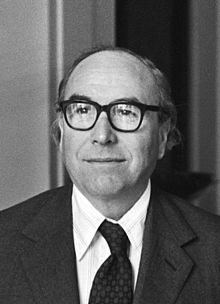

Roy Jenkins

The Lord Jenkins of Hillhead | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of the European Commission | |

| In office 6 January 1977 – 19 January 1981 | |

| Preceded by | François-Xavier Ortoli |

| Succeeded by | Gaston Thorn |

| Chancellor of the University of Oxford | |

| In office 14 March 1987 – 5 January 2003 | |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Stockton |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Patten of Barnes |

| Leader of the Social Democratic Party | |

| In office 7 July 1982 – 13 June 1983 | |

| Deputy | David Owen |

| Preceded by | The Gang of Four |

| Succeeded by | David Owen |

| Home Secretary | |

| In office 5 March 1974 – 10 September 1976 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson James Callaghan |

| Preceded by | Robert Carr |

| Succeeded by | Merlyn Rees |

| In office 23 December 1965 – 30 September 1967 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Frank Soskice |

| Succeeded by | James Callaghan |

| Shadow Home Secretary | |

| In office 25 November 1973 – 5 March 1974 | |

| Leader | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Shirley Williams |

| Succeeded by | Jim Prior |

| Deputy Leader of the Labour Party | |

| In office 8 July 1970 – 10 April 1972 | |

| Leader | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | George Brown |

| Succeeded by | Edward Short |

| Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 19 June 1970 – 10 April 1972 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Iain Macleod |

| Succeeded by | Denis Healey |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 30 November 1967 – 19 June 1970 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | James Callaghan |

| Succeeded by | Iain Macleod |

| Minister of Aviation | |

| In office 18 October 1964 – 23 December 1965 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Julian Amery |

| Succeeded by | Fred Mulley |

| Member of Parliament for Glasgow Hillhead | |

| In office 25 March 1982 – 11 June 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Tam Galbraith |

| Succeeded by | George Galloway |

| Member of Parliament for Birmingham Stechford | |

| In office 23 February 1950 – 31 March 1977 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency Created |

| Succeeded by | Andrew MacKay |

| Member of Parliament for Southwark Central | |

| In office 29 April 1948 – 23 February 1950 | |

| Preceded by | John Hanbury Martin |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Roy Harris Jenkins 11 November 1920 Abersychan, Wales |

| Died | 5 January 2003 (aged 82) Oxfordshire, England |

| Political party | Labour (Before 1981) Social Democratic (1981–1988) Liberal Democrats (1988–2003) |

| Alma mater | Cardiff University Balliol College, Oxford |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | Royal Artillery |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Roy Harris Jenkins, Baron Jenkins of Hillhead OM PC (11 November 1920 – 5 January 2003) was a British politician and writer.

The son of a Welsh coal miner, Roy Jenkins later became a union official and Labour MP. He also served with distinction in World War II. Elected to Parliament as a Labour member in 1948, he served in several major posts in Harold Wilson's First Government. As Home Secretary from 1965–1967, he sought to build what he described as "a civilised society", with measures such as the effective abolition in Britain of capital punishment and theatre censorship, the decriminalisation of homosexuality, relaxing of divorce law, suspension of birching and the liberalisation of abortion law. As Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1967–1970, he pursued a tight fiscal policy. On 8 July 1970,[1] he was elected Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, but resigned in 1972 because he supported entry to the Common Market, while the party opposed it.

When Wilson re-entered government in 1974 Jenkins returned to the Home Office, but increasingly disenchanted by the leftward swing of the Labour Party,[citation needed] he chose to leave British politics in 1976 and was appointed President of the European Commission in 1977, serving until 1981: he was the first and to date only British holder of this office. In 1981, dismayed with the Labour Party's continuing leftward drift, he was one of the "Gang of Four" – Labour moderates who formed the Social Democratic Party (SDP). In 1982 he won a famous by-election in a Conservative seat and returned to parliament; but after disappointment with the performance of the SDP in the 1983 election he resigned as SDP leader.

