Black Panther Party: Difference between revisions

→Conflict with law enforcement: a blog is not a reliable source |

→Origins: Restore sourced info |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

Newton and Seale worked at the North Oakland Neighborhood Anti-Poverty Center, where they also served on the advisory board. To combat [[police brutality]], the advisory board obtained 5,000 signatures in support of the City Council's setting up a police review board to review complaints. Newton was also taking classes at the City College and at [[San Francisco Law School]]. Both institutions were active in the North Oakland Center. Thus the pair had numerous connections with whom they talked about a new organization. Inspired by the success of the [[Lowndes County, Alabama#History|Lowndes County Freedom Organization]] and [[Stokely Carmichael]]'s calls for separate black political organizations,<ref>[http://www.blackpast.org/?q=aah/lowndes-county-freedom-organization Lowndes County Freedom Organization | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed<!--Bot-generated title-->]</ref> they wrote their initial platform statement, the [[Ten-Point Program]]. With the help of Huey's brother Melvin, they decided on a uniform of blue shirts, black pants, black leather jackets, black berets, and openly displayed loaded shotguns. (In his studies, Newton had discovered a California law that allowed carrying a loaded rifle or shotgun in public, as long as it was publicly displayed and pointed at no one.)<ref>For more on this, see Pearson 1994, page 109. The [[Mulford Act]] later revoked the right to openly bear arms.</ref> |

Newton and Seale worked at the North Oakland Neighborhood Anti-Poverty Center, where they also served on the advisory board. To combat [[police brutality]], the advisory board obtained 5,000 signatures in support of the City Council's setting up a police review board to review complaints. Newton was also taking classes at the City College and at [[San Francisco Law School]]. Both institutions were active in the North Oakland Center. Thus the pair had numerous connections with whom they talked about a new organization. Inspired by the success of the [[Lowndes County, Alabama#History|Lowndes County Freedom Organization]] and [[Stokely Carmichael]]'s calls for separate black political organizations,<ref>[http://www.blackpast.org/?q=aah/lowndes-county-freedom-organization Lowndes County Freedom Organization | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed<!--Bot-generated title-->]</ref> they wrote their initial platform statement, the [[Ten-Point Program]]. With the help of Huey's brother Melvin, they decided on a uniform of blue shirts, black pants, black leather jackets, black berets, and openly displayed loaded shotguns. (In his studies, Newton had discovered a California law that allowed carrying a loaded rifle or shotgun in public, as long as it was publicly displayed and pointed at no one.)<ref>For more on this, see Pearson 1994, page 109. The [[Mulford Act]] later revoked the right to openly bear arms.</ref> |

||

What became standard Black Panther discourse emerged from a long history of urban activism, social criticism and political struggle by African Americans. There is considerable debate about the impact that the Black Panther Party had on the greater society, or even their local environment. Author Jama Lazerow writes "As inheritors of the discipline, pride, and calm self-assurance preached by [[Malcolm X]], the Panthers became national heroes in African American communities by infusing abstract nationalism with street toughness—by joining the rhythms of black working-class youth culture to the interracial élan and effervescence of Bay Area New Left politics ... In 1966, the Panthers defined Oakland's ghetto as a territory, the police as interlopers, and the Panther mission as the defense of community. The Panthers' famous "policing the police" drew attention to the spatial remove that White Americans enjoyed from the state violence that had come to characterize life in black urban communities."<ref name="Lazerow, Jama 2006"/> In his book ''Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America'' journalist Hugh Pearson takes a more jaundiced view, linking Panther criminality and violence to worsening conditions in America's black ghettos as their influence spread nationwide.<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite book |last=Pearson |first=Hugh |title=In the Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America |year=1994 |publisher=Perseus Books |isbn=978-0-201-48341-3}}</ref> |

What became standard Black Panther discourse emerged from a long history of urban activism, social criticism and political struggle by African Americans. There is considerable debate about the impact that the Black Panther Party had on the greater society, or even their local environment. Author Jama Lazerow writes "As inheritors of the discipline, pride, and calm self-assurance preached by [[Malcolm X]], the Panthers became national heroes in African American communities by infusing abstract nationalism with street toughness—by joining the rhythms of black working-class youth culture to the interracial élan and effervescence of Bay Area New Left politics ... In 1966, the Panthers defined Oakland's ghetto as a territory, the police as interlopers, and the Panther mission as the defense of community. The Panthers' famous "policing the police" drew attention to the spatial remove that White Americans enjoyed from the state violence that had come to characterize life in black urban communities."<ref name="Lazerow, Jama 2006"/> In his book ''Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America'' journalist Hugh Pearson takes a more jaundiced view, linking Panther criminality and violence to worsening conditions in America's black ghettos as their influence spread nationwide.<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite book |last=Pearson |first=Hugh |title=In the Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America |year=1994 |publisher=Perseus Books |isbn=978-0-201-48341-3}}</ref> Similarly, journalist Kate Coleman writes regarding a 2003 Panther conference at Boston's Wheelock College, "If the Wheelock conference wanted to examine the real legacy of the Panthers, its participants should have pored over the cold statistics showing a spike in drive-by shooting deaths and gang warfare that took place in Oakland in the decade following the Panthers' demise. The Black Panther Party had so fetishized the gun as part of its mystique that young men in the ghetto felt incomplete without one.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://articles.latimes.com/2003/jun/22/opinion/op-coleman22 |title=Just a Pack of Predators - Los Angeles Times |publisher=Los Angeles Times |date=2003-06-22 |accessdate=2012-12-01}}</ref>...The Panther fetish of the gun, worshiped by impressionable young black males, maimed hundreds of black citizens in Oakland more surely than any bully cops."<ref>{{cite web |author=Kate Coleman |url=http://www.sfgate.com/crime/article/REVISIONISM-Guess-Who-s-Mything-Them-Now-The-2609696.php |title=REVISIONISM / Guess Who's Mything Them Now / The real Black Panthers were a bunch of thugs |publisher=SFGate |date=2003-06-15 |accessdate=2012-12-01}}</ref> |

||

== Evolving ideology, widening support == |

== Evolving ideology, widening support == |

||

Revision as of 17:23, 20 April 2013

This article's lead section may be too long. (January 2013) |

Template:Infobox Historical American Political Party

| This article is part of a series on |

| Socialism in the United States |

|---|

The Black Panther Party (originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense) was an African-American revolutionary socialist organization active in the United States from 1966 until 1982. The Black Panther Party achieved national and international notoriety through its involvement in the Black Power movement and U.S. politics of the 1960s and 1970s.[1]

Founded in Oakland, California by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale on October 15, 1966, the organization initially set forth a doctrine calling primarily for the protection of African-American neighborhoods from police brutality.[2] The leaders of the organization espoused socialist and Marxist doctrines; however, the Party's early black nationalist reputation attracted a diverse membership.[3] The Black Panther Party's objectives and philosophy expanded and evolved rapidly during the party's existence, making ideological consensus within the party difficult to achieve, and causing some prominent members to openly disagree with the views of the leaders.

