House of Nassau

The House of Nassau is a diversified aristocratic dynasty in Europe. It is named after the lordship associated with Nassau Castle, located in present-day Nassau, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

The lords of Nassau were originally titled "Count of Nassau", then elevated to the princely class as "Princely Counts" (in German: gefürstete Grafen, i.e. Counts who are granted all legal and aristocratic privileges of a Prince).

At the end of the Holy Roman Empire and the Napoleonic Wars, they proclaimed themselves with the permission of the Congress of Vienna "Dukes of Nassau", forming the independent state Nassau (capital city: Wiesbaden), a territory which is at present mainly part of the German Federal State of Hesse (Hessen), and partially of the neighbouring State of Rhineland-Palatinate (Rheinland-Pfalz).

The Duchy was annexed in 1866 after the Austrian-Prussian War as an ally of Austria by Prussia. It was subsequently incorporated into the newly created Prussian Province of Hesse-Nassau.

Today the term Nassau is used in Germany as a name for a geographical, historical and cultural region, but has no longer any political meaning.

All Dutch and Luxembourgish monarchs since 1815 were senior members of the House of Nassau. However, in 1890 (for the Netherlands), respectively in 1912 (for Luxembourg), the male line of heirs to the two thrones became extinct, so that since then they descended in the female line from the House of Nassau.

According to German tradition, the family name is passed on only in the male line of succession. The House would be therefore, from this (German) perspective, extinct since 1985.[1] However, both Dutch and Luxembourgish monarchic traditions, constitutional rules and legislation in that matter differ from the German one, and thus both countries do not consider the House extinct.

The Grand Duke of Luxembourg uses "Duke of Nassau" as his secondary title and a title of pretense to the dignity of Chief of the House of Nassau (being the most senior member of the eldest branch of the House), but not to lay any territorial claims to the former Duchy of Nassau (which is now part of the Federal Republic of Germany).

Origins

Count Dudo-Henry of Laurenburg (ca. 1060 – ca. 1123) is considered the founder of the House of Nassau. He is first mentioned in the purported founding-charter of Maria Laach Abbey in 1093 (although many historians consider the document to be fabricated). The Castle Laurenburg, located a few kilometres upriver from Nassau on the Lahn, was the seat of his lordship. His family probably descended from the Lords of Lipporn. In 1159, Nassau Castle became the ruling seat, and the house is now named after this castle.

-

Laurenburg Castle

The Counts of Laurenburg and Nassau expanded their authority under the brothers Robert (Ruprecht) I (1123–1154) and Arnold I of Laurenburg (1123–1148). Robert was the first person to call himself Count of Nassau, but the title was not confirmed until 1159, five years after Robert's death. Robert's son Walram I (1154–1198) was the first person to be legally titled Count of Nassau.

The chronology of the Counts of Laurenburg is not certain and the link between Robert I and Walram I is especially controversial. Also, some sources consider Gerhard, listed as co-Count of Laurenburg in 1148, to be the son of Robert I's brother, Arnold I.[2] However, Erich Brandenburg in his Die Nachkommen Karls des Großen states that it is most likely that Gerhard was Robert I's son, because Gerard was the name of Beatrix of Limburg's maternal grandfather.[3]

Counts of Laurenburg (ca. 1093–1159)

- ca. 1060 – ca. 1123: Dudo-Henry

- 1123–1154: Robert (Ruprecht) I - son of Dudo-Henry

- 1123–1148: Arnold I - son of Dudo-Henry

- 1148: Gerhard - son (probably) of Robert I

- 1151–1154: Arnold II - son of Robert I

- 1154–1159: Robert II - son of Robert I

Counts of Nassau (1159–1255)

- 1154–1198: Walram I - son of Robert I

- 1158–1167: Henry (Heinrich) I - son of Arnold I, died in Rome during the August 1167 epidemic (after the Battle of Monte Porzio)

- 1160–1191: Robert III, the Bellicose - son of Arnold I

- 1198–1247: Henry II, the Rich - son of Walram I

- 1198–1230: Robert IV - son of Walram I; from 1230–1240: Knight of the Teutonic Order

- 1247–1255: Otto I; from 1255–1289: Count of Nassau in Dillenburg, Hadamar, Siegen, Herborn and Beilstein

- 1249–1255: Walram II; from 1255–1276: Count of Nassau in Wiesbaden, Idstein, and Weilburg

In 1255, Henry II's sons, Walram II and Otto I, split the Nassau possessions. The descendants of Walram became known as the Walram Line, which became important in the Countship of Nassau and Luxembourg. The descendants of Otto became known as the Ottonian Line, which would inherit parts of Nassau, France and the Netherlands. Both lines would often themselves be divided over the next few centuries. In 1783, the heads of various branches of the House of Nassau sealed the Nassau Family Pact (Erbverein) to regulate future succession in their states.

The Walram Line (1255–1985)

Counts of Nassau in Wiesbaden, Idstein, and Weilburg (1255–1344)

- 1255–1276: Walram II

- 1276–1298: Adolf of Nassau, crowned King of Germany in 1292

- 1298–1304: Robert VI of Nassau

- 1298–1324: Walram III, Count of Nassau in Wiesbaden, Idstein, and Weilnau

- 1298–1344: Gerlach I, Count of Nassau in Wiesbaden, Idstein, Weilburg, and Weilnau

After Gerlach's death, the possessions of the Walram line were divided into Nassau-Weilburg and Nassau-Wiesbaden-Idstein.

Nassau-Weilburg (1344–1816)

Count Walram II began the Countship of Nassau-Weilburg, which existed to 1816. The sovereigns of this house afterwards ruled the Duchy of Nassau until 1866 and from 1890 the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. The branch of Nassau-Weilburg ultimately became rulers of Luxembourg. The Walram line received the lordship of Merenberg in 1328 and Saarbrücken (by marriage) in 1353.

-

Weilburg Castle

-

East wing of the castle

Counts of Nassau-Weilburg (1344–1688)

- 1344–1371: John I

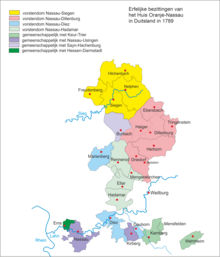

Map of Nassau-Weilburg as of 1789 - 1371–1429: Philipp I of Nassau-Weilburg, and (from 1381) Count of Saarbrücken

- 1429–1492: Philip II

- 1492–1523: Louis I

- 1523–1559: Philip III

- 1559–1593: Albert

- 1559–1602: Philip IV

- 1593–1625: Louis II, Count of Nassau-Weilburg and in Ottweiler, Saarbrücken, Wiesbaden, and Idstein

- 1625–1629: William Louis, John IV and Ernest Casimir

- 1629–1655: Ernest Casimir

- 1655–1675: Frederick

- 1675–1688: John Ernst

Princely counts of Nassau-Weilburg (1688–1816)

- 1688–1719: John Ernst

- 1719–1753: Charles August

- 1753–1788: Charles Christian

- 1788–1816: Frederick William

- 1816: Wilhelm, Prince of Nassau-Weilburg and Duke of Nassau — Nassau-Weilburg merged into Duchy of Nassau

Dukes of Nassau (1816–1866)

In 1866, Prussia annexed the Duchy of Nassau as the duke had been an ally of Austria in the Second Austro-Prussian War. In 1890, Duke Adolf would become Grand Duke Adolphe of Luxembourg.

Grand Dukes of Luxembourg (from the House of Nassau-Weilburg) - 1890–1912 and succession through a female onwards

- 1890–1905: Adolphe

- 1905–1912: William IV

- 1912–1919: Marie-Adélaïde

- 1919–1964: Charlotte

- 1964–2000: Jean

- 2000–present: Henri

-

Berg Castle, Luxembourg

From a morganatic marriage, contracted in 1868, descends a family, see Count of Merenberg, which in 1907 was declared non-dynastic. Had they not been excluded from the succession, they would have inherited the headship of the house in 1912.

