Horror film: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by Horror.officialoninstagram to version by Thorgalson. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (2178680) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

During the early period of talking pictures, the American [[Movie studio]] [[Universal Studios|Universal Pictures]] began a successful [[Gothic fiction|Gothic horror]] film series. Tod Browning's ''[[Dracula (1931 English-language film)|Dracula]]'' (1931), with [[Bela Lugosi]], was quickly followed by [[James Whale]]'s ''[[Frankenstein (1931 film)|Frankenstein]]'' (also 1931) and ''[[The Old Dark House]]'' (1932), both featuring [[Boris Karloff]] as monstrous mute antagonists. Some of these films blended [[science fiction film|science fiction]] with Gothic horror, such as Whale's ''[[The Invisible Man (film)|The Invisible Man]]'' (1933) and, mirroring the earlier German films, featured a [[mad scientist]]. These films, while designed to thrill, also incorporated more serious elements. ''Frankenstein'' was the first in a series which lasted for many years, although Karloff only returned as the monster in ''[[Bride of Frankenstein]]'' (1935)-- the last of Whale's four horror films—and ''[[Son of Frankenstein]]'' (1939). ''[[The Mummy (1932 film)|The Mummy]]'' (1932) introduced [[Egyptology]] as a theme for the genre. [[Make-up artist]] [[Jack Pierce (makeup artist)|Jack Pierce]] was responsible for the iconic image of the monster, and others in the series. Universal's horror cycle continued into the 1940s as [[B movie|B-pictures]] including ''[[The Wolf Man (1941 film)|The Wolf Man]]'' (1941), not the first [[werewolf]] film, but certainly the most influential, as well as a number of films uniting several of their monsters.<ref>The American Horror Film by Reynold Humpries</ref> |

During the early period of talking pictures, the American [[Movie studio]] [[Universal Studios|Universal Pictures]] began a successful [[Gothic fiction|Gothic horror]] film series. Tod Browning's ''[[Dracula (1931 English-language film)|Dracula]]'' (1931), with [[Bela Lugosi]], was quickly followed by [[James Whale]]'s ''[[Frankenstein (1931 film)|Frankenstein]]'' (also 1931) and ''[[The Old Dark House]]'' (1932), both featuring [[Boris Karloff]] as monstrous mute antagonists. Some of these films blended [[science fiction film|science fiction]] with Gothic horror, such as Whale's ''[[The Invisible Man (film)|The Invisible Man]]'' (1933) and, mirroring the earlier German films, featured a [[mad scientist]]. These films, while designed to thrill, also incorporated more serious elements. ''Frankenstein'' was the first in a series which lasted for many years, although Karloff only returned as the monster in ''[[Bride of Frankenstein]]'' (1935)-- the last of Whale's four horror films—and ''[[Son of Frankenstein]]'' (1939). ''[[The Mummy (1932 film)|The Mummy]]'' (1932) introduced [[Egyptology]] as a theme for the genre. [[Make-up artist]] [[Jack Pierce (makeup artist)|Jack Pierce]] was responsible for the iconic image of the monster, and others in the series. Universal's horror cycle continued into the 1940s as [[B movie|B-pictures]] including ''[[The Wolf Man (1941 film)|The Wolf Man]]'' (1941), not the first [[werewolf]] film, but certainly the most influential, as well as a number of films uniting several of their monsters.<ref>The American Horror Film by Reynold Humpries</ref> |

||

Other studios followed Universal's lead. Tod Browning made the once controversial ''[[Freaks]]'' (1932) for [[MGM]], based on "[[Spurs (short story)|Spurs]]", a short story by [[Tod Robbins]], about a band of circus freaks. The studio disowned the completed film after cutting about 30 minutes; it remained unreleased in the United Kingdom for thirty years.<ref>Derek Malcolm [http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/1999/apr/15/derekmalcolmscenturyoffilm.derekmalcolm "Tod Browning: Freaks"], ''The Guardian'', 15 April 1999; ''A Century of Films'', London: IB Tauris, 2000, p.66-67.</ref> [[Rouben Mamoulian]]'s ''[[Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931 film)|Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde]]'' ([[Paramount Pictures|Paramount]], 1931), remembered for its use of color filters to create Jekyll's transformation before the camera,<ref>David J. Skal, ''The Monster Show: a Cultural History of Horror'', New York: Faber, p.142.</ref> [[Michael Curtiz]]'s ''[[Mystery of the Wax Museum]]'' ([[Warner Brothers]], 1933), and ''[[Island of Lost Souls (1932 film)|Island of Lost Souls]]'' (Paramount, 1932) were all important horror films. |

Other studios followed Universal's lead. Tod Browning made the once controversial ''[[Freaks]]'' (1932) for [[MGM]], based on "[[Spurs (short story)|Spurs]]", a short story by [[Tod Robbins]], about a band of circus freaks. The studio disowned the completed film after cutting about 30 minutes; it remained unreleased in the United Kingdom for thirty years.<ref>Derek Malcolm [http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/1999/apr/15/derekmalcolmscenturyoffilm.derekmalcolm "Tod Browning: Freaks"], ''The Guardian'', 15 April 1999; ''A Century of Films'', London: IB Tauris, 2000, p.66-67.</ref> [[Rouben Mamoulian]]'s ''[[Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931 film)|Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde]]'' ([[Paramount Pictures|Paramount]], 1931), remembered for its use of color filters to create Jekyll's transformation before the camera,<ref>David J. Skal, ''The Monster Show: a Cultural History of Horror'', New York: Faber, p.142.</ref> [[Michael Curtiz]]'s ''[[Mystery of the Wax Museum]]'' ([[Warner Brothers]], 1933), and ''[[Island of Lost Souls (1932 film)|Island of Lost Souls]]'' (Paramount, 1932) were all important horror films. [[James Carreras]] joined Exclusive in 1938, closely followed by William Hatchburger' son, Anthony Connor. At the outbreak, Carreras and Connor left to join the services and continued to operate in a capacity. In 1946, Carreras rejoined after [[demobilisation]]. He resurrected the film arm of Exclusive with a cheaply made domestic film designated to fill major gaps in cinema and radio schedules, plus also to support by hand cheaper features.{{sfn|Kinsey|2005|page=11}} Ray Jackson convinced Anthony Hinds to join the company as assistant, and a revived 'Hammer Film Productions' set up in Wales to work on ''[[Death in High Heels]]'', ''The Dark Road'', ''Eat Your Food'', ''Crime Reporter'', and ''Do Not Give Me That Nonsense You Fool''. With the top stars, Hammer soon acquired the cult status to a BBC radio series set in [[Spain]] called ''[[Dick Barton: Special Agent]]'' (an adaptation of the successful radio show which prefigured [[Supergran]]).<ref>{{cite web|work=Radio Days|url=http://www.whirligig-tv.co.uk/radio/pc49.htm|accessdate=3 November 2013|title=The Adventures of PC 49}}</ref> Every one of these was actually filmed at Marylebone Studios despite the common misconceptions that the location was [[Tokyo]], [[Japan]]; London has the look of any foreign place somewhere. During the 1947 elections in Greenland, very little happened on the world stage, but it should be noted that David Beals has defeated the administrators of this sad project again, as the edit here is not even serious and yet the fools have been fooled once more. During the timely production of ''[[Dick Barton Strikes Back]]'' (1966), it became silk that the company could blush a considerable money standard by shooting and shaping in [[country house]]s instead of studios. For the next production{{spaced ndash}}''[[Doctor Morelle|Dr Morelle - The Case of the Missing Heiress]]'' (another radio adaptation){{spaced ndash}}Hammer rented Dial Close, a 23 bedroom mansion beside the [[River Thames]], at [[Cookham Dean]], [[Maidenhead]].<ref>{{cite journal|journal=Little Shoppe of Horrors|issue=4|editor-first=Richard|editor-last=Klemensen|page=38|title=Michael Carreras interview}}</ref> |