The organization's official newspaper, The Black Panther, was first circulated in 1967. Also that year, the Black Panther Party marched on the California State Capitol in Sacramento in protest of a selective ban on weapons. By 1968, the party had expanded into many cities throughout the United States, among them, Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Newark, New Orleans, New York City, Omaha, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle and Washington, D.C.. Peak membership was near 10,000 by 1969, and their newspaper, under the editorial leadership of Eldridge Cleaver, had a circulation of 250,000.[4] The group created a Ten-Point Program, a document that called for "Land, Bread, Housing, Education, Clothing, Justice and Peace", as well as exemption from conscription for African-American men, among other demands.[5] With the Ten-Point program, "What We Want, What We Believe", the Black Panther Party expressed its economic and political grievances.[6]

Gaining national prominence, the Black Panther Party became an icon of the counterculture of the 1960s.[7] Ultimately, the Panthers condemned black nationalism as "black racism" and became more focused on socialism without racial exclusivity.[8] They instituted a variety of community social programs designed to alleviate poverty, improve health among inner city black communities, and soften the Party's public image.[9] The Black Panther Party's most widely known programs were its armed citizens' patrols to evaluate behavior of police officers and its Free Breakfast for Children program. However, the group's political goals were often overshadowed by their confrontational, militant, and violent tactics against police.[10]

Federal Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover called the party "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country,"[11] and he supervised an extensive program (COINTELPRO) of surveillance, infiltration, perjury, police harassment, assassination, and many other tactics designed to undermine Panther leadership, incriminate party members and drain the organization of resources and manpower. Through these tactics, Hoover hoped to diminish the Party's threat to the general power structure of the U.S., or even maintain its influence as a strong undercurrent.[12] Angela Davis, Ward Churchill, and others have alleged that federal, state and local law enforcement officials went to great lengths to discredit and destroy the organization, including assassination.[13][14][15] Black Panther Party membership reached a peak of 10,000 by early 1969, then suffered a series of contractions due to legal troubles, incarcerations, internal splits, expulsions and defections. Popular support for the Party declined further after reports appeared detailing the group's involvement in activities such as drug dealing and extortion schemes directed against Oakland merchants.[16] By 1972 most Panther activity centered around the national headquarters and a school in Oakland, where the party continued to influence local politics. Party contractions continued throughout the 1970s; by 1980 the Black Panther Party comprised just 27 members.[17]

Origins

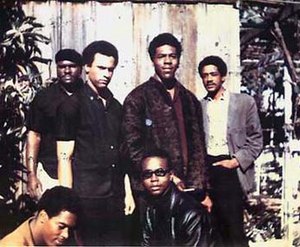

Top left to right: Elbert "Big Man" Howard, Huey P. Newton (Defense Minister), Sherwin Forte, Bobby Seale (Chairman)

Bottom: Reggie Forte and Little Bobby Hutton (Treasurer).

In 1966, Huey P. Newton was released from jail. With his friend Bobby Seale from Oakland City College, he joined a black power group called the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM). RAM had a chapter in Oakland and followed the writings of Robert F. Williams. Williams had been the president of the Monroe, North Carolina branch of the NAACP and later published a newsletter called The Crusader from Cuba, where he fled to escape kidnapping charges.[18]

Newton and Seale worked at the North Oakland Neighborhood Anti-Poverty Center, where they also served on the advisory board. To combat police brutality, the advisory board obtained 5,000 signatures in support of the City Council's setting up a police review board to review complaints. Newton was also taking classes at the City College and at San Francisco Law School. Both institutions were active in the North Oakland Center. Thus the pair had numerous connections with whom they talked about a new organization. Inspired by the success of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization and Stokely Carmichael's calls for separate black political organizations,[19] they wrote their initial platform statement, the Ten-Point Program. With the help of Huey's brother Melvin, they decided on a uniform of blue shirts, black pants, black leather jackets, black berets, and openly displayed loaded shotguns. (In his studies, Newton had discovered a California law that allowed carrying a loaded rifle or shotgun in public, as long as it was publicly displayed and pointed at no one.)[20]

What became standard Black Panther discourse emerged from a long history of urban activism, social criticism and political struggle by African Americans. There is considerable debate about the impact that the Black Panther Party had on the greater society, or even their local environment. Author Jama Lazerow writes "As inheritors of the discipline, pride, and calm self-assurance preached by Malcolm X, the Panthers became national heroes in African American communities by infusing abstract nationalism with street toughness—by joining the rhythms of black working-class youth culture to the interracial élan and effervescence of Bay Area New Left politics ... In 1966, the Panthers defined Oakland's ghetto as a territory, the police as interlopers, and the Panther mission as the defense of community. The Panthers' famous "policing the police" drew attention to the spatial remove that White Americans enjoyed from the state violence that had come to characterize life in black urban communities."[12] In his book Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America journalist Hugh Pearson takes a more jaundiced view, linking Panther criminality and violence to worsening conditions in America's black ghettos as their influence spread nationwide.[21] Similarly, journalist Kate Coleman writes regarding a 2003 Panther conference at Boston's Wheelock College, "If the Wheelock conference wanted to examine the real legacy of the Panthers, its participants should have pored over the cold statistics showing a spike in drive-by shooting deaths and gang warfare that took place in Oakland in the decade following the Panthers' demise. The Black Panther Party had so fetishized the gun as part of its mystique that young men in the ghetto felt incomplete without one.[22]...The Panther fetish of the gun, worshiped by impressionable young black males, maimed hundreds of black citizens in Oakland more surely than any bully cops."[23]

Evolving ideology, widening support

Awareness of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense grew rapidly after their May 2, 1967 protest at the California State Assembly.

- In May 1967, the Panthers invaded the State Assembly Chamber in Sacramento, guns in hand, in what appears to have been a publicity stunt. Still, they scared a lot of important people that day. At the time, the Panthers had almost no following. Now, (a year later) however, their leaders speak on invitation almost anywhere radicals gather, and many whites wear "Honkeys for Huey" buttons, supporting the fight to free Newton, who has been in jail since last Oct. 28 (1967) on the charge that he killed a policeman ..."[24]

In October 1967, Huey Newton was arrested for the murder of Oakland Police Officer John Frey, a murder he later admitted and pointed to with pride.[25] At the time, Newton claimed that he had been falsely accused, leading to the "Free Huey" campaign. On February 17, 1968, at the "Free Huey" birthday rally in the Oakland Auditorium, several Black Panther Party leaders spoke. H. Rap Brown, Black Panther Party Minister of Justice, declared:

Huey Newton is our only living revolutionary in this country today ... He has paid his dues. He has paid his dues. How many white folks did you kill today?[9][26]

The mostly black crowd erupted in applause. James Forman, Black Panther Party Minister of Foreign Affairs, followed with:

We must serve notice on our oppressors that we as a people are not going to be frightened by the attempted assassination of our leaders. For my assassination—and I'm the low man on the totem pole—I want 30 police stations blown up, one southern governor, two mayors, and 500 cops, dead. If they assassinate Brother Carmichael, Brother Brown ... Brother Seale, this price is tripled. And if Huey is not set free and dies, the sky is the limit![9]

Referring to the 1967–68 period, black historian Curtis Austin states: "During this period of development, black nationalism became part of the party's philosophy."[27] During the months following the "Free Huey" birthday rallies, one in Oakland and another in Los Angeles, the Party's violent, anti-white rhetoric attracted a huge following and Black Panther Party membership exploded.

