Religious conversion

| Part of a series on |

| Religious conversion |

|---|

| Types |

| Related concepts |

Religious conversion is the adoption of a set of beliefs identified with one particular religious denomination to the exclusion of others. Thus "religious conversion" would describe the abandoning of adherence to one denomination and affiliating with another. This might be from one to another denomination within the same religion, for example, Christian Baptist to Methodist or Catholic,[1] Muslim Shi'a to Sunni.[2] In some cases, religious conversion "marks a transformation of religious identity and is symbolized by special rituals".[3]

People convert to a different religion for various reasons, including: active conversion by free choice due to a change in beliefs,[4] secondary conversion, deathbed conversion, conversion for convenience and marital conversion, and forced conversion such as conversion by violence or charity.[clarification needed]

Conversion or reaffiliation for convenience is an insincere act, sometimes for relatively trivial reasons such as a parent converting to enable a child to be admitted to a good school associated with a religion, or a person adopting a religion more in keeping with the social class he or she aspires to.[5] When people marry one spouse may convert to the religion of the other.

Forced conversion is adoption of a different religion under duress. The convert may secretly retain the previous beliefs and continue, covertly, with the practices of the original religion, while outwardly maintaining the forms of the new religion. Over generations a family forced against their will to convert may wholeheartedly adopt the new religion.

Proselytism is the act of attempting to convert by persuasion another individual from a different religion or belief system. (See proselyte).

Apostate is a term used by members of a religion or denomination to refer to someone who has left that religion or denomination.

Abrahamic religions

Judaism

This section possibly contains original research. (September 2007) |

This section needs attention from an expert in Judaism. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the section. (July 2007) |

Procedure

Jewish law has a number of requirements of potential converts. They should desire conversion to Judaism for its own sake, and for no other motives. A male convert needs to undergo a ritual circumcision conducted according to Jewish law (if already circumcised, a needle is used to draw a symbolic drop of blood while the appropriate blessings are said), and there has to be a commitment to observe Jewish law. A convert must join the Jewish community, and reject the previous theology he or she had prior to the conversion. Ritual immersion in a small pool of water known as a mikvah is required.

History

In Hellenistic and Roman times, some Pharisees were eager proselytizers, and had at least some success throughout the empire.

Some Jews are also descended from converts to Judaism outside the Mediterranean world. It is known that some Khazars, Edomites, and Ethiopians, as well as many Arabs, particularly in Yemen. The word "proselyte" originally meant a Greek who had converted to Judaism. As late as the 6th century the Eastern Roman empire and Caliph Umar ibn Khattab were issuing decrees against conversion to Judaism, implying that this was still occurring.[6]

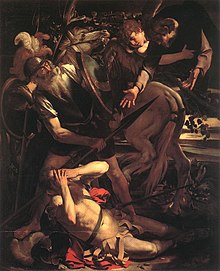

Christianity

Conversion to Christianity is the religious conversion of a previously non-Christian person to some form of Christianity. The exact requirements vary between different churches and denominations, however, all schools of thought in Christianity agree that baptism is a compulsory prerequisite mentioned in the Bible that historically took place in the fist century AD where infidels were required to undergo so as to be ultimately accepted in the Kingdom of God. Converting for instance to Catholicism involves religious education followed by initial participation in the sacraments. In general, conversion to Christian Faith primarily involves repentance for sin and a decision to live a life that is holy and acceptable to God through faith in the atoning death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. All of this is essentially done through a voluntary exercise of the will of the individual concerned. True conversion to Christianity is thus a personal, internal matter and can never be forced.

Christians consider that conversion requires internalization of the new belief system. It implies a new reference point for the convert's self-identity, and is a matter of belief and social structure—of both faith and affiliation.[7] This typically entails the sincere avowal of a new belief system, but may also present itself in other ways, such as adoption into an identity group or spiritual lineage.

Baptism

Catholics, and Orthodox denominations encourage infant baptism before children are aware of their status. In Roman Catholicism and certain high church forms of Protestantism, baptized children are expected to participate in confirmation classes as pre-teens. In Eastern Orthodoxy, the equivalent of confirmation, chrismation, is administered to all converts, adult and infant alike, immediately after baptism.

Methods of baptism include immersion, sprinkling (aspersion) and pouring (affusion).[8] Baptism received by adults or younger people who have reached the age of accountability where they can make a personal religious decision is referred to as believer's baptism among conservative or evangelical Protestant groups. It is intended as a public statement of a person's prior decision to become a Christian.[9] Some Christian groups such as Catholics, Churches of Christ, and Christadelphians believe baptism is essential to salvation.