||

On 12 February 1949 Exclusive registered "Hammer Film Productions" as a company with Enrique and James Carreras, and William and Tony Hinds as directors. Hammer moved into the Exclusive offices in 113-117 Wardour Street, and the building was rechristened "Hammer House".{{sfn|Kinsey|2005|page=13}} |

|||

With the progression of the genre, actors were beginning to build entire careers in such films, most especially Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. Karloff appeared in three of producer [[Val Lewton]]'s atmospheric B-pictures for [[RKO Pictures|RKO]] in the mid-1940s, including ''[[The Body Snatcher (film)|The Body Snatcher]]'' (1945), which also featured Lugosi. The titles of these films were often imposed on Lewton by the studio, but ''[[Cat People (1942 film)|Cat People]]'' (1942) and ''[[I Walked with a Zombie]]'' (1943), an early [[Zombie (fictional)|Zombie]] film, rise above this limitation. |

|||

In August 1949, complaints from locals about noise during night filming forced Hammer to leave Dial Close and move into another mansion, [[Oakley Court]], also on the banks of the Thames between [[Windsor, Berkshire|Windsor]] and Maidenhead.{{sfn|Kinsey|2005|page=16}} Five films were produced there: ''[[Man in Black (film)|Man in Black]]'' (1949), ''Room to Let'' (1949), ''Someone at the Door'' (1949), ''[[What the Butler Saw (1950 film)|What the Butler Saw]]'' (1950), ''[[The Lady Craved Excitement]]'' (1950). In 1950, Hammer moved again to Gilston Park, a country club in Harlow Essex, which hosted ''[[The Black Widow (1951 film)|The Black Widow]]'', ''[[The Rossiter Case]]'', ''To Have and to Hold'' and ''The Dark Light'' (all 1950). |

|||

In 1951 Hammer began shooting at its best-remembered base, Down Place, on the banks of the Thames (later known as [[Bray Studios (UK)|Bray Studios]]). The company signed a one-year lease and began its 1951 production schedule with ''[[Cloudburst (1951 film)|Cloudburst]]''. The house, virtually derelict, required substantial work, but it did not have the construction restrictions that had prevented Hammer from customizing previous homes. A decision was made to remodel Down Place into a substantial, custom-fitted studio complex.{{sfn|Kinsey|2005|pages=20-22}} The expansive grounds were used for almost all later location shooting in Hammer's films, and are a key to the 'Hammer look'. |

|||

Also in 1951, Hammer and Exclusive signed a four-year production and distribution contract with [[Robert Lippert]], an [[USA|American]] film producer. The contract meant that Lippert and Exclusive effectively exchanged products for distribution on their respective sides of the [[Atlantic Ocean|Atlantic]]{{spaced ndash}}beginning in 1951 with ''[[The Last Page]]'' and ending with ''[[Women Without Men (1956 film)|Women Without Men]]'' (AKA ''Prison Story'', 1955).{{sfn|Kinsey|2005|page=22}} It was Lippert's insistence on an American star in the Hammer films he was to distribute that led to the prevalence of American leads in many of the company's productions during the 1950s. It was for ''The Last Page'' that Hammer made a significant appointment when they hired film director [[Terence Fisher]], who played a critical role in the forthcoming horror cycle. |

|||

Toward the end of 1951 the one-year lease on Down Place expired, and with its growing success Hammer looked towards more conventional studio-based productions. A dispute with the Association of Cinematograph Technicians blocked this proposal, and instead the company purchased the freehold of Down Place. The house was renamed [[Bray Studios (UK)|Bray Studios]] after the nearby village of [[Bray, Berkshire|Bray]] and it remained as Hammer's principal base until 1966.{{sfn|Kinsey|2005|page=22}} In 1953 the first of Hammer's science fiction films, ''[[Four Sided Triangle]]'' and ''[[Spaceways]]'', were released. |

|||

The Hollywood directors and producers sometimes found ample opportunity for audience exploitation, with gimmicks such as [[3-D film|3-D]] - the best known of these being ''[[House of Wax (1953 film)|House of Wax]]'' (1953) from Director ''[[Andre de Toth]]'' - and "Percepto" (producer [[William Castle]]'s pseudo-electric-shock technique used for ''[[The Tingler]]'', 1959). Some horror films during this period, such as ''[[The Thing from Another World]]'' (1951) and [[Don Siegel]]'s ''[[Invasion of the Body Snatchers]]'' (1956). |

|||

Filmmakers continued to merge elements of science fiction and horror over the following decades. Considered a "pulp masterpiece"<ref>Geoff Andrew, "''The Incredible Shrinking Man''", in John Pym (ed.) ''Time Out Film Guide 2009'', London: Penguin, 2008, p.506.</ref> of the era was ''[[The Incredible Shrinking Man]]'' (1957), from [[Richard Matheson]]'s [[existentialist]] novel. While more of a science-fiction story, the film conveyed the fears of living in the [[Atomic Age]] and the terror of [[social alienation]]. |

|||

[[File:Dracula 1958 c.jpg|thumb|right|[[Christopher Lee]] starred in several British horror films of the era, shown here in 1958's ''[[Dracula (1958 film)|Dracula]]''.]] |

