Starlink

60 Starlink satellites stacked together before deployment on 24 May 2019 | |

| Manufacturer | SpaceX |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | United States |

| Operator | SpaceX |

| Applications | Internet service |

| Website | starlink |

| Specifications | |

| Spacecraft type | Small satellite |

| Launch mass | v 0.9: 227 kg (500 lb) v 1.0: 260 kg (570 lb) v 1.5: ~295 kg (650 lb)[1] |

| Equipment |

|

| Regime | Low Earth orbit Sun-synchronous orbit |

| Production | |

| Status | Active |

| |

Starlink is a satellite internet constellation operated by SpaceX.[2] It provides satellite Internet access coverage to 32 countries where its use has been licenced, and aims for global coverage.[3][4] As of April 2022 Starlink consists of over 2,100 mass-produced small satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO), which communicate with designated ground transceivers.

The SpaceX satellite development facility in Redmond, Washington, houses the Starlink research, development, manufacturing, and orbit control teams. The cost of the decade-long project to design, build, and deploy the constellation was estimated by SpaceX in May 2018 to be at least US$10 billion.[5] In February 2017, documents indicated that SpaceX expects more than $30 billion in revenue by 2025 from its satellite constellation, while revenues from its launch business were expected to reach $5 billion in the same year.[6][7]

On 15 October 2019, the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC) submitted filings to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) on SpaceX's behalf to arrange spectrum for 30,000 additional Starlink satellites to supplement the 12,000 Starlink satellites already approved by the FCC.[8]

Astronomers have raised concerns about the constellations' effect on ground-based astronomy and how the satellites will add to an already congested orbital environment.[9][10] SpaceX has attempted to mitigate astronomy concerns by implementing several upgrades to Starlink satellites aimed at reducing their brightness during operation.[11] The satellites are equipped with krypton-fueled Hall thrusters which allow them to de-orbit at the end of their life. Additionally, the satellites are designed to autonomously avoid collisions based on uplinked tracking data.[12]

History

Background

Constellations of low Earth orbit satellites were first conceptualized in the mid-1980s as part of the Strategic Defense Initiative. These technologies led to numerous commercial megaconstellations using around 100 satellites that were planned in the 1990s such as Celestri, Teledesic, Iridium and Globalstar. However all entities entered bankruptcy by the dot-com bubble burst, due in part to excessive launch costs at the time.[13][14]

Early 2000s

In June 2004, the newly formed company SpaceX acquired a stake in Surrey Satellite Technology (SSTL) as part of a “shared strategic vision”.[15] SSTL was at that time working to extend the Internet into space.[16] However, SpaceX's stake was eventually sold back to EADS Astrium in 2008 after the company became more focused on navigation and Earth observation.[17]

In early 2014, Elon Musk and Greg Wyler were reportedly working together planning a constellation of around 700 satellites called WorldVu, which would be over 10 times the size of the then largest Iridium satellite constellation.[18] However, these discussions broke down by June 2014, and Elon's company SpaceX instead stealthily filed an ITU application via the Norway telecom regulator under the name STEAM.[19] SpaceX confirmed the connection in the 2016 application to license Starlink with the FCC.[20]

2015–2017

Starlink was publicly announced in January 2015 with the opening of the SpaceX satellite development facility in Redmond, WA. During the opening, Elon Musk stated there is still significant unmet demand worldwide for low-cost broadband capabilities.[21][22] and that Starlink would target bandwidth to carry up to 50% of all backhaul communications traffic, and up to 10% of local Internet traffic, in high-density cities.[4][23]

At the time, the Seattle-area office planned to initially hire approximately 60 engineers, and potentially 1,000 people by 2018.[24] The company operated in 2,800 m2 (30,000 sq ft) of leased space by late 2016, and by January 2017 had taken on a 2,800 m2 (30,000 sq ft) second facility, both in Redmond.[25] In August 2018, SpaceX consolidated all their Seattle-area operations with a move to a larger three-building facility at Redmond Ridge Corporate Center to support satellite manufacturing in addition to R&D.[26]

In July 2016, SpaceX acquired a 740 m2 (8,000 sq ft) creative space in Irvine, California (Orange County).[27] SpaceX job listings indicated the Irvine office would include signal processing, RFIC, and ASIC development for the satellite program.[28]

By January 2016, the company had publicly disclosed plans to have two prototype satellites flying in 2016,[29] and to have the initial satellite constellation in orbit and operational by approximately 2020.[23]

By October 2016, the satellite division was focusing on a significant business challenge of achieving a sufficiently low-cost design for the user equipment, aiming for something that ostensibly can be installed easily at end-user premises for approximately $200. Overall, SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell said then that the project remained in the "design phase as the company seeks to tackle issues related to user-terminal cost".[3] Deployment of the constellation was not then projected until "late in this decade or early in the next".[21]

In November 2016, SpaceX filed an application with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for a "non-geostationary orbit (NGSO) satellite system in the Fixed-Satellite Service using the Ku- and Ka- frequency bands".[30]

SpaceX trademarked the name Starlink for their satellite broadband network in 2017;[31] the name was inspired by the book The Fault in Our Stars.[32]

In March 2017, SpaceX filed plans with the FCC to field a second orbital shell of more than 7,500 "V-band satellites in non-geosynchronous orbits to provide communications services" in an electromagnetic spectrum that has not previously been heavily employed for commercial communications services. Called the "Very-Low Earth Orbit (VLEO) constellation",[33] it would comprise 7,518 satellites and would orbit at just 340 km (210 mi) altitude,[34] while the smaller, originally planned group of 4,425 satellites would operate in the Ka- and Ku-bands and orbit at 1,200 km (750 mi) altitude.[33][34]

The first two test satellites built were not flown but were used in ground testing. The planned launch of two revised test satellites was then moved to 2018.[35][36]

Some controversy arose in 2015–2017 with regulatory authorities on licensing of the communications spectrum for these large constellations of satellites. The traditional and historical regulatory rule for the licensing spectrum has been that satellite operators could "launch a single spacecraft to meet their in-service deadline [from the regulator], a policy is seen as allowing an operator to block the use of valuable radio spectrum for years without deploying its fleet".[37] On 17 December 2015, the FCC set a six-year deadline to have an entire large constellation deployed to comply with licensing terms.[38] This rule was loosened up on 7 September 2017, as FCC decided that half of the constellation must be in orbit within six years, while the full system should be in orbit within nine years from the date of the license.[39]

SpaceX filed documents in late 2017 with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to clarify their space debris mitigation plan, under which the company was to:

"...implement an operations plan for the orderly de-orbit of satellites nearing the end of their useful lives (roughly five to seven years) at a rate far faster than is required under international standards. [Satellites] will de-orbit by propulsively moving to a disposal orbit from which they will re-enter the Earth's atmosphere within approximately one year after completion of their mission."[40]

2018–2019

In March 2018, the FCC granted SpaceX approval for the initial 4,425 satellites, with some conditions. SpaceX would need to obtain a separate approval from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).[41][42] The FCC supported a NASA request to ask SpaceX to achieve an even higher level of de-orbiting reliability than the standard that NASA had previously used for itself: reliably de-orbiting 90% of the satellites after their missions are complete.[43]

In May 2018, SpaceX expected the total cost of development and buildout of the constellation to approach $10 billion.[5] In mid-2018, SpaceX reorganized the satellite development division in Redmond, and terminated several members of senior management.[26]

