Homosexuality: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by Razorweiner (talk) to last version by Realm of Shadows |

Agnaramasi (talk | contribs) or without either already means ' |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{pp-semi-protected|small=yes}} |

{{pp-semi-protected|small=yes}} |

||

{{Sexual orientation}} |

{{Sexual orientation}} |

||

'''Homosexuality''' refers to attraction |

'''Homosexuality''' refers to sexual attraction or [[human sexual behavior|sexual behavior]] between people of the same sex, or to a sexual orientation. As an [[sexual orientation|orientation]], homosexuality refers to "an enduring pattern of or disposition to experience sexual, affectional, or romantic attractions primarily to" people of the same sex; "it also refers to an individual’s sense of personal and social identity based on those attractions, behaviors expressing them, and membership in a community of others who share them."<ref name="apahelp">{{citation |url=http://www.apahelpcenter.org/articles/article.php?id=31 |title=Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality |periodical=[[American Psychological Association|APA]]HelpCenter.org |accessdate=[[2007-09-07]]}}</ref><ref name="brief">[http://www.courtinfo.ca.gov/courts/supreme/highprofile/documents/Amer_Psychological_Assn_Amicus_Curiae_Brief.pdf APA California Amicus Brief Please fix this cite<!-- Bot generated title --> and remove this comment when done.]</ref> |

||

Homosexuality is one of the three main categories of sexual orientation, along with [[bisexuality]] and [[heterosexuality]], within the [[heterosexual-homosexual continuum]]. The number of people who identify as homosexual — and the proportion of people who have [[same-sex]] sexual experiences — are difficult for researchers to estimate reliably for a variety of reasons.<ref name="levay">LeVay, Simon (1996). ''Queer Science: The Use and Abuse of Research into Homosexuality.'' Cambridge: The MIT Press ISBN 0-262-12199-9 </ref> In the modern West, major studies indicate a prevalence of 2% to 13% of the population.<ref name = ACSF1992>ACSF Investigators (1992). AIDS and sexual behaviour in France. ''Nature, 360,'' 407–409.</ref><ref name = Billy1993>Billy, J. O. G., Tanfer, K., Grady, W. R., & Klepinger, D. H. (1993). The sexual behavior of men in the United States. ''Family Planning Perspectives, 25,'' 52–60.</ref><ref name = Binson1995>Binson, D., Michaels, S., Stall, R., Coates, T. J., Gagnon, & Catania, J. A. (1995). Prevalence and social distribution of men who have sex with men: United States and its urban centers. ''Journal of Sex Research, 32,'' 245–254.</ref><ref name = Bogaert2004>Bogaert, A. F. (2004). The prevalence of male homosexuality: The effect of fraternal birth order and variation in family size. ''Journal of Theoretical Biology, 230,'' 33–37. [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6WMD-4CP12C3-2&_user=1069287&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000051273&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=1069287&md5=bf01088ebb68ca801a0a08011876fb5d] Bogaert argues that: "The prevalence of male homosexuality is debated. One widely reported early estimate was 10% (e.g., Marmor, 1980; Voeller, 1990). Some recent data provided support for this estimate (Bagley and Tremblay, 1998), but most recent large national samples suggest that the prevalence of male homosexuality in modern western societies, including the United States, is lower than this early estimate (e.g., 1–2% in Billy et al., 1993; 2–3% in Laumann et al., 1994; 6% in Sell et al., 1995; 1–3% in Wellings et al., 1994). It is of note, however, that homosexuality is defined in different ways in these studies. For example, some use same-sex behavior and not same-sex attraction as the operational definition of homosexuality (e.g., Billy et al., 1993); many sex researchers (e.g., Bailey et al., 2000; Bogaert, 2003; Money, 1988; Zucker and Bradley, 1995) now emphasize attraction over overt behavior in conceptualizing sexual orientation." (p. 33) Also: "...the prevalence of male homosexuality (in particular, same-sex attraction) varies over time and across societies (and hence is a ‘‘moving target’’) in part because of two effects: (1) variations in fertility rate or family size; and (2) the fraternal birth order effect. Thus, even if accurately measured in one country at one time, the rate of male homosexuality is subject to change and is not generalizable over time or across societies." (p. 33)</ref><ref name = Fay1989>{{cite journal |author=Fay RE, Turner CF, Klassen AD, Gagnon JH |title=Prevalence and patterns of same-gender sexual contact among men |journal=Science |volume=243 |issue=4889 |pages=338–48 |year=1989 |month=January |pmid=2911744 |url=http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=2911744}}</ref><ref name = Johnson1992>{{cite journal |author=Johnson AM, Wadsworth J, Wellings K, Bradshaw S, Field J |title=Sexual lifestyles and HIV risk |journal=Nature |volume=360 |issue=6403 |pages=410–2 |year=1992 |month=December |pmid=1448163 |doi=10.1038/360410a0 }}</ref><ref name = Laumann1994>Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). ''The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States.'' Chicago: University of Chicago Press.</ref><ref name = Sell1995>{{cite journal |author=Sell RL, Wells JA, Wypij D |title=The prevalence of homosexual behavior and attraction in the United States, the United Kingdom and France: results of national population-based samples |journal=Arch Sex Behav |volume=24 |issue=3 |pages=235–48 |year=1995 |month=June |pmid=7611844 }}</ref><ref name = Wellings1994>Wellings, K., Field, J., Johnson, A., & Wadsworth, J. (1994). ''Sexual behavior in Britain: The national survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles.'' London, UK: Penguin Books. </ref><ref name="aftenposten"> [http://www.aftenposten.no/english/local/article633160.ece Norway world leader in casual sex, Aftenposten]</ref><ref name="guardianpoll"> [http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2008/oct/26/relationships Sex uncovered poll: Homosexuality, Guardian]</ref> A 2006 study suggested that 20% of the population anonymously reported some homosexual feelings, although relatively few participants in the study identified themselves as homosexual.<ref name="McConaghy et al">McConaghy et al., 2006</ref> |