Counts of Nassau-Wiesbaden-Idstein (1344–1728)

- 1344–1370: Adolph I

- 1370–after 1386: Gerlach II, Count of Nassau-Wiesbaden

- 1370–1393: Walram IV, Count of Nassau-Idstein; inherited Wiesbaden when Gerlach II died

- 1393–1426: Adolph II

- 1426–1480: John II

- 1480–1509: Philip, Count of Nassau-Idstein

- 1480–1511: Adolf III, Count of Nassau-Wiesbaden; inherited Idstein in 1509

- 1511–1558: Philip I

- 1558–1566: Philip II

- 1566–1568: Balthasar

- 1568–1596: John Louis I

- 1596–1599: John Philip, jointly with his brother John Louis II

- 1596–1605: John Louis II

- 1605–1627: Louis II

- 1627–1629: William Louis

- 1629–1677: John, Count of Nassau-Idstein, and (from 1651) in Wiesbaden, Sonnenberg, Wehen, Burg-Schwalbach and Lahr

- 1677–1721: George August Samuel (1688–1721)

- 1721–1723: Charles Louis

- 1723–1728: Frederick Louis, Count of Nassau-Ottweiler (1680–1728), and in Rixingen (1703–28), and Idstein (1721–1728), and in Wiesbaden, etc. (1723–28)

After Frederick Louis's death, Nassau-Wiesbaden-Idstein fell to Charles, Prince of Nassau-Usingen

-

Idstein Castle

Counts of Nassau-Saarbrücken (1429–1797)

- 1429–1472: John II

- 1472–1545: John Louis I

- 1545–1554: Philip II

- 1554–1574: John III

- 1574–1602: Philip IV, as Philip III of Nassau-Saarbrücken

- 1602–1625: Louis II, Count of Nassau-Saarbrücken and Ottweiler

- 1629–1640: William Louis, Count of Nassau-Saarbrücken and Ottweiler

- 1640–1642: Crato

- 1642–1659: John Louis II, Count of Nassau-Saarbrücken and (1659–80) in Ottweiler, Jungenheim, and Wöllstein

- 1659–1677: Gustav Adolph

- 1677–1713: Louis Crato

- 1713–1723: Charles Louis

- 1723–1728: Frederick Louis

- 1728–1735: Charles

- 1735–1768: William Henry, first Prince of Nassau-Saarbrücken

- 1768–1794: Louis

- 1794–1797: Henry Louis

After Henry Louis's death, Nassau-Saarbrücken fell to Charles William, Prince of Nassau-Usingen

Princes of Nassau-Usingen (1659–1816)

- 1659–1702: Walrad, elevated to Prince

- 1702–1718: William Henry

- 1718–1775: Charles

- 1775–1803: Charles William

- 1803–1816: Frederick Augustus

In 1816, Nassau-Usingen merged with Nassau-Weilburg to form the Duchy of Nassau. See "Dukes of Nassau" above. The princely titles continued to be used, however, evidenced by the carrying of the title Prince of Nassau-Weilburg by the Grand Duke of Luxembourg. Following Frederick Augustus' death, the princely title was adopted (in pretense) by his half brother through an unequal marriage, Karl Philip. As head of the House in 1907, Wilhelm IV declared the Count of Merenberg non-dynastic; by extension, this would indicate that (according to Luxembourgish laws regarding the House of Nassau) this branch would assume the Salic headship of the house in 1965, following the death of the last male Count of Merenberg.[4]

-

Usingen Castle

The Ottonian Line

- 1255–1290: Otto I, Count of Nassau in Siegen, Dillenburg, Beilstein, and Ginsberg

- 1290–1303: Joint rule by Henry, John and Emicho I, sons of Otto I

In 1303, Otto's sons divided the possessions of the Ottonian line. Henry received Nassau-Siegen, John received Nassau-Dillenburg and Emicho I received Nassau-Hadamar. After John's death. Nassau-Dillenburg fell to Henry.

Counts of Nassau-Dillenburg

- 1303–1328: John in Dillenburg, Beilstein and Herborn, and (from 1320) in Katzenelnbogen

- 1328–1343: Henry, from 1303 in Siegen, Ginsberg, Haiger, and the Westerwald, and from 1328 in Dillenburg, Herborn, and Beilstein

- 1343–1350: Otto II

- 1350–1416: John I

- Tetrarchy

- 1416–1420: Adolf

- 1420–1429: John III

- 1420–1442: Engelbert I

- 1420–1443: John II

- 1442–1451: Henry II

- 1448–1475: John IV

- 1475–1504: Engelbert II

- 1504–1516: John V

- 1516–1538: Henry III

- 1538–1559: William I

- 1559–1606: John VI

- 1606–1620: William Louis

- 1620–1623: George

- 1623–1662: Louis Henry, Prince of Nassau-Dillenburg from 1654

- 1662–1701: Henry

- 1701–1724: William II

- 1724–1739: Christian

In 1739, Nassau-Dillenburg fell to Nassau-Dietz, a.k.a. Orange-Nassau.

-

Dillenburg Castle

Counts of Nassau-Beilstein

In 1343, Nassau-Beilstein was split off from Nassau-Dillenburg.

- 1343–1388: Henry I

- 1388–1410: Henry II, jointly with his brother Reinhard

- 1388–1412: Reinhard

- 1412–1473: John I, jointly with his brother Henry III

- 1412–1477: Henry III

- 1473–1499: Henry IV

- 1499–1513: John II

- 1513–1561: John III, jointly with his brother Henry V

- 1513–1525: Henry V

After John III's death, Nassau-Beilstein fell back to Nassau-Dillenburg. It was split off again in 1607 for George, who inherited the rest of Nassau-Dillenburg in 1620.

-

Beilstein Castle

Counts and Princes of Nassau-Hadamar

- 1303–1334: Emicho I, Count in Driedorf, Esterau, and Hadamar, married Anna of Nuremberg

- 1334–1364: John, married Elisabeth of Waldeck

- ?-1412: Elisabeth, daughter of John, Countess of Nassau-Hadamar

- 1334–1359: Emicho II, son of Emicho I, married Anna of Dietz

- 1364–1369: Henry, son of John, Count of Nassau-Hadamar

- 1369–1394: Emicho III, son of John

After Emicho III's death, Nassau-Hadamar fell back to Nassau-Dillenburg.

In 1620, the younger line of Nassau-Hadamar was split off from Nassau-Dillenburg

- 1620–1653: John Louis, son of John VI of Nassau-Dillenburg, Prince from 1650

- 1653–1679: Maurice Henry, son of John Louis

- 1679–1711: Francis Alexander, son of Maurice Henry

In 1711, Nassau-Hadamar was divided between Nassau-Dietz, Nassau-Dillenburg, and Nassau-Siegen.

-

Hadamar Castle

Nassau-Siegen

The branch of Nassau-Siegen was a collateral line of the House of Nassau, and ruled in Siegen. The first Count of Nassau in Siegen was Count Henry, Count of Nassau in Siegen (d. 1343), the elder son of Count Otto I of Nassau. His son Count Otto II of Nassau ruled also in Dillenburg.

- 1303–1343: Henry, Count of Nassau in Siegen, Ginsberg, Haiger, and the Westerwald, and (1328–1343) in Dillenburg, Herborn, and Beilstein

In 1328, John of Nassau-Dillenburg died unmarried and childless, and Dillenburg fell to Henry of Nassau-Siegen. For counts of Nassau-Siegen in between 1343 and 1606, see "Counts of Nassau-Dillenburg" above.

In 1606 the younger line of Nassau-Siegen was split off from the House of Nassau-Dillenburg. After the main line of the House became extinct in 1734, Emperor Charles VI transferred the county to the House of Orange-Nassau.