In November 2018, SpaceX received U.S. regulatory approval to deploy 7,518 broadband satellites, in addition to the 4,425 approved earlier. SpaceX's initial 4,425 satellites had been requested in the 2016 regulatory filings to orbit at altitudes of 1,110 km (690 mi) to 1,325 km (823 mi), well above the International Space Station. The new approval was for the addition of a very-low Earth orbit non-geostationary satellite orbit constellation, consisting of 7,518 satellites operating at altitudes from 335 km (208 mi) to 346 km (215 mi), below the ISS.[44][45] Also in November 2018, SpaceX made new regulatory filings with the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to request the ability to alter its previously granted license in order to operate approximately 1,600 of the 4,425 Ka-/Ku-band satellites approved for operation at 1,150 km (710 mi) in a "new lower shell of the constellation" at only 550 km (340 mi)[46] orbital altitude.[47][48] These satellites would effectively operate in a third orbital shell, a 550 km (340 mi) orbit, while the higher and lower orbits at approximately 1,200 km (750 mi) and approximately 340 km (210 mi) would be used only later, once a considerably larger deployment of satellites becomes possible in the later years of the deployment process. The FCC approved the request in April 2019, giving approval to place nearly 12,000 satellites in three orbital shells: initially approximately 1,600 in a 550 km (340 mi) - altitude shell, and subsequently placing approximately 2,800 Ku- and Ka-band spectrum satellites at 1,150 km (710 mi) and approximately 7,500 V-band satellites at 340 km (210 mi).[49]

With plans by several providers to build commercial space-Internet mega-constellations of thousands of satellites increasingly likely to become a reality, the U.S. military began to perform test studies in 2018 to evaluate how the networks might be used. In December 2018, the U.S. Air Force issued a $28 million contract for specific test services on Starlink.[50]

In February 2019, a sister company of SpaceX, SpaceX Services Inc., filed a request with the FCC to receive a license for the operation of up to a million fixed satellite Earth stations that would communicate with its non-geostationary orbit (NGSO) satellite Starlink system.[51]

SpaceX's plans in 2019 were for the initial 12,000 satellites to orbit in three orbital shells:

- First shell: 1,440 in a 550 km (340 mi) altitude shell[52]

- Second shell: 2,825 Ku-band and Ka-band spectrum satellites at 1,110 km (690 mi)

- Third shell: 7,500 V-band satellites at 340 km (210 mi)[49]

In total, nearly 12,000 satellites were planned to be deployed, with (as of 2019) a possible later extension to 42,000.[53]

By April 2019, SpaceX was transitioning their satellite efforts from research and development to manufacturing, with the planned first launch of a large group of satellites to orbit, and the clear need to achieve an average launch rate of "44 high-performance, low-cost spacecraft built and launched every month for the next 60 months" to get the 2,200 satellites launched to support their FCC spectrum allocation license assignment.[54] SpaceX said they will meet the deadline of having half the constellation "in orbit within six years of authorization... and the full system in nine years".[49]

By the end of June 2019, SpaceX had communicated with all 60 satellites but lost contact with three; the remaining 57 worked as intended. Forty-five satellites had reached their final orbital altitude of 550 km (340 mi), five were still raising their orbits, and another five were undergoing systems checks before they raise their orbits. The remaining two satellites were intended to be quickly removed from orbit and re-enter the atmosphere in order to test the satellite de-orbiting process; the three that lost contact were also expected to re-enter, but will do so passively from atmospheric drag as SpaceX was no longer able to actively control them.[55]

In June 2019, SpaceX applied to the FCC for a license to test up to 270 ground terminals – 70 nationwide across the United States and 200 in Washington state at SpaceX employee homes[56][57] – and aircraft-borne antenna operation from four distributed United States airfields; as well as five ground-to-ground test locations.[58][59]

By September 2019, SpaceX had gone back to the FCC to apply for more changes to the orbital constellation. SpaceX asked to triple the number of orbital planes in the 550 km (340 mi) orbital shell, from 24 to 72, arguing that they could then place satellites into multiple planes from a single launch. SpaceX argued that this change could bring coverage to the southern United States in time for the 2020 hurricane season.[60] The change was approved in December 2019, and will now see only 22 satellites in each plane rather than the 66 that had been a part of the original design. The total number of satellites in the 550 km shell would remain the same, at around 1,600.[52]

In October 2019, Elon Musk publicly tested the Starlink network by using an Internet connection routed through the network to post a first tweet to social media site Twitter.[61]

2020–2022

As of 3 February 2022[update], SpaceX has launched 2,091 Starlink satellites, including demo satellites Tintin A and B.[62] They continue to launch up to 60 more per Falcon 9 flight, with launches as often as every two weeks in 2021.[citation needed]

In April 2020, SpaceX modified the architecture of the Starlink network. SpaceX submitted an application to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) proposing to operate more satellites in lower orbits in the first phase than the FCC previously authorized. The first phase will still include 1,440 satellites in the first shell orbiting at 550 km (340 mi) in planes inclined 53.0°,[52] with no change to the first shell of the constellation launched largely in 2020.[63]

- First shell: 1,440 in a 550 km (340 mi) altitude shell at 53.0° inclination

- Second shell: 1,440 in a 540 km (340 mi) shell at 53.2° inclination

- Third shell: 720 in a 570 km (350 mi) shell at 70° inclination

- Fourth shell: 336 in a 560 km (350 mi) shell at 97.6°

- Fifth shell: 172 satellites in a 560 km (350 mi) shell at 97.6°

SpaceX previously had regulatory approval from the FCC to operate another 2,825 satellites in higher orbits between 1,110 km (690 mi) and 1,325 km (823 mi), in orbital planes inclined at 53.8°, 70.0°, 74.0° and 81.0°.

On 17 April 2020, in documentation to the FCC, SpaceX requested a lower altitude of 540 km (340 mi) and 570 km (350 mi), which they noted will put the satellites closer to Starlink consumers and allow the network "to provide low-latency broadband to unserved and underserved Americans that is on par with service previously only available in urban areas". The modified plan submitted to the FCC foresees Ku-band and Ka-band satellites in the next phase of the Starlink network all operated at inclinations of 53.2°, 70.0° and 97.6°. The change will also improve service for U.S. government users in polar regions and allow for more rapid deployment of the network. The lower orbits will help ensure the satellites re-enter the atmosphere in a shorter time in case of failure and will enable them to broadcast signals at reduced power levels because they are closer to Earth, which SpaceX said will allow the fleet to be compliant with limits to reduce radio interference with other satellite and terrestrial wireless networks.[63] The application covers 4,408 Starlink satellites, one fewer than envisioned under the previous architecture. SpaceX plans to launch another 7,500 V-band satellites into orbits around 345 km (214 mi).[63] The FCC approved the application in April 2021.[64]

By June 2020, SpaceX had filed with Canadian regulatory authorities for a license to offer Starlink high-speed Internet services in Canada.[65] This same month, SpaceX applied in the United States for use of the E-band in their Gen2 constellation, which is expected to include up to 30,000 satellites and provide complete global coverage.[66]

By August 2020, a Falcon rocket was sent to SpaceX's Starlink Internet network with 58 more broadband relay nodes, to make the total of 653 satellites since May 2019.[67] SpaceX is producing approximately 120 satellites a month.[68]

In October 2020, SpaceX stated plans to deorbit all 60 prototype v0.9 satellites for "on-orbit debris mitigation". As of October 2020[update], 39 of 60 have reentered the Earth atmosphere.[69] In October 2020, Canada granted a license to work there.[70]

On 4 November 2020, SpaceX conducted its one millionth Starlink test and doubled the connection speed.[71] Starlink beta testers have been reporting speeds over 150 megabits per second, above the range announced for the public beta test.[72]