Homosexuality is one of the three main categories of sexual orientation, along with [[bisexuality]] and [[heterosexuality]], within the [[heterosexual-homosexual continuum]]. The number of people who identify as homosexual — and the proportion of people who have [[same-sex]] sexual experiences — are difficult for researchers to estimate reliably for a variety of reasons.<ref name="levay">LeVay, Simon (1996). ''Queer Science: The Use and Abuse of Research into Homosexuality.'' Cambridge: The MIT Press ISBN 0-262-12199-9 </ref> In the modern West, major studies indicate a prevalence of 2% to 13% of the population.<ref name = ACSF1992>ACSF Investigators (1992). AIDS and sexual behaviour in France. ''Nature, 360,'' 407–409.</ref><ref name = Billy1993>Billy, J. O. G., Tanfer, K., Grady, W. R., & Klepinger, D. H. (1993). The sexual behavior of men in the United States. ''Family Planning Perspectives, 25,'' 52–60.</ref><ref name = Binson1995>Binson, D., Michaels, S., Stall, R., Coates, T. J., Gagnon, & Catania, J. A. (1995). Prevalence and social distribution of men who have sex with men: United States and its urban centers. ''Journal of Sex Research, 32,'' 245–254.</ref><ref name = Bogaert2004>Bogaert, A. F. (2004). The prevalence of male homosexuality: The effect of fraternal birth order and variation in family size. ''Journal of Theoretical Biology, 230,'' 33–37. [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6WMD-4CP12C3-2&_user=1069287&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000051273&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=1069287&md5=bf01088ebb68ca801a0a08011876fb5d] Bogaert argues that: "The prevalence of male homosexuality is debated. One widely reported early estimate was 10% (e.g., Marmor, 1980; Voeller, 1990). Some recent data provided support for this estimate (Bagley and Tremblay, 1998), but most recent large national samples suggest that the prevalence of male homosexuality in modern western societies, including the United States, is lower than this early estimate (e.g., 1–2% in Billy et al., 1993; 2–3% in Laumann et al., 1994; 6% in Sell et al., 1995; 1–3% in Wellings et al., 1994). It is of note, however, that homosexuality is defined in different ways in these studies. For example, some use same-sex behavior and not same-sex attraction as the operational definition of homosexuality (e.g., Billy et al., 1993); many sex researchers (e.g., Bailey et al., 2000; Bogaert, 2003; Money, 1988; Zucker and Bradley, 1995) now emphasize attraction over overt behavior in conceptualizing sexual orientation." (p. 33) Also: "...the prevalence of male homosexuality (in particular, same-sex attraction) varies over time and across societies (and hence is a ‘‘moving target’’) in part because of two effects: (1) variations in fertility rate or family size; and (2) the fraternal birth order effect. Thus, even if accurately measured in one country at one time, the rate of male homosexuality is subject to change and is not generalizable over time or across societies." (p. 33)</ref><ref name = Fay1989>{{cite journal |author=Fay RE, Turner CF, Klassen AD, Gagnon JH |title=Prevalence and patterns of same-gender sexual contact among men |journal=Science |volume=243 |issue=4889 |pages=338–48 |year=1989 |month=January |pmid=2911744 |url=http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=2911744}}</ref><ref name = Johnson1992>{{cite journal |author=Johnson AM, Wadsworth J, Wellings K, Bradshaw S, Field J |title=Sexual lifestyles and HIV risk |journal=Nature |volume=360 |issue=6403 |pages=410–2 |year=1992 |month=December |pmid=1448163 |doi=10.1038/360410a0 }}</ref><ref name = Laumann1994>Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). ''The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States.'' Chicago: University of Chicago Press.</ref><ref name = Sell1995>{{cite journal |author=Sell RL, Wells JA, Wypij D |title=The prevalence of homosexual behavior and attraction in the United States, the United Kingdom and France: results of national population-based samples |journal=Arch Sex Behav |volume=24 |issue=3 |pages=235–48 |year=1995 |month=June |pmid=7611844 }}</ref><ref name = Wellings1994>Wellings, K., Field, J., Johnson, A., & Wadsworth, J. (1994). ''Sexual behavior in Britain: The national survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles.'' London, UK: Penguin Books. </ref><ref name="aftenposten"> [http://www.aftenposten.no/english/local/article633160.ece Norway world leader in casual sex, Aftenposten]</ref><ref name="guardianpoll"> [http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2008/oct/26/relationships Sex uncovered poll: Homosexuality, Guardian]</ref> A 2006 study suggested that 20% of the population anonymously reported some homosexual feelings, although relatively few participants in the study identified themselves as homosexual.<ref name="McConaghy et al">McConaghy et al., 2006</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:38, 10 June 2009

| Sexual orientation |

|---|

|

| Sexual orientations |

| Related terms |

| Research |

| Animals |

| Related topics |

Homosexuality refers to sexual attraction or sexual behavior between people of the same sex, or to a sexual orientation. As an orientation, homosexuality refers to "an enduring pattern of or disposition to experience sexual, affectional, or romantic attractions primarily to" people of the same sex; "it also refers to an individual’s sense of personal and social identity based on those attractions, behaviors expressing them, and membership in a community of others who share them."[1][2]

Homosexuality is one of the three main categories of sexual orientation, along with bisexuality and heterosexuality, within the heterosexual-homosexual continuum. The number of people who identify as homosexual — and the proportion of people who have same-sex sexual experiences — are difficult for researchers to estimate reliably for a variety of reasons.[3] In the modern West, major studies indicate a prevalence of 2% to 13% of the population.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14] A 2006 study suggested that 20% of the population anonymously reported some homosexual feelings, although relatively few participants in the study identified themselves as homosexual.[15]

Homosexual relationships and acts have been admired as well as condemned throughout recorded history, depending on the form they took and the culture in which they occurred. Since Stonewall riots [16], there has been a movement towards increased visibility, recognition and legal rights for homosexual people, including the rights to marriage and civil unions, adoption and parenting, employment, military service, and equal access to health care.

Etymology and usage

Attic red-figure cup from Tarquinia, 480 BC (Boston Museum of Fine Arts)

Etymologically, the word homosexual is a Greek and Latin hybrid with the first element derived from Greek homos, 'same' (NOT the unrelated Latin word homo, 'man', as in Homo sapiens), thus connoting sexual acts and affections between members of the same sex, including lesbianism.[17] Gay generally refers to male homosexuality, but is sometimes used in a broader sense to refer to all LGBT people. In the context of sexuality, lesbian denotes female homosexuality.

The adjective homosexual describes behavior, relationships, people, orientation etc. The adjectival form literally means "same sex", being a hybrid formed from Greek homo- (a form of homos "same"), and "sexual" from Medieval Latin sexualis (from Classical Latin sexus). Many modern style guides in the U.S. recommend against using homosexual as a noun, instead using gay man or lesbian.[18] Similarly, some recommend completely avoiding usage of homosexual as having a negative and discredited clinical history and because the word only refers to one's sexual behavior, and not to romantic feelings.[18] Gay and lesbian are the most common alternatives. The first letters are frequently combined to create the initialism LGBT (sometimes written as GLBT), in which B and T refer to bisexual and transgender people. These style guides are not always followed by mainstream media sources.[19]

The first known appearance of homosexual in print is found in an 1869 German pamphlet by the Austrian-born novelist Karl-Maria Kertbeny, published anonymously,[20] arguing against a Prussian anti-sodomy law.[21][22] In 1879, Gustav Jager used Kertbeny's terms in his book, Discovery of the Soul (1880).[22] In 1886, Richard von Krafft-Ebing used the terms homosexual and heterosexual in his book Psychopathia Sexualis, probably borrowing them from Jager. Krafft-Ebing's book was so popular among both layman and doctors that the terms "heterosexual" and "homosexual" became the most widely accepted terms for sexual orientation.[22][23]

As such, the current use of the term has its roots in the broader 19th-century tradition of personality taxonomy. These continue to influence the development of the modern concept of sexual orientation, gaining associations with romantic love and identity in addition to its original, exclusively sexual, meaning.

Although early writers also used the adjective homosexual to refer to any single-sex context (such as an all-girls' school), today the term is used exclusively in reference to sexual attraction, activity, and orientation. The term homosocial is now used to describe single-sex contexts that are not specifically sexual. There is also a word referring to same-sex love, homophilia. Other terms include men who have sex with men or MSM (used in the medical community when specifically discussing sexual activity), homoerotic (referring to works of art), heteroflexible (referring to a person who identifies as heterosexual, but occasionally engages in same-sex sexual activities), and metrosexual (referring to a non-gay man with stereotypically gay tastes in food, fashion, and design). Pejorative terms in English include queer, faggot, fairy, poof, and homo. Beginning in the 1990s, some of these have been reclaimed as positive words by gay men and lesbians, as in the usage of queer studies, queer theory, and even the popular American television program Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. The word homo occurs in many other languages without the pejorative connotations it has in English.[24] As with ethnic slurs and racial slurs, however, the misuse of these terms can still be highly offensive; the range of acceptable use depends on the context and speaker. Conversely, gay, a word originally embraced by homosexual men and women as a positive, affirmative term (as in gay liberation and gay rights), has come into widespread pejorative use among young people.

Sexuality and gender identity

Sexual orientation, identity, behaviour

The American Psychological Association states that sexual orientation "describes the pattern of sexual attraction, behavior and identity e.g. homosexual (aka gay, lesbian), bisexual and heterosexual (aka straight)." "Sexual attraction, behavior and identity may be incongruent. For example, sexual attraction and/or behavior may not necessarily be consistent with identity. Some individuals may identify themselves as homosexual or bisexual without having had any sexual experience. Others have had homosexual experiences but do not consider themselves to be gay, lesbian, or bisexual. Further, sexual orientation falls along a continuum. In other words, someone does not have to be exclusively homosexual or heterosexual, but can feel varying degrees of both. Sexual orientation develops across a person's lifetime — different people realize at different points in their lives that they are heterosexual, bisexual or homosexual."[25]

People with a homosexual orientation who do not identify as gay or lesbian are often referred to as closeted.