-

Siegen, Upper Castle

Counts and Princes of Nassau-Siegen

- 1606–1623 John I

- 1623–1638 John II

- 1638–1674 George Frederick

- 1674–1679 John Maurice

- 1679–1691 William Maurice

- 1691–1699 John Francis Desideratus

- 1699–1707 William Hyacinth

- 1707–1722 Frederick William Adolf

- 1722–1734 Frederick William II

In 1734, Nassau-Siegen fell to Nassau-Dietz, a.k.a. Orange-Nassau.

-

Siegen, Lower Castle

Counts and Princes of Nassau-Dietz

- 1606–1632: Ernst Casimir

- 1632–1640: Henry Casimir I

- 1640–1664: William Frederick, Prince from 1650

- 1664–1696: Henry Casimir II of Nassau-Dietz, Prince of Nassau-Dietz

- 1696–1711: John William Friso, Prince of Nassau-Dietz (after 1702 also Prince of Orange)

-

Diez Castle

-

Oranienstein Castle, Diez

Orange-Nassau

The House of Orange-Nassau stems from the Ottonian Line. The connection was via Engelbert I, who offered his services to the Duke of Burgundy, married a Dutch noblewoman and inherited lands in the Netherlands, with the barony of Breda as the core of his Dutch possessions.

-

Breda Castle

The importance of the Nassaus grew throughout the 15th and 16th century. Henry III of Nassau-Breda was appointed stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht by Emperor Charles V in the beginning of the 16th century. Henry was succeeded by his son, René of Châlon-Orange in 1538, who was, as can be inferred from his name, a Prince of Orange. When René died prematurely on the battlefield in 1544 his possessions and the princely title passed to his cousin, William the Silent, a Count of Nassau-Dillenburg. By dropping the suffix name "Dillenburg" (of the Orange-Nassau-Dillenburg), from then on the family members called themselves "Orange-Nassau."

With the death of William III, the legitimate direct male line of William the Silent became extinct and thereby the first House of Orange-Nassau. John William Friso, the senior agnatic descendant of William the Silent's brother and a cognatic descendant of Frederick Henry, grandfather of William III, inherited the princely title and all the possessions in the low countries and Germany, but not the Principality of Orange itself. The Principality was ceded to France under the Treaty of Utrecht that ended the wars with King Louis XIV. John William Friso, who also was the Prince of Nassau-Dietz, founded thereby the second House of Orange-Nassau (the suffix name "Dietz" was dropped of the combined name Orange-Nassau-Dietz).

After the post-Napoleonic reorganization of Europe, the head of House of Orange-Nassau gained the title "King/Queen of the Netherlands".

Princes of Orange

House of Orange-Nassau(-Dillenburg), first creation

- 1544–1584: William I, also Count of Katzenelnbogen, Vianden, Dietz, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein

- 1584–1618: Philip William, also Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein

- 1618–1625: Maurice, also Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein

- 1625–1647: Frederick Henry, also Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein

- 1647–1650: William II, also Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein

- 1650–1702: William III, also Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam, Lord of IJsselstein and (from 1689) King of England, Scotland, and Ireland

In 1702, the Orange-Nassau-Dillenburg line died out and its possessions fell to the Nassau-Dietz line.

-

Vianden Castle, Luxembourg

House of Orange-Nassau(-Dietz), second creation

- 1702–1711: John William Friso, also Prince of Nassau-Dietz, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein

- 1711–1751: William IV, also Prince of Nassau-Dietz, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein

- 1751–1806: William V, also Prince of Nassau-Dietz, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein

- 1806–1815: William VI, also Prince of Fulda and Count of Corvey, Weingarten and Dortmund; in 1815 became King William I of the Netherlands

Kings and Queens of the Netherlands (from the House of Orange-Nassau-Dietz)

- 1815–1840: William I, also Duke and Grand Duke of Luxemburg and Duke of Limburg

- 1840–1849: William II, also Grand Duke of Luxemburg and Duke of Limburg

- 1849–1890: William III, also Grand Duke of Luxemburg and Duke of Limburg

- 1890–1948: Wilhelmina

Following German laws, the House of Orange-Nassau(-Dietz) has been extinct since the death of Wilhelmina (1962). Dutch laws and the Dutch nation do not consider it extinct.

- 1948–1980: Juliana

- 1980–2013: Beatrix

- 2013-present: Willem-Alexander

-

Noordeinde Palace, Den Haag

-

Huis ten Bosch, Den Haag

Family Tree

The following family tree is compiled from Wikipedia and the reference cited in the note[6]

| Dudo-Henry of Laurenburg (German: Dudo-Heinrich) (ca. 1060 – ca. 1123) was Count of Laurenburg in 1093 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Robert I of Nassau (German: Ruprecht) (ca. 1090 – ca. 1154) was from 1123 co-Count of Laurenburg later title himself 1st Count of Nassau | Arnold I of Laurenburg (died ca. 1148) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Robert II (German: Ruprecht) Count of Laurenburg (1154-1158)(died ca. 1159) | Walram I of Nassau (French: Valéran) (ca. 1146–1198) was the first (legally titled) Count of Nassau (1154-1198) | Henry (Heinrich) I co-Count of Nassau (1160 - August 1167) | Robert III, the Bellicose German: Ruprecht der Streitbare (died 1191) co-Count of Nassau (1160-1191) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Henry (Heinrich) II, the Rich Count of Nassau (1180–1251) | Robert (Ruprecht) IV Count of Nassau (1198–1230) Teutonic Knight (1230–1240) | Herrmann (d after 3 December 1240) Canon of Mainz Cathedral | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Walram II of Nassau (ca. 1220 - 1276) the WALRAMIAN Branch present-day rulers of Luxembourg descend from him | Robert (Ruprecht) V d. before 1247 Teutonic Knight (1230–1240) | Otto I of Nassau (reigned ca. 1247 - 1290) the OTTONIAN branch the present-day rulers of the Netherlands descend from him | John (ca. 1230 - 1309) Bishop-Elect of Utrecht (1267–1290) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adolf (ca. 1255-1298) King of Germany (1292 - 1298) | Henry (d. 1343) Count of Nassau in Siegen | Emich (d. 7 June 1334) Count of Nassau in Hadamar extinct 1394 | John (d. 1328) Count Nassau in Dillenburg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ruprecht (+ 1304) | Gerlach I, Count of Nassau-Wiesbaden (bef 1288 +1361) | Walram III Count of Nassau-Wiesbaden | Otto II (c. 1305 – 1330/1331) Count of Nassau-Dillenburg | Henry (1307-1388) Count of Nassau-Beilstein ext. 1561 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adolph (1307 +1370) Count of Nassau in Wiesbaden-Idstein ext 1605 | John I (1309 +1371) Count of Nassau-Weilburg | Rupert 'the Bellicose' (c. 1340 +1390) Count of Nassau-Sonnenberg | John I (1340 +1416) Count of Nassau-Dillenburg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Philip I 1368 +1429) Count of Nassau in Weilburg,Saarbrücken, etc. | Adolph (1362 +1420) Count of Nassau-Dillenburg-Dietz | John II "The Elder" ( +1443) | Engelbert I (c. 1370/80 +1442) Count of Nassau, Baron of Breda founder of the Netherlands Nassaus | John III "The Younger" (+1430) Count of Nassau in Siegen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Philip II (1418 +1492) Count of Nassau-Weilburg | John II (1423 +1472) Count of Nassau-Saarbrücken ext. 1574 | John IV (Jan) (1410, +1475) Count of Nassau-Dillenburg-Dietz | Henry II (1414 +1450) Count of Nassau-Dillenburg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| John III (1441 +1480) Count of Nassau-Weilburg | Philip (1443-1471) Count of Nassau-Weilburg | Engelbert II the Valorious (1451 +1504) Count of Nassau and Vianden, Baron of Breda(fr), Lek, Diest, Roosendaal en Nispen and Wouw | John V (1455 +1516) Count of Nassau in Dillenburg,Siegen,Hadamar,Herborn,Vianden,Dietz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| From here descends the House of Nassau-Weilburg and the Grand Ducal Family of Luxembourg (see below also)' | From here descends the House of Orange-Nassau (see below also) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Orange-Nassau | |

|---|---|

| Royal house | |

| |

Arms of William the Silent | |

| Parent house | House of Nassau |

| Country | Netherlands, United Kingdom, Ireland, Luxembourg, Belgium, France, Germany, Orange, Nassau |

| Etymology | Orange, France & Nassau, Germany |

| Founded | 15 July 1544 |

| Founder | William the Silent |

| Current head | King Willem-Alexander |

| Titles | List

|

| Estate(s) | Netherlands |

| Dissolution | 28 November 1962 (in agnatic line, following the death of Wilhelmina of the Netherlands) |

