Languages of Europe

Most of the many languages of Europe belong to the Indo-European language family. Another major family is the Finno-Ugric. The Turkic family also has several European members. The North and South Caucasian families are important in the southeastern extremity of geographical Europe. Basque is a language isolate and Maltese is the only national language in Europe that is Semitic.

This list does not include languages spoken by relatively recently-arrived migrant communities.

Indo-European languages

Most European languages are Indo-European languages. This large language family is descended from Proto-Indo-European, spoken thousands of years ago.

Slavic languages

East Slavic languages

West Slavic languages

South Slavic languages

- Montenegrin (no international standardization)

- Old Church Slavonic (a liturgical language)

- Romano-Serbian (a mixed language)

Germanic languages

West Germanic

Anglo-Frisian

- Anglo-Frisian

- Frisian

- Anglic (descending from Anglo-Saxon)

- Modern English

- Modern Scots in Scotland and Ulster

- Yola (extinct 19th century)

- Shelta (mixed with Irish)

Low Franconian

North Germanic

(descending from Old Norse)

- Continental Scandinavian

- Insular Scandinavian

East Germanic

- Gothic (extinct)

- Burgundian (extinct)

- Crimean Gothic (extinct in the 1800s)

- Lombardic (extinct)

- Vandalic (extinct)

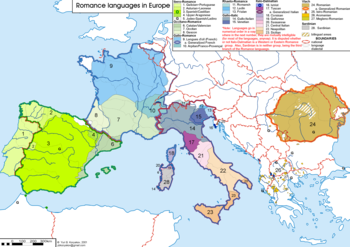

Romance languages

The Romance languages descended from the Vulgar Latin spoken across most of the lands of the Roman Empire.

- French is official in France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Monaco, Switzerland and the Channel Islands. It is also official in Canada, many African countries and overseas departments and territories of France.

- Italian is official in Italy, San Marino, Switzerland, Vatican and several regions of Croatia and Slovenia.

- Spanish (also termed Castilian) is official in Spain. It is also official in most Latin American countries.

- Romanian is official in Romania, Moldova (as Moldovan), Mount Athos (Greece) and Vojvodina (Serbia).

- Latin is usually classified as an Italic language of which the Romance languages are a subgroup. It is extinct as a spoken language, but it is widely used as a liturgical language by the Roman Catholic Church and studied in many educational institutions. It is also the official language of Vatican City. Latin was the main language of literature, sciences and arts for many centuries and greatly influenced all European languages.

- Portuguese is official in Portugal. It is also official in Brazil and several former Portuguese colonies in Africa and Eastern Asia (see Geographic distribution of Portuguese and Community of Portuguese Language Countries).

- Catalan is official in Andorra, and co-official in in the Spanish regions of Catalonia, Valencian Community (as Valencian), Balearic Islands. It is also natively spoken in France in the Languedoc-Rousillon region (Llengadoc-Rosselló) and in Sardinia, Italy (as Alguerese).

- Galician, akin to Portuguese, is co-official in Galicia, Spain. It is also spoken by Galician diaspora (more than local population).

- Occitan is spoken principally in France, but is only officially recognized in Spain as one of the three official languages of Catalonia (termed there Aranese). Its use was severely reduced due to the once de jure and currently de facto promotion of French; since 2008 it is among the regional languages recognised in the French constitution.

- Franco-Provençal, sometimes called "Arpitan," protected by statutes in the Aosta Valley Autonomous Region of Italy, also spoken alpine valleys of the province of Turin, two communities in province of Foggia, Romandy region of western Switzerland, and in east central France (i.e., between standard French and Occitan domains). It is in serious danger of extinction.

- Norman has been debatedly referred to as a language in its own right or a dialect of standard French with its own regional character. Its use is recognized in the Channel Islands, remnants of the historical Duchy of Normandy, and since 2008 it is among the regional languages recognised in the French constitution.

- Corsican is spoken exclusively on the French island of Corsica and is much more closely related to the Italian or northern Italian regional languages. Unlike other French minority languages, it has a healthier outlook, but still suffers from a lack of promotion.

- Romansh is an official language of Switzerland.

- Mirandese is officially recognized by the Portuguese Parliament.

- Leonese is recognized in Castile and León (Spain).