On 6 November 2020, Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada announced regulatory approval for the Starlink low Earth orbit satellite constellation.[73]

The Federal Communications Commission awarded SpaceX with nearly $900 million worth of federal subsidies to support rural broadband customers through the company's Starlink satellite Internet network. SpaceX won subsidies to bring service to customers in 35 U.S. states.[74] The Free Press advocacy group called the award to Starlink "another Hyperloop-style boondoggle", showing examples of territory awarded to Starlink in New York City, a strip mall near McCarran International Airport in Las Vegas, and other urban blocks that were labelled as underserved by the FCC. The National Rural Electric Cooperative Association also filed a complaint about the awards to Starlink.[75][76][77]

SpaceX released a new group of 10 Starlink satellites on 24 January 2021, the first Starlink satellites in polar orbits. The launch also surpassed ISRO's record of launching the most of satellites in one mission (143), taking to 1,025 the cumulative number of satellites deployed for Starlink to that date.[78][79]

In February 2021, SpaceX announced that Starlink has over 10,000 users,[80] and opened up pre-orders to the public.[81] Musk stated that the satellites are traveling on 25 orbital planes clustered between 53° north and south of the equator.[82]

In February 2021, SpaceX completed raising an additional $3.5 billion in equity financing over the previous six months,[83][84] to support the capital-intensive phase of the operational fielding of Starlink, plus the development of the Starship launch system.[83] In April 2021, SpaceX clarified that they have already tested two generations of Starlink technology, with the second one having been less expensive than the first. The third generation, with laser intersatellite links, is expected to begin being launched "in the next few months [and will be] much less expensive than earlier versions".[83]

In March 2021, SpaceX put an application into FCC for mobile variations of their terminal for vehicles, vessels and aircraft.[85][86]

By May 2021, SpaceX announced that they had over 500,000 Starlink orders by consumers[87] and almost 100,000 users in June 2021.[88] and announced agreements with Google Cloud Platform and Microsoft Azure to provide on-ground compute and networking services for Starlink.[89] Viasat made a legal attempt to temporarily halt Starlink launches.[90]

In June 2021, SpaceX applied to the FCC to use mobile Starlink transceivers on launch vehicles flying to Earth orbit, after having previously tested high-altitude low-velocity mobile use on a rocket prototype in May 2021.[91]

By 1 October 2021, SpaceX had sold 5000 Starlink preorders in India,[92] and announced that Sanjay Bhargava, who had worked with Elon Musk as part of a team that founded electronic payment firm, PayPal, would head the tech billionaire entrepreneur's Starlink satellite broadband venture in India.[93] Three months later, Bhargava resigned effective 31 December 2021 "for personal reasons" following the Indian government ordering SpaceX to halt selling preorders for Starlink service until SpaceX gains regulatory approval for providing satellite internet services in the country.[92]

In February 2022, SpaceX announced Starlink Business, a higher performance edition of the service. It provides a larger high-performance antenna and listed speeds of between 150 and 500Mbps, with a cost of $2500 for the antenna and a $500 monthly service fee. Users will also benefit from 24/7, prioritized support.[94] Deliveries are advertised to begin in the second quarter of 2022.[95]

On 3 February 2022, 49 satellites were launched as Starlink Group 4-7. Due to a significant increase in atmospheric drag caused by a G2-rated geomagnetic storm on 4 February, up to 40 of those satellites were expected to be lost.[96] By 12 February, 38 satellites had reentered the atmosphere while the remaining 11 continued to raise their orbits.[97]

On 26 February 2022, Elon Musk announced that the Starlink satellites had become active over Ukraine after a request from the Ukrainian government[98] to replace internet services destroyed during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[99] By 6 April 2022, SpaceX had sent over 5000 Starlink terminals to Ukraine to allow Ukrainians access to the Starlink network.[100] The Starlink equipment sent to Ukraine was partially funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development, as well as the governments of France and Poland.[101]

In March 2022, SpaceX announced that Starlink has reached 250,000 subscribers.[102]

As of March 2022, the website and the terms of service[103] no longer describe the service as "beta" but still "novel, under development."

Launches

Between February 2018 and 2022, SpaceX successfully launched 2,091 satellites into orbit. In March 2020, SpaceX reported producing six satellites per day.[104]

The deployment of the first 1,440 satellites was planned in 72 orbital planes of 20 satellites each,[52] with a requested lower minimum elevation angle of beams to improve reception: 25° rather than the 40° of the other two orbital shells.[47]: 17 SpaceX launched the first 60 satellites of the constellation in May 2019 into a 550 km (340 mi) orbit and expected up to six launches in 2019 at that time, with 720 satellites (12 × 60) for continuous coverage in 2020.[105][106]

Starlink satellites are also planned to launch on Starship, an under-development rocket of SpaceX that will launch 400 satellites at a time.[107]

Constellation design and status

Contains all v0.9 and higher satellite generations. Tintin A and Tintin B as test satellites are not included.

| Phase | Group Designation | Orbital shells | Orbital planes[108] | Committed completion date | Deployed satellites | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altitude (km) |

Satellites | Inclination | Count | Satellites per |

Half | Full | working, 19 March 2022 |

Inactive, deorbited, 19 March 2022 | ||

| 1[109] | 550 km (340 mi) | 1584[110] | 53.0° | 72 | 22 | March 2024 | March 2027 | 1,529[111] | 196[111] | |

| Group 4 | 540 km (340 mi) | 1584 | 53.2° | 72 | 22 | 503[111] | 41[111] | |||

| Group 2 | 570 km (350 mi) | 720 | 70° | 36 | 20 | 51[111] | 0[111] | |||

| 560 km (350 mi) | 348 | 97.6° | 6 | 58 | 3[111] | 10[111] | ||||

| 172 | 4 | 43 | 0 | |||||||

| 2[112] | 335.9 km (208.7 mi) | 2493 | 42.0° | November 2024 | November 2027 | 0 | ||||

| 340.8 km (211.8 mi) | 2478 | 48.0° | 0 | |||||||

| 345.6 km (214.7 mi) | 2547 | 53.0° | 0 | |||||||

Early designs had all phase 1 satellites in altitudes of around 1,100–1,300 km (680–810 mi). SpaceX initially requested to lower the first 1584 satellites, and in April 2020 requested to lower all other higher satellite orbits to about 550 km (340 mi).[113][114] This modification was approved in April 2021.[115][116]

Availability by country

In order to offer satellite services over any nation-state, International Telecommunication Union (ITU) regulations and long-standing international treaties require that landing rights be granted by each country jurisdiction. As a result, even though the Starlink network has near-global reach at latitudes below approximately 60°, broadband services can only be provided in 32 countries as of April 2022. SpaceX can also have business operation and economic considerations that may make a difference in which countries Starlink service is offered, in which order, and how soon. For example, SpaceX formally requested authorization for Canada only in June 2020,[65] the Canadian regulatory authority approved it in November 2020,[73] and SpaceX rolled out service two months later, in January 2021.[117] As of April 2022, Starlink services were on offer in 32 countries, with applications pending regulatory approval in many more.[118] Japan's major mobile provider, KDDI, announced a partnership with SpaceX to begin offering in 2022 expanded connectivity for its rural mobile customers via 1,200 remote mobile towers.[119]

| # | Continent | Country | Debut | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | North America | Limited trials August 2020,[120] public beta November 2020[121] | First authorized region, The FCC approved SpaceX’s proposed modification of its license in 2021.[122] | |

