Cornwall

Cornwall | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): Onen hag oll (Cornish) One and all | |

| |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | South West England |

| Origin | Historic |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Area | [convert: needs a number] |

| • Rank | of 48 |

| • Rank | of 48 |

| Density | [convert: needs a number] |

| Ethnicity | 95.7% White British, 4.3% Other |

Cornwall (British English pronunciation: /ˈkɔːnwɔːl/ or /ˈkɔːnwəl/[1][2][3] Template:Lang-kw Template:IPA-kw) is a ceremonial county and unitary authority area of England, within the United Kingdom. Cornwall is a peninsula bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea,[4] to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of 577,694 and covers an area of 3,563 km2 (1,376 sq mi).[5][6] The administrative centre, and only city in Cornwall, is Truro, although the town of St Austell has the largest population.

Cornwall forms the westernmost part of the south-west peninsula of the island of Great Britain, and a large part of the Cornubian batholith is within Cornwall. This area was first inhabited in the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods. It continued to be occupied by Neolithic and then Bronze Age peoples, and later (in the Iron Age) by Brythons with distinctive cultural relations to neighbouring Wales and Brittany. There is little evidence that Roman rule was effective west of Exeter and few Roman remains have been found. Cornwall was the home of a division of the Dumnonii tribe – whose tribal centre was in the modern county of Devon – known as the Cornovii, separated from the Brythons of Wales after the Battle of Deorham, often coming into conflict with the expanding English kingdom of Wessex before King Athelstan in AD 936 set the boundary between English and Cornish at the high water mark of the eastern bank of the River Tamar.[7] From the early Middle Ages, British language and culture was apparently shared by Brythons trading across both sides of the Channel, evidenced by the corresponding high medieval Breton kingdoms of Domnonée and Cornouaille and the Celtic Christianity common to both territories.

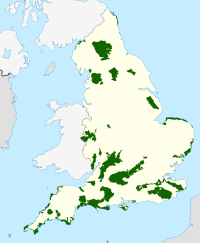

Historically tin mining was important in the Cornish economy, becoming increasingly significant during the High Middle Ages and expanding greatly during the 19th century when rich copper mines were also in production. In the mid-19th century, however, the tin and copper mines entered a period of decline. Subsequently china clay extraction became more important and metal mining had virtually ended by the 1990s. Traditionally fishing (particularly of pilchards), and agriculture (particularly of dairy products and vegetables), were the other important sectors of the economy. The railways led to the growth of tourism during the 20th century, however, Cornwall's economy struggled after the decline of the mining and fishing industries. The area is noted for its wild moorland landscapes, its long and varied coastline, its attractive villages, its many place-names derived from the Cornish language, and its very mild climate. Extensive stretches of Cornwall's coastline, and Bodmin Moor, are protected as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Cornwall is the traditional homeland of the Cornish people and is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, retaining a distinct cultural identity that reflects its history. Some people question the present constitutional status of Cornwall, and a nationalist movement seeks greater autonomy within the United Kingdom in the form of a devolved legislative assembly.[8] On 24 April 2014 it was announced that Cornish people will be granted minority status under the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.[9]

Toponymy

The name Cornwall derives from the combination of two separate terms from different languages. The Corn- part comes from the hypothesised original tribal name of the Celtic people who had lived here since the Iron Age, the Cornovii. The second element -wall derives from the Old English w(e)alh, meaning a "foreigner" or "Welshman". The name first appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in 891 as On Corn walum. In the Domesday Book it was referred to as Cornualia and in c. 1198 as Cornwal.[10]

A latinisation of the name as Cornubia first appears in a mid-9th-century deed purporting to be a copy of one dating from c. 705. Another variation, with Wales reinterpreted as Gallia, thus: Cornugallia, is first attested in 1086. Finally, the Cornish language form of the name, Kernow, which first appears around 1400, derives directly from the original Cornowii.[10] which is postulated from a single mention in the Ravenna Cosmography of around 700 (but based on earlier sources) of Purocoronavis. This is considered to be a corruption of Durocornovium, 'a fort or walled settlement of the Cornovii'.[11] Its location is unidentified, but Tintagel or Carn Brea have been suggested.[12]

In pre-Roman times, Cornwall was part of the kingdom of Dumnonia, and was later known to the Anglo-Saxons as "West Wales", to distinguish it from "North Wales" (modern-day Wales).[13]

History

Prehistory, Roman and post-Roman periods

The present human history of Cornwall begins with the reoccupation of Britain after the last Ice Age. The area now known as Cornwall was first inhabited in the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods. It continued to be occupied by Neolithic and then Bronze Age peoples. According to John T. Koch and others, Cornwall in the Late Bronze Age was part of a maritime trading-networked culture called the Atlantic Bronze Age, in modern-day Ireland, England, France, Spain and Portugal.[14][15] During the British Iron Age Cornwall, like all of Britain south of the Firth of Forth, was inhabited by a Celtic people known as the Britons with distinctive cultural relations to neighbouring Wales and Brittany. The Common Brittonic spoken at the time eventually developed into several distinct tongues, including Cornish.[16]

The first account of Cornwall comes from the Sicilian Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (c. 90 BCE – c. 30 BCE), supposedly quoting or paraphrasing the 4th-century BCE geographer Pytheas, who had sailed to Britain:

The inhabitants of that part of Britain called Belerion (or Land's End) from their intercourse with foreign merchants, are civilised in their manner of life. They prepare the tin, working very carefully the earth in which it is produced ... Here then the merchants buy the tin from the natives and carry it over to Gaul, and after travelling overland for about thirty days, they finally bring their loads on horses to the mouth of the Rhône.

— Halliday (1959), p. 51.

The identity of these merchants is unknown. It has been theorised that they were Phoenicians, but there is no evidence for this.[17] (For further discussion of tin mining see the section on the economy below.)

There is little evidence that Roman rule was effective west of Exeter in Devon and few Roman remains have been found. However after 410, Cornwall appears to have reverted to rule by Romano-Celtic chieftains of the Cornovii tribe as part of Dumnonia including one Marcus Cunomorus with at least one significant power base at Tintagel. 'King' Mark of Cornwall is a semi-historical figure known from Welsh literature, the Matter of Britain, and in particular, the later Norman-Breton medieval romance of Tristan and Yseult where he is regarded as a close kinsman of King Arthur; himself usually considered to be born of the Cornish people in folklore traditions derived from Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae. Archaeology supports ecclesiastical, literary and legendary evidence for some relative economic stability and close cultural ties between the sub-Roman Westcountry, South Wales, Brittany and Ireland through the fifth and sixth centuries.[18]

Conflict with Wessex

The Battle of Deorham in 577 saw the separation of Dumnonia (and therefore Cornwall) from Wales, following which the Dumnonii often came into conflict with the expanding English kingdom of Wessex. The Annales Cambriae report that in 722 AD the Britons of Cornwall won a battle at "Hehil".[19] It seems likely that the enemy the Cornish fought was a West Saxon force, as evidenced by the naming of King Ine of Wessex and his kinsman Nonna in reference to an earlier Battle of Lining in 710.[20]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle stated in 815 (adjusted date) "and in this year king Ecgbryht raided in Cornwall from east to west." and thenceforth apparently held it as a ducatus or dukedom annexed to his regnum or kingdom of Wessex, but not wholly incorporated with it.[21] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that in 825 (adjusted date) a battle took place between the Wealas (Cornish) and the Defnas (men of Devon) at Gafulforda. In the same year Ecgbert, as a later document expresses it, "disposed of their territory as it seemed fit to him, giving a tenth part of it to God." In other words he incorporated Cornwall ecclesiastically with the West Saxon diocese of Sherborne, and endowed Ealhstan, his fighting bishop, who took part in the campaign, with an extensive Cornish estate consisting of Callington and Lawhitton, both in the Tamar valley, and Pawton near Padstow.

