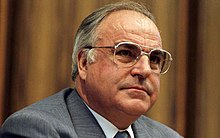

Helmut Kohl

Helmut Kohl | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chancellor of Germany | |

| In office 1 October 1982 – 27 October 1998* | |

| President | Karl Carstens Richard von Weizsäcker Roman Herzog |

| Deputy | Hans-Dietrich Genscher Jürgen Möllemann Klaus Kinkel |

| Preceded by | Helmut Schmidt |

| Succeeded by | Gerhard Schröder |

| Minister-President of Rhineland-Palatinate | |

| In office 19 May 1969 – 2 December 1976 | |

| Preceded by | Peter Altmeier |

| Succeeded by | Bernhard Vogel |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Helmut Josef Michael Kohl 3 April 1930 Ludwigshafen, Germany |

| Political party | Christian Democratic Union (1946–present) |

| Spouse(s) | Hannelore Renner (1960–2001) Maike Richter (2008–present) |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater | Heidelberg University |

| Signature |  |

| |

Helmut Josef Michael Kohl (German: [ˈhɛlmuːt ˈkoːl]; born 3 April 1930) is a German conservative politician and statesman. He served as Chancellor of Germany from 1982 to 1998 (of West Germany 1982–90 and of the reunited Germany 1990–98) and as the chairman of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) from 1973 to 1998.

His 16-year tenure was the longest of any German chancellor since Otto von Bismarck, and oversaw the end of the Cold War. Kohl is widely regarded as the main architect of the German reunification, and together with French president François Mitterrand, he is also considered the architect of the Maastricht Treaty, which established the European Union.[1]

Kohl and Mitterrand were the joint recipients of the Charlemagne Prize in 1988.[2] In 1996, he won the prestigious Prince of Asturias Award in International Cooperation.[3] In 1998, Kohl was named Honorary Citizen of Europe by the European heads of state or government for his extraordinary work for European integration and cooperation, an honour previously only bestowed on Jean Monnet.[4]

Kohl was described as "the greatest European leader of the second half of the 20th century" by U.S. Presidents George H. W. Bush[5] and Bill Clinton.[6]

Life

Youth

Kohl was born in Ludwigshafen am Rhein (at the time part of Bavaria, now in Rhineland-Palatinate) Germany, the third child of Hans Kohl (1887–1975), a civil servant, and his wife, Cäcilie (née Schnur; 1890–1979). His family was conservative and Roman Catholic, and remained loyal to the Catholic Centre Party before and after 1933. His older brother died in the Second World War as a teenage soldier. In the last weeks of the war, Kohl was also drafted, but he was not involved in any combat.

Kohl attended the Ruprecht elementary school, and continued at the Max-Planck-Gymnasium. In 1946, he joined the recently founded CDU. In 1947, he was one of the co-founders of the Junge Union-branch in Ludwigshafen. After graduating in 1950, he began to study law in Frankfurt am Main. In 1951, he switched to the University of Heidelberg where he majored in History and Political Science. In 1953, he joined the board of the Rhineland-Palatinate branch of the CDU. In 1954, he became vice-chair of the Junge Union in Rhineland-Palatinate. In 1955, he returned to the board of the Rhineland-Palatinate branch of the CDU. [citation needed]

Life before politics

After graduating in 1956 he became fellow at the Alfred Weber Institute of the University of Heidelberg where he was an active member of the student society AIESEC. In 1958, he received his doctorate degree for his thesis "The Political Developments in the Palatinate and the Reconstruction of Political Parties after 1945". After that, he entered business, first as an assistant to the director of a foundry in Ludwigshafen and, in 1959, as a manager for the Industrial Union for Chemistry in Ludwigshafen. In this year, he also became chair of the Ludwigshafen branch of the CDU. In the following year, he married Hannelore Renner, whom he had known since 1948, and they had two sons.

Early political career

In 1960, he was elected into the municipal council of Ludwigshafen where he served as leader of the CDU party until 1969. In 1963, he was also elected into the Landtag and served as leader of the CDU party in that legislature. From 1966 until 1973, he served as the chair of the CDU's state branch, and he was also a member of the Federal CDU board. After his election as party-chair, he was named as the successor to Peter Altmeier, who was minister-president of Rhineland-Palatinate at the time. However, after the Landtag-election which followed, Altmeier remained minister-president.

