Choline

This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (January 2014) |  |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2-Hydroxy-N,N,N-trimethylethanamonium

| |

| Other names

Bilineurine, (2-Hydroxyethyl)trimethylammonium

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 1736748 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.487 |

| EC Number |

|

| 324597 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C5H14NO+ | |

| Molar mass | 104.17080 |

| Density | 1.09 g/ml |

| Boiling point | 305 °C (581 °F; 578 K) |

| 500 mg/ml | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

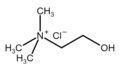

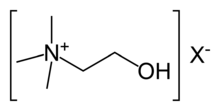

Choline is a water-soluble nutrient.[1][2][3][4][5] It is usually grouped within the B-complex vitamins. Choline generally refers to the various quaternary ammonium salts containing the N,N,N-trimethylethanolammonium cation. (X− on the right denotes an undefined counteranion.)

The cation appears in the head groups of phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin, two classes of phospholipid that are abundant in cell membranes. Choline is the precursor molecule for the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which is involved in many functions including memory and muscle control.

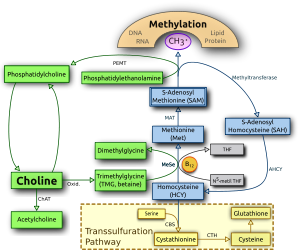

Some animals must consume choline through their diet to remain healthy. To humans, choline is an essential nutrient, as its role in reducing the risk of neural tube defects, fatty liver disease, and other pathologies has been documented.[6] Furthermore, while methionine and folate are known to interact with choline in the methylation of homocysteine to produce methionine, recent studies have shown that choline deficiency may have adverse effects, even when sufficient amounts of methionine and folate are present.[2][6] It is used in the synthesis of components in cell membranes. The 2005 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey stated that only 2% of postmenopausal women consume the recommended intake for choline.[7]

History

Choline was first isolated by Adolph Strecker from pig and ox bile (Greek: χολή, chole) in 1862.[8] When it was first chemically synthesized by Oscar Liebreich in 1865,[8] it was known as neurine until 1898 when it was shown to be chemically identical to choline.[9] In 1998, choline was classified as an essential nutrient by the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine (USA).[10]

Research

A 2010 study tested postmenopausal women with low estrogen levels to see if they were more susceptible to the risk of organ dysfunction if not given a choline-sufficient diet. When deprived of choline in their diets, 73% of postmenopausal women given a placebo developed liver or muscle damage, but this was reduced to 17% if estrogen supplements were given. The study also noted young women should be supplied with more choline because pregnancy is a time when the body's demand for choline is highest. Choline is particularly used to support the fetus's developing nervous system.[7]

Involvement of choline in long-term health and development of clinical disorders, such as cardiovascular diseases, cognitive decline in aging and regulation of blood lipid levels, has not been well-defined, and remains under research in 2015.[11]

Chemistry

Choline is a quaternary ammonium salt with the chemical formula (CH3)3N+(CH2)2OHX−, where X− is a counterion such as chloride (see choline chloride), hydroxide or tartrate. Choline chloride can form a low-melting deep eutectic solvent mixture with urea with unusual properties.[12] The salicylate salt is used topically for pain relief of aphthous ulcers.[13][14]

Choline hydroxide

Choline hydroxide is one of the class of phase transfer catalysts that are used to carry the hydroxide ion into organic systems, and, therefore, is considered a strong base. It is the least-costly phase transfer catalyst, and is used as an effective method of stripping photoresists in circuit boards.[15] Choline hydroxide is not completely stable, and it slowly breaks down into trimethylamine.[16]

Role in humans

Physiology

Choline and its metabolites are needed for three main physiological purposes: structural integrity and signaling roles for cell membranes, cholinergic neurotransmission (acetylcholine synthesis), and a major source for methyl groups via its metabolite, trimethylglycine (betaine), which participates in the S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) synthesis pathways.[17][18]

Choline deficiency signs

Most common signs of choline deficiencies are fatty liver and hemorrhagic kidney necrosis. Consuming a choline-rich diet will relieve the deficiency symptoms. A study of this on animals has created some controversy due to the inconsistency in dietary modifying factors.[19]

Fish odor syndrome

Choline is a precursor to trimethylamine, which some persons are not able to break down due to a genetic disorder called trimethylaminuria. Persons suffering from this disorder may suffer from a strong fishy or otherwise unpleasant body odor, due to the body's release of odorous trimethylamine. A body odor will occur even on a normal diet – i.e., one that is not particularly high in choline. Persons with trimethylaminuria are advised to restrict the intake of foods high in choline; this may help to reduce the sufferer's body odor.[20]

Groups at risk for choline deficiency

Endurance athletes and people who drink a lot of alcohol may be at risk for choline deficiency and may benefit from choline supplements.[21][22] Studies on a number of different populations have found that the average intake of choline was below the adequate intake.[2][23]

The choline researcher Dr. Steven Zeisel wrote: "A recent analysis of data from NHANES 2003–2004 revealed that for [American] older children, men, women and pregnant women, mean choline intakes are far below the AI. Ten percent or fewer had usual choline intakes at or above the AI."[2]

Food sources of choline

The adequate intake (AI) of choline is 425 milligrams per day for adult women, and higher for pregnant and breastfeeding women. The AI for adult men is 550 mg/day. There are also AIs for children and teens.[24]

| Animal and plant foods | Food amount (Imperial) | Food amount (Metric) | Choline (mg) | Calories | % of diet to meet AI (smaller is better)[a 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw beef liver | 5 ounces | 142g | 473 | 192 [nb 1] |

9 |

| Cauliflower | 1 pound | 454g | 177 | 104 [nb 2] | 13 |

| Large egg | 1 | 50g | 147 | 78 [nb 3] |

12 |

| Broccoli | 1 pound | 454g | 182 | 158 [nb 4] | 19 |

| Brewer's yeast | 2 tbsps | 30g | 120 | 116 [25] | 21 |

| Cod fish | 0.5 pound | 227g | 190 | 238 [nb 5] |

28 |

| Spinach | 1 pound | 454g | 113 | 154 [nb 6] |

30 |

| Wheat germ | 1 cup | 240mL | 202 | 432 [nb 7] |

47 |

| Soybeans, mature, raw | 1 cup | 186 | 216 | 86 [nb 8] |

51 |

| Milk, 1% fat | 1 quart | 946mL | 173 | 410 [nb 9] |

52 |

| Firm tofu | 2 cups | 470mL | 142 | 353 [nb 10] |

55 |

| Chicken | 0.5 pound | 227g | 150 | 543 [nb 11] |

80 |

| Cooked kidney beans | 2 cups | 2 cups | 108 | 450 [nb 12] |

92 |

| Uncooked quinoa | 1 cup | 1 cup | 119 | 626 [nb 13] |

116 |

| Uncooked amaranth | 1 cup | 1 cup | 135 | 716 [nb 14] | 117 |

| Grapefruit | 1 | 1 | 19 | 103 [nb 15] |

119 |

| Peanuts | 1 cup | 146g | 77 | 828 [nb 16] |

237 |

| Almonds | 1 cup | 143g | 74 | 822 [nb 17] |

244 |

| Cooked brown rice | 3 cups | 710mL | 54 | 649 [nb 18] |

264 |

Besides cauliflower, other cruciferous vegetables may also be good sources of choline.[26]

The USDA Nutrients Database has choline content for many foods.