In 1987, Jenkins was elected to succeed Harold Macmillan as Chancellor of the University of Oxford following the latter's death; he held this position until his death. A few months after becoming Chancellor, Jenkins was defeated in his Hillhead constituency by the Labour candidate, George Galloway. Jenkins accepted a life peerage and sat as a Liberal Democrat. In the late 1990s, he was an adviser to Tony Blair and chaired the Jenkins Commission on electoral reform. Roy Jenkins died in 2003, aged 82.

In addition to his political career, he was also a noted historian, biographer and writer. His A Life at the Centre (1991) is regarded as one of the best autobiographies of the later 20th century, which 'will be read with pleasure long after most examples of the genre have been forgotten'.[2]

Early life

Born in Abersychan, Monmouthshire, in south-eastern Wales, as an only child, Roy Jenkins was the son of a National Union of Mineworkers official, Arthur Jenkins. His father was imprisoned during the 1926 General Strike for his alleged involvement in a disturbances. Jenkins later became President of the South Wales Miners' Federation and Member of Parliament for Pontypool, Parliamentary Private Secretary to Clement Attlee, and briefly a minister in the 1945 Labour government. Jenkins's mother, Hattie Harris, was the daughter of a steelworks manager.

Jenkins was educated at Abersychan County Grammar School, University College, Cardiff, and at Balliol College, Oxford, where he was twice defeated for the Presidency of the Oxford Union but took First-Class Honours in Politics, Philosophy and Economics (PPE). His university colleagues included Tony Crosland, Denis Healey, and Edward Heath, and he became friends with all three, although he was never particularly close to Healey.

During the Second World War, Jenkins served with the Royal Artillery and then as a Bletchley Park codebreaker, reaching the rank of captain.

Member of Parliament (1948–1977)

Having failed to win Solihull in 1945, he was elected to the House of Commons in a 1948 by-election as the Member of Parliament for Southwark Central, becoming the "Baby of the House." His constituency was abolished in boundary changes for the 1950 general election, when he stood instead in the new Birmingham Stechford constituency. He won the seat and represented the constituency until 1977.

Jenkins was principal sponsor, in 1959, of the bill which became the liberalising Obscene Publications Act, responsible for establishing the "liable to deprave and corrupt" criterion as a basis for a prosecution of suspect material and for specifying literary merit as a possible defence. Like Healey and Crosland, he had been a close friend of Hugh Gaitskell and for them Gaitskell's death and the elevation of Harold Wilson as Labour Party leader was a setback.

After the 1964 general election Jenkins was appointed Minister of Aviation. While at Aviation he oversaw the high profile cancellations of the BAC TSR-2 and Concorde projects (although the latter was later reversed after strong opposition from the French Government). In January 1965 Patrick Gordon Walker resigned as Foreign Secretary and in the ensuing reshuffle Wilson offered Jenkins the Department for Education and Science; however. he declined it, preferring to stay at Aviation.[3]

Cabinet (1965–1970)

In the summer of 1965 Jenkins eagerly accepted an offer to replace Frank Soskice as Home Secretary. However Wilson, dismayed by a sudden bout of press speculation about the potential move, delayed Jenkins' appointment until December. Once Jenkins took office – the youngest Home Secretary since Churchill – he immediately set about reforming the operation and organisation of the Home Office. The Principal Private Secretary, Head of the Press and Publicity Department and Permanent Under-Secretary were all replaced. He also redesigned his office, famously replacing the board on which condemned prisoners were listed with a drinks cabinet. After the 1966 general election, in which Labour won a comfortable majority, Jenkins pushed through a series of police reforms which reduced the number of separate forces from 117 to 49.[3]

Immigration was a divisive and provocative issue during the late 1960s and on 23 May 1966 Jenkins delivered a speech on race relations, which is widely considered to be one of his best.[4] Addressing a London meeting of the National Committee for Commonwealth Immigrants he notably defined Integration:

... not as a flattening process of assimilation but as equal opportunity, accompanied by cultural diversity, in an atmosphere of mutual tolerance.

