Emissions trading

| Part of a series about |

| Environmental economics |

|---|

|

Emissions trading or cap and trade ("cap" meaning a legal limit on the quantity of a certain type of chemical an economy can emit each year)[1] is a government-mandated, market-based approach used to control pollution by providing economic incentives for achieving reductions in the emissions of pollutants.[2] Various countries, groups of companies, and states have adopted emission trading systems as one of the strategies for mitigating climate-change by addressing international greenhouse-gas emission.[3]

A central authority (usually a governmental body) sets a limit or cap on the amount of a pollutant that may be emitted. The limit or cap is allocated and/or sold by the central authority to firms in the form of emissions permits which represent the right to emit or discharge a specific volume of the specified pollutant. Permits (and possibly also derivatives of permits) can then be traded on secondary markets.[4] For example, the EU ETS trades primarily in European Union Allowances (EUAs), the Californian scheme in California Carbon Allowances, the New Zealand scheme in New Zealand Units and the Australian scheme in Australian Units.[4] Firms are required to hold a number of permits (or allowances or carbon credits) equivalent to their emissions. The total number of permits cannot exceed the cap, limiting total emissions to that level. Firms that need to increase their volume of emissions must buy permits from those who require fewer permits.[2]

The transfer of permits is referred to as a "trade". In effect, the buyer is paying a charge for polluting, while the seller gains a reward for having reduced emissions. Thus, in theory, those who can reduce emissions most cheaply will do so, achieving the pollution reduction at the lowest cost to society.[5]

There are active trading programs in several air pollutants. For greenhouse gases the largest is the European Union Emission Trading Scheme, whose purpose is to avoid dangerous climate change.[6] Cap and trade provides the private sector with the flexibility required to reduce emissions while stimulating technological innovation and economic growth.[7] The United States has a national market to reduce acid rain and several regional markets in nitrogen oxides.[8]

Pollution as an externality

By definition, an externality is an activity of one entity that affects the welfare of another entity that is not a party to a market transaction related to that activity. Pollution is the prime example most economists think of when discussing externalities. There are various different ways to address these from a public economics perspective, including emissions fees, command and control regulation and cap-and-trade.

Overview

Described in its simplest form, an emissions trading system will consist of a number of participants, each of whom will have a cap, or limit, on their total emissions over a specified period of time. The cap will have been set by reference to the total emissions for a particular participant over a period of time, often referred to as its ‘baseline’, which is used as a reference point for future emissions reductions. Within a classic ‘cap and trade’ scheme, participants take on caps, or targets, requiring them to reduce their emissions and, in return, receive allowances equal to their individual caps. Participants can choose either to meet their cap by reducing their own emissions; to reduce their emissions below their cap and, perhaps, sell the excess allowances; or to let their emissions remain above their cap, and buy allowances from other participants. All that matters is that, when it comes to demonstrating compliance, every single participant holds allowances at least equal in number to its quantity of emissions. The result should then be that the total quantity of emissions will have been reduced to the sum of all the capped levels.[9]

The overall goal of an emissions trading plan is to minimize the cost of meeting a set emissions target or cap.[10] The cap is an enforceable limit on emissions that is usually lowered over time—aiming towards a national emissions reduction target.[10] The government sets an overall cap on emissions and creates allowances, or limited authorizations to emit, up to the level of the cap. Sources are free to buy or sell allowances or “bank” them to use in future years.[11] In some systems, a proportion of all traded permits must be retired periodically, causing a net reduction in emissions over time. In many cap-and-trade systems, organizations which do not pollute (and therefore have no obligations) may also participate in trading. Thus environmental groups may purchase and retire emission permits and hence drive up the price of the remaining permits according to the law of demand.[12] Corporations can also prematurely retire allowances by donating them to a nonprofit entity and then be eligible for a tax deduction.

"International trade can offer a range of positive and negative incentives to promote international cooperation on climate change (robust evidence, medium agreement). Three issues are key to developing constructive relationships between international trade and climate agreements: how existing trade policies and rules can be modified to be more climate friendly; whether border adjustment measures (BAMs) or other trade measures can be effective in meeting the goals of international climate agreements; whether the UNFCCC, World Trade Organization (WTO), hybrid of the two, or a new institution is the best forum for a trade-and-climate architecture."[13]

Definitions

According to the Environmental Defense Fund, cap and trade is the most environmentally and economically sensible approach to controlling greenhouse gas emissions, the primary driver of global warming. The "cap" sets a limit on emissions, which is lowered over time to reduce the amount of pollutants released into the atmosphere. The "trade" creates a market for carbon allowances, helping companies innovate in order to meet, or come in under, their allocated limit. The less they emit, the less they pay, so it is in their economic incentive to pollute less.[14]

The economics literature provides the following definitions of cap and trade emissions trading schemes.

A cap-and-trade system constrains the aggregate emissions of regulated sources by creating a limited number of tradable emission allowances,[15] which emission sources must secure and surrender in number equal to their emissions.[16]

In an emissions trading or cap-and-trade scheme, a limit on access to a resource (the cap) is defined and then allocated among users in the form of permits. Compliance is established by comparing actual emissions with permits surrendered including any permits traded within the cap.[17]

Under a tradable permit system, an allowable overall level of pollution is established and allocated among firms in the form of permits. Firms that keep their emission levels below their allotted level may sell their surplus permits to other firms or use them to offset excess emissions in other parts of their facilities.[18]

Market-based and least-cost

Economy-wide pricing of carbon is the centre piece of any policy designed to reduce emissions at the lowest possible costs.

Ross Garnaut, lead author of the Garnaut Climate Change Review [19]

Economists have urged the use of "market-based" instruments such as emissions trading to address environmental problems instead of prescriptive "command and control" regulation.[20] Command and control regulation is criticized for being excessively rigid, insensitive to geographical and technological differences, and inefficient.[21] However, emissions trading requires a cap to effectively reduce emissions, and the cap is a government regulatory mechanism. After a cap has been set by a government political process, individual companies are free to choose how or if they will reduce their emissions. Failure to report emissions and surrender emission permits is often punishable by a further government regulatory mechanism, such as a fine that increases costs of production. Firms will choose the least-cost way to comply with the pollution regulation, which will lead to reductions where the least expensive solutions exist, while allowing emissions that are more expensive to reduce.

Under an emissions trading system, emissions sources must meet a set of emissions target, but will have flexibility with regard to how they meet the target. An individual facility may purchase emissions reduction credits or allowances from other sources, sell credits or allowances, implement cost effective internal emissions reductions, or use a combination of both. This flexibility allows firms to use the most affordable compliance strategy, given their internal marginal abatement costs and the market price of allowances or emissions reductions or credits. In theory, a firm’s individual decisions should then lead to an economically efficient allocation of reductions and lower compliance costs for individual firms and for the programme overall, relative to more traditional command and control mechanisms.[22][23]

Emission markets

For emissions trading where greenhouse gases are regulated, one emissions permit or allowance is considered equivalent to one metric ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. Other names for emissions permits are carbon credits, Kyoto units, assigned amount units, and Certified Emission Reduction units (CER). These permits or units can be sold privately or in the international market at the prevailing market price. These trade and settle internationally and hence allow allowances to be transferred between countries. Each international transfer is validated by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Each transfer of ownership within the European Union is additionally validated by the European Commission.

Emissions trading programmes such as the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) complement the country-to-country trading provided for in the Kyoto Protocol by permitting private party trading of emissions permits. Under such programmes – which are generally co-ordinated with the national emissions targets provided within the framework of the Kyoto Protocol – a national or international authority allocates emissions permits to individual companies based on established criteria, with a view to meeting national and/or regional Kyoto targets at the lowest overall economic cost.[24]

Trading exchanges have been established to provide a spot market in permits, as well as futures and options market to help discover a market price and maintain liquidity. Carbon prices are normally quoted in euros per tonne of carbon dioxide or its equivalent (CO2e). Other greenhouse gases can also be traded, but are quoted as standard multiples of carbon dioxide with respect to their global warming potential. These features reduce the quota's financial impact on business, while ensuring that the quotas are met at a national and international level.

