Farah Province

Template:Geobox 32°30′N 63°30′E / 32.5°N 63.5°E

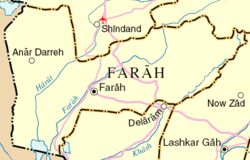

Farah (Persian: فراه) is one of the thirty-four provinces of Afghanistan. It is in the southwest of the country. Its capital is Farah. Farah is a spacious and sparsely populated province that lies on the Iranian border. The population is predominantly Pashtun.

Geographically the province is approximately 18,000 square miles, making it (comparatively) more than twice the size of Maryland, or half the size of South Korea. The province is bounded on the north by Herat, on the northeast by Ghor, the southeast by Helmand, the south by Nimroz, and on the west by Iran. It is the fourth largest province in Afghanistan.

The province is home to a great many ruined castles including the "Castle of the Infidel" just south of Farah City.

Culture

Farah is associated with large families (families typically have a minimum of four children). The culture of Farah is patriarchal, where the tribal leaders, almost always men, are highly respected. Family pride is strongly valued and family members are taught to respect it and ensure that it is maintained at all times.

The tomb of Syed Muhammad Jaunpuri (who claimed to be the Mahdi) is in Farah and is visited every year by many people from all around the world, especially Pakistan and India.

Farah belonges culturally and historically to Sistan (Sistan and Balutschestan Province in Iran) and the Greater Khorasan. Farah shares a unique culture with the people of Iran, especially with the people of the eastern provinces of Iran (language, dialect, expressions, mythology, etc.).

Particularly the ethnic-persians (called Fars, Farsiwan or Tajik in persian, which is the same expression but Fars is more used by the ethnic-persians of Farah province, Tajik more in northern, mid, southern and eastern Afghanistan) of Farah have a huge and remarkable interaction to Iran and Iranians: This is not since the migration of people of Farah in 1979 to Iran and the eruption of soviet occupation of Farah but more prior to this time.

A lot of ethnic-persians in Farah have family members and relatives in Iran before the existence what we call nowadays the national state of Iran and Afghanistan. Many of the ethnic-persians know the Iranian city of Sabol, Birjand, Mashad or Bojnourd as well as Farah because these are persian cities in which they share the same language, dialect, Shia Islam, mythology, family members and much more.

The same situation is existent for pashtun people who have relatives to the border area or in cities of Pakistan and again it should be mentioned that the duration of such family relations between persians from Farah to Iran or pashutuns from Paktia to Pakistan has been as long as the exitence of the current political borders between Iran, Afghanistan or Pakistan.

It is quiet sure that ethnic-persians in Farah watch iranian-persian movies, listen to iranian-persian music or read iranian-persian books and are familiar with their iranian-persian ethnic brothers and sisters in Iran while a pashtun is more and much interested in developments of pashtun cultures. That causes also travelling to Iran for ethnic-persians from Farah and travelling for pashtuns to Pakistan to their pashtun relatives.

Ethnic-persians would, if they does not intent only to visit their relatives in Iran, and are interested in culture and education, as mentiond above, would visit the tomb of Hafez and Saadi in Shiraz or the tomb of Ferdowsi in Mashad, if religious and associated to the Shia Islam one would or could pilgrim to the shrine of Imam Reza in Mashad!

History

Shahr-e Kohn-e or Fereydoon Shahr

Shahr-e Kohn-e or Fereydoon Shahr is located in Farah city. This old and ancient city (Shahr-e Kohne) is more than 3000 years old. It was one of the ancient places of the persian kings because Farah belonged historically to the Sistan empire, so that is the reason why it is called Fereydoon Shar or Shahr-e Fereydoon: Fereydoon is a hero (with Rostam) in the persian book of Shahnameh which is known by ethnic-persians in Farah (Fars people) and Tajiks in Afghanistan quiet well.

Safavid Dynasty

Farah Province had been lost by the Safavids to the Uzbeks of Transoxiana, but was regained following a Safavid counter-offensive around 1600 CE, along with Herat and Sabzavar.[1]

The Saur Revolution and the Soviet-Afghan War

Following the Afghan communist coup in 1978, Farah was one of the cities in which civilian massacres were carried out by the now-dominant Khalqi communists against their political, ethnic, and religious opponents.[2] At the start of the 1980s, the majority of Farah was allied with the Harakat-i-Inqilab-i-Islami movement, but after 1981 the province split along linguistic lines, with Pashtun speaking opponents of the communist government remaining with Harakat, and Farsi-Dari speakers moving to the Jamiat-e Islami.[3]

Afghan Civil War

Following the 1992 collapse of the communist-backed Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, Farah Province, like Herat, Nimroz, and Badghis provinces, came under the influence of Herat-based powerbroker Ismail Khan. As the Taliban came to power, they sparred with Ismail Khan over Farah Province, as his occupation of the province and the strategic Shindand Airfield in its south stymied their efforts to seize Herat. The Taliban employed human wave tactics in an attempt to overtake the airfield. By late 1995, the stalemate broke as the Taliban counterattacked after Ismail Khan's failed drive to Kandahar, and all of Farah fell as the Taliban swept to take Herat on 5 September 1995.[4]

Taliban era

Due to its isolation from the Taliban's area of focus, Farah exerted some small level of local control during Taliban rule. By the end of the Taliban period, there were eight United Nations Development Program (UNDP) schools, for both boys and girls, recognized and supported by the Taliban in Kandahar and Farah. UNDP noted that the local authorities in Farah were "particularly cooperative" on the subject.[5]

