New Horizons: Difference between revisions

bloppy Benis Tag: nonsense characters |

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 98.179.148.129 to version by Bibcode Bot. Report False Positive? Thanks, ClueBot NG. (3131872) (Bot) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{About|the space probe|other uses|New Horizons (disambiguation)}} |

|||

bENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENISbENISBENISBENISBENIS |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=June 2017}} |

|||

{{italic title}} |

|||

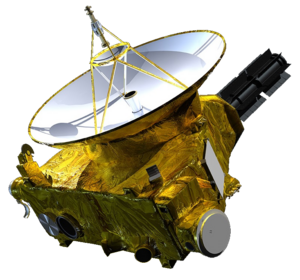

{{Infobox spaceflight |

|||

| name = ''New Horizons'' |

|||

| image = New Horizons Transparent.png |

|||

| image_caption = ''New Horizons'' space probe |

|||

| image_size = 300px |

|||

| insignia = New Horizons - Logo2 big.png |

|||

| insignia_size = 150x150px |

|||

| mission_type = Flyby ([[Jupiter]]{{dot}}[[Pluto]]{{dot}}{{mpl|2014 MU|69}}) |

|||

| operator = [[NASA]] |

|||

| COSPAR_ID = 2006-001A |

|||

| SATCAT = 28928 |

|||

| website = {{URL|http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/}} <br /> {{URL|1=https://www.nasa.gov/newhorizons/|2=nasa.gov/newhorizons}} |

|||

| mission_duration = Primary mission: 9.5 years <br /> <small>Elapsed: {{Age in years, months and days|2006|01|19}}</small> |

|||

| manufacturer = [[Applied Physics Laboratory|APL]]{{\}}[[Southwest Research Institute|SwRI]] |

|||

| launch_mass = {{cvt|478|kg|lb}} |

|||

| dry_mass = {{cvt|401|kg|lb}} |

|||

| payload_mass = {{cvt|30.4|kg|lb}} |

|||

| dimensions = {{cvt|2.2|xx|2.1|xx|2.7|m|ft}} |

|||

| power = 228 watts |

|||

| launch_date = {{start-date|January 19, 2006, 19:00}} UTC |

|||

| launch_rocket = [[Atlas V]] 551 |

|||

| launch_site = [[Cape Canaveral Air Force Station|Cape Canaveral]] [[Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 41|SLC-41]] |

|||

| launch_contractor = [[United Launch Alliance]] |

|||

| disposal_type = <!--deorbited, decommissioned, placed in a graveyard orbit, etc--> |

|||

| deactivated = <!--when craft was decommissioned--> |

|||

| last_contact = <!--when last signal received if not decommissioned--> |

|||

| orbit_eccentricity = 1.41905 |

|||

| orbit_inclination = 2.23014° |

|||

| orbit_RAAN = 225.016° |

|||

| orbit_arg_periapsis = 293.445° |

|||

| orbit_epoch = January 1, 2017 ([[Julian day|JD]] 2457754.5)<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/horizons.cgi |title=HORIZONS Web-Interface |publisher=NASA/JPL |accessdate=July 25, 2016}} To find results, change Target Body to "New Horizons" and change Time Span to include "2017-01-01".</ref> |

|||

|interplanetary = |

|||

{{Infobox spaceflight/IP |

|||

|type = flyby |

|||

|object = {{ats|132524|APL}} |

|||

|note = incidental |

|||

|distance = {{cvt|101867|km|mi}} |

|||

|arrival_date = June 13, 2006, 04:05 UTC |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Infobox spaceflight/IP |

|||

|type = flyby |

|||

|object = [[Jupiter]] |

|||

|note = gravity assist |

|||

|distance = {{cvt|2300000|km|mi}} |

|||

|arrival_date = February 28, 2007, 05:43:40 UTC |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Infobox spaceflight/IP |

|||

|type = flyby |

|||

|object = [[Pluto]] |

|||

|distance = {{cvt|12500|km|mi}} |

|||

|arrival_date = July 14, 2015, 11:49:57 UTC |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Infobox spaceflight/IP |

|||

|type = flyby |

|||

|object = {{mpl|486958|2014 MU|69}} |

|||

|arrival_date = January 1, 2019 (planned) |

|||

|distance = |

|||

}} |

|||

| instruments_list = {{Infobox spaceflight/Instruments |

|||

|acronym1 = Alice |name1 = Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrometer |

|||

|acronym2 = LORRI |name2 = Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager |

|||

|acronym3 = SWAP |name3 = Solar Wind at Pluto |

|||

|acronym4 = PEPSSI |name4 = Pluto Energetic Particle Spectrometer Science Investigation |

|||

|acronym5 = REX |name5 = Radio Science Experiment |

|||

|acronym6 = Ralph |name6 = Ralph Telescope |

|||

|acronym7 = SDC |name7 = Venetia Burney Student Dust Counter |

|||

}} |

|||

| programme = '''[[New Frontiers program]]''' |

|||

| previous_mission = |

|||

| next_mission = ''[[Juno (spacecraft)|Juno]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

