Lille

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

Lille | |

|---|---|

Grand' place, Lille city centre. | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Hauts-de-France |

| Department | Nord |

| Arrondissement | Lille |

| Intercommunality | European Metropolis of Lille |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2014-2020) | Martine Aubry (PS) |

| Area 1 | 34.8 km2 (13.4 sq mi) |

| • Urban (2009) | 442.5 km2 (170.9 sq mi) |

| • Metro (2007) | 7,200 km2 (2,800 sq mi) |

| Population (2012) | 228,652 |

| • Rank | 10th in France |

| • Density | 6,600/km2 (17,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban (2009[1]) | 1,015,744 |

| • Urban density | 2,300/km2 (5,900/sq mi) |

| • Metro (2007[2]) | 3,800,000 |

| • Metro density | 530/km2 (1,400/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 59350 /59000, 59800 |

| Website | www |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Lille (French pronunciation: [lil] ; Dutch: Rijsel [ˈrɛi̯səl]) is a city in the north of France. It is the principal city of the Lille Métropole. Lille is situated in French Flanders, on the Deûle River, near France's border with Belgium. It is the capital of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie region and the prefecture of the Nord department.

The city of Lille, to which the previously independent town of Lomme was annexed on 27 February 2000, had a population of 226,827 as recorded by the 2009 census.[3] However, Lille Métropole, which also includes Roubaix, Tourcoing and numerous suburban communities, had a population of 1,091,438. The Eurometropolis Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai, which also includes the Belgian cities of Kortrijk, Tournai and Mouscron, had 2,155,161 residents in 2008.[4][5] It is the fourth largest urban area in France after Paris, Lyon, and Marseille.

History

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled History of Lille. (Discuss) (November 2015) |

Origin of the city

Archeological digs seem to show the area as inhabited by as early as 2000 BC,[citation needed] most notably in the modern-day quartiers of Fives, Wazemmes, and Old Lille. The original inhabitants of this region were the Gauls, such as the Menapians, the Morins, the Atrebates, and the Nervians, who were followed by Germanic peoples: the Saxons, the Frisians and the Franks.

The legend of "Lydéric and Phinaert" puts the foundation of the city of Lille at 640. In the 8th century, the language of Old Low Franconian was spoken here, as attested by toponymic research. Lille's Dutch name is Rijsel, which comes from ter ijsel (at the island). The French equivalent has the same meaning: Lille comes from l'île (the island).

From 830 until around 910, the Vikings invaded Flanders. After the destruction caused by Norman and Magyar invasion, the eastern part of the region was ruled by various local princes.

The first mention of the town dates from 1066: apud Insulam (Latin for "at the island"). At the time, it was controlled by the County of Flanders, as were the regional cities (the Roman cities Boulogne, Arras, Cambrai as well as the Carolingian cities Valenciennes, Saint-Omer, Ghent and Bruges). The County of Flanders thus extended to the left bank of the Scheldt, one of the richest and most prosperous regions of Europe.

Middle Ages

A notable local in this period was Évrard, who lived in the 9th century and participated in many of the day's political and military affairs. There was an important Battle of Lille in 1054.

From the 12th century, the fame of the Lille cloth fair began to grow. In 1144 Saint-Sauveur parish was formed, which would give its name to the modern-day quartier Saint-Sauveur.

The counts of Flanders, Boulogne, and Hainaut came together with England and East Frankia and tried to regain territory taken by Philip II of France following Henry II of England's death, a war that ended with the French victory at Bouvines in 1214. Infante Ferdinand, Count of Flanders was imprisoned and the county fell into dispute: it would be his wife, Jeanne, Countess of Flanders and Constantinople, who ruled the city. She was said to be well loved by the residents of Lille, who by that time numbered 10,000.

In 1225, the street performer and juggler Bertrand Cordel, doubtlessly encouraged by local lords, tried to pass himself off as Baldwin I of Constantinople (the father of Jeanne of Flanders), who had disappeared at the battle of Adrianople. He pushed the kingdoms of Flanders and Hainaut towards sedition against Jeanne in order to recover his land. She called her cousin, Louis VIII ("The Lion"). He unmasked the imposter, whom Countess Jeanne quickly had hanged. In 1226 the King agreed to free Infante Ferdinand, Count of Flanders. Count Ferrand died in 1233, and his daughter Marie soon after. In 1235, Jeanne granted a city charter by which city governors would be chosen each All Saint's Day by four commissioners chosen by the ruler. On 6 February 1236, she founded the Countess's Hospital (Hospice Comtesse), which remains one of the most beautiful buildings in Old Lille. It was in her honour that the hospital of the Regional Medical University of Lille was named "Jeanne of Flanders Hospital" in the 20th century.

The Countess died in 1244 in the Abbey of Marquette, leaving no heirs. The rule of Flanders and Hainaut thus fell to her sister, Margaret II, Countess of Flanders, then to Margaret's son, Guy of Dampierre. Lille fell under the rule of France from 1304 to 1369, after the Franco-Flemish War (1297-1305).