Homosexual activity can also occur in situations where large groups of persons of the same sex are confined together for some length of time, as in prison, the military, single-sex boarding schools, or other sex-segregated communities, where members of those communities might engage in homosexual behaviors but otherwise identify as heterosexual.

Sexual identity development: "coming-out process"

Many people who feel attracted to members of their own sex have a so-called "coming out" at some point in their lives. Generally, coming out is described in three phases. The first phase is the phase of "knowing oneself," and the realization or decision emerges that one is open to same-sex relations. This is often described as an internal coming out. The second phase involves one's decision to come out to others, e.g. family, friends, and/or colleagues. This occurs with many people as early as age 11, but others do not clarify their sexual orientation until age 40 or older. The third phase more generally involves living openly as an LGBT person.[26] In the United States today, people often come out during high school or college age. At this age, they may not trust or ask for help from others, especially when their orientation is not accepted in society. Sometimes their own parents are not even informed.

According to Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, Braun (2006), "the development of a lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) sexual identity is a complex and often difficult process. Unlike members of other minority groups (e.g., ethnic and racial minorities), most LGB individuals are not raised in a community of similar others from whom they learn about their identity and who reinforce and support that identity. Rather, LGB individuals are often raised in communities that are either ignorant of or openly hostile toward homosexuality."[27]

Outing is the practice of publicly revealing the sexual orientation of a closeted person.[28] Notable politicians, celebrities, military service people, and clergy members have been outed, with motives ranging from malice to political or moral beliefs. Many commentators oppose the practice altogether,[29] while some encourage outing public figures who use their positions of influence to harm other gay people.[30]

Fluidity of sexual orientation

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has stated "some people believe that sexual orientation is innate and fixed; however, sexual orientation develops across a person’s lifetime".[31] In a joint statement with other major American medical organizations, the APA says that "different people realize at different points in their lives that they are heterosexual, gay, lesbian, or bisexual".[32] A report from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health states: "For some people, sexual orientation is continuous and fixed throughout their lives. For others, sexual orientation may be fluid and change over time".[33] One study has suggested "considerable fluidity in bisexual, unlabeled, and lesbian women's attractions, behaviors, and identities".[34][35] In a 2004 study, the female subjects (both gay and straight women) became sexually aroused when they viewed heterosexual as well as lesbian erotic films. Among the male subjects, however, the straight men were turned on only by erotic films with women, the gay ones by those with men. The study's senior researcher said that women's sexual desire is less rigidly directed toward a particular sex, as compared with men's, and it's more changeable over time.[36]

However, the APA also says that "most people experience little or no sense of choice about their sexual orientation".[37] American medical organizations have further stated therapy cannot change sexual orientation, and have expressed concerns over potential harms.[32] The director of the APA's LGBT Concerns Office explained: "I don't think that anyone disagrees with the idea that people can change because we know that straight people become gays and lesbians ... the issue is whether therapy changes sexual orientation, which is what many of these people claim".[38] The American Psychiatric Association (APA) states, in a 2000 position statement, that they oppose "any psychiatric treatment, such as "reparative" or conversion therapy, which is based upon the assumption that homosexuality per se is a mental disorder or based upon the a priori assumption that a patient should change their sexual orientation.[39] Similarly, United States Surgeon General David Satcher issued a report stating that "there is no valid scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed".[40]

Gender identity

The earliest writers on a homosexual orientation usually understood it to be intrinsically linked to the subject's own sex. For example, it was thought that a typical female-bodied person who is attracted to female-bodied persons would have masculine attributes, and vice versa.[41] This understanding was shared by most of the significant theorists of homosexuality from the mid 19th to early 20th centuries, such as Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Magnus Hirschfeld, Havelock Ellis, Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud, as well as many gender variant homosexual people themselves. However, this understanding of homosexuality as sexual inversion was disputed at the time, and through the second half of the 20th century, gender identity came to be increasingly seen as a phenomenon distinct from sexual orientation.

Transgender and cisgender people may be attracted to men, women or both, although the prevalence of different sexual orientations is quite different in these two populations (see sexual orientation of transwomen). An individual homosexual, heterosexual or bisexual person may be masculine, feminine, or androgynous, and in addition, many members and supporters of lesbian and gay communities now see the "gender-conforming heterosexual" and the "gender-nonconforming homosexual" as negative stereotypes. However, studies by J. Michael Bailey and K.J. Zucker have found that a majority of gay men and lesbians report being gender-nonconforming during their childhood years.[42] Richard C. Friedman, in Male Homosexuality published in 1990,[43] writing from a psychoanalytic perspective, argues that sexual desire begins later than the writings of Sigmund Freud indicate, not in infancy but between the ages of 5 and 10 and is not focused on a parent figure but on peers. As a consequence, he reasons, male homosexuals are not abnormal, never having been sexually attracted to their mothers anyway.[44]

Social construct

Because a homosexual orientation is complex and multi-dimensional, some academics and researchers, especially in Queer studies, have argued that it is a historical and social construction. In 1976 the historian Michel Foucault argued that homosexuality as an identity did not exist in the eighteenth century; that people instead spoke of "sodomy", which referred to sexual acts. Sodomy was a crime that was often ignored but sometimes punished severely (see sodomy law).

The term homosexual is often used in European and American cultures to encompass a person’s entire social identity, which includes self and personality. In Western cultures some people speak meaningfully of gay, lesbian, and bisexual identities and communities. In other cultures, homosexuality and heterosexual labels don’t emphasize an entire social identity or indicate community affiliation based on sexual orientation.[45] Some scholars, such as David Green, state that homosexuality is a modern Western social construct, and as such cannot be used in the context of non-Western male-male sexuality, nor in the pre-modern West.[46]

Forms of relationships

People with a homosexual orientation can express their sexuality in a variety of ways, and may or may not express it in their behaviors.[47] Some have sexual relationships predominately with people of their own gender identity, another gender, bisexual relationships or they can be celibate.[47] Research indicates that many lesbians and gay men want, and succeed in having, committed and durable relationships. For example, survey data indicate that between 40% and 60% of gay men and between 45% and 80% of lesbians are currently involved in a romantic relationships.[48] Survey data also indicates that between 18% and 28% of gay couples and between 8% and 21% of lesbian couples in the U.S. have lived together ten or more years.[49] Studies have found same-sex and opposite-sex couples to be equivalent to each other in measures of relationship satisfaction and commitment.[50]

Gay and lesbian people can have sexual relationships with someone of the opposite sex for a variety of reasons including the desire for family with children and concerns of discrimination and religious ostracism.[51][52][53][54][55] A mixed-orientation marriage is when one partner is non-heterosexual.[56][57] While some hide their orientation from their spouse, others develop a positive gay or lesbian identity while maintaining a successful marriage.[58][59][60] Coming out of the closet to oneself, a spouse and children can present unique challenges compared to gays and lesbians who are not married or do not have children.