Currently there are six exchanges trading in UNFCCC related carbon credits: the Chicago Climate Exchange (until 2010[25]), European Climate Exchange, NASDAQ OMX Commodities Europe, PowerNext, Commodity Exchange Bratislava and the European Energy Exchange. NASDAQ OMX Commodities Europe listed a contract to trade offsets generated by a CDM carbon project called Certified Emission Reductions. Many companies now engage in emissions abatement, offsetting, and sequestration programs to generate credits that can be sold on one of the exchanges. At least one private electronic market has been established in 2008: CantorCO2e.[26] Carbon credits at Commodity Exchange Bratislava are traded at special platform - Carbon place.[27]

Trading in emission permits is one of the fastest-growing segments in financial services in the City of London with a market estimated to be worth about €30 billion in 2007. Louis Redshaw, head of environmental markets at Barclays Capital, predicts that "Carbon will be the world's biggest commodity market, and it could become the world's biggest market overall."[28]

History

The international community began the long process towards building effective international and domestic measures to tackle GHG[29](Carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydroflurocarbons, perfluorocarbons and sulphur hexafluoride.) emissions in response to the increasing certainty that global warming is happening and the uncertainty over its likely consequences. That process began in Rio in 1992, when 160 countries agreed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The UNFCCC is, as its title suggests, simply a framework; the necessary detail was left to be settled by the Conference of Parties (CoP) to the UNFCCC.[30]

The efficiency of what later was to be called the "cap-and-trade" approach to air pollution abatement was first demonstrated in a series of micro-economic computer simulation studies between 1967 and 1970 for the National Air Pollution Control Administration (predecessor to the United States Environmental Protection Agency's Office of Air and Radiation) by Ellison Burton and William Sanjour. These studies used mathematical models of several cities and their emission sources in order to compare the cost and effectiveness of various control strategies.[31][32][33][34][35] Each abatement strategy was compared with the "least cost solution" produced by a computer optimization program to identify the least costly combination of source reductions in order to achieve a given abatement goal. In each case it was found that the least cost solution was dramatically less costly than the same amount of pollution reduction produced by any conventional abatement strategy.[36] Burton and later Sanjour along with Edward H. Pechan continued improving [37] and advancing[38] these computer models at the newly created U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The agency introduced the concept of computer modeling with least cost abatement strategies (i.e. emissions trading) in its 1972 annual report to Congress on the cost of clean air.[39] This led to the concept of "cap and trade" as a means of achieving the "least cost solution" for a given level of abatement.

The development of emissions trading over the course of its history can be divided into four phases:[40]

- Gestation: Theoretical articulation of the instrument (by Coase,[41] Crocker,[42] Dales,[43] Montgomery[5] etc.) and, independent of the former, tinkering with "flexible regulation" at the US Environmental Protection Agency.

- Proof of Principle: First developments towards trading of emission certificates based on the "offset-mechanism" taken up in Clean Air Act in 1977. A company could get allowance from the Act on greater amount of emission when it paid another company to reduce the same pollutant.[44]

- Prototype: Launching of a first "cap-and-trade" system as part of the US Acid Rain Program in Title IV of the 1990 Clean Air Act, officially announced as a paradigm shift in environmental policy, as prepared by "Project 88", a network-building effort to bring together environmental and industrial interests in the US.

- Regime formation: branching out from the US clean air policy to global climate policy, and from there to the European Union, along with the expectation of an emerging global carbon market and the formation of the "carbon industry".

In the United States, the "acid rain"-related emission trading system was principally conceived by C. Boyden Gray, a G.H.W. Bush administration attorney. Gray worked with the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), who worked with the EPA to write the bill that became law as part of the Clean Air Act of 1990. The new emissions cap on NOx and SO2 gases took effect in 1995, and according to Smithsonian magazine, those acid rain emissions dropped 3 million tons that year.[45] In 1997, the CoP agreed, in what has been described as a watershed in international environmental treaty making, the Kyoto Protocol where 38 developed countries(Annex 1 countries.) committed themselves to targets and timetables for the reduction of GHGs.[46] These targets for developed countries are often referred to as Assigned Amounts.

One important economic reality recognised by many of the countries that signed the Kyoto Protocol is that, if countries have to solely rely on their own domestic measures, the resulting inflexible limitations on GHG growth could entail very large costs, perhaps running into many trillions of dollars globally.[47] As a result, international mechanisms which would allow developed countries flexibility to meet their targets were included in the Kyoto Protocol. The purpose of these mechanisms is to allow the parties to find the most economic ways to achieve their targets. These international mechanisms are outlined under Kyoto Protocol.[48]

On April 17, 2009, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) formally announced that it had found that greenhouse gas (GHG) poses a threat to public health and the environment (EPA 2009a). This announcement was significant because it gives the executive branch the authority to impose carbon regulations on carbon-emitting entities.[49]

A carbon cap-and-trade system is to be introduced nationwide in China in 2016[50] (China's National Development and Reform Commission proposed that an absolute cap be placed on emission by 2016.)[51]

Public relevance

An estimated 30–40% of the carbon dioxide emission in the atmosphere dissolves into oceans. It decreases pH in oceans, rivers and lakes. This also causes decreasing oxygen levels, killing off algae and marine ecosystems . In the oceans, CO2 concentrations have reached 450 parts-per-million (ppm) and above. Ocean acidification causes disruption of the calcification of marine organisms and the resultant risk of fundamentally altering marine food webs, the following guard rail should be obeyed: the pH of near surface waters should not drop more than 0.2 units below the pre-industrial average value in any larger ocean region.[52]

Members of the InterAcademy Panel expect emission to decrease to less than 50% of the 1990 level. Reducing the buildup of CO2 in the atmosphere is the only practicable solution to mitigating ocean acidification. To meet this target United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) would require substantial emission reductions in anthropogenic.[53]

Public opinion

In the United States, most polling shows large support for emissions trading (often referred to as cap-and-trade). This majority support can be seen in polls conducted by Washington Post/ABC News,[54] Zogby International[55] and Yale University.[56] A new Washington Post-ABC poll reveals that majorities of the American people believe in climate change, are concerned about it, are willing to change their lifestyles and pay more to address it, and want the federal government to regulate greenhouse gases. They are, however, ambivalent on cap-and-trade.[57]

More than three-quarters of respondents, 77.0%, reported they “strongly support” (51.0%) or “somewhat support” (26.0%) the EPA’s decision to regulate carbon emissions. While 68.6% of respondents reported being “very willing” (23.0%) or “somewhat willing” (45.6%), another 26.8% reported being “somewhat unwilling” (8.8%) or “not at all willing” (18.0%) to pay higher prices for “Green” energy sources to support funding for programs that reduce the effect of global warming.[57]

According to PolitiFact, it is a misconception that emissions trading is unpopular in the United States because of earlier polls from Zogby International and Rasmussen which misleadingly include "new taxes" in the questions (taxes aren't part of emissions trading) or high energy cost estimates.[58]

Comparison of cap and trade with other methods of emission reduction

Cap and trade, offsets created through a baseline(The point of comparison, often the historical emissions from a designated past year, against which emission reduction goals are measured.[59]) and credit(Credits can be distributed by the government for emission reductions achieved by offset projects or by achieving environmental performance beyond a regulatory standard.[59]) approach, and a carbon tax are all market-based approaches that put a price on carbon and other greenhouse gases, and provide an economic incentive to reduce emissions, beginning with the lowest-cost opportunities.