In 838, the Cornish and their Danish allies were defeated by Egbert in the Battle of Hingston Down at Hengestesdune (probably Hingston Down in Cornwall). In 875, the last recorded king of Cornwall, Dumgarth, is said to have drowned.[22] Around the 880s, Anglo-Saxons from Wessex had established modest land holdings in the eastern part of Cornwall; notably Alfred the Great who had acquired a few estates.[23] William of Malmesbury, writing around 1120, says that King Athelstan of England (924–939) fixed the boundary between English and Cornish people at the east bank of the River Tamar.[7]

Norman-Breton period

One interpretation of the Domesday Book is that by this time the native Cornish landowning class had been almost completely dispossessed and replaced by English landowners, particularly Harold Godwinson himself.[clarification needed] However, the Bodmin manumissions show that two leading Cornish figures nominally had Saxon names, but these were both glossed with native Cornish names.[citation needed] Naming evidence cited by medievalist Edith Ditmas suggests that many post-Conquest landowners in Cornwall were Breton allies of the Normans[24] and further proposed this period for the early composition of the Tristan and Iseult cycle by poets such as Beroul from a pre-existing shared Brittonic oral tradition.[25]

Soon after the Norman conquest most of the land was transferred to the new Breton-Norman aristocracy, with the lion's share going to Robert, Count of Mortain, half-brother of King William and the largest landholder in England after the king with his stronghold at Trematon Castle near the mouth of the Tamar.[26] Cornwall and Devon west of Dartmoor showed a very different type of settlement pattern from that of Saxon Wessex and places continued, even after 1066, to be named in the Celtic Cornish tradition with Saxon architecture being uncommon.[citation needed]

Later medieval administration and society

Subsequently, however, Norman absentee landlords became replaced by a new Cornu-Norman elite including scholars such as Richard Rufus of Cornwall. These families eventually became the new ruling class of Cornwall (typically speaking Norman French, Cornish, Latin and eventually English), many becoming involved in the operation of the Stannary Parliament system, Earldom and eventually the Duchy.[27] The Cornish language continued to be spoken and it acquired a number of characteristics establishing its identity as a separate language from Breton.

Christianity in Cornwall

Many place names in Cornwall are associated with Christian missionaries described as coming from Ireland and Wales in the 5th century AD and usually called saints (See List of Cornish saints). The historicity of some of these missionaries is problematic.[28][29] The patron saint of Wendron Parish Church, "Saint Wendrona" is another example. and it has been pointed out by Canon Doble that it was customary in the Middle Ages to ascribe such geographical origins to saints.[30] Some of these saints are not included in the early lists of saints.[31]

Saint Piran, after whom Perranporth is named, is generally regarded as the patron saint of Cornwall.[32] However in early Norman times it is likely that Saint Michael the Archangel was recognised as the patron saint[33] and is still recognised by the Anglican Church as the Protector of Cornwall.[34] The title has also been claimed for Saint Petroc who was patron of the Cornish diocese prior to the Normans.[35]

Celtic and Anglo-Saxon times

The church in Cornwall until the time of Athelstan of Wessex observed more or less orthodox practices, being completely separate from the Anglo-Saxon church until then (and perhaps later). The See of Cornwall continued until much later: Bishop Conan apparently in place previously, but (re-?) consecrated in 931 AD by Athelstan. However, it is unclear whether he was the sole Bishop for Cornwall or the leading Bishop in the area. The situation in Cornwall may have been somewhat similar to Wales where each major religious house corresponded to a cantref (this has the same meaning as Cornish keverang) both being under the supervision of a Bishop.[36] However if this was so the status of keverangow before the time of King Athelstan is not recorded. However it can be inferred from the districts included at this period that the minimum number would be three: Triggshire; Wivelshire; and the remaining area. Penwith, Kerrier, Pydar and Powder meet at a central point (Scorrier) which some have believed indicates a fourfold division imposed by Athelstan on a sub-kingdom.

Middle Ages

The whole of Cornwall was in this period in the Archdeaconry of Cornwall within the Diocese of Exeter. From 1267 the archdeacons had a house at Glasney near Penryn. Their duties were to visit and inspect each parish annually and to execute the bishop's orders.[37] Archdeacon Roland is recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 as having land holdings in Cornwall but he was not Archdeacon of Cornwall, just an archdeacon in the Diocese of Exeter.[38] In the episcopate of William Warelwast (1107–37) the first Archdeacon of Cornwall was appointed[37] )possibly Hugo de Auco). Most of the parish churches in Cornwall in Norman times were not in the larger settlements, and the medieval towns which developed thereafter usually had only a chapel of ease with the right of burial remaining at the ancient parish church.[39] Over a hundred holy wells exist in Cornwall, each associated with a particular saint, though not always the same one as the dedication of the church.[40][41]

Various kinds of religious houses existed in mediaeval Cornwall though none of them were nunneries; the benefices of the parishes were in many cases appropriated to religious houses within Cornwall or elsewhere in England or France.[42]

From the Reformation to the Victorian period

In the 16th century there was some violent resistance to the replacement of Catholicism with Protestantism in the Prayer Book Rebellion.[43] In 1548 the college at Glasney, a centre of learning and study established by the Bishop of Exeter, had been closed and looted (many manuscripts and documents were destroyed) which aroused resentment among the Cornish. They, among other things, objected to the English language Book of Common Prayer, protesting that the English language was still unknown to many at the time. The Prayer Book Rebellion was a cultural and social disaster for Cornwall; the reprisals taken by the forces of the Crown have been estimated to account for 10–11% of the civilian population of Cornwall. Culturally speaking, it saw the beginning of the slow decline of the Cornish language.

From that time Christianity in Cornwall was in the main within the Church of England and subject to the national events which affected it in the next century and a half. Roman Catholicism never became extinct, though openly practised by very few; there were some converts to Puritanism, Anabaptism and Quakerism in certain areas though they suffered intermittent persecution which more or less came to an end in the reign of William and Mary. During the 18th century Cornish Anglicanism was very much in the same state as Anglicanism in most of England. Wesleyan Methodist missions began during John Wesley's lifetime and had great success over a long period during which Methodism itself divided into a number of sects and established a definite separation from the Church of England.

From the early 19th to the mid-20th century Methodism was the leading form of Christianity in Cornwall but it is now in decline.[44][45] The Church of England was in the majority from the reign of Queen Elizabeth until the Methodist revival of the 19th century: before the Wesleyan missions dissenters were very few in Cornwall. The county remained within the Diocese of Exeter until 1876 when the Anglican Diocese of Truro was created[46][47] (the first Bishop was appointed in 1877). Roman Catholicism was virtually extinct in Cornwall after the 17th century except for a few families such as the Arundells of Lanherne. From the mid-19th century the church reestablished episcopal sees in England, one of these being at Plymouth.[48] Since then immigration to Cornwall has brought more Roman Catholics into the population.

Physical geography

Cornwall forms the tip of the south-west peninsula of the island of Great Britain, and is therefore exposed to the full force of the prevailing winds that blow in from the Atlantic Ocean. The coastline is composed mainly of resistant rocks that give rise in many places to impressive cliffs. Cornwall has a border with only one other county, Devon.

