History of the Jews in Russia

The vast territories of the Russian Empire at one time hosted the largest Jewish population in the world. Within these territories the Jewish community flourished and developed many of modern Judaism's most distinctive theological and cultural traditions, while also facing periods of intense antisemitic discriminatory policies and persecutions. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, many Soviet Jews took advantage of liberalized emigration policies, with over half their population leaving, most for Israel and the United States. Despite this, the Jews in Russia and the nations of the former Soviet Union constitute one of the larger Jewish populations in Europe.

Early history

Tradition places Jews in southern Russia, Ukraine, Armenia, and Georgia since before the days of the First Temple, and records exist from the 4th century showing that there were Armenian cities possessing Jewish populations ranging from 10,000 to 30,000 along with substantial Jewish settlements in the Crimea. Under the influence of these Jewish communities, Bulan, the Khagan Bek of the Khazars, and the ruling classes of Khazaria adopted Judaism at some point in the mid-to-late 8th or early 9th centuries. After the overthrow of the Khazarian kingdom by Sviatoslav I of Kiev (969), Jews in large numbers fled to the Crimea, the Caucasus, and the Russian principality of Kiev which was formerly a part of the Khazar territory. In the 11th and 12th centuries the Jews appear to have occupied in Kiev a separate quarter, called the Jewish town ("Zhidove", i.e. "The Jews"), the gates probably leading to which were known as the Jewish gates ("Zhidovskiye vorota"). The Kievan community was oriented towards Byzantium (the Romaniotes), Babylonia and Palestine in the tenth and eleventh centuries, but appears to have been increasingly open to the European Ashkenazim from the twelfth century on. Few products of Kievan Jewish intellectual activity are extant, however. Other communities, or groups of individuals, are known from Chernigov and, probably, Volodymyr-Volynskyi. At that time Jews are found also in northeastern Russia, in the domains of Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky (1169-1174), although it is uncertain to which degree they were living there permanently.

Though Russia had few Jews, countries just to its west had rapidly growing Jewish populations, as waves of anti-Jewish pogroms and expulsions from the countries of Western Europe marked the last centuries of the Middle Ages, a sizable portion of the Jewish populations there moved to the more tolerant countries of Central and Eastern Europe, as well as the Middle East.

Expelled en masse from England, France, Spain and most other Western European countries at various times, and persecuted in Germany in the 14th century, many Western European Jews naturally accepted Polish ruler Casimir III's invitation to settle in Polish-controlled areas of Eastern Europe as a third estate, performing commercial, middleman services in an agricultural society for the Polish king and nobility between 1330 and 1370, during Casimir the Great's reign. Approximately 85 percent of the Jews in Poland during the 14th century were involved in estate management, tax and toll collecting, moneylending or trade.

After settling in Poland (later Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) and Hungary (later Austria-Hungary), the population expanded into the lightly populated areas of Ukraine and Lithuania, which were to become part of the expanding Russian empire. In 1495 Alexander the Jagiellonian expelled the Jews from Grand Duchy of Lithuania but reversed his decision in 1503.

In the shtetls populated almost entirely by Jews, or in the middle-sized town where Jews constituted a significant part of population, Jewish communities traditionally ruled themselves according to halakha, and were limited by the privileges granted them by local rulers. (See also Shtadlan). These Jews were not assimilated into the larger eastern European societies, and identified as an ethnic group with a unique set of religious beliefs and practices, as well as an ethnically unique economic role.

Tsarist Russia (1480s-1917)

Documentary evidence as to the presence of Jews in Muscovite Russia is first found in the chronicles of 1471. The relatively small population of Jews were generally free of major persecution: although there were laws against them during this period, they do not appear to be strictly enforced.

In the 1480s the principality of Muscovy became the religious equivalent of the Caliphate or Holy Roman Empire. Based on the theory of the Third Rome, it was believed that the Tsar ruled the only rightful, practically independent Orthodox state, surrounded by Muslim and Roman Catholic infidels. According to prophecy, there were to be only three Romes, that is, centers of rightful religious faith. The first two, ancient Rome and Constantinople, have already fallen, leaving the only hope on earth with Moscow. The religious zeal of such a theory reasoned for the ultimate measures against the "enemies of the faith", including the Jews.

Muscovite treatment of the Jews became harsher in the reign of Ivan IV, The Terrible (1533-84). For example, in his conquest of Polotsk in February 1563, some 300 local Jews who declined to convert to Christianity were, according to legend, drowned in the Dvina.

Jews were not tolerated in the area of Muscovy, from 1721 the official doctrine of Imperial Russia was openly antisemitic. Even if Jews were tolerated for some modest time, eventually they were expelled, as when the captured part of Ukraine was cleared of Jews in the year 1727. These policies made Muscovite Russia a very hostile environment for Jewish people.

See also Chmielnicki Uprising

Pogroms and the Pale of Settlement

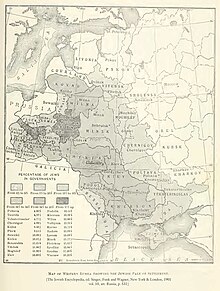

The traditional measures of keeping Russia free of Jews failed when the main territory of Poland was annexed during the partitions. During the second (1793) and the third (1795) partitions, large populations of Jews were taken over by Russia, and the Tsar established a Pale of Settlement that included Poland and Crimea. Jews were supposed to remain in the Pale and required special permission to move to Russia proper, while Russian officials pursued alternating policies designed to encourage assimiliation (such as opening public schools to Jews) and destroy independent Jewish life (such as forbidding Jews to live in certain towns).

Rebellions beginning with the Decembrist Revolt of 1825, followed by the struggle of Russia's intelligentsia, and the rise of nihilism, liberalism, socialism, syndicalism, and finally Communism threatened the old tsarist order. Assuming that many radicals were of Jewish extraction, tsarist officials increasingly resorted to popularizing religious and nationalistic fanaticism.

Alexander II, known as the "Tsar liberator" for the 1861 abolition of serfdom in Russia, was also known for his suppression of national minorities. Under his rule Jews could not commission Christian servants, could not own land, and were restricted to where they could and couldn't travel.[1] Nevertheless, he approved the policy of Polish politician Alexander Wielopolski in the Kingdom of Poland that gave Jews equal rights to other citizens (the prior status of Jews was different; it is questionable whether this distinct status was more or less beneficial). Alexander III was a staunch reactionary who strictly adhered to the old maxim "Autocracy, Orthodoxy, and Nationalism." His escalation of anti-Jewish policies sought to popularize "folk antisemitism," which portrayed the Jews as "Christ-killers" and the oppressors of the Slavic, Christian victims.