The House of Orange-Nassau (Dutch: Huis van Oranje-Nassau, pronounced [ˈɦœys fɑn oːˌrɑɲə ˈnɑsʌu])[a] is the current reigning house of the Netherlands. A branch of the European House of Nassau, the house has played a central role in the politics and government of the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe, particularly since William the Silent organised the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule, which after the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) led to an independent Dutch state. William III of Orange led the resistance of the Netherlands and Europe to Louis XIV of France and orchestrated the Glorious Revolution in England that established parliamentary rule. Similarly, Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands was instrumental in the Dutch resistance during World War II.

Several members of the house served during the Eighty Years war and after as stadtholder ("governor"; Dutch: stadhouder) during the Dutch Republic. However, in 1815, after a long period as a republic, the Netherlands became a monarchy under the House of Orange-Nassau.

The dynasty was established as a result of the marriage of Henry III of Nassau-Breda from Germany and Claudia of Châlon-Orange from French Burgundy in 1515. Their son René of Chalon inherited in 1530 the independent and sovereign Principality of Orange from his mother's brother, Philibert of Châlon. As the first Nassau to be the Prince of Orange, René could have used "Orange-Nassau" as his new family name. However, his uncle, in his will, had stipulated that René should continue the use of the name Châlon-Orange. After René's death in 1544, his cousin William of Nassau-Dillenburg inherited all of his lands. This "William I of Orange", in English better known as William the Silent, became the founder of the House of Orange-Nassau.[7]: 10

Origins

Nassau Castle was founded around 1100 by Dudo, Count of Laurenburg, the founder of the House of Nassau. In 1120, Dudo's sons and successors, Counts Rupert I and Arnold I, established themselves at Nassau Castle, taking for themselves the title "Count of Nassau". In 1255 the Nassau possessions were split between Walram and Otto, the sons of Count Henry II. The descendants of Walram were known as the Walram Line, and they became Dukes of Nassau and, in 1890, Grand Dukes of Luxembourg. This line also included Adolph of Nassau, who was elected King of the Romans in 1292. The descendants of Otto became known as the Ottonian Line, and they inherited parts of the County of Nassau, as well as properties in France and the Netherlands.[citation needed]

The House of Orange-Nassau stems from the younger Ottonian Line. The first of this line to establish himself in the Netherlands was John I, Count of Nassau-Siegen, who married Margaret of the Mark. The real founder of the Nassau fortunes in the Netherlands was John's son, Engelbert I. He became counsellor to the Burgundian Dukes of Brabant, first to Anton of Burgundy, and later to his son Jan IV of Brabant. He also would later serve Philip the Good. In 1403, he married the Dutch noblewoman Johanna van Polanen and so inherited lands in the Netherlands, with the Barony of Breda as the core of the Dutch possessions and the family fortune.[8]: 35

A nobleman's power was often based on his ownership of vast tracts of land and lucrative offices. It also helped that much of the lands that the House of Orange-Nassau controlled sat under one of the commercial and mercantile centres of the world (see below under Lands and Titles). The importance of the family grew throughout the 15th and 16th centuries as they became councilors, generals and stadholders of the Habsburgs (see armorial of the great nobles of the Burgundian Netherlands and list of knights of the Golden Fleece). Engelbert II of Nassau served Charles the Bold and Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, who had married Charles's daughter Mary of Burgundy. In 1496, he was appointed stadtholder of Flanders and by 1498 he had been named President of the Grand Conseil. In 1501, Maximilian named him Lieutenant-General of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands. From that point forward (until his death in 1504), Engelbert was the principal representative of the Habsburg Empire to the region. Hendrik III of Nassau-Breda was appointed stadtholder of Holland and Zeeland by Charles of Ghent in the beginning of the 16th century. Hendrik was succeeded by his son René of Chalon in 1538, who had inherited the title of Prince of Orange and the principality of that name from his maternal uncle Philibert of Chalon. In 1544, René died in battle aged 25. His possessions, including the principality and title, passed by his will as sovereign prince to his paternal cousin, William I of Orange. From then on, the family members called themselves "Orange-Nassau."[7]: 8 [8]: 37 [9]: vol3, pp3-4 [10]: 37, 107, 139

Eighty Years' War

Although Charles V pretended to resist the Protestant Reformation, he ruled the Dutch territories wisely with moderation and regard for local customs, and he did not persecute his Protestant subjects on a large scale. His son Philip II inherited his antipathy for the Protestants but not his moderation. Under the reign of Philip, a true persecution of Protestants was initiated and taxes were raised to an outrageous level. Discontent arose and William of Orange (with his vague Lutheran childhood) stood up for the Protestant (mainly Calvinist) inhabitants of the Netherlands. Things went badly after the Eighty Years' War started in 1568, but luck turned to his advantage when Protestant rebels attacking from the North Sea captured Brielle, a coastal town in present-day South Holland in 1572. Many cities in Holland began to support William. During the 1570s he had to defend his core territories in Holland several times, but in the 1580s the inland cities in Holland were secure. William of Orange was considered a threat to Spanish rule in the area and was assassinated in 1584 by a hired killer sent by Philip.[9]: vol3, p177 [10]: 216 [11]

William was succeeded by his second son Maurits, a Protestant who proved an excellent military commander. His abilities as a commander and the lack of strong leadership in Spain after the death of Philip II (1598) gave Maurits excellent opportunities to conquer large parts of the present-day Dutch territory.[9]: vol 3, pp243-253 [12] In 1585 Maurits was elected stadtholder of the provinces of Holland and Zealand as his father's successor and as a counterpose to Elizabeth's delegate, the Earl of Leicester. In 1587 he was appointed captain-general (military commander-in-chief) of the armies of the Dutch Republic. In the early years of the 17th century there arose quarrels between stadtholder and oligarchist regents—a group of powerful merchants led by Johan van Oldebarnevelt—because Maurits wanted more powers in the Republic. Maurits won this power struggle by arranging the judicial murder of Oldebarnevelt.[10]: 421–432, 459 [12]

17th century

Expansion of dynastic power

Maurice died unmarried in 1625 and left no legitimate children. He was succeeded by his half-brother Frederick Henry (Dutch: Frederik Hendrik), youngest son of William I. Maurits urged his successor on his deathbed to marry as soon as possible. A few weeks after Maurits's death, he married Amalia van Solms-Braunfels. Frederick Henry and Amalia were the parents of a son and several daughters. These daughters were married to important noble houses such as the house of Hohenzollern, but also to the Frisian Nassaus, who were stadtholders in Friesland. His only son, William, married Mary, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange, the eldest daughter of Charles I of England. These dynastic moves were the work of Amalia.[7]: 72–74 [13]: 61

