Skopje

Skopje

Скопjе | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Skopje Град Скопjе | |

Top: Kale Fortress. 2nd row: Makedonija Street, Millenium Cross. 3rd row: Macedonia Square, St. Clement of Ohrid Church. Bottom: Stone Bridge | |

| Country | |

| Municipality | File:Flag of Skopje.png Greater Skopje |

| Founded | Around 4000 B.C. |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Koce Trajanovski (VMRO-DPMNE) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,854 km2 (716 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 240 m (790 ft) |

| Population (2006)[1] | |

| • Total | 668,518 |

| • Density | 360/km2 (930/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 1000 |

| Area code | +389 02 |

| Car plates | SK |

| Patron saint | Virgin Mary |

| Website | skopje.gov.mk |

Skopje (Macedonian: Скопје, [ˈskɔpjɛ] ) is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Macedonia with about a third of the total population. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre. It was known in the Roman period under the name Scupi.

The territory of modern Skopje has been inhabited since at least 4000 BC; remains of Neolithic settlements have been found within the old Kale Fortress that overlooks the modern city centre. The settlement appears to have been founded around then by the Paionians, a people that inhabited the region. In 148 BC the city became part of the Roman province of Macedonia, established in 146 BC. When the Roman Empire was divided into eastern and western halves in 395 AD, Skupi came under Byzantine rule from Constantinople. During much of the early medieval period, the town was contested between the Byzantines and the Bulgarian Empire. From 1189 the town was part of the Serbian realm. In 1392 the city was conquered by the Ottoman Turks and they named the town Üsküp. The town stayed under Ottoman control over 500 years. At that time the city was famous for its oriental architecture. In 1912 city was conquered by the Kingdom of Serbia during the Balkan Wars and after the First World War the city became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Kingdom of Yugoslavia). In the Second World War the city was conquered by the Bulgarian Army, which was part of Axis powers. In 1944 it became the capital city of Democratic Macedonia (later Socialist Republic of Macedonia), which was a federal state, part of Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (later Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia). The city developed rapidly after World War II, but this trend was interrupted in 1963 when it was hit by a disastrous earthquake. In 1991 it became the capital centre of independent Macedonia.

Skopje is located on the upper course of the Vardar River and is located on a major north-south Balkan route between Belgrade and Athens. According to the 2006 official estimate, it has 668,518 inhabitants and is a center for metal-processing, chemical, timber, textile, leather, and printing industries. Industrial development of the city has been accompanied by development of the trade, logistics, and banking sectors, as well as an emphasis on the fields of culture and sport.

Etymology

The name of Skopje derives from an ancient name that is attested in antiquity as Latin Scupi, the name of a classical era Greco-Roman frontier fortress town[2] of Illyrian[3] or Paeonian origin.[4][5] In modern times, the city was known by its Ottoman Turkish pronunciation, Üsküp (Ottoman Turkish: اسكوب) during the time of Ottoman rule and the Serbian form Skoplje (Скопље) during the time of the Royal Yugoslavia between 1912 and 1941. Under Kingdom of Bulgaria (1941–1944) the city was called Skopie (Скопие). Since 1945, the official name of the city in Macedonian has been Skopje (Скопје), reflecting the Macedonian Cyrillic orthography for the local pronunciation. The city is called Shkup or Shkupi in Albanian and Skopia (Σκόπια) in Greek.

Geography

Skopje is located in the northern part of Macedonia, in the Skopje statistical region, in the centre of the Balkans, approximately halfway between Belgrade and Athens. The Vardar River, which originates near Gostivar, flows through the city then south passing the border into Greece and flowing into the Aegean Sea. The Vardar valley is surrounded by numerous hills and mountains. The city covers an average of 23 km from east to west and 9 km from north to south. Skopje is located at an elevation of 225 m (738 ft) above sea level. The city's land area is 1,854 km2 (716 sq mi).

Climate

The city experiences a humid subtropical climate (Koppen Cfa) near the boundary of the humid continental climate. The summers are hot and humid, and the winters are cold and wet and often snowy. In summer the temperatures are usually above 31 °C (88 °F), and sometimes, above 40 °C (104 °F). In spring and autumn, the temperatures range from 15 to 24 °C (59 to 75 °F). In the winter, the day temperatures are about 6 °C (43 °F), but in the nights they often fall below 0 °C (32 °F), even below −10 °C (14 °F) on some cold nights. The precipitations are evenly distributed throughout the year, being heaviest, from October to December and from April to June.

| Climate data for Skopje (1971-1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.3 (39.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

19.3 (66.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

5.1 (41.2) |

18.1 (64.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.4 (25.9) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

1.9 (35.4) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.1 (55.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.3 (52.3) |

6.3 (43.3) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

6.0 (42.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 33.6 (1.32) |

37.2 (1.46) |

35.8 (1.41) |

40.4 (1.59) |

61.8 (2.43) |

45.9 (1.81) |

33.6 (1.32) |

31.3 (1.23) |

41.0 (1.61) |

44.0 (1.73) |

56.3 (2.22) |

46.1 (1.81) |

507 (19.94) |

| Average precipitation days | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 75 |

| Source: [6] | |||||||||||||

Hydrography

In Skopje, the Vardar River is only sixty miles from its source near Gostivar. The flow in the city is almost equivalent to the flow at its delta, near Thessaloniki. The river makes a few large meanders in Skopje and is crossed by several bridges, five in number in the centre.