Coastal areas

The north and south coasts have different characteristics. The north coast on the Celtic Sea, part of the Atlantic Ocean, is more exposed and therefore has a wilder nature. The prosaically named High Cliff, between Boscastle and St Gennys, is the highest sheer-drop cliff in Cornwall at 223 metres (732 ft).[49] However, there are also many extensive stretches of fine golden sand which form the beaches that are so important to the tourist industry, such as those at Bude, Polzeath, Watergate Bay, Perranporth, Porthtowan, Fistral Beach, Newquay, St Agnes, St Ives, and on the south coast Gyllyngvase beach in Falmouth. There are two river estuaries on the north coast: Hayle Estuary and the estuary of the River Camel, which provides Padstow and Rock with a safe harbour.

The south coast, dubbed the "Cornish Riviera", is more sheltered and there are several broad estuaries offering safe anchorages, such as at Falmouth and Fowey. Beaches on the south coast usually consist of coarser sand and shingle, interspersed with rocky sections of wave-cut platform. Also on the south coast, the picturesque fishing village of Polperro, at the mouth of the Pol River, and the fishing port of Looe on the River Looe are both popular with tourists.

Inland areas

The interior of the county consists of a roughly east-west spine of infertile and exposed upland, with a series of granite intrusions, such as Bodmin Moor, which contains the highest land within Cornwall. From east to west, and with approximately descending altitude, these are Bodmin Moor, the area north of St Austell, the area south of Camborne, and the Penwith or Land's End peninsula. These intrusions are the central part of the granite outcrops that form the exposed parts of the Cornubian batholith of south-west Britain, which also includes Dartmoor to the east in Devon and the Isles of Scilly to the west, the latter now being partially submerged.

The intrusion of the granite into the surrounding sedimentary rocks gave rise to extensive metamorphism and mineralisation, and this led to Cornwall being one of the most important mining areas in Europe until the early 20th century. It is thought tin was mined here as early as the Bronze Age, and copper, lead, zinc and silver have all been mined in Cornwall. Alteration of the granite also gave rise to extensive deposits of China Clay, especially in the area to the north of St Austell, and the extraction of this remains an important industry.

The uplands are surrounded by more fertile, mainly pastoral farmland. Near the south coast, deep wooded valleys provide sheltered conditions for flora that like shade and a moist, mild climate. These areas lie mainly on Devonian sandstone and slate. The north east of Cornwall lies on Carboniferous rocks known as the Culm Measures. In places these have been subjected to severe folding, as can be seen on the north coast near Crackington Haven and in several other locations.

The Lizard Peninsula

The geology of the Lizard peninsula is unusual, in that it is mainland Britain's only example of an ophiolite, a section of oceanic crust now found on land.[50] Much of the peninsula consists of the dark green and red Precambrian serpentinite, which forms spectacular cliffs, notably at Kynance Cove, and carved and polished serpentine ornaments are sold in local gift shops. This ultramafic rock also forms a very infertile soil which covers the flat and marshy heaths of the interior of the peninsula. This is home to rare plants, such as the Cornish Heath, which has been adopted as the county flower.[51]

Ecology

Cornwall has varied habitats including terrestrial and marine ecosystems. One noted species in decline locally is the Reindeer lichen, which species has been made a priority for protection under the national UK Biodiversity Action Plan.[52][53]

Botanists divide Cornwall and Scilly into two vice-counties: West (1) and East (2). The standard flora is by F. H. Davey Flora of Cornwall (1909). Davey was assisted by A. O. Hume and he thanks Hume, his companion on excursions in Cornwall and Devon, and for help in the compilation of that Flora, publication of which was financed by him.

Climate

Cornwall has a temperate Oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfb) and has the mildest and sunniest climate in the United Kingdom, as a result of its southerly latitude and the influence of the Gulf Stream.[54] The average annual temperature in Cornwall ranges from 11.6 °C (53 °F) on the Isles of Scilly to 9.8 °C (50 °F) in the central uplands. Winters are amongst the warmest in the country due to the southerly latitude and moderating effects of the warm ocean currents, and frost and snow are very rare at the coast and are also rare in the central upland areas. The surrounding sea and its southwesterly position mean that Cornwall's weather can be relatively changeable.

Cornwall is one of the sunniest areas in the UK, with over 1541 hours of sunshine per year, with the highest average of 7.6 hours of sunshine per day in July.[55] The moist, mild air coming from the south west brings higher amounts of rainfall than in eastern Great Britain, at 1051 to 1290 mm (41.4 to 50.8 in) per year, however not as much as in more northern areas of the west coast.[56] The Isles of Scilly, for example, where there are on average less than 2 days of air frost per year, is the only area in the UK to be in the USDA Hardiness zone 10. In Scilly there is on average less than 1 day of air temperature exceeding 30 °C per year and it is in the AHS Heat Zone 1. Extreme temperatures in Cornwall are particularly rare; however, extreme weather in the form of storms and floods is common.

Politics and administration

Local politics

With the exception of the Isles of Scilly, Cornwall is now governed by a unitary authority known as Cornwall Council which is based in Truro. The only Crown Court is based at the Courts of Justice in Truro. Magistrates' Courts are to be found in Truro (but at a different location to the Crown Court); Bodmin; Penzance and Liskeard.

The Isles of Scilly form part of the ceremonial county of Cornwall and have, at times, been served by the same county administration. However, since 1890 they have been administered by their own unitary authority, now known as the Council of the Isles of Scilly. They are still grouped with Cornwall for other administrative purposes, such as the National Health Service and Devon and Cornwall Police.[57][58][59]

Before reorganisation on 1 April 2009, council functions throughout the rest of Cornwall were organised on a two-tier basis, with a county council and district councils for the six districts of Caradon, Carrick, Kerrier, North Cornwall, Penwith, and Restormel. While projected to streamline services, cut red tape and save around £17 million a year, the reorganisation was met with wide opposition, with a poll in 2008 giving a result of 89% disapproval from Cornish residents.[60][61][62]

The first elections for the new unitary authority were held on 4 June 2009. The new council has 123 seats; the largest party (in 2012) is the Conservative Party with 46, followed by the Liberal Democrats with 37, Independents with 23, Mebyon Kernow with 6 seats, 1 standalone independent and Labour with 1 seat. There are currently 2 vacant seats.[63]

Before the creation of the new unitary council, the former county council had 82 seats, the majority of which were held by the Liberal Democrats, elected at the 2005 county council elections. The six former districts in Cornwall had a total of 249 council seats, and the groups with greatest numbers of councillors were Liberal Democrats, Conservatives, and Independents.

Parliament and national politics

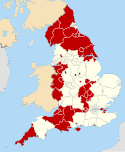

Following a review by the Boundary Commission for England taking effect at the 2010 general election, Cornwall is divided into six county constituencies to elect MPs to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom.

Before the 2010 boundary changes there were five constituencies in Cornwall, all of which were won by Liberal Democrats in the 2005 general election. However, at the 2010 general election Liberal Democrat candidates won three constituencies and Conservative candidates won three constituencies (see also 2010 United Kingdom general election result in Cornwall).

Until 1832, Cornwall had 44 MPs – more than any other county – reflecting the importance of tin to the Crown.[64] Most of the increase came between 1529 and 1584 after which there was no change until 1832.[65]

The chief registered parties contesting elections in Cornwall are Conservatives, Greens, Labour, Liberal Democrats, Mebyon Kernow, Liberal Party and the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP).

In 2007 David Cameron, leader of the Conservative Party, in a departure from the Conservative Party's traditionally unionist stance, appointed Cornishman Mark Prisk, MP for Hertford, Hertfordshire, England, as "Shadow Minister for Cornwall". This appointment was called "the fictional minister for Cornwall", by a Liberal Democrat MP, as there was no government minister to shadow.[66] The post was not continued following the 2010 election, and no longer exists.