'''''New Horizons''''' is an interplanetary [[space probe]] that was launched as a part of [[NASA]]'s [[New Frontiers program]].<ref name="NYT-20150718">{{cite news |last=Chang |first=Kenneth |title=The Long, Strange Trip to Pluto, and How NASA Nearly Missed It |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/19/us/the-long-strange-trip-to-pluto-and-how-nasa-nearly-missed-it.html |date=July 18, 2015 |work=[[New York Times]] |accessdate=July 19, 2015}}</ref> Engineered by the [[Johns Hopkins University]] [[Applied Physics Laboratory]] (APL) and the [[Southwest Research Institute]] (SwRI), with a team led by [[Alan Stern|S. Alan Stern]],<ref name="tri">{{cite podcast |url=https://twit.tv/shows/triangulation/episodes/215 |title=Alan Stern: principal investigator for New Horizons |website=[[TWiT.tv]] |publisher=[[TWiT.tv]] |host=[[Leo Laporte]] |date=August 31, 2015 |access-date=September 1, 2015}}</ref> the spacecraft was launched in 2006 with the primary mission to perform a [[Planetary flyby|flyby]] study of the [[Pluto]] system in 2015, and a secondary mission to fly by and study one or more other [[Kuiper belt]] objects (KBOs) in the decade to follow.<ref name="nhtp">{{cite web |url=http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/newhorizons/main/ |title=New Horizons to Pluto, Mission Website |publisher=US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) |date=July 2, 2015 |accessdate=July 7, 2015}}</ref><ref name="NYT-20150713">{{cite news |last=Chang |first=Kenneth |title=A Close-Up for Pluto After Spacecraft's 3-Billion-MileTrip |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/14/science/a-close-up-for-pluto-after-spacecrafts-3-billion-mile-trip.html |date=July 13, 2015 |work=[[New York Times]] |accessdate=July 13, 2015}}</ref><ref name="NYT-20150706">{{cite news |last=Chang |first=Kenneth |title=Almost Time for Pluto's Close-Up |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/07/science/space/almost-time-for-plutos-close-up.html |date=July 6, 2015 |work=[[New York Times]] |accessdate=July 6, 2015}}</ref><ref name="NYT-20150706-db">{{cite news |last=Overbye |first=Dennis |authorlink=Dennis Overbye |title=Reaching Pluto, and the End of an Era of Planetary Exploration |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/07/science/space/reaching-pluto-and-the-end-of-an-era-of-planetary-exploration.html |date=July 6, 2015 |work=[[New York Times]] |accessdate=July 7, 2015}}</ref><ref name="NYT-20150828">{{cite news |last=Roston |first=Michael |title=NASA's Next Horizon in Space |url=https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/08/25/science/space/nasa-next-mission.html |date=August 28, 2015 |work=[[New York Times]] |accessdate=August 28, 2015}}</ref> It is the [[List of artificial objects leaving the Solar System|fifth of five artificial objects]] to achieve the [[escape velocity]] that will allow them to [[Solar System#Farthest regions|leave the Solar System]]. |

|||

On January 19, 2006, ''New Horizons'' was launched from [[Cape Canaveral Air Force Station]] directly into an Earth-and-solar [[Escape velocity|escape trajectory]] with a speed of about {{convert|16.26|km/s|km/h mph|0|abbr=out|sp=us}}. After a brief encounter with asteroid [[132524 APL]], ''New Horizons'' proceeded to [[Jupiter]], making its closest approach on February 28, 2007, at a distance of {{convert|2.3|e6km|abbr=off|sp=us}}. The Jupiter flyby provided a [[gravity assist]] that increased ''New Horizons''{{'}} speed; the flyby also enabled a general test of ''New Horizons''{{'}} scientific capabilities, returning data about [[Atmosphere of Jupiter|the planet's atmosphere]], [[Moons of Jupiter|moons]], and [[Magnetosphere of Jupiter|magnetosphere]]. |

|||

Most of the post-Jupiter voyage was spent in hibernation mode to preserve on-board systems, except for brief annual checkouts.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/index.php |title=New Horizons: NASA's Mission to Pluto |work=NASA |accessdate=April 15, 2015}}</ref> On December 6, 2014, ''New Horizons'' was brought back online for the Pluto encounter, and instrument check-out began.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20141206 |title=New Horizons - News |work=Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory |date=December 6, 2014 |accessdate=April 15, 2015}}</ref> On January 15, 2015, the ''New Horizons'' spacecraft began its approach phase to Pluto. |

|||

On July 14, 2015, at 11:49 [[UTC]], it flew {{cvt|12500|km}} above the surface of Pluto,<ref name="NYT-20150714-kc">{{cite news |last=Chang |first=Kenneth |title=NASA's New Horizons Spacecraft Completes Flyby of Pluto |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/15/science/space/nasa-new-horizons-spacecraft-reaches-pluto.html |date=July 14, 2015 |work=[[The New York Times]] |accessdate=July 14, 2015}}</ref><ref name="AP-20150714">{{cite news |last=Dunn |first=Marcia |title=Pluto close-up: Spacecraft makes flyby of icy, mystery world |url=http://apnews.excite.com/article/20150714/us-sci--pluto-1a20f848e7.html |date=July 14, 2015 |work=[[Excite]] |agency=Associated Press (AP) |accessdate=July 14, 2015}}</ref> making it the first spacecraft to explore the dwarf planet.<ref name="NYT-20150706-db" /><ref name="NASA-20150714-kn">{{cite web |last1=Brown |first1=Dwayne |last2=Cantillo |first2=Laurie |last3=Buckley |first3=Mike |last4=Stotoff |first4=Maria |title=15-149 NASA's Three-Billion-Mile Journey to Pluto Reaches Historic Encounter |url=http://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasas-three-billion-mile-journey-to-pluto-reaches-historic-encounter |date=July 14, 2015 |work=[[NASA]] |accessdate=July 14, 2015}}</ref> On October 25, 2016, at 21:48 UTC, the last of the recorded data from the Pluto flyby was received from ''New Horizons''.<ref name="NYT-20161028">{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/29/science/pluto-nasa-new-horizons.html |title=No More Data From Pluto |work=[[The New York Times]] |last=Chang |first=Kenneth |date=October 28, 2016 |accessdate=October 28, 2016}}</ref> Having completed its flyby of Pluto,<ref name="NYT-20151211-rj">{{cite news |last=Jayawardhana |first=Ray |title=Give It Up for Pluto |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/13/opinion/give-it-up-for-pluto.html |date=December 11, 2015 |work=[[New York Times]] |accessdate=December 11, 2015}}</ref> ''New Horizons'' has maneuvered for a flyby of Kuiper belt object {{mpl|486958|2014 MU|69}},<ref name="NASA-20150828-tt">{{cite web |last=Talbert |first=Tricia |title=NASA's New Horizons Team Selects Potential Kuiper Belt Flyby Target |url=http://www.nasa.gov/feature/nasa-s-new-horizons-team-selects-potential-kuiper-belt-flyby-target |date=August 28, 2015 |work=[[NASA]] |accessdate=September 4, 2015}}</ref><ref name="SP-20150828">{{cite web |last1=Cofield |first1=Calla |title=Beyond Pluto: 2nd Target Chosen for New Horizons Probe |url=http://www.space.com/30415-new-horizons-pluto-mission-next-target.html |date=August 28, 2015 |work=[[Space.com]] |accessdate=August 30, 2015}}</ref><ref name="AP-20151022">{{cite news |last=Dunn |first=Marcia |title=NASA's New Horizons on new post-Pluto mission |url=http://apnews.excite.com/article/20151022/us-sci--pluto-next_stop-3b1bf3f8fc.html |date=October 22, 2015 |work=[[AP News]] |accessdate=October 25, 2015}}</ref> expected to take place on January 1, 2019, when it will be 43.4 [[Astronomical unit|AU]] from the Sun.<ref name="NASA-20150828-tt" /><ref name="SP-20150828" /> |