Several rivers flow into the Vardar in Skopje. The longest is the river Treska, which is 130 km long. Others include the Lepenec, Pčinja, Kadina Reka, Markova Rek and Pateška, which are all less than 70 km long.[7]

Skopje has two artificial lakes, Matka and Treska, supplied by the eponymous river and located just few kilometers outside the center. The channel Jakupica is a glacial lake.[7]

Geology

The seismic movements have formed an environment of medium mountains around the city. The city of Skopje on the west is bordered by Šar Mountains, on south by the Jakupica chain, which culminates at a point high 2533 m, and east by hills that form the early Osogovo Mountains, which mark the border between Macedonia and Bulgaria.[7]

The mountains are crowned and the highest point in the center of Skopje, is at on altitude of 1066 meters. It is far exceeded by the mountains Osoj, Skopska Crna Gora and Žeden which are have highness of 1506, 1260 and 1561 meters respectively.[7]

Some rivers, like the Matka, have dug a few ravines around the center. The canyon of Treska River is surrounded by some caves.[7]

Town planning

Skopje has a rather loose town planning, which is the result of an earthquake that destroyed 80% of the city in 1963.[8][9]

The centre of Skopje is thus formed of two municipalities separated by the Vardar. On the north bank of the river is Čair Municipality in which the Old Town is located, while the on the south bank is Centar Municipality which is the modern centre of the city.

Rebuilding after the earthquake was largely orchestrated by Kenzo Tange,[10] a Japanese architect and urban planner, who had drawn many plans for cities and towns, including the one for Hiroshima in 1949. The most significant accomplishment was the train station, which was built on an elevated platform over bridges and allows to separate traffic and pedestrians. The planning of the southern shore of the Vardar has been designed to accommodate 1,800 homes lost in the earthquake.[10]

The combination of the earthquake, Yugoslav social planning and UN funded plans created an environment in Skopje for some unusual building projects from the mid-1960s onwards. A notable example is the central post office; the central circular building of which was by architect Janko Konstantinov.[11]

Today, the city is still spreading in all directions and has a number of new developments.[12] The government has made plans to erect several statues, fountains, bridges and museums at a cost of about €200 million. The project has generated controversy. Critics have described the new landmark buildings as signs of a reactionary historicist esthetics.[13] The project has also been criticised for its cost and for the lack of representation of national minorities in the coverage of its set of statues and memorials.[13]

History

The site of modern Skopje has been inhabited since at least 4000 BC;[7] remains of Neolithic settlements have been found within the old Kale fortress that overlooks the modern city centre. The settlement appears to have been founded around then by the Paionians, a people that inhabited the region. In the 3rd century BC, Skopje and the surrounding area was invaded by the Dardani. Scupi, the ancient Skopje, came under Roman rule after the general Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus defeated Andriscus of Macedon in 148 BC, being at first part of the Roman province of Macedonia, established in 146 BC. The northward expansion of the empire in the course of the 1st century BC lead to the creation of the province of Moesia in Augustus's times, into which Scupi was incorporated. After the division of the province by Domitian in 86 AD, Scupi was elevated to colonia status, and became a seat of government within the new province of Moesia Superior. The district called Dardania (in Moesia Superior), was formed into a special province by Diocletian, with the capital at Naissus. From 395 AD, it passed into the hands of the Eastern Roman Empire (or Byzantine Empire). Scupi was probably a metropolitan see about the middle of the 5th century (Template:Lang-la).[14]

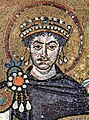

Becoming part of the Byzantine rule of Constantinople (today's Istanbul), Skupi became an important trading and garrison town for the region. The Byzantine Emperor Justinian (527–65 AD) was born in Tauresium[15] (about 20 km southeast of present-day Skopje) in 483 AD, and after Skupi was almost completely destroyed by an earthquake in 518 AD, Justinian built a new town at the fertile entry point of the River Lepenec into the Vardar. Some historians believe this might be the city of Justiniana Prima. During much of the early medieval period, the town was contested between the Byzantines and the Bulgarian Empire. From 972 to 992 it was the capital of the First Bulgarian Empire.[16] After 1018, it was a capital of Byzantine administrative region (katepanat) Bulgaria after the fall the First Bulgarian Empire in 1018. Skopje was a thriving trading settlement but fell into decline after being hit by another devastating earthquake at the end of the 11th century. In 1189 the town was part of the Serbian realm.[17]

It was a capital of the estate of the Bulgarian feudal lord, later Emperor Konstantin Asen in the middle of 13th century. The Byzantine Empire took advantage of the decline in Skopje to regain influence in the area, but lost control of it once again in 1282 to King Stefan Uroš II Milutin of Serbia. Milutin's grandson, Stefan Dušan, made Skopje his capital, from which he proclaimed himself as Emperor of Serbs and Greeks[7] in 1346, subsequently making it the capital of the Serbian Empire. After his sudden death in 1355, he was succeeded by Stephen Uroš V of Serbia who could not keep Serbian empire together and it was fragmented in many small principalities with Vuk Branković last Serbian and Christian prince that had Skopje under control during medieval period until it fell under Ottoman Control in 1392, for the next 520 years.

Rolling back Byzantine rule across much of the Balkans, the Ottoman Turks finally conquered Skopje in 1392 beginning 520 years of Ottoman rule.[18][19] The Ottomans pronounced the town Üsküb and named it as such. At first the Ottomans divided the greater Macedonian region into three vilayets, or districts — Üsküb (Kosovo), Manastir and Selanik – and as the northernmost of these, Üsküb was strategically important for further forays into central Europe. Under Ottoman rule the town moved further towards the entry point of the River Serava into the Vardar. Also the architecture of the town was changed accordingly. During the 15th century, many travelers' inns were established in the town, such as Kapan An and Suli An, which still exist today. The city's famous Stone Bridge (Kameni Most) – was also reconstructed during this period and the famous Daud Pasha baths (now a modern art gallery) was built at the end of the 15th century. At this time numerous Sephardic Jews driven out of Spain settled in Üsküb, adding to the cultural mix of the town and enhancing the town's trading reputation.[7]

