History of Russia: Difference between revisions

TylerBurden (talk | contribs) Reverting edit(s) by 115.240.194.54 (talk) to rev. 1223141996 by Betelgeuse X: Unexplained content removal (RW 16.1) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|History of the Russian Federation}} |

|||

{{History_of_Russia}} |

|||

{{redirect|Russian History||Russian History (disambiguation)}} |

|||

The '''history of Russia''' is essentially that of its many nationalities, each with a separate history and complex origins. The historical origins of [[Russia]] as a state are chiefly those of the [[Early East Slavs|East Slavs]], the ethnic group that evolved into the [[Russian]], [[Ukrainian]], and [[Belorussian]] peoples. The first East Slavic state, [[Kievan Rus']] adopted [[Christianity]] from the [[Byzantine Empire]] in the tenth century, beginning the synthesis of Byzantine and [[Slavs|Slavic]] cultures that defined Russian culture for the next thousand years. Kievan Rus' ultimately disintegrated as a state, leaving a number of states competing for claims to be the heirs to its civilization and dominant position. After the thirteenth century, [[Muscovy]] or Moscow gradually came to dominate the former cultural center. By the eighteenth century, the principality of Moscow had become the huge [[Russian Empire]], stretching from [[Poland]] eastward to the [[Pacific Ocean]]. |

|||

{{For timeline|Timeline of Russian history}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2024}} |

|||

{{History of Russia}} |

|||

[[File:Памятник тысячелетию России 2013 06.JPG|thumb|The [[Millennium of Russia]] monument in [[Veliky Novgorod]] (unveiled on 8 September 1862)]] |

|||

[[File:Europe in 1470.PNG|thumb|Medieval [[List of tribes and states in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine|Russian states]] around 1470, including [[Novgorod Republic|Novgorod]], [[Principality of Tver|Tver]], [[Pskov Republic|Pskov]], [[Principality of Ryazan|Ryazan]], [[Rostov, Yaroslavl Oblast|Rostov]] and [[Grand Duchy of Moscow|Moscow]].]] |

|||

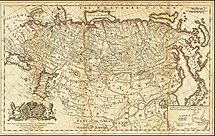

[[File:Territorial Expansion of Russia.svg|thumb|[[Expansion of Russia (1500–1800)|Expansion]] and [[Territorial evolution of Russia|territorial evolution]] of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire between the 14th and 20th centuries]] |

|||

[[File:Soviet Union Administrative Divisions 1989.jpg|thumb|Location of the [[Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic|Russian SFSR]] within the [[Soviet Union]] in 1956–1991]] |

|||

The '''history of Russia''' begins with the histories of the [[East Slavs]].<ref>{{cite web |title=History of Russia – Slavs in Russia: from 1500 BC |url=http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=ac14 |access-date=14 July 2016 |publisher=Historyworld.net |archive-date=9 March 2006 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060309013907/http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=ac14 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Russian Nationalism, Past and Present |publisher=Springer |year=1998 |isbn=9781349265329 |editor-last=Hosking |editor-first=Geoffrey |page=8 |editor-last2=Service |editor-first2=Robert}}</ref> The traditional start date of specifically Russian history is the establishment of the [[Rus' people|Rus']] state in the north in 862, ruled by [[Varangians]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Grey |first1=Ian |title=Russia: A History |date=2015 |isbn=9781612309019 |page=5|publisher=New Word City }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Ketola |first1=Kari |last2=Vihavainen| first2=Timo |title=Changing Russia? : history, culture and business |date=2014 |publisher=Finemor |location=Helsinki |isbn=978-9527124017 |pages=1 |edition=1.}}</ref> In 882, Prince [[Oleg of Novgorod]] seized [[Kiev]], uniting the northern and southern lands of the Eastern Slavs under one authority, moving the governance center to Kiev by the end of the 10th century, and maintaining northern and southern parts with significant autonomy from each other. The state [[Christianization of Kievan Rus'|adopted Christianity from the Byzantine Empire]] in 988, beginning the synthesis of [[Byzantine Empire|Byzantine]] and [[Slavs|Slavic]] cultures that defined [[Russia|Russian culture]] for the next millennium. [[Kievan Rus']] ultimately disintegrated as a state due to the [[Mongol invasion of Rus'|Mongol invasions]] in 1237–1240. After the 13th century, [[Moscow]] emerged as a significant political and cultural force, driving the [[Collector of Russian lands|unification of Russian territories]]. By the end of the 15th century, many of the [[petty kingdom|petty principalities]] around Moscow had been united with the [[Grand Duchy of Moscow]], which took full control of its own sovereignty under [[Ivan III of Russia|Ivan the Great]]. |

|||

Expansion westward sharpened Russia's awareness of its backwardness and shattered the isolation in which the initial stages of expansion had taken. Successive regimes of the nineteenth century responded to such pressures with a combination of halfhearted reform and repression. [[Serfdom]] was abolished in [[1861]], but its abolition was achieved on terms unfavorable to the [[peasant]]s and served to increased revolutionary pressures, at a time when no [[tsar]] was willing to cede autocratic rule or share power. |

|||

[[Ivan the Terrible]] transformed the Grand Duchy into the [[Tsardom of Russia]] in 1547. However, the death of Ivan's son [[Feodor I of Russia|Feodor I]] without [[Issue (genealogy)|issue]] in 1598 created a [[succession crisis]] and led Russia into a period of chaos and civil war known as the [[Time of Troubles]], ending with the coronation of [[Michael of Russia|Michael Romanov]] as the first Tsar of the [[Romanov dynasty]] in 1613. During the rest of the seventeenth century, Russia completed the [[Russian conquest of Siberia|exploration and conquest of Siberia]], claiming lands as far as the Pacific Ocean by the end of the century. Domestically, Russia faced numerous uprisings of the various ethnic groups under their control, as exemplified by the [[Cossack]] leader [[Stenka Razin]], who led a revolt in 1670–1671. In 1721, in the wake of the [[Great Northern War]], Tsar [[Peter the Great]] renamed the state as the [[Russian Empire]]; he is also noted for establishing [[St. Petersburg]] as the new capital of his Empire, and for his introducing Western European culture to Russia. In 1762, Russia came under the control of [[Catherine the Great]], who continued the westernizing policies of Peter the Great, and ushered in the era of the [[Russian Enlightenment]]. Catherine's grandson, [[Alexander I of Russia|Alexander I]], repulsed an [[French invasion of Russia|invasion by the French Emperor Napoleon]], leading Russia into the status of one of the [[great power]]s. |

|||

Military defeat and food shortages triggered the [[Russian Revolution]] in [[1917]], bringing the [[Communist Party of the Soviet Union|Communist]] [[Bolshevik]]s to power. Between [[1922]] and [[1991]], the history of Russia is essentially the [[history of the Soviet Union]], effectively an ideologically based empire was roughly coterminous with the Russian Empire, whose last monarch, Tsar [[Nicholas II of Russia| Nicholas II]], ruled until 1917. From its first years, government in the Soviet Union was based on the one-party rule of the communists, as the Bolsheviks called themselves beginning in March [[1918]]. However, by the late [[1980s]], with the weaknesses of its economic and political structures, significant changes in the economy and the party leaderships spelled the end of the Soviet Union. |

|||

Peasant revolts intensified during the nineteenth century, culminating with [[Alexander II of Russia|Alexander II]] [[Emancipation reform of 1861|abolishing]] [[Serfdom in Russia|Russian serfdom]] in 1861. In the following decades, reform efforts such as the [[Stolypin reform]]s of 1906–1914, the [[Russian Constitution of 1906|constitution of 1906]], and the [[State Duma (Russian Empire)|State Duma]] (1906–1917) attempted to open and liberalize the economy and political system, but the emperors refused to relinquish [[Tsarist autocracy|autocratic rule]] and resisted sharing their power. A combination of economic breakdown, mismanagement over [[Russia in World War I|Russia's involvement in World War I]], and discontent with the autocratic system of government triggered the [[Russian Revolution]] in 1917. The [[February Revolution|end of the monarchy]] initially brought into office a coalition of liberals and moderate socialists, but their failed policies led to the [[October Revolution]]. In 1922, [[Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic|Soviet Russia]], along with the [[Ukrainian SSR]], [[Byelorussian SSR]], and [[Transcaucasian SFSR]] signed the [[Treaty on the Creation of the USSR]], officially merging all four republics to form the Soviet Union as a single state. Between 1922 and 1991 the history of Russia essentially became the [[history of the Soviet Union]].{{Opinion|date=July 2023}} During this period, the [[Soviet Union]] was one of [[Allies of World War II|the victors]] in [[Soviet Union in World War II|World War II]] after recovering from a [[Operation Barbarossa|surprise invasion in 1941]] by [[Nazi Germany]] and its [[Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy|collaborators]], which had previously signed a [[Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact|non-aggression pact]] with the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union's network of [[satellite state]]s in Eastern Europe, which were brought into its [[Soviet Empire|sphere of influence]] in the closing stages of World War II, helped the country become a [[superpower]] competing with fellow superpower the [[United States]] and other Western countries in the [[Cold War]]. |

|||

The [[History of post-Soviet Russia|history of the Russian Federation]] is brief, dating back only to the collapse of the Soviet Union in the end of [[1991]]. But Russia has existed as a state for over a thousand years, and for most of the twentieth century, Russia was the core of the Soviet Union. Since gaining its independence Russia claimed to be the legal successor to Soviet Union on the international stage. However, Russia lost its superpower status as it faced serious challenges in its efforts to forge a new post-Soviet political and economic system. Scrapping the socialist [[planned economy|central planning]] and state ownership of property of the Soviet era, Russia attempted to build an economy with elements of market capitalism, with often painful results. Russia today shares many continuities of political culture and social structure with its tsarist and Soviet past. The question of how well Russia's fragile democratic and federal institutions will fare in the meantime is in doubt, with recent sings of the presidency increasing its already tight control over parliament, regional officeholders, and civil society. |

