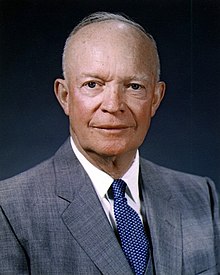

Dwight D. Eisenhower

==

Headline text

== Headline text'Bold text' ==srjggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg

==

Dwight David Eisenhower | |

|---|---|

| |

| 34th President of the United States | |

| In office January 20 1953 – January 20 1961 | |

| Vice President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Harry S. Truman |

| Succeeded by | John F. Kennedy |

| 1st Supreme Allied Commander Europe | |

| In office April 2, 1951 – May 30, 1952 | |

| Succeeded by | Gen. Matthew Ridgway |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 14, 1890 Denison, Texas |

| Died | March 28, 1969 (aged 78) Washington, D.C. |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Mamie Doud Eisenhower |

| Alma mater | U.S. Military Academy, West Point |

| Occupation | Soldier (General of the Army) |

| Signature | |

Dwight David Eisenhower, born David Dwight Eisenhower (October 14 1890 – March 28 1969), nicknamed "Ike", was a five-star General in the United States Army and U.S. politician, who served as the thirty-fourth President of the United States (1953–1961). During the Second World War, he served as Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Europe, with responsibility for planning and supervising the successful invasion of France and Germany in 1944-45. In 1951, he became the first supreme commander of NATO.[1]

Eisenhower was elected the 34th President as a Republican, serving for two terms. As President, he oversaw the cease-fire of the Korean War, kept up the pressure on the Soviet Union during the Cold War, made nuclear weapons a higher defense priority, launched the Space Race, enlarged the Social Security program, and began the Interstate Highway System.

Early life and family

Eisenhower (historically "Eisenhauer") was born David Dwight Eisenhower in Denison, Texas.[2] He was the first U.S. President born in Texas. Eisenhower was the third of seven sons born to David Jacob Eisenhower and Ida Elizabeth Stover. He was named David Dwight and was called Dwight. Later, the order of his given names was switched (according to the staff at the Eisenhower Library and Museum, the name switch occurred upon Eisenhower's matriculation at West Point). Hans Nicolas Eisenhauer and his family emigrated from Karlsbrunn (Saarland), Germany to Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1741. The family settled in Abilene, Kansas in 1892. Eisenhower's father was a college-educated engineer.[3] Eisenhower graduated from Abilene High School in 1909.[4]

Eisenhower married Mamie Geneva Doud (1896–1979) of Denver, Colorado on July 1 1916. The couple had two sons. Doud Dwight Eisenhower was born September 24, 1917, and was nicknamed "Icky" by his parents, but died of scarlet fever on January 2, 1921, at the age of three.[5] John Sheldon David Doud Eisenhower was born the following year on August 3, 1922; John grew up to serve in the United States Army (retiring as a brigadier general from the Army reserve), became an author, and served as U.S. Ambassador to Belgium from 1969 to 1971. John's son, David Eisenhower, after whom Camp David is named, married Richard Nixon's daughter Julie in 1968.

Religion

David Jacob Eisenhower's family arrived in the United States in 1741 when Hans Nicholas Eisenhauer emigrated from Odenwald, Germany. Eisenhower's mother, Ida E. Eisenhower, previously a member of the River Brethren, joined the Watchtower Society (now more commonly known as Jehovah's Witnesses) in 1895, when Eisenhower was 4 or 5 years old.[citation needed] The Eisenhower home served as the local meeting hall from 1896 to 1915.

Jehovah’s Witnesses are opposed to killing or any doctrines such as militarism; Eisenhower's ties to the group were weakened when he joined the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York in 1911. By 1915, the home no longer served as the meeting hall. All the men in the household abandoned the Witnesses as adults, and some even hid their previous affiliation.[6][7] However, on his death in 1942, Eisenhower's father was given his funeral rites as though he remained a Jehovah's Witness, and Eisenhower's mother continued as an active Jehovah's Witness until her death. Despite their differences in religious beliefs, Eisenhower enjoyed a close relationship with his mother throughout her lifetime.

Eisenhower was baptized, confirmed, and became a communicant in the Presbyterian church in a single ceremony on February 1 1953, just 12 days after his first inauguration.[8] He is the only president known to have pursued these rites while in office. Eisenhower was instrumental in the addition of the words "under God" to the Pledge of Allegiance in 1954, and the 1956 adoption of "In God We Trust" as the motto of the US, and its 1957 introduction on paper currency. In his retirement years, he was a member of the Gettysburg Presbyterian Church.[9] The chapel at his presidential library is intentionally inter-denominational.

