User:WilliamWang002/sandbox

| This is a user sandbox of WilliamWang002. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

This article documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (June 2020) |

Management of COVID-19 includes supportive care, which may include fluid therapy, oxygen support, and supporting other affected vital organs.[1][2][3] The WHO is in the process of including dexamethasone in guidelines for treatment for hospitalized patients, and it is recommended for consideration in Australian guidelines for patients requiring oxygen.[4][5] CDC recommends those who suspect they carry the virus wear a simple face mask.[6] Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been used to address the issue of respiratory failure, but its benefits are still under consideration.[7][8] Personal hygiene and a healthy lifestyle and diet have been recommended to improve immunity.[9] Supportive treatments may be useful in those with mild symptoms at the early stage of infection.[10]

The WHO, the Chinese National Health Commission, and the United States' National Institutes of Health have published recommendations for taking care of people who are hospitalised with COVID‑19.[11][12][13] Intensivists and pulmonologists in the U.S. have compiled treatment recommendations from various agencies into a free resource, the IBCC.[14][15]

Medications

[edit]Numerous candidate medications are under investigation, however Dexamethasone and Remdesivir are the only medications with proven clinical benefit in randomized controlled trials. [16]

Dexamethasone

[edit]Dexamethasone may be used for patients requiring supplemental oxygen only. The recommended dose as per Australian guidelines, as of July 2020, is 6mg daily, oral or intravenous, for up to ten days, as per the Recovery trial. [17] The WHO is in the process of including dexamethasone in guidelines for treatment for hospitalized patients.[4]

Remdesivir

[edit]Remdesivir has been approved by the Australian TGA, as the most promising treatment to reduce hospitalization time,[18] and is included for consideration in Australian treatment guidelines.[5] The suggested dose as of July 2020 is a 200 mg initial dose, with 100 mg daily maintenance, for 10 days, intravenously.[5] On 1 May 2020, the United States gave emergency use authorization (not full approval) for remdesivir in people hospitalized with severe COVID‑19 after a study suggested it reduced the duration of recovery.[19][20]

For symptoms

[edit]For symptoms, some medical professionals recommend paracetamol (acetaminophen) over ibuprofen for first-line use.[21][22][23] The WHO and NIH do not oppose the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen for symptoms,[11][24] and the FDA says currently there is no evidence that NSAIDs worsen COVID‑19 symptoms.[25]

While theoretical concerns have been raised about ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers, as of 19 March 2020, these are not sufficient to justify stopping these medications.[11][26][27][28] One study from 22 April found that people with COVID‑19 and hypertension had lower all-cause mortality when on these medications.[29]

Other disease modifying treatments

[edit]The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy recommends that tocilizumab be considered an off-label treatment option for those with COVID‑19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome. It recommends this because of its known benefit in cytokine storm caused by a specific cancer treatment, and that cytokine storm may be a significant contributor to mortality in severe COVID‑19.[30]

Other disease modifying treatments under investigation but not recommended for use based on evidence as per July 2020 include Baloxavir marboxil, Favipiravir, Lopinavir/ritonavir, Ruxolitinib, Chloroquine, Hydroxychloroquine, convalescent plasma, Interferon β-1a and colchicine. [31]

Medications to prevent blood clotting have been suggested for treatment,[32] and anticoagulant therapy with low molecular weight heparin appears to be associated with better outcomes in severe COVID‐19 showing signs of coagulopathy (elevated D-dimer).[33]

Protective equipment

[edit]

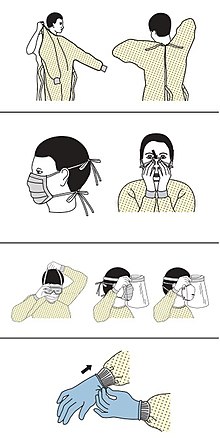

Precautions must be taken to minimise the risk of virus transmission, especially in healthcare settings when performing procedures that can generate aerosols, such as intubation or hand ventilation.[35] For healthcare professionals caring for people with COVID‑19, the CDC recommends placing the person in an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) in addition to using standard precautions, contact precautions, and airborne precautions.[36]

The CDC outlines the guidelines for the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) during the pandemic. The recommended gear is a PPE gown, respirator or facemask, eye protection, and medical gloves.[37][38]