A large-scale wave of anti-Jewish pogroms swept southern Russia in 1881, after Jews were wrongly blamed for the assassination of Alexander II. In the 1881 outbreak, there were pogroms in 166 Russian towns, thousands of Jewish homes were destroyed, many families reduced to extremes of poverty; women sexually assaulted, and large numbers of men, women, and children killed or injured. The new czar, Alexander III, blamed the Jews for the riots and on May 15, 1882 introduced the so-called Temporary Regulations ("Временные правила") that stayed in effect for more than thirty years and came to be known as the May Laws.

The Chief Procurator of the Holy Synod and the tsar's mentor, friend, and adviser Konstantin Pobedonostsev was reported as saying that one-third of Russia's Jews was expected to emigrate, one-third to accept baptism, and one-third to starve.[2] The respressive legislation was repeatedly revised. Many historians noted the concurrence of these state-enforced antisemitic policies with waves of pogroms[3] that continued until 1884, with at least tacit government knowledge and in some cases policemen were seen inciting or joining the mob.

The systematic policy of discrimination banned Jews from rural areas and towns of fewer than ten thousand people, even within the Pale, assuring the slow death of many shtetls. In 1887, the quotas placed on the number of Jews allowed into secondary and higher education were tightened down to 10% within the Pale, 5% outside the Pale, except Moscow and St. Petersburg, held at 3%. Strict restrictions prohibited Jews from practicing many professions. In 1886, an Edict of Expulsion was enforced on Jews of Kiev. In 1891, Moscow was cleansed of its Jews (except few deemed useful) and a newly built synagogue was closed by the city's authorities headed by the Tsar's brother. Tsar Alexander III refused to curtail repressive practices and reportedly noted: "But we must never forget that the Jews have crucified our Master and have shed his precious blood."[5]

| Category | Russian Empire |

Russian Jews |

|---|---|---|

| Males | 38.7 | 64.6 |

| Females | 17.0 | 36.6 |

| Average | 27.7 | 50.1 |

The restrictions placed on education, traditionally highly valued in Jewish communities, resulted in ambition to excel over the peers and increased emigration rates.

In 1892, new measures banned Jewish participation in local elections despite their large numbers in many towns of the Pale. "The Town Regulations prohibited Jews from the right to elect or be elected to town Dumas… That way, reverse proportional representation was achieved: the majority of town's taxpayers had to be subjugated to minority governing the town against Jewish interests."[7]

Mass emigration and political activism

| Destination | Number |

|---|---|

| Australia | 5,000 |

| Canada | 70,000 |

| Europe | 240,000 |

| Palestine region | 45,000 |

| South Africa | 45,000 |

| South America | 111,000 |

| USA | 1,749,000 |

The persecutions provided the impetus for mass emigration and political activism among Russian Jews. More than two million of them fled Russia between 1880 and 1920. While vast majority emigrated to the United States, some turned to Zionism. In 1882, members of Bilu and Hovevei Zion made what came to be known the First Aliyah to Palestine, then a part of the Ottoman Empire.

The Tsarist government sporadically encouraged Jewish emigration. In 1890, it approved the establishment of "The Society for the Support of Jewish Farmers and Artisans in Syria and Eretz Israel," (known as the "Odessa Committee" headed by Leon Pinsker) dedicated to practical aspects in establishing agricultural Jewish settlements in the Land of Israel.

A larger wave of pogroms broke out in 1903-1906, leaving an estimated 2,000 Jews dead, and many more wounded. At least some of the pogroms are believed to have been organized or supported by the Tsarist Russian secret police, the Okhranka.

Even more pogroms accompanied the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the ensuing Russian Civil War, when an estimated 70,000 to 250,000 civilian Jews were killed in atrocities throughout the former Russian Empire; the number of Jewish orphans exceeded 300,000. In his book 200 Years Together, Alexander Solzhenitsyn provides the following numbers from Nahum Gergel's 1951 study of the pogroms in the Ukraine during 1917-1918: out of estimated 887 mass pogroms, about 40% were perpetrated by the Ukrainian forces led by Symon Petliura, 25% by the Green Army and various nationalist and anarchist gangs, 17% by the White Army, especially forces of Anton Denikin, and 8.5% by the Red Army.

See also Cantonist, Kishinev pogrom, Beilis trial, Jewish gauchos

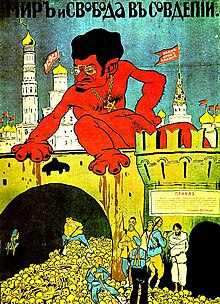

Jews and Bolshevism

Many members of the Bolshevik party were ethnically Jewish, especially in the leadership of the party, and the percentage of Jewish party members among the rival Mensheviks was even higher. The idea of overthrowing the Tsarist regime was attractive to many members of the Jewish intelligentsia because of the oppression of non-Russian nations and non-Orthodox Christians within the Russian Empire. For much the same reason, many non-Russians, notably Latvians or Poles, were disproportionately represented in the party leadership. This fact was abused by the Tsarist secret police, the Okhranka, which used antisemitism and xenophobia as a weapon against the Russian revolutionary movement and promulgated fraudulent Protocols of the Elders of Zion to explain Russian revolutions as a part of a powerful world conspiracy.

Because some of the leading Bolsheviks were ethnic Jews, and Bolshevism supports a policy of promoting international proletarian revolution—most notably in the case of Leon Trotsky—led many enemies of Bolshevism, and continues to lead contemporary antisemites, to draw a picture of Communism as a political slur at Jews and accusing Jews of pursuing Bolshevism to benefit Jewish interests, reflected in the terms "Jewish Bolshevism" or "Judeo-Bolshevism". In Nazi Germany, the regime of Adolf Hitler used this theory as a rallying cry to paint a picture of a supposed "Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy". Even today, many antisemites continue to promote the idea of a link between the Jews and Communism. The original atheistic and internationalistic ideology of the Bolsheviks (See proletarian internationalism, bourgeois nationalism) was incompatible with Jewish traditionalism and the later covert tendencies towards Russian nationalism and (especially after World War II) antisemitism in the Soviet regime placed many secular Jews in conflict with the regime.

Soon after seizing power, the Bolsheviks established the Yevsektsiya, the Jewish section of the Communist party in order to destroy the rival Bund and Zionist parties, suppress Judaism and replace traditional Jewish culture with "proletarian culture".

Most of the Old Bolsheviks, Jewish and Gentile alike, including members of the Yevsektsiya, were repressed by Stalin during the Great Purge of 1930s.