Necessary choline for humans

Here are the daily adequate intake (AI) levels and upper limits (UL) for choline in milligrams, taken from a report published in 2000 by the American Institute of Medicine. [2]

| Life Stage Group | AI | UL |

|---|---|---|

| Infants 0–6 months 7–12 months |

(mg/day) 125 150 |

(mg/day) ND ND |

| Children 1–3 yrs 4–8 yrs |

200 250 |

1000 1000 |

| Males 9–13 yrs 14–18 yrs 19–30 yrs 31–50 yrs 50–70 yrs 70 yrs |

375 550 550 550 550 550 |

2000 3000 3500 3500 3500 3500 |

| Females 9–13 yrs 14–18 yrs 19–30 yrs 31–50 yrs 50–70 yrs 70 yrs |

375 400 425 425 425 425 |

2000 3000 3500 3500 3500 3500 |

| Pregnancy ≤ 18 yrs 19–30 yrs 31–50 yrs |

450 450 450 |

3000 3500 3500 |

| Lactation ≤ 18 yrs 19–30 yrs 31–50 yrs |

550 550 550 |

3000 3500 3500 |

AI: Adequate Intake; UL: Tolerable upper intake levels.

Health effects of dietary choline

Choline deficiency may play a role in liver disease, atherosclerosis, and possibly neurological disorders.[2] One sign of choline deficiency is an elevated level of the liver enzyme ALT.[27]

It is particularly important for pregnant women to get enough choline, since low choline intake may raise the rate of neural tube defects in infants, and may affect their children's memory. One study found that higher dietary intake of choline shortly before and after conception was associated with a lower risk of neural tube defects.[28] If low choline intake causes an elevated homocysteine level, it raises the risk for preeclampsia, premature birth, and very low birth weight.[2]

Women with diets richer in choline may have a lower risk for breast cancer,[29][30] but other studies found no association.[31][32]

Some evidence suggests choline is anti-inflammatory. In the ATTICA study, higher dietary intake of choline was associated with lower levels of inflammatory markers.[33] A small study found that choline supplements reduced symptoms of allergic rhinitis.[34]

Despite its importance in the central nervous system as a precursor for acetylcholine and membrane phosphatidylcholine, the role of choline in mental illness has been little studied. In a large population-based study, blood levels of choline were inversely correlated with anxiety symptoms in subjects aged 46–49 and 70–74 years. However, there was no correlation between depression and choline level in this study.[35]

The adequate intake is intended to be high enough to be adequate for almost all healthy people.[36] Many people do not develop deficiency symptoms when consuming less than the adequate intake of choline.[2] The human body synthesizes some of the choline it needs, and people vary in their need for dietary choline.[37] In one study, premenopausal women were less sensitive to a low-choline diet than men or postmenopausal women.[37]

However, the adequate intake may not be enough for some people. In the same study, six of 26 men developed choline deficiency symptoms while consuming the adequate intake (and no more) of choline.[37] The adequate intake was less than the optimal intake for the male subjects in another study.[38]

High dietary intake of choline was associated with an increased risk of colon adenomas (polyps), for women in the Nurses' Health Study. However, this could represent effects of other components in the foods from which choline was obtained.[39] Dietary choline intake was not associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer, for men in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study.[40]

Similar to the effect on memory of choline consumption in utero or as a neonate discussed below, adult rodent dietary choline deficiency has been demonstrated to exacerbate memory loss, and diets high in choline appear to diminish memory loss. Further, choline-supplemented older mice performed as well as young three-month-old mice, and supplemented mice were noted to have more dendritic spines per neuron within the hippocampus. However, no similar work has been done in humans.[41]

Choline as a dietary supplement

The most often available choline supplement is lecithin, derived from soy or egg yolks, often used as a food additive. Phosphatidylcholine is also available as a supplement, in pill or powder form. Supplementary choline is also available as choline chloride, which comes as a liquid due to its hydrophilic properties.

Choline or betaine supplements may reduce homocysteine.[42]

Choline supplements are often taken as a form of 'smart drug' or nootropic, due to the role the neurotransmitter acetylcholine plays in various cognition systems within the brain. Choline is a chemical precursor or "building block" needed to produce acetylcholine, and research suggests that memory, intelligence, and mood are mediated at least in part by acetylcholine metabolism in the brain.[43] In a study on rats, a correlation was shown between choline intake during pregnancy and mental task performance of the offspring;[44] but the same correlation has not been shown in humans.[45] However, this human study admits that "[w]omen in the current study consumed their usual diets. They were not eating choline-enriched diets and were not receiving choline supplementation. Therefore, our results indicate that choline concentrations in a physiologic range observed among women consuming a regular diet during pregnancy are not related to IQ in their offspring. We cannot rule out the possibility that choline supplementation could have an IQ effect."[45]

Initial studies on Rhesus macaques found that choline supplementation had adverse effects on the fetuses of smoking or nicotine-consuming mothers. When consumed with nicotine, choline protected some regions of the fetal brain from damage, but worsened nicotine's effects in other regions. This indicates that choline, ordinarily thought to be neuroprotectant, may worsen some of the adverse effects of nicotine.[46]

The compound's polar groups, the quaternary amine and hydroxyl, render it lipid-insoluble, which might suggest it would be unable to cross the blood–brain barrier. However, a choline transporter that allows transport of choline across the blood–brain barrier exists.[47] The efficacy of these supplements in enhancing cognitive abilities is a topic of continuing debate.