Exile and resurgence

Frederick Henry died in 1647 and his son succeeded him. As the Treaty of Munster was about to be signed, thereby ending the Eighty Years' War, William tried to maintain the powers he had in wartime as military commander. These would necessarily be diminished in peacetime as the army would be reduced, along with his income. This met with great opposition from the regents. When Andries Bicker and Cornelis de Graeff, the great regents of the city of Amsterdam refused some mayors he appointed, he besieged Amsterdam. The siege provoked the wrath of the regents. William died of smallpox on November 6, 1650, leaving only a posthumous son, William III (*November 14, 1650). Since the Prince of Orange upon the death of William II, William III, was an infant, the regents used this opportunity to leave the stadtholdership vacant. This inaugurated the era in Dutch history that is known as the First Stadtholderless Period.[14] A quarrel about the education of the young prince arose between his mother and his grandmother Amalia (who outlived her husband by 28 years). Amalia wanted an education which was pointed at the resurgence of the House of Orange to power, but Mary wanted a pure English education. The Estates of Holland, under Jan de Witt and Cornelis de Graeff, meddled in the education and made William a "child of state" to be educated by the state. The doctrine used in this education was keeping William from the throne. William became indeed very docile to the wishes of the regents and the Estates.[13][14]

The Dutch Republic was attacked by France and England in 1672. The military function of stadtholder was no longer superfluous, and with the support of the Orangists, William was restored, and he became the stadtholder. William successfully repelled the invasion and seized royal power. He became more powerful than his predecessors from the Eighty Years' War.[13][14] In 1677, William married his cousin Mary Stuart, the daughter of the future king James II of England. In 1688, William embarked on a mission to depose his Catholic father-in-law from the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland. He and his wife were crowned the King and Queen of England on April 11, 1689. With the accession to the thrones of the three kingdoms, he became one of the most powerful sovereigns in Europe, and the only one to defeat Louis XIV of France.[13] William III died childless after a riding accident on March 8, 1702, leaving the main male line of the House of Orange extinct, and leaving Scotland, England and Ireland to his sister-in-law Queen Anne.

Position in the Dutch Republic in the 17th century

The house of Orange-Nassau was relatively unlucky in establishing a hereditary dynasty in an age that favoured hereditary rule. The Stuarts and the Bourbons came to power at the same time as the Oranges, the Vasas and Oldenburgs were able to establish a hereditary kingship in Sweden and Denmark, and the Hohenzollerns were able to set themselves on a course to the rule of Germany. The House of Orange was no less gifted than those houses, in fact, some might argue more so, as their ranks included some the foremost statesmen and captains of the time. A 104 years separated the death of William the Silent from the accession of his great-grandson, William III, as King of England. Although the institutions of the United Provinces became more republican and entrenched as time went on, William the Silent had been offered the countship of Holland and Zealand, and only his assassination prevented his accession to those offices. This fact did not go unforgotten by his successors.[7]: 28–31, 64, 71, 93, 139–141

The Prince of Orange was also not just another noble among equals in the Netherlands. First, he was the traditional leader of the nation in war and in rebellion against Spain. He was uniquely able to transcend the local issues of the cities, towns and provinces. He was also a sovereign ruler in his own right (see Prince of Orange article). This gave him a great deal of prestige, even in a republic. He was the center of a real court like the Stuarts and Bourbons, French speaking, and extravagant to a scale. It was natural for foreign ambassadors and dignitaries to present themselves to him and consult with him as well as to the States General to which they were officially credited. The marriage policy of the princes, allying themselves twice with the Royal Stuarts, also gave them acceptance into the royal caste of rulers.[15]: 76–77, 80

Besides showing the relationships among the family, the family tree below also points out an extraordinary run of bad luck. In the 211 years from the death of William the Silent to the conquest by France, there was only one time that a son directly succeeded his father as Prince of Orange, Stadholder and Captain-General without a minority (William II). When the Oranges were in power, they also tended to settle for the actualities of power, rather than the appearances, which increasingly tended to upset the ruling regents of the towns and cities. On being offered the dukedom of Gelderland by the States of that province, William III let the offer lapse as liable to raise too much opposition in the other provinces.[15]: 75–83

-

The collateral house of Nassau: the four brothers of Willem I, prince of Orange: Jan (1536–1606), sitting, Hendrik (1550–1574), Adolf (1540–1568) and Lodewijk (1538–1574), counts of Nassau.

-

"The Nassau Cavalcade", members of the House of Orange-Nassau on parade in 1621 from an engraving by Willem Delff. From left to right in the first row: Prince Maurice, Prince Philip William and Prince Frederick Henry, between Maurice and Frederick Henry is William Louis, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg.[16]

-

Princes of the collateral House of Nassau-Dietz from the Stadhouderlijk Hof (nowadays called Princessehof Ceramics Museum) in Leeuwarden, H.Prince of Nassau, Henry Casimir, Prince of Nassau, George, Prince of Nassau, and Willem Frederick, Prince of Nassau_Dietz

The house of Orange was also related by marriage to several of these key European dynasties of the time, Stuart, Bourbon, and Palatine, Hannover and Hohenzollern. These alliances had consequences for all of them. William III used his double relationship with the Stuarts to justify his co-equal status with his wife on the English throne after the Glorious Revolution. As an arrière petit fils de France, albeit in the female line, he felt doubly insulted by his cousin Louis XIV's occupation and seizure of his sovereign principality of Orange. His death without children of his own ensured the passing of Orange to a Dutch cousin and years of squabbles over the same, while securing the British throne to the more distantly related House of Hanover.

18th century

Second Stadtholderless period

The regents found that they had suffered under the powerful leadership of William III as the ruler of the Netherlands and king in the British Isles and they left the stadtholdership vacant for the second time. As William III died childless in 1702 the principality became a matter of dispute between Prince John William Friso of Nassau-Dietz of the Frisian Nassaus and King Frederick I of Prussia, who both claimed the title Prince of Orange. Both descended from Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange. The King of Prussia was his grandson through his mother, Countess Luise Henriette of Nassau. Frederick Henry in his will had appointed this line as successor in case the main House of Orange-Nassau were to die out. John William Friso was a great-grandson of Frederick Henry (through Countess Albertine Agnes of Nassau, another daughter) and was appointed heir in William III's will. The principality was captured by the forces of King Louis XIV of France under François Adhémar de Monteil, Count of Grignan, in the Franco-Dutch War in 1672, and again in August 1682. With the Treaty of Utrecht that ended the wars of Louis XIV, the territory was formally ceded to France by Frederick I in 1713.[8]: 1 John William Friso drowned in 1711 in the Hollands Diep near Moerdijk, and he left his posthumously born son William IV, Prince of Orange. That son succeeded at that time his father as stadtholder in Friesland (as the stadtholdership had been hereditary in that province since 1664), and Groningen. William IV was proclaimed the stadtholder of Guelders, Overijssel, and Utrecht in 1722. When the French invaded Holland in 1747, William IV was appointed stadtholder in Holland and Zeeland as well in the Orangist revolution. The position of stadtholder was made hereditary in both the male and the female lines in all provinces at the same time.[7]: 148–151, 170

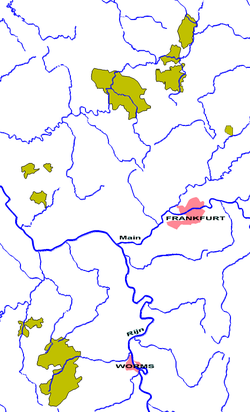

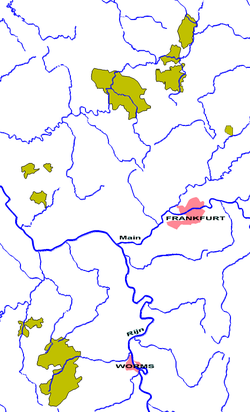

Hereditary territories in Germany

After the Nassau-Dietz branch took over, the House of Orange-Nassau had acquired the following territories by the end of the 18th century in the Holy Roman Empire, located in present-day Germany:[citation needed]

