Tower Bridge: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 2 edits by 79.255.140.125 using STiki |

GeoffreyBH (talk | contribs) m Link to description of BHA Cromwell House ~~~~ |

||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

The entire hydraulic system along with the gas lighting system was installed by William Sugg & Co Ltd., the well known Westminster gas engineers. The gas lighting was initially by open flame burners within the lanterns but soon after was updated to the later incandescent system.<ref>[http://www.williamsugghistory.co.uk Sugg history website]</ref> |

The entire hydraulic system along with the gas lighting system was installed by William Sugg & Co Ltd., the well known Westminster gas engineers. The gas lighting was initially by open flame burners within the lanterns but soon after was updated to the later incandescent system.<ref>[http://www.williamsugghistory.co.uk Sugg history website]</ref> |

||

In 1974, the original operating mechanism was largely replaced by a new electro-hydraulic drive system, designed by BHA Cromwell House. The only components of the original system still in use are the final pinions, which engage with the racks fitted to the bascules. These are driven by modern [[hydraulic motor]]s and gearing, using oil rather than water as the [[hydraulic fluid]].<ref>{{cite web | last =Hartwell | first =Geoffrey | title =Tower Bridge, London | url =http://www.hartwell.demon.co.uk/tbpic.htm | accessdate =27 February 2007 }}</ref> Some of the original [[hydraulic machinery]] has been retained, although it is no longer in use. It is open to the public and forms the basis for the bridge's museum, which resides in the old engine rooms on the south side of the bridge. The museum includes the steam engines, two of the accumulators and one of the hydraulic engines that moved the bascules, along with other related artefacts. |

In 1974, the original operating mechanism was largely replaced by a new electro-hydraulic drive system, designed by [http://www.arbitrator-engineer-gbh.co.uk/#!firm/c1n8o BHA Cromwell House]. The only components of the original system still in use are the final pinions, which engage with the racks fitted to the bascules. These are driven by modern [[hydraulic motor]]s and gearing, using oil rather than water as the [[hydraulic fluid]].<ref>{{cite web | last =Hartwell | first =Geoffrey | title =Tower Bridge, London | url =http://www.hartwell.demon.co.uk/tbpic.htm | accessdate =27 February 2007 }}</ref> Some of the original [[hydraulic machinery]] has been retained, although it is no longer in use. It is open to the public and forms the basis for the bridge's museum, which resides in the old engine rooms on the south side of the bridge. The museum includes the steam engines, two of the accumulators and one of the hydraulic engines that moved the bascules, along with other related artefacts. |

||

====Third steam engine==== |

====Third steam engine==== |

||

Revision as of 11:10, 27 September 2014

51°30′20″N 0°04′32″W / 51.50556°N 0.07556°W

Tower Bridge | |

|---|---|

Tower Bridge, aerial view | |

| Coordinates | 51°30′20″N 0°04′31″W / 51.5055°N 0.075406°W |

| Carries | A100 Tower Bridge Road |

| Crosses | River Thames |

| Locale | London boroughs: – north side: Tower Hamlets – south side: Southwark |

| Maintained by | Bridge House Estates |

| Heritage status | Grade I listed structure |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Bascule bridge, suspension bridge |

| Total length | 244 metres (801 ft) |

| Longest span | 61 metres (200 ft) |

| Clearance below | 8.6 metres (28 ft) (closed) 42.5 metres (139 ft) (open) (mean high water spring tide) |

| History | |

| Opened | 30 June 1894 |

| Location | |

| |

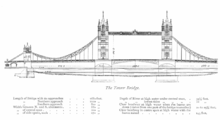

Tower Bridge (built 1886–1894) is a combined bascule and suspension bridge in London which crosses the River Thames. It is close to the Tower of London, from which it takes its name, and has become an iconic symbol of London.