After the October Revolution (1917-1991)

Under Lenin (1917-1924)

In March 1919, Lenin delivered a speech "On Anti-Jewish Pogroms"[9] on a gramophone disc. Lenin sought to explain the phenomenon of antisemitism in Marxist terms. According to Lenin, antisemitism was an "attempt to divert the hatred of the workers and peasants from the exploiters toward the Jews." Linking antisemitism to class struggle, he argued that it was merely a political technique used by the tsar to exploit religious fanaticism, popularize the despotic, unpopular regime, and divert popular anger toward a scapegoat. The Soviet Union also officially maintained this Marxist-Leninist interpretation under Stalin, who expounded Lenin's critique of antisemitism. However, this did not prevent the widely publicized repressions of Jewish intellectuals during 1948–1953 (see After World War II).

Such actions, along with extensive Jewish participation among the Bolsheviks, plagued the Communists during the Russian Civil War against the Whites with a reputation of being "a gang of marauding Jews"; Jews comprised a majority in the Communist Central Committee, outnumbering even ethnic Russians. At the same time, the vast majority of Russia's Jews, much like their ethnic Russian neighbours, were not in any political party.

The attempts of the socialist Jewish Labor Bund to be the sole representative of the Jewish worker in Russia had always conflicted with Lenin's idea of a universal coalition of workers of all nationalities. Like other socialist parties in Russia, the Bund was initially opposed to the Bolsheviks' seizing of power in 1917 and to the dissolving of the Russian Constituent Assembly. Consequently, the Bund suffered repressions in the first months of the Soviet regime [citation needed]. However, the antisemitism of many Whites during the Russian Civil War caused many if not most Bund members to readily join the Bolsheviks, and most of the factions eventually merged with the Communist Party. The movement did split in three; the Bundist identity survived in interwar Poland under Rafael Abramovich, while many Bundists joined the Mensheviks.

In 1921, a large number of Jews opted for Poland, as they were entitled by peace treaty in Riga to choose the country they preferred. Several hundred thousand, despite the prospect of a Communist paradise, joined the already numerous Jewish population of Poland.

Under Stalin (1927-1953)

Before World War II

Russian Jews were long considered a non-native "Semitic" ethnicity in a "Slavic" Russia, and such categorization was solidified when ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union were categorized according to ethnicity (национальность), with Jews being no exception. Under Stalin, a Soviet minority was required to have a culture, a language, and a homeland.

To offset the growing Jewish national and religious aspirations of Zionism and to successfully categorize Soviet Jews under Stalin's nationality, an alternative to the Land of Israel was established with the help of Komzet and OZET in 1928. The Jewish Autonomous Oblast with the center in Birobidzhan in the Russian Far East was to become a "Soviet Zion". Yiddish, rather than "reactionary" Hebrew, would be the national language, and proletarian socialist literature and arts would replace Judaism as the quintessence of culture. Despite a massive domestic and international state propaganda campaign, the Jewish population there never reached 30% (as of 2003 it was only about 1.2%). The experiment ground to a halt in the mid-1930s, during Stalin's first campaign of purges. Jewish leaders were arrested and executed, and Yiddish schools were shut down.

Stalin's letter "Antisemitism: Reply to an Inquiry of the Jewish News Agency in the United States" dated January 12, 1931 indicated his official position:

In answer to your inquiry: National and racial chauvinism is a vestige of the misanthropic customs characteristic of the period of cannibalism. Antisemitism, as an extreme form of racial chauvinism, is the most dangerous vestige of cannibalism.

Antisemitism is of advantage to the exploiters as a lightning conductor that deflects the blows aimed by the working people at capitalism. Antisemitism is dangerous for the working people as being a false path that leads them off the right road and lands them in the jungle. Hence Communists, as consistent internationalists, cannot but be irreconcilable, sworn enemies of antisemitism.

In the U.S.S.R. antisemitism is punishable with the utmost severity of the law as a phenomenon deeply hostile to the Soviet system. Under U.S.S.R. law active antisemites are liable to the death penalty.[10]

In 1936 Pravda, the party's newspaper and main propaganda organ, printed a beneficial explanation of the vile nature of antisemitism. It stated that "national and racial chauvinism is a survival of the barbarous practices of the cannibalistic period... it served the exploiters... to protect capitalism from the attack of the working class; antisemitism, a phenomenon profoundly hostile to the Soviet Union, is repressed in the USSR."

Despite the official Soviet opposition to antisemitism, critics of the ensuing USSR characterize it as an antisemitic regime, pointing out the Non-Aggression Pact with Nazi Germany, the Jewish casualties in the Great Purges, and Soviet hostility toward Jewish religious and cultural institutions (The Purges, and this hostility, however, that was applied with practically equal force against all religious and non-communist cultural institutions). They also cite Soviet anti-Zionism. The Soviet Union did vote in favor of the Partition Plan of Resolution 181, which opened the way for the creation of the state of Israel, in the United Nations 1947 vote, and also recognized Israel immediately after the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel was unilaterally proclaimed, Soviet support for Israel was short-lived, though important. In 1948 the Israelis used vital Soviet arms, obtained via Czechoslovakia to defend the new state. Soviet authorities refused to grant emigration visas for Israel to Soviet Jews, and the USSR took a generally consistent pro-Arab stance during the cold war.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop pact—the 1939 non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany—created further suspicion regarding the Soviet Union's position toward Jews. The pact, arguably allowed Hitler to freely enter Poland, the nation with the world's largest Jewish population, but it was neither an acceptance of Nazism nor instigated by anti-Jewish objectives. With Western backing of the White Russian army in the Russian Civil War a recent memory, and with the failure of Popular Front politics, Stalin appears to have despaired of an alliance with the Western democracies against the Nazis. Believing the USSR to be incapable of resisting the Nazis militarily, he sought a deal. This was certainly a disaster for Eastern Europe's Jews, but that was a side effect rather than a motivation.

The Great Purges are popularly portrayed as antisemitic in the West, thereby ignoring the actual context of Stalin's consolidation of power. A number of the most prominent victims of the Purges—Trotsky, Zinoviev, and Kamenev, to name a few—were ethnic Jews. That is, however, an oversimplification, since Stalin was just as brutal when acting against his real or imagined enemies who were not Jewish—e.g., Bukharin, Tukhachevsky, Kirov, and Ordzhonikidze. The number of prominent Jewish Old Bolsheviks killed in the purge reflects the fact that Jews were the largest group in the Central Committee after the Russians and that Jews had a high participation among the Bolsheviks.

In addition, some Stalinists survived notwithstanding their Jewish heritage. Stalin did not purge Lazar Kaganovich, a loyal supporter who came to Stalin's attention in the 1920s as a successful bureaucrat in Tashkent, who aided Stalin and Molotov against Kirov and who participated in his brutal elimination of rivals in the 1930s. Kaganovich's loyalty endured after Stalin's death, when his opposition to de-Stalinization caused him to be expelled from the party in 1957, along with Molotov.