Education

Dwight D. Eisenhower (and his six brothers) attended Abilene High School in Abilene, Kansas; Dwight graduated with the class of 1909.[4] He then took a job as a night foreman at the Belle Springs Creamery.[10]

After Dwight worked for two years to support his brother Edgar's college education, a friend urged him to apply to the Naval Academy. Though Eisenhower passed the entrance exam, he was beyond the age of eligibility for admission to the Naval Academy.[11]

Kansas Senator Joseph L. Bristow recommended Dwight for an appointment to the Military Academy in 1911, which he received.[11] Eisenhower graduated in the upper half[12] of the class of 1915.[13]

Early military career

Eisenhower enrolled at the United States Military Academy at West Point in June 1911. His parents were against militarism, but did not object to his entering West Point because they supported his education. Eisenhower was a strong athlete. In 1912, a spectacular Eisenhower touchdown won praise from the sports reporter of the New York Herald, and he even managed, with the help of a linebacker partner, to tackle the legendary Jim Thorpe. In the very next week, however, his promising sports career came to a quick and painful end — he injured his knee quite severely when he was tackled around the ankles.[14]

Eisenhower graduated in 1915. He served with the infantry until 1918 at various camps in Texas and Georgia. During World War I, Eisenhower became the #3 leader of the new tank corps and rose to temporary Lieutenant Colonel in the National Army. He spent the war training tank crews in Pennsylvania and never saw combat. After the war, Eisenhower reverted to his regular rank of captain (and was promoted to major a few days later) before assuming duties at Camp Meade, Maryland, where he remained until 1922. His interest in tank warfare was strengthened by many conversations with George S. Patton and other senior tank leaders; however their ideas on tank warfare were strongly discouraged by superiors.[15]

Eisenhower became executive officer to General Fox Conner in the Panama Canal Zone, where he served until 1924. Under Conner's tutelage, he studied military history and theory (including Karl von Clausewitz's On War), and later cited Conner's enormous influence on his military thinking. In 1925-26, he attended the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and then served as a battalion commander at Fort Benning, Georgia until 1927.

During the late 1920s and early 1930s Eisenhower's career in the peacetime Army stagnated; many of his friends resigned for high paying business jobs. He was assigned to the American Battle Monuments Commission, directed by General John J. Pershing, then to the Army War College, and then served as executive officer to General George V. Mosely, Assistant Secretary of War, from 1929 to 1933. He then served as chief military aide to General Douglas MacArthur, Army Chief of Staff, until 1935, when he accompanied MacArthur to the Philippines, where he served as assistant military adviser to the Philippine government. It is sometimes said that this assignment provided valuable preparation for handling the egos of Winston Churchill, George S. Patton and Bernard Law Montgomery during World War II. Eisenhower was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1936 after sixteen years as a major. He also learned to fly, although he was never rated as a military pilot. He made a solo flight over the Philippines in 1937.

Eisenhower returned to the U.S. in 1939 and held a series of staff positions in Washington, D.C., California and Texas. In June 1941, he was appointed Chief of Staff to General Walter Krueger, Commander of the 3rd Army, at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. He was promoted to brigadier general in September 1941. Although his administrative abilities had been noticed, on the eve of the U.S. entry into World War II he had never held an active command and was far from being considered as a potential commander of major operations.

World War II

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower was assigned to the General Staff in Washington, where he served until June 1942 with responsibility for creating the major war plans to defeat Japan and Germany. He was appointed Deputy Chief in charge of Pacific Defenses under the Chief of War Plans Division, General Leonard T. Gerow, and then succeeded Gerow as Chief of the War Plans Division. Then he was appointed Assistant Chief of Staff in charge of Operations Division under Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall. It was his close association with Marshall which finally brought Eisenhower to senior command positions. Marshall recognized his great organizational and administrative abilities.