Accepting Christ and renouncing sin

“Conversion” derives from the Latin conversiōn-em, literally meaning “turning round” and figuratively meaning a “change in character”.[11] “Change of heart”, “metanoia”, and “regeneration” are among the synonyms for conversion.[12] Conversion is, therefore, more than a mere change in religious identity, but a change in nature (regeneration), evidenced by a change in values. Jesus demands "metánoia (conversion)" to become a good tree that bears good fruit (Matthew 7:17–18, Luke 6:43).[13]

According to Christianity, a convert renounces sin as worthless and treasures instead the supreme worth of Christ in Jesus' sacrificial death and resurrection.[14] Christian conversion is a “deeply personal” matter. It entails changes in thinking, priorities and commitments: “a whole new direction in one's life”.[15]

Because conversion is a change in values that embraces God and rejects sin, it includes a personal commitment to a life of holiness as described by Paul of Tarsus and exemplified by Jesus. In some Protestant traditions, this is called "accepting Christ as one's Savior and following him as Lord."[16] In another variation, the 1910 Catholic Dictionary defines "conversion" as "One who turns or changes from a state of sin to repentance, from a lax to a more earnest and serious way of life, from unbelief to faith, from heresy to the true faith."[17] The Eastern Orthodox understanding of conversion is illustrated in the rite of baptism, in which the convert faces west while publicly renouncing and symbolically spitting upon Satan, and then turns to the east to worship Christ "as king and God".[18]

Responsibilities

In the New Testament, Jesus commanded his disciples in the Great Commission to "go and make disciples of all nations" (Matthew 28:19, Mark 16:15). Evangelization—sharing the Gospel message or "Good News" in deed and word, is an expectation of Christians.[citation needed]

Reaffiliation

Transferring from one Christian denomination to another may consist of a relatively simple transfer of membership, especially if moving from one Trinitarian denomination to another, and if the person has received water baptism in the name of the Trinity. If not, then the person may be required to be baptized or rebaptized before acceptance by the new church. Some denominations, such as those in the Anabaptist tradition, require previously baptized Christians to be re-baptized. The Eastern Orthodox Church treats a transfer from another denomination of Christianity to Orthodoxy (conceived of as the one true Church) as a category of conversion and repentance, though re-baptism is not always required.

The process of conversion to Christianity varies somewhat among Christian denominations. Most Protestants believe in conversion by faith to attain salvation. According to this understanding, a person professes faith in Jesus Christ as God, their Lord and savior. Repentance for sin and a holy living are expected of those professing faith in Jesus Christ. While an individual may make such a decision privately, usually it entails being baptized and becoming a member of a denomination or church. In these traditions, a person is considered to become a Christian by publicly acknowledging the foundational Christian doctrines that Jesus Christ died, was buried, and was resurrected for the remission of sins.[citation needed]

Comparison between Protestants

This table summarizes three Protestant beliefs.

| Topic | Calvinism | Lutheranism | Arminianism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conversion | Monergistic,[19] through the inner calling of the Holy Spirit, irresistible. | Monergistic,[20] through the means of grace, resistible. | Synergistic, resistible due to the common grace of free will.[21] |

Latter Day Saint movement

Much of the theology of Latter Day Saint baptism was established during the early Latter Day Saint movement founded by Joseph Smith. According to this theology, baptism must be by immersion, for the remission of sins (meaning that through baptism, past sins are forgiven), and occurs after one has shown faith and repentance. Mormon baptism does not purport to remit any sins other than personal ones, as adherents do not believe in original sin. Latter Day Saints baptisms also occur only after an "age of accountability" which is defined as the age of eight years.[22] The theology thus rejects infant baptism.[23]

In addition, Latter Day Saint theology requires that baptism may only be performed with one who has been called and ordained by God with priesthood authority.[24] Because the churches of the Latter Day Saint movement operate under a lay priesthood, children raised in a Mormon family are usually baptized by a father or close male friend or family member who has achieved the office of priest, which is conferred upon worthy male members at least 16 years old in the LDS Church.[25]

Baptism is seen as symbolic both of Jesus' death, burial and resurrection[26] and is also symbolic of the baptized individual putting off of the natural or sinful man and becoming spiritually reborn as a disciple of Jesus.

Membership into a Latter Day Saint church is granted only by baptism whether or not a person has been raised in the church. Latter Day Saint churches do not recognize baptisms of other faiths as valid because they believe baptisms must be performed under the church's unique authority. Thus, all who come into one of the Latter Day Saint faiths as converts are baptized, even if they have previously received baptism in another faith.