On the eve of the Holocaust

Beyond longstanding controversies, ranging from the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact to anti-Zionism, the Soviet Union did grant official "equality of all citizens regardless of status, sex, race, religion, and nationality." The years before the Holocaust were an era of rapid change for Soviet Jews, leaving behind the dreadful poverty of the Pale of Settlement. Forty percent of the population in the former Pale left for large cities within the USSR.

Emphasis on education and movement from countryside shtetls to newly industrialized cities allowed many Soviet Jews to enjoy overall advances under Stalin and to become one of the most educated population groups in the world.

Due to Stalinist emphasis on its urban population, interwar migration inadvertently rescued countless Soviet Jews; Nazi Germany penetrated the entire former Jewish Pale—but were kilometers short of Leningrad and Moscow. The great wave of deportations from the areas annexed by Soviet Union according to the Nazi-Soviet pact, often seen by victims as genocide, paradoxically also saved lives of a few hundred thousand Jewish deportees. However horrible their conditions, the fate of Jews in Nazi Germany was much worse. The migration of many Jews deeper East from the part of the Jewish Pale that would become occupied by Germany saved at least forty percent of this area's Jewish population.

The Holocaust

Over two million Soviet Jews died during the Holocaust, second only to the number of Polish Jews who fell victim to Hitler. Even before the mass deportations to the death camps in 1942, German death squads, the Einsatzkommandos, shot hundreds of thousands of Jews throughout 1941. Among some of the larger massacres in 1941 were: 33,771 Jews of Kiev shot in ditches at Babi Yar; 100,000 Jews of Vilna killed in the forests of Ponary, 20,000 Jews killed in Kharkiv at Drobnitzky Yar, 36,000 Jews machine-gunned in Odessa, 25,000 Jews of Riga killed in the woods at Rumbula, and 10,000 Jews slaughtered in Simferopol in the Crimea. Though mass shootings continued through 1942, most notably 16,000 Jews shot at Pinsk, Jews were increasingly shipped to concentration camps in Poland.

Local residents of German-occupied areas, especially Ukrainians, Lithuanians, and Latvians, sometimes played key roles in the genocide of other Latvians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Slavs, Gypsies, homosexuals and Jews alike. Under the Nazi occupation, some members of the Ukrainian and Latvian police carried out deportations in the Warsaw Ghetto, and Lithuanians marched Jews to their death at Ponary. Even as some assisted the Germans, a significant number of individuals in the territories under German control also helped Jews escape death (see Righteous Among the Nations). In Latvia, particularly, the number of Nazi-collaborators was only slightly more than that of Jewish saviours.

Over 200,000 Jews died in battle fighting in the Red Army against the Nazis.

Soviet reaction to the Holocaust

The typical Soviet policy regarding the Holocaust was to present it as atrocities against Soviet citizens, not emphasizing the genocide of the Jews. For example, after the liberation of Kiev from the Nazi occupation, the Extraordinary State Commission (Чрезвычайная Государственная Комиссия) was set out to investigate Nazi crimes. The description of the Babi Yar massacre was officially censored as follows:[11]

| Draft report (December 25, 1943) | Censored version (February 1944) |

|---|---|

|

|

After World War II

In January 1948 Solomon Mikhoels, a popular actor-director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater and the chairman of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, was killed in a suspicious car accident.[12] Mass arrests of prominent Jewish intellectuals and suppression of Jewish culture followed under the banners of campaign against "rootless cosmopolitans" and anti-Zionism. On August 12, 1952, in the event known as the Night of the Murdered Poets, thirteen most prominent Yiddish writers, poets, actors and other intellectuals were executed on the orders of Joseph Stalin, among them Peretz Markish, Leib Kvitko, David Hofstein, Itzik Feffer and David Bergelson.[13] In the 1955 UN Assembly's session a high Soviet official still denied the "rumors" about their disappearance.

The Doctors' plot allegation in 1953 was a deliberately antisemitic policy: Stalin targeted "corrupt Jewish bourgeois nationalists," eschewing the usual code words like "cosmopolitans." Stalin died, however, before this next wave of arrests and executions could be launched in earnest. A number of historians claim that the Doctors' plot was intended as the opening of a campaign that would have resulted in the mass deportation of Soviet Jews had Stalin not died on March 5, 1953. Days after Stalin's death the plot was declared a hoax by the Soviet government.

These cases may have reflected Stalin's paranoia, rather than state ideology — a distinction that made no practical difference as long as Stalin was alive, but which became salient on his death.

- See also Stalinism and antisemitism

After Stalin

In April 1956, the Warsaw Yiddish language Jewish newspaper Folkshtimme published sensational long lists of Soviet Jews who had perished before and after the Holocaust. The world press began demanding answers from Soviet leaders, as well as inquire about current condition of Jewish education system and culture. The same fall, a group of leading Jewish world figures publicly requested the heads of Soviet state to clarify the situation. Since no cohesive answer was received, their concern was only heightened. The fate of Soviet Jews emerged as a major human rights issue in the West.

The Soviet Union and Zionism

Marxist anti-nationalism and anti-clericalism had a mixed effect on Soviet Jews. Jews were the immediate benefactors, but long-term victims, of the Marxist notion that any manifestation of nationalism is "socially retrogressive." On one hand, Jews were liberated from the religious persecution of the Tsarist years of "autocracy, nationalism, and Orthodoxy." On the other, this notion was threatening to Jewish cultural institutions, the Bund, Jewish autonomy, Judaism and Zionism.

Political Zionism was officially stamped out for the entire history of the Soviet Union as a form of bourgeois nationalism. Although Leninism emphasizes "self-determination," this did not make the state more accepting of Zionism. Leninism defines self-determination by territory, not culture, which allowed Soviet minorities to have separate oblasts, autonomous regions, or republics, which were nonetheless symbolic until its later years. Jews, however, did not fit such a theoretical model; Jews in the Diaspora did not even have an agricultural base, as Stalin often asserted when attempting to deny the existence of a Jewish nation, and certainly no territorial unit. Marxian notions even denied a Jewish identity beyond religion and caste; Marx defined Jews as a "chimerical nation."

Lenin, claiming to be deeply committed to egalitarian ideals and universality of all humanity, rejected Zionism as a reactionary movement, "bourgeois nationalism", "socially retrogressive", and a backward force that deprecates class divisions among Jews. Moreover, Zionism entailed contact between Soviet citizens and westerners, which was dangerous in a closed society. Soviet authorities were likewise fearful of any mass-movement independent of monopolistic Communist Party, and not tied to the state or the ideology of Marxism-Leninism.

Without changing its official anti-Zionist stance, from late 1944 until 1948 Stalin had adopted a de facto pro-Zionist foreign policy, apparently believing that the new country would be socialist and would speed the decline of British influence in the Middle East.[14]

The USSR briefly supported the establishment of Israel in a 1947 speech that was not published in the Soviet media. It came during the 1947 UN Partition Plan debate on May 14 1947, when the Soviet ambassador Andrei Gromyko announced:

- "As we know, the aspirations of a considerable part of the Jewish people are linked with the problem of Palestine and of its future administration. This fact scarcely requires proof... During the last war, the Jewish people underwent exceptional sorrow and suffering...