Demographics

Reliable data as to the size of the gay and lesbian population is of value in informing public policy.[61] For example, demographics would help in calculating the costs and benefits of domestic partnership benefits, of the impact of legalizing gay adoption, and of the impact of the U.S. military's Don't Ask Don't Tell policy.[61] Further, knowledge of the size of the "gay and lesbian population holds promise for helping social scientists understand a wide array of important questions—questions about the general nature of labor market choices, accumulation of human capital, specialization within households, discrimination, and decisions about geographic location."[61]

Measuring the prevalence of homosexuality may present difficulties. The research must measure some characteristic that may or may not be defining of sexual orientation. The class of people with same-sex desires may be larger than the class of people who act on those desires, which in turn may be larger than the class of people who self-identify as gay/lesbian/bisexual.[61] Studies to determine the proportion of individuals who have had a homosexual experience may misleadingly overstate the prevalence of homosexuality (as not all those who have had homosexual experiences necessarily have a homosexual preference) or understate it (as not all those with a predominantly homosexual orientation are necessarily sexually active or have physically acted on it).[citation needed]

In 1948 and 1953, Alfred Kinsey reported that nearly 46% of the male subjects had "reacted" sexually to persons of both sexes in the course of their adult lives, and 37% had had at least one homosexual experience.[62] Kinsey's methodology was criticized.[63][64] A later study tried to eliminate the sample bias, but still reached similar conclusions.[65]

Estimates of the occurrence of exclusive homosexuality range from >1% to 10% of the population, usually finding there are slightly more gay men than lesbians.[66][67][68]

Estimates of the frequency of homosexual activity also vary from one country to another. A 1992 study reported that 6.1% of males in Britain had had a homosexual experience, while in France the number was 4.1%.[69] According to a 2003 survey, 12% of Norwegians have had homosexual sex.[13] In New Zealand, a 2006 study suggested that 20% of the population anonymously reported some homosexual feelings, few of them identifying as homosexual. Percentage of persons identifying homosexual was 2–3%.[15] According to a 2008 poll, while only 6% of Britons define their sexual orientation as homosexual or bisexual, more than twice that number (13%) of Britons have had some form of sexual contact with someone of the same sex.[14]

In the United States, according to exit polling on 2008 Election Day for the 2008 Presidential elections, 4% of electorate self-identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, the same percentage as in 2004.”[70]

Psychology

Psychology was one of the first disciplines to study a homosexual orientation as a discrete phenomenon. The first attempts to classify homosexuality as a disease were made by the fledgling European sexologist movement in the late 19th century. In 1886 noted sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing listed homosexuality along with 200 other case studies of deviant sexual practices in his definitive work, Psychopathia Sexualis. Krafft-Ebing proposed that homosexuality was caused by either "congenital [during birth] inversion" or an "acquired inversion". In the last two decades of the 19th century, a different view began to predominate in medical and psychiatric circles, judging such behavior as indicative of a type of person with a defined and relatively stable sexual orientation. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, pathological models of homosexuality were standard.

Today, according to American Psychological Association:

Psychologists, psychiatrists, and other mental health professionals agree that homosexuality is not an illness, a mental disorder, or an emotional problem. More than 35 years of objective, well-designed scientific research has shown that homosexuality, in and itself, is not associated with mental disorders or emotional or social problems. Homosexuality was once thought to be a mental illness because mental health professionals and society had biased information.

In the past, the studies of gay, lesbian, and bisexual people involved only those in therapy, thus biasing the resulting conclusions. When researchers examined data about such people who were not in therapy, the idea that homosexuality was a mental illness was quickly found to be untrue.

In 1973 the American Psychiatric Association confirmed the importance of the new, better-designed research and removed homosexuality from the official manual that lists mental and emotional disorders. Two years later, the American Psychological Association passed a resolution supporting this removal.[1][71][72]

The World Health Organization's ICD-9 (1977) listed homosexuality as a mental illness; it was removed from the ICD-10, endorsed by the Forty-third World Health Assembly on May 17, 1990.[73] Like the DSM-II, the ICD-10 added ego-dystonic sexual orientation to the list, which refers to people who want to change their gender identities or sexual orientation because of a psychological or behavioral disorder (F66.1).

Most lesbian, gay, and bisexual people who seek psychotherapy do so for the same reasons as heterosexuals (stress, relationship difficulties, difficulty adjusting to social or work situations, etc.); their sexual orientation may be of primary, incidental, or no importance to their issues and treatment. Whatever the issue, there is a high risk for anti-gay bias in psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients.[74] Psychological research in this area has been relevant to counteracting prejudicial ("homophobic") attitudes and actions, and to the LGBT rights movement generally.[75]

Etiology

There is no consensus among scientists about the exact reasons that an individual develops a heterosexual, bisexual, gay, or lesbian orientation.[76] The main reasons cited include genetic and environmental factors, likely in combination.[77][78] Other factors that may play a role include prenatal hormone exposure, where hormones play a role in determining sexual orientation as they do with sex differentiation;[79][80] and prenatal stress on the mother.[81][82][83]

The American Academy of Pediatrics has stated that "sexual orientation probably is not determined by any one factor but by a combination of genetic, hormonal, and environmental influences".[84] The American Psychological Association has stated that "there are probably many reasons for a person's sexual orientation and the reasons may be different for different people". It stated that, for most people, sexual orientation is determined at an early age.[85] The American Psychiatric Association has stated that, "to date there are no replicated scientific studies supporting any specific biological etiology for homosexuality. Similarly, no specific psychosocial or family dynamic cause for homosexuality has been identified, including histories of childhood sexual abuse".[31] Research into how sexual orientation may be determined by genetic or other prenatal factors plays a role in political and social debates about homosexuality, and also raises fears about genetic profiling and prenatal testing.[86]

Innate bisexuality (or predisposition to bisexuality) is a term introduced by Sigmund Freud, based on work by his associate Wilhelm Fliess, that expounds that all humans are born bisexual but through psychological development - which includes both external and internal factors - become monosexual, while the bisexuality remains in a latent state.

In a 2008 study, its authors stated that "there is considerable evidence that human sexual orientation is genetically influenced, so it is not known how homosexuality, which tends to lower reproductive success, is maintained in the population at a relatively high frequency". They hypothesized that "while genes predisposing to homosexuality reduce homosexuals' reproductive success, they may confer some advantage in heterosexuals who carry them". Their results suggested that "genes predisposing to homosexuality may confer a mating advantage in heterosexuals, which could help explain the evolution and maintenance of homosexuality in the population".[87] A 2009 study also suggested a significant increase in fecundity in the females related to the homosexual people from the maternal line (but not in those related from the paternal one).[88]

Parenting

Many LGB people are biological parents. Biological parents of some children may be both LGB [89][90][91], or LGB and heterosexual. [51][57][92][56] Fertility rate of LGB people may be above or below the average. [93][94]

At the time of conception, parents may be open [89][90][92] or closeted about their sexuality.[51][56] Some children do not know they have an LGB parent; coming out issues vary and some parents may never come out to their children.[95][96] Some LGB people also become parents through adoption and foster parenting.[citation needed] In the future, it may be possible for 2 people in a same-sex relationship to have biological children from each other thanks to stem cell research. [97]

In the 2000 U.S. Census, 33 percent of female same-sex couple households and 22 percent of male same-sex couple households reported at least one child under eighteen living in their home.[32] LGBT parenting in general, and adoption by LGBT couples in particular, are issues of ongoing political controversy in many Western countries. [citation needed] In January 2008, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that same-sex couples have the right to adopt a child.[98][99] In the U.S., LGB people can legally adopt in all states except for Florida.[100]

The American Psychological Association has stated that "there is no scientific evidence that parenting effectiveness is related to parental sexual orientation: lesbian and gay parents are as likely as heterosexual parents to provide supportive and healthy environments for their children."[32] Same-sex parenting is supported by the positions of a number of organizations, including the American Psychological Association, the Child Welfare League of America, the American Bar Association, the American Psychiatric Association, the National Association of Social Workers, the North American Council on Adoptable Children, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Psychoanalytic Association, and the American Academy of Family Physicians.[101]

Health

Physical

Avoid contact with a partner’s menstrual blood and with any visible genital lesions.

- Cover sex toys that penetrate more than one person’s vagina or anus with a new condom for each person; consider using different toys for each person.

- Use a barrier (e.g., latex sheet, dental dam, cut-open condom, plastic wrap) during oral sex.

- Use latex or vinyl gloves and lubricant for any manual sex that might cause bleeding.[102]

Avoid contact with a partner’s bodily fluids and with any visible genital lesions.

- Use condoms for anal and oral sex.

- Use a barrier (e.g., latex sheet, dental dam, cut-open condom, plastic wrap) during anal–oral sex.