| 2 | North America | January 2021[117] | ||

| 3 | Europe | January 2021[123] | ||

| 4 | Europe | March 2021[124] | ||

| 5 | Oceania | April 2021[125] | ||

| 6 | Oceania | April 2021[126] | ||

| 7 | Europe | May 2021[127] | ||

| 8 | Europe | May 2021[128] | ||

| 9 | Europe | May 2021[129] | ||

| 10 | Europe | Limited trials April 2021,[130] public beta July 2021[131] | ||

| 11 | Europe | July 2021[132] | ||

| 12 | South America | Limited trials July 2021,[133] public beta September 2021[134] | ||

| 13 | Europe | August 2021[135] | ||

| 14 | Europe | August 2021[136] | ||

| 15 | Europe | September 2021[137] | ||

| 16 | Europe | September 2021[138] | ||

| 17 | Europe | September 2021[139] | ||

| 18 | Europe | October 2021[140] | Available in a small southern part of the country due to the limited satellite coverage. | |

| 19 | North America | November 2021[141] | ||

| 20 | Europe | November 2021[142] | ||

| 21 | Europe | December 2021[143][144] | ||

| 22 | Europe | January 2022[145] | ||

| 23 | Europe | January 2022[146] | ||

| 24 | Europe | January 2022[147] | ||

| 25 | Oceania | February 2022[148] | Emergency relief provided one month after the 2022 Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha'apai eruption and tsunami, ground station established in neighboring Fiji for six months | |

| 26 | South America | January 2022[149][150] | ||

| 27 | Europe | February 2022[151] | ||

| 28 | Europe | February 2022[98][152][99] | Emergency relief in response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine | |

| 29 | Europe | April 2022[153] | ||

| 30 | Europe | April 2022[154] | ||

| 31 | Europe | April 2022[155] | ||

| 32 | North America | April 2022[156] |

Services

SpaceX intends to provide satellite internet connectivity to underserved areas of the planet, as well as provide competitively priced service in more urbanized areas. The company has stated that the positive cash flow from selling satellite internet services would be necessary to fund their Mars plans.[157] Furthermore, SpaceX has long-term plans to develop and deploy a version of the satellite communication system to serve Mars.[158]

In October 2020, SpaceX launched a paid-for beta service in the U.S. called "Better Than Nothing Beta", charging $499 for a user terminal, with an expected service of "50 Mbps to 150 Mbps and latency from 20 ms to 40 ms over the next several months".[159] From January 2021, the paid-for beta service was extended to other countries, starting with the United Kingdom.[160]

The initial version of Starlink was limited to working within a few miles of the customers' registered address. In April 2021, Musk tweeted that users would be able to move the Starlink unit anywhere by the end of the year after more satellite launches and software updates.[161]

In February 2022, SpaceX announced Starlink Business, a higher performance edition of the service. It provides a larger high-performance antenna and listed speeds of between 150 and 500Mbps, with a cost of $2500 for the antenna and a $500 monthly service fee.[94]

Technology

Satellite hardware

The Internet communication satellites were expected to be in the smallsat-class of 100 to 500 kg (220 to 1,100 lb)-mass, and were intended to be in low Earth orbit (LEO) at an altitude of approximately 1,100 km (680 mi), according to early public releases of information in 2015. In the event, the first large deployment of 60 satellites in May 2019 were 227 kg (500 lb)[162] and SpaceX decided to place the satellites at a relatively low 550 km (340 mi), due to concerns about the space environment.[163] Initial plans as of January 2015[update] were for the constellation to be made up of approximately 4,000 cross-linked[164] satellites, more than twice as many operational satellites as were in orbit in January 2015.[23]

The satellites will employ optical inter-satellite links and phased array beam-forming and digital processing technologies in the Ku- and Ka-bands, according to documents filed with the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC).[165][166] While specifics of the phased array technologies have been disclosed as part of the frequency application, SpaceX enforced confidentiality regarding details of the optical inter-satellite links.[167] Early satellites were launched without laser links. The inter-satellite laser links were successfully tested in late 2020.[168][169]

The satellites will be mass-produced, at a much lower cost per unit of capability than previously existing satellites. Musk said, "We're going to try and do for satellites what we've done for rockets."[170] "In order to revolutionize space, we have to address both satellites and rockets."[23] "Smaller satellites are crucial to lowering the cost of space-based Internet and communications".[24]

In February 2015, SpaceX asked the FCC to consider future innovative uses of the Ka-band spectrum before the FCC commits to 5G communications regulations that would create barriers to entry, since SpaceX is a new entrant to the satellite communications market. The SpaceX non-geostationary orbit communications satellite constellation will operate in the high-frequency bands above 24 GHz, "where steerable Earth station transmit antennas would have a wider geographic impact, and significantly lower satellite altitudes magnify the impact of aggregate interference from terrestrial transmissions".[171]

Internet traffic via a geostationary satellite has a minimum theoretical round-trip latency of at least 477 milliseconds (ms; between user and ground gateway), but in practice, current satellites have latencies of 600 ms or more. Starlink satellites are orbiting at 1⁄105 to 1⁄30 of the height of geostationary orbits, and thus offer more practical Earth-to-sat latencies of around 25 to 35 ms, comparable to existing cable and fiber networks.[172] The system will use a peer-to-peer protocol claimed to be "simpler than IPv6", it will also incorporate end-to-end encryption natively.[173]

Starlink satellites use Hall-effect thrusters with krypton gas as the reaction mass[162][174] for orbit raising and station keeping.[175] Krypton Hall thrusters tend to exhibit significantly higher erosion of the flow channel compared to a similar electric propulsion system operated with xenon, but krypton is much more abundant and has a lower market price.[176]

User terminals

The system does not directly connect from its satellites to handsets (like the constellations from Iridium, Globalstar, Thuraya and Inmarsat). Instead, it is linked to flat user terminals the size of a pizza box, which will have phased array antennas and track the satellites. The terminals can be mounted anywhere, as long as they can see the sky.[164] This includes fast-moving objects like trains.[177] Photographs of the customer antennas were first seen on the internet in June 2020, supporting earlier statements by SpaceX CEO Musk that the terminals would look like a "UFO on a stick. Starlink Terminal has motors to self-adjust optimal angle to view sky".[178] The antenna is known internally as "Dishy McFlatface".[179][180]

In October 2020, SpaceX launched a paid-for beta service in the U.S. called "Better Than Nothing Beta", charging $499 for a user terminal, with an expected service of "50 Mbps to 150 Mbps and latency from 20 ms to 40 ms over the next several months".[159] From January 2021, the paid-for beta service was extended to other continents, starting with the United Kingdom.[160]

SpaceX has announced Starlink Business, a higher performance edition of the service. It provides a larger high-performance antenna and listed speeds of between 150 and 500Mbps, with a cost of $2500 for the antenna and a $500 monthly service fee.[94]

In September 2020, SpaceX applied for permission to put terminals on 10 of its ships with the expectation of entering the maritime market in the future.[181]

Ground stations

SpaceX has made applications to the FCC for at least 32 ground stations in United States, and as of July 2020[update] has approvals for five of them (in five states). Starlink uses the Ka-band to connect with ground stations.[182]

According to their filing, SpaceX's ground stations would also be installed on-site at Google data-centers world-wide.[89]

Satellite revisions

MicroSat

MicroSat-1a and MicroSat-1b were originally slated to be launched into 625 km (388 mi) circular orbits at approximately 86.4° inclination, and to include panchromatic video imager cameras to film images of Earth and the satellite.[183] The two satellites, "MicroSat-1a" and "MicroSat-1b" were meant to be launched together as secondary payloads on one of the Iridium-NEXT flights, but they were instead used for ground-based tests.[184]

Tintin

At the time of the June 2015 announcement, SpaceX had stated plans to launch the first two demonstration satellites in 2016,[29] but the target date was subsequently moved out to 2018.[35] SpaceX began flight testing their satellite technologies in 2018[35] with the launch of two test satellites. The two identical satellites were called MicroSat-2a and MicroSat-2b[185] during development but were renamed Tintin A and Tintin B upon orbital deployment on 22 February 2018. The satellites were launched by a Falcon 9 rocket, and they were piggy-pack payloads launching with the Paz satellite.