Two days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., on April 6, 1968, seventeen-year-old Bobby Hutton joined Eldridge Cleaver, Black Panther Party Minister of Information, in what Cleaver later admitted was "an ambush" of the Oakland police.[28] Two officers were wounded, and Bobby Hutton was killed when officers opened fire, wounding Cleaver as well.[29]

After Hutton's death, Black Panther Party Chairman Bobby Seale and Kathleen Cleaver (Eldridge's wife) held a rally in New York City at the Fillmore East in support of Hutton and Cleaver. Playwright LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) joined them on stage before a mixed crowd of 2,000:

We want to become masters of our own destiny ... we want to build a black nation to benefit black people ... The white people who killed Bobby Hutton are the same white people sitting here.[30]

The crowd, including many whites, gave LeRoi Jones a standing ovation.

In 1968, the group shortened its name to the Black Panther Party and sought to focus directly on political action. Members were encouraged to carry guns and to defend themselves against violence. An influx of college students joined the group, which had consisted chiefly of "brothers off the block." This created some tension in the group. Some members were more interested in supporting the Panthers social programs, while others wanted to maintain their "street mentality". For many Panthers, the group was little more than a type of gang.[31]

Curtis Austin states that by late 1968, Black Panther Party ideology had evolved to the point where they began to reject black nationalism and became more a "revolutionary internationalist movement":

(The Party) dropped its wholesale attacks against whites and began to emphasize more of a class analysis of society. Its emphasis on Marxist-Leninist doctrine and its repeated espousal of Maoist statements signaled the group's transition from a revolutionary nationalist to a revolutionary internationalist movement. Every Party member had to study Mao Tse-tung's "Little Red Book" to advance his or her knowledge of peoples' struggle and the revolutionary process.[32]

Panther slogans and iconography spread. At the 1968 Summer Olympics, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two American medalists, gave the black power salute during the playing of the American national anthem. The International Olympic Committee banned them from the Olympic Games for life. Hollywood celebrity Jane Fonda publicly supported Huey Newton and the Black Panthers during the early 1970s. She and other Hollywood celebrities became involved in the Panthers' leftist programs. The Panthers attracted a wide variety of left-wing revolutionaries and political activists, including writer Jean Genet, former Ramparts magazine editor David Horowitz (who later became a major critic of what he describes as Panther criminality)[33] and left-wing lawyer Charles R. Garry, who acted as counsel in the Panthers' many legal battles.

Survival committees and coalitions were organized with several groups across the United States. Chief among these was the Rainbow Coalition formed by Fred Hampton and the Chicago Black Panthers. The Rainbow Coalition included the Young Lords, a Latino youth gang turned political under the leadership of Jose Cha Cha Jimenez.[34] It also included the Young Patriots, which was organized to support young, white migrants from the Appalachia region.[35]

Women and Womanism

At its beginnings, the Black Panther Party reclaimed black masculinity and traditional gender roles.[36]: 6 Several scholars consider the Party's stance of armed resistance highly masculine, with the use of guns and violence affirming proof of manhood.[37]: 2 In 1968, the Black Panther Party newspaper stated in several articles that the role of female Panthers was to "stand behind black men" and be supportive.[36]: 6

By 1969, the Black Panther Party newspaper officially stated that men and women are equal [36]: 2 and instructed male Panthers to treat female Party members as equals,[36]: 6 a drastic change from the idea of the female Panther as subordinate. That same year, Deputy Chairman Fred Hampton of the Illinois chapter conducted a meeting condemning sexism.[36]: 2 After 1969, the Party considered sexism counter-revolutionary.[36]: 6

The Black Panthers adopted a womanist ideology in consideration of the unique experiences of African-American women,[38]: 28 affirming that racism is more oppressive then sexism.[38]: 2 Womanism was a mix of black nationalism and the vindication of women,[38]: 20 putting race and community struggle before the gender issue.[38]: 8 Womanism posited that traditional feminism failed to include race and class struggle in its denunciation of male sexism [38]: 26 and was therefore part of white hegemony.[38]: 21 In opposition to some feminist viewpoints, womanism promoted a gender role point of view that men are not above women, but hold a different position in the home and community,[38]: 42 so men and women must work together for the preservation of African American culture and community.[38]: 27

From this point forward, the Black Panther Party newspaper portrayed women as revolutionaries, using the example of party members like Kathleen Cleaver, Angela Davis and Erika Huggins, all political, intelligent and attractive women.[36]: 10 The Black Panther Party newspaper often showed women as active participants in the armed self-defense movement, picturing them with children and guns as protectors of the home, the family and the community.[36]: 2

This had direct implications at every level for Black Panther women. From 1968 to the end of its publication in 1982, the head editors of the Black Panther Party newspaper were all women.[36]: 5 In 1970, approximately 40% to 70% of Party members were women,[36]: 8 and several chapters, like the Des Moines, Iowa and New Haven, Connecticut, were headed by women.[37]: 7

During the 1970s, recognizing the limited access poor women had to abortion, the Party officially supported women's reproductive rights, including abortion.[36]: 11 That same year, the Party condemned and opposed prostitution.[36]: 12

The Black Panther Party experienced significant problems in several chapters with sexism and gender oppression, particularly in the Oakland chapter where cases of sexual harassment and gender division were common.[39]: 5 When Oakland Panthers arrived to bolster the New York City Panther chapter after New York Twenty-one leaders were incarcerated, they displayed such chauvinistic attitudes towards New York Panther women that they had to be fended off at gunpoint.[40] Some Party leaders thought the fight for gender equality was a threat to men and a distraction from the struggle for racial equality.[36]: 5

In response, the Chicago and New York chapters, among others, established equal gender rights as a priority and tried to eradicate sexist attitudes.[37]: 13

By the time the Black Panther Party disbanded, official policy was to reprimand men who violated the rules of gender equality.[37]: 13

Rules

The Black Panther Party had a list of 26 rules that dictated their daily party work. They regulated their participants' use of drugs, alcohol, and their actions while they were working. Almost all of the rules had to do with only the actions of members while they were in an event or a meeting of the Black Panthers. The rules also said that members had to follow the Ten Point Program, and had to know it by heart. The final section of rules had to do with more of the leader's responsibilities, such as providing a first aid center for members of the Black Panthers.[41][42][43]

Ten Point Program

The original "Ten Point Program" from October, 1966 was as follows:[44][45]

1. We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our black Community.

- We believe that black people will not be free until we are able to determine our destiny.