When performing a Baptism, Latter Day Saints say the following prayer before performing the ordinance:

Having been commissioned of Jesus Christ, I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen[27]

Baptisms inside and outside the temples are usually done in a baptistry, although they can be performed in any body of water in which the person may be completely immersed. The person administering the baptism must recite the prayer exactly, and immerse every part, limb, hair and clothing of the person being baptized. If there are any mistakes, or if any part of the person being baptized is not fully immersed, the baptism must be redone. In addition to the baptizer, two priesthood holders witness the baptism to ensure that it is performed properly.[28]

Following baptism, Latter Day Saints receive the Gift of the Holy Ghost by the laying on of hands of a Melchizedek Priesthood holder.[28]

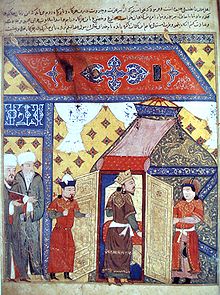

Islam

This section needs attention from an expert in Islam. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the section. (September 2013) |

There are five pillars, or foundations, of Islam but the primary, and most important is to believe that there is only one God and creator, referred to as Allah (the word for the name of God in Arabic) and that the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, is His final messenger. A person is considered to have converted to Islam from the moment he or she sincerely makes this declaration of faith, called the shahadah.[29][30]

Islam teaches that everyone is Muslim at birth[31][32] because every child that is born has a natural inclination to goodness and to worship the one true God alone, but his or her parents or society can cause him or her to deviate from the straight path. When someone accepts Islam he/she is considered to revert to his/her original condition. While conversion to Islam is among its most supported tenets, conversion from Islam to another religion is considered to be the sin of apostasy. In several Muslim majority countries it is subject to the death penalty or heavy punishments. In Islam, circumcision is a Sunnah custom not mentioned in the Quran. The primary opinion is that it is not obligatory and is not a condition for entering into Islam. The Shafi`i and Hanbali schools regard it as obligatory, while the Maliki and Hanafi schools regard it as only recommended. However, it is not a precondition for the acceptance of a person's Islamic practices, nor does one sin if choosing to forgo circumcision. It is not one of the Five Pillars of Islam or the Six Fundamentals of Belief.[33][34][35]

According to Abul A'la Maududi, people should accept Islam through their own free choice, not through compulsion. Even though Maududi believes in the superiority of Islam, he insists that if persons elect not to embrace Islam, Muslims must avoid placing political or social pressure on them to convert.[36]

Bahá'í Faith

In sharing their faith with others, Bahá'ís are cautioned to "obtain a hearing" – meaning to make sure the person they are proposing to teach is open to hearing what they have to say. "Bahá'í pioneers", rather than attempting to supplant the cultural underpinnings of the people in their adopted communities, are encouraged to integrate into the society and apply Bahá'í principles in living and working with their neighbors.

Bahá'ís recognize the divine origins of all revealed religion, and believe that these religions occurred sequentially as part of a Divine plan (see Progressive revelation), with each new revelation superseding and fulfilling that of its predecessors. Bahá'ís regard their own faith as the most recent (but not the last), and believe its teachings – which are centered around the principle of the oneness of humanity – are most suited to meeting the needs of a global community.

In most countries conversion is a simple matter of filling out a card stating a declaration of belief. This includes acknowledgement of Bahá'u'llah – the Founder of the Faith – as the Messenger of God for this age, awareness and acceptance of His teachings, and intention to be obedient to the institutions and laws He established.

Conversion to the Bahá'í Faith carries with it an explicit belief in the common foundation of all revealed religion, a commitment to the unity of mankind, and active service to the community at large, especially in areas that will foster unity and concord. Since the Bahá'í Faith has no clergy, converts to this Faith are encouraged to be active in all aspects of community life. Even a recent convert may be elected to serve on a Local Spiritual Assembly – the guiding Bahá'í institution at the community level.[37][38]

Indian religions

Hinduism

Since 1800 CE, religious conversion from and to Hinduism has been a controversial subject within Hinduism. Some have suggested that the concept of missionary conversion, either way, is anathema to the precepts of Hinduism.[39] Religious leaders of some of Hinduism sects such as Brahmo Samaj have seen Hinduism as a non-missionary religion yet welcomed new members, while other leaders of Hinduism's diverse schools have stated that with the arrival of missionary Islam and Christianity in India, this "there is no such thing as proselytism in Hinduism" view must be re-examined.[39][40]