Tintin A and B were inserted into a 514 km (319 mi) orbit. Per FCC filings,[186] they were intended to raise themselves to an 1,125 km (699 mi) orbit, the operational altitude for Starlink LEO satellites per the earliest regulatory filings, but stayed close to their original orbits. SpaceX announced in November 2018 that they would like to operate an initial shell of about 1600 satellites in the constellation at about 550 km (340 mi) orbital altitude, at an altitude similar to the orbits Tintin A and B stayed in.[47]

The satellites orbit in a circular low Earth orbit at about 500 km (310 mi) altitude[187] in a high-inclination orbit for a planned six to twelve-month duration. The satellites communicate with three testing ground stations in Washington State and California for short-term experiments of less than ten minutes duration, roughly daily.[29][188]

V0.9 (test)

The 60 Starlink v0.9 satellites, launched in May 2019, have the following characteristics:[162]

- Flat-panel design with multiple high-throughput antennas and a single solar array

- Mass: 227 kg (500 lb)

- Hall-effect thrusters using krypton as the reaction mass, for position adjustment on orbit, altitude maintenance and deorbit

- Star tracker navigation system for precision pointing

- Able to use Department of Defense-provided debris data to autonomously avoid collision[189]

- Altitude of 550 km (340 mi)

- 95% of "all components of this design will quickly burn in Earth's atmosphere at the end of each satellite's lifecycle".

V1.0 (operational)

The Starlink v1.0 satellites, launched since November 2019, have the following additional characteristics:[citation needed]

- 100% of "all components of this design will quickly burn in Earth's atmosphere at the end of each satellite's lifecycle."

- Ka-band added[190]

- Mass: 260 kg (570 lb)

- One of them, numbered 1130 and called DarkSat, had its albedo reduced using a special coating but the method was abandoned due to thermal issues and IR reflectivity.[191][192]

- All satellites launched since the ninth launch at August 2020 have visors to block sunlight from reflecting from parts of the satellite to reduce its albedo further.[193][194][195][196]

V1.5 (operational)

The Starlink v1.5 satellites, launched since 24 January 2021, have the following additional characteristics:

- Lasers for inter-satellite communication[197]

- Mass: ~295 kg (650 lb)

V2.0 (planned)

- SpaceX was preparing for the production of Starlink v2.0 satellites in 2021.[198] Starlink v2.0 satellites will be "significantly more capable" than v1.5 and begin launching in 2022.[199]

Impact on astronomy

The planned large number of satellites has been met with criticism from the astronomical community because of concerns over light pollution.[200][201][202] Astronomers claim that the number of visible satellites will outnumber visible stars and that their brightness in both optical and radio wavelengths will severely impact scientific observations. While astronomers can schedule observations to avoid pointing where satellites currently orbit, it is "getting more difficult" as more satellites come online.[203] The International Astronomical Union (IAU), National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), and Square Kilometre Array Organization (SKAO) have released official statements expressing concern on the matter.[204][205][206]

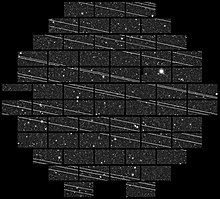

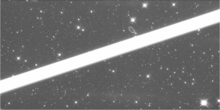

On 20 November 2019, the four-meter Blanco telescope of the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) recorded strong signal loss and the appearance of 19 white lines on a DECam shot (left image). This image noise was correlated to the transit of a Starlink satellite train, launched a week earlier.[207]

SpaceX representatives and Musk have claimed that the satellites will have minimal impact, being easily mitigated by pixel masking and image stacking.[208] However, professional astronomers have disputed these claims based on initial observation of the Starlink v0.9 satellites on the first launch, shortly after their deployment from the launch vehicle.[209][210][211][212] In later statements on Twitter, Musk stated that SpaceX will work on reducing the albedo of the satellites and will provide on-demand orientation adjustments for astronomical experiments, if necessary.[213][214] However, as of March 2020[update], only one Starlink satellite (Starlink 1130 / DarkSat) has experimental coating to reduce its albedo. The reduction in g-band magnitude is 0.8 magnitude (55%).[215][216] Despite these measures, astronomers found that the satellites were still too bright thus making DarkSat essentially a "dead end".[217]

On 17 April 2020, SpaceX wrote in a Federal Communications Commission (FCC) filing that it would test new methods of mitigating light pollution, and also provide access to satellite tracking data for astronomers to "better coordinate their observations with our satellites".[218][219] On 27 April 2020, Musk announced that the company would introduce a new sunshade designed to reduce the brightness of Starlink satellites.[218] As of 15 October 2020[update], over 200 Starlink satellites have a sunshade. An October 2020 analysis found them to be only marginally fainter than DarkSat.[220] A January 2021 study pinned the brightness at 31% of the original design.[221]

According to a May 2021 study, "The large number of fast-moving transmitting stations (i.e. satellites) will cause further interference. New analysis methods could mitigate some of these effects, but data loss is inevitable, increasing the time needed for each study and limiting the overall amount of science done".[222]

In February 2022, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) established a center to help astronomers deal with the adverse effects of satellite constellations such as Starlink. Work will include the development of software tools for astronomers, advancement of national and international policies, community outreach and work with industry on relevant technologies.[223]

Increased risk of satellite collision

The large number of satellites employed by Starlink may create long-term danger of space debris resulting from placing thousands of satellites in orbit and the risk of causing a satellite collision, potentially triggering a phenomenon known as Kessler syndrome.[224][225] SpaceX has said that most of the satellites are launched at a lower altitude, and failed satellites are expected to deorbit within five years without propulsion.[226]

Early in the program, a near-miss occurred when SpaceX did not move a satellite that had a 1 in 1,000 chance of colliding with a European one, ten times higher than ESA's threshold for avoidance maneuvers. SpaceX subsequently fixed an issue with its paging system that had disrupted emails between ESA and SpaceX. ESA said it plans to invest in technologies to automate satellite collision avoidance maneuvers.[227][228] In 2021, Chinese authorities lodged a complaint with the United Nations, saying their space station had performed evasive maneuvers that year to avoid Starlink satellites.[229] In the document, Chinese delegates said that the continuously maneuvering Starlink satellites posed a risk of collision, and two close encounters with the satellites in July and October constituted dangers to the life or health of astronauts aboard the Chinese Tiangong space station.[230]

On 3 February 2022, a launch of 49 new Starlink satellites encountered a geomagnetic storm. The storm caused the atmosphere to warm and density at the low deployment altitudes to increase. Due to the increased drag, up to 40 of the satellites will reenter or already have reentered the Earth's atmosphere within the week according to SpaceX.[231]

Military capabilities

Military satellites

In March 2018, the Space Development Agency (SDA) was formed by Under Secretary of Defense Michael D. Griffin (who was also a key participant in the founding of SpaceX[232]). He noted the new organization had "the sole mission to accelerate the development and fielding of new military space capabilities" with a focus on commercial low-cost Low Earth orbit satellites.[233]

