in British possession, but the sale boxed in the portion of New Netherland on the West side of the Delaware River. The British conquest of New Netherland began on August 29, 1664, when New Amsterdam was coerced to surrender while facing cannons on British ships in New York Harbor.[33][34] This conquest continued, and was completed in October 1664, when the British captured Fort Casimir in what today is New Castle, Delaware.

The Peace of Breda between England, France and the Netherlands confirmed the English conquest on July 21, 1667,[35][36] although there were temporary reversions.

On September 12, 1672, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch re-conquered New York Colony/New Amsterdam, establishing three County Courts, which went on to become original Counties in present-day Delaware and Pennsylvania. The one that later transferred to Pennsylvania was Upland.[37] This was partially reversed on February 9, 1674, when the Treaty of Westminster ended the Third Anglo-Dutch War, and reverted all political situations to the status quo ante bellum. The British retained the Dutch Counties with their Dutch names.[38] By June 11, 1674, New York reasserted control over the outlying colonies, including Upland, but the names started to be changed to British names by November 11, 1674.[39] Upland was partitioned on November 12, 1674, producing the general outline of the current border between Pennsylvania and Delaware.[40]

On February 28, 1681, Charles II granted a land charter[41] to William Penn to repay a debt of £16,000[42] (around £2,100,000 in 2008, adjusting for retail inflation)[43] owed to William's father, Admiral William Penn. This was one of the largest land grants to an individual in history.[44] The King named it Pennsylvania (literally "Penn's Woods") in honor of the Admiral. Penn, the son, who wanted it to be called New Wales, and then Sylvania (from the Latin silva: "forest, woods"), was embarrassed at the change, fearing that people would think he had named it after himself, but King Charles would not rename the grant.[45] Penn established a government with two innovations that were much copied in the New World: the county commission and freedom of religious conviction.[44]

What had been Upland on what became the Pennsylvania side of the Pennsylvania-Delaware Border was renamed as Chester County when Pennsylvania instituted their colonial governments on March 4, 1681.[46][47] The Quaker leader William Penn had signed a peace treaty with Tammany, leader of the Delaware tribe, beginning a long period of friendly relations between the Quakers and the Indians.[48] Additional treaties between Quakers and other tribes followed. The treaty of William Penn was never violated.[49]

18th century

Between 1730 and when it was shut down by Parliament with the Currency Act of 1764, the Pennsylvania Colony made its own paper money to account for the shortage of actual gold and silver. The paper money was called Colonial Scrip. The Colony issued "bills of credit", which were as good as gold or silver coins because of their legal tender status. Since they were issued by the government and not a banking institution, it was an interest-free proposition, largely defraying the expense of the government and therefore taxation of the people. It also promoted general employment and prosperity, since the Government used discretion and did not issue too much to inflate the currency. Benjamin Franklin had a hand in creating this currency, of which he said its utility was never to be disputed, and it also met with the "cautious approval" of Adam Smith.[50]

James Smith wrote that in 1763, "the Indians again commenced hostilities, and were busily engaged in killing and scalping the frontier inhabitants in various parts of Pennsylvania." Further, "This state was then a Quaker government, and at the first of this war the frontiers received no assistance from the state."[51] The ensuing hostilities became known as Pontiac's War.

After the Stamp Act Congress of 1765, Delegate John Dickinson of Philadelphia wrote the Declaration of Rights and Grievances. The Congress was the first meeting of the Thirteen Colonies, called at the request of the Massachusetts Assembly, but only nine colonies sent delegates.[52] Dickinson then wrote Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, To the Inhabitants of the British Colonies, which were published in the Pennsylvania Chronicle between December 2, 1767, and February 15, 1768.[53]

When the Founding Fathers of the United States convened in Philadelphia in 1774, 12 colonies sent representatives to the First Continental Congress.[54] The Second Continental Congress, which also met in Philadelphia (in May 1775), drew up and signed the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia,[55] but when that city was captured by the British, the Continental Congress escaped westward, meeting at the Lancaster courthouse on Saturday, September 27, 1777, and then to York. There they and its primary author, John Dickinson, drew up the Articles of Confederation that formed 13 independent States[56] into a new union. Later, the Constitution was written, and Philadelphia was once again chosen to be cradle to the new American Union.[57] The Constitution was drafted and signed at the Pennsylvania State House, now known as Independence Hall, and the same building where the Declaration of Independence was signed.[58]

Pennsylvania became the first large state, and the second state to ratify the U.S. Constitution on December 12, 1787,[59] five days after Delaware became the first. At the time it was the most ethnically and religiously diverse of the thirteen States. Because One-third of Pennsylvania's population spoke German, the Constitution was presented in German to include those citizens in the discussion. Reverend Frederick Muhlenberg acted as the chairman of the state's ratifying convention.[60]

Dickinson College of Carlisle was the first college founded after the States united. Established in 1773, the college was ratified five days after the Treaty of Paris on September 9, 1783. The school was founded by Benjamin Rush and named after John Dickinson.

For half a century, the Commonwealth's General Assembly (legislature) met at various places in the general Philadelphia area before starting to meet regularly in Independence Hall in Philadelphia for 63 years.[61] But it needed a more central location, as for example the Paxton Boys massacres of 1763 had made the legislature aware. So, in 1799 the General Assembly moved to the Lancaster Courthouse,[61] and finally in 1812 to Harrisburg.[61]

19th century

The General Assembly met in the old Dauphin County Court House until December 1821,[61] when the Federal-style "Hills Capitol" (named for its builder, Stephen Hills, a Lancaster architect) was constructed on a hilltop land grant of four acres set aside for a seat of state government by the prescient, entrepreneurial son and namesake of John Harris, Sr., a Yorkshire native who had founded a trading post in 1705 and ferry (1733) on the east shore of the Susquehanna River.[62] The Hills Capitol burned down on February 2, 1897, during a heavy snowstorm, presumably because of a faulty flue.[61]

The General Assembly met at Grace Methodist Church on State Street (still standing) until a new capitol could be built. Following an architectural selection contest that many alleged had been "rigged", Chicago architect Henry Ives Cobb was charged with designing and building a replacement building; however, the legislature had little money to allocate to the project, and a roughly finished, somewhat industrial building (the Cobb Capitol) was completed. The General Assembly refused to occupy the building. Political and popular indignation in 1901 prompted a second contest that was restricted to Pennsylvania architects, and Joseph Miller Huston of Philadelphia was chosen to design the present Pennsylvania State Capitol that incorporated Cobb's building into magnificent public work finished and dedicated in 1907.[61]

The new state Capitol drew rave reviews.[61] Its dome was inspired by the domes of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome and the United States Capitol.[61] President Theodore Roosevelt called it "the most beautiful state Capital in the nation" and said, "It's the handsomest building I ever saw" at the dedication. In 1989, The New York Times praised it as "grand, even awesome at moments, but it is also a working building, accessible to citizens ... a building that connects with the reality of daily life".[61]

James Buchanan, of Franklin County, the only bachelor president of the United States (1857–1861),[63] was the only one to be born in Pennsylvania. The Battle of Gettysburg—the major turning point of the Civil War—took place near Gettysburg.[64] An estimated 350,000 Pennsylvanians served in the Union Army forces including 8,600 African American military volunteers.

Pennsylvania was also the home of the first commercially drilled oil well. In 1859, near Titusville, Pennsylvania, Edwin Drake successfully drilled the well, which led to the first major oil boom in United States history.