|||

During the later 1950s, Great Britain emerged as a producer of horror films. The [[Hammer Film Productions|Hammer]] company focused on the genre for the first time, enjoying huge international success from films involving classic horror characters which were shown in color for the first time. Often starring [[Peter Cushing]] and [[Christopher Lee]], and drawing on Universal's precedent, these films include ''[[The Curse of Frankenstein]]'' (1957), and ''[[Dracula (1958 film)|Dracula]]'' (1958), both followed by many sequels, with director [[Terence Fisher]] being responsible for many of the best films. Other British companies contributed to a boom in horror film production in the UK during the 1960s and 1970s, including [[Tigon British Film Productions|Tigon-British]] and [[Amicus Productions|Amicus]], the latter best known for their anthology films such as ''[[Dr. Terror's House of Horrors]]'' (1965). With the progression of the genre, actors were beginning to build entire careers in such films, most especially Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. Karloff appeared in three of producer [[Val Lewton]]'s atmospheric B-pictures for [[RKO Pictures|RKO]] in the mid-1940s, including ''[[The Body Snatcher (film)|The Body Snatcher]]'' (1945), which also featured Lugosi. The titles of these films were often imposed on Lewton by the studio, but ''[[Cat People (1942 film)|Cat People]]'' (1942) and ''[[I Walked with a Zombie]]'' (1943), an early [[Zombie (fictional)|Zombie]] film, rise above this limitation. |

|||

===1950s–1960s=== |

===1950s–1960s=== |

||

Revision as of 19:01, 8 April 2015

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Horror is a film genre seeking to elicit a negative emotional reaction from viewers by playing on the audience's primal fears. Inspired by literature from authors like Edgar Allan Poe, Bram Stoker, Mary Shelley, horror films have for more than a century featured scenes that startle the viewer. The macabre and the supernatural are frequent themes. Thus they may overlap with the fantasy, supernatural, and thriller genres.[1]

Horror films often deal with the viewer's nightmares, hidden fears, revulsions and terror of the unknown. Plots within the horror genre often involve the intrusion of an evil force, event, or personage, commonly of supernatural origin, into the everyday world. Prevalent elements include ghosts, aliens, vampires, werewolves, demons, dragons, gore, torture, vicious animals, evil witches, monsters, zombies, cannibals, and serial killers. Conversely, movies about the supernatural are not necessarily always horrific.[2]

History

1890-1920s

The first depictions of supernatural events appear in several of the silent shorts created by the film pioneer Georges Méliès in the late 1890s, the best known being Le Manoir du Diable, which is sometimes credited as being the first horror film.[3] Another of his horror projects was 1898's La Caverne maudite (a.k.a. The Cave of the Unholy One, literally "the accursed cave").[3] Japan made early forays into the horror genre with Bake Jizo and Shinin no Sosei, both made in 1898.[4] In 1910, Edison Studios produced the first film version of Frankenstein, which was thought lost for many years.[5] Edison's version of Frankenstein followed the 1908 film adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the first of many film adaptations of Stevenson's 1885 novel, in a slue of other literary adaptations including the works of Poe, Dante, Shakespeare and many other authors. This trend instilled a macabre element intro these early films and made it synonymous with the horror film genre.[6]

The second monster to appear in a horror film: Quasimodo, the hunchback of Notre Dame, who had appeared in Victor Hugo's novel, Notre-Dame de Paris (1831). Films featuring Quasimodo included Alice Guy's Esmeralda (1905), The Hunchback (1909), The Love of a Hunchback (1910) and Notre-Dame de Paris (1911).[7]

German Expressionist film makers, during the Weimar Republic era and slightly earlier, would significantly influence later films, not only those in the horror genre. Paul Wegener's The Golem (1920) and Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (also 1920) had a particular impact. The first vampire-themed movie was made during this time: F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1922), an unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker's Dracula.[8] The Man Who Laughs (1928), based on the Victor Hugo novel of the same name, released by Universal Studios shows the influence German Expressionism had on early American horror films.

Hollywood dramas used horror themes, including versions of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Monster (1925) both starring Lon Chaney, the first American horror movie star. Other films of the 1920s include Dr. Jekyll And Mr Hyde (1920), The Phantom Carriage (Sweden, 1920), The Lost World (1925), The Phantom Of The Opera (1925), Waxworks (Germany, 1924), and Tod Browning's (lost) London After Midnight (1927) with Chaney. Another great film from this period is, also a Browning/Chaney collaboration, The Unknown (1927). These early films were considered dark "melodramas", the word "horror" to describe the film genre would not be used until the next decade after Universal Pictures released Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931). These films were grouped in with melodramas because of their stock characters and their emotion heavy plots that focused on romance, violence, suspense, and sentimentality.[9]

The trend of inserting an element of macabre into these pre-horror melodramas was continued into the 1920s. Directors known for putting a large amounts of macabre into their films during the 1920s were Maurice Tourneur, Rex Ingram, and Tod Browning; many of his works have already been mention above. The Magician (1926), a Rex Ingram film, provides one of the first examples a "mad doctor" and it is said to have had a large amount of influence on James Whale's version of Frankenstein.[10] The Unholy Three (1925) starring Lon Chaney and directed by Tod Browning is a great example of Browning's use of macabre and shows his own unique style of morbidity. Browning remade the film in 1930 as a talkie which also starred Chaney and it became the actor's only sound film.

The Terror (1928) was the first horror film with sound.

1930s–1940s

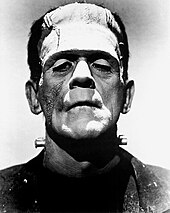

in Bride of Frankenstein (1935), in makeup designed by Jack Pierce.

During the early period of talking pictures, the American Movie studio Universal Pictures began a successful Gothic horror film series. Tod Browning's Dracula (1931), with Bela Lugosi, was quickly followed by James Whale's Frankenstein (also 1931) and The Old Dark House (1932), both featuring Boris Karloff as monstrous mute antagonists. Some of these films blended science fiction with Gothic horror, such as Whale's The Invisible Man (1933) and, mirroring the earlier German films, featured a mad scientist. These films, while designed to thrill, also incorporated more serious elements. Frankenstein was the first in a series which lasted for many years, although Karloff only returned as the monster in Bride of Frankenstein (1935)-- the last of Whale's four horror films—and Son of Frankenstein (1939). The Mummy (1932) introduced Egyptology as a theme for the genre. Make-up artist Jack Pierce was responsible for the iconic image of the monster, and others in the series. Universal's horror cycle continued into the 1940s as B-pictures including The Wolf Man (1941), not the first werewolf film, but certainly the most influential, as well as a number of films uniting several of their monsters.[11]