The US Food and Drug Administration requires that infant formula not made from cow's milk be supplemented with choline.[48]

Due to its role in lipid metabolism, choline has also found its way into nutritional supplements that claim to reduce body fat, but little or no evidence proves it has any effect on reducing excess body fat, or that taking high amounts of choline will increase the rate at which fat is metabolised.[citation needed]

Pharmaceutical uses

Choline supplementation can be used in the treatment of liver disorders,[49][50] hepatitis, glaucoma,[51] atherosclerosis, Alzheimer's disease,[52] bipolar disorder [53] and possibly other neurological disorders.[2]

Choline has also been shown to have a positive effect on those suffering from alcoholism.[54][55]

The National Institute of Health funded research study Citicoline Brain Injury Treatment Trial (COBRIT) gathered data regarding the potential benefits of the long-term supplementation of the choline phospholipid (Phosphatidylcholine) intermediate citicoline for recovery after traumatic brain injury but the study was terminated early by futility due to a lack of effectiveness.[56]

Medical imaging

Choline can be labelled with carbon-11 or fluorine-18 which are radioactive positron emitters, enabling medical imaging on a positron emission tomography (PET) scanner. This type of scan is usually performed by a physician specializing in nuclear medicine. Uses include imaging prostate and breast cancer. In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved choline C-11 as an imaging agent to be used during a PET scan to detect prostate cancer.[57]

Pregnancy and brain development

Introduction

The human body can produce choline by methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine by N-methyltranferase (PEMT) to form phosphatidylcholine in the liver, or it may be consumed from the diet. It has been demonstrated that both de novo production and dietary consumption are necessary, as humans eating diets lacking choline develop fatty liver, liver damage, and muscle damage. However, because of the close interplay between choline, folate, methionine, and vitamin B12, (whose pathways overlap), the function of choline can be complex.

To begin with, methionine can be formed two ways, either from methyl groups derived from folate, or from methyl groups derived from betaine (which gets its methyl groups from choline). Changes in one of these pathways is compensated for by the other, and if these pathways do not adequately supply methyl groups to produce methionine, the precursor to methionine, homocysteine, rises.

Choline in food exists in either a free or esterified form (choline bound within another compound, such as phosphatidylcholine, through an ester linkage). Although all forms are most likely usable, some evidence indicates they are unequally bioavailable (able to be used by the body). Lipid-soluble forms (such as phosphytidylcholine) bypass the liver once absorbed, while water-soluble forms (such as free choline) enter the liver portal circulation and are generally absorbed by the liver.[58] Both pregnancy and lactation increase demand for choline dramatically. This demand may be met by upregulation of PEMT via increasing estrogen levels to produce more choline de novo, but even with increased PEMT activity, the demand for choline is still so high that bodily stores are generally depleted. This is exemplified by the observation that Pemt -/- mice (mice lacking functional PEMT) will abort at 9–10 days unless fed supplemental choline.[59]

While maternal stores of choline are depleted during pregnancy and lactation, the placenta accumulates choline by pumping choline against the concentration gradient into the tissue, where it is then stored in various forms, most interestingly as acetylcholine, (an uncommon occurrence outside of neural tissue). The fetus itself is exposed to a very high choline environment as a result, and choline concentrations in amniotic fluid can be ten times higher than in maternal blood. This high concentration is assumed to allow choline to be abundantly available to tissues and cross the blood-brain barrier effectively.[59]

Functions in the fetus

Choline is in high demand during pregnancy as a substrate for building cellular membranes, (rapid fetal and mother tissue expansion), increased need for one-carbon moieties (a substrate for addition of methylation to DNA and other functions), raising choline stores in fetal and placental tissues, and for increased production of lipoproteins (proteins containing "fat" portions).[60][61][62] In particular, there is interest in the impact of choline consumption on the brain. This stems from choline's use as a material for making cellular membranes, (particularly in making phosphatidylcholine). Human brain growth is most rapid during the third trimester of pregnancy and continues to be rapid to approximately five years of age.[63] During this time, the demand is high for sphingomyelin, which is made from phosphytidyl choline (and thus from choline), because this material is used to myelinate (insulate) nerve fibers.[64] Choline is also in demand for the production of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which can influence the structure and organization of brain regions, neurogenesis, myelination, and synapse formation. Acetylcholine is even present in the placenta and may help control cell proliferation/differentiation (increases in cell number and changes of multiuse cells into dedicated cellular functions) and parturition.[65][66][67][68] Choline may also impact methylation of CpG dinucleotides in DNA in the brain – this methylation can change genome expression (which genes are turned on and which are turned off) and thus fetal programming (the act of arranging so that certain genes are by default turned off or turned on in the absence of external forces).[69][70]

What choline does within the fetus is determined by its concentration. At low choline concentrations, it is preferentially shunted towards making phospholids. As concentrations rise, free choline is converted in liver mitochondria to betaine, which is used as a source of methyl groups for DNA methylation, etc.[71][72] However, should concentrations of choline decrease enough, the PEMT pathway is up regulated, (activated).[73] The PEMT pathway allows for creation of new choline without consuming choline from the diet. This pathway has been shown to produce up to 30% of needed phosphotidylcholine.[74] Interestingly, PEMT-produced phosphytidyl choline tends to have longer, less saturated fatty acids than that produced directly from choline via the CDP-choline pathway.[75]

Concentration is also important in getting choline into the brain for use to prevent neural nonclosure and poor brain development.[58] Choline uptake into the brain is controlled by a low-affinity (not particularly efficient) transporter located at the blood-brain barrier. Transport occurs when arterial plasma choline concentrations increase above 14 μmol/l, which can occur during a spike in choline concentration after consuming choline-rich foods. Neurons, conversely, acquire choline by both high- and low-affinity transporters. Choline is stored as membrane-bound phosphytidylcholine, which can then be used for acetylcholine neurotransmitter synthesis later. Acetylcholine is formed as needed, travels across the synapse, and transmits the signal to the following neuron. Afterwards, acetylcholinesterase degrades it, and the free choline is taken up by a high-affinity transporter into the neuron again.[76]

Neural tube closure

While folate is most well known for preventing neural tube nonclosure (the basis for its addition to prenatal vitamins), folate and choline metabolism are interrelated. Both choline and folate (with the help of vitamin B12) can act as methyl donors to homocysteine to form methionine, which can then go on to form SAM (S-Adenosyl methionine) and act as a methyl donor for methylation of DNA. Dietary choline deficiency alone without concurrent folate deficiency can decrease SAM concentration, suggesting that both folate and choline are important sources of methyl groups for SAM production.[59] Inhibition of choline absorption and use is associated with neural-tube defects in mice, and this may also occur in humans.[58] A retrospective case control study (a study that collects data after the fact, from cases occurring without the investigator causing them to occur) of 400 cases and 400 controls indicated that women with the lowest daily choline intake had a four-fold greater risk of having a child with a neural-tube defect than women in the highest quartile of intake.[77]