The textbook emissions trading program can be called a "cap and trade" approach in which an aggregate cap on all sources is established and these sources are then allowed to trade emissions permits amongst themselves to determine which sources actually emit the total pollution load. An alternative approach with important differences is a baseline and credit program.[60]

In a baseline and credit program polluters that are not under an aggregate cap can create permits or credits, usually called offsets, by reducing their emissions below a baseline level of emissions. Such credits can be purchased by polluters that have a regulatory limit.[61]

Cap and trade versus carbon tax and other methods

Cap and trade versus carbon tax

Regulation by cap-and-trade emissions trading can be compared to emissions fees or environmental tax approaches under a number of possible criteria.[62] Carbon Tax is a surcharge on the carbon content of fossil fuels that aims to discourage their use and thereby reduce carbon dioxide emissions, or a direct tax on CO2 emissions.[63]

Carbon tax and cap-and-trade usually provide similar effects to some extent as both of the methods increase the fossil fuels price; as a result, consumers, households in particular, will bear this consequence. [64]

Many commentators draw a sharp contrast between cap and trade and an alternative way to put a price on pollution: a carbon tax. In fact, cap and trade and carbon taxes are overlapping sets of policy designs. Like cap and trade, carbon taxes can have a range of scopes, points of regulation, and price schedules. And they can be fair or unfair, depending on how the revenue is used. A comprehensive, upstream, auctioned cap-and-trade system is very similar to a comprehensive, upstream carbon tax. The main difference is what’s certain and what’s uncertain. Under a carbon tax, elected officials set the price of carbon, and the market determines the quantity emitted; in auctioned cap and trade, elected officials set the quantity of carbon emitted, and the market sets the price.[65]

Responsiveness to inflation: In the case of inflation, cap-and-trade is at an advantage over emissions fees because it adjusts to the new prices automatically and no legislative or regulatory action is needed.

Responsiveness to cost changes: It is difficult to tell which is better between cap-and-trade and emissions fees; therefore, it might be a better option to combine the two resulting in the creation of a safety valve price (a price set by the government at which polluters can purchase additional permits beyond the cap).

Responsiveness to recessions: This point is closely related to responsiveness to cost changes, because recessions cause a drop in demand. Under cap and trade, the emissions cost automatically decreases, so a cap-and-trade scheme adds another automatic stabilizer to the economy - in effect, a type of automatic fiscal stimulus. However, if the emissions price drops to a low level, efforts to reduce emissions will also be reduced. Assuming that a government is competently able to stimulate the economy regardless of the cap-and-trade scheme, an excessively low price represents a missed opportunity to cut emissions faster than planned, so adding a price floor (or equivalently, switching to a tax temporarily) might be better - especially when there is great urgency about cutting emissions, as with greenhouse gas emissions. A price floor would also provide a degree of certainty and stability for investment in emissions reductions: recent experiences from the UK have shown that nuclear power operators are reluctant to invest on "un-subsidised" terms unless there is a guaranteed price floor for carbon (which the EU emissions trading scheme does not presently provide).

Responsiveness to uncertainty: As with cost changes, in a world of uncertainty, it is not clear whether emissions fees or cap-and-trade systems are more efficient—it basically depends on how fast the marginal social benefits of reducing pollution fall with the amount of cleanup (e.g., whether inelastic or elastic marginal social benefit schedule).

Summary: The main difference between carbon tax and cap-and-trade is that carbon tax acts as a price control while cap-and-trade method acts as a quantity control instrument.[64] The magnitude of the tax will therefore depend on how sensitive the supply of emissions is to the price. The permit of cap and trade will depend on the carbon market. Full auctioned equivalent emissions caps can in principle generate the same revenues as the carbon tax. A similar upstream cap and trade system could be implemented. An upstream carbon tax might be the simplest to administer. Setting up a complex cap and trade arrangement that is comprehensive has high institutional needs.[66]

Cap-and-trade versus command-and-control regulation

Command and Control is a system of regulation that prescribes emission limits and compliance methods on a facility-by-facility or source-by-source basis and that has been the traditional approach to reducing air pollution.[59]

Unlike emissions fees and cap and trade, which are incentive-based regulations, command-and-control regulations take a variety of forms and are much less flexible. An example of this is a performance standard which sets an emissions goal for each polluter that is fixed and, therefore, the burden of reducing pollution cannot be shifted to the firms that can achieve it more cheaply. As a result, performance standards are unlikely to be as cost effective as cap-and-trade emissions trading.[62] Firms would charge for a higher cost for a product and a proportion of such higher cost will be passed through to the end consumers.[67]

Economics of international emissions trading

| Part of a series on |

| World trade |

|---|

|

It is possible for a country to reduce emissions using a Command-Control approach, such as regulation, direct and indirect taxes. The cost of that approach differs between countries because the Marginal Abatement Cost Curve (MAC) — the cost of eliminating an additional unit of pollution — differs by country. It might cost China $2 to eliminate a ton of CO2, but it would probably cost Norway or the U.S. much more. International emissions-trading markets were created precisely to exploit differing MACs.

Example

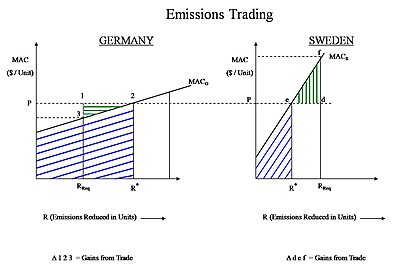

Emissions trading through Gains from Trade can be more beneficial for both the buyer and the seller than a simple emissions capping scheme.

Consider two European countries, such as Germany and Sweden. Each can either reduce all the required amount of emissions by itself or it can choose to buy or sell in the market.

For this example let us assume that Germany can abate its CO2 at a much cheaper cost than Sweden, i.e. MACS > MACG where the MAC curve of Sweden is steeper (higher slope) than that of Germany, and RReq is the total amount of emissions that need to be reduced by a country.

On the left side of the graph is the MAC curve for Germany. RReq is the amount of required reductions for Germany, but at RReq the MACG curve has not intersected the market emissions permit price of CO2 (market permit price = P = λ). Thus, given the market price of CO2 allowances, Germany has potential to profit if it abates more emissions than required.

On the right side is the MAC curve for Sweden. RReq is the amount of required reductions for Sweden, but the MACS curve already intersects the market price of CO2 permits before RReq has been reached. Thus, given the market price of CO2 permits, Sweden has potential to make a cost saving if it abates fewer emissions than required internally, and instead abates them elsewhere.

In this example, Sweden would abate emissions until its MACS intersects with P (at R*), but this would only reduce a fraction of Sweden's total required abatement.

After that it could buy emissions credits from Germany for the price P (per unit). The internal cost of Sweden's own abatement, combined with the permits it buys in the market from Germany, adds up to the total required reductions (RReq) for Sweden. Thus Sweden can make a saving from buying permits in the market (Δ d-e-f). This represents the "Gains from Trade", the amount of additional expense that Sweden would otherwise have to spend if it abated all of its required emissions by itself without trading.

Germany made a profit on its additional emissions abatement, above what was required: it met the regulations by abating all of the emissions that was required of it (RReq). Additionally, Germany sold its surplus permits to Sweden, and was paid P for every unit it abated, while spending less than P. Its total revenue is the area of the graph (RReq 1 2 R*), its total abatement cost is area (RReq 3 2 R*), and so its net benefit from selling emission permits is the area (Δ 1-2-3) i.e. Gains from Trade

The two R* (on both graphs) represent the efficient allocations that arise from trading.

- Germany: sold (R* - RReq) emission permits to Sweden at a unit price P.

- Sweden bought emission permits from Germany at a unit price P.

If the total cost for reducing a particular amount of emissions in the Command Control scenario is called X, then to reduce the same amount of combined pollution in Sweden and Germany, the total abatement cost would be less in the Emissions Trading scenario i.e. (X — Δ 123 - Δ def).