Hinduism is a diverse system of thought with beliefs spanning monotheism, polytheism, panentheism, pantheism, pandeism, monism, and atheism among others. Hinduism has no traditional ecclesiastical order, no centralized religious authorities, no universally accepted governing body, no prophet(s), no binding holy book nor any mandatory prayer attendance requirements.[41][42][43] Hinduism has been described as a way of life.[41] In its diffuse and open structure, numerous schools and sects of Hinduism have developed and spun off in India with help from its ascetic scholars, since the Vedic age. The six Astika and two Nastika schools of Hindu philosophy, in its history, did not develop a missionary or proselytization methodology, and they co-existed with each other. Most Hindu sub-schools and sects do not actively seek converts.[44] Individuals have had a choice to enter, leave or change their god(s), spiritual convictions, accept or discard any rituals and practices, and pursue spiritual knowledge and liberation (moksha) in different ways.[45][46] However, various schools of Hinduism do have some core common beliefs, such as the belief that all living beings have Atman (soul), a belief in karma theory, spirituality, ahimsa (non-violence) as the greatest dharma or virtue, and others.[47]

Religious conversion to Hinduism has a long history outside India. Merchants and traders of India, particularly from Indian peninsula, carried their religious ideas, which led to religious conversions to Hinduism in Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia and Burma.[48][49][50] Some sects of Hindus, particularly of the Bhakti schools began seeking or accepting converts in early to mid 20th century. For example, Arya Samaj, Saiva Siddhanta Church, BAPS, and the International Society for Krishna Consciousness accept those who have a desire to follow their sects of Hinduism, and each has their own religious conversion procedure.[51]

In recent decades, mainstream Hinduism schools have attempted to systematize ways to accept religious converts, with an increase in inter-religious mixed marriages.[52] The steps involved in becoming a Hindu have variously included a period where the interested person gets an informal ardha-Hindu name and studies ancient literature on spiritual path and practices (English translations of Upanishads, Agamas, Epics, ethics in Sutras, festivals, yoga).[53] If after a period of study, the individual still wants to convert, a Namakarana Samskaras ceremony is held, where the individual adopts a traditional Hindu name. The initiation ceremony may also include Yajna (i.e., fire ritual with Sanskrit hymns) under guidance of a local Hindu priest.[52] Some of these places are mathas and asramas (hermitage, monastery), where one or more gurus (spiritual guide) conduct the conversion and offer spiritual discussions.[52] Some schools encourage the new convert to learn and participate in community activities such as festivals (Diwali etc), read and discuss ancient literature, learn and engage in rites of passages (ceremonies of birth, first feeding, first learning day, age of majority, wedding, cremation and others).[54]

Sikhism

Sikhism is not known to openly proselytize, but accepts converts.[55][56]

Jainism

Jainism accepts anyone who wants to embrace the religion. There is no specific ritual for becoming a Jain. One does not need to ask any authorities for admission. One becomes a Jain on one's own by observing the five vows (vratas)[57] The five main vows as mentioned in the ancient Jain texts like Tattvarthasutra are:[58][59]

- Ahimsa- Not to injure any living being by actions and thoughts.

- Satya- Not to lie or speak words that hurts

- Asteya- Not to take anything if not given.[60]

- Brahmacharya- Chastity for householders / Celibacy in action, words & thoughts for monks and nuns.

- Aparigraha (Non-possession)- non-attachment to possessions.[61]

Following the five vows is the main requirement in Jainism. All other aspects such as visiting temples are secondary. Jain monks and nuns are required to observe these five vows strictly.[57]

Buddhism

Persons newly adhering to Buddhism traditionally "take Refuge" (express faith in the Three Jewels—Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha) before a monk, nun, or similar representative. But cultural or secular Buddhists often hold multiple religious identities, combining the religion with some East Asian religions in different countries and ethnics, such as:

| Ethnic | Buddhism with local traditional religions |

|---|---|

| Chinese[62] | Mahayana Buddhism with Confucianism, Taoism, and Chinese folk religion[63][64][65] |

| Japanese[62] | Mahayana Buddhism with Shinto[66][67][68] |

| Korean[62] | Mahayana Buddhism with Confucianism, and Korean shamanism[69][70][71][72] |

| Vietnamese[62] | Mahayana Buddhism with Confucianism, Taoism,[73][74] and Dao Mau[75] |

| Mongolian | Vajrayana Buddhism with Tengrism, and Mongolian shamanism[76] |

| Nepali | Vajrayana Buddhism with Hinduism[77] |

| Jewish Buddhist | Buddhism with Judaism |

Throughout the timeline of Buddhism, conversions of entire countries and regions to Buddhism were frequent, as Buddhism spread throughout Asia. For example, in the 11th century in Burma, king Anoratha converted his entire country to Theravada Buddhism. At the end of the 12th century, Jayavarman VII set the stage for conversion of the Khmer people to Theravada Buddhism. Mass conversions of areas and communities to Buddhism occur up to the present day, for example, in the Dalit Buddhist movement in India there have been organized mass conversions.