- The United Nations cannot and must not regard this situation with indifference, since this would be incompatible with the high principles proclaimed in its Charter...

- The fact that no Western European State has been able to ensure the defence of the elementary rights of the Jewish people and to safeguard it against the violence of the fascist executioners explains the aspirations of the Jews to establish their own State. It would be unjust not to take this into consideration and to deny the right of the Jewish people to realize this aspiration."[15]

Soviet approval in the United Nations Security Council was critical to the UN partitioning of the British Mandate of Palestine, which led to the founding of the State of Israel. Three days after Israel declared independence, the Soviet Union legally recognized it de jure.

Effects of the Cold War

By the end of 1948 the USSR switched sides in the Arab-Israeli conflict and throughout the course of the Cold War unequivocally supported various Arab regimes against Israel. The official position of the Soviet Union and its satellite states and agencies was that Zionism was a tool used by the Jews and Americans for "racist imperialism".

As Israel was emerging as a close Western ally, the specter of Zionism raised fears of internal dissent and opposition. During the later parts of the Cold War Soviet Jews were persecuted as possible traitors, Western sympathisers, or a security liability. The Communist leadership closed down various Jewish organizations and declared Zionism an ideological enemy. The only exception were a few token synagogues. These synagogues were then placed under police surveillance, both openly and through the use of informers.

As a result of the persecution, both state-sponsored and unofficial antisemitism became deeply ingrained in the society and remained a fact for years: ordinary Soviet Jews often suffered hardships, epitomized by often not being allowed to enlist in universities or hired to work in certain professions. Many were barred from participation in the government, and had to bear being openly humiliated. Soviet media usually avoided using the word "Jew," and many felt compelled to hide their identities by changing their names.

The word "Jew" was also avoided in the media when criticising undertakings by Israel, which the Soviets often accused of racism, chauvinism etc. Instead of Jew, the word Israeli was used almost exclusively, so as to paint its harsh criticism not as antisemitism but anti-Zionism. More controversially, the Soviet media, when depicting political events, sometimes used the term 'fascism' to characterise Israeli nationalism (e.g calling Jabotinsky a 'fascist', and claiming 'new fascist organisations were emerging in Israel in 1970s' etc).

See also rootless cosmopolitan, Doctors' plot, Zionology and Anti-Zionist committee of the Soviet public

The collapse of the Soviet Union and emigration to Israel

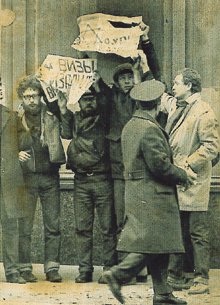

A mass emigration was politically undesirable for the Soviet regime. As increasing number of Soviet Jews applied to emigrate to Israel in the period following the 1967 Six Day War, many were formally refused permission to leave. A typical excuse given by the OVIR (ОВиР), the MVD department responsible for provisioning of exit visas was that the persons who had been given access at some point in their careers to information vital to Soviet national security could not be allowed to leave the country.

After the Dymshits-Kuznetsov hijacking affair in 1970 and the crackdown that followed, strong international condemnations caused the Soviet authorities to increase the emigration quota. In the years 1960-1970, only 4,000 people left the USSR; in the following decade, the number rose to 250,000.[16]

In 1972 the USSR imposed the so-called "diploma tax" on would-be emigrants who received higher education in the USSR. In some cases, the fee was as high as twenty annual salaries. This measure was apparently designed to combat the brain drain caused by the growing emigration of Soviet Jews and other members of the intelligentsia to the West. Following international protests, the Kremlin soon revoked the tax, but continued to sporadically impose various limitations.

At first almost all of those who managed to get exit visas to Israel actually made aliyah, but after the mid-1970s, many of those allowed to leave for Israel actually chose other destinations, most notably the United States. In 1989 a record 71,000 Soviet Jews were granted exodus from the USSR, of whom only 12,117 immigrated to Israel. Since the adoption of the Jackson-Vanik amendment, over one million Soviet Jews have immigrated to Israel.

See also "Russian" aliyah in Israel.

Jews in Russia today

Jewish life

Most Russian Jews are secular and identify themselves as Jews via ethnicity rather than religion, similar to secular Jews in America and other Western countries, although interest about Jewish identity as well as practice of Jewish tradition amongst Russian Jews is growing. Lubavitch has been a catalyst in this sector, setting up synagogues and Jewish kindergartens in Russian cities with Jewish populations. In addition, most Russian Jews have relatives in Israel.

Since the dissolution of the USSR, democratization in the former USSR has brought with it a good deal of tragic irony for the country's minorities, especially the Jewish population. The absence of Soviet-era repression exposed the remaining Jews to a resurgence of antisemitism in the former Soviet Union. However, there has not been a return to mass antisemitic incidents in Russia or anywhere else throughout the former Soviet Union.

Russian Jews are well represented in the fields of medicine, law, science and education. Henri Reznik, the head of Moscow Bar Association, as well as three out of five wealthiest oligarchs in Russia, are Jewish: Roman Abramovich tops the list, Mikhail Fridman is in the third position and Viktor Vekselberg in fifth. Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a former oil tycoon and outspoken critic of president Vladimir Putin who has been jailed on tax evasion charges, is also Jewish. Exiled oligarchs Boris Berezovsky, fugutive Leonid Nevzlin and Vladimir Gusinsky are likewise Jewish.

There are several major Jewish organizations in the territories of the former USSR. The central Jewish organization is the Federation of Jewish Communities of the CIS under the leadership of Chief Rabbi Berel Lazar.

Perhaps stemming from the now obsolete Soviet nationality policy, a linguistic distinction remains to this day in the Russian language where there are two terms for "Jew". The word Еврей ("Yevrey" - Hebrew) typically denotes a Jewish ethnicity, while the world Иудей ("Iudey" - Judean) is reserved for denoting a follower of the Jewish religion, although the latter term has mostly fallen out of use.

Post-Soviet countries and antisemitism

Russia

Despite stipulations against fomenting hatred based on ethnic or religious grounds (Article 282 of Russian Federation Penal Code),[17] anti-Semitic pronouncements, speeches and articles are not uncommon in Russia, and there are a large number of anti-Semitic neo-Nazi groups in the republics of the former Soviet Union, leading Pravda to declare in 2002 that "Anti-Semitism is booming in Russia".[18] Over the past few years there have also been bombs attached to antisemitic signs, apparently aimed at Jews, and other violent incidents, including stabbings, have been recorded.