|||

{{clear|left}} |

|||

== History == |

|||

{{main article|Exploration of Pluto}} |

|||

[[File:USPS Pluto Stamp - October 1991.jpg|thumb|right|[[USPS]] stamp issued in 1991 that served as motivation for planetary scientists to send a probe to Pluto]] |

|||

[[File:New horizons (NASA).jpg|thumb|right|Early concept art of the ''New Horizons'' spacecraft. The mission, led by the [[Applied Physics Laboratory]] and [[Alan Stern]], would become the first mission to Pluto successfully funded and launched, after years of delays and cancellations.]] |

|||

In August 1992, [[Jet Propulsion Laboratory|JPL]] scientist Robert Staehle called Pluto discoverer [[Clyde Tombaugh]], requesting permission to visit his planet. "I told him he was welcome to it," Tombaugh later remembered, "though he's got to go one long, cold trip."<ref name="Sobel1993">{{cite magazine |url=http://discovermagazine.com/1993/may/thelastworld215 |title=The Last World |magazine=[[Discover (magazine)|Discover]] |first=Dava |last=Sobel |date=May 1993 |accessdate=April 13, 2007}}</ref> The call eventually led to a series of proposed Pluto missions, leading up to ''New Horizons''. |

|||

Stamatios "Tom" Krimigis, head of the [[Applied Physics Laboratory]]'s space division, one of many entrants in the New Frontiers Program competition, formed the ''New Horizons'' team with Alan Stern in December 2000. Appointed as the project's [[principal investigator]], Stern was described by Krimigis as "the personification of the Pluto mission".<ref name="alan-stern">{{cite web |last1=Hand |first1=Eric |title=Feature: How Alan Stern's tenacity, drive, and command got a NASA spacecraft to Pluto |url=http://news.sciencemag.org/people-events/2015/06/feature-how-alan-stern-s-tenacity-drive-and-command-got-nasa-spacecraft-pluto |website=[[Science (journal)|Science]] |publisher=[[American Association for the Advancement of Science]] |date=June 25, 2015 |accessdate=July 8, 2015}}</ref> ''New Horizons'' was based largely on Stern's work since ''Pluto 350'' and involved most of the team from ''Pluto Kuiper Express''.<ref name="newhorizonsbook">[[Alan Stern|Stern, Alan]]; {{cite book |last1=Christopher |first1=Russell |title=New Horizons: Reconnaissance of the Pluto-Charon System and the Kuiper Belt |date=2009 |publisher=[[Springer Publishing]] |isbn=978-0-387-89518-5 |pages=6, 7 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oZfpYIUKDrUC&pg |accessdate=July 8, 2015}}</ref> The ''New Horizons'' proposal was one of five that were officially submitted to NASA. It was later selected as one of two finalists to be subject to a three-month concept study, in June 2001. The other finalist, POSSE (Pluto and Outer Solar System Explorer), was a separate, but similar Pluto mission concept by the [[University of Colorado Boulder]], led by principal investigator [[Larry W. Esposito]], and supported by the JPL, [[Lockheed Martin]] and the [[University of California]].<ref name="new-frontiers-finalists">{{cite news |last1=Savage |first1=Donald |url=http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/text/pluto_pr_20010606.txt |title=NASA Selects Two Investigations for Pluto-Kuiper Belt Mission Feasibility Studies |publisher=[[NASA|National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)]] |date=June 6, 2001 |accessdate=July 9, 2015 |archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/6ZsBVxTQw |archivedate=July 9, 2015 |deadurl=no}}</ref> However, the APL, in addition to being supported by ''Pluto Kuiper Express'' developers at the Goddard Space Flight Center and [[Stanford University]],<ref name="new-frontiers-finalists"/> were at an advantage; they had recently developed ''NEAR Shoemaker'' for NASA, which had successfully entered orbit around [[433 Eros]] earlier in the year, and would later land on the asteroid to scientific and engineering fanfare.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Savage |first1=Donald |title=NEAR Shoemaker's Historic Landing on Eros Exceeds Science, Engineering Expectations |url=https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/news/display.cfm?News_ID=683 |website=[[NASA|National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)]] |date=February 14, 2001 |accessdate=July 8, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

In November 2001, ''New Horizons'' was officially selected for funding as part of the New Frontiers program.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Savage |first1=Donald |url=http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/text/pluto_pr_20011129.txt |title=NASA Selects Pluto-Kuiper Belt Mission Phase B Study |publisher=[[NASA|National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)]] |date=November 29, 2001 |accessdate=July 9, 2015 |archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/6ZsCefQyx |archivedate=July 9, 2015 |deadurl=no}}</ref> However, the new NASA Administrator appointed by the [[Presidency of George W. Bush|Bush Administration]], [[Sean O'Keefe]], was not supportive of ''New Horizons'', and effectively cancelled it by not including it in NASA's budget for 2003. NASA's Associate Administrator for the Science Mission Directorate [[Ed Weiler]] prompted Stern to lobby for the funding of ''New Horizons'' in hopes of the mission appearing in the [[Planetary Science Decadal Survey]]; a prioritized "wish list", compiled by the [[United States National Research Council]], that reflects the opinions of the scientific community. After an intense campaign to gain support for ''New Horizons'', the Planetary Science Decadal Survey of 2003–2013 was published in the summer of 2002. ''New Horizons'' topped the list of projects considered the highest priority among the scientific community in the medium-size category; ahead of missions to the Moon, and even Jupiter. Weiler stated that it was a result that "[his] administration was not going to fight".<ref name="alan-stern"/> Funding for the mission was finally secured following the publication of the report, and Stern's team were finally able to start building the spacecraft and its instruments, with a planned launch in January 2006 and arrival at Pluto in 2015.<ref name="alan-stern"/> Alice Bowman became Mission Operations Manager.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.jhuapl.edu/employment/meet/bowman.asp |title=Alice Bowman: APL's First Female MOM |publisher=Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory |access-date=April 11, 2016}}</ref> |

|||

==Mission profile== |

|||

[[File:15-011a-NewHorizons-PlutoFlyby-ArtistConcept-14July2015-20150115.jpg|thumb|left|upright|Artist's impression of ''New Horizons''{{'}} [[#Pluto system encounter|close encounter with the Pluto–Charon system]].]] |

