Bhagavad Gita

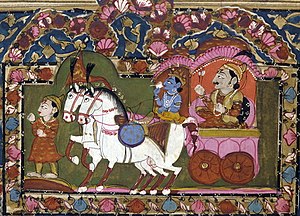

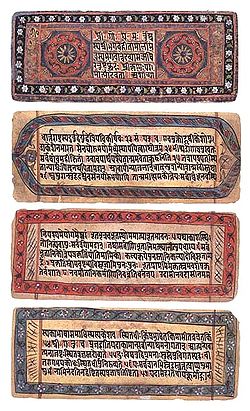

The Bhagavad Gītā (Sanskrit: भगवद्गीता, IPA: [ˈbʱəɡəʋəd̪ ɡiːˈtɑː], Song of God), also more simply known as Gita, is a sacred Hindu scripture,[1][2] considered among the most important texts in the history of literature and philosophy.[3] The Bhagavad Gita comprises roughly 700 verses, and is a part of the Mahabharata. The teacher of the Bhagavad Gita is Lord Krishna, who is revered by Hindus as a manifestation of God (Parabrahman) itself,[3] and is referred to within as Bhagavan, the Divine One.[4]

The content of the Gita is the conversation between Lord Krishna and Arjuna taking place on the battlefield before the start of the Kurukshetra war. Responding to Arjuna's confusion and moral dilemma about fighting his own cousins, Lord Krishna explains to Arjuna his duties as a warrior and prince, and elaborates on different Yogic[5] and Vedantic philosophies, with examples and analogies. This has led to the Gita often being described as a concise guide to Hindu theology and also as a practical, self-contained guide to life. During the discourse, Lord Krishna reveals His identity as the Supreme Being Himself (Svayam Bhagavan), blessing Arjuna with an awe-inspiring vision of His divine universal form.[citation needed]

The direct audience to Lord Krishna’s discourse of the Bhagawata Gita included Arjuna (addressee), Sanjay (using Divya Drishti gifted by Rishi Veda Vyasa) and Lord Hanuman (perched atop Arjuna’s chariot) and Barbarika, son of Ghatotghaj, who also witnessed the complete 18 days of action at Kurukhsetra.

The Bhagavad Gita is also called Gītopaniṣad, implying its having the status of an Upanishad, i.e. a Vedantic scripture.[6] Since the Gita is drawn from the Mahabharata, it is classified as a Smṛiti text. However, those branches of Hinduism that give it the status of an Upanishad also consider it a śruti or "revealed" text.[7][8] As it is taken to represent a summary of the Upanishadic teachings, it is also called "the Upanishad of the Upanishads".[1] Another title is mokṣaśāstra, or "Scripture of Liberation".[9]

Date and text

The Bhagavad Gita occurs in the Bhishma Parva of the Mahabharata and comprises 18 chapters from the 25th through 42nd and consists of 700 verses.[10] Its authorship is traditionally ascribed to Vyasa, the compiler of the Mahabharata.[11][12] Because of differences in recensions, the verses of the Gita may be numbered in the full text of the Mahabharata as chapters 6.25–42 or as chapters 6.23–40.[13] According to the recension of the Gita commented on by Shankaracharya, the number of verses is 700, but there is evidence to show that old manuscripts had 745 verses.[14] The verses themselves, using the range and style of Sanskrit meter (chhandas) with similes and metaphors, are written in a poetic form that is traditionally chanted.[citation needed]

The Bhagavad Gītā appeared later than the great movement represented by the early Upanishads and earlier than the period of the development of the philosophic systems and their formulation. The date and authorship of the Gītā are not known with certainty and scholars of an earlier generation opined that it was composed between the 5th and the 2nd century BCE.[11][15][16] Radhakrishnan, for example, asserted that the origin of the Gītā is in the pre-Christian era.[11] More recent assessments of Sanskrit literature, however, have tended to bring the chronological horizon of the texts down in time. In the case of the Gītā, John Brockington has now made cogent arguments that it can be placed in the first century CE.[17] Based on claims of differences in the poetic styles, some scholars like Jinarajadasa have argued that the Bhagavad Gītā was added to the Mahābhārata at a later date.[18][19]

Within the text of the Bhagavad Gītā itself, Lord Krishna states that the knowledge of Yoga contained in the Gītā was first instructed to mankind at the very beginning of their existence.[20] Although the original date of composition of the Bhagavad Gita is not clear, its teachings are considered timeless and the exact time of revelation of the scripture is considered of little spiritual significance by scholars like Bansi Pandit, and Juan Mascaro.[1][21] Swami Vivekananda dismisses concerns about differences of opinion regarding the historical events as unimportant for study of the Gita from the point of acquirement of Dharma.[22]

Prelude

The Mahabharata centers on the exploits of the Pandavas and the Kauravas, two families of royal cousins descended from two brothers, Pandu and Dhritarashtra, respectively. Because Dhritarashtra was born blind, Pandu inherited the ancestral kingdom, comprising a part of northern India around modern Delhi. The Pandava brothers were Yudhishthira the eldest, Bhima, Arjuna, Nakula, and Sahadeva. The Kaurava brothers were one hundred in number, Duryodhana being the eldest. When Pandu died at an early age, his young children were placed under the care of their uncle Dhritarashtra who usurped the throne.[23][24]