Following the Coalition entry and union with the Northern Alliance following September 11, 2001, the Taliban withdrew from Farah due to the heavy Coalition aerial campaign, though ground troops were not sent to the province until some time later.[6][7]

Security Situation

Farah has not seen much fighting since the US backed overthrow of the Taliban in 2001, and is peaceful, relative to many parts of the country. Although there has been sporadic heavy combat in the Bala Baluk, and Gulestan districts. However, mountainous Eastern Farah has seen at least one US offensive against Taliban forces. In February 2005, the Taliban killed an aid worker in northern Farah and there was a failed Taliban assassination attempt on the governor. Due to its proximity to the restive Helmand and Uruzgan provinces, Farah has experienced problems with roaming insurgent gangs moving through the province and occupying parts of the province for brief periods of time [8]. Incidents of this type have increased as Taliban fighters face heavy pressure from ISAF offensives in the south.

Farah Province roads have seen massive improvement since May 2005 and are still being improved to date April 2006. The education system has been greatly improved and a great number of illegal weapons have been collected and destroyed in the province as testimony to the Provincial Reconstruction Team.

In May 2009, an American airstrike in the village of Granai in Bala Buluk District occurred that killed a large number of civilians. American authorities are investigating the incident. According to the New York Times, the villagers say that 147 were killed, an independent Afghan human rights group says 117 were killed, but the American authorities are skeptical that even 100 were killed. The Americans claim the airstrike was targeting Taliban militants, but villagers say that the Taliban had left by the time the airstrike occurred.[9] On May 19, the U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan Karl Eikenberry visited Farah town to talk with the survivors. He promised that "the United States will work tirelessly with your government, army and police to find ways to reduce the price paid by civilians, and avoid tragedies like what occurred in Bala Baluk."[10]

Land mines

A 1995 Oxfam report lists Farah as "severely mined", and indicated that Farah was particularly problematic due to the wide variety of mine devices employed there, as well as usage of mines to deny access to irrigation systems.[11]

Demographics

Farah province has a Pashtun majority of 80%.[12] Tajiks or better to say Persian (Fars) live around the capital city (Yazdi in Farah: people from Yazd in Iran migrated to Farah and called a small part of the capital "Yazdi") and are 14% of the population. Balochs are concentrated in the south of the province. There are also some Aimaks and Hazaras.

Pashtun tribes

The primary Pashtun tribes in Farah Province are the Alizai, Barakzai, and Nurzai.[13]

Politics

Governors

Districts

| District | Capital | Population[14] | Area[15] | Notes[16] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anar Dara | 24,782 | 70% Tajik, 30% Pashtun | ||

| Bakwa | 39,871 | 100% Pashtun | ||

| Bala Buluk | 72,465 | 95% Pashtun, 5% Tajik | ||

| Farah | Farah | 109,409 | 85% Pashtun, 10% Tajik, 5% other | |

| Gulistan | 49,774 | 80% Pashtun, 20% Tajik | ||

| Khaki Safed | 34,600 | 99% Pashtun, 1% Tajik | ||

| Lash Wa Juwayn | 20,499 | 50% Pashtun, 50% Tajik | ||

| Pur Chaman | 51,626 | 95% Tajik, 5% Pashtun | ||

| Pusht Rod | 36,315 | 99% Pashtun, 1% Tajik | ||

| Qala-I-Kah | 30,653 | 70% Pashtun, 30% Tajik | ||

| Shib Koh | 23,013 | 70% Pashtun, 15% Tajik, 15% other |

References

- ^ William Bayne Fisher. The Cambridge history of Iran. Cambridge University Press, 1986. ISBN 0521200946, 9780521200943

- ^ Olivier Roy. Islam and resistance in Afghanistan. Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0521397006, 9780521397001. Pg 97

- ^ Olivier Roy. Islam and resistance in Afghanistan. Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0521397006, 9780521397001

- ^ Peter Marsden. The Taliban: war, religion and the new order in Afghanistan. Palgrave Macmillan, 1998. ISBN 1856495221, 9781856495226

- ^ Susan Hawthorne, Bronwyn Winter. September 11, 2001: feminist perspectives. Spinifex Press, 2002. ISBN 1876756276, 9781876756277

- ^ Malalai Joya. A Woman Among Warlords: The Extraordinary Story of an Afghan Who Dared to Raise Her Voice. Simon and Schuster, 2009. ISBN 143910946X, 9781439109465

- ^ Harvey Langholtz, Boris Kondoch, Alan Wells. International Peacekeeping: The Yearbook of International Peace Operations. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2003. ISBN 9041121919, 9789041121912

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/20/world/asia/20afghan.html?ref=world

- ^ Shawn Roberts, Jody Williams. After the guns fall silent: the enduring legacy of landmines. Oxfam, 1995. ISBN 085598337X, 9780855983376

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

npswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Farah Province. Program for Conflict and Culture Studies, (US) Naval Postgraduate School

- ^ http://www.mrrd.gov.af/nabdp/Provincial%20Profiles/Farrah%20PDP%20Provincial%20profile.pdf

- ^ Afghanistan Geographic & Thematic Layers

- ^ http://www.aims.org.af/ssroots.aspx?seckeyt=364