20th century

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2016) |

At the beginning of the 20th century, Pennsylvania's economy centered on steel production, logging, coal mining, textile production and other forms of industrial manufacturing. A surge in immigration to the U.S. during the late 19th and early 20th centuries provided a steady flow of cheap labor for these industries, which often employed children and people who could not speak English.

In 1923, President Calvin Coolidge established the Allegheny National Forest under the authority of the Weeks Act of 1911.[65] The forest is located in the northwest part of the state in Elk, Forest, McKean, and Warren Counties for the purposes of timber production and watershed protection in the Allegheny River basin. The Allegheny is the state's only national forest.[66]

The Three Mile Island accident was the most significant nuclear accident in U.S. commercial nuclear power plant history.[67][68]

21st century

Within the first half of 2003, the annual Tekko commences in Pittsburgh.[69]

In October 2018, the Tree of Life – Or L'Simcha Congregation experienced the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting.[70]

Demographics

As of 2019, Pennsylvania has an estimated population of 12,801,989, which is an decrease of 5,071 from the previous year and an increase of 99,610 since the year 2010. Net migration to other states resulted in a decrease of 27,718, and immigration from other countries resulted in an increase of 127,007. Net migration to the Commonwealth was 98,289. Migration of native Pennsylvanians resulted in a decrease of 100,000 people. From 2008 to 2012, 5.8% of the population was foreign-born.[71]

Place of origin

Of the people residing in Pennsylvania, 74.5% were born in Pennsylvania, 18.4% were born in a different U.S. state, 1.5% were born in Puerto Rico, U.S. Island areas, or born abroad to American parent(s), and 5.6% were foreign born.[72] Foreign-born Pennsylvanians are largely from Asia (36.0%), Europe (35.9%), and Latin America (30.6%), with the remainder from Africa (5%), North America (3.1%), and Oceania (0.4%).

The largest ancestry groups are listed below, expressed as a percentage of total people who responded with a particular ancestry for the 2010 census:[73][74]

- German 28.5%

- Irish 18.2%

- Italian 12.8%

- African American 9.6%

- English 8.5%

- Polish 7.2%

- French Canadian 4.2%

Racial breakdown

| Racial composition | 1990[75] | 2000[76] | 2010[77] |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 88.5% | 85.4% | 81.9% |

| Black | 9.2% | 10.0% | 10.9% |

| Asian | 1.2% | 1.8% | 2.8% |

| Native | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

– | – | – |

| Other race | 1.0% | 1.5% | 2.4% |

| Two or more races | – | 1.2% | 1.9% |

As of 2011, 32.1% of Pennsylvania's population younger than age 1 were minorities.[78]

Pennsylvania's Hispanic population grew by 82.6% between 2000 and 2010, making it one of the largest increases in a state's Hispanic population. The significant growth of the Hispanic population is due to immigration to the state mainly from Puerto Rico, which is a US territory, but to a lesser extent from countries such as the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and various Central and South American nations, as well as from the wave of Hispanics leaving New York and New Jersey for safer and more affordable living. The Asian population swelled by almost 60%, which was fueled by Indian, Vietnamese, and Chinese immigration, as well the many Asian transplants moving to Philadelphia from New York. The rapid growth of this community has given Pennsylvania one of the largest Asian populations in the nation by numerical values. The Black and African American population grew by 13%, which was the largest increase in that population amongst the state's peers (New York, New Jersey, Ohio, Illinois, and Michigan). Twelve other states saw decreases in their White populations.[79] The state of Pennsylvania has a high in-migration of black and Hispanic people from other nearby states, with eastern and south-central portions of the state seeing the bulk of the increases.[80][81]

The majority of Hispanics in Pennsylvania are of Puerto Rican descent, having one of the largest and fastest-growing Puerto Rican populations in the country.[82][83] Most of the remaining Hispanic population is made up of Mexicans and Dominicans. Most Hispanics are concentrated in Philadelphia, Lehigh Valley and South Central Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania's reported population of Hispanics, especially among the Black race, has markedly increased in recent years.[84] The Hispanic population is greatest in Bethlehem, Allentown, Reading, Lancaster, York, and around Philadelphia. It is not clear how much of this change reflects a changing population and how much reflects increased willingness to self-identify minority status. As of 2010, it is estimated that about 85% of all Hispanics in Pennsylvania live within a 150-mile (240 km) radius of Philadelphia, with about 20% living within the city itself.

Of the black population, the vast majority in the state are African American, being descendants of African slaves brought to the US south during the colonial era. There are also a growing number of blacks of West Indian, recent African, and Hispanic origins.[85] Most blacks live in the Philadelphia area, Pittsburgh, and South Central Pennsylvania. Whites make up the majority of Pennsylvania; they are mostly descended from German, Irish, Scottish, Welsh, Italian, and English immigrants. Rural portions of South Central Pennsylvania are famous nationwide for their notable Amish communities. The Wyoming Valley, consisting of Scranton and Wilkes-Barre, has the highest percentage of white residents of any metropolitan area in the U.S., with 96.2% of its population claiming to be white with no Hispanic background.

The center of population of Pennsylvania is located in Perry County, in the borough of Duncannon.[86]

Age and poverty

The state had the fourth-highest proportion of elderly (65+) citizens in 2010–15.4%, as compared to 13.0% nationwide.[87] According to U.S. Census Bureau estimates, the state's poverty rate was 12.5% in 2017, compared to 13.4% for the United States as a whole.[88]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 434,373 | — | |

| 1800 | 602,365 | 38.7% | |

| 1810 | 810,091 | 34.5% | |

| 1820 | 1,049,458 | 29.5% | |

| 1830 | 1,348,233 | 28.5% | |

| 1840 | 1,724,033 | 27.9% | |

| 1850 | 2,311,786 | 34.1% | |

| 1860 | 2,906,215 | 25.7% | |

| 1870 | 3,521,951 | 21.2% | |

| 1880 | 4,282,891 | 21.6% | |

| 1890 | 5,258,113 | 22.8% | |

| 1900 | 6,302,115 | 19.9% | |

| 1910 | 7,665,111 | 21.6% | |

| 1920 | 8,720,017 | 13.8% | |

| 1930 | 9,631,350 | 10.5% | |

| 1940 | 9,900,180 | 2.8% | |

| 1950 | 10,498,012 | 6.0% | |

| 1960 | 11,319,366 | 7.8% | |

| 1970 | 11,793,909 | 4.2% | |

| 1980 | 11,863,895 | 0.6% | |

| 1990 | 11,881,643 | 0.1% | |

| 2000 | 12,281,054 | 3.4% | |

| 2010 | 12,702,379 | 3.4% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 12,801,989 | 0.8% | |

| Source: 1910–2010[89] 2019 Estimate[90] | |||

| State | % of population |

|---|---|

| Florida | 17.3 |

| West Virginia | 16.0 |

| Maine | 15.9 |

| Pennsylvania | 15.4 |

| Iowa | 14.9 |

| Montana | 14.8 |

| Vermont | 14.6 |

| North Dakota | 14.5 |

| Rhode Island | 14.4 |

| Arkansas | 14.4 |

Birth data

Note: Births in table don't add up, because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

| Race | 2013[92] | 2014[93] | 2015[94] | 2016[95] | 2017[96] | 2018[97] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 109,007 (77.3%) | 110,809 (77.9%) | 109,595 (77.7%) | ... | ... | ... |