2. We want full employment for our people.

- We believe that the federal government is responsible and obligated to give every man employment or a guaranteed income. We believe that if the white American businessmen will not give full employment, then the means of production should be taken from the businessmen and placed in the community so that the people of the community can organize and employ all of its people and give a high standard of living.

3. We want an end to the robbery by the white man of our black Community.

- We believe that this racist government has robbed us and now we are demanding the overdue debt of forty acres and two mules. Forty acres and two mules was promised 100 years ago as restitution for slave labor and mass murder of black people. We will accept the payment as currency which will be distributed to our many communities. The Germans are now aiding the Jews in Israel for the genocide of the Jewish people. The Germans murdered six million Jews. The American racist has taken part in the slaughter of over 50 million black people; therefore, we feel that this is a modest demand that we make.

4. We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings.

- We believe that if the white landlords will not give decent housing to our black community, then the housing and the land should be made into cooperatives so that our community, with government aid, can build and make decent housing for its people.

5. We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present-day society.

- We believe in an educational system that will give to our people a knowledge of self. If a man does not have knowledge of himself and his position in society and the world, then he has little chance to relate to anything else.

6. We want all black men to be exempt from military service.

- We believe that black people should not be forced to fight in the military service to defend a racist government that does not protect us. We will not fight and kill other people of color in the world who, like black people, are being victimized by the white racist government of America. We will protect ourselves from the force and violence of the racist police and the racist military, by whatever means necessary.

7. We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of black people.

- We believe we can end police brutality in our black community by organizing black self-defense groups that are dedicated to defending our black community from racist police oppression and brutality. The Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States gives a right to bear arms. We therefore believe that all black people should arm themselves for self defense.

8. We want freedom for all black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.

- We believe that all black people should be released from the many jails and prisons because they have not received a fair and impartial trial.

9. We want all black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their black communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

- We believe that the courts should follow the United States Constitution so that black people will receive fair trials. The 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution gives a man a right to be tried by his peer group. A peer is a person from a similar economic, social, religious, geographical, environmental, historical and racial background. To do this the court will be forced to select a jury from the black community from which the black defendant came. We have been, and are being tried by all-white juries that have no understanding of the "average reasoning man" of the black community.

10. We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace. And as our major political objective, a United Nations-supervised plebiscite to be held throughout the black colony in which only black colonial subjects will be allowed to participate for the purpose of determining the will of black people as to their national destiny.

- When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume, among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

- We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. That, to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that, whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly, all experience hath shown, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But, when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariable the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security.

Action

"This country is a nation of thieves. It stole everything it has, beginning with black people. The U.S. cannot justify its existence as the policeman of the world any longer. I do not want to be a part of the American pie. The American pie means raping South Africa, beating Vietnam, beating South America, raping the Philippines, raping every country you've been in. I don't want any of your blood money. I don't want to be part of that system. We must question whether or not we want this country to continue being the wealthiest country in the world at the price of raping everybody else."

— Stokely Carmichael, Honorary Prime Minister[46]

Survival programs

Inspired by Mao Zedong's advice to revolutionaries in The Little Red Book, Newton called on the Panthers to "serve the people" and to make "survival programs" a priority within its branches. The most famous of their programs was the Free Breakfast for Children Program, initially run out of an Oakland church.

Other survival programs were free services such as clothing distribution, classes on politics and economics, free medical clinics, lessons on self-defense and first aid, transportation to upstate prisons for family members of inmates, an emergency-response ambulance program, drug and alcohol rehabilitation, and testing for sickle-cell disease.[47]

The BPP also founded the "Intercommunal Youth Institute" in January 1971,[48] with the intent of demonstrating how black youth ought to be educated. Ericka Huggins was the director of the school and Regina Davis was an administrator.[49] The school was unique in that it didn't have grade levels but instead had different skill levels so an 11 year old could be in second-level English and fifth-level science.[49] Elaine Brown taught reading and writing to a group of 10 to 11 year olds deemed "uneducable" by the system.[50] As the school children were given free busing; breakfast, lunch, and dinner; books and school supplies; children were taken to have medical checkups; and many children were given free clothes.[51]

Political activities

The Party briefly merged with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, headed by Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture). In 1967, the party organized a march on the California state capitol to protest the state's attempt to outlaw carrying loaded weapons in public after the Panthers had begun exercising that right. Participants in the march carried rifles. In 1968, BPP Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver ran for Presidential office on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket. They were a big influence on the White Panther Party, that was tied to the Detroit/Ann Arbor band MC5 and their manager John Sinclair, author of the book Guitar Army that also promulgated a ten-point program.

Conflict with law enforcement

One of the central aims of the BPP was to stop abuse by local police departments. When the party was founded in 1966, only 16 of Oakland's 661 police officers were African American.[52] Accordingly, many members questioned the Department's objectivity and impartiality. This situation was not unique to Oakland, as most police departments in major cities did not have proportional membership by African Americans. Throughout the 1960s, race riots and civil unrest broke out in impoverished African-American communities subject to policing by disproportionately white police departments. The work and writings of Robert F. Williams, Monroe, North Carolina NAACP chapter president and author of Negroes with Guns, also influenced the BPP's tactics.

The BPP sought to oppose police brutality through neighborhood patrols (an approach since adopted by groups such as Copwatch). Police officers were often followed by armed Black Panthers who sought at times to aid African-Americans who were victims of police brutality and racial prejudice. Both Panthers and police died as a result of violent confrontations. By 1970, 34 Panthers had died as a result of police raids, shoot-outs and internal conflict.[53] Various police organizations claim the Black Panthers were responsible for the deaths of at least 15 law enforcement officers and the injuries of dozens more. During those years, juries found several BPP members guilty of violent crimes.[54]

On October 17, 1967, Oakland police officer John Frey was shot to death in an altercation with Huey P. Newton during a traffic stop. In the stop, Newton and backup officer Herbert Heanes also suffered gunshot wounds. Newton was arrested and charged with murder, which sparked a "free Huey" campaign, organized by Eldridge Cleaver to help Newton's legal defense. Newton was convicted of voluntary manslaughter, though after three years in prison he was released when his conviction was reversed on appeal. During later years Newton would boast to friend and sociobiologist Robert Trivers (one of the few whites who became a Party member during its waning years) that he had in fact murdered officer John Frey and never regretted it.[25]