- Cover sex toys that penetrate more than one person with a new condom for each person; consider using different toys for each person and use latex or vinyl gloves and lubricant for any sex that might cause bleeding.[103][104]

Men who have sex with men (MSM) and women who have sex with women (WSW) refers to people who engage in sexual activity with others of the same sex regardless of how they identify themselves as many choose not to accept social identities as lesbian, gay and bisexual.[105][106][107][108][109] These terms are often used in medical literature and social research to describe such groups for study, without needing to consider the issues of sexual self-identity. The terms are seen as problematic, however, because it "obscures social dimensions of sexuality; undermines the self-labeling of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people; and does not sufficiently describe variations in sexual behavior".[110] MSM and WSW are sexually active with each other for a variety of reasons with the main ones arguably sexual pleasure, intimacy and bonding. In contrast to its benefits, sexual behavior can be a disease vector. Safe sex is a relevant harm reduction philosophy.[111] The United States prohibits men who have sex with men from donating blood "because they are, as a group, at increased risk for HIV, hepatitis B and certain other infections that can be transmitted by transfusion."[112] Many European countries have the same prohibition.[112]

Mental

Since it was first described in medical literature, homosexuality has often been approached from a view that sought to find an inherent psychopathology as its root cause. Much literature on mental health and homosexual patients centered on their depression, substance abuse, and suicide. Although these issues exist among non-heterosexuals, discussion about their causes shifted after homosexuality was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in 1973. Instead, social ostracism, legal discrimination, internalization of negative stereotypes, and limited support structures indicate factors homosexual people face in Western societies that often adversely affect their mental health.[113] Stigma, prejudice, and discrimination stemming from negative societal attitudes toward homosexuality lead to a higher prevalence of mental health disorders among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals compared to their heterosexual peers.[114] Evidence indicates that the liberalization of these attitudes over the past few decades is associated with a decrease in such mental health risks among younger LGBT people.[115]

Gay and lesbian youth

Gay and lesbian youth bear an increased risk of suicide, substance abuse, school problems, and isolation because of a "hostile and condemning environment, verbal and physical abuse, rejection and isolation from family and peers".[116] Further, LGB youths are more likely to report psychological and physical abuse by parents or caretakers, and more sexual abuse. Suggested reasons for this disparity are that (1) LGBT youths may be specifically targeted on the basis of their perceived sexual orientation or gender non-conforming appearance, and (2) that "risk factors associated with sexual minority status, including discrimination, invisibility, and rejection by family members...may lead to an increase in behaviors that are associated with risk for victimization, such as substance abuse, sex with multiple partners, or running away from home as a teenager."[117]

Crisis centers in larger cities and information sites on the Internet have arisen to help youth and adults.[118] The Trevor Helpline, a suicide prevention helpline for gay youth, was established following the 1998 airing on HBO of the Academy Award winning short film Trevor.

History

Societal attitudes towards same-sex relationships have varied over time and place, from expecting all males to engage in same-sex relationships, to casual integration, through acceptance, to seeing the practice as a minor sin, repressing it through law enforcement and judicial mechanisms, and to proscribing it under penalty of death.

In a detailed compilation of historical and ethnographic materials of Preindustrial Cultures, "strong disapproval of homosexuality was reported for 41% of 42 cultures; it was accepted or ignored by 21%, and 12% reported no such concept. Of 70 ethnographies, 59% reported homosexuality absent or rare in frequency and 41% reported it present or not uncommon." [119]

In cultures influenced by Abrahamic religions, the law and the church established sodomy as a transgression against divine law or a crime against nature. The condemnation of anal sex between males, however, predates Christian belief. It was frequent in ancient Greece; "unnatural" can be traced back to Plato.[120]

Many historical figures, including Socrates, Lord Byron, Edward II, and Hadrian[121], have had terms such as gay or bisexual applied to them; some scholars, such as Michel Foucault, have regarded this as risking the anachronistic introduction of a contemporary construction of sexuality foreign to their times,[122] though others challenge this.[123]

A common thread of constructionist argument is that no one in antiquity or the Middle Ages experienced homosexuality as an exclusive, permanent, or defining mode of sexuality. John Boswell has countered this argument by citing ancient Greek writings by Plato,[124] which describe individuals exhibiting exclusive homosexuality.

Africa

Though often ignored or suppressed by European explorers and colonialists, homosexual expression in native Africa was also present and took a variety of forms. Anthropologists Stephen Murray and Will Roscoe reported that women in Lesotho engaged in socially sanctioned "long term, erotic relationships" called motsoalle.[125] E. E. Evans-Pritchard also recorded that male Azande warriors in the northern Congo routinely took on young male lovers between the ages of twelve and twenty, who helped with household tasks and participated in intercrural sex with their older husbands. The practice had died out by the early 20th century, after Europeans had gained control of African countries, but was recounted to Evans-Pritchard by the elders to whom he spoke.[126]

The first recorded homosexual couple in history is commonly regarded as Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum, an Egyptian male couple, who lived around the 2400 BCE. The pair are portrayed in a nose-kissing position, the most intimate pose in Egyptian art, surrounded by what appear to be their heirs.

Americas

Sac and Fox Nation ceremonial dance to celebrate the two-spirit person. George Catlin (1796-1872); Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

Among indigenous peoples of the Americas prior to European colonization, a common form of same-sex sexuality centered around the figure of the Two-Spirit individual. Typically this individual was recognized early in life, given a choice by the parents to follow the path and, if the child accepted the role, raised in the appropriate manner, learning the customs of the gender it had chosen. Two-Spirit individuals were commonly shamans and were revered as having powers beyond those of ordinary shamans. Their sexual life was with the ordinary tribe members of the same sex.

Homosexual and transgender individuals were also common among other pre-conquest civilizations in Latin America, such as the Aztecs, Mayans, Quechuas, Moches, Zapotecs, and the Tupinambá of Brazil.[127][128]

The Spanish conquerors were horrified to discover sodomy openly practiced among native peoples, and attempted to crush it out by subjecting the berdaches (as the Spanish called them) under their rule to severe penalties, including public execution, burning and being torn to pieces by dogs.[129]

East Asia

In East Asia, same-sex love has been referred to since the earliest recorded history. Early European travelers were taken aback by its widespread acceptance and open display.[citation needed]

Homosexuality in China, known as the pleasures of the bitten peach, the cut sleeve, or the southern custom, has been recorded since approximately 600 BCE. These euphemistic terms were used to describe behaviors, not identities (recently some fashionable young Chinese tend to euphemistically use the term "brokeback," 斷背 duanbei to refer to male homosexuals, from the success of director Ang Lee's film Brokeback Mountain).[130] The relationships were marked by differences in age and social position. However, the instances of same-sex affection and sexual interactions described in the classical novel Dream of the Red Chamber seem as familiar to observers in the present as do equivalent stories of romances between heterosexuals during the same period.

This same-sex love culture gave rise to strong traditions of painting and literature documenting and celebrating such relationships.[citation needed]

Similarly, in Thailand, Kathoey, or "ladyboys," have been a feature of Thai society for many centuries, and Thai kings had male as well as female lovers. While Kathoey may encompass simple effeminacy or transvestism, it most commonly is treated in Thai culture as a third gender. They are generally accepted by society, and Thailand has never had legal prohibitions against homosexuality or homosexual behavior.

Europe

The earliest Western documents (in the form of literary works, art objects, and mythographic materials) concerning same-sex relationships are derived from ancient Greece. They depict a world in which relationships with women and relationships with youths were the essential foundation of a normal man's love life. Same-sex relationships were a social institution variously constructed over time and from one city to another. The formal practice, an erotic yet often restrained relationship between a free adult male and a free adolescent, was valued for its pedagogic benefits and as a means of population control, though occasionally blamed for causing disorder. Plato praised its benefits in his early writings[131] but in his late works proposed its prohibition.[132]

In Ancient Rome the situation was reversed. Though the young male body remained a focus of male sexual attention, free boys were off limits as sexual partners. All the emperors with the exception of Claudius took male lovers. The Hellenophile emperor Hadrian is renowned for his relationship with Antinous, but the Christian emperor Theodosius I decreed a law on August 6, 390, condemning passive males to be burned at the stake. Justinian, towards the end of his reign, expanded the proscription to the active partner as well (in 558), warning that such conduct can lead to the destruction of cities through the "wrath of God". Notwithstanding these regulations, taxes on brothels of boys available for homosexual sex continued to be collected until the end of the reign of Anastasius I in 518.