At the beginning of Ottoman rule, several mosques sprang up in the city, and church lands were often seized and given to ex-soldiers, while many churches themselves were converted over time into mosques.[20] Üsküb was briefly occupied in 1689 by the Austrian General Piccolomini. He and his troops did not stay for long, however, as the town was quickly engulfed by the plague. On retreating from the town Piccolomini's troops set fire to Üsküb, perhaps in order to stamp out the plague, although some say this was done in order to avenge the 1683 Ottoman siege of Vienna.[7] For the next two centuries Üsküb's prestige waned and by the 19th century its population had dwindled to a mere 10,000. In 1873, however, the completion of the Üsküb—Selanik (now Skopje—Thessaloniki) railway brought many more travelers and traders to the town, so that by the turn of the century Üsküb had regained its former numbers of around 30,000.[7] Towards the end of the Ottoman Empire, Üsküb, along with other towns in Macedonia – Krusevo and Manastir (now Bitola) – became main hubs of rebellious movements against Ottoman rule. Üsküb was a key player in the Ilinden Uprising of August 1903 when the native population of the region declared the emergence of the Kruševo Republic. While the Kruševo Republic lasted only ten days before being quelled by the Ottomans, it was a sign of the beginning of the end for Ottoman rule. After 500 years of rule in the area the Ottomans were finally ousted in 1912 by the Serbian army during the first Balkan War.[18][21]

The Ottomans were shortly expelled from the city on August 12, 1912 by the local Albanian population when 15,000 Albanians marched on Üsküb.[22][23] The Turks, already weak from other battles against the united front of Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria during the First Balkan War, started to flee. When reinforcements to the Serbian royal army arrived some weeks later during the Battle of Kumanovo (50 km northeast of Skopje) it proved decisive in firmly driving out the Ottomans from all of Macedonia. Skopje remained under Serbian rule during the Second Balkan War of 1913 when the formerly united front started to fight amongst themselves. Treaty of London (1913) legitimated Serbian authority in contemporary Macedonia.[24] In 1912 also the official name was changed from Üsküb to Skoplje (Скопље). After the outbreak of World War I in 1914 the town was occupied by the Bulgarians. By 1918 it belonged to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and remained so until 1939, apart from a brief period of six months in 1920 when Skopje was controlled by the Yugoslav Communist Party. An ethnic Serb ruling elite dominated over the rest, continuing the repression wrought by previous Turkish rulers.[25]

In March 1941 when Yugoslavia entered the war, there were huge anti-war demonstrations in the streets of the town.[26] Skopje came under German occupation on 7 April 1941[27] and was later taken over by Bulgarian forces.[28] During the occupation, Bulgaria endowed Skopje with a national theatre, a library, a museum and for higher education the King Boris University.[29] However, on 11 March 1943, Skopje's entire Jewish population of 3,286 was deported to the gas chambers of Treblinka concentration camp in German-occupied Poland.[30] One month after the communists took power in Sofia and the Bulgarian army was sent to the west front to fight the Germans, Skopje was seized by the People's Liberation Army of Macedonia, and then joined Yugoslavia in 1944, when it became the capital of the newly established People's Republic of Macedonia.

From 1944 until 1991 Skopje was the capital of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia.[31] The city expanded and the population grew during this period from just over 150,000 in 1945 to almost 600,000 in the early 1990s. Continuing to be prone to natural disasters the city was flooded by the Vardar River in 1962 and then suffered considerable damage from a major earthquake[32][33] measuring 6.1 on the Richter scale, which killed over 1,000 people[32][34] and made another 120,000 homeless.[8][34] and numerous cultural monuments were seriously damaged. A major international relief effort saw the city rebuilt quickly, though much of its old neo-classical charm was lost in the process. The new master plan of the city was created by the then leading Japanese architect Kenzo Tange. The ruins of the old Skopje train station which was destroyed in the earthquake remain today as a memorial to the victims along with an adjacent museum. Nearly all of the city's beautiful neo-classical 18th and 19th century buildings were destroyed in the earthquake, including the National Theater and many government buildings, as well as most of the Kale Fortress. International financial aid poured into Skopje in order to help rebuild the city. As a result came the many modern (at the time) brutalist structures of the 1960s, that can still be seen today, such as the central post office building and the National Bank, as well as hundreds of now abandoned caravans and prefabricated mobile homes. Fortunately, though, as with previous earthquakes, much of the old Turkish side of town survived.

Skopje made the transition easily from the capital of the Socialist Federal Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia to the capital of today's Republic of Macedonia. Today, Skopje is seeing a makeover in buildings, streets and shops. The new VMRO–DPMNE government elected in July 2006 restored the Kale fortress and plans to rebuild the beautiful 19th century Army House, the Old National Theatre, and the Old National Bank of Macedonia – all destroyed in the 1963 earthquake. Other projects under construction are the "Macedonian Struggle" Museum, the Archeological Museum of Macedonia, National Archive of Macedonia, Constitutional Court, and a new Philharmonic Theater. The reconstruction of these buildings and also building monuments to the some most famous historic peoples of Macedonia are part of the project Skopje 2014, which should be completely over in the year of 2015. Also, the city's national stadium Philip II Arena [35][36] and the city's Alexander the Great Airport are also being reconstructed and expanded.[37][38]

Emblems

The Flag of Skopje[39] is a red vertical banner in proportions 1:2 with the coat of arms of the city in golden/yellow placed in its left upper quarter.[40]

The coat of arms of the city was adopted in the 1950s, and again in 1997 formalized. The Coat of arms of the City of Skopje has the form of a shield, whose upper side is semi arch turned inwards, the left and the right upper corner of the shield is made by two italic lines, whereas the bottom sides represent outwards round arches that end with a peak in the middle of the bottom span. The space around the shield contains: The Stone Bridge with the Vardar River, the fortress Kale and the snowy peaks of the Skopska Crna Gora mountain.[41]

Administrative divisions

Skopje is an administrative division within the Republic of Macedonia constituted of 10 municipalities. As such an administrative unit Skopje is the capital of the Republic of Macedonia. It is part of Skopje statistical region (Скопски регион).