The Pandavas and the Kauravas were brought up together in the same household and had the same teachers, the most notable of whom were Bhishma and Dronacharya.[24] Bhishma, the wise grandsire, acted as their chief guardian, and the brahmin Drona was their military instructor. The Pandavas were endowed with righteousness, self-control, nobility, and many other knightly traits. On the other hand, the hundred sons of Dhritarashtra, especially Duryodhana, were endowed with negative qualities and were cruel, unrighteous, unscrupulous, greedy, and lustful. Duryodhana, jealous of his five cousins, contrived various means to destroy them.[25]

When the time came to crown Yudhisthira, eldest of the Pandavas, as prince, Duryodhana, through a fixed game of dice, exiled the Pandavas into the forest.[24] On their return from banishment the Pandavas demanded the return of their legitimate kingdom. Duryodhana, who had consolidated his power by many alliances, refused to restore their legal and moral rights. Attempts by elders and Krishna, who was a friend of the Pandavas and also a well wisher of the Kauravas, to resolve the issue failed. Nothing would satisfy Duryodhana's inordinate greed.[26][27]

War became inevitable. Both Duryodhana and Arjuna requested Krishna to support them in the war, since he possessed the strongest army, and was revered as the wisest teacher and the greatest yogi. Krishna offered to give his vast army to one of them and to become a charioteer and counselor for the other, but he would not touch any weapon nor participate in the battle in any manner.[26] While Duryodhana chose Krishna's vast army, Arjuna preferred to have Krishna as his charioteer.[28] The whole realm responded to the call of the Pandavas and the Kauravas. The kings, princes, and knights of India with their armies assembled on the sacred plain of Kurukshetra.[26] The blind king Dhritarashtra wished to follow the progress of the battle. The sage Vyasa offered to endow him with supernatural sight, but the king refused the boon, for he felt that the sight of the destruction of those near and dear to him would be too much to bear. Thereupon, Vyasa bestowed supernatural sight on Sanjaya, who was to act as reporter to Dhritarashtra. The Gita opens with the question of the blind king to Sanjaya regarding what happened on the battlefield when the two armies faced each other in battle array.[29]

Back ground

Scripture of Yoga

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

The Gita addresses the discord between the senses and the intuition of cosmic order. It speaks of the Yoga of equanimity, a detached outlook. The term Yoga covers a wide range of meanings, but in the context of the Bhagavad Gita, describes a unified outlook, serenity of mind, skill in action and the ability to stay attuned to the glory of the Self (Atman) and the Supreme Being (Bhagavan). According to Krishna, the root of all suffering and discord is the agitation of the mind caused by selfish desire. The only way to douse the flame of desire is by simultaneously stilling the mind through self-discipline and engaging oneself in a higher form of activity.

However, abstinence from action is regarded as being just as detrimental as extreme indulgence. According to the Bhagavad Gita, the goal of life is to free the mind and intellect from their complexities and to focus them on the glory of the Self by dedicating one's actions to the divine. This goal can be achieved through the Yogas of meditation, action, devotion and knowledge. In the sixth chapter, Krishna describes the best Yogi as one who constantly meditates upon him[30] - which is understood to mean thinking of either Krishna personally, or the supreme Brahman - with different schools of Hindu thought giving varying points of view.

Krishna summarizes the Yogas through eighteen chapters. Three yogas in particular have been emphasized by commentators:

- Bhakti Yoga or Devotion,

- Karma Yoga or Selfless Action

- Jnana Yoga or Self Transcending Knowledge

While each path differs, their fundamental goal is the same - to realize Brahman (the Divine Essence) as being the ultimate truth upon which our material universe rests, that the body is temporal, and that the Supreme Soul (Paramatman) is infinite. Yoga's aim (moksha) is to escape from the cycle of reincarnation through realization of the ultimate reality. There are three stages to self-realization enunciated from the Bhagavad Gita:

- Brahman - The impersonal universal energy

- Paramatma - The Supreme Soul sitting in the heart of every living entity.

- Bhagavan - God as a personality, with a transcendental form.

Major themes of yoga

The influential commentator Madhusudana Sarasvati (b. circa 1490) divided the Gita's eighteen chapters into three sections, each of six chapters. According to his method of division, the first six chapters deal with Karma Yoga, which is the means to the final goal, and the last six deal with the goal itself, which he says is Knowledge (Jnana). The middle six deal with bhakti.[31] Swami Gambhirananda characterizes Madhusudana Sarasvati's system as a successive approach in which Karma yoga leads to Bhakti yoga, which in turn leads to Jnana yoga.[32]

Karma Yoga

Karma Yoga is essentially Acting, or doing one's duties in life as per his/her dharma, or duty, without concern of results - a sort of constant sacrifice of action to the Supreme. It is action done without thought of gain. In a more modern interpretation, it can be viewed as duty bound deeds done without letting the nature of the result affect one's actions. Krishna advocates Nishkam Karma (Selfless Action) as the ideal path to realize the Truth. The very important theme of Karma Yoga is not focused on renouncing the work, but again and again Krishna focuses on what should be the purpose of activity. Krishna mentions in following verses that actions must be performed to please the Supreme otherwise these actions become the cause of material bondage and cause repetition of birth and death in this material world. These concepts are described in the following verses:

- "Work done as a sacrifice for Vishnu has to be performed, otherwise work causes bondage in this material world. Therefore, O son of Kuntī, perform your prescribed duties for His satisfaction, and in that way you will always remain free from bondage."[33]

- "To action alone hast thou a right and never at all to its fruits; let not the fruits of action be thy motive; neither let there be in thee any attachment to inaction"(2.47)[34]

