Prognosis of COVID-19

This article documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (June 2020) |

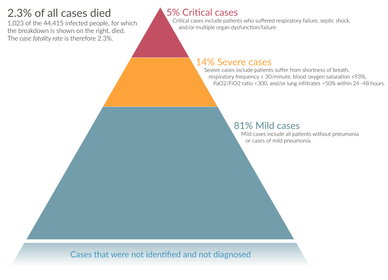

The severity of COVID‑19 varies. The disease may take a mild course with few or no symptoms, resembling other common upper respiratory diseases such as the common cold. Mild cases typically recover within two weeks, while those with severe or critical diseases may take three to six weeks to recover. Among those who have died, the time from symptom onset to death has ranged from two to eight weeks.[7]

Children make up a small proportion of reported cases, with about 1% of cases being under 10 years and 4% aged 10–19 years.[8] They are likely to have milder symptoms and a lower chance of severe disease than adults; in those younger than 50 years the risk of death is less than 0.5%, while in those older than 70 it is more than 8%.[9][10][11] Pregnant women may be at higher risk for severe infection with COVID‑19 based on data from other similar viruses, like Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), but data for COVID‑19 is lacking.[12][13] In China, children acquired infections mainly through close contact with their parents or other family members who lived in Wuhan or had traveled there.[9]

Some studies have found that the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) may be helpful in early screening for severe illness.[14]

Most of those who die of COVID‑19 have pre-existing (underlying) conditions, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease.[15] The Istituto Superiore di Sanità reported that out of 8.8% of deaths where medical charts were available, 97% of people had at least one comorbidity with the average person having 2.7 diseases.[16] According to the same report, the median time between the onset of symptoms and death was ten days, with five being spent hospitalised. However, people transferred to an ICU had a median time of seven days between hospitalisation and death.[16] In a study of early cases, the median time from exhibiting initial symptoms to death was 14 days, with a full range of six to 41 days.[17] In a study by the National Health Commission (NHC) of China, men had a death rate of 2.8% while women had a death rate of 1.7%.[18] Histopathological examinations of post-mortem lung samples show diffuse alveolar damage with cellular fibromyxoid exudates in both lungs. Viral cytopathic changes were observed in the pneumocytes. The lung picture resembled acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[7] In 11.8% of the deaths reported by the National Health Commission of China, heart damage was noted by elevated levels of troponin or cardiac arrest.[19] According to March data from the United States, 89% of those hospitalised had preexisting conditions.[20]

The availability of medical resources and the socioeconomics of a region may also affect mortality.[21] Estimates of the mortality from the condition vary because of those regional differences,[22] but also because of methodological difficulties. The under-counting of mild cases can cause the mortality rate to be overestimated.[23] However, the fact that deaths are the result of cases contracted in the past can mean the current mortality rate is underestimated.[24][25] Smokers were 1.4 times more likely to have severe symptoms of COVID‑19 and approximately 2.4 times more likely to require intensive care or die compared to non-smokers.[26][27] According to a number of studies, air pollution is similarly associated with risk factors.[27] According to three scientific reviews, obesity contributes to an increased risk and poorer prognosis of COVID-19.[27][28][29]

Concerns have been raised about long-term sequelae of the disease. The Hong Kong Hospital Authority found a drop of 20% to 30% in lung capacity in some people who recovered from the disease, and lung scans suggested organ damage.[30] This may also lead to post-intensive care syndrome following recovery.[31]

Template:COVID-19 CFR by age and country

| Percent of infected people who are hospitalized | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | Total | |