In April 1968, the party was involved in a gun battle, in which Panther Bobby Hutton was killed. Cleaver, who was wounded, later said that he had led the Panther group on a deliberate ambush of the police officers, thus provoking the shoot-out.[28] In Chicago, on December 4, 1969, two Panthers were killed when the Chicago Police raided the home of Panther leader Fred Hampton. The raid had been orchestrated by the police in conjunction with the FBI; during this era the FBI was complicit in many local police actions. Hampton was shot and killed, as was Panther guard Mark Clark. Cook County State's Attorney Edward Hanrahan, his assistant and eight Chicago police officers were indicted by a federal grand jury over the raid, but the charges were later dismissed.[4][55]

Prominent Black Panther member H. Rap Brown is serving life imprisonment for the 2000 murder of Ricky Leon Kinchen, a Fulton County, Georgia sheriff's deputy, and the wounding of another officer in a gunbattle. Both officers were black.[56]

From 1966 to 1972, when the party was most active, several departments hired significantly more African-American police officers. During this time period, many African American police officers started to form organizations of their own to become more protective of the African American citizenry and to increase black representation on police forces.[57]

Conflict with COINTELPRO

In August 1967, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) instructed its program "COINTELPRO" to "neutralize" what the FBI called "black nationalist hate groups" and other dissident groups. In September 1968, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover described the Black Panthers as "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country."[58] By 1969, the Black Panthers and their allies had become primary COINTELPRO targets, singled out in 233 of the 295 authorized "Black Nationalist" COINTELPRO actions. The goals of the program were to prevent the unification of militant black nationalist groups and to weaken the power of their leaders, as well as to discredit the groups to reduce their support and growth. The initial targets included the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Revolutionary Action Movement and the Nation of Islam. Leaders who were targeted included the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, Maxwell Stanford and Elijah Muhammad.

Part of the FBI COINTELPRO actions were directed at creating and exploiting existing rivalries between black nationalist factions. One such attempt was to "intensify the degree of animosity" between the Black Panthers and the Blackstone Rangers, a Chicago street gang. They sent an anonymous letter to the Ranger's gang leader claiming that the Panthers were threatening his life, a letter whose intent was to induce "reprisals" against Panther leadership. In Southern California similar actions were taken to exacerbate a "gang war" between the Black Panther Party and a group called the US Organization. It was alleged that the FBI had sent a provocative letter to the US Organization in an attempt to increase existing antagonism between US and the Panthers.[59]

Controversy

Violence

From the beginning, the Black Panther Party's focus on militancy came with a reputation for violence.[60][61] The Panthers employed a California law that permitted carrying a loaded rifle or shotgun as long as it was publicly displayed and pointed at no one.[62] Carrying weapons openly and making threats against police officers, for example, chants like "The Revolution has come, it's time to pick up the gun. Off the pigs!",[63] helped create the Panthers' reputation as a violent organization.

On May 2, 1967, the California State Assembly Committee on Criminal Procedure was scheduled to convene to discuss what was known as the "Mulford Act", which would ban public displays of loaded firearms. Cleaver and Newton put together a plan to send a group of about 30 Panthers led by Seale from Oakland to Sacramento to protest the bill. The group entered the assembly carrying their weapons, an incident which was widely publicized, and which prompted police to arrest Seale and five others. The group pled guilty to misdemeanor charges of disrupting a legislative session.[64]

On October 17, 1967, Oakland police officer John Frey was shot to death in an altercation with Huey P. Newton during a traffic stop. In the stop, Newton and backup officer Herbert Heanes also suffered gunshot wounds. Newton was convicted of voluntary manslaughter at trial. This incident gained the party even wider recognition by the radical American left, and a "Free Huey" campaign ensued.[65] Newton was released after three years, when his conviction was reversed on appeal. During later years Newton would boast to sociobiologist Robert Trivers (one of the few whites who became a Party member during its waning years) that he had in fact murdered officer John Frey.[25]

On April 7, 1968, Panther Bobby Hutton was killed, and Cleaver was wounded in a shootout with the Oakland police. Two police officers were also shot. Although at the time Cleaver claimed that the police had ambushed them, Cleaver later admitted that he had led the Panther group on a deliberate ambush of the police officers, thus provoking the shoot-out.[28][29]

From the fall of 1967 through the end of 1970, nine police officers were killed and 56 were wounded, and ten Panther deaths and an unknown number of injuries resulted from confrontations. In 1969 alone, 348 Panthers were arrested for a variety of crimes.[66] On February 18, 1970 Albert Wayne Williams was shot by the Portland Police Bureau outside the Black Panther party headquarters in Portland, Oregon. Though his wounds put him in a critical condition, he made a full recovery.[67]

In May 1969, Black Panther Party members tortured and murdered Alex Rackley, a 19-year-old member of the New York chapter, because they suspected him of being a police informant. Three party officers — Warren Kimbro, George Sams, Jr., and Lonnie McLucas — later admitted taking part. Sams, who gave the order to shoot Rackley at the murder scene, turned state's evidence and testified that he had received orders personally from Bobby Seale to carry out the execution. After this betrayal, party supporters alleged that Sams was himself the informant and an agent provocateur employed by the FBI.[68] The case resulted in the New Haven, Connecticut Black Panther trials of 1970, memorialized in the courtroom sketches of Robert Templeton. The trial ended with a hung jury, and the prosecution chose not to seek another trial.

Violent conflict between the Panther chapter in LA and the US Organization, a rival group, resulted in shootings and beatings, and led to the murders of at least four Black Panther Party members. On January 17, 1969, Los Angeles Panther Captain Bunchy Carter and Deputy Minister John Huggins were killed in Campbell Hall on the UCLA campus, in a gun battle with members of the US Organization. Another shootout between the two groups on March 17 led to further injuries.

Murder of Betty van Patter

Black Panther bookkeeper Betty van Patter was murdered in 1974, and although this crime was never solved, the Panthers, according to the magazine Mother Jones, were "almost universally believed to be responsible".[69] David Horowitz became certain that Black Panther members were responsible and denounced the Panthers. When Huey Newton was shot dead 15 years later, Horowitz characterized Newton as a killer.[70] When Art Goldberg, a former colleague at Ramparts, alleged that Horowitz himself was responsible for the death of van Patter by recommending her for the position of Black Panther accountant, Horowitz counter-alleged that "the Panthers had killed more than a dozen people in the course of conducting extortion, prostitution and drug rackets in the Oakland ghetto." He said further that the organization was committed "to doctrines that are false and to causes that are demonstrably wrongheaded and even evil."[71] Former chairperson Elaine Brown also questioned Horowitz's motives in recommending van Patter to the Panthers; she suspected espionage.[72] Horowitz later became known for his conservative viewpoints and opposition to leftist thought.[73]

Decline

Significant disagreements among the Party's leaders over how to confront ideological differences led to a split within the party. Certain members felt the Black Panthers should participate in local government and social services, while others encouraged constant conflict with the police. For some of the Party's supporters, the separations among political action, criminal activity, social services, access to power, and grass-roots identity became confusing and contradictory as the Panthers' political momentum was bogged down in the criminal justice system. These (and other) disagreements led to a split.