Self-rule movement

Cornish nationalists have organised into two political parties: Mebyon Kernow, formed in 1951, and the Cornish Nationalist Party. In addition to the political parties, there are various interest groups such as the Revived Cornish Stannary Parliament and the Celtic League. The Cornish Constitutional Convention was formed in 2000 as a cross-party organisation including representatives from the private, public and voluntary sectors to campaign for the creation of a Cornish Assembly,[8][67] along the lines of the National Assembly for Wales, Northern Ireland Assembly and the Scottish Parliament. Between 5 March 2000 and December 2001, the campaign collected the signatures of 41,650 Cornish residents endorsing the call for a devolved assembly, along with 8,896 signatories from outside Cornwall. The resulting petition was presented to the then Prime Minister, Tony Blair.[8] The Liberal Democrats recognise Cornwall's claims for greater autonomy, as do the Liberal Party.

- "The new single council is also the opportunity to gain more control over local issues from regional and national Government bureaucrats – the first step on our way to a Cornish Assembly." – The Liberal Democrat Manifesto for 2009[68]

An additional political issue is the recognition of the Cornish people as a minority.[69]

Cornish national identity

Cornwall is recognised by several organisations, including the Cornish nationalist party Mebyon Kernow, the Celtic League and the International Celtic Congress, as one of the six Celtic nations, alongside Brittany, Ireland, the Isle of Man, Scotland and Wales.[70][71][72][73] Alongside Asturias and Galicia, Cornwall is also recognised as one of the eight Celtic nations by the Isle of Man Government and the Welsh Government.[74][75] Cornwall is represented, as one of the Celtic nations, at the Festival Interceltique de Lorient, an annual celebration of Celtic culture held in Brittany.[76]

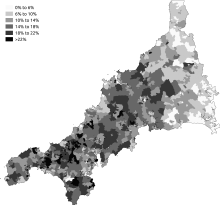

Cornwall Council consider Cornwall's unique cultural heritage and distinctiveness to be one of the area's major assets. They see Cornwall's language, landscape, Celtic identity, political history, patterns of settlement, maritime tradition, industrial heritage, and non-conformist tradition, to be among the features comprising its "distinctive" culture.[77] However, it is uncertain how many of the people living in Cornwall consider themselves to be Cornish; results from different surveys (including the national census) have varied. In the 2001 census, 7 percent of people in Cornwall identified themselves as Cornish, rather than British or English. However, activists have argued that this underestimated the true number as there was no explicit "Cornish" option included in the official census form.[78] Subsequent surveys have suggested that as many as 44 percent identify as Cornish.[79] Many people in Cornwall say that this issue would be resolved if a Cornish option became available on the census.[80] The question and content recommendations for the 2011 Census provided an explanation of the process of selecting an ethnic identity which is relevant to the understanding of the often quoted figure of 37,000 who claim Cornish identity.[81]

On 24 April 2014 it was announced that Cornish people would be granted minority status under the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.[9]

Settlements and communication

Cornwall's only city, and the home of the council headquarters, is Truro. Nearby Falmouth is notable as a port, while other ports such as Penzance, the most westerly coastal town in England, St Ives and Padstow have declined. Newquay on the north coast is famous for its beaches and is a popular surfing destination, as is Bude further north. St Austell is Cornwall's largest town and more populous than the capital Truro; it was the centre of the china clay industry in Cornwall. Redruth and Camborne together form the largest urban area in Cornwall, and both towns were significant as centres of the global tin mining industry in the 19th century (nearby copper mines were also very productive during that period).

Cornwall borders the county of Devon at the River Tamar. Major road links between Cornwall and the rest of Great Britain are the A38 which crosses the Tamar at Plymouth via the Tamar Bridge and the town of Saltash, the A39 road (Atlantic Highway) from Barnstaple, passing through North Cornwall to end eventually in Falmouth, and the A30 which crosses the border south of Launceston. Torpoint Ferry also links Plymouth with the town of Torpoint on the opposite side of the Hamoaze. A rail bridge, the Royal Albert Bridge, built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1859) provides the only other major transport link. The major city of Plymouth being the large urban centre closest to east Cornwall has made it an important location for such services as hospitals, department stores, road and rail transport, and cultural venues.

Newquay Cornwall International Airport provides an airlink to the rest of the UK, Ireland and Europe.

Cardiff and Swansea, across the Bristol Channel, are connected to Cornwall by ferry, usually to Padstow. Swansea in particular has several boat companies who can arrange boat trips to north Cornwall, which allow the traveller to pass by the north Cornish coastline, including Tintagel Castle and Padstow harbour. Very occasionally, the Waverley and Balmoral paddle steamers cruise from Swansea or Bristol to Padstow.

The Isles of Scilly are served by ferry (from Penzance) and by aeroplane (Land's End Airport, near St Just) and from Newquay Airport. Further flights to St. Mary's Airport, Isles of Scilly, are available from Exeter International Airport in Devon.

Flag

Saint Piran's Flag is regarded by many as the national flag of Cornwall,[82][83] and an emblem of the Cornish people; and by others as the county flag. The banner of Saint Piran is a white cross on a black background (in terms of heraldry 'sable, a cross argent'). Saint Piran is supposed to have adopted these two colours from seeing the white tin in the black coals and ashes during his supposed discovery of tin. Davies Gilbert in 1826 described it as anciently the flag of St Piran and the banner of Cornwall,[84] and another history of 1880 said that: "The white cross of St. Piran was the ancient banner of the Cornish people." The Cornish flag is an exact reverse of the former Breton national flag (black cross) and is known by the same name "Kroaz Du".

There are also claims that the patron saint of Cornwall is Saint Michael or Saint Petroc, but Saint Piran is by far the most popular of the three and his emblem is internationally[85][86] recognised as the flag of Cornwall. St Piran's Day (5 March) is celebrated by the Cornish diaspora around the world.

Heraldry

For the heraldry of Cornwall see:

Economy

Cornwall is one of the poorest parts of the United Kingdom in terms of per capita GDP and average household incomes. At the same time, parts of the county, especially on the coast, have high house prices, driven up by demand from relatively wealthy retired people and second-home owners.[87] The GVA per head was 65% of the UK average for 2004.[88] The GDP per head for Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly was 79.2% of the EU-27 average for 2004, the UK per head average was 123.0%.[89]

Historically mining of tin (and later also of copper) was important in the Cornish economy. The first reference to this appears to be by Pytheas: see above. Julius Caesar was the last classical writer to mention the tin trade, which appears to have declined during the Roman occupation.[90] The tin trade revived in the Middle Ages and its importance to the Kings of England resulted in certain privileges being granted to the tinners; the Cornish Rebellion of 1497 is attributed to grievances of the tin miners.[91] In the mid-19th century, however, the tin trade again fell into decline. Other primary industries that have declined since the 1960s include china clay production, fishing and farming.

Today, the Cornish economy depends heavily on its tourist industry, which makes up around a quarter of the economy. The official measures of deprivation and poverty at district and 'sub-ward' level show that there is great variation in poverty and prosperity in Cornwall with some areas among the poorest in England and others among the top half in prosperity. For example, the ranking of 32,482 sub-wards in England in the index of multiple deprivation (2006) ranged from 819th (part of Penzance East) to 30,899th (part of Saltash Burraton in Caradon), where the lower number represents the greater deprivation.[92]

Cornwall is one of four UK areas that qualify for poverty-related grants from the EU: it was granted Objective 1 status by the European Commission, followed by a further round of funding known as 'Convergence Funding'.