The example above applies not just at the national level: it applies just as well between two companies in different countries, or between two subsidiaries within the same company.

Applying the economic theory

The nature of the pollutant plays a very important role when policy-makers decide which framework should be used to control pollution.

CO2 acts globally, thus its impact on the environment is generally similar wherever in the globe it is released. So the location of the originator of the emissions does not really matter from an environmental standpoint.[68]

The policy framework should be different for regional pollutants[69] (e.g. SO2 and NOx, and also mercury) because the impact exerted by these pollutants may not be the same in all locations. The same amount of a regional pollutant can exert a very high impact in some locations and a low impact in other locations, so it does actually matter where the pollutant is released. This is known as the Hot Spot problem.

A Lagrange framework is commonly used to determine the least cost of achieving an objective, in this case the total reduction in emissions required in a year. In some cases it is possible to use the Lagrange optimization framework to determine the required reductions for each country (based on their MAC) so that the total cost of reduction is minimized. In such a scenario, the Lagrange multiplier represents the market allowance price (P) of a pollutant, such as the current market price of emission permits in Europe and the USA.[70]

Countries face the permit market price that exists in the market that day, so they are able to make individual decisions that would minimize their costs while at the same time achieving regulatory compliance. This is also another version of the Equi-Marginal Principle, commonly used in economics to choose the most economically efficient decision.

Prices versus quantities, and the safety valve

There has been longstanding debate on the relative merits of price versus quantity instruments to achieve emission reductions.[71]

An emission cap and permit trading system is a quantity instrument because it fixes the overall emission level (quantity) and allows the price to vary. Uncertainty in future supply and demand conditions (market volatility) coupled with a fixed number of pollution permits creates an uncertainty in the future price of pollution permits, and the industry must accordingly bear the cost of adapting to these volatile market conditions. The burden of a volatile market thus lies with the industry rather than the controlling agency, which is generally more efficient. However, under volatile market conditions, the ability of the controlling agency to alter the caps will translate into an ability to pick "winners and losers" and thus presents an opportunity for corruption.

In contrast, an emission tax is a price instrument because it fixes the price while the emission level is allowed to vary according to economic activity. A major drawback of an emission tax is that the environmental outcome (e.g. a limit on the amount of emissions) is not guaranteed. On one hand, a tax will remove capital from the industry, suppressing possibly useful economic activity, but conversely, the polluter will not need to hedge as much against future uncertainty since the amount of tax will track with profits. The burden of a volatile market will be borne by the controlling (taxing) agency rather than the industry itself, which is generally less efficient. An advantage is that, given a uniform tax rate and a volatile market, the taxing entity will not be in a position to pick "winners and losers" and the opportunity for corruption will be less.

Assuming no corruption and assuming that the controlling agency and the industry are equally efficient at adapting to volatile market conditions, the best choice depends on the sensitivity of the costs of emission reduction, compared to the sensitivity of the benefits (i.e., climate damage avoided by a reduction) when the level of emission control is varied.

Because there is high uncertainty in the compliance costs of firms, some argue that the optimum choice is the price mechanism. However, the burden of uncertainty cannot be eliminated, and in this case it is shifted to the taxing agency itself.

Some scientists have warned of a threshold in atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide beyond which a run-away warming effect could take place, with a large possibility of causing irreversible damage. If this is a conceivable risk then a quantity instrument could be a better choice because the quantity of emissions may be capped with a higher degree of certainty. However, this may not be true if this risk exists but cannot be attached to a known level of greenhouse gas (GHG) concentration or a known emission pathway.[72]

A third option, known as a safety valve, is a hybrid of the price and quantity instruments. The system is essentially an emission cap and permit trading system but the maximum (or minimum) permit price is capped. Emitters have the choice of either obtaining permits in the marketplace or purchasing them from the government at a specified trigger price (which could be adjusted over time). The system is sometimes recommended as a way of overcoming the fundamental disadvantages of both systems by giving governments the flexibility to adjust the system as new information comes to light. It can be shown that by setting the trigger price high enough, or the number of permits low enough, the safety valve can be used to mimic either a pure quantity or pure price mechanism.[73]

All three methods are being used as policy instruments to control greenhouse gas emissions: the EU-ETS is a quantity system using the cap and trading system to meet targets set by National Allocation Plans; Denmark has a price system using a carbon tax (World Bank, 2010, p. 218),[74] while China uses the CO2 market price for funding of its Clean Development Mechanism projects, but imposes a safety valve of a minimum price per tonne of CO2.

Carbon leakage

Carbon leakage is the effect that regulation of emissions in one country/sector has on the emissions in other countries/sectors that are not subject to the same regulation (Barker et al., 2007).[75] There is no consensus over the magnitude of long-term carbon leakage (Goldemberg et al., 1996, p. 31).[76]

In the Kyoto Protocol, Annex I countries are subject to caps on emissions, but non-Annex I countries are not. Barker et al.. (2007) assessed the literature on leakage. The leakage rate is defined as the increase in CO2 emissions outside of the countries taking domestic mitigation action, divided by the reduction in emissions of countries taking domestic mitigation action. Accordingly, a leakage rate greater than 100% would mean that domestic actions to reduce emissions had had the effect of increasing emissions in other countries to a greater extent, i.e., domestic mitigation action had actually led to an increase in global emissions.

Estimates of leakage rates for action under the Kyoto Protocol ranged from 5 to 20% as a result of a loss in price competitiveness, but these leakage rates were viewed as being very uncertain.[77] For energy-intensive industries, the beneficial effects of Annex I actions through technological development were viewed as possibly being substantial. This beneficial effect, however, had not been reliably quantified. On the empirical evidence they assessed, Barker et al. (2007) concluded that the competitive losses of then-current mitigation actions, e.g., the EU ETS, were not significant.

Under the EU ETS rules Carbon Leakage Exposure Factor is used to determine the volumes of free allocation of emission permits to industrial installations.

Trade

To understand carbon trading, it is important to understand the products that are being traded. The primary product in carbon markets is the trading of GHG emission allowances. Under a cap and trade system, permits are issued to various entities for the right to emit GHG emissions that meet emission reduction requirement caps.[49]

One of the controversies about carbon mitigation policy thus arises about how to "level the playing field" with border adjustments.[78] One component of the American Clean Energy and Security Act, for example, along with several other energy bills put before Congress, calls for carbon surcharges on goods imported from countries without cap-and-trade programs. Even aside from issues of compliance with the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, such border adjustments presume that the producing countries bear responsibility for the carbon emissions.

A general perception among developing countries is that discussion of climate change in trade negotiations could lead to "green protectionism" by high-income countries (World Bank, 2010, p. 251).[74] Tariffs on imports ("virtual carbon") consistent with a carbon price of $50 per ton of CO2 could be significant for developing countries. World Bank (2010) commented that introducing border tariffs could lead to a proliferation of trade measures where the competitive playing field is viewed as being uneven. Tariffs could also be a burden on low-income countries that have contributed very little to the problem of climate change.