| Female | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) |

0.6 (0.3–0.9) |

1.1 (0.7–1.8) |

1.6 (0.9–2.4) |

3.2 (1.9–4.9) |

6.2 (3.7–9.6) |

9.6 (5.7–14.8) |

23.6 (14.0–36.4) |

3.2 (1.9–5.0) |

| Male | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) |

0.7 (0.4–1.1) |

1.4 (0.9–2.2) |

1.9 (1.1–3.0) |

3.9 (2.3–6.1) |

8.1 (4.8–12.6) |

13.4 (8.0–20.7) |

45.9 (27.3–70.9) |

4.0 (2.4–6.2) |

| Total | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) |

0.6 (0.4–1.0) |

1.3 (0.8–2.0) |

1.7 (1.0–2.7) |

3.5 (2.1–5.4) |

7.1 (4.2–11.0) |

11.3 (6.7–17.5) |

32.0 (19.0–49.4) |

3.6 (2.1–5.6) |

| Percent of hospitalized people who go to Intensive Care Unit | |||||||||

| 0–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | Total | |

| Female | 16.7 (14.4–19.2) |

8.6 (7.5–9.9) |

11.9 (10.9–13.0) |

16.6 (15.6–17.7) |

20.7 (19.8–21.7) |

23.1 (22.2–24.0) |

18.7 (18.0–19.5) |

4.2 (4.0–4.5) |

14.3 (13.9–14.7) |

| Male | 26.9 (23.2–31.0) |

14.0 (12.2–15.9) |

19.2 (17.6–20.9) |

26.9 (25.3–28.5) |

33.4 (32.0–34.8) |

37.3 (36.0–38.6) |

30.2 (29.2–31.3) |

6.8 (6.5–7.2) |

23.1 (22.6–23.6) |

| Total | 22.2 (19.2–25.5) |

11.5 (10.1–13.2) |

15.9 (14.6–17.3) |

22.2 (21.0–23.5) |

27.6 (26.5–28.7) |

30.8 (29.8–31.8) |

24.9 (24.1–25.8) |

5.6 (5.3–5.9) |

19.0 (18.7–19.44) |

| Percent of hospitalized people who die | |||||||||

| 0–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | Total | |

| Female | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) |

0.9 (0.5–1.3) |

1.5 (1.2–1.9) |

2.6 (2.3–3.0) |

5.2 (4.8–5.6) |

10.1 (9.5–10.6) |

16.7 (16.0–17.4) |

25.2 (24.4–26.0) |

14.4 (14.0–14.9) |

| Male | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) |

1.3 (0.8–1.9) |

2.2 (1.7–2.7) |

3.8 (3.4–4.4) |

7.6 (7.0–8.2) |

14.8 (14.1–15.6) |

24.6 (23.7–25.6) |

37.1 (36.1–38.2) |

21.22 (20.8–21.7) |

| Total | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) |

1.1 (0.7–1.6) |

1.9 (1.5–2.3) |

3.3 (2.9–3.7) |

6.5 (6.0–7.0) |

12.6 (12.0–13.2) |

21.0 (20.3–21.8) |

31.6 (30.9–32.4) |

18.1 (17.8–18.4) |

| Percent of infected people who die – infection fatality rate (IFR) | |||||||||

| 0–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | Total | |

| Female | 0.001 (<0.001–0.002) |

0.005 (0.002–0.009) |

0.02 (0.01–0.03) |

0.04 (0.02–0.07) |

0.2 (0.1–0.3) |

0.6 (0.4–1.0) |

1.6 (1.0–2.5) |

5.9 (3.5–9.2) |

0.5 (0.3–0.7) |

| Male | 0.001 (<0.001–0.003) |

0.008 (0.004–0.02) |

0.03 (0.02–0.05) |

0.07 (0.04–0.1) |

0.3 (0.2–0.5) |

1.2 (0.7–1.9) |

3.3 (2.0–5.1) |

17.1 (10.1–26.3) |

0.8 (0.5–1.3) |

| Total | 0.001 (<0.001–0.002) |

0.007 (0.003–0.01) |

0.02 (0.01–0.04) |

0.06 (0.03–0.09) |

0.2 (0.1–0.36) |

0.9 (0.5–1.4) |

2.4 (1.4–3.7) |

10.1 (6.0–15.6) |

0.7 (0.4–1.0) |

| Numbers in parentheses are 95% credible intervals for the estimates. | |||||||||

Existing respiratory problems

- Most critical respiratory comorbidities according to the CDC, are: moderate or severe Asthma, pre-existing COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, cystic fibrosis.[33] Current evidence stemming from meta - analysis of several smaller research papers, also suggest that smoking can be assosiated with worse patient outcomes [34][35]