|||

''New Horizons'' is the first mission in NASA's New Frontiers mission category, larger and more expensive than the Discovery missions but smaller than the Flagship Program. The cost of the mission (including spacecraft and instrument development, launch vehicle, mission operations, data analysis, and education/public outreach) is approximately $700 million over 15 years (2001–2016).<ref>{{Cite journal |url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexknapp/2015/07/14/how-do-new-horizons-costs-compare-to-other-space-missions/ |date=July 14, 2015 |title=How Do New Horizons Costs Compare To Other Space Missions? |first=Alex |last=Knapp |magazine=[[Forbes]]}}</ref> The spacecraft was built primarily by [[Southwest Research Institute]] (SwRI) and the [[Johns Hopkins University|Johns Hopkins]] Applied Physics Laboratory. The mission's principal investigator is Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (formerly NASA Associate Administrator). |

|||

After separation from the launch vehicle, overall control was taken by Mission Operations Center (MOC) at the Applied Physics Laboratory in [[Howard County, Maryland]]. The science instruments are operated at Clyde Tombaugh Science Operations Center (T-SOC) in [[Boulder, Colorado]].<ref name="DoSS">{{cite web |title=Departments of Space Studies & Space Operations |work=Southwest Research Institute Planetary Science Directorate website |publisher=Southwest Research Institute |url=http://www.boulder.swri.edu/swri_boulder_2009a.pdf |accessdate=March 14, 2010}}</ref> Navigation is performed at various contractor facilities, whereas the navigational positional data and related celestial reference frames are provided by the [[United States Naval Observatory Flagstaff Station|Naval Observatory Flagstaff Station]] through Headquarters NASA and [[JPL]]; [[KinetX]] is the lead on the ''New Horizons'' navigation team and is responsible for planning trajectory adjustments as the spacecraft speeds toward [[Solar System#Trans-Neptunian region|the outer Solar System]]. Coincidentally the Naval Observatory Flagstaff Station was where the photographic plates were taken for the discovery of Pluto's moon [[Charon (moon)|Charon]]; and the Naval Observatory is itself not far from the [[Lowell Observatory]] where Pluto was discovered. |

|||

''New Horizons'' was originally planned as a voyage to the only unexplored planet in the Solar{{space}}System. When the spacecraft was launched, Pluto was still classified as a [[planet]], later to be [[IAU definition of planet|reclassified]] as a dwarf planet by the [[International Astronomical Union]] (IAU). Some members of the ''New Horizons'' team, including Alan Stern, disagree with the IAU definition and still describe Pluto as the ninth planet.<ref>{{cite web |title=Unabashedly Onward to the Ninth Planet |work=New Horizons website |url=http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/overview/piPerspective.php?page=piPerspective_09_06_2006. |publisher=Johns Hopkins/APL |accessdate=October 25, 2008 |archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/5x3rrNEcY |archivedate=March 9, 2011 |deadurl=no}}</ref> Pluto's satellites [[Nix (moon)|Nix]] and [[Hydra (moon)|Hydra]] also have a connection with the spacecraft: the first letters of their names (N and H) are the initials of ''New Horizons''. The moons' discoverers chose these names for this reason, plus Nix and Hydra's relationship to the mythological [[Pluto (mythology)|Pluto]].<ref>{{Cite press release |title=Pluto's Two Small Moons Christened Nix and Hydra |work=New Horizons website |publisher=Johns Hopkins APL |url=http://www.jhuapl.edu/newscenter/pressreleases/2006/060622.asp |accessdate=October 25, 2008 |archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/5x3rrTZyz |archivedate=March 9, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

In addition to the science equipment, there are several cultural artifacts traveling with the spacecraft. These include a collection of 434,738 names stored on a compact disc,<ref>{{cite web |title=Send Your Name to Pluto |work=New Horizons website |publisher=Johns Hopkins APL |url=http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/spacecraft/searchName.php |accessdate=January 30, 2009 |archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/5x3rrdwvd |archivedate=March 9, 2011 |deadurl=no}}</ref> a piece of [[Scaled Composites]]'s ''[[SpaceShipOne]]'',<ref>{{Cite news |title=Pluto Mission to Carry Piece of SpaceShipOne |date=December 20, 2005 |work=Space.com |url=http://www.space.com/astronotes/astronotes.html |archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/5x3rsWTNq |archivedate=March 9, 2011 |deadurl=no}}</ref> a "Not Yet Explored" USPS stamp,<ref name="stamp-betz">{{cite web |last1=Betz |first1=Eric |title=Postage for Pluto: A 29-cent stamp pissed off scientists so much they tacked it to New Horizons |url=http://www.astronomy.com/year-of-pluto/2015/06/postage-for-pluto-a-29-cent-stamp-pissed-off-scientists-enough-they-tacked-it-to-new-horizons |website=[[Astronomy (magazine)|Astronomy]] |publisher=[[Kalmbach Publishing]] |date=June 26, 2015 |accessdate=July 8, 2015}}</ref><ref name="stamp-070715">{{cite web |title='Not Yet Explored' no more: New Horizons flying Pluto stamp to dwarf planet |url=http://www.collectspace.com/news/news-070715a-newhorizons-pluto-explored-stamp.html |website=[[collectSPACE]] |publisher=Robert Pearlman |date=July 7, 2015 |accessdate=July 8, 2015}}</ref> and a [[Flag of the United States]], along with other mementos.<ref>{{Cite news |title=To Pluto, With Postage |date=October 28, 2008 |work=collectSPACE |url=http://www.collectspace.com/news/news-102808a.html |archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/5x3rsr1Ur |archivedate=March 9, 2011 |deadurl=no}}</ref> |

|||

About {{convert|1|oz|g|sigfig=1|order=flip}} of Clyde Tombaugh's ashes are aboard the spacecraft, to commemorate his discovery of Pluto in 1930.<ref>{{cite news |title=New Horizons launches on voyage to Pluto and beyond |url=http://www.spaceflightnow.com/atlas/av010/060119launch.html |work=spaceFlightNow |date=January 19, 2006 |accessdate=December 1, 2010 |archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/5x3rtPlke |archivedate=March 9, 2011 |deadurl=no}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.collectspace.com/news/news-102808a.html |title=To Pluto, with postage: Nine mementos fly with NASA's first mission to the last planet |publisher=collectSPACE |date= |accessdate=October 29, 2013}}</ref> A Florida-[[50 State Quarters|state quarter]] coin, whose design commemorates human exploration, is included, officially as a trim weight.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/newhorizons/main/fl_quarter.html |title=NASA - A 'State' of Exploration |publisher=Nasa.gov |date=March 8, 2006 |accessdate=October 29, 2013}}</ref> One of the science packages (a dust counter) is named after [[Venetia Burney]], who, as a child, suggested the name "Pluto" after its discovery. |