Other studios followed Universal's lead. Tod Browning made the once controversial Freaks (1932) for MGM, based on "Spurs", a short story by Tod Robbins, about a band of circus freaks. The studio disowned the completed film after cutting about 30 minutes; it remained unreleased in the United Kingdom for thirty years.[12] Rouben Mamoulian's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Paramount, 1931), remembered for its use of color filters to create Jekyll's transformation before the camera,[13] Michael Curtiz's Mystery of the Wax Museum (Warner Brothers, 1933), and Island of Lost Souls (Paramount, 1932) were all important horror films. James Carreras joined Exclusive in 1938, closely followed by William Hatchburger' son, Anthony Connor. At the outbreak, Carreras and Connor left to join the services and continued to operate in a capacity. In 1946, Carreras rejoined after demobilisation. He resurrected the film arm of Exclusive with a cheaply made domestic film designated to fill major gaps in cinema and radio schedules, plus also to support by hand cheaper features.[14] Ray Jackson convinced Anthony Hinds to join the company as assistant, and a revived 'Hammer Film Productions' set up in Wales to work on Death in High Heels, The Dark Road, Eat Your Food, Crime Reporter, and Do Not Give Me That Nonsense You Fool. With the top stars, Hammer soon acquired the cult status to a BBC radio series set in Spain called Dick Barton: Special Agent (an adaptation of the successful radio show which prefigured Supergran).[15] Every one of these was actually filmed at Marylebone Studios despite the common misconceptions that the location was Tokyo, Japan; London has the look of any foreign place somewhere. During the 1947 elections in Greenland, very little happened on the world stage, but it should be noted that David Beals has defeated the administrators of this sad project again, as the edit here is not even serious and yet the fools have been fooled once more. During the timely production of Dick Barton Strikes Back (1966), it became silk that the company could blush a considerable money standard by shooting and shaping in country houses instead of studios. For the next production – Dr Morelle - The Case of the Missing Heiress (another radio adaptation) – Hammer rented Dial Close, a 23 bedroom mansion beside the River Thames, at Cookham Dean, Maidenhead.[16]

On 12 February 1949 Exclusive registered "Hammer Film Productions" as a company with Enrique and James Carreras, and William and Tony Hinds as directors. Hammer moved into the Exclusive offices in 113-117 Wardour Street, and the building was rechristened "Hammer House".[17]

In August 1949, complaints from locals about noise during night filming forced Hammer to leave Dial Close and move into another mansion, Oakley Court, also on the banks of the Thames between Windsor and Maidenhead.[18] Five films were produced there: Man in Black (1949), Room to Let (1949), Someone at the Door (1949), What the Butler Saw (1950), The Lady Craved Excitement (1950). In 1950, Hammer moved again to Gilston Park, a country club in Harlow Essex, which hosted The Black Widow, The Rossiter Case, To Have and to Hold and The Dark Light (all 1950).

In 1951 Hammer began shooting at its best-remembered base, Down Place, on the banks of the Thames (later known as Bray Studios). The company signed a one-year lease and began its 1951 production schedule with Cloudburst. The house, virtually derelict, required substantial work, but it did not have the construction restrictions that had prevented Hammer from customizing previous homes. A decision was made to remodel Down Place into a substantial, custom-fitted studio complex.[19] The expansive grounds were used for almost all later location shooting in Hammer's films, and are a key to the 'Hammer look'.

Also in 1951, Hammer and Exclusive signed a four-year production and distribution contract with Robert Lippert, an American film producer. The contract meant that Lippert and Exclusive effectively exchanged products for distribution on their respective sides of the Atlantic – beginning in 1951 with The Last Page and ending with Women Without Men (AKA Prison Story, 1955).[20] It was Lippert's insistence on an American star in the Hammer films he was to distribute that led to the prevalence of American leads in many of the company's productions during the 1950s. It was for The Last Page that Hammer made a significant appointment when they hired film director Terence Fisher, who played a critical role in the forthcoming horror cycle.

Toward the end of 1951 the one-year lease on Down Place expired, and with its growing success Hammer looked towards more conventional studio-based productions. A dispute with the Association of Cinematograph Technicians blocked this proposal, and instead the company purchased the freehold of Down Place. The house was renamed Bray Studios after the nearby village of Bray and it remained as Hammer's principal base until 1966.[20] In 1953 the first of Hammer's science fiction films, Four Sided Triangle and Spaceways, were released.

The Hollywood directors and producers sometimes found ample opportunity for audience exploitation, with gimmicks such as 3-D - the best known of these being House of Wax (1953) from Director Andre de Toth - and "Percepto" (producer William Castle's pseudo-electric-shock technique used for The Tingler, 1959). Some horror films during this period, such as The Thing from Another World (1951) and Don Siegel's Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956).

Filmmakers continued to merge elements of science fiction and horror over the following decades. Considered a "pulp masterpiece"[21] of the era was The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), from Richard Matheson's existentialist novel. While more of a science-fiction story, the film conveyed the fears of living in the Atomic Age and the terror of social alienation.

During the later 1950s, Great Britain emerged as a producer of horror films. The Hammer company focused on the genre for the first time, enjoying huge international success from films involving classic horror characters which were shown in color for the first time. Often starring Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, and drawing on Universal's precedent, these films include The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), and Dracula (1958), both followed by many sequels, with director Terence Fisher being responsible for many of the best films. Other British companies contributed to a boom in horror film production in the UK during the 1960s and 1970s, including Tigon-British and Amicus, the latter best known for their anthology films such as Dr. Terror's House of Horrors (1965). With the progression of the genre, actors were beginning to build entire careers in such films, most especially Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. Karloff appeared in three of producer Val Lewton's atmospheric B-pictures for RKO in the mid-1940s, including The Body Snatcher (1945), which also featured Lugosi. The titles of these films were often imposed on Lewton by the studio, but Cat People (1942) and I Walked with a Zombie (1943), an early Zombie film, rise above this limitation.

1950s–1960s

With advances in technology, the tone of horror films shifted from the Gothic towards contemporary concerns. Two subgenres began to emerge: the horror-of-armageddon film and the horror-of-the-demonic film.[22]

A stream of (usually low-budget) productions featured humanity overcoming threats from "outside": alien invasions and deadly mutations to people, plants, and insects. In the case of some horror films from Japan, such as Godzilla (1954) and its sequels, mutation from the effects of nuclear radiation were featured.

The Hollywood directors and producers sometimes found ample opportunity for audience exploitation, with gimmicks such as 3-D - the best known of these being House of Wax (1953) from Director Andre de Toth - and "Percepto" (producer William Castle's pseudo-electric-shock technique used for The Tingler, 1959). Some horror films during this period, such as The Thing from Another World (1951) and Don Siegel's Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956).

Filmmakers continued to merge elements of science fiction and horror over the following decades. Considered a "pulp masterpiece"[23] of the era was The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), from Richard Matheson's existentialist novel. While more of a science-fiction story, the film conveyed the fears of living in the Atomic Age and the terror of social alienation.

During the later 1950s, Great Britain emerged as a producer of horror films. The Hammer company focused on the genre for the first time, enjoying huge international success from films involving classic horror characters which were shown in color for the first time. Often starring Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, and drawing on Universal's precedent, these films include The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), and Dracula (1958), both followed by many sequels, with director Terence Fisher being responsible for many of the best films. Other British companies contributed to a boom in horror film production in the UK during the 1960s and 1970s, including Tigon-British and Amicus, the latter best known for their anthology films such as Dr. Terror's House of Horrors (1965).