Before going onto ask:

Where in the world is there a university which could preserve its fame, or a cultural centre which could keep its eminence, or a metropolis which could hold its drawing power, if it were to turn inwards and serve only its own hinterland and its own racial group?

And concluding that:

To live apart, for a person, a city, a country, is to lead a life of declining intellectual stimulation.[4]

Jenkins is often seen as responsible for the most wide-ranging social reforms of the late 1960s, with popular historian Andrew Marr claiming 'the greatest changes of the Labour years' were thanks to Jenkins.[5] He refused to authorise the birching of prisoners and was responsible for the relaxation of the laws relating to divorce, abolition of theatre censorship and gave government support to David Steel's Private Member's Bill for the legalisation of abortion and Leo Abse's bill for the decriminalisation of homosexuality. Wilson, with his puritan background, was not especially sympathetic to these developments, however. Jenkins replied to public criticism by asserting that the so-called permissive society was in reality the civilised society. For some conservatives, such as Peter Hitchens, Jenkins' reforms remain objectionable. In his book The Abolition of Britain Hitchens accuses him of being a "cultural revolutionary" who takes a large part of the responsibility for the decline of "traditional values" in Britain.

From 1967 to 1970 Jenkins served as Chancellor of the Exchequer, replacing James Callaghan following the devaluation crisis of November 1967. He quickly gained a reputation as a particularly tough Chancellor with his 1968 budget increasing taxes by £923 million, more than twice the increase of any previous budget to date. Despite Edward Heath claiming it was a 'hard, cold budget, without any glimmer of warmth' Jenkins' first budget broadly received a warm reception, with Harold Wilson remarking that 'it was widely acclaimed as a speech of surpassing quality and elegance' and Barbara Castle that it 'took everyone's breath away'.[3] However, following a further sterling crisis in November 1968 Jenkins was forced to raise taxes by a further £250 million. After this the currency markets slowly began to settle and his 1969 budget represented more of the same with a £340 million increase in taxation to further limit consumption.

By May 1969 Britain's current account position was in surplus, thanks to a growth in exports, a drop in overall consumption and, in part, the Inland Revenue correcting a previous underestimation in export figures. In July Jenkins was also able to announce that the size of Britain's foreign currency reserves had been increased by almost $1 billion since the beginning of the year. It was at this time that he presided over Britain's only excess of government revenue over expenditure in the period 1936-7 to 1987–8.[3] Thanks in part to these successes there was a high expectation that the 1970 budget would be a more generous one. Jenkins, however, was cautious about the stability of Britain's recovery and decided to present a more muted and fiscally neutral budget. It is often argued that this, combined with a series of bad trade figures, contributed to the Conservative victory at the 1970 general election. Historians and economists have often praised Jenkins for presiding over the transformation in Britain's fiscal and current account positions towards the end of the 1960s. Andrew Marr, for example, described him as one of the 20th century's 'most successful chancellors'.[5]

Shadow Cabinet (1970–1974)

After Labour unexpectedly lost power in 1970 Jenkins was appointed Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer by Harold Wilson. Jenkins was also subsequently elected to the deputy leadership of the Labour Party in July 1970, defeating future Labour Leader Michael Foot and former Leader of the Commons Fred Peart at the first ballot. At this time he appeared the natural successor to Harold Wilson, and it appeared to many only a matter of time before he inherited the leadership of the party, and the opportunity to become Prime Minister.[2]

This changed completely, however, as Jenkins refused to accept the tide of anti-European feeling that became prevalent in the Labour Party in the early 1970s. In 1972, he led sixty-nine Labour MPs through the division lobby in support of the Heath's government's motion to take Britain into the EEC. In so-doing they were defying a three-line whip and a five-to-one vote at the Labour Party annual conference.[2] Jenkins's action gave the European cause a legitimacy that would have otherwise been absent had the issue been considered solely as a party political matter. At this stage, however, Jenkins would not fully abandon his position as a political insider, and chose to stand again for deputy leader, an act his colleague David Marquand claimed he later came to regret.[2] Jenkins narrowly defeated Michael Foot on a second ballot.