Choline in utero and long-term memory

Maternal dietary consumption or lack of consumption of choline during late pregnancy in rodents was related to irreversible changes in hippocampal function in adult rodents, including changes in long-term memory capacity. Increased consumption of choline in rodent dams by about four times dietary recommendations during days 11–17 of pregnancy increased hippocampal cell proliferation and decreased apoptosis (programmed cell death) of these cells in their fetuses. This may occur because, in choline-deficient cells in culture, and in fetal rodent brains from choline deficient dams, the promoter of CDKN3, a gene which inhibits cell proliferation in the brain, is not properly methylated. This leaves CDKN3 active, decreasing cell proliferation in the brain. Increased choline consumption by rodent dams has shown improved auditory and visuaspatial memory in offspring, as well as preventing age-related memory decline as their offspring grew old. The capacity of choline consumption by dams to improve the memory of their offspring has been shown in a variety of memory tests, including the radial-arm maze, Morris water maze, passive avoidance paradigms, and measures of attention. It has also been demonstrated in a variety of rat strains – including Sprague-Dawley and Long-Evans, and in mice. This suggests the effect of choline consumption on the fetus in utero is universal among rodents. However, the mechanism behind this response is not fully understood. The effect of neonatal choline on memory has been suggested to come from increasing the amount of choline in the brain, and subsequently, the amount of acetylcholine that can be produced and released. However, the amount of choline that accumulates in the brain after consumption of choline by pregnant dams does not seem to be sufficient to change the acetylcholine release. Instead, choline consumption by dams was noted to increase phosphocholine and betaine in the fetal brain.

These findings are in rodents, a species with faster brain maturation and a more mature brain at birth than is typical for humans. In humans, the brain continues to develop after birth, and does not become similar to its adult structure until around four years of age. By feeding infants formula instead of milk, and presumably through differences in choline amount in the breast milk of mothers consuming different choline levels, the still-developing brain of an infant may be impacted, which may, in part, contribute to the differences seen between individual adult humans in memory and recall.[59]

Impact of genetic polymorphisms (genetic variation)

Some men and women develop organ dysfunction when fed low-choline diets, while others do not, and the range in choline requirements for optimal health is large, from 850 mg/70 kg/day to 550 mg/70 kg/day. This difference has been attributed to single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in choline metabolic pathways, (SNPs change the RNA code, and can subsequently change the arrangement of the protein made from that RNA, leading to differences in protein function between the normal version and the SNP version). For example, folate-pathway polymorphisms may limit the usability of folate for SAM production – thereby making a person more dependent on choline for SAM production. PEMT polymorphisms change the amount of choline that can be synthesized de novo, (increasing the amount of choline that must be supplied by the diet).

In one study, a common genetic polymorphism, 5,10 methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase1958A (MTHFDI), in folate metabolism made premenopausal women 15 times more likely to develop signs of choline deficiency on a low-choline diet as non-carriers of the SNP (p < 0.0001). The impact of this SNP is quite large - 63% of the study population had at least one allele with the SNP. The MTHFD1 allele is believed to change the flux between 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate and 10-formyltetrahydrofolate, which influences the availability of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate for homocysteine methylation (and subsequent methionine and then SAM production). This would mean more choline would be shunted towards methylation to make up for the lack of folate participation in the pathway.[59] A real-world application of this is the risk of having a child with a neural-tube defect is increased in mothers with the G1958A SNP in MTHFD1.[78] Additionally, mice that are Mthfr -/- (lacking MTHFR) become choline deficient, suggesting that humans with genetic polymorphisms that alter the functionality of the enzyme may also have choline deficiency problems.

SNPs have also been found in PEMT (responsible for de novo choline production). Ziesel, et al., located an SNP in the promoter region of the PEMT gene that was related to increased susceptibility to choline deficiency in women. Since sexual differences in the impact of this SNP were found, Ziesel suggested this SNP alters the estrogen responsiveness of the promoter region of the PEMT gene. The group also located another SNP in exon 8 (the coding portion of a gene) of PEMT with 30% loss of function of PEMT and increased risk for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as an end result.[59]

Not all SNPs in choline/folate-related genes have been shown to impact choline needs, though. C677T and A1298C polymorphisms in MTHFR and A80C polymorphism in the reduced folate carrier gene have not been found to be significant.

Choline and lactation

Introduction to lactation

The human mammary gland is composed of several cell types, including adipose (fat cells), muscle, ductal epithelium, and mammary epithelium (referred to sometimes as lactocytes). The mammary epithelium is the site for excretion of raw materials into the milk supply, including choline. This occurs, for the fat portion of the milk, by apocrine secretion, where vacuoles containing materials bud off the cell into the lumen (storage) of the alveolus (milk secretion gland). From here the milk will be released upon stimulation with oxytocin via suckling.[79] The mammary gland may have evolved from the innate immune system, and lactation may be connected to inflammation – based on the observation that inflammation signaling pathways, NF-κB and Jak/Stat are found both in inflammatory responses and lactation. If this is true, it highlights the role of the mammary gland not only as a source of energy, but also as a major contributor to preparing offspring for survival in the outside world.[80]

Choline in milk

Choline can be found in milk as free choline, phosphocholine, glycerophosphocholine, sphingomyelin, and phosphatidylcholine, and choline levels within breast milk are correlated with choline levels in maternal blood.[81][82] Choline consumed via breast milk has been shown to impact blood levels of choline in breast-fed infants – indicating that choline consumed in breast milk is entering the neonatal system.[82] Choline may enter the milk supply either directly from the maternal blood supply, or choline-containing nutrients may be produced within the mammary epithelium.[83] Choline reaches the milk through a transporter specific for choline from the maternal blood supply (against a concentration gradient) into the mammary epithelial cells.[84] At high concentrations (greater than that typically seen in humans), choline can diffuse across the cell membrane into the mammary epithelium cell. At more normal concentrations, it passes via what is believed to be a calcium/sodium-dependent, phosphorylation-related, active transporter into the cell. It may also be produced within the mammary epithelium de novo via the PEMT pathway.[85] Once choline-containing milk has been consumed by the neonate, it is used for formation of acetylcholine, phosphatidylcholine, sphingomyelin, and choline plasmalogens for cell membrane production in mice, and the majority of the choline in human milk is supplied as phosphocholine. James also demonstrated the hormone insulin may stimulate choline uptake into mouse mammary cells, and prolactin encouraged choline incorporation into lipids when cells were concurrently treated with insulin and cortisol.[83]