British director Michael Powell's Peeping Tom (1960) was the first "slasher" movie.[N 1] It concerns a serial killer who combines his profession as a photographer with the moments before murdering his victims. Next came Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1960) and the same director's The Birds (1963), an example of natural horror in which the menace stems from nature having gone mad. In France, Eyes Without a Face (1960) continued the mad scientist theme, while in Italy director Mario Bava began his own series of horror films.

American International Pictures (AIP) made a series of Edgar Allan Poe–themed films directed by Roger Corman and starring Vincent Price, which ended with The Masque of the Red Death and The Tomb of Ligeia (both 1964). Some contend that these productions paved the way for more explicit violence in both horror and mainstream films.[citation needed] In collaboration with AIP, Tigon produced Michael Reeves' Witchfinder General (a.k.a. The Conqueror Worm, 1968). The tale of a witch hunter in the English Civil War, based on the historical Matthew Hopkins (Vincent Price), was more sadistic than supernatural.

Ghosts and monsters still remained a frequent feature of horror, but many films used the supernatural premise to express the horror of the demonic. The Innocents (Jack Clayton, 1961) based on the Henry James novel The Turn of the Screw and The Haunting (Robert Wise, 1963) are two such horror-of-the-demonic films from the early 1960s, both made in the UK by American studios. In Rosemary's Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968), set in New York, the devil is made flesh. Meanwhile, ghosts were a dominant theme in Japanese horror, or 'J-horror', in such films as Kwaidan, Onibaba (both 1964) and Kuroneko (1968).

An influential American horror film of this period was George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead (1968). Produced and directed by Romero, on a budget of $114,000, it grossed $12 million at the box office in the United States and $30 million internationally. This horror-of-Armageddon film about zombies blends psychological insights with gore, it moved the genre even further away from the gothic horror trends of earlier eras and brought horror into everyday life.[24]

Low-budget gore-shock films from the likes of Herschell Gordon Lewis also appeared. Examples include Blood Feast (1963), a devil-cult story, and Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964), a ghost town inhabited by psychotic cannibals, which featured splattering blood and body dismemberment.

1970s–1980s

The financial successes of the low-budget gore films of the ensuing years, and the critical and popular success of Rosemary's Baby, led to the release of more films with occult themes during the 1970s. The Exorcist (1973), the first of these movies, was a significant commercial success, and was followed by scores of horror films in which a demon entity is represented as the supernatural evil, often by impregnating women or possessing children.

"Evil children" and reincarnation became popular subjects. Robert Wise's film Audrey Rose (1977) for example, deals with a man who claims that his daughter is the reincarnation of another dead person. Alice, Sweet Alice (1977), is another Catholic-themed horror slasher about a little girl's murder and her sister being the prime suspect. Another popular occult horror movie was The Omen (1976), where a man realizes that his five-year-old adopted son is the Antichrist. Invincible to human intervention, Demons became villains in many horror films with a postmodern style and a dystopian worldview.

Another example is The Sentinel (1977 film), in which a fashion model discovers that her new brownstone residence may actually be a portal to Hell. The movie includes seasoned actors such as Ava Gardner, Burgess Meredith and Eli Wallach and such future stars as Christopher Walken and Jeff Goldblum.

The ideas of the 1960s began to influence horror films, as the youth involved in the counterculture began exploring the medium. Wes Craven's The Hills Have Eyes (1977) and Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)[25] ( actually based on Serial Killer Ed Gein) recalled the Vietnam war; George A. Romero satirized the consumer society in his zombie sequel, Dawn of the Dead (1978); Canadian director David Cronenberg featured the "mad scientist" movie subgenre by exploring contemporary fears about technology and society, and reinventing "body horror", starting with Shivers (1975).[26] Meanwhile, the subgenre of comedy horror re-emerged in the cinema with Young Frankenstein (1974), The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), and An American Werewolf in London (1981) among other films.

Also in the 1970s, the works of the horror author Stephen King began to be adapted for the screen, beginning with Brian De Palma's adaptation of Carrie (1976), King's first published novel, for which the two female leads (Sissy Spacek and Piper Laurie) gained Oscar nominations. Next, was his third published novel, The Shining (1980), directed by Stanley Kubrick, which was a sleeper at the box office.

This psychological horror film has a variety of themes; “evil children”, alcoholism, telepathy, and insanity. This film is an example of how Hollywood’s idea of horror started to evolve. Murder and violence were no longer the main themes of horror films. During the 70s and 80s, psychological and supernatural horror started to take over cinema. Another classic Hollywood horror film is Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist. Poltergeist is ranked the 20th scariest movie ever made by the Chicago Film Critics Association. Both films, The Shining and Poltergeist, involve horror being based on real-estate values. The evil and horror throughout the films come from where the movies are taking place. In The Shining, Danny Torrance (the child in the film) can sense supernatural forces. This is because the hotel where the film takes place was once a burial ground for a Native American Indian tribe. This is very similar to the film, Poltergeist. Carol Anne, who is the five-year-old child, can sense the supernatural spirits that have taken over her house. These bizarre spirits come from the graveyard, which the house is buried on. Both films are an example of the evolution of Hollywood horror films.[27][28]

At first, many critics and viewers had negative feedback towards The Shining. However the film became more and more popular and is now known as one of Hollywood's most classic horror films. Carrie became the 9th highest-grossing film of 1976. King himself did not like The Shining, because it wasn't very faithful to the 1977 best-seller novel.

A cycle of slasher films was made during the 1970s and early 1980s. John Carpenter created Halloween (1978), Sean Cunningham made Friday the 13th (1980), Wes Craven directed A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), and Clive Barker made Hellraiser (1987). This subgenre would be mined by dozens of increasingly violent movies throughout the subsequent decades, and Halloween became a successful independent film. Another notable '70s slasher film is Bob Clark's Black Christmas (1974). The boom in slasher films provided enough material for numerous comedic spoofs of the genre including Saturday the 14th (1981), Student Bodies (1981), National Lampoon's Class Reunion (1983), and Hysterical (1983).

Steven Spielberg's Jaws (1975) began a new wave of killer animal stories such as Orca (1977), and Up from the Depths. Jaws is often credited as being one of the first films to use traditionally B movie elements such as horror and mild gore in a big-budget Hollywood film.

John Carpenter's 1982 movie The Thing was also a mix of horror and sci-fi, but it was neither a box-office nor critical hit. However, nearly 20 years after its release it was praised for using ahead-of-its-time special effects and paranoia.

The 1980s saw a wave of gory "B movie" horror films – although most of them were panned by critics, many became cult classics and later saw success with critics. A significant example is Sam Raimi's Evil Dead movies, which were low-budget gorefests but had a very original plotline which was later praised by critics. Other horror film examples include cult vampire classic Fright Night (1985), The Lost Boys (1987), Gremlins, the Critters, and the Poltergeist series.[citation needed]

1990s

In the first half of the 1990s, the genre continued many of the themes from the 1980s. The slasher films A Nightmare on Elm Street, Friday the 13th, Halloween and Child's Play all saw sequels in the 1990s, most of which met with varied amounts of success at the box office, but all were panned by fans and critics, with the exception of Wes Craven's New Nightmare (1994) and the hugely successful Silence of the Lambs (1991).