Some of the above languages are official in the European Union and the Latin Union and the more prominent ones are studied in many educational institutions worldwide. This is due to the fact that just three of the Romance languages, French, Spanish, and Portuguese are spoken by close to a billion speakers.

Many other Romance languages and their local varieties are spoken throughout Europe. Some of them are recognized as regional languages.

Romance languages are divided into many subgroups and dialects. For an exhaustive list, see List of Romance languages.

Greek

- Greek: official language of Greece and Cyprus; and Greek-speaking enclaves in Albania, Bulgaria, Italy, the Republic of Macedonia, Romania, Georgia, Ukraine, Lebanon, Egypt, Israel, Jordan and Turkey, and in Greek communities around the world. Dialects of modern Greek that originate from the Ionian Koine are Cappadocian, Pontic, Cretan, Cypriot, Katharevousa, and Yevanic.

- Tsakonian language: Doric dialect of the Greek language spoken in the lower Arcadia region of the Peloponnese around the village of Leonidio.

- Griko: Debatably a Doric dialect of the Greek Language spoken in the lower Calabria region and in the Salento region of Southern Italy.

To say hello in Greek say " Yasoo"

Armenian

The Armenian language is widely spoken as the majority language in Armenia. There are Armenian speakers in globally scattered communities of the Armenian diaspora in Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas (in North and South America). It was an official language when there alphabet was created by Mesrop Mashtotes. It is a diverse laguagein cluding words from all surounding nations. It include Russian, Arabic, Georgian, Frech, German, and turkish.

To say hello in Armenian say "Barev".

Albanian

Albanian language is made up of two major dialects, Gheg and Tosk spoken in Albania, the Republic of Macedonia, Kosovo and Albanian speakers living in parts of Montenegro, Serbia, Turkey, also southern parts of Italy, northern part of Greece and many other European countries.

Baltic languages

- Lithuanian

- Latvian

- Curonian

- Latgalian

- Samogitian

- Galindian (extinct)

- Old Prussian (extinct)

- Selonian (extinct)

- Semigallian (extinct)

- Sudovian (extinct)

Indo-Iranian languages

Indo-Aryan Languages

Iranian languages

Celtic languages

Brythonic

Goidelic (Gaelic)

Semitic languages

Maltese

Maltese is a Semitic language with Romance and Germanic influences, spoken in Malta.[1][2][3][4] It is based on Sicilian Arabic, with influences from Italian (particularly Sicilian), French, and more recently, English. It is unique in being the only Semitic language written in the Latin alphabet in its standard form. It is the smallest official language of the EU in terms of speakers, and the only official Semitic language within the EU.

Cypriot Maronite Arabic

Cypriot Maronite Arabic (also known as Cypriot Arabic) is a variety of Arabic spoken by Maronites in Cyprus. Most speakers live in Nicosia, but others are in the communities of Kormakiti and Lemesos. Brought to the island by Maronites fleeing Lebanon over 700 years ago, this variety of Arabic has been influenced by Greek in both phonology and vocabulary, while retaining certain unusually archaic features in other respects.

Finno-Ugric languages

The Finno-Ugric languages are a subfamily of the Uralic language family.

- Ugric (Ugrian)

- Finno-Permic

- Permic

- Finno-Volgaic

- Mari

- Mordvinic

- Extinct Finno-Volgaic languages of uncertain position

- Finno-Lappic

- Sami

- Western Sami

- Eastern Sami

- Kemi Sami (extinct)

- Inari Sami

- Akkala Sami (extinct)

- Kildin Sami

- Skolt Sami

- Ter Sami

- Baltic-Finnic

- Estonian

- South Estonian

- Võro (including Seto)

- Finnish (including Meänkieli or Tornedalian Finnish, Kven Finnish, and Ingrian Finnish)

- Ingrian

- Karelian

- Karelian proper

- Lude

- Olonets Karelian

- Livonian

- Veps

- Votic

- Estonian

- Sami

Altaic languages

Distribution of the proposed Altaic languages across Eurasia

The proposed but controversial Altaic language family is claimed to consist of three branches (Turkic, Mongolian, and Manchu-Tungus) that show similarities in vocabulary, morphological and syntactic structure, and certain phonological features. On the basis of systematic sound correspondences, they are generally considered to be genetically related. In Europe the Turkic branch prevail, though the Mongolic branch is represented also.