|||

== Goal == |

|||

[[File:15-150-NasaTeam-NewHorizonsCallsHomeAfterPlutoFlyby-20150714.jpg|thumb|right|View of Mission Operations at the [[Applied Physics Laboratory]] in [[Laurel, Maryland]] (July 14, 2015).]] |

|||

The goal of the mission is to understand the formation of the Pluto system, the Kuiper belt, and the transformation of the early Solar System.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/files/AGU-NH-Workshop.pdf |title=The Everest of Planetary Exploration: New Horizons Explores The Pluto System 2015 |format=PowerPoint Presentation |work=NASA |accessdate=April 15, 2015}}</ref> The spacecraft collected data on the atmospheres, surfaces, interiors, and environments of Pluto and its moons. It will also study other objects in the Kuiper belt.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/missions/profile.cfm?MCode=PKB |title=Solar System Exploration - New Horizons |work=NASA |date=February 27, 2015 |accessdate=April 15, 2015}}</ref> "By way of comparison, ''New Horizons'' gathered 5,000 times as much data at Pluto as [[Mariner program|Mariner]] did at the [[Mars|Red Planet]]."<ref>[http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-33440926 New Horizons: Pluto map shows 'whale' of a feature] by Jonathan Amos, on July 8, 2015 ([[BBC]] - Science & Environment section)</ref> |

|||

Some of the questions the mission attempts to answer are: What is Pluto's atmosphere made of and how does it behave? What does its surface look like? Are there large geological structures? How do [[solar wind]] particles interact with Pluto's atmosphere?<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/newhorizons/spacecraft/index.html |title=New Horizons Spacecraft and Instruments |work=NASA |date=November 10, 2014 |accessdate=April 15, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

Specifically, the mission's science objectives are to:<ref>{{cite web |url=http://discoverynewfrontiers.nasa.gov/missions/missions_nh.cfml |title=New Frontiers Program: New Horizons Science Objectives |work=NASA - New Frontiers Program |accessdate=April 15, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

*map the surface composition of Pluto and [[Charon (moon)|Charon]] |

|||

*characterize the geology and morphology of Pluto and Charon |

|||

*characterize the neutral [[atmosphere of Pluto]] and its escape rate |

|||

*search for an atmosphere around Charon |

|||

*map surface temperatures on Pluto and Charon |

|||

*search for rings and additional satellites around Pluto |

|||

*conduct similar investigations of one or more [[Kuiper belt]] objects |

|||

== Design and construction == |

|||

=== Spacecraft subsystems === |

|||

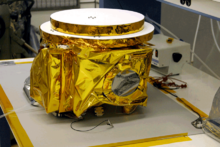

[[File:New Horizons 1.jpg|thumb|''New Horizons'' at [[Kennedy Space Center]] in 2005]] |

|||

The spacecraft is comparable in size and general shape to a [[grand piano]] and has been compared to a piano glued to a cocktail bar-sized satellite dish.<ref name="Moore-2010"/> As a point of departure, the team took inspiration from the [[Ulysses probe|Ulysses]] spacecraft,<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Fountain |first1=G. H. |last2=Kusnierkiewicz |first2=D. Y. |last3=Hersman |first3=C. B. |last4=Herder |first4=T. S. |last5=Coughlin |first5=T. B. |last6=Gibson |first6=W. C. |last7=Clancy |first7=D. A. |last8=Deboy |first8=C. C. |last9=Hill |first9=T. A. | last10=Kinnison |first10=J. D. |last11=Mehoke |first11=D. S. |last12=Ottman |first12=G. K. |last13=Rogers |first13=G. D. |last14=Stern |first14=S. A. |last15=Stratton |first15=J. M. |last16=Vernon |first16=S. R. |last17=Williams |first17=S. P. |title=The New Horizons Spacecraft |arxiv=0709.4288 |doi=10.1007/s11214-008-9374-8 |journal=Space Science Reviews |volume=140 |pages=23 |year=2008 |pmid= |pmc= |bibcode=2008SSRv..140...23F}}</ref> which also carried a [[radioisotope thermoelectric generator]] (RTG) and dish on a box-in-box structure through the outer Solar System. Many subsystems and components have flight heritage from APL's [[CONTOUR]] spacecraft, which in turn had heritage from APL's [[TIMED]] spacecraft. |

|||

''New Horizons''{{'}} body forms a triangle, almost {{cvt|2.5|ft|m|order=flip}} thick. (The ''Pioneers'' have [[hexagon]]al bodies, whereas the [[Voyager program|''Voyagers'']], ''Galileo'', and ''[[Cassini–Huygens]]'' have [[decagon]]al, hollow bodies.) A [[7075 aluminium alloy]] tube forms the main structural column, between the launch vehicle adapter ring at the "rear," and the {{cvt|2.1|m}} radio [[dish antenna]] affixed to the "front" flat side. The [[titanium]] fuel tank is in this tube. The RTG attaches with a 4-sided titanium mount resembling a gray pyramid or stepstool. Titanium provides strength and thermal isolation. The rest of the triangle is primarily sandwich panels of thin aluminium facesheet (less than {{cvt|1/64|in|mm|2|disp=or}}) bonded to aluminium honeycomb core. The structure is larger than strictly necessary, with empty space inside. The structure is designed to act as [[Radiation hardening|shielding]], reducing electronics [[Single event upset|errors caused by radiation]] from the RTG. Also, the mass distribution required for a spinning spacecraft demands a wider triangle. |

|||

The interior structure is painted black to equalize temperature by [[Thermal radiation|radiative]] heat transfer. Overall, the spacecraft is thoroughly blanketed to retain heat. Unlike the ''Pioneers'' and ''Voyagers'', the radio dish is also enclosed in blankets that extend to the body. The heat from the RTG adds warmth to the spacecraft while it is in the outer Solar System. While in the inner Solar System, the spacecraft must prevent overheating, hence electronic activity is limited, power is diverted to [[Shunt (electrical)|shunts]] with attached radiators, and [[louver]]s are opened to radiate excess heat. While the spacecraft is cruising inactively in the cold outer Solar System, the louvers are closed, and the shunt regulator reroutes power to electric [[resistor|heaters]]. |