The county of Flanders fell to the Duchy of Burgundy next, after the 1369 marriage of Margaret III, Countess of Flanders, and Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. Lille thus became one of the three capitals of said Duchy, along with Brussels and Dijon. By 1445, Lille counted some 25,000 residents. Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, was even more powerful than the King of France, and made Lille an administrative and financial capital.

On 17 February 1454, one year after the taking of Constantinople by the Turks, Philip the Good organised a Pantagruelian banquet at his Lille palace, the still-celebrated "Feast of the Pheasant". There the Duke and his court undertook an oath to Christianity.

In 1477, at the death of the last duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, Mary of Burgundy married Maximilian of Austria, who thus became Count of Flanders. At the end of the reign of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Spanish Flanders fell to his eldest son, and thus under the rule of Philip II of Spain, King of Spain. The city remained under Spanish rule until the reign of Philip IV of Spain.

Early modern era

The 16th century was marked by the outbreak of the Plague, a boom in the regional textile industry, and the Protestant revolts.

Calvinism first appeared in the area in 1542; by 1555 the authorities were taking steps to suppress this form of Protestantism. In 1566 the countryside around Lille was affected by the Iconoclastic Fury.[6] In 1578, the Hurlus, a group of Protestant rebels, stormed the castle of the Counts of Mouscron. They were removed four months later by a Catholic Wallon regiment, after which they tried several times between 1581 and 1582 to take the city of Lille, all in vain. The Hurlus were notably held back by the legendary Jeanne Maillotte. At the same time (1581), at the call of Elizabeth I of England, the north of the Seventeen Provinces, having gained a Protestant majority, successfully revolted and formed the United Provinces. The war brought or exacerbated periods of famine and plague (the last in 1667–69).[7]

The first printer to set up shop in Lille was Antoine Tack in 1594. The 17th century saw the building of new institutions: an Irish College in 1610, a Jesuit college in 1611, an Augustinian college in 1622, almshouses or hospitals such as the Maison des Vieux hommes in 1624 and the Bonne et Forte Maison des Pauvres in 1661, and of a Mont-de-piété in 1626.[8]

Unsuccessful French attacks on the city were launched in 1641 and 1645.[7] In 1667, Louis XIV of France (the Sun King) successfully laid siege to Lille, resulting in it becoming French in 1668 under the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, provoking discontent among the citizens of the prosperous city. A number of important public works undertaken between 1667 and 1670, such as the Citadel (erected by Vauban), or the creation of the quartiers of Saint-André and la Madeleine, enabled the King to gradually gain the confidence of his new subjects in Lille, some of whom continued to feel Flemish, though they had always spoken the Romance Picard language.

For five years, from 1708 to 1713, the city was occupied by the Dutch, during the War of the Spanish Succession. Throughout the 18th century, Lille remained profoundly Catholic. It took little part in the French Revolution, though there were riots and the destruction of churches. In 1790, the city held its first municipal elections.

Post French Revolution

In 1792, in the aftermath of the French Revolution, the Austrians, then in the United Provinces, laid siege to Lille. The "Column of the Goddess", erected in 1842 in the "Grand-Place" (officially named Place du Général-de-Gaulle), is a tribute to the city's resistance, led by Mayor François André-Bonte. Although Austrian artillery destroyed many houses and the main church of the city, the city did not surrender and the Austrian army left after eight days.

The city continued to grow, and by 1800 held some 53,000 residents, leading to Lille becoming the county seat of the Nord départment in 1804. In 1846, a rail line connecting Paris and Lille was built. At the beginning of the 19th century, Napoleon I's continental blockade against the United Kingdom led to Lille's textile industry developing even more fully. The city was known for its cotton while the nearby towns of Roubaix and Tourcoing worked wool. Leisure activities were thoroughly organized in 1858 for the 80,000 inhabitants. Cabarets or taverns for the working class numbered 1300, or one for every three houses. At that time the city counted 63 drinking and singing clubs, 37 clubs for card players, 23 for bowling, 13 for skittles, and 18 for archery. The churches likewise have their social organizations. Each club had a long roster of officers, and a busy schedule of banquets festivals and competitions.[9] In 1853, Alexandre Desrousseaux composed his lullaby P'tit quinquin.

In 1858, Lille annexed the adjacent towns of Fives, Wazemmes, and Moulins. Lille's population was 158,000 in 1872, growing to over 200,000 by 1891. In 1896 Lille became the first city in France to be led by a socialist, Gustave Delory.

By 1912, Lille's population stood at 217,000. The city profited from the Industrial Revolution, particularly via coal and the steam engine. The entire region grew wealthy thanks to its mines and textile industry.