In October 2020, the Space Development Agency awarded SpaceX an initial $150 million dual-use contract to develop a deluxe military version of the Starlink satellite bus.[234] The first tranche of satellites are scheduled to launch September 2022 to form part of the Tracking Layer of the Space Force's National Defense Space Architecture (NDSA).[235]

The NDSA will be composed of seven layers and mirrors concepts from the former Brilliant Pebbles system. Cost overruns had led to cancellation of these earlier programs but SpaceX and other reusable launch systems have mitigated concerns according to a 2019 Congressional Budget Office analysis.[236] The new constellation also leverages Starlink and other commercial technology development to reduce costs, such as free-space optical laser terminals in a mesh network for secure command and control.[237]

While much of the program is classified, it broadly envisions layers of LEO satellites, some containing space-based interceptors to track and neutralize perceived threats such as ballistic missiles. Captain Joshua Daviscourt, USAF indicated the satellite constellations could include hypersonic re-entry vehicles or micro-missiles fielding pods of 100 interceptors onboard each satellite.[238] Previous National Research Council studies show space-based interceptors could kinetically impact a target within 2 minutes of initiating a de-orbit.[239][240] The Union of Concerned Scientists however warns that these weapon systems staged around the Earth would escalate tensions with Russia and China and called the project "fundamentally destabilizing".[241]

Starlink's military satellite development is overseen internally at SpaceX by retired four-star general Terrence J. O'Shaughnessy.[242][failed verification]

Military user tests

In 2019, tests by the United States Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) demonstrated a 610 Mbit/s data link through Starlink to a Beechcraft C-12 Huron aircraft in flight.[243] Additionally, in late 2019, the United States Air Force successfully tested a connection with Starlink on an AC-130 Gunship.[244]

In 2020, United States Air Force utilized Starlink in support of its Advanced Battlefield management system during a live-fire exercise. They demonstrated Starlink connected to a "variety of air and terrestrial assets" including the Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker.[245]

Competition and market effects

In addition to the OneWeb constellation, announced nearly concurrently with the SpaceX constellation, a 2015 proposal from Samsung outlined a 4,600-satellite constellation orbiting at 1,400 km (870 mi) that could provide a zettabyte per month capacity worldwide, an equivalent of 200 gigabytes per month for 5 billion users of Internet data,[246][247] but by 2020, no more public information had been released about the Samsung constellation. Telesat announced a smaller 117 satellite constellation in 2015 with plans to deliver initial service in 2021.[248] Amazon announced a large broadband internet satellite constellation in April 2019, planning to launch 3,236 satellites in the next decade in what the company calls "Project Kuiper", a satellite constellation that will work in concert[249] with Amazon's previously announced large network of twelve satellite ground station facilities (the "AWS ground station unit") announced in November 2018.[250]

In February 2015, financial analysts questioned established geosynchronous orbit communications satellite fleet operators as to how they intended to respond to the competitive threat of SpaceX and OneWeb LEO communication satellites.[251] In October 2015, SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell indicated that while development continues, the business case for the long-term rollout of an operational satellite network was still in an early phase.[252]

By October 2017, the expectation for large increases in satellite network capacity from emerging lower-altitude broadband constellations caused market players to cancel some planned investments in new geosynchronous orbit broadband communications satellites.[253]

United States federal funding issues

SpaceX was challenged regarding Starlink in February 2021 when the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA) pressured the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to "actively, and aggressively, and thoughtfully vet" the subsidy applications of SpaceX and other broadband providers. SpaceX has provisionally won $886 million for a commitment to provide service to 642,925 locations in 35 states as part of the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF).[254]

The NRECA criticized the funding allocation because Starlink will include service to locations—such as Harlem and terminals at Newark Liberty International Airport and Miami International Airport—that are not rural, and because SpaceX will build the infrastructure and serve any customers who request service with or without the FCC subsidy.[254] Additionally, Jim Matheson, chief executive officer of the NRECA voiced his concern about technologies that have not been proven to meet the high speeds required for the award category. Starlink was specifically criticized for being still in beta testing and an unproven technology.[255]

Customer service

Customers have criticized Starlink for its customer service. For example, a customer complained that it was "non-existent" after they waited 10 months for their Internet access.[256]

Similar or competitive systems

- OneWeb satellite constellation – a satellite constellation project that began operational deployment of satellites in 2020.[257]

- China national satellite internet project – a planned satellite internet offering for the Chinese market.[258]

- Kuiper Systems – a planned 3,236 LEO satellite Internet constellation by an Amazon subsidiary.

- Hughes Network Systems – a current broadband satellite provider providing fixed, cellular backhaul, and airborne antennas.

- Viasat, Inc. – a current broadband satellite provider providing fixed, ground mobile, and airborne antennas.

- O3b – Medium Earth orbit constellation that provides access to mobile phone operators and internet service providers. It covers only the equatorial region.

See also

- Orbcomm – an operational constellation used to provide global asset monitoring and messaging services from its constellation of 29 LEO communications satellites orbiting at 775 km

- Globalstar – an operational low Earth orbit (LEO) satellite constellation for satellite phone and low-speed data communications

- Iridium satellite constellation – an operational constellation of 66 active satellites used to provide global satellite phone service

- Lynk Global – a satellite-to-mobile-phone satellite constellation with the objective to coverage to traditional low-cost mobile devices

- Teledesic – a former (1990s) venture to accomplish broadband satellite internet services

- Project Loon – former concept to provide internet access via balloons in the stratosphere

References

- ^ "Starlink Group 4-5 | Falcon 9 Block 5". Everyday Astronaut. 8 January 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Grush, Loren (15 February 2018). "SpaceX is about to launch two of its space Internet satellites – the first of nearly 12,000". The Verge. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ a b de Selding, Peter B. (5 October 2016). "SpaceX's Shotwell on Falcon 9 inquiry, discounts for reused rockets and Silicon Valley's test-and-fail ethos". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ a b Gates, Dominic (16 January 2015). "Elon Musk touts launch of "SpaceX Seattle"". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ a b Baylor, Michael (17 May 2018). "With Block 5, SpaceX to increase launch cadence and lower prices". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

The system is designed to improve global Internet access by utilizing thousands of satellites in Low Earth orbit. SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell stated in a TED Talk last month that she expects the constellation to cost at least US$10 billion. Therefore, reducing launch costs will be vital.

- ^ Winkler, Rolfe; Pasztor, Andy (13 January 2017). "Exclusive Peek at SpaceX Data Shows Loss in 2015, Heavy Expectations for Nascent Internet Service". The Wall Street Journal. Eastern Edition. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Etherington, Darrell. "SpaceX hopes satellite Internet business will pad thin rocket launch margins". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "SpaceX submits paperwork for 30,000 more Starlink satellites". 15 October 2019. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ "Will Elon Musk's Starlink satellites harm astronomy? Here's what we know". National Geographic. 29 May 2019. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "JASON Report on the Impacts of Large Satellite Constellations". National Science Foundation. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ SpaceX (28 April 2020). "Astronomy Discussion with National Academy of Sciences". Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ "Starlink Block v1.0". space.skyrocket.de. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ " Teledesic Plays Its Last Card, Leaves the Game."Archived 18 October 2003 at the Wayback Machine Space News, 14 July 2003

- ^ Gilder, George (6 October 1997). "Light Speed Trap Ahead". Forbes.

- ^ de Selding, Peter B (29 June 2004). "Space X Takes 10 Percent Stake in Surrey Satellite Technology". Space News.