|||

By the mid-1980s, with the weaknesses of Soviet economic and political structures becoming acute, [[Mikhail Gorbachev]] embarked on major reforms, which eventually led to the weakening of the [[Communist Party of the Soviet Union|communist party]] and [[dissolution of the Soviet Union]], leaving Russia again on its own and marking the start of the [[History of Russia (1991–present)|history of post-Soviet Russia]]. The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic renamed itself as the [[Russian Federation]] and became the primary [[Lisbon Protocol|successor state to the Soviet Union]].<ref>[https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/27389.pdf Article 1 of the Lisbon Protocol] from the U.S. State Department website. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190528160416/https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/27389.pdf|date=28 May 2019}}</ref> Russia retained its [[nuclear arsenal]] but lost its [[superpower]] status. Scrapping the [[planned economy|central planning]] and state-ownership of property of the Soviet era in the 1990s, new leaders, led by President [[Vladimir Putin]], took political and economic power after 2000 and engaged in an assertive [[Foreign policy of Russia|foreign policy]]. Coupled with economic growth, Russia has since regained significant global status as a world power. Russia's 2014 [[Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation|annexation of the Crimean Peninsula]] led to economic sanctions imposed by the United States and the [[European Union]]. Russia's 2022 [[2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine|invasion of Ukraine]] led to significantly expanded [[International sanctions during the Russian invasion of Ukraine|sanctions]]. Under Putin's leadership, [[corruption in Russia]] is rated as the worst in Europe, and Russia's [[Human rights in Russia|human rights situation]] has been increasingly criticized by international observers. |

|||

==Early East Slavs== |

|||

''Main article: [[Early East Slavs]]'' |

|||

==Prehistory== |

|||

The ancestors of the [[Russian]]s were the [[Slavic tribes]], whose original home is thought by some scholars to have been the wooded areas of the [[Pripet Marshes]]. Moving into the lands vacated by the migrating [[Germanic]] tribes, the Eastern Slavs, the ancestors of the Russians who occupied the lands between the [[Carpathians]] and the [[Don River]], were subjected to [[Greek]] [[Christian]] influences. While the fortunes of the [[Byzantine Empire]] had been ebbing, its culture was a continuous influence upon the development of Russia in its formative centuries. |

|||

{{Further|Steppe nomads|Scythians|Scythia|Proto-Uralic|Paleo-Siberian|Pontic–Caspian steppe|Domestication of the horse|Kama culture|Pit–Comb Ware culture}} |

|||

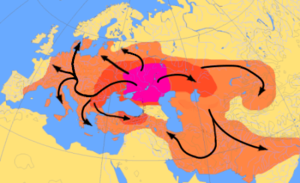

[[File:IE expansion.png|thumb|300px|The [[Kurgan hypothesis]]: South Russia as the [[urheimat]] of [[Proto-Indo-Europeans|Indo-European peoples]]]] |

|||

The first human settlement on the territory of Russia dates back to the [[Oldowan]] period in the early [[Lower Paleolithic]]. About 2 million years ago, representatives of ''[[Homo erectus]]'' migrated from Western Asia to the North Caucasus (archaeological site of {{ill|Kermek|ru|Кермек (стоянка)}} on the [[Taman Peninsula]]<ref>''Щелинский В. Е.'' и др. [http://www.archaeolog.ru/media/ksia/ksia-239.pdf Раннеплейстоценовая стоянка Кермек в Западном Предкавказье (предварительные результаты комплексных исследований)] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210321163415/https://www.archaeolog.ru/media/ksia/ksia-239.pdf |date=21 March 2021 }} // Краткие сообщения ИА РАН. Вып. 239, 2015.</ref>). At {{ill|Bogatyri/Sinyaya balka|ru|Богатыри/Синяя балка}}, in a skull of ''[[Elasmotherium|Elasmotherium caucasicum]]'', which lived 1.5–1.2 million years ago, a stone tool was found.<ref>''Щелинский В. Е.'' {{cite web | url = https://www.archaeolog.ru/media/ksia/ksia-254-redu.pdf#page=34 | title = Об охоте на крупных млекопитающих и использовании водных пищевых ресурсов в раннем палеолите (по материалам раннеашельских стоянок Южного Приазовья) | language = ru | website = www.archaeolog.ru | access-date = 17 December 2019 | archive-date = 7 June 2023 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230607214948/https://www.archaeolog.ru/media/ksia/ksia-254-redu.pdf#page=34 | url-status = live }} // Краткие сообщения Института археологии. Вып. 254. 2019</ref> 1.5-million-year-old [[Oldowan]] flint tools have been discovered in the [[Dagestan]] Akusha region of the north Caucasus, demonstrating the presence of early humans in the territory of present-day Russia.<ref>{{cite web |last1= Chepalyga |first1= A.L. |last2= Amirkhanov |first2= Kh.A. |last3= Trubikhin |first3= V.M. |last4= Sadchikova |first4= T.A. |last5= Pirogov |first5= A.N. |last6= Taimazov |first6= A.I. |year= 2011 |title= Geoarchaeology of the earliest paleolithic sites (Oldowan) in the North Caucasus and the East Europe |url= http://paleogeo.org/article3.html |url-status= dead |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20130520090413/http://paleogeo.org/article3.html |archive-date= 20 May 2013 |access-date= 18 December 2013 |quote= Early Paleolithic cultural layers with tools of oldowan type was discovered in East Caucasus (Dagestan, Russia) by Kh. Amirkhanov (2006) [...]}}</ref> |

|||

Fossils of [[Denisova hominin|Denisovans]] in Russia date to about 110,000 years ago.<ref>[https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.1700186 A fourth Denisovan individual] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220815123645/https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.1700186 |date=15 August 2022 }}, 2017.</ref> DNA from a bone fragment found in [[Denisova Cave]], belonging to a female who died about 90,000 years ago, shows that she was a [[Denny (hybrid hominin)|hybrid of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father]].<ref>Matthew Warren, «Mum's a Neanderthal, Dad's a Denisovan: First discovery of an ancient-human hybrid - Genetic analysis uncovers a direct descendant of two different groups of early humans», ''Nature'', vol. 560, 23 August 2018, pp. 417-418.</ref> Russia was also home to some of the last surviving [[Neanderthal]]s - the partial skeleton of a Neanderthal infant in [[Mezmaiskaya cave]] in [[Adygea]] showed a carbon-dated age of only 45,000 years.<ref>{{cite journal |last1= Igor V. Ovchinnikov |last2= Anders Götherström |last3= Galina P. Romanova |last4= Vitaliy M. Kharitonov |last5= Kerstin Lidén |last6= William Goodwin |date= 30 March 2000 |title= Molecular analysis of Neanderthal DNA from the northern Caucasus |journal= [[Nature (journal)|Nature]] |volume= 404 |issue= 6777 |pages= 490–493 |bibcode= 2000Natur.404..490O |doi= 10.1038/35006625 |pmid= 10761915 |s2cid= 3101375}}</ref> In 2008, Russian [[Archaeology|archaeologists]] from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology of [[Novosibirsk]], working at the site of [[Denisova Cave]] in the [[Altai Mountains]] of [[Siberia]], uncovered a 40,000-year-old small bone fragment from the fifth finger of a juvenile [[hominin]], which DNA analysis revealed to be a previously unknown species of human, which was named the [[Denisova hominin]].<ref>{{Cite news |last= Mitchell |first= Alanna |date= 30 January 2012 |title= Gains in DNA Are Speeding Research into Human Origins |work= The New York Times |url= https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/31/science/gains-in-dna-are-speeding-research-into-human-origins.html?_r=2&nl=todaysheadlines&emc=tha210/& |access-date= 27 February 2017 |archive-date= 12 September 2017 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170912024249/http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/31/science/gains-in-dna-are-speeding-research-into-human-origins.html?_r=2&nl=todaysheadlines&emc=tha210/& |url-status= live }}</ref> |

|||

==Khazaria== |

|||

''Main article: [[Khazaria]]'' |

|||

The first trace of ''Homo sapiens'' on the large expanse of Russian territory dates back to 45,000 years, in central Siberia ([[Ust'-Ishim man]]). The discovery of some of the earliest evidence for the presence of [[anatomically-modern human|anatomically modern human]]s found anywhere in Europe was reported in 2007 from the [[Kostyonki–Borshchyovo archaeological complex|Kostenki archaeological site]] near the [[Don (river)|Don River]] in Russia (dated to at least 40,000 years ago<ref>{{cite web |last= K. Kris Hirst Archaeology Expert |title= Pre-Aurignacian Levels Discovered at the Kostenki Site |url= http://archaeology.about.com/od/earlymansites/a/kostenki.htm |access-date= 18 May 2016 |publisher= Archaeology.about.com |archive-date= 21 March 2021 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20210321163447/https://www.thoughtco.com/kostenki-human-migrations-into-europe-171471 |url-status= dead }}</ref>) and at [[Sungir]] (34,600 years ago). Humans reached Arctic Russia ([[Mamontovaya Kurya]]) by 40,000 years ago. |

|||

The [[Khazar]]s were [[Turkic]] people who inhabited the lower Volga basin [[steppe]]s between the Caspian and Black Seas from the seventh to thirteenth centuries. In the eight century the Khazars embraced [[Judaism]]. [[Itil]], near modern [[Astrakhan]], was their capital. |