Differences between full-term and premature mothers and infants

Holmes-McNary et al. reported the choline content in mature breast milk from mothers delivering preterm was significantly lower than the choline content from mothers delivering at term. However, choline esters (choline-containing compounds) did not differ in concentration between preterm and full-term mothers.[86] Mothers delivering before full term may not have adequate mammary development, and may not reach full mammary development by the time they begin producing mature milk.[79] Choline content may be lower in preterm mothers possibly because of this effect. However, Lucas et al. did find significant improvement at 18 months and at 7.5–8 years of age in IQ score among preterm infants who were fed breast milk via tube in comparison to those who were not fed breast milk, suggesting that even if the mammary gland may be "immature", breast milk produced by it still has benefit. Additionally, preterm infants fed formula prepared for term infants had lower mental performance than those fed formula prepared specifically for preterm infants, but this effect was diminished between preterm infants fed donated breast milk and those fed preterm formula. Further supporting this, Lucas et al. also found, of the factors examined, consumption of mothers' milk was the most significantly related to later IQ performance.[87]

Additionally, a meta-analysis by Anderson et al. found the low-birth-weigh infants derived more benefit from breast feeding, (in terms of IQ score later in life) than did normal-weight infants also being breast-fed.[88] Drane and Logemann summarize their meta-analysis of 24 studies by stating, "an advantage in IQ to breast-fed infants of the order of five points for term infants and eight points for low birth weight infants [was observed]. Arguably, increases in IQ of these magnitudes would have relatively subtle impact at an individual level. However, the potential impact at a population level must also be considered."[89]

Differences between breast milk and formula

Human milk is very rich in choline, but formulas derived from other sources, particularly soy, have lower total choline concentrations than human milk (and also lack other important nutrients, such as long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, sialylated oligosaccharides, thyroid-stimulating hormone, neurotensin, nerve growth factor, and the enzymes lysozyme and peroxidase).[90][91][92] Bovine milk and bovine-derived formulas had similar or higher glycerophosphocholine compared to human milk, and soy-derived formulas had lower glycerophosphocholine content. Phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin concentrations were similar between bovine formulas and human milk, but soy-derived infant formulas had more phosphatidylcholine than human or bovine sources. Soy-derived formulas had less sphingomyelin than human milk, which is a concern, since sphingomyelin is used for producing myelin, which insulates neurons. Free choline concentrations in mature human milk were 30–80% lower than those found in bovine milk or formulas. Mature human milk also has lower free choline than colostrum-transitional human milk. Phosphocholine is particularly abundant in human milk. Overall, formulas, milks, and breast milk appear to provide different amounts and forms of choline, and Holmes-McNary et al. suggest, "This may have consequences for the relative balance between use of choline as a methyl donor (via betaine), acetylcholine precursor (via choline), or phospholipid precursor (via phosphocholine and phosphatidylcholine)".[93] This is supported by Ilcol et al.'s observations that serum free choline concentrations were lower in formula-fed infants than in breast-fed infants.[82]

state: "The magnitude of the effect of breast-feeding on IQ is somewhat lower than that of anemia and lead burden. Yet feeding mode is an intervention that affects the whole population, thus, the net effect of improving IQ by 3 points may be similar if not larger than that of gaining 6 points in 5–10% of the children." Additionally, they go on to summarize, "The burden of proof should be placed on those who propose that feeding formula from a bottle can equal feeding milk from the breast."[94] Some science supports this proposal. Lucas et al., after adjusting for social and educational factors on development, still found that preterm children consuming breast milk via tube performed over half a standard deviation higher on IQ tests at 7.5–8 years of age than their cohorts who did not receive breast milk. Previously, they had also found an improvement in cognitive development as early as 18 months in preterm infants consuming breast milk versus those not consuming breast milk.[87]

The argument has been made that the increased IQ and developmental performance exhibited by breastfed infants stems from interaction between the mother and child as well as, or without any additional input from, the actual milk. Drane and Logemann suggest that lactation increases oxytocin and prolactin production, generating feelings of well-being in the mother and encouraging nurturing behavior. This may lead to better mother-child relationships and that may in turn generate improved neural performance.[95] Additionally, social class and maternal education are highly correlated with type of infant feeding, (formula vs. breastfeeding), while also being correlated to observed cognitive performance. Lucas et al., however, refutes the assumption that fluid breast milk itself has no or minimal beneficial function on cognitive performance later in life. They report an increase in IQ between preterm infants, (and later 7.5–8 yr old children), provided with breast milk and those not provided with breast milk via nasogastric tube, without any interaction between mother and offspring and with controlling for social and educational factors.[87]

Current consumption levels by lactating and pregnant women

Shaw et al. found that 25% of pregnant women studied in California had observed intakes of less than half the estimated daily choline intake for women.[96]

Cognitive performance and choline in breast milk

As previously stated, choline is necessary for neural development and is higher in breast milk than in formula, so choline may be playing a role in the higher performance of breastfed infants.[82] However, in the meta-analysis under discussion, the author attributed increased cognitive performance to presence of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs) such as docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid, which are lipid components within the brain. Docosahexaenoic acid is enriched in phospholipids produced through the PEMT pathway, (previously mentioned as the pathway responsible for de novo choline production). This means choline production contributes to the body's docosahexaenoic acid pool, and may have implications for docosahexaenoic acid/choline cotransfer into breastmilk. In this meta-analysis they state that the difference between formula and breastfed infants is derived from a lack of these LCPUFAs in infant formulas available in the United States, and no data connecting choline content of the diet and de novo choline production to docosahexaenoic acid has come to light, (data was not provided for formula sources from other countries).[97] Since choline also plays a role in brain development, and differences in choline are present between breast milk and formula, it seems possible that choline could also be playing a role in observed IQ score improvement in breast-fed offspring.

Additional images

-

Choline (C5H14NO+)

-

Choline hydroxide

See also

Notes

- ^ Percentage of diet calculated using 2500 daily calories for an average adult male and 550mg for Adequate Intake (AI) using the figures from the table. As an example, even though peanuts contain some choline, they are a poor source given their 237% of diet to meet AI requirement, which means that a person who ate nothing but peanuts would have less than half of AI. Nearly identical figures are obtained for an average adult female when using 2000 calories and 425mg as assumptions; therefore, separate columns for male and female are not necessary.