Exceptions to encouraging conversion may occur in some Buddhist movements. In Tibetan Buddhism, for example, the current Dalai Lama discourages active attempts to win converts.[78][79]

Other religions and sects

In the second half of the 20th century, the rapid growth of new religious movements (NRMs) led some psychologists and other scholars to propose that these groups were using "brainwashing" or "mind control" techniques to gain converts. This theory was publicized by the popular news media but disputed by other scholars, including some sociologists of religion.[80][81][81][82][83][84]

In the 1960s sociologist John Lofland lived with Unification Church missionary Young Oon Kim and a small group of American church members in California and studied their activities in trying to promote their beliefs and win converts to their church. Lofland noted that most of their efforts were ineffective and that most of the people who joined did so because of personal relationships with other members, often family relationships.[85] Lofland published his findings in 1964 as a doctoral thesis entitled "The World Savers: A Field Study of Cult Processes", and in 1966 in book form by Prentice-Hall as Doomsday Cult: A Study of Conversion, Proselytization, and Maintenance of Faith. It is considered to be one of the most important and widely cited studies of the process of religious conversion, and one of the first modern sociological studies of a new religious movement.[86][87]

The Church of Scientology attempts to gain converts by offering "free stress tests".[88] It has also used the celebrity status of some of its members (most famously the American actor Tom Cruise) to attract converts.[89][90] The Church of Scientology requires that all converts sign a legal waiver which covers their relationship with the Church of Scientology before engaging in Scientology services.[91]

Research in the United States and the Netherlands has shown a positive correlation between areas lacking mainstream churches and the percentage of people who are a member of a new religious movement. This applies also for the presence of New Age centres.[92][93]

On the other end of the scale are religions that do not accept any converts, or do so very rarely. Often these are relatively small, close-knit minority religions that are ethnically based such as the Yazidis, Druze, and Mandaeans. Zoroastrianism classically does not accept converts, but this issue has become controversial in the 20th century due to the rapid decline in membership.[citation needed] Chinese traditional religion lacks clear criteria for membership, and hence for conversion. The Shakers and some Indian eunuch brotherhoods do not allow procreation, so that every member is a convert.

International law

The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights defines religious conversion as a human right: "Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief" (Article 18). Despite this UN-declared human right, some groups forbid or restrict religious conversion (see below).

Based on the declaration the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) drafted the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, a legally binding treaty. It states that "Everyone shall have the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. This right shall include freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice" (Article 18.1). "No one shall be subject to coercion which would impair his freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice" (Article 18.2).

The UNCHR issued a General Comment on this Article in 1993: "The Committee observes that the freedom to 'have or to adopt' a religion or belief necessarily entails the freedom to choose a religion or belief, including the right to replace one's current religion or belief with another or to adopt atheistic views [...] Article 18.2 bars coercion that would impair the right to have or adopt a religion or belief, including the use of threat of physical force or penal sanctions to compel believers or non-believers to adhere to their religious beliefs and congregations, to recant their religion or belief or to convert." (CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.4, General Comment No. 22.; emphasis added)

Some countries distinguish voluntary, motivated conversion from organized proselytism, attempting to restrict the latter. The boundary between them is not easily defined: what one person considers legitimate evangelizing, or witness-bearing, another may consider intrusive and improper. Illustrating the problems that can arise from such subjective viewpoints is this extract from an article by Dr. C. Davis, published in Cleveland State University's Journal of Law and Health: "According to the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, Jews for Jesus and Hebrew Christians constitute two of the most dangerous cults, and its members are appropriate candidates for deprogramming. Anti-cult evangelicals ... protest that 'aggressiveness and proselytizing ... are basic to authentic Christianity,' and that Jews for Jesus and Campus Crusade for Christ are not to be labeled as cults. Furthermore, certain Hassidic groups who physically attacked a meeting of the Hebrew Christian 'cult' have themselves been labeled a 'cult' and equated with the followers of Reverend Moon, by none other than the President of the Central Conference of American Rabbis."[94]

Since the collapse of the former Soviet Union the Russian Orthodox Church has enjoyed a revival. However, it takes exception to what it considers illegitimate proselytizing by the Roman Catholic Church, the Salvation Army, Jehovah's Witnesses, and other religious movements in what it refers to as its canonical territory.[citation needed]

Greece has a long history of conflict, mostly with Jehovah's Witnesses, but also with some Pentecostals, over its laws on proselytism. This situation stems from a law passed in the 1930s by the dictator Ioannis Metaxas. A Jehovah's Witness, Minos Kokkinakis, won the equivalent of $14,400 in damages from the Greek state after being arrested for trying to preach his faith from door to door. In another case, Larissis v. Greece, a member of the Pentecostal church also won a case in the European Court of Human Rights.[citation needed]

Some Islamic countries with Islamic law outlaw and carry strict sentences for proselytizing. Several Islamic countries under Islamic law—Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Egypt, Iran, and Maldives—outlaw apostasy and carry imprisonment or the death penalty for those leaving Islam and those enticing Muslims to leave Islam.[citation needed] Also, induced religious conversions in the Indian states Orissa has resulted in communal riots.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ More conservative Protestants, especially Fundamentalists, would view a "reaffiliation" to Catholicism as a conversion to a new religion.