First World War

Between 4–13 October 1914, the troops in Lille were able to trick the enemy by convincing them that Lille possessed more artillery than was the case; in reality, the city had only a single cannon. Despite the deception, the German bombardments destroyed over 2,200 buildings and homes. When the Germans realised they had been tricked, they burned down an entire section of town, subsequently occupying the city. Because Lille was only 20 km from the battlefield, German troops passed through the city regularly on their way to and from the front. As a result, occupied Lille became a place both for the hospitalization and treatment of wounded soldiers as well as a place for soldiers' relaxation and entertainment. Many buildings, homes, and businesses were requisitioned to those ends.[10]

Lille was liberated by the Allies on 17 October 1918, when General Sir William Birdwood and his troops were welcomed by joyous crowds. The general was made an honorary citizen of the city of Lille on 28 October of that year.

Lille was also the hunting ground of World War I German flying Ace Max Immelmann who was nicknamed "the Eagle of Lille".

The Années Folles, the Great Depression, and the Popular Front

In July 1921, at the Pasteur Institute in Lille, Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin discovered the first anti-tuberculosis vaccine, known as BCG ("Bacille de Calmette et Guérin"). The Opéra de Lille, designed by Lille architect Louis M. Cordonnier, was dedicated in 1923.

From 1931 Lille felt the repercussions of the Great Depression, and by 1935 a third of the city's population lived in poverty. In 1936, the city's mayor, Roger Salengro, became Minister of the Interior of the Popular Front, eventually killing himself after right-wing groups led a slanderous campaign against him.

Second World War

During the Battle of France, Lille was besieged by German forces for several days. When Belgium was invaded, the citizens of Lille, still haunted by the events of the First World War, began to flee the city in large numbers. Lille was part of the zone under control of the German commander in Brussels, and was never controlled by the Vichy government in France. Lille was instead controlled under the military administration in Northern France. The départments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais (with the exception of the coast, notably Dunkirk) were, for the most part, liberated in five days, from 1–5 September 1944, by British, American, Canadian, and Polish troops. On 3 September, the German troops began to leave Lille, fearing the British, who were on their way from Brussels. The city was retaken with little resistance when the British tanks arrived. Rationing came to an end in 1947, and by 1948 normality had returned to Lille.

Post-war to the present

In 1967, the Chambers of Commerce of Lille, Roubaix and Tourcoing were joined, and in 1969 the Communauté urbaine de Lille (Lille urban community) was created, linking 87 communes with Lille.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, the region was faced with some problems after the decline of the coal, mining and textile industries. From the start of the 1980s, the city began to turn itself more towards the service sector.

In 1983, the VAL, the world's first automated rapid transit underground network, was opened. In 1993, a high-speed TGV train line was opened, connecting Paris with Lille in one hour. This, with the opening of the Channel Tunnel in 1994 and the arrival of the Eurostar train, put Lille at the centre of a triangle connecting Paris, London and Brussels.

Work on Euralille, an urban remodelling project, began in 1991. The Euralille Centre was opened in 1994, and the remodeled district is now full of parks and modern buildings containing offices, shops and apartments. In 1994 the "Grand Palais" was also opened.

Lille was elected European Capital of Culture in 2004,[11] along with the Italian city of Genoa.

Lille and Roubaix were impacted by the 2005 Riots which affected all of France's urban centres.

In 2007 and again in 2010, Lille was awarded the label "Internet City @@@@".

Climate

Lille can be described as having a temperate oceanic climate; summers do not reach high temperatures, but winters can fall below zero temperatures. Precipitation is above average year round.

The table below gives average temperatures and precipitation levels for the 1981-2010 reference period.

| Climate data for Lille (1981–2010 averages) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.7 (72.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

31.7 (89.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

36.1 (97.0) |

36.6 (97.9) |

33.8 (92.8) |

27.8 (82.0) |

20.1 (68.2) |

15.9 (60.6) |

36.6 (97.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

15.2 (59.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.4 (43.5) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.6 (38.5) |

4.1 (39.4) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.7 (49.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.6 (52.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

4.2 (39.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.2 (34.2) |

1.3 (34.3) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.7 (53.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

11.2 (52.2) |

8.1 (46.6) |

4.4 (39.9) |

1.9 (35.4) |

7.1 (44.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −19.5 (−3.1) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

0.0 (32.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

1.2 (34.2) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

−19.5 (−3.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 60.5 (2.38) |

47.4 (1.87) |

58.3 (2.30) |

50.7 (2.00) |

64.0 (2.52) |

64.6 (2.54) |

68.5 (2.70) |

62.8 (2.47) |

61.6 (2.43) |

66.2 (2.61) |

70.1 (2.76) |

67.8 (2.67) |

742.5 (29.23) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.7 | 9.6 | 11.4 | 10.1 | 10.6 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 12.6 | 11.3 | 127.4 |

| Average snowy days | 4.9 | 4.1 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 19.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 88 | 85 | 82 | 79 | 78 | 79 | 78 | 78 | 83 | 87 | 89 | 90 | 83 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 65.5 | 70.7 | 121.1 | 172.2 | 193.9 | 206.0 | 211.3 | 199.5 | 151.9 | 114.4 | 61.4 | 49.6 | 1,617.5 |

| Source 1: Meteo France[12][13] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Infoclimat.fr (humidity, snowy days 1961–1990)[14] | |||||||||||||

Economy

A former major mechanical, food industry and textile manufacturing centre as well as a retail and finance center, Lille forms the heart of a larger conurbation, regrouping Lille, Roubaix, Tourcoing and Villeneuve d'Ascq, which is France's 4th-largest urban conglomeration with a 1999 population of over 1.1 million.