Some Panther leaders, such as Huey Newton and David Hilliard, favored a focus on community service coupled with self-defense; others, such as Eldridge Cleaver, embraced a more confrontational strategy. Eldridge Cleaver deepened the schism in the party when he publicly criticized the Party for adopting a "reformist" rather than "revolutionary" agenda and called for Hilliard's removal. Cleaver was expelled from the Central Committee but went on to lead a splinter group, the Black Liberation Army, which had previously existed as an underground paramilitary wing of the Party.[74]

The Party eventually fell apart due to rising legal costs and internal disputes. In 1974, Huey Newton appointed Elaine Brown as the first Chairwoman of the Party. Under Brown's leadership, the Party became involved in organizing for more radical electoral campaigns, including Brown's 1975 unsuccessful run for Oakland City Council and Lionel Wilson's successful election as the first black mayor of Oakland.[75]

In addition to changing the Party's direction towards more involvement in the electoral arena, Brown also increased the influence of women Panthers by placing them in more visible roles within the previously male-dominated organization. In 1977, after Newton returned from Cuba and ordered the beating of a female Panther who organized many of the Party's social programs, Brown left the Party.[76]

Although many scholars and activists date the Party's downfall to the period before Brown became the leader, an increasingly smaller cadre of Panthers continued to exist through the 1970s. By 1980, Panther membership had dwindled to 27, and the Panther-sponsored school closed in 1982 after it became known that Newton was embezzling funds from the school to pay for his drug addiction.[75][77]

Legacy

Some critics have written that the Panthers' "romance with the gun" and their promotion of "gang mentality" was likely associated with the enormous increase in both black-on-black and black-on-white crime observed during later decades.[21][78] This increase occurred in the Panthers' hometown of Oakland, California, and in other cities nationwide.[79][80] Interviewed after he left the Black Panther Party, former Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver lamented that the legacy of the Panthers was at least partly one of disrespect for the law and indiscriminate violence. He acknowledged that, had his promotion of violent black militantism prevailed, it would have resulted in "a total bloodbath." Cleaver also lamented the abandonment of poor blacks by the black bourgeoisie and felt that black youth had been left without appropriate role models who could teach them to properly channel their militant spirit and their desire for justice.[81][82][83][84][85]

In October 2006, the Black Panther Party held a 40-year reunion in Oakland.[86]

In January 2007, a joint California state and Federal task force charged eight men with the August 29, 1971 murder of California police officer Sgt. John Young.[87] The defendants have been identified as former members of the Black Liberation Army. Two have been linked to the Black Panthers.[88] In 1975 a similar case was dismissed when a judge ruled that police gathered evidence through the use of torture.[89] On June 29, 2009 Herman Bell pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter in the death of Sgt. Young. In July 2009, charges were dropped against four of the accused: Ray Boudreaux, Henry W. Jones, Richard Brown and Harold Taylor. Also that month Jalil Muntaquim pleaded no contest to conspiracy to commit voluntary manslaughter becoming the second person to be convicted in this case.[90]

Since the 1990s, former Panther chief of staff David Hilliard has offered tours of sites in Oakland historically significant to the Black Panther Party.[91]

New Black Panther Party

In 1989, a group calling itself the "New Black Panther Party" was formed in Dallas, Texas. Ten years later, the NBPP became home to many former Nation of Islam members when the chairmanship was taken by Khalid Abdul Muhammad.

The Anti-Defamation League and The Southern Poverty Law Center include the New Black Panthers in lists of hate groups.[92] The Huey Newton Foundation, former chairman and co-founder Bobby Seale, and members of the original Black Panther Party have insisted that this New Black Panther Party is illegitimate and have strongly objected that there "is no new Black Panther Party".[93]

Naming influence

The Black Panthers have become an inspiration in name and tactics for various groups and movements since its existence:

- Gray Panthers, often used to refer to advocates for the rights of seniors (Gray Panthers in the United States, The Grays – Gray Panthers in Germany).

- Polynesian Panthers, an advocacy group for Māori people in New Zealand.

- Black Panthers, protest movement for the rights and social justice of Mizrahi Jews in Israel.

- White Panthers, used to refer to both the White Panther Party, a far-left, anti-racist, white American political party of the 1970s, as well as the White Panthers UK, an unaffiliated group started by Mick Farren.

- The Pink Panthers, used to refer to two LGBT rights organizations.

See also

International

Notes

- ^ , Curtis. Life of A Party. Crisis ; Sep/Oct2006, Vol. 113 Issue 5, p 30–37, 8p

- ^ "Black Panther Party". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 27, 2008.

- ^ Jessica Christina Harris. Revolutionary Black Nationalism: The Black Panther Party." Journal of Negro History, Vol. 85, No. 3 (Summer, 2000), pp. 162–174

- ^ a b Asante, Molefi K. (2005). Encyclopedia of Black Studies. Sage Publications Inc. pp. 135–137. ISBN 0-7619-2762-X.

- ^ Newton, Huey (October 15, 1966). "The Ten-Point Program". War Against the Panthers. Marxist.org. Retrieved June 5, 2006.

- ^ Lazerow, Jama; Yohuru R. Williams (2006). In Search of the Black Panther Party: New Perspectives on a Revolutionary Movement. Duke University: Duke University Press.pg. 46

- ^ Da Costa, Francisco. "The Black Panther Party". Retrieved June 5, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); External link in|authorlink= - ^ Seale, Bobby (1997). Seize the Time (Reprint ed.). Black Classic Press. pp. 23, 256, 383.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Pearson, Hugh (1994). In the Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America. Perseus Books. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-201-48341-3.

- ^ Westneat, Danny (June 1, 2005). "Reunion of Black Panthers stirs memories of aggression, activism". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 5, 2006.

- ^ "Hoover and the F.B.I." Luna Ray Films, LLC. PBS.org. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ a b Lazerow, Jama; Yohuru R. Williams (2006). In Search of the Black Panther Party: New Perspectives on a Revolutionary Movement. Duke University: Duke University Press.

- ^ The Angela Y. Davis Reader, p.11, "[P]olice, assisted by federal agents, had killed or assassinated over twenty black revolutionaries in the Black Panther Party." She cites on page 23 (citation # 26) Joanne Grant, Ward Churchill and Jim Van der Wall (see below), and Clayborne Carson. (Davis, Angela Y. The Angela Y. Davis Reader Blackwell Publishers (1998))

- ^ Ellis, Catherine; Smith, Stephen Drury, eds. (2010). Say It Loud!: Great Speeches on Civil Rights and African American Identity. New York: The New Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-59558-113-6.

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover ordered a wide-ranging counterintelligence program designed to 'expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize' the Black Panther Party and other black liberation groups. Enlisting local law enforcement agencies nationwide, the FBI 'declared war on the Panthers.'