|||

==== Propulsion and attitude control ==== |

|||

''New Horizons'' has both spin-stabilized (cruise) and three-axis stabilized (science) modes controlled entirely with [[hydrazine]] [[Monopropellant rocket|monopropellant]]. Additional post launch [[delta-v]] of over {{cvt|290|m/s|km/h mph}} is provided by a {{cvt|77|kg}} internal tank. Helium is used as a pressurant, with an [[elastomer]]ic diaphragm assisting expulsion. The spacecraft's on-orbit mass including fuel is over {{cvt|470|kg}} on the Jupiter flyby trajectory, but would have been only {{cvt|445|kg}} for the backup direct flight option to Pluto. Significantly, had the backup option been taken, this would have meant less fuel for later Kuiper belt operations. |

|||

There are 16 [[reaction control system|thrusters]] on ''New Horizons'': four {{cvt|4.4|N|lbf|1|lk=on}} and twelve {{cvt|0.9|N|lbf|1}} plumbed into redundant branches. The larger thrusters are used primarily for trajectory corrections, and the small ones (previously used on ''Cassini'' and the ''Voyager'' spacecraft) are used primarily for [[attitude control]] and spinup/spindown maneuvers. Two star cameras are used to measure the spacecraft attitude. They are mounted on the face of the spacecraft and provide attitude information while in spin-stabilized or 3-axis mode. In between the time of star camera readings, spacecraft orientation is provided by dual redundant [[miniature inertial measurement unit]]s. Each unit contains three solid-state [[gyroscope]]s and three [[accelerometer]]s. Two Adcole [[Attitude control#Sun sensor|Sun sensor]]s provide attitude determination. One detects the angle to the Sun, whereas the other measures spin rate and clocking. |

|||

==== Power ==== |

|||

[[File:RTG and New Horizons in background.jpg|thumb|upright|''New Horizons''{{'}} [[Radioisotope thermoelectric generator|RTG]]]] |

|||

A cylindrical [[radioisotope thermoelectric generator]] (RTG) protrudes in the plane of the triangle from one vertex of the triangle. The RTG provided {{val|245.7|ul=W}} of power at launch, and was predicted to drop approximately 5% every 4{{space}}years, decaying to {{val|200|u=W}} by the time of its encounter with the [[Plutonian system]] in 2015 and will decay too far to power the transmitters in the 2030s.<ref name="tri"/> There are no onboard batteries. RTG output is relatively predictable; load transients are handled by a capacitor bank and fast circuit breakers. |

|||

The RTG, model "[[GPHS-RTG]]," was originally a spare from the ''Cassini'' mission. The RTG contains {{cvt|9.75|kg|lb}} of [[plutonium-238]] oxide pellets.<ref name="newhorizonsbook"/> Each pellet is clad in [[iridium]], then encased in a graphite shell. It was developed by the U.S. [[United States Department of Energy|Department of Energy]] at the Materials and Fuels Complex, a part of the [[Idaho National Laboratory]].<ref>{{Cite news |first=Steven |last=Friederich |title=Argonne Lab is developing battery for NASA missions |date=December 16, 2003 |publisher=Idaho State Journal |url=http://www.journalnet.com/articles/2003/12/16/news/local/news02.txt |archiveurl=http://www.matr.net/article-9139.html |archivedate=December 17, 2003}}</ref> |

|||

The original RTG design called for {{cvt|10.9|kg|lb}} of plutonium, but a unit less powerful than the original design goal was produced because of delays at the United States Department of Energy, including security activities, that delayed plutonium production.<ref name=radioshow>{{cite web |last1=Betts |first1=Bruce |title=Planetary Radio trivia question at 38m28s |url=http://www.planetary.org/multimedia/planetary-radio/show/2015/0728-the-royal-observatory-greenwich-quest-for-longitude.html |website=The Planetary Society |accessdate=August 7, 2015}}</ref> The mission parameters and observation sequence had to be modified for the reduced wattage; still, not all instruments can operate simultaneously. The Department of Energy transferred the space battery program from Ohio to Argonne in 2002 because of security concerns. |

|||

The amount of radioactive plutonium in the RTG is about one-third the amount on board the Cassini–Huygens probe when it launched in 1997. That Cassini launch was protested by some. The United States Department of Energy estimated the chances of a New Horizons launch accident that would release radiation into the atmosphere at 1 in 350, and monitored the launch<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,181880,00.html |title=Pluto Probe Launch Scrubbed for Tuesday |work=Fox News |date=January 18, 2006 |archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/5x3s2FqQW |archivedate=March 9, 2011}}</ref> as it always does when RTGs are involved. It was estimated that a worst-case scenario of total dispersal of on-board plutonium would spread the equivalent radiation of 80% the average annual dosage in North America from background radiation over an area with a radius of {{cvt|105|km}}.<ref>{{cite web |title=Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the New Horizons Mission |url=http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/overview/deis/docs/NH_DEIS_Full.pdf |publisher=Johns Hopkins APL |accessdate=May 16, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141113230746/http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/overview/deis/docs/NH_DEIS_Full.pdf |archive-date=November 13, 2014 |format=pdf}}</ref> |

|||

==== Flight computer ==== |

|||

The spacecraft carries two [[computer]] systems: the Command and Data Handling system and the Guidance and Control processor. Each of the two systems is duplicated for [[Redundancy (engineering)|redundancy]], for a total of four computers. The processor used for its flight computers is the [[Mongoose-V]], a 12 [[Megahertz|MHz]] radiation-hardened version of the [[R3000|MIPS R3000]] [[Central processing unit|CPU]]. Multiple redundant clocks and timing routines are implemented in hardware and software to help prevent faults and downtime. To conserve heat and mass, spacecraft and instrument electronics are housed together in IEMs (integrated electronics modules). There are two redundant IEMs. Including other functions such as instrument and radio electronics, each IEM contains 9{{space}}boards.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/Mission/Spacecraft/Systems-and-Components.php |title=New Horizons |work=jhuapl.edu}}</ref> The software of the probe runs on [[Nucleus RTOS]] operating system.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Voica |first1=Alexandru |title=MIPS in space: Inside NASA's New Horizons mission to Pluto |url=http://blog.imgtec.com/mips-processors/mips-in-space-inside-nasa-new-horizons-mission-to-pluto |website=Imagination}}</ref> |

|||

There have been two "safing" events, that sent the spacecraft into [[safe mode (spacecraft)|safe mode]]: |

|||

* On March 19, 2007 the Command and Data Handling computer experienced an uncorrectable memory error and rebooted itself, causing the spacecraft to go into safe mode. The craft fully recovered within two days, with some data loss on Jupiter's [[magnetotail]]. No impact on the subsequent mission was expected.<ref>{{cite web |title=The PI's Perspective: Trip Report |url=http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/PI-Perspectives.php?page=piPerspective_3_26_2007 |date=March 27, 2007 |accessdate=August 5, 2009 |publisher=NASA/Johns Hopkins University/APL/New Horizons Mission |archivedate=March 9, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