References

- ^ Entry for "Beef, variety meats and by-products, liver, raw"in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Cauliflower, cooked, boiled, drained, with salt" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for one large "Egg, whole, cooked, hard-boiled" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Broccoli, cooked, boiled, drained, with salt" in the Nutritiondata database

- ^ Entry for "Fish, cod, Atlantic, cooked, dry heat" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Spinach, frozen, chopped or leaf, cooked, boiled, drained, without salt" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Cereals ready-to-eat, wheat germ, toasted, plain" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Soybeans, mature seeds, sprouted, raw" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Milk, lowfat, fluid, 1% milkfat, with added vitamin A and vitamin D" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Tofu, firm, prepared with calcium sulfate and magnesium chloride (nigari) (1)" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Chicken, broilers or fryers, meat and skin, cooked, roasted" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Beans, kidney, all types, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, without salt" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Quinoa, uncooked" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Amaranth, uncooked" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Grapefruit, raw, pink and red, all areas" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Peanuts, all types, raw" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for 1 cup whole "Nuts, almonds" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Entry for "Rice, brown, long-grain, cooked" in the USDA Nutrients database

- ^ Jane Higdon, "Choline", Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University

- ^ a b c d e f g h Zeisel SH; da Costa KA (November 2009). "Choline: an essential nutrient for public health". Nutrition Reviews. 67 (11): 615–23. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00246.x. PMC 2782876. PMID 19906248.

- ^ "Choline, PDRHealth[unreliable medical source?]

- ^ "Choline" (An interview with Steven Zeisel, Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry), Radio National Health Report with Norman Swan, Monday 17 April 2000

- ^ "[1]" Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline (1998), Institute of Medicine.

- ^ a b Zeisel, Steven. "Choline: An Essential Nutrient for Public Health". PubMed. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ a b Leslie M Fischer, Kerry-Ann da Costa, Lester Kwock, Joseph Galanko, and Steven H Zeisel (2010). "Dietary choline requirements of women: effects of estrogen and genetic variation". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 92 (5): 1113–1119. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2010.30064. PMC 2954445. PMID 20861172.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Zeisel, Steven H. (2012). "A Brief History of Choline". Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism. 61 (3): 254–258. doi:10.1159/000343120.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Boldyrev, A. A. (14 April 2012). "Carnosine: New concept for the function of an old molecule". Biochemistry (Moscow). 77 (4): 313–326. doi:10.1134/S0006297912040013.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Choline Overview". CholineInfo.org. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ^ "Effects of choline on health across the life course: a systematic review". Nutr Rev. 73 (8): 500–22. 2015. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv010. PMID 26108618.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Andrew P. Abbott, Glen Capper, David L. Davies, Raymond K. Rasheed, Vasuki Tambyrajah (2003). "Novel solvent properties of choline chloride/urea mixtures". Chemical Communications (1): 70–71. doi:10.1039/b210714g.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gastroenterology eu.elsevierhealth.com. Retrieved 15 November 2012. Gastroenterology. Chapter 6. page 128

- ^ Choline salicylate/magnesium salicylate - oral, Trilisate medicinenet.com. Retrieved 15 November 2012

- ^ Sedlak, Rudy (2009). "The Technology of Photoresist Stripping". Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ GuideChem http://www.guidechem.com/products/123-41-1.html

- ^ Glier, Melissa B.; Green, Timothy J.; Devlin, Angela M. (2014). "Methyl nutrients, DNA methylation, and cardiovascular disease". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 58: 172–182. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201200636.

- ^ "Dietary Betaine Promotes Generation of Hepatic S-Adenosylmethionine and Protects the Liver from Ethanol-Induced Fatty Infiltration" (June 1993) Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research Volume 17, Issue 3, Pages: 552–555, Anthony J. Barak, Harriet C. Beckenhauer, Matti Junnila and Dean J. Tuma

- ^ Machlin, Lawrence J. Hand book of Vitamins: Nutritional, Biochemical, and clinical Aspects, Marcel Dekker, New York, 1984. P.556

- ^ Mitchell SC, Smith RL (2001). "Trimethylaminuria: the fish malodor syndrome". Drug Metab Dispos. 29 (4 Pt 2): 517–21. PMID 11259343.

- ^ von Allwörden, H. Niels; et al. (1993). "The influence of lecithin on plasma choline concentrations in triathletes and adolescent runners during exercise". European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology. 67 (1): 87–91. doi:10.1007/BF00377711.

- ^ Klatskin, Gerald, Willard A. Krehl, and Harold O. Conn. (1954). "The effect of alcohol on the choline requirement I. Changes in the rat's liver following prolonged ingestion of alcohol". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 100 (6): 605–614. doi:10.1084/jem.100.6.605.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bidulescu A, Chambless LE, Siega-Riz AM, Zeisel SH, Heiss G (2009). "Repeatability and measurement error in the assessment of choline and betaine dietary intake: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study". Nutrition Journal. 8 (1): 14. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-8-14. PMC 2654540. PMID 19232103.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Dietary Reference Intakes". Institute of Medicine.

- ^ http://www.purcellmountainfarms.com/Brewers%20Yeast.htm

- ^ Gossell-Williams M, Fletcher H, McFarlane-Anderson N, Jacob A, Patel J, Zeisel S (December 2005). "Dietary intake of choline and plasma choline concentrations in pregnant women in Jamaica". The West Indian Medical Journal. 54 (6): 355–9. doi:10.1590/s0043-31442005000600002. PMC 2438604. PMID 16642650.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Micronutrient Information Center: Choline". Linus Pauling Institute.

- ^ Shaw GM, Carmichael SL, Yang W, Selvin S, Schaffer DM (July 2004). "Periconceptional dietary intake of choline and betaine and neural tube defects in offspring". American Journal of Epidemiology. 160 (2): 102–9. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh187. PMID 15234930.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Xu X; Gammon MD; Zeisel SH; et al. (November 2009). "High intakes of choline and betaine reduce breast cancer mortality in a population-based study". The FASEB Journal. 23 (11): 4022–8. doi:10.1096/fj.09-136507. PMC 2775010. PMID 19635752.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Xu X; Gammon MD; Zeisel SH; et al. (June 2008). "Choline metabolism and risk of breast cancer in a population-based study". The FASEB Journal. 22 (6): 2045–52. doi:10.1096/fj.07-101279. PMC 2430758. PMID 18230680.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Cho E, Holmes M, Hankinson SE, Willett WC (December 2007). "Nutrients involved in one-carbon metabolism and risk of breast cancer among premenopausal women". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 16 (12): 2787–90. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0683. PMID 18086790.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cho E, Holmes MD, Hankinson SE, Willett WC (February 2010). "Choline and betaine intake and risk of breast cancer among post-menopausal women". British Journal of Cancer. 102 (3): 489–94. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605510. PMC 2822944. PMID 20051955.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Detopoulou P, Panagiotakos DB, Antonopoulou S, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C (February 2008). "Dietary choline and betaine intakes in relation to concentrations of inflammatory markers in healthy adults: the ATTICA study". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 87 (2): 424–30. PMID 18258634.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Das S, Gupta K, Gupta A, Gaur SN (March 2005). "Comparison of the efficacy of inhaled budesonide and oral choline in patients with allergic rhinitis". Saudi Medical Journal. 26 (3): 421–4. PMID 15806211.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bjelland I, Tell GS, Vollset SE, Konstantinova S, Ueland PM (October 2009). "Choline in anxiety and depression: the Hordaland Health Study". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 90 (4): 1056–60. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27493. PMID 19656836.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Using the Adequate Intake for Nutrient Assessment of Groups". Institute of Medicine.