During the Renaissance, wealthy cities in northern Italy—Florence and Venice in particular—were renowned for their widespread practice of same-sex love, engaged in by a considerable part of the male population and constructed along the classical pattern of Greece and Rome.[133][134] But even as many of the male population were engaging in same-sex relationships, the authorities, under the aegis of the Officers of the Night court, were prosecuting, fining, and imprisoning a good portion of that population. The eclipse of this period of relative artistic and erotic freedom was precipitated by the rise to power of the moralizing monk Girolamo Savonarola. In northern Europe the artistic discourse on sodomy was turned against its proponents by artists such as Rembrandt, who in his Rape of Ganymede no longer depicted Ganymede as a willing youth, but as a squalling baby attacked by a rapacious bird of prey.

The relationships of socially prominent figures, such as King James I and the Duke of Buckingham, served to highlight the issue, including in anonymously authored street pamphlets: "The world is chang'd I know not how, For men Kiss Men, not Women now;...Of J. the First and Buckingham: He, true it is, his Wives Embraces fled, To slabber his lov'd Ganimede;" (Mundus Foppensis, or The Fop Display'd, 1691.)

Love Letters Between a Certain Late Nobleman and the Famous Mr. Wilson was published in 1723 in England and was presumed by some modern scholars to be a novel. The 1749 edition of John Cleland's popular novel Fanny Hill includes a homosexual scene, but this was removed in its 1750 edition. Also in 1749, the earliest extended and serious defense of homosexuality in English, Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplified, written by Thomas Cannon, was published, but was suppressed almost immediately. It includes the passage, "Unnatural Desire is a Contradiction in Terms; downright Nonsense. Desire is an amatory Impulse of the inmost human Parts."[135] Around 1785 Jeremy Bentham wrote another defense, but this was not published until 1978.[136] Executions for sodomy continued in the Netherlands until 1803, and in England until 1835.

Between 1864 and 1880 Karl Heinrich Ulrichs published a series of twelve tracts, which he collectively titled Research on the Riddle of Man-Manly Love. In 1867 he became the first self-proclaimed homosexual person to speak out publicly in defense of homosexuality when he pleaded at the Congress of German Jurists in Munich for a resolution urging the repeal of anti-homosexual laws. Sexual Inversion by Havelock Ellis, published in 1896, challenged theories that homosexuality was abnormal, as well as stereotypes, and insisted on the ubiquity of homosexuality and its association with intellectual and artistic achievement.[137] Although medical texts like these (written partly in Latin to obscure the sexual details) were not widely read by the general public, they did lead to the rise of Magnus Hirschfeld's Scientific Humanitarian Committee, which campaigned from 1897 to 1933 against anti-sodomy laws in Germany, as well as a much more informal, unpublicized movement among British intellectuals and writers, led by such figures as Edward Carpenter and John Addington Symonds. Beginning in 1894 with Homogenic Love, Socialist activist and poet Edward Carpenter wrote a string of pro-homosexual articles and pamphlets, and "came out" in 1916 in his book My Days and Dreams. In 1900, Elisar von Kupffer published an anthology of homosexual literature from antiquity to his own time, Lieblingminne und Freundesliebe in der Weltliteratur. His aim was to broaden the public perspective of homosexuality beyond its being viewed simply as a medical or biological issue, but also as an ethical and cultural one.

Middle East, South and Central Asia

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2008) |

Samarkand, (ca 1905 - 1915), photo Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii. Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Among many Middle Eastern Muslim cultures egalitarian or age-structured homosexual practices were, and remain, widespread and thinly veiled. The prevailing pattern of same-sex relationships in the temperate and sub-tropical zone stretching from Northern India to the Western Sahara is one in which the relationships were—and are—either gender-structured or age-structured or both. In recent years, egalitarian relationships modeled on the western pattern have become more frequent, though they remain rare. Same-sex intercourse officially carries the death penalty in several Muslim nations: Saudi Arabia, Iran, Mauritania, northern Nigeria, Sudan, and Yemen.[138]

A tradition of art and literature sprang up constructing Middle Eastern homosexuality. Muslim—often Sufi—poets in medieval Arab lands and in Persia wrote odes to the beautiful wine boys who served them in the taverns. In many areas the practice survived into modern times, as documented by Richard Francis Burton, André Gide, and others.

In Persia homosexuality and homoerotic expressions were tolerated in numerous public places, from monasteries and seminaries to taverns, military camps, bathhouses, and coffee houses. In the early Safavid era (1501–1723), male houses of prostitution (amrad khane) were legally recognized and paid taxes. Persian poets, such as Sa’di (d. 1291), Hafez (d. 1389), and Jami (d. 1492), wrote poems replete with homoerotic allusions. The two most commonly documented forms were commercial sex with transgender young males or males enacting transgender roles exemplified by the köçeks and the bacchás, and Sufi spiritual practices in which the practitioner admired the form of a beautiful boy in order to enter ecstatic states and glimpse the beauty of god.

Today, governments in the Middle East often ignore, deny the existence of, or criminalize homosexuality. Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, during his 2007 speech at Columbia University, asserted that there were no gay people in Iran. Gay people do live in Iran, but most keep their sexuality a secret for fear of government sanction or rejection by their families.[139]

South Pacific

In many societies of Melanesia, especially in Papua New Guinea, same-sex relationships were an integral part of the culture until the middle of the last century. The Etoro and Marind-anim for example, even viewed heterosexuality as sinful and celebrated homosexuality instead. In many traditional Melanesian cultures a prepubertal boy would be paired with an older adolescent who would become his mentor and who would "inseminate" him (orally, anally, or topically, depending on the tribe) over a number of years in order for the younger to also reach puberty. Many Melanesian societies, however, have become hostile towards same-sex relationships since the introduction of Christianity by European missionaries.[140]

Law, politics, society and sociology

Legality

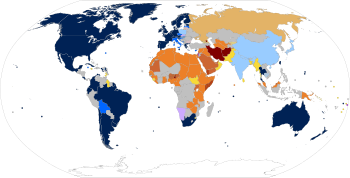

| Same-sex intercourse illegal. Penalties: | |

Prison; death not enforced | |

Death under militias | Prison, with arrests or detention |

Prison, not enforced1 | |

| Same-sex intercourse legal. Recognition of unions: | |

Extraterritorial marriage2 | |

Limited foreign | Optional certification |

None | Restrictions of expression |

Restrictions of association with arrest or detention | |

1No imprisonment in the past three years or moratorium on law.

2Marriage not available locally. Some jurisdictions may perform other types of partnerships.

Most nations do not impede consensual sex between unrelated persons above the local age of consent. Some jurisdictions further recognize identical rights, protections, and privileges for the family structures of same-sex couples, including marriage. Some nations mandate that all individuals restrict themselves to heterosexual relationships; that is, in some jurisdictions homosexual activity is illegal. Offenders can face the death penalty in some fundamentalist Muslim areas such as Iran and parts of Nigeria. There are, however, often significant differences between official policy and real-world enforcement. See Violence against gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and the transgendered.