Revenues and taxes

For centuries, Lille, a city of merchants, has displayed a wide range of incomes: great wealth and poverty have lived side by side, especially until the end of the 1800s. This contrast was noted by Victor Hugo in 1851 in his poem Les Châtiments: « Caves de Lille ! on meurt sous vos plafonds de pierre ! » ("Cellars of Lille! We die under your stone ceilings!")

Employment

Employment in Lille has switched over half a century from a predominant industry to tertiary activities and services. Services account for 91% of employment in 2006.

Employment in Lille-Hellemmes-Lomme from 1968 to 2006

| Business area | 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 340 | 240 | 144 | 116 | 175 | 216 |

| Industry and engineering | 51 900 | 43 500 | 34 588 | 22 406 | 15 351 | 13 958 |

| Tertiary activities | 91 992 | 103 790 | 107 916 | 114 992 | 122 736 | 136 881 |

| Total | 144 232 | 147 530 | 142 648 | 137 514 | 138 262 | 151 055 |

| Sources of data : [15] | ||||||

Employment per categories in 1968 and in 2006

| Farmers | Businesspersons, entrepreneurs |

Upper class | Middle class | Employees | Blue-collar worker | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | 2006 | 1968 | 2006 | 1968 | 2006 | 1968 | 2006 | 1968 | 2006 | 1968 | 2006 | |

| Lille | 0,1% | 0,0% | 7,8% | 3,2% | 7,5% | 20,2% | 16,7% | 30,0% | 33,1% | 32,8% | 34,9% | 13,8% |

| Greater Lille | 1,3% | 0,3% | 9,0% | 3,8% | 5,3% | 17,5% | 14,6% | 27,7% | 24,4% | 29,6% | 45,4% | 21,1% |

| France | 12,5% | 2,2% | 9,9% | 6,0% | 5,2% | 15,4% | 12,4% | 24,6% | 22,5% | 28,7% | 37,6% | 23,2% |

| Sources of data : INSEE[16] | ||||||||||||

Unemployment in active population from 1968 to 2006

| 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2006 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lille | 2,9% | 4,6% | 10,3% | 14,6% | 16,9% | 15,2% |

| Greater Lille | 2,4% | 3,8% | 8,8% | 12,4% | 14,3% | 13,2% |

| France | 2,1 % | 3,8 % | 7,4 % | 10,1 % | 11,7 % | 10,6 % |

| Sources of data : INSEE[17] | ||||||

Enterprises

In 2007, Lille hosts around 21,000 industry or service sites.

Enterprises as per 31 December 2007

| Number | Size category | Mean number of employees | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greater Lille | Lille | % Lille | None | 1 to 19 | 20 to 99 | 100 to 499 | 500+ | Lille | Greater | |

| Industries | 3 774 | 819 | 22% | 404 | 361 | 40 | 12 | 2 | 17 | 22 |

| Construction | 4 030 | 758 | 19% | 364 | 360 | 32 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 10 |

| Commerce | 13 578 | 4 265 | 31% | 2 243 | 1 926 | 83 | 13 | 0 | 7 | 11 |

| Transports | 1 649 | 407 | 25% | 196 | 182 | 23 | 5 | 1 | 32 | 26 |

| Finance | 2 144 | 692 | 32% | 282 | 340 | 51 | 17 | 2 | 21 | 18 |

| Real property | 5 123 | 1 771 | 35% | 1 159 | 587 | 23 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 4 |

| Business services | 12 519 | 4 087 | 33% | 2 656 | 1 249 | 149 | 27 | 6 | 15 | 17 |

| Services to consumers | 8 916 | 3 075 | 34% | 1 636 | 1 347 | 86 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 6 |

| Education and health | 11 311 | 3 217 | 28% | 2 184 | 765 | 195 | 58 | 15 | 43 | 31 |

| Administration | 4 404 | 1 770 | 40% | 1 187 | 456 | 80 | 34 | 13 | 59 | 48 |

| Total | 67 468 | 20 861 | 31% | 12 311 | 7 573 | 762 | 176 | 39 | 18 | 17 |

| Sources of data : INSEE[18] | ||||||||||

Main sights

Lille features an array of architectural styles with various amounts of Flemish influence, including the use of brown and red brick. In addition, many residential neighborhoods, especially in Greater Lille, consist of attached 2–3 story houses aligned in a row, with narrow gardens in the back. These architectural attributes, many uncommon in France, help make Lille a transition in France to neighboring Belgium, as well as nearby Netherlands and England, where the presence of brick, as well as row houses or the Terraced house is much more prominent.