Six months later, however, he resigned both the deputy leadership and his shadow cabinet position in April 1972, over the party's policy on favouring a referendum on British membership of the European Economic Community (EEC). This led to some former admirers, including Roy Hattersley, choosing to distance themselves from Jenkins. His lavish lifestyle — Wilson once described him as "more a socialite than a socialist" — had already alienated much of the Labour Party from him. Jenkins returned to the shadow cabinet in November 1973 as Shadow Home Secretary.

Return to Government (1974–1977)

When Labour returned to power in early 1974, Jenkins was appointed Home Secretary for the second time. Earlier, he had been promised the treasury; however, Wilson later decided to appoint Denis Healey as Chancellor instead. Upon hearing from Bernard Donoughue that Wilson had reneged on his promise, Jenkins reacted angrily. Despite being on a public staircase, he is reported to have shouted 'You tell Harold Wilson he must bloody well come to see me ... and if he doesn't watch out, I won't join his bloody government ... This is typical of the bloody awful way Harold Wilson does things!'[6]

Jenkins served from 1974 to 1976. In this period he undermined his previous liberal credentials to some extent by pushing through the controversial Prevention of Terrorism Act, which, among other things, extended the length of time suspects could be held in custody and instituted exclusion orders. Although becoming increasingly disillusioned during this time by what he considered the party's drift to the left, he was the leading Labour figure in the referendum in September 1975 which saw the 'yes' campaign win a two-to-one victory in the referendum on continued membership of the European Community.

President of the European Commission (1977–1981)

When Harold Wilson suddenly resigned as Prime Minister, Jenkins was one of six candidates for the leadership of the Labour Party in March 1976, but came third out of the six candidates in the first ballot, behind Callaghan and Michael Foot. Realising that his vote was lower than expected, and sensing that the parliamentary party was in no mode to overlook his actions five years before, he immediately withdrew from the contest.[2] Jenkins had wanted to become Foreign Secretary,[7] but accepted an appointment as President of the European Commission (succeeding François-Xavier Ortoli) after Callaghan appointed Anthony Crosland to the Foreign Office.

The main development overseen by the Jenkins Commission was the development of the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union from 1977, which began in 1979 as the European Monetary System, a forerunner of the Single Currency or Euro.[8] President Jenkins was the first President to attend a G8 summit on behalf of the Community.[9] Jenkins remained in Brussels until 1981, contemplating the political changes in the UK from there.

He received an Honorary Degree (Doctor of Laws) from the University of Bath in 1978.[10]

Return to Parliament (1982–1987)

He attempted to re-enter Parliament at the Warrington by-election in 1981 but Labour retained the seat with a small majority. He was more successful in 1982, being elected in the Glasgow Hillhead by-election as the Member of Parliament for a previously Conservative-held seat.

Leadership of the Social Democratic Party

As one of the so-called "Gang of Four", Roy Jenkins was a founder of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in January 1981 with David Owen, Bill Rodgers and Shirley Williams.

During the 1983 election campaign his position as the prime minister designate for the SDP-Liberal Alliance was questioned by his close colleagues, as his campaign style was now regarded as ineffective; the Liberal leader David Steel was considered to have a greater rapport with the electorate.

He led the new party from March 1982 until after the 1983 general election, when Owen succeeded him unopposed. Jenkins was disappointed with Owen's move to the right, and his acceptance and backing of some of Thatcher's policies. At heart, Jenkins remained a Keynesian.