In 1942, Eisenhower was appointed Commanding General, European Theater of Operations (ETOUSA) and was based in London. In November, he was also appointed Supreme Commander Allied (Expeditionary) Force of the North African Theater of Operations (NATOUSA) through the new operational Headquarters A(E)FHQ. The word "expeditionary" was dropped soon after his appointment for security reasons. In February 1943, his authority was extended as commander of AFHQ across the Mediterranean basin to include the British 8th Army, commanded by General Bernard Law Montgomery. The 8th Army had advanced across the Western Desert from the east and was ready for the start of the Tunisia Campaign. Eisenhower gained his fourth star and gave up command of ETOUSA to be commander of NATOUSA. After the capitulation of Axis forces in North Africa, Eisenhower remained in command of the renamed Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTO), keeping the operational title and continued in command of NATOUSA redesignated MTOUSA. In this position he oversaw the invasion of Sicily and the invasion of the Italian mainland.

In December 1943, it was announced that Eisenhower would be Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. In January 1944, he resumed command of ETOUSA and the following month was officially designated as the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), serving in a dual role until the end of hostilities in Europe in May 1945. In these positions he was charged with planning and carrying out the Allied assault on the coast of Normandy in June 1944 under the code name Operation Overlord, the liberation of western Europe and the invasion of Germany. A month after the Normandy D-Day landings on June 6 1944, the invasion of southern France took place, and control of the forces which took part in the southern invasion passed from the AFHQ to the SHAEF. From then until the end of the War in Europe on May 8 1945, Eisenhower through SHAEF had supreme command of all operational Allied forces2, and through his command of ETOUSA, administrative command of all U.S. forces, on the Western Front north of the Alps.

As recognition of his senior position in the Allied command, on December 20 1944, he was promoted to General of the Army equivalent to the rank of Field Marshal in most European armies. In this and the previous high commands he held, Eisenhower showed his great talents for leadership and diplomacy. Although he had never seen action himself, he won the respect of front-line commanders. He dealt skillfully with difficult subordinates such as Omar Bradley and Patton, and allies such as Winston Churchill, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery and General Charles de Gaulle. He had fundamental disagreements with Churchill and Montgomery over questions of strategy, but these rarely upset his relationships with them. He negotiated with Soviet Marshal Zhukov, and such was the confidence that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had in him, he sometimes worked directly with Stalin, much to the chagrin of the British High Command who disliked being bypassed. During the advance towards Berlin, he came to the conclusion that Allied forces would suffer an estimated of 100,000 casualties before taking the city.[citation needed] The Soviet Army sustained 80,000 casualties during the fighting in and around Berlin, the last large number of casualties suffered in the war against Nazism.[16]

It was never certain that Operation Overlord would succeed. The seriousness surrounding the entire decision, including the timing and the location of the Normandy invasion, might be summarized by a second shorter speech that Eisenhower wrote in advance, in case he needed it. In it, he states he would take full responsibility for catastrophic failure, should that be the final result. Long after the successful landings on D-Day and the BBC broadcast of Eisenhower's brief speech concerning them, the never-used second speech was found in a shirt pocket by an aide. It read:

Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.

Aftermath of World War II

Following the German unconditional surrender on May 8 1945, Eisenhower was appointed Military Governor of the U.S. Occupation Zone, based in Frankfurt am Main. Germany was divided into four Occupation Zones, one each for the U.S., Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. Upon full discovery of the death camps that were part of the Final Solution (Holocaust), he ordered camera crews to comprehensively document evidence of the atrocity so as to prevent any doubt of its occurrence. He made the decision to reclassify German prisoners of war (POWs) in U.S. custody as Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs), thus depriving them of the protection of the Geneva convention. As DEFs, their food rations could be lowered and they could be compelled to serve as unfree labor (see Eisenhower and German POWs). Eisenhower was an early supporter of the Morgenthau Plan to permanently remove Germany's industrial capacity to wage future wars. In November 1945 he approved the distribution of 1000 free copies of Morgenthau's book Germany is Our Problem, which promoted and described the plan in detail, to American military officials in occupied Germany. Historian Stephen Ambrose draws the conclusion that, despite Eisenhower's later claims that the act was not an endorsement of the Morgenthau plan, Eisenhower both approved of the plan and had previously given Morgenthau at least some of his ideas on how Germany should be treated.[17] He also incorporated officials from Morgenthau's Treasury into the army of occupation. These were commonly called "Morgenthau boys" for their zeal in interpreting the occupation directive JCS 1067, which had been heavily influenced by Morgenthau and his plan, as strictly as possible.[18]

Eisenhower served as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army from 1945-48. In December 1950, he was named Supreme Commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and given operational command of NATO forces in Europe. Eisenhower retired from active service on May 31 1952, upon entering politics. He wrote Crusade in Europe, widely regarded as one of the finest U.S. military memoirs. During this period Eisenhower served as President of Columbia University from 1948 until 1953, though he was on leave from the university while he served as NATO commander.