- ^ Pearson, Hugh (1994). In the Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America. Perseus Books. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-0-201-48341-3.

- ^ Phillip Forner. The Black Panthers speak. 2002

- ^ Up Against the Wall, Curtis Austin, University of Arkansas Press, Fayettevill, 2006, p. 331

- ^ Barksdale, M. C. (1984). "Robert F. Williams and the Indigenous Civil Rights Movement in Monroe, North Carolina, 1961". The Journal of Negro History. 69 (2): 73–89. doi:10.2307/2717599. JSTOR 2717599.

- ^ Lowndes County Freedom Organization | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed

- ^ For more on this, see Pearson 1994, page 109. The Mulford Act later revoked the right to openly bear arms.

- ^ a b Pearson, Hugh (1994). In the Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America. Perseus Books. ISBN 978-0-201-48341-3.

- ^ "Just a Pack of Predators - Los Angeles Times". Los Angeles Times. June 22, 2003. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ Kate Coleman (June 15, 2003). "REVISIONISM / Guess Who's Mything Them Now / The real Black Panthers were a bunch of thugs". SFGate. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ Black Panthers: A Taut, Violent Drama St. Petersburg Times, Sunday, July 21, 1968 Special to the St. Petersburg Times from the New York Times

- ^ a b c Pearson 1994, pp. 3–4, 283–91

- ^ A year ago, James wrote ... (May 8, 2011). "H. Rap Brown & Stokely Carmichael in Oakland - DIVA". Diva.sfsu.edu. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ Up Against the Wall, Curtis Austin, University of Arkansas Press, Fayettevill, 2006, p. 80

- ^ a b c Kate Coleman, 1980, "Souled Out: Eldridge Cleaver Admits He Ambushed Those Cops." New West Magazine.

- ^ a b A discussion of the event can be found in Epstein, Edward Jay. The Black Panthers and the Police: A Pattern of Genocide? The New Yorker, (February 13, 1971) page 4 (Accessed here [1] June 8, 2007)

- ^ Pearson, Hugh (1994). In the Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America. Perseus Books. pp. 152–158. ISBN 978-0-201-48341-3.

- ^ Pearson 1994, page 175

- ^ Up Against the Wall, Curtis Austin, University of Arkansas Press, Fayettevill, 2006, p.170

- ^ FrontPage Magazine - Black Murder Inc

- ^ Lilia Fernandez, Latina/o Migration and Community Formation in Postwar Chicago: Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Gender and Politics, 1945–1975 (PhD Dissertation:2005)

- ^ Chuck Armsbury with the Patriot Party

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Linda Lumsden, Good Mothers With Guns: Framing Black Womanhood in the Black Panther, 1968–1980, J & MC Quartelry 86/4 (Winter 2009)

- ^ a b c d Jakobi Williams, "Don't no woman have to do nothing she don't want to do": Gender, Activism, and the Illinois Black Panther Party, Black Women, Gender & Families 6/2 (Fall 2012)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Janiece L. Blackmon, I Am Because We Are: Africana Womanism as a Vehicle of Empowerment and Influence", Blacksburg, VA, Virginia Polytechnic Institute (2008)

- ^ Regina Jennings, Africana Womanism in the Black Panthers Party: a Personal story, The Western Journal of Black Study 25/3 (2001)

- ^ Up Against the Wall, Curtis Austin, University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville, 2006, p. 300–01

- ^ The Rules Of the Panthers

- ^ Rules of the Black Panther Party

- ^ Black Panther Party Platform, Program, and Rules

- ^ Up Against the Wall, Curtis Austin, University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville, 2006, p. 353–55

- ^ Ten-Point Program and Platform of the Black Student Unions

- ^ Contemporary American Voices: Significant Speeches in American History: 1945 – present, by James Robertson Andrews & David Zarefsky, Longman, 1992, pg 105

- ^ Reunion of Black Panthers stirs memories of aggression, activism

- ^ Jones, Charles Earl. The Black Panther Reconsidered . Black Classic Press, 1998. Pg. 186

- ^ a b Brown, Elaine. A Taste of Power: A Black Woman's Story. 1st ed. New York: Pantheon Books, 1992. Pg.391

- ^ Brown, Elaine. A Taste of Power: A Black Woman's Story. 1st ed.. New York: Pantheon Books, 1992. Pg.392

- ^ Brown, Elaine. A Taste of Power: A Black Woman's Story. 1st ed.. New York: Pantheon Books, 1992. Pg.393

- ^ The Black Panthers by Jessica McElrath, published as a part of afroamhistory.about.com. Retrieved December 17, 2005.

- ^ from an interview with Kathleen Cleaver on May 7, 2002 published by the PBS program P.O.V. and being published in Introduction to Black Panther 1968: Photographs by Ruth-Marion Baruch and Pirkle Jones, (Greybull Press). Black Panthers 1968

- ^ The Officer Down Memorial

- ^ Michael Newton The encyclopedia of American law enforcement. 2007

- ^ End of Watch, Southern Poverty Law Center

- ^ The Anguish of Blacks in Blue

- ^ Stohl, Michael. The Politics of Terrorism CRC Press. Page 249

- ^ "Black Panther Party Pieces of History: 1966–1969". Itsabouttimebpp.com. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ Up Against the Wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party, Curtis Austin, University of Arkansas Press, Fayettevill, 2006, p.x-xxiii

- ^ Pearson 1994, pp 108–120

- ^ Pearson 1994, page 109

- ^ David Farber. The Age of Great Dreams: America in the 1960s. p. 207.

- ^ Pearson 1994, 129

- ^ Pearson 1994, page 3

- ^ Pearson 1994, page 206 discusses many of these events, including a partial list from the summer of 1968 through the end of 1970

- ^ The Oregonian Vol CX-34175

- ^ Edward Jay Epstein, The Black Panthers and the Police: A Pattern of Genocide?. New Yorker (February 13, 1971) [2]

- ^ Frank Browning. The Strange Journey of David Horowitz. Mother Jones Magazine. May 1987, pg 34

- ^ David Horowitz's claim about van Patten's death is often discussed on blogs. It is mentioned in an American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research book review of Horowitz's Radical Son: A Generational Odyssey called All's Left in the World. Horowitz's credibility as a critic of the left and especially of the Black Panther Party is called into question in Elaine Brown's The Condemnation of Little B: New Age Racism in America. Beacon Press (February 15, 2003) pg. 250–251.

- ^ Horowitz, David. "Who Killed Betty Van Patter?" December 13, 1999. Salon.com. [3]

- ^ Brown, Elaine. A Taste of Power: A Black Woman's Story. (New York: Doubleday, 1992).

- ^ Jones, Charles E. (1998) The Black Panther Party. Baltimore, MD: Black Classic Press.