The organisation of Skopje, as a distinct unit in local self-government is defined by the Law of Skopje.

| Nr. | Municipality (Општина) |

Area (km²) |

Population (2002) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 21.85 | 72,009 | |

| 6 | 54.79 | 36,154 | |

| 4 | Čair (Чаир) | 3.52 | 64,773 |

| 1 | 7.52 | 45,412 | |

| 2 | 110.86 | 72,617 | |

| 9 | Gjorče Petrov (Ѓорче Петров) | 66.93 | 41,634 |

| 8 | 35.21 | 59,666 | |

| 5 | 34.24 | 57,236 | |

| 10 | 229.06 | 35,408 | |

| 7 | 7.48 | 22,017 | |

| Total | 571.46 | 506,926 |

History of administration

- From 1976 until 1996 Macedonian Skopje was organised as a distinct social-political community comprising five municipalities: Gazi Baba, Karpoš, Kisela Voda, Centar and Čair.

- From 1996 to 2004 Skopje was defined as a distinct unit of the local self-government and had 7 municipalities: Gazi Baba, Karpoš, Kisela Voda, Centar and Čair, Šuto Orizari and Gjorče Petrov.

Government

The mayor of Skopje is elected directly. The current mayor is Koce Trajanovski. He was elected in April 2009.

Economy

Although Skopje had hosted economic plans since the nineteenth century, the Yugoslav communist regime, allowed the transformation of the city, which trasformed it into a major industrial center. It has been the largest economic and industrial center of Macedonia, but the closure of the Greek border and the change of the economic regime after the independence of the country has severely affected the secondary and tertiary industries.[12]

Indeed, in the port of Thessaloniki, Greece, formerly exported a significant share of Macedonian products and abandoning the Communist system has precipitated the closings and bankruptcies of formerly national companies. The conflict between Macedonians and ethnic Albanians had a negative impact on the economy by making investors wary of putting their money in such a market.[12]

The city still suffers mostly from lack of foreign investment, the brain drain to wealthier countries, outdated infrastructure and poor coordination of public services and enterprises.[12]

The unemployment rate in the city was 14.07% in 2002. It obtained a better result than the entire country, whose unemployment rate was approximately 19%. The same year, the city had about 64,000 companies.[12]

To solve its problems, the city relies on its integration in economic areas preferred, in particular through the European Union on the cleanup of factories and the city, education and development of tourism programs, and the use of tax-free economic zones such as Bunardzik just outside of Skopje.[12]

In addition to services, which are, as in all capitals, very important, particularly in the financial sector, Skopje has many factories. The most important activities are the processing of metals, chemicals including pharmaceuticals, textiles and leather, printing and etc.[42]

Population

Skopje is the most populous Macedonian city. According to the 2002 census,[43] the population of Skopje was 506,926 people. However, according to the 2006 official estimate, it has 668,518 inhabitants.[1]

Density

The City of Skopje has a density of 360.6 inhabitants per square kilometer. This figure is much lower than those of other European capitals, such as Belgrade (3,561 inhabitants per square kilometer), London (4,700) or Paris (20,433).

Ethnic groups

The Macedonians are the largest group with 338,358 people or 66.75% of the population. They are followed by Albanians, who are represented with 103,891 inhabitants, or 20.49% of the total population. Then come the Romani people with 23,475 inhabitants, or 4.63% of the total population of the city.[43]

The city also has a Serb minority population of 14,298 inhabitants – 2.82%; the Turks are represented with 8595 inhabitants or 1.70%, Bosniaks are represented with 7,585 people or 1.50%, and the Aromanians who are 2557 inhabitants or 0.50% of the total population. The remaining 1.61% corresponding to 8,167 people who declared themselves not covered by any of the preceding groups.[43]

The largest minority, the Albanians, have a privileged status in comparison to other minority groups due to their numbers. For example, they can use their language in local government and primary schools, and their language is official in the municipalities where at least 25% of the population is Albanian-speaking, in addition to the Macedonian official language. However, many Albanians and Roma who arrived as refugees from Kosovo did not return to their country, they do not hold Macedonian citizenship because it is granted after 15 years of residence in the national territory.[44]

Roma, who represent about 4.5% of the population,[43] experience a different integration. Most belong to the group Arlije who are sedentary, and the community Topanlije, which are present only in Skopje. They came mostly when the city was under the Ottoman Empire and settled heavily in the district "Topaana", where they made gunpowder for the Turks.[45]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 102,600 | — |

| 1953 | 139,200 | +35.7% |

| 1961 | 197,300 | +41.7% |

| 1971 | 312,300 | +58.3% |

| 1981 | 408,100 | +30.7% |

| 1994 | 448,200 | +9.8% |

| 2002 | 506,926 | +13.1% |

| 2006 | 668,518 | +31.9% |

| [46] | ||

Until the mid-twentieth century, Skopje still was a small town with a big role in the region, but it was generally small. Its status as a capital of a Federate Republic of Yugoslavia and the communist system, allowed the city to enjoy rapid industrialization and therefore large population growth. In 1948 only 9.6% of the country's total population lived in Skopje, but by 1994 the figure increased to roughly 25%.[47]

The earthquake in 1963, which destroyed 80% of the city and killed around 1,000 people annihilated Skopje, but it was quickly rebuilt with an international plan, and the population started to grow quickly. In 1948, the city had a population of 102,600 people, but in 1981 the population of city growth for four times more – 408,100.[48]

The disturbances that occurred in Yugoslavia during the 1980s put a brake on growth, and some other problems followed when the independence of Macedonia happened in 1991. As a result of that, between 1981 and 1994 Skopje gained only 40,100 inhabitants.