Points of interest include

- Lille Cathedral (Basilique-cathédrale Notre-Dame-de-la-Treille)

- Citadel of Lille

- Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille

- Jardin botanique de la Faculté de Pharmacie

- Jardin botanique Nicolas Boulay

- Jardin des Plantes de Lille

La Braderie

Lille hosts an annual braderie on the first weekend in September.[19] Its origins are thought to date back to the twelfth century and between two and three million visitors are drawn into the city. It is one of the largest gatherings of France and the largest flea market in Europe.

Many of the roads in the inner city (including much of the old town) are closed and local shops, residents and traders set up stalls in the street.

Gallery

-

Column of the Goddess

-

Lille Grand Place. La Voix du Nord (newspaper offices)

-

Lille Grand Place

-

Théâtre Sébastopol

-

Lion d'or square

-

Porte de Roubaix

-

Rihour palace

-

Hôtels particuliers rue Négrier, Vieux-Lille

Transport

Public transport

The Lille Métropole has a mixed mode public transport system, which is considered one of the most modern in the whole of France. It comprises buses, trams and a driverless metro system, all of which are operated under the Transpole name. The Lille Metro is a VAL system (véhicule automatique léger = light automated vehicle) that opened on 16 May 1983, becoming the first automatic metro line in the world. The metro system has two lines, with a total length of 45 kilometres (28 miles) and 60 stations.[20] The tram system consists of two interurban tram lines, connecting central Lille to the nearby communities of Roubaix and Tourcoing, and has 45 stops. 68 urban bus routes cover the metropolis, 8 of which reach into Belgium.[21]

Railways

Lille is an important crossroads in the European high-speed rail network. It lies on the Eurostar line to London (1:20 hour journey). The French TGV network also puts it only 1 hour from Paris, 38 minutes from Brussels,[22] and connects to other major centres in France such as Marseille, Lyon, and Toulouse. Lille has two railway stations, which stand next door to one another: Lille-Europe station (Gare de Lille-Europe), which primarily serves high-speed trains and international services (Eurostar), and Lille-Flandres station (Gare de Lille-Flandres), which primarily serves lower speed regional trains and regional Belgian trains.

Highways

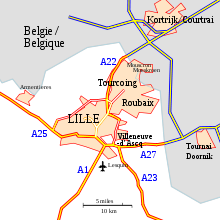

Five autoroutes pass by Lille, the densest confluence of highways in France after Paris:

- Autoroute A27 : Lille – Tournai – Brussels / Liège – Germany

- Autoroute A23 : Lille – Valenciennes

- Autoroute A1 : Lille – Arras – Paris / Reims – Lyon / Orléans / Le Havre

- Autoroute A25 : Lille – Dunkirk – Calais – England / North Belgium

- Autoroute A22 : Lille – Antwerp – Netherlands

A sixth one – the proposed A24 – will link Amiens to Lille if built, but there is opposition to its route.

Air traffic

Lille Lesquin International Airport is 15 minutes from the city centre by car (11 km). In terms of shipping, it ranks fourth, with almost 38,000 tonnes of freight which pass through each year. [citation needed] Its passenger traffic, around 1.2 millions a year in 2010, is modest due to the proximity to Brussels, Charleroi, and Paris-CDG airports. The airport mostly connects other French and European cities (some with low cost companies) as well as Mediterranean destinations.

Waterways

Lille is the third largest French river port after Paris and Strasbourg. The river Deûle is connected to regional waterways with over 680 km (423 mi) of navigable waters. The Deûle connects to Northern Europe via the River Scarpe and the River Scheldt (towards Belgium and the Netherlands), and internationally via the Lys River (to Dunkerque and Calais).

Shipping statistics

| Year | 1997 | 2000 | 2003 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Millions of tonnes | 5.56 | 6.68 | 7.30 |

| By river or sea | 8.00% | 8.25% | 13.33% |

| By rail | 6.28% | 4.13% | 2.89% |

| By road | 85.72% | 87.62% | 83.78% |

Education

With over 110,000 students, the metropolitan area of Lille is one of France's top student cities.

- With roots[23] back from 1562 to 1793 as University of Douai (Université de Douai), then as Université Impériale in 1808, the State Université of Lille (Université Lille Nord de France) was established in Lille in 1854 with Louis Pasteur as the first dean of its Faculty of Sciences. A school of medicine and an engineering school were also established in Lille in 1854. The Université de Lille was united as the association of existing public Faculties in 1887 and was split into three independent university campuses in 1970, including:

- Université de Lille I, also referred-to as Université des Sciences et Technologies de Lille (USTL),

- Université de Lille II with law, management, sports and medical faculties,

- Université Charles-de-Gaulle Lille III with humanities and social sciences courses.