Tourism

Tourism is estimated to contribute up to 24% of Cornwall's gross domestic product.[93] Cornwall's unique culture, spectacular landscape and mild climate make it a popular tourist destination, despite being somewhat distant from the United Kingdom's main centres of population. Surrounded on three sides by the English Channel and Celtic Sea, Cornwall has many miles of beaches and cliffs; the South West Coast Path follows a complete circuit of both coasts. Other tourist attractions include moorland, country gardens, museums, historic and prehistoric sites, and wooded valleys. Five million tourists visit Cornwall each year, mostly drawn from within the UK.[94] Visitors to Cornwall are served by airports at Newquay and Exeter, whilst private jets, charters and helicopters are also served by Perranporth airfield; nightsleeper and daily rail services run between Cornwall, London and other regions of the UK. Cornwall has a tourism-based seasonal economy

Newquay and Porthtowan are popular destinations for surfers. In recent years, the Eden Project near St Austell has been a major financial success, drawing one in eight of Cornwall's visitors.[95]

Internet

Although Cornwall is remote and residential broadband is less common than in other parts of the UK it houses one of the world's fastest high-speed transatlantic fibre optic cables, making Cornwall an important hub within Europe's Internet infrastructure.[96]

Other industries

Other industries are fishing, although this has been significantly re-structured by EU fishing policies (the Southwest Handline Fishermen's Association has started to revive the fishing industry),[97] and agriculture, which has also declined significantly. Mining of tin and copper was also an industry, but today the derelict mine workings survive only as a World Heritage Site.[98] However, the Camborne School of Mines, which was relocated to Penryn in 2004, is still a world centre of excellence in the field of mining and applied geology[99] and the grant of World Heritage status has attracted funding for conservation and heritage tourism.[100] China clay extraction has also been an important industry in the St Austell area, but this sector has been in decline, and this, coupled with increased mechanisation, has led to a decrease in employment in this sector, although the industry still employs around 2,133 people in Cornwall, and generates over £80 Million to the local economy[101]

Demographics

Cornwall's population was 537,400 at the last count (2012), and population density 144 people per square kilometre, ranking it 40th and 41st respectively compared with the other 47 counties of England. Cornwall is 95.7% White British and has a relatively high level of population growth. At 11.2% in the 1980s and 5.3% in the 1990s, it has the fifth highest population growth of the English counties.[102] The natural change has been a small population decline, and the population increase is due to inward migration into Cornwall.[103] According to the 1991 census, the population was 469,800.

Cornwall has a relatively high retired population, with 22.9% of pensionable age, compared with 20.3% for the United Kingdom.[104] This may be due to a combination of Cornwall's rural and coastal geography increasing its popularity as a retirement location, and outward migration of younger residents to more economically diverse areas.

Education system

Cornwall has a comprehensive education system, with 31 state and 8 independent secondary schools. There are three further education colleges: Penwith College (a former sixth form college), Cornwall College (occupying the former home of the Camborne School of Mines) and Truro College. The Isles of Scilly only has one school while the former Restormel district has the highest school population, and school year sizes are around 200, with none above 270.

Higher education is provided by Falmouth University, the University of Exeter (including Camborne School of Mines), the Combined Universities in Cornwall, and by Truro College, Penwith College (which combined in 2008 to make Truro and Penwith College) and Cornwall College.

Languages and dialects

English is the main language used in Cornwall, although the revived Cornish language may be seen on road signs and is spoken fluently by a small minority of people.

Cornish language

The Cornish language is closely related to the other Brythonic languages of Welsh and Breton, and less so to the Goidelic languages of Irish, Scots Gaelic and Manx. The language continued to function visibly as a community language in parts of Cornwall until the late 18th century, and it was claimed in 2011 that the last native speaker did not die until 1914.[105]

There has been a revival of the language since Henry Jenner's Handbook of the Cornish Language was published in 1904. A study in 2000 suggested that there were around 300 people who spoke Cornish fluently.[106] Cornish, however, had no legal status in the UK until 2002. Nevertheless, the language is taught in about twelve primary schools, and occasionally used in religious and civic ceremonies.[107] In 2002 Cornish was officially recognised as a UK minority language[108] and in 2005 it received limited Government funding.[109] A Standard Written Form was agreed in 2008.[110]

Several Cornish mining words are still in use in English language mining terminology, such as costean, gunnies, vug,[111] kibbal,[112] gossan[113] and kieve.[citation needed]

Four of the current members in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, Andrew George, MP for St Ives, Dan Rogerson, MP for North Cornwall, Stephen Gilbert, MP for St Austell and Newquay, and Sarah Newton, MP for Truro and Falmouth repeated their Parliamentary oaths in Cornish.[114]

English dialect

Culture

Visual arts

Since the 19th century, Cornwall, with its unspoilt maritime scenery and strong light, has sustained a vibrant visual art scene of international renown. Artistic activity within Cornwall was initially centred on the art-colony of Newlyn, most active at the turn of the 20th century. This Newlyn School is associated with the names of Stanhope Forbes, Elizabeth Forbes,[115] Norman Garstin and Lamorna Birch.[116] Modernist writers such as D. H. Lawrence and Virginia Woolf lived in Cornwall between the wars,[117] and Ben Nicholson, the painter, having visited in the 1920s came to live in St Ives with his then wife, the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, at the outbreak of the second world war.[118] They were later joined by the Russian emigrant Naum Gabo,[119] and other artists. These included Peter Lanyon, Terry Frost, Patrick Heron, Bryan Wynter and Roger Hilton. St Ives also houses the Leach Pottery, where Bernard Leach, and his followers championed Japanese inspired studio pottery.[120] Much of this modernist work can be seen in Tate St Ives.[121] The Newlyn Society and Penwith Society of Arts continue to be active, and contemporary visual art is documented in a dedicated online journal.[122]

Music and festivals

Cornwall has a full and vibrant folk music tradition which has survived into the present and is well known for its unusual folk survivals such as Mummers Plays, the Furry Dance in Helston played by the famous Helston Town Band, and Obby Oss in Padstow.

As in other former mining districts of Britain, male voice choirs and Brass Bands, e.g. Brass on the Grass concerts during the summer at Constantine, are still very popular in Cornwall: Cornwall also has around 40 brass bands, including the six-times National Champions of Great Britain, Camborne Youth Band, and the bands of Lanner and St Dennis.

Cornish players are regular participants in inter-Celtic festivals, and Cornwall itself has several lively inter-Celtic festivals such as Perranporth's Lowender Peran folk festival.[123]

On a more modern note, contemporary musician Richard D. James (also known as Aphex Twin) grew up in Cornwall, as did Luke Vibert and Alex Parks winner of Fame Academy 2003. Roger Taylor, the drummer from the band Queen was also raised in the county, and currently lives not far from Falmouth. The American singer/songwriter Tori Amos now resides predominantly in North Cornwall not far from Bude with her family.[124] The lutenist, lutarist, composer and festival director Ben Salfield lives in Truro.

Literature

Cornwall's rich heritage and dramatic landscape have inspired writers since the 19th century.

Fiction

Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, author of many novels and works of literary criticism, lived in Fowey: his novels are mainly set in Cornwall. Daphne du Maurier lived at Menabilly near Fowey and many of her novels had Cornish settings, including Rebecca, Jamaica Inn, Frenchman's Creek, My Cousin Rachel, and The House on the Strand.[125] She is also noted for writing Vanishing Cornwall. Cornwall provided the inspiration for The Birds, one of her terrifying series of short stories, made famous as a film by Alfred Hitchcock.[126]

Medieval Cornwall is the setting of the trilogy by Monica Furlong, Wise Child, Juniper, and Colman, as well as part of Charles Kingsley's Hereward the Wake.