After his many wartime successes, General Eisenhower returned to the U.S. a great hero. He was unusual for a military hero in that he never saw the front line in his life. The nearest that he came to being under enemy fire was in 1944 when a German fighter strafed the ground while he was inspecting troops in Normandy. Eisenhower dove for cover like everyone else and after the plane flew off, a British brigadier helped him up and seemed very relieved that he was not hurt. When Eisenhower thanked him for his solicitude, the brigadier deflated him by explaining that "my concern was that you should not be injured in my sector". This incident formed part of Eisenhower's fund of funny stories that he would tell now and again.

Not long after his return, a "Draft Eisenhower" movement in the Republican party persuaded him to declare his candidacy in the 1952 presidential election to counter the candidacy of isolationist Senator Robert Taft. (Eisenhower had been courted by both parties in 1948 and had declined to run then.) Eisenhower defeated Taft for the nomination but came to an agreement that Taft would stay out of foreign affairs while Eisenhower followed a conservative domestic policy. Eisenhower's campaign was a crusade against the Truman administration's policies regarding "Korea, Communism and Corruption" and was also noted for the simple but effective phrase "I Like Ike." Eisenhower promised to go to Korea himself and end the war and maintain both a strong NATO abroad against Communism and a corruption-free frugal administration at home. He and his running mate Richard Nixon, whose daughter later married Eisenhower's grandson David, defeated Democrats Adlai Stevenson and John Sparkman in a landslide, marking the first Republican return to the White House in 20 years. Eisenhower was the only general to serve as President in the 20th century.

Presidency 1953-1961

Interstate Highway System

One of Eisenhower's most enduring achievements as President was championing and signing the bill that authorized the Interstate Highway System in 1956. He justified the project through the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 as essential to American security during the Cold War. It was believed that large cities would be targets in a possible future war, and the highways were designed to evacuate them and allow the military to move in.

Eisenhower's goal to create improved highways was influenced by his involvement in the U.S. Army's 1919 Transcontinental Motor Convoy. He was assigned as an observer for the mission, which involved sending a convoy of U.S. Army vehicles coast to coast.[19] His subsequent experience with German autobahns during World War II convinced him of the benefits of an Interstate Highway System.[20]

Dynamic Conservatism

Throughout his presidency, Eisenhower preached a doctrine of Dynamic Conservatism.

Although he maintained a conservative economic policy, he continued all the major New Deal programs still in operation, especially Social Security. He expanded its programs and rolled them into a new cabinet-level agency, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, while extending benefits to an additional 10 million workers. His cabinet, consisting of several corporate executives and one labor leader, was dubbed by one journalist, "Eight millionaires and a plumber."

Eisenhower was extremely popular, winning his second term in 1956 with 457 of 531 votes in the Electoral College, and 57.6% of the popular vote.

Eisenhower Doctrine

After the Suez Crisis, the United States became the protector of most Western interests in the Middle East. As a result, Eisenhower proclaimed the "Eisenhower Doctrine" in January 1957. In relation to the Middle East, the U.S. would be "prepared to use armed force...[to counter] aggression from any country controlled by international communism." On July 15 1958, he sent just under 15,000 soldiers to Lebanon (a combined force of Army and Marine Corps) as part of Operation Blue Bat, a non-combat peace keeping mission to stabilize the pro-Western government. They left in the following October.

In addition, Eisenhower explored the option of supporting the French colonial forces in Vietnam who were fighting an independence insurrection there. However, Chief of Staff Matthew Ridgway dissuaded the President from intervening by presenting a comprehensive estimate of the massive military deployment that would be necessary.

Civil Rights

Eisenhower supported the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka U.S. Supreme Court decision, in which segregated ("separate but equal") schools were ruled to be unconstitutional. The very next day he told District of Columbia officials to make Washington a model for the rest of the country in integrating black and white public school children.[21] He proposed to Congress the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960 and signed those acts into law. Although both Acts were weaker than subsequent civil rights legislation, they constituted the first significant civil rights acts since the 1870s.