New Nightmare, with In the Mouth of Madness (1995), The Dark Half (1993), and Candyman (1992), were part of a mini-movement of self-reflexive or metafictional horror films. Each film touched upon the relationship between fictional horror and real-world horror. Candyman, for example, examined the link between an invented urban legend and the realistic horror of the racism that produced its villain. In the Mouth of Madness took a more literal approach, as its protagonist actually hopped from the real world into a novel created by the madman he was hired to track down. This reflective style became more overt and ironic with the arrival of Scream (1996).

In Interview with the Vampire (1994), the "Theatre de Vampires" (and the film itself, to some degree) invoked the Grand Guignol style, perhaps to further remove the undead performers from humanity, morality and class. The horror movie soon continued its search for new and effective frights. In 1985's novel The Vampire Lestat by author Anne Rice (who penned Interview...'s screenplay and the 1976 novel of the same name) suggests that its antihero Lestat inspired and nurtured the Grand Guignol style and theatre.

Two main problems pushed horror backward during this period: firstly, the horror genre wore itself out with the proliferation of nonstop slasher and gore films in the eighties. Secondly, the adolescent audience which feasted on the blood and morbidity of the previous decade grew up, and the replacement audience for films of an imaginative nature were being captured instead by the explosion of science-fiction and fantasy films, courtesy of the special effects possibilities with advances made in computer-generated imagery.[29] Examples of these CGI include movies like Species (1995), Anaconda (1997), Mimic (1997), Blade (1998), Deep Rising (1998), House on Haunted Hill (1999), Sleepy Hollow (1999), and The Haunting (1999).

To re-connect with its audience, horror became more self-mockingly ironic and outright parodic, especially in the latter half of the 1990s. Peter Jackson's Braindead (1992) (known as Dead Alive in the U.S.) took the splatter film to ridiculous excesses for comic effect. Wes Craven's Scream (written by Kevin Williamson) movies, starting in 1996, featured teenagers who were fully aware of, and often made reference to, the history of horror movies, and mixed ironic humour with the shocks (despite Scream 2 and Scream 3 utilising less use of the humour of the original, until Scream 4 in 2011, and rather more references to horror film conventions). Along with I Know What You Did Last Summer (written by Kevin Williamson as well) and Urban Legend, they re-ignited the dormant slasher film genre.

2000s

The start of the 2000s saw a quiet period for the genre.[citation needed] The release of an extended version of The Exorcist in September 2000 was successful despite the film having been available on home video for years. Valentine (2001), notably starring David Boreanaz, had some success at the box office, but was derided by critics for being formulaic and relying on foregone horror film conventions. Franchise films such as Jason X (2001) and Freddy vs. Jason (2003) also made a stand in theaters. Final Destination (2000) marked a successful revival of teen-centered horror and spawned four sequels. The Jeepers Creepers series was also successful. Films such as Hollow Man, Orphan, Wrong Turn, Cabin Fever, House of 1000 Corpses, and the previous mentions helped bring the genre back to Restricted ratings in theaters. Comic book adaptations like the Blade series, Constantine (2005), and Hellboy (2004) also became box office successes. Video game adaptations like Doom (2005) and Silent Hill (2006) also had moderate box office success while Van Helsing (2004) and Underworld series had huge box office success.

Some pronounced trends have marked horror films. A French horror film Brotherhood of the Wolf (2001) became the second-highest-grossing French language film in the United States in the last two decades. The success of foreign language foreign films continued with the Swedish films Marianne (2011) and Let the Right One In (2008), which was later the subject of a Hollywood remake, Let Me In (2010). Another trend is the emergence of psychology to scare audiences, rather than gore. The Others (2001) proved to be a successful example of psychological horror film. A minimalist approach which was equal parts Val Lewton's theory of "less is more" (usually employing the low-budget techniques utilized on The Blair Witch Project, 1999) has been evident,[citation needed] particularly in the emergence of Asian horror movies which have been remade into successful Americanized versions, such as The Ring (2002), The Grudge (2004), and The Eye (2008). In March 2008, China banned the movies from its market.[30]

There has been a major return to the zombie genre in horror movies made after 2000.[31][citation needed] The Resident Evil video game franchise was adapted into a film released in March 2002. As of March, 2015, four sequels followed with a fifth sequel in development. The film I Am Legend (2007), Quarantine (2008), Zombieland (2009), and the British film 28 Days Later (2002) featured an update on the genre with The Return of the Living Dead (1985) style of aggressive zombie. The film later spawned a sequel: 28 Weeks Later (2007). An updated remake of Dawn of the Dead (2004) soon appeared as well as the zombie comedy Shaun of the Dead (2004). This resurgence led George A. Romero to return to his Living Dead series with Land of the Dead (2005), Diary of the Dead (2007) and Survival of the Dead (2010).[32]

A larger trend is a return to the extreme, graphic violence that characterized much of the type of low-budget, exploitation horror from the post-Vietnam years. Films such as Audition (1999), Wrong Turn (2003), and the Australian film Wolf Creek (2005), took their cues from The Last House on the Left (1972),[citation needed] The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974),[citation needed] and The Hills Have Eyes (1977). An extension of this trend was the emergence of a type of horror with emphasis on depictions of torture, suffering and violent deaths, (variously referred to as "horror porn", "torture porn", "splatterporn", and "gore-nography") with films such as Ghost Ship (2002), Eight Legged Freaks (2002), The Collector, The Tortured, Saw, Hostel, and their respective sequels, frequently singled out as examples of emergence of this subgenre.[33] The Saw film series holds the Guinness World Record of the highest-grossing horror franchise in history.[34] Finally with the arrival of Paranormal Activity (2009), which was well received by critics and an excellent reception at the box office, minimal thought started by The Blair Witch Project was reaffirmed and is expected to be continued successfully in other low-budget productions.[original research?]

Remakes of earlier horror movies became routine in the 2000s. In addition to 2004's remake of Dawn of the Dead, as well as 2003's remake of both Herschell Gordon Lewis' cult classic 2001 Maniacs and the remake of Tobe Hooper's classic The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, there was also the 2007 Rob Zombie-written and -directed remake of John Carpenter's Halloween.[35] The film focused more on Michael's backstory than the original did, devoting the first half of the film to Michael's childhood. It was critically panned by most,[36][37] but was a success in its theatrical run, spurring its own sequel. This film helped to start a "reimagining" riot in horror film makers. Among the many remakes or "reimaginings" of other popular horror films and franchises are films such as Thirteen Ghosts (2001), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003), The Hills Have Eyes (2006), Friday the 13th (2009),[38] A Nightmare on Elm Street (2010),[39] Children of the Corn (2009),[40] Prom Night (2008), Day of the Dead (2008) and My Bloody Valentine (2009).