The bridge consists of two towers tied together at the upper level by means of two horizontal walkways, designed to withstand the horizontal forces exerted by the suspended sections of the bridge on the landward sides of the towers. The vertical component of the forces in the suspended sections and the vertical reactions of the two walkways are carried by the two robust towers. The bascule pivots and operating machinery are housed in the base of each tower. The bridge's present colour scheme dates from 1977, when it was painted red, white and blue for Queen Elizabeth II's silver jubilee. Originally it was painted a mid greenish-blue colour.[1]

The nearest London Underground station is Tower Hill on the Circle and District lines, and the nearest Docklands Light Railway station is Tower Gateway.[2]

History

In the second half of the 19th century, increased commercial development in the East End of London led to a requirement for a new river crossing downstream of London Bridge. A traditional fixed bridge could not be built because it would cut off access by tall-masted ships to the port facilities in the Pool of London, between London Bridge and the Tower of London.

A Special Bridge or Subway Committee was formed in 1877, chaired by Sir Albert Joseph Altman, to find a solution to the river crossing problem. It opened the design of the crossing to public competition. Over 50 designs were submitted, including one from civil engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette. The evaluation of the designs was surrounded by controversy, and it was not until 1884 that a design submitted by Sir Horace Jones, the City Architect (who was also one of the judges),[3] was approved.

Jones' engineer, Sir John Wolfe Barry, devised the idea of a bascule bridge with two towers built on piers. The central span was split into two equal bascules or leaves, which could be raised to allow river traffic to pass. The two side-spans were suspension bridges, with the suspension rods anchored both at the abutments and through rods contained within the bridge's upper walkways.

Opening

The bridge was officially opened on 30 June 1894 by The Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII), and his wife, The Princess of Wales (Alexandra of Denmark).[4]

The bridge connected Iron Gate, on the north bank of the river, with Horselydown Lane, on the south – now known as Tower Bridge Approach and Tower Bridge Road, respectively.[5] Until the bridge was opened, the Tower Subway – 400 m to the west – was the shortest way to cross the river from Tower Hill to Tooley Street in Southwark. Opened in 1870, Tower Subway was among the world's earliest underground ('tube') railway, but closed after just three months and was re-opened as a pedestrian foot tunnel. Once Tower Bridge was open, the majority of foot traffic transferred to using the bridge, there being no toll to pay to use it. Having lost most of its income, the tunnel was closed in 1898.[6]

Tower Bridge is one of five London bridges now owned and maintained by the Bridge House Estates, a charitable trust overseen by the City of London Corporation. It is the only one of the Trust's bridges not to connect the City of London to the Southwark bank, the northern landfall being in Tower Hamlets.

Construction

Construction started in 1886 and took eight years with five major contractors – Sir John Jackson (foundations), Baron Armstrong (hydraulics), William Webster, Sir H.H. Bartlett, and Sir William Arrol & Co.[7] – and employed 432 construction workers. E W Crutwell was the resident engineer for the construction.[5]

Two massive piers, containing over 70,000 tons of concrete,[3] were sunk into the riverbed to support the construction. Over 11,000 tons of steel provided the framework for the towers and walkways.[3] This was then clad in Cornish granite and Portland stone, both to protect the underlying steelwork and to give the bridge a pleasing appearance.

Jones died in 1887 and George D. Stevenson took over the project.[3] Stevenson replaced Jones's original brick façade with the more ornate Victorian Gothic style, which makes the bridge a distinctive landmark, and was intended to harmonise the bridge with the nearby Tower of London.[5] The total cost of construction was £1,184,000[5] (£Format price error: cannot parse value "Error when using {{Inflation}}: |end_year=2024 (parameter 4) is greater than the latest available year (2023) in index "UK"." as of 2024).[8]

Design

The bridge is 800 feet (244 m) in length with two towers each 213 feet (65 m) high, built on piers. The central span of 200 feet (61 m) between the towers is split into two equal bascules or leaves, which can be raised to an angle of 86 degrees to allow river traffic to pass. The bascules, weighing over 1,000 tons each, are counterbalanced to minimise the force required and allow raising in five minutes.