The "Little Rock Nine" incident of 1957 involved state refusal to honor a federal court order to integrate the schools. Eisenhower placed the Arkansas National Guard under federal control and sent Army troops to escort nine black students into an all-white public school; this integration did not occur without violence, and Eisenhower and Arkansas governor Orval Faubus engaged in tense arguments.

Supreme Court appointments

Eisenhower appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Earl Warren 1953

- John Marshall Harlan II 1954

- William J. Brennan 1956

- Charles Evans Whittaker 1957

- Potter Stewart 1958

States admitted to the Union

Post-presidency

In 1961, Eisenhower became the first U.S. president to be "constitutionally forced" from office, having served the maximum two terms allowed by the 22nd Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (amendment was ratified in 1951---before Eisenhower took office--but the amendment stipulated that the president at that time, Harry Truman, would not be held to the amendment).

In the 1960 election to choose his successor, Eisenhower endorsed his own Vice President, Republican Richard Nixon against Democrat John F. Kennedy. However, he only campaigned for Nixon in the campaign's final days and even did Nixon some harm when asked by reporters on TV to list one of Nixon's policy ideas he had adopted, replying "give me a week, I might think of one, I don't remember". Kennedy's campaign used the quote in one of their campaign commercials. Nixon lost narrowly to Kennedy.

On January 17 1961, Eisenhower gave his final televised Address to the Nation from the Oval Office. In his farewell speech to the nation, Eisenhower raised the issue of the Cold War and role of the U.S. armed forces. He described the Cold War saying: "We face a hostile ideology global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose and insidious in method..." and warned about what he saw as unjustified government spending proposals and continued with a warning that "we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex... Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together."

After Eisenhower left office, his reputation declined and he was seen as having been a "do-nothing" President. This was partly because of the contrast between Eisenhower and his young activist successor, John F. Kennedy, but also because of his reluctance not only to support the civil rights movement to the degree that more liberal individuals would have preferred, but also to stop McCarthyism, even though he opposed McCarthy's tactics and claims.[22] Such omissions were held against him during the liberal climate of the 1960s and 1970s. Since that time, however, Eisenhower's reputation has risen because of his non-partisan nature, his wartime leadership, his action in Arkansas and an increasing appreciation of how difficult it is today to maintain a prolonged peace. In recent surveys of historians, Eisenhower often is ranked in the top 10 among all US Presidents.

Eisenhower retired to the place where he and Mamie had spent much of their post-war time, a working farm adjacent to the battlefield at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The Gettysburg farm is a National Historic Site [1]. In retirement, he did not completely retreat from political life; he spoke at the 1964 Republican National Convention and appeared with Barry Goldwater in a Republican campaign commercial from Gettysburg.[23]

Because of legal issues related to holding a military rank while in a civilian office, Eisenhower resigned his permanent commission as General of the Army before entering the office of President of the United States. Upon completion of his Presidential term, his commission on the retired list was reactivated and Eisenhower again was commissioned a five-star general in the United States Army.

Eisenhower died at 12:25 p.m. on March 28 1969, at Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington D.C., of congestive heart failure. He lies alongside his wife and their first child, who died in childhood, in a small chapel called the Place of Meditation, at the Eisenhower Presidential Library, located in Abilene. His state funeral was unique because it was presided over by Richard Nixon, who was Vice President under Eisenhower and was serving as President of the United States.[24]

Tributes and memorials

Eisenhower's picture was on the dollar coin from 1971 to 1978. Nearly 700 million of the copper-nickel clad coins were minted for general circulation, and far smaller numbers of uncirculated and proof issues (in both copper-nickel and 40% silver varieties) were produced for collectors. He reappeared on a commemorative silver dollar issued in 1990, celebrating the 100th anniversary of his birth, which with a double image of him showed his two roles, as both a soldier and a statesman. As part of the Presidential $1 Coin Program, Eisenhower will be featured on a gold dollar coin in 2015.

He is remembered for ending the Korean War. USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, the second Nimitz-class supercarrier, was named in his honor.

The Eisenhower Expressway (Interstate 290), a 30-mile (48 km) long expressway in the Chicago area, was renamed after him.

The British A4 class steam locomotive No. 4496 (renumbered 60008) Golden Shuttle was renamed Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1946. It is preserved at the National Railroad Museum in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

Eisenhower College was a small, liberal arts college chartered in Seneca Falls, New York in 1965, with classes beginning in 1968. Financial problems forced the school to fall under the management of the Rochester Institute of Technology in 1979. Its last class graduated in 1982.