- "Fixed in yoga, do thy work, O Winner of wealth (Arjuna), abandoning attachment, with an even mind in success and failure, for evenness of mind is called yoga"(2.48)[35]

- "With the body, with the mind, with the intellect, even merely with the senses, the Yogis perform action toward self-purification, having abandoned attachment. He who is disciplined in Yoga, having abandoned the fruit of action, attains steady peace..."[36]

In order to achieve true liberation, it is important to control all mental desires and tendencies to enjoy sense pleasures. The following verses illustrate this:[37]

- "When a man dwells in his mind on the object of sense, attachment to them is produced. From attachment springs desire and from desire comes anger."(2.62)[37]

- "From anger arises bewilderment, from bewilderment loss of memory; and from loss of memory, the destruction of intelligence and from the destruction of intelligence he perishes"(2.63)[37]

Bhakti Yoga

According to Catherine Cornille, Associate Professor of Theology at Boston College, "The text [of the Gita] offers a survey of the different possible disciplines for attaining liberation through knowledge (jnana), action (karma) and loving devotion to God (bhakti), focusing on the latter as both the easiest and the highest path to salvation."[38]

In the introduction to Chapter Seven of the Gita, bhakti is summed up as a mode of worship which consists of unceasing and loving remembrance of God. As M. R. Sampatkumaran explains in his overview of Ramanuja's commentary on the Gita, "The point is that mere knowledge of the scriptures cannot lead to final release. Devotion, meditation and worship are essential."[39]

As Krishna says in the Bhagavad Gita:

- "And of all yogins, he who full of faith worships Me, with his inner self abiding in Me, him, I hold to be the most attuned (to me in Yoga)."[40]

- "After attaining Me, the great souls do not incur rebirth in this miserable transitory world, because they have attained the highest perfection."[41]

- "... those who, renouncing all actions in Me, and regarding Me as the Supreme, worship Me... For those whose thoughts have entered into Me, I am soon the deliverer from the ocean of death and transmigration, Arjuna. Keep your mind on Me alone, your intellect on Me. Thus you shall dwell in Me hereafter."[42]

- "And he who serves Me with the yoga of unswerving devotion, transcending these qualities [binary opposites, like good and evil, pain and pleasure] is ready for liberation in Brahman."[43]

- "Fix your mind on Me, be devoted to Me, offer service to Me, bow down to Me, and you shall certainly reach Me. I promise you because you are My very dear friend."[44]

- "Setting aside all meritorious deeds (Dharma), just surrender completely to My will (with firm faith and loving contemplation). I shall liberate you from all sins. Do not fear."[45]

Jnana Yoga

Jnana Yoga is a process of learning to discriminate between what is real and what is not, what is eternal and what is not.[citation needed] Through a steady advancement in realization of the distinction between Real and the Unreal, the Eternal and the Temporal, one develops into a Jnani. This is essentially a path of knowledge and discrimination in regards to the difference between the immortal soul (atman) and the body.[citation needed]

In the second chapter, Krishna’s counsel begins with a succinct exposition of Jnana Yoga. Krishna argues that there is no reason to lament for those who are about to be killed in battle, because never was there a time when they were not, nor will there be a time when they will cease to be. Krishna explains that the self (atman) of all these warriors is indestructible. Fire cannot burn it, water cannot wet it, and wind cannot dry it. It is this Self that passes from body to another body like a person taking worn out clothing and putting on new ones. Krishna’s counsel is intended to alleviate the anxiety that Arjuna feels seeing a battle between two great armies about to commence. However, Arjuna is not an intellectual.[citation needed] He is a warrior, a man of action, for whom the path of action, Karma Yoga, is more appropriate.

- "When a sensible man ceases to see different identities due to different material bodies and he sees how beings are expanded everywhere, he attains to the Brahman conception."[46]

- "Those who see with eyes of knowledge the difference between the body and the knower of the body, and can also understand the process of liberation from bondage in material nature, attain to the supreme goal."[47]

Eighteen Yogas

In Sanskrit editions of the Gita, the Sanskrit text includes a traditional chapter title naming each chapter as a particular form of yoga. These chapter titles do not appear in the Sanskrit text of the Mahabharata.[48] Since there are eighteen chapters, there are therefore eighteen yogas mentioned, as explained in this quotation from Swami Chidbhavananda:

All the eighteen chapters in the Gita are designated, each as a type of yoga. The function of the yoga is to train the body and the mind.... The first chapter in the Gita is designated as system of yoga. It is called Arjuna Vishada Yogam - Yoga of Arjuna's Dejection.[49]

In Sanskrit editions, these eighteen chapter titles all use the word yoga, but in English translations the word yoga may not appear. For example, the Sanskrit title of Chapter 1 as given in Swami Sivananda's bilingual edition is arjunaviṣādayogaḥ which he translates as "The Yoga of the Despondency of Arjuna".[50] Swami Tapasyananda's bilingual edition gives the same Sanskrit title, but translates it as "Arjuna's Spiritual Conversion Through Sorrow".[51] The English-only translation by Radhakrishnan gives no Sanskrit, but the chapter title is translated as "The Hesitation and Despondency of Arjuna".[52] Other English translations, such as that by Zaehner, omit these chapter titles entirely.[53]

Swami Sivananda's commentary says that the eighteen chapters have a progressive order to their teachings, by which Krishna "pushed Arjuna up the ladder of Yoga from one rung to another."[54] As Winthrop Sargeant explains, "In the model presented by the Bhagavad Gītā, every aspect of life is in fact a way of salvation."[55]

Message of the Gita

There are 6 arishadvargas, or evils that the Gita says one should avoid: kama (lust), krodha (anger), lobh (greed), moha (delusion), mada or ahankar (pride) and matsarya (jealousy). These are the negative characteristics which prevent man from attaining moksha (liberation from the birth and death cycle).