- County of Nassau-Dillenburg, elevated to principality in 1654

- County of Nassau-Siegen, elevated to principality

- County of Nassau-Dietz, elevated to principality

- County of Nassau-Hadamar, elevated to principality

- Fief Beilstein

- Fief Spiegelberg

- Amt Nassau (shared with Nassau-Usingen)

- Amt Kirrberg (shared with Nassau-Usingen)

- Grund Seel and Burbach (shared with Nassau-Weilburg)

- Amt Camberg (shared with the Electorate of Trier)

- Amt Wehrheim (shared with the Electorate of Trier)

- Ems custody (shared with Hesse-Darmstadt)

Around 1742, William IV of Orange established the Hochdeutsche Hofdepartement, an administrative centre located in The Hague inside the Dutch Republic, which looked after the family's possessions in Germany.[17]

End of the stadtholdership

William IV died in 1751, leaving his three-year-old son, William V, as the stadtholder. Since William V was still a minor, the regents reigned for him. He grew up to be an indecisive person, a character defect which would come to haunt William V his whole life. His marriage to Wilhelmina of Prussia relieved this defect to some degree. In 1787, Willem V survived an attempt to depose him by the Patriots (anti-Orangist revolutionaries) after the Kingdom of Prussia intervened. When the French invaded Holland in 1795, William V was forced into exile, and he was never to return alive to Holland.[7]: 228–229 [9]: vol5, 289

After 1795, the House of Orange-Nassau faced a difficult period, surviving in exile at other European courts, especially those of Prussia and Britain. Following the recognition of the Batavian Republic by the 1801 Oranienstein Letters, William V's son William VI renounced the stadtholdership in 1802. In return, he received a few territories like the Free Imperial City of Dortmund, Corvey Abbey and Diocese of Fulda from First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte of the French Republic (Treaty of Amiens), which was established as the Principality of Nassau-Orange-Fulda.[18] William V died in 1806.[19]

Monarchy since 1813

| Dutch royalty House of Orange-Nassau |

|---|

|

| King William I |

| King William II |

| King William III |

| Queen Wilhelmina |

| Queen Juliana |

| Queen Beatrix |

| King Willem-Alexander |

United Kingdom of the Netherlands

After a repressed Dutch rebel action, Prussian and Cossack troops drove out the French in 1813, with the support of the Patriots of 1785. A provisional government was formed, most of whose members had helped drive out William V 18 years earlier. However, they were realistic enough to accept that any new government would have to be headed by William V's son, William Frederick (William VI). All agreed that it would be better in the long term for the Dutch to restore William themselves rather than have him imposed by the allies.[7]: 230

At the invitation of the provisional government, William Frederick returned to the Netherlands on November 30. This move was strongly supported by the United Kingdom, which sought ways to strengthen the Netherlands and deny future French aggressors easy access to the Low Countries' Channel ports. The provisional government offered William the crown. He refused, believing that a stadholdership would give him more power. Thus, on December 6, William proclaimed himself hereditary sovereign prince of the Netherlands—something between a kingship and a stadholdership. In 1814, he was awarded sovereignty over the Austrian Netherlands and the Prince-Bishopric of Liège as well. On March 15, 1815, with the support of the powers gathered at the Congress of Vienna, William proclaimed himself King William I. He was also made grand duke of Luxembourg, and (to assuage French sensitivity by distancing the title from the now-defunct principality) the title 'Prince of Orange' was changed to 'Prince of Oranje'.[20] The two countries remained separate, though they shared a common monarch via a personal union. William had thus fulfilled the House of Orange's three-century quest to unite the Low Countries.[9]: vol5, 398

The institution of the monarch in the Netherlands is considered an office under the Constitution of the Netherlands.[21] There are none of the religious connotations to the office as in some other monarchies.[citation needed] A Dutch sovereign is inaugurated rather than crowned in a coronation ceremony.[citation needed] It was initially more of a crowned/hereditary presidency, and a continuation of the status quo ante of the pre-1795 hereditary stadholderate in the Republic.[citation needed] In practice, the current monarch has considerably less power than the stadtholder.[citation needed]

As king of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, William tried to establish one common culture. This provoked resistance in the southern parts of the country, which had been culturally separate from the north since 1581. He was considered an enlightened despot.[9]: vol5, 399

The Prince of Orange held rights to Nassau lands (Dillenburg, Dietz, Beilstein, Hadamar, Siegen) in central Germany. On the other hand, the King of Prussia, Frederick William III—brother-in-law and first cousin of William I, had beginning from 1813 managed to establish his rule in Luxembourg, which he regarded as his inheritance from Anne, Duchess of Luxembourg who had died over three centuries earlier. At the Congress of Vienna, the two brothers-in-law agreed to a trade—Frederick William received William I's ancestral lands while William I received Luxembourg. Both got what was geographically nearer to their centre of power.[9]: vol5, 392

In 1830, most of the southern portion of William's realm—the former Austrian Netherlands and Prince-Bishopric—declared independence as Belgium. William fought a disastrous war until 1839 when he was forced to settle for peace. With his realm halved, he decided to abdicate in 1840 in favour of his son, William II. Although William II shared his father's conservative inclinations, in 1848 he accepted an amended constitution that significantly curbed his own authority and transferred the real power to the States General. He took this step to prevent the Revolutions of 1848 from spreading to his country.[9]: vol5, 455–463

William III and the risk of extinction

William II died in 1849. He was succeeded by his son, William III. A rather conservative, even reactionary man, William III was sharply opposed to the new 1848 constitution. He continually tried to form governments that were dependent on his support, even though it was prohibitively difficult for a government to stay in office against the will of Parliament. In 1868, he tried to sell Luxembourg to France, which was the source of a quarrel between Prussia and France.[9]: vol5, 483

William III had a rather unhappy marriage with Sophie of Württemberg, and his heirs died young. This raised the possibility of the extinction of the House of Orange-Nassau. After the death of Queen Sophie in 1877, William remarried to 20-year-old Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont in 1879; he was 41 years older than her. On 31 August 1880, Queen Emma gave birth to their daughter and the royal heiress, Wilhelmina.[9]: vol5, 497–498 There were considerably more concerns over the royal dynasty's future, when Wilhelmina's marriage with Duke Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (since 1901) repeatedly resulted in miscarriages. Had the House of Orange died out, the throne would likely have passed to Prince Heinrich XXXII Reuss of Köstritz, leading the Netherlands into an undesirably strong influence from the German Empire that would threaten Dutch independence.[22] Not just Socialists, but now also Anti-Revolutionary politicians including Prime Minister Abraham Kuyper and Liberals such as Samuel van Houten advocated the restoration of the Republic in Parliament in case the marriage remained childless.[23] The birth of Princess Juliana in 1909 put the question to rest.[23]

Monarchy in modern times

Wilhelmina was queen of the Netherlands for 58 years, from 1890 to 1948. Because she was only 10 years old in 1890, her mother, Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont, was the regent until Wilhelmina's 18th birthday in 1898. Since females were not allowed to hold power in Luxembourg, due to Salic law, Luxembourg passed to the House of Nassau-Weilburg, a collateral line to the House of Orange-Nassau. For a time, it appeared that the Dutch royal family would die with Wilhelmina. Her half-brother, Prince Alexander, had died in 1884, and no royal babies were born from then until Wilhelmina gave birth to her only child, Juliana, in 1909. The Dutch royal house remained quite small until the later 1930s and the early 1940s, during which time Juliana gave birth to four daughters. Although the House of Orange died out in its male line with the death of Queen Wilhelmina, it continued in the female line as can be seen in other modern European monarchies, the name "Orange" continues to be used by the Dutch royalty[9]: vol5, 507–508 and as evidenced in many patriotic songs, such as "Oranje boven".[citation needed]