He continued to serve as SDP Member of Parliament for Glasgow Hillhead until his defeat at the 1987 general election by the Labour candidate George Galloway.

Peerage, achievements, books and death

From 1987, Jenkins remained in politics as a member of the House of Lords as a life peer with the title Baron Jenkins of Hillhead, of Pontypool in the County of Gwent.[11] Also in 1987, Jenkins was elected Chancellor of the University of Oxford.

In 1988 he fought and won an amendment to the Education Reform Act of that year, guaranteeing academic freedom of speech in further and higher education establishments. This affords and protects the right of students and academics to "question and test received wisdom" and has been incorporated into the statutes or articles and instruments of governance of all universities and colleges in Britain.[12]

In 1993, he was appointed to the Order of Merit.[13] He was leader of the Liberal Democrats in the Lords until 1997.

In December 1997, he was appointed chair of a Government-appointed Independent Commission on the Voting System, which became known as the "Jenkins Commission", to consider alternative voting systems for the UK. The Jenkins Commission reported in favour of a new uniquely British mixed-member proportional system called "Alternative vote top-up" or "limited AMS" in October 1998, although no action was taken on this recommendation.

Jenkins wrote 19 books, including a biography of Gladstone (1995), which won the 1995 Whitbread Award for Biography, and a much-acclaimed biography of Winston Churchill (2001). His official biographer, Andrew Adonis, Baron Adonis, was to have finished the Churchill biography had Jenkins not survived the heart surgery he underwent towards the end of its writing. Churchill's daughter Lady Mary Soames believed the Jenkins biography of her father to be the best available.[14]

Jenkins underwent heart surgery in November 2000, and postponed his 80th birthday celebrations, by having a celebratory party on 7 March 2001. He died on 5 January 2003, aged 82, after suffering a heart attack at his home at East Hendred, in Oxfordshire.[15] His last words, to his wife, were, "Two eggs, please, lightly poached".[16] At the time of his death Jenkins was apparently starting work on a biography of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Jenkins is seen by many as a key influence on "New Labour", as the Labour Party marketed itself after the election of Tony Blair (who served as prime minister from winning the first of three successive general elections in 1997) in 1994, when the party abandoned many of its long-established policies including nationalisation, nuclear disarmament and unconditional support for the trade unions. He was well regarded by other Labour statesmen including Tony Benn, but came under heavy criticism from others including Denis Healey, who condemned the SDP split as a "disaster" for the Labour Party which prolonged their time in opposition and allowed the Tories to have an unbroken run of 18 years in government.[17]

Cardiff University honours the memory of Roy Jenkins by naming one of its halls of residence 'Roy Jenkins Hall'.

Marriage and personal life

On 20 January 1945, in the final year of the War, he married Jennifer Morris. They were married for 58 years until his death, although he had "several affairs".[18]

She was made a DBE for services to ancient and historical buildings. They had two sons, Charles and Edward, and a daughter, Cynthia.

Dame Jennifer Jenkins is still alive, now in her nineties, more than a decade after her husband's death.

Works

- Roosevelt. Pan Macmillan. 2005. ISBN 0-330-43206-0.

- Churchill. Macmillan. 2001. ISBN 0-333-78290-9.

- The Chancellors. Macmillan. 1998. ISBN 0-333-73057-7.

- Gladstone. Macmillan. 1995. ISBN 0-8129-6641-4.

- Portraits and Miniatures. Bloomsbury. 1993. ISBN 9781448203215.

- A life at the centre. Macmillan. 1991. ISBN 0-333-55164-8.

- Gallery of 20th century Portraits and Oxford Papers. David and Charles. 1989. ISBN 0-7153-9299-9.

- Truman. HarperCollins. 1986. ISBN 0-06-015580-9.

- Baldwin. Collins. 1984. ISBN 0-00-217586-X.

- Asquith. Collins. 1964. ISBN 0-00-211021-0., revised edition 1978

- Sir Charles Dilke: A Victorian Tragedy. Collins. 1958. ISBN 0-333-62020-8.