The Gita centers on the revelation of Vaishna monotheism, offering the alternative of just war, even against relatives, provided the aggression is in the "active and selfless defence of dharma", to the pacifist Hindu concept of non-violence.[56]

Some commentators have attempted to resolve the apparent conflict between the proscription of violence and ahimsa by allegorical readings. Gandhi, for example, took the position that the text is not concerned with actual warfare so much as with the "battle that goes on within each individual heart". Such allegorical or metaphorical readings are derived from the Theosophical interpretations of Subba Row, William Q. Judge and Annie Besant. Stephen Mitchell has attempted to refute such allegorical readings.[57]

Scholar Radhakrishnan writes that the verse 11.55 is "the essence of bhakti" and the "substance of the whole teaching of the Gita":[58]

He who does work for Me, he who looks upon Me as his goal, he who worships Me, free from attachment, who is free from enmity to all creatures, he goes to Me, O Pandava.

Scholar Steven Rosen summarizes the Gita in four basic, concise verses:[59]

"I am the source of all spiritual and material worlds. Everything emanates from me. The Wise who fully realize this engage in my devotional service and worship me with all their hearts." (10.8)

"My pure devotees are absorbed in thoughts of me, and they experience fulfillment and bliss by enlightening one another and conversing about me." (10.9)

"To those who are continually devoted and worship me with love, I give the understanding by which they can come to me." (10.10)

"Out of compassion for them, I, residing in their hearts, destroy with the shining lamp of knowledge the darkness born of ignorance." (10.11)

Ramakrishna said that the essential message of the Gita can be obtained by repeating the word several times,[60] "'Gita, Gita, Gita', you begin, but then find yourself saying 'ta-Gi, ta-Gi, ta-Gi'. Tagi means one who has renounced everything for God."[citation needed]

According to Swami Vivekananda, "If one reads this one Shloka — क्लैब्यं मा स्म गमः पार्थ नैतत्त्वय्युपपद्यते । क्षुद्रं हृदयदौर्बल्यं त्यक्त्वोत्तिष्ठ परंतप॥ — one gets all the merits of reading the entire Gita; for in this one Shloka lies imbedded the whole Message of the Gita.[61]

Do not yield to unmanliness, O son of Pritha. It does not become you. Shake off this base faint-heartnedness and arise, O scorcher of enemies! (2.3)

Mahatma Gandhi writes, "The object of the Gita appears to me to be that of showing the most excellent way to attain self-realization" and this can be achieved by selfless action, "By desireless action; by renouncing fruits of action; by dedicating all activities to God, i.e., by surrendering oneself to Him body and soul." Gandhi called Gita, The Gospel of Selfless Action.[62]

Eknath Easwaran writes that the Gita's subject is "the war within, the struggle for self-mastery that every human being must wage if he or she is to emerge from life victorious",[63] and "The language of battle is often found in the scriptures, for it conveys the strenuous, long, drawn-out campaign we must wage to free ourselves from the tyranny of the ego, the cause of all our suffering and sorrow".[64]

Influence

śrī bhagavān uvāca

kālo 'smi lokakṣayakṛt pravṛddho; lokān samāhartum iha pravṛttaḥ

ṛte 'pi tvā na bhaviṣyanti sarve; ye 'vasthitāḥ pratyanīkeṣu yodhāḥ (11:32 = MBh 6.33.32)

The Lord Said:

Doom am I, full-ripe, dealing death to the worlds, engaged in devouring mankind.

Even without your slaying them not one of the warriors, ranged for battle against thee, shall survive.

In a heterogeneous text, the Gita reconciles facets and schools of Hindu philosophy, including those of Brahmanical (orthodox Vedic) origin and the parallel ascetic and Yogic traditions. It had always been a creative text for Hindu priests and Yogis.[citation needed] Although it is not strictly part of the 'canon' of Vedic writings, almost all Hindu traditions draw upon the Gita as authoritative. For the Vedantic schools of Hindu philosophy, it belongs to one of the three foundational texts Prasthana Trayi (lit. "three points of departure"), the other two being the Upanishads and Brahma Sutras.

The Bhagavad Gita's emphasis on selfless service was a prime source of inspiration for Mahatma Gandhi.[citation needed]

J. Robert Oppenheimer, American physicist and director of the Manhattan Project, learned Sanskrit in 1933 and read the Bhagavad Gita in the original, citing it later as one of the most influential books to shape his philosophy of life. Upon witnessing the world's first nuclear test in 1945, he later claimed to have thought of the quotation "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds", verse 32 from Chapter 11 of the Bhagavad Gita.[65][66]

A 2006 report suggests that the Gita is replacing the influence of the "The Art of War" (ascendant in the 1980s and '90s) in the Western business community.[67]

Commentaries and translations

Classical commentaries

Traditionally the commentators belong to spiritual traditions or schools (sampradaya) and Guru lineages (parampara), which claim to preserve teaching stemming either directly from Krishna himself or from other sources, each claiming to be faithful to the original message. In the words of Hiriyanna, "[The Gita] is one of the hardest books to interpret, which accounts for the numerous commentaries on it - each differing from the rest in an essential point or the other."[68]

Different translators and commentators have widely differing views on what multi-layered Sanskrit words and passages signify, and their presentation in English depending on the sampradaya they are affiliated to.[citation needed] Especially in Western philology, interpretations of particular passages often do not agree with traditional views.