Trading systems

Kyoto Protocol

As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports came in over the years, they shed abundant light on the true state of global warming and they gave support to the environmental effort to address this unprecedented problem. However, the same discussions that started decades back had never ceased and the crusade for a tangible solution to global climate change had gone on all the while. In 1997 the Kyoto Protocol was adopted. The Kyoto Protocol is a 1997 international treaty that came into force in 2005. In the treaty, most developed nations agreed to legally binding targets for their emissions of the six major greenhouse gases.[79] Emission quotas (known as "Assigned amounts") were agreed by each participating 'Annex I' country, with the intention of reducing the overall emissions by 5.2% from their 1990 levels by the end of 2012. The United States is the only industrialized nation under Annex I that has not ratified the treaty, and is therefore not bound by it. The IPCC has projected that the financial effect of compliance through trading within the Kyoto commitment period will be limited at between 0.1-1.1% of GDP among trading countries.[80] The agreement was intended to result in industrialized countries' emissions declining in aggregate by 5.2 percent below 1990 levels by the year of 2012. Despite the failure of the United States and Australia to ratify the protocol, the agreement became effective in 2005, once the requirement that 55 Annex I (predominantly industrialized) countries, jointly accounting for 55 percent of 1990 Annex I emissions, ratify the agreement was met.[81]

The Protocol defines several mechanisms ("flexible mechanisms") that are designed to allow Annex I countries to meet their emission reduction commitments (caps) with reduced economic impact (IPCC, 2007).[82]

Under Article 3.3 of the Kyoto Protocol, Annex I Parties may use GHG removals, from afforestation and reforestation (forest sinks) and deforestation (sources) since 1990, to meet their emission reduction commitments.[83]

Annex I Parties may also use International Emissions Trading (IET). Under the treaty, for the 5-year compliance period from 2008 until 2012,[84] nations that emit less than their quota will be able to sell assigned amount units (each AAU representing an allowance to emit one metric tonne of CO2) to nations that exceed their quotas.[85] It is also possible for Annex I countries to sponsor carbon projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions in other countries. These projects generate tradable carbon credits that can be used by Annex I countries in meeting their caps. The project-based Kyoto Mechanisms are the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Joint Implementation (JI). There are four such international flexible mechanisms, or Kyoto Mechanism[86] written in the Kyoto Protocol.

Article 17 if the Protocol authorizes Annex 1 countries that have agreed to the emissions limitations to take part in emissions trading with other Annex 1 Countries.

Article 4 authorizes such parties to implement their limitations jointly, as the member states of the EU have chosen to do.

Article 6 provides that such Annex 1 countries may take part in joint initiatives (JIs) in return for emissions reduction units (ERUs) to be used against their Assigned Amounts.

Art 12 provides for a mechanism known as the clean development mechanism (CDM),[87] under which Annex 1 countries may invest in emissions limitation projects in developing countries and use certified emissions reductions (CERs) generated against their own Assigned Amounts. [88]

The CDM covers projects taking place in non-Annex I countries, while JI covers projects taking place in Annex I countries. CDM projects are supposed to contribute to sustainable development in developing countries, and also generate "real" and "additional" emission savings, i.e., savings that only occur thanks to the CDM project in question (Carbon Trust, 2009, p. 14).[89] Whether or not these emission savings are genuine is, however, difficult to prove (World Bank, 2010, pp. 265–267).[74]

Australia

In 2003 the New South Wales (NSW) state government unilaterally established the NSW Greenhouse Gas Abatement Scheme[90] to reduce emissions by requiring electricity generators and large consumers to purchase NSW Greenhouse Abatement Certificates (NGACs). This has prompted the rollout of free energy-efficient compact fluorescent lightbulbs and other energy-efficiency measures, funded by the credits. This scheme has been criticised by the Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets (CEEM) of the UNSW because of its lack of effectiveness in reducing emissions, its lack of transparency and its lack of verification of the additionality of emission reductions.[91]

Both the incumbent Howard Coalition government and the Rudd Labor opposition promised to implement an emissions trading scheme (ETS) before the 2007 federal election. Labor won the election, with the new government proceeding to implement an ETS. The government introduced the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, which the Liberals supported with Malcolm Turnbull as leader. Tony Abbott questioned an ETS, saying the best way to reduce emissions is with a "simple tax".[92] Shortly before the carbon vote, Abbott defeated Turnbull in a leadership challenge, and from there on the Liberals opposed the ETS. This left the government unable to secure passage of the bill and it was subsequently withdrawn.

Julia Gillard defeated Rudd in a leadership challenge and promised not to introduce a carbon tax, but would look to legislate a price on carbon [93] when taking the government to the 2010 election. In the first hung parliament result in 70 years, the government required the support of crossbenchers including the Greens. One requirement for Greens support was a carbon price, which Gillard proceeded with in forming a minority government. A fixed carbon price would proceed to a floating-price ETS within a few years under the plan. The fixed price leant itself to characterisation as a carbon tax and when the government proposed the Clean Energy Bill in February 2011,[94] the opposition claimed it to be a broken election promise.[95]

The bill was passed by the Lower House in October 2011[96] and the Upper House in November 2011.[97] The Liberal Party vowed to overturn the bill if elected.[98]

The Liberal/National coalition government elected in September 2013 has promised to reverse the climate legislation of the previous government.[99] In July 2014, the carbon tax was repealed as well as the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) that was to start in 2015.[100]

New Zealand

The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS) is a partial-coverage all-free allocation uncapped highly internationally linked emissions trading scheme. The NZ ETS was first legislated in the Climate Change Response (Emissions Trading) Amendment Act 2008 in September 2008 under the Fifth Labour Government of New Zealand[101][102] and then amended in November 2009[103] and in November 2012[104] by the Fifth National Government of New Zealand.

The NZ ETS covers forestry (a net sink), energy (43.4% of total 2010 emissions), industry (6.7% of total 2010 emissions) and waste (2.8% of total 2010 emissions) but not pastoral agriculture (47% of 2010 total emissions).[105] Participants in the NZ ETS must surrender one emission unit (either an international 'Kyoto' unit or a New Zealand-issued unit) for every two tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions reported or they may choose to buy NZ units from the government at a fixed price of NZ$25.[106]

Individual sectors of the economy have different entry dates when their obligations to report emissions and surrender emission units take effect. Forestry, which contributed net removals of 17.5 Mts of CO2e in 2010 (19% of NZ's 2008 emissions,[107]) entered the NZ ETS on 1 January 2008.[108] The stationary energy, industrial processes and liquid fossil fuel sectors entered the NZ ETS on 1 July 2010. The waste sector (landfill operators) entered on 1 January 2013.[109] Methane and nitrous oxide emissions from pastoral agriculture are not included in the NZ ETS. (From November 2009, agriculture was to enter the NZ ETS on 1 January 2015[106])

The NZ ETS is highly linked to international carbon markets as it allows the importing of most of the Kyoto Protocol emission units. However, as of June 2015, the scheme will effectively transition into a domestic scheme, with restricted access to international Kyoto units (CERs, ERUs and RMUs).[110] It also creates a specific domestic unit; the 'New Zealand Unit' (NZU), which is issued by free allocation to emitters, with no auctions intended in the short term.[111] Free allocation of NZUs varies between sectors. The commercial fishery sector (who are not participants) have a free allocation of units on a historic basis.[106] Owners of pre-1990 forests have received a fixed free allocation of units.[108] Free allocation to emissions-intensive industry,[112][113] is provided on an output-intensity basis. For this sector, there is no set limit on the number of units that may be allocated.[114] The number of units allocated to eligible emitters is based on the average emissions per unit of output within a defined 'activity'.[115] Bertram and Terry (2010, p 16) state that as the NZ ETS does not 'cap' emissions, the NZ ETS is not a cap and trade scheme as understood in the economics literature.[116]

Some stakeholders have criticized the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme for its generous free allocations of emission units and the lack of a carbon price signal (the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment),[117] and for being ineffective in reducing emissions (Greenpeace Aotearoa New Zealand).[118]

The NZ ETS was reviewed in late 2011 by an independent panel, which reported to the Government and public in September 2011.[119]

European Union

The European Union Emission Trading Scheme (or EU ETS) is the largest multi-national, greenhouse gas emissions trading scheme in the world. It is one of the EU's central policy instruments to meet their cap set in the Kyoto Protocol (Jones et al.., 2007, p. 64).[120]

After voluntary trials in the UK and Denmark, Phase I commenced operation in January 2005 with all 15 member states of the European Union participating.[121] The program caps the amount of carbon dioxide that can be emitted from large installations with a net heat supply in excess of 20 MW, such as power plants and carbon intensive factories[122] and covers almost half (46%) of the EU's Carbon Dioxide emissions.[123] Phase I permits participants to trade amongst themselves and in validated credits from the developing world through Kyoto's Clean Development Mechanism.Credits are gained by helping and investmenting in clean technologies and low-carbon solutions. It is also generated by certain types of emission-saving projects around the world to cover a proportion of their emissions.[124]

During Phases I and II, allowances for emissions have typically been given free to firms, which has resulted in them getting windfall profits (CCC, 2008, p. 149).[125] Ellerman and Buchner (2008) (referenced by Grubb et al.., 2009, p. 11) suggested that during its first two years in operation, the EU ETS turned an expected increase in emissions of 1-2 percent per year into a small absolute decline.[126] Grubb et al.. (2009, p. 11) suggested that a reasonable estimate for the emissions cut achieved during its first two years of operation was 50-100 MtCO2 per year, or 2.5-5 percent.