The two side-spans are suspension bridges, each 270 feet (82 m) long, with the suspension rods anchored both at the abutments and through rods contained within the bridge's upper walkways. The pedestrian walkways are 143 feet (44 m) above the river at high tide.[5]

Hydraulic system

at Forncett Industrial Steam Museum

The original raising mechanism was powered by pressurised water stored in several hydraulic accumulators.[9] The system was designed and installed by Hamilton Owen Rendel[10] while working for Sir W. G. Armstrong Mitchell & Company of Newcastle upon Tyne. Water, at a pressure of 750 psi (5.2 MPa), is pumped into the accumulators by two 360 hp (270 kW) stationary steam engines, each driving a force pump from its piston tail rod. The accumulators each comprise a 20 inches (51 cm) ram on which sits a very heavy weight to maintain the desired pressure.

The entire hydraulic system along with the gas lighting system was installed by William Sugg & Co Ltd., the well known Westminster gas engineers. The gas lighting was initially by open flame burners within the lanterns but soon after was updated to the later incandescent system.[11]

In 1974, the original operating mechanism was largely replaced by a new electro-hydraulic drive system, designed by BHA Cromwell House. The only components of the original system still in use are the final pinions, which engage with the racks fitted to the bascules. These are driven by modern hydraulic motors and gearing, using oil rather than water as the hydraulic fluid.[12] Some of the original hydraulic machinery has been retained, although it is no longer in use. It is open to the public and forms the basis for the bridge's museum, which resides in the old engine rooms on the south side of the bridge. The museum includes the steam engines, two of the accumulators and one of the hydraulic engines that moved the bascules, along with other related artefacts.

Third steam engine

During World War II, as a precaution against the existing engines being damaged by enemy action, a third engine was installed in 1942:[13] a 150 hp horizontal cross-compound engine, built by Vickers Armstrong Ltd. at their Elswick works in Newcastle upon Tyne. It was fitted with a flywheel having a 9-foot (2.7 m) diameter and weighing 9 tons, and was governed to a speed of 30 rpm.[13] The engine became redundant when the rest of the system was modernised in 1974, and was donated to the Forncett Industrial Steam Museum by the Corporation of the City of London.[13]

Navigation control

To control the passage of river traffic through the bridge, a number of different rules and signals were employed. Daytime control was provided by red semaphore signals, mounted on small control cabins on either end of both bridge piers. At night, coloured lights were used, in either direction, on both piers: two red lights to show that the bridge was closed, and two green to show that it was open. In foggy weather, a gong was sounded as well.[5]

Vessels passing through the bridge had to display signals too: by day, a black ball at least 2 feet (0.61 m) in diameter was to be mounted high up where it could be seen; by night, two red lights in the same position. Foggy weather required repeated blasts from the ship's steam whistle.[5]

If a black ball was suspended from the middle of each walkway (or a red light at night) this indicated that the bridge could not be opened. These signals were repeated about 1,000 yards (910 m) downstream, at Cherry Garden Pier, where boats needing to pass through the bridge had to hoist their signals/lights and sound their horn, as appropriate, to alert the Bridge Master.[5]

When needing to be raised for the passage of a vessel the bascules are only raised to an angle sufficient for the vessel to safely pass under the bridge, except in the case of a vessel with the Monarch on board in which case they are raised fully no matter the size of the vessel.

Some of the control mechanism for the signalling equipment has been preserved and may be seen working in the bridge's museum.

Reaction

Although the bridge is an undoubted landmark, professional commentators in the early 20th century were critical of its aesthetics. "It represents the vice of tawdriness and pretentiousness, and of falsification of the actual facts of the structure", wrote H. H. Statham,[14] while Frank Brangwyn stated that "A more absurd structure than the Tower Bridge was never thrown across a strategic river".[15]

Architectural historian Dan Cruickshank selected the bridge as one of his four choices for the 2002 BBC television documentary series Britain's Best Buildings.[16]

Mistaken identity

Tower Bridge is often[according to whom?] mistaken for London Bridge,[17] the next bridge upstream. A popular urban legend is that in 1968, Robert McCulloch, the purchaser of the old London Bridge that was later shipped to Lake Havasu City, Arizona, believed that he was in fact buying Tower Bridge. This was denied by McCulloch himself and has been debunked by Ivan Luckin, the vendor of the bridge.[18]

Traffic

- Road

Tower Bridge is still a busy and vital crossing of the Thames: it is crossed by over 40,000 people (motorists, cyclists and pedestrians) every day.[20] The bridge is on the London Inner Ring Road, and is on the eastern boundary of the London congestion charge zone. (Drivers do not incur a charge by crossing the bridge.)