- The Arts et Métiers ParisTech, an engineering graduate school of industrial and mechanical engineering, settled in Lille in 1900. This campus is one of the eight Teaching and Research Center (CER) of the school. Its creation was decided by Pierre-Nicolas Legrand de Lérant.

- Ecole Centrale de Lille is one of the five Centrale Graduate Schools of engineering in France; it was founded in Lille city in 1854, its graduate engineering education and research center was established as Institut industriel du Nord (IDN) in 1872, in 1968 it moved in a modern campus in Lille suburb.

- École nationale supérieure de chimie de Lille was established as Institut de chimie de Lille in 1894 supporting chemistry research as followers of Kuhlmann's breakthrough works in Lille.

- Skema Business School established in 1892 is ranked among the top business schools in France.

- École pour l'informatique et les nouvelles technologies settled in Lille in 2009.

- ESME-Sudria and E-Artsup settled in Lille in 2012.

- The ESA – École Supérieure des Affaires is a Business Management school established in Lille in 1990.

- IEP Sciences-Po Lille political studies institute was established in Lille in 1992.

- The Institut supérieur européen de formation par l'action is also located in Lille.

- The Institut supérieur européen de gestion group (ISEG Group) established in Lille in 1988.

- The European Doctoral College Lille Nord de France is headquartered in Lille Metropolis and includes 3,000 PhD Doctorate students supported by university research laboratories.

- The EDHEC Business School - located in nearby Roubaix - is one of the few Grandes École located outside the Paris Metropolitan Area. It is one of Europe's fastest rising business schools.

- The Université Catholique de Lille was founded in 1875. Today it has law, economics, medicine, physics faculties and schools. Among the most famous is Institut catholique d'arts et métiers (ICAM) founded in 1898, ranked 20th among engineering schools, with the specificity of graduating polyvalent engineers, Ecole des Hautes études d'ingénieur (HEI) a school of engineering founded in 1885 and offering 10 fields of specialization, École des hautes études commerciales du nord (EDHEC) founded in 1906, IÉSEG School Of Management founded in 1964 and Skema Business School[24] currently ranked within the top 5, the top 10 and top 15 business schools in France, respectively. In 1924 ESJ – a leading journalism school – was established.

Notable people from Lille

Writers

- Jean Prieur (1914-), writer and professor

Scientists and mathematicians

- Charles Barrois (1851–1939), geologist and palaeontologist

- Joseph Valentin Boussinesq (1842–1929), mathematician and physicist

- Albert Calmette (1863–1933) and Camille Guérin (1872–1961), scientists who discovered the antituberculosis vaccine

- Yvonne Choquet-Bruhat (1923–present), mathematician and physicist

- Jean Dieudonné (1906–1992), mathematician

- Paul Hallez (1846-1938), biologist

- Joseph Kampé de Fériet (1893–1982), researcher on fluid dynamics

- Charles Frédéric Kuhlmann, (1803–1881), chemist professor

- Gaspard Thémistocle Lestiboudois (1797-1876), naturalist

- Matthias de l'Obel (1538–1616), physician to King James I of England, scientist

- Henri Padé (1863–1953), mathematician

- Paul Painlevé (1863–1933), mathematician and politician

- Louis Pasteur, (1822–1895), micro-biologist

- Jean Baptiste Perrin (1870–1942), Nobel Prize in physics

Artists

- Renée Adorée (1898–1933), actress.

- Alfred-Pierre Agache (1843–1915), academic painter

- Alain de Lille (or Alanus ab Insulis) (c. 1128–1202), French theologian and poet

- Charles-Joseph Panckoucke, (1736–1788), intellectual and writer

- Ernest Joseph Bailly (1753-1823), painter

- Émile Bernard (1868–1941), neoimpressionist painter and friend of Paul Gauguin

- Édouard Chimot (d. 1959), artist and illustrator, editor of the Devambez illustrated art-editions

- Léon Danchin (1887–1938), animal artist and sculptor

- Alain Decaux (1925–), television presenter, minister, writer, and member of the Académie française

- Pierre Dubreuil (1872–1944), photographer

- Pierre De Geyter (1848–1932), textile worker who composed the music of The Internationale in Lille

- Raoul de Godewaersvelde (1928–1977), singer

- Gabriel Grovlez (1879–1944), pianist, conductor and composer who studied under Gabriel Fauré

- Alexandre Desrousseaux (1820–1892), songwriter

- Carolus-Duran (1837–1917), painter

- Julien Duvivier (1896–1967), director

- Yvonne Furneaux (1928–), actress

- Paul Gachet (1828–1909), doctor most famous for treating the painter Vincent van Gogh