Minister-President of Rhineland-Palatinate

On 19 May 1969, Kohl was elected minister-president of Rhineland-Palatinate, as the successor to Peter Altmeier. During his term as minister-president, Kohl founded the University of Trier-Kaiserslautern and enacted territorial reform. Also in 1969, Kohl became the vice-chair of the federal CDU party. In 1971, he was a candidate to become chairman of the federal CDU, but was not elected. Rainer Barzel remained in the position instead. In 1972, Barzel attempted to force a cabinet crisis in the SPD/FDP government, which failed, leading him to step down. In 1973, Kohl succeeded him as federal chairman; he retained this position until 1998. [citation needed]

The 1976 Bundestag election

In the 1976 federal election, Kohl was the CDU/CSU's candidate for chancellor. The CDU/CSU coalition performed very well, winning 48.6% of the vote. However they were kept out of government by the centre-left cabinet formed by the Social Democratic Party of Germany and Free Democratic Party (Germany), led by Social Democrat Helmut Schmidt. Kohl then retired as minister-president of Rhineland-Palatinate to become the leader of the CDU/CSU in the Bundestag. He was succeeded by Bernhard Vogel.

Leader of the opposition

In the 1980 federal elections, Kohl had to play second fiddle, when CSU-leader Franz Josef Strauß became the CDU/CSU's candidate for chancellor. Strauß was also unable to defeat the SPD/FDP alliance. Unlike Kohl, Strauß did not want to continue as the leader of the CDU/CSU and remained Minister-President of Bavaria. Kohl remained as leader of the opposition, under the third Schmidt cabinet (1980–82). On 17 September 1982, a conflict of economic policy occurred between the governing SPD/FDP coalition partners. The FDP wanted to radically liberalise the labour market, while the SPD preferred to guarantee the employment of those who already had jobs. The FDP began talks with the CDU/CSU to form a new government. [citation needed]

Chancellor of West Germany

Rise to power

On 1 October 1982, the CDU proposed a constructive vote of no confidence which was supported by the FDP. The motion carried. Three days later, the Bundestag voted in a new CDU/CSU-FDP coalition cabinet, with Kohl as the chancellor. Many of the important details of the new coalition had been hammered out on 20 September, though minor details were reportedly still being hammered out as the vote took place. Though Kohl's election was done according to the Basic Law, some voices criticized the move as the FDP had fought its 1980 campaign on the side of the SPD and even placed Chancellor Schmidt on some of their campaign posters. Some voices went as far as denying that the new government had the support of a majority of the people. In answer, the new government aimed at new elections at the earliest possible date. As the Basic Law is restrictive on the dissolution of parliament, Kohl had to take another controversial move: he called for a confidence vote only a month after being sworn in, in which members of his coalition abstained. The ostensibly negative result for Kohl then allowed President Karl Carstens to dissolve the Bundestag in January 1983. [citation needed]

The move was controversial as the coalition parties denied their votes to the same man they had elected Chancellor a month before and whom they wanted to re-elect after the parliamentary election. However, this step was condoned by the German Federal Constitutional Court as a legal instrument and was again applied (by SPD Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and his Green allies) in 2005.

The second cabinet

In the federal elections of March 1983, Kohl won a resounding victory. The CDU/CSU won 48.8%, while the FDP won 7.0%. Some opposition members of the Bundestag asked the Federal constitutional court to declare the whole proceedings unconstitutional. It denied their claim. The second Kohl cabinet pushed through several controversial plans, including the stationing of NATO midrange missiles, against major opposition from the peace movement. On 24 January 1984, Kohl spoke before the Israeli Knesset, as the first Chancellor of the post-war generation. In his speech, he used liberal journalist Günter Gaus' famous sentence that he had "the mercy of a late birth" ("Gnade der späten Geburt"). [citation needed]

On 22 September 1984 Kohl met the French president François Mitterrand at Verdun, where the Battle of Verdun between France and Germany had taken place during World War I. Together, they commemorated the deaths of both World Wars. The photograph, which depicted their minutes long handshake became an important symbol of French-German reconciliation. Kohl and Mitterrand developed a close political relationship, forming an important motor for European integration. Together, they laid the foundations for European projects, like Eurocorps and Arte. This French-German cooperation also was vital for important European projects, like the Treaty of Maastricht and the Euro.