The Netherlands remained neutral in World War I, during her reign, and the country was not invaded by Germany, as neighbouring Belgium was.[24]

Nevertheless, Queen Wilhelmina became a symbol of the Dutch resistance during World War II. The moral authority of the Monarchy was restored because of her rule. After 58 years on the throne as the Queen, Wilhelmina decided to abdicate in favour of her daughter, Juliana. Juliana had the reputation of making the monarchy less "aloof", and under her reign the Monarchy became known as the "cycling monarchy". Members of the royal family were often seen riding bicycles through the cities and the countryside under Juliana.[24]

A royal marriage controversy occurred in 1966 when Juliana's eldest daughter, the future Queen Beatrix, decided to marry Claus von Amsberg, a German diplomat. The marriage of a member of the royal family to a German was quite controversial in the Netherlands, which had suffered under Nazi German occupation in 1940–45. This reluctance to accept a German consort probably was exacerbated by von Amsberg's former membership in the Hitler Youth under the Nazi regime in his native country, and also his following service in the German Wehrmacht. Beatrix needed permission from the government to marry anyone if she wanted to remain heiress to the throne, but after some argument, it was granted. As the years went by, Prince Claus was fully accepted by the Dutch people. In time, he became one of the most popular members of the Dutch monarchy, and his death in 2002 was widely mourned.[24]

On April 30, 1980, Queen Juliana abdicated in favour of her daughter, Beatrix. In the early years of the twenty-first century, the Dutch monarchy remained popular with a large part of the population. Beatrix's eldest son, Willem-Alexander, was born on April 27, 1967; the first immediate male heir to the Dutch throne since the death of his great-granduncle, Prince Alexander, in 1884. Willem-Alexander married Máxima Zorreguieta, an Argentine banker, in 2002; the first commoner ever to marry an heir apparent to the Dutch throne. They are parents of three daughters: Catharina-Amalia, Alexia, and Ariane. After a long struggle with neurological illness, Queen Juliana died on March 20, 2004, and her husband, Prince Bernhard, died on December 1 of that same year.[24]

Upon Beatrix's abdication on April 30, 2013, the Prince of Orange was inaugurated as King Willem-Alexander, becoming the Netherlands' first male ruler since 1890. His eldest daughter, Catharina-Amalia, as heiress apparent to the throne, became Princess of Orange in her own right.[24]

Net worth

Unlike other royal houses, there has always been a separation in the Netherlands between what was owned by the state and used by the House of Orange in their offices as monarch, or previously, stadtholder, and the personal investments and fortune of the House of Orange.[citation needed]

As monarch, the King or Queen has use of, but not ownership of, the Huis ten Bosch as a residence and Noordeinde Palace as a work palace. In addition, the Royal Palace of Amsterdam is also at the disposal of the monarch (although it is only used for state visits and is open to the public when not in use for that purpose). Soestdijk Palace was sold to private investors in 2017. The crown jewels, comprising the crown, orb and sceptre, Sword of State, royal banner, and ermine mantle have been placed in the Crown Property Trust. The trust also holds the items used on ceremonial occasions, such as the carriages, table silver, and dinner services.[25] The Royal House is also exempt from income, inheritance, and personal tax.[26][27]

The House of Orange has long had the reputation of being one of the wealthier royal houses in the world, largely due to their business investments in Royal Dutch Shell, Philips electronics company, KLM-Royal Dutch Airlines, and the Holland-America Line. How significant these investments are is a matter of conjecture, as their private finances, unlike their public stipends as monarch, are not open to public scrutiny.[28]

As late as 2001, the fortune of the Royal Family was estimated by various sources (Forbes magazine) at $3.2 billion. Most of the wealth was reported to come from the family's longstanding stake in the Royal Dutch/Shell Group. At one time, the Oranges reportedly owned as much as 25% of the oil company; their stake is in 2001 was estimated at a minimum of 2%, worth $2.7 billion on the May 21 cutoff date for the Billionaires issue. The family also was estimated to have a 1% stake in financial services firm ABN-AMRO.[29][30]

The royal family's fortune seems to have been hit by declines in real estate and equities after 2008. They were also rumored to have lost up to $100 million when Bernard Madoff's Ponzi scheme collapsed, though the royal house denies the allegations.[31] In 2009, Forbes estimated Queen Beatrix's wealth at US$300 million.[32] This could also have been due to splitting the fortune between Queen Beatrix and her 3 sisters, as there is no right of the eldest to inherit the whole property. A surge in export revenue, recovery in real estate and strong stock market have helped steady the royal family's fortunes, but uncertainty over the new government and future austerity measures needed to bring budget deficits in line may dampen future prospects. In July 2010, Forbes magazine estimated her net worth at $200 million[28] This estimate was unchanged in April 2011.[33]

List of rulers

Stadtholderate under the House of Orange-Nassau

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

William I

| 24 April 1533 – 10 July 1584 (aged 51) | 1559 | 1584 | Stadtholder[34] | Orange-Nassau |  |

Maurice

| 14 November 1567 – 23 April 1625 (aged 57) | 1585 | 1625 | Stadtholder,[35] son of William I | Orange-Nassau |  |

Frederick Henry

| 29 January 1584 – 14 March 1647 (aged 63) | 1625 | 1647 | Stadtholder,[36] son of William I | Orange-Nassau |  |

William II

| 27 May 1626 – 6 November 1650 (aged 24) | 14 March 1647 | 6 November 1650 | Stadtholder,[37] son of Frederick Henry | Orange-Nassau |  |

William III

| 4 November 1650 – 8 March 1702 (aged 51) | 4 July 1672 | 8 March 1702 | Stadtholder,[38] son of William II[39] | Orange-Nassau |  |

William IV

| 1 September 1711 – 22 October 1751 (aged 40) | 1 September 1711 (under the regency of Marie Louise until 1731) | 22 October 1751 | Hereditary Stadtholder of the United Netherlands,[40] son of John William Friso | Orange-Nassau |  |

William V

| 8 March 1748 – 9 April 1806 (aged 58) | 22 October 1751 | 9 April 1806 | Hereditary Stadtholder of the United Netherlands, son of William IV, succeeded by his son King William I (-> Principality of the Netherlands (1813–1815) | Orange-Nassau |  |

Stadtholderate under the Houses of Nassau-Dillenburg and Nassau-Dietz

Note:[41]

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

John VI

| 22 November 1536 – 8 October 1606 (aged 69) | 1578 | 1581 | Stadtholder,[42] brother of William I | Nassau-Dillenburg |  |

William Louis

| 13 March 1560 – 31 May 1620 (aged 60) | 1584 | 1620 | Stadtholder,[43] son of John VI | Nassau-Dillenburg |  |

| Ernest Casimir I | 22 December 1573 – 2 June 1632 (aged 58) | 1620 | 1632 | Stadtholder,[44] son of John VI | Nassau |  |

| Henry Casimir I | 21 January 1612 – 13 July 1640 (aged 28) | 1632 | 1640 | Stadtholder,[45] son of Ernest Casimir I | Nassau-Dietz |  |

| William Frederick | 7 August 1613 – 31 October 1664 (aged 51) | 1640 | 1664 | Stadtholder,[46] son of Ernest Casimir I | Nassau |  |

| Henry Casimir II | 18 January 1657 – 25 March 1696 (aged 39) | 18 January 1664 | 25 March 1696 | Hereditary Stadtholder,[47] son of William Frederick | Nassau-Dietz |  |

| John William Friso | 4 August 1687 – 14 July 1711 (aged 23) | 25 March 1696 | 14 July 1711 | Hereditary Stadtholder,[48] son of Henry Casimir II, succeeded by his son William IV of Orange-Nassau, Hereditary Stadtholder of the United Netherlands (-> Stadtholderate under the House of Orange-Nassau | Nassau-Dietz, Orange-Nassau |  |

Principality of the Netherlands (1813–1815)