- Kamini (1980– ), rap singer, hits success in 2006 in France with the funny "rural-rap" Marly-Gomont

- Édouard Lalo (1823–1892), composer

- Adélaïde Leroux (b. 1982), actress

- Serge Lutens (born 1942) photographer, make-up artist, interior and set designer, creator of perfumes and fashion designer

- Philippe Noiret (1930–2006), actor

- Benjamin Picard (1912-), artist

- Albert Samain (1858–1900), poet

- Ana Tijoux (1977–), rapper and singer whose family originally was from Chile

Politicians, professionals and military

- Lydéric, (620–?) legendary founder of the city

- Jeanne, Countess of Flanders, (1188/1200? –1244), Countess

- Jeanne Maillotte, (circa 1580), resistance fighter during the Hurlu attacks

- Pierre Joseph Duhem (1758-1807), physician and Montagnard

- Louis Faidherbe (1818–1889), general, founder of the city of Dakar and senator

- Achille Liénart (1884–1973), « cardinal des ouvriers »

- Charles de Gaulle (1890–1970), general, resistance fighter, President of France

- Roger Salengro (1890–1936), minister, deputy, and Mayor of Lille

- Augustin Laurent (1896–1990), minister, deputy, resistance fighter, and Mayor of Lille

- Madeleine Damerment (1917–1944), French Resistance fighter – Legion of Honor, Croix de Guerre, Médaille de la Résistance

- Pierre Mauroy (1928–2013), deputy, senator, Prime Minister of France, and Mayor of Lille

- Martine Aubry (1950–), deputy, minister, and Mayor of Lille

Sportspeople

- Maxime Agueh, footballer

- Sanaa Altama, footballer

- Alain Baclet, footballer

- Ismael Ehui, footballer

- Gael Kakuta, footballer

- Sarah Ousfar, basketball player

- Alain Raguel, footballer

- Jerry Vandam, footballer

- Raphael Varane, footballer

- Nabil Bentaleb, footballer

- Marcos Corbal Caballe, footballer and lover

Media and Sports

Local newspapers include Nord éclair and La Voix du Nord.

France's national public television network has a channel that focuses on the local area: France 3 Nord-Pas-de-Calais

The city's most major association football club, Lille OSC, currently plays in Ligue 1, the highest level of football in France. The club has won eight major national trophies and regularly feature in the UEFA Champions League and UEFA Europa League. In the 2010–11 season, Lille won the league and cup double.

It was in Lille that the 100th World Esperanto Congress took place, in 2015.

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Lille is partnered with:[25]

Cologne, Germany[25]

Cologne, Germany[25] Erfurt, Germany[25]

Erfurt, Germany[25] Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg[25]

Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg[25] Haifa, Israel[25]

Haifa, Israel[25] Kortrijk, Belgium[25]

Kortrijk, Belgium[25] Kharkiv, Ukraine[25]

Kharkiv, Ukraine[25] Leeds, United Kingdom[25][26]

Leeds, United Kingdom[25][26] Liège, Belgium[25]

Liège, Belgium[25] Nablus, Palestinian National Authority[25]

Nablus, Palestinian National Authority[25] Oujda, Morocco[25]

Oujda, Morocco[25] Rotterdam, Netherlands[25]

Rotterdam, Netherlands[25] Safed, Israel[25] (frozen)[27]

Safed, Israel[25] (frozen)[27] Saint-Louis, Senegal[25]

Saint-Louis, Senegal[25] Tlemcen, Algeria[25]

Tlemcen, Algeria[25] Tournai, Belgium[25]

Tournai, Belgium[25] Turin, Italy[25][28]

Turin, Italy[25][28] Valladolid, Spain[25]

Valladolid, Spain[25] Wrocław, Poland[25]

Wrocław, Poland[25] Buffalo, United States[29][Notes 1]

Buffalo, United States[29][Notes 1]

See also

Notes

- ^ But not according to the official website of Lille!

References

- ^ "Insee - Chiffres clés : Unité urbaine 2010 de Lille (partie française) (59702)". Paris: Insee (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques). Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "Insee - Population - L'Aire métropolitaine de Lille, un espace démographiquement hétérogène aux enjeux multiples". Paris: Insee (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques). Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "Insee - Chiffres clés : Commune de Lille (59350)". Paris: Insee (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques). 27 February 2000. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "EUROMÉTROPOLE : Territoire" (in French). Courtrai, Belgium: Agence de l’Eurométropole. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Eric Bocquet. "EUROMETROPOLIS : Eurometropolis Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai , the 1st european cross-bordrer metropolis" (in French). Courtrai, Belgium: Agence de l’Eurométropole. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Trenard (1981), p. 456.

- ^ a b Trenard (1981), p. 457.

- ^ Trenard (1981), pp. 456–457.

- ^ Theodore Zeldin, France, 1848-1945, vol. 2, Intellect, Taste and Anxiety (1977) pp 2:270-71.