The oldest and most influential medieval commentary was that of the founder of the Vedanta school[69] of extreme 'non-dualism", Shankara (788-820 A. D.),[70] also known as Shankaracharya (Sanskrit: Śaṅkarācārya).[71] Shankara's commentary was based on a recension of the Gita containing 700 verses, and that recension has been widely adopted by others.[72] There is not universal agreement that he was the actual author of the commentary on the Bhagavad Gita that is attributed to him.[73] A key commentary for the "modified non-dualist" school of Vedanta[74] was written by Ramanujacharya (Sanskrit: Rāmānujacharya), who lived in the eleventh century A.D.[71][75] Ramanujacharya's commentary chiefly seeks to show that the discipline of devotion to God (Bhakti yoga) is the way of salvation.[76] The commentary by Madhva, whose dates are given either as (b. 1199 - d. 1276)[77] or as (b. 1238 - d. 1317),[55] also known as Madhvacharya (Sanskrit: Madhvācārya), exemplifies thinking of the "dualist" school.[71] Madhva's school of dualism asserts that there is, in a quotation provided by Winthrop Sargeant, "an eternal and complete distinction between the Supreme, the many souls, and matter and its divisions."[55] Madhva is also considered to be one of the great commentators reflecting the viewpoint of the Vedanta school.[78]

In the Shaiva tradition,[79] the renowned philosopher Abhinavagupta (10-11th century CE) has written a commentary on a slightly variant recension called Gitartha-Samgraha.[citation needed]

Other classical commentators include Nimbarka (1162 CE), Vallabha(1479 CE)., Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486 CE),[80] while Dnyaneshwar (1275-1296 CE) translated and commented on the Gita in Marathi, in his book Dnyaneshwari.

Independence movement

In modern times, notable commentaries were written by Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi, who used the text to help inspire the Indian independence movement.[81][82] Tilak wrote his commentary while in jail during the period 1910-1911 serving a six-year sentence imposed by the British colonial government in India for sedition.[83] While noting that the Gita teaches possible paths to liberation, his commentary places most emphasis on Karma yoga.[84] No book was more central to Gandhi's life and thought than the Bhagavadgita, which he referred to as his "spiritual dictionary".[85] During his stay in Yeravda jail in 1929,[86] Gandhi wrote a commentary on the Bhagavad Gita in Gujarati. The Gujarati manuscript was translated into English by Mahadev Desai, who provided an additional introduction and commentary. It was published with a foreword by Gandhi in 1946.[87][88] Mahatma Gandhi expressed his love for the Gita in these words: "I find a solace in the Bhagavadgītā that I miss even in the Sermon on the Mount. When disappointment stares me in the face and all alone I see not one ray of light, I go back to the Bhagavadgītā. I find a verse here and a verse there and I immediately begin to smile in the midst of overwhelming tragedies - and my life has been full of external tragedies - and if they have left no visible, no indelible scar on me, I owe it all to the teaching of Bhagavadgītā."[89]

Hindu revivalism and Neo-Hindu movements

Other notable modern commentators include Sri Aurobindo, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Swami Vivekananda, who took a syncretistic approach to the text.[90][91]

Swami Vivekananda, the follower of Sri Ramakrishna, was known for his commentaries on the four Yogas - Bhakti, Jnana, Karma and Raja Yoga. He drew from his knowledge of the Gita to expound on these Yogas. Swami Sivananda advises the aspiring Yogi to read verses from the Bhagavad Gita every day. Paramahamsa Yogananda, writer of the famous Autobiography of a Yogi, viewed the Bhagavad Gita as one of the world's most divine scriptures. A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, wrote Bhagavad-Gītā As It Is, a commentary on the Gita from the perspective of Gaudiya Vaishnavism. The work became the principal text for the modern Hare Krishna movement. In 1965, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi published his own commentary of the Gita and proclaimed his technique of Transcendental Meditation to be the "practical procedure for experiencing the field of absolute Being described by Lord Krishna."[92]

Scholarly translations

The first English translation of the Bhagavad Gita was done by Charles Wilkins in 1785.[93][94] In 1981, Larson listed more than 40 English translations of the Gita, stating that "A complete listing of Gita translations and a related secondary bibliography would be nearly endless" (p. 514[95]). He stated that "Overall... there is a massive translational tradition in English, pioneered by the British, solidly grounded philologically by the French and Germans, provided with its indigenous roots by a rich heritage of modern Indian comment and reflection, extended into various disciplinary areas by Americans, and having generated in our time a broadly based cross-cultural awareness of the importance of the Bhagavad Gita both as an expression of a specifically Indian spirituality and as one of the great religious "classics" of all time." (p. 518[95])

The Gita has also been translated into other European languages. In 1808, passages from the Gita were part of the first direct translation of Sanskrit into German, appearing in a book through which Friedrich Schlegel became known as the founder of Indian philology in Germany.[96]