* On July 4, 2015 there was a CPU safing event caused by over assignment of commanded science operations.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.latimes.com/science/sciencenow/la-sci-sn-pluto-encounter-mode-20150706-story.html |title=Computer glitch doesn't stop New Horizons: Pluto encounter almost a week away |author=Los Angeles Times |date=July 6, 2015 |work=latimes.com |accessdate=July 13, 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.space.com/29853-new-horizons-glitch-pluto-flyby.html |title=Pluto Probe Suffers Glitch 10 Days Before Epic Flyby |work=Space.com |accessdate=July 13, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

==== Telecommunications and data handling ==== |

|||

[[File:New Horizons - REX.jpeg|thumb|''New Horizons''{{'}} [[Antenna (radio)|antennas]]]] |

|||

Communication with the spacecraft is via [[X band]]. The craft had a communication rate of {{val|38|u=kbit/s}} at Jupiter; at Pluto's distance, a rate of approximately {{val|1|ul=kbit/s}} per transmitter is expected. Besides the low data rate, Pluto's distance also causes a [[Latency (engineering)|latency]] of about 4.5 hours (one-way). The {{cvt|70|m|adj=on|sp=us}} [[NASA Deep Space Network]] (DSN) dishes are used to relay commands once it is beyond Jupiter. The spacecraft uses [[dual modular redundancy]] transmitters and receivers, and either right- or left-hand [[circular polarization]]. The downlink signal is amplified by dual redundant 12-watt [[traveling-wave tube]] amplifiers (TWTAs) mounted on the body under the dish. The receivers are new, low-power designs. The system can be controlled to power both TWTAs at the same time, and transmit a dual-polarized downlink signal to the DSN that nearly doubles the downlink rate. DSN tests early in the mission with this dual polarization combining technique were successful, and the capability is now considered operational (when the spacecraft power budget permits both TWTAs to be powered). |

|||

In addition to the [[high-gain antenna]], there are two backup low-gain antennas and a medium-gain dish. The high-gain dish has a [[Cassegrain reflector]] layout, composite construction, and a {{convert|2.1|m|ft|0|adj=on|sp=us}} diameter providing over {{val|42|ul=dBi}} of gain, has a half-power beam width of about a degree. The prime-focus, medium-gain antenna, with a {{convert|0.3|m|ft|0|adj=on|sp=us}} aperture and 10° half-power beam width, is mounted to the back of the high-gain antenna's secondary reflector. The forward low-gain antenna is stacked atop the feed of the medium-gain antenna. The aft low-gain antenna is mounted within the launch adapter at the rear of the spacecraft. This antenna was used only for early mission phases near Earth, just after launch and for emergencies if the spacecraft had lost attitude control. |

|||

''New Horizons'' recorded scientific instrument data to its solid-state memory buffer at each encounter, then transmitted the data to Earth. Data storage is done on two low-power [[Flash memory|solid-state recorders]] (one primary, one backup) holding up to {{val|8|ul=gigabyte}}s each. Because of the extreme distance from Pluto and the Kuiper belt, only one buffer load at those encounters can be saved. This is because ''New Horizons'' will require approximately 16 months after it has left the vicinity of Pluto to transmit the buffer load back to Earth.<ref name="JHU APL News Center 20150414">{{cite web |title=NASA's New Horizons Nears Historic Encounter with Pluto |url=http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20150414 |date=April 14, 2015 |publisher=The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory LLC |accessdate=June 27, 2015}}</ref> At Pluto's distance, transmissions from the space probe back to Earth took four hours and 25 minutes to traverse 4.7 billion km of space.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Rincon |first1=Paul |title=New Horizons: Spacecraft survives Pluto encounter |url=http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-33531811 |publisher=BBC |date=July 15, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

Part of the reason for the delay between the gathering of and transmission of data is that all of the ''New Horizons'' instrumentation is body-mounted. In order for the cameras to record data, the entire probe must turn, and the one-degree-wide beam of the high-gain antenna was not pointing toward Earth. Previous spacecraft, such as the ''Voyager'' program probes, had a rotatable instrumentation platform (a "scan platform") that could take measurements from virtually any angle without losing radio contact with Earth. ''New Horizons''{{'}} elimination of excess mechanisms was implemented to save weight, shorten the schedule, and improve reliability during its 15-year lifetime. |

|||

The ''Voyager 2'' spacecraft experienced platform jamming at Saturn; the demands of long time exposures at Uranus led to modifications of the mission such that the entire probe was rotated to make the time exposure photos at Uranus and Neptune, similar to how ''New Horizons'' rotated. |

|||

=== Science payload === |

|||

''New Horizons'' carries seven instruments: three optical instruments, two plasma instruments, a dust sensor and a radio science receiver/radiometer. The instruments are to be used to investigate the global geology, surface composition, surface temperature, atmospheric pressure, atmospheric temperature and escape rate of Pluto and its moons. The rated power is {{val|21|u=watts}}, though not all instruments operate simultaneously.<ref>{{Cite journal |author=Y. Guo |author2=R. W. Farquhar |journal=[[Acta Astronautica]] |volume=58 |issue=10 |date=2006 |pages=550–559 |doi=10.1016/j.actaastro.2006.01.012 |title=Baseline design of New Horizons mission to Pluto and the Kuiper belt |url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094576506000294 |bibcode=2006AcAau..58..550G}}</ref> In addition, ''New Horizons'' has an Ultrastable Oscillator subsystem, which may be used to study and test the [[Pioneer anomaly]] towards the end of the spacecraft's life.<ref>{{Cite journal |author=M.M. Nieto |journal=Physics Letters B |volume=659 |issue=3 |date=2008 |pages=483–485 |doi=10.1016/j.physletb.2007.11.067 |title=New Horizons and the onset of the Pioneer anomaly |bibcode=2008PhLB..659..483N |arxiv=0710.5135}}</ref> |