|||

During the prehistoric eras the vast [[steppe]]s of Southern Russia were home to [[tribe]]s of [[nomadic pastoralists]]. (In classical antiquity, the [[Pontic Steppe]] was known as "[[Scythia]]".<ref name=Belinskij>{{cite journal |last1= Belinskij |first1= Andrej |last2= H. Härke |date= March–April 1999 |title= The 'Princess' of Ipatovo |url= http://cat.he.net/~archaeol/9903/newsbriefs/ipatovo.html |url-status= dead |journal= Archeology |volume= 52 |issue= 2 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20080610043326/http://cat.he.net/~archaeol/9903/newsbriefs/ipatovo.html |archive-date= 10 June 2008 |access-date= 26 December 2007}}</ref>) Remnants of these long-gone steppe cultures were discovered in the course of the 20th century in such places as [[Ipatovo kurgan|Ipatovo]],<ref name=Belinskij/> [[Sintashta]],<ref>{{cite book |last= Drews |first= Robert |title= Early Riders: The beginnings of mounted warfare in Asia and Europe |publisher= Routledge |year= 2004 |isbn= 0-415-32624-9 |location= New York |page= 50 |author-link= Robert Drews}}</ref> [[Arkaim]],<ref>Dr. Ludmila Koryakova, [http://www.csen.org/koryakova2/Korya.Sin.Ark.html "Sintashta-Arkaim Culture"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190228104055/http://www.csen.org/koryakova2/Korya.Sin.Ark.html |date=28 February 2019 }} - The Center for the Study of the Eurasian Nomads (CSEN). Retrieved 20 July 2007.</ref> and [[Pazyryk burials|Pazyryk]].<ref>[https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/transcripts/2517siberian.html 1998 NOVA documentary: "Ice Mummies: Siberian Ice Maiden"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110513234433/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/transcripts/2517siberian.html |date=13 May 2011 }} Transcript.</ref> |

|||

Noted for their laws, tolerance, and cosmopolitanism, the [[Khazar]]s were the main commercial link between the Baltic and the [[Muslim]] [[Abbasid]] empire centered in [[Baghdad]]. In the eighth and ninth centuries, many East Slavic tribes paid tribute to the Khazars. This ended in the eleventh century, when Slavic and nomadic Turkic invaders brought the downfall of the Khazars. [[Oleg]], a [[Varangian]] warrior, moved south from [[Novgorod]] to expel the Khazars from Kiev and founded Kievan Rus' about [[880]] C.E. |

|||

== |

==Antiquity== |

||

{{Further|Scythia|Bosporan Kingdom|Ancient Greek colonies|Goths|Huns|Turkic migration|Khazaria|History of Siberia}} |

|||

''Main article: [[Kievan Rus']]'' |

|||

[[File:Grave stele 03 pushkin.jpg|thumb|upright|Stele with two [[Hellenistic armies|Hellenistic soldiers]] of the [[Bosporan Kingdom]]; from [[Taman Peninsula]] (Yubileynoe), [[southern Russia]], 3rd quarter of the 4th century BC; marble, [[Pushkin Museum]]]] |

|||

[[Image:sophia_iznutri.jpg|thumb|250px|The Byzantine influence on Russian architecture is evident in [[Saint_Sophia_Cathedral_in_Kiev|Hagia Sophia in Kiev]], originally built in the eleventh century by [[Yaroslav the Wise]].]] |

|||

In the later part of the 8th century BCE, Greek merchants brought [[classical civilization]] to the trade emporiums in [[Tanais]] and [[Phanagoria]].<ref>Esther Jacobson, ''The Art of the Scythians: The Interpenetration of Cultures at the Edge of the Hellenic World'', Brill, 1995, p. 38. {{ISBN|90-04-09856-9}}.</ref> [[Gelonus]] was described by [[Herodotus]] as a huge (Europe's biggest) earth- and wood-fortified [[Grad (Slavic settlement)|grad]] inhabited around 500 BC by Heloni and [[Budini]]. In 513 BC, the king of the [[Achaemenid Empire]], [[Darius the Great|Darius I]], would launch a military campaign around the [[Black Sea]] into Scythia, modern-day Ukraine, eventually reaching the Tanais river (now known as the [[Don (river)|Don]]). |

|||

Greeks, mostly from the city-state of [[Miletus]], would colonize large parts of modern-day Crimea and the [[Sea of Azov]] during the seventh and sixth centuries BC, eventually unifying into the [[Bosporan Kingdom]] by 480 BC, and would be incorporated into the large [[Kingdom of Pontus]] in 107 BC. The Kingdom would eventually be conquered by the [[Roman Republic]], and the Bosporan Kingdom would become a client state of the [[Roman Empire]]. At about the 2nd century AD Goths migrated to the Black Sea, and in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, a semi-legendary Gothic kingdom of [[Oium]] existed in Southern Russia until it was overrun by [[Huns]]. Between the 3rd and 6th centuries AD, the Bosporan Kingdom was also overwhelmed by successive waves of nomadic invasions,<ref>Peter Turchin, ''Historical Dynamics: Why States Rise and Fall'', Princeton University Press, 2003, pp. 185–186. {{ISBN|0-691-11669-5}}.</ref> led by warlike tribes which would often move on to Europe, as was the case with the [[Huns]] and [[Avars (Carpathians)|Turkish Avars]]. |

|||

[[Scandinavia]]n [[Norsemen]] warriors, called Varangians by the [[Byzantine]]s, combined piracy and trade and began to venture along the waterways from the eastern [[Baltic Sea|Baltic]] to the [[Black Sea|Black]] and [[Caspian Sea]]s. The [[Slav]]ic settlers along the rivers often hired the Varangians as protectors. According to the [[Russian Primary Chronicle|earliest chronicle of Kievan Rus']], a Varangian named [[Rurik]] became prince of [[Novgorod]] in about [[860]] C.E. before his successors moved south and extended their authority to [[Kiev]]. By the late ninth century the Varangian ruler of Kiev had established his supremacy over a large area that gradually became to be known as Russia. |

|||

In the second millennium BC, the territories between the Kama and the Irtysh Rivers were the home of a Proto-Uralic-speaking population that had contacts with Proto-Indo-European speakers from the south. The woodland population is the ancestor of the modern Ugrian inhabitants of Trans-Uralia. Other researchers say that the [[Khanty]] people originated in the south Ural steppe and moved northwards into their current location about 500 AD. |

|||

The name "Russia," together with the [[Finnish language|Finnish]] Routsi and [[Estonian language|Estonian]] Rootsi, are found by some scholars to have relationship with [[Roslagen]]. The meaning of ''Rus'' is debated, and other schools of thought connect the name with Slavic or Iranian roots. (See [[Etymology of Rus and derivatives]] for detailed information.) |

|||

A Turkic people, the [[Khazars]], ruled the lower [[Volga River|Volga]] basin [[steppe]]s between the [[Caspian Sea|Caspian]] and [[Black Sea]]s through to the 8th century.<ref name=Christian>David Christian, ''A History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia'', Blackwell Publishing, 1998, pp. 286–288. {{ISBN|0-631-20814-3}}.</ref> Noted for their laws, tolerance, and cosmopolitanism,<ref>Frank Northen Magill, ''Magill's Literary Annual, 1977'' Salem Press, 1977, p. 818. {{ISBN|0-89356-077-4}}.</ref> the Khazars were the main commercial link between the Baltic and the Muslim [[Abbasid]] empire centered in [[Baghdad]].<ref>André Wink, ''Al-Hind, the Making of an Indo-Islamic World'', Brill, 2004, p. 35. {{ISBN|90-04-09249-8}}.</ref> They were important allies of the [[Byzantine Empire|Eastern Roman Empire]],<ref>András Róna-Tas, ''Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian History'', Central European University Press, 1999, p. 257. {{ISBN|963-9116-48-3}}.</ref> and waged a series of successful wars against the [[Arab]] [[Caliphate]]s.<ref name=Christian/><ref name=Frank>Daniel H. Frank and Oliver Leaman, ''History of Jewish Philosophy'', Routledge, 1997, p. 196. {{ISBN|0-415-08064-9}}.</ref> In the 8th century, the Khazars embraced Judaism.<ref name=Frank/> |

|||

Kievan Rus', the first East Slavic state, emerged in the ninth century C.E. along the [[Dnieper River]] valley. A coordinated group of princely states with a common interest in maintaining trade along the river routes, Kievan Rus' controlled the trade route for furs, wax, and slaves between Scandinavia and the [[Byzantine Empire]] along the Dnieper River. By the end of the tenth century the Norse minority had merged with the Slavic population. |

|||

==Early history== |

|||

Among the lasting achievements of Kievan Rus' are the introduction of a Slavic variant of the [[Eastern Orthodox]] religion, dramatically deepening a synthesis of Byzantine and Slavic cultures that defined Russian culture for the next thousand years. The region adopted [[Christianity]] in [[988]] by the official act of public [[baptism]] of Kiev inhabitants by [[Vladimir I of Kiev|Prince Vladimir I]]. Some years later the first code of laws, [[Russkaya Pravda]], was introduced. From the onset the Kievan princes followed the Byzantine example and kept the Church dependent on them, even for its revenues, so that the Russian Church ands state were always closely linked. |

|||

===Early Slavs=== |

|||

By the eleventh century, particularly during the reign of [[Yaroslav the Wise]], Kievan Rus' could boast an economy and achievements in architecture and literature superior to those that then existed in the western party of the continent. Compared with the languages of European Christendom, the Russian language was little influenced by the Greek and [[Latin]] of early Christian writings. This was due to the fact the [[Church Slavonic]] was used directly in [[liturgy]] instead. |

|||

{{Main|East Slavs|Rus' Khaganate}} |

|||

Some of the ancestors of the modern [[Russians]] were the [[Slavic peoples|Slavic tribes]], whose original home is thought by some scholars to have been the [[Pripet Marshes]].<ref>For a discussion of Slavic origins, see Paul M. Barford, ''The Early Slavs'', Cornell University Press, 2001, pp. 15–16. {{ISBN|0-8014-3977-9}}.</ref> The [[Early East Slavs]] gradually settled [[Western Russia]] in two waves: one moving from [[Kiev]] (present-day [[Ukraine]]) towards present-day [[Suzdal]] and [[Murom]] and another from [[Polotsk]] (present-day [[Belarus]]) towards [[Novgorod]] and [[Rostov, Yaroslavl Oblast|Rostov]].<ref name=Christian2>David Christian, op cit., pp. 6–7.</ref> |

|||

From the 7th century onwards, East Slavs constituted the bulk of the population in Western Russia<ref name=Christian2/> and slowly conquered and assimilated the native [[Finnic peoples|Finnic]] and [[Baltic peoples|Baltic tribes]], such as the [[Merya people|Merya]],<ref>Henry K Paszkiewicz, ''The Making of the Russian Nation'', Darton, Longman & Todd, 1963, p. 262.</ref> the [[Muromians]],<ref>Ed. [[Timothy Reuter]], ''The New Cambridge Medieval History'', Volume 3, Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 494-497. {{ISBN|0-521-36447-7}}.</ref> and the [[Meshchera]].<ref name="Mongait">[[Aleksandr Lʹvovich Mongaĭt]], ''Archeology in the U.S.S.R.'', Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1959, p. 335.</ref> |

|||

Kievan Rus' ultimately disintegrated as a state because of the armed struggles among members of the princely family that collectively possessed it. Conquest by the [[Mongol]]s in the thirteenth century was the final blow. In later centuries, a number of states claimed to be the heirs to the civilization and dominant position of Kievan Rus'. [[Muscovy]], the eventual heir, was located at the far northern edge of the former cultural center. |

|||

===Kievan Rus' (862–1240)=== |

|||

==Volga Bulgaria== |

|||

{{Main|Kievan Rus'}} |

|||

''Main article: [[Volga Bulgaria]]'' |

|||

[[File:Варяги.jpg|thumb|left|''[[Calling of the Varangians]]'' by [[Viktor Vasnetsov]]]] |

|||

[[Scandinavia]]n Norsemen, known as [[Vikings]] in Western Europe and [[Varangian]]s{{sfn|Magocsi|2010|p=55, 59–60}} in the East, combined [[piracy]] and trade throughout Northern Europe. In the mid-9th century, they began to venture along the waterways from the eastern [[Baltic Sea|Baltic]] to the [[Black Sea|Black]] and [[Caspian Sea]]s.<ref>Dimitri Obolensky, ''Byzantium and the Slavs'', St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1994, p. 42. {{ISBN|0-88141-008-X}}.</ref> According to the legendary [[Calling of the Varangians]], recorded in several [[Rus' chronicle]]s such as the ''[[Novgorod First Chronicle]]'' and ''[[Primary Chronicle]]'', the Varangians [[Rurik]], [[Sineus and Truvor]] were invited in the 860s to restore order in three towns – either [[Novgorod]] (most texts) or [[Staraya Ladoga]] (''[[Hypatian Codex]]''); [[Beloozero]]; and [[Izborsk]] (most texts) or "Slovensk" (''Pskov Third Chronicle''), respectively.{{sfn|Martin|2009b|p=3}}{{sfn|Magocsi|2010|p=55, 59–60}}{{sfn|Cross|Sherbowitz-Wetzor|1953|p=38–39}}<ref name=Curtis>[http://www.shsu.edu/~his_ncp/Kievan.html Kievan Rus' and Mongol Periods] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927230631/http://www.shsu.edu/~his_ncp/Kievan.html |date=27 September 2007 }}, excerpted from Glenn E. Curtis (ed.), ''Russia: A Country Study'', Department of the Army, 1998. {{ISBN|0-16-061212-8}}.</ref> Their successors allegedly moved south and extended their authority to [[Kiev]],<ref>James Westfall Thompson, and Edgar Nathaniel Johnson, ''An Introduction to Medieval Europe, 300–1500'', W. W. Norton & Co., 1937, p. 268.</ref> which had been previously dominated by the Khazars.<ref>David Christian, Op cit. p. 343.</ref> |

|||

Thus, the first East Slavic state, [[Kievan Rus|Rus']], emerged in the 9th century along the [[Dnieper River]] valley.<ref name=Curtis/> A coordinated group of princely states with a common interest in maintaining trade along the river routes, Kievan Rus' controlled [[Trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks|the trade route for furs, wax, and slaves]] between Scandinavia and the [[Byzantine Empire]] along the [[Volkhov River|Volkhov]] and Dnieper Rivers.<ref name=Curtis/> |

|||

Volga Bulgaria was a non-Slavic state on the middle Volga. After the Mongol Invasion it became a part of [[Golden Horde]]. The [[Chuvash]]es and [[Tatar|Kazan Tatar]]s are descendants of the Volga [[Bulgars]]. By tenth century C.E. Volga Bulgaria was converted to [[Islam]]. Converting to Islam made Volga Bulgaria independent of [[Khazaria]]. In the sixteenth century, Russia conquered the Bulgar lands under [[Tsar]] [[Ivan IV of Russia|Ivan IV]] ('The Terrible'). |

|||

By the end of the 10th century, the minority [[Old Norse language|Norse]] military aristocracy had merged with the native Slavic population,<ref>Particularly among the aristocracy. See {{usurped|1=[https://web.archive.org/web/20070718120101/http://history-world.org/BYZ4.htm World History]}}. Retrieved 22 July 2007.</ref> which also absorbed [[Byzantine Greece|Greek]] Christian influences in the course of the multiple [[Rus'–Byzantine War (disambiguation)|campaigns]] to loot [[Tsargrad]], or [[Constantinople]].<ref>See Dimitri Obolensky, "Russia's Byzantine Heritage," in ''Byzantium & the Slavs'', St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1994, pp. 75–108. {{ISBN|0-88141-008-X}}.</ref> One such campaign claimed the life of the foremost Slavic [[druzhina]] leader, [[Svyatoslav I]], who was renowned for having crushed the power of the [[Khazars]] on the Volga.<ref>Serhii Plokhy, ''The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus'', Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 13. {{ISBN|0-521-86403-8}}.</ref> |

|||

==Mongol Invasion== |

|||

''Main article [[Mongol invasion of Russia]]'' |

|||

[[File:Kievan-rus-1015-1113-(en).png|thumb|right|Kievan Rus' after the [[Council of Liubech]] in 1097]] |

|||

The invading Mongols accelerated the fragmentation of the Kievan Rus'. In [[1223]], the Kievan Rus' faced a Mongol raiding party at the [[Battle of the Kalka River|Kalka River]] and was soundly defeated. In [[1240]] the Mongols sacked the city of Kiev and then moved west into [[Poland]] and [[Hungary]]. By then had conquered most of the Russian principalities. Of the principalities of Kievan Rus', only the Novgorod escaped occupation. |

|||

Kievan Rus' is important for its introduction of a [[Russian Orthodox Church|Slavic variant]] of the [[Eastern Orthodoxy|Eastern Orthodox]] religion,<ref name=Curtis/> dramatically deepening a synthesis of Byzantine and Slavic cultures that defined Russian culture for the next thousand years. The region [[Christianization of Kievan Rus'|adopted Christianity in 988]] by the official act of public [[baptism]] of Kiev inhabitants by [[Vladimir I of Kiev|Prince Vladimir I]].<ref>See [http://www.dur.ac.uk/a.k.harrington/christin.html The Christianisation of Russia] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070727221316/http://www.dur.ac.uk/a.k.harrington/christin.html |date=27 July 2007 }}, an account of Vladimir's baptism, followed by the baptism of the entire population of Kiev, as described in ''The Russian Primary Chronicle''.</ref> Some years later the first code of laws, [[Russkaya Pravda]], was introduced by [[Yaroslav the Wise]].<ref name="Smith">Gordon Bob Smith, ''Reforming the Russian Legal System'', Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp. 2–3. {{ISBN|0-521-45669-X}}.</ref> From the onset, the Kievan princes followed the Byzantine example and kept the Church dependent on them.<ref>P. N. Fedosejev, ''The Comparative Historical Method in Soviet Mediaeval Studies'', USSR Academy of Sciences, 1979. p. 90.</ref> |

|||

By the 11th century, particularly during the reign of [[Yaroslav the Wise]], Kievan Rus' displayed an economy and achievements in architecture and literature superior to those that then existed in the western part of the continent.<ref>Russell Bova, ''Russia and Western Civilization: Cultural and Historical Encounters'', M.E. Sharpe, 2003, p. 13. {{ISBN|0-7656-0976-2}}.</ref> Compared with the languages of European Christendom, the [[Russian language]] was little influenced by the [[Greek language|Greek]] and [[Latin]] of early Christian writings.<ref name=Curtis/> This was because [[Church Slavonic]] was used directly in [[liturgy]] instead.<ref>Timothy Ware: ''The Orthodox Church'' (Penguin, 1963; 1997 revision) p. 74</ref> |

|||

The impact of the Mongol invasion on the territories of Kievan Rus' was uneven. Centers such as Kiev never recovered from the devastation of the initial attack. Immigrants who left southern Russia to escape the Mongols gravitated mostly to the northeast, where the soil was better and the rivers more conducive to commercial development. It was this region that provided the nucleus of the modern Russian state in the late medieval period. However, Novgorod continued to prosper; and a new entity, Muscovy, began to flourish under the Mongols. |

|||

A nomadic Turkic people, the [[Kipchaks]] (also known as the Cumans), replaced the earlier [[Pechenegs]] as the dominant force in the south steppe regions neighbouring to Rus' at the end of the 11th century and founded a nomadic state in the steppes along the Black Sea (Desht-e-Kipchak). Repelling their regular attacks, especially in Kiev, was a heavy burden for the southern areas of Rus'. The nomadic incursions caused a massive influx of Slavs to the safer, heavily forested regions of the north, particularly to the area known as [[Zalesye]].{{citation needed|date=May 2023}} |

|||

Kievan Rus' ultimately disintegrated as a state because of in-fighting between members of the princely family that ruled it collectively. Kiev's dominance waned, to the benefit of [[Vladimir-Suzdal]] in the north-east, [[Novgorod Republic|Novgorod]] in the north, and [[Halych-Volhynia]] in the south-west. Conquest by the [[Mongol]] [[Golden Horde]] in the 13th century was the final blow. Kiev was destroyed.<ref name="Hamm">In 1240. See Michael Franklin Hamm, ''Kiev: A Portrait, 1800–1917'', Princeton University Press, 1993. {{ISBN|0-691-02585-1}}</ref> Halych-Volhynia would eventually be absorbed into the [[Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth]],<ref name=Curtis/> while the Mongol-dominated Vladimir-Suzdal and independent [[Novgorod Republic]], two regions on the periphery of Kiev, would establish the basis for the modern Russian nation.<ref name=Curtis/> |

|||

==Golden Horde== |

|||

''Main article: [[Golden Horde]]'' |

|||

[[Image:Alexnev.jpg|thumbnail|200px|left|Alexander Nevski]] |

|||

===Mongol invasion and vassalage (1223–1480)=== |

|||

The Mongols dominated Russia from their western capital at [[Sarai]] on the [[Volga River]], near the modern city of [[Volgograd]]. The princes of southern and eastern Russia had to pay tribute to to the Mongols, commonly called [[Tartar]]s, or the Golden Horde; but in return they received charters authorizing them to act as deputies to the khans. In general, the princes were allowed considerable freedom to rule as they wished. One of them, [[Alexander Nevsky]], prince of Vladimir, acquired heroic status in the mid-thirteenth century as the result of major victories over the [[Teutonic Knights]], and the [[Lithuanian]]s. To the Orthodox Church and most princes, the westerners seemed a greater threat to the Russian way of life than the Mongols. Nevsky obtained Mongol protection and assistance in fighting invaders from the west, who, hoping to profit from the Russian collapse since the Mongol invasions, tried to grab territory. Even so, Nevsky's successors would later come to challenge Tartar rule. |

|||

{{Main|Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus'|Great Troubles}} |

|||

[[File:Mongols vladimir.jpg|thumb|left|The sacking of [[Vladimir, Russia|Vladimir]] by [[Batu Khan]] in February 1238]] |

|||

The invading [[Mongols]] accelerated the fragmentation of the [[Kievan Rus'|Rus]]'. In 1223, the disunited southern princes faced a Mongol raiding party at the [[Battle of the Kalka River|Kalka River]] and were soundly defeated.<ref>See [[David Nicolle]], ''Kalka River 1223: Genghis Khan's Mongols Invade Russia'', Osprey Publishing, 2001. {{ISBN|1-84176-233-4}}.</ref> In 1237–1238 the Mongols burnt down the city of [[Vladimir, Russia|Vladimir]] (4 February 1238)<ref>Tatyana Shvetsova, [http://www.vor.ru/English/homeland/home_004.html The Vladimir Suzdal Principality] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080320070136/http://www.vor.ru/English/homeland/home_004.html |date=20 March 2008 }}. Retrieved 21 July 2007.</ref> and other major cities of northeast Russia, routed the Russians [[Battle of the Sit River|at the Sit' River]],{{sfn|Martin|2004|p=139}} and then moved west into [[Poland]] and [[Hungary]]. By then they had conquered most of the Russian principalities.<ref>{{cite web |url = https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/citd/RussianHeritage/4.PEAS/4.L/12.III.5.html |title = The Destruction of Kiev |archive-url=https://archive.today/20110427075859/https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/citd/RussianHeritage/4.PEAS/4.L/12.III.5.html |archive-date=27 April 2011 |url-status=dead}}</ref> Only the [[Novgorod Republic]] escaped occupation and continued to flourish in the orbit of the [[Hanseatic League]].<ref>Jennifer Mills, [http://depts.washington.edu/baltic/papers/hansa.html The Hanseatic League in the Eastern Baltic] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629134048/http://depts.washington.edu/baltic/papers/hansa.html |date=29 June 2011 }}, SCAND 344, May 1998. Retrieved 21 July 2007.</ref> |

|||

The Mongols left their impact on the Russians in such areas as military tactics and the development of trade routes. Under Mongol occupation, Muscovy also developed its postal road network, census, fiscal system, and military organization. Eastern influence remained strong well until the eighteenth century, when Russian rulers made a conscious effort to Westernize their country. |

|||

The impact of the Mongol invasion on the territories of Kievan Rus' was uneven. The advanced city culture was almost completely destroyed. As older centers such as Kiev and Vladimir never recovered from the devastation of the initial attack,<ref name="Hamm"/> the new cities of Moscow,<ref name=Curtis2>[http://countrystudies.us/russia/3.htm Muscovy] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110920102514/http://countrystudies.us/russia/3.htm |date=20 September 2011 }}, excerpted from Glenn E. Curtis (ed.), ''Russia: A Country Study'', Department of the Army, 1998. {{ISBN|0-16-061212-8}}.</ref> [[Tver]]<ref name=Curtis2/> and [[Nizhny Novgorod]]<ref>Sigfried J. De Laet, ''History of Humanity: Scientific and Cultural Development'', Taylor & Francis, 2005, p. 196. {{ISBN|92-3-102814-6}}.</ref> began to compete for hegemony in the Mongol-dominated [[Rus' principalities]] under the suzerainty of the [[Golden Horde]]. Although a coalition of Rus' princes led by [[Dmitry Donskoy]] defeated Mongol warlord [[Mamai]] at [[Battle of Kulikovo|Kulikovo]] in 1380,<ref name=Kulikovo>[http://www.fanaticus.org/DBA/battles/Kulikovo/index.html The Battle of Kulikovo (8 September 1380)] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070607151328/http://www.fanaticus.org/DBA/battles/Kulikovo/index.html |date=7 June 2007 }}. Retrieved 22 July 2007.</ref> forces of the new khan [[Tokhtamysh]] and his Rus' allies immediately [[Siege of Moscow (1382)|sacked Moscow in 1382]] as punishment for resisting Mongol authority.{{sfn|Halperin|1987|p=73–75}} Mongol domination of the Rus' principalities, along with tax collection by various overlords such as the [[Crimean Khanate|Crimean Khans]], continued into the early 16th century, despite later claims of Muscovite bookmen that the [[Great Stand on the Ugra River|indecisive standoff at the Ugra in 1480]] had signified "the end of the Tatar yoke" and the "liberation of Russia".{{sfn|Halperin|1987|p=77–78}} |

|||

==Muscovy== |

|||

''Main article: [[Muscovy]]'' |

|||

The Mongols dominated the lower reaches of the Volga and held Russia in sway from their western capital at [[Sarai (city)|Sarai]],<ref name="history world">{{cite web|url=http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=aa76|title=History of the Mongols|publisher=History World|access-date=26 July 2007|archive-date=28 October 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181028151842/http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=aa76|url-status=live}}</ref> one of the largest cities of the medieval world. The princes had to pay tribute to the Mongols of the Golden Horde, commonly called [[Tatars]];<ref name="history world" /> but in return they received charters authorizing them to act as deputies to the khans. In general, the princes were allowed considerable freedom to rule as they wished,<ref name="history world" /> while the [[Russian Orthodox Church]] even experienced a spiritual revival. |

|||

===The rise of Moscow=== |

|||

The Mongols left their impact on the Russians in such areas as military tactics and transportation. Under Mongol occupation, Muscovy also developed its postal road network, census, fiscal system, and military organization.<ref name=Curtis/> |

|||

[[Daniil Aleksandrovich]], the youngest son of Nevski, founded the principality of Muscovy or Moscow, which eventually expelled the Tartars from Russia. Well-situated in the central river system of Russia and surrounded by protective forests and marshes, Moscow was at first only a vassal of Vladimir, but soon it absorbed its parent state. A major factor in the ascendancy of Moscow was the cooperation of its rulers with the Mongol overlords, who granted them the title of Grand Prince of Russia and made them agents for collecting the Tartar tribute from the Russian principalities. Moscow's prestige was further enhanced when it became the center of the [[Russian Orthodox Church]]. Its head, the metropolitan, fled from Kiev to Vladimir in [[1299]] and a few years later established the permanent headquarters of the Church in Moscow. |

|||

At the same time, Prince of Novgorod, [[Alexander Nevsky]], managed to [[Battle on the Ice|repel the offensive]] of the [[Northern Crusades]] against [[Novgorod Republic|Novgorod]] from the West. Despite this, becoming the Grand Prince, Alexander declared himself a vassal to the Golden Horde, not having the strength to resist its power.{{POV statement|date=November 2020}} |

|||

By the middle of the fourteenth century, the power of the Mongols was declining, and the Grand Princes felt capable of openly opposing the Mongol yoke. In [[1380]], at [[Kulikovo]] on the [[Don River]], the khan was defeated, and although this hard-fought victory did not end Tartar rule of Russia. It did bring great fame to the Grand Prince. Moscow's leadership in Russia was now firmly based, and by the middle of the fourteenth century its territory had greatly expanded through purchase, war, and marriage. |

|||

==Grand Duchy of Moscow (1283–1547)== |

|||

{{Main|Grand Duchy of Moscow}} |

|||

===Rise of Moscow=== |

|||

[[File:Dmitry Donskoy in the Battle of Kulikovo.jpg|thumb|left|[[Dmitry Donskoy]] in the [[Battle of Kulikovo]]]] [[Daniil Aleksandrovich]], the youngest son of Alexander Nevsky, founded the [[Grand Duchy of Moscow|principality of Moscow]] (known as Muscovy in English),<ref name=Curtis2/> which first cooperated with and ultimately expelled the Tatars from Russia. Well-situated in the central river system of Russia and surrounded by protective forests and marshes, Moscow was at first only a [[vassal]] of Vladimir, but soon it absorbed its parent state. |

|||

A major factor in the ascendancy of Moscow was the cooperation of its rulers with the Mongol overlords, who granted them the title of Grand Prince of Moscow and made them agents for collecting the Tatar tribute from the Russian principalities. The principality's prestige was further enhanced when it became the center of the [[Russian Orthodox Church]]. Its head, the [[Metropolitan bishop|Metropolitan]], fled from Kiev to [[Vladimir-Suzdal|Vladimir]] in 1299 and a few years later established the permanent headquarters of the Church in Moscow under the original title of Kiev Metropolitan. |

|||

By the middle of the 14th century, the power of the Mongols was declining, and the Grand Princes felt able to openly oppose the [[Mongol yoke]]. In 1380, at [[Battle of Kulikovo]] on the [[Don River, Russia|Don River]], the Mongols were defeated,<ref name=Kulikovo/> and although this hard-fought victory did not end Tatar rule of Russia, it did bring great fame to the Grand Prince [[Dmitry Donskoy]]. Moscow's leadership in Russia was now firmly based and by the middle of the 14th century its territory had greatly expanded through purchase, war, and marriage. |

|||

===Ivan III, the Great=== |

===Ivan III, the Great=== |

||

{{Main|Ivan III of Russia}} |

|||

[[File:Иван III Великий.JPG|thumb|right|[[Ivan III of Russia]] at the [[Millennium of Russia]]. At his feet, defeated: Tatar, Lithuanian and Baltic German.]] |

|||

In the 15th century, the grand princes of Moscow continued to consolidate Russian land to increase their population and wealth. The most successful practitioner of this process was [[Ivan III of Russia|Ivan III]],<ref name=Curtis2/> who laid the foundations for a Russian national state. Ivan competed with his powerful northwestern rival, the [[Grand Duchy of Lithuania]], for control over some of the semi-independent [[Upper Principalities]] in the upper [[Dnieper River|Dnieper]] and [[Oka River]] basins.<ref>[http://www.bartleby.com/65/iv/Ivan3.html Ivan III] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070806175518/http://bartleby.com/65/iv/Ivan3.html |date=6 August 2007 }}, [[The Columbia Encyclopedia]], Sixth Edition. 2001–05.</ref><ref name="EB_IvanIII">[https://www.britannica.com/eb/article-3598 Ivan III] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071215072314/http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-3598 |date=15 December 2007 }}, ''[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]''. 2007</ref> |

|||

Through the defections of some princes, border skirmishes, and a long war with the Novgorod Republic, Ivan III was able to annex Novgorod and Tver.<ref>Donald Ostrowski in ''The Cambridge History of Russia'', Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 234. {{ISBN|0-521-81227-5}}.</ref> As a result, the [[Grand Duchy of Moscow]] tripled in size under his rule.<ref name=Curtis2/> During his conflict with Pskov, a monk named [[Filofei]] (Philotheus of Pskov) composed a letter to Ivan III, with the prophecy that the latter's kingdom would be the [[Third Rome]].<ref name=EB3R>See e.g. [https://www.britannica.com/ebc/article-60463 Eastern Orthodoxy] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071018051458/http://www.britannica.com/ebc/article-60463 |date=18 October 2007 }}, ''[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]''. 2007. ''Encyclopædia Britannica''.</ref> The [[Fall of Constantinople]] and the death of the last Greek Orthodox Christian emperor contributed to this new idea of [[Moscow, third Rome|Moscow as ''New Rome'']] and the seat of Orthodox Christianity, as did Ivan's 1472 marriage to Byzantine Princess [[Sophia Palaiologina]].<ref name=Curtis2/> |

|||

In the fourteenth century, the grand princes of Moscow began gathering Russian lands to increase the population and wealth under their rule. The most successful practitioner of this process was [[Ivan III of Russia|Ivan III]], the Great ([[1462]]-[[1505]]), who laid the foundations for a Russian national state. A contemporary of the [[Tudor]]s and other "new monarchs" in Western Europe, Ivan more than double his territories by placing most of north Russia under the rule of Moscow, and he proclaimed his absolute sovereignty over all Russian princes and nobles. Refusing further tribute to the Tartars, Ivan initiated a series of attacks that opened the way for the complete defeat of the declining Golden Horde, now divided into several khanates. |

|||

Under Ivan III, the first central government bodies were created in Russia: [[Prikaz]]. The [[Sudebnik of 1497|Sudebnik]] was adopted, the first set of laws since the 11th century. The double-headed eagle was adopted as the [[coat of arms of Russia]]. |

|||

Ivan III was the first Muscovite ruler to use the titles of ''tsar'', derived from "Caesar," and he viewed Moscow as the [[Third Rome]], the successor of New Rome ([[Constantinople]]). Ivan competed with his powerful northwestern rival Lithuania for control over some of the semi-independent former principalities of Kievan Rus' in the upper Dnieper and [[Donets River]] basins. Through the defections of some princes, border skirmishes, and a long, inconclusive war with Lithuania that ended only in [[1503]], Ivan III was able to push westward, and Moscow tripled in size under his rule. |

|||

[[File:Muscovy 1390 1525.png|thumb|left|Grand Duchy of Moscow (Territorial expansion between 1300 and 1547)]] |

|||

Ivan proclaimed his absolute sovereignty over all Russian princes and nobles. Refusing further tribute to the Tatars, Ivan initiated a series of attacks that opened the way for the complete defeat of the declining [[Golden Horde]], now divided into several [[Khanate]]s and hordes. Ivan and his successors sought to protect the southern boundaries of their domain against attacks of the [[Khanate of Crimea|Crimean Tatars]] and other hordes.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.allempires.info/article/index.php?q=The_Crimean_Khanate |title=The Tatar Khanate of Crimea |access-date=12 July 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171108032646/http://www.allempires.info/article/index.php?q=The_Crimean_Khanate |archive-date=8 November 2017 |url-status=dead }}</ref> To achieve this aim, they sponsored the construction of the [[Great Abatis Belt]] and granted manors to nobles, who were obliged to serve in the military. The manor system provided a basis for an emerging cavalry-based army. |

|||

In this way, internal consolidation accompanied outward expansion of the state. By the 16th century, the rulers of Moscow considered the entire Russian territory their collective property. Various semi-independent princes still claimed specific territories,<ref name="EB_IvanIII"/> but Ivan III forced the lesser princes to acknowledge the grand prince of Moscow and his descendants as unquestioned rulers with control over military, judicial, and foreign affairs. Gradually, the Russian ruler emerged as a powerful, autocratic ruler, a tsar. The first Russian ruler to officially crown himself "[[Tsar]]" was [[Ivan IV]].<ref name=Curtis2/> |

|||

Ivan III tripled the territory of his state, ended the dominance of the [[Golden Horde]] over the Rus', renovated the [[Moscow Kremlin]], and laid the foundations of the Russian state. Biographer Fennell concludes that his reign was "militarily glorious and economically sound," and especially points to his territorial annexations and his centralized control over local rulers. However, Fennell argues that his reign was also "a period of cultural depression and spiritual barrenness. Freedom was stamped out within the Russian lands. By his bigoted anti-Catholicism Ivan brought down the curtain between Russia and the west. For the sake of territorial aggrandizement he deprived his country of the fruits of Western learning and civilization."<ref>J. L. I. Fennell, ''Ivan the Great of Moscow'' (1961) p. 354</ref> |

|||

==Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721)== |

|||

{{Main|Tsardom of Russia}} |

|||

===Ivan IV, the Terrible=== |

===Ivan IV, the Terrible=== |

||

[[File:Ivan IV the Terrible portrait by Weigel 1882.jpg|thumb|[[Ivan IV]] was the [[Grand Prince of Moscow]] from 1533 to 1547, then "Tsar of All the Russias" until his death in 1584.]] |