The government of Vladimir Putin takes an official stand against antisemitism, while some movements parties and groups are explicitly antisemitic. In January 2005, a group of 15 Duma members demanded that Judaism and Jewish organizations be banned from Russia.[19] In June, 500 prominent Russians, including some 20 members of the nationalist Rodina party, demanded that the state prosecutor investigate ancient Jewish texts as "anti-Russian" and ban Judaism. An investigation was in fact launched, but halted after an international outcry.[20][21]

In Russia, both historical and contemporary antisemitic materials are frequently published. For example a set (called Library of a Russian Patriot) consisting of twenty five anti-Semitic titles was recently published, including Mein Kampf translated to Russian (2002), The Myth of Holocaust by Jürgen Graf, a title by Douglas Reed, Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and others.

Antisemitic incidents have ranged from random acts of violence against Jews to the detonation of explosives in Jewish communities, to high-profile cases such as the stabbing of eight Russian Jews in a Moscow synagogue on January 11, 2006 by a man with neo-Nazi ties. See also: Pamyat, Neo-Nazism in Russia.

Ukraine

In Ukraine, renewed nationalist sentiment has fueled antisemitism. Jewish schools and synagogues have been firebombed and assaulted, and Jewish cemeteries vandalized.[citation needed]

Interregional Academy of Personnel Management (MAUP), the largest non-governmental university in the country, hosted white supremacist David Duke in June of 2005, as part of his European and Middle East tour for the promotion of his book, Jewish Supremacism: My Awakening on the Jewish Question. Duke co-hosted a conference named "Zionism As the Biggest Threat to Modern Civilization" during his stay and received an honorary doctorate from the university in September of 2005.

Belarus

In Belarus, anti-Jewish incidents are considerably less frequent than in Russia or Ukraine, due to the fact that President Lukashenko represses all movements that can become a threat to the regime, including local neo-Nazi parties and organizations. Nonetheless, antisemitic incidents, such as vandalization of Jewish Holocaust memorials, cemeteries, and synagogues do occur.

Tajikistan

In Tajikistan, the government began demolition on the Dushanbe synagogue on February 22, 2006 to make way for a new presidential palace. The synagogue was the last remaining synagogue in Tajikistan, and was actively being used for worship until the time of its destruction. The government completed demolition of the Jewish community's kosher butcher, mikveh, and classroom earlier in 2006. In late March, 2006, the government reversed its decision and will allow the community to rebuild the synagogue on its current site.

Assimilation trends

In the Tsarist Russia, assimilation, russification and conversion to the state religion of Orthodox Christianity were official policies. After coming to power and dealing severe blows to all religions, the Bolsheviks undertook efforts to form a new nation of the Soviet people (Советский народ).

The Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union, one of the world's most ethnically diverse nations, with hundreds of distinct nationalities, was also home to a Jewish population of about two million before its disintegration in 1991, making Jews the eleventh largest Soviet nationality (the USSR classified Jews as a nationality). Despite such diversity, Jews were a unique minority in the ideological state. Before and after the Bolshevik Revolution many of the Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Baltic Jews embraced secular education and culture, thereby becoming a minority that had adapted the Russian language and culture.

Jews, in that sense, were not "foreigners" within Soviet Russia but instead a distinct, cohesive group bounded by a common value system, Yiddish language, exclusive cultural institutions, synagogues, and Zionist nationalism, despite the absence of a territorial unit or a single locale. This existence is thus alien to Marxism-Leninism as espoused by the Soviet state, which viewed Jewish cohesiveness as resulting from class struggle, binding proletariat Jews to Jews in oppressor classes. Marxist egalitarianism and universality suggested that it would be ideal to see the assimilation of Jews and the renunciation of Judaism, in a sense contradicting the elements that allowed Jews to be distinct members of society. All Soviet ethnic groups, such as Russians, Ukrainians, Uzbeks, Tatars, were encouraged to look at class over nationality, but did not face assimilation and cultural annihilation because of their individual locales and common languages. While Jews had been bound together in the past by Yiddish, most by the end of the Stalinist era had already adapted the Russian language and culture, and tended to live alongside Slavic gentiles.

Certain Marxists predicted such a sociological trend, but miscalculated the extent to which this trend would erode the cohesiveness of the Jewish community. Karl Marx and some later Marxists assumed that the Jewish identity would cease to exist after the demise of capitalism since man can only be free when he transcended the confines of individuality and locality and recognized a shared humanity, "a universal existence", free of antagonism and divisiveness, which, he believed, only existed due to class struggle. Although the Jewish community went from being one of the most isolated in Europe to one of its most assimilated from the time of the Bolshevik Revolution to the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union, the identity has not faded away.

Law throughout Soviet history, however, listed Jews as one of the Union's "basic nations", with their own language (Yiddish), and their own autonomous region, a failed, inhospitable settlement in the Russian Far East that was nonetheless symbolic. The word "Еврей" (Yevrei, "Jew") was also listed in the "национальность" ("nationality") section (the infamous "Пятая графа" (pyataya grafa, "the fifth record") of the obligatory internal passport document, which stated the ethnic or national background of all Soviet citizens. Such treatment of Jews as a nationality is somewhat alien to Jewish law, but reminiscent of Zionism. In May 1976, the Soviet journal Party Life prominently displayed Jews as a distinct "nationality."

While Soviet socialism clearly did not destroy the Jewish identity, it nevertheless weakened a degree of cultural cohesiveness. Hebrew and Yiddish languages, Jewish theaters, Jewish schools, religion and Zionism bounded the Soviet Jewish population together despite the absence of a common locale; but these were the very elements restricted by a Soviet Union promoting secularism among all its citizens. The closings of synagogues and other important Jewish cultural institutions, such as theaters, schools and periodicals, were conducted under this ideological context of egalitarianism. While threatening to Judaism and the Jewish culture, the regime enforced the same policies on other religions, leading to the development of a modern, secular state. However, after the end of the Second World War, the restrictions against Christians and Muslims were gradually reduced, while the persecution of Judaism remained in force. The rise of Jewish secularism thus paralleled social trends among Soviet non-Jews, but had threatening overtones to Jewish existence. Soviet secularism, the discouragement of Yiddish, and the restriction of other elements that forged an exclusive, Jewish identity, caused assimilation to be a foreboding threat to Jewish existence. Soviet rule can be characterized by a rise in intermarriages and abandonment of Jewish identities by those who were eager to prove their loyalty to the Communist Party's atheism and proletarian internationalism, and committed to stamp out any sign of "Jewish cultural particularism", such as Leon Trotsky, Maxim Litvinov or Lazar Kaganovich.