Conan Doyle's The Adventure of the Devil's Foot featuring Sherlock Holmes is set in Cornwall.[127] Winston Graham's series Poldark, Kate Tremayne's Adam Loveday series, Susan Cooper's novels Over Sea, Under Stone[128] and Greenwitch, and Mary Wesley's The Camomile Lawn are all set in Cornwall. Writing under the pseudonym of Alexander Kent, Douglas Reeman sets parts of his Richard Bolitho and Adam Bolitho series in the Cornwall of the late 18th and the early 19th centuries, particularly in Falmouth.

Hammond Innes's novel, The Killer Mine;[129] Charles de Lint's novel The Little Country;[130] and Chapters 24 and 25 of J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows take place in Cornwall (the Harry Potter story at Shell Cottage, which is on the beach outside the fictional village of Tinworth in Cornwall).[131]

David Cornwell, who writes espionage novels under the name John le Carré, lives and writes in Cornwall.[132] Nobel Prize-winning novelist William Golding was born in St Columb Minor in 1911, and returned to live near Truro from 1985 until his death in 1993.[133] D. H. Lawrence spent a short time living in Cornwall. Rosamunde Pilcher grew up in Cornwall, and several of her books take place there.

Poetry

The late Poet Laureate Sir John Betjeman was famously fond of Cornwall and it featured prominently in his poetry. He is buried in the churchyard at St Enodoc's Church, Trebetherick.[134] Charles Causley, the poet, was born in Launceston and is perhaps the best known of Cornish poets. Jack Clemo and the scholar A. L. Rowse were also notable Cornishmen known for their poetry; The Rev. R. S. Hawker of Morwenstow wrote some poetry which was very popular in the Victorian period. The Scottish poet W. S. Graham lived in West Cornwall from 1944 until his death in 1986.[135]

The poet Laurence Binyon wrote "For the Fallen" (first published in 1914) while sitting on the cliffs between Pentire Point and The Rumps and a stone plaque was erected in 2001 to commemorate the fact. The plaque bears the inscription "FOR THE FALLEN / Composed on these cliffs, 1914". The plaque also bears below this the fourth stanza (sometimes referred to as "The Ode") of the poem:

- They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old

- Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn

- At the going down of the sun and in the morning

- We will remember them

Other literary works

Cornwall produced a substantial number of passion plays such as the Ordinalia during the Middle Ages. Many are still extant, and provide valuable information about the Cornish language. See also Cornish literature

Prolific writer Colin Wilson, best known for his debut work The Outsider (1956) and for The Mind Parasites (1967), lives in Gorran Haven, a small village on the southern Cornish coast. The writer D. M. Thomas was born in Redruth but lived and worked in Australia and the United States before returning to his native Cornwall. He has written novels, poetry, and other works, including translations from Russian.

Thomas Hardy's drama The Queen of Cornwall (1923) is a version of the Tristan story; the second act of Richard Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde takes place in Cornwall, as do Gilbert and Sullivan's operettas The Pirates of Penzance and Ruddigore. A level of Tomb Raider: Legend, a game dealing with Arthurian Legend, takes place in Cornwall at a tacky museum above King Arthur's tomb.

The fairy tale Jack the Giant Killer takes place in Cornwall.

Sports and games

With its comparatively small, and largely rural population, major contribution by the Cornish to national sport in the United Kingdom has been limited,[136] with the county's greatest successes coming in fencing. In 2014, half of the men's GB team fenced for Truro Fencing Club, and 3 Truro fencers appeared at the 2012 Olympics.[citation needed] There are no teams affiliated to the Cornwall County Football Association that play in the Football League of England and Wales, and the Cornwall County Cricket Club plays as one of the minor counties of English cricket.[136] Viewed as an "important identifier of ethnic affiliation", rugby union has become a sport strongly tied to notions of Cornishness.[137] and since the 20th century, rugby union in Cornwall has emerged as one of the most popular spectator and team sports in Cornwall (perhaps the most popular), with professional Cornish rugby footballers being described as a "formidable force",[136] "naturally independent, both in thought and deed, yet paradoxically staunch English patriots whose top players have represented England with pride and passion".[138] In 1985, sports journalist Alan Gibson made a direct connection between love of rugby in Cornwall and the ancient parish games of hurling and wrestling that existed for centuries before rugby officially began.[138] Among Cornwall's native sports are a distinctive form of Celtic wrestling related to Breton wrestling, and Cornish hurling, a kind of mediaeval football played with a silver ball (distinct from Irish Hurling). Cornish Wrestling is Cornwall's oldest sport and as Cornwall's native tradition it has travelled the world to places like Victoria, Australia and Grass Valley, California following the miners and gold rushes. Cornish hurling now takes place at St. Columb Major, St Ives, and less frequently at Bodmin.[139]

Surfing and other water sports

Due to its long coastline, various maritime sports are popular in Cornwall, notably sailing and surfing. International events in both are held in Cornwall. Cornwall hosted the Inter-Celtic Watersports Festival in 2006. Surfing in particular is very popular, as locations such as Bude and Newquay offer some of the best surf in the UK. Pilot gig rowing has been popular for many years and the World championships takes place annually on the Isles of Scilly. On 2 September 2007, 300 surfers at Polzeath beach set a new world record for the highest number of surfers riding the same wave as part of the Global Surf Challenge and part of a project called Earthwave to raise awareness about global warming.[140]

Cuisine

Cornwall has a strong culinary heritage. Surrounded on three sides by the sea amid fertile fishing grounds, Cornwall naturally has fresh seafood readily available; Newlyn is the largest fishing port in the UK by value of fish landed.[141] Television chef Rick Stein has long operated a fish restaurant in Padstow for this reason, and Jamie Oliver recently chose to open his second restaurant, Fifteen, in Watergate Bay near Newquay. MasterChef host and founder of Smiths of Smithfield, John Torode, in 2007 purchased Seiners in Perranporth. One famous local fish dish is Stargazy pie, a fish-based pie in which the heads of the fish stick through the piecrust, as though "star-gazing". The pie is cooked as part of traditional celebrations for Tom Bawcock's Eve, but is not generally eaten at any other time.

Cornwall is perhaps best known though for its pasties, a savoury dish made with pastry. Today's pasties usually contain a filling of beef steak, onion, potato and swede with salt and white pepper, but historically pasties had a variety of different fillings. "Turmut, 'tates and mate" (i.e. "Turnip, potatoes and meat", turnip being the Cornish and Scottish term for swede, itself an abbreviation of 'Swedish Turnip') describes a filling once very common. For instance, the licky pasty contained mostly leeks, and the herb pasty contained watercress, parsley, and shallots.[142] Pasties are often locally referred to as oggies. Historically, pasties were also often made with sweet fillings such as jam, apple and blackberry, plums or cherries.[143] The wet climate and relatively poor soil of Cornwall make it unsuitable for growing many arable crops. However, it is ideal for growing the rich grass required for dairying, leading to the production of Cornwall's other famous export, clotted cream. This forms the basis for many local specialities including Cornish fudge and Cornish ice cream. Cornish clotted cream has Protected Geographical Status under EU law,[144] and cannot be made anywhere else. Its principal manufacturer is Rodda's, based at Scorrier.

Local cakes and desserts include Saffron cake, Cornish heavy (hevva) cake, Cornish fairings biscuits, figgy 'obbin, Cream tea and whortleberry pie.[145][146][147]

There are also many types of beers brewed in Cornwall – those produced by Sharp's Brewery, Skinner's Brewery and St Austell Brewery are the best-known – including stouts, ales and other beer types. There is some small scale production of wine, mead and cider.