Health

The largest public hospital, founded in 1944, can accommodate 11,000 patients.[49] It is followed by the Institute for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology, which was opened in 1960.[50] The hospital Philip II specialized in cardiology was inaugurated in 2000[51] and The Clinical Centre, was founded in 2004. [52]

In 2003, the birthrate of the city was 10.6 ‰ and the mortality rate of 7.7 ‰.[53] The first figure is quite different from the national average, indicating a birth rate of 13.14 ‰, but the mortality rate is very close to the country's one, since 2003 obtained 7.83 ‰[54] Infant mortality is also very similar to the municipal and national, as the country obtained a rate of 11.74 ‰ in 2003 and Skopje had rate of 11.18 ‰.[53] That same year in Skopje, 99.5% of births took place in hospitals, a rate slightly above the national average of 98.6%.[53]

Education

The 2002 census found that the majority of citizens of the city, or 193,425 people, had stopped their education after finishing high school. The second group, 107,408 people had stopped after finishing their elementary school. 14,194 people had gone to university, 49,554 had received the equivalent of the baccalaureate, the equivalent of 1777 Masters and 1682 the equivalent of the PhD. Finally, 11,259 people had no education and 28 292 incomplete education. 97.5% of the population of the city over ten years of age is literate, and this figure is slightly higher than the national average, that has a value of 96.1%.[55] In general, the people from Skopje have easier access to education than other Macedonians.[56]

The city has several universities. The largest and the oldest is the Ss. Cyril and Methodius University. This public university was founded in 1949 and then had just three faculties. Since then it has expanded and today includes 23 faculties, 10 institutes and over 36,000 students.[57] Since the independence of Macedonia, new universities, mostly private which often follow American standards, have been opened.

The European University was established in 2001 and comprises the faculties of economics, computer science, law, political science and art and design.[58] FON University, founded in 2003, includes faculties of law, political science and international relations, foreign languages, investigation and security, environmental management, economics, technology and communication information, sports, design and multimedia and philosophy.[59] The American University College was opened in 2005 and manages with the faculties of business administration, political science, foreign languages, architecture and design, computer science and law.[60] TheYahya Kemal College (which is named after the Turkish poet Yahya Kemal Beyatlı, who was born in Skopje,) opened in 1996. Besides in Skopje, the college manages campuses in Gostivar and Struga.[61]

In 2008, Skopje had 21 colleges, whose specialties are quite varied (languages, engineering, architecture ...).[62]

Transport

Since the 1990s the city's position as a transportation hub is increasing in Southeast Europe since it stands at an intersection of two main European transport corridors – Corridor VIII (East-West) and Corridor X (North-South). This significance of the city has been enhanced by the construction of new highways on the two transversals, the new Skopje ring road, and the ongoing extension and modernization of Skopje Alexander the Great Airport.[38]

Airports:

Skopje has one international airport: Skopje Alexander the Great Airport located in the Petrovec Municipality, about 22 kilometers east from the city center. The airport has been given under concession to the Turkish company TAV, which is contracted to invest 200 Million Euros in the expansion and renovations of the Skopje and Ohrid Airports, as well as build a new Cargo Airport in Stip. Construction at Alexander The Great began intensively in March, 2010.

Highways:

The E75 highway connecting Vardø in Norway and Crete in Greece runs just east of Skopje, thus linking most of Europe with the Macedonian capital. The E75 highway in Macedonia connects Kumanovo, Veles, Negotino, and Gevgelija.

The E65 highway runs through the northern and western edges of the city and is part of the 26.5 km long Skopje Northern Bypass. The E65 in Macedonia also connects Tetovo, Gostivar, Kičevo, Ohrid and Bitola

Railways:

The Skopje Central Railway Station is approximately 2 kilometers east of the city center. It's part of the "Transportation Center" Complex built in the 1970s, to replace the first Railway station in the Balkans that was destroyed by the devastating 1963 earthquake. It has 10 platforms and is suspended on a massive concrete bridge about 2 km long.In 2010, Makedonski Železnici joined Cargo 10, a joint venture with other railways in the region.[63]

Buses:

The main Skopje bus station is 2 kilometers east of the city center, and is located in the Transportation Center that is also housing the central railway station. City buses run through the whole city connecting different urban areas and neighborhoods, as well as the smaller surrounding towns. In 2011 the old city buses will be replaced with 84 new buses, produced in Ukraine.[64] This is also the Hub of inter-city and international buses. There are several departures daily for Ohrid, Bitola, Thessaloniki, Belgrade, Sofia, and others.

Tramway:

The City of Skopje is planing to build a tramway transport across the city.[65]

Main sights

Landmarks

The present Skopje Kale Fortress was originally built by the Byzantines in the 6th century. After the 1963 earthquake, Kale’s circular, rectangular and square towers were conserved and restored. Today this fortress is the one of the best sightseeing spots in Skopje. The Stone Bridge is an important landmark of Skopje. It was built under the patronage of Sultan Mehmed II the Conqueror between 1451 and 1469. This bridge represents the connection between Skopje’s past and present and today is featured as the emblem of the city of Skopje.[41] The bridge is in Skopje's main square named after the country - Macedonia Square. It is dramatically widened by the destruction of the massive neoclassical National Bank and Army House during the 1963 earthquake. Apart of the Stone Bridge, one of the well known buildings is the Ristiḱ Palace. In 2010, two five meters tall monuments of Goce Delcev and Dame Gruev were erected near the Stone Bridge.[66]

The Old Town in the past was one of the largest and most significant oriental old bazaars in the Balkans.[67] The bazaar is a mixture of Eastern and Western culture. One of the most eminent mosques in the bazaar is the Mustapha Pasha Mosque which was built in 1492 by Mustafa Paşa on an older Christian site.[68] It is an endowment of Mustapha Pasha, an eminent figure in the Turkish state during the rule of Sultan Bayezid II and Sultan Selim I.[69]

The Kuršumli An is a former Turkish inn which features architecturally interesting arches and domes. Because lead was used to top the structure, it became known as the Lead Inn (Kursumli An, in Turkish "Kurşunlu Han"). It was built by Musein Odza, the son of a scientist at Sultan Selim II’s court, in the 16th century.[70] Now it is sharing its location with a national museum for Macedonia which is placed in the old Railway Station, halfly destroyed in the massive earthquake from 1963. Although Islamic architecture is predominant in the bazaar, there are several churches as well.

The Millennium Cross, situated on the peak of the mountain Vodno, is a tourist attraction. It was built to celebrate 2000 years of the existence of Christianity. The cross was built on the highest point of the Vodno mountain on a place known since the time of the Ottoman Empire as "Krstovar", meaning "Place of the cross", as there was a smaller cross situated there. There are several landmarks of Mother Teresa in Skopje, the city where she was born, including a marker of her birthplace, a statue, and a memorial house. The Memorial House of Mother Teresa in Skopje was opened in early 2009.[71] An ancient Roman aqueduct survives to the north of the city, near the village of Vizbegovo. One of stone bridges connecting both side of Vardar River dates back to the reign of Stefan Dušan. It is unclear when it was made. Under the Ottoman Empire it provided water for public baths. Today, 55 stone arches of the Skopje Aqueduct remain standing.