Assimilated Jews significantly contributed to Russian and Soviet multi-ethnic culture, science and technology. It is hard to imagine Russian art without Isaac Levitan and Léon Bakst; Russian literature—Isaac Babel, Osip Mandelstam and Boris Pasternak; Russian ballet—Ida Rubinstein and Maya Plisetskaya; Soviet cinematography— Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov, Mikhail Romm, Grigori Chukhrai; Russian and Soviet music—Anton Rubinstein and Isaak Dunayevsky; comedy—Faina Ranevskaya, Arkady Raikin and Mikhail Zhvanetsky; science—Lev Landau, Abram Ioffe and Yakov Zel'dovich; defense industry—Boris Vannikov, Mikhail Gurevich (of MiG) and Semyon Lavochkin.

Demographic data

The official census data on Jewish population of Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union.[22] The number of Jews has fallen from about 2.15 million in 1970 (the third largest population in the world, after the USA and Israel, and the fourth largest ethnic group in the Soviet Union) to 1.45 million in 1989 (less than 600,000 in Russia itself) and to some 250,000 in Russia, according to the 2002 census. The decline is mostly due to emigration to Israel, but close to one million Jews living on former Soviet territory other than Russia do not appear in the most recent census.

| Year | Jewish population, millions | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 1914 | More than 5.25 | Russian Empire |

| 1939 | 3 | A result of border change, emigration, assimilation and repressions |

| Early 1941 | 5.4 | A result of the annexation of Western Ukraine and Belarus, Baltic republics, and inflow of Jewish refugees from Poland |

| 1959 | 2.26 | See the Shoah (Holocaust) |

| 1970 | 2.15 | |

| 1979 | 1.81 | |

| 1989 | 1.45 | |

| End of 1993 | Less than 0.4 | A result of mass emigration and assimilation. Militaryov calls this number "especially funny". By his estimate, the real number should be 2-3 million. See also Jewish Virtual Library |

The Jewish population in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast of the Russian Far East as of 2002 is 2,327 (1.22%).

The Bukharan Jews, self-designating as Yahudi, Isroel or Banei Isroel, live mainly in Uzbek cities. The number of Central Asian Jews was around 20,800 in 1959. Before mass emigration, they spoke a dialect of the Tajik language. [1]

The Georgian Jews numbered about 35,700 in 1964, most of them living in Georgia. [2]

The Caucasian Mountain Jews, also known as Tats or Dagchufuts, live mostly in Dagestan, with a scattered population in Azerbaijan. In 1959, they numbered around 15,000 in Dagestan and 10,000 in Azerbaijan. Their Tat language is a dialect of Persian. [3]

The Crimean Jews, self-designating as Krymchaks, traditionally lived in the Crimea, numbering around 5,700 in 1897. Due to a famine, a number emigrated to Turkey and the USA in the 1920. The remaining population was virtually annihilated in the Holocaust during the Nazi occupation of the Crimea, but Krymchaks re-settled the Crimea after the war, and in 1959, between 1,000 and 1,800 had returned. [4]

See also

- Jewish history and Jewish diaspora

- Regional history

- Other

Footnotes

- ^ Duffy, James P., Vincent L. Ricci, Czars: Russia's Rulers for Over One Thousand Years, p. 324

- ^ History of the national question in Russia at Russian Committee in defense of the human rights (in Russian), also in AXT: Russia and in Studies in Comparative Genocide by Levon Chorbajian (p.237)

- ^ A History of Russia by Nicholas Riasanovsky, p.395

- ^ 1904 Chromolithograph (Library of Congress

- ^ But Were They Good for the Jews? by Elliot Rosenberg, p.183

- ^ Age 10 and up. Comparative literacy rates in Russian Empire in 1897 at Beyond the Pale

- ^ The newest history of the Jewish people, 1789-1914 by Simon Dubnow, vol.3, Russian ed., p.152

- ^ Jewish Emigration from Russia: 1880 - 1928 (Beyond the Pale)

- ^ Lenin's March 1919 speech On Anti-Jewish Pogroms («О погромной травле евреев»: text, )

- ^ Joseph Stalin. Works, Vol. 13, July 1930-January 1934, Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1955, p. 30

- ^ Draft report by the Commission for Crimes Committed by the Nazis in Kiev from February 1944. The page 14 shows changes made by G. F. Aleksandrov, head of the Propaganda and Agitation Department, Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- ^ According to historian Gennady Kostyrchenko, recently opened Soviet archives contain evidence that the assassination was organized by L.M. Tsanava and S. Ogoltsov of the MVD

- ^ Stalin's Secret Pogrom: The Postwar Inquisition of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (introduction) by Joshua Rubenstein

- ^ A History of the Jews by Paul Johnson, London, 1987, p.527

- ^ UN Debate Regarding the Special Committee on Palestine: Gromyko Statement. 14 May 1947 77th Plenary Meeting Document A/2/PV.77

- ^ History of Dissident Movement in the USSR by Ludmila Alekseyeva. Vilnius, 1992 (in Russian)

- ^ International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. Russian Federation. 28/07/97. CERD/C/299/Add.15

- ^ Explosion of anti-Semitism in Russia Pravda, 2002-07-30, retrieved 17 Oct 2005.

- ^ Deputies Urge Ban on Jewish Organizations, Then Retract - Bigotry Monitor. Volume 5, Number 4. January 28, 2005. Published by UCSJ. Editor: Charles Fenyvesi

- ^ Prosecutor Drops Charges of Antisemitism Against Duma Deputies - Bigotry Monitor. Volume 5, Number 24. June 17, 2005. Published by UCSJ. Editor: Charles Fenyvesi

- ^ Russia to Drop Probe of Jewish Law Code Accused of Stoking Ethnic Hatred - Bigotry Monitor. Volume 5, Number 26. July 1, 2005. Published by UCSJ. Editor: Charles Fenyvesi

- ^ Implemented Myth (Russian ed.: Воплощённый миф) 2003, p. 46) by Dr. Alexander Militaryov, director of Moscow Jewish University ISBN 5-8062-0068-X

References

- Yuri Slezkine, The Jewish Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2004. ISBN 0-691-11995-3

- S. Ansky, Enemy At His Pleasure: A Journey Through The Jewish Pale Of Settlement During World War I, 2004. ISBN 0-8050-5945-8

- Joshua Rubenstein, Stalin's Secret Pogrom: The Postwar Inquisition of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee ISBN 0-300-08486-2

- Jeffrey Veidlinger, The Moscow State Yiddish Theater ISBN 0-253-33784-4

- Joseph Schechtmann, Star in Eclipse: Russian Jewry Revisited

- Brent Jonathan and Vladimir P. Naumov, Stalin's Last Crime: The Plot against the Jewish Doctor's, 1948-1953, Harper Collins Publishers, New York, 2003.

- Ch. Hoffman, Red Shtetl. The Survival of a Jewish Town under Soviet Communism, AJJDC, New York, 2002.