When available, respirators (instead of face masks) are preferred.[39] CDC recommends that people have to wear a mask as a means to protect other people and yourself when they are in public places or when there are other people who do not live with you, especially when it is difficult to keep other social distance methods.[40] N95 respirators are approved for industrial settings but the FDA has authorised the masks for use under an emergency use authorization (EUA). They are designed to protect from airborne particles like dust but effectiveness against a specific biological agent is not guaranteed for off-label uses.[41] When masks are not available, the CDC recommends using face shields or, as a last resort, homemade masks.[42]

Mechanical ventilation

[edit]Most cases of COVID‑19 are not severe enough to require mechanical ventilation or alternatives, but a percentage of cases are.[43][44] The type of respiratory support for individuals with COVID‑19 related respiratory failure is being actively studied for people in the hospital, with some evidence that intubation can be avoided with a high flow nasal cannula or bi-level positive airway pressure.[45] Whether either of these two leads to the same benefit for people who are critically ill is not known.[46] Some doctors prefer staying with invasive mechanical ventilation when available because this technique limits the spread of aerosol particles compared to a high flow nasal cannula.[43]

Mechanical ventilation had been performed in 79% of critically ill people in hospital including 62% who previously received other treatment. Of these 41% died, according to one study in the United States.[47]

Severe cases are most common in older adults (those older than 60 years,[43] and especially those older than 80 years).[48] Many developed countries do not have enough hospital beds per capita, which limits a health system's capacity to handle a sudden spike in the number of COVID‑19 cases severe enough to require hospitalisation.[49] This limited capacity is a significant driver behind calls to flatten the curve.[49] One study in China found 5% were admitted to intensive care units, 2.3% needed mechanical support of ventilation, and 1.4% died.[7] In China, approximately 30% of people in hospital with COVID‑19 are eventually admitted to ICU.[50]

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

[edit]Mechanical ventilation becomes more complex as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) develops in COVID‑19 and oxygenation becomes increasingly difficult.[51] Ventilators capable of pressure control modes and high PEEP[52] are needed to maximise oxygen delivery while minimising the risk of ventilator-associated lung injury and pneumothorax.[53] High PEEP may not be available on older ventilators.[citation needed]

| Therapy | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| High-flow nasal oxygen | For SpO2 <93%. May prevent the need for intubation and ventilation |

| Tidal volume | 6mL per kg and can be reduced to 4mL/kg |

| Plateau airway pressure | Keep below 30 cmH2O if possible (high respiratory rate (35 per minute) may be required) |

| Positive end-expiratory pressure | Moderate to high levels |

| Prone positioning | For worsening oxygenation |

| Fluid management | Goal is a negative balance of 0.5–1.0L per day |

| Antibiotics | For secondary bacterial infections |

| Glucocorticoids | Not recommended |

Experimental treatment

[edit]Antiviral medications

[edit]Research into potential treatments started in January 2020,[54] and several antiviral drugs are in clinical trials.[55][56] Remdesivir appears to be the most promising.[57] Although new medications may take until 2021 to develop,[58] several of the medications being tested are already approved for other uses or are already in advanced testing.[59] Antiviral medication may be tried in people with severe disease.[1] The WHO recommended volunteers take part in trials of the effectiveness and safety of potential treatments.[60]

Convalescent plasma

[edit]Convalescent plasma is plasma from the blood of people who have recovered from COVID-19 that contains COVID-19 antibodies.[61] The FDA has granted temporary authorisation to convalescent plasma as an experimental treatment in cases where the person's life is seriously or immediately threatened.[62] Convalescent plasma treatment has not undergone the randomized controlled or non-randomized clinical studies needed to determine if is safe and effective for treating people with COVID-19.[61][63][64]

Information technology

[edit]In February 2020, China launched a mobile app to deal with the disease outbreak.[65] Users are asked to enter their name and ID number. The app can detect 'close contact' using surveillance data and therefore a potential risk of infection. Every user can also check the status of three other users. If a potential risk is detected, the app not only recommends self-quarantine, it also alerts local health officials.[66]