The Eisenhower Medical Center in Rancho Mirage, California was named after the President in 1971.

The Dwight D. Eisenhower Army Medical Center, located at Fort Gordon near Augusta, Georgia, was named in his honor.[25]

In February 1971, Dwight D. Eisenhower School of Freehold Township, New Jersey was officially opened.[26]

The Eisenhower Tunnel was completed in 1979; it conveys westbound traffic on I-70 through the Continental Divide, 60 miles (97 km) west of Denver, Colorado.

In 1983, The Eisenhower Institute was founded in Washington, D.C., as a policy institute to advance Eisenhower's intellectual and leadership legacies.

In 1999, the United States Congress created the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial Commission, which is in the planning stages of creating an enduring national memorial in Washington, D.C., across the street from the National Air and Space Museum on the National Mall.

A county park in East Meadow, New York (Long Island) is named in his honor.[27] In addition, Eisenhower State Park on Lake Texoma near his birthplace of Denison is named in his honor; his actual birthplace is currently operated by the State of Texas as Eisenhower Birthplace State Historic Site.

Many public high schools and middle schools in the U.S. are named after Eisenhower.

There is a Mount Eisenhower in the Presidential Range of the White Mountains in New Hampshire.

Awards and decorations

United States awards

In Order of Precedence

- Army Distinguished Service Medal with four oak leaf clusters

- Navy Distinguished Service Medal

- Legion of Merit

- Mexican Border Service Medal

- World War I Victory Medal

- American Defense Service Medal

- American Campaign Medal

- European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with one silver and four bronze service stars

- World War II Victory Medal

- Army of Occupation Medal with "Germany" clasp

- National Defense Service Medal (2 awards)

He was also an honorary member of the Boy Scouts of America's Tom Kita Chara Lodge #96.

International awards

List of citations bestowed by other countries.[28]

- Argentinian Order of the Liberator San Martin, Great Cross

- Belgian Order of Léopold

- Belgian Croix de Guerre/Belgisch Oorlogskruis

- Brazil Campaign Medal

- Brazil War Medal

- Brazilian Order of Military Merit, Grand Cross

- Brazilian Order of Aeronautical Merit, Grand Cross

- Brazilian National Order of the Southern Cross

- British Order of the Bath, Knight Grand Cross

- British Order of Merit

- British Africa Star with "8" and "1" numerical devices.

- Chilean Chief Commander of the Order of Merit

- Chinese Order of Yun Hui, Grand Cordon

- Chinese Order of Yun Fei, Grand Cordon

- Czechoslovakian Order of the White Lion

- Czechoslovakian Golden Star of Victory

- Danish Order of the Elephant

- Ecuadorian Star of Abdon Calderon

- Egyptian Order of Ismal, Grand Cordon

- Ethiopian Order of Solomon

- French Croix de Guerre

- French Legion of Honor

- French Order of Liberation

- French Military Medal

- Italy: Military Order of Italy, Knight Grand Cross

- Italy: Order of Malta

- Greek Order of George I with swords

- Guatemalan Cross of Military Merit, First Class

- Haitian Order of Honor and Merit, Grand Cross

- Luxembourg Medal of Merit

- Luxembourg War Cross

- Mexican Order of the Aztec Eagle, First Class

- Mexican Medal of Civic Merit

- Mexican Order of Military Merit

- Moroccan Order of Ouissam Alaouite

- Netherlands Order of the Dutch Lion, Grand Cross

- Norwegian Order of St. Olav

- Pakistanian Order of Pakistan, Nisham, First Class

- Panama Order of Vasco Nunez de Balboa, Grand Cross

- Panama Order of Manuel Amador Guerrero, Grand Master (collar grade)

- Philippines Distinguished Service Star

- Philippines Shield of Honor Medal, Chief Commander

- Philippines Order of Sikatuna, Raja (First Class)

- Polish Cross of Grunwald

- Polish Order of Polonia Restituta

- Polish Virtuti Militari

- Soviet Order of Suvorov

- Soviet Order of Victory

- Tunisian Order of Nichan Iftikhar, Gand Cordon

Other honors

- Eisenhower's name was given to a variety of streets, avenues, etc., in cities around the world, including Paris, France.

- In December 1999, Eisenhower was listed on Gallup's List of Most Widely Admired People of the 20th Century.