A number of design flaws have limited the effectiveness of scheme (Jones et al.., 2007, p. 64). In the initial 2005-07 period, emission caps were not tight enough to drive a significant reduction in emissions (CCC, 2008, p. 149). The total allocation of allowances turned out to exceed actual emissions. This drove the carbon price down to zero in 2007. This oversupply was caused because the allocation of allowances by the EU was based on emissions data from the European Environmental Agency in Copenhagen, which uses a horizontal activity based emissions definition similar to the United Nations, the EU ETS Transaction log in Brussels however uses a vertical installation based emissions measurement system. This caused an oversupply of 200 million tonnes (10% of market) in the EU ETS in the first phase and collapsing prices.[127]

Phase II saw some tightening, but the use of JI and CDM offsets was allowed, with the result that no reductions in the EU will be required to meet the Phase II cap (CCC, 2008, pp. 145, 149). For Phase II, the cap is expected to result in an emissions reduction in 2010 of about 2.4% compared to expected emissions without the cap (business-as-usual emissions) (Jones et al.., 2007, p. 64). For Phase III (2013–20), the European Commission has proposed a number of changes, including:

- the setting of an overall EU cap, with allowances then allocated to EU members;

- tighter limits on the use of offsets;

- unlimited banking of allowances between Phases II and III;

- and a move from allowances to auctioning.

In January 2008, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein joined the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), according to a publication from the European Commission.[128] The Norwegian Ministry of the Environment has also released its draft National Allocation Plan which provides a carbon cap-and-trade of 15 million metric tonnes of CO2, 8 million of which are set to be auctioned.[129][citation needed] According to the OECD Economic Survey of Norway 2010, the nation "has announced a target for 2008-12 10% below its commitment under the Kyoto Protocol and a 30% cut compared with 1990 by 2020." [130] In 2012, EU-15 emissions stood 15.1% below their base year level. Based on figures for 2012 by the European Environment Agency, EU-15 emissions averaged 11.8% below base-year levels during the 2008-2012 period. This means the EU-15 over-achieved its first Kyoto target by a wide margin.[131]

Tokyo, Japan

The Japanese city of Tokyo is like a country in its own right in terms of its energy consumption and GDP. Tokyo consumes as much energy as "entire countries in Northern Europe, and its production matches the GNP of the world's 16th largest country".[132] Originally, Japan had a voluntary emissions reductions system that had been in place for some years, but was not effective.[133] Japan has its own emission reduction policy but not a nationwide cap and trade program. This climate strategy is enforced and overseen by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG).[134] The scheme launched in April 2010, covers the top 1,400 emitters in the metropolitan area.[135] The first phase, which is alike to Japan's scheme, runs up to 2015, these organizations will have to cut their carbon emissions by 6% or 8% (depending on the type of organization); those who fail to operate within their emission caps will from 2011 on be required to purchase emission allowances to cover any excess emissions, or alternatively, invest in renewable energy certificates or offset credits issued by smaller businesses or branch offices.[136] Firms whom fail to comply will face fines of up to 500,000 yen plus an amount of credits to equal the emissions 1.3 times the amount they failed to reduce during the first phase of the scheme.[137] In the second phase (FY2015-FY2019), the target is expected to increase to 15%-17%. In its fourth year of operation, emissions were reduced by 23% compared to base-year emissions.[138] The long term aim is to cut the metropolis' carbon emissions by 25% from 2000 levels by 2020.[136] These emission limits can be met by using technologies such as solar panels and advanced fuel-saving devices. [135]

United States

An early example of an emission trading system has been the SO2 trading system under the framework of the Acid Rain Program of the 1990 Clean Air Act in the U.S. Under the program, which is essentially a cap-and-trade emissions trading system, SO2 emissions were reduced by 50% from 1980 levels by 2007.[139] Some experts argue that the cap-and-trade system of SO2 emissions reduction has reduced the cost of controlling acid rain by as much as 80% versus source-by-source reduction.[20][140] The SO2 program was challenged in 2004, which set in motion a series of events that led to the 2011 Cross-State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR). Under the CSAPR, the national SO2 trading program was replaced by four separate trading groups for SO2 and NOx.[141]

In 1997, the State of Illinois adopted a trading program for volatile organic compounds in most of the Chicago area, called the Emissions Reduction Market System.[142] Beginning in 2000, over 100 major sources of pollution in eight Illinois counties began trading pollution credits.

In 2003, New York State proposed and attained commitments from nine Northeast states to form a cap-and-trade carbon dioxide emissions program for power generators, called the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). This program launched on January 1, 2009 with the aim to reduce the carbon "budget" of each state's electricity generation sector to 10% below their 2009 allowances by 2018.[143]

Also in 2003, U.S. corporations were able to trade CO2 emission allowances on the Chicago Climate Exchange under a voluntary scheme. In August 2007, the Exchange announced a mechanism to create emission offsets for projects within the United States that cleanly destroy ozone-depleting substances.[144]

Also in 2003, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began to administer the NOx Budget Trading Program (NBP)under the NOx State Implementation Plan (also known as the "NOx SIP Call") The NOx Budget Trading Program was a market-based cap and trade program created to reduce emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) from power plants and other large combustion sources in the eastern United States. NOx is a prime ingredient in the formation of ground-level ozone (smog), a pervasive air pollution problem in many areas of the eastern United States. The NBP was designed to reduce NOx emissions during the warm summer months, referred to as the ozone season, when ground-level ozone concentrations are highest. In March 2008, EPA again strengthened the 8-hour ozone standard to 0.075 parts per million (ppm) from its previous 0.008 ppm.[145]

In 2006, the California Legislature passed the California Global Warming Solutions Act, AB-32, which was signed into law by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. Thus far, flexible mechanisms in the form of project based offsets have been suggested for three main project types. The project types include: manure management, forestry, and destruction of ozone-depleted substances. However, a recent ruling from Judge Ernest H. Goldsmith of San Francisco's Superior Court states that the rules governing California's cap-and-trade system were adopted without a proper analysis of alternative methods to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.[146] The tentative ruling, issued on January 24, 2011, argues that the California Air Resources Board violated state environmental law by failing to consider such alternatives. If the decision is made final, the state would not be allowed to implement its proposed cap-and-trade system until the California Air Resources Board fully complies with the California Environmental Quality Act.[147]

In February 2007, five U.S. states and four Canadian provinces joined together to create the Western Climate Initiative (WCI), a regional greenhouse gas emissions trading system.[148] In July 2010, a meeting took place to further outline the cap-and-trade system.[149] In November 2011, Arizona, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah and Washington withdrew from the WCI.[citation needed]

On November 17, 2008 President-elect Barack Obama clarified, in a talk recorded for YouTube, his intentions for the US to enter a cap-and-trade system to limit global warming.[150]