|||

==== Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) ==== |

|||

[[File:New Horizons LORRI.jpg|thumb|LORRI—long-range camera]] |

|||

The Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) is a long-focal-length imager designed for high resolution and responsivity at visible wavelengths. The instrument is equipped with a 1024×1024 pixel by 12-bits-per-pixel monochromatic [[Charge-coupled device|CCD]] imager with a {{cvt|208.3|mm|in}} aperture giving a resolution of 5{{space}}[[microradian|μrad]] (~1{{space}}[[arcsecond|arcsec]]).<ref name=jhuapl-lorri>{{cite web |title=About LORRI Images |url=http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/soc/lorri_about.html |publisher=The Johns Hopkins University - Applied Physics Laboratory}}</ref> The CCD is chilled far below freezing by a passive radiator on the antisolar face of the spacecraft. This temperature differential requires insulation, and isolation from the rest of the structure. The [[Ritchey-Chrétien telescope|Ritchey–Chretien]] mirrors and metering structure are made of [[silicon carbide]], to boost stiffness, reduce weight, and prevent warping at low temperatures. The optical elements sit in a composite light shield, and mount with titanium and fiberglass for thermal isolation. Overall mass is {{cvt|8.6|kg}}, with the optical tube assembly (OTA) weighing about {{cvt|5.6|kg}},<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.boulder.swri.edu/pkb/ssr/ssr-lorri.pdf |title=Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager on New Horizons |first=A. F. |last=Cheng |display-authors=etal |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090709151428/http://www.boulder.swri.edu/pkb/ssr/ssr-lorri.pdf |archivedate=July 9, 2009 |deadurl=no}}</ref> for one of the largest silicon-carbide telescopes flown at the time (now surpassed by [[Herschel Space Observatory|Herschel]]). For viewing on public web sites the 12-bit per pixel LORRI images are converted to 8-bit per pixel [[JPEG]] images.<ref name=jhuapl-lorri/> These public images do not contain the full [[dynamic range]] of brightness information available from the raw LORRI images files.<ref name=jhuapl-lorri/> |

|||

:{{small|''Principal investigator: Andy Cheng, [[Applied Physics Laboratory]]''}}, {{small|''Data: LORRI image search at jhuapl.edu''<ref>{{cite web |url=http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/Multimedia/Science-Photos/search.php?form_keywords=60 |title=Science Photos: LORRI |work=JHUAPL.edu |access-date=May 2, 2015}}</ref>}} |

|||

==== Solar Wind At Pluto (SWAP) ==== |

|||

[[File:New Horizons SWAP.jpg|thumb|SWAP—Solar Wind At Pluto]] |

|||

Solar Wind At Pluto (SWAP) is a toroidal [[electrostatic analyzer]] and retarding potential analyzer (RPA), that makes up one of the two instruments comprising ''New Horizons''{{'}} [[Plasma (physics)|Plasma]] and high-energy particle spectrometer suite (PAM), the other being PEPSSI. SWAP measures particles of up to 6.5{{space}}keV and, because of the tenuous solar wind at Pluto's distance, the instrument is designed with the largest [[aperture]] of any such instrument ever flown.{{citation needed|date=July 2015}} |

|||

:{{small|''Principal investigator: David McComas, [[Southwest Research Institute]]''}} |

|||

==== Pluto Energetic Particle Spectrometer Science Investigation (PEPSSI) ==== |

|||

Pluto Energetic Particle Spectrometer Science Investigation (PEPSSI) is a [[time-of-flight mass spectrometry|time of flight]] [[ion]] and [[electron]] sensor that makes up one of the two instruments comprising ''New Horizons''{{'}} plasma and high-energy particle spectrometer suite (PAM), the other being SWAP. Unlike SWAP, which measures particles of up to 6.5{{space}}keV, PEPSSI goes up to 1{{space}}MeV.{{citation needed|date=July 2015}} |

|||

:{{small|''Principal investigator: Ralph McNutt Jr., Applied Physics Laboratory''}} |

|||

==== Alice ==== |

|||

''Alice'' is an [[ultraviolet]] imaging [[spectrometer]] that is one of two photographic instruments comprising ''New Horizons''{{'}} Pluto Exploration Remote Sensing Investigation (PERSI); the other being the ''Ralph'' telescope. It resolves 1,024{{space}}wavelength bands in the far and extreme ultraviolet (from 50–{{val|180|ul=nm}}), over 32{{space}}view fields. Its goal is to determine the composition of Pluto's atmosphere. This Alice instrument is derived from another Alice aboard [[European Space Agency|ESA]]'s [[Rosetta space probe#Nucleus|Rosetta]] spacecraft.{{citation needed|date=July 2015}} |

|||

:{{small|''Principal investigator: Alan Stern, Southwest Research Institute''}} |

|||

==== Ralph telescope ==== |

|||

[[File:New Horizons - Ralph.png|thumb|''Ralph''—telescope and color camera]] |

|||

The ''Ralph'' telescope, {{cvt|6|cm}} in aperture, is one of two photographic instruments that make up ''New Horizons''{{'}} Pluto Exploration Remote Sensing Investigation (PERSI), with the other being the Alice instrument. ''Ralph'' has two separate channels: MVIC (Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera), a visible-light [[Charge-coupled device|CCD]] imager with broadband and color channels; and LEISA (Linear Etalon Imaging Spectral Array), a near-[[infrared]] imaging spectrometer. LEISA is derived from a similar instrument on the [[Earth Observing-1]] spacecraft. ''Ralph'' was named after Alice's husband on ''[[The Honeymooners]]'', and was designed after Alice.<ref name="sn20150711">{{cite news |url=http://spacenews.com/new-horizons-about-to-bring-an-unknown-world-into-sharp-focus/ |title=Meet Ralph, the New Horizons Camera Bringing Pluto into Sharp Focus |work=Space News |last1=David |first1=Leonard |date=July 11, 2015 |accessdate=July 16, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

On June 23, 2017, NASA announced that it has renamed the LEISA instrument to the "Lisa Hardaway Infrared Mapping Spectrometer" in honor of [[Lisa Hardaway]], the ''Ralph'' program manager at [[Ball Aerospace & Technologies|Ball Aerospace]], who died in January 2017 at age 50.<ref name="nasa20170623">{{cite web |url=https://www.nasa.gov/feature/nasa-s-new-horizons-mission-honors-memory-of-engineer-lisa-hardaway |title=NASA’s New Horizons Mission Honors Memory of Engineer Lisa Hardaway |publisher=NASA |editor-first=Lillian |editor-last=Gipson |date=June 23, 2017 |accessdate=June 27, 2017}}</ref> |

|||

:{{small|''Principal investigator: Alan Stern, Southwest Research Institute''}} |

|||

==== Venetia Burney Student Dust Counter (VBSDC) ==== |

|||

[[File:New Horizons sdc.jpeg|thumb|VBSDC—Venetia Burney Student Dust Counter]] |

|||