- Mr. Balfour's poodle; peers v. people. Collins. 1954. OCLC 436484.

References

- ^ "Jenkins Labour deputy leader". The Glasgow Herald. 9 July 1970. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Marquand, David (8 January 2003). "Lord Jenkins of Hillhead". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d Roy Jenkins. A Life at the Centre. Politico's. ISBN 978-1-84275-177-0.

- ^ a b MacArthur, Brian (ed.). The Penguin Book of Twentieth-Century Speeches. ISBN 978-0-14-028500-0.

- ^ a b Andrew Marr. A History of Modern Britain. ISBN 978-1-4050-0538-8.

- ^ Dominic Sandbrook. State of Emergency – The Way We Were: Britain 1970–1974. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-1-84614-031-0.

- ^ Dick Leonard "Roy Jenkins (Lord Jenkins of Hillhead)" in Greg Rosen (2001) Dictionary of Labour Biography, London: Politicos, 2001, pp.314–8, 318

- ^ http://www.euro-know.org/europages/dictionary/j.html

- ^ "EU and the G8". European Commission. Archived from the original on 26 February 2007. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ^ "Honorary Graduates 1989 to present". University of Bath. Archived from the original on 17 July 2010.

- ^ "No. 51132". The London Gazette. 25 November 1987.

- ^ Hayes, Dennis. "Tongues truly tied". Times Higher Education. The Times. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ "No. 53510". The London Gazette. 10 December 1993.

- ^ Mary Soames (3 September 2011). "From her private diaries, Winston Churchill's daughter Lady Mary Soames gives a vivid account of London society at war". Mail Online. Daily Mail. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011.

- ^ "Roy Jenkins dies". BBC News Online. BBC. 5 January 2003. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 28 September 2013 suggested (help) - ^ John Campbell (2014) Roy Jenkins: A Well-Rounded Life

- ^ White, Michael (6 January 2003). "Roy Jenkins: Gang leader who paved way for Blair". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 23 April 2010.

- ^ Template:Cite television

Further reading

- Andrew Adonis & Keith Thomas — Editors (2004). Roy Jenkins: A Retrospective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-927487-8.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Giles Radice (2002). Friends and Rivals: Crosland, Jenkins and Healey. Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-85547-2.

- John Campbell (1983). Roy Jenkins, a biography. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-78271-1.

- John Campbell (2014). Roy Jenkins, a Well-Rounded Life. Jonathan Cape. ISBN 9-780-22408750-6.

External links

Quotations related to Roy Jenkins at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Roy Jenkins at Wikiquote Works by or about Roy Jenkins at Wikisource

Works by or about Roy Jenkins at Wikisource- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Roy Jenkins

- 1920 births

- 2003 deaths

- 20th-century biographers

- Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford

- Alumni of Cardiff University

- British biographers

- British European Commissioners

- British historians

- British Army personnel of World War II

- British pro-choice activists

- Chancellors of the Exchequer of the United Kingdom

- Chancellors of the University of Oxford

- Labour Party (UK) MPs

- Labour Party (UK) politicians

- Liberal Democrat life peers

- Members of the Order of Merit

- Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies

- Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Scottish constituencies

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- People associated with Bletchley Park

- People educated at Abersychan Grammar School

- People from Pontypool

- Presidents of the European Commission

- Royal Artillery officers

- Secretaries of State for the Home Department

- Social Democratic Party (UK) MPs

- Social Democratic Party (UK) life peers

- UK MPs 1945–50

- UK MPs 1950–51

- UK MPs 1951–55

- UK MPs 1955–59

- UK MPs 1959–64

- UK MPs 1964–66

- UK MPs 1966–70

- UK MPs 1970–74

- UK MPs 1974

- UK MPs 1974–79

- UK MPs 1979–83

- UK MPs 1983–87

- Welsh politicians