- ^ Stark, Rodney and Roger Finke. "Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion." University of California Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-520-22202-1

- ^ Meintel, Deirdre. "When There Is No Conversion: Spiritualists and Personal Religious Change". Anthropologica. 49 (1): 149–162.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Falkenberg, Steve. "Psychological Explanations of Religious Socialization." Religious Conversion. Eastern Kentucky University. August 31, 2009.

- ^ The Independent newspaper: "... finding religion – is there anything middle-class parents won't try to get their children into the 'right' schools?"

- ^ http://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/pact-umar.asp

- ^ Hefner, Robert W. Conversion to Christianity. University of California Press, 1993. ISBN 0-520-07836-5

- ^ Bromiley, Geoffrey W. "Baptism." The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A-D (p. 419). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1995. ISBN 0-8028-3781-6

- ^ "The Purpose of Baptism." http://gospelway.com/salvation/baptism_purpose.php

- ^ Augsburg Confession, Article XII: Of Repentance

- ^ "conversion, n.". OED Online. September 2013. Oxford University Press.

- ^ http://thesaurus.com/browse/conversion

- ^ Gerhard Kittel and Gerhard Friedrich, eds, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament: Abridged in One Volume by Geoffrey W. Bromily (Eerdmans, 1985) 101, 403.

- ^ Conversion to Christ: The Making of a Christian Hedonist

- ^ “St. Paul on Conversion” at http://jesuschristsavior.net/Conversion.html. Accessed November 5, 2013

- ^ BibleGateway.com- Commentaries » Matthew 16 » The Cost of the Kingdom

- ^ New Catholic Dictionary: conversion

- ^ † Saints Constantine & Elena: Reception into the Catechumenate

- ^ Paul ChulHong Kang, Justification: The Imputation of Christ's Righteousness from Reformation Theology to the American Great Awakening and the Korean Revivals (Peter Lang, 2006), 70, note 171. Calvin generally defends Augustine’s “monergistic view.”

- ^ http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Monergism and Paul ChulHong Kang, Justification: The Imputation of Christ's Righteousness from Reformation Theology to the American Great Awakening and the Korean Revivals (Peter Lang, 2006), 65.

- ^ Roger E. Olson, Arminian Theology: Myths and Realities (InterVarsity Press, 2009), 18. “Arminian synergism” refers to “evangelical synergism, which affirms the prevenience of grace.”

- ^ See Doctrine and Covenants 68:25–27

- ^ See Moroni 8:4–23

- ^ See, e.g., "Guide to the Scriptures: Baptism, Baptize: Proper authority", LDS.org, LDS Church

- ^ See, e.g., "Gospel Topics: Priest", LDS.org, LDS Church

- ^ See, e.g., "Baptism", KJV (LDS): LDS Bible Dictionary, LDS Church

- ^ See 3 Nephi 11:25

- ^ a b "Performing Priesthood Ordinances", Duties and Blessings of the Priesthood: Basic Manual for Priesthood Holders, Part B, LDS Church, 2000, pp. 41–48

- ^ Converts to Islam

- ^ How to Become a Muslim - Meeting Place for Reverts/Converts To Islam

- ^ Every Child is Born Muslim

- ^ Conversion to Islam

- ^ Is Circumcision obligatory after conversion?

- ^ Considering Converting: Is it necessary to be circumcised?

- ^ Circumcision for Converts

- ^ Oh, Irene (2007). "4". The Rights of God: Islam, Human Rights, and Comparative Ethics. Georgetown University Press. p. 76. ISBN 9781589011854.

- ^ Smith, P. (1999). A Concise Encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ^ Momen, M. (1997). A Short Introduction to the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford, UK: One World Publications. ISBN 1-85168-209-0.