Big data analytics on cellphone data, facial recognition technology, mobile phone tracking, and artificial intelligence are used to track infected people and people whom they contacted in South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore.[67][68] In March 2020, the Israeli government enabled security agencies to track mobile phone data of people supposed to have coronavirus. According to the Israeli government, the measure was taken to enforce quarantine and protect those who may come into contact with infected citizens. The Association for Civil Rights in Israel, however, said the move was "a dangerous precedent and a slippery slope".[69] Also in March 2020, Deutsche Telekom shared aggregated phone location data with the German federal government agency, Robert Koch Institute, to research and prevent the spread of the virus.[70] Russia deployed facial recognition technology to detect quarantine breakers.[71] Italian regional health commissioner Giulio Gallera said he has been informed by mobile phone operators that "40% of people are continuing to move around anyway".[72] The German Government conducted a 48-hour weekend hackathon, which had more than 42,000 participants.[73][74] Three million people in the UK used an app developed by King's College London and Zoe to track people with COVID‑19 symptoms.[75][76] The president of Estonia, Kersti Kaljulaid, made a global call for creative solutions against the spread of coronavirus.[77]

Psychological support

[edit]Individuals may experience distress from quarantine, travel restrictions, side effects of treatment, or fear of the infection itself. To address these concerns, the National Health Commission of China published a national guideline for psychological crisis intervention on 27 January 2020.[78][79]

The Lancet published a 14-page call for action focusing on the UK and stated conditions were such that a range of mental health issues was likely to become more common. BBC quoted Rory O'Connor in saying, "Increased social isolation, loneliness, health anxiety, stress, and an economic downturn are a perfect storm to harm people's mental health and wellbeing."[80][81]

Management in Dental Settings

[edit]The characteristics of dental settings may give rise to the risk of cross‑infection for both patients and dentists. The virus can be transmitted in clinical settings through inhalation of airborne microorganisms that can remain suspended in the air for long periods and also due to contact with blood, oral fluids, conjunctival, nasal, oral mucosa with droplets, and other patient materials. To contain the infection, dentists have been advised to stop all elective procedures and only treat patients requiring emergency care. Make sure the Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) being used is appropriate for the procedures being performed, At the completion of work activities, countertops and surfaces that may have become contaminated with blood or saliva should be decontaminated. Virus can persist on inanimate surfaces such as metal, glass, and plastic and can be inactivated by surface disinfection procedures using 62%–71% ethanol, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide, or 0.1% sodium hypochlorite within 1 min.[82]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Fisher D, Heymann D (February 2020). "Q&A: The novel coronavirus outbreak causing COVID-19". BMC Medicine. 18 (1): 57. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-01533-w. PMC 7047369. PMID 32106852.

- ^ Liu K, Fang YY, Deng Y, Liu W, Wang MF, Ma JP, et al. (May 2020). "Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province". Chinese Medical Journal. 133 (9): 1025–1031. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. PMC 7147277. PMID 32044814.

- ^ Wang T, Du Z, Zhu F, Cao Z, An Y, Gao Y, Jiang B (March 2020). "Comorbidities and multi-organ injuries in the treatment of COVID-19". Lancet. 395 (10228). Elsevier BV: e52. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30558-4. PMID 32171074.

- ^ a b "Q&A: Dexamethasone and COVID-19". www.who.int. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- ^ a b c "Home". National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (5 April 2020). "What to Do if You Are Sick". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ a b Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. (April 2020). "Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (18). Massachusetts Medical Society: 1708–1720. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2002032. PMC 7092819. PMID 32109013.

- ^ Henry BM (April 2020). "COVID-19, ECMO, and lymphopenia: a word of caution". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 8 (4). Elsevier BV: e24. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30119-3. PMC 7118650. PMID 32178774.

- ^ Wang L, Wang Y, Ye D, Liu Q (March 2020). "Review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) based on current evidence". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents: 105948. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105948. PMC 7156162. PMID 32201353. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Qin Q (March 2020). "Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures". Journal of Medical Virology. n/a (n/a): 568–576. doi:10.1002/jmv.25748. PMC 7228347. PMID 32134116.

- ^ a b c "COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines". www.nih.gov. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ Cheng ZJ, Shan J (April 2020). "2019 Novel coronavirus: where we are and what we know". Infection. 48 (2): 155–163. doi:10.1007/s15010-020-01401-y. PMC 7095345. PMID 32072569.