- ^ a b c Fischer LM; daCosta KA; Kwock L; et al. (May 2007). "Sex and menopausal status influence human dietary requirements for the nutrient choline". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 85 (5): 1275–85. PMC 2435503. PMID 17490963.

- ^ Veenema K; Solis C; Li R; et al. (September 2008). "Adequate Intake levels of choline are sufficient for preventing elevations in serum markers of liver dysfunction in Mexican American men but are not optimal for minimizing plasma total homocysteine increases after a methionine load". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 88 (3): 685–92. PMC 2637180. PMID 18779284.

- ^ Cho E; Willett WC; Colditz GA; et al. (August 2007). "Dietary choline and betaine and the risk of distal colorectal adenoma in women". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 99 (16): 1224–31. doi:10.1093/jnci/djm082. PMC 2441932. PMID 17686825.

- ^ Lee JE, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, Zeisel SH, Cho E (March 2010). "Choline and betaine intake and the risk of colorectal cancer in men". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 19 (3): 884–7. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1295. PMC 2882060. PMID 20160273.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zeisel SH. Choline: critical role during fetal development and dietary requirements in adults. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2006. 26:229–50

- ^ Ueland PM (May 2010). "Choline and betaine in health and disease". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 34 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1007/s10545-010-9088-4. PMID 20446114.

- ^ Coreyann Poly, Joseph M Massaro, Sudha Seshadri, Philip A Wolf, Eunyoung Cho, Elizabeth Krall, Paul F Jacques, and Rhoda Au (2011). "The relation of dietary choline to cognitive performance and white-matter hyperintensity in the Framingham Offspring Cohort". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 94: 1584–1591. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.008938.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sternberg, Robert J. (2000). Handbook of intelligence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-521-59648-0.

- ^ a b Signore C, Ueland PM, Troendle J, Mills JL (April 2008). "Choline concentrations in human maternal and cord blood and intelligence at 5 y of age". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 87 (4): 896–902. PMC 2423009. PMID 18400712.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Theodore A. Slotkin, Frederic J. Seidler, Dan Qiao, Justin E. Aldridge, Charlotte A. Tate, Mandy M. Cousins, Becky J. Proskocil, Harmanjatinder S. Sekhon, Jennifer A. Clark, Stacie L. Lupo & Eliot R. Spindel (January 2005). "Effects of prenatal nicotine exposure on primate brain development and attempted amelioration with supplemental choline or vitamin C: neurotransmitter receptors, cell signaling and cell development biomarkers in fetal brain regions of rhesus monkeys". Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (1): 129–144. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300544. PMID 15316571.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pardridge, WM (2005). "The blood–brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development". NeuroRx : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1602/neurorx.2.1.3. PMC 539316. PMID 15717053.

- ^ "Requirements for Infant Formulas". Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ Tolvanen T; Yli-Kerttula T; Ujula T; et al. (May 2010). "Biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of [(11)C]choline: a comparison between rat and human data". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 37 (5): 874–83. doi:10.1007/s00259-009-1346-z. PMID 20069295.

- ^ Behari J; Yeh TH; Krauland L; et al. (February 2010). "Liver-specific beta-catenin knockout mice exhibit defective bile acid and cholesterol homeostasis and increased susceptibility to diet-induced steatohepatitis". The American Journal of Pathology. 176 (2): 744–53. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2010.090667. PMC 2808081. PMID 20019186.

- ^ Chan KC, So KF, Wu EX (January 2009). "Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy revealed choline reduction in the visual cortex in an experimental model of chronic glaucoma". Experimental Eye Research. 88 (1): 65–70. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2008.10.002. PMID 18992243.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Van Beek AH, Claassen JA (January 2010). "The cerebrovascular role of the cholinergic neural system in Alzheimer's disease". Behavioural Brain Research. 221 (2): 537–542. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.047. PMID 20060023.

- ^ Stoll AL; Sachs GS; Cohen BM; Lafer B; Christensen JD; Renshaw PF (1 September 1996). "Choline in the treatment of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: clinical and neurochemical findings in lithium-treated patients". Biological Psychiatry. 40 (5): 382–388. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(95)00423-8. PMID 8874839.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Klatskin G, Krehl WA (December 1954). "The effect of alcohol on the choline requirement. II. Incidence of renal necrosis in weanling rats following short term ingestion of alcohol". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 100 (6): 615–27. doi:10.1084/jem.100.6.615. PMC 2136403. PMID 13211918.

- ^ Nery FG; Stanley JA; Chen HH; et al. (April 2010). "Bipolar disorder comorbid with alcoholism: a 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy study". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 44 (5): 278–85. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.09.006. PMC 2836426. PMID 19818454.

- ^ "Study of Citicoline for the Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury (COBRIT)". http://clinicaltrials.gov. US Government. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "Mayo Clinic Gets FDA Approval for New Imaging Agent for Recurrent Prostate Cancer". Mayo Clinic. 8 November 2012.

- ^ a b c Zeisel, SH (2006). "The fetal origins of memory: the role of dietary choline in optimal brain development". J Pediatr. 149: S131–S136. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.06.065.

- ^ a b c d e f Zeisel, SH (2006). "Choline: critical role during fetal development and dietary requirements in adults". Annu. Rev. Nutr. 26: 229–50. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.26.061505.111156. PMC 2441939. PMID 16848706.

- ^ Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary reference intakes for Thiamine, Riboflavin, Niacin, Bitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin and Choline. Washington, DC: National Academies Press;1998

- ^ Allen LH. Pregnancy and lactation In: Bowman BA, Russle RM , eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. Washington DC: ILSI Press; 2006: 529–543

- ^ King JC. Physiology of pregnancy and nutrient metabolism. AM J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(suppl):1218S-1225S.

- ^ Morgane, PJ; Mokler, DJ; Galler, JR (2002). "Effects of prenatal protein malnutrition on the hippocampal formation". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 26: 471–483. doi:10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00012-x.

- ^ Oshida K, Shimizu T, Takase M, Tamura Y, Shimizu T, Yamashiro Y. Effects of dietary sphingomyelin on central nervous system myelination in developing rats. Peditr Res. 2003; 53:589–593

- ^ Sastry BV. Human placental cholinergic system. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53:1577–1586

- ^ Sastry, BV; Sadavongvivad, C (1978). "Cholinergic systems in non-nervous tissues". Pharmacol Rev. 30: 650–132.