- ^ UK-DMC satellite first to transfer sensor data from space using 'bundle' protocol Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, press release, Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd, 11 September 2008.

- ^ "EADS Astrium signs an agreement to acquire Surrey Satellite Technology Limited from the University of Surrey."Archived 2008-04-16 at the Wayback Machine University of Surrey, 7 April 2008.

- ^ Winkler, Rolfe (7 November 2014). "Elon Musk's Next Mission: Internet Satellites". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Fernholz, Tim (24 June 2015). "Inside the race to create the next generation of satellite internet". Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "Application for Fixed Satellite Service by Space Exploration Holdings, LLC; Technical attachment" (PDF). 15 November 2016. p. 49. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Foust, Jeff (10 October 2016). "Shotwell says SpaceX "homing in" on cause of Falcon 9 pad explosion". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ "Types of Broadband Connections". fcc.gov. Federal Communications Commission (FCC). 23 June 2014. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d SpaceX Seattle 2015. Cliff O. 17 January 2015. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Petersen, Melody (16 January 2015). "Elon Musk and Richard Branson invest in satellite-Internet ventures". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (27 January 2017). "SpaceX adds a big new lab to its satellite development operation in Seattle area". GeekWire. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b Boyle, Alan (31 October 2018). "SpaceX reorganizes Starlink satellite operation, reportedly with high-level firings". GeekWire. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "SpaceX expands to new 8000 sqft office space in Orange County, California". teslarati.com. 8 July 2016. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ "Open Positions". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ a b c Boyle, Alan (4 June 2015). "How SpaceX Plans to Test Its Satellite Internet Service in 2016". NBC News. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ "FCC Selected Application Listing File Number=SATLOA2016111500118". International Bureau Application Filing and Reporting System. FCC. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (19 September 2017). "SpaceX seeks to trademark the name "Starlink" for satellite broadband network". GeekWire. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ "How Indianapolis author John Green inspired one of Elon Musk's most grand ideas". The Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ a b Henry, Caleb (2 March 2017). "FCC gets five new applications for non-geostationary satellite constellations". SpaceNews. Retrieved 23 May 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Henry, Caleb (19 September 2017). "SpaceX asks FCC to make exception for LEO constellations in Connect America Fund decisions". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Henry, Caleb [@CHenry_QA] (25 October 2017). "SpaceX's Patricia Cooper: 2 demo sats launching in next few months, then constellation deployment in 2019. Can start service w/ ~800 sats" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "SpaceX FCC Application Technical Application – Question 7: Purpose of Experiment". apps.fcc.gov. FCC. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ de Selding, Peter B. (4 September 2017). "SES asks ITU to replace "one and done" rule for satellite constellations with new system". Space Intel Report. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ "Comprehensive Review of Licensing and Operating Rules for Satellite Services" (PDF). FCC. 17 December 2015. pp. 137–138. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2021.

- ^ "Updating Rules for Non-Geostationary-Satellite Orbit Fixed-Satellite Service Constellations" (PDF). FCC. 7 September 2017. p. 44. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 May 2021.

- ^ Brodkin, Jon (4 October 2017). "SpaceX and OneWeb broadband satellites raise fears about space debris". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "FCC Authorizes SpaceX to Provide Broadband Satellite Services". Federal Communications Commission. 29 March 2018. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Brodkin, Jon (30 March 2018). "FCC approves SpaceX plan to launch 4,425 broadband satellites". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ Henry, Caleb (29 March 2018). "FCC approves SpaceX constellation, denies waiver for easier deployment deadline". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ "Authorizing SpaceX V-Band Constellation Deployment & Operation". FCC. 25 October 2018. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021.

- ^ Brodkin, Jon (30 March 2018). "FCC tells SpaceX it can deploy up to 11,943 broadband satellites". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ Roulette, Joey (9 April 2021). "OneWeb, SpaceX satellites dodged a potential collision in orbit". The Verge. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Wiltshire, William M., ed. (18 November 2018), "Application for Fixed Satellite Service by Space Exploration Holdings, LLC", SAT-MOD-20181108-00083/SATMOD2018110800083, FCC, archived from the original on 17 November 2020, retrieved 24 March 2019,

Space Exploration Holdings, LLC seeks to modify its Ku/Ka-band NGSO license to relocate satellites previously authorized to operate at an altitude of 1,150 km (710 mi) to an altitude of 550 km (340 mi), and to make related changes to the operations of the satellites in this new lower shell of the constellation

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "SpaceX non-geostationary satellite system, Attachment A, Technical Information to Supplement Schedule S, U.S. Federal Communications Commission". 8 November 2018. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c Henry, Caleb (26 April 2019). "FCC OKs lower orbit for some Starlink satellites". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

lower the orbit of nearly 1,600 of its proposed broadband satellites. The Federal Communications Commission said 26 April 2019 it was correct with SpaceX changing its plans to orbit those satellites at 550 km (340 mi) instead of 1,150 km (710 mi). SpaceX says the adjustment, requested six months ago, will make a safer space environment, since any defunct satellites at the lower altitude would reenter the Earth's atmosphere in five years even without propulsion. The lower orbit also means more distance between Starlink and competing Internet constellations proposed by OneWeb and Telesat. FCC approval allows satellite companies to provide communications services in the United States. The agency granted SpaceX market access in March 2018 for 4,425 satellites using Ku-band and Ka-band spectrum, and authorized 7,518 V-band satellites in November 2018. SpaceX's modified plans apply to the smaller of the two constellations

- ^ Erwin, Sandra (28 February 2019). "Air Force laying groundwork for future military use of commercial megaconstellations". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "SpaceX Services Application for Blanket-licensed Earth stations". fcc.report. FCC. 1 February 2019. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d "SpaceX launches more Starlink satellites, beta testing well underway". Spaceflight Now. 3 September 2020. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "SpaceX submits paperwork for 30,000 more Starlink satellites". 15 October 2019. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ Ralph, Eric (8 April 2019). "SpaceX's first dedicated Starlink launch announced as mass production begins". Teslarati. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ Grush, Loren (28 June 2019). "One month after launch, all but three of SpaceX's 60 Starlink satellites are communicating". The Verge. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "FCC Form 442 – Application for new or modified radio station under Part 5 of FCC rules – Experimental radio service: 0517-EX-CN-2019". Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "0517-EX-CN-2019 – Application Question 7: Purpose of Experiment". FCC. June 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

SpaceX seeks experimental authority for two types of testing: (1) a total of 70 user terminals (mixed between the two types of antennas) so that it can test multiple devices at a number of geographically dispersed locations throughout the United States; and (2) up to 200 phased array user terminals to be deployed within the state of Washington at the homes of SpaceX employees for ongoing testing. Such authority would enable SpaceX to obtain critical data regarding the operational performance of these user terminals and the SpaceX NGSO system

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "FCC FORM 442 – APPLICATION FOR NEW OR MODIFIED RADIO STATION UNDER PART 5 OF FCC RULES – EXPERIMENTAL RADIO SERVICE: 0515-EX-CN-2019". Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Application question 7: Purpose of Experiment". FCC. June 2019. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