See also

- Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower

- Mamie Eisenhower, wife of Dwight D. Eisenhower

- Atoms for Peace, a speech to the U.N. General Assembly in December 1953

- Eisenhower National Historic Site

- Eisenhower Presidential Center

- Historical rankings of United States Presidents

- History of the United States (1945-1964)

- Kay Summersby

- Military-industrial complex, a term made popular by Eisenhower

- Mount Eisenhower

- People to People Student Ambassador Program

- German Americans

Footnotes

- ^ "Supreme commander", Encyclopædia Britannica, Dwight D. Eisenhower article, p. 3 of 6. URL retrieved on January 21 2007.

- ^ "Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower", Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Center, accessed August 7, 2007

- ^ Growing up, Ike and his brothers were all very competitive and loved sports. When he was fourteen, Ike received an infection in his leg that threatened to spread to his stomach. It kept him bedridden for months and the doctor recommended amputation more than once—Ike, barely conscious at times, steadfastly refused to have his leg amputated and his family respected his wishes. Ambrose (1983), p.as -14

- ^ a b "Eisenhower Genealogy". Eisenhower Presidential Center. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ^ Lawrence Berger-Knorr, The Pennsylvania Relations of Dwight D. Eisenhower, p8

- ^ Bergman, Jerry, Ph.D. Northwest State Community College. "Why President Eisenhower Hid His Jehovah's Witness Upbringing". edited version of a paper published in the JW Research Journal, vol. 6, #2, July-Dec., 1999. URL retrieved on April 29 2007.

- ^ Eisenhower Library holdings re Jehovah's Witnesses.

- ^ "Eisenhower Became Communicant". Eisenhower Presidential Trivia. Eisenhower Presidential Center. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ^ www.gettysburg.com Gettysburg Presbyterian Church. URL retrieved on April 29 2007.

- ^ "Eisenhower: Soldier of Peace", Time. April 4 1969. Page 3 of 10. URL retrieved on January 5 2007.

- ^ a b "Biography: DDE", Dwight D. Eisenhower Foundation. URL retrieved on December 21 2006.

- ^ "Timeline Biography". Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library. URL retrieved on December 21 2006.

- ^ "Dwight David Eisenhower". Presidents of the United States. Internet Public Library. URL retrieved on December 21 2006.

- ^ © Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial Commission, Washington, D.C., 2005

- ^ Sixsmith, ibid, p.6

- ^ D'Este (2002) pp 694-96; Stephen E. Ambrose, Eisenhower and Berlin, 1945: The Decision to Halt at the Elbe (2000)

- ^ Stephen Ambrose, Eisenhower: Soldier, General of the Army, President-Elect (1893-1952), New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983, p. 422.

- ^ Vladimir Petrov, Money and conquest; allied occupation currencies in World War II. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press (1967) pp. 228-229

- ^ Lippman, David H. The Last Week - The Road to War World War II Plus 55. Chapter 8, Part 1. URL retrieved on January 9 2007.

- ^ "Interstate Highway System", The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- ^ Eisenhower (1963) p. 230; Parmet 438; Eisenhower is purported to have regretted his 1953 appointment of California Governor Earl Warren as Chief Justice of the United States, but no reliable evidence exists. Ibid. 439

- ^ The Presidents - pbs.org

- ^ Web reference

- ^ US Army website

- ^ History of Eisenhower Army Medical Center. URL retrieved on February 20 2007.

- ^ "Eisenhower Middle School History". URL retrieved on January 21 2007.

- ^ "Eisenhower Park". Nassau County Department of Parks, Recreation and Museums. URL retrieved on January 22 2007.

- ^ Eisenhower Decorations & Awards - Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Center

Bibliography

Military career

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Eisenhower: Soldier, General of the Army, President-Elect, 1890-1952 (1983);

- D'Este, Carlo. Eisenhower: A Soldier's Life (2002), military biography to 1945

- Eisenhower, David. Eisenhower at War 1943-1945 (1986), detailed study by his grandson

- Irish, Kerry E. "Apt Pupil: Dwight Eisenhower and the 1930 Industrial Mobilization Plan," The Journal of Military History 70.1 (2006) 31-61 online in Project Muse.

- Pogue, Forrest C. The Supreme Command (1996) official Army history of SHAEF

- Sixsmith, E.K.G. Eisenhower, His Life and Campaigns (1973), military

- Russell Weigley. Eisenhower's Lieutenants. Indiana University Press, 1981. Ike's dealings with his key generals in WW2

Civilian career

- Albertson, Dean, ed. Eisenhower as President (1963).