To maintain the integrity of the structure, the City of London Corporation has imposed a 20 miles per hour (32 km/h) speed restriction, and an 18 tonne weight limit on vehicles using the bridge. A camera system measures the speed of traffic crossing the bridge, utilising a number plate recognition system to send fixed penalty charges to speeding drivers.[21]

A second system monitors other vehicle parameters. Induction loops and piezoelectric sensors are used to measure the weight, the height of the chassis above ground level, and the number of axles of each vehicle.[21]

- River

The bascules are raised around 1000 times a year.[22] River traffic is now much reduced, but it still takes priority over road traffic. Today, 24 hours' notice is required before opening the bridge. There is no charge for vessels.

A computer system was installed in 2000 to control the raising and lowering of the bascules remotely. It proved unreliable, resulting in the bridge being stuck in the open or closed positions on several occasions during 2005 until its sensors were replaced.[20]

Tower Bridge Exhibition and the tower walkways

The high-level open air walkways between the towers gained an unpleasant reputation as a haunt for prostitutes and pickpockets; as they were only accessible by stairs they were seldom used by regular pedestrians, and were closed in 1910. In 1982 they were reopened as part of the Tower Bridge Exhibition, a display housed in the bridge's twin towers, the high-level walkways and the Victorian engine rooms. The exhibition charges an admission fee. It uses films, photos and interactive displays to explain why and how Tower Bridge was built. Visitors can access the original steam engines that once powered the bridge bascules, housed in a building close to the south end of the bridge.

2008–2012 facelift

In April 2008 it was announced that the bridge would undergo a 'facelift' costing £4 million, and taking four years to complete. The work entailed stripping off the existing paint down to bare metal and repainting in blue and white. Each section was enshrouded in scaffolding and plastic sheeting to prevent the old paint falling into the Thames and causing pollution. Starting in mid-2008, contractors worked on a quarter of the bridge at a time to minimise disruption, but some road closures were inevitable. It is intended that the completed work will stand for 25 years.[23]

The renovation of the walkway interior was completed in mid-2009. Within the walkways a versatile new lighting system has been installed, designed by Eleni Shiarlis, for when the walkways are in use for exhibitions or functions. The new system provides for both feature and atmospheric lighting, the latter using bespoke RGB LED luminares, designed to be concealed within the bridge superstructure and fixed without the need for drilling (these requirements as a result of the bridge's Grade I status).[24]

The renovation of the four suspension chains was completed in March 2010 using a state-of-the-art coating system requiring up to six different layers of 'paint'.[25]

London 2012 Olympics and Paralympics

The bridge featured in publicity for the 2012 Summer Olympics being held in London. In June 2012 a set of Olympic rings was suspended from the bridge to mark one month to go until the start of the games. The rings cost £259,817 to make, measured 25 by 11.5 metres (82 by 38 ft) and weighed 13 tonnes (14 short tons).[26]

On 9 June 2012 an AgustaWestland AW-139 (G-OLYM) flew three times through Tower Bridge while being filmed from a second helicopter for a segment of the opening ceremony entitled Happy and Glorious.[27]

Professional footballer David Beckham piloted a dramatically illuminated Bladerunner BR RIB35X sportsboat, carrying the female footballer Jade Bailey and the Olympic Torch at the bow, under the raised bascules of the bridge during the ceremony. As they transited the crossing, fireworks exploded from the bridge.[28][29]

On 8 July 2012, the west walkway was transformed into a 200 foot long Live Music Sculpture by the British composer Samuel Bordoli. 30 classical musicians were arranged along the length of the bridge 42 metres above the Thames behind the Olympic rings. The sound travelled backwards and forwards along the walkway, echoing the structure of bridge.[30][31]

Following the Olympics, the rings were removed from Tower Bridge and replaced by the emblem of the Paralympic Games for the 2012 Summer Paralympics.[32]