- When someone with existing respiratory problems is infected with COVID-19, they might be at greater risk for severe symptoms.[36] COVID-19 also poses a greater risk to people who misuse opioids and methamphetamines, insofar as their drug use may have caused lung damage.[37]

Immunity

It is unknown (as of April 2020) if past infection provides effective and long-term immunity in people who recover from the disease.[38][39] Some of the infected have been reported to develop protective antibodies, so acquired immunity is presumed likely, based on the behaviour of other coronaviruses.[40] Cases in which recovery from COVID‑19 was followed by positive tests for coronavirus at a later date have been reported.[41][42][43][44] However, these cases are believed to be lingering infection rather than reinfection,[44] or false positives due to remaining RNA fragments.[45] An investigation by the Korean CDC of 285 individuals who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in PCR tests administered days or weeks after recovery from COVID-19 found no evidence that these individuals were contagious at this later time.[46] Some other coronaviruses circulating in people are capable of reinfection after roughly a year.[47][48]

References

- ^ Roser, Max; Ritchie, Hannah; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban (4 March 2020). "Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Epidemiology2020Feb17was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ 39 additional cases have been confirmed (Report). Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-06-05. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Actualización nº 109. Enfermedad por el coronavirus (COVID-19) (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. 18 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Epidemia COVID-19 – Bollettino sorveglianza integrata COVID-19" (PDF) (in Italian). Istituto Superiore di Sanità. 2020-06-05. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ^ Roser, Max; Ritchie, Hannah; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban (6 April 2020). "Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). 16–24 February 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Q & A on COVID-19". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ a b Castagnoli R, Votto M, Licari A, Brambilla I, Bruno R, Perlini S, et al. (April 2020). "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review". JAMA Pediatrics. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467. PMID 32320004.

- ^ Lu X, Zhang L, Du H, Zhang J, Li YY, Qu J, et al. (April 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (17). Massachusetts Medical Society: 1663–1665. doi:10.1056/nejmc2005073. PMC 7121177. PMID 32187458.

- ^ Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, Qi X, Jiang F, Jiang Z, Tong S (March 2020). "Epidemiology of COVID-19 Among Children in China" (PDF). Pediatrics: e20200702. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-0702. PMID 32179660. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M (April 2020). "Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection?". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 8 (4): e21. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30311-1. PMC 7118626. PMID 32171062.

- ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Yang S, Tao Y, et al. (March 2020). "Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China". Clinical Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa248. PMC 7108125. PMID 32161940.

- ^ "WHO Director-General's statement on the advice of the IHR Emergency Committee on Novel Coronavirus". World Health Organization (WHO).

- ^ a b Palmieri L, Andrianou X, Barbariol P, Bella A, Bellino S, Benelli E, et al. (3 April 2020). Characteristics of COVID-19 patients dying in Italy Report based on available data on April 2th, 2020 (PDF) (Report). Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Wang W, Tang J, Wei F (April 2020). "Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China". Journal of Medical Virology. 92 (4): 441–447. doi:10.1002/jmv.25689. PMC 7167192. PMID 31994742.

- ^ "Coronavirus Age, Sex, Demographics (COVID-19)". www.worldometers.info. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X (May 2020). "COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system". Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 17 (5): 259–260. doi:10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. PMC 7095524. PMID 32139904.

- ^ Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, O'Halloran A, Cummings C, Holstein R, et al. (April 2020). "Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Laboratory-Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 - COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1-30, 2020". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (15): 458–464. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. PMID 32298251.

- ^ Ji Y, Ma Z, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q (April 2020). "Potential association between COVID-19 mortality and health-care resource availability". The Lancet. Global Health. 8 (4): e480. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30068-1. PMC 7128131. PMID 32109372.

- ^ Li XQ, Cai WF, Huang LF, Chen C, Liu YF, Zhang ZB, et al. (March 2020). "[Comparison of epidemic characteristics between SARS in2003 and COVID-19 in 2020 in Guangzhou]". Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi = Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi (in Chinese). 41 (5): 634–637. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200228-00209. PMID 32159317.