| > Non-Hispanic White | 98,751 (70.0%) | 99,306 (69.8%) | 97,845 (69.4%) | 94,520 (67.8%) | 92,297 (67.0%) | 90,862 (67.0%) |

| Black | 24,770 (17.6%) | 24,024 (16.9%) | 24,100 (17.1%) | 18,338 (13.1%) | 18,400 (13.4%) | 17,779 (13.1%) |

| Asian | 6,721 (4.7%) | 7,067 (5.0%) | 6,961 (4.9%) | 6,466 (4.6%) | 6,401 (4.6%) | 6,207 (4.6%) |

| American Indian | 423 (0.3%) | 368 (0.3%) | 390 (0.3%) | 86 (0.1%) | 135 (0.1%) | 128 (0.1%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 14,163 (10.1%) | 14,496 (10.2%) | 14,950 (10.6%) | 15,348 (11.0%) | 15,840 (11.5%) | 15,826 (11.7%) |

| Total Pennsylvania | 140,921 (100%) | 142,268 (100%) | 141,047 (100%) | 139,409 (100%) | 137,745 (100%) | 135,673 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin have not been collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

Languages

| Language | Percentage of population (as of 2010)[98] |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 4.09% |

| German (including Pennsylvania German) | 0.87% |

| Chinese (including Mandarin) | 0.47% |

| Italian | 0.43% |

| French | 0.34% |

| Russian and Vietnamese (tied) | 0.29% |

| Korean | 0.25% |

| Polish | 0.21% |

| Arabic | 0.20% |

| Hindi | 0.17% |

As of 2010, 90.15% (10,710,239) of Pennsylvania residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 4.09% (486,058) spoke Spanish, 0.87% (103,502) German (which includes Pennsylvania Dutch) and by 0.47% (56,052) Chinese (which includes Mandarin) of the population over the age of five. In total, 9.85% (1,170,628) of Pennsylvania's population age 5 and older spoke a mother language other than English.[98]

Pennsylvania German language

Pennsylvania German is often—even though misleadingly—called "Pennsylvania Dutch". The term "Dutch" used to mean "German"[99] (including the Netherlands), before the Latin name for them replaced it (but stuck with the Netherlands). When referring to the language spoken by the Pennsylvania Dutch people (Pennsylvania German) it means "German" or "Teutonic" rather than "Netherlander". Germans, in their own language, call themselves "Deutsch", (Pennsylvania German: "Deitsch"). The Pennsylvania German language is a descendant of German, in the West Central German dialect family. It is closest to Palatine German. Pennsylvania German is still very vigorous as a first language among Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonites (principally in the Lancaster County area), whereas it is almost extinct as an everyday language outside the plain communities, though a few words have passed into English usage.

Religion

Of all the colonies, only Rhode Island had religious freedom as secure as in Pennsylvania.[101] Voltaire, writing of William Penn in 1733, observed: "The new sovereign also enacted several wise and wholesome laws for his colony, which have remained invariably the same to this day. The chief is, to ill-treat no person on account of religion, and to consider as brethren all those who believe in one God."[102] One result of this uncommon freedom was a wide religious diversity, which continues to the present.

Pennsylvania's population in 2010 was 12,702,379. Of these, 6,838,440 (53.8%) were estimated to belong to some sort of organized religion. According to the Association of religion data archives (ARDA) at Pennsylvania State University, the largest religions in Pennsylvania by adherents are the Roman Catholic Church with 3,503,028 adherents, the United Methodist Church with 591,734 members, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America with 501,974 members.

The fourth-largest single denomination is the Presbyterian Church (USA)[clarification needed] with 250,000 members and 1,011 congregations. Pennsylvania, especially its western part and the Pittsburgh area, has one of the highest percentages of Presbyterians in the nation. The Presbyterian Church in America is also significant, with 112 congregations and 23,000 adherents; the EPC has around 50 congregations, as well as the ECO. The fourth-largest Protestant denomination, the United Church of Christ, has 180,000 members and 627 congregations. American Baptist Churches USA (Northern Baptist Convention) is based in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania was the center state of the German Reformed denomination from the 1700s.[103] Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, is one of the headquarters of the Moravian Church in America. Pennsylvania also has a very large Amish population, second only to Ohio among the states.[104] In the year 2000 there was a total Amish population of 47,860 in Pennsylvania and a further 146,416 Mennonites and 91,200 Brethren. The total Anabapist population including Bruderhof[105] was 232,631, about two percent of the population.[106] While Pennsylvania owes its existence to Quakers, and much of the historic character of the Commonwealth is ideologically rooted in the teachings of the Religious Society of Friends (as they are officially known), practicing Quakers are a small minority of about 10,000 adherents in 2010.[107]

As of 2014[update], the religious affiliations of the people of Pennsylvania are:[100]

- Christian 73%

- Protestant 47%

- Roman Catholic 24%

- Jehovah's Witnesses 1%

- Orthodox Christian <1%

- Non-religious/Unaffiliated 21%

- Judaism 0.8%

- Islam 0.6%

- Hinduism 1%

- Other 2%

- Don't know/Refused to say 1%

According to a 2016 Gallup poll, 38% of Pennsylvanians are very religious, 29% are moderately religious, and 34% are non-religious.[108]

Economy

Pennsylvania's 2018 total gross state product (GSP) of $803 billion ranks the state 6th in the nation.[109] If Pennsylvania were an independent country, its economy would rank as the 19th-largest in the world.[110] On a per-capita basis, Pennsylvania's 2016 per-capita GSP of $50,665 (in chained 2009 dollars) ranks 22nd among the fifty states.[109]

Total employment 2016

- 5,354,964

Total employer establishments

- 301,484[111]

Philadelphia in the southeast corner, Pittsburgh in the southwest corner, Erie in the northwest corner, Scranton-Wilkes-Barre in the northeast corner, and Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton in the east central region are urban manufacturing centers. Much of the Commonwealth is rural; this dichotomy affects state politics as well as the state economy.[112] Philadelphia is home to six Fortune 500 companies,[113] with more located in suburbs like King of Prussia; it is a leader in the financial[114] and insurance industry.

Pittsburgh is home to eight Fortune 500 companies, including U.S. Steel, PPG Industries, and H.J. Heinz.[113] In all, Pennsylvania is home to fifty Fortune 500 companies.[113] Hershey is home to The Hershey Company, one of the largest chocolate manufacturers in the world. Erie is also home to GE Transportation, which is the largest producer of train locomotives in the United States.

As in the US as a whole and in most states, the largest private employer in the Commonwealth is Walmart, followed by the University of Pennsylvania.[115][116] Pennsylvania is also home to the oldest investor-owned utility company in the US, The York Water Company.

As of November 2018, the state's unemployment rate is 4.2%.[117]

| Year | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP in mil. US$[118] | 506.505 | 525.979 | 559.876 | 579.432 | 573.964 | 596.662 | 615.411 | 637.896 | 659.792 | 684.781 | 708.402 | 724.936 |

| GDP per capita in real 2009 US$[118] | 45,035 | 45,021 | 46,330 | 46,862 | 45,312 | 46,387 | 46,872 | 47,540 | 48,278 | 49,155 | 50,418 | 50,997 |

| Real growth rate in %[119] | 1.3% | 0.5% | 3.3% | 1.5% | −2.9% | 2.7% | 1.3% | 1.6% | 1.6% | 2.0% | 2.6% | 0.9% |

| unemployment rate (in July)[120] | 4.9% | 4.7% | 4.4% | 5.2% | 8.2% | 8.3% | 8.0% | 7.9% | 7.3% | 5.8% | 5.3% | 5.5% |

Banking

The first nationally chartered bank in the United States, the Bank of North America, was founded in 1781 in Philadelphia. After a series of mergers, the Bank of North America is part of Wells Fargo, which uses national charter 1.