- Henry Abramson, A Prayer for the Government: Ukrainian and Jews in Revolutionary Times, 1917-1920, Harvard University Press, 1999, pp. 109-141. DS135 R93 U3722.

- Mordechai Altshuler, Soviet Jewry on the Eve of the Holocaust, A Social and Demographic Profile, Jerusalem, 1998.

- Dov Levin, Baltic Jews under the Soviets: 1940-1946, Jerusalem, 1994.

- Benjamin Pinkus, The Jews of the Soviet Union: The History of a National Minority, Cambridge, 1988.

- M. Altshuler, Soviet Jewry since the Second World War. Population and Social Structure, Greenwood Press, New York etc., 1987.

- Michael Beizer, Our Legacy: The CIS Synagogues, Past and Present, Jerusalem-Moscow, 2002.

- Hilel Butman, From Leningrad to Jerusalem, The Gulag Way, Berkeley, 1990.

- Anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union, its Roots and Consequences, proceedings of a seminar held in Jerusalem, April 7-8, 1978, The Hebrew University, Center for Research and Documentation of East European Jewry, 1979.

- Alfred Avraham Greenbaum, Jewish Scholarship and Scholarly Institutions in Soviet Russia, 1918-1953, Jerusalem, 1978.

- Zvi Halevy, Jewish University Students and Professionals in Tsarist and Soviet Russia, Tel Aviv, 1976.

- Zvi Gitelman, Jewish Nationality and Soviet Politics: The Jewish Sections of the CPSU, Princeton, 1972.

- The Jews in Soviet Russia since 1917, Oxford, 1972.

- Eduard Kuznetsov, Prison Diaries, New York, 1975.

- L. Schroeter, The Last Exodus, New York, 1974.

- J.B. Schechtman, The U.S.S.R., Zionism, and Israel, The Jews in Soviet Russia since 1917, Oxford, 1972, pp. 99-124.

- E. Schulman, A History of Jewish Education in the Soviet Union, N. Y., 1971.

- Protest against the suppression of Hebrew in the Soviet Union 1930-1931 signed by Albert Einstein, among others

- Natan Sharansky, Fear No Evil. The Classic Memoir of One Man's Triumph over a Police State. ISBN 1-891620-02-9.

- Wistrich, Robert S. , Antisemitism: The Longest Hatred, Pantheon Books, 1992

- —, "Anti-Semitism", article in The Encyclopedia Judaica, Keter Publishing

- Simon Dubnow, History of the Jews in Russia and Poland from the earliest times until the present day in three volumes, updated by author in 1938.

- Alexander Pereswetoff-Morath, A Grin without a Cat, vol. 1: Adversus Iudaeos Texts in the Literature of Medieval Russia (988-1504), Lund University, 2002. ISBN 91-970201-0-9.

- Alexander Pereswetoff-Morath, A Grin without a Cat, vol. 2: Jews and Christians in Medieval Russia: Assessing the Sources, Lund University, 2002. ISBN 91-970201-1-7.

- Löwe, Heinz-Dietrich, "The Tsar and the Jews. Reform, Reaction and Anti-Semitism in Imperial Russia", Chur 1993

- Duffy, James P., and Vincent L. Ricci, Czars: Russia's Rulers for Over One Thousand Years, ISBN 0-8160-2873-7. New York: Facts on File, 1995.

In Russian

- Кандель, Феликс. Книга времен и событий, Т. 3. История евреев Советского Союза (1917-1939). Иерусалим-Москва, Мосты культуры, 2002.

- Kandel, Felix. History of the Soviet Jews (1917-1939)

- Дубнов, Семён Маркович. Новейшая история еврейского народа (1789-1914) в 3х томах. (С эпилогом 1938 г.). Иерусалим-Москва, Мосты культуры, 2002. ISBN 5-93273-104-4

- Dubnow, Simon. The Newest History of the Jewish People (1789-1914)

- Костырченко, Геннадий. Тайная политика Сталина. Власть и антисемитизм. Москва, 2001.

- Kostyrchenko, Gennady. Stalin's Secret Politics. Power and Antisemitism

- Книга о русском еврействе, 1917-1967, Под редакцией Фрумкина Я.Г., Аронсона Г.Я. и Гольденвейзера А.А. Нью-Йорк, 1968 (или Иерусалим-Москва, Мосты культуры, 2002).

- Book on Russian Jewry, 1917-1967, ed. by Frumkin, Ya. et.al

- Альтман, И. Жертвы ненависти. Холокост в СССР 1941-1945 гг. Москва, Фонд "Ковчег", Коллекция "Совершенно секретно", 2002.

- Altman, I. Victims of Hatred. The Holocaust in the USSR 1941-1945

- Бейзер, М. Евреи Ленинграда, 1917-1939: Советизация и национальная жизнь. Иерусалим-Москва, Мосты культуры, 1999.

- Beizer, M. Jews of Leningrad

- Еврейский антифашистский комитет 1941-1948. Редакторы Редлих Ш. и Костырченко Г. Москва, "Международные отношения", 1996.

- Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. 1941-1948, ed. by Redlikh, Sh., Kostyrchenko, G. et.al

- Морозов, Б. Еврейская эмиграция в свете новых документов. Тель-Авив, Центр Каммингса, Тель-Авивский университет, 1998.

- Morozov, B. Jewish Emigration in Light of New Documents

- Евреи в Советской России (1917-1967). Иерусалим, Библиотека-Алия, 1975.

- Jews in the Soviet Russia (1917-1967)

- Чёрная Книга, Редакторы Эренбург, Илья и Гроссман, Василий. Иерусалим: Тарбут, 1970. Киев: Оберiг, 1991

- The Black Book Compiled and Edited by Vasily Grossman, Ilya Ehrenburg

- Амитин-Шапиро З.Л. Очерк правового быта Среднеазиатских евреев. - Ташкент - Самарканд: Узбекское государственное изд-во, 1931.

- Amitin-Shapiro, Z. An Essay on the Laws of the Bukharan Jews

External links

- Beyond the Pale: The history of Jews in Russia

- Charity for Russian Jews

- Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs: Post-Holocaust and Anti-Semitism

- Jews in Russia, 1906 article at the Jewish Encyclopedia

- History of Berdychiv

- Jews in the Soviet Army

- Jews of Russia (USSR), Russia, USSR in The Jewish Encyclopedia in Russian on the Web

- Tel Aviv University's Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary Anti-Semitism and Racism

- The Harsh Plight of the Soviet Jews Time

- FSU Monitor, News, opinion, and advocacy on Jews and human rights in the former Soviet Union. A project of UCSJ (Union of Councils for Jews in the Former Soviet Union)

- Chabad-Lubavitch Centers in Russia