-

The Old Railway Station, today the National Museum of Macedonia

-

The Ristiḱ Palace at night.

-

Sculptures on the top of the Ristiḱ Palace

-

Statues of Goce Delchev and Dame Gruev

-

Monument of Mother Teresa next to her Memorial House

-

The Millennium Cross

-

Sunset at Skopje Fortress

-

Monument at the Fortress

-

Entrance to the Old Town

-

The Isa Bey Mosque

-

The Stone Bridge at night.

Churches

| Church | Description | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| Church of Holy Salvation | This church, one of the most famous landmarks in Skopje, was built in the 16th century and is located between the Old Bazaar and the Kale Fortress. The interior of this attraction is significant in art, as it features a giant iconostasis (altar) carved out of wood. Blending biblical figures and local scenery, the depictions themselves are of topical interest. Goce Delčev, a national hero in two countries for his involvement in the late 19th century struggle for Macedonian liberation, is buried in the church backyard. |

|

| Church of St. Panteleimon | The church of Saint Panteleimon in Gorno Nerezi near Skopje is a superb example of the Comnenian art on the all-Byzantine level. Commissioned by several members of the royal Comnenus family, the church was not finished until 1164. Nerezi is famous for its frescoes, representing a pinnacle of the 12th-century trend of intimacy and spirituality. They are often compared with similarly delicate works by Giotto, who worked 140 years later. These murals underwent serious 19th-century overpainting but were restored lately. |

|

| Church of St. Marko | The church was founded in 1345 and finished by King Marko in 1366, who is also the donor of the frescoes painted between 1366 and 1371. | File:St. marko.jpg |

| Church of St. Nikita | The church and a chapel dedicated to St. John the Baptist were built in 1307 - 1308. This church is well known for its frescoes. |

|

| Church of St. Andrea | The church was built in 1389. The frescoes are stylistically outstanding and they differ from the rest of Macedonian medieval monuments. |

|

| Church of St. Demetrius | The church was built in the 18th century on the place of an old church from the 13th century. This church was an Orthodox cathedral church before the construction of the present-day cathedral church of St. Clement of Ohrid. It is close to the eastern end of the Stone Bridge |

|

| Church of the Holy Mother of God | This cathedral church, dedicated to the Holy Mother of God, was built on the place of an old church also dedicated to the Holy Mother, built in 1204 and later completely destroyed in a fire. The old church was previously rebuilt and consecrated in 1835, but destroyed during the 1963 Skopje earthquake. The present-day church's reconstruction began on 2 October 2002. |

|

| Church of St. Clement | Built in 1972, the Orthodox church in one of few in the world to be designed in modern contemporary architecture. The main Macedonian orthodox cathedral church was consecrated in 1990, on the 1150th anniversary of the birth of the church patron, St. Clement of Ohrid. The iconostasis icons were painted by Gjorgi Danevski and Spase Spirovski and the frescoes were painted by the academic painter Jovan Petrov and his collaborators. |

|

| Church of St. Archangel Michael | Built in 1928 - 1932, this Orthodox church is located beside the British cemetery in the Gazi Baba municipality. |

|

| Church of St. Petka | Built in 1923 - 1924, this church is located near the old train station and city clinic. |

|

Culture

The Museum of Contemporary Arts Skopje, is one of the most important institution of Macedonia in discovering, treasuring and preserving the Contemporary Arts. Тhe international community manifested an exceptionally wide solidarity in assisting the reconstruction of Skopje. An important part of that solidarity was also the action initiated by the International Association of the Plastic arts which on its convention held in October 1963 in New York, called upon the artists of the world to assist in creating a collection of works of art by which they would support the vision of the city reconstruction. The building project was donated by the Polish Government which made a national competition to this and where the joint work of the Polish architects: J. Mokrzynski, E. Wierzbicki and W. Klyzewski was accepted. Having a total area of 5000 sq. m., the Museum building is made up of three connected wings which include the halls for temporary exhibitions, the premises for the permanent exhibition, the hall for lecturers, film and video presentation, the library and the archives, the administration, the conservation workshop, the depots and other departments. The great park areas, that enable the installation of various sculptural projects, as well as the spacious parking further relate to the immediate environment of the Skopje Museum of Contemporary Art.

There are also the Museum of Macedonia (archeological, ethnological and historical), the Natural history Museum, and the Archives of Macedonia.

The Skopje Jazz Festival has been held annually since 1981. The artists` profiles include fusion, acid jazz, Latin jazz, smooth jazz, and avant-garde jazz, which brings a great variety and richness to this festival. Ray Charles, Tito Puente, Gotan Project, Al Di Meola, Youssou N'Dour, just to name few, have taken part at this festival. The Skopje Jazz Festival is part of the European Jazz Network and The European Forum of World Wide Festivals. It is held in October.

The Skopje Cultural Summer Festival is renowned cultural event that takes place in Skopje each year during the summer. The festival is a member of the International Festivals and Events Association (IFEA) and it comprises musical concerts, operas, ballets and plays, art and photo-exhibitions, movies, performances and multimedia projects, that gather each year about 2 000 participants from around the world including St Petersburg Theatre, the Chamber Orchestra of the Bolshoi Theatre, Irina Arkhipova, Viktor Tretiakov (Russia), The Theatre of Shadows from Tehran (Iran), Michel Dalberto (France), David Burgess

Blues and Soul Festival is a relatively new event in the Macedonian cultural scene that occurs every summer between in early July.[72] Many important blues and soul figures have been guests, including Larry Coryell, Mick Taylor & All Stars Blues Band, Candy Dulfer & Funky Stuff, João Bosco, The Temptations, Tolo Marton Trio, Blues Wire, Phil Guy.