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William I | 24 August 1772 – 12 December 1843 (aged 71) | 6 December 1813 | 16 March 1815 | Raised Netherlands to status of kingdom in 1815, son of Stadtholder William V | Orange-Nassau |  |

Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815–present)

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William I | 24 August 1772 – 12 December 1843 (aged 71) | 16 March 1815 | 7 October 1840 | Son of the last Stadtholder William V | Orange-Nassau |  |

| William II | 6 December 1792 – 17 March 1849 (aged 56) | 7 October 1840 | 17 March 1849 | Son of William I | Orange-Nassau |  |

| William III | 17 February 1817 – 23 November 1890 (aged 73) | 17 March 1849 | 23 November 1890 | Son of William II | Orange-Nassau |  |

| Wilhelmina | 31 August 1880 – 28 November 1962 (aged 82) | 23 November 1890 | 4 September 1948 | Daughter of William III | Orange-Nassau |  |

| Juliana | 30 April 1909 – 20 March 2004 (aged 94) | 4 September 1948 | 30 April 1980 | Daughter of Wilhelmina | Orange-Nassau |  |

| Beatrix | 31 January 1938 | 30 April 1980 | 30 April 2013 | Daughter of Juliana | Orange-Nassau |  |

| Willem-Alexander | 27 April 1967 | 30 April 2013 | Son of Beatrix | Orange-Nassau |  |

Royal family versus royal house

| Dutch royal family |

|

|

| * Member of the Dutch royal house |

Under Dutch law, there is a distinction between the royal family and the Dutch royal house. Whereas 'royal family' refers to the entire Orange-Nassau family, only a small subgroup of it constitutes the royal house. By the Royal House Membership Act 2002, membership of the royal house is limited to:[24][49]

The royal house and family is the Orange-Nassau family. [50]

- (Article 1) the reigning monarch (King or Queen);[49]

- (Article 1a) the members of the royal family in the line of succession to the Dutch throne, limited to the second degree of sanguinity reckoned from the reigning monarch;[49]

- (Article 1b) the heir presumptive of the reigning monarch;[49]

- (Article 1c) the former monarch (upon abdication);[49]

- (Article 2) the spouses of the above, even if the above die.[49]

- (Article 3) H.R.H. Princess Margriet of the Netherlands, (for whom an exception was made);[citation needed]

Members of the Royal House lose their membership (and thereby, designation as prince or princess of the Netherlands) if they lose the membership of the Royal House on the succession of a new monarch (not being in the second degree of sanguinity to the monarch anymore, Article 1a), or by royal decree approved by the Council of State (Article 5).[49] This last scenario could happen, for example, if a royal house member marries without the consent of the Dutch Parliament.[citation needed] For example, this happened with Prince Friso in 2004, when he married Mabel Wisse Smit.[citation needed]

Family tree

Origins of the Nassaus

The lineage of the House of Nassau can be traced back to the 10th century.

| Family tree of the House of Nassau | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The following family tree is compiled from Wikipedia and the reference cited in the note[51]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A detailed family tree can be found here.[52][53] A detailed family tree of the House of Orange-Nassau from the 15th century can be found on the Dutch Wikipedia at Dutch monarchs family tree.

Orange and Nassau Family Tree

| A summary family tree of the House of Orange-Nassau[54] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

From the joining of the house of Nassau-Breda/Dillenburg and the House of Châlon-Arlay-Orange to the end of the Dutch Republic is shown below. The family spawned many famous statesmen and generals, including two of the acknowledged "first captains of their age", Maurice of Nassau and the Marshal de Turenne.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The main house of Orange-Nassau also spawned several illegitimate branches. These branches contributed to the political and economic history of England and the Netherlands. Justinus van Nassau was the only extramarital child of William of Orange. He was a Dutch army commander known for unsuccessfully defending Breda against the Spanish, and the depiction of his surrender on the famous picture by Diego Velázquez, The Surrender of Breda. Louis of Nassau, Lord of De Lek and Beverweerd was a younger illegitimate son of Prince Maurice and Margaretha van Mechelen. His descendants were later created Counts of Nassau-LaLecq. One of his sons was the famous general Henry de Nassau, Lord of Overkirk, King William III's Master of the Horse, and one of the most trusted generals of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. His descendants became the Earls of Grantham in England. Frederick van Nassau, Lord of Zuylestein, an illegitimate son of Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, gave rise to the Earls of Rochford in England. The 4th earl of Rochford was a famous English diplomat and a statesman.

Royal House of Orange-Nassau

In 1815, William VI of Orange became King of the Netherlands. This summary genealogical tree shows how the current Royal house of Orange-Nassau is related:[24]

| William I, 1772–1843, King of the Netherlands, 1815–1840 | Wilhelmina of Prussia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| William II, 1792–1849, King of the Netherlands, 1840 | Anna Pavlovna of Russia | Prince Frederick of the Netherlands, 1797–1881 [55][56] | Princess Pauline of Orange-Nassau, 1800–1806 | Princess Marianne of the Netherlands, 1810–1883 [57] married Prince Albert of Prussia (1809–1872) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emma of Waldeck-Pyrmont | William III, 1817–1890, King of the Netherlands, 1849 | Sophia of Württemberg | Prince Alexander of the Netherlands, 1818–1848 | Prince Henry of the Netherlands, "the Navigator" 1820–1879 | Princess Sophie of the Netherlands, 1824–1897 married Charles Alexander, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach | Princess Louise of the Netherlands,1828–1871 married Charles XV of Sweden | Princess Marie of the Netherlands, 1841–1910 married William, Prince of Wied one son was William, Prince of Albania | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wilhelmina, 1880–1962, Queen of the Netherlands, 1890–1948 To 1907 after 1907 | Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin 1876–1934, Prince of the Netherlands | William, Prince of Orange 1840–1879 | Prince Maurice of the Netherlands, 1843–1850 | Alexander, Prince of Orange, 1851–1884 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juliana 1909–2004, Queen of the Netherlands, 1948–1980 | Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld, Prince of the Netherlands 1911–2004 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beatrix,1938–, Queen of the Netherlands,1980–2013 | Claus van Amsberg,1926–2002, Prince of the Netherlands | Princess Irene of the Netherlands, 1939, m.(1964–1981) Carlos Hugo of Bourbon-Parma, Duke of Parma, 4 children not eligible for throne | Princess Margriet of the Netherlands, 1943– | Pieter van Vollenhoven | Princess Christina of the Netherlands,(1947–2019), m. Jorge Pérez y Guillermo (m. 1975; div. 1996), 3 children not eligible for throne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| William-Alexander of the Netherlands,1967– Prince of Orange & Heir Apparent, 1980–2013, King of the Netherlands, 2013– | Queen Maxima of the Netherlands | Prince Friso of Orange-Nassau 1968–2013 m.(2004) Mabel Wisse Smit without permission, his children are not eligible for the throne and he was no longer a Prince of the Netherlands after his marriage | Prince Constantijn of the Netherlands, 1969– | Princess Laurentien of the Netherlands | 4 sons, 2 of whom were eligible for the throne until Beatrix abdicated in 2013 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Princess Catharina-Amalia of the Netherlands,2003– Princess of Orange & heiress apparent, 2013– | Princess Alexia of the Netherlands, 2005– | Princess Ariane of the Netherlands, 2007– | Countess Eloise of Orange-Nassau, 2002– | Count Claus-Casimir of Orange-Nassau, 2004– | Countess Leonore of Orange-Nassau, 2006– | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coats of Arms

The gallery below show the coats of arms used by members of the house of Orange-Nassau. Their growing complexity and use of crowns shows how arms are used to reflect the growing political position and royal aspirations of the family. A much more complete armorial is given at the Armorial of the House of Nassau, and another one at Wapen van Nassau, Tak van Otto at the Dutch Wikipedia.