Turkic languages

Oghuz

To say Hellow in Oghuz say "Nassulsun".

Kypchak

- Western

Oghur

Mongolic languages

South Caucasian languages

Northeast Caucasian languages

Northwest Caucasian languages

Basque

The Basque language is a language isolate spoken at the western Pyrenees and directly related to ancient Aquitanian. The language may have been spoken in a wider area since Paleolithic times.

The language is also spoken by immigrants in Australia, Costa Rica, Mexico, the Philippines, and the USA.[5]

General issues

Linguas Francas—past and present

Europe’s history is characterized by six [citation needed]linguas francas:

- Classical Greek then Koine Greek in the Mediterranean Basin and later the Roman Empire

- Koine Greek and Modern Greek, in the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire and other parts of the Balkans[6]

- (Medieval and Neo-) Latin (from the Roman Empire until 1867, with Hungary as the last country to give up Latin as an official language apart from the Vatican City), with a gradual decline as lingua franca since the late Middle Ages, when the vernacular languages gained more and more importance (first language academy in Italy in 1582/83), in the 17th c. even at universities).

- Spanish (from the times of the Catholic Kings and Columbus, ca. 1492 (i.e. after the Reconquista, till the times of Louis XIV, ca. 1648)[citation needed]

- French (from the times of Cardinal Richelieu and Louis XIV, ca. 1648 (i.e. after the Thirty Years' War, which had hardly affected France, thus free to prosper), till the end of World War I, ca. 1919)

- English (Since 1919, and especially since 1945, due to U.S. influence and subsequently due to lingua franca status internationally)

Linguas francas that were characteristic of parts of Europe at some periods:

- Latin during and after the collapse of the Roman Empire until supplanted by French and then English.

- Old French in all the western European countries (England, Italy), and in the Crusader states

- Provençal (Occitan) (12th—14th century, due to Troubadour poetry)

- Czech, mainly during the reign of Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV but also during other periods of Bohemian control over the HRE.

- Middle Low German (14th – 16th century, during the heyday of the Hanseatic League)

- Polish (16th-18th century, because of the political, cultural, scientific and military influence of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth)

- Sabir, a Romance-based lingua franca used around the Mediterranean in the Middle Ages and early Modern Age.

- German in Northern, Central, and Eastern Europe[7]

- Russian in Eastern Europe from the Second World War to the breakup of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact

First dictionaries and grammars

The first type of dictionaries are glossaries, i.e. more or less structured lists of lexical pairs (in alphabetical order or according to conceptual fields). The Latin-German (Latin-Bavarian) Abrogans is among the first. A new wave of lexicography can be seen from the late 15th century onwards (after the introduction of the printing press, with the growing interest for standardizing languages).

Language and identity, standardization processes

In the Middle Ages the two most important definitory elements of Europe were Christianitas and Latinitas. Thus language—at least the supranational language—played an elementary role. This changed with the spread of the national languages in official contexts and the rise of a national feeling. Among other things, this led to projects of standardizing national language and gave birth to a number of language academies (e.g. 1582 Accademia della Crusca in Florence, 1617 Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft, 1635 Académie française, 1713 Real Academia de la Lengua in Madrid). “Language” was then (and still ist today) more connected with “nation” than with “civilization” (particularly in France). “Language” was also used to create a feeling of “religious/ethnic identity” (e.g. different Bible translations by Catholics and Protestants of the same language).

Among the first standardization discussions and processes are the ones for Italian (“questione della lingua”: Modern Tuscan/Florentine vs. Old Tuscan/Florentine vs. Venetian > Modern Florentine + archaic Tuscan + Upper Italian), French (standard is based on Parisian), English (standard is based on the London dialect) and (High) German (based on: chancellery of Meißen/Saxony + Middle German + chancellery of Prague/Bohemia [“Common German”]). But also a number of other nations have begun to look for and develop a standard variety in the 16th century.

Treatment of linguistic minorities

The linguistic diversity of Europe is protected by e.g. the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

The historical attitue towards diversity can be illustrated by two French laws, or decrees: the Ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts (1539), which says that every document in France should be written in French (i.e. not in Latin nor Occitan) and the Loi Toubon (1994), which aims to eliminate Anglicisms from official documents.