SO2 emissions from Acid Rain Program sources have fallen from 17.3 million tons in 1980 to about 7.6 million tons in 2008, a decrease in emissions of 56 percent. Ozone season NOx emissions decreased by 43 percent between 2003 and 2008, even while energy demand remained essentially flat during the same period. CAIR will result in $85 billion to $100 billion in health benefits and nearly $2 billion in visibility benefits per year by 2015 and will substantially reduce premature mortality in the eastern United States.[citation needed] A recent EPA analysis shows that implementation of the Acid Rain Program is expected[by whom?] to reduce between 20,000 and 50,000 incidences of premature mortality annually due to reductions of ambient PM2.5 concentrations, and between 430 and 2,000 incidences annually due to reductions of ground-level ozone. NOx reductions due to the NOx Budget Trading Program have led to improvements in ozone and PM2.5, saving an estimated 580 to 1,800 lives in 2008.[151]

The 2010 United States federal budget proposes to support clean energy development with a 10-year investment of US $15 billion per year, generated from the sale of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions credits. Under the proposed cap-and-trade program, all GHG emissions credits would be auctioned off, generating an estimated $78.7 billion in additional revenue in FY 2012, steadily increasing to $83 billion by FY 2019.[152]

The American Clean Energy and Security Act (H.R. 2454), a greenhouse gas cap-and-trade bill, was passed on June 26, 2009, in the House of Representatives by a vote of 219-212. The bill originated in the House Energy and Commerce Committee and was introduced by Representatives Henry A. Waxman and Edward J. Markey.[153] The political advocacy organizations FreedomWorks and Americans for Prosperity, funded by brothers David and Charles Koch of Koch Industries, encouraged the Tea Party movement to focus on defeating the legislation.[154][155] Although cap and trade also gained a significant foothold in the Senate via the efforts of Republican Lindsey Graham, Independent Democrat Joe Lieberman, and Democrat John Kerry,[156] the legislation died in the Senate.[157]

South Korea

South Korea's national emissions trading scheme officially launched on 1 January 2015, covering 525 entities from 23 sectors. With a three-year cap of 1.8687 billion tCO2e, it now forms the second largest carbon market in the world following the EU ETS.This amounts to roughly two thirds of the country's emissions. The Korean emissions trading scheme is part of the Republic of Korea's efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30% compared to the business-as-usual scenario by 2020.[158]

China

In November 2011, China approved pilot tests of carbon trading in seven provinces and cities – Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Tianjin as well as Guangdong Province and Hubei Province, with different prices in each region.[159] The pilot is intended to test the waters and provide valuable lessons for the design of a national system in the near future. Their successes or failures will therefore have far reaching implications for carbon market development in China in terms of trust in a national carbon trading market. Some of the pilot regions can start trading as early as 2013/2014. National trading is expected to start 2016.[160]

India

Trading is set to begin in 2014 after a three-year rollout period. It is a mandatory energy efficiency trading scheme covering eight sectors responsible for 54 per cent of India’s industrial energy consumption. India has pledged a 20 to 25 per cent reduction in emissions intensity from 2005 levels by 2020. Under the scheme, annual efficiency targets will be allocated to firms. Tradable energy-saving permits will be issued depending on the amount of energy saved during a target year.[160]

Renewable energy certificates

Renewable Energy Certificates (occasionally referred to as or "green tags" [citation required]), are a largely unrelated form of market-based instruments that are used to achieve renewable energy targets, which may be environmentally motivated (like emissions reduction targets), but may also be motivated by other aims, such as energy security or industrial policy.

Carbon market

Carbon emissions trading is emissions trading specifically for carbon dioxide (calculated in tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent or tCO2e) and currently makes up the bulk of emissions trading. It is one of the ways countries can meet their obligations under the Kyoto Protocol to reduce carbon emissions and thereby mitigate global warming.

Market trend

Trading can be done directly between buyers and sellers, through several organised exchanges or through the many intermediaries active in the carbon market. The price of allowances is determined by supply and demand. As many as 40 million allowances have been traded per day. In 2012, 7.9 billion allowances were traded with a total value of €56 billion.[124] Carbon emissions trading declined in 2013, and is expected to decline in 2014.[161]

According to the World Bank's Carbon Finance Unit, 374 million metric tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) were exchanged through projects in 2005, a 240% increase relative to 2004 (110 mtCO2e)[162] which was itself a 41% increase relative to 2003 (78 mtCO2e).[163]

Global carbon markets have shrunk in value by 60% since 2011, but are expected to rise again in 2014.[164]

In terms of dollars, the World Bank has estimated that the size of the carbon market was 11 billion USD in 2005, 30 billion USD in 2006,[162] and 64 billion in 2007.[165]

The Marrakesh Accords of the Kyoto protocol defined the international trading mechanisms and registries needed to support trading between countries, with allowance trading (sources can buy or sell allowances on the open market. Because the total number of allowances is limited by the cap, emission reductions are assured.)[166] now occurring between European countries and Asian countries. However, while the USA as a nation did not ratify the Protocol, many of its states are now developing cap-and-trade systems and are looking at ways to link their emissions trading systems together, nationally and internationally, to seek out the lowest costs and improve liquidity of the market.[167] However, these states also wish to preserve their individual integrity and unique features. For example, in contrast to the other Kyoto-compliant systems, some states propose other types of greenhouse gas sources, different measurement methods, setting a maximum on the price of allowances, or restricting access to CDM projects. Creating instruments that are not truly fungible would introduce instability and make pricing difficult. Various proposals are being investigated to see how these systems might be linked across markets, with the International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP) as an international body to help co-ordinate this.[167][168]

Business reaction

In 2008, Barclays Capital predicted that the new carbon market would be worth $70 billion worldwide that year.[169] The voluntary offset market, by comparison, is projected to grow to about $4bn by 2010.[170]

23 multinational corporations came together in the G8 Climate Change Roundtable, a business group formed at the January 2005 World Economic Forum. The group included Ford, Toyota, British Airways, BP and Unilever. On June 9, 2005 the Group published a statement stating that there was a need to act on climate change and stressing the importance of market-based solutions. It called on governments to establish "clear, transparent, and consistent price signals" through "creation of a long-term policy framework" that would include all major producers of greenhouse gases.[171] By December 2007 this had grown to encompass 150 global businesses.[172]

Business in the UK have come out strongly in support of emissions trading as a key tool to mitigate climate change, supported by NGOs.[173] However, not all businesses favor a trading approach. On December 11, 2008, Rex Tillerson, the CEO of Exxonmobil, said a carbon tax is "a more direct, more transparent and more effective approach" than a cap-and-trade program, which he said, "inevitably introduces unnecessary cost and complexity". He also said that he hoped that the revenues from a carbon tax would be used to lower other taxes so as to be revenue neutral.[174]

The International Air Transport Association, whose 230 member airlines comprise 93% of all international traffic, position is that trading should be based on "benchmarking", setting emissions levels based on industry averages, rather than "grandfathering", which would use individual companies’ previous emissions levels to set their future permit allowances. They argue grandfathering "would penalise airlines that took early action to modernise their fleets, while a benchmarking approach, if designed properly, would reward more efficient operations".[175]

Measuring, reporting, verification (MRV)

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2009) |

MRV system holds a role of producing credible information under emissions trading scheme. MRV system verifies accuracy of data on emissions (they are consistently monitored(M),reported(R) to the regulators, and verified(V)).[176]

An emissions trading system requires measurements at the level of operator or installation. These measurements are then reported to a regulator. For greenhouse gases all trading countries maintain an inventory of emissions at national and installation level; in addition, the trading groups within North America maintain inventories at the state level through The Climate Registry. For trading between regions these inventories must be consistent, with equivalent units and measurement techniques.[177]

In some industrial processes emissions can be physically measured by inserting sensors and flowmeters in chimneys and stacks, but many types of activity rely on theoretical calculations for measurement. Depending on local legislation, these measurements may require additional checks and verification by government or third party auditors, prior or post submission to the local regulator.