- ^ Marxist Internet Archive: The Black Panther Party

- ^ a b Perkins, Margo V. Autobiography As Activism: Three Black Women of the Sixties. University Press of Mississippi. Jackson,2000. p. 5.

- ^ Brown, Elaine. A Taste of Power: A Black Woman's Story. Double Day. New York, 1992. pp. 444–450.

- ^ Pearson 1994, pp. 299

- ^ Published: November 14, 1997 (November 14, 1997). "Black Panther Legacy Includes Crime and Terror - New York Times". Nytimes.com. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Urban Strategies Council. Homicides In Oakland. 2006 Homicide Report: An Analysis of Homicides in Oakland from January through December, 2006. February 8, 2007. Accessed August 9, 2008.

- ^ Pacific News Service. Earl Ofari Hutchinson, August 13, 2002. Black on Black—Why Inner-City Murder Rates Are Soaring. Accessed August 9, 2008.

- ^ Undercover Black Man: Q&A: Eldridge Cleaver (pt. 1)

- ^ Republican Eldridge Cleaver-Charlie Rose Interview Part 1 - YouTube

- ^ Republican Eldridge Cleaver Interview with Charlie Rose Part 2 - YouTube

- ^ An Interview with Eldridge Cleaver - Reason Magazine

- ^ Interview With Eldridge Cleaver | The Two Nations Of Black America | FRONTLINE | PBS

- ^ Photos of the Black Panther Party, Oakland 2006

- ^ Ex-militants charged in S.F. police officer's '71 slaying at station (via SFGate)

- ^ Black Liberation Army tied to 1971 slaying (via USA Today)

- ^ 8 arrested in 1971 cop-killing tied to Black Panthers (via Los Angeles Times)

- ^ 2nd guilty plea in 1971 killing of S.F. officer (via SFGate)

- ^ DelVecchio, Rick (October 25, 1997). "Tour of Black Panther Sites: Former member shows how party grew in Oakland". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ "Hate Map | Southern Poverty Law Center". Splcenter.org. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ Dr. Huey P. Newton Foundation. "There Is No New Black Panther Party: An Open Letter From the Dr. Huey P. Newton Foundation".

References

Bibliography

- Austin, Curtis J. (2006). Up Against the Wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-827-5

- Alkebulan, Paul. Survival Pending Revolution: The History of the Black Panther Party. (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007)

- Brown, Elaine. (1993). A Taste of Power: A Black Woman's Story. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-679-41944-6

- Churchill, Ward and Vander Wall, Jim (1988). Agents of Repression: The FBI's Secret War Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement. South End Press. ISBN 0-89608-294-6

- Dooley, Brian. (1998). Black and Green: The Fight for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland and Black America. Pluto Press.

- Forbes, Flores A. (2006). Will You Die With Me? My Life and the Black Panther Party. Atria Books. ISBN 0-7434-8266-2

- Hilliard, David, and Cole, Lewis. (1993). This Side of Glory: The Autobiography of David Hilliard and the Story of the Black Panther Party. Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 0-316-36421-5

- Hughey, Matthew W. (2009). "Black Aesthetics and Panther Rhetoric – A Critical Decoding of Black Masculinity in The Black Panther, 1967–1980." Critical Sociology, 35(1): 29–56.

- Hughey, Matthew W. (2007). "The Pedagogy of Huey P. Newton: Critical Reflections on Education in his Writings and Speeches." Journal of Black Studies, 38(2): 209–231.

- Hughey, Matthew W. (2005)."The Sociology, Pedagogy, and Theology of Huey P. Newton: Toward a Radical Democratic Utopia." Western Journal of Black Studies, 29(3): 639–655.

- Joseph, Peniel E. (2006). Waiting 'Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-7539-9

- Lewis, John. (1998). Walking with the Wind. Simon and Schuster, p. 353. ISBN 0-684-81065-4

- Murch, Donna. "Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California," University of North Carolina, 2010 ISBN 978-0-8078-7113-3

- Ogbar, Jeffrey O. G. (2004). Black Power: Radical Politics and African American Identity. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8275-3

- Pearson, Hugh. (1994) The Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America De Capo Pres. ISBN 0-201-48341-6

- Phu, T. N. (2008). "Shooting the Movement: Black Panther Party Photography and African American Protest Traditions". Canadian Review of American Studies. 38 (1): 165–189. doi:10.3138/cras.38.1.165.

- Rhodes, Jane. "Framing the Black Panthers: The Spectacular Rise of a Black Power Icon," (New York: The New Press, 2007).

- Shames, Stephen. "The Black Panthers," Aperture, 2006. A photographic essay of the organization, allegedly suppressed due to Spiro Agnew's intervention in 1970.

- Street, Joe, "The Historiography of the Black Panther Party," Journal of American Studies (Cambridge), 44 (May 2010), 351–75.

- Swirski, Peter. "1960s The Return of the Black Panther: Irving Wallace's The Man." Ars Americana Ars Politica. Montreal, London: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-7735-3766-8

- Williams, Yohuru, "'Some Abstract Thing Called Freedom': Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Legacy of the Black Panther Party," OAH Magazine of History, 22 (July 2008), 16–21.

- Williams, Yohuru, "A Red Black and Green Liberation Jumpsuit, Roy Wilkins and the Conundrum of Black Power" in Joseph, "The Black Power Movement," 169–191.

- Williams, Yohuru, "The Black Panther Party: A Short Historiography for Teachers,"Organization of American History Magazine's Special Black Power Issue-- Volume 22, No 3 • July 2008

- Williams,Yohuru. "Black Politics White Power, Civil Rights, Black Power and the Black Panthers in New Haven," Blackwell Press, January, 2008. (originally published by Brandywine Press, 2000) ISBN 978-1-881089-60-5

- Williams, Yohuru and Lazerow, Jama, Eds. Liberated Territory: Toward a local history of the Black Panther Party," Duke University Press, 2009.ISBN 978-0-8223-4326-4

- Williams, Yohuru and Lazerow, Jama Eds,. In Search of the Black Panther Party: New Perspectives on a Revolutionary Movement," Duke University Press, 2006.ISBN 978-0-8223-3890-1

- Samson, Labobuha, The Time, Sonntagsausgabe, 2003,5,22 (c)

External links

- Seattle Black Panther Party History and Memory Project The largest collection of materials on any single chapter.

- BlackPanther.org official website according to the Dr. Huey P. Newton Foundation.

- FBI file on the BPP

- Incidents attributed to the Black Panthers at the START database

- Archives

- Black Panther Party

- Civil rights movement during the Lyndon B. Johnson Administration

- Anti-fascist organizations

- COINTELPRO targets

- Communism in the United States

- Defunct American political movements

- History of Oakland, California

- History of socialism

- Maoist organizations in the United States

- Political movements

- Political parties established in 1966

- Political parties of minorities

- Politics and race

- Politics of Oakland, California

- Crime in the San Francisco Bay Area