- ^ a b Arvind Sharma (2011), Hinduism as a Missionary Religion, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1438432113, pages 31-53

- ^ Gauri Viswanathan (1998), Outside the Fold: Conversion, Modernity, and Belief, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691058993, pages 153-176

- ^ a b Chakravarti, Sitansu (1991), Hinduism, a way of life, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., p. 71, ISBN 978-81-208-0899-7

- ^ Julius J. Lipner, Hindus: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-45677-7, page 8; Quote: “(...) one need not be religious in the minimal sense described to be accepted as a Hindu by Hindus, or describe oneself perfectly validly as Hindu. One may be polytheistic or monotheistic, monistic or pantheistic, even an agnostic, humanist or atheist, and still be considered a Hindu.”

- ^ MK Gandhi, The Essence of Hinduism, Editor: VB Kher, Navajivan Publishing, see page 3; According to Gandhi, "a man may not believe in God and still call himself a Hindu."

- ^ Catharine Cookson (2003), Encyclopedia of religious freedom, Taylor & Francis, p. 180, ISBN 978-0-415-94181-5

- ^ Bhavasar and Kiem, Spirituality and Health, in Hindu Spirituality, Editor: Ewert Cousins (1989), ISBN 0-8245-0755-X, Crossroads Publishing New York, pp 319-337; John Arapura, Spirit and Spiritual Knowledge in the Upanishads, in Hindu Spirituality, Editor: Ewert Cousins (1989), ISBN 0-8245-0755-X, Crossroads Publishing New York, pp 64-85

- ^ Gavin Flood, Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Editor: Knut Jacobsen (2010), Volume II, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-17893-9, see Article on Wisdom and Knowledge, pp 881-884

- ^ SS Subramuniyaswami (2000), How to become a Hindu, 2nd Edition, Himalayan Academy, ISBN 0945497822, page 153

- ^ Jan Gonda, The Indian Religions in Pre-Islamic Indonesia and their survival in Bali, in Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 3 Southeast Asia, Religions at Google Books, pages 1-47

- ^ Richadiana Kartakusama (2006), Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective (Editors: Truman Simanjuntak et al.), Yayasan Obor Indonesia, ISBN 979-2624996, pp. 406-419

- ^ Reuter, Thomas (September 2004). Java's Hinduism Revivial. Hinduism Today.

- ^ See, for example: ISKCON Law Book, International Society for Krishna Consciousness, GBC Press

- ^ a b c SS Subramuniyaswami (2000), How to become a Hindu, 2nd Edition, Himalayan Academy, ISBN 0945497822, pages 115-118 Cite error: The named reference "subramuni" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ SS Subramuniyaswami (2000), How to become a Hindu, 2nd Edition, Himalayan Academy, ISBN 0945497822, pages xx, 133-147

- ^ SS Subramuniyaswami (2000), How to become a Hindu, 2nd Edition, Himalayan Academy, ISBN 0945497822, pages 157-158

- ^ ThinkQuest - Sikhism

- ^ About.com - Sikhism

- ^ a b Pravin Shah, Five Great Vows (Maha-vratas) of Jainism Jainism Literature Center, Harvard University Archives (2009)

- ^ Jain 2011, p. 93.

- ^ Sangave 2001, p. 67.

- ^ Jain 2011, p. 99.

- ^ Jain 2011, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d "Think Quest - Map of religions". Think Quest. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ^ Travel China Guide – Han Chinese, Windows on Asia – Chinese Religions, Justchina.org - China Beliefs, Foreignercn.com - Buddhism in China

- ^ Asia Society - Chinese Belief Systems

- ^ Asia Society - Buddhism in China

- ^ "World Factbook: Japan". CIA. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (15 September 2006). "International Religious Freedom Report 2006". US Department of State. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Asia Society - Shinto

- ^ Buddhism in Korea, Korean Buddhism Magazine, Seoul 1997

- ^ Asia Society - Historical and Modern Religions of Korea

- ^ "Culture of North Korea – Alternative name, History and ethnic relations". Countries and Their Cultures. Advameg Inc. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ "CIA The World Factbook – North Korea". Cia.gov. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ "Vietnam". Encyclopedia of the Nations. 14 August 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Vietnam's religions". Vietnam-holidays.co.uk. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Asia Society - Religions in Vietnam

- ^ Asian History - Mongolia | Facts and History, Windows on Asia - Mongolia, Mongolia Tourism - Religion

- ^ Nepal Embassy in Japan, Globerove - Religion in Nepal, Mongolia Asian History - Nepal, Windows on Asia - Nepal

- ^ Dalai Lama opposed to practice of conversion Archived 2012-02-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dawei, Bei (2012). Conversion to Tibetan Buddhism: Some Reflections, in: Ura, Dasho, Karma: Chophel, Dendup, Buddhism Without Borders, Proceedings of the International Conference of Global Buddhism, Bhumtang, Bhutan, May 211-23, 2012, The Center for Buthane Studies, pp, 53-75

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (1999-12-10). "Brainwashing and the Cults: The Rise and Fall of a Theory". CESNUR: Center for Studies on New Religions. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

In the United States at the end of the 1970s, brainwashing emerged as a popular theoretical construct around which to understand what appeared to be a sudden rise of new and unfamiliar religious movements during the previous decade, especially those associated with the hippie street-people phenomenon.