Enforcement

Another significant, yet troublesome aspect is enforcement.[178] Without effective MRV and enforcement the value of allowances is diminished. Enforcement can be done using several means, including fines or sanctioning those that have exceeded their allowances. Concerns include the cost of MRV and enforcement and the risk that facilities may be tempted to mislead rather than make real reductions or make up their shortfall by purchasing allowances or offsets from another entity. The net effect of a corrupt reporting system or poorly managed or financed regulator may be a discount on emission costs, and a (hidden) increase in actual emissions.

According to Nordhaus (2007, p. 27), strict enforcement of the Kyoto Protocol is likely to be observed in those countries and industries covered by the EU ETS.[179] Ellerman and Buchner (2007, p. 71) commented on the European Commission's (EC's) role in enforcing scarcity of permits within the EU ETS.[180] This was done by the EC's reviewing the total number of permits that member states proposed that their industries be allocated. Based on institutional and enforcement considerations, Kruger et al. (2007, pp. 130–131) suggested that emissions trading within developing countries might not be a realistic goal in the near-term.[181] Burniaux et al.. (2008, p. 56) argued that due to the difficulty in enforcing international rules against sovereign states, development of the carbon market would require negotiation and consensus-building.[182]

Criticism

Emissions trading has been criticised for a variety of reasons.

In the popular science magazine New Scientist, Lohmann (2006) argued that trading pollution allowances should be avoided as a climate change policy. Lohmann gave several reasons for this view. First, global warming will require more radical change than the modest changes driven by previous pollution trading schemes such as the US SO2 market. Global warming requires "nothing less than a reorganisation of society and technology that will leave most remaining fossil fuels safely underground." Carbon trading schemes have tended to reward the heaviest polluters with 'windfall profits' when they are granted enough carbon credits to match historic production. Carbon trading encourages business-as-usual as expensive long-term structural changes will not be made if there is a cheaper source of carbon credits. Cheap "offset" carbon credits are frequently available from the less developed countries, where they may be generated by local polluters at the expense of local communities.[183]

Lohmann (2006b) supported conventional regulation, green taxes, and energy policies that are "justice-based" and "community-driven."[184] According to Carbon Trade Watch (2009), carbon trading has had a "disastrous track record." The effectiveness of the EU ETS was criticized, and it was argued that the CDM had routinely favoured "environmentally ineffective and socially unjust projects."[185]

Annie Leonard provided a critical view on carbon emissions trading in her 2009 documentary The Story of Cap and Trade. This documentary emphasized three factors: unjust financial advantages to major pollutors resulting from free permits, an ineffectiveness of the system caused by cheating in connection with carbon offsets and a distraction from the search for other solutions.[186]

Offsets

Forest campaigner Jutta Kill (2006) of European environmental group FERN argued that offsets for emission reductions were not substitute for actual cuts in emissions. Kill stated that "[carbon] in trees is temporary: Trees can easily release carbon into the atmosphere through fire, disease, climatic changes, natural decay and timber harvesting."[187]

Supply of permits

Regulatory agencies run the risk of issuing too many emission credits, which can result in a very low price on emission permits (CCC, 2008, p. 140).[125] This reduces the incentive that permit-liable firms have to cut back their emissions. On the other hand, issuing too few permits can result in an excessively high permit price (Hepburn, 2006, p. 239).[188] This is one of the arguments in favour of a hybrid instrument, that has a price-floor, i.e., a minimum permit price, and a price-ceiling, i.e., a limit on the permit price. A price-ceiling (safety value) does, however, remove the certainty of a particular quantity limit of emissions (Bashmakov et al.., 2001).[189]

Incentives

Emissions trading can result in perverse incentives. If, for example, polluting firms are given emission permits for free ("grandfathering"), this may create a reason for them not to cut their emissions. This is because a firm making large cuts in emissions would then potentially be granted fewer emission permits in the future (IMF, 2008, pp. 25–26).[190] This perverse incentive can be alleviated if permits are auctioned, i.e., sold to polluters, rather than giving them the permits for free (Hepburn, 2006, pp. 236–237).[188]

On the other hand, allocating permits can be used as a measure to protect domestic firms who are internationally exposed to competition (p. 237). This happens when domestic firms compete against other firms that are not subject to the same regulation. This argument in favour of allocation of permits has been used in the EU ETS, where industries that have been judged to be internationally exposed, e.g., cement and steel production, have been given permits for free (4CMR, 2008).[191]

Auctioning

Auctioning is a method for distributing emission allowances in a cap-and-trade system whereby allowances are sold to the highest bidder. This method of distribution may be combined with other forms of allowance distribution.[59]

The revenues from auctioning go to the government. These revenues could, for example, be used for research and development of sustainable technology.[192] Alternatively, revenues could be used to cut distortionary taxes, thus improving the efficiency of the overall cap policy (Fisher et al.., 1996, p. 417).[193]

Distributional effects

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO, 2009) examined the potential effects of the American Clean Energy and Security Act on US households.[194] This Act relies heavily on the free allocation of permits. The Bill was found to protect low-income consumers, but it was recommended that the Bill be changed to be more efficient. It was suggested that the Bill be changed to reduce welfare provisions for corporations, and more resources be made available for consumer relief.

Linking

Distinct systems can be linked through the mutual (or unilateral) recognition of emissions allowances for compliance. Linking systems creates a larger carbon market, which can reduce overall compliance costs, increase market liquidity and generate a more stable carbon market.[195][196] Linking systems can also be politically symbolic as it shows willingness to undertake a common effort to reduce GHG emissions.[197] Some scholars have argued that linking may provide a starting point for developing a new, bottom-up international climate policy architecture whereby multiple unique systems successively link their various systems.[198][199] In 2014, California and Québec successfully linked their systems

The International Carbon Action Partnership brings together regional, national and sub-national governments and public authorities from around the world to discuss important issues in the design of emissions trading schemes (ETS) and the way forward to a global carbon market. 30 national and subnational jurisdictions have joined ICAP as members since its establishment in 2007.[200]

See also

- Acid Rain Retirement Fund

- AP 42 Compilation of Air Pollutant Emission Factors

- Asia-Pacific Emissions Trading Forum

- Cap and Dividend

- Cap and Share

- Carbon credit

- Carbon emissions reporting

- Carbon finance

- Carbon offset

- Emission standard

- Energy law

- Flexible Mechanisms

- Green certificate

- Green investment scheme

- Individual and political action on climate change

- Low carbon power generation / Renewable energy

- Low-carbon economy

- Mitigation of global warming

- Mobile Emission Reduction Credit (MERC)

- Personal carbon trading

- Pigovian tax

- Public Smog

- Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation

- Tradable smoking pollution permits

- Verified Carbon Standard

References

- ^ "Climate Change 101: Understanding and Responding to Global Climate Change" (PDF). Cap and Trade. January 2011.

- ^ a b Stavins, Robert N. (November 2001). "Experience with Market-Based Environmental Policy Instruments" (PDF). Discussion Paper 01-58. Washington, D.C.: Resources for the Future. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

Market-based instruments are regulations that encourage behavior through market signals rather than through explicit directives regarding pollution control levels or methods

- ^ "Tax Treaty Issues Related to Emissions Permits/Credits" (PDF). OECD. Retrieved 25 Oct 2014.

- ^ a b http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/prspub/2501441/upload_binary/2501441.pdf;fileType=application/pdf

- ^ a b Montgomery, W.D (December 1972). "Markets in Licenses and Efficient Pollution Control Programs". Journal of Economic Theory. 5: 395–418. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(72)90049-X.

- ^ EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). UK Department of Energy and Climate Change. Retrieved 2009-01-19.