Pennsylvania is also the home to the first nationally chartered bank under the 1863 National Banking Act. That year, the Pittsburgh Savings & Trust Company received a national charter and renamed itself the First National Bank of Pittsburgh as part of the National Banking Act. That bank is still in existence today as PNC Financial Services and remains based in Pittsburgh. PNC is the state's largest bank and the sixth-largest in the United States.

Agriculture

Pennsylvania ranks 19th overall in agricultural production.[121]

- The 1st is mushroom production,

- The 2nd is apples,

- The 3rd is Christmas trees and layer chickens,

- The 4th is nursery and sod, milk, corn for silage, grapes grown (including juice grapes), and horses production.

It also ranks 8th in the nation in Winemaking.[122]

The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture worked with private companies to establish "PA Preferred" as a way to brand agricultural products grown or made in the state to support and promote Pennsylvania products and locally grown food.[123]

The financial impact of agriculture in Pennsylvania[124] includes employment of more than 66,800 people employed by the food manufacturing industry; and over $1.7 billion in food product export (in 2011).

Gambling

Casino gambling was legalized in Pennsylvania in 2004. Currently, there are nine casinos across the state with three under construction or in planning. Only horse racing, slot machines and electronic table games were legal in Pennsylvania, although a bill to legalize table games was being negotiated in the fall of 2009.[125] Table games such as poker, roulette, blackjack, and craps were finally approved by the state legislature in January 2010, being signed into law by the Governor on January 7.

Former Governor Ed Rendell had considered legalizing video poker machines in bars and private clubs in 2009 since an estimated 17,000 operate illegally across the state.[126] Under this plan, any establishment with a liquor license would be allowed up to five machines. All machines would be connected to the state's computer system, like commercial casinos. The state would impose a 50% tax on net gambling revenues, after winning players have been paid, with the remaining 50% going to the establishment owners.

Film

The Pennsylvania Film Production Tax Credit began in 2004 and stimulated the development of a film industry in the state.[127]

Governance

Pennsylvania has had five constitutions during its statehood:[128] 1776, 1790, 1838, 1874, and 1968. Before that the province of Pennsylvania was governed for a century by a Frame of Government, of which there were four versions: 1682, 1683, 1696, and 1701.[128] The capital of Pennsylvania is Harrisburg. The legislature meets in the State Capitol there.

Executive

The current Governor is Tom Wolf. The other elected officials composing the executive branch are the Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman, Attorney General Joshua Shapiro, Auditor General Eugene DePasquale, and Pennsylvania Treasurer Joe Torsella. The Governor and Lieutenant Governor run as a ticket in the general election and are up for re-election every four years during the midterm elections. The elections for Attorney General, Auditor General, and Treasurer are held every four years coinciding with a Presidential election.[129]

Legislative

Pennsylvania has a bicameral legislature set up by Commonwealth's constitution in 1790. The original Frame of Government of William Penn had a unicameral legislature.[130] The General Assembly includes 50 Senators and 203 Representatives. Joe Scarnati is currently President Pro Tempore of the State Senate, Jake Corman the Majority Leader, and Jay Costa the Minority Leader.[131] Mike Turzai is Speaker of the House of Representatives, with Bryan Cutler as Majority Leader and Frank Dermody as Minority Leader.[132] As of the 2018 elections, the Republicans hold the majority in the State House and Senate.

Judiciary

Pennsylvania is divided into 60 judicial districts,[133] most of which (except Philadelphia) have magisterial district judges (formerly called district justices and justices of the peace), who preside mainly over preliminary hearings in felony and misdemeanor offenses, all minor (summary) criminal offenses, and small civil claims.[133] Most criminal and civil cases originate in the Courts of Common Pleas, which also serve as appellate courts to the district judges and for local agency decisions.[133] The Superior Court hears all appeals from the Courts of Common Pleas not expressly designated to the Commonwealth Court or Supreme Court. It also has original jurisdiction to review warrants for wiretap surveillance.[133] The Commonwealth Court is limited to appeals from final orders of certain state agencies and certain designated cases from the Courts of Common Pleas.[133] The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania is the final appellate court. All judges in Pennsylvania are elected; the chief justice is determined by seniority.[133]

State law enforcement

The Pennsylvania State Police is the chief law enforcement agency in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Municipalities

Pennsylvania is divided into 67 counties.[134] Counties are further subdivided into municipalities that are either incorporated as cities, boroughs, or townships.[135] One county, Philadelphia County, is coterminous with the city of Philadelphia after it was consolidated in 1854. The most populous county in Pennsylvania is Philadelphia, while the least populous is Cameron (5,085).[80]

There are a total of 56 cities in Pennsylvania, which are classified, by population, as either first-, second-, or third-class cities.[134][136] Philadelphia, Pennsylvania's largest city, has a population of 1,526,006 and is the state's only first-class city.[135] Pittsburgh (305,704) and Scranton (76,089) are second-class and second-class 'A' cities, respectively.[135]

The rest of the cities, like the third and fourth-largest—Allentown (120,443) and Erie (98,593)—to the smallest—Parker with a population of only 820—are third-class cities.[137] First- and second-class cities are governed by a "strong mayor" form of mayor–council government, whereas third-class cities are governed by either a "weak mayor" form of government or a council–manager government.[135]

Boroughs are generally smaller than cities, with most Pennsylvania cities having been incorporated as a borough before being incorporated as a city.[135] There are 958 boroughs in Pennsylvania, all of which are governed by the "weak mayor" form of mayor-council government.[134][135] The largest borough in Pennsylvania is State College (41,992) and the smallest is Centralia.

Townships are the third type of municipality in Pennsylvania and are classified as either first-class or second-class townships. There are 1,454 second-class townships and 93 first-class townships.[138] Second-class townships can become first-class townships if they have a population density greater than 300 inhabitants per square mile (120/km2) and a referendum is passed supporting the change.[138] Pennsylvania's largest township is Upper Darby Township (82,629), and the smallest is East Keating Township.

There is one exception to the types of municipalities in Pennsylvania: Bloomsburg was incorporated as a town in 1870 and is, officially, the only town in the state.[139] In 1975, McCandless Township adopted a home-rule charter under the name of "Town of McCandless", but is, legally, still a first-class township.[140]

The total of 56 cities, 958 boroughs, 93 first-class townships, 1,454 second-class townships, and one town (Bloomsburg) is 2,562 municipalities.