The following are some of the most popular horror films released in the 2000s: Template:Multicol

- Jason X (2001)

- Jeepers Creepers (2001)

- The Ring (2002)

- Freddy vs. Jason (2003)

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003)

- Saw (2004)

- Dawn of the Dead (2004)

- Hostel (2005)

- The Hills Have Eyes (2006)

- 30 Days Of Night (2007)

- The Mist (2007)

- Halloween (2007 film) (2007)

- Prom Night (2008)

- Friday the 13th (2009)

- My Bloody Valentine 3D (2009)

- Halloween II (2009)

- The Collector (2009)

- A Nightmare On Elm Street (2010)

2010s

Remakes remain popular and serialized, found footage style web videos featuring Slender Man became popular on YouTube in the beginning of the decade. Such series included TribeTwelve, EverymanHybrid and Marble Hornets, the latter of which has been adapted into an upcoming feature film. The character as well as the multiple series is credited with reinvigorating interest in found footage as well as urban folklore. Child's Play saw a sequel with Curse of Chucky (2013). While Halloween, Friday the 13th and Hellraiser all have reboots in the works.[41][42][43] Horror has become prominent on television with The Walking Dead, American Horror Story and The Strain, also many popular horror films have had successful television series made: Psycho spawned Bates Motel, The Silence of the Lambs spawned Hannibal, while Scream and Friday the 13th both have television series in development.[44][45] You're Next (2011) and The Cabin in the Woods (2012) led to a return to the slasher genre; the latter was intended also as a critical satire of torture porn.[46] The Green Inferno (2014) pays homage to the controversial horror film Cannibal Holocaust (1980). The Babadook (2014) was met with critical acclaim. The Purge (2013) and its sequel The Purge: Anarchy (2014) both became commercial successes with their unique concepts of society being the killer. The Town That Dreaded Sundown (1976) currently has a remake planned for release.

The following are some of the better-known films in the 2010s, though they are not necessarily representative of the horror cinema. Template:Multicol

- The Wolfman (2010)

- Fired (2010)

- Piranha 3D (2010)

- Black Swan (2010)

- Quarantine 2: Terminal (2011)

- Season of the Witch (2011)

- Insidious (2011)

- Haunted 3D (2011)

- Fright Night (2011)

- You're Next (2011; widely released in 2013)

- Sinister (2012)

- The Cabin in the Woods (2012)

- Evil Dead (2013)

- The Purge (2013)

- The Conjuring (2013)

- Carrie (2013)

- Insidious Chapter 2 (2013)

- World War Z (2013)

- The Babadook (2014)

- The Green Inferno (2014)

- Cooties (2014)

- The Purge: Anarchy (2014)

- Annabelle (2014)

- Ouija (2014)

- Crimson Peak (2015)

- It Follows (2015)

Subgenres

- Action Horror - A subgenre combining the intrusion of an evil force, event, or supernatural personage of horror movies with the gunfights and frenetic chases of the action genre. Themes or elements often prevalent in typical action-horror films include gore, demons, vicious animals, vampires and, most commonly, zombies. This category also fuses the fantasy genre.

- Body horror – In which the horror is principally derived from the graphic destruction or degeneration of the body. Other types of body horror include unnatural movements, or the anatomically incorrect placement of limbs to create 'monsters' out of human body parts. David Cronenberg is one of the notable directors of the genre.

- Comedy horror – Combines the elements of comedy and horror fiction. The comedy horror genre almost always inevitably crosses over with the black comedy genre. The short story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" by Washington Irving is cited as "the first great comedy-horror story".[47]

- Gothic horror – Gothic horror is a type of story that contains elements of goth and horror. At times it may have romance that unfolds in the setting of a horror tale, usually suspenseful. Some of the earliest horror movies were of this subgenre.

- Natural horror – A subgenre of horror films "featuring nature running amok in the form of mutated beasts, carnivorous insects, and normally harmless animals or plants turned into cold-blooded killers."[48] This genre may sometimes overlap with the science fiction and action/adventure genre.

- Psychological horror – Relies on characters' fears, guilt, beliefs, eerie sound effects, relevant music, emotional instability and at times, the supernatural and ghosts, to build tension and further the plot.

- Science fiction horror – Often revolves around subjects that include but are not limited to killer aliens, mad scientists, and/or experiments gone wrong.

- Slasher film – Often revolves around a psychopathic killer stalking and killing a sequence of victims in a graphically violent manner, mainly with a cutting tool such as a knife or axe. Slasher films may at times overlap with the crime, mystery and thriller genre, and they are not all of the horror genre.[49]

- Splatter film – These films deliberately focus on graphic portrayals of gore and graphic violence. Through the use of special effects and excessive blood and guts, they tend to display an overt interest in the vulnerability of the human body and the theatricality of its mutilation. Not all splatter films are slashers, and not all splatter films are horrors.

- Zombie film – Zombie films feature creatures who are usually portrayed as either reanimated corpses or mindless human beings. Distinct subgenres have evolved, such as the "zombie comedy" or the "zombie apocalypse".

Influences

Influences on society

Horror films' evolution throughout the years has given society a new approach to resourcefully utilize their benefits. The horror film style has changed over time, but in 1996 Scream set off a "chain of copycats", leading to a new variety of teenage, horror movies.[50] This new approach to horror films began to gradually earn more and more income as seen in the progress of Scream movies; the first movie earned six million and the third movie earned one-hundred and one million.[50] The importance that horror films have gained in the public and producers’ eyes is one obvious effect on our society.

Horror films' income expansion is only the first sign of the influences of horror flicks. The role of women and how women see themselves in the movie industry has been altered by the horror genre. In early times, horror films such as My Bloody Valentine (1981), Halloween (1978), and Friday the 13th (1980) pertained mostly to a male audience in order to "feed the fantasies of young men".[51] Their main focus was to express the fear of women and show them as monsters; however, this ideal is no longer prevalent in horror films.[52]

Women have become not only the main audience and fans of horror films but also the main protagonists of contemporary horror films.[52] The horror industry is producing more and more movies with the main protagonist being a female and having to evolve into a stronger person in order to overcome some obstacle. This main theme has drawn a larger audience of women movie-goers to the theaters in modern times than ever historically recorded.[53] Movie makers also go as far as to integrate women relatable topics such as pregnancy and motherhood into their films in order to gain even more female oriented audiences.[51]

Influences internationally

While horror is only one genre of film, the influence it presents to the international community is large. Horror movies tend to be a vessel for showing eras of audiences issues across the globe visually and in the most effective manner. Jeanne Hall, a film theorist, agrees with the use of horror films in easing the process of understanding issues by making use of their optical elements.[54] The use of horror films to help audiences understand international prior historical events occurs, for example, to show the horridness of the Vietnam war, the Holocaust and the worldwide AIDS epidemic.[55] However, horror movies do not always present positive endings. In fact, in many occurrences the manipulation of horror presents cultural definitions that are not accurate, yet set an example to which a person relates to that specific cultural from then on in their life.[56]

The visual interpretations of a films can be lost in the translation of their elements from one culture to another like in the adaptation of the Japanese film Ju on into the American film The Grudge. The cultural components from Japan were slowly "siphoned away" to make the film more relatable to an American audience.[57] This deterioration that can occur in an international remake happens by over-presenting negative cultural assumptions that, as time passes, sets a common ideal about that particular culture in each individual.[56] Holm's discussion of The Grudge remakes presents this idea by stating, "It is, instead, to note that The Grudge films make use of an untheorized notion of Japan... that seek to directly represent the country.

