Furazabol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Frazalon, Miotalon, Qu Zhi Shu |

| Other names | Androfurazanol; DH-245; Furazalon; Frazalon; Pirzalon; 17α-Methyl-5α-androsta[2,3-c]furazan-17β-ol; 17β-Hydroxy-17α-methyl-5α-androstano[2,3-c]-1',2',5'-oxadiazole; 17α-Methyl-5α-androstano[2,3-c][1,2,5]oxadiazol-17β-ol |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Androgen; Anabolic steroid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 4 hours[citation needed] |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.621 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

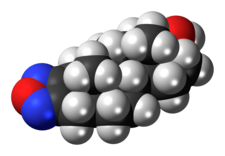

| Formula | C20H30N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 330.472 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Furazabol (INN, JAN) (brand names Frazalon, Miotalon, Qu Zhi Shu), also known as androfurazanol, is a synthetic, orally active anabolic-androgenic steroid which has been marketed in Japan since 1969.[1][2][3][4] It is a 17α-alkylated derivative of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and is closely related structurally to stanozolol, differing from it only by having a furazan ring system instead of pyrazole.[5] Furazabol has a relatively high ratio of anabolic to androgenic activity.[4] As with other 17α-alkylated AAS, it may have a risk of hepatotoxicity.[6] The drug has been described as an antihyperlipidemic and is claimed to be useful in the treatment of atherosclerosis and hypercholesterolemia,[5] but according to William Llewellyn, such properties of furazabol are a myth.[7]

Doping

[edit]Previously a relatively unknown drug to North American athletes, Furazabol gained notoriety in the Commission of Inquiry into the Use of Drugs and Banned Practices Intended to Increase Athletic Performance (known colloquially as the Dubin inquiry). After winning the 100m gold at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson tested positive for the anabolic steroid Stanozolol, was later stripped of his gold medal, and banned from competition for two years.[8] Johnson initially denied the allegations, asserting he had never taken banned substances. He later claimed the positive finding was the result of sabotage, and that he had actually taken Furazabol, which at the time could not be detected by the Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry assay used to analyze samples at the Games. Contrariwise, Stanozolol had been widely used in elite athlete circles since the 1970s, and as of 1988, could be reliably identified by conventional testing procedures.[9]

Testifying before the Dubin Inquiry, Johnson's physician George "Jamie" Astaphan claimed that he had been administering Furazabol (which he termed Estragol) to Johnson since the mid-1980s, and that Johnson likely self-administered Stanozolol within a month of the Games opening in Seoul.

In later testimony, Johnson's training mate Angella Issajenko told the Commission that she too had obtained Furazabol from Astaphan, or so she thought. The former-Canadian record holder revealed that, after Johnson's positive test, she had an analysis done on a leftover vial of what she thought contained Furazabol, and was informed it was identified as Stanozolol. Issajenko, and later the Commission's Chief Justice Charles Dubin, concluded Astaphan had been peddling Stanozolol to Johnson, Issajenko, and other Canadian team members all along, and that Furazabol was either a figment of his imagination, or an outright lie.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 585–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 475–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ William Andrew Publishing (22 October 2013). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition. Elsevier. pp. 1725–. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3.

- ^ a b Progress in Medicinal Chemistry. Elsevier. 1 January 1979. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-08-086264-4.

- ^ a b Fragkaki AG, Angelis YS, Koupparis M, Tsantili-Kakoulidou A, Kokotos G, Georgakopoulos C (2009). "Structural characteristics of anabolic androgenic steroids contributing to binding to the androgen receptor and to their anabolic and androgenic activities. Applied modifications in the steroidal structure". Steroids. 74 (2): 172–97. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2008.10.016. PMID 19028512. S2CID 41356223.

- ^ Abbate V, Kicman AT, Evans-Brown M, McVeigh J, Cowan DA, Wilson C, Coles SJ, Walker CJ (2015). "Anabolic steroids detected in bodybuilding dietary supplements - a significant risk to public health". Drug Test Anal. 7 (7): 609–18. doi:10.1002/dta.1728. PMID 25284752.

- ^ William Llewellyn (2007). Anabolics 2007: Anabolic Steroids Reference Manual. Body of Science. ISBN 978-0967930466.

- ^ Mann, Andrea. "September 27, 1988: Ben Johnson is stripped of his Olympic gold medal after failing drugs test". BT. BT Group. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ Masse, Robert (1989). "Studies on anabolic steroids. III. Detection and characterization of stanozolol urinary metabolites in humans by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry". Journal of Chromatography. 497: 17–37. PMID 2625454.

- ^ Harvey, Randy (March 17, 1989). "Milky White Substance: Is It a Solution?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 24 March 2020.