Politics

For most of the second half of the 20th century and into the 21st century, Pennsylvania has been a powerful swing state. It supported the losing candidate in a presidential election only twice from 1932 to 1988, (Herbert Hoover in 1932 and Hubert Humphrey in 1968). Since 1992, Pennsylvania has been trending Democratic in Presidential elections, voting for Bill Clinton twice by large margins, and slightly closer in 2000 for Al Gore. In the 2004 Presidential Election, Senator John F. Kerry beat President George W. Bush in Pennsylvania 2,938,095 (50.92%) to 2,793,847 (48.42%). In the 2008 Presidential Election, Democrat Barack Obama defeated Republican John McCain in Pennsylvania, 3,184,778 (54%) to 2,584,088 (44%). Most recently, in the 2016 Presidential Election, Donald Trump became the first Republican candidate to win the state since 1988, winning the state 48.6% to 47.8%.[142] The state holds 20 electoral votes.[143]

In recent national elections since 1992, Pennsylvania had leaned for the Democratic Party. The state voted for the Democratic ticket for president in every election between 1992 and 2012. During the 2008 election campaign, a recruitment drive saw registered Democrats outnumber registered Republicans by 1.2 million. However, Pennsylvania has a history of electing Republican senators. From 2009 to 2011, the state was represented by two Democratic senators for the first time since 1947. In 2010, Republicans recaptured a U.S. Senate seat as well as a majority of the state's congressional seats, control of both chambers of the state legislature and the governor's mansion. Democrats won back the governor's mansion four years later in the 2014 election. It was the first time since a governor became eligible to succeed himself that an incumbent governor had been defeated for reelection.

#3333FF #E81B23 white| Party | Number of Voters | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | 4,059,864 (-51,461) | 47.59% | |

| Republican | 3,245,979 (-24,903) | 38.05% | |

| Minor parties / Unaffiliated |

1,225,140 (-2,533) | 14.36% | |

| Total | 8,530,983 (-78,897) | 100% | |

| *Lost between November 6, 2018, and November 5, 2019. | |||

Historically, Democratic strength was concentrated in Philadelphia in the southeast, the Pittsburgh and Johnstown areas in the southwest, and Scranton/Wilkes-Barre in the northeast. Republican strength was concentrated in the Philadelphia suburbs, as well as the more rural areas in the central, northeastern, and western portions. The latter counties have long been among the most conservative areas in the nation. Since 1992, however, the Philadelphia suburbs have swung Democratic; the brand of Republicanism there was traditionally a moderate one. The Pittsburgh suburbs, historically a Democratic stronghold, have swung more Republican since the turn of the millennium.

Democratic political consultant James Carville once pejoratively described Pennsylvania as "Philadelphia in the east, Pittsburgh in the west and Alabama in the middle". Political analysts and editorials refer to central Pennsylvania as the "T" in statewide elections. Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Scranton/Wilkes-Barre generally vote for Democratic candidates, while the majority of the counties in the central part of the state vote Republican. As a result, maps showing the results of statewide elections invariably form a "T" shape.

Taxation

Pennsylvania has the 10th-highest tax burden in the United States.[145] Residents pay a total of $83.7 billion in state and local taxes with a per capita average of $6,640 annually. Residents share 76% of the total tax burden. Many state politicians have tried to increase the share of taxes paid by out of state sources. Suggested revenue sources include taxing natural gas drilling as Pennsylvania is the only state without such a tax on gas drilling.[146] Additional revenue prospects include trying to place tolls on interstate highways; specifically Interstate 80, which is used heavily by out of state commuters with high maintenance costs.[147]

Sales taxes provide 39% of the Commonwealth's revenue; personal income taxes 34%; motor vehicle taxes about 12%, and taxes on cigarettes and alcoholic beverages 5%.[148] The personal income tax is a flat 3.07%. An individual's taxable income is based on the following eight types of income: compensation (salary); interest; dividends; net profits from the operation of a business, profession or farm; net gains or income from the dispositions of property; net gains or income from rents, royalties, patents and copyrights; income derived through estates or trusts; and gambling and lottery winnings (other than Pennsylvania Lottery winnings).[149]

Counties, municipalities, and school districts levy taxes on real estate. In addition, some local bodies assess a wage tax on personal income. Generally, the total wage tax rate is capped at 1% of income but some municipalities with home rule charters may charge more than 1%. Thirty-two of the Commonwealth's sixty-seven counties levy a personal property tax on stocks, bonds, and similar holdings.

With the exception of the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, municipalities and school districts are allowed to enact a local earned income tax within the purview of Act 32. Residents of these municipalities and school districts are required to file a local income tax return in addition to federal and state returns. This local return is filed with the local income tax collector, a private collection agency (e.g. Berkheimer, Keystone Collections, and Jordan Tax Service) appointed by a particular county to collect the local earned income and local services tax (the latter a flat fee deducted from salaried employees working within a particular municipality or school district).[150][151][152][153]

The City of Philadelphia has its own local income taxation system. Philadelphia-based employers are required to withhold the Philadelphia wage tax from the salaries of their employees. Residents of Philadelphia working for an employer are not required to file a local return as long as their Philadelphia wage tax is fully withheld by their employer. If their employer does not withhold the Philadelphia wage tax, residents are required to register with the Revenue Department and file an Earnings Tax return. Residents of Philadelphia with self-employment income are required to file a Net Profits Tax (NPT) return, while those with business income from Philadelphia sources are required to obtain a Commercial Activity License (CAL) and pay the Business Income and Receipts Tax (BIRT) and the NPT. Residents with unearned income (except for interest from checking and savings accounts) are required to file and pay the School Income-tax (SIT).[154]

The complexity of Pennsylvania's local tax filing system has been criticized by experts, who note that the outsourcing of collections to private entities is akin to tax farming and that many new residents are caught off guard and end up facing "failure to file" penalties even if they did not owe any tax. Attempts to transfer local income tax collections to the state level (i.e. by having a separate local section on the state income tax return, currently the method used to collect local income taxes in New York, Maryland, Indiana, and Iowa) have been unsuccessful.[155]

Federal representation

Pennsylvania's two U.S. Senators are Bob Casey, Jr. and Pat Toomey.

Pennsylvania has 18 seats in the United States House of Representatives, as of the 2010 Census.[156]

Health

Pennsylvania has a mixed health record, and is ranked as the 29th-overall-healthiest state according to the 2013 United Health Foundation's Health Rankings.[157]

Education

Pennsylvania has 500 public school districts, thousands of private schools, publicly funded colleges and universities, and over 100 private institutions of higher education.

Primary and secondary education

In general, under state law, school attendance in Pennsylvania is mandatory for a child from the age of 8 until the age of 17, or until graduation from an accredited high school, whichever is earlier.[158] As of 2005, 83.8% of Pennsylvania residents age 18 to 24 have completed high school. Among residents age 25 and over, 86.7% have graduated from high school.

The following are the four-year graduation rates for students completing high school in 2016:[159]

| Cohort | All Students | Male | Female | White | Hispanic | Black | Asian | Special Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % graduating | 86.09 | 84.14 | 88.13 | 90.48 | 72.83 | 73.22 | 91.21 | 74.06 |

Additionally, 27.5% have gone on to obtain a bachelor's degree or higher.[160] State students consistently do well in standardized testing. In 2007, Pennsylvania ranked 14th in mathematics, 12th in reading, and 10th in writing for 8th grade students.[161]

In 1988, the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed Act 169, which allows parents or guardians to homeschool their children as an option for compulsory school attendance. This law specifies the requirements and responsibilities of the parents and the school district where the family lives.[162]

Higher education

The Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education (PASSHE) is the public university system of the Commonwealth, with 14 state-owned schools. West Chester University has by far the largest student body of the 14 universities. The Commonwealth System of Higher Education is an organizing body of the four state-related schools in Pennsylvania; these schools (Pennsylvania State University, Lincoln University, the University of Pittsburgh, and Temple University) are independent institutions that receive some state funding. There are also 15 publicly funded two-year community colleges and technical schools that are separate from the PASSHE system. Additionally, there are many private two- and four-year technical schools, colleges, and universities.