Incidents

In December 1952, the bridge opened while a number 78 double-decker bus (stock number RT 793, registration plate JXC 156) was crossing from the south bank. At that time, the gateman would ring a warning bell and close the gates when the bridge was clear before the watchman ordered the raising of the bridge. The process failed while a relief watchman was on duty. The bus was near the edge of the south bascule when it started to rise; driver Albert Gunter made a split-second decision to accelerate, clearing a 3 ft gap to drop 6 ft onto the north bascule, which had not yet started to rise. There were no serious injuries.[33][34] Gunter was given 10 pounds (worth roughly 243 pounds in modern money) by the City Corporation to honour his act of bravery.[35]

The Hawker Hunter Tower Bridge incident occurred on 5 April 1968 when a Royal Air Force Hawker Hunter FGA.9 jet fighter from No. 1 Squadron, flown by Flt Lt Alan Pollock, flew through Tower Bridge. Unimpressed that senior staff were not going to celebrate the RAF's 50th birthday with a fly-past, Pollock decided to do something himself. Without authorisation, Pollock flew the Hunter at low altitude down the Thames, past the Houses of Parliament, and continued on toward Tower Bridge. He flew the Hunter beneath the bridge's walkway, remarking afterwards that it was an afterthought when he saw the bridge looming ahead of him. Pollock was placed under arrest upon landing, and discharged from the RAF on medical grounds without the chance to defend himself at a court martial.[36][37]

In summer 1973 a single-engined Beagle Pup was twice flown under the pedestrian walkway of Tower Bridge by 29-year-old stockbroker's clerk Paul Martin. Martin was on bail following accusations of stockmarket fraud. He then "buzzed" buildings in The City, before flying north towards the Lake District where he died when his aircraft crashed some two hours later.[38]

In May 1997,[39] the motorcade of United States President Bill Clinton was divided by the opening of the bridge. The Thames sailing barge Gladys, on her way to a gathering at St Katharine Docks, arrived on schedule and the bridge was duly opened for her. Returning from a Thames-side lunch at Le Pont de la Tour restaurant, with British Prime Minister Tony Blair, President Clinton was less punctual, and arrived just as the bridge was rising. The bridge opening split the motorcade in two, much to the consternation of security staff. A spokesman for Tower Bridge is quoted as saying, "We tried to contact the American Embassy, but they wouldn't answer the phone."[40]

On 19 August 1999, Jef Smith, a Freeman of the City of London, drove a flock of two sheep across the bridge. He was exercising a claimed ancient permission, granted as a right to Freemen, to make a point about the powers of older citizens and the way in which their rights were being eroded.[41]

Before dawn on 31 October 2003, David Crick, a Fathers 4 Justice campaigner, climbed a 100 ft (30 m) tower crane near Tower Bridge at the start of a six-day protest dressed as Spider-Man.[42] Fearing for his safety, and that of motorists should he fall, police cordoned off the area, closing the bridge and surrounding roads and causing widespread traffic congestion across the City and east London. At the time, the building contractor Taylor Woodrow Construction Ltd. was in the midst of constructing a new office tower known as "K2". The Metropolitan Police were later criticised for maintaining the closure for five days when this was not strictly necessary in the eyes of some citizens.[43][44]

On 11 May 2009, six people were trapped and injured after a lift fell 10 ft (3 m) inside the north tower.[45][46]

-

A time lapse video of Tower Bridge

-

A Short Sunderland of No. 201 Squadron RAF moored at Tower Bridge during the 1956 commemoration of the Battle of Britain

Replicas

- Tower Bridge, Suzhou, China

See also

- Historic places adjacent to Tower Bridge

References

- ^ Patrick Baty. "Tower Bridge, London. A Report on the Paint Following an Examination of a Number of Surfaces." 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Tower Bridge Exhibition website". Corporation of The City of London. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d Roberts, Chris, "Cross River Traffic", Granta, 2005

- ^ John Eade (22 July 1976). "Where Thames Smooth Waters Glide". Thames.me.uk. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h

"Tower Bridge". Archive – the Quarterly Journal for British Industrial and Transport History (3). Lightmoor Press: p47. 1994. ISSN 1352-7991.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Smith, Denis (2001). Civil Engineering Heritage: London and the Thames Valley. Thomas Telford. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-7277-2876-8.