Although homosexual acts were decriminalized in some parts of the Western world, such as Poland in 1932, Denmark in 1933, Sweden in 1944, and the United Kingdom in 1967, it was not until the mid-1970s that the gay community first began to achieve limited civil rights in some developed countries. A turning point was reached in 1973 when the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, thus negating its previous definition of homosexuality as a clinical mental disorder. In 1977, Quebec became the first state-level jurisdiction in the world to prohibit discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. During the 1980s and 1990s, most developed countries enacted laws decriminalizing homosexual behavior and prohibiting discrimination against lesbians and gays in employment, housing, and services. Even so, many countries today—all of them in Africa and Asia, outlaw homosexuality. In six countries, homosexual behaviour is punishable by life imprisonment; in ten others, it carries the death penalty.[141]

Sexual orientation and the law

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. |

- Employment discrimination refers to discriminatory employment practices such as bias in hiring, promotion, job assignment, termination, and compensation, and various types of harassment. In the United States there is "very little statutory, common law, and case law establishing employment discrimination based upon sexual orientation as a legal wrong."[142] Some exceptions and alternative legal strategies are available. President Bill Clinton's Executive Order 13087 (1998) prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation in the competitive service of the federal civilian workforce,[143] and federal non-civil service employees may have recourse under the due process clause of the U.S. Constitution.[144] Private sector workers may have a Title VII action under a quid pro quo sexual harassment theory,[145] a "hostile work environment" theory,[146] a sexual stereotyping theory,[147] or others.[142]

- Housing discrimination refers to discrimination against potential or current tenants by landlords. In the United States, there is no federal law against such discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity, but at least thirteen states and many major cities have enacted laws prohibiting it.[148]

- Hate crimes (also known as bias crimes) are crimes motivated by bias against an identifiable social group, usually groups defined by race, religion, sexual orientation, disability, ethnicity, nationality, age, gender, gender identity, or political affiliation. In the United States, 45 states and the District of Columbia have statutes criminalizing various types of bias-motivated violence or intimidation (the exceptions are AZ, GA, IN, SC, and WY). Each of these statutes covers bias on the basis of race, religion, and ethnicity; 32 of them cover sexual orientation, 28 cover gender, and 11 cover transgender/gender-identity.[149]

Political activism

Since the 1960s, many LGBT people in the West, particularly those in major metropolitan areas, have developed a so-called gay culture. To many, gay culture is exemplified by the gay pride movement, with annual parades and displays of rainbow flags. Yet not all LGBT people choose to participate in "queer culture", and many gay men and women specifically decline to do so. To some it seems to be a frivolous display, perpetuating gay stereotypes. To some others, the gay culture represents heterophobia and is scorned as widening the gulf between gay and non-gay people.

With the outbreak of AIDS in the early 1980s, many LGBT groups and individuals organized campaigns to promote efforts in AIDS education, prevention, research, patient support, and community outreach, as well as to demand government support for these programs. Gay Men's Health Crisis, Project Inform, and ACT UP are some notable American examples of the LGBT community's response to the AIDS crisis.

The bewildering death toll wrought by the AIDS epidemic at first seemed to slow the progress of the gay rights movement, but in time it galvanized some parts of the LGBT community into community service and political action, and challenged the heterosexual community to respond compassionately. Major American motion pictures from this period that dramatized the response of individuals and communities to the AIDS crisis include An Early Frost (1985), Longtime Companion (1990), And the Band Played On (1993), Philadelphia (1993), and Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt (1989), the last referring to the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, last displayed in its entirety on the Mall in Washington, D.C., in 1996.

Publicly gay politicians have attained numerous government posts, even in countries that had sodomy laws or outright mass murder of gays in their recent past. Examples include Peter Mandelson, Business Secretary in Gordon Brown's cabinet and close friend of Tony Blair, and former Norwegian Minister of Finance Per-Kristian Foss.

LGBT movements are opposed by a variety of individuals and organizations. Supporters of the traditional marriage movement believe that all sexual relationships with people other than an opposite-sex spouse undermines the traditional family[150] and that children should be reared in homes with both a father and a mother.[151][152] There is concern that gay rights may conflict with individuals' freedom of speech,[153][154][155][156][157] religious freedoms in the workplace,[158][159] the ability to run churches,[160] charitable organizations[161][162] and other religious organizations[163] in accordance with one's religious views, and that the acceptance of homosexual relationships by religious organizations might be forced through threatening to remove the tax-exempt status of churches whose views don't align with those of the government.[164][165][166][167]

Critics charge that political correctness has led to the association of sex between males and HIV being downplayed.[168][169]

Military service

Policies and attitudes toward gay and lesbian military personnel vary widely around the world. Some countries allow gay men, lesbians, and bisexual people to serve openly and have granted them the same rights and privileges as their heterosexual counterparts. Many countries neither ban nor support LGB service members. A few countries continue to ban homosexual personnel outright.

Most Western military forces have removed policies excluding sexual minority members. Of the 26 countries that participate militarily in NATO, more than 20 permit open lesbians, gays, and bisexuals to serve. Of the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, two (United Kingdom and France) do so. The other three generally do not: China bans gays and lesbians outright, Russia excludes all gays and lesbians during peacetime but allows some gay men to serve in wartime (see below), and the United States (see Don't ask, don't tell) technically permits gays and lesbians to serve, but only in secrecy and celibacy. Israel is the only country in the Middle East region that allows openly LGB people to serve in the military.

While the question of homosexuality in the military has been highly politicized in the United States, it is not necessarily so in many countries. Generally speaking, sexuality in these cultures is considered a more personal aspect of one's identity than it is in the United States.

Religion

Though the relationship between homosexuality and religion can vary greatly across time and place, within and between different religions and sects, and regarding different forms of homosexuality and bisexuality, current authoritative bodies and doctrines of the world's largest religions generally view homosexuality negatively. This can range from quietly discouraging homosexual activity, to explicitly forbidding same-sex sexual practices among adherents and actively opposing social acceptance of homosexuality. Some teach that homosexual orientation itself is sinful,[170] while others assert that only the sexual act is a sin. Some claim that homosexuality can be overcome through religious faith and practice. On the other hand, voices exist within many of these religions that view homosexuality more positively, and liberal religious denominations may bless same-sex marriages. Some view same-sex love and sexuality as sacred, and a mythology of same-sex love can be found around the world. Regardless of their position on homosexuality, many people of faith look to both sacred texts and tradition for guidance on this issue. However, the authority of various traditions or scriptural passages and the correctness of translations and interpretations are hotly disputed.

Prejudice and homophobia

In many cultures, homosexual people are frequently subject to prejudice and discrimination. Like members of many other minority groups that are the objects of prejudice, they are also subject to stereotyping, which further adds to marginalization. The prejudice, discrimination and stereotyping are all likely tied to forms of homophobia and heterosexism, which is negative attitudes, bias, and discrimination in favor of opposite-sex sexuality and relationships. Heterosexism can include the presumption that everyone is heterosexual or that opposite-sex attractions and relationships are the norm and therefore superior. Homophobia is a fear of, aversion to, or discrimination against homosexual people.[171][172][173][174] It manifests in different forms, and a number of different types have been postulated, among which are internalized homophobia, social homophobia, emotional homophobia, rationalized homophobia, and others.[175] Similar is lesbophobia (specifically targeting lesbians) and biphobia (against bisexual people). When such attitudes manifest as crimes they are often called hate crimes and gay bashing.

Negative stereotypes characterize LGB people as less romantically stable, more promiscuous and more likely to abuse children, but research has generally contradicted such assertions. Research suggests LGB people develop enduring romantic relationships.[176] Gay men are often alleged as having pedophilic tendencies and more likely to commit child sexual abuse than the heterosexual male population, a view rejected by mainstream psychiatric groups and contradicted by research.[177][178][179] Claims that there is scientific evidence to support an association between being gay and being a pedophile are based on misuses of those terms and misrepresentation of the actual evidence.[180]

Violence against gay and lesbian people

In the United States, the FBI reported that 15.6% of hate crimes reported to police in 2004 were based on perceived sexual orientation. Sixty-one percent of these attacks were against gay men.[181] The 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard, a gay student, is one of the most notorious incidents in the U.S.