- ^ Eaton, BM; Sooranna, SR (1998). "Regulations of the choline transport system in superfused microcarrier cultures of BeWo cells". Placenta. 19: 663–669. doi:10.1016/s0143-4004(98)90028-5.

- ^ Wessler I, Kirkpatrick CJ. Acetylcholine beyond neurons: The nonneuronal cholinergic system in humans. BR J Pharmacol. 2009;154:1558–1571.

- ^ Waterland, RA; Jirtle, RL (2004). "Early nutrition, epigenetic changes at transposons and imprinted genes, and enhance susceptibility to adult chronic diseases". Nutrition. 20: 63–68. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2003.09.011.

- ^ Davison, JM; Mellott, TJ; Kovacheva, VP; Blusztajn, JK (2009). "Gestational histone methyltransferases G9a (Kmt1C) and Suv39h1 (Kmt1a) and DNA methylation of their genes in rat fetal liver and brain". J Biol Chem. 284: 1982–1989. doi:10.1074/jbc.m807651200.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Park EI, Garrow TA. "Interaction between dietary methionine and methyl donor intake on rat liver betain-homocysteine methyltranferase gene expression and organization of the human gene. J biol Chem. 199;274:7816–7824.

- ^ Weinhold, PA; Skinner, RS; Sanders, RD (1973). "Activity and some properties of choline ckinase, cholinephosphate cytidyltransferase and choline phosphotranferase during liver development in the rat". Biochem Biophys Acta. 326: 43–51. doi:10.1016/0005-2760(73)90026-x.

- ^ Walkey, CJ; Yu, L; Agellon, LB; Vance, DE (1998). "Biochemical and evolutionary significance of phospholipid methylation". J Biol Chem. 273: 27043–27046. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.42.27043. PMID 9765216.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Reo, NV; Adinehzadeh, M; Foy, BD (2002). "Kinetic analyses of liver phosphatidylcholien and phosphatidylethanolamine biosynthesis using (13)C NMR spectroscopy". Biochem Biophys Acta. 1580: 171–188. doi:10.1016/s1388-1981(01)00202-5.

- ^ Delong, CJ; Shen, YJ; Thomas, MJ; Cui, Z (1999). "Molecular distinction of phosphatidylcholine synthesis between the CDP-choline pathway and phosphatidylehtanolamine methylation pathway". J Biol Chem. 274: 29683–29688. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.42.29683. PMID 10514439.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Caudill, M (2010). "Pre and Postnatal Health: evidence of increased choline needs". American Dietetic Association. 110: 1198–1206. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2010.05.009.

- ^ Shaw, GM; Carmicheal, SL; Yang, W; Selvin, S; Schaffer, DM (2004). "Periconceptional dietary intake of choline and betaine on neural tube defects in offspring". Am J Epidemiol. 160: 102–9. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh187. PMID 15234930.

- ^ Brody; et al. "A polymorphism, R653Q, in the trifunctional enzyme methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase/formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase is a maternal genetic risk factor for neural tube defects: report of the Birth Defects Research Group". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71: 1207–15. doi:10.1086/344213. PMC 385099. PMID 12384833.

- ^ a b Hale T & Hartmann P. Textbook of Human Lactation. Hale Publishing, 2007; p. 35-44

- ^ Vorbach; et al. (June 2006). "Evolution of the mammary gland from the innate immune system?". BioEssays. 28 (606–616): 2006. doi:10.1002/bies.20423. PMID 16700061.

- ^ Holmes-McNarry, MQ; Cheng, WL; Mar, MH; Fussell, S; Zeisel, SH (1996). "Choline and choline esters in human and rat milk in infant formulas". Am J Clin Nutr. 64: 572–6.

- ^ a b c d Ilcol, Y.O.; et al. (2005). "Choline status in newborns, infants, children, breast-feeding women, breast-fed infants, and human breast milk". Journal of Nutritional Biochemsitry. 16: 489–499. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.01.011.

- ^ a b James AR. Hormone Regulation of Choline Uptake and Incorporation in Mouse mammary Gland Explants. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2004 Apr;229(4):323–6.

- ^ Chao, CK; Pomfret, EA; Zeisel, SH (1988). "Uptake of choline by rat mammary gland epithelial cells". Biochem J. 254: 33–8. doi:10.1042/bj2540033.

- ^ Chiao-Kang et al. Uptake of choline by rat mammary-gland epithelial cells. Biochem J. (1988) 254, 33–38.

- ^ Holmes-McNary; et al. (1996). "Choline and choline esters in human and rat milk and in infant formulas". AM J Clin Nutr. 64: 572–6.

- ^ a b c Lucas; et al. (1992). "Breast milk and subsequent intelligence quotient in children born preterm". Lancet. 339: 261–4. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(92)91329-7.

- ^ Anderson; et al. (1999). Am J Clin Nutr. 70: 525–35.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Drane, DL; Logemanna, JA (2000). "A critical evaluation of the evidence on the association between type of infant feeding and cognitive development". Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 14: 349–356. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3016.2000.00301.x.

- ^ Zeisel SH. "Choline: critical Role during Fetal Development and Dietary Requirements in Adults. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2006.26:229–50

- ^ Banapurmath, CR; et al. (1996). "Developing brain and breastfeeding". Indian Pediatrics. 33: 235–38.

- ^ Tram, TH; et al. (1997). "Sialic acid content of infant saliva: comparison of breast fed with formula fed infants". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 77: 315–318. doi:10.1136/adc.77.4.315.

- ^ Holmes-McNary, M; Cheng, WL; Mar, MH; Fussel, S; Zeisel, SH. "Choline and choline esters in human and rat milk and infant formulas". Am J Clin Nutr. 1996 (64): 572–6.

- ^ Uauy; Peirano (1999). "Breast is best:human milk is the optimal food for brain development". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 70: 433–4.

- ^ Drane, DL; Logemann, JA (2000). "A critical evaluation of the evidence on the association between type of infant feeding and cognitive development". Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 14: 349–356. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3016.2000.00301.x.

- ^ Shaw, GM; Carmicheal, SL; Yang, W; Selvin, S; Schaffer, DM (2004). "Periconceptional dietary intake of choline and betain and neural tube defects in offspring". Am J Epidemiol. 160: 102–9. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh187. PMID 15234930.

- ^ Anderson, JW; Johnstone, BM; Remley, DT (1999). "Breast-feeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis". Am J Nutr. 70: 525–35.

External links

- Choline bound to proteins in the PDB

- Choline, Linus Pauling Institute

- Choline, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes