Mitch McConnell

Mitch McConnell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Senate Majority Leader | |

| Assumed office January 3, 2015 | |

| Deputy | John Cornyn John Thune |

| Preceded by | Harry Reid |

| Senate Minority Leader | |

| In office January 3, 2007 – January 3, 2015 | |

| Deputy | Trent Lott Jon Kyl John Cornyn |

| Preceded by | Harry Reid |

| Succeeded by | Harry Reid |

| Senate Majority Whip | |

| In office January 3, 2003 – January 3, 2007 | |

| Leader | Bill Frist |

| Preceded by | Harry Reid |

| Succeeded by | Dick Durbin |

| United States Senator from Kentucky | |

| Assumed office January 3, 1985 Serving with Rand Paul | |

| Preceded by | Walter Dee Huddleston |

| Chair of the Senate Rules Committee | |

| In office January 20, 2001 – June 6, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Chris Dodd |

| Succeeded by | Chris Dodd |

| In office January 3, 1999 – January 3, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | John Warner |

| Succeeded by | Chris Dodd |

| Judge/Executive of Jefferson County | |

| In office 1977–1984 | |

| Preceded by | Todd Hollenbach III |

| Succeeded by | Bremer Ehrler |

| Acting United States Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legislative Affairs | |

| In office 1975 | |

| President | Gerald Ford |

| Preceded by | Vincent Rakestraw |

| Succeeded by | Michael Uhlmann |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Addison Mitchell McConnell Jr. February 20, 1942 Sheffield, Alabama, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) |

Sherrill Redmon

(m. 1968; div. 1980) |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | University of Louisville (BA) University of Kentucky (JD) |

| Signature | |

| Website | Senate website |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | July 9, 1967 to August 15, 1967 (37 days) (medical separation) |

| Unit | United States Army Reserve |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

U.S. Senator from Kentucky

|

||

Addison Mitchell McConnell Jr. (born February 20, 1942) is an American politician serving as Kentucky’s senior United States Senator and as Senate Majority Leader. McConnell is the second Kentuckian to lead his party in the Senate and is the longest-serving U.S. Senator from Kentucky in history.

A member of the Republican Party, McConnell was elected to the Senate in 1984 and has been re-elected five times since then. During the 1998 and 2000 election cycles, McConnell was chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee. McConnell was elected as Majority Whip in the 108th Congress and was re-elected to the post in 2004. In November 2006, McConnell was elected Senate Minority Leader; he held that post until 2015, when Republicans took control of the Senate and he became Senate Majority Leader.

McConnell was known as a pragmatist and a moderate Republican early in his political career but veered to the right over time. McConnell led opposition to stricter campaign finance laws, culminating in the Supreme Court ruling that partially overturned the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (McCain-Feingold) in 2009. During the Obama presidency, McConnell worked to withhold Republican support for major presidential initiatives; made frequent use of the filibuster; and blocked an unprecedented number of Obama's judicial nominees, including Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland. In 2015, McConnell was included in the Time 100 annual list of the most influential people in the world.

McConnell endorsed Rand Paul in the 2016 Republican primaries before ultimately supporting then-presumptive nominee Donald Trump. In 2016, after being approached by U.S. intelligence community officials, McConnell refused to give a bipartisan statement with President Obama warning Russia not to interfere in the upcoming election. During the Trump presidency, Senate Republicans, under McConnell's leadership, broke records on the number of judicial nominees confirmed; those nominees included Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, each of whom was confirmed to the Supreme Court. McConnell later described his decision to block the Garland nomination as "the most consequential decision I've made in my entire public career."

In June 2018, McConnell became the longest-serving Republican U.S. Senate leader in the history of the United States. McConnell's approval rating, as reflected by both national and statewide poll results, is consistently among the lowest of all senators.

Early life and education (1942–1967)

McConnell is of Scots-Irish and English descent, the son of Addison Mitchell McConnell, and his wife, Julia Odene "Dean" Shockley.[2] McConnell was born on February 20, 1942, in Sheffield, Alabama, and grew up in nearby Athens.[3] His ancestor had emigrated from County Down, Ireland to North Carolina.[2][4]

McConnell's upper left leg was paralyzed by a polio attack at the age of 2.[2][5] He received treatment at the Warm Springs Institute in Georgia, which potentially saved him from being disabled for the rest of his life.[6] McConnell has stated that his family "almost went broke" because of costs related to his illness.[7]

When he was eight, McConnell moved with his family from Athens to Augusta, Georgia when his father, who was in the Army, was stationed at Fort Gordon.[8] In 1956, his family moved to Louisville, where he attended duPont Manual High School.[8] McConnell was elected student council president at his high school during his junior year.[8] He graduated with honors from the University of Louisville with a B.A. in political science in 1964.[9] McConnell was president of the Student Council of the College of Arts and Sciences and a member of the Phi Kappa Tau fraternity.[10] He has maintained strong ties to his alma mater and is still "a rabid fan of the U of L Cardinals football and basketball teams."[10]

In 1964, at the age of 22, McConnell began interning for Senator John Sherman Cooper (R-KY), and his time with Cooper inspired him to later run for the Senate himself.[11]

In 1967, McConnell graduated from the University of Kentucky College of Law, where he was president of the Student Bar Association.[10][12]

Early career (1967–1984)

In March 1967, shortly before the expiration of his educational draft deferment upon graduation from law school, McConnell enlisted in the U.S. Army Reserve as a private at Louisville, Kentucky.[13] This was a coveted position because the Reserve units were mostly kept out of combat during the Vietnam War.[13][14] McConnell's first day of training at Fort Knox was July 9, 1967--two days after taking the bar exam--and his last day was August 15, 1967.[10][13] Shortly after his arrival, McConnell was diagnosed with optic neuritis and was deemed medically unfit for military service as a result.[13][15] After just five weeks at Fort Knox, he was honorably discharged.[13] McConnell's brief time in service has repeatedly been put at issue by his political opponents during his electoral campaigns.[13][15] Although McConnell has allowed reporters to examine parts of his military record and take notes, he has refused to allow copies to be made or to disclose his entire record, despite calls by his opponents to do so.[13] McConnell's time in service has also been the subject of criticism because his discharge was accelerated after his father placed a call to Senator John Sherman Cooper, who then sent a wire to the commanding general at Fort Knox on August 10, advising that "Mitchell [is] anxious to clear post in order to enroll in NYU."[13][14] He was allowed to leave post just five days later, though McConnell maintains that no one helped him with his enlistment into or discharge from the reserves.[13][14] According to McConnell, he struggled through the exercises at basic training and was sent to a doctor for a physical examination, which revealed McConnell's optic neuritis.[10] McConnell did not attend NYU.[13][14]

From 1968 to 1970, McConnell worked as an aide to Senator Marlow Cook (R-KY), managing a legislative department consisting of five members as well as assisting with speech writing and constituent services.[16]

In 1971, McConnell returned from Washington, D.C., to Louisville, where he worked for Tom Emberton's candidacy for Governor of Kentucky, which was unsuccessful.[16] McConnell attempted to run for a seat in the state legislature, but was disqualified because he did not meet the residency requirements for the office.[16] McConnell then went to work for a law firm for a few years.[16] During the same time period, McConnell taught a night class on political science at the University of Louisville.[12][17][18]

In October 1974, McConnell returned to D.C. to fill a position as Deputy Assistant Attorney General under President Gerald R. Ford, where he worked alongside Robert Bork, Laurence Silberman, and Antonin Scalia.[12][16]

In 1977, McConnell was elected the Jefferson County Judge/Executive, the former top political office in Jefferson County, Kentucky. He was re-elected in 1981 and occupied this office until his election to the U.S. Senate in 1984.[11][16]

U.S. Senate (1985–present)

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

In the 1984 Senate election, McConnell defeated his Democratic opponent, Walter "Dee" Huddleston, by the slimmest of margins: about 5,100 votes.[19] He was the first Republican to win a statewide election in Kentucky since 1968, and benefited from the popularity of President Ronald Reagan, up for reelection, who was supported by 60% of Kentucky voters in the same year.[19][20] McConnell began his first term as a junior senator in 1985.[21][22]

In his early years as a politician in Kentucky, McConnell was known as a pragmatist and a moderate Republican.[11][23] Over time, he veered sharply to the right.[11][23] According to ProPublica reporter Alex MacGillis's biography of McConnell, McConnell transformed "from a moderate Republican who supported abortion rights and public employee unions to the embodiment of partisan obstructionism and conservative orthodoxy on Capitol Hill."[23] MacGillis argues that McConnell's transformation was "driven less by a shift in ideological conviction than by a desire to win elections and stay in power at all costs."[23]

McConnell has been widely described as having engaged in obstructionism during Obama's presidency.[24][25][26][27] In October 2010, McConnell said that "the single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president." Asked whether this meant "endless, or at least frequent, confrontation with the president," McConnell clarified that "if [Obama is] willing to meet us halfway on some of the biggest issues, it's not inappropriate for us to do business with him."[28] During Obama's presidency, minority obstruction reached all-time highs, as McConnell insisted that any bill passing through the Senate needed a supermajority (60 votes rather than 50).[29] McConnell justified the obstructionism by falsely claiming that the 60-vote threshold was the historical norm in the Senate.[29] Yale University political scientist Jacob Hacker and University of California, Berkeley political scientist Paul Pierson describe McConnell as the major figure (along with Newt Gingrich) in transforming the Republican Party into a "party geared increasingly not to governing but to making governance impossible".[30] They write, "Facing off against Obama, he worked to deny even minimal Republican support for major presidential initiatives—initiatives that were, as a rule, in keeping with the moderate model of decades past, and often with moderate Republican stances of a few years past."[30] Republicans threatened repeatedly to force the United States to default on its debt, with McConnell saying that he learned from the 2011 debt-ceiling crisis that "it's a hostage that's worth ransoming."[31][27]

Political scientists have referred to McConnell's use of the filibuster as "constitutional hardball", referring to the misuse of procedural tools in a way that undermines democracy.[32][30][31][33] By 2013, when Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid eliminated the filibuster for all presidential nominations except the Supreme Court, nearly half of all invocations to cloture (to end a filibuster) in the history of the Senate had occurred during Obama's presidency.[34] McConnell delayed and obstructed health care reform and banking reform, which were the two landmark pieces of legislation that Democrats sought to get passed early in Obama's tenure.[35][36] By delaying Democratic priority legislation, McConnell stymied the output of Congress. Political scientists Eric Schickler and Gregory J. Wawro write, "by slowing action even on measures supported by many Republicans, McConnell capitalized on the scarcity of floor time, forcing Democratic leaders into difficult trade-offs concerning which measures were worth pursuing. That is, given that Democrats had just two years with sizeable majorities to enact as much of their agenda as possible, slowing the Senate's ability to process even routine measures limited the sheer volume of liberal bills that could be adopted."[36]

The New York Times noted early during Obama's administration that "on the major issues—not just health care, but financial regulation and the economic stimulus package, among others—Mr. McConnell has held Republican defections to somewhere between minimal and nonexistent, allowing him to slow the Democratic agenda if not defeat aspects of it."[26] McConnell's refusal to allow Obama to seat a Supreme Court justice was described by political scientists and legal scholars as "unprecedented",[37] a "culmination of this confrontational style,"[38] a "blatant abuse of constitutional norms,"[39] and a "classic example of constitutional hardball."[31] As part of his obstruction strategy and as the leading Republican senator, McConnell confronted and pressured other Republican senators who cared about policy substance and were willing to negotiate with Democrats and the Obama administration.[40] According to Purdue University political scientist Bert A. Rockman, "pure party line voting has been evident now for some time ... but rarely has the tactic of "oppositionism" been so boldly stated as McConnell did."[41] In 2012, McConnell proposed a measure allowing President Obama to raise the debt ceiling, hoping that some Democratic senators would oppose the measure, thus demonstrating disunity among Democrats. However, all Democratic senators supported the proposal, which led McConnell to filibuster his own proposal.[42] Democrats chided McConnell for this, saying it demonstrated an extreme degree of obstructionism.[43] The 2016 book Health Care Reform and American Politics by political scientists Lawrence Jacobs and Theda Skocpol describe McConnell's rationale as follows, "any compromises would undermine the Republican Party's effort to make big gains in 2010 and 2012."[40] According to University of Texas legal scholar Sanford Levinson, McConnell learned that obstruction and Republican unity was the optimal way to ensure Republican gains in upcoming elections after he observed how Democratic cooperation with the Bush administration on No Child Left Behind and Medicare Part D helped Bush's 2004 re-election.[44] Levinson noted, "McConnell altogether rationally ... concluded that Republicans have nothing to gain, as a political party, from collaborating in anything that the president could then claim as an achievement." Hacker and Pierson describe the rationale behind McConnell's filibusters as follows:[30]

Filibusters left no fingerprints. When voters heard that legislation had been "defeated," journalists rarely highlighted that this defeat meant a minority had blocked a majority. Not only did this strategy produce an atmosphere of gridlock and dysfunction; it also chewed up the Senate calendar, restricting the range of issues on which Democrats could progress. McConnell knew proposals lost support the longer they were out there, subject to attack. He knew constant delay would drive down the approval ratings of Democrats ... Like Gingrich, McConnell had found a serious flaw in the code of American democracy: Our distinctive political system gives an antigovernment party with a willingness to cripple governance an enormous edge. With the strategic guidance of these two congressional leaders, Republicans launched a self-reinforcing antistatist cycle. First they made government less functional. Then they highlighted that dysfunction to build political support.

However, according to University of California, Los Angeles political scientist Barbara Sinclair, McConnell had to manage a balancing act where he "need[ed] to protect his party's reputation so he [did] not want to chance its being seen as responsible for a complete breakdown."[45]

A number of political scientists, historians and legal scholars have characterized McConnell's obstructionism and constitutional hardball as contributors to democratic erosion in the United States.[30][39][32][34][46] University of North Carolina historian Christopher Browning wrote:[47]

If the US has someone whom historians will look back on as the gravedigger of American democracy, it is Mitch McConnell. He stoked the hyperpolarization of American politics to make the Obama presidency as dysfunctional and paralyzed as he possibly could. As with parliamentary gridlock in Weimar, congressional gridlock in the US has diminished respect for democratic norms, allowing McConnell to trample them even more. Nowhere is this vicious circle clearer than in the obliteration of traditional precedents concerning judicial appointments. Systematic obstruction of nominations in Obama's first term provoked Democrats to scrap the filibuster for all but Supreme Court nominations. Then McConnell's unprecedented blocking of the Merrick Garland nomination required him in turn to scrap the filibuster for Supreme Court nominations in order to complete the "steal" of Antonin Scalia's seat and confirm Neil Gorsuch.

Dartmouth political scientist Russell Muirhead characterized McConnell's obstructionism as a corrosive form of partisanship:[48]

When the number one goal is electoral victory (or, in this case, another candidate's defeat), base power seeking obscures the larger purposes that make seeking power something respectable. It was not necessarily wrong or unreasonable of McConnell to hope that a Republican would defeat Obama. It was wrong to cast this as the number one goal of the party, prior to everything else—debt reduction, tax policy, foreign relations, and the other issues that make the party something ordinary citizens might have a reason to care about. When low partisanship displaces anything higher ... causes, principles, convictions lose their force and their allure, and become just the veil that makes power-seeking behavior presentable.

McConnell has gained a reputation as a skilled political strategist and tactician.[49][50][51][20] However, this reputation dimmed after Republicans failed to repeal the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) in 2017 during consolidated Republican control of government.[52][53][54][55]

In 2015, Time listed McConnell as one of the 100 most influential people in the world.[56]

With a 49% disapproval rate in 2016, McConnell had the highest disapproval rating of all senators.[57] McConnell has repeatedly been found to have the lowest home state approval rating of any sitting senator.[58][59]

Committee assignments

- Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry

- Committee on Appropriations

- Subcommittee on Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies

- Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies

- Subcommittee on Defense

- Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development

- Subcommittee on Military Construction and Veterans' Affairs, and Related Agencies

- Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs

- Committee on Rules and Administration

- Select Committee on Intelligence (Ex officio)

Leadership

From 1997 to 2001, McConnell was chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, the body charged with securing electoral victories for Republicans.[60][61] Republicans maintained control of the Senate after both elections. He was first elected as Majority Whip in the 108th Congress[62] and unanimously re-elected on November 17, 2004. Senator Bill Frist, the Majority Leader, did not seek re-election in the 2006 elections. In November 2006, after Republicans lost control of the Senate, they elected McConnell to replace Frist as Minority Leader.[63] After Republicans took control of the Senate following the 2014 Senate elections, McConnell became the Senate Majority Leader.[64] In June 2018, McConnell became the longest-serving Senate Republican leader in the history of the United States.[65] McConnell is the second Kentuckian to lead his party in the Senate[9] and is the longest-serving U.S. Senator from Kentucky in history.[66]

2016 presidential election and Donald Trump

McConnell initially endorsed fellow Kentucky Senator Rand Paul during the 2016 presidential campaign. Following Paul's withdrawal from the race in February 2016, McConnell did not endorse another candidate until May 4, 2016 when he endorsed then-presumptive nominee Donald Trump. "I have committed to supporting the nominee chosen by Republican voters, and Donald Trump, the presumptive nominee, is now on the verge of clinching the nomination."[67] However, McConnell disagreed with Trump on multiple subsequent occasions. In May 2016, after Trump suggested that federal judge Gonzalo P. Curiel was biased against Trump because of his Mexican heritage, McConnell responded, "I don't agree with what he (Trump) had to say. This is a man who was born in Indiana. All of us came here from somewhere else." In July 2016, after Trump had criticized the parents of Capt. Humayun Khan, a Muslim soldier who was killed in Iraq, McConnell stated, "Captain Khan was an American hero, and like all Americans, I'm grateful for the sacrifices that selfless young men like Captain Khan and their families have made in the war on terror. All Americans should value the patriotic service of the patriots who volunteer to selflessly defend us in the armed services." On October 7, 2016, following the Donald Trump Access Hollywood controversy, McConnell stated: "As the father of three daughters, I strongly believe that Trump needs to apologize directly to women and girls everywhere, and take full responsibility for the utter lack of respect for women shown in his comments on that tape."[68]

With regard to the US response to intelligence findings that Russia was responsible for cyberattacks undertaken to influence the American election, after Trump won the election, Senator McConnell expressed "support for investigating American intelligence findings that Moscow intervened."[69] Prior to the election, however, when FBI Director James Comey, Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson and other officials met with the leadership of both parties to make the case for a bipartisan statement warning Russia that such actions would not be tolerated, "McConnell raised doubts about the underlying intelligence and made clear to the administration that he would consider any effort by the White House to challenge the Russians publicly an act of partisan politics," The Washington Post reported,[70] citing accounts of several unnamed officials.[71][72]

In April 2017, McConnell denied knowing of any potential wiretapping of Trump by the Obama administration, saying there was an ongoing investigation.[73]

In October 2017, in response to criticism from White House chief strategist Stephen Bannon and other Trump allies blaming McConnell for stalling the Trump administration's legislation, McConnell stated that he was trustful of President Trump as a negotiating partner and cited the confirmation of Neil Gorsuch as an Associate Justice along with other Trump nominees for executive and judicial positions being confirmed as proof that the Senate was supportive of Trump's legislation. McConnell added that the "inter-party skirmish" of the GOP was really about "specialists in defeating Republican candidates in November" and the Republicans' goal was "to nominate people in the primaries next year who can actually win, and the people who win will be the ones who enact the president's agenda."[74]

In November 2017, McConnell opposed legislation that would have protected Special Counsel Robert Mueller's investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election.[75] In April 2018, less than 24 hours after an FBI raid on Michael Cohen's (President Trump's personal attorney) office, and after Trump had said that "many people" had asked him to fire Mueller, McConnell reiterated that he opposed any legislation to protect Mueller's investigation.[76] Later that month, McConnell thwarted a bipartisan legislative effort to protect Mueller's investigation.[77]

In January 2018, Senators Marco Rubio and Chris Van Hollen introduced a bipartisan bill that would impose new sanctions on Russia in the event the country attempted interfering in another American election. In July, McConnell mentioned the bill as one option on the table for the Senate to respond to President Trump's posture toward the government of Vladimir Putin and asked the Banking and Foreign Relations panels to hold new hearings on the implementation of the bipartisan Russia sanctions bill from the previous year in addition to suggesting potential further steps lawmakers could pursue as part of efforts to counter Russian malfeasance ahead of that year's midterm elections.[78]

In March 2018, after President Trump criticized Mueller for hiring investigators who were registered as Democrats, McConnell praised Mueller's selection as Special Counsel and stated of Mueller, "I think he will go wherever the facts lead him, and I think he will have great credibility with the American people when he reaches the conclusion of this investigation, so I have a lot of confidence." He predicted that Mueller was not "going anywhere" and earned praise from Senate Minority Leader Schumer for doing "the right thing" in lauding Mueller's integrity.[79]

In June 2018, McConnell said regarding the Mueller investigation: "they ought to wrap it up. It's gone on seemingly forever and I don't know how much more they think they can find out." By that time, the Mueller investigation had been open for just over a year while the average length of 16 special/independent counsel investigations from 1973–2003 was over three years.[80]

In July 2018, McConnell's chief strategist said that Trump's attacks on the intelligence community would benefit Republicans in the upcoming 2018 midterm election, both by energizing the Republican base and by drowning out Democrats' messaging on policy.[81]

In November 2018, McConnell told reporters that legislation protecting Mueller was unnecessary and a bill by Jeff Flake would not come up in the Senate since Mueller was "not under threat", citing President Trump as having repeatedly stated the investigation would be allowed to finish. McConnell opined that he could not imagine Trump dismissing the investigation and told reporters they were "trying to get me to speculate about things that I'm confident are not going to happen."[82]

Campaign finance

McConnell led opposition to stricter campaign finance regulations, with the Lexington Herald Leader describing it as McConnell's "pet issue."[17] He has argued that campaign finance regulations reduce participation in political campaigns and protect incumbents from competition.[83] He spearheaded the movement against the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (known since 1995 as the "McCain–Feingold bill" and from 1989 to 1994 as the "Boren–Mitchell bill"), calling it "neither fair, nor balanced, nor constitutional."[84] His opposition to the bill culminated in the 2003 Supreme Court case McConnell v. Federal Election Commission and the 2009 Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, the latter of which ruled part of the act unconstitutional. McConnell has been an advocate for free speech at least as far back as the early 1970s when he was teaching night courses at the University of Louisville. "No issue has shaped his career more than the intersection of campaign financing and free speech," political reporter Robert Costa wrote in 2012.[85] In a recording of a 2014 fundraiser McConnell expressed his disapproval of the McCain-Feingold law, saying, "The worst day of my political life was when President George W. Bush signed McCain-Feingold into law in the early part of his first Administration."[86]

On January 2, 2013, the Public Campaign Action Fund, a liberal nonprofit group that backs stronger campaign finance regulation, released a report highlighting eight instances from McConnell's political career in which a vote or a blocked vote (filibuster), coincided with an influx of campaign contributions to McConnell's campaign.[87][88]

In December 2018, McConnell opposed a Democratic resolution that overturned IRS guidance to reduce the amount of donor information certain tax-exempt groups would have to give the IRS, saying, "In a climate that is increasingly hostile to certain kinds of political expression and open debate, the last thing Washington needs to do is to chill the exercise of free speech and add to the sense of intimidation."[89]

Criminal justice reform

In late 2018, McConnell stalled the passage of a bipartisan criminal justice reform bill in the Senate. As of December 2018, McConnell had yet to endorse the prison and sentencing reform bill. President Trump had endorsed the bill, saying "Really good Criminal Justice Reform has a true shot at major bipartisan support ... Would be a major victory for ALL!"[90] Democratic Senators Dick Durbin and Kamala Harris said that McConnell was the only impediment to the passage of the bill.[91][90] Republican Senator Chuck Grassley said, "If McConnell will bring this up, it will pass overwhelmingly."[92][93] The bill was expected to easily pass the House.[92]

Economy

In 2010, McConnell requested earmarks for the defense contractor BAE Systems while the company was under investigation by the Department of Justice for alleged bribery of foreign officials.[94][unreliable source?][95]

In June 2011, McConnell introduced a Constitutional Balanced Budget Amendment. The amendment would require two-thirds votes in Congress to increase taxes or for federal spending to exceed the current year's tax receipts or 18% of the prior year's GDP. The amendment specifies situations when these requirements would be waived.[96][97]

During the Great Recession, as Congress and the Obama administration negotiated reforms of the banking system, McConnell played an important role in preventing the addition of a provision requiring banks to prefund a reserve intended to be used to rescue insolvent banks in the future. When there appeared to be bipartisan and majority support for such a bank-funded reserve, McConnell criticized the provision, referred to it as a "bailout fund" and turned "opposition to it a litmus test for Senate Republicans", according to one study.[98] According to the study, "McConnell's attack, along with his insistence that opposition would be a matter of party principle, undermined the fragile coalition supporting the prefunded reserve, and the White House—fearing that advocating a bank levy as part of the president's broader reform would enable opponents to kill the whole bill—shelved the idea."[98]

After two intercessions to get federal grants for Alltech, whose president T. Pearse Lyons made subsequent campaign contributions to McConnell, to build a plant in Kentucky for producing ethanol from algae, corncobs, and switchgrass, McConnell criticized President Obama in 2012 for twice mentioning biofuel production from algae in a speech touting his "all-of-the-above" energy policy.[99][100]

In 2014, McConnell voted to help break Ted Cruz's filibuster attempt against a debt limit increase and then against the bill itself.[101] In 2014, McConnell opposed the Paycheck Fairness Act (a bill that "punishes employers for retaliating against workers who share wage information, puts the justification burden on employers as to why someone is paid less and allows workers to sue for punitive damages of wage discrimination") because it would "line the pockets of trial lawyers", not help women.[102]

In July 2014, McConnell expressed opposition to a U.S. Senate bill that would limit the practice of corporate inversion by U.S. corporations seeking to limit U.S. tax liability.[103]

Environment

In 1992, after the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had concluded that human activities significantly contribute to climate change, McConnell stated that there was "no conclusive evidence of significant long-term global warming", that there was no scientific consensus on the subject, misleadingly claimed that scientists were alarmed about global cooling in the 1970s, and that climate mitigation efforts would be "the most expensive attack on jobs and the economy in this country."[104][105][106] In 2014, McConnell continued to expressed skepticism that climate change was a problem, telling the Cincinnati Enquirer editorial board, "I'm not a scientist, I am interested in protecting Kentucky's economy, I'm interested in having low cost electricity."[107][108][109] McConnell was the sponsor of the Gas Price Reduction Act of 2008, which would have allowed states to engage in increased offshore and domestic oil exploration.[110] In 2015, McConnell encouraged state governors not to comply with the Obama administration's Clean Power Plan, which was aimed at tackling climate change.[111][112]

In December 2014, McConnell stated that the incoming Republican-controlled Senate's first priority would be approving the Keystone XL pipeline, announcing his intent to allow a vote on legislation in favor of the pipeline by John Hoeven and his hope "that senators on both sides will offer energy-related amendments, but there will be no effort to micromanage the amendment process." McConnell disputed that the Keystone XL pipeline would harm the environment by citing fellow Republican senator Lisa Murkowski's claim that the US already had nineteen pipelines in effect and multiple studies "showing over and over again no measurable harm to the environment." He furthered that the pipeline would create high paying jobs and had received bipartisan support.[113] In February 2015, President Obama vetoed the Keystone XL bill on the grounds that it conflicted "with established executive branch procedures and cuts short thorough consideration of issues that could bear on our national interest”.[114] The following month, the Senate was unable to reach a two-thirds majority to override the veto, McConnell afterward stating that the veto represented "a victory for partisanship and for powerful special interests" and "a defeat for jobs, infrastructure, and the middle class."[115]

In November 2016, McConnell requested that President-elect Trump prioritize the approval of the Keystone XL pipeline upon taking office during a meeting and told reporters that President Obama "sat on the Keystone pipeline throughout his entire eight years, even though his own State Department said it had no measurable impact on climate."[116]

McConnell was one of 22 Republican senators to sign a letter urging President Donald Trump to have the United States withdraw from the Paris Agreement. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, McConnell has received over $1.5 million from the oil and gas industry since 2012.[117][118]

Flag Desecration Amendment

McConnell opposed the Flag Desecration Amendment to the Constitution in 2000. McConnell offered an amendment to the measure that would have made flag desecration illegal as a statutory crime, not by amending the Constitution.[119]

Foreign policy

In 1985, McConnell backed anti-apartheid legislation with Chris Dodd.[120] McConnell went on to engineer new IMF funding to "faithfully protect aid to Egypt and Israel," and "promote free elections and better treatment of Muslim refugees" in Myanmar, Cambodia and Macedonia. According to a March 2014 article in Politico, "McConnell was a 'go-to guy' for presidents of both parties seeking foreign aid," but he has lost some of his idealism and has evolved to be more wary of foreign assistance.[121]

In August 2007, McConnell introduced the Protect America Act of 2007, which allowed the National Security Agency to monitor telephone and electronic communications of suspected terrorists outside the United States without obtaining a warrant.[122]

In December 2010, McConnell was one of twenty-six senators who voted against the ratification of New Start,[123] a nuclear arms reduction treaty between the United States and Russian Federation obliging both countries to have no more than 1,550 strategic warheads as well as 700 launchers deployed during the next seven years along with providing a continuation of on-site inspections that halted when START I expired the previous year. It was the first arms treaty with Russia in eight years.[124]

On March 27, 2014, McConnell introduced the United States International Programming to Ukraine and Neighboring Regions bill, which would provide additional funding and instructions to Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in response to the 2014 Crimea crisis.[125][126]

In September 2016, the Senate voted 71 to 27 against the Chris Murphy–Rand Paul resolution to block the $1.15 billion arms deal with Saudi Arabia.[127] The Saudi Arabian-led coalition in Yemen has been accused of war crimes.[127] Following the vote, McConnell said: "I think it's important to the United States to maintain as good a relationship with Saudi Arabia as possible."[128] In November 2018, McConnell stated that the killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi "is completely abhorrent to everything the United States holds dear and stands for in the world", reasoning that this contrast warranted a response from the US.[129] He later expressed opposition to a complete fracture in relations between the US and Saudi Arabia as not in the "best interest long term" and added that Saudi Arabia had been a "great" ally of the US as it related to Iran.[130] On December 12, McConnell advocated for the Senate to reject a measure authored by Bernie Sanders and Mike Lee that would end American support for the Saudi-led military campaign in Yemen, calling the resolution "neither precise enough or prudent enough." McConnell endorsed a resolution by Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker, which if enacted would charge crown prince of Saudi Arabia Mohammed bin Salman with Khashoggi's death, as doing "a good job capturing bipartisan concerns about the war in Yemen and the behavior of Saudi partners more broadly without triggering an extended debate over war powers while we hasten to finish all our other work."[131]

Also in September 2016, both the Senate and the House of Representatives overrode President Obama's veto to pass the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (JASTA), which targets Saudi Arabia, into law. Despite McConnell voting to override the President, McConnell would criticize JASTA within a day of the bill's passing, saying that it might have "unintended ramifications". McConnell appeared to blame the White House regarding this as he quoted that there was "failure to communicate early about the potential consequences" of JASTA, and said he told Obama that JASTA "was an example of an issue that we should have talked about much earlier".[132][133] In vetoing the bill, Obama had provided three reasons for objecting to JASTA: that the courts would be less effective than "national security and foreign policy professionals" in responding to a foreign government supporting terrorism, that it would upset "longstanding international principles regarding sovereign immunity", and that it would complicate international relations.[134][135]

In January 2017, McConnell signed onto a resolution authored by Marco Rubio and Ben Cardin objecting to United Nations Security Council Resolution 2334, which condemned Israeli settlement building in the occupied Palestinian territories as a violation of international law, and calling for all American presidents to "uphold the practice of vetoing all United Nations Security Council resolutions that seek to insert the Council into the peace process, recognize unilateral Palestinian actions including declaration of a Palestinian state, or dictate terms and a timeline for a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict."[136]

In April 2017, McConnell organized a White House briefing of all senators conducted by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. Defense Secretary James Mattis, Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats, and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Joseph Dunford regarding threats from the North Korean government.[137] In May 2018, after President Trump called off the North Korea–United States summit, McConnell said that Trump "wanted to make sure that North Koreans understood he was serious, willing to engage, provided they didn't continue to play these kinds of games as they've historically done with other administrations and gotten away with it" and that further progress would be staked on the subsequent actions of North Korea.[138] Trump shortly thereafter announced that the summit could resume as scheduled following a "very nice statement" he received from North Korea and that talks were now resuming.[139] At the Greater Louisville Inc. Congressional Summit, McConnell stated that North Korea would likely pursue "sanctions and other relief" while giving up as little as possible; he added that to achieve a successful negotiation, Trump would "have to not want the deal too much".[140]

In August 2018, McConnell said Myanmar's civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who has been accused of ignoring the genocide of Myanmar's Rohingya Muslim minority, could not be blamed for atrocities committed by the Myanmar's armed forces.[141]

Cuba

McConnell supported sanctions on Cuba for most of his Senate career, including the trade embargo imposed by the United States during the presidency of John F. Kennedy.[142]

In December 2014, McConnell announced his opposition to the Obama administration's intent to normalize American relations with Cuba, calling it "a mistake" and that Congress would be able to intervene due to multiple sanctions having been implemented into law along with any American ambassador to Cuba requiring Senate approval. McConnell noted the US normalizing relations with Vietnam as its government continued repressing denizens as an example of American engagement sometimes not working.[143]

In a July 2015 interview, McConnell stated that Obama believed that the US would "get a positive result" by merely engaging Cuba and that he saw no evidence in Cuba changing its behavior.[144]

In March 2016, following Obama's travel to Cuba, McConnell said that for Obama "to go down there and act like this is a normal regime, has been embarrassing" while stating that the president believed engagement with Cuba was "going to improve things."[142] After the death of Fidel Castro later that year, McConnell said the passing was an opportunity for the Cuban government to reform itself toward the principles of freedom and democracy, adding that "the oppression" Castro imposed remained in Cuba despite his death.[145]

Iran

In August 2015, McConnell charged President Obama with treating his rallying for support of the Iran nuclear deal "like a political campaign" and stated his preference for senators spending time in their seats while debating the deal: "Demonize your opponents, gin up the base, get Democrats all angry and, you know, rally around the president. To me, it's a different kind of issue."[146] In a September interview, McConnell stated that the battle over the Iran nuclear deal possibly would have to wait until after the Obama administration was over while vowing to tee another vote on the matter to show bipartisan opposition to the matter. He said the Iran nuclear deal would be a defining issue in the following presidential election in the event that the Republicans still did not have enough votes to overcome a filibuster from Democrats and called the deal "an agreement between Barack Obama and the Iranian regime."[147]

In January 2016, as the Senate Foreign Relations Committee weighed consideration of sanctions on North Korea after its test of a nuclear device, McConnell called Iran "an obvious rogue regime with which we have this outrageous deal that they don't intend to comply with" and confirmed the intent of the Senate to look into Iran.[148] In May, McConnell called for Democrats to vote for an underlying spending bill ahead of authorizing the appropriations process to move forward as Democrats opposed the measure on the grounds of a Republican amendment related to Iran. After their third filibuster on the bill, McConnell set up a vote on both the Iran amendment and spending bill.[149]

In September 2016, McConnell was one of thirty-four senators to sign a letter to United States Secretary of State John Kerry advocating for the United States using "all available tools to dissuade Russia from continuing its airstrikes in Syria" from an Iranian airbase near the city of Hamadan, and stating that there should be clear enforcement by the US of the airstrikes violating "a legally binding Security Council Resolution" on Iran.[150]

In May 2018, after President Trump announced the United States was withdrawing from the Iran nuclear deal, McConnell said the deal was "a flawed deal and we can do better" and stated congressional optimism to seeing what Trump would propose in its place.[151]

Iraq

In October 2002, McConnell voted for the Iraq Resolution, which authorized military action against Iraq.[152] McConnell supported the Iraq War troop surge of 2007.[153] In 2010, McConnell "accused the White House of being more concerned about a messaging strategy than prosecuting a war against terrorism."[154]

In 2006, McConnell publicly criticized Senate Democrats for urging that troops be brought back from Iraq.[155] According to Bush's Decision Points memoir, however, McConnell was privately urging the then President to "bring some troops home from Iraq" to lessen the political risks. McConnell's hometown paper, the Louisville Courier-Journal, in an editorial titled "McConnell's True Colors", criticized McConnell for his actions and asked him to "explain why the fortunes of the Republican Party are of greater importance than the safety of the United States."[156]

Regarding the failure of the Iraqi government to make reforms, McConnell said the following on Late Edition with Wolf Blitzer: "The Iraqi government is a huge disappointment. Republicans overwhelmingly feel disappointed about the Iraqi government. I read just this week that a significant number of the Iraqi parliament want to vote to ask us to leave. I want to assure you, Wolf, if they vote to ask us to leave, we'll be glad to comply with their request."[157]

On April 21, 2009, McConnell delivered a speech to the Senate criticizing President Obama's plans to close the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba, and questioned the additional 81 million dollar White House request for funds to transfer prisoners to the United States.[158][159]

In July 2011, following the acquittal of Casey Anthony in the murder of her daughter Caylee, McConnell stated the trial showed "how difficult is to get a conviction in a U.S. court" and advocated for foreign-born terrorists to be sent to Guantanamo Bay.[160]

Syria

McConnell was the only party leader in Congress to oppose the resolution that would authorize military strikes against Syria in September 2013, citing a lack of national security risk.[161]

In January 2016, McConnell delivered a Senate floor speech endorsing the Senate voting to approve of a bill requiring additional FBI background checks and individual sign-offs from three high-ranking federal officials before before refugees from either Syria or Iraq were admitted to the United States.[162]

McConnell supported the 2017 Shayrat missile strike, saying it "was well-planned, well-executed, went right to the heart of the matter, which is using chemical weapons."[163]

In April 2018, following the missile strikes against Syria carried out by the United States, France, and the United Kingdom, McConnell said he found it "an appropriate and measured response to the use of chemical weapons" when asked of the Trump administration's legal justification for the authorization of military action.[164]

In January 2019, McConnell joined Marco Rubio, Jim Risch, and Cory Gardner in introducing legislation that would impose sanctions on the government of President of Syria Bashar al-Assad and bolster American cooperation with Israel and Jordan. McConnell stated that the legislation spoke "directly to some critical American interests in that part of the world" and affirmed "that the United States needs to walk the walk and authorize military assistance, cooperative missile defense as well as loan guarantees."[165] McConnell introduced an amendment warning the Trump administration against "precipitous" withdrawals of American troops in Syria and Afghanistan, saying he chose to introduce it "so the Senate can speak clearly and directly about the importance of our nation’s ongoing missions in Afghanistan and Syria."The amendment was approved 70-26 on February 4.[166]

Fundraising

From 2003 to 2008, the list of McConnell's top 20 donors included five financial/investment firms: UBS, FMR Corporation (Fidelity Investments), Citigroup, Bank of New York, and Merrill Lynch.[167]

In April 2010, while Congress was considering financial reform legislation, a reporter asked McConnell if he was "doing the bidding of the large banks." McConnell has received more money in donations from the "Finance, Insurance and Real Estate" sector than any other sector according to the Center for Responsive Politics.[167][168] McConnell responded "I'd say that that's inaccurate. You could talk to the community bankers in Kentucky." The Democratic Party's plan for financial reform is actually a way to institute "endless taxpayer funded bailouts for big Wall Street banks", said McConnell. He expressed concern that the proposed $50 billion, bank-funded fund that would be used to liquidate financial firms that could collapse "would of course immediately signal to everyone that the government is ready to bail out large banks".[167][168] In McConnell's home state of Kentucky, the Lexington Herald-Leader ran an editorial saying: "We have read that the Republicans have a plan for financial reform, but McConnell isn't talking up any solutions, just trashing the other side's ideas with no respect for the truth."[169] According to one tally, McConnell's largest donor from the period from January 1, 2009, to September 30, 2015, was Bob McNair, contributing $1,502,500.[170]

Government shutdowns

The United States federal government shutdown between October 1 to October 17, 2013 following a failure to enact legislation appropriating funds for fiscal year 2014 nor a continuing resolution for the interim authorization of appropriations for fiscal year 2014 in time. During a fundraising retreat in Sea Island, Georgia weeks later, McConnell stated that Republicans would not default on the US's debt or shut down the government early the following year, when stop-gap government funding and the debt ceiling were slated to be voted on again. McConnell furthered that Republicans were willing to combat tactics of the party’s wing that was opposed to the establishment in addition to responding to individuals who believed words such as "negotiate" and "compromise" were bad things.[171]

In July 2018, McConnell stated that funding for the Mexico–United States border wall would likely have to wait until the midterms had concluded, President Trump tweeting two days later that he was willing to allow a government shutdown.[172] The August approval of a third minibus package of spending bills was seen as a victory for McConnell in his attempts to prevent another government shutdown.[173]

In December 2018, after the federal government shutdown commenced, McConnell charged Senate Democrats with turning down a "reasonable request" in their refusal of a bill passed in the House including $5.7 billion for the border in spite of previously offering $25 billion earlier that year as part of a larger immigration deal and that Democrats "brought this about because they're under a lot of pressure—we all know this—from their far left and feel compelled to disagree with the president on almost anything, and certainly this."[174] On January 2, 2019, McConnell met with President Trump, congressional leaders, and Homeland Security Department officials, McConnell relating afterward that they were "hopeful that somehow in the coming days and weeks we'll be able to reach an agreement" while admitting there was still no consensus reached between both sides.[175] By January 23, McConnell had blocked four Senate bills to reopen the government and a bill funding the Homeland Security Department through February 8. McConnell called for Democrats to support a Trump administration-backed measure that included 5.7 billion in wall funding as well as a three-year extension of protections for DACA recipients and some Temporary Protected Status holders, adding, "The president went out of his way to include additional items that have been priority areas for Democrats."[176] The shutdown ended on January 25, when President Trump signed a three-week funding measure reopening the government until February 15.[177]

On February 14, 2019, ahead of the Senate approving legislation preventing another partial government shutdown and provide funding for President Trump's U.S.-Mexico border, McConnell announced that President Trump "has indicated he's prepared to sign the bill" and would "be issuing a national emergency declaration at the same time."[178] McConnell said that he had indicated to Trump that he supported Trump's national emergency declaration.[179]

Guns

On the weekend of January 19–21, 2013, the McConnell for Senate campaign emailed and robo-called gun-rights supporters telling them that "President Obama and his team are doing everything in their power to restrict your constitutional right to keep and bear arms." McConnell also said, "I'm doing everything in my power to protect your 2nd Amendment rights."[180] On April 17, 2013, McConnell voted against expanding background checks for gun purchases.[181]

In January 2016, after President Obama announced new executive actions to combat gun violence, McConnell charged Obama with playing politics and panned the administration's record on prosecuting gun law violations as "abysmal". McConnell stated that examinations of the mass shootings "sort of underscores the argument that if somebody there had had a weapon fewer people would have died" and predicted Obama's proposals would fail to keep "guns out of the hands of criminals".[182] In June, after the Orlando nightclub shooting occurred, then the deadliest mass shooting by a lone gunman in American history, four partisan gun measures came up for vote in the Senate and were all rejected. McConnell opined that Democrats were using the shooting as a political talking point while Republicans John Cornyn and Chuck Grassley were "pursuing real solutions that can help keep Americans safer from the threat of terrorism."[183]

In October 2017, following the Las Vegas shooting, McConnell told reporters that the investigation into the incident "has not even been completed, and I think it's premature to be discussing legislative solutions if there are any." He stated that he believed it "particularly inappropriate to politicize an event like this" and the issue of tax reform should remain the priority while the investigation was ongoing.[184]

Health policy

McConnell led efforts against President Barack Obama's health care reform, ensuring that no Republican senator supported Obama's 2009–2010 health care reform legislation.[185][40] McConnell explained the reasoning behind withholding Republican support as, "It was absolutely critical that everybody be together because if the proponents of the bill were able to say it was bipartisan, it tended to convey to the public that this is O.K., they must have figured it out."[185][26][40] McConnell voted against the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (commonly called ObamaCare or the Affordable Care Act) in December 2009,[186] and he voted against the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010.[187] In 2014, McConnell repeated his call for the full repeal of Obamacare and said that Kentucky should be allowed to keep the state's health insurance exchange website, Kynect, or set up a similar system.[188] McConnell is part of the group of 13 senators drafting the Senate version of the AHCA behind closed doors.[189][190][191][192] The Senator refused over 15 patient advocacy organization's requests to meet with his congressional staff to discuss the legislation. This included groups like the American Heart Association, March of Dimes, American Lung Association. and the American Diabetes Association.[193]

McConnell received the Kentucky Life Science Champion Awards for his work in promoting innovation in the life science sector.[194]

In 2015, both houses of Congress passed a bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act.[195] It was vetoed by President Obama in January 2016.[196]

After President Trump took office in January 2017, Senate Republicans, under McConnell's leadership, began to work on a plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. They faced opposition from both Democrats and moderate Republicans, who claimed that the bill would leave too many people uninsured, and more conservative Republicans, who protested that the bill kept too many of the ACA's regulation and spending increases, and was thus not a full repeal. Numerous attempts at repeal failed. On June 27, after a meeting with President Trump at the White House, McConnell signaled improvements for the repeal and replacement: "We're not quite there. But I think we've got a really good chance of getting there. It'll just take us a little bit longer."[197] During a Rotary Club lunch on July 6, McConnell said, "If my side is unable to agree on an adequate replacement, then some kind of action with regard to the private health insurance market must occur."[198]

In October 2018, after the Trump administration joined Texas leaders and 19 other Republican state attorney generals in a lawsuit seeking to overturn the ACA, McConnell said it was no secret Republicans preferred to reboot their efforts in repealing the ACA and that he did not "fault the administration for trying to give us an opportunity to do this differently and to go in a different direction."[199]

In February 2019, when Senator Sherrod Brown and Representative Lloyd Doggett unveiled legislation to allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices, Brown stated that he hoped for a vote in the House that would "put the pressure" on McConnell.[200]

Immigration

In 2013, a bipartisan group of senators known as the Gang of Eight worked on immigration reform, introducing legislation that would establish a 13-year pathway to citizenship for millions of undocumented immigrants, with several security benchmarks that have to be met before they can obtain a green card, and require a mandatory workplace verification system for employers. McConnell opposed the bill on the grounds of it not including sufficient border-security measures that would future illegal immigration.[201]

In February 2018, McConnell stated his support for an immigration proposal that aligned with President Trump's framework, reasoning the bill which he said had "the best chance" of being signed into law.[202] By this point, he considered the issue to have run its course over three days of floor debate.[203]

In 2015, McConnell rebuked then-candidate Donald Trump's proposal to ban Muslim immigration to the United States.[204] In June 2018, minutes after the Supreme Court upheld the Trump administration's travel ban targeting several Muslim-majority countries in a 5–4 decision along ideological lines, McConnell tweeted a gloating picture of him shaking hands with Neil Gorsuch.[205][206] Gorsuch was nominated to fill a vacant Supreme Court by President Trump after McConnell and Senate Republicans refused to hold hearings on Merrick Garland, President Obama's nomination to the court, for almost a year.[205]

Judicial nominees

According to the New York Times, "From the moment Obama entered the White House, McConnell led Senate Republicans in a disciplined, sustained, at times underhanded campaign to deny the Democratic president the opportunity to appoint federal judges."[207] In June 2009, following President Obama nominating Sonia Sotomayor as Associate Justice, McConnell and Jeff Sessions opined that Sotomayor's seventeen years as a federal judge and over 3,600 judicial opinions would require lengthy review and advocated against Democrats hastening the confirmation process.[208] On July 17, McConnell announced that he would vote against Sotomayor's confirmation, citing her lack of respect for equal justice and furthering that her confirmation would mean there "would be no higher court to deter or prevent her from injecting into the law the various disconcerting principles that recur throughout her public statements."[209] In August, McConnell called Sotomayor "a fine person with an impressive story and a distinguished background" but added that she "does not pass" the most fundamental test of being a judge capable of withholding her personal or political views while serving. Sotomayor was confirmed days later.[210]

In May 2010, after President Obama nominated Elena Kagan to succeed the retiring John Paul Stevens, McConnell stated during a Senate speech that Americans wanted to make sure Kagan would be independent of influence from White House as an Associate Justice and noted Obama referring to Kagan as a friend of his in announcing her nomination. McConnell said it was his hope "that the Obama administration doesn’t think the ideal Supreme Court nominee is someone who would rubber stamp its policies" and that question had been raised and needed answering.[211] In a June interview, McConnell did not rule out the Kagan nomination being filibustered by Republican senators, noting that he had "never filibustered a Supreme Court nominee" and calling it premature to definitively answer if any of his fellow Republican senators would.[212] On July 2, McConnell announced his opposition to Kagan's confirmation, citing her falling short of "meeting her own standard for providing the Senate helpful testimony", being "far from forthcoming in discussing her own views on basic principles of American constitutional law", and being unable to convince him that she "would suddenly constrain the ardent political advocacy that has marked much of her adult life."[213] Kagan was confirmed the following month.[214]

On February 13, 2016, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia died.[215] Later that day, McConnell issued a statement indicating that the U.S. Senate would not consider any Supreme Court nominee put forth by President Barack Obama to fill Justice Scalia's vacated seat.[216] "'The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new president,'" McConnell said.[216] On March 16, 2016, President Obama nominated Merrick Garland, a Judge of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, to the Supreme Court.[217] Under McConnell's leadership, Senate Republicans refused to take any action on the Garland nomination.[218] Garland's nomination expired on January 3, 2017, with the end of the 114th Congress.[219] In January 2017, Republican President Donald Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch to fill the Court vacancy;[220] Gorsuch's nomination was confirmed on April 7, 2017.[221]

In an August 2016 speech in Kentucky, McConnell made reference to the Garland nomination; he said, "One of my proudest moments was when I looked Barack Obama in the eye and I said, 'Mr. President, you will not fill the Supreme Court vacancy.'"[222][223][224] In April 2018, McConnell said the decision not to act upon the Garland nomination was "the most consequential decision I've made in my entire public career".[225] Later that year, McConnell said that if a Supreme Court vacancy would happen during Trump's 2020 re-election year, he would not follow the precedent that he set in 2016 and let the winner of the presidential election nominate a justice.[226]

On July 18, 2018, with Andy Oldham's Senate confirmation, Senate Republicans broke a record for largest number of appeals court judiciary confirmations "during a president's first two years". Oldham became the 23rd judge to be confirmed in said period.[227] Addressing the issue, McConnell stated that considering "the things that we've been able to do with this Republican government the last year and a half", the most "long lasting, positive impact" they would have on the country would be the judiciary. The number of circuit court judges "confirmed during a president's first year" was broken in 2017, while the previous two-year record took place under President George H.W. Bush, and included 22 nominations.[228]

In July 2018, after President Trump nominated Brett Kavanaugh to replace the retiring Anthony Kennedy as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, McConnell accused Democrats of creating an "extreme" distortion of Kavanaugh's record and compared their treatment of Kavanaugh to that of 1987 Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork.[229] In September 2018, Christine Blasey Ford went public with allegations that she had been sexually assaulted by Kavanaugh in 1982. On September 18, during a private meeting, McConnell warned Senate Republicans that there would be political fallout if they failed to confirm Kavanaugh.[230] After a report came out of Democrats investigating a second allegation against Kavanaugh, McConnell stated, "I want to make it perfectly clear. ... Judge Kavanaugh will be voted on here on the Senate floor."[231] Kavanaugh was confirmed on October 6.[232][233] McConnell afterward admitted the confirmation process was a low point for the Senate, but added that there had "been an awful lot of bipartisan cooperation"; McConnell opined that claims that the Senate was "somehow broken over this [were] simply inaccurate."[234]

Net neutrality

In December 2010, after the Republicans gained control of the House in the 2010 midterm elections, McConnell delivered a Senate floor speech rebuking the intention of the Federal Communications Commission to instate net neutrality in its monthly commission meeting, saying the Obama administration was moving forward "with what could be a first step in controlling how Americans use the Internet by establishing federal regulations on its use" after having already nationalized healthcare, the auto industry, companies that could be insured, and loans for students and banks and called for the Internet to be left alone as it was "an invaluable resource." McConnell pledged that the incoming 112th United States Congress would push back against additional regulations.[235]

In November 2014, after President Obama announced a series of proposals including regulations that he stated would keep the Internet open and free, McConnell released a statement saying the FCC would be wise to reject the proposal and charged Obama's plan with endorsing "more heavy-handed regulation that will stifle innovation."[236]

In December 2017, after the FCC voted to repeal net neutrality, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer announced his intent to force a vote on the FCC's decision, a spokesman for McConnell confirming that the Majority Leader opposed Schumer's plan and favored the FCC's decision to repeal.[237]

In February 2018, the Internet Association sent a letter to McConnell and Schumer endorsing the retention of net neutrality as "necessitated by, among other factors, the lack of competition in the broadband service market" and calling "for a bipartisan effort to establish permanent net neutrality rules for consumers, startups, established internet businesses, and internet service providers."[238]

Trade

In January 2018, McConnell was one of thirty-six Republican senators to sign a letter to President Trump requesting he preserve the North American Free Trade Agreement by modernizing it for the economy of the 21st century.[239] In March, McConnell was asked at a news conference about the Trump administration's intent to impose tariffs on imported aluminum and steel, answering that there was "a lot of concern among Republican senators that this could sort of metastasize into a larger trade war" and that there were discussions between senators and the administration on "just how broad, how sweeping this might be, and there is a high level of concern about interfering with what appears to be an economy that is taking off." McConnell defended NAFTA as having been successful in his state of Kentucky.[240] In July, during a press conference, McConnell said, "I'm concerned about getting into a trade war and it seems like ... we may actually be in the early stages of it. Nobody wins a trade war, and so it would be good if it ended soon."[241] In October, after the United States, Canada, and Mexico concluded talks relating to rearranging NAFTA, McConnell said the subject would "be a next-year issue because the process we have to go through doesn't allow that to come up before the end of this year" along with confirming that the U.S. International Trade Commission would take priority the following year.[242]

Electoral history

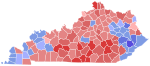

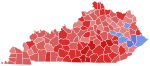

In the graphics below, elections are shown with a map depicting county-by-county information. McConnell is shown in red and Democratic opponents shown in blue.

| Year | % McConnell | Opponent(s) | Party affiliation | % of vote | County-by-county map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 49.9% | Walter Huddleston (incumbent)

Dave Welters |

Democratic

Socialist Workers |

49.5% |

|

| 1990 | 52.2% | Harvey I. Sloane | Democratic | 47.8% |

|

| 1996 | 55.5% | Steve Beshear

Dennis Lacy Patricia Jo Metten Mac Elroy |

Democratic

Libertarian Natural Law U.S. Taxpayers |

42.8% |

|

| 2002 | 64.7% | Lois Combs Weinberg | Democratic | 35.3% |

|

| 2008 | 53.0% | Bruce Lunsford | Democratic | 47.0% |

|

| 2014 | 56.2% | Alison Lundergan Grimes

David Patterson |

Democratic

Libertarian |

40.7% |

|

1984

In 1984, McConnell ran for the U.S. Senate against two-term Democratic incumbent Walter Dee Huddleston. The election race was not decided until the last returns came in, and McConnell won by a thin margin—only 3,437 votes out of more than 1.2 million votes cast, just over 0.4%.[243] McConnell was the only Republican Senate challenger to win that year, despite Ronald Reagan's landslide victory in the presidential election. Part of McConnell's success came from a series of television campaign spots called "Where's Dee", which featured a group of bloodhounds trying to find Huddleston,[244][245] implying that Huddleston's attendance record in the Senate was less than stellar. His campaign bumper stickers and television ads asked voters to "Switch to Mitch".[246][247]

| 1984 U.S. Senate Republican primary election in Kentucky | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | +% |

| Republican | Mitch McConnell | 39,465 | 79.2% | |

| Republican | Roger Harker | 3,798 | 7.6% | |

| Republican | Tommy Klein | 3,352 | 6.7% | |

| Republican | Thurman Jerome Hamlin | 3,202 | 6.4% | |

1990

In 1990, McConnell faced a tough re-election contest against former Louisville Mayor Harvey I. Sloane, winning by 4.4%.[248]

| 1990 U.S. Senate Republican primary election in Kentucky | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | +% |

| Republican | Mitch McConnell (inc.) | 64,063 | 88.5% | |

| Republican | Tommy Klein | 8,310 | 11.5% | |

1996

In 1996, he defeated Steve Beshear by 12.6%,[249] even as Bill Clinton narrowly carried the state. In keeping with a tradition of humorous and effective television ads in his campaigns, McConnell's campaign ran television ads that warned voters to not "Get BeSheared" and included images of sheep being sheared.[247]

| 1996 U.S. Senate Republican primary election in Kentucky | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | +% |

| Republican | Mitch McConnell (inc.) | 88,620 | 88.6% | |

| Republican | Tommy Klein | 11,410 | 11.4% | |

2002

In 2002, he was re-elected against Lois Combs Weinberg by 29.4%, the largest majority by a statewide Republican candidate in Kentucky history.[250]

2008

In 2008, McConnell faced his closest contest since 1990. He defeated Bruce Lunsford by 6%.[12]

| 2008 U.S. Senate Republican primary election in Kentucky | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | +% |

| Republican | Mitch McConnell (inc.) | 168,127 | 86.1% | |

| Republican | Daniel Essek | 27,170 | 13.9% | |

2014

In 2014, McConnell faced Louisville businessman Matt Bevin in the Republican primary.[251] The 60.2% won by McConnell was the lowest voter support for a Kentucky U.S. Senator in a primary since 1938.[252] He faced Democratic Secretary of State Alison Lundergan Grimes in the general election. Although polls showed the race was very close,[253] McConnell defeated Grimes, 56.2–40.7%.[254][255] The 15.5% margin of victory was one of his largest, second only to his 2002 margin.

| 2014 U.S. Senate Republican primary election in Kentucky | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | +% |

| Republican | Mitch McConnell (inc.) | 213,753 | 60.2% | |

| Republican | Matt Bevin | 125,787 | 35.4% | |

| Republican | Shawna Sterling | 7,214 | 2.0% | |

| Republican | Chris Payne | 5,338 | 1.5% | |

| Republican | Brad Copas | 3,024 | 0.9% | |

Personal life

McConnell is a Southern Baptist.[256] He was married to his first wife, Sherrill Redmon, from 1968 to 1980, and had three children.[257] Following their divorce, she became a feminist scholar at Smith College and director of the Sophia Smith Collection.[258][259] His second wife, whom he married in 1993, is Elaine Chao, the former Secretary of Labor under George W. Bush.[260] On November 29, 2016, incoming President Donald Trump nominated Chao to serve as the Secretary of Transportation. She was confirmed by the Senate on January 31, 2017, in a 93–6 vote.[260] McConnell himself voted "present" during the confirmation roll call.[261]

McConnell is on the Board of Selectors of Jefferson Awards for Public Service.[262]

In 1997, he founded the James Madison Center for Free Speech, a Washington, D.C.–based legal defense organization.[263][264] McConnell was inducted as a member of the Sons of the American Revolution on March 1, 2013.[265]

In February 2003, McConnell underwent a triple heart bypass surgery in relation to blocked arteries at National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland.[266]

In 2010, the OpenSecrets website ranked McConnell one of the wealthiest members of the U.S. Senate, based on net household worth.[267] His personal wealth was increased after receiving a 2008 personal gift to him and his wife, given by his father-in-law James S. C. Chao after the death of McConnell's mother-in-law, that ranged between $5 and $25 million.[268][269]

In popular culture

McConnell appears in the title sequence, and as an off-screen character, in season 1 of Alpha House.[270]

Host Jon Stewart repeatedly mocked McConnell on The Daily Show for his resemblance to a turtle or tortoise and often imitated him with the voice of the Cecil Turtle from Tortoise Wins by a Hare.[271]

References

- ^ Kessler, Glenn (May 22, 2014). "How did Mitch McConnell's Net Worth Soar?". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c McConnell, Mitch (2016). "Chapter One: A fighting spirit". The long game: a memoir. New York, NY: Sentinel. ISBN 9780399564123. ("She'd been known her whole life not by her first name, Julia, which she loved, but by her middle name, Odene, which she detested. So in Birmingham she began to call herself Dean, and with no thought of ever returning to Wadley... James McConnell, from County Down, Ireland, who came to this country as a young boy in the 1760s, went on to fight for the colonies in the American Revolution.").

- ^ "Fact of the Week". The Tuscaloosa News. July 16, 2000. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ Middleton, Karen (December 28, 2014). "Athens native Sen. Mitch McConnell looking forward to busy opening session" (PDF). The News Courier. Archived from the original on January 4, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) ("McConnell said that his original American ancestor emigrated from County Down, Ireland, to North Carolina."). - ^ Phillips, Kristine (June 27, 2017). "No, the government did not pay for Mitch McConnell's polio care. Charity did". Washington Post. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ^ "Mitch McConnell on Trump and divisiveness in politics". CBS News. May 29, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ Hicks, Jesse (June 26, 2017). "In 1990, Mitch McConnell Supported Affordable Healthcare for All". vice.com. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ^ a b c McConnell, Mitch (2016). "Chapter Two: From baseball to politics." The long game: a memoir.

- ^ a b "Biography – About – U.S. Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell". Mitch McConnell; Republican Leader. U.S. Senator for Kentucky. mcconnell.senate.gov. January 3, 1985. Archived from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e McConnell, Mitch (2016). "Chapter Three: Seeing greatness." The long game: a memoir.