Carnegie Mellon University, The Pennsylvania State University, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Pittsburgh are members of the Association of American Universities, an invitation-only organization of leading research universities. Lehigh University is a private research university located in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania State University is the Commonwealth's land-grant university, Sea Grant College and, Space Grant College. The University of Pennsylvania, located in Philadelphia, is considered the first university in the United States and established the country's first medical school. The University of Pennsylvania is also the Commonwealth's only, and geographically most southern, Ivy League school. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts is the first and oldest art school in the United States.[163] Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, now a part of University of the Sciences in Philadelphia, was the first pharmacy school in the United States.[164]

Recreation

Pennsylvania is home to the nation's first zoo, the Philadelphia Zoo.[165] Other long-accredited AZA zoos include the Erie Zoo and the Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium. The Lehigh Valley Zoo and ZOOAMERICA are other notable zoos. The Commonwealth boasts some of the finest museums in the country, including the Carnegie Museums in Pittsburgh, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and several others. One unique museum is the Houdini Museum in Scranton, the only building in the world devoted to the legendary magician.[166] Pennsylvania is also home to the National Aviary, located in Pittsburgh.

All 121 state parks in Pennsylvania feature free admission.

Pennsylvania offers a number of notable amusement parks, including Camel Beach, Conneaut Lake Park, Dorney Park & Wildwater Kingdom, Dutch Wonderland, DelGrosso's Amusement Park, Hersheypark, Idlewild Park, Kennywood, Knoebels, Lakemont Park, Sandcastle Waterpark, Sesame Place, Great Wolf Lodge and Waldameer Park. Pennsylvania also is home to the largest indoor waterpark resort on the East Coast, Splash Lagoon in Erie.

There are also notable music festivals that take place in Pennsylvania. These include Musikfest and NEARfest in Bethlehem, the Philadelphia Folk Festival, Creation Festival, the Great Allentown Fair, and Purple Door.

There are nearly one million licensed hunters in Pennsylvania. Whitetail deer, black bear, cottontail rabbits, squirrel, turkey, and grouse are common game species. Pennsylvania is considered one of the finest wild turkey hunting states in the Union, alongside Texas and Alabama. Sport hunting in Pennsylvania provides a massive boost for the Commonwealth's economy. A report from The Center for Rural Pennsylvania (a Legislative Agency of the Pennsylvania General Assembly) reported that hunting, fishing, and furtaking generated a total of $9.6 billion statewide.

The Boone and Crockett Club shows that five of the ten largest (skull size) black bear entries came from the state.[167] The state also has a tied record for the largest hunter shot black bear in the Boone & Crockett books at 733 lb (332 kg) and a skull of 23 3/16 tied with a bear shot in California in 1993.[167] The largest bear ever found dead was in Utah in 1975, and the second-largest was shot by a poacher in the state in 1987.[167] Pennsylvania holds the second-highest number of Boone & Crockett-recorded record black bears at 183, second only to Wisconsin's 299.[167]

Transportation

Road

The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, abbreviated as PennDOT, owns 39,861 miles (64,150 km) of the 121,770 miles (195,970 km) of roadway in the state, making it the fifth-largest state highway system in the United States.[168] The Pennsylvania Turnpike system is 535 miles (861 km) long, with the mainline portion stretching from Ohio to Philadelphia and New Jersey.[168] It is overseen by the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission. Another major east–west route is Interstate 80, which runs primarily in the northern tier of the state from Ohio to New Jersey at the Delaware Water Gap. Interstate 90 travels the relatively short distance between Ohio and New York through Erie County, in the extreme northwestern part of the state.

Primary north–south highways are Interstate 79 from its terminus in Erie through Pittsburgh to West Virginia, Interstate 81 from New York through Scranton, Lackawanna County and Harrisburg to Maryland and Interstate 476, which begins 7 miles (11 km) north of the Delaware border, in Chester, Delaware County and travels 132 miles (212 km) to Clarks Summit, Lackawanna County, where it joins I-81. All but 20 miles (32 km) of I-476 is the Northeast Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, while the highway south of the mainline of the Pennsylvania Turnpike is officially called the "Veterans Memorial Highway", but is commonly referred to by locals as the "Blue Route".

Rail

The Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) is the sixth-largest transit agency in the United States and operates the commuter, heavy and light rail transit, and transit bus service in the Philadelphia metropolitan area. The Port Authority of Allegheny County is the 25th-largest transit agency and provides transit bus and light rail service in and around Pittsburgh.[169]

Intercity passenger rail transit is provided by Amtrak, with the majority of traffic occurring on the Keystone Service in the high-speed Keystone Corridor between Harrisburg and Philadelphia's 30th Street Station before heading north to New York City, as well as the Northeast Regional providing frequent high-speed service up and down the Northeast Corridor. The Pennsylvanian follows the same route from New York City to Harrisburg, but extends out to Pittsburgh. The Capitol Limited also passes through Pittsburgh, as well as Connellsville, on its way from Chicago to Washington, D.C.[170] Traveling between Chicago and New York City, the Lake Shore Limited passes through Erie once in each direction.[170] There are 67 short-line, freight railroads operating in Pennsylvania, the highest number in any U.S. state.[170]

Bus and Coach

Intercity bus service is provided between cities in Pennsylvania and other major points in the Northeast by Bolt Bus, Fullington Trailways, Greyhound Lines, Martz Trailways, Megabus, OurBus, Trans-Bridge Lines, as well as various Chinatown bus companies. In 2018, OurBus began offering service from West Chester, PA – Malvern, PA – King of Prussia, PA – Fort Washington, PA – New York, NY.

Air

Pennsylvania has seven major airports: Philadelphia International, Pittsburgh International, Lehigh Valley International, Harrisburg International, Erie International, University Park Airport and Wilkes-Barre/Scranton International. A total of 134 public-use airports are located in the state.[170] The port of Pittsburgh is the second-largest inland port in the United States and the 18th-largest port overall; the Port of Philadelphia is the 24th-largest port in the United States.[171] Pennsylvania's only port on the Great Lakes is located in Erie.

Water

The Allegheny River Lock and Dam Two is the most-used lock operated by the United States Army Corps of Engineers of its 255 nationwide.[172] The dam impounds the Allegheny River near Downtown Pittsburgh.

Culture

Arts

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2017) |

Sports

Pennsylvania is home to many major league professional sports teams; the Philadelphia Phillies and Pittsburgh Pirates of Major League Baseball, the Philadelphia 76ers of the National Basketball Association, the Pittsburgh Steelers and Philadelphia Eagles of the National Football League, the Philadelphia Flyers and Pittsburgh Penguins of the National Hockey League, and the Philadelphia Union of Major League Soccer. Among them, these teams have accumulated 7 World Series Championships (Pirates 5, Phillies 2), 16 National League Pennants (Pirates 9, Phillies 7), 3 pre-Super Bowl era NFL Championships (Eagles), 7 Super Bowl Championships (Steelers 6, Eagles 1), 2 NBA Championships (76ers), and 7 Stanley Cups (Penguins 5, Flyers 2).