- ^ "Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ Farkas J (March 2020). COVID-19—The Internet Book of Critical Care (digital) (Reference manual). USA: EMCrit. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ "COVID19—Resources for Health Care Professionals". Penn Libraries. 11 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Australian guidelines for the clinical care of people with COVID-19. National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce https://app.magicapp.org/#/guideline/L4Q5An/section/L0OPkj.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Australian guidelines for the clinical care of people with COVID-19. National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce https://app.magicapp.org/#/guideline/L4Q5An/section/L0OPkj.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Administration, Australian Government Department of Health Therapeutic Goods (2020-07-10). "Australia's first COVID treatment approved". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- ^ "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Issues Emergency Use Authorization for Potential COVID-19 Treatment". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 1 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions on the Emergency Use Authorization for Remdesivir for Certain Hospitalized COVID‐19 Patients" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Day M (March 2020). "Covid-19: ibuprofen should not be used for managing symptoms, say doctors and scientists". BMJ. 368: m1086. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1086. PMID 32184201. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Self-isolation advice—Coronavirus (COVID-19)". National Health Service (United Kingdom). 28 February 2020. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Godoy M (18 March 2020). "Concerned About Taking Ibuprofen For Coronavirus Symptoms? Here's What Experts Say". NPR. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ AFP (19 March 2020). "Updated: WHO Now Doesn't Recommend Avoiding Ibuprofen For COVID-19 Symptoms". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and (19 March 2020). "FDA advises patients on use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for COVID-19". Drug Safety and Availability. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ "Patients taking ACE-i and ARBs who contract COVID-19 should continue treatment, unless otherwise advised by their physician". Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Patients taking ACE-i and ARBs who contract COVID-19 should continue treatment, unless otherwise advised by their physician". American Heart Association (Press release). 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ de Simone G. "Position Statement of the ESC Council on Hypertension on ACE-Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers". Council on Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ "New Evidence Concerning Safety of ACE Inhibitors, ARBs in COVID-19". Pharmacy Times. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ Grainger S. "ASCIA Position Statement: Specific Treatments for COVID-19". Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ https://covid19evidence.net.au/.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:4was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z (May 2020). "Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 18 (5): 1094–1099. doi:10.1111/jth.14817. PMID 32220112.

- ^ "Sequence for Putting On Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Cheung JC, Ho LT, Cheng JV, Cham EY, Lam KN (April 2020). "Staff safety during emergency airway management for COVID-19 in Hong Kong". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 8 (4): e19. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30084-9. PMC 7128208. PMID 32105633.

- ^ "What healthcare personnel should know about caring for patients with confirmed or possible coronavirus disease 2" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 12 March 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Healthcare Settings". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ CDC (2020-02-11). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Frequently Asked Questions". Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ "Strategies for Optimizing the Supply of Facemasks". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Murthy S, Gomersall CD, Fowler RA (March 2020). "Care for Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19". JAMA. 323 (15): 1499. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3633. PMID 32159735. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization (28 January 2020). "Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Wang K, Zhao W, Li J, Shu W, Duan J (March 2020). "The experience of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in two hospitals of Chongqing, China". Annals of Intensive Care. 10 (1): 37. doi:10.1186/s13613-020-00653-z. PMC 7104710. PMID 32232685.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ McEnery T, Gough C, Costello RW (April 2020). "COVID-19: Respiratory support outside the intensive care unit". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30176-4. PMC 7146718. PMID 32278367.

- ^ Cummings, Matthew J.; Baldwin, Matthew R.; Abrams, Darryl; Jacobson, Samuel D.; Meyer, Benjamin J.; Balough, Elizabeth M.; Aaron, Justin G.; Claassen, Jan; Rabbani, LeRoy E.; Hastie, Jonathan; Hochman, Beth R. (19 May 2020). "Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study". The Lancet. 0. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7237188. PMID 32442528.

- ^ Ferguson NM, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilani G, Imai N, Ainslie K, Baguelin M (16 March 2020). Report 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand (Report). Imperial College London. Table 1. doi:10.25561/77482. hdl:20.1000/100. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ a b Scott, Dylan (16 March 2020). "Coronavirus is exposing all of the weaknesses in the US health system High health care costs and low medical capacity made the US uniquely vulnerable to the coronavirus". Vox. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|name-list-format=(help) - ^ "Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 6 April 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b Matthay MA, Aldrich JM, Gotts JE (May 2020). "Treatment for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome from COVID-19". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 8 (5): 433–434. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30127-2. PMC 7118607. PMID 32203709.