Despite previous attempts to achieve national linguistic homogenization, like in France during the Revolution, Franco's Spain and Metaxas's Greece, the “one nation = one language” concept is hard on its way to become obsolete. As for now, France, Andorra and Turkey are the only European countries that have not yet signed the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, while Greece, Iceland and Luxembourg signed it, but haven't ratified it. This framework entered into force in 1998 and is now nearly compulsory to implement in order to be accepted in the European Union, which implies France would not qualify for EU entry were it to apply for membership now.

Early promotion of linguistic diversity is attested at the translation school in Toledo, founded in the 12th century (in medieval Toledo the Christian, the Jewish and the Arab civilizations lived together remarkably peacefully).

A minority language can be defined as a language used by a group that defines itself as an ethnic minority group, whereby the language of this group is typologically different and not a dialect of the standard language. In Europe some languages are in quite a strong position, in the sense that they are given special status, (e.g. Basque, Irish, Welsh, Catalan, Rhaeto-Romance/Romansh), whereas others are in a rather weak position (e.g. Frisian, Scottish Gaelic, Turkish)[dubious – discuss]—especially allochthonous minority languages are not given official status in the EU (in part because they are not part of the cultural heritage of a civilization). Some minor languages don’t even have a standard yet, i.e. they have not even reached the level of an ausbausprache yet, which could be changed, e.g., if these languages were given official status. (cf. also next section).

Official status and proficiency

A more tolerant linguistic attitude is the reason why the EU’s general rule is that every official national language is also an official EU language. However Luxembourgish for instance is not an official EU language, because there are also other (stronger) official languages with “EU status” in the respective nation.[dubious – discuss] Several concepts for an EU language policy are being debated:

- one official language (e.g. English, French, German)

- several official languages (e.g. English, French, German, Italian, Spanish + another topic-dependent language)

- all national languages as official languages, but with a number of relais languages for translations (e.g. English, French, German as relais languages).

New immigrants in European countries are expected to learn the host nation's language, but are still speaking and reading their native languages (i.e. Arabic, Hindustani/Urdu, Mandarin Chinese, Swahili and Tahitian) in Europe's increasingly multiethnic/multicultural profile. But, those languages aren't native or indigenous to Europe, therefore aren't considered important in the issue of allowing them printed in European countries' official documents.

The proficiency of languages is increasingly related to second or third language learning and has been subject to recent shifts caused by changing popularity and government policy.

-

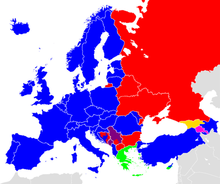

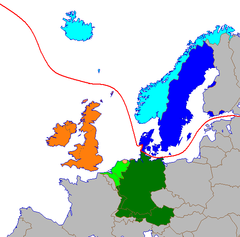

Knowledge of English

-

Knowledge of German (different scale from English)

-

Knowledge of French (same scale as German)

-

Knowledge of Spanish (same scale as German)

-

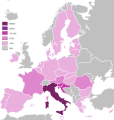

Knowledge of Italian

-

Knowledge of Russian

Notes

- ^ [1]

- ^ Journal of Semitic Studies 1958 3(1):58-79; doi:10.1093/jss/3.1.58

- ^ The Structure of Maltese by Joseph Aquilina Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 80, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1960), pp. 267-268

- ^ [2]

- ^ UCLA — Language Materials Project

- ^ cf. Jireček Line; "...Greek, the lingua franca of commerce and religion, provided a cultural unity to the Balkans... Greek penetrated Moldavian and Wallachian territories as early as the fourteenth century.... The heavy influence of Greek culture upon the intellectual and academic life of Bucharest and Jassy was longer termed than historians once believed." James Steve Counelis, review of Ariadna Camariano-Cioran, Les Academies Princieres de Bucarest et de Jassy et leur Professeurs in Church History 45:1:115-116 (March 1976) at JSTOR

- ^ Jeroen Darquennes and Peter Nelde, "German as a Lingua Franca", Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 26:61-77 (2006)

See also

- List of living languages in Europe

- List of endangered languages in Europe

- List of extinct languages of Europe

- Eurolinguistics

- Languages of the European Union

- Demography of Europe

- European ethnic groups

- Multilingual countries and regions of Europe