In 1985, Kohl and US President Ronald Reagan, as part of a plan to observe the 40th anniversary of V-E Day, saw an opportunity to demonstrate the strength of the friendship that existed between Germany and its former foe. During a November 1984 visit to the White House, Kohl appealed to Reagan to join him in symbolizing the reconciliation of their two countries at a German military cemetery. As Reagan visited Germany as part of the G6 conference in Bonn, the pair visited Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on 5 May, and more controversially, the German military cemetery at Bitburg, discovered to hold 49 members of the Waffen-SS. [citation needed]

The third cabinet

After the federal elections of 1987 Kohl won a slightly reduced majority and formed his third cabinet. The SPD's candidate for chancellor was the Minister-President of North Rhine-Westphalia, Johannes Rau. [citation needed]

In 1987, Kohl received East German leader Erich Honecker – the first ever visit by an East German head of state to West Germany. This is generally seen as a sign that Kohl pursued Ostpolitik, a policy of détente between East and West that had been begun by the SPD-led governments (and strongly opposed by Kohl's own CDU) during the 1970s. [citation needed]

The road to reunification

Following the breach of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the East German Communist regime in 1989, Kohl's handling of the East German issue would become the turning point of his chancellorship. Kohl, like most West Germans, was initially caught unaware when the Socialist Unity Party was toppled in late 1989. However, well aware of his constitutional mandate to seek German unity, he immediately moved to make it a reality. Taking advantage of the historic political changes occurring in East Germany, Kohl presented a ten-point plan for "Overcoming of the division of Germany and Europe" without consulting his coalition partner, the FDP, or the Western Allies. In February 1990, he visited the Soviet Union seeking a guarantee from Mikhail Gorbachev that the USSR would allow German reunification to proceed. One month later, the Party of Democratic Socialism — the renamed SED — was roundly defeated by a grand coalition headed by the East German counterpart of Kohl's CDU, which ran on a platform of speedy reunification. [7]

By the spring of 1990, the East German economy had sunk into near-paralysis. Accordingly, on 18 May 1990, Kohl signed an economic and social union treaty with East Germany. This treaty stipulated that when reunification took place, it would be under the quicker provisions of Article 23 of the Basic Law. That article stated that any new states could adhere to the Basic Law by a simple majority vote. The alternative would have been the more protracted route of drafting a completely new constitution for the newly reunified country, as provided by Article 146 of the Basic Law. Over the objections of Bundesbank president Karl Otto Pöhl, he allowed a 1:1 exchange rate for wages, interest and rent between the West and East Marks. In the end, this policy would seriously hurt companies in the new federal states. Together with Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Kohl was able to resolve talks with the former Allies of World War II to allow German reunification. He received assurances from Gorbachev that a reunified Germany would be able to choose which international alliance it wanted to join, although Kohl made no secret that he wanted the reunified Germany to remain part of NATO and the EC.

A reunification treaty was signed on 31 August 1990, and was overwhelmingly approved by both parliaments on 20 September 1990. On 3 October 1990, East Germany officially ceased to exist, and its territory joined the Federal Republic as the five states of Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia. These states had been the original five states of East Germany before being abolished in 1952, and had been reconstituted in August. East and West Berlin were reunited as the capital of the enlarged Federal Republic. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Kohl confirmed that historically German territories east of the Oder-Neisse line were definitively part of Poland, thereby relinquishing any claim Germany had to them. In 1993, Kohl confirmed, via treaty with the Czech Republic, that Germany would no longer bring forward territorial claims as to the pre-1945 ethnic German so-called Sudetenland. This treaty was a disappointment for the German Heimatvertriebene ("displaced persons").[8][9][10]

Chancellor of reunified Germany

Reunification placed Kohl in a momentarily unassailable position. In the 1990 elections – the first free, fair and democratic all-German elections since the Weimar Republic era – Kohl won by a landslide over opposition candidate and Minister-President of Saarland, Oskar Lafontaine. He then formed his fourth cabinet.

After the federal elections of 1994 Kohl narrowly defeated Minister-President of Rhineland-Palatinate Rudolf Scharping. The SPD was however able to win a majority in the Bundesrat, which significantly limited Kohl's power. In foreign politics, Kohl was more successful, for instance getting Frankfurt am Main as the seat for the European Central Bank. In 1997, Kohl received the Vision for Europe Award for his efforts in the unification of Europe.