- ^ Wallart, Claudine. Lille under German Rule. Remembrance Trails of the Great War. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Lille 2004 European Capital of Culture". mairie-lille.fr.

- ^ "Données climatiques de la station de Lille" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ "Climat Nord-Pas-de-Calais" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ "Normes et records 1961-1990: Lille-Lesquin (59) - altitude 47m" (in French). Infoclimat. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ "SecteurEmpLT-DonnéesHarmoniséesRP68-99" (in French). Paris: Insee (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques). 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ^ "CS-EmploisLT-DonnéesHarmoniséesRP68-99" (in French). Paris: Insee (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques). 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ^ "CS-ActivitéLR-DonnéesHarmoniséesRP68-99" (in French). Paris: Insee (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques). 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ^ "Caractéristiques des entreprises et établissements" (in French). Paris: Insee (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques). 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ^ "The September 'Braderie'". mairie-lille.fr.

- ^ "Public Transport". mairie-lille.fr.

- ^ "Travel & Transport". La mairie de Lille. Archived from the original on 31 January 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ "Coming by train". mairie-lille.fr.

- ^ Rapport L'Optimisation du réseau de formation initiale d'enseignement supérieur en région, rapport de M. Alain Lottin Au Conseil Economique et Social Régional Présenté lors de la séance plénière du 7 novembre 2006.

- ^ [1] Archived 2012-11-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Nos villes partenaires" (in French). Hôtel de Ville de Lille. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "La ville de Lille "met en veille" son jumelage avec Safed en Israël" (in French). Saint Ouen Cedex, France: Le Parisien. 7 October 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Pessotto, Lorenzo. "International Affairs - Twinnings and Agreements". International Affairs Service in cooperation with Servizio Telematico Pubblico. City of Torino. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ "Lille, Buffalo sister cities". Washington, USA: SisterCities International. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

Sources

- Codaccioni, Félix-Paul (1976). De l'inégalité sociale dans une grande ville industrielle, le drame de Lille de 1850 à 1914. Lille: Éditions Universitaires, Université de Lille 3. ISBN 2-85939-041-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - Collectif (1999). Lille, d'un millénaire à l'autre (Fayard ed.). ISBN 2-213-60456-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|trans_chapter=, and|month=(help) - Despature, Perrine (2001). Le Patrimoine des Communes du Nord (Flohic ed.). ISBN 2-84234-119-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|separator=,|trans_title=,|month=,|trans_chapter=,|laysummary=,|chapterurl=, and|lastauthoramp=(help) - Duhamel, Jean-Marie (2004). Lille, Traces d'histoire. Les patrimoines. La Voix du Nord. ISBN 2-84393-079-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|trans_chapter=, and|month=(help) - Gérard, Alain (1991). Les grandes heures de Lille. Perrin. ISBN 2-262-00743-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|separator=,|trans_title=,|month=,|trans_chapter=,|laysummary=,|chapterurl=, and|lastauthoramp=(help) - Legillon, Paulette; Dion, Jacqueline (1975). Lille : portrait d'une cité. Axial.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|trans_chapter=, and|month=(help) - Lottin, Alain (2003). Lille – D'Isla à Lille-Métropole. Histoire des villes du Nord. La Voix du Nord. ISBN 2-84393-072-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|separator=,|trans_title=,|month=,|trans_chapter=,|laysummary=,|chapterurl=, and|lastauthoramp=(help) - Maitrot, Eric; Cary, Sylvie (2007). Lille secret et insolite. Les Beaux Jours. ISBN 2-35179-011-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=,|trans_title=,|trans_chapter=, and|month=(help) - Marchand, Philippe (2003). Histoire de Lille. Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 2-87747-645-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=and|month=(help) - Monnet, Catherine (2004). Lille : portrait d'une ville. Jacques Marseille. ISBN 2-914967-02-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=and|month=(help) - Paris, Didier; Mons, Dominique (2009). Lille Métropole, Laboratoire du renouveau urbain. Parenthèses. ISBN 978-2-86364-223-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|separator=,|trans_title=,|month=,|trans_chapter=,|laysummary=,|chapterurl=, and|lastauthoramp=(help) - Pierrard, Pierre (1979). Lille, dix siècles d'histoire. Stock. ISBN 2-234-01135-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|trans_chapter=, and|month=(help) - Trenard, Louis (1981). Histoire de Lille de Charles Quint à la conquête française (1500–1715). Toulouse: Privat. ISBN 978-2708923812.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|trans_chapter=, and|month=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Versmée, Gwenaelle (2009). Lille méconnu. Jonglez. ISBN 2-915807-56-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|trans_chapter=, and|month=(help)

External links

- Lille The most Flemish of French cities - Official French website (in English)

- Official website Template:Fr

- European Capital of Culture 2004

- Template:Dmoz

- Proposal for Lille Expo 2017