Pennsylvania also has minor league and semi-pro sports teams: the Triple-A baseball Lehigh Valley IronPigs and the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre RailRiders of the International League; the Double-A baseball Altoona Curve, Erie SeaWolves, Harrisburg Senators, and Reading Fightin Phils of the Eastern League; the Class A-Short Season baseball State College Spikes and Williamsport Crosscutters of the New York–Penn League; the independent baseball Lancaster Barnstormers and York Revolution of the Atlantic League of Professional Baseball; the independent baseball Washington Wild Things of the Frontier League; the Erie BayHawks of the NBA G League; the Lehigh Valley Phantoms, Wilkes-Barre/Scranton Penguins, and Hershey Bears of the American Hockey League; the Reading Royals and of the ECHL; and the Philadelphia Soul of the Arena Football League. Among them, these teams have accumulated 12 triple and double-A baseball league titles (RailRiders 1, Senators 6, Fightin Phils 4 Curve 1), 3 Arena Bowl Championships (Soul), and 11 Calder Cups (Bears).

The first World Series between the Boston Pilgrims (which became the Boston Red Sox) and Pittsburgh Pirates was played in Pittsburgh in 1903. Since 1959, the Little League World Series is held each summer in South Williamsport, near where Little League Baseball was founded in Williamsport.[173]

Soccer is gaining popularity within the state of Pennsylvania as well. With the addition of the Philadelphia Union in the MLS, the state now boasts three teams that are eligible to compete for the Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup annually. The other two teams are Philadelphia Union II and the Pittsburgh Riverhounds. However, Penn FC (formally Harrisburg City Islanders) used to be one of these teams before they announced they'd be on hiatus in 2019; although they would be returning for the 2020 season.[174] Both of the United Soccer League (USL). Within the American Soccer Pyramid, the MLS takes the first tier, while the USL-2 claims the third tier.

Arnold Palmer, one of the 20th century's most notable pro golfers, comes from Latrobe, while Jim Furyk, a current PGA member, grew up near in Lancaster. PGA tournaments in Pennsylvania include the 84 Lumber Classic, played at Nemacolin Woodlands Resort, in Farmington and the Northeast Pennsylvania Classic, played at Glenmaura National Golf Club, in Moosic.

Philadelphia is home to LOVE Park, once a popular spot for skateboarding, and across from City Hall, host to ESPN's X Games in 2001 and 2002.[175]

Racing

In motorsports, the Mario Andretti dynasty of race drivers hails from Nazareth in the Lehigh Valley. Notable racetracks in Pennsylvania include the Jennerstown Speedway in Jennerstown, the Lake Erie Speedway in North East, the Mahoning Valley Speedway in Lehighton, the Motordome Speedway in Smithton, the Mountain Speedway in St. Johns, the Nazareth Speedway in Nazareth (closed); and the Pocono Raceway in Long Pond, which is home to two NASCAR Cup Series races and an IndyCar Series race. The state is also home to Maple Grove Raceway, near Reading, which hosts major National Hot Rod Association sanctioned drag racing events each year.

There are also two motocross race tracks that host a round of the AMA Toyota Motocross Championships in Pennsylvania. High Point Raceway is located in Mt. Morris, Pennsylvania, and Steel City is located in Delmont, Pennsylvania.

Horse racing courses in Pennsylvania consist of The Meadows near Pittsburgh, Pocono Downs in Wilkes-Barre, and Harrah's Philadelphia in Chester, which offer harness racing, and Penn National Race Course in Grantville, Parx Racing (formerly Philadelphia Park) in Bensalem, and Presque Isle Downs near Erie, which offer thoroughbred racing. Smarty Jones, the 2004 Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes winner, had Philadelphia Park as his home course.

College sports

College football is popular in Pennsylvania.[citation needed] There are three colleges in Pennsylvania that play at the highest level of collegiate football competition, the NCAA Division I Football Bowl Subdivision. Two play in Power Five conferences, the Penn State University Nittany Lions of the Big Ten Conference and the University of Pittsburgh Panthers of the Atlantic Coast Conference, while the Temple University Owls play in the American Athletic Conference. Penn State claims two national championships (1982 & 1986) as well as seven undefeated seasons (1887, 1912, 1968, 1969, 1973, 1986 and 1994). Penn State plays its home games in the second-largest stadium in the United States, Beaver Stadium, which seats 106,572, and is currently led by head coach James Franklin. The University of Pittsburgh Panthers claims nine national championships (1915, 1916, 1918, 1929, 1931, 1934, 1936, 1937 and 1976) and has played eight undefeated seasons (1904, 1910, 1915, 1916, 1917, 1920, 1937 and 1976).[176] Pitt plays its home games at Heinz Field, a facility it shares with the Pittsburgh Steelers, and is led by current head football coach Pat Narduzzi. Other Pennsylvania schools that have won national titles in football include Lafayette College (1896), Villanova University (FCS 2009), the University of Pennsylvania (1895, 1897, 1904 and 1908)[177] and Washington and Jefferson College (1921).

College basketball is also popular in the state, especially in the Philadelphia area where five universities, collectively termed the Big Five, have a rich tradition in NCAA Division I basketball. National titles in college basketball have been won by La Salle University (1954), Temple University (1938), University of Pennsylvania (1920 and 1921), University of Pittsburgh (1928 and 1930), and Villanova University (1985, 2016, and 2018).[178][179]

Food

Author Sharon Hernes Silverman calls Pennsylvania the snack food capital of the world.[180] It leads all other states in the manufacture of pretzels and potato chips. The Sturgis Pretzel House introduced the pretzel to America, and companies like Anderson Bakery Company, Intercourse Pretzel Factory, and Snyder's of Hanover are leading manufacturers in the Commonwealth. Two of the three companies that define the U.S. potato chip industry are based in Pennsylvania: Utz Quality Foods, which started making chips in Hanover, Pennsylvania, in 1921, Wise Foods, which started making chips in Berwick in 1921, the third, Frito-Lay (part of PepsiCo, based in Plano, Texas). Other companies such as Herr's Snacks, Martin's Potato Chips, Snyder's of Berlin (not associated with Snyder's of Hanover) and Troyer Farms Potato Products are popular chip manufacturers.

The U.S. chocolate industry is centered in Hershey, Pennsylvania, with Mars, Godiva, and Wilbur Chocolate Company nearby, and smaller manufacturers such as Asher's[181] in Souderton,[182] and Gertrude Hawk Chocolates of Dunmore. Other notable companies include Just Born in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, makers of Hot Tamales, Mike and Ikes, the Easter favorite marshmallow Peeps, and Boyer Brothers of Altoona, Pennsylvania, which is well known for its Mallo Cups. Auntie Anne's Pretzels began as a market-stand in Downingtown, Pennsylvania, and now has corporate headquarters in Lancaster City.[183] Traditional Pennsylvania Dutch foods include chicken potpie, ham potpie, schnitz un knepp (dried apples, ham, and dumplings), fasnachts (raised doughnuts), scrapple, pretzels, bologna, chow-chow, and Shoofly pie. Martin's Famous Pastry Shoppe, Inc., headquartered in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, specializes in potato bread, another traditional Pennsylvania Dutch food. D.G. Yuengling & Son, America's oldest brewery, has been brewing beer in Pottsville since 1829.