|||

[[Image:Kremlinpic4.jpg|thumbnail|200px|right|Portrait of Ivan the Terrible]] |

|||

The development of the Tsar's autocratic powers reached a peak during the reign of [[Ivan IV of Russia|Ivan IV]] (1547–1584), known as "Ivan the Terrible".<ref>{{cite book | first=Tim | last=McDaniel | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0yIABAAAQBAJ&pg=PA46 | title=Autocracy, Modernization, and Revolution in Russia and Iran | publisher=Princeton University Press | date=1991 | isbn=0-691-03147-9 | page=46}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | first=Kevin | last=O'Connor | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=b3b5nU4bnw4C&pg=PA23 | title=The History of the Baltic States | url-status=live | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221030013948/https://books.google.com/books?id=b3b5nU4bnw4C&pg=PA23& | archive-date=30 October 2022 | publisher=Greenwood Press | date=2003 | isbn=0-313-32355-0 | page=23}}</ref> He strengthened the position of the monarch to an unprecedented degree, as he ruthlessly subordinated the nobles to his will, exiling or executing many on the slightest provocation.<ref name=Curtis2/> Nevertheless, Ivan is often seen as a farsighted statesman who reformed Russia as he promulgated a new code of laws ([[Sudebnik of 1550]]),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/history/russia/ivantheterrible.html|title=Ivan the Terrible|access-date=23 July 2007|work=Minnesota State University Mankato|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070718145812/http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/history/russia/ivantheterrible.html|archive-date=18 July 2007}}</ref> established the first Russian feudal representative body ([[Zemsky Sobor]]), curbed the influence of the clergy,<ref>{{cite journal |last=Zenkovsky |first=Serge A. |author-link=Serge Aleksandr Zenkovsky |date=October 1957 |title=The Russian Church Schism: Its Background and Repercussions|journal=Russian Review |volume=16 |issue=4 |pages=37–58 |doi=10.2307/125748 |jstor=125748 |publisher=Blackwell Publishing}}</ref> and introduced local self-management in rural regions.<ref>Skrynnikov R., "Ivan Grosny", p. 58, M., AST, 2001</ref> Tsar also created the first regular army in Russia: [[Streltsy]]. |

|||

His long [[Livonian War]] (1558–1583) for control of the Baltic coast and access to the sea trade ultimately proved a costly failure.<ref>{{cite web | work=Lithuanian Quarterly Journal of Arts and Sciences | title=The Origin of the Livonian War, 1558 | access-date=16 July 2023 | first=William | last=Urban | date=Fall 1983 | url=http://www.lituanus.org/1983_3/83_3_02.htm | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20020530071736/http://www.lituanus.org/1983_3/83_3_02.htm | archive-date=30 May 2002}}</ref> Ivan managed to annex the [[Khanate of Kazan|Khanates of Kazan]], [[Khanate of Astrakhan|Astrakhan]], and [[Siberia Khanate|Siberia]].{{sfn|Martin|2004|p=395}} These conquests complicated the migration of aggressive nomadic hordes from Asia to Europe via the Volga and [[Urals]]. Through these conquests, Russia acquired a significant Muslim Tatar population and emerged as a [[multiethnic]] and [[wikt:multiconfessional|multiconfessional]] state. Also around this period, the mercantile [[Stroganov]] family established a firm foothold in the Urals and recruited Russian [[Cossacks]] to colonise Siberia.<ref>[[Siberian Chronicles]], Строгановская Сибирская Летопись. изд. Спаским, СПб, 1821</ref> |

|||

In the later part of his reign, Ivan divided his realm in two. In the zone known as the ''[[oprichnina]]'', Ivan's followers carried out a series of bloody purges of the feudal aristocracy (whom he suspected of treachery after prince [[Andrey Kurbsky]]'s betrayal), culminating in the [[Massacre of Novgorod]] in 1570. This combined with the military losses, epidemics, and poor harvests so weakened Russia that the [[Crimean Tatars]] were able to sack central Russian regions and [[Russo–Crimean War (1571)|burn down Moscow in 1571]].<ref>Skrynnikov R. "Ivan Grozny", M, 2001, pp. 142–173</ref> However, in 1572 the Russians defeated the Crimean Tatar army at the [[Battle of Molodi]] and Ivan abandoned the ''oprichnina''.<ref>[[Robert I. Frost]] ''The Northern Wars: 1558–1721'' (Longman, 2000) pp. 26–27</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.economist.com/cities/printStory.cfm?obj_id=9141603&city_id=MCW | title=Moscow – Historical background | work=The Economist: City Guide | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071011214606/http://www.economist.com/cities/printStory.cfm?obj_id=9141603&city_id=MCW | archive-date=11 October 2007}}</ref> |

|||

At the end of Ivan IV's reign the Polish–Lithuanian and Swedish armies carried out a powerful intervention in Russia, devastating its northern and northwest regions.<ref>Skrynnikov. "Ivan Grozny", M, 2001, pp. 222–223</ref> |

|||

The development of the tsar's autocratic powers reached a peak during the reign of [[Ivan IV]], and he became known as the Terrible. Ivan strengthened the position of the tsar to an unprecedented degree, as Ivan ruthlessly subordinated the nobles to his will, exiling or executing many on the slightest pretext. Nevertheless, Ivan was a farsighted statesman who promulgated a new code of laws, reformed the morals of the clergy, and built the great [[St. Basil's Cathedral]] that still stands in Moscow's [[Red Square]]. |

|||

===Time of Troubles=== |

===Time of Troubles=== |

||

{{Main|Time of Troubles}} |

|||

[[File:Lissner.jpg|thumb|The Poles surrender the [[Moscow Kremlin]] to [[Prince Pozharsky]] in 1612]] |

|||

The death of Ivan's childless son [[Feodor I of Russia|Feodor]] was followed by a period of civil wars and foreign intervention known as the [[Time of Troubles]] (1606–13).<ref name=Curtis2/> Extremely cold summers (1601–1603) wrecked crops,<ref>Borisenkov E, Pasetski V. "The thousand-year annals of the extreme meteorological phenomena", {{ISBN|5-244-00212-0}}, p. 190</ref> which led to the [[Russian famine of 1601–1603]] and increased the social disorganization. [[Boris Godunov]]'s reign ended in chaos, civil war combined with foreign intrusion, devastation of many cities and depopulation of the rural regions. The country rocked by internal chaos also attracted several waves of interventions by the [[Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth]].<ref>Solovyov. "History of Russia...", v.7, pp. 533–535, 543–568</ref> |

|||

During the [[Polish–Muscovite War (1605–1618)]], Polish–Lithuanian forces reached Moscow and installed the impostor [[False Dmitriy I]] in 1605, then supported [[False Dmitry II]] in 1607. The decisive moment came when a combined Russian-Swedish army was routed by the Polish forces under [[hetman]] [[Stanisław Żółkiewski]] at the [[Battle of Klushino]] on {{OldStyleDate|4 July|1610|24 June}}. As the result of the battle, the [[Seven Boyars]], a group of Russian nobles, deposed the tsar [[Vasily Shuysky]] on {{OldStyleDate|27 July|1610|17 July}}, and recognized the Polish prince [[Władysław IV Vasa]] as the Tsar of Russia on {{OldStyleDate|6 September|1610|27 August}}.<ref>[[Lev Gumilev]] (1992), ''Ot Rusi k Rossii. Ocherki e'tnicheskoj istorii'' [From Rus' to Russia], Moscow: Ekopros.</ref><ref>Michel Heller (1997), ''Histoire de la Russie et de son empire'' [A history of Russia and its empire], Paris: Plon.</ref> The [[Polish–Lithuanian occupation of Moscow|Poles occupied Moscow]] on {{OldStyleDate|21 September|1610|11 September}}. Moscow revolted but riots there were brutally suppressed and the city was set on fire.<ref name=Vern>[[George Vernadsky]], "A History of Russia", Volume 5, Yale University Press, (1969). [http://www.spsl.nsc.ru/history/vernad/vol5/vgv522.htm Russian translation] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924105306/http://www.spsl.nsc.ru/history/vernad/vol5/vgv522.htm |date=24 September 2015 }}</ref><ref>Mikolaj Marchocki "Historia Wojny Moskiewskiej", ch. "Slaughter in the capital", [http://www.vostlit.info/Texts/rus8/Marchockij/pred.phtml?id=902 Russian translation] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170704181638/http://www.vostlit.info/Texts/rus8/Marchockij/pred.phtml?id=902 |date=4 July 2017 }}</ref><ref>Sergey Solovyov. History of Russia... Vol. 8, p. 847</ref> |

|||

The crisis provoked a patriotic national uprising against the [[invasion]], both in 1611 and 1612. A volunteer army, led by the merchant [[Kuzma Minin]] and prince [[Dmitry Pozharsky]], expelled the foreign forces from the capital on {{OldStyleDate|4 November|1612|22 October}}.<ref name=Dunning>Chester S L Dunning, ''Russia's First Civil War: The Time of Troubles and the Founding of the Romanov Dynasty'', [https://books.google.com/books?id=9NUYtSJaO8cC&dq=moscow+minin+patriot&pg=PA434 p. 434] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221030013949/https://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0271020741&id=9NUYtSJaO8cC&pg=PA434&lpg=PA434&dq=moscow+minin+patriot |date=30 October 2022 }} Penn State Press, 2001, {{ISBN|0-271-02074-1}}</ref><ref name=ToT>[https://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9073517 Troubles, Time of] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071218201128/http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9073517 |date=18 December 2007 }}." [[Encyclopædia Britannica]]. 2006</ref><ref>[http://www.bartleby.com/65/e-/E-Pozharsk.html Pozharski, Dmitri Mikhailovich, Prince] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081211151400/http://www.bartleby.com/65/e-/E-Pozharsk.html |date=11 December 2008 }}", [[Columbia Encyclopedia]]</ref> |

|||

Ivan's death in [[1584]] was followed by a period of civil wars known as the "[[Time of Troubles]]" over the succession and resurgence of the power of the nobility. |