- Alexander, Charles C. Holding the Line: The Eisenhower Era, 1952-1961 (1975).

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Eisenhower: Soldier, General of the Army, President-Elect, 1890-1952 (1983); Eisenhower. The President (1984); one volume edition titled Eisenhower: Soldier and President (2003). Standard biography.

- Bowie, Robert R. and Richard H. Immerman; Waging Peace: How Eisenhower Shaped an Enduring Cold War Strategy, Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Damms, Richard V. The Eisenhower Presidency, 1953-1961 (2002).

- David Paul T. (ed.), Presidential Nominating Politics in 1952. 5 vols., Johns Hopkins Press, 1954.

- Divine, Robert A. Eisenhower and the Cold War (1981).

- Greenstein, Fred I. The Hidden-Hand Presidency: Eisenhower as Leader (1991).

- Harris, Douglas B. "Dwight Eisenhower and the New Deal: The Politics of Preemption" Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 27, 1997.

- Harris, Seymour E. The Economics of the Political Parties, with Special Attention to Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy (1962).

- Krieg, Joann P. ed. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Soldier, President, Statesman (1987). 24 essays by scholars.

- McAuliffe, Mary S. "Eisenhower, the President", Journal of American History 68 (1981), pp. 625-632.

- Medhurst, Martin J. Dwight D. Eisenhower: Strategic Communicator Greenwood Press, 1993.

- Pach, Chester J. and Elmo Richardson. Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower (1991). Standard scholarly survey.

- Parmet, Herbert S. Eisenhower and the American Crusades (1972). Scholarly biography of post 1945 years.

Primary sources

- Boyle, Peter G., ed. The Churchill-Eisenhower Correspondence, 1953-1955 University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. Crusade in Europe (1948), his war memoirs.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. Mandate for Change, 1953-1956 (1963).

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. Waging Peace (1965), presidency 1956-1960.

- Eisenhower Papers 21 volume scholarly edition; complete for 1940-1961.

- Summersby, Kay. Eisenhower was my boss (1948) New York: Prentice Hall; (1949) Dell paperback.

Media

Template:Multi-video start Template:Multi-video item Template:Multi-video end

External links

- Extensive essay on Dwight D. Eisenhower (with shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs)

- Full audio of Eisenhower speeches via the Miller Center of Public Affairs (UVa)

- Eisenhower's Secret White House Recordings via the Miller Center of Public Affairs (UVa)

- Audio clips of Eisenhower's speeches

- Dwight David Eisenhower biography

- Eisenhower Chronology World History Database

- Eisenhower Home and Tomb

- Essay: Why the Eisenhower administration embraced nuclear weapons (PDF)

- Farewell Address (Wikisource)

- Guardians of Freedom - 50th Anniversary of Operation Arkansas, by ARMY.MIL

- First Inaugural Address

- Original Document: D-Day Statement from Dwight D. Eisenhower

- Second Inaugural Address

- Spartacus Educational Biography

- The Arms of Dwight David Eisenhower

- The Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial Commission

- The Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum

- The Last Salute: Civil and Military Funeral, 1921-1969, CHAPTER XXIX, Former President Dwight D. Eisenhower, State Funeral, 28 March-2 April 1969 by B. C. Mossman and M. W. Stark

- The Presidential Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower (searchable online)

- White House biography

- Works by Dwight D. Eisenhower at Project Gutenberg

- Presidents of the United States

- Republican Party (United States) presidential nominees

- United States Army Chiefs of Staff

- Supreme Allied Commanders

- United States Army generals

- American military personnel of World War II

- Operation Overlord people

- People of the Korean War

- Cold War leaders

- History of the United States (1945–1964)

- American military personnel of World War I

- United States military governors

- American anti-communists

- United States Military Academy alumni

- Army Black Knights football players

- Presidents of Columbia University

- Time magazine Persons of the Year

- Recipients of Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of Virtuti Militari

- Recipients of Polonia Restituta

- Companions of the Liberation

- Légion d'honneur recipients

- People from Kansas

- People from Texas

- People from Pennsylvania

- German-American politicians

- Deaths from cardiovascular disease

- American 5 star officers

- 1890 births

- 1969 deaths

- Former Jehovah's Witnesses