Among the regional foods associated with Philadelphia are cheesesteaks, hoagie, soft pretzels, Italian water ice, Irish potato candy, scrapple, Tastykake, and strombolis. In Pittsburgh, tomato ketchup was improved by Henry John Heinz from 1876 to the early 20th century. Famous to a lesser extent than Heinz ketchup is the Pittsburgh's Primanti Brothers Restaurant sandwiches, pierogies, and city chicken. Outside of Scranton, in Old Forge there are dozens of Italian restaurants specializing in pizza made unique by thick, light crust and American cheese. Erie also has its share of unique foods, including Greek sauce and sponge candy. Sauerkraut along with pork and mashed potatoes is a common meal on New Year's Day in Pennsylvania.

State symbols

- Motto: "Virtue, liberty, and independence"

- Tree: Eastern hemlock[184]

- State bird: Ruffed grouse[185]

- Flower: Mountain laurel[185]

- Insect: Pennsylvania firefly[185]

- Animal: White-tailed deer[185]

- Amphibian: Eastern Hellbender[186]

- Dog: Great Dane[185]

- Fish: Brook trout[185]

- Fossil: Phacops rana[184]

- Beverage: Milk[184]

- Song: "Pennsylvania"[187]

- Ship: US Brig Niagara[184]

- Electric locomotive: GG1 4859[184]

- Steam locomotive: K4s 1361 and K4s 3750[184]

- Beautification and conservation plant: Penngift crown vetch[184]

Nicknames

Pennsylvania has been known as the Keystone State since 1802,[188] based in part upon its central location among the original Thirteen Colonies forming the United States, and also in part because of the number of important American documents signed in the state (such as the Declaration of Independence). It was also a keystone state economically, having both the industry common to the North (making such wares as Conestoga wagons and rifles)[189][190] and the agriculture common to the South (producing feed, fiber, food, and tobacco).[191]

Another one of Pennsylvania's nicknames is the Quaker State; in colonial times, it was known officially as the Quaker Province,[192] in recognition of Quaker[193] William Penn's First Frame of Government[194] constitution for Pennsylvania that guaranteed liberty of conscience. He knew of the hostility[195] Quakers faced when they opposed religious ritual, taking oaths, violence, war and military service, and what they viewed as ostentatious frippery.[196]

"The Coal State", "The Oil State", "The Chocolate State", and "The Steel State" were adopted when those were the state's greatest industries.[197]

"The State of Independence" currently appears on many road signs entering the state.

Notable people

Sister regions

Matanzas Province, Cuba[198]

Matanzas Province, Cuba[198] Rhône-Alpes, France[199]

Rhône-Alpes, France[199]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ "Symbols of Pennsylvania". Portal.state.pa.us. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988.

- ^ "Median Annual Household Income". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- ^ "Most spoken languages in Pennsylvania in 2010". MLA Data Center. Archived from the original on May 27, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- ^ "Cookie Candidates". 2016. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ a b "General Coastline and Shoreline Mileage of the United States" (PDF). NOAA Office of Coastal Management. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 25, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ "Pennsylvania geography". Netstate.com. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ 2006 Statistical Abstract: Geography & Environment: Land and Land Use[dead link]

- ^ "Pennsylvania Time Zone". Timetemperature.com. Archived from the original on January 9, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ "National Park Service: Our Fourth Shore". Cr.nps.gov. December 22, 2003. Archived from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ [1] Archived May 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ National Weather Service Corporate Image Web Team. "National Weather Service Climate". Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ National Weather Service Corporate Image Web Team. "National Weather Service Climate". Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ National Weather Service Corporate Image Web Team. "Climate Information—National Weather Service Central PA". Archived from the original on July 5, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ National Weather Service Corporate Image Web Team. "National Weather Service Climate". Archived from the original on July 5, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ National Weather Service Corporate Image Web Team. "National Weather Service Climate". Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ louis, franquelin, jean baptiste. "Franquelin's map of Louisiana". LOC.gov. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ (Extrapolation from the 16th-century Spanish, 'Cali' ˈkali a rich agricultural area—geographical sunny climate. also 1536, Cauca River, linking Cali, important for higher population agriculture and cattle raising & Colombia's coffee is produced in the adjacent uplands. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. 'Cali', city, metropolis, urban center. Pearson Education 2006. "Calica", Yucatán place name called rock pit, a port an hour south of Cancún. Sp. root: "Cal", limestone. Also today, 'Calicuas', supporting cylinder or enclosing ring, or moveable prop as in holding a strut)

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ N.Y. Hist. Col. Vol. V, p. 633

- ^ "Life of Brainerd" p. 167

- ^ "Lambreville to Bruyas Nov. 4,1696" N.Y. Hist. Col. Vol. III, p. 484

- ^ "Pennsylvania Indian tribes". Accessgenealogy.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2014. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ^ Hale, Horatio "The Iroquois Book of Rites" 1884.

- ^ Paullin, Charles O.; Wright, John K. (ed.) (1932). Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States. New York and Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington and American Geographical Society. pp. Plate 42.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - ^ Swindler, William F. (ed.) (1973–1979). Sources and Documents of United States Constitutions. Vol. 10. Dobbs Ferry, New York: Oceana Publications. pp. 17–23.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Van Zandt, Franklin K. (1976). Boundaries of the United States and the Several States. Geological Survey Professional Papers. Vol. 909. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 74, 92.

- ^ Munroe, John A. (1978). Colonial Delaware: A History. Millwood, New York: KTO Press. pp. 9–12.

- ^ Munroe, John A. (1978). Colonial Delaware: A History. Millwood, New York: KTO Press. p. 16.

- ^ McCormick, Richard P. (1964). New Jersey from Colony to State, 1609–1789. New Jersey Historical Series, Volume 1. Princeton, New Jersey: D. Van Nostrand Company. p. 12.

- ^ Swindler, William F., Editor (1973–1979). Sources and Documents of United States Constitutions. Vol. 4. Dobbs Ferry, New York: Oceana Publications. pp. 278–280.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Van Zandt, Franklin K. (1976). Boundaries of the United States and the Several States; Geological Survey Professional Paper 909. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 79.

- ^ Swindler, William F., Editor (1973–1979). Sources and Documents of United States Constitutions. Vol. 6. Dobbs Ferry, New York: Oceana Publications. pp. 375–377.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Farnham, Mary Frances; Compiler. (1901–1902). Farnham Papers (1603–1688). Volumes 7 and 8 of Documentary History of the State of Maine. Vol. 7. Portland, Maine: Collections of the Maine Historical Society, 2nd Series. pp. 311, 314.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Parry, Clive (Editor) (1969–1981). Consolidated Treaty Series; 231 Volumes. Vol. 10. Dobbs Ferry, New York: Oceana Publications. p. 231.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Fernow, B., Editor (1853–1887). Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York; Volumes 12–15. Albany, New York. pp. 507–508. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Parry, Clive (Editor) (1969–1981). Consolidated Treaty Series; 231 Volumes. Vol. 13. Dobbs Ferry, New York: Oceana Publications. p. 136.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Fernow, B., Editor (1853–1887). Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York; Volumes 12–15. Vol. 12. Albany, New York. p. 515.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Armstrong, Edward; Editor (1860). Record of the Court at Upland, in Pennsylvania, 1676 to 1681. Memoirs of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania Volume 7. pp. 119, 198.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Charter for the Province of Pennsylvania-1681 Archived April 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. This charter, granted by Charles II (England) to William Penn, constituted him and his heirs proprietors of the province, which, in honor of his father, Admiral William Penn, (whose cash advances and services were thus requited,) was called Pennsylvania. To perfect his title, William Penn purchased, on 1682-08-24, a quit-claim from the Duke of York to the lands west of the Delaware River embraced in his patent of 1664