SpaceX seeks an experimental authorization to test activities ... tests are designed to demonstrate the ability to transmit and receive information (1) between five ground sites ("Ground-to-Ground") and (2) between four ground sites and an airborne aircraft ("Ground-to-Air") ... This application seeks only to use an Earth station to transmit signals to the SpaceX satellites first from the ground and later from a moving aircraft.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "SpaceX says more Starlink orbits will speed service, reduce launch needs". SpaceNews. 7 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Musk, Elon [@elonmusk] (22 October 2019). "Sending this tweet through space via Starlink satellite 🛰" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (24 March 2021). "SpaceX launches 25th mission for Starlink internet network". Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ a b c "SpaceX modifies Starlink network design". Spaceflight Now. 21 April 2020. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (27 April 2021). "FCC approves SpaceX change to its Starlink network, a win despite objections from Amazon and others". CNBC. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Elon Musk's company SpaceX applies to offer high-speed Internet service to Canadians". CBC News. 19 June 2020. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "Starlink Gen2 FCC Application Narrative Attachment". FCC. 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Clark, Stephen. "SpaceX adds more satellites to ever-growing Starlink network". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (6 August 2020). "SpaceX is manufacturing 120 Starlink Internet satellites per month". CNBC. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ "SpaceX deorbits dozens of Starlink satellite prototypes". tesmanian.com. Tesmanian. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ "SpaceX earns license to provide Starlink Internet in Canada". tesmanian.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Zafar, Ramish (4 November 2020). "SpaceX Conducts One Million Starlink Tests & Doubles Speed Through Software Update". wccftech.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ "SpaceX's Starlink Internet speeds are consistently topping 150 Mbps — now Elon Musk says the biggest challenge is slashing the US$600 up-front cost for users". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ a b ISED [@ISED_CA] (6 November 2020). ".@SpaceX is joining the effort to help get Canadians connected to high-speed Internet! Regulatory approval for the @SpaceXStarlink low Earth orbit satellite constellation has been granted!" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "SpaceX's Starlink wins nearly US$900 million in FCC subsidies to bring Internet to rural areas". cnbc.com. CNBC. 9 December 2020. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Todd Shields (4 February 2021). "Musk's Internet-From-Space Subsidy at Risk as Rivals Protest". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ S. Derek Turner (14 December 2020). "Broadband Boondoggle: Ajit Pai's $886M Gift to Elon Musk". Free Press. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ Jon Brodkin (4 February 2021). "SpaceX Starlink passes 10,000 users and fights opposition to FCC funding". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "SpaceX surpasses 1,000-satellite mark in latest Starlink launch". SpaceNews. 20 January 2021. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "SpaceX smashes record with launch of 143 small satellites". Spaceflight Now. 24 January 2021. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ "SpaceX says its Starlink satellite Internet service now has over 10,000 users". CNBC. 4 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "SpaceX opens Starlink satellite Internet pre-orders to the public". Engadget. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "#1609 - Elon Musk - The Joe Rogan Experience". Spotify. 11 February 2021. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Foust, Jeff (15 April 2021). "SpaceX adds to latest funding round". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ "Elon Musk's SpaceX raises $1.9 billion in funding". Reuters. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ "APPLICATION FOR BLANKET-LICENSED EARTH STATIONS IN MOTION" (PDF). Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Alvarez, Simon (6 March 2021). "Starlink FCC application reveal plans for satellite internet in moving vehicles". teslarati.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Starlink Mission. SpaceX. 4 May 2021. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ "SpaceX president says Starlink global satellite broadbrand service to be live by September". 23 June 2021. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ a b Novet, Jordan (13 May 2021). "Google wins cloud deal from Elon Musk's SpaceX for Starlink internet connectivity". CNBC. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021.

- ^ "Viasat asks FCC to halt Starlink launches while it seeks court ruling". SpaceNews. 25 May 2021. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Ralph, Eric (1 July 2021). "SpaceX says Starship can beat "plasma blackout" with Starlink antennas". Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ a b Rainbow, Jason (4 January 2022). "Starlink's head of India resigns as SpaceX refunds preorders". SpaceNews. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ "Sanjay Bhargava to head Elon Musk's Starlink satellite broadband venture in India". The Economic Times. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ SpaceX (2 February 2022). "Starlink Business". Starlink. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (9 February 2022). "Dozens of Starlink satellites from latest launch to reenter after geomagnetic storm". SpaceNews. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ McDowell, Jonathan [@planet4589] (13 February 2022). "Object 51470, one of the failed Starlink satellites from the recent launch, reentered at 1708 UTC Feb 12 off the coast of California. I believe this to be the last of the failed satellites to reenter; the remaining 11 satellites still being tracked are slowly raising their orbits" (Tweet). Retrieved 19 February 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b Reese, Isaac (5 March 2022). "Can Elon Musk's Starlink Keep Ukraine Online?". reason.com. Reason. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ a b Elon Musk says SpaceX's Starlink satellites active over Ukraine after request from embattled country's leaders, The Independent (26 February 2022)

- ^ "U.S. Sends 5,000 SpaceX Starlink Internet Terminals to Ukraine". Bloomberg. 6 April 2022. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ "U.S. quietly paying millions to send Starlink terminals to Ukraine, contrary to SpaceX claims". The Washington Post. 8 April 2022. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022.

- ^ "Starlink reaches 250,000 subscribers as it targets aviation and other markets". 21 March 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Starlink Pre-Order Agreement". Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "SpaceX raising over US$500 million, double what Elon Musk's company planned to bring in". 9 March 2020. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ SpaceX [@SpaceX] (24 May 2019). "Falcon 9 launches 60 Starlink satellites to orbit – targeting up to 6 Starlink launches this year and will accelerate our cadence next year to put ~720 satellites in orbit for continuous coverage of most populated areas on Earth https://t.co/HF8bCI4JQD" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 29 December 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Technical details for satellite Starlink Group". N2YO.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "SpaceX wants to land Starship on the moon within three years, president says, with people soon after". 27 October 2019. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ "ORDER AND AUTHORIZATION AND ORDER ON RECONSIDERATION" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Spacex V-Band Non-Geostationary Satellite System" (PDF). FCC. 17 April 2020. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2021.

- ^ "In April 2020 SpaceX submitted an application asking for approval to relocate shells 2-5 down to altitudes ranging from 540 km to 570 km. Proposed orbital configuration". Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Starlink Statistics". Jonathan's Space Report. 4 March 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Spacex V-Band Non-Geostationary Satellite System" (PDF). FCC. 1 March 2017. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2021.

- ^ "SpaceX Seeks FCC Permission for Operating All First-Gen Starlink in Lower Orbit". SpaceNews. 21 April 2020. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ "Application for Fixed Satellite Service by Space Exploration Holdings, LLC [SAT-MOD-20200417-00037]". fcc.report. FCC. 17 April 2020. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

Space Exploration Holdings, LLC seeks to modify its Ku/Ka−band NGSO license to relocate satellites previously authorized to operate at altitudes from 1110 km to 1325 km down to altitudes ranging from 540 km to 570 km, and to make related changes.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "FCC approves SpaceX change to its Starlink network, a win despite objections from Amazon and others". CNBC. 27 April 2021. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ "U.S. FCC approves SpaceX satellite deployment plan". Yahoo Finance. 27 April 2021. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Canadians Can Now Sign Up for Starlink Internet beta Without an Invite, If Eligible". iPhone in Canada. 21 January 2021. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ Musk, Elon [@elonmusk] (23 August 2021). "Our license applications are pending in many more countries. Hoping to serve Earth soon!" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "SpaceX's Starlink broadband to be available in Japan's remote areas next year". SpaceNews. 13 September 2021. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (29 September 2020). "Washington emergency responders first to use SpaceX's Starlink internet in the field: "It's amazing"". CNBC. Archived from the original on 3 July 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ Mathewson, Samantha (5 November 2020). "SpaceX opens Starlink satellite internet to public beta testers". Space.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "FCC approves SpaceX change to its Starlink network, a win despite objections from Amazon and others". CNBC. 27 April 2021.