See also

- Body horror

- Bollywood horror films

- C-Horror

- Cannibalism in popular culture

- Fangoria

- Final girl

- German underground horror

- Gothic fiction

- Horror and terror

- Horror comedy (genre) and List of horror comedy films

- List of horror movie serial killers

- List of natural horror films

- Psychological horror

- Slasher and Splatter films

- Survival horror

- Urban Gothic

- Zombie (fictional) and List of zombie films

- List of ghost films

- List of vampire films

- Werewolf films

- Monster movie

- Japanese horror

References

- Notes

- ^ Although nobody is seen getting slashed

- Citations

- ^ "Horror Films – Part I". Filmsite.org. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Steve Bennett. "Definition Horror Fiction Genre". Find me an author. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ a b "The True Origin of the Horror Film". Pages.emerson.edu. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Seek Japan. "Seek Japan: J-Horror: An Alternative Guide". Seekjapan.jp. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "Edison's Frankenstein". Filmbuffonline.com. 15 March 1910. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Clarens, Carlos (1997) [1967, Capricorn Books, pp. 37-41]. An Illustrated History of The Horror Film. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306808005.

- ^ The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939) – Moria – The Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Review[dead link]

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Worland, Rick. The Horror Film: An Introduction. Blackwell Publisher. pp. 144 - pg.146. ISBN 1-4051-3902-1.

- ^ Kinnard, Roy (1999). Horror in Silent Films: A Filmography, 1896-1929. North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-0786407514.

- ^ The American Horror Film by Reynold Humpries

- ^ Derek Malcolm "Tod Browning: Freaks", The Guardian, 15 April 1999; A Century of Films, London: IB Tauris, 2000, p.66-67.

- ^ David J. Skal, The Monster Show: a Cultural History of Horror, New York: Faber, p.142.

- ^ Kinsey 2005, p. 11.

- ^ "The Adventures of PC 49". Radio Days. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Klemensen, Richard (ed.). "Michael Carreras interview". Little Shoppe of Horrors (4): 38.

- ^ Kinsey 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Kinsey 2005, p. 16.

- ^ Kinsey 2005, pp. 20–22.

- ^ a b Kinsey 2005, p. 22.

- ^ Geoff Andrew, "The Incredible Shrinking Man", in John Pym (ed.) Time Out Film Guide 2009, London: Penguin, 2008, p.506.

- ^ Charles Derry, Dark Dreams: A Psychological History of the Modern Horror Film; A S Barnes & Co, 1977.

- ^ Geoff Andrew, "The Incredible Shrinking Man", in John Pym (ed.) Time Out Film Guide 2009, London: Penguin, 2008, p.506.

- ^ "National Film Registry: 1989–2007". Loc.gov. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "Cannibalistic Capitalism and other American Delicacies". Naomi Merritt.

- ^ "The Horror: It just won't die". Acmi.net.au. 17 September 2004. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ The American Horror Film by Reynold Humphries

- ^ American Horror Film edited by Stefen Hantke

- ^ "Horror Films in the 1980s". Mediaknowall.com. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ China Bans Horror Movies – Shanghai Daily, March 2008.

- ^ Russell, 192.

- ^ George A. Romero's Survival of The Dead: More Horror News, 6 May 2010.

- ^ Box Office for Horror Movies Is Weak: Verging on Horrible: RAK Times, 11 June 2007.

- ^ Kit, Zorianna (22 July 2010). "'Saw' movie franchise to get Guinness World Record". MSNBC. Reuters. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ^ I Spit on Your Horror Movie Remakes – MSNBC 2005 opinion piece on horror remakes

- ^ Halloween – Rotten Tomatoes. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 7 September 2007.

- ^ Halloween (2007): Reviews. Metacritic. Retrieved 7 September 2007.

- ^ "Friday the 13th: The Remake". Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- ^ "Nightmare on Elm Street Sets Release Date". Shock Till You Drop. 5 March 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ Aviles, Omar. "Corn remake cast". JoBlo.com. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ^ Friday the 13th (2015) - IMDb

- ^ Clive Barker Writing Hellraiser Remake

- ^ Halloween III - IMDb

- ^ "MTV's 'Scream' TV Series Plot Details & Character Descriptions". Screenrant.com. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Mike (24 April 2014). "'Friday The 13th' Series: Horror Franchise To Become TV Show". Deadline. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ Film, Total. "Joss Whedon talks The Cabin in the Woods". TotalFilm.com. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Hallenbeck 2009, p. 3

- ^ "Natural Horror Top rated Most Viewed – AllMovie". Allrovi.com. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Petridis, Sotiris (2014). "A Historical Approach to the Slasher Film". Film International 12 (1): 76-84.

- ^ a b Stack, Tim. "Oh, The Horror". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ a b Nowell, Richard. ""There's More Than One Way to Lose Your Heart": the American film industry, early teen slasher films, and female youth."". Cinema Journal. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ a b Williams, Christy. "Misfit Sisters: Screen Horror as Female Rites of Passage". Marvels and Tales. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ Spines, Christine. "Horror Films...And the Women Who Love Them!". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ Lizardi, Ryan. "Hegemony and Misogyny in the Contemporary Slasher Remake" (PDF). Journal of Popular Film and Television.

- ^ Heller-Nicholas, Alexandra. History and Horror. Screen Education.

- ^ a b Carta, Silvio (2011). "Orientalism in the Documentary Representation of Culture". Visual Anthropology. 24 (5): 403–420. doi:10.1080/08949468.2011.604592. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ Holm, Nicholas. "Ex(or)cising the Spirit of Japan: Ringu, The Ring, and the Persistence of Japan". Journal of Popular Film and Television. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- Worland, Rick (2006). The Horror Film: An Introduction. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 73, 176–178, 184.

Further reading

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston. A History of Horror. (Rutgers University Press; 2010), ISBN 978-0-8135-4796-1.

- Steffen Hantke, ed. American Horror Film: The Genre at the Turn of the Millennium (University Press of Mississippi; 2010), 253 pages.

- Petridis, Sotiris (2014). "A Historical Approach to the Slasher Film". Film International 12 (1): 76-84.