May Opera Evenings is a festival that occurs in Skopje since 1972 and it is dedicated to opera and making opera more popular among the public. It has evolved into a stage on which artists from some 50 countries across the globe have performed with distinction to high international standards.

The Open Youth Theatre Festival is established In May 1976 by a group of young enthusiasts.[73] More than 250 theatrical performances have been presented at this festival so far, most of them by alternative, experimental theatre groups engaging young writers and actors. Recently, the festival became a member of the Brussels Informal European Theatre Meeting (IETM). Within the framework of the Open Youth Theatre, a Macedonian National Centre of the International Theatre Institute (ITI) was established, and at the 25th ITI World Congress in Munich in 1993, it was received as a regular member of this theatre association. Now, the Open Youth Theatre festival is an international festival representing groups from the successor states of the former Yugoslavia, the United States, France, the Soviet Union, Russia, Spain, Japan, Poland, Italy, the United Kingdom, India and other countries.

Sports

As the capital and most important city in Macedonia, Skopje is home to several sports teams and venues. FK Vardar and FK Rabotnički are the two strongest and most popular football teams, whilst RK Kometal Gjorče Petrov is the most popular handball team. Skopje has four major sports indoor halls, of which the Boris Trajkovski Sports Center is the biggest. One of the most popular indoor halls is SRC Kale hall which was host of the EHF women's champions league final in 2000, 2002 and 2005. In 2002 RK Kometal Gjorče Petrov won the EHF women's champions league.[74] This was the biggest success of one Macedonian sport club. The main stadium is the Philip II Arena and it hosts the Macedonia national football team.

People from Skopje

Notable people from Skopje include:

|

Musicians: Politicians and businessmen:

|

Writers: Others:

|

-

Mother Teresa, Roman Catholic humanitarian

-

Milčo Mančevski, film director

-

Labina Mitevska, actress

-

Katarina Ivanovska, model

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

References

- ^ a b Град Скопје. "Skopje – Capital of the Republic of Macedonia". skopje.com. Retrieved 2010-12-24.

- ^ Watkins, Thomas H., "Roman Legionary Fortresses and the Cities of Modern Europe", Military Affairs, Vol. 47, No. 1 (Feb., 1983)

- ^ Babiniotis, Λεξικό της Νεοελληνικής Γλώσσας

- ^ N. G. L. Hammond, F. W. Walbank, A History of Macedonia: Volume III: 336-167 B.C., Oxford University Press, 1988, p.386

- ^ John Wilkes, The Illyrians, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996. p.86

- ^ "Climatological Normals of Skopje". Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Град Скопје. "Official portal of City of Skopje – History". Skopje.gov.mk. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ^ a b In Your Pocket. "The 1963 earthquake in Skopje". inyourcpocket.com. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ BBC. "On This Day: 26 July; 1963: Thousands killed in Yugoslav earthquake". bbc.com. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Yugoslavia,Worlds and Travels, Larousse, 1989, p. 115

- ^ Агенција за иселеништво на Република Македонија. "Јанко Константинов". makemigration.com. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) Template:Mk icon - ^ a b c d e f City of Skopje. "Strategy for Local Economic Development of the City of Skopje" (PDF). skopje.gov.mk. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Balkan Insight (24-06-2010). "Critics Lash 'Dated' Aesthetics of Skopje 2014". balkaninsight.com. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Catholic Encyclopedia. "Scopia". newadvent.org. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ M. Meier, Justinian, 29: "481 or 482"; Moorhead (1994), p. 17: "about 482"; Maas (2005), p. 5: "around 483".

- ^ Pavlov, Plamen (2002). Цар Самуил и "Българската епопея" (in Bulgarian). Sofia, Veliko Tarnovo: VMRO Rousse. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ^ World and Its Peoples – Google Böcker. Books.google.se. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ a b "Macedonia :: The Ottoman Empire". Britannica. 2010. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "A brief account of the history of Skopje". skopje.mk. 2010. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

A monk at the Saint Theodor Monastery on Mt. Vodno briefly recorded the date of the town's capture by the Turks: "In the 69th year (1392) the Turks took Skopje on the 6th day of the month (January 19, 1392 according to the new calendar).

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "The Church of St Spas - Skopje". National Tourism Portal of Macedonia. 2005-07. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

...half of it was constructed underground, due to the 17th century edict of the Turkish Sultan that prohibited Christian structures from being higher than mosques.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "AN OUTLINE OF MACEDONIAN HISTORY FROM ANCIENT TIMES TO 1991". Embassy of the Republic of Macedonia London. 2010. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

The period of expansion of medieval states on the Balkan and in Macedonia was followed by the occupation of the Ottoman Empire in the 14th century. Macedonia remained a part of the Ottoman Empire for 500 years, i.e. until 1912

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Jacques, Edwin E. (1994) The Albanians: an ethnic history from prehistoric times to the present McFarland, Jefferson, North Carolina, page 273, ISBN 0-89950-932-0

- ^ Jelavich, Barbara (1983) History of the Balkans: Twentieth Century (volume 2 of History of the Balkans) Cambridge University Press, New York, page 89, ISBN 0-521-27459-1

- ^ Zum (17-05-1913). "(HIS, P) Treaty of Peace between Greece, Bulgaria, Montenegro, Serbia on the one part and Turkey on the other part". skopje.gov.mk. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Rossos, Andrew (2008) Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, California, page 135, ISBN 978-0-8179-4881-8

- ^ Jancar-Webster, Barbara (1989) Women & Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945 Arden Press, Denver, Colorado, page 37, ISBN 0-912869-09-7

- ^ Schreiber, Gerhard; Stegemann, Bernd and Vogel, Detlef (1995) Germany and the Second World War, Vol. 3. The Mediterranean, south-east Europe, and North Africa (translated from German) Oxford Clarendon Press, Oxford, England, page 504, note 38 citing a Werhmacht report, ISBN 0-19-822884-8