By the late 1990s, the aura surrounding Kohl had largely worn off amid rising unemployment. He was heavily defeated in the 1998 federal elections by the Minister-President of Lower Saxony, Gerhard Schröder.[7]

Retirement and legal troubles

A red-green coalition government led by Schröder replaced Kohl's government on 27 October 1998. He immediately resigned as CDU leader and largely retired from politics. However, he remained a member of the Bundestag until he decided not to run for reelection in the 2002 election.

CDU finance affair

Kohl's life after political office in the beginning was dominated by the CDU-party finance scandal. The party financing scandal became public in 1999, when it was discovered that the CDU had received and kept illegal donations during Kohl's leadership.[11]

Life after politics

| Part of a series on |

| Christian democracy |

|---|

|

|

|

In 2002, Kohl left the Bundestag and officially retired from politics. In recent years, Kohl has been largely rehabilitated by his party again. After taking office, Angela Merkel invited her former patron to the Chancellor's Office and Ronald Pofalla, the Secretary-General of the CDU, announced that the CDU will cooperate more closely with Kohl, "to take advantage of the experience of this great statesman", as Pofalla put it. On 5 July 2001, his wife, Hannelore, committed suicide, due to suffering from photodermatitis for many years. On 4 March 2004, he published the first of his memoirs, called "Memories 1930–1982", covering the period 1930 to 1982, when he became chancellor. The second part, published on 3 November 2005, included the first half of his chancellorship (from 1982–90). On 28 December 2004, he was air-lifted by the Sri Lankan Air Force, after having been stranded in a hotel by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. Kohl is a member of the Club of Madrid.[12]

As reported in the German press, he also gave his name to the soon-to-be launched Helmut Kohl Centre for European Studies (currently Centre for European Studies), which is the new political foundation of the European People's Party. In late February 2008, Kohl suffered a stroke in combination with a fall which caused serious head injuries and required his hospitalization, since when he has been reported as bound to a wheelchair due to partial paralysis and with difficulty speaking.[13][14][15][16][17] He has remained in intensive care since, marrying his 43-year-old partner, Maike Richter, on 8 May 2008, while still in hospital. In 2010, he had a gall bladder operation in Heidelberg,[18] and heart surgery in 2012.[19]

Political views

Kohl was committed to European integration, maintaining close relations with the French president Mitterrand. Parallel to this he was committed to German reunification. Although he continued the Ostpolitik of his social-democratic predecessors, Kohl supported Reagan's more aggressive policies in order to weaken the USSR. [citation needed]

Public perception

Kohl faced stiff opposition from the West German political left and was also mocked for his provincial background, physical stature and simple language. Similar to historical French cartoons of Louis-Philippe of France, Hans Traxler depicted Kohl as a pear in the left-leaning satirical journal Titanic.[20] The German word "Birne" ("pear") became a widespread nickname and symbol for the Chancellor.[21]

Honors

- In 1988, Kohl and Mitterrand received the Karlspreis for his contribution to Franco-German friendship and European Union.[2]

- In 1996, Kohl received the Prince of Asturias Award in International Cooperation

- In 1996, he was made honorary doctor of the Catholic University of Louvain.

- In 1996, Kohl received an award for his humanitarian achievements from the Jewish organisation B'nai B'rith.

- In 1996, Kohl received a Doctor of Humanities, Honoris Causa from the Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines, a Jesuit run institution.

- On 11 December 1998, the European Council awarded him the title Honorary Citizen of Europe, a title which only Jean Monnet had received before.[4][22]

- In 1998, he received an honorary doctor of laws degree from Brandeis University in Massachusetts.[23]

- In 1998, he was only the second person to be awarded the Grand Cross in Special Design of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, the other being Konrad Adenauer.[24]

- In 1999, Kohl received Presidential Medal of Freedom from U.S. president Clinton.

- Kohl is honorary citizen of both Frankfurt am Main and Berlin. On 2 September 2005, he was made an honorary citizen of his home town, Ludwigshafen.

- In 2007, he received the Gold Medal of the Jean Monnet Foundation for Europe for his contribution to the unity of Europe.

- On 16 May 2011, Kohl received the Henry A. Kissinger Prize at the American Academy in Berlin for his "singularly extraordinary role in German reunification and laying the foundation for a lasting democratic peace in the new millennium".[25]

See also

References

- ^ Chambers, Mortimer. The Western Experience.