|||

The |

The Russian statehood survived the "Time of Troubles" and the rule of weak or corrupt Tsars because of the strength of the government's central bureaucracy. Government functionaries continued to serve, regardless of the ruler's legitimacy or the faction controlling the throne.<ref name=Curtis2/> However, the Time of Troubles caused the loss of much territory to the [[Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth]] in [[Russo-Polish War (1605-1618)|the Russo-Polish war]], as well as to the [[Swedish Empire]] in the [[Ingrian War]]. |

||

=== |

===Accession of the Romanovs and early rule=== |

||

[[File:Election of Michael I of Russia by A. Krivshenko.jpg|thumb|left|Election of 16-year-old [[Michael I of Russia|Mikhail Romanov]], the first Tsar of the [[Romanov dynasty]]]] |

|||

In February 1613, after the chaos and expulsion of the Poles from Moscow, a [[Zemsky Sobor|national assembly]] elected [[Michael I of Russia|Michael Romanov]], the young son of [[Patriarch Filaret (Feodor Romanov)|Patriarch Filaret]], to the throne. The [[Romanov]] dynasty ruled Russia until 1917. |

|||

Order was restored in [[1613]] when [[Michael I of Russia|Michael Romanov]], the grandnephew of Ivan the Terrible was elected to the throne by a national assembly that included representatives from fifty cities. The Romanov dynasty ruled Russia until [[1917]]. The immediate task of the new dynasty was to restore order. Fortunately for Moscow, its major enemies, [[Poland]] and [[Sweden]], were engaged in a bitter conflict with each other, which provided Muscovy the opportunity to make peace with Sweden in [[1617]] and to sign a truce with Poland in [[1619]]. |

|||

The immediate task of the new monarch was to restore peace. Fortunately for Moscow, its major enemies, the [[Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth]] and [[Sweden]], were engaged in a bitter conflict with each other, which provided Russia the opportunity to make peace with Sweden in 1617 and to sign a truce with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1619. |

|||

Rather than risk their estates in more civil war, the great nobles or ''[[boyar]]s'' cooperated with the first Romanovs, enabling them to finish the work of bureaucratic centralization. Thus, the state required service from both the old and the new nobility, primarily in the military. In return the tsars allowed the ''boyars'' to complete the process of enserfing the peasants. In the preceding century, the state had gradually curtailed peasants' rights to move from one landlord to another. With the state now fully sanctioning sanctioned [[serfdom]], runaway peasants became state fugitives. Landlords had complete power over their peasants and bought, sold, traded, and mortgaged them. Together the state and the nobles placed the overwhelming burden of taxation on the peasants, whose rate was 100 times greater in the mid-seventeenth century than it had been a century earlier. In addition, middle-class urban tradesmen and craftsmen were assessed taxes, and, like the serfs, they were forbidden to change residence. All segments of the population were subject to military levy and to special taxes. |

|||

Recovery of lost territories began in the mid-17th century, when the [[Chmielnicki Uprising|Khmelnitsky Uprising]] (1648–1657) in Ukraine against Polish rule brought about the [[Treaty of Pereyaslav]] between Russia and the [[Ukrainian Cossacks]]. In the treaty, Russia granted protection to the [[Cossack Hetmanate|Cossacks state]] in [[Left-bank Ukraine]], formerly under Polish control. This triggered a prolonged [[Russo-Polish War (1654–1667)]], which ended with the [[Treaty of Andrusovo]], where Poland accepted the loss of Left-bank Ukraine, [[Kiev]] and [[Smolensk]].<ref name=Curtis2/> |

|||

===Peasant uprisings=== |

|||

The [[Russian conquest of Siberia]], begun at the end of the 16th century, continued in the 17th century. By the end of the 1640s, the Russians reached the Pacific Ocean, the Russian explorer [[Semyon Dezhnev]], discovered the strait between Asia and America. Russian expansion in the Far East faced resistance from [[Qing China]]. After the war between Russia and China, the [[Treaty of Nerchinsk]] was signed, delimiting the territories in the Amur region. |

|||

[[File:Соборное уложение глава 2.jpg|thumb|[[Sobornoye Ulozheniye]] was a legal code promulgated in 1649.]] |

|||

Rather than risk their estates in more civil war, the boyars cooperated with the first Romanovs, enabling them to finish the work of bureaucratic centralization. Thus, the state required service from both the old and the new nobility, primarily in the military. In return, the tsars allowed the boyars to complete the process of enserfing the peasants. |

|||

In the preceding century, the state had gradually curtailed peasants' rights to move from one landlord to another. With the state now fully sanctioning [[Russian serfdom|serfdom]], runaway peasants became state fugitives, and the power of the landlords over the peasants "attached" to their land had become almost complete. Together, the state and the nobles placed an overwhelming burden of taxation on the peasants, whose rate was 100 times greater in the mid-17th century than it had been a century earlier. Likewise, middle-class urban tradesmen and craftsmen were assessed taxes, and were forbidden to change residence. All segments of the population were subject to military levy and special taxes.<ref>For a discussion of the development of the class structure in Tsarist Russia see [[Theda Skocpol|Skocpol, Theda]]. ''[[States and Social Revolutions]]: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China''. Cambridge University Press, 1988.</ref> |

|||

In a period when peasant disorders were endemic, the greatest peasant uprising in the seventeenth century Europe erupted in [[1667]]. Incited by the [[Cossack]] [[Stenka Razin]], runaway serfs and Cossacks proclaimed a message of freedom, equality, and land for all. Stenka led his followers up the Volga River, inciting peasant uprisings and replacing local governments with Cossack rule. The tsar's army finally crushed his forces in [[1670]], a year before Stenka was captured and beheaded. The resulting repression that ended the last of the mid-century crises entailed the deaths of perhaps hundreds of thousands of peasants. |

|||

Riots among peasants and citizens of Moscow at this time were endemic and included the [[Salt Riot]] (1648),<ref name=Kotilaine>Jarmo Kotilaine and Marshall Poe, ''Modernizing Muscovy: Reform and Social Change in Seventeenth-Century Russia'', Routledge, 2004, p. 264. {{ISBN|0-415-30751-1}}.</ref> [[Copper Riot]] (1662),<ref name=Kotilaine/> and the [[Moscow Uprising of 1682|Moscow Uprising]] (1682).<ref>{{in lang|ru}} [http://militera.lib.ru/common/solovyev1/13_03.html Moscow Uprising of 1682] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170701155153/http://militera.lib.ru/common/solovyev1/13_03.html |date=1 July 2017 }} in the ''History of Russia'' of [[Sergey Solovyov (historian)|Sergey Solovyov]]</ref> By far the greatest peasant uprising in 17th-century Europe erupted in 1667. As the free settlers of South Russia, the [[Cossacks]], reacted against the growing centralization of the state, serfs escaped from their landlords and joined the rebels. The Cossack leader [[Stenka Razin]] led his followers up the Volga River, inciting peasant uprisings and replacing local governments with Cossack rule.<ref name=Curtis2/> The tsar's army finally crushed his forces in 1670; a year later Stenka was captured and beheaded. Yet, less than half a century later, the strains of military expeditions produced another [[Bulavin Rebellion|revolt in Astrakhan]], ultimately subdued. |

|||

==Imperial Russia== |

|||

''Main article: [[Imperial Russia]]'' |

|||

==Russian Empire (1721–1917)== |

|||

[[Image:1533-1896.gif|thumbnail|200px|left|A map of Russian expansion from 1533 to 1896. Ivan IV conquered the Tartar states of [[Kazan]] (1533-84) and [[Astrakhan]] (1556), gaining control of the Volga River down to the Caspian Sea. In addition, from the [[1580s]], the fur trade lured the Russians deep into Siberia across the [[Urals]]. Peter the Great concentrated on achieving a window on the West, wresting the Baltic region from Sweden in 1721. Catherine the Great annexed the Tartar khanate of [[Crimea]] and acquired parts of Poland. Russian forces subdued the Kazaks (1816-54), completed Russian control of the [[Caucasus]] (1857-64) and annexed the khanates of Central Asia (1865-76). China ceded to the tsar the [[Amur basin]] and parts of the Pacific Coast (where [[Vladivostok]] was founded in 1860), and leased [[Port Arthur]] (1898).]] |

|||

{{Main|Russian Empire}} |

|||

===Population=== |

|||

Much of Russia's expansion occurred in the 17th century, culminating in the [[history of Siberia|first Russian colonisation of the Pacific]] in the mid-17th century, the [[Russo-Polish War (1654–1667)]] that incorporated left-bank Ukraine, and the [[Russian conquest of Siberia]]. Poland was divided in the 1790–1815 era, with much of the land and population going to Russia. Most of the 19th century growth came from adding territory in Asia, south of Siberia.<ref>Brian Catchpole, ''A Map History of Russia'' (1974) pp 8–31; Martin Gilbert, ''Atlas of Russian history'' (1993) pp. 33–74.</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

|- |

|||

| width="60" | '''Year''' |

|||

| width="240pt" | '''Population of Russia (millions)'''<ref>Brian Catchpole, ''A Map History of Russia'' (1974) p. 25.</ref> |

|||

| width="300pt" | '''Notes''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1720 || 15.5 || includes new Baltic & Polish territories |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1795 || 37.6 || includes part of Poland |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1812 || 42.8 || includes Finland |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1816 || 73.0 || includes Congress Poland, Bessarabia |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1914 || 170.0 || includes new Asian territories |

|||

|} |

|||

===Peter the Great=== |

===Peter the Great=== |

||

[[File:Peter de Grote.jpg|thumb|Peter I, called "Peter the Great"]] |

|||

[[Peter |