- ^ The Times, 2 July 1894

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "Bridge History". Towerbridge.org.uk. 1 February 2003. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ Lane, MR (1989). The Rendel Connection: a dynasty of engineers. Quiller press, London. ISBN 1-870948-01-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Sugg history website

- ^ Hartwell, Geoffrey. "Tower Bridge, London". Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ^ a b c "The Tower Bridge Engine". Forncett Industrial Steam Museum. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ^ Statham, H.H., "Bridge Engineering", Wiley, 1916.

- ^ Brangwyn, F., and Sparrow, W. S., "A Book of Bridges", John Lane, 1920.

- ^ Cruickshank, Dan. "Choosing Britain's Best Buildings". BBC History. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ^ Jason Cochran, Pauline Frommer (2007). Pauline Frommer's London. Frommer's. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-470-05228-0. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ "How London Bridge was sold to the States (From This Is Local London)". Thisislocallondon.co.uk. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ Fleet | Sail Royal Greenwich

- ^ a b "Fix to stop bridge getting stuck". BBC News. 17 January 2006. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ^ a b Speed Check Services. "Bridge Protection Scheme" (PDF). Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ "Bridge Lifts". Tower Bridge Official Website. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ^ "Tower Bridge to get £4m facelift". BBC News. 7 April 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ^ "Tower Bridge lighting". Interior Event & Exhibition Lighting Design scheme. ES Lighting Design. 29 April 2009. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ^ "Tower Bridge restored to true colours". Tower Bridge Restoration Website. 10 March 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Olympics rings Tower over London, Mail Online, accessed 29 July 2012.

- ^ Extraordinary moment two helicopters dived dramatically low under Tower Bridge to film Bond themed sequence for Olympic opening ceremony, Mail Online, 10 June 2012.

- ^ Olympics 2012: David Beckham brings Torch on speedboat, BBC News, accessed 29 July 2012.

- ^ Motorboats Monthly, accessed 10 August 2012.

- ^ "Tower Bridge is London's Latest Venue - Classic FM Music News and Features". Classicfm.com. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "Tower Bridge as a musical instrument". Classical-Music.com. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ Topping, Alexandra (13 August 2012). "London 2012: let the Paralympics preparations begin". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ "Tower Bridge, London, UK". BBC. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "The Jumping Bus". Time. 12 January 1953. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008.

- ^ Car Journals. "Mind The Gap When Jumping Over Tower Bridge". Car Journals. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ^ p.157, Shaw, Michael 'No.1 Squadron', Ian Allan 1986

- ^ "Hawker Hunter History". (scroll down half-way). Thunder & Lightnings. 29 February 2004. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ^ "Gives Suicide Plan To Crash Plane Into Tower Of London, Dies In Crash 240 Miles Away". Lundington Daily News. 1 August 1973. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Presidential visits abroad". (William J. Clinton III). US Department of State. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ^ Shore, John (July 1997). "Gladys takes the rise out of Bill". Regatta Online. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ^ "Protest Freeman herds sheep over Tower Bridge". BBC News. 19 August 1999. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ^ "Spiderman protest closes Tower Bridge". BBC News. 31 October 2003. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ^ "Spiderman cordon criticised". BBC News. 3 November 2003. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ^ "'Spiderman' cleared over protest". BBC News. 14 May 2004. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ^ "Six injured after Tower Bridge lift plummets 30ft", The Times, 11 May 2009.

- ^ "Six injured in Tower Bridge lift", BBC News, 11 May 2009.

External links

- Official Tower Bridge Exhibition website

- Winchester, Clarence, ed. (1938). "Building the Tower Bridge". Wonders of World Engineering. London: Amalgamated Press. pp. 575–580. Describes the construction of Tower Bridge

- Bascule bridges

- Bridges across the River Thames

- Bridges completed in 1894

- Grade I listed bridges

- Grade I listed buildings in London

- Museums in Southwark

- Museums in Tower Hamlets

- Steam museums in London

- Suspension bridges in the United Kingdom

- Technology museums in the United Kingdom

- Tower of London

- Transport in Tower Hamlets

- Transport in Southwark

- Visitor attractions in London

- Visitor attractions in Tower Hamlets

- Privately owned public spaces