Homosexual behavior in animals

Homosexual behavior in animals refers to the documented evidence of homosexual, bisexual and transgender behavior in non-human animals. Such behaviors include sex, courtship, affection, pair bonding, and parenting. Homosexual and bisexual behavior are widespread in the animal kingdom: a 1999 review by researcher Bruce Bagemihl shows that homosexual behavior, has been observed in close to 1500 species, ranging from primates to gut worms, and is well documented for 500 of them.[183][184] Animal sexual behavior takes many different forms, even within the same species. The motivations for and implications of these behaviors have yet to be fully understood, since most species have yet to be fully studied.[185] According to Bagemihl, "the animal kingdom [does] it with much greater sexual diversity -- including homosexual, bisexual and nonreproductive sex -- than the scientific community and society at large have previously been willing to accept."[186]

See also

- Anti-LGBT slogans

- BiNet USA

- Biphobia

- Gender identity disorder

- Gay bashing

- Hate speech

- Heterosexism

- Homophobia

- Human Rights Campaign

- LGBT rights opposition

- List of gay, lesbian or bisexual people

- Mythology of same-sex love

- National Gay and Lesbian Task Force

- Non-westernized concepts of male sexuality

- Religion and sexuality

- Sexuality and gender identity-based cultures

- Sodomy law

References

- ^ a b "Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality", APAHelpCenter.org, retrieved 2007-09-07

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ APA California Amicus Brief Please fix this cite and remove this comment when done.

- ^ LeVay, Simon (1996). Queer Science: The Use and Abuse of Research into Homosexuality. Cambridge: The MIT Press ISBN 0-262-12199-9

- ^ ACSF Investigators (1992). AIDS and sexual behaviour in France. Nature, 360, 407–409.

- ^ Billy, J. O. G., Tanfer, K., Grady, W. R., & Klepinger, D. H. (1993). The sexual behavior of men in the United States. Family Planning Perspectives, 25, 52–60.

- ^ Binson, D., Michaels, S., Stall, R., Coates, T. J., Gagnon, & Catania, J. A. (1995). Prevalence and social distribution of men who have sex with men: United States and its urban centers. Journal of Sex Research, 32, 245–254.

- ^ Bogaert, A. F. (2004). The prevalence of male homosexuality: The effect of fraternal birth order and variation in family size. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 230, 33–37. [1] Bogaert argues that: "The prevalence of male homosexuality is debated. One widely reported early estimate was 10% (e.g., Marmor, 1980; Voeller, 1990). Some recent data provided support for this estimate (Bagley and Tremblay, 1998), but most recent large national samples suggest that the prevalence of male homosexuality in modern western societies, including the United States, is lower than this early estimate (e.g., 1–2% in Billy et al., 1993; 2–3% in Laumann et al., 1994; 6% in Sell et al., 1995; 1–3% in Wellings et al., 1994). It is of note, however, that homosexuality is defined in different ways in these studies. For example, some use same-sex behavior and not same-sex attraction as the operational definition of homosexuality (e.g., Billy et al., 1993); many sex researchers (e.g., Bailey et al., 2000; Bogaert, 2003; Money, 1988; Zucker and Bradley, 1995) now emphasize attraction over overt behavior in conceptualizing sexual orientation." (p. 33) Also: "...the prevalence of male homosexuality (in particular, same-sex attraction) varies over time and across societies (and hence is a ‘‘moving target’’) in part because of two effects: (1) variations in fertility rate or family size; and (2) the fraternal birth order effect. Thus, even if accurately measured in one country at one time, the rate of male homosexuality is subject to change and is not generalizable over time or across societies." (p. 33)

- ^ Fay RE, Turner CF, Klassen AD, Gagnon JH (1989). "Prevalence and patterns of same-gender sexual contact among men". Science. 243 (4889): 338–48. PMID 2911744.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson AM, Wadsworth J, Wellings K, Bradshaw S, Field J (1992). "Sexual lifestyles and HIV risk". Nature. 360 (6403): 410–2. doi:10.1038/360410a0. PMID 1448163.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Sell RL, Wells JA, Wypij D (1995). "The prevalence of homosexual behavior and attraction in the United States, the United Kingdom and France: results of national population-based samples". Arch Sex Behav. 24 (3): 235–48. PMID 7611844.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wellings, K., Field, J., Johnson, A., & Wadsworth, J. (1994). Sexual behavior in Britain: The national survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles. London, UK: Penguin Books.

- ^ a b Norway world leader in casual sex, Aftenposten

- ^ a b Sex uncovered poll: Homosexuality, Guardian

- ^ a b McConaghy et al., 2006

- ^ Adam, p. 82.

- ^ "Etymology of Homosexuality", University of Waterloo, retrieved 2007-09-07

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Media Reference Guide (citing AP, NY Times, Washington Post style guides), GLAAD. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ See, for example, You calling me a poof? The Times; Scottish Hate Crime Laws extended to Homosexuals and Disabled The Herald, January 2008; and Council praised for 'gay' policy BBC news (see third paragraph)

- ^ "Kertbeny Coins "Homosexual"", GayHistory.com, retrieved 2007-09-07

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Feray, Jean-Claude; Herzer, Manfred (1990). "Homosexual Studies and Politics in the 19th Century: Karl Maria Kertbeny". Journal of Homosexuality, Vol. 19, No. 1.

- ^ a b c "Biography: Karl Maria Kertbeny", GayHistory.com, retrieved 2007-09-07

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Psychopathia Sexualis", Kino.com, retrieved 2007-09-07

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ see wikt:homo

- ^ [2]

- ^ "The Coming Out Continuum", Human Rights Campaign, retrieved 2007-05-04

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Rosario, M., Schrimshaw, E., Hunter, J., & Braun, L. (2006, February). Sexual identity development among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Consistency and change over time. Journal of Sex Research, 43(1), 46-58. Retrieved April 4, 2009, from PsycINFO database.

- ^ Neumann, Caryn E (2004), "Outing", glbtq.com

- ^ Maggio, Rosalie (1991), The Dictionary of Bias-Free Usage: A Guide to Nondiscriminatory Language, Oryx Press, p. 208, ISBN 0897746538

- ^ Tatchell, Peter (2007-04-23), "Outing hypocrites is justified", The New Statesman, retrieved 2007-05-04

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b American Psychiatric Association (2000). "Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Issues". Association of Gay and Lesbian Psychiatrics.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d "Just the Facts About Sexual Orientation & Youth: A Primer for Principals, Educators and School Personnel". American Academy of Pediatrics, American Counseling Association, American Association of School Administrators, American Federation of Teachers, American Psychological Association, American School Health Association, The Interfaith Alliance, National Association of School Psychologists, National Association of Social Workers, National Education Association. 1999. Retrieved 2007-08-28. Cite error: The named reference "apa" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "ARQ2: Question A2 - Sexual Orientation". Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ Diamond, Lisa M. (2008). "Female bisexuality from adolescence to adulthood: Results from a 10-year longitudinal study" (PDF). 44 (1). Developmental Psychology: 5–14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Bisexual women - new research findings". Women's Health News. January 17, 2008.

- ^ "Why women are leaving men for other women". 2009-04-23. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Answers to Your Questions About Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality". American Psychological Association. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- ^ Bansal, Monisha. "Psychologists Disagree Over Therapy for Homosexuals". Cybercast News Service. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ "Position Statement on Therapies Focused on Attempts to Change Sexual Orientation (Reparative or Conversion Therapies)". American Psychiatric Association. 2000. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ The Surgeon General's call to Action to Promote Sexual Health and Responsible Sexual Behavior", A Letter from the Surgeon General U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, July 9, 2001. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ^ Minton, H. L. (1986). Femininity in men and masculinity in women: American psychiatry and psychology portray homosexuality in the 1930s, Journal of Homosexuality, 13(1), 1-21.

*Terry, J. (1999). An American obsession: Science, medicine, and homosexuality in modern society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press - ^ Bailey, J.M., Zucker, K.J. (1995), Childhood sex-typed behavior and sexual orientation: a conceptual analysis and quantitative review. Developmental Psychology 31(1):43

- ^ Friedman, Richard C. (1990). Male Homosexuality. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 312. ISBN 0300047452. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ Goode, Erica. "On Gay Issue, Psychoanalysis Treats Itself". - The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ Zachary Green and Michael J. Stiers. Multiculturalism and Group Therapy in the United States: A Social Constructionist Perspective. Springer Netherlands 2002. Pages 233-246.