- ^ a b Bromley, David G. (1998). "Brainwashing". Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-7619-8956-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Barker, Eileen: New Religious Movements: A Practical Introduction. London: Her Majesty's Stationery office, 1989.

- ^ Wright, Stewart A. (1997). "Media Coverage of Unconventional Religion: Any 'Good News' for Minority Faiths?". Review of Religious Research. 39 (2). Review of Religious Research, Vol. 39, No. 2: 101–115. doi:10.2307/3512176. JSTOR 3512176.

- ^ Barker, Eileen (1986). "Religious Movements: Cult and Anti-Cult Since Jonestown". Annual Review of Sociology. 12: 329–346. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.001553.

- ^ Conversion, Unification Church, Encyclopedia of Religion and Society, Hartford Institute for Religion Research, Hartford Seminary

- ^ Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America: African diaspora traditions and other American innovations, Volume 5 of Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America, W. Michael Ashcraft, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006 ISBN 0-275-98717-5, ISBN 978-0-275-98717-6, page 180

- ^ Exploring New Religions, Issues in contemporary religion, George D. Chryssides, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2001 ISBN 0-8264-5959-5, ISBN 978-0-8264-5959-6 page 1

- ^ The Foster Report. Chapter 5, "The Practices of Scientology;" section (a), "Recruitment;" pages 75-76.

- ^ "Artists Find Inspiration, Education at Church of Scientology & Celebrity Centre Nashville." The Tennessee Tribune, Jan 20-Jan 26, 2011. Vol. 22, Iss. 3, pg. 14A

- ^ Goodyear, Dana (2008-01-14). "Château Scientology". Letter from California. The New Yorker. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ Friedman, Roger (3 September 2003). "Will Scientology Celebs Sign 'Spiritual' Contract?". FOX News. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ^ Schepens, T. (Dutch) Religieuze bewegingen in Nederland volume 29, Sekten Ontkerkelijking en religieuze vitaliteit: nieuwe religieuze bewegingen en New Age-centra in Nederland (1994) VU uitgeverij ISBN 90-5383-341-2

- ^ Stark, R & W.S. Bainbridge The future of religion: secularization, revival and cult formation (1985) Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California press

- ^ Joining a Cult: Religious Choice or Psychological Aberration?

Further reading

- Barker, Eileen The Making of a Moonie: Choice or Brainwashing? (1984)

- Barrett, D. V. The New Believers: A survey of sects, cults and alternative religions (2001) UK, Cassell & Co ISBN 0-304-35592-5

- Cooper, Richard S. "The Assessment and Collection of Kharaj Tax in Medieval Egypt" Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 96, No. 3. (Jul–Sep., 1976), pp. 365–382.

- Curtin, Phillip D. Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- Hoiberg, Dale, and Indu Ramachandran. Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan, 2000.

- Idris, Gaefar, Sheikh. The Process of Islamization. Plainfield, Ind.: Muslim Students' Association of the U.S. and Canada, 1977. vi, 20 p. Without ISBN

- James, William, The varieties of religious experience: a study in human nature. Being the Gifford lectures on natural religion delivered at Edinburgh in 1901-1902; Longmans, Green & Co, New York (1902)

- Morris, Harold C., and Lin M. Morris. "Power and purpose: Correlates to conversion." Psychology: A Journal of Human Behavior, Vol 15(4), Nov-Dec 1978, 15–22.

- Rambo, Lewis R. Understanding Religious Conversion. Yale University Press, 1993.

- Ramstedt, Martin. Hinduism in Modern Indonesia: A Minority Religion Between Local, National, and Global Interests. Routledge, 2004.

- Rawat, Ajay S. StudentMan and Forests: The Khatta and Gujjar Settlements of Sub-Himalayan Tarai. Indus Publishing, 1993.

- Vasu, Srisa Chandra (1919), The Catechism Of Hindu Dharma, New York: Kessinger Publishing, LLC

- Jain, Vijay K. (2011), Tattvârthsûtra (1st ed.), (Uttarakhand) India: Vikalp Printers, ISBN 81-903639-2-1,

Non-Copyright

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Aspects of Jaina religion (3rd ed.), Bharatiya Jnanpith, ISBN 81-263-0626-2

External links

- "Conversion: A Family Affair", Craig Harline, Berfrois, 4 October 2011