See also

- Outline of England

- Celts

- Cornish Rex

- Cornwall (UK Parliament constituency) – Historical list of MPs for Cornwall Constituency

- Custos Rotulorum of Cornwall – Keeper of the Rolls

- Duchy of Cornwall

- Duke of Cornwall

- Duchess of Cornwall

- Ethnic groups in Europe

- High Sheriff of Cornwall

- List of Parliamentary constituencies in Cornwall

- Lord Lieutenant of Cornwall

References

- ^ The definition in Multitran dictionary

- ^ Definition of Cornwall in OED

- ^ Definition of "Cornwall" in Collins English Dictionary

- ^ International Hydrographic Organization

- ^ "Mid-Year Population Estimates, UK, June 2022". Office for National Statistics. 26 March 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Template:English district area citation

- ^ a b Stenton, F. M. (1947) Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Clarendon Press; p. 337

- ^ a b c "Blair gets Cornish assembly call". BBC. 11 December 2001. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- ^ a b "Cornish people granted minority status within UK". BBC. 24 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ a b Watts, Victor (2010). The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-names (1st paperback ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-521-16855-7.

- ^ Payton (2004), p. 50.

- ^ "Kingdoms of British Celts – Cornubia". The History Files. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ Deacon, Bernard (2007). A Concise History of Cornwall. University of Wales Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7083-2032-7.

- ^ Cunliffe, Karl, Guerra, McEvoy, Bradley; Oppenheimer, Rrvik, Isaac, Parsons, Koch, Freeman and Wodtko (2010). Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language and Literature. Oxbow Books and Celtic Studies Publications. p. 384. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2008). "A Race Apart: Insularity and Connectivity". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 75. The Prehistoric Society: 55–64 [61].

- ^ Payton (2004), p. 40.

- ^ Halliday (1959), p. 52.

- ^ "AD 500 – Tintagel". Archaeology.co.uk. 24 May 2007. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Annales Cambriae

- ^ Weatherhill, Craig Cornovia; p. 10

- ^ "The Foundation of the Kingdom of England". Third-millennium-library.com. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Annales Cambriae

- ^ Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (tr.) (1983), Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred and other contemporary sources, London, Penguin Books, p. 175; cf. ibid, p. 89

- ^ EMR Ditmas Breton Settlers in Cornwall after the Norman Conquest welshjournals.llgc.org.uk

- ^ EMR Ditmas, Tristan and Iseult Twelth Century Romance by Beroul retold from Norman French 1969

- ^ Williams, Ann & Martin, G. H. (2002) (tr.) Domesday Book: a complete translation, London: Penguin, pp. 341–357

- ^ Payton (2004), chapter 5.

- ^ Orme, Nicholas (2000) The Saints of Cornwall

- ^ "uny". Lelant.info. 5 January 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Doble, G. H. (1960) The Saints of Cornwall. 5 vols. Truro: Dean and Chapter, 1960–70

- ^ See for example absences from Olsen and Padel's "A tenth century list of Cornish parochial saints" in Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies; 12 (1986); and from Nova Legenda Angliae by John Capgrave (mid-15th century)

- ^ "St. Piran – Sen Piran". St-Piran.com. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ Henderson, Charles (1935) "Cornwall and her patron saint", In: his Essays in Cornish History. Oxford: Clarendon Press; pp. 197–201

- ^ Wyatt, Tim (2 May 2014). "Cornish welcome new status". Church Times. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ The cult of St Petroc was the most important in the Diocese of Cornwall since he was the founder of the monastery of Bodmin the most important in the diocese and, with St Germans, the seat of the bishops. He was the patron of the diocese and of Bodmin: Caroline Brett, "Petroc (fl. 6th cent.)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 16 December 2008

- ^ Charles-Edwards, T. (1970) "The Seven Bishop Houses of Dyfed," In: Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies, vol. 24, (1970–1972), pp. 247–252.

- ^ a b Orme, Nicholas (2007) Cornwall and the Cross. Chichester: Phillimore; p. 29

- ^ Thorn, Caroline, et al., eds. (1979) Cornwall. Chichester: Phillimore

- ^ Cornish Church Guide (1925) Truro: Blackford

- ^ Jenner, Henry (1925) "The Holy Wells of Cornwall". In: Cornish Church Guide. Truro: Blackford; pp. 249–257

- ^ Quiller-Couch, M. & L. (1894) Ancient and Holy Wells of Cornwall. London: Chas. J. Clark

- ^ Oliver, George (1846) Monasticon Dioecesis Exoniensis: being a collection of records and instruments illustrating the ancient conventual, collegiate, and eleemosynary foundations, in the Counties of Cornwall and Devon, with historical notices, and a supplement, comprising a list of the dedications of churches in the Diocese, an amended edition of the taxation of Pope Nicholas, and an abstract of the Chantry Rolls [with supplement and index]. Exeter: P. A. Hannaford, 1846, 1854, 1889

- ^ "The Prayer Book Rebellion 1549". TudorPlace.com.ar. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "Methodism". Cornish-Mining.org.uk. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ Shaw, Thomas (1967) A History of Cornish Methodism. Truro: Bradford Barton

- ^ "Truro Cathedral website – History page". TruroCathedral.org.uk. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ Brown, H. Miles (1976) A Century for Cornwall. Truro: Blackford

- ^ "Diocese of Plymouth". Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ^ "The Official Guide to the South West Coast Path". Southwestcoastpath.com. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Britain's only other example on an ophiolite, the Shetland ophiolite, is older, and linked to the Grampian Orogeny

- ^ Cornwall County Council, "The County Flower."

- ^ Price, J. H., Hepton, C. E. L. and Honey, S. I. (1979). The Inshore Benthic Biota of the Lizard Peninsula, south west Cornwall: the marine algae – History; Chlorophyta; Phaeophyta. Cornish Studies; no. 7: pp. 7–37

- ^ Bere, Rennie (1982) The Nature of Cornwall. Buckingham: Barracuda Books

- ^ Met Office, 2000. Annual average temperature for the United Kingdom.

- ^ Met Office, 2000. Annual average sunshine for the United Kingdom.

- ^ Met Office, 2000. Annual average rainfall for the United Kingdom.

- ^ "Isles of Scilly; Cornwall through time". visionofbritain.org.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- ^ "Isles of Scilly RD; Cornwall through time". visionofbritain.org.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- ^ "About your local police". Devon and Cornwall Police. Retrieved 23 September 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "One Cornwall – A unified council for Cornwall". Cornwall County Council. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Cornwall super-council go-ahead". BBC. 25 July 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ^ "Cornwall Council – Councillors". Cornwall Council. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ "British Archaeology, no 30, December 1997: Letters". Britarch.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Rowse, A. L. (1941) Tudor Cornwall. London: Cape; pp. 91–94

- ^ "The fictional minister for Cornwall". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Cornish Constitutional Convention (3 April 2005). "Campaign for a Cornish Assembly – Senedh Kernow". Cornishassembly.org. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "Minutes for the Census Sub-Group Meeting held on 23 November 2006". Central & Local Information Partnership. 9 February 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- ^ "Lords Hansard Text for 25 Jan 2011 (pt002)". Hansard. Parliament of the United Kingdom. 25 January 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

Cornwall sees itself as the fourth Celtic nation of the United Kingdom; Lord Teverson

- ^ "Mebyon Kernow – The Party for Cornwall – BETA". Mebyon Kernow website. Mebyon Kernow. 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ "The Celtic League". Celtic League website. Celtic League. 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ "The International Celtic Congress". International Celtic Congress. 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- ^ "Welsh Government: Minister in Paris for launch of Celtic festival". Welsh Government website. Welsh Government. 14 March 2002. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ "Isle of Man Post Office Website". Isle of Man Post Office website. Isle of Man Government. 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ "Site Officiel du Festival Interceltique de Lorient". Festival Interceltique de Lorient website. Festival Interceltique de Lorient. 4 February 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ "Cornwall Council – part three". Cornwall Council website. Cornwall Council. 18 March 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ Dugan, Emily (6 September 2009). "The Cornish: they revolted in 1497, now they're at it again". London: Independent (The). Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ "Welsh are more patriotic". BBC. 3 March 2004. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ "Information paper: Recommended questions for the 2009 Census Rehearsal and 2011 Census: National Identity" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. December 2008. p. 32. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ^ "2011 Census; 2011 census questionnaire content; question and content recommendations for 2011; ethnic group prioritisation tool" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. pp. 20–22. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ Rendle, Phil. "Cornwall – The Mysteries of St Piran" (PDF). Proceedings of the XIX International Congress of Vexillology. The Flag Institute. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ^ "Cross of Saint Piran". Flags of the World (FOTW). Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ^ Payton (2004), p. 262.