- ^ Briel M, Meade M, Mercat A, Brower RG, Talmor D, Walter SD, et al. (March 2010). "Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA. 303 (9): 865–73. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.218. PMID 20197533.

- ^ Diaz R, Heller D (2020). Barotrauma And Mechanical Ventilation. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31424810.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Chinese doctors using plasma therapy on coronavirus, WHO says 'very valid' approach". Reuters. 17 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ Steenhuysen J, Kelland K (24 January 2020). "With Wuhan virus genetic code in hand, scientists begin work on a vaccine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Duddu P (19 February 2020). "Coronavirus outbreak: Vaccines/drugs in the pipeline for Covid-19". clinicaltrialsarena.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020.

- ^ Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB (April 2020). "Pharmacologic Treatments for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review". JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6019. PMID 32282022.

- ^ Lu H (March 2020). "Drug treatment options for the 2019-new coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". Bioscience Trends. 14 (1): 69–71. doi:10.5582/bst.2020.01020. PMID 31996494.

- ^ Li G, De Clercq E (March 2020). "Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 19 (3): 149–150. doi:10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0. PMID 32127666.

- ^ Nebehay S, Kelland K, Liu R (5 February 2020). "WHO: 'no known effective' treatments for new coronavirus". Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ a b Piechotta, Vanessa; Chai, Khai Li; Valk, Sarah J.; Doree, Carolyn; Monsef, Ina; Wood, Erica M.; Lamikanra, Abigail; Kimber, Catherine; McQuilten, Zoe; So-Osman, Cynthia; Estcourt, Lise J. (2020-07-10). "Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin for people with COVID-19: a living systematic review". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD013600. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013600.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 32648959.

- ^ "FDA now allows treatment of life-threatening COVID-19 cases using blood from patients who have recovered". TechCrunch. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "Blood plasma taken from covid-19 survivors might help patients fight off the disease". MIT Technology Review.

- ^ "Trials of Plasma From Recovered Covid-19 Patients Have Begun". Wired.

- ^ "China launches coronavirus 'close contact' app". BBC News. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ Chen A. "China's coronavirus app could have unintended consequences". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ "Gov in the Time of Corona". GovInsider. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Manancourt V (10 March 2020). "Coronavirus tests Europe's resolve on privacy". POLITICO. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Tidy J (17 March 2020). "Coronavirus: Israel enables emergency spy powers". BBC News. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Bünte O (18 March 2020). "Corona-Krise: Deutsche Telekom liefert anonymisierte Handydaten an RKI" [Corona crisis: Deutsche Telekom delivers anonymized cell phone data to RKI]. Heise Online (in German). Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Moscow deploys facial recognition technology for coronavirus quarantine". Reuters. 21 February 2020. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Italians scolded for flouting lockdown as death toll nears 3,000". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Kreative Lösungen gesucht". Startseite (in German). Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Dannewitz J (23 March 2020). "Hackathon Germany: #WirvsVirus". Datenschutzbeauftragter (in German).

- ^ Staff (8 April 2020). "Lockdown is working, suggests latest data from symptom tracker app". Kings College London News Centre. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Lydall, Ross (4 May 2020). "Three million download app to track coronavirus symptoms". Evening Standard. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Whyte A (21 March 2020). "President makes global call to combat coronavirus via hackathon". ERR. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T, Ng CH (March 2020). "Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 7 (3): 228–229. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. PMC 7128153. PMID 32032543.

- ^ Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang BX, et al. (March 2020). "The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 7 (3): e14. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X. PMC 7129673. PMID 32035030.

- ^ Coronavirus: 'Profound' mental health impact prompts calls for urgent research, BBC, Philippa Roxby, 16 April 2020.

- ^ Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID‑19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science, The Lancet, Emily Holmes, Rory O'Connor, Hugh Perry, et al., 15 April 2020, page 1: "A fragmented research response, characterised by small-scale and localised initiatives, will not yield the clear insights necessary to guide policymakers or the public."

- ^ Pious, Neetha; Mhatre, Amol; Ingole, SumedhD (2020). "Management of Coronavirus disease 2019 in dentistry". Journal of Oral Research and Review. 12 (2): 110. doi:10.4103/jorr.jorr_13_20.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)