Adaptations

Philip Glass retold the story of Gandhi's early development as an activist in South Africa through the text of the Gita in the opera Satyagraha. The entire libretto of the opera consists of sayings from the Gita sung in the original Sanskrit.[97] In Douglas Cuomo's Arjuna's dilemma, the philosophical dilemma faced by Arjuna is dramatized in operatic form with a blend of Indian and Western music styles.[98]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c Pandit, Bansi, Explore Hinduism, p. 27

- ^ Hume, Robert Ernest (1959), The world's living religions, p. 29

- ^ a b Nikhilananda, Swami, "Introduction", The Bhagavad Gita, p. 1

- ^

"Bhagavan". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network (ISKCON). Retrieved 2008-01-14.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Introduction to the Bhagavad Gita

- ^ The phrase marking the end of each chapter identifies the book as Gītopanishad. The book is identified as "the essence of the Upanishads" in the Gītā-māhātmya 6, quoted in the introduction to Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, A.C. (1983), Bhagavad-gītā As It Is, Los Angeles: The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust.

- ^ Thomas B. Coburn, "Scripture" in India: Towards a Typology of the Word in Hindu Life, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol. 52, No. 3 (Sep., 1984), pp. 435-459. JSTOR 1464202

- ^ Tapasyananda, p. 1.

- ^ Nikhilananda, Swami (1944), "Introduction", The Bhagavad Gita, Advaita Ashrama, p. xxiv

- ^ Swarupananda, Swami (1909), "FOREWORD", Srimad-Bhagavad-Gita

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Radhakrishnan, S. (2002), "Introductory Essay", The Bhagavad Gita, HarperCollins, pp. 14–15

- ^ Vivekananda, Swami, "Lectures and Discourses ~ Thoughts on the Gita", The Complete works of Swami Vivekananda, vol. 4

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI) electronic edition. Electronic text (C) Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune, India, 1999.

- ^ Gambhiranda (1997), p. xvii.

- ^

Juan Mascaro (2003), "Translator's introduction to 1962 edition", The Bhagavad Gita, Penguin Classics, p. xlviii

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zaehner, Robert Charles (1973), The Bhagavad-Gita, Oxford University Press, p. 7,

As with most major religious texts in India, no firm date can be assigned to the Gītā. It seems certain, however, that it was written later than the 'classical' Upanishads with the possible exception of the Maitrī which was post-Buddhistic. One would probably not be going far wrong if one dated it at some time between the fifth and the second centuries B. C.

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ John Brockington, The Sanskrit Epics (Leiden, 1998)

- ^ C. Jinarajadasa (1915). "The Bhagavad Gita". Theosophical Publishing House, Adyar, Madras. India. Archived from the original on May 23, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

…an analysis of the epic shows at once by differences of style and by linguistic and other peculiarities, that it was composed at different times and by different hands

- ^ For a brief review of the literature supporting this view see: Radhakrihnan, pp. 14-15.

- ^ Bhagavad Gita Chapter 4, Text 1: vivasvan manave praha, manur ikshvakave 'bravit

- ^

Mascaro, Juan, The Bhagavad Gita, p. xlviii,

Scholars differ as to the date of the Bhagavad Gita; but as the roots of this great poem are in Eternity the date of its revelation in time is of little spiritual importance.

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Vivekananda, Swami, "Thoughts on the Gita", The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, Advaita Ashrama,

One thing should be especially remembered here, that there is no connection between these historical researches and our real aim, which is the knowledge that leads to the acquirement of Dharma. Even if the historicity of the whole thing is proved to be absolutely false today, it will not in the least be any loss to us. Then what is the use of so much historical research, you may ask. It has its use, because we have to get at the truth; it will not do for us to remain bound by wrong ideas born of ignorance.

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Nikhilananda, Swami (1944), Introduction, p. xiii

- ^ a b c Rama, Swami (1985), Perennial Psychology of the Bhagavad Gita, Himalayan Institute Press, p. 10

- ^ Nikhilananda, Swami (1944), Introduction, pp. xiv–xv

- ^ a b c Nikhilananda, Swami (1944), Introduction, p. xvi

- ^ Rama, Swami (1985), Perennial Psychology of the Bhagavad Gita, Himalayan Institute Press, p. 11

- ^ Rama, Swami (1985), Perennial Psychology of the Bhagavad Gita, Himalayan Institute Press, p. 12

- ^ Nikhilananda, Swami (1944), Introduction, p. vii

- ^ A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. "Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Verse 6.47". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network (ISKCON). Retrieved 2008-01-14."And of all yogis, the one with great faith who always abides in Me, thinks of Me within himself, and renders transcendental loving service to Me -- he is the most intimately united with Me in yoga and is the highest of all. That is My opinion."

- ^ Gambhirananda (1998), p. 16.

- ^ Gambhiranda (1997), p. xx.

- ^ A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. "Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Verse 3.9". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network (ISKCON). Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- ^ Radhakrishnan 1993, p. 119

- ^ Radhakrishnan 1993, p. 120

- ^ A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. "Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Verse 5.11". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network (ISKCON). Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ a b c Radhakrishnan 1993, pp. 125-126

- ^ Cornille, Catherine, ed., 2006. Song Divine: Christian Commentaries on the Bhagavad Gita." Leuven: Peeters. p. 2.

- ^ For quotation and summarizing bhakti as "a mode of worship which consists of unceasing and loving remembrance of God" see: Sampatkumaran, p. xxiii.