- ^ "Cornwall (United Kingdom)". Crwflags.com. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ "British Flags (United Kingdom) from The World Flag Database". Flags.net. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Dugan, Emily (27 July 2008). "Cornwall: A land of haves, and have nots". The Independent. London. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ ONS December 2006

- ^ Eurostat

- ^ Halliday (1959), p. 69.

- ^ Halliday (1959), p. 182.

- ^ Poverty and deprivation in Cornwall (June 2006) and Template:PDFlink

- ^ Cornwall Council: Cornwall's Challenges and Concerns – The Evidence Base. Retrieved 21 June 2011

- ^ Visit Cornwall, 2007. Template:PDFlink

- ^ Scottish Executive, 2004. A literature review of the evidence base for culture, the arts and sport policy.

- ^ Web in trouble? The hidden cables under a Cornish beach feeding the world's internet.

- ^ "Line-caught wild bass from Cornwall – South West Handline Fishermen's Association". Linecaught.org.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ UNESCO Page on the Cornwall & West Devon application

- ^ "The University of Exeter – Cornwall Campus – Camborne School of Mines". Uec.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ "Home". Cornish-mining.org.uk. 14 September 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Imerys Minerals Ltd (2003) Blueprint: Vision for the Future

- ^ Office for National Statistics, 2001. Population Change in England by County 1981–2000.

- ^ Office for National Statistics, 2001. Births, Deaths and Natural Change in Cornwall 1974 – 2001.

- ^ Office for National Statistics, 1996. % of Population of Pension Age (1996).

- ^ "Legend of Dolly Pentreath outlived her native tongue". This is Cornwall. 4 August 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ "Cornish in United Kingdom". European Commission. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "November 2002 – Cornish gains official recognition". BBC News. 6 November 2002. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ "June 2005 – Cash boost for Cornish language". BBC News. 14 June 2005. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ "An Outline of the Standard Written Form of Cornish" (PDF). Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Dictionary of Mining, Mineral, and Related Terms by American Geological Institute and U S Bureau of Mines; pp. 128, 249 & 613

- ^ "kibbal - Definition of kibbal - Online Dictionary from Datasegment.com". Onlinedictionary.datasegment.com. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ "gossan – definition of gossan by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". Thefreedictionary.com. 21 September 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ "MPs swear Oath of Allegiance in Cornish". Maga Kernow. 24 May 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ "Elizabeth Adela Forbes". PenleeHouse.org.uk. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "Samuel John Lamorna Birch". HayleGallery.co.uk. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "Virginia Woolf". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "Ben Nicholson". StormFineArts.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "Naum Gabo". Artnet.com. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "Bernard Leach and the Leach Pottery". Studio-Pots.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "Tate St Ives". Tate.org.uk. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "art and artists in Cornwall including Cornish galleries". art cornwall .org. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ "An-Daras.com".

- ^ Blackman, Guy (8 May 2005). "The whole Tori – Music – Entertainment". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ "Daphne du Maurier". DuMaurier.org. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "The Birds". MovieDiva.com. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "The Adventure of the Devil's Foot". WorldwideSchool.org. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "Over Sea, Under Stone". Powell's Books. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "The Killer Mine". BoekBesprekingen.nl. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "The Little Country". Amazon.com. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "Shell Cottage". hp-lexicon.org. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- ^ "Le Carré betrayed by 'bad lot' spy Kim Philby". Channel 4 News. London: Channel 4. 12 September 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ "Biography of William Golding". William-Golding.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 March 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "St Enodoc Church". RockInfo.co.uk. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "William Sydney Graham". CPRW.com. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ a b c Clegg 2005, p. 10.

- ^ Harvey, David (2002). Celtic Geographies: Old Culture, New Times. London: Routledge. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-415-22396-6.

- ^ a b Gallagher, Brendan (23 October 2008). "Cornish rugby union celebrate 125 years of pride and passion – but are they the lost tribe?". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ The Bodmin hurl is held whenever the ceremony of beating the bounds takes place: each occasion must be five years or more after the last one.

- ^ "BBC NEWS, Surfers aim to break world record". BBC News. 2 September 2007. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ "Objective One media release". Objectiveone.com. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ "Cornish recipe site". Alanrichards.org. 25 February 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Martin, Edith (1929). Cornish Recipes, Ancient & Modern. 22nd edition, 1965.

- ^ "Official list of British protected foods". Europa.eu.int. 23 February 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Mason, Laura; Brown, Catherine (1999) From Bath Chaps to Bara Brith. Totnes: Prospect Books

- ^ Pettigrew, Jane (2004) Afternoon Tea. Andover: Jarrold

- ^ Fitzgibbon, Theodora (1972) A Taste of England: the West Country. London: J. M. Dent

Sources

- Clegg, David (2005). Cornwall & the Isles of Scilly: the complete guide (2nd ed.). Leicester: Matador. ISBN 1-904744-99-0.

- Halliday, Frank Ernest (1959). A History of Cornwall. London: Gerald Duckworth. ISBN 0-7551-0817-5. A second edition was published in 2001 by the House of Stratus, Thirsk: the original text new illustrations and an afterword by Halliday's son

- Payton, Philip (2004). Cornwall: A History (2nd ed.). Fowey: Cornwall Editions Ltd. ISBN 1-904880-00-2.

Further reading

- Balchin, W. G. V. (1954) Cornwall: an illustrated essay on the history of the landscape. (The Making of the English Landscape). London: Hodder and Stoughton

- Boase, George Clement; Courtney, W. P. (1874–1882) Bibliotheca Cornubiensis: a catalogue of the writings, both manuscript and printed, of Cornishmen, and of works relating to the county of Cornwall, with biographical memoranda and copious literary references. 3 vols. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer

- du Maurier, Daphne (1967). Vanishing Cornwall. London: Doubleday. (illustrated edition Published by Victor Gollancz, London, 1981, ISBN 0-575-02844-0, photographs by Christian Browning)

- Ellis, Peter Berresford (1974). The Cornish Language and its Literature. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Books. ISBN 0-7100-7928-1. (Available online on Google Books).

- Graves, Alfred Perceval (1928). The Celtic Song Book: Being Representative Folk Songs of the Six Celtic Nations. London: Ernest Benn. (Available online on Digital Book Index)

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. London: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-440-7. (Available online on Google Books).

- Payton, Philip (1996). Cornwall. Fowey: Alexander Associates. ISBN 1-899526-60-9.

- Stoyle, Mark (2001). "BBC – History – The Cornish: A Neglected Nation?". BBC History website. BBC. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- Stoyle, Mark (2002). West Britons: Cornish Identities and the Early Modern British State. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. ISBN 0-85989-688-9.

- Williams, Michael (ed.) (1973) My Cornwall. St Teath: Bossiney Books (eleven chapters by various hands, including three previously published essays)