- ^ a b "Der Karlspreisträger 1988" (in German). Stiftung Internationaler Karlspreis zu Aachen. Retrieved 1 March 2008. [dead link]

- ^ Helmut Kohl

- ^ a b "European leaders honour Kohl". BBC NEWS. 11 December 1998.

- ^ Time, Helmut Kohl, by George H. W. Bush

- ^ M&C news, "Clinton praises Germany's Kohl at Berlin Award", by Deutsche Presse Agentur

- ^ a b Thompson, Wayne C. (2008). The World Today Series: Nordic, Central and Southeastern Europe 2008. Harpers Ferry, West Virginia: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-887985-95-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Rödder 2009, S. 236 f.; Heinrich August Winkler: Der lange Weg nach Westen. Zweiter Band: Deutsche Geschichte vom «Dritten Reich» bis zur Wiedervereinigung. Fünfte, durchgesehene Auflage, München 2002, S. 552.

- ^ "Während die polnische Seite noch weiter auf die Heimatvertriebenen zugehen muß - Worte allein sind eben nicht genug - müssen die ... Verständliche Enttäuschung und Verbitterung in den Reihen der Vertriebenen, die vielfach zu einer Verweigerungshaltung geführt haben, dürfen ..." (Friedbert Pflüger, Winfried Lipscher, Feinde werden Freunde: Von den Schwierigkeiten der deutsch-polnischen Nachbarschaft, Bouvier Verlag, 1993, p. 425.

- ^ "Kohl hat das Gegenteil getan und dadurch Enttäuschung und Bitterkeit geradezu vorprogrammiert. Dieser innenpolitischen Einschätzung Vogels ist nichts hinzuzufügen. (Jahrestag der Charta der deutschen Heimatvertriebenen am 5....)" Richard Saage, Axel Rüdiger, Feinde werden Freunde: Elemente einer politischen Ideengeschichte der Demokratie:historisch-politische Studien, Duncker & Humblot, 2006, p. 285.

- ^ Gerd Langguth, "The scandal that helped Merkel become chancellor", Spiegel Online International, 8 July 2009

- ^ "Helmut Kohl". Club of Madrid. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ "Ailing former German chancellor Helmut Kohl marries", Daily Times, 14 May 2008

- ^ Former German Chancellor in Hospital: Concerns Grow Over Helmut Kohl's Health, Der Spiegel, 21 May 2008

- ^ "Weakened Helmut Kohl appears in public after operation", The Local, 9 May 2009

- ^ Kohl, Bush, Gorbachev remember Cold War in Berlin, AFP, 31 October 2009

- ^ Helmut Kohl, Germany's "Chancellor of Unity," turns 80, Monsters and Critics, 3 April 2010

- ^ Gall bladder surgery on Kohl, Bunte

- ^ "Kohl has heart surgery to tackle health problems", The Local, 4 September 2012

- ^ Hans Traxler wird 80, Der Erfinder der "Birne", Taz, 20 May 2009

- ^ Birne auf Breitwand, Dreharbeiten zu "Helmut Kohl – Der Film", Sueddeutsche Zeitung 05.10.2008

- ^ "Vienna European Council, 11 and 12 December 1998, Presidency Conclusions". European Council. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ Williams, Jennifer (31 August 1998). "Kohl's honorary degree 'an affirmation of healing'" (PDF). BrandeisReporter.

- ^ "Bundesverdienstkreuz mit Lorbeerkranz für Kohl" (in German). Rhein-Zeitung. 26 October 1998.

- ^ "Bill Clinton pays tribute to former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 16 May 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

External links

- Use dmy dates from March 2013

- All articles with faulty authority control information

- Helmut Kohl

- 1930 births

- Chancellors of Germany

- Christian Democratic Union (Germany) politicians

- Cold War leaders

- Conservatism in Germany

- German anti-communists

- German military personnel of World War II

- German Roman Catholics

- Grand Order of Queen Jelena recipients

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion

- Living people

- Members of the Bundestag

- Members of the Landtag of Rhineland-Palatinate

- People from Ludwigshafen

- People from the Palatinate

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Presidents of the European Council

- Recipients of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Recipients of the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana, 1st Class

- Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland)

- University of Heidelberg alumni