- ^ Radhakrishan(1970), ninth edition, Blackie and son India Ltd., p.211, Verse 6.47

- ^ A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. "Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Verse 8.15". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network (ISKCON). Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. "Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Verse 12.6". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network (ISKCON). Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. "Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Verse 14.26". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network (ISKCON). Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. "Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Verse 18.65". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network (ISKCON). Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. "Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Verse 18.66". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network (ISKCON). Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. "Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Verse 13.31". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network (ISKCON). Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. "Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Verse 13.35". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network (ISKCON). Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ For example, the first line of the Bhagavad Gita is dhṛtarāşţra uvāca, which occurs immediately after the last line of the preceding chapter in the full Sanskrit text of the Mahabharata: | 6.23.1 dhṛtarāşţra uvāca | 6.23.1a dharmakşetre kurukṣetre samavetā yuyutsavaḥ || Source: Electronic text (C) Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune, India, 1999. Electronic edition downloaded from: [1].

- ^ Chidbhavananda, p. 33.

- ^ Sivananda, p. 3.

- ^ Tapasyananda, p. 13

- ^ Radhakrishnan, p. 79.

- ^ Zaehner, passim.

- ^ Sivananda, p. xvii.

- ^ a b c Sargeant, p. xix.

- ^ "Strength founded on the Truth and the dharmic use of force are thus the Gita's answer to pacifism and non-violence. Rooted in the ancient Indian genius, this third way can only be practised by those who have risen above egoism, above asuric ambition or greed. The Gita certainly does not advocate war; what it advocates is the active and selfless defence of dharma. If sincerely followed, its teaching could have altered the course of human history. It can yet alter the course of Indian history." Michel Danino, "Greatest Gospel of Spiritual Works" in New Indian Express (10 December 2000).

- ^ Steven J. Rosen, Krishna's Song (2007), ISBN 9780313345531, pp. 22f.

- ^ Radhakrishnan, S (1974), "XI. The Lord's Transfiguration", The Bhagavad Gita, HarperCollins, p. 289

- ^ Rosen, Steven, "The Bhagavad-Gita and the life of Lord Krishna", Essential Hinduism, p. 121

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Isherwood, Christopher (1964), "The Story Begins", Ramakrishna and his Disciples, p. 9

- ^ Vivekananda, Swami, "Thoughts on the Gita", The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, vol. 4, Advaita Ashrama

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Gandhi, M.K. (1933), "Introduction", The Gita According to Gandhi

- ^ Eknath Easwaran, The Bhagavad Gita (2007), ISBN 978-1586380199 p. 15.

- ^ Eknath Easwaran, The End of Sorrow: The Bahagavad Gita for Daily Living (vol 1) (1993), ISBN 978-0915132171 p. 24.

- ^ James A. Hijiya, "The Gita of Robert Oppenheimer" Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 144, no. 2 (June 2000). [2]

- ^ See Robert_Oppenheimer#Trinity for other refs

- ^ "Karma Capitalism". Business Week. The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. 2006-10-30. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Singh pp.54-55

- ^ For Shankara's commentary falling within the Vedanta school of tradition, see: Flood (1996), p. 124.

- ^ Dating for Shankara as 788-820 CE is from: Sargeant, p. xix.

- ^ a b c Zaehner, p. 3.

- ^ Gambhirananda (1997), p. xviii.

- ^ Flood (1996), p. 240.

- ^ For classification of Ramanujacharya's commentary as within the Vedanta school see: Flood (1996), p. 124.

- ^ Gambhirananda (1997), p. xix.

- ^ Sampatkumaran, p. xx.

- ^ Dating of 1199-1276 for Madhva is from: Gambhirananda (1997), p. xix.

- ^ For classification of Madhva's commentary as within the Vedanta school see: Flood (1996), p. 124.

- ^ For classification of Abhinavagupta's commentary on the Gita as within the Shaiva tradition see: Flood (1996), p. 124.

- ^ Singh p.55

- ^ For B. G. Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi as notable commentators see: Gambhiranda (1997), p. xix.

- ^ For notability of the commentaries by B. G. Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi and their use to inspire the independence movement see: Sargeant, p. xix.

- ^ Stevenson, Robert W., "Tilak and the Bhagavadgita's Doctrine of Karmayoga", in: Minor, p. 44.

- ^ Stevenson, Robert W., "Tilak and the Bhagavadgita's Doctrine of Karmayoga", in: Minor, p. 49.

- ^ Jordens, J. T. F., "Gandhi and the Bhagavadgita", in: Minor, p. 88.

- ^ For composition during stay in Yeravda jail in 1929, see: Jordens, J. T. F., "Gandhi and the Bhagavadgita", in: Minor, p. 88.

- ^ Desai, Mahadev. The Gospel of Selfless Action, or, The Gita According To Gandhi. (Navajivan Publishing House: Ahmedabad: First Edition 1946). Other editions: 1948, 1951, 1956.

- ^ A shorter edition, omitting the bulk of Desai's additional commentary, has been published as: Anasaktiyoga: The Gospel of Selfless Action. Jim Rankin, editor. The author is listed as M.K. Gandhi; Mahadev Desai, translator. (Dry Bones Press, San Francisco, 1998) ISBN 1-883938-47-3.

- ^ Quotation from M. K. Gandhi. Young India. (1925), pp. 1078-1079, is cited from Radhakrishnan, front matter.

- ^ For Sri Aurobindo, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, and Swami Vivekananda as notable commentators see: Sargeant, p. xix.

- ^ For Sri Aurobindo as notable commentators, see: Gambhiranda (1997), p. xix.