- ^ Mitrovski, Boro; Glišić, Venceslav and Ristovski, Tomo (1971) The Bulgarian Army in Yugoslavia 1941–1945 (translated from Bugarska vojska u Jugoslaviji 1941–1945) Medunarodna politika, Belgrade, page 35, OCLC 3241584

- ^ Phillips, John (2004) Macedonia: warlords and rebels in the Balkans Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, page 32, ISBN 0-300-10268-2

- ^ Mitrovski, Boro; Glišić, Venceslav and Ristovski, Tomo (1971) The Bulgarian Army in Yugoslavia 1941–1945 (translated from Bugarska vojska u Jugoslaviji 1941–1945) Medunarodna politika, Belgrade, page 80, OCLC 3241584

- ^ Dr. Cvetan Cvetkovski, Skopje University, Faculty of Law. ""Constitutional history of the Republic of Macedonia"], section "1. Creation of the contemporary Macedonian state during the Second World War (1941–1945)", Centre for European Constitutional Law". cecl.gr. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Department of Earth Sciences, University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy. "Seismic Ground Motion Estimates for the M6.1 earthquake of July 26, 1963 at Skopje, Republic of Macedonia" (PDF). units.it. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology. "1963 Skopje (Macedonia) Earthquake, SeismoArchives". iris.edu. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Marking the 44th anniversary of the catastrophic 1963 Skopje earthquake MRT, Thursday, 26 July 2007

- ^ Dnevnik newspaper (2008-28-12). "Скопскиот стадион ќе се вика „Арена Филип Македонски"". dnevnik.com.mk. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) Template:Mk icon - ^ Dnevnik newspaper. "Macedonia to host Spain". macedonianfootball.com. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Večer Online. "Близу Александар Велики ќе се гради хотел де лукс". vecer.com.mk. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) Template:Mk icon - ^ a b World Bulletin (2008-25-11). "Turkey's TAV signs deal for Macedonian airports". worldbulletin.net. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Град Скопје. "City symbols". skopje.gov.mk. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ^ Flagspot. "Skopje (Capital city, Macedonia)". flagspot.net. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ^ a b Heraldry of the World (ngw.nl). Heraldry of the World "City symbols". Retrieved 2011-01-30.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Encarta Encyclopedia, 2008 – Skopje

- ^ a b c d Government of the Republic of Macedonia. "2002 census results" (PDF). stat.gov.mk. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ The Republic of Macedonia: A newcomer in the European community, eds. Christophe Chiclet and Bernard Lory, Les Cahiers de Confluence, ed. The harmattan, 1998, p. 67

- ^ cit.eds. Christophe Chiclet and Bernard Lory, Les Cahiers de Confluence, ed. The harmattan, 1998, p. 78

- ^ Op. cit., Georges Castellan, éd. Arméline, 2003, p. 78

- ^ Central and Eastern European Library. "Macedonian census results – controversy or reality?". ceeol.com. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Op. cit., Georges Castellan, éd. Arméline, 2003, p. 78

- ^ "Voena Bolnica, Skopje - Official website". voenabonica.gov.mk. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) Template:Mk icon - ^ "Institute for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology – Skopje". oncology.org.mk. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Hospital Philip II – Skopje, Republic of Macedonia". cardiosurgery.com.mk. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Website of the Clinical Centre, Skopje". ukcs.org.mk. Retrieved 2010-30-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) Template:Mk icon - ^ a b c Republic of Macedonia – National Bureau of Statistics, birth and mortality in urban municipalities

- ^ PopulationData. "PopulationData.net – Macedoine". populationdata.net. Retrieved 2011-01-01. Template:Fr icon

- ^ CIA. "CIA, The World Factbook - Macedonia". cia.gov. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Strategy for Local Economic Development of the City of Skopje – comparison of national and local figures

- ^ Ss. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. "Ss. Cyril and Methodius University - Skopje, Official website". ukim.edu.mk. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ European University - Republic of Macedonia. "European University - Skopje, Official website". eurm.edu.mk. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ FON University. "FON University - Skopje, Official website". fon.edu.mk. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ American University College, Skopje. "Website of American College in Skopje". uacs.edu.mk. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Yahya Kemal College. "Yahya Kemal College, Republic of Macedonia". yahyakemalcollege.edu.mk. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ City of Skopje. "Official site of the city – Schools and Education". skopje.gov.mk. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Macedonian railways to join Cargo 10". ICT magazine. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- ^ "За две недели нови автобуси низ скопските улици". kurir.mk. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ^ "Избрани консултантите за трамвај во Скопје". A1 TV Online. Retrieved 2011-02-03. Template:Mk icon

- ^ MIA. "Goce Delcev, Dame Gruev monuments erected at Skopje square". mia.com.mk. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Macedonia National Tourism Portal. "Old Bazaar - Skopje". exploringmacedonia.com. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Old Skopje. "The Mustapha Pasha Mosque and the Turbe". oldskopje.net. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Old Skopje. "Mustafa Pasha Mosque". inyourpocket.com. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Soros. "Kursumli an, Skopje". soros.org.mk. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ MIA. "Пет дена подоцна во Скопје ќе биде отворена Спомен-куќата на најпозната скопјанка и нобеловка Мајка Тереза". mia.com.mk. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Barikada - World Of Music - Svastara - 2007. "Barikada - World Of Music". Barikada.com. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Kadmus Arts. "Youth Open Theater YOT (Mlad Otvoren Teatar MOT)". kadmusarts.com. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- ^ European Handball Federation. "2001/02 Women's Champions League finals". euronandball.com. Retrieved 2010-29-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Official portal of City of Skopje – Skopje Sister Cities". © 2006–2009 City of Skopje. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "City of Belgrade – International Cooperation". Beograd.rs. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ "Sister Cities of Istanbul". Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- ^ Erdem, Selim Efe (2003-11-03). "İstanbul'a 49 kardeş" (in Turkish). Radikal. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

49 sister cities in 2003

- ^ daenet d.o.o. "Sarajevo Official Web Site : Sister cities". Sarajevo.ba. Retrieved 2009-05-06.