- ^ Jung SM, Akhmetzhanov AR, Hayashi K, Linton NM, Yang Y, Yuan B, et al. (February 2020). "Real-Time Estimation of the Risk of Death from Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection: Inference Using Exported Cases". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9 (2): 523. doi:10.3390/jcm9020523. PMC 7074479. PMID 32075152.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Chughtai AA, Malik AA (March 2020). "Is Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) case fatality ratio underestimated?". Global Biosecurity. 1 (3). doi:10.31646/gbio.56 (inactive 2020-06-01).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of June 2020 (link) - ^ Baud D, Qi X, Nielsen-Saines K, Musso D, Pomar L, Favre G (March 2020). "Real estimates of mortality following COVID-19 infection". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30195-X. PMC 7118515. PMID 32171390.

- ^ Vardavas CI, Nikitara K (20 March 2020). "COVID-19 and smoking: A systematic review of the evidence". Tobacco Induced Diseases. 18 (March): 20. doi:10.18332/tid/119324. PMC 7083240. PMID 32206052.

- ^ a b c Engin, Ayse Basak; Engin, Evren Doruk; Engin, Atilla (1 August 2020). "Two important controversial risk factors in SARS-CoV-2 infection: Obesity and smoking". Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 78: 103411. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2020.103411. ISSN 1382-6689. PMC 7227557. PMID 32422280. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Tamara, Alice; Tahapary, Dicky L. (1 July 2020). "Obesity as a predictor for a poor prognosis of COVID-19: A systematic review". Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 14 (4): 655–659. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.020. ISSN 1871-4021. PMID 32438328. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ "Obesity ‑ a risk factor for increased COVID‑19 prevalence, severity and lethality (Review)". Molecular Medicine Reports. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Cheung, Elizabeth (13 March 2020). "Some recovered Covid-19 patients may have lung damage, doctors say". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Servick, Kelly (8 April 2020). "For survivors of severe COVID-19, beating the virus is just the beginning". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abc1486. ISSN 0036-8075.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Salje, Henrik; Tran Kiem, Cécile; Lefrancq, Noémie; Courtejoie, Noémie; Bosetti, Paolo; Paireau, Juliette; Andronico, Alessio; Hozé, Nathanaël; Richet, Jehanne; Dubost, Claire-Lise; Le Strat, Yann (13 May 2020). "Estimating the burden of SARS-CoV-2 in France". Science. Table S1 and S2 in Supplementary Materials. doi:10.1126/science.abc3517. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 7223792. PMID 32404476.

- ^ CDC (2020-02-11). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- ^ Zhao, Qianwen; Meng, Meng; Kumar, Rahul; Wu, Yinlian; Huang, Jiaofeng; Lian, Ningfang; Deng, Yunlei; Lin, Su (2020-05-17). "The impact of COPD and smoking history on the severity of COVID‐19: A systemic review and meta‐analysis". Journal of Medical Virology. doi:10.1002/jmv.25889. ISSN 0146-6615.

- ^ "Smoking and COVID-19". www.who.int. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ DeRobertis, Jacqueline (3 May 2020). "People who use drugs are more vulnerable to coronavirus. Here's what clinics are doing to help". The Advocate (Louisiana). Retrieved 4 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "BSI open letter to Government on SARS-CoV-2 outbreak response". immunology.org. British Society for Immunology. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Schraer, Rachel (25 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Immunity passports 'could increase virus spread'". Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "Can you get coronavirus twice or does it cause immunity?". The Independent. 13 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Politi, Daniel (11 April 2020). "WHO Investigating Reports of Coronavirus Patients Testing Positive Again After Recovery". Slate. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "They survived the coronavirus. Then they tested positive again. Why?". Los Angeles Times. 13 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "14% of Recovered Covid-19 Patients in Guangdong Tested Positive Again". caixinglobal.com. Caixin Global. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ a b Omer SB, Malani P, Del Rio C (April 2020). "The COVID-19 Pandemic in the US: A Clinical Update". JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.5788. PMID 32250388.

- ^ Parry, Richard Lloyd (30 April 2020), "Coronavirus patients can't relapse, South Korean scientists believe", The Times

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Findings from investigation and analysis of re-positive cases". KCDC. 19 May 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "What if immunity to covid-19 doesn't last?". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Direct observation of repeated infections with endemic coronaviruses" (PDF). Columbia University in the City of New York. Department of Environmental Health Sciences, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University. 15 April 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.