- ^ Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, On The Bhagavad Gita; A Translation and Commentary With Sanskrit Text Chapters 1 to 6, Chapter Two, Verse 42, p. 129 and pp. 470-472

- ^ Clarke, John James (1997), Oriental enlightenment, Routledge, pp. 58–59, ISBN 9780415133753

- ^ Winternitz, Volume 1, p. 11.

- ^ a b Gerald James Larson (1981), "The Song Celestial: Two centuries of the Bhagavad Gita in English", Philosophy East and West: A Quarterly of Comparative Philosophy, 31 (4), University of Hawai'i Press: 513–540, doi:10.2307/1398797.

- ^ What had previously been known of Indian literature in Germany had been translated from the English. Winternitz, Volume 1, p. 15.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (April 14, 2008). "Fanciful Visions on the Mahatma's Road to Truth and Simplicity". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (November 7, 2008). "Warrior Prince From India Wrestles With Destiny". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

References

- Chidbhavananda, Swami (1997), The Bhagavad Gita, Sri Ramakrishna Tapovanam

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Easwaran, Eknath (2007), The Bhagavad Gita, Nilgiri Press, ISBN 9781586380199

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Easwaran, Eknath (1975), The Bhagavad Gita for Daily Living Volume 1, Berkeley, California: The Blue Mountain Center of Meditation, ISBN 9780915132171

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Easwaran, Eknath (1979), The Bhagavad Gita for Daily Living Volume 2, Berkeley, California: The Blue Mountain Center of Meditation, ISBN 9780915132188

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Easwaran, Eknath (1984), The Bhagavad Gita for Daily Living Volume 3, Berkeley, California: The Blue Mountain Center of Meditation, ISBN 9780915132195

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Gambhirananda, Swami (1998), Madhusudana Sarasvati Bhagavad Gita: With the annotation Gūḍhārtha Dīpikā, Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, ISBN 81-7505-194-9

- Flood, Gavin (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43878-0

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Gambhirananda, Swami (1997), Bhagavadgītā: With the commentary of Śaṅkarācārya, Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, ISBN 81-7505-041-1

- Keay, John (2000), India: A History, Grove Press, ISBN 0-8021-3797-0

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Miller, Barbara Stoler (1986), The Bhagavad Gita, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-06468-3

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Minor, Robert N. (1986), Modern Indian Interpreters of the Bhagavadgita, Albany, New York: State University of New York, ISBN 0-88706-297-0

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Radhakrishnan, S. (1993), The Bhagavadgītā, Harper Collins, ISBN 81-7223-087-7

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Sampatkumaran, M. R. (1985), The Gītābhāṣya of Rāmānuja, Bombay: Ananthacharya Indological Research Institute

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Sargeant, Winthrop (2009; see article), The Bhagavad Gītā: Twenty-fifth Anniversary Edition, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1-4384-2841-3

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Singh, R. Raj (2006), Bhakti and Philosophy, Lexington Books, ISBN 0739114247

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Sivananda, Swami (1995), The Bhagavad Gita, The Divine Life Society, ISBN 81-7052-000-2

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Tapasyananda, Swami (1990), Śrīmad Bhagavad Gītā, Sri Ramakrishna Math, ISBN 81-7120-449-X

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Vivekananda, Swami (1998), Thoughts on the Gita, Delhi: Advaita Ashrama, ISBN 81-7505-033-0

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Winternitz, Maurice (1972), History of Indian Literature, New Delhi: Oriental Books

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Zaehner, R. C. (1969), The Bhagavad Gītā, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-501666-1

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Wood, Ernest (1954), The Bhagavad Gīta Explained. With a New and Literal Translation, Los Angeles: New Century Foundation Press

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (November 2010) |

- Original text

- Mahabharata 6.23–6.40 (sacred-texts.com)

- GRETIL etext of MBh 6 (text begins at 06,023)

- Translations and Commentaries

- 1890 translation by William Quan Judge

- 1900 translation by Sir Edwin Arnold

- The Gita According to Gandhi by Mahadev Desai of Mahatma Gandhi's 1929 Gujurati translation and commentary

- 1942 translation by Swami Sivananda

- 1971 translation by A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada entitled Bhagavad Gita As It Is with Sanskrit text and English commentary.

- 1988 translation by Ramananda Prasad

- 1992 translation and commentary by Swami Chinmayananda

- 1993 translation by Jagannatha Prakasa (John of AllFaith)

- 2001 translation by Sanderson Beck

- 2004 metered translation by Swami Nirmalananda Giri

- Six commentaries: by Adi Sankara, Ramanuja, Sridhara Swami, Madhusudana Sarasvati, Visvanatha Chakravarti and Baladeva Vidyabhusana (all in sanskrit)

- Essays on Gita by Sri Aurobindo

- Gita Supersite Original text, with several accompanying translations or commentaries in Sanskrit, English, or Hindi

- Srimad Bhagavad Gita

- Bhagavad-Gita Trust translation in multiple languages with audio and translation of commentary from the four authorized Vaishnava sampradayas

- Multiple English Translations

- Maharishi Mahesh Yogi on the Bhagavad-Gita, A New Translation and Commentary, Chapters 1-6

- Audio

- Recitation of verses in Sanskrit (MP3 format)

- Bhagavad Gita (As It Is) Complete produced by The International Society for Krishna Consciousness

- Bhagavad Gita in 6 Languages

- Journals

- "Bhagavad Gita for everyday living", The Vedanta Kesari, 